2. Filling in the gaps: expanding social protection in Colombia

The pandemic has highlighted significant gaps in social protection, in particularly among informal workers. With around 60% of workers in informal jobs, many of those most in need of social protection are left behind. The government has attempted to fill this gap with non-contributory benefits, but coverage and benefit levels are low. By contrast, formal workers have access to a full range of social protection benefits, involving large-scale public subsidies to the better-off. Labour informality and social protection coverage are interlinked, as high social contributions are one of the main barriers to formal job creation. Ensuring some basic social protection coverage for all, while simultaneously reducing the cost of formal employment, would reduce labour informality, raise productivity, and decrease poverty and inequality, all of which are long-standing challenges in Colombia.

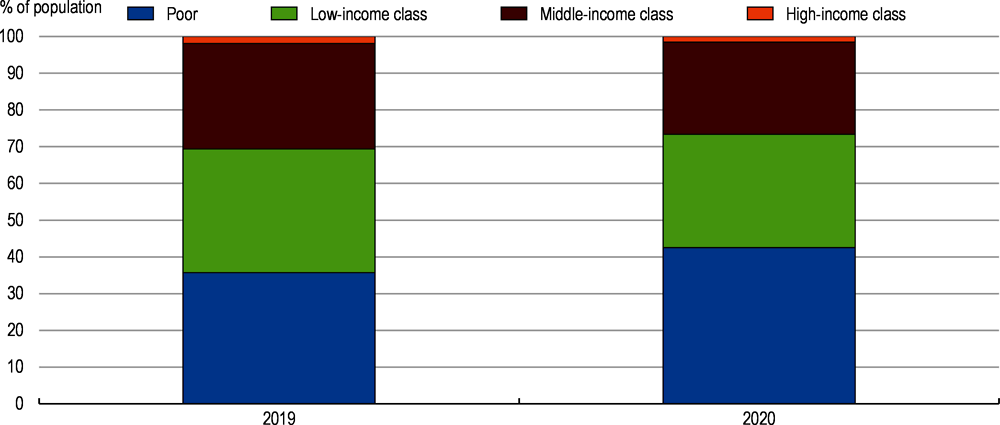

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted long-standing gaps in the social protection system and is reversing decades of progress made in eradicating poverty and reducing inequality. Major structural problems, including a high share of informal workers with no social insurance and a low coverage of social assistance programmes, have worsened and become more visible with the pandemic when incomes of those at the bottom of the income distribution fell three times more than for those with higher incomes. Colombia put in place comprehensive social emergency measures that have been crucial to averting a steeper fall in incomes, particularly among the most vulnerable. These included both an expansion of existing benefits and the establishment of new ones, including an unconditional cash transfer programme and wage subsidies. These social emergency measures prevented 4 million Colombians from falling into poverty in 2020, mitigating the increase in the poverty rate by 3.6 percentage points. Still, unfortunatedly some 3.5 million Colombians fell into poverty, adding up to about 21 million (42.5% of the population).

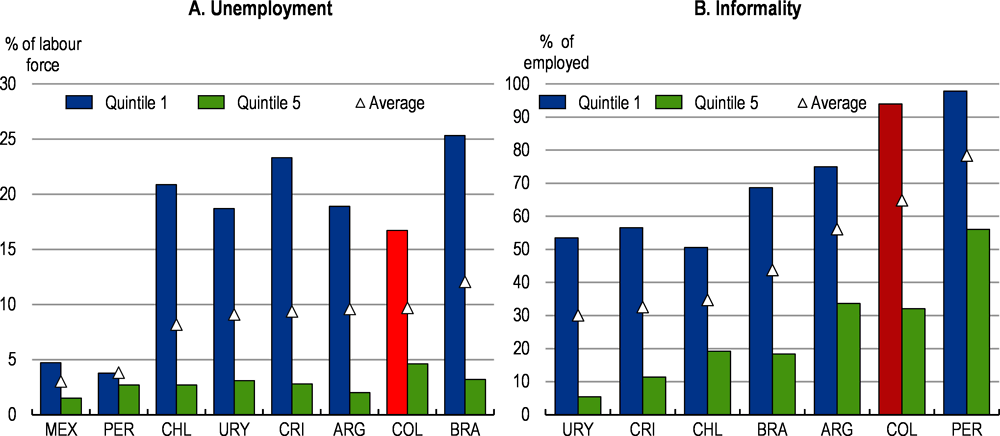

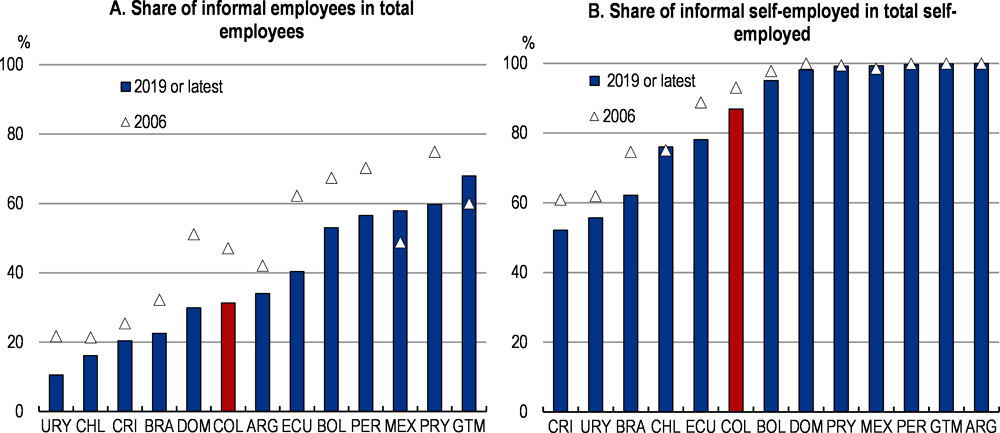

Structural characteristics of Colombia’s labour market are, at least in part, responsible for the large impact of the pandemic on social outcomes. Nearly two out of three workers in Colombia are informal, with no access to contributory social insurance, such as unemployment insurance, old-age pensions or paid sick and maternity leave. Informal workers typically have low and more unstable incomes and lack savings, making them particularly vulnerable in crises. On the other hand, formal workers benefit from employment protection, regulated minimum wages and contributory social protection schemes. Informality also tends to keep companies inefficiently small and their productivity low (Loyaza, 2018[1]). With less access to digital solutions, informal firms have struggled to access the policy support put in place during the pandemic, such as wage subsidies and state-guaranteed loans. Widespread informality also reduces the bases for corporate and personal income taxes, which in turn limits the quantity and quality of public services and the capacity of the public sector.

Among the many roots of informality, including low access to high-quality education and training and a weak institutional framework and enforcement, the design of the social protection system is a key factor. One of the main impediments to formal job creation are the expensive mandatory social contributions and other payroll taxes that finance formal-sector benefits (IMF, 2021[2]; Meléndez et al., 2021[3]; Levy and Cruces, 2021[4]; Loyaza, 2018[1]). The sum of employers’ obligations can reach 53% of the wage for earners on the minimum wage. Because regulations are imperfectly enforced, firms regularly evade the costs of social insurance and hire salaried workers informally. Low-income or self-employed workers with earnings below the minimum wage face prohibitively high costs of formalisation and are forced to remain informal, which is reflected in the low social insurance coverage. These high non-wage costs, bundled with a relatively high minimum wage whose level is close to the median wage, leaves many workers in informal jobs.

To address the lack of coverage in social protection of informal workers, non-contributory pillars in pensions and health have been established over the years. These pillars are financed through the budget with general tax revenues, i.e. non-earmarked resources proceding from different taxes, sometimes, through formal workers’ social contributions. They have been complemented by other social assistance programmes such as conditional cash transfers, which have helped to reduce poverty. But these non-contributory pension and cash transfers programmes share two common features: a low coverage, meaning that many of those in need are left behind, and low benefit levels, which in the case of non-contributory pensions amount to only around half of the extreme poverty line, designed to reflect the cost of the necessary calorie intake for survival. In general, cash transfers and non-contributory pension schemes are only targeted to the very lowest end of the income distribution, leaving many informal and vulnerable workers unprotected. The non-contributory health system has achieved almost full coverage, but its financing encourages informality as informal workers receive the same benefits as their formal peers but free of charge. As a result, the non-contributory regime has reduced the stark gap between the formal and informal workers only to a limited extent. This became painfully obvious in 2020, when incomes at the bottom of the distribution dropped much more than those at the top.

Eradicating absolute poverty is within reach for a middle-income country like Colombia, and would lead to enormous improvements in well-being. While growth has proven the most effective driver behind falling poverty in recent decades, social protection has also played an important role, despite all the shortcomings of the current institutional setup. Building on this progress will be essential for a more inclusive and fairer recovery from the deep scars of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Effective social protection is key to protect workers against idiosyncratic shocks and old-age poverty, but also to adapt to disruptions and changes. The pandemic has been the most visible example, but the digital transformation, climate change, population ageing, migration, and natural disasters are also likely to trigger adjustment processes that will require stronger social protection. This calls for strengthening and adapting the social protection system to allow it to fulfil its key role of reducing poverty and inequality. Effective social protection lays the grounds for enabling workers and their families to access better-quality jobs. At the same time, it will allow low-income earners to invest more into their health, their human capital and that of their children, and will trigger substantial benefits for productivity and long-term growth (UNDP, 2021[5]).

