copy the linklink copied!Introduction

copy the linklink copied!The right to access information: a challenge for democracy and public governance

The right to access information plays an essential role in democratic, pluralist societies. Known in English as “sunshine laws,” this right allows the public to know more about state and public sector actions, and it constitutes the corollary of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.1 This right is applied with varying levels of strictness, depending on the country.

In general, the right to access information modifies public governance. It strengthens citizens’ interest in public affairs and enables them to make more informed contributions to decisions that affect them. Citizens thereby form an opinion of the society in which they live and of the authorities that govern the society. Knowing that its actions can be examined, understood more clearly, and monitored, a government abandons the culture of secrecy to act more openly and, ultimately, more effectively. The right to access information leads towards a culture of transparency and accessibility that ascertains the legitimacy of the civil service. A relationship of trust between public authorities and citizens grows alongside a more thorough oversight of the integrity of public officials.

For more than 15 years, the OECD has been working on projects that promote open government and, in collaboration with member countries and partners, on designing and implementing legal, regulatory, and institutional frameworks that favour transparency, stakeholder participation, and access to information. This report forms part of this collaboration and highlights the implementation of transparency, stakeholder participation, and accountability through the right to access to information.

copy the linklink copied!A renewed right in OECD countries

After the Second World War, countries that are now OECD members made the development and observance of the right to information one of their primary concerns. Since its creation in 1961, the OECD was quick to express its firm commitment to the observance and promotion of this right in order to guarantee a more open, transparent society. As a result, all OECD member countries have very advanced laws on the right to information and, largely, on the respect of this right.

copy the linklink copied!A more recent achievement and development in the MENA region

The right to access information has been slow to develop in the MENA region,2 even though Jordan played a pioneering role by passing a law on access to information in 2007. Nevertheless, political and civil society in the region has been making insistent requests to exercise this right.3 In some countries, the 2011 revolutions provoked regime changes and amendments to constitutions, as well as significant evolutions to the laws on access to information, especially in Tunisia, Lebanon, and Morocco. The growth of access to information nevertheless remains difficult and slow.

copy the linklink copied!Enacting principles of open government4 at the central and local levels

To increase the transparency of the public authorities’ actions, the accessibility of information and public services, and the government’s embrace of new ideas, demands, and needs, some MENA countries are trying systematically to integrate initiatives to create more openness in the government’s work at the central and local levels. In particular, they have adopted new tools and mechanisms to encourage stakeholders to participate in the various stages of drafting public policies.

In the context of the Open Government Partnership, which Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia have joined, governments have drafted action plans in collaboration with civil society that entail measurable commitments to enacting reforms. Similarly, the new constitutions of Tunisia and Morocco consecrate the founding principles of open government: the protection of human rights, democratic participation, decentralisation, access to information, freedom of the press and of association, and the right to high-quality public governance, transparency, and integrity. Furthermore, the trend towards decentralisation underway in Morocco, Tunisia, and Jordan leads to new forms of cooperation between citizens and public officials at the subnational level. However, this progress does not mean that much remains to be done before these political commitments to a more open government will have an actual effect on all of society, including on women and youth (OECD, 2016).

copy the linklink copied!The right to access information: difficulties and evolutions

