Assessment and recommendations

Norway is a highly developed, democratic country with a strong role for the state in strategic areas of the economy and high standards of living and wealth underpinned by the petroleum sector. A favourable business environment and the high quality of its institutions and policies also underpin high levels of economic wellbeing and a strong tradition of inclusiveness.

While only representing a small part of gross value added, agricultural properties are present in more than three-quarters of Norwegian territory. Average farm size remains relatively small, although rented land is playing a larger role, facilitating the consolidation of agricultural land and increasing farm size. As in many other countries, there has been a reduction over time in the amount of labour employed in agriculture. In many farms, agriculture and forestry coexist and farmers own most small forest lots. Land ownership by farmers and their heirs, and its agricultural use, are legally protected by the Concession Act, the Inheritance Act and the Allodial Act.

Agriculture is an exception in an otherwise open Norwegian economy. Norway is a net importer of agro-food products, but an even larger net exporter of fish and a highly active trader of wood products. Norway is integrated into global agro-food value chains, despite its highly regulated primary agricultural markets.

Agricultural support in Norway is the highest among OECD countries, with 59% of farmers’ revenues coming from support measures, as captured by the Producer Support Estimate (PSE). Policy reform has been modest. In the early 2000s, some payments were decoupled from commodity production. At the same time, market price support (MPS) was slightly reduced, but it continues to account for 44% of support to producers (PSE) and 40% of total support (TSE). Since then, there have also been small and controlled increases in imports through quotas. Unlike agriculture, the highly competitive fisheries and forestry sectors are not dependent on trade protection and government support, notwithstanding some government funding, particularly for the latter.

The Norwegian Agricultural Innovation System consists of a number of specialised institutes and universities, forming part of an economy-wide innovation system operating within the European Research Area. This system has most notably produced good results in animal breeding. Farmers’ organisations and co-operatives participate in innovation in all parts of the food chain. The system is vertically organised, with the Ministry of Agriculture and Food earmarking the R&D priorities for the agro-food sector.

Agricultural policies are the result of a political consensus underpinned by an institutional dialogue that is undertaken across most sectors of the economy. Farmers’ organisations take part in policy decision making and are responsible for the implementation of some elements of policy. In addition, farmers’ co-operatives are in charge of enforcing market regulations. The implementation of policies is transparent, with public access to farm level information, including farm structure and payments. The annual negotiation between farmers and government is focused on payments and selected prices and sustaining revenues. While this provides an element of trust and stability and reduces the decision-making costs, it is likely to constitute a barrier to bringing other emerging long-term objectives to the front of policy decisions and so can impede more fundamental reforms.

Norway has ambitious environmental objectives, which include a reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of at least 50% by 2030 under the Paris Agreement and stringent environmental regulations. However, these ambitions are not reflected in agricultural policies that, for example, do not impose carbon taxes for emissions from soils and livestock, or subject agriculture to other climate policies, despite these being the origin of 8.5% of national emissions. Agricultural support is provided on the premise that it delivers public goods, such as landscape and biodiversity, and rural development, jointly produced with commodities, even though production increases emissions.