The long-term goal of achieving universal formalisation and universal social protection coverage will require deep reforms to social security and social assistance schemes, coupled with adjustments to labour market policies. Reforms to lower social contributions and payroll taxes can be a powerful tool to reduce informality, as illustrated by Colombia’s 2012 reform. These reforms need to go hand-in-hand with a cautious approach to future minimum-wage adjustments, as both levers affect the cost differential between formal and informal employment.

Lowering social contributions requires developing insurance mechanisms that are not tied to formal employment and not financed by charges on formal employment. A basic level of social protection, including in pensions and unemployment insurance, should be made available to all, while a more comprehensive set of benefits can support those who can contribute more. Delinking access to social protection from worker status in the labour market is the key challenge to break the current duality in incomes and job quality and requires shifting the financing of social protection from social security contributions levied on formal labour proceeds to general budget resources, most of which come from income and consumption taxes. While these general budget resources include personal income taxes, these are economically different from social security contributions in this context, even if both are largely born by households. Personal income taxes cover all income sources, not only formal-sector labour income, and they allow progressive rate schedules including zero rates on low incomes. Unifying social assistance programmes into a single cash benefit scheme while increasing coverage and benefits and providing incentives to take up formal employment will be key to tackle poverty and raise productive inclusion. Continuous efforts to enhance labour and tax enforcement should complement improvements in formalisation incentives.

The main benefit of deep reforms would be to initiate a virtuous cycle between substantial reductions in poverty and inequality and better growth prospects. Workers in the bottom 50% of the income distribution would clearly benefit from the better formal job opportunities and take-home pay that such reforms could deliver. For current formal workers, with the exception of high incomes, the effective tax burden would not change much, as the reduced payroll taxes and social contributions would be substituted by increases in personal income taxes and possibly value-added taxes. For formal workers with relatively higher incomes, a more progressive income tax schedule would imply a higher tax burden than at present.

Financing the reforms will require raising permanent additional resources by about 1% of GDP. This estimate is an upper bound, as the increased formalisation and growth, and consequent revenue collection derived from these reforms are not taken into account. Colombia has space to do this, as tax revenues are low by international standards (see Chapter 1) and expenditure can be reallocated by discontinuing ill-targeted subsidies and less efficient social policy programmes.

In many respects, the costs will be more of a political than an economic nature. The difficulties of finding the necessary political consensus for the deep reforms discussed in this chapter should not be underestimated. The political economy of the broad overhaul of existing institutions that Colombia needs, together with the required fiscal reforms to secure additional revenues, is likely to be winded and tricky. However, the dramatic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social inclusion and potential growth could generate the momentum and trigger a long-overdue political debate, which the incoming administration that takes power in 2022 could foster and lead.

Finding the appropriate sequencing and prioritisation is essential for a politically viable reform agenda. Moving forward in a gradual manner could help to improve political acceptance. In this regard, a first priority should be to strengthen social assistance programmes and consolidate them into a single programme to tackle poverty. This should be financed by additional tax revenues, with changes to the basic deduction and exemptions in personal income taxes being first in line, in addition to reducing exemptions and special rates in VAT. Continuing to reduce non-wage labour costs could then be addressed in a second step, by gradually shifting more of the financing burden from social security contributions towards tax revenues. This would reduce informality and hence be beneficial for productivity, equity and public finances at the same time. A pension reform, including a universal basic pension benefit, should then follow to tackle outstanding inequalities. A gradual approach to these reforms can be instrumental, but they should be undertaken in a coordinated manner. In the past, small patches to punctual problems have often failed to take into account the broader picture, and often created new challenges.

This chapter analyses the challenges and shortcomings of the current social protection system and reviews policy options to expand coverage while boosting formal employment, which is one of the most salient policy priorities for Colombia. The benefits of reforming social protection should be potentiated by simultaneous policy action in other policy areas, including reforms to boost the structurally low and stagnant firm’ productivity and the low access to high quality education and training, as discussed in Chapter 1 and in previous Economic Surveys (OECD, 2019[6]; OECD, 2017[7]).

Poverty and inequality declined significantly in the last two decades in Colombia, but remain the highest among OECD countries (Figure 2.1). Between 2001 and 2015, poverty declined rapidly by about 22 percentage points (1.6 per year, on average), according to the national definition. The middle class also grew substantially during the same period, by around 20 percentage points to 40% of the population (De la Cruz, Manzano and Loterszpil, 2020[8]). The decline in poverty decelerated and poverty eventually started increasing again as of 2017, partly explained by lower economic growth after the strong oil shock in 2014. Economic growth was the main driver of the reduction in poverty and inequality (Joumard and Londoño Vélez, 2013[9]), and the increase of the middle class during the last decade. Beyond growth, however, new social assistance programmes and higher redistribution played an important role (Messina and Silva, 2019[10]). In-kind transfers, particularly education and healthcare services, have also contributed substantially to the reduction of inequality and poverty in the last two decades (Nuñez et al., 2020[11]; Lustig, 2016[12]). However, the redistributive impact of taxes and transfers remains relatively low compared to advanced and even other developing countries (Lustig, 2016[12]).

The Covid-19 pandemic had a profound impact on lives and livelihoods, increasing poverty from 36% to 42.5% in 2020 (Figure 2.1, Panel C). Many of these newly poor households suffered steep income declines and 1.7 million people fell out of the middle-class (Figure 2.2). At the end of 2020, more than 70% of the population were living in poverty or at risk of falling into poverty. Inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, increased by 1.8 percentage points during 2020, despite a strong policy response that included a substantial expansion of existing cash transfer programmes and the creation of new ones.

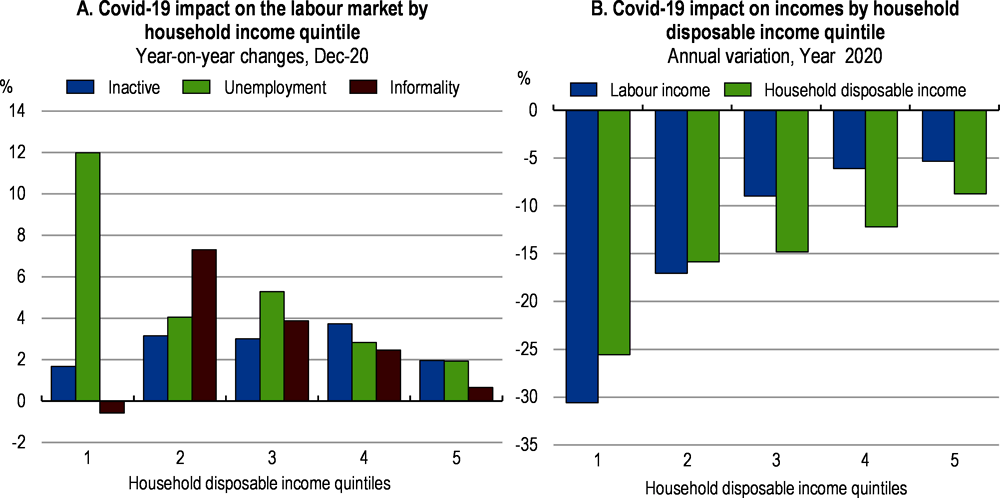

Massive losses of jobs and livelihoods have been the main drivers of the increase in poverty and inequality following the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2.3). This strong impact has its roots in already existing inequalities driven by a high share of informal jobs (Box 2.1), the resulting low social protection coverage and high unemployment, both concentrated in the lowest part of the income distribution (Figure 2.4). This has been coupled with a traditionally patchy coverage of cash transfers benefits that miss out many households in need, despite a significant benefit expansion of existing programmes and development of new programmes in response to COVID-19. Aware of the many challenges, the authorities commissioned in mid-2020 detailed diagnosis and analysis in the context of an “Employment Mission”, which provides useful diagnosis and recommendations to follow up on (Levy and Maldonado, 2021[13]). In addition, a temporary reduction in non-wage labour costs targeted on youths and women is meant to support these groups, which were particularly affected by the pandemic.

There is no unique definition for informal employment. However, a generally accepted way to define it is jobs that are not taxed, registered by the government or do not comply with labour regulations. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines informality for salaried workers as those whose employers do not contribute to social protection systems. The ILO uses a different definition for the self-employed depending on the informal nature of the business or the size of the firm (less than 5 workers). This makes both categories not comparable. This chapter defines informal employment as every type of worker not contributing to social security, i.e. the pension system. The payment of the pension contributions is highly related to all the remaining social contributions (such as health) or the non-compliance of other employment regulations.

Informal employment is highly segmented by socioeconomic characteristics (Figure 2.5, panel A). Most migrant and rural workers regularly hold informal jobs, as do young workers, self-employed and part-time workers. Low skills and informality are strongly connected, with decreasing informality as workers attain higher education levels. The agricultural sector, retail, hotels and restaurants and the construction sectors concentrate many informal workers. Poverty rates are higher among workers in informal employment and there is a strong correlation between household income and informality (Figure 2.5, panel B). Furthermore, informal workers tend to have lower (Figure 2.6) and more unstable incomes, limiting their ability to cope with income shocks. Many workers in Colombia transit between formality and informality many times during their professional careers (Meléndez et al., 2021[3]). This implies that some workers, even when they contribute for some time, usually do not fulfil the requirements to access unemployment insurance or contributory pensions.

