copy the linklink copied!3. The work/family balance in Korean workplaces

This chapter discusses how the highly segmented labour market shapes work-life balance issues in Korea. It shows that women are over-represented in non-regular and low-wage employment, which provides limited coverage to maternity and parental leave benefits. Long working hours also challenge work/life balance issues, especially in conjunction with the often considerable commutes and the prevailing “socialising after work culture”.

The chapter discusses recent measures to retain women in the labour market, help them return to work after a long interruption, and/or reduce excessive working hours. Policies which could help achieve a better balance between work and family life include: i) increasing the use of maternity and parental leave; ii) expanding opportunities to work part-time; iii) promoting greater working time flexibility; iv) tackling discrimination effectively; and v) strengthening affirmative measures to promote gender equality in employment.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

copy the linklink copied!3.1. Introduction and main findings

The dynamism of the Korean labour market in terms of job creation and the increase in female educational attainment has contributed to a rise in the female employment rate from 50% in 2000 to almost 57% in 2017. However, Korea’s labour market is highly segmented, between workers in regular employment with seniority-based remuneration, social protection coverage, job stability and decent job-quality, and non-regular workers with low pay, limited access to social protection, fixed term employment contracts and poor job quality. These latter jobs are often in the large number of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Korea, where overall labour productivity is low.

Women are over-represented in low-wage employment: 37% of women working full-time are in low paid employment compared to 15% of men; and 30% of mothers and 12% of fathers are in non-regular employment. Non-regular jobs do not always provide basic social security coverage, exacerbating the vulnerability of those in non-regular employment, and they are not all eligible for maternity or parental leave benefits that are available to those in regular employment.

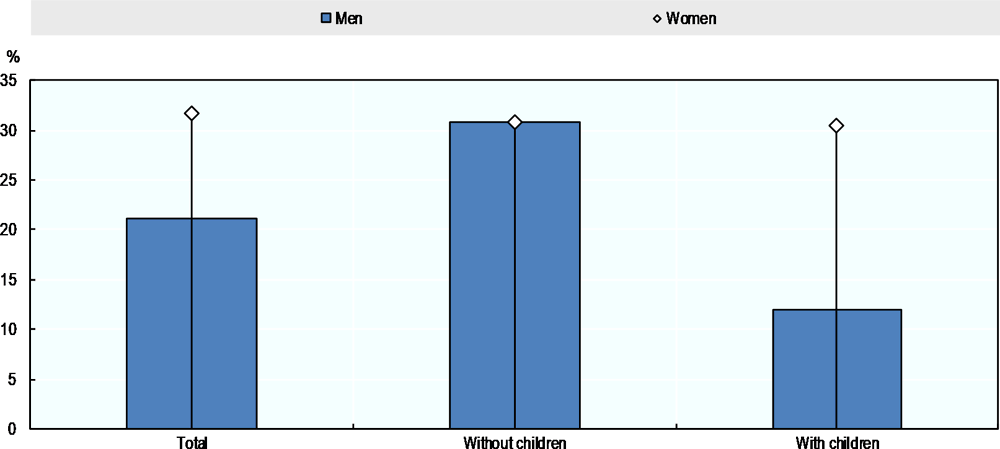

Workers, both men and women, have long working hours in Korea. On average, full-time workers work 46.8 hours per week when the OECD average is 42 hours. The percentage of men and especially women working long hours is also much higher than the OECD average: 21% of women work 50 hours or more per week in Korea compared with 8% on average across the OECD, while part-time work (18% of female employees) is also much less frequent than in many other OECD countries (24%). To curb the long work hours culture and prevent overwork, recent legislation stipulates a reduction of the maximum working hours from 68 hours to 52 hours per week. At present, the law applies only to large companies, but its coverage is scheduled to be extended to smaller companies in the near future. This law signals to both companies and workers that a better equilibrium can be found to both achieve greater labour productivity and allow employees to find a better balance between work and family life.

Korean workers spend more time commuting to and from work than workers in most other OECD countries. In addition, many (often regular) workers spend time socialising after work with their colleagues a few evenings per week. The “long hours culture” and the “after work social culture” reflect traditional social norms and contribute to the strong division of paid and unpaid work between men and women.

To keep women in employment and reduce the frequency and duration of career breaks, Korea has introduced relatively generous maternity and parental leave rights compared to other OECD countries. In particular, each parent who has been in their job for at least six months is theoretically entitled to one year of paid parental leave even though payment rates are generally low, except for the first three months. However, important categories of workers are excluded, including self-employed workers who are not covered by the legislation on parental leave, and employees who work less than 60 hours a month who cannot get parental leave benefits paid from the employment insurance because the Employment Insurance Act does not apply to them. A significant share of women prefer not to take the leave in order to avoid penalising their co-workers, as companies often do not fill temporary vacancies, and the corporate culture is not supportive of fathers going on leave (OECD, 2018[1]). For all these reasons, the use of parental leave remains relatively low, even though it has grown significantly in recent years. Korea has also set up programmes to reintegrate women who have interrupted their professional activity for several years through a coordinated offer of training and job search services adapted to their skills and family constraints.

In the Korean labour market environment, it is currently difficult to reconcile work and family commitments. Workplace measures that could improve the work/family balance include:

-

Increasing the use of maternity and parental leave. Several measures can help to increase the use of leave, including: i) increasing the comparatively low level of pay; ii) introducing the possibility of opting for shorter but better paid leave; and iii) extending leave entitlements to groups of workers not covered (such as employees working less than 60 hours per month, domestic workers and self-employed). For leave policies to become more effective in Korea, it is also important to develop a more supportive workplace environment and to better enforce the law (OECD, 2016[2]). A government initiative linking data on health and employment insurance and investigating firms suspected of not allowing workers to take maternity leave is well worth pursuing and should be strengthened where needed (OECD, 2018[1]).

-

Expanding opportunities to work part-time in order to encourage mothers to stay in the labour market. Mothers currently tend to leave employment around childbirth, especially when they hold non-regular jobs. Several countries allow employees with children to reduce their working hours over a specified period by maintaining remuneration proportional to working hours and social security rights. For example, in Sweden parents can reduce their working hours by 25% until their child becomes eight years of age; in Germany, a parent has the right to reduce their working hours between 15 and 30 hours for three years. A key point is also that workers can return to full-time work and maintain their career prospects after a period of reduced working time.

-

Promoting greater working time flexibility. About 8.4% of wage workers use flexible working arrangements, but this rate is rather low compared to EU countries, where 3 out of 4 employees enjoy some form of working time flexibility, including flexible start and finishing times or teleworking opportunities. Some countries limit flexible working time options to employees with care responsibilities, but other countries such as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom provide such opportunities to all employees in order to avoid discrimination against particular groups of workers. Policy should encourage companies to develop opportunities to work with flexible starting and finishing times, spread working hours across weeks or months, or use home or teleworking options to help workers balance work and family. The government should also encourage companies to put this issue on the agenda of enterprise and sectoral bargaining, and facilitate the sharing of information on best practices in working time flexibility and the implementation of associated changes in work organisation.

-

Tackling discrimination effectively. The guarantee that an employee will not be penalised with regard to remuneration and career opportunities if he or she takes parental leave, works part-time or uses working time flexibility is crucial for these practices to become widely used and accepted. To help reduce the potential for discrimination, policy could increase sanctions on employers to improve the financial incentives to comply with non-discriminatory workplace practices; strengthen the labour inspectorate to more effectively enforce anti-discrimination legislation; and make it easier for workers to file complaints on discrimination with labour courts.

-

Strengthening affirmative measures to promote gender equality in employment. Korea has put in place affirmative action plans to monitor companies' progress in achieving gender equality in employment. Following the example of some countries, wage transparency measures could be introduced to help address gender pay inequalities.

copy the linklink copied!3.2. A dual labour market

3.2.1. A dynamic labour market, but with long working hours and low labour productivity

Korea’s labour market has undergone profound changes over the past decades. Starting from a relative abundance of low-skilled, rural self-employment, Korea’s population now engages in much more high-skilled work in the service sector. The share of Korean workers employed in agriculture, forestry and fishery declined from 17% in 1990 to 5% in 2018, while the employment share in industry fell by 10 percentage points to 25%. Over the same period, the employment share in the service sector increased from 46.7% to 70%.

The number of jobs created to absorb labour force growth has been significant: in 1990, about 18 million people were in employment, which grew to 28.6 million in 2018. In 1990, just over 7.3 million women were in employment, compared to 11.4 million in 2018. Over the same period, the female employment rate increased significantly, but at 57%, it is still almost 20 percentage points lower than for men (Figure 3.1).

Another strength of the Korean labour market is the very low unemployment rate – 4% in the first quarter of 2019, and a very low long-term unemployment rate (unemployed for 12 months and over), which stands at only 0.4% of total unemployment compared with an OECD average of 33.8% in 2015. This low level of unemployment reflects the job creative power of the Korean labour market, limitations in coverage of Employment Insurance (EI) and the low payment rates of unemployment benefits. Many Koreans (especially married women) also move out of the labour force within their first year of unemployment, which contributes to the labour force inactivity rate in Korea being somewhat higher than the OECD average – 30.7% vis-a-vis 27.6% in 2018.