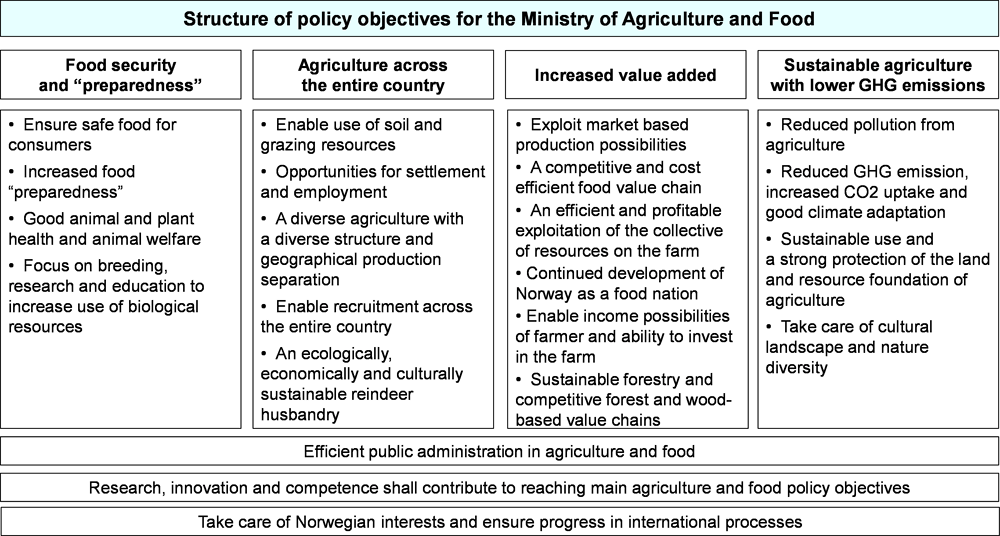

The four policy objectives for agriculture in Norway are (i) food security and preparedness; (ii) maintaining agriculture across the entire country; (iii) increasing value added; and (iv) sustainable agriculture with lower GHG emissions (Ministry for Agriculture and Food, 2016[1]) (Figure 1).

Norway enjoys a high degree of food security, and agricultural production and associated landscapes are present in all regions. However, Norway is not performing well in its sustainability objectives, while productivity growth and the generation of value added in the food industry are hindered by market regulations in the primary sector (Productivity Commission, 2015[2]).

There is, nonetheless, a question of whether the first two objectives are being attained in the most efficient and equitable manner. Policy tools have focused on providing support coupled to production, including market price support sustained by trade measures and market regulations. Previous OECD analysis shows that this type of policies is an inefficient and inequitable way of delivering support to farmers, which imposes an unnecessarily burden on consumers in low-income households, and on taxpayers. While food security (gauged in terms of availability) and maintenance of production capacity are assured, this comes at some social cost even in a high-income country like Norway with a relatively low average share of household expenditure dedicated to food. These policies are also sustained by trade barriers and contribute to distortions in international markets, creating negative spill-overs for producers in other countries, including developing countries. Moreover, the same policies, as discussed below, also weaken innovation and performance with respect to value creation and sustainability.

In sum, alternative policy approaches can do better in ensuring food security and the geographical presence of agricultural activity, without imposing the obligation to produce. The new approach would change current production patterns and, possibly, reduce the level of production of some commodities, but will create opportunities for innovation and reduce the negative effects on the objectives related to sustainability and generation of value added in the food sector.

While not all the objectives of Norwegian agricultural policies in Figure 1 are included specifically in the OECD Productivity-Sustainability-Resilience (P-S-R) framework and associated indicators (the goal of maintaining agricultural production throughout the country is specific to Norway), the fundamental goals of Norwegian policies are reflected in P-S-R outcomes. Indeed, productivity, sustainability and resilience are pre-requisites for the efficient and effective achievement of these fundamental goals and objectives. For instance, productivity growth is desirable because a more efficient use of resources responds the desire for enhanced food security and preparedness and to objectives under value added (such as farmer income and investment and competitive value chains). Equally, Norway’s sustainability objectives can be assisted by productivity improvements that reduce input use. The OECD P-S-R framework and indicators not only enable analysis to hone in on important means to achieve objectives for the sector, and to track progress, but also to provide insights on the relationship between the attainment of different objectives. That is, some policies aimed at one objective can not only be relatively inefficient in achieving that objective, but can undermine progress on others, while appropriate policy packages can support the efficient attainment of objectives across these areas. This analysis is supported by the OECD’s agri-environmental indicators, which can provide useful insights into progress on many of Norway’s environmental sustainability objectives.

Productivity growth has not led to improved sustainability

Over the past two decades, the productivity of Norwegian agriculture, as captured by total factor productivity (TFP), has grown at an annual rate of 2.2%, compared with an OECD average of 1.4%. TFP growth was not mainly driven by innovation that reduced the amounts of land and purchased inputs needed to produce a given output, but by the movement of labour out of the sector and associated adoption of capital intensive and labour saving technologies. As a result, the high rate of TFP growth has not contributed to improved environmental performance. This trade-off between productivity and sustainability is particularly concerning because, according to existing agri-environmental indicators, Norway's current levels of nitrogen and phosphorous surpluses, which place pressure on soil, water, and air quality, are amongst the highest in the OECD. In some regions, agricultural production with high density of livestock is also reaching its limits in terms of negative environmental impacts. In terms of changes in environmental pressures over time, sustainable productivity growth has been weak when compared to other OECD countries (Chapter 6).