Colombia has also high levels of business informality. Around 76% of microenterprises were not registered with the tax administration and 89% were not registered in the chamber of commerce in 2020, according to the microenterprises survey of the national statistical institute. This is highly correlated with low compliance for hiring formal workers, sanitary standards, low implementation of formal accounting and tax declaration and payment (DNP, 2019[14]). Indeed, 88% of microenterprises did not contribute to health or to pension and 95% did not contribute for professional risks. Most informal jobs are concentrated in small firms with a high incidence of low skill and low-productivity occupations (Eslava, Haltiwanger and Pinzón, 2019[15]).

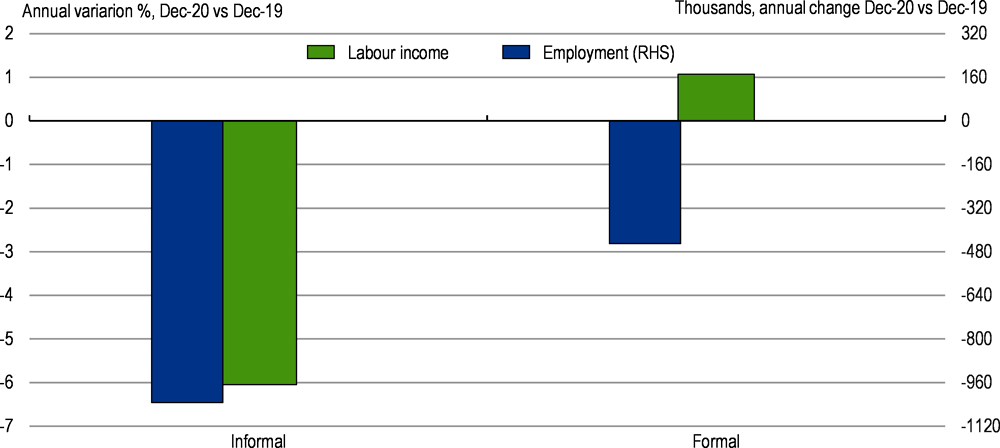

Informal workers suffered the most from the economic fallout of the pandemic, as job losses among informal workers were almost twice as high as among formal workers (Figure 2.7). This marks a break with past recessions when informality used to cushion the decline in employment and acted as a countercyclical buffer. During the pandemic, the lockdowns and mobility restrictions forced many informal workers to stay at home and leave the labour force. While informal workers saw a decline in their average labour income of 6% in 2020, driven mainly by lower hours worked, average labour income increased slightly for formal workers (Figure 2.7). The latter is explained by composition effects as the adjustment in formal employment was mainly done at the expense of temporary workers (ILO, 2021[16]). Precisely because informal jobs are outside the scope of the government, stimulus policies in the form of credits, wage subsidies or furlough schemes generally missed informal workers. One exception is a programme (Unidos por Colombia) in which informal entrepreneurs could access state-guaranteed loans. Moreover, as informal workers have usually no access to savings or any type of social protection, they depended on government cash transfers that compensated only partially for their lost income (Busso et al., 2020[17]). As the economy rebounds, the recovery in employment has been led by informal jobs, threatening to have a permanent raise in informality, which would widen gaps in incomes and job quality (Maurizio, 2021[18]).

Large firms, with a high incidence of formal jobs, were able to cope without downsizing thanks to their greater assets and financial space. Many of them have been able to benefit from increased liquidity, state-guaranteed loans and wage subsidies, some of which were conditional on maintaining their payroll. In contrast, the more numerous micro and small, low-productivity, firms with high incidence of informal jobs were not able to access this liquidity support. They were also less ready for digital solutions, such as selling online or teleworking (OECD, 2019[19]).

Women were also more affected by COVID-19, partly because of pre-existing large employment and wage gaps, which were amplified in 2020 (Figure 2.8, Panel A). Female labour force participation has seen an unprecenteded reduction during 2020, and as the economy rebounds, the recovery has been slower than for men. This is, at least partly, explained by school closures, which lasted for around 30 weeks in 2020, one of the longest closures in the world. Households with a female head were disproportionally affected by increases in poverty in 2020 (Figure 2.8, Panel B). The impact of the crisis also varied greatly across cities and regions, reflecting significant discrepancies in informality, availability and quality of public services.

The migrant population has also been strongly hit by the COVID-19 pandemic as they face various vulnerabilities. Only 25% of Venezuelan migrants have a standard employment contract, and around 90% of Venezuelan workers have informal employment and lack social security coverage (Farné and Sanín, 2020[20]). Migrants were covered by the policy response to the pandemic, in particular in the cash transfers programmes. However, additional requirements, such as a minimum period of residence or being registered in the social registry of beneficiaries, led to the de-facto exclusion of many Venezuelan families.

Aware of these challenges, the Colombian authorities improved immigrants’ access to social protection in 2021 by developing an unprecedented regularisation of immigration status for Venezuelan migrants. In March 2021, Colombia announced a 10-year Temporary Protection Permit for Venezuelan migrants resident in Colombia, granting them temporary legal status. More than 2 million Venezuelans are expected to benefit from the measure, making it one of the largest regularisations ever undertaken in the OECD (OECD, 2021[21]). Access to this mechanism guarantees regular residence states including eligibility for formal employment, education, and healthcare. However, an effective integration of migrants will require a comprehensive strategy with actions spanning several policy areas, such as education, business regulations, pensions, and labour market policies to eliminate remaining integration barriers and improve access to social protection.

Ethnical minorities have also been strongly affected by the pandemic. Poverty rates were higher among those groups before the pandemic and access to social protection very low (ANDI, 2019[22]). The Government increased cash transfer support for ethnical minorities during the pandemic. However, lack of timely statistics prevents a more detail analysis of their labour market integration and access to social protection of these groups, leading to challenges for the design and implementation of public policies.

The social protection system in Colombia is fragmented with entitlements mostly determined by the labour market status (Box 2.2). On the one hand, “social security” benefits are associated with formal work, and, on the other hand, “social assistance policies” directed towards the poor constitute a parallel non-contributory system.

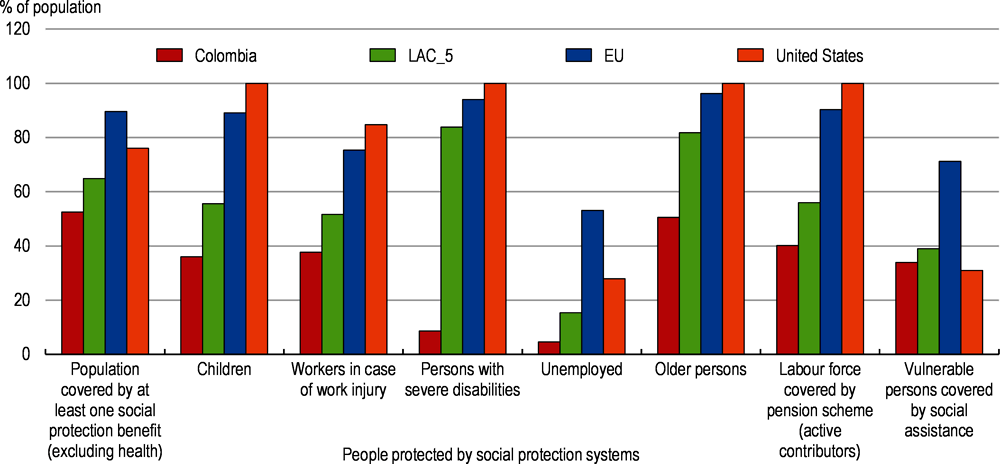

The result of this set-up is a segmentation of the labour force into two categories: formal workers on one hand, covered by contributory programmes and minimum wage regulations, and informal workers on the other, some of which have access to non-contributory social assistance programmes. Informal workers have lower average incomes than formal workers, however, some informal workers have incomes above the poverty line, which generally precludes them from access to non-contributory benefits. Other informal workers may simply not be covered by the social security system because the law excludes them from contributing if they earn less than a monthly minimum wage. Self-employed workers can contribute even if they earn less than the minimum wage, but their social contributions need to be based on a monthly minimum wage. This duality has led to a low coverage of social protection (Figure 2.9).

This fragmentation is not only a source of inequality, but also one important factor contributing to low productivity growth (Levy and Schady, 2013[23]; Levy and Maldonado, 2021[13]). When contributory benefits from the social security system are not fully valued by workers, they tend to act as an implicit tax for formal employment. At the same time, non-contributory benefits can act as a subsidy to informality when they are perceived as similar as those enjoyed by formal workers, who pay for them. In addition, firms tend to stay inefficiently small as they attempt to fly below the radar of labour market inspections.

The social security system comprises health, pension, and unemployment insurance and occupational risk coverage (Figure 2.10). The system is financed through contributions made by employers and/or employees which are proportional to the worker’ salaries or wages, hence the label of “contributory social security scheme”. Workers covered by this system are also subject to regulations on employment protection and minimum wages.

The social assistance system was created to provide insurance to those left out from the contributory social security system and is generally financed through general taxation, hence the label of “non-contributory scheme”. It covers mainly the non-contributory (subsided) health scheme; a small non-contributory pension scheme, which is a cash transfer programme to assist the elderly poor (Colombia Mayor); conditional cash transfer programmes (such as Familias en Acción); and an integrated strategy to help people in poverty (“Estategia Unidos”). The national training institution (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje, SENA) offers vocational and professional training, and the Colombian Family Welfare Institute (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, ICBF) assist vulnerable and poor households. Other important programmes, such as Familias en su tierra (“Families on their own land”), assist the victims of forced displacement who have returned or relocated to their land to help improve their living conditions through access to food, promotion of productive initiatives and improvement of their living conditions. Other programmes targeted at the poor aim at strengthening entrepreneurship and promoting productive activities to sustain self-generating income activities.