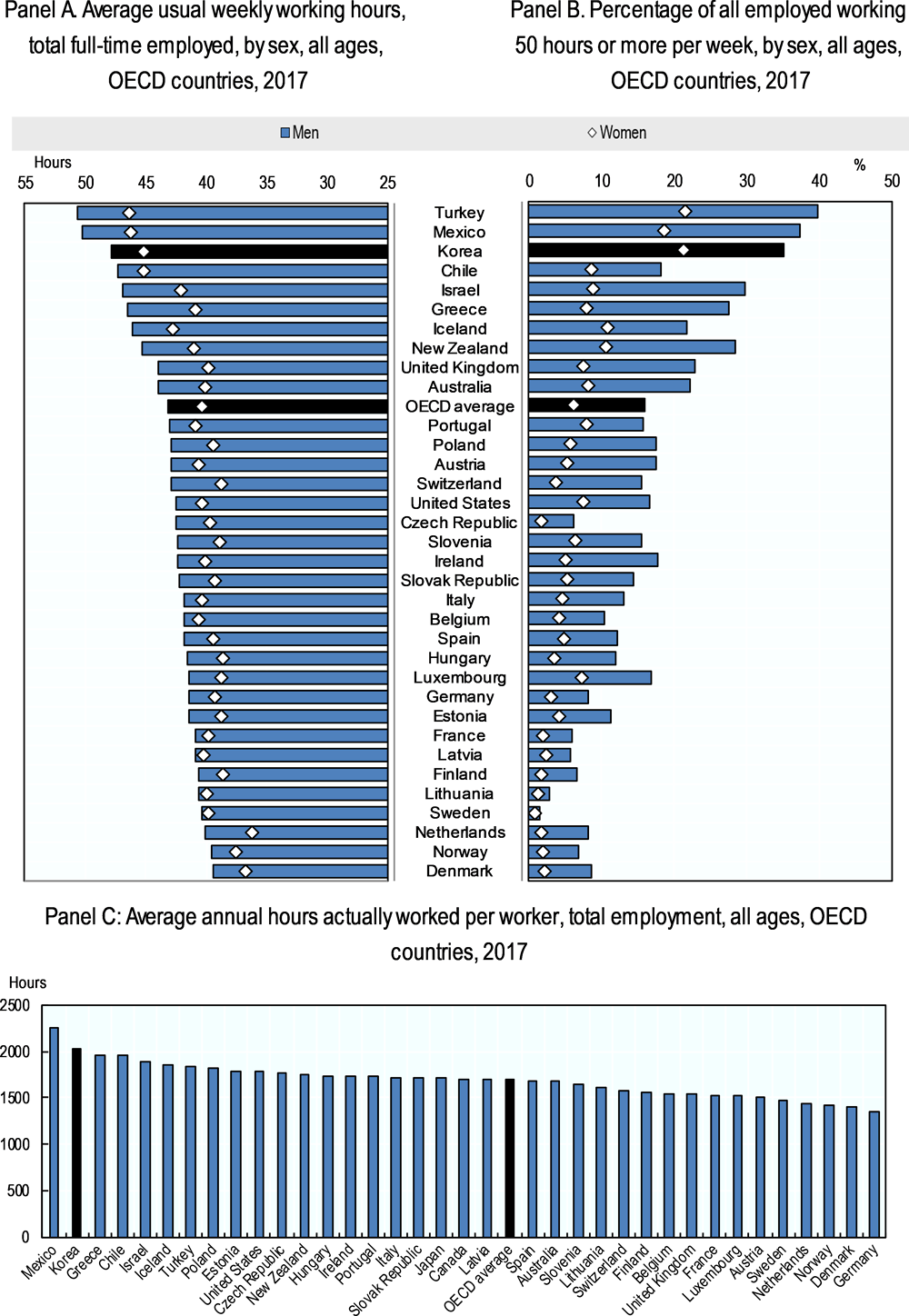

The long working hours culture is a salient feature of the Korean labour market. Koreans spend more time in paid work than workers in most OECD countries. At 47.8 hours per week for men and 45.2 hours per week for women, Korea has some of the longest average weekly working hours in the OECD (Figure 3.2, Panel A). The OECD average full-time working week is 43.1 hours for men and 40.3 hours for women. Only Mexico (50.2 hours per week for men, and 46.2 for women) and Turkey (50.7 hours per week for men, and 46.3 for women) have longer average full-time hours.

Korea also ranks above the OECD average in the share of workers spending over 50 hours per week on the job. About 35% of male Korean workers work 50 hours or more per week, as do 21% of female Korean workers (Figure 3.2, Panel B). These are far higher than the respective OECD averages of 16% and 6%. According to 2013 statistics on weekly working hours of wage earners in 16 cities and provinces, out of the 17.4 million workers, some 4.7 million or 27%, were found to be unable to leave work before 8p.m. and 2.6 million workers or 15%, remained in the office until 9p.m. (Hankyoreh, 2014[3]). Just over 2 million workers reporting staying in the office until 10p.m., and 610 000 workers reported regularly work until midnight or beyond.

Korea also has the highest average annual number of hours worked per worker of any OECD country other than Mexico, even though the number of hours has fallen from just over 2 200 in 2008 (OECD Employment Database) to just over 2000 (Figure 3.2, Panel C). On the other hand, labour productivity in Korea is about 48% lower than in the United States and well below the OECD average (Figure 3.3).

3.2.2. Labour market dualities

Korea’s labour market displays very pronounced dualities that result in very different outcomes for workers in terms of job quality, earnings and social protection. One of the main manifestations of labour market dualism is the large proportion of non-salaried workers – including own-account workers, employers and contributing family workers – that are related to the proliferation of micro-enterprises. In 2018, 40.9% of employees were working in micro-enterprises (i.e. those with fewer than 10 employees) and only 14.6% of workers in Korea were employed by large firms with 300 or more employees (OECD, 2018[4]). The share of non-salaried workers in Korea’s total employment fell from 61.0% in 1970 to 25% by 2018. Nevertheless, this is well above the OECD average of 15.5% in 2018. Furthermore, just over 30% of Korean workers in 2016 were informal workers without coverage by minimum wage regulations, labour standards and social insurance regulations (OECD, 2019[5]).

The prevalence of non-regular employment is another indication of the high degree of labour market segmentation in Korea. Non-regular employment accounts for a little over one-third of all salaried workers in Korea, and is largely concentrated in micro-enterprises: in 2016, 48.7% of non-regular workers are employed in micro-enterprises with fewer than 10 employees and 72.1% of them in small firms with fewer than 30 employees (OECD, 2018[4]). One reason is that in order to keep labour costs down and enhance business flexibility, larger firms often prefer subcontracting out work to SMEs rather than hiring non-regular workers directly. The fact that nearly half of all non-regular workers in Korea are concentrated in micro-enterprises makes it more difficult for these workers to find a pathway into more secure and better-paid jobs in larger firms.

The high segmentation of the labour market also means that a high proportion of workers hold a job for a short period of time, possibly before moving on to another job. At just 6.2 years in 2018, average job tenure among Korean employees (15- to 64-year-olds) is the shortest among OECD countries with comparable data (OECD Employment Database). The average across the OECD is 9.4 years. In Korea, more than one-quarter of male employees and close to one-third of female employees separate from their jobs within one year – both well above the OECD average (Figure 3.4). Korean women are much more likely than Korean men to have been with their current employer for less than one year. As the unemployment rate is low, the probability of finding a job at the end of a contract is relatively high and so is turnover in the labour market. However, the high turnover contributes to economic insecurity, which is not conducive to family planning (Chapter 5).

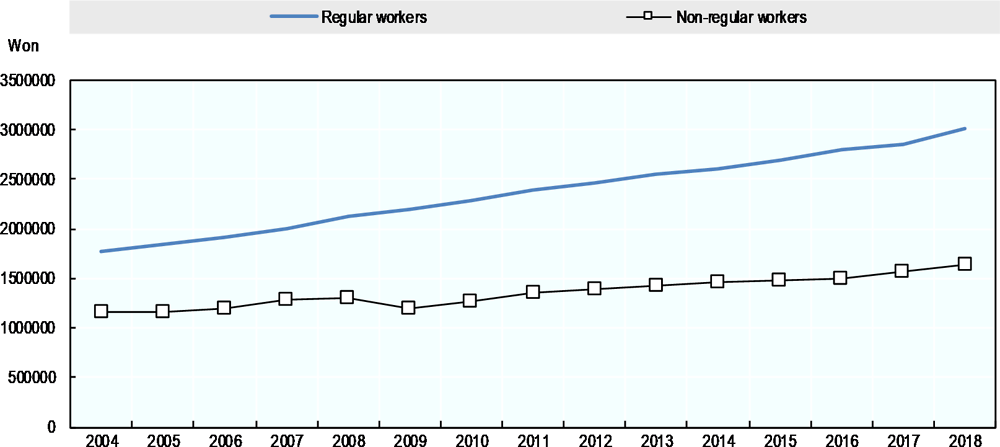

Labour market duality is also a major cause of income inequality in Korea. In 2018, non-regular workers were paid 45% less per month than regular salaried workers (Figure 3.5). Regular employees see their remuneration increase with seniority and tenure and have career opportunities while this is not the case for non-regular workers, so that wage gaps widen over the working-life cycle until age 60. Workers with a secondary or lower level of educational attainment are over-represented among non-regular workers, (although almost one-third of the non-regular workers had completed tertiary education) and part-time workers (almost 40% of all non-regular employees) generally do not have access to regular employment conditions. The wage gap between regular and non-regular salaried workers has gradually increased since the early 2000s and mobility between the two categories of workers is very low. International comparisons show that temporary workers in Korea appear to be more at risk of becoming trapped in temporary employment or becoming unemployed than their counterparts in other OECD countries (OECD, 2013[6]).

3.2.3. A limited role for collective bargaining

Trade union members across OECD countries predominantly have a permanent status in employment – with only 11% of them working on a non-permanent basis (OECD, 2017[7]). The role of trade unions is limited in Korea, as collective bargaining takes place at company level and trade-union membership is very low among SMEs: about 0.1% of employees in companies with less than 30 employees and 2.7% in companies with less than 100 employees are union members (OECD, 2018[4]).