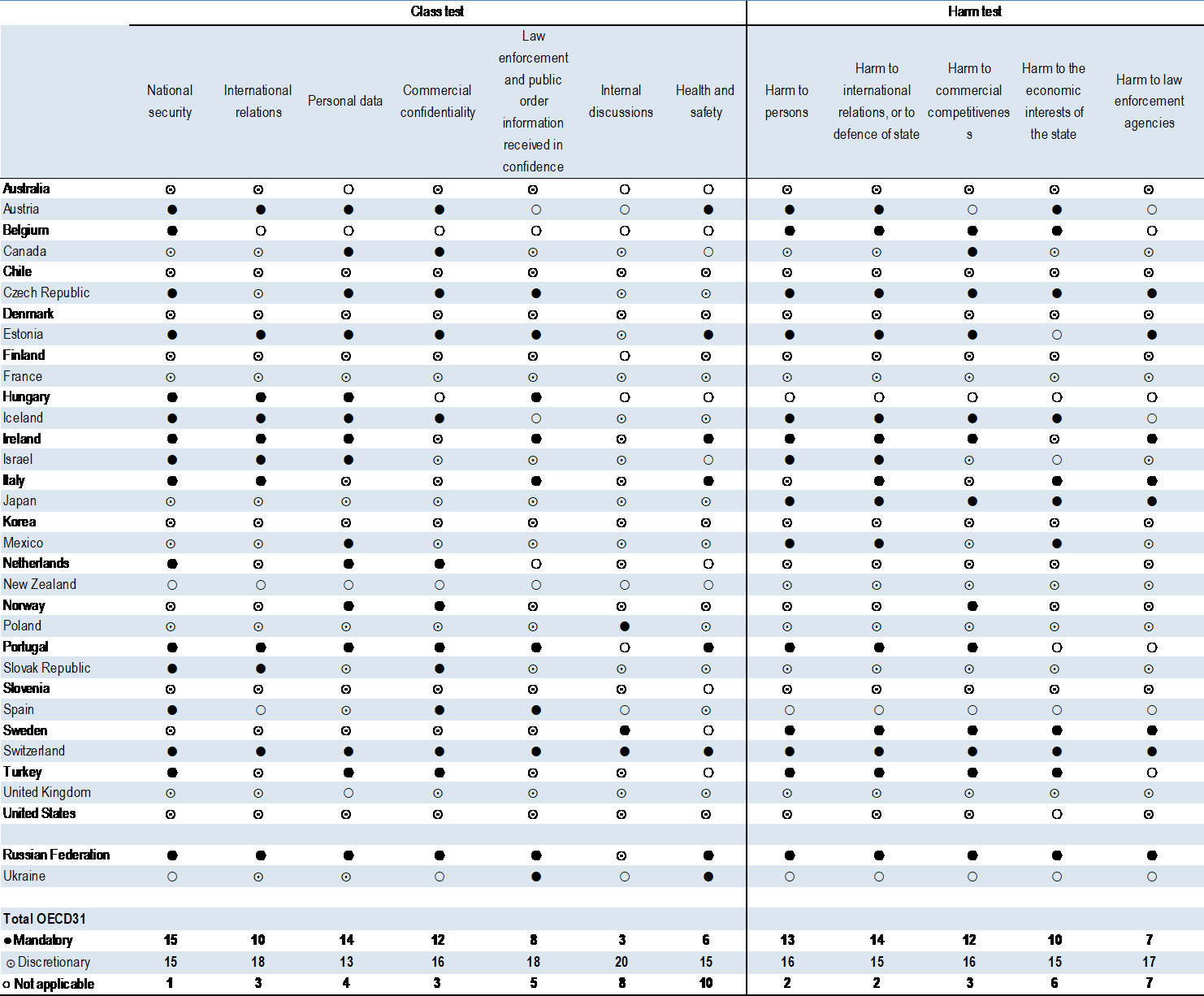

The right to access information is certainly not without its critics, especially regarding the limited number of persons and kinds of information in question. Moreover, too many laws have provisions that compete with the law on access to information.5 These provisions are at times superfluous in relation to other laws that either already mandate the communication of information (for example, the regulation on public inquiries into urban planning), or that prohibit the communication of certain kinds of information (for example, attorney-client privilege). More generally, exceptions to the right to access information, especially those based on the concept of public interest; appear to some as being too many and too confusing. As a result, the central governments of OECD member countries apply restrictions to the access to information based on varying criteria and kinds of harm (Table 1).

According to other criteria, the steps for accessing information and the related costs of the procedure and reproduction of information are too onerous for citizens. Governments or other responsible persons sometimes appear to neglect to apply the law in an attempt to shirk their obligations. In particular, certain institutions guaranteeing access to information do not have the human and material resources required to fulfil their missions. Technologies, which are evolving rapidly and recent progress at the international level, also raise new questions. In fact, information increasingly takes the form of electronic files stored independently and reorganised according to algorithms that manage databases and other metadata. Lastly, new forms of communication, such as messages sent via PINs and SMS raise new challenges to be overcome to protect the rights of persons who make requests.6

Therefore, the challenge no longer lies solely in refashioning legislation and reforming government; it involves an evolution of attitudes and the abolition of a culture of secrecy, nationally and locally, in a world where the concepts of information and information media are changing constantly and quickly.

All these changes remain to be understood fully in light of the democratic goal of equal rights and the simplified access to information. Ultimately, every citizen, following a proactive initiative by the government or after making a request, should enjoy access to all government databases understood in the broadest sense, in total transparency. The challenges and obstacles against this vary according to the country and areas of application.

copy the linklink copied!Institutions guaranteeing access to information

Public authorities use different means to render the right to access information effective. Logically, the first consists of passing laws that establish the terms and conditions for applying this right, for example by mandating the automatic publication of government documents, or, for those entities holding information, its transmission to the persons requesting it.

Furthermore, when persons requesting access to information consider themselves deprived of their right, the laws prescribe the right to appeal decisions that deny this right of access. To this end, they first require the entity obligated to provide the information to review its own decisions through an administrative appeal process (for reconsideration or to a higher body). They then entrust this review to the competent judicial authority or another institution, which may carry out this mission by itself or in conjunction with others.

The concept of access to information involves at least two, distinct functional realities: the obligation for the persons involved to communicate the information they possess, and the obligation to protect personal data during its collection, processing, and preservation.

These functions are exercised with varying degrees of specialisation in OECD countries. Some IGAIs, like the French, Italian, and Portuguese Commissions for Accessing Government Documents, are essentially responsible for communicating information. The French National Commission on Informatics and Freedoms, the Italian Guarantor Authority for the Protection of Personal Data,7 and the Portuguese National Commission for the Protection of Data8 are specialised in protecting data. Other IGAIs, such as the Information Commissioners in the United Kingdom, Australia, carry out both of these missions at the same time. These two missions may be fulfilled by one sole body even in concomitance with other, very varied missions, as is the case with the Ombudsman’s Office in Northern European countries.