Current food security comes at an unnecessarily high cost

Food security is an objective shared by all countries. Norway’s objectives define this in terms of ensuring a supply of safe food for consumers, good animal and plant health and animal welfare (see first column in Figure 1). However, the rate of domestic self-sufficiency is at best an incomplete indicator of food security (Productivity Commission, 2015[2]); for Norway, food security is ensured through three components: national production, trade and safeguarding production resources (Ministry for Agriculture and Food, 2016[1]). Agricultural border protection that reduces trade, along with coupled farm support measures, focus on increasing domestic production. This serves to maintain agricultural production and landscapes in areas where they would not otherwise be viable, but result in higher food prices and budgetary cost, with both equity and opportunity cost implications.

The resilience of the Norwegian food system with respect to systemic shocks and the core role of international food trade in contributing to food security has been highlighted by the results of the 2017 report on Risk and Vulnerability of Norwegian Food Supply (Directorate for Social Security and Preparedness (DSB), 2017[4]). These high levels of food security are the result of the functioning of the food value chain through trade, and of regulations in areas such as food safety and health. Norway is a net food importer and its food security objectives are to a great extent achieved through trade and value chains that are globally interlinked.

The current patterns of support and barriers to trade may not be necessary to ensure the food security objectives; other approaches may do so at lower cost. Safeguarding land resources does not necessarily require actual incentives to produce, but to keep land and soil in good condition and capable of producing. Payments can be targeted to this purpose. Moreover, other aspects of the food security objective in Figure 1, such as food safety, animal and plant health and animal welfare are achieved through effective regulatory provisions and specialised agencies. Furthermore, Norway can make an important contribution to global food security through its comparative advantage on research and innovation, including breeding. However, Norway’s agricultural support measures are highly coupled to production, encourage current production decisions and provide a disincentive for innovation.

The agricultural landscape could be preserved with more cost effective tools

The objective of having agriculture across the entire country is specific to Norway. Agricultural land in Norway is, to a great extent, land that would otherwise be forest. The protection and support for agricultural land use reflects a desire to preserve this open landscape.

Legal protection of agricultural land use and agricultural policies – mainly location specific rates of price support and coupled payments – have been designed to maintain regional production. This policy set – sometimes called “production channelling” policies – has succeeded in preserving agricultural land and cultural landscape, keeping production in unfavourable areas. However, a tighter focus on the economic incentives determining whether or not to allocate land to agricultural production (the extensive margin) rather than on production incentives (the intensive margin) can be more efficient.

Policies can be targeted to the extensive margin of agricultural land to keep it in use as part of the landscape without requiring any specific production. This would maintain the capacity to use land, soil and grazing resources. It would also create incentives for activities that are economically and environmentally sustainable, while preserving the landscape and leaving farmers the freedom of choice and scope for entrepreneurship to foster innovation. If decoupled from production, these measures increase farm income because they create more revenue with lower input costs, and this additional income implies higher economic incentives to preserve land usable for agriculture and the landscape.

Current support policies reduce the competitiveness in food value chains

Increasing value added requires exploiting market opportunities in food value chains, enhancing competition and competitiveness for an efficient management of the food system, and reducing the high costs of primary agricultural inputs. Supported prices and regulated markets reduce the incentives to create value added, while transferring income to farmers less efficiently than decoupled forms of support. Agriculture TFP growth in Norway has been driven by reductions in the contribution of labour, which also suggests that high levels of coupled support have nonetheless not been able to overcome structural factors pulling labour out of the sector.