Furthermore, the Labour Standards Act is one of the most important laws on the working conditions of employees in Korea, but it applies only partially to micro-firms with less than five employees. Most of the regulations on dismissal and working hours do not apply to the micro-firms: employers are allowed to dismiss employees without further ado and there are no daily or weekly limits on working hours. Also, employers in micro-firms do not have to pay a higher wage rate for overtime. The near non-existence of trade unions and the limited application of the Labour Standards Act contribute to persistently low wages and the precariousness of employment in small firms in Korea. By contrast, the unionisation rate is high in large companies (about 63% of employees in companies with more than 300 employees are unionised) and these companies are subject to the 2018 Labour Standard Act, which aims to limit the number of weekly working hours (see Section 3.5 below).

copy the linklink copied!3.3. Between a rock and a hard place

3.3.1. Career interruptions for family reasons are frequent in Korea

Although their employment rate is increasing, women are among the population groups that are most affected by the deep segmentation of the Korean labour market. It is difficult to obtain a regular employment contract in occupations and industries that facility career progression and fulfilment of individual labour market aspirations. However, such employment leaves little time to devote to family life. Women in regular employment have to think twice before starting a family, and often postpone parenthood, sometimes indefinitely. At the same time, the employment conditions and career prospects in non-regular employment are not particularly attractive, especially for highly educated workers, so that if household income allows one parent, usually the mother, may choose to stay home and provide personal care for the family rather than go back to work.

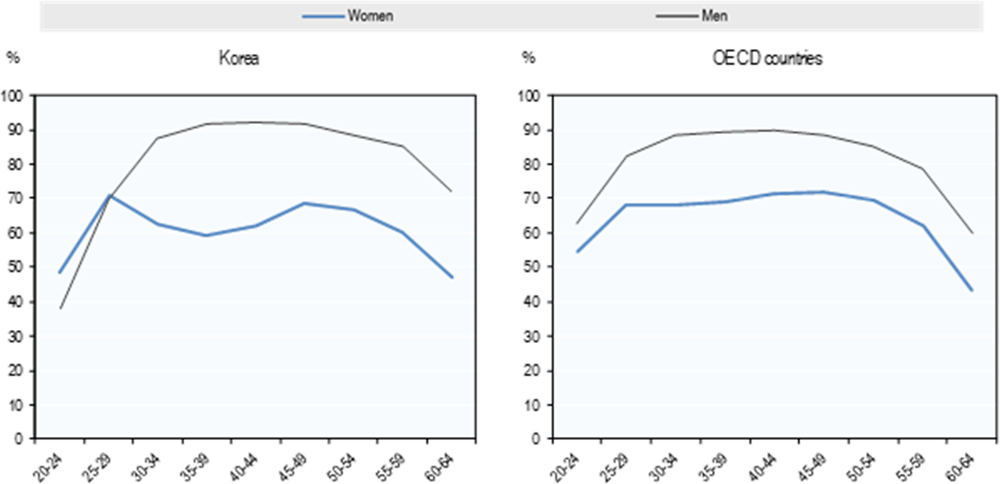

In such an environment, the birth of a child is likely to encourage women to stop working or to steer them into jobs with low pay and poor career opportunities (Blossfeld and Hakim, 1997[8]) (Esping-Andersen, 1999[9]). In Korea, over 50% of married women aged 15 to 49 with at least one child quit their job around first childbirth, while around 34% continued to work in the same job and 15% moved to another job (KIHASA, 2018[10]). Female employment rates dip around the childbearing years, and Korea is one of the few OECD countries where an M-shaped age profile of female employment rates persists (Figure 3.6).

In addition, new mothers withdraw from the labour force for a long time. According to KLIPS data, women who interrupted labour force participation after the birth of their first child, stopped working for an average of three years over the period 2006 to 2015. However, the effect is not as pronounced as in the past: new mothers left the labour force for on average almost 6 years over the 1996-2005 period.

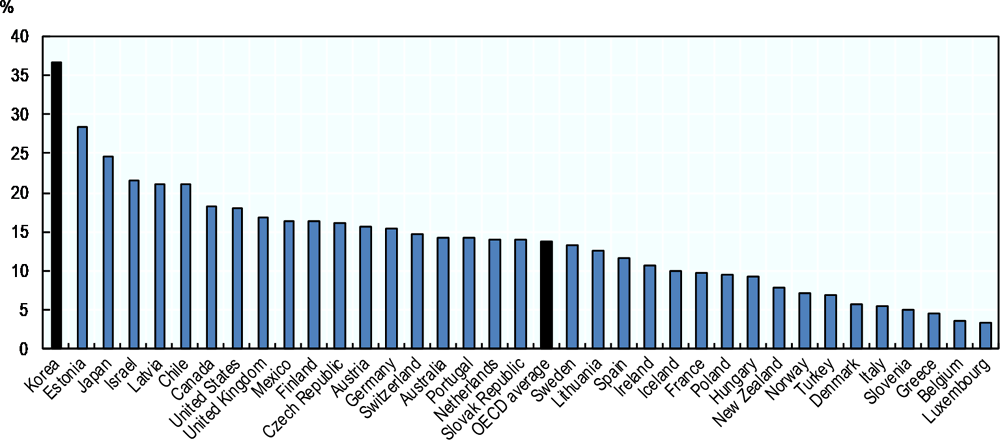

3.3.2. A substantial number of women work in low-paid jobs

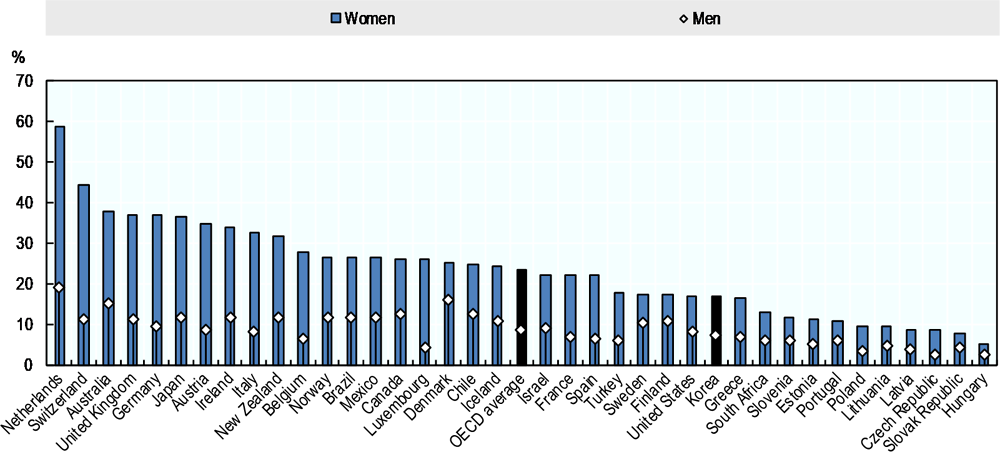

Career differences between men and women develop early in working life and lead to a gender wage gap that is higher in Korea than in other OECD countries (Figure 3.7). Few women are promoted to management positions in Korea: women represented about 12.5% of managers in 2017, compared to 32.5% on average in the OECD. Women are also over-represented in low-paid employment: more than 37% of women who work full time are in low-paid employment, compared to only 15% of men and 20% of women on average across the OECD (Figure 3.8).

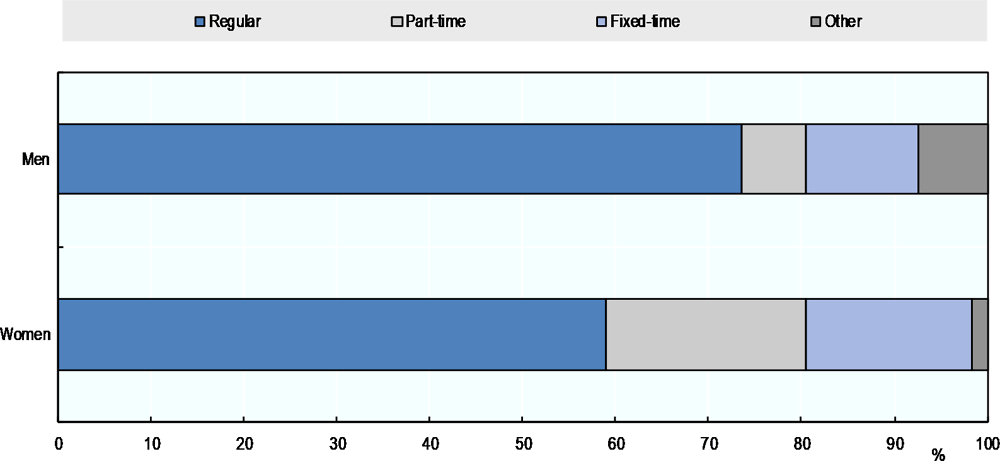

Women are substantially more likely than men to be in non-regular employment, whether on a temporary or part-time basis (Figure 3.9). Men are unlikely to withdraw from the labour force for family reasons. However, women who have taken a few years out of the labour force to care for young children, find the labour market unattractive to come back to. In general, regular employment opportunities are hard to find for the “mother returners” whom often only have lowly paid, non-regular job opportunities available. As a result, mothers are three times more likely to be in non-regular employment than fathers (Figure 3.10). In fact, fathers are three times more likely than childless men to be in regular employment, which shows that parenthood does not damage men’s chances of accessing regular employment, while it obviously does for mothers.

Part-time work is on the rise, but its incidence among women (and men) is significantly lower than on average across OECD countries. 18% of employed women in Korea worked part-time (less than 30 hours per week) in 2018, compared to an average of just over 25% in the OECD. Part-time jobs are often low-paid and give limited to social protection. For example, until recently a person working for less than 60 hours per month or less than 15 hours per week was not entitled to unemployment benefits. Since July 2018, however, they can claim unemployment benefits if they have an employment contract of three months or more. The right to parental leave is also not formally guaranteed to those working less than 60 hours per month (see below).