Coverage gaps are associated with low spending in social protection. Although social spending has increased substantially in the last two decades from 5.7% of GDP in 1990 (Melo-Becerra and Ramos-Forero, 2017[24]) to 10% of GDP in 2019, it remains low in international perspective (Figure 2.11). Spending in social protection is around 8% of GDP, but 60% of this spending is allocated to pensions, while less than 3% is allocated to social assistance programmes supporting the poor.

Moreover, targeting is poor, with a significant part of social public spending benefiting non-poor households (Table 2.1). This is especially true in the case of pensions, housing, education subsidies and public utilities, such as electricity or telecommunications. Pension spending is the most ill-targeted: 73% of subsidies go to high-income households, while only 5% goes to the poorest households. In fact, Colombia is the only country in the region in which contributory pensions increase inequality (Lustig, 2016[12]). This is driven by the high share of informal jobs that lack pension coverage. Pre-school and primary education expenditure is well targeted to the poor, but the benefits of public spending on tertiary-level education mostly accrue to high-income households (Joumard and Londoño Vélez, 2013[9]). The best-targeted items are social assistance programmes, such as Familias en Acción, and although almost 40% of spending went to non-poor households in 2016 (Fedesarollo, 2021[25]), targeting has improved recently.

Subsidies for public utilities are the second most ill-targeted item, as 80% of the public spending accrued to non-poor households. Usually, subsidies for public utilities are inefficient as they distort price signals and can result in harmful consumption decisions, such as lower incentives to save energy. A cost-benefit analysis of each subsidy for public utilities could be conducted to eliminate those that are socially and environmentally harmful. Vulnerable households can be better supported by cash transfers. If subsidies cannot be eliminated, improving their targeting would at least increase the efficiency of public spending and help those that need it the most (see section 0). For example, 90% of households receive subsidies for electricity and 60% for gas (Eslava, Revolo and Ortiz, 2020[26]).

A relatively high minimum wage raises formal salaries but exacerbates informality

The minimum wage in Colombia - at 90% of the median wage and 62% of the mean wage of full-time formal employees - is high in comparison with OECD countries (Figure 2.12). International evidence on the impact of minimum wages on employment is not conclusive (Broecke, Forti and Vandeweyer, 2017[27]). However, evidence for Colombia clearly indicates that the relatively high minimum wage has a negative effect on employment, especially for workers earning close to the minimum wage (Maloney and Nuñez, 2000[28]; Pérez Pérez, 2020[29]; Mora and Muro, 2019[30]), and induces informality (Arango, Flórez and Guerrero, 2020[31]; Mondragón-Vélez et al., 2010[32]; OCDE, 2019[33]; Arango and Flórez, 2017[34]; Olarte Delgado, 2018[35]). This high relative minimum wage is, at least in part, symptomatic of a significant fraction of workers with lower labour productivity than the minimum wage, which makes it unattractive for firms to hire them as formal employees.

This high minimum wage has likely left many workers in informal jobs, self-employment and unemployment. Almost half of the total workforce earns less than the minimum wage, and this number is higher for self-employed, women, informal, young, low-skilled and rural workers (Figure 2.13), whose labour productivity is likely lower. As argued in OECD (2016[36]), the high minimum wage should also be seen in the context of the limited role of collective bargaining in Colombia. Since the minimum wage is one of the few ways for trade unions to improve working conditions for their affiliates, they tend to put strong pressure on raising it. These attempts can fail to consider the effect of minimum wage increases on informal workers. At the current high level, marginal increases in the minimum wage are likely to have regressive income effects as they reduce formal employment prospects for low-skilled workers, youth and people located in rural and less developed regions (OECD, 2015[37]).

Over time, the value of the minimum wage has increased more rapidly than consumer prices and labour productivity. Between 2011 and 2019, the average annual increase in the minimum wage exceeded inflation by about 1.6 percentage points. Labour productivity grew by an annual average of 0.3% during the same period. For 2022, the minimum wage has been increased by 10%, while inflation in 2021 was 5.6%.

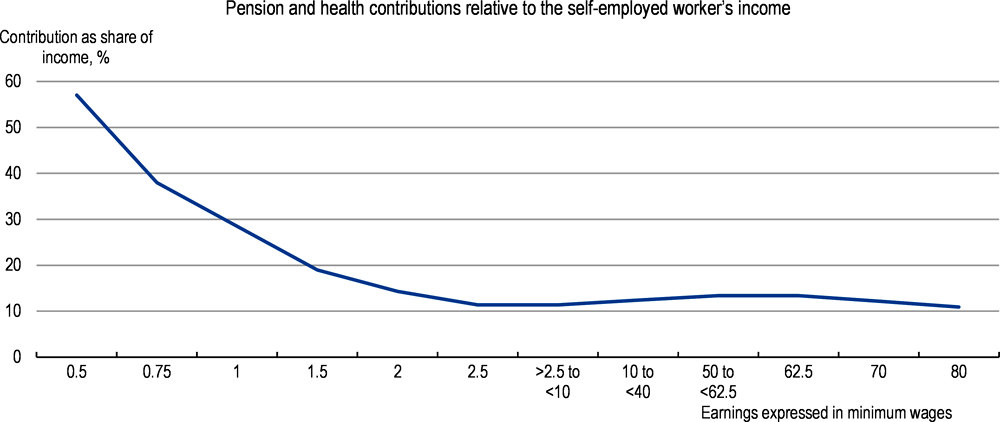

Colombia’s minimum wage is used as a gatekeeper for accessing the contributory social security system. Only salaried workers earning at least one minimum wage can contribute to the contributory pension system. For self-employed workers, social contributions cannot be based on a monthly income of less than the minimum wage. As a result, social security contributions amount to a significantly higher proportion of remuneration for those earning below the minimum wage than for other workers, which adds to the regressive nature of current arrangements. Allowing workers with incomes below the minimum wage to participate in social security, and calculating contributions bases on their actual incomes, would improve incentives for low-income and vulnerable workers to get a formal job and social insurance coverage.

In the context of the current crisis, which has disproportionately affected young people and low-skilled workers, future minimum wage increases should be approached with caution, evaluating both the effects on formal and informal workers, an issue that has been discussed in past Economic Surveys (OECD, 2015[37]; OECD, 2019[38]). Given the current level of the minimum wage, adjusting it only for changes in prices would be a reasonable approach for the next few years, as recommended in the past Colombia Economic Survey (OECD, 2019[39]).

In the medium term, a permanent and independent commission could provide recommendations on setting minimum wage increases, as in other OECD countries. For example, the process of setting minimum wages in Germany and the United Kingdom includes a systematic monitoring of its potential impact by specific independent bodies mandated to evaluate and provide recommendations (Low Pay Commission UK, 2018[40]; Eurofound, 2018[41]; Vacas-Soriano, 2019[42]). The Low Pay Commission in UK is formed by experts and academics, and is mandated to evaluate and advise the government on the impact of increasing the minimum wage. The commission conducts research and publishes annual reports to inform the debate on minimum wages and its impact on employment. In Colombia, such an independent commission could advise on the impact of increases of minimum wages on formal and informal workers. This advice could then feed into the decisions of the existing commission responsible for setting the minimum wage via social dialogue and negotiations.

Colombia could also consider to differentiate the minimum wage by age (OECD, 2015[37]) or by region (OECD, 2017[7]), as proposed in past Economic Surveys. These measures would particularly help formalisation in rural areas. For younger workers, a differentiated minimum wage would facilitate their entry into the labour market and reduce unemployment. While a unique national minimum wage is easier to operate, communicate and enforce, it offers less scope to take into account the particular circumstances of different age groups or regions, such as the cost of living and labour productivity.

Non-wage labour costs are high increasing informality

In addition to the high minimum wage, non-wage labour costs add 50% the labour costs of an average-wage worker (Figure 2.14). However, for informal workers, non-wage labour costs usually add up to 120% to their average wages (Alaimo et al., 2017[43]). Such high costs perpetuate a high incidence of informality, self-employment and unemployment.

The 2012 tax reform that reduced payroll taxes and employer’s health contributions (Box 2.3) shows that reducing non-wage labour costs helps to reduce informality. In the aftermath of the reform, labour informality declined visibly (Figure 2.15). Available impact evaluations suggest that the reform led to a 2 to 4 percentage-point reduction in the informality rate (Kugler et al., 2017[44]; Morales and Medina, 2017[45]; Fernández and Villar, 2017[46]; Bernal et al., 2017[47]). For self-employed workers, the reform implied no changes in social contributions, explaining why the effect on increased formality was stronger among employees than self-employed workers (Figure 2.16). Formalisation increased more among workers in smaller firms, as larger firms were more impacted by the simultaneous increase in corporate taxes (Bernal et al., 2017[47]). Estimates of wage effects vary, ranging from only a small effect (Morales and Medina, 2017[45]), to a positive effect of 2.7% on average wages (Bernal et al., 2017[47]). The effects of the reform have been broad-based and long-lasting, with the manufacturing, services and agricultural sectors experiencing reduced informality rates (Garlati-Bertoldi, 2018[48]).