High primary agriculture prices also reduce incentives to innovate or make more efficient use of inputs, thwarting the competitiveness and capacity of value creation downstream. While the degree of concentration at retail level is similar to neighbouring EU countries, market concentration at the wholesale level in the dairy and meat sectors is high. There is also evidence of higher prices and lower diversity of food products in Norway than in neighbouring EU countries –and, while product diversity has improved, food price differences with neighbouring countries have increased. Agricultural policies and regulations could be better targeted to create incentives for innovation in the whole value chain – which could also bring benefits in terms of other objectives, by promoting a path of productivity growth that also promotes improved environmental outcomes.

Current policies make meeting environmental goals more challenging

The sustainability objective for agricultural policies in Norway has a strong focus on lowering GHG emissions (Figure 1), although agriculture is exempted from key policies seeking to achieve these ambitions, notably carbon taxes (except those on fossil fuels) and other emission mitigation schemes. Notwithstanding regional differences, the performance of Norway on emissions and pollution from nutrients is weak compared to other countries, including other Nordic countries and high livestock density countries like the Netherlands. Meeting international commitments related to GHGs, ammonia emissions and water protection is challenging. Displacing production to unfavourable areas may dilute pollution, but difficulties stem from the separation between livestock production and arable crops, which leads to reduced nutrient efficiency and higher ammonia emissions. Gains could be obtained from redesigning “production channelling” policies, decoupling them from specific production, and therefore reducing the incentives to produce, and targeting different regions with differentiated payment rates, while keeping open farmers’ options for different mixes of crop and livestock production.

Norwegian agricultural policies are underpinned by the premise that rural development and several public goods are positive externalities produced together with agricultural commodities, such as landscape, biodiversity and ecosystem services, and that implementation costs of alternative policies are quite large. The OECD work on “multifunctionality” has demonstrated that this view is valid only if the public good externalities cannot be separated from the production (they are “joint and non-separable outputs”) (OECD, 2003[5]; Hodge, 2008[6]).

At the extensive margin of production, if land is not used for agriculture in some Norwegian regions, there is a risk of abandonment, with resulting loss of habitat and cultural heritage. In such cases, continuation of extensive farming practices is an advantageous option both for production capacities and biodiversity preservation and landscape maintenance. However, at the intensive margin of production, as resources are over-used, production may lead to negative environmental outputs such as nutrient run-offs. In this case, agricultural policies coupled to production enter into conflict with environmental considerations. Moreover, even at the extensive margin in the use of land, there might be a conflict between agricultural policy objectives and some environmental objectives, for example with policies seeking to increase production raising GHG emissions. Environmental objectives most often require targeted measures, whereas coupled support contributes to exacerbate emissions intensity and other negative environmental outcomes. For instance, recent legislation restricting the cultivation of peatlands – one of the largest sources of GHG emissions from agriculture in Norway – goes in the right direction and gains could be obtained from an ambitious application of this type of targeted measure.

Norway delivers high standards of animal health and welfare

While antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is not explicitly mentioned in the list of objectives in Figure 1, it is strongly linked to the objective of animal welfare (while also affecting human health and the environment). Moreover, the Norwegian Government has AMR as a top priority both on the national and international agenda. Norway has a strong performance on animal health, and has undertaken long-standing efforts to promote increased awareness about AMR. The prevalence of contagious animal diseases is low in Norway and use of antibiotics in animals is amongst the lowest in Europe. Norway has had a regularly updated cross-sectoral action plan against AMR since 2000 and a livestock industry action plan since 2017. OECD work shows that optimising the use of antibiotics on animal farms from the standpoint of animal health, and avoiding their use for purposes of growth promotion, has little or no adverse impact on the economic or technical performance of the farms (Ryan, 2019[7]).

The Agriculture Innovation System faces challenges in both ensuring effectiveness and addressing cross-sectoral issues

Despite good results in terms of scientific publications, the agricultural innovation system should increase the participation of the private sector. That said, tax incentives for innovation at the firm level (SkatteFUNN programme) are generous and user friendly, and reach SMEs and peripheral regions. Innovation policies in Norway are organised in line with sectoral responsibilities by the different ministries, including the Ministry for Agriculture and Food (LMD). This sectoral approach reduces the capacity of the innovation system to respond to long-term societal challenges such as climate change, with strong cross-sectoral priorities. Low cost effectiveness of public innovation policies are a concern for both the agriculture and the economy-wide innovation systems.