3.3.3. Partnering in separate spheres?

In addition to the long working hours culture, there is a corporate workplace culture in Korea that involves socialising with colleagues after office hours. This form of socialising is regarded as important by employees as they wish to show their loyalty to the company; it also provides an opportunity for employees to develop their network and get workplace information that they would not otherwise have. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the weekly number of social gatherings after work is declining, but they remain frequent and important, especially for young people at the beginning of their careers.

In addition, Korean workers spend a lot of time on their daily commute to and from work in comparison to workers across the OECD (Figure 3.12). Commuting times are particularly long for men who spend an average of 72 minutes per day travelling to and from work or study, compared to 41 minutes for women. Furthermore, in 2018, about 25% of employees live in one province and work in another, which means they may not always be able to return home at night after a very long day at work (Statistics Korea, 2018[11]).

The combination of long working hours, long daily commutes and the socialising after work culture means that fathers, in particular, have little time to spend with their families on a daily basis. This contributes to a strong division of paid and unpaid work between the partners: on average, Korean women spend close to three hours more on unpaid housework each day than men do (Figure 3.13).

copy the linklink copied!3.4. Keeping young fathers and mothers in the labour force

The Korean labour market has to get better at keeping men and women in employment following childbirth and helping them pursue their careers. Policy has moved to enable working parents to balance work and family life more effectively. In fact, employment-protected maternity- and parental leave policies provide income support during the period after childbirth, while workplace measures limiting working hours or teleworking can also help make workplace cultures more compatible with family life (Chapter 4 discusses childcare and out-of-school hours care supports).

3.4.1. Paid parental leave

Over the past few decades, paid maternity, paternity, and parental leaves have become major features of national family support packages in most OECD countries. Designed to be used around childbirth and when children are very young, employment-protected paid leave can help parents achieve a range of work and family goals. As well as protecting the health of working mothers and their new-born children, paid leave helps keep mothers in paid work and provides parents with the opportunity to spend time at home with children when they are young (Adema, Clarke and Frey, 2015[12]; Rossin-Slater, 2017[13]) (Thévenon, 2018[14]). In more recent years, paid leave policies have increasingly been used as a tool to promote gender equality and encourage the redistribution of unpaid work within the household. A growing number of OECD countries (including Korea) have introduced ‘fathers-only’ leaves, such as paid paternity leave and individual entitlements of fathers to paid parental leave, with the aim of encouraging men to spend more time with their children.

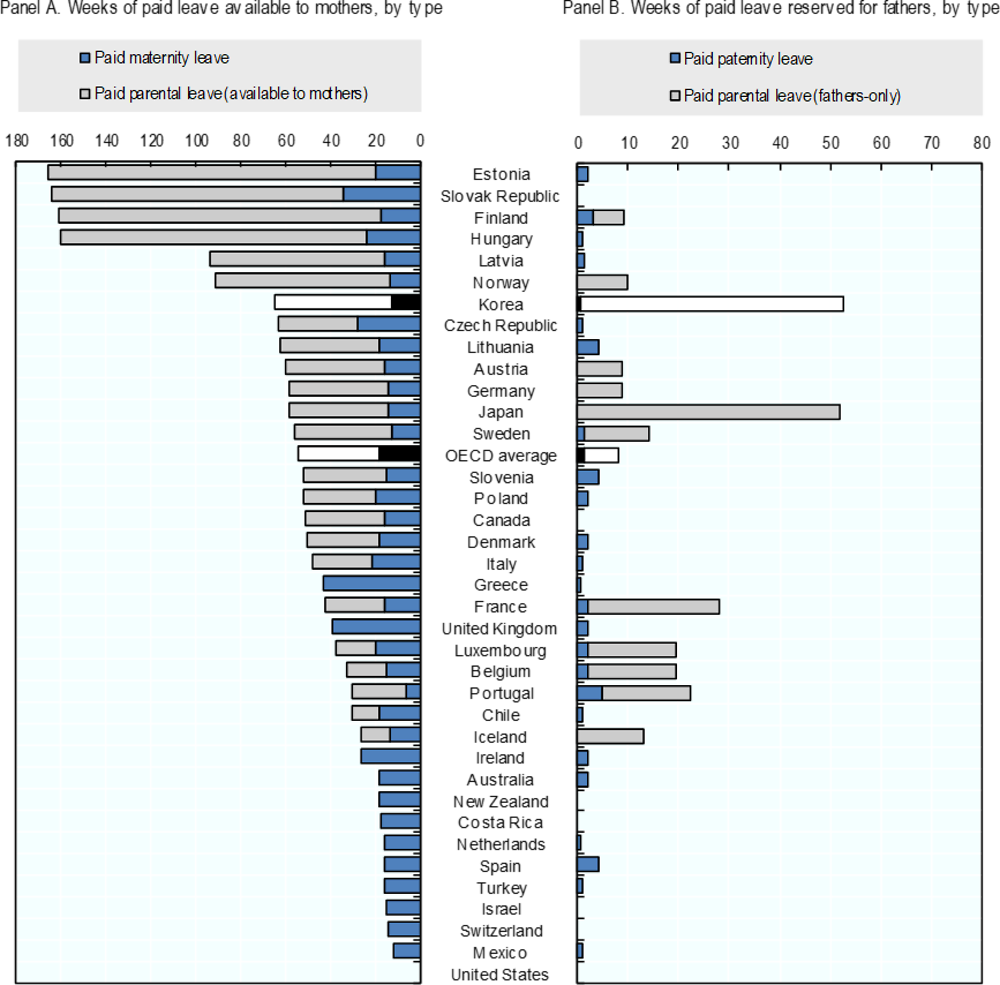

Most OECD countries have long provided paid leaves for use directly around childbirth, especially to mothers. Today, all OECD countries except the United States have national schemes that offer mothers a statutory right to paid maternity leave right around the birth (Figure 3.14, Panel A), usually for somewhere between 15 to 20 weeks and often for at least the 14 weeks as stipulated by the ILO Convention on Maternity Protection (International Labour Organization, 2000[15]). An increasing number of countries also offer paid paternity leave – short but usually well-paid periods of leave for fathers to be used within the first few months of a baby's arrival. These paternity leaves often lasts for around one or two weeks, although in some OECD countries (e.g. Greece and Italy) they last for no more than just a few days (Figure 3.14, Panel B).

The Korean system provides both paid maternity and paid paternity leave to eligible working parents around childbirth. Employed mothers in Korea have held a statutory entitlement to paid maternity leave since 1953. Today, new mothers are entitled to 90 days of paid maternity leave – just below the OECD average of 18 weeks (Figure 3.14, Panel A). For the first 60 days, mothers on maternity leave continue to receive full pay from their employer. The remaining 30 days are paid through an allowance provided by the Employment Insurance Fund providing 100% of earnings up to a ceiling of KRW 1 800 000 (USD 1 636). This is, however, only available to mothers who have been insured with the Employment Insurance Fund for at least 180 days including maternity leave. In addition, to reduce the financial burden on small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), the Employment Insurance Fund pays for the first 60 days of maternity leave of employees in these companies up to a ceiling. Moreover, since July 2019, maternity benefits of KRW 500 000 per month have been paid for three months to pregnant women who are unable to receive maternity leave benefits from the employment insurance.

All female workers who are within the first 12 weeks or beyond the 36th week of their pregnancies can also reduce their working hours by two hours a day without reduction in pay. This rule on shorter work hours for pregnant workers previously applied only to companies with more than 300 employees, but was extended to all businesses in March 2016.

Paternity leave was first introduced in 2008 as a three-day unpaid leave, with payment added later in 2012. Currently, male employees in Korea are entitled to three days paid paternity leave with full continued payment by the employer. There is also the option of a further two days, but the employer is under no obligation to provide payment on these days. The leave must be taken within 30 days of the birth.

Paid parental leave can be taken for a year, but overall payment rates are relatively low

In addition to paid maternity and paternity leave, many OECD countries also provide parents with access to additional paid parental and/or prolonged home-care leaves. The length of paid parental and home-care leave varies considerably across OECD countries (Figure 3.14). In most countries, parents can access between 6 and 18 months of paid parental and/or home-care leave. However, in some countries – like Estonia, Finland, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and also France, for families with two or more children – parents can take paid leave until their child’s second or third birthday.

Entitlements to paid parental leave in OECD countries are often shareable family entitlements, with each family having the right to a certain number of weeks of parental leave payments to divide as they see fit. While in theory this provides both parents with the opportunity to take paid parental leave, in practice mother rather than fathers take such leave (Moss, 2015[16]). Fathers often earn more than their partners (OECD, 2017[17]), so unless leave benefits (almost) fully replace previous earnings, it makes economic sense for the mother to take the bulk of the leave. Societal attitudes towards the roles of mothers and fathers in caring for young children and concerns around potential career implications, also contribute to a general reluctance among many fathers towards taking long periods of leave (Rudman and Mescher, 2013[18]; Duvander, 2014[19]).

To stimulate take-up among men, several OECD countries now provide fathers (and mothers) with their own individual paid parental leave entitlements on a “use it or lose it” basis (Figure 3.14). These parent-specific entitlements can take different forms. Most common are “mummy and daddy quotas” – specific portions of an overall parental leave period that are reserved exclusively for each parent. Other options include “bonus periods” – where a couple may qualify for extra weeks/months of paid leave if both parents use a certain amount of shareable leave, as e.g. in Germany – or the provision of paid parental leave as an individual, non-transferable entitlement for each parent.