There is no provision of international law that expressly requires states to establish a body that ensures the right to access information. However, according to provisions of Inter-American law to which several OECD countries are subject, they are obligated to a general, positive action to protect the right to information.9 One of the most effective means of satisfying this obligation consists of creating an institution guaranteeing access to information. More specifically, in its 2002 Recommendation on access to official documents, the Council of Europe stated in Principle IX that: “1. An applicant whose request for an official document has been refused, whether in part or in full, or dismissed, or has not been dealt with within the time limit […] should have access to a review procedure before a court of law or another independent and impartial body established by law. 2. An applicant should always have access to an expeditious and inexpensive review procedure, involving either reconsideration by a public authority or review [...]”10. In its 2007 review of the right to access information within the region of its jurisdiction, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe also included within its analysis essential legal elements for the existence of a specific guarantor body, and it recommended the creation of such a body to all its member states.

Experience generally shows that IGAIs play a fundamental role in promoting a culture of access to information, the general application of the right, the individual access of persons requesting the communication of certain pieces of information, and the evolution of this right. Consequently, in the last thirty years, a number of countries have adopted or improved their laws on the right to access information and established institutions responsible for ensuring their application.11

In this context, characterised by a significant growth of the right to access information in OECD member countries and some MENA region countries on one side, and by the growing role played by IGAIs among OECD member countries and the establishment of new IGAIs in certain MENA region countries on the other side, the OECD secretariat became more interested in the functioning of IGAIs, especially regarding the proactive communication of information and the requests for information held by entities obligated to communicate this information.

This report forms part of the OECD’s work on open government and the MENA-OECD Governance Programme, which has provided its support to MENA region countries since 2012 in the elaboration and implementation of public policies that promote transparency, stakeholder participation, and accountability in consultation with citizens and civil society. Access to information forms an integral part of the Open Government Partnership and is a condition for becoming a member. Jordan, Tunisia and Morocco have joined the Open Government Partnership, and Lebanon intents to join.

The first part of this report examines the status of IGAIs in OECD member countries, based on examples and with an emphasis on proactive disclosure and information requests. The second part presents the case of Jordan, which has the oldest legislation on the right to information in the region, and Tunisia, Lebanon, and Morocco, which have recently adopted or amended their legislation in this domain.

Reference

OECD (2016), “Strengthening governance and competitiveness in the MENA region for stronger and more inclusive growth, OECD Publishing, Paris”, http://www.oecd.org/publications/strengthening-governance-and-competitiveness-in-the-mena-region-for-stronger-and-more-inclusive-growth-9789264265677-en.htm

Notes

← 1. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the UN General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948.

← 2. United Nations, “Public Sector Transparency and Accountability in Selected Arab Countries: Policies and Practices”, New York, 2004, https://publicadministration.un.org/publications/content/PDFs/E-Library%20Archives/2005%20Public%20Sector%20Transp%20and%20Accountability%20in%20SelArab%20Countries.pdf

← 3. See: UNESCO, Accéder à l’information c’est notre droit – Un guide pratique pour promouvoir l’accès à l’information publique au Maroc [“Accessing information is our right – A practical guide to promoting access to public information in Morocco”], UNESCO 2014, Rabat. As well, a training of trainers guide, 2019, Rabat.

← 4. Open government as it is defined in the OECD Council recommendation on open government is “a culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability, and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth”, www.oecd.org/gov/Recommendation-Gouvernement-Ouvert-Approuv%C3%A9e-141217.pdf.

← 5. In Belgium, approximately 15 laws published at the federal regional, and municipal levels deal with access to information.

← 6. Legault, S., Modernisation de la Loi sur l'accès à l’information, [“Modernisation of the Law on Access to Information”], lecture at the Canada School of Public Service, 24 September 2012, http://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/fra/med-roo-sal-med_speeches-discours_2012_8.aspx.

← 7. Garante per la protezione dei dati personali, Law No. 675 of 31 December 1996.

← 8. Comissão de acesso aos documentos administrativos, https://www.cnpd.pt/english/index_en.htm (website).

← 9. In the matter of Claude Reyes et al. v. Chile, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights noted the state’s positive obligation of ensuring the protection of the right to information, and it emphasized that this entails both the obligation not to interfere with this right and the taking of positive steps to ensure its exercise.

← 10. Council of Europe, 2002 Recommendation Rec(2002)2 by the Committee of Ministers on access to official documents (adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 21 February 2002), https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectId=09000016804c6fcc

← 11. Between 2007 and 2012, at least 20 states passed laws on the right to access information. See Legault, S., Modernisation de la Loi sur l'accès à l’information, [“Modernisation of the Law on Access to Information”], lecture at the Canada School of Public Service, 24 September 2012, http://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/fra/med-roo-sal-med_speeches-discours_2012_8.aspx.

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/e6d58b52-en

© OECD 2019

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.