In sum, policy objectives need to be re-balanced while improving cost-efficiency

Norwegian agricultural policies navigate complex trade-offs between different objectives. There is evidence that Norway is meeting its objectives for food security and production across the country, but with policies that undermine delivery on the two other objectives of value creation and sustainability. Furthermore, the delivery of the first two objectives can be pursued effectively without market distorting measures in a more cost-efficient way.

Norway can reform its policy package in order to achieve a better balance of outcomes across its agricultural policy objectives. The priority is to improve the delivery on environmental outcomes and the economic competitiveness of the sector, while enhancing the cost-efficiency of keeping agricultural land use and landscape across the country and maintaining high standards on food security, food safety and health. Undertaking such an ambitious policy re-orientation will require an evaluation of how to make the current agricultural policy-making process more focused on emerging long-term challenges. The new policy approach should be guided by four main long-term drivers: an increased responsiveness to markets; a new decoupled “production channelling” scheme; a strengthened focus on agri-environmental outcomes; and an upgrade of the agricultural innovation system. Finally, new risk management policies should enhance farmers’ resilience.

1. Allow a better balance among objectives through reform of the political economy process of negotiations between the farmers and the government

The consensus institutional framework of annual negotiations and agricultural agreements between farmers’ associations and the government in Norway provides stability and a platform for regular evaluation and gradual adjustment. However, negotiations focus almost exclusively on annual farm incomes, thereby paying insufficient attention to other societal concerns and long-term objectives of government policy. Current emerging societal concerns such as climate change and nutrition face difficulties in finding their way into policy considerations.

Undertake an assessment, including opportunities for public submissions, of whether the current format of annual negotiations between government and farmer representatives is well-suited to promoting reform and addressing emerging policy objectives.

Explore alternative or supplementary mechanisms. For example, building on the experience of the recent voluntary agreement with farmers on climate change, negotiation of some aspects of policy, such as agri-environmental sustainability, could be part of multiyear framework agreements with a longer-term perspective and open to input from other stakeholders. Some aspects of the negotiation could also be opened to other fora, with the participation of other stakeholders such as consumers, the downstream industry and environmental players.

Maintain the current approach of providing transparency over farm level payments and activities, and make further use of farm level information for policy design and monitoring of outcomes.

2. Promote food security, landscape and sustainability more cost effectively through reforms to support and increase responsiveness to market signals within a well-defined time horizon

The objectives of food security, agricultural landscape and environmental sustainability could be achieved more efficiently through targeted measures that relied more on innovation and competition. To this end, market price support, border protection and market controls should be gradually reduced. Providing a clear and agreed time horizon and direction for this gradual reform process will ensure transparency and policy predictability, and facilitate investment.

Keep land in agricultural use by providing appropriate amounts of decoupled support to farmers that is more efficient in transferring income and creates incentives to keep land in agricultural use. These payments would be integrated in a new generation of payments.

Improve consumers’ access to a variety of affordable food by reducing border protection of most protected commodities such as meat, milk and cereals. Gradually reduce tariffs and make them converge to a predetermined level after a transition period, and expand imports through TRQs, converging to a given level of market access.

In order to make primary agriculture more competitive and thus support more competitive value chains, gradually reduce market-restricting regulations. Liberate co-operatives from their market regulator role and transform target prices into indicative prices not binding for co-operatives, then gradually reduce them. Continue to allow co-operatives to organise farmers to better compete in the market with other players. As the processing industry will gain in competitiveness, subsidies to buy domestic agricultural products (processed food RAK products and price equalisation schemes) should be gradually phased out.

Undertake an assessment of the application of competition policy with the aim of better defining the limits of the primary agriculture exception. Investigate the possibility to extend the application of competition policy upstream in the food system to the wholesale sector as part of this system.