Korea operates a fully-individualised paid parental leave scheme that provides both mothers and fathers with their own entitlement for up to one year of leave. First introduced in 1988 as an unpaid leave just for mothers with a child under age 1, parental leave arrangements were extended several times during the 1990s and 2000s. Key developments came in 2001 when flat-rate payments were introduced, and in 2008 and 2011 when, respectively, reforms adopted as part of the first Basic Plan on Low Fertility and Ageing Society (Chapter 1) transformed the benefit into an individual entitlement for both parents with an earnings-related payment rate. In 2019, employed mothers and fathers insured by the Employment Insurance Fund can take up to 12 months paid parental leave each until the child’s eighth birthday (or until they enter the second year of primary education). Leave can be split into two blocks and can be taken on a part-time basis: employees can reduce their working hours, but they have to work a minimum of 15 hours and a maximum of 30 hours per week. The parental leave benefit is paid in proportion to the number of working hours; parents cannot take leave simultaneously and both receive payment. The average payment rate when leave is taken for one year is relatively low in comparison with some other OECD countries (OECD Family Database), but the recently introduced “Daddy Months” provides financial incentives to the second parent (usually the father) to make better use of parental leave benefits (see Box 3.1).

In comparison to many OECD countries, the overall package of statutory paid leave supports provided in Korea is extensive. Taking the paid maternity leave and the paid parental leave entitlements together, mothers in Korea can take up to 65 weeks of paid leave in total, slightly longer than the OECD average of 55 weeks (Figure 3.14, Panel A). Fathers, meanwhile, can take a total of almost 53 weeks of paid paternity and parental leave. This is longer than in all OECD countries other than Japan, and far longer than the OECD average of 8 weeks (Figure 3.14, Panel B).

Rights to leave employment are not limited to parents with young children. In Korea, as in other OECD countries, statutory leave entitlements also exist for adults with dependents who are ill (Table 3.1). Employees with a sick child or close family member can access leave to care for dependents, the duration of which depends on the severity of the illness. In Korea, employees can take up to 90 days’ unpaid leave per year to take care of a family member on account of illness, accident, old age etc. The leave must be taken in blocks of at least 30 days and is unpaid.

Compared to other countries, the period for which employees with a sick child or relative can take leave is long, but many other countries provide shorter but paid leaves to care for sick children. The most generous scheme is in Sweden where parents of a child under 12 years of age can benefit from up to 120 days of sick child leave, paid up to 77% of earnings up to maximum threshold at SEK 341 184 in 2018 (USD 36 800) per year (Duvander and Haas, 2019[20]).

Eligible Korean parents have access to a year of paid parental leave, but payment rates are lower than in some other OECD countries. In 2019, the payment rate is 80% of ordinary earnings for the first three months of full-time parental leave with a minimum of KRW 700 000 (USD 636) and a maximum of KRW 1 500 000 (USD 1 364) a month (equivalent to roughly 36% of average full-time earnings). For the remaining nine months, the payment rate is 50% of ordinary earnings, with the same minimum but a maximum of KRW 1 200 000 (USD 1 091) a month (about 29% of average full-time earnings). For a worker on (2019) average full-time earnings (Chapter 2), after accounting for the payment ceilings, the average payment for the duration of leave works out at around 31% of previous earnings. In comparison, payment rates in Slovenia approximate 90% of previous earnings up to a ceiling set at twice the average wage. In Japan, payment rates are 67% of past earnings up to a moderate ceiling for six months, and 50% of past earnings up to a slightly lower ceiling for the remainder (Figure 3.15, Panel A).

In order to stimulate a father’s use of parental leave, the Korean government introduced the so-called “Daddy Months” in 2014, which was extended to three months in 2016. In case both parents take leave, the second parent to claim the benefit (usually the father) is entitled to a temporarily increased payment rate: as of 2019, 100% of ordinary earnings up to a ceiling of KRW 2 500 000 (USD 2 273) per month for the first three months (equivalent to roughly 60% of average full-time earnings). The average payment across the whole year works out at around 37% for a worker on (2019) average full-time earnings (Figure 3.15, Panel B), but the system provides ample financial incentives to fathers to take leave for up to three months.

The number of parents using paid leave in Korea is low but increasing

Korea’s paid leave programmes are not well used in general. Take up of maternity leave is highest, but for children born in 2017, only about 23% of mothers received maternity leave benefits from the National Employment Insurance (EI) Scheme (Statistics Korea, 2018[21]). Mothers on maternity leave in the civil service and the teaching profession (covered by separate institutional arrangements) accounted for another 11% of the children born in 2017. In 2018, only around 100 000 parents claimed the parental leave benefit – about 30 claimants per 100 live births (Statistics Korea, 2018[21]). Mothers are much more likely to claim the benefit than fathers, and about 82 000 women took parental leave compared to around 18 000 men in 2018 (Statistics Korea, 2018[21]). This is not high in international comparison. For example, in Germany in 2016, there were roughly 94 mothers and 35 fathers claiming parental leave benefits for every 100 live births. In Sweden, parents generally use their parental leave entitlements, and fathers take about 30% of the available leave days (OECD, 2018[22]).

There are different reasons why paid child-related leaves in Korea are not as widely used as in some other OECD countries. One reason is that many mothers still quit work upon getting married or childbirth. In April 2018, just over 38% of married women aged 15-54 reported they were not working. Half of them reported they were taking a break from their careers because of marriage (7.1 percentage points), childbirth (4.9 percentage points), or because they were caring for or educating a child or family member (6.9 percentage points), while another 17.5 percentage points cited other reasons (Statistics Korea, 2018[23]). A significant share of women prefer not to take the leave in order to avoid penalising their co-workers, as companies often do not fill temporary vacancies (OECD, 2018[1]).

Government officials and teachers (schools and universities) have their own occupational schemes that provide parental leave benefits with payment rates that are the same as under the EI-scheme, but that can also cater for unpaid leave for up to two years. Take up of benefits among these workers is high, and in 2017, the numbers of parents (mothers and fathers) claiming parental leave benefits amounted to over 48 000, which is equivalent to about 53% of parental leave users under the EI-scheme (Korea Ministry of Personal Management, 2018[24]) (Korea Ministry of Interior and Safety, 2018[25]).

However, until reform was introduced on 1 July 2019, except for officials and teachers, the EI-scheme did not cover: employees working for less than 60 hours per month, domestic workers, the self-employed and workers in SMEs in the agriculture, construction, forestry, fishery, and hunting sectors with 4 or less employees. As of April 2018, around one-third of employed women (not including government officials and teachers) were not covered by the national employment insurance fund (Statistics Korea, 2018[23]). However, with the reform on 1 July 2019, the government extended coverage to most of these workers and provide income support for three months of maternity leave with (general tax-financed) income support up to KRW 1 500 000 (USD 1364) for three months.

For fathers, much of the challenge is cultural. Like elsewhere in the OECD, fathers in Korea often are reluctant to take leave for a prolonged period, as they are concerned this may have a negative effect on their career or their relationships with colleagues (Won and Pascall, 2004[26]; Moon and Shin, 2018[27]). The long working hours culture and emphasis placed on commitment to the firm among regular employees exacerbate this issue in Korea. Moon and Shin (2018[27]) found that the long working hours culture acts as a barrier to men’s unpaid work regardless of their attitudes or characteristics, and that Korea’s culture of “work devotion” make it almost impossible for even the most well-intentioned men to contribute much to domestic chores.

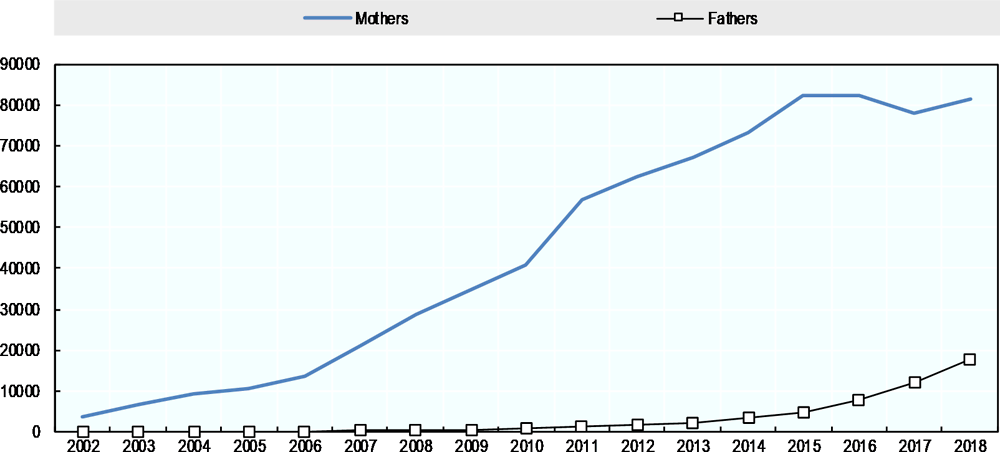

There is some cause for optimism, however. The number of parents taking leave in Korea has been growing in recent years, among both mothers and fathers. In 2002, the total number of parents (mothers and fathers) claiming parental leave benefits came to less than 4 000, but this had increased to just under 100 000 by 2018 (Figure 3.16). In absolute terms, much of the growth in parental leave users since 2002, concerned mothers rather than fathers. However, over the past 5 years, the use of parental leave by fathers has increased significantly so that they make up 18% of the parental leave takers under the EI-scheme (Figure 3.16).

The low rate of use of maternity and parental leave is a policy concern. Over the years, several measures have been introduced to increase usage. For example, in 2011 the flat-rate payment was changed into an earnings-related payment rate, which contributed to increased take up among mothers, especially among those in higher earnings groups (Yoon and Hong, 2014[28]). In September 2017, payment rates for the first three months of parental leave increased from 40 to 80% of ordinary earnings, while minimum and upper payment limits were also raised.