Despite the 2012 tax reform, social contributions remain high (Box 2.3) and prevent particularly low-income workers from accessing formal employment. For a dependent formal worker earning the minimum wage, the cost of contributions and other payroll taxes amounts to 53% for an employer. Among the most costly items is a transport allowance, which is mandatory only for workers earning less than two minimum wages and is not considered in the calculation of social contributions. The only rationale behind this allowance is its exemption from social contributions, but it constitutes a big disincentive to formal hiring.

In December 2012, Colombia’s Congress approved a reform that reduced payroll taxes by 13 percentage points of wage earnings. In particular, it eliminated employers’ contributions to SENA (the public training agency) and ICBF (the childhood services agency), previously set at 2% and 3% of firms’ payrolls respectively. The reform also eliminated employers’ contributions to the health system set at 8.5% of the payroll. These payroll reductions applied only for workers with wages below ten minimum monthly wages (around 98% of formal workers). SENA and ICBF contributions were eliminated by mid-2013, while health contributions were eliminated starting in January 2014.

To finance this reduction of payroll taxes, authorities implemented a new corporate income tax (the “CREE”) of 9% over total profits, while reducing the existing corporate income tax from 33% to 25%. The goal of the reform was to stimulate formal employment, while keeping tax revenue unchanged. The reduction in payroll taxes did not apply to employers not subject to corporate income taxes, including e firms in the special tax regime, in particular, non-for-profit organizations, mainly in the education and health sector.

Table 2.2. shows all non-wage labour costs for employers, employees and the self-employed after the 2012 tax reform. The largest single elements of the tax wedge are pension contributions (12% for the employer), transport and severance allowances (11.7% and 8.3%, respectively) for the employer and pension and health benefits (8%) for the employee.

Vast evidence shows that these high mandatory contributions for social security can explain high informality in Colombia (Camacho, Conover and Hoyos, 2013[49]; Cuesta and Olivera, 2014[50]; Kugler, Kugler and Prada, 2017[51]; Kugler and Kugler, 2008[52]). The current high costs of formal labour also explain the large share of self-employment in Colombia, as firms usually evade social contributions when these are bundled with stringent labour regulations or high minimum wages (Levy, 2019[53]). Self-employed workers’ contributions are always calculated based on the minimum wage, even when they earn less. As a result, their social contributions are highest for those with low incomes (Figure 2.17). This acts as a particularly strong impediment to becoming formal (Meléndez et al., 2021[3]).

Other non-wage labour costs are related to costly and complex business regulations that hamper the formalisation of firms and jobs. The Government has been implementing a one-stop shop mechanism for all registration procedures (Ventanilla Única Empresarial), and should keep up efforts to integrate all the commercial, tax and social security procedures necessary for the opening of companies and registering formal workers (see Chapter 1). Increasing the use of digital tools would also offer the double dividend of reducing the regulatory burden, opportunities for corruption and the scope for non-compliance. The simplication of the tax system, particularly for SMEs, can be also a powerful tool to increase business, and hence employment, formalisation. Efforts in this direction have been undertaken with the new SIMPLE tax regime that will not only reduce the tax burden but also facilitates compliance with tax obligations for micro and small firms. Authorities have also implemented programmes, such as Programa para la Formalización and Crecimiento Empresarial, aiming to formalise micro and small firms.

The pension system has low coverage and is a key driver of high inequality

The Colombian pension system is complex and coverage is low, with 45% of those aged 65 and above receiving no old-age pension at all. The pension system comprises a contributory pillar formed by a public benefit-defined system and a parallel private system based on capitalisation and defined contributions (Table 2.3). Only formal-sector workers earning at least the minimum wage can contribute to these two plans. Colombia stands out in the region as one of only two countries (with Peru) with both defined-contribution and defined-benefit schemes operating at the same time. An individual worker can only contribute to or receive benefits from one system at a time, but the coexistence of two schemes operating under different rules means that two workers with identical contribution histories can acquire different pension entitlements at retirement. Additionally, a small non-contributory pillar (Colombia Mayor) provides small cash transfers to the poorest of the elderly.

The contributory pension system adds to income inequalities mainly because of the low coverage among low-income earners (Figure 2.18, Panels A and B). Currently, 25% of Colombians in retirement age receive a contributory pension and under current requirements, less than 20% of the old-aged by 2050 are expected to access contributory pensions (Bosch et al., 2015[54]).There are marked differences across populations groups. Women have a coverage of 21%, while for men the coverage is around 30%. In rural areas, less than 10% of the elderly are covered.

The low coverage of the contributory pension system reflects the low share of workers paying contributions in the context of widespread informality. Many workers who have contributed at least at some point of their careers do not manage to get a contributory pension. An additional disincentive to contribute is that when workers get their savings back, they typically get a lower return than if they had saved in financial assets. This is driven by high commissions in the private funds and the fact that returned savings are only adjusted for inflation in the public system.

The non-contributory scheme Colombia Mayor has expanded in recent years, helping to reduce old-age poverty (DNP, 2016[55]; Econometria, 2017[56]). However, this scheme covers only 39% of those older than 65 with no contributory pensions in 2019, or 29% of the population aged 65 and above. Average benefits are low, at about 60% of the extreme poverty line or USD 25 per month, which makes Colombia Mayor one of the least generous non-contributory pension systems among emerging market economies (ILO, 2021[57]). Colombia Mayor beneficiaries are in the poorest 10% of the household income distribution and receive, on average, just 0.9% of what old-age adults in the richest 10% receive (Figure 2.18, Panel C). During 2020 and related to the pandemic, Colombia Mayor reached 1.7 million beneficiaries and the amount of the transfer was doubled. Additionally, the 2021 tax reform establishes a gradual benefit convergence with the national extreme poverty line, subject to budget availability, which would increase the budget for non-contributory pensions by 50%.

Inequities in the pension system are also driven by significant subsidies for high-income earners. In the public regime, the government fills the gap when contributions fall short of outlays, which gives rise to high implicit subsidies towards relatively high-income beneficiaries. Indeed, 51% of those with contributory pensions belongs to the 20% of the richest population (Fedesarollo, 2021[25]).The average replacement rate in the public benefit defined scheme of 73% is much higher than the 39% of the private capitalisation scheme (López and Sarmiento, 2019[58]), compared to an average 58% in the OECD. The fiscal cost of the pension system, which includes several special regimes for the public sector, military forces and teachers, is also high in relation to its coverage: 3.9% of GDP in 2019, nearly 30% of the government tax revenues, and nearly three quarters of this subsidises the public scheme.

A third pillar that encourages voluntary savings for low-income Colombians is the so-called Periodic Economic Benefits Scheme (BEPS). However, design problems and the fact that the programme relies on voluntary savings by a low-income population, who have little spare income, have limited its impact and development. Although the programme's coverage has grown, the number of people who save (around 1.6% of the old aged in 2020) and the amounts saved are low (16% of extreme poverty line).

To increase pension coverage, the government implemented a new regime in 2020 to allow workers earning less than the minimum wage to contribute to BEPS. This regime, named “social protection floor” allows part-time workers earning less than one minimum wage to access old-age pensions through BEPS instead of the contributory scheme, in addition to health coverage in the non-contributory regime and additional insurance cover against labour risks (for which the employer contributes 1% of the wage). The system is mandatory for dependent and independent workers providing services and earning less than a minimum wage. Authorities are working on a system of equivalences between the contributory and BEPS systems to allow workers to save in the two systems and transfer savings from one to the other.

Potential coverage of the mandatory social protection floor, 27% of informal workers earning less than a minimum wage in 2019, is rather limited. For the rest, the social protection floor is voluntary, notably for self-employed workers who earn less than the minimum wage. After one year of implementation, only 7000 out of 9 million potential workers have started contributing through this system (El Tiempo, 2021[59]). Adding this third element as a contributory scheme with different contribution rates and rules adds to the complexity of the pension system. It also potentially creates awkward incentives, as formal workers also need to pay the 4% contribution for healthcare once their wage reaches the minimum wage. At the same time, it does not solve the issue of inadequate pension benefits and low coverage.