Strengthen the consumer information system building on existing initiatives like “Enjoy Norway”, investing in the brand of Norway’s food as quality food with specific attributes and farming practices such as animal husbandry with high animal welfare standards and low use of antibiotics. This system allows consumers to reveal their preferences and willingness to pay for these practices and public goods.

3. Increase the efficiency of landscape objectives by creating a new generation of decoupled “production channelling” policies

Efficiently achieving landscape objectives requires modernising policies designed to maintain land in agricultural use in all regions of Norway. If support is decoupled from production decisions, farmers will better leverage the location of their farm and its specific economic comparative advantage and environmental situation. A well-defined transition period will ensure smooth adjustment.

Create a new scheme that includes a decoupled payment based on historical area and requiring that land be kept in agricultural use. Shift a portion of current coupled support based on animals, output and land, and the partial compensation for price reductions into the new scheme. The payment will create additional economic incentives to keep land in agriculture beyond the legal incentives from land use regulations, while ensuring farmers have incentives to innovate and improve the use of the land.

The main objective of the new payment would be to provide cultural landscape and land ready to produce agricultural products, and to provide ongoing income support to farmers. The payment should be targeted to the extensive margin, applying differentiated payment rates for different land, adjusting to the reality of land characteristics in each region or location in order to cover the costs of keeping land in agriculture and avoid the move into forestry or abandonment. Payment rates are already differentiated by region in the current policies, but they are mostly coupled to specific production choices. The new payment should be decoupled from specific production decisions.

Undertake a study to better define agricultural use in different areas and invest in strengthening the information behind the map of regions and areas that – because of their differentiated landscape value - may deserve different rates of payments. Develop measures of landscape quality or environmental risk based on scores that identify the most valuable or risky agricultural lands. Payments could then be tied to the score received by the land in a grading process.

Update the implementation of land regulation polices to add more flexibility in land definitions and change of use while keeping the objective of total landscape areas. Many farms in Norway have also small forestry plots as part of their holdings and business model. Encouraging consolidation of plots can bring efficiency and gains for farmers. Provide flexibility in land regulations or in their implementation to encourage innovative new land uses that add value for both agriculture and forestry.

Ensure that the new scheme and the land use legislation are applied in a way that does not interfere unduly with consolidation and rationalisation of agricultural production and the use of forest land.

4. Invest in a sustainable sector through risk management polices with a resilience approach

In 2018, Norway experienced the driest and warmest summer for the last seventy years and several ad hoc measures and increases in existing payment rates were implemented to help farmers. Extreme weather conditions are likely to increase with climate change and drought support measures should focus on encouraging preparedness and resilience through the extension services and voluntary risk management programmes, rather than on the provision of ex-post financial aid.

Enhance the role of farmers in managing business risk by introducing voluntary risk-management programmes such as mutual funds, or a programme that allows farmers to place savings in a special account with incentives from the government such as tax exemptions. These savings could be withdrawn after an extreme event such as a drought, or for investing on on-farm resilience measures.

5. Strengthen achievement of sustainability objectives through a new agri-environmental strategy for agricultural policies in Norway

All agricultural policies should embrace a strengthened focus on agri-environmental outcomes, including the new “production channelling” scheme and other programmes. Norway could develop a strategy to fully internalise the environmental pressures from agriculture, in particular those from nitrogen and phosphorus surpluses and emissions. The additional public goods to be delivered by farmers that may not be delivered by the new scheme need also to be well defined in this strategy.

Building on the current agreement with farmers’ organisations, develop an ambitious strategy to significantly reduce GHG emissions from agriculture. Economic incentives should be provided by restructuring support under the new scheme and by ending the exemption of agriculture from the main emissions reduction policies such as cap-and-trade system or GHG emission taxes.

Develop and adopt a definition of reference levels and environmental targets for agri-environmental policies. The reference level would be the minimum level of environmental quality that farmers are required to provide at their own expense, and environmental targets represent a higher desired level of environmental quality. To establish a solid and efficient framework of agri-environmental policies, Norway should clarify the reference environmental quality, as well as environmental targets which are well adapted to local ecological conditions.