Furthermore, until recent reform, employees had to work for an employer for the preceding 12 months to be eligible for parental leave, which meant that many workers (especially non-regular workers) did not qualify. Reform in May 2018 reduced the qualifying period to 6 months, which is likely to increase take-up. However, since about 20% of employees have job tenure of less than 6 months in Korea, a significant proportion of employees can be denied access to parental leave by their employer. One solution could be to further shorten the period of continuous employment required to qualify for leave; for example, in Canada, where qualifying periods vary by province. For example, Ontario requires 13 weeks of service, Newfoundland and Labrador require 20 continuous weeks, while Alberta requires a minimum of 90 days with the same employer.

To increase the use of maternity and parental leave by women and men, Korea can draw on the experience in other countries where the use is higher. Measures that can increase take-up include:

-

Increasing payment rate of income support during leave. It is difficult to pinpoint an optimal paid leave payment rate, but cross-national evidence suggest that the use of leave by fathers, especially, tends to be higher in countries that provide more generous paid leave benefits. Iceland and Sweden, for example, are leaders in men’s use of leave – in both, that share of parental leave days taken by men was close to 30% in 2016 (OECD Family Database, Indicator PF2.2). Both also provide relatively generous paid leave benefits: after accounting for payment ceilings, a father on average full-time earnings in Iceland receives payments worth just under 70% of previous earnings, and in Sweden about 76% of previous earnings (OECD Family Database, Indicator PF2.1.). Countries such as Denmark and Portugal – where average earners receive benefits worth 53% and 100% of previous earnings, respectively – also have much higher male shares of leave users (27% and 45%, respectively) than Korea. In Germany, an average payment rate of 65 % of previous earnings, together with a two-month bonus when both parents take leave, has contributed to an increase in fathers’ use of leave to 35 fathers for every 100 live births in 2016. Therefore, payment rates of around 55-66% up to a certain threshold over a specified period appear to be a reasonable model to follow (Karu and Tremblay, 2017[29]).

-

Options to use leave for shorter periods at higher payment rates. Several OECD countries offer parents a choice between at least two options that take into account their financial constraints and access to alternative childcare solutions (Thévenon, 2018[14]).

-

Extending leave entitlements to groups of workers that are not covered so far, such as employees working less than 60 hours per month, domestic workers, and the self-employed. If (some of) these groups are difficult to cover through EI arrangements, it would be worth exploring options to make flat-rate minimum parental leave benefits available to such workers.

-

For leave policies to become more effective in Korea, it is also important to develop a more supportive workplace environment and better enforcement of the law (OECD, 2016[2]). A government initiative linking data on health and employment insurance and investigating firms suspected of not allowing workers to take maternity leave is well worth pursuing and should be strengthened where needed (OECD, 2018[1]).

3.4.2. Support for the re-integration of mothers returning to work

Many women have interrupted their career to care for children in the recent past, and many continue to do so. Against this backdrop, several programmes were put in place to help women return to the labour market.

In 2009, the Ministry of Employment and Labour and the Ministry of Gender Equality introduced education and employment support services in one-stop-shop centres to help “mother returners”. The saeil centres provide assistance such as job counselling and guidance on training and vocational education opportunities. The number of saeil centres has more than doubled since 2009, and in 2018, there were 158 of such centres across Korea. About 480 000 women received employment support services from saeil centres in 2018, and more than one third of them found their jobs or started their own business in that year (Korean Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2019[30]).

There are also financial incentives for SMEs to hire mother returners: SMEs can benefit from a reduction in their corporate tax liability worth about 15-30% of the labour costs of a mother returner (Act on the restriction of special taxation, 2019[31]).

copy the linklink copied!3.5. Developing family-friendly workplaces

To make workplaces more conducive to parents striking a balance between work and family life, the long working hours culture has to be weakened, flexible workplace practices need to be promoted and discrimination against parents who wish to avail of such measures should be addressed. In 2016, the Ministry of Employment and Labour identified the need to spread a culture of going home on time, to improve the corporate culture and to develop flexible work arrangements as key priorities (MoEL, 2016[32]). Progress in this direction needs to be reinforced.

3.5.1. Preventing overwork

To reduce long hours, Korean policy adopted a working time Act in 2017, which reduced the maximum number of legally permitted weekly working hours from 68 to 52 hours. Some industries are not covered by the law, but the number of exempted industries has dropped from 26 to 5 (which involve about 4.5 million workers). The law is being phased in gradually, and became applicable to firms with more than 300 employees, as well as public service departments and publicly funded agencies, on 1 July 2018. Coverage of the law is planned to be extended to companies with more than 50 employees on 1 July 2020 and companies with more than 5 employees on 1 July 2021 (SMEs with less than 5 employees will not be affected). This policy was fairly well received by workers: 64% believe they can spend more time with their families and 55% saw a potentially beneficial effect on their health. However, more than 80% of workers feared that the reduction in working hours would lead to a reduction in pay, and there is a risk that some workers may take on additional jobs to compensate for lost income rather than spend more time with their families. There is some initial evidence that suggests about 20 000 persons have joined on-line taxi services since the law was enacted (Haas, 2018[33]).

Raising employer awareness of the negative effects of overwork and the benefits of reduced working hours is key to increase the prevalence of family-friendly workplaces. The literature suggests that reducing working hours can contribute to greater hourly productivity and a healthier workforce (Box 3.2). In Korea, long working hours are associated with lower job satisfaction, higher psychological distress and lower performance rates (Zhang and Seo, 2018[34]). Furthermore, a 2017 evaluation of the National Assembly Budget Office estimates that a decrease in weekly work hours by 1% can increase labour productivity by 0.79%, without a short-term effect on the number of people in employment (NABO, 2017[35]).

Some large companies have reduced working hours voluntarily in view of the 52 hour working week initiative, including department and hypermarket stores such as Hyundai, Lotte- an oil company, S-Oil and LG U Plus – a telecommunication company (Choi, Bang and Lee, 2018[36]). Arguably most pro-active in this regard was Shinsegae Group (which operates Shinsegae department stores and E-mart hypermarket chains), which since January 2018, reduced weekly working hours to 35 hours while maintaining wage levels. Additional measures that were introduced to achieve the avowed company policy objective to increase productivity and help achieve workers’ work and family life balance, included intensive working-hour periods (e.g. from 10-11.30 and 14.00-16.00), automatic PC shut-down at 17.30, and naming (and shaming) divisions (and their managers) that engaged in frequent overtime work (Kim, 2018[37]).

After one year, the Shinsegae E-mart company has seen noticeable improvements in its workplace culture to the general satisfaction of employees (Kang and Shin, 2019[38]). Compared to the year before, the proportion of workers who engaged in overtime work decreased from 32% to less than 1%; the use of meeting rooms per team halved per week, while the meeting duration was often limited to 30 minutes; the average number of daily users of the company health club increased from 140 to 200; and the frequency of socialising after work also diminished. After initial adjustment issues, many workers assess the reduced working-hour schedule as positive since it has given them more time for both time with their families and children as well as personal development.

However, not all workplaces found it easy to join the 52 working-hour per week initiative. Some construction projects found it difficult to complete on time as the original planning was based on a 68-hours working week. Elsewhere, manual workers in the food industry experienced a decline in remuneration as hours were cut, but companies found it difficult to hire new employees, as they are generally located in rural areas rather than cities.

Combating overwork requires a cultural shift and a change in “work organization” in companies. An efficient organisation’s overarching goal should involve adjusting workplace culture, so that managers value the prioritisation of tasks, time management, and efficient output over hours in the office. It is important for management to recognise that long hours are not necessary for high-quality work, and beyond a certain point, may run counter to it. Some specific measures that employers can take include:

-

Weigh objective output more heavily than subjective traits when evaluating employees. Subjective traits (e.g., co-cooperativeness) may be unfairly biased by the physical presence of employees, whereas outputs like the number of projects or project quality are arguably more objectively measurable across employees with different hours in the office (Elsbach and Cable, 2012).

-

Keep overtime spells short, as evidence suggests that employees can only work for more than 40 hours per week for a few weeks, before productivity declines.

-

Be aware of the effects of overtime. Reconsider scheduling practices and job design, and introduce health protection programmes for employees in jobs that often involve overtime (Dembe et al., 2005[39]).

The long working hours culture is persistent and widespread in Korea. However, while productivity does increase with hours worked up to a point, recent evidence suggests that productivity decreases with working hours in many economic sectors and falls sharply after around 50 hours a week (Dolton, 2017[40]) (Collewet and Sauermann, 2017[41]) (Pencavel, 2015[42]). After five eight-hour days, productivity plateaus and then declines as workers’ anticipate adding extra hours and produce less in each hour. Their risk of accidents and errors increases, and miscommunication and poor decisions are more likely. Workers’ health suffers, too, which also contributes to diminished productivity.

Why does this happen? Fatigue and stress reduce the ability to function, and employees may produce less per hour if they anticipate having to stay at work longer. In addition to lower worker morale and increased errors, the difficulties in providing materials, tools, equipment, and information at a “faster” rate cause efficiency losses (Thomas and Raynar, 1997[43])

Long hours increase the risk of errors, accidents, and injuries across industries (Pencavel, 2015[42]); (Dembe et al., 2005[39]). In the medical field, for instance, doctors, nurses, and medical interns make more errors in treating patients (Rogers et al., 2004[44]); (Flinn and Armstrong, 2011[45]), and workers are more likely to be involved in motor vehicle accidents (Barger et al., 2005[46]) after working long shifts. Performance on tasks that require focus and concentration worsens as a function of time, a phenomenon known as “vigilance decrement” (Ariga and Lleras, 2011[47]). Put simply, it is hard to concentrate on a task for a long time.