Achieving universal pension coverage

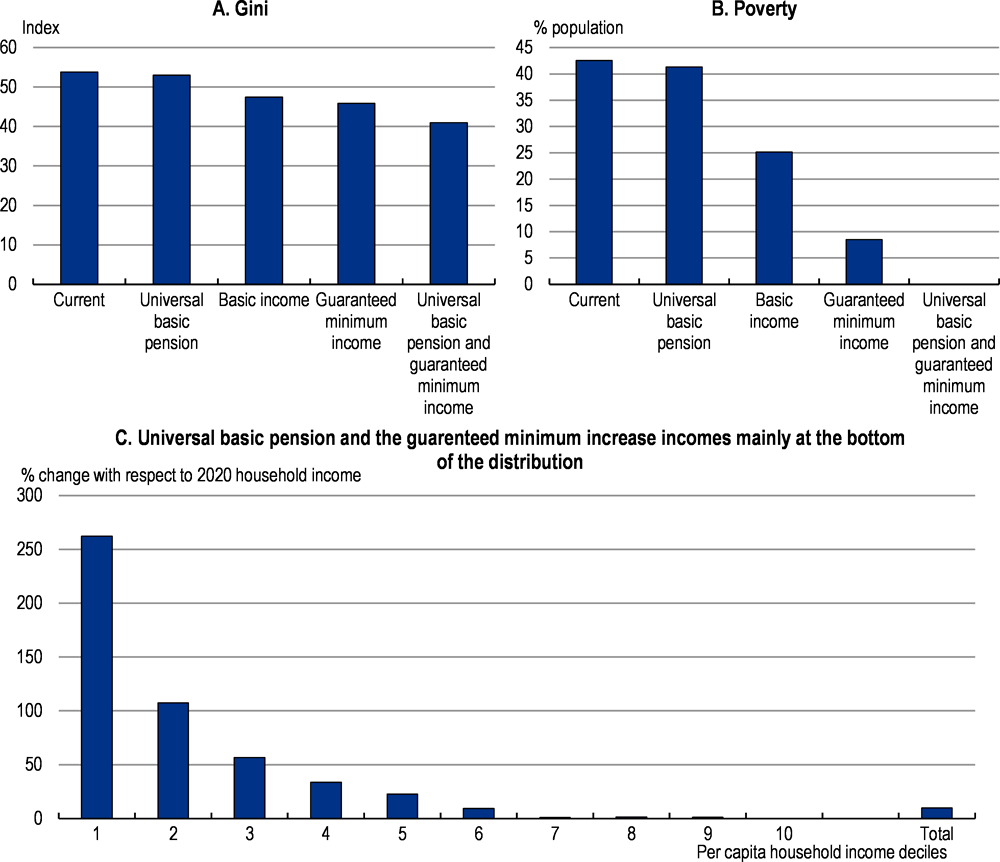

A universal minimum pension coverage would allow Colombia to achieve significant reductions in income inequalities. Universal pension coverage could be achieved by transitioning from the current complex pension system to a simpler system with three components. A first, non-contributory universal tier would provide for all residents aged 65 and above. Benefit levels would focus on reducing old-age poverty, while leaving consumption-smoothing objectives for the other components. Beyond the obvious benefits of improving fairness and social cohesion, evidence from Bolivia shows that universal non-contributory pensions helped many households to avoid poverty during a crisis such as the pandemic (Box 2.4).

The need to strengthen the incentives for formal job creation calls for shifting the financing burden of pensions away from (formal) labour towards broader sources. Essentially, this implies financing the universal pension from general taxation revenues, as opposed to labour charges. This would generate a need for mobilising additional tax revenues, which is a key priority for Colombia. As labour charges are reduced, additional tax revenues could come principally from personal income taxes, which few Colombians currently pay and whose potential progressivity is undermined by a wide array of exemptions and special regimes, and from value-added taxes, where revenue collection is undermined by exemptions and reduced rates (see Chapter 1).

Bolivia is the only Latin American country to have established a near-universal non-contributory pension programme in 2008 (Renta Dignidad). This is the first component of a pension system that includes a mandatory scheme of individual accounts and a solidarity scheme. The programme disburses around USD 50 each month to individuals aged 60 or older, regardless of their income, and reaches around 28% of Bolivian households. Disbursements per beneficiary represent around 80% of the poverty line.

Evidence shows that this programme has significantly reduced poverty and increased income security (UDAPE, 2013[60]). During the pandemic, the programme was crucial for preventing a decline in food security, reduced financial insecurity and stress, with the greatest impacts on low-income households and those that experienced a large labour market shock. This evidence suggests that, during an economic crisis, an established, near-universal non-contributory pension programme can protect poor and vulnerable households against economic shocks (Bottan, Hoffmann and Vera-Cossio, 2021[61]).

The second component of the pension system would be a mandatory contributory scheme, financed by workers and employers’ contributions. Benefits from this scheme would top up the benefits from the first universal component. This second component should be mandatory as workers usually do not save enough for consumption smoothing over their lives. Mandatory contributory rates could be progressive, starting at zero for wage earners below and around the minimum wage and increasing gradually for higher wages. To ensure adequate pensions and fiscal sustainability, contribution rates could be calibrated to achieve replacement rates of at least 50% of pre-retirement earnings, close to the average OECD replacement rate for men (59%). Finally, a third tier of individual voluntary savings could complement the other two pillars.

This second component could be based on the current contributory pension system. But that would require a deep reform of the current contributory pension system, which is excessively complex, as analysed in a thematic chapter in the 2015 OECD Economic Assessment of Colombia (OECD, 2015[37]). This need for a comprehensive reform is also acknowledged in several reform proposals in Colombia, including by major domestic institutions such as ANIF, Colpensiones, Fedesarrollo and by Bernal, et al. (2017[62]). The track record of systems with a co-existence of parallel pay-as-you-go and capitalisation set-ups is rather weak as they add to complexity and distortions, especially when beneficiaries can arbitrage between the systems through frequent switching opportunities. If the public defined-benefit scheme continues to exist, phasing out ill-targeted subsidies and eliminating competition between the private and public schemes would be key for equity and fiscal sustainability. This would benefit from a parametric reform that links the retirement age to life expectancy and determines benefits on the basis of life-time wages instead of the last ten years of wages, as the latter leads to high implicit subsidies.

An alternative would be a defined-contribution notional-account pension scheme. This would reduce fiscal uncertainty and support financial sustainability, as it would not be vulnerable to potential imbalances arising from demographic or economic changes (Lora, 2014[63]). The accounts would be “notional” in that the balances exist only on the books of the managing institution and, upon retirement, the accumulated notional capital is converted into a stream of pension payments. Notional-accounts schemes exist in five OECD countries (Italy, Latvia, Norway, Poland and Sweden). They have proven effective in some countries for advancing reforms of pay-as-you-go systems that would face more political resistancein the more traditional terms of parametric reform of defined benefit formulas. These reform results include the use of lifetime wages for determining benefits, adjustments to reflect growing longevity and declining fertility, and incentives for older workers to remain in the labour force and pay contributions.

Maintaining the private capitalisation scheme instead would have the advantage of establishing a clear link between contributions and benefits, incentivising workers to contribute regularly. As the first component of the system is financed through general taxation, a second tier based on private capitalisation would allow to diversify funding sources, which is generally considered an advantage (OECD, 2016[64]). However, under private capitalisation schemes, workers tend to face some uncertainty about their future pensions, as these are defined at retirement and are sensitive to current capital returns.

The Chilean pension system provides an interesting model to consider (Box 2.5), as it is efficient in redistributing resources to the most vulnerable while minimising distortions on the labour market (Morales and Olate, 2021[65]). Colombia could consider a reform in which the first universal basic pension could be integrated with the individual accounts, while having public subsidies for those with low accumulated contributions to ensure a guaranteed minimum pension. Another good example from OECD countries is the Australian pension system. It has three components: a means-tested non-contributory component (“Age Pension”) that reaches 75% of the elderly; a superannuation guarantee with a compulsory employer contribution to private superannuation savings; and a voluntary superannuation contributions and other private savings (OECD, 2021[66]). Superannuation savings are encouraged through tax incentives. The Age Pension is designed to provide a safety net for those unable to save enough through their working life and to supplement the retirement savings of others. The Superannuation system, a defined contribution scheme, is not subject to financial sustainability issues and as the system reaches full maturity, fewer individuals will be reliant on the Age Pension safety-net.

Chile’s pension system has three components: a redistributive first tier, a second tier of mandatory individual accounts and a voluntary third tier. These components complement each other and act as a guaranteed minimum pension. The individual accounts system was introduced in 1981, while the redistributive tier was introduced in 2008 to expand coverage and provide a basic benefit to a larger share of the population.

In Chile, pensions are based on defined contributions, but the government provides subsidies to ensure that everyone receives a pension of at least a defined threshold, the basic solidarity pension. The basic solidarity pension is payable from the age of 65 to the poorest 60% of the population. For those without accumulated savings in the individual accounts, the minimum pension is equivalent to a third of the minimum wage (USD 150 equivalent to 60% of the poverty line). For those having at least some accumulated savings, the government provides subsidies that are decline as the pension obtained through a worker’s own resources increases in value, up to another threshold, the maximum pension with solidarity support (equivalent to USD 450 or 1.2 minimum wages). The mechanism is progressive because, even if workers have the same spells of formality during their lifetimes, low-income workers would, in absolute terms, accumulate less than high-income workers and thus receive larger subsidies (UNDP, 2021[5]). Workers never lose their contributions, and pensions increase with individual savings. The system also provides women with children with a one-time monetary transfer at retirement age.

The Chilean system suffers from low replacement rates of around 52% for men and 29% for women when including the solidarity pillar (Morales and Olate, 2021[65]). This is partly related to the relatively low total contributions during working years. The government allocated 0.7% of GDP to subsidise pensions for 1.5 million retirees in 2018. Recently, the authorities have increased the amounts of the solidarity pensions (by 50% for the basic pension and 34% for those receiving subsidies) in response to social unrest at the end of 2019. This is a first step towards improving the pension amounts of the lower-income population. The spending on pensions subsidies increased to 0.9% of GDP in 2020. A pension reform has been in discussion for a long time, increasing the contribution from employers, who currently do not contribute (only workers contribute 10% of their wages), to the individual accounts of workers. Under this proposed reform, the total contribution rate will be 16% of wages (OECD, 2021[67]).

Colombia has achieved almost universal healthcare coverage, with 97% of population covered by the public health system in 2020. This system achieves very high financial protection, with out-of-pocket expenditures below the OECD average and the lowest in the LAC region. This is a remarkable achievement and one of the highest coverage rates in the region (Figure 2.19).