Workplace decisions and relationships suffer. Long hours contribute to decision fatigue, as making too many decisions throughout the day deteriorates the quality of choices. Workplace intangibles like emotional intelligence and interpersonal communication are also adversely affected by long hours. Overworked employees are more likely to be sleep-deprived (Faber, Häusser and Kerr, 2017[48])(Faber et al., 2015), which, in turn, reduces empathy towards others, weakens impulse control, diminishes the quality of interpersonal relationships, and makes it harder for people to cope with challenges (Killgore et al., 2008[49]).

Long work hours are also linked to poor physical health, which is bad for workers and for companies interested in retaining healthy employees. One obvious consequence of long work hours is a greater likelihood of workplace accidents, but there are also chronic risks such as increases in coronary heart disease, depressive episodes, and alcoholism (Virtanen et al., 2012[50]) (Virtanen et al., 2015[51]). Prolonged exposure to psychological stress, poor eating habits, lack of leisure time, and insufficient sleep take their toll.

Long working hours hurt families and partnerships, as well. Evidence across countries shows that children are negatively affected by their parents’ non-standard work schedules, which include work at night and on weekends. Parents are more likely to be depressed, parenting quality is likely to suffer, children and parents spend less time together, and the home environment is less supportive overall, especially in low-income families (Li et al., 2014[52]).

Long hours affect both sexes, but have gendered effects. In Korea and Mexico, fathers tend to lose time with their families, while mothers often drop out of the workforce entirely. The wage premium to long hours has been identified as a crucial remaining obstacle to gender pay equality (Goldin, 2014[53]). Within the workplace, men and women often break from long hour norms in different ways. In one US consulting firm, for example, researchers found that men pretended to work 60- to 80-hour weeks by strategically timing when to send emails, scheduling phone calls at odd hours, and discreetly taking leave without formal permission. In contrast, female workers were far more likely to make formal requests of reduced hours, and were consequently marginalised within the firm (Reid, 2015[54]).

Diminishing productivity of knowledge workers might be harder to quantify than that of manual workers, but many of the negative effects still exist: long hours contribute to stress, sleep deprivation, disagreements with colleagues, and mistakes on the job. Even software engineers argue that programming errors are more likely to occur (and take longer to fix) after long hours, despite the tech industry’s glorification of seemingly endless workdays (Robinson, 2005[55]).

Why do long hours of work persist?

Given the negative effects of long work hours, why do so many workers across the OECD still spend over 40 hours per week on the job? Both employer and worker behaviour play a role in perpetuating long hours. In many businesses, long work hours are a part of organisational culture and a way for employees to show that they are loyal and “ideal” workers (Cha and Weeden, 2014[56]) (Sharone, 2004[57]). For workers with lower incomes or unstable jobs, working additional hours may simply be a financial necessity. Fear of job loss is another key factor.

Employers, in turn, have been slow to realise that additional time in the office does not usually add value. Some research suggests that the wage premium for long hours is actually on the rise (Cha and Weeden, 2014[56]). Leaders and managers in organisations, who likely made time sacrifices to reach their current rank, often have difficulty accepting that work can be done in fewer hours. In some workplaces, “non-compliers” – those employees who opt to take flexible work hours and family leave – may actually be punished via denied promotions, reduced visibility to superiors, or exclusion from important projects. In-office “face time” remains an important metric of evaluating employees, even if it does not correspond with output (Elsbach and Cable, 2012[58]).

-

Instituting, publicising, and encouraging flexible work arrangements for both mothers and fathers can destigmatise taking time off for family reasons. This can also improve career and earnings opportunities for women within firms and help with the recruitment of a more diverse workforce. To this end, the Ministry of Employment and Labor publishes a brochure to share the experience of businesses that have successfully completed the transition to reduced working hours.

-

Give workers consistent schedules from week to week as much as possible, so that they can better manage work-life balance. This is especially important for low-income workers, who often struggle to find consistent and reliable childcare when their shifts suddenly change.

Managers should lead by example in working reasonable hours, as they are key to ensuring that workers feel comfortable ending their workday on time and have more job-satisfaction (Kim, Lee and Sung, 2013[59]). Field research in Korea shows that managers’ working hours and the perceived workplace overtime climate are the main reasons why employees work long hours (Zhang and Seo, 2018[34]).

3.5.2. Promoting flexible working arrangements

Workplace flexibility encompasses a range of practices that enable workers to adjust their work schedules and hours. They range from reduced hours and flexitime options (such as starting and finishing work at different times without reducing earnings) to more advanced options, e.g. working "compressed" weeks (working an extra hour each day and to get Friday afternoon off) or using “time accounts” to spread working hours across weeks or months. Workplace flexibility also includes working from home or teleworking. Greater access to such practices can reduce the number of workers who experience stress at home and/or at work, and thus diminish absenteeism and increase productivity (Bond and Galinsky E., 2011[60]). Flexible working arrangements are most likely to be widely available when they fit in with production and workplace organisation processes, so that their use enhances both workplace efficiency and worker well-being. Ideally, the implementation of flexible working time arrangements and associated policies is subject to regular evaluation to improve their functioning.

The reduction of working hours is one of the most common flexible workplace arrangements. Most OECD countries (24 out of 36 countries) allow workers to reduce working hours during their child’s early years. In most cases, this is to permit breastfeeding, but in several cases it has become a general right that can be taken for any reason and/or by the father (e.g. in Japan, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain). Women reducing their working hours in this way are entitled to earnings compensation, except in Austria, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway and Switzerland. In Korea, after childbirth, a female worker is entitled to a 30 minutes break two times a day to feed a child under 12 months (including breast-feeding and bottle-feeding).

In Korea, employees with 8 years old or younger children have a right to reduce their working hours. The government also provides SMEs with subsidies – KRW 300 000 (USD 247) per employee per month – to reduce the cost born by companies associated with the reduction in working hours. Financial support ranging from KRW 240 000 (USD 218) and 400 000 (USD 364) per employee per month is available to top up the reduced salaries of employees with reduced working hours. The Labour Standard Act also introduces possibilities to use flexible working hours (Box 3.3). About 8.4% of wage workers use flexible working arrangements (Statistics Korea, 2018[61]), but the use is rather low compared to practices in Europe. For example, 3 out of 4 European employees enjoy some form of flexible working, though shares vary from 50% in Greece to 90% in the Netherlands and the Nordic countries (OECD, 2016[62]). However, the development of flexible working time is promising for the future since four in ten wage (38.0%) workers who have not used flexible work arrangements report that they would like to use it in the future.

In most countries, access to reduced-hours working arrangements is a matter of right (albeit in some cases subject to satisfaction of one or more conditions pertaining to continuous service, size of employer, etc.). For instance, in Sweden, parents with a child under 8 years of age can reduce their working hours by 25% and receive proportionate earnings with no loss of their social security rights. In Germany, a parent working in a firm with 15 employees or more has the right to reduce their working hours to between 15 and 30 per week, and German policy is also committed to stimulating fathers to make use of part-time employment options, thereby making these more "gender neutral" and socially acceptable (OECD, 2017[17]). Rights to reduced working time and other flexible working time are also granted in many other OECD countries (Table 3.2).

Entitlements to part-time work can be conditional on workers having parenting or other caring responsibilities, while in a few countries, all employees can apply regardless of their family situation. For example, employees in the Netherlands, in companies with at least 10 employees, are entitled to change working hours (e.g. work part-time) unless the employers refuses the request because of compelling business reasons, which the employer would have to specify. In the Netherlands, the conditional entitlement concerns the employee’s existing job on reduced hours, rather than a transfer to a another part-time job. In order to apply for a change in working hours, the employee has to have one year of continuous service and provide four months’ notice.

Legislation in the United Kingdom grants workers a general “right to request” to access flexible working time (including part-time hours, changes in working-time arrangements and/or place of work) in the United Kingdom. When introduced in 2003, the legislation only applied to parents of young or disabled children. It was extended in 2011 to all parents with children (up to age 17), but in 2014 this condition was removed to prevent discrimination of workers with children (on the basis that they might apply for flexible working time).

Governments can help extend the coverage of flexible workplace measures by: encouraging on the issue; supporting a range of initiatives towards greater sharing of best practices amongst stakeholders; and by encouraging/financially supporting audits of companies to improve the family-friendly nature of workplaces. For example, in Germany in 2015, various stakeholders (including employer associations and unions) signed a memorandum on the “New Reconciliation” of work and family life (“Die Neue Vereinbarkeit”) (OECD, 2017[17]). The memorandum identifies areas of progress (e.g. greater awareness of flexible working hours in companies), but also surrounding existing challenges, and it develops guidelines for a successfully balance of work and life across the life cycle for employees and companies. This includes promoting reduced full-time working hours, i.e. less than 40 hours per week, particularly with regard to employees with care responsibilities for small children.

The labour standard law of Korea stipulates the use of flexible work arrangements, which allow employees to adjust their working-hours and workplace within the maximum 52 working-hours per week framework (The Labour Standard Act, 2019[63]) (Korea Ministry of Employment and Labour, 2017[64]).

-

The flexible work hours system (Article 51) allows employees to extend their working hours for some periods and reduce them at others for seasonal reasons or otherwise in either a two-week or a three-month timeframe, as long as the average working is 40 hours per week across the period (not including overtime and holiday work). In case of the two-week timeframe, employees can increase working hours on a particular day to 12 hours subject to a maximum of 48 per week. In the three-month timeframe, the maximum daily and weekly working hours are 12 and 52 hours, respectively.

-

The selective work hours system (Article 52) allows employers and employees to set the total working time for a renewable period up to a month at maximum as long as the overall working time averages to 40 hours per week, whilst giving employees control over start and finishing times during the period.

-

Recognising working time outside the workplace (Article 58-1, 2) aims to reward workers for working time that is difficult to specify (such as business trips)

-

Compensation leave (Article 57) allows employers to grant a paid leave to compensate workers for additional working hours (e.g. overtime).

-

The discretionary work system (Article 58-3) gives employees full control over his/her allocation of working hours needed to complete a specific task in a given timeline.

-

The telework system allows employees using modern technology to work from another location than the ordinary workplace for all or part of their working time.

Source: The Labour Standard Act (2019[63]), https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=46242&type=sogan&key=6; Kang, Kim and Ahn (2018[65]), Discretionary work system, http://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2018112718364188866.

No matter the level of policy support, progress in communications and mobile technologies will continue to provide more opportunities for many employees to work with flexible schedules, including working from home. Moreover, technological progress is likely to affect different jobs and occupations in different ways, which may widen rather than reduce inequalities in teleworking, and affect male and female employees differently given the existing gender segregation in employment (OECD, 2017[66]) (OECD, 2019[67]) (Chung, 2019[68]). Teleworking provides opportunities, but it also increases the risk that by working longer at home, the frontier between work and family life becomes more blurred. Industrial practice in Germany offers examples of sectoral or company-level agreements regulating out-of-office work. For example, in January 2014, German car manufacturer BMW reached an agreement stipulating that all employees are allowed to register time spent working outside the employer’s premises as working time, which opened up the possibility of overtime compensation. Employees are also encouraged to agree on fixed “times of reachability” with their supervisors.

3.5.3. Tackling labour market discrimination

For employees to freely use their rights to parental leave or flexible working time measures, they must be free of concerns that exercising their rights will have repercussions in terms of, for example, contract renewal or career progression. An effective legal system to combat such discriminatory practises can help allay such fears, and most OECD countries have put in place robust laws to combat gender discrimination in terms of wages, access to social protection rights, child-related leave entitlements or working time flexibility measures. (Timmer and Senden, 2019[69]). These laws also aim to address indirect discrimination that occurs where an apparently neutral provision, criterion or practice would put persons of one sex at a particular disadvantage compared with persons of the other sex, unless it is objectively justified by a legitimate aim. For example, less favourable treatment of part-time workers often amounts to indirect sex discrimination, as most part-time workers are women.

In Korea, the “Equal Employment Opportunity and Work-family balance Assistance Act” protects women against certain forms of discrimination. The law stipulates in particular that when recruiting or employing female workers, no employer shall consider physical conditions including appearance, height, weight and unmarried status. The law also requires that the employer shall provide equal pay for work of equal value, and that no employer shall engage in gender discrimination when providing benefits, training, or deciding on job assignments or promotion. It also gives the Ministry of Employment and Labour the possibility to oblige employers to put in place proactive measures to eliminate discriminatory practices and improve the situation of women in companies – in line with the affirmative action plans put in place several years ago (Box 3.5). Since 2017, the law has also included a chapter to combat sexual bullying harassment cases (enforceable since May 2019).

Recent cases, which have received widespread media coverage, illustrate that gender discrimination in the workplace also involves large companies (The Business Times, 2018[70]). Three of South Korea's largest banks have been accused of setting ratios for male and female recruitment, lowering women's test and interview scores and raising men's to hit the targets involved. A total of 18 executives have been charged or convicted, including the chairman of Shinhan Financial Group, the country's second-biggest lender. Discrimination is still apparent in many Korean human resource (HR) practices ranging from initial recruitment to contract termination (Patterson and Walcutt, 2014[71]), and new mothers are most likely to leave employment on childbirth when they work in male-dominated occupations where traditional notions on gender roles persist (Cha, 2013[72]) (Cho, Kwon and Ahn, 2010[73]).

There are different reasons for the persistence of gender discrimination in Korean workplaces. These include a lack of legal enforcement, a weak punishment system, a tacit acceptance of the status quo by women, prevailing traditional notions on gender roles and a general lack of knowledge on existing laws and regulations among companies, especially smaller ones (Rowley and Warner, 2014[74]) (Patterson and Walcutt, 2014[71]). Additional factors include the lack of effectiveness of Korea’s Affirmative action plans; the concentration of unskilled women in small firms and the employment sectors with a relatively high concentration of female workers have not assumed leadership roles in promoting affirmative action (Cho, Kwon and Ahn, 2010[73]).

To tackle discrimination effectively, Korea can do more to ensure compliance with and enforcement of employees’ rights. Several elements are important to make sure that non-discrimination laws are enforced, although practices may vary from country to country (Timmer and Senden, 2019[69]):

-

Workers who file a complaint or instigate legal proceedings have to be protected against dismissal or any adverse treatment that may occur because they undertook such action.

-

Proving discrimination is inherently difficult. Many national gender equality laws, therefore, put the burden of proof on the employer to make the case that he/she has not taken any discriminatory action.

-

Extend the capacity of the Labour Inspectorate to police and enforce adherence to anti-discrimination legislation. In 2016, the number of workers per labour market inspector was just over 20000 per worker, the ILO norm for transition countries. The Ministry of Employment and Labor planned to increase the number of inspectors to around 2000 in 2019, which would diminish the ratio to about 13 500 workers per inspector, which is closer to the norm for “developed countries” – 10 000 workers per inspector (OECD, 2010[75]).

As in other OECD countries, Korean society views violence against women (VAW) as a serious social issue, and the Korean government is putting efforts in place to address it.

Over the last decade, the prevalence of femicide (intentional female homicide) has reportedly decreased in Korea, while that of new forms of violence against women are on the rise (Kang, 2018[76]). The prevalence of reported sexual harassment and violence doubled between 2007 and 2016, from 29.1 cases per 100 0000 to 56.8 cases per 100 000. This might reflect raised public awareness, a higher likelihood of reporting, and/or strengthened government intervention on the cases of violence against women. In general, cases of violent sexual crimes including rapes are decreasing, while those of forced harassments and digital sexual crimes (such as taking or videotaping secret shots with smartphones and other devices) have increased greatly. The prevalence of dating crimes has also increased, jumping from 14.9 per 100 000 in 2012 to 19.9 in 2017. The majority of these dating crimes were violence and assaults (73.3%), arrests, detentions or threats (11.5%) (Kang, 2018[76]).

Domestic violence within the home is another common form of violence against women, typically (though not always) carried out by men against women. In 2016, the Korean Fact-finding Survey on Domestic Violence found that 12.1% of female spouses experienced domestic violence over the preceding year. This included physical violence, emotional violence, economic violence, and sexual violence. 8.6% of male spouses had also experienced domestic violence in the preceding year, most often taking the form of physical violence, emotional violence, economic violence, and sexual violence (Korea Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2016[77]).

Studies show that socio-cultural factors affect public attitudes towards sexual violence in Korean society. In particular, Korea’s patriarchal and male-centred culture contributes to a level of victim blaming when sexual violence occurs and hinders social and public interventions (Park, Han and Yoo, 2008[78]). One study of university students reports that those who have more negative attitude towards women, a higher acceptance of violence, and more hostile attitudes towards gender issues in general also think that victims should take more responsibility for sexual violence and are less likely to support the penalisation perpetrators (Kim and Park, 2011[79]).

The Korean government is putting in place several measures aimed at tackling VAW. The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and its related service centres, provide systemised support services for the victims of VAW. Women suffering violence are able to reach counsellors or police officers by phone, and move to emergency shelters, if necessary. The Sun Flower centres, 38 one-stop service stations across the country, collect evidence of violence and provide first aid to victims of sexual and physical violence. Counselling services, including physical and emotional rehabilitation services, are provided by counselling centres such as domestic and sexual violence centres, and victims can stay at protection facilities if necessary.

In the same vein, in 2016, the National Police Agency introduced Anti-Abuse Police Officers (APO) to support women suffering from domestic violence and abuse. In principle, APOs are supposed to visit every household reporting domestic violence if victims do not explicitly refuse, and APOs regularly monitor perpetrators when the court has issued a restraining order.

The Korean government continues campaigns to raise public awareness on VAW. In 2014, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family started the BORA Day campaign, designating the eighth of every month as a “BORA Day” (literally meaning the “look-again day”), when the public is encouraged to pay more attention to their neighbours to prevent and detect domestic violence. The Ministry regularly produces and distributes video or textual materials to prevent violence against women. Several laws – the Basic Act on Gender Equality, the Act on the Prevention of Prostitution and Protection of Victims, and the Act on the Prevention of Domestic Violence and Protection of Victims – oblige national and local governments, schools, kindergartens, and other public agencies to provide training on prevention of sexual harassment, prostitution, and domestic violence.

On average across OECD countries, almost one in three women report not feeling safe when walking alone at night, compared to one in five for men, and Korea is not an exception (OECD, 2019[80]). Several local governments have introduced programmes to ensure women are safe when returning home. For example, in 2013, the Seoul metropolitan government introduced the “women’s safe way back home” service – a service providing escorted transport from subway stations or bus stops to the home on advance appointment made over the phone or via an app. In addition, several local governments have developed smart police systems based on closed-circuit television (CCTV) and their own safe way back home apps (Yoon, 2018[81]). Under the smart police system, agents at integrated control centres in each city detect crimes using CCTV and information from apps transmitted by app users. Police officers are dispatched if a dangerous situation is detected.

-

The imposition of adequate sanctions on employers who are found culpable of discriminatory behaviour. Sanctions are diverse and depend on the nature of the infringement and could include: the annulment of unlawful provisions, nullify dismissals, or reinstatement of workers. Employees may be provided with financial compensation and, in some cases, criminal charges could be brought against perpetrators. For example, discrimination in the workplace may lead to imprisonment in Belgium, for one month to one year. The Finnish Penal Code prohibits discrimination at work based on sex and several other grounds with penalties varying from a fine to a maximum of two years imprisonment.

Ensure that alleged victims of gender discrimination have adequate access to courts: a lack of procedural knowledge, the slowness of proceedings and the associated cost can act as an important barrier to access to justice.