However, the public health system consists of two parallel schemes, a contributory scheme for formal workers and a non-contributory scheme, incentivising informality for a number of reasons. First, the non-contributory system offers nearly the same services as the contributory one, with the exception of disability allowance and maternity leave, but is free of charge. Second, part of formal workers’ healthcare contribution is used to cross-finance the non-contributory system and thus effectively taxed away. Finally, workers face a temporary discontinuity in healthcare coverage when an individual switches between systems as a result of a change in employment status. These switches can also affect the quality of care as medical files and treatment histories are usually not shared across the two systems.

Fostering formalisation without jeopardising universal health care coverage

Improving incentives to formalise while keeping good health coverage would require shifting much of the financing burden of public healthcare away from formal labour charges and towards general taxation, especially around the minimum wage where disincentives are highest.

Moving towards a single, universal health care system financed through general taxation, as opposed to social contributions paid by workers, would allow reducing by 4 percentage points the cost differential between formal and informal employment, all of which is currently paid by the employee. For self-employed workers, this would reduce the cost of formal labour by 12.5 percentage points, or even more for those earning less than a minimum wage. By not discriminating between formal and informal workers, contributing or non-contributing workers, this type of financing of the health system would boost formality (Levy, 2019[53]).

A second option that could be implemented at no fiscal cost is to unify the two systems and keep the financing through labour charges, but shift more of the burden of contributions into higher income ranges, away from the vicinity of the minimum wage. One recent proposal is to set an initial contribution rate for salaried or self-employed workers at zero if they earn up to one minimum wage or less, and increase the rate gradually up to a maximum for workers earning 25 minimum wages (Fedesarollo, 2021[25]). This would leave the average contribution rate in the contributory scheme at around 4% of wages, implying no fiscal cost, but more progressive contributions.

Health contributions generate even stronger disincentives to formal job creation in firms subject to the “special tax regimes”. This tax regime features an additional 8.5% employer health contribution, as the regime was not included in the 2012 reform due to its exemption from corporate taxes. Reducing healthcare-related labour charges and the associated distortions is particularly important in these firms, which account for 16% of all formal employment, mainly in the sectors of education and health. As these sectors provide work for 26% of female workers, reforming them would help to improve gender equality.

In addition to pension and health contributions, employers pay a 4% contribution to finance the family compensation funds (Cajas de Compensación Familiar), which offer a wide range of services from housing, education, and training programmes to sports and entertainment for affiliates. Family compensation funds have increasingly been mandated by the government to provide benefits and services to non-affiliates. Still, their financing continues to rely uniquely on formal-sector labour charges (OECD, 2016[36]). Moreover, many of the funds’ services are located in the regional capitals and are unavailable to formal employees in smaller cities or those living in the periphery. As a result, an increasing part of the contribution is in reality a tax on formal labour, used to finance social policy programmes for which formal workers are not eligible. For most formal workers, the benefits perceived fall short of the costs of the contributions, thus incentivising informality (Levy, 2019[53]).

Services currently provided by Family Compensation Funds could be subjected to a comprehensive cost-benefit and impact evaluation to determine which services offer sufficient value for money to be maintained, particularly in light of other changes in social benefits. These services could then be made available regardless of labour status and equally across the country, as the substantial variation in the quality of services offered by the different funds currently exacerbates inequalities.

As with pensions, the unintended consequences of non-wage labour charges on formal job creation call for a broader approach to raising revenues for financing general social services and benefits, including the benefits provided by Family Compensation Funds. A shift towards financing those services deemed worth maintainint through general tax revenues can subtract 4 percentage points from labour charges and significantly strengthen the incentives for formal job creation.

If this proves politically too difficult, a temporary improvement would be to transform the current flat contribution rate into a progressive rate that spares out low-income workers, for whom formalisation incentives are most relevant. A recent revenue-neutral proposal suggests a zero contribution around the minimum wage that rises with income, but remains low below two minimum wages (Fedesarollo, 2021[25]). In this case, a centralised contribution collection system would transfer resources to the funds based on the services actually provided to low-wage members and on the number of members, considering the quality of services delivered. This would be a fundamental first step towards ensuring the progressivity of the funds and strengthening the government's position on the use of resources.

Social assistance programmes have low coverage

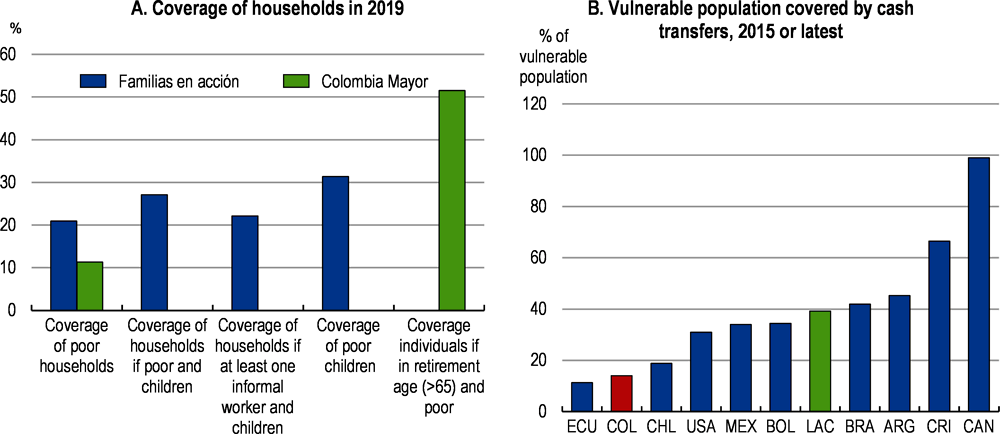

Due to the low coverage of social insurance contributory schemes, cash transfers programmes aim at protecting those left behind by social security schemes, typically informal workers in poor households. Among poor households, 83% had all their employed members working informally in 2019. The main programmes (Table 2.4) are Familias en Acción (Families in Action), a conditional cash transfer programme to fight poverty; Jóvenes en Acción (Youth in Action), which provides incentives to young people for entering and completing higher education; and Colombia Mayor, the non-contributory pension scheme described above.

Evaluations suggests that these social programmes have contributed to reducing poverty and raising well-being of households. Familias en Acción has significant impacts on dimensions such as educational attainment, nutrition and other dimensions of life quality (Angulo, 2016[68]), in addition to reducing extreme poverty, poverty and multidimensional poverty (DNP, 2008[69]; DPS, 2020[70]). On the other hand, some evidence suggests that being a beneficiary from Familias en Acción may increase the probability of being informal, since having a job in the formal sector increases individual income and reduces the probability of being eligible (Saavedra-Caballero and Ospina Londoño, 2018[71]). Jovenes en Acción has had positive effects on earnings and employment prospects, including formality, in the short and in the long run, and increased education for participants and their relatives (Attanasio, Kugler and Meghir, 2011[72]; Attanasio et al., 2017[73]; Kugler et al., 2020[74]).

The coverage of cash transfers programmes is low, leaving many poor households without any support (Figure 2.20). 52% of poor households do not receive any support from the state. Only 13% of households with all members working informally received Familias en Acción in 2019. Insufficient programme resources are the main reason for this low coverage. In 2019, only 2.7 million families were targeted, out of 4.3 million households in poverty. The coverage is similar in rural and urban areas, but poverty is higher in rural areas, although less-educated households in remote areas are more difficult to reach. Moreover, the system lacks policies to protect the middle class from temporary shocks that may affect their income or assets.

Benefit levels of social assistance transfers are low. Familias en Acción provides financial support equivalent to less than 5% of average monthly GDP per capita in 2019 (USD 23 or 22% of the poverty line), one of the lowest in emerging markets (ILO, 2017[75]), where on average is 15% (Gentilini et al., 2021[76]).

Other social assistance programmes are designed to support productive inclusion and entrepreneurship, or to cover specific needs of certain population groups. The design of these programmes aims to cover all the life stages and the conditions necessary for a person or family to enter the labour market, self-generate income and improve their life quality. However, there is a lack of coordination of these efforts, a lack of comprehensiveness in the strategies defined to cover different risks, which reduces the efficiency of the social assistance system. Aware of these challenges, authorities set up an equity roundtable (Mesa de equidad) in 2019 formed by the president and all the ministries, to coordinate and prioritise the offer of social programmes among all institutions offering social services and the implementation of the poverty alleviation route. In 2020, the management of all cash transfers programmes was centralised under a single public entity, which is a welcome step to reduce fragmentation.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated some important changes in social policy

In response to the pandemic, the authorities launched a comprehensive social response to protect the poor and vulnerable (Figure 2.21). Policies included a series of additional emergency cash transfers through the pre-existing programmes (Colombia Mayor, Jóvenes en Acción, and Familias en Acción) and two new programmes: Ingreso Solidario (Solidarity Income) and a VAT compensation programme. In addition, discounts on the payment of basic services have been implemented, as well as other budgetary and financial measures in order to protect household incomes. Some local governments also implemented support programmes for vulnerable households, such as Bogotá, Bucaramanga or Medellín. Spending in the social emergency programmes made through the emergency mitigation fund was stepped up by 0.8% of GDP in 2020 and 0.5% in 2021 (Ministry of Finance, 2021[77]).

The social response was key to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on household incomes and poverty (Figure 2.22). By expanding the number of beneficiaries and increasing the level of benefits, social programmes supported household incomes, including for some well-off households. In particular, this support completely offset the effect of the crisis on households in rural areas, who saw their real income grow. The emergency transfers mitigated the increase in poverty nationally by 2.2 percentage points during 2020.

The main existing programmes saw benefits and coverage increase as households received extraordinary payments through existing programmes during 2020. The eligibility threshold for Familias en Acción was expanded, bringing in many households identified as economically vulnerable. Families previously excluded over failure to comply with conditions were quickly re-enrolled. The programme also temporarily waived its usual conditionality, as the lockdown made these conditions far more difficult to meet. Jóvenes en Acción widened its age coverage to reach new beneficiaries (now between 14 and 28 years old). Though this move was planned prior to the pandemic, its implementation was fast-tracked, and officials plan a further expansion that will bring in an additional 200,000 young people.

A new cash transfer programme called Ingreso Solidario was designed and implemented in record time to support informal workers. The new programme provides a non-conditional cash transfer to poor and low-income households that are not beneficiaries of pre-existing social assistance programmes. The programme assisted up to 3 million households with COL 160 thousand (USD 40, around half of the poverty line in 2020) from March 2020. The programme was designed initially for three months but then extended several times. In the fiscal reform of 2021, the authorities extended it further until end of 2022, increasing coverage to 3.6 million individuals in extreme poverty, reaching 4.1 million households. In 2022, Ingreso Solidario is expected to cost COP 7.2 trillion (around 0.6% of GDP) and to reduce poverty to pre-pandemic levels, according to Government estimates. From July 2022 onwards, eligibility criteria will be tightened as the benefit needs to consider the size and vulnerability of the household.

A key innovation of Ingreso Solidario is its use of bank accounts and mobile wallets for benefit disbursement, which helped to promote financial inclusion (Gallego et al., 2021[78]). The use of mobile wallets more than doubled during 2020 and 2.6 million beneficiaries of cash transfers received their payments through digital channels, 21% more than in 2019. Building on this progress can translate into increased opportunities for savings, access to affordable credit and other financial services for many households who, prior to the programme, were outside social safety nets and at the margins of the financial system. This would require effectively providing access to financial education to ensure that access translates into effective and safe usage.

According to early evaluations, Ingreso Solidario had positive effects on household income, food consumption and education (Gallego et al., 2021[78]). The programme increased incomes for those most affected by the pandemic, while not generating disincentives to labour market participation. It also increased households' expenditure on education and the time children dedicated to school activities.

Another new means-tested unconditional cash transfer programme, called the VAT compensation for vulnerable households, was introduced in March 2020 to make VAT less regressive. The programme was originally planned to be implemented during 2020 as a pilot for 100,000 families but with the pandemic, its rollout was accelerated and expanded to one million households. The transfer consists of COP 75 000 (USD 20 or 55% of the extreme poverty line in 2019) distributed every 5-8 weeks to beneficiaries of two existing social welfare programs benefitting low-income families and elderly: 700,000 households in Familias en Acción and 300,000 households enrolled in Colombia Mayor. Early evaluations suggest that the transfer has had positive (albeit modest) effects on household welfare measures such as financial health and access to food (Londoño-Vélez and Querubín, 2020[79]).

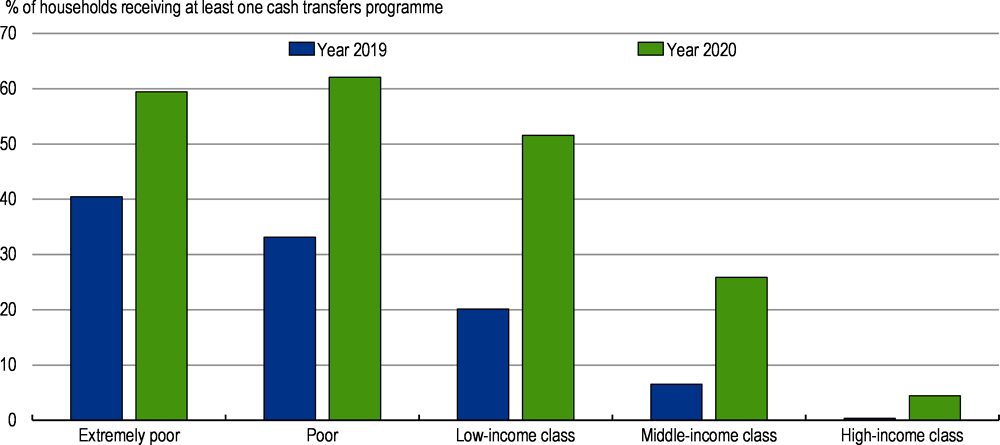

The COVID-19 response in Colombia marks an inflection point for Colombia and the future of cash benefits. The crisis response represents an opportunity to consolidate access and increase coverage of social programmes for the most vulnerable. However, even now the coverage of households receiving cash transfers remains low (Figure 2.23) and Ingreso Solidario covers only around 20% of informal workers (Blofield, Lustig and Trasberg, 2021[80]), leaving many unprotected.

From emergency to permanent support: a single cash benefit programme for the poor

Protection against poverty and income losses could be improved by unifying and integrating existing cash transfers into a single programme. One option would be to establish a guaranteed-minimum-income scheme for the population aged below 65, which would complement the incomes of those living in poverty. This programme could become the prime instrument for fighting poverty and provide a backstop to those who lose their livelihoods temporarily in the case of dismissal or income loss. It could be complemented by other social programmes that aim at improving household assets and human capital.

A guaranteed minimum income is a periodic cash transfer to supplement the income received by poor households to reach a certain minimum income level. Financed from general taxation revenues, such scheme could build on existing conditional and un-conditional cash transfers for the vulnerable and poor (Familias en Acción and Ingreso Solidario). The amount given to each household would be contingent on the household's own income (both from formal and informal jobs) and assets before the transfer. If the household has no income, the transfer would be made for the entire minimum income. The cash transfer would decrease gradually as household income increases, until reaching the point in which the household does not receive any transfer. Changes expected in Ingreso Solidario from July 2022 go in this direction as the amount of the benefit will consider the size and vulnerability of the household. Such benefit is different from the existing cash transfers that provide a fixed level of cash transfer to poor households independent of the household or individual income (usually called basic income schemes). It is also different from the Universal Basic Income, which grants an identical amount to every citizen, regardless of income (Box 2.6).

A universal basic income (UBI) is an unconditional cash transfer granted at regular intervals to all residents, regardless of their wealth, earnings or employment status. The main advantage of such a programme is that it is simply to implement as no conditions or requirements are applied.

The main disadvantage of an UBI is that it could be extremely costly. An unconditional payment to everyone at meaningful but fiscally realistic levels would require strong tax rises and possibly reductions in existing benefits, and would not often be an effective tool for reducing income poverty (OECD, 2017[81]). Some disadvantaged groups would lose out when existing benefits (usually all other social programmes) are replaced by a universal basic income, illustrating the downsides of social protection without any form of targeting at all.

The Universal Basic Income is fiscally unviable in Colombia and can be controversial by guaranteeing transfers to high-income earners. Setting the monetary transfer to the extreme poverty line to every household member to assure that the most basic needs of all Colombians are satisfied even if no other income is available, would have a cost of 8.7% of GDP in 2020. This UBI levels still would leave many households in poverty, especially those at old-age not receiving any pensions or the unemployed or inactive. If the transfer is set to the poverty line the cost would be 20% of GDP, almost equivalent to the tax revenues in Colombia (19.7% of GDP in 2019).

The programme would deliver unconditional cash transfers for every adult living in a poor household, in line with the Ingreso Solidario programme. When children are part of the household, the cash transfer can be conditional on human capital accumulation and desired health behaviours, as in the Familias en Acción programme, to generate incentives for investing in education and health. In line with the current Familias en Acción programme, benefit levels can take into account children’s age and educational level.

A large body of evidence suggests that unconditional cash transfers can achieve significant reductions in poverty. These cash transfers can promote credit access, better eating habits, better school attendance, better academic results, better cognitive development, reduction of domestic violence, and female empowerment (Banerjee, Niehaus and Suri, 2019[82]). Evidence on the impact of cash transfers on labour participation and formal employment are mixed. While some evidence suggests that cash transfers do not discourage - and in some cases even encourage - labour participation by beneficiaries (Banerjee et al., 2017[83]), other evidence from the region suggests that transfers can decrease incentives to participate in formal employment (Bergolo and Cruces, 2021[84]). This is usually linked to abrupt benefit withdrawals for beneficiaries who find a job or earn more, which can imply high implicit tax rates for workers who lose the transfer if they earn additional income that lifts them above the threshold stipulated in the targeting mechanism to qualify.

To maintain the incentives for (formal) work, it is important that the programme has a graduation phase, in which the value of the transfer forgone is smaller than the additional income. This is important to strengthen work incentives and graduation from the programme, as otherwise beneficiaries might be reluctant to take up work for fear of losing their benefit. The design could include a phase in which for every additional peso earned by the household or individual, only some part of the self-declared additional earnings, which includes both formal and informal earnings, are taken into account to calculate the cash benefit, until gradually reaching a point where no subsidy is available at all (Reyes, 2020[85]). Preliminary and ex-post impact assessments should be systematically conducted to evaluate the effects on (formal) labour force participation and adjust the design if necessary. Spain introduced a similar measure in 2020 with the new Minimum Subsistence Income, a guaranteed-minimum-income scheme. Adults without jobs should register with the public employment services and when they find a job, part of their wage will be temporarily exempted from the calculation of the benefit. For those adults already working, more hours worked and better jobs are encouraged, and for each extra income they earn the benefit is reduced by a smaller amount.