Develop an information system for monitoring and evaluating agri-environmental policies and outcomes, using all the information already available at farm level from farmers’ files and from the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO) and other sources. Use digital technologies to connect different sources of information and link them to decision making.

Apply the polluter-pays-principle more systematically with regulations that hold farmers accountable for all harmful environmental effects from crop and livestock pollution. The development of environmental plans at the farm level could make farming more environmentally accountable. These plans would need to be enforceable, with strengthened monitoring capacities using digital technologies. They need to respond to current and new regulations, including on a more balanced application of nitrogen fertiliser.

Increase the share of payments conditional on adopting specific farming practices for environmental reasons beyond the current share of 15% of total support to producers. Such conditionality can be effective if adapted to the diversity of local farming practices and conditions, and included in the farm level environmental plans. Create incentives for improving farm practices and technology adoption for better manure management through strengthened general environmental regulation and increasing cross compliance with location specific conditionality. Examples – some of them already underway – could include promoting low emissions application techniques (such as injection or band spreading), reductions in ammonia emissions and nitrogen, and restriction on cultivation of peatlands. There is also scope for strengthening the efforts of advisory and extension services in specific areas; for instance, to increase the utilisation of livestock manure through improved nutrient management planning.

Explore the possibility of developing agri-environmental programmes based on outcomes rather than practices. Notwithstanding the implementation difficulties, Norway should advocate performance-based agri-environmental policies that reflect the diversity of its agri-environment. Payments would remunerate farmers for the provision of environmental outputs that Norwegian society wants. Provision could go beyond what is expected of farmers as reference levels, and payments could be made available based on more ambitious outcomes, after a transparent assessment in terms of costs and benefits, and within the overall budgetary constraints.

6. Add value and promote sustainability by upgrading the agricultural innovation system through greater private sector engagement and a cross sectoral focus

The Norwegian agricultural innovation system has well-developed institutions. Despite the small size of the sector, the R&D system in Norway produces a larger share of agri-food patents and publications than in other countries. However, agricultural innovation needs more dynamic engagement by the private sector, focusing research and adoption at firm and farm level on emerging areas of social interest. The current priority of development of the bio economy provides a good basis in which Norway can find potential areas of comparative advantage. Increasing innovation by the private sector in agri-food requires stronger incentives and signals from markets to identify opportunities to innovate. The reduction of price support and the introduction of decoupled payments will also strengthen the link between innovation and market returns.

Building on recent developments, strengthen cross-sectoral innovation prioritisation and further strengthen the strategic role of the Research Council of Norway and Innovation Norway in the agricultural innovation system. Policies should invest in consolidating multidisciplinary and multi-sectoral research and innovation networks with increasing leadership from a more competitive industry. The Long-Term Plan for Research and Higher Education process should be more actively used for broader cross-thematic priority setting.

Strengthen the independence and cross-sectoral collaboration of agricultural research institutes under LMD (NIBIO, VI and Ruralis). Keep high incentives for research excellence, maintain basic funding for the long term strategic plans and ensure their independence. These institutes should be encouraged to actively embrace research multidisciplinary co-operation with other actors in other sectors.

Assess the performance of the FFL levy fund and JA innovation funds which are interesting initiatives to engage farmers and the private sector, and propose improvements in their governance. The assessment should explore the opportunity to broaden the focus of both funds towards long-term transformative innovation challenges and new opportunities for the industry. The current interlinks between the two funds could be enhanced, channelling the financial resources of both through a single merged fund for agricultural research. Alternative modalities for funding such as linking the amount of government funding to that from the industry could also be explored to a greater extent. A larger single fund combining and linking public and private resources is likely to enhance the strategic long-term approach and incentives to private innovation.

Enhance current priorities for the bioeconomy and the interlinkages with other sectors and climate change to contribute to a circular economy. Link innovation with the new policy focus on agri-environmental performance. Encourage more co-ordination between forestry, agriculture and aquaculture on innovation in new products and processes like bioenergy.

Build on the comparative advantage in specific scientific areas, in particular in animal breeding where there is research capacity, knowledge and well-positioned private enterprises. Identifying such areas could allow the agri-food sector and support policies to shift focus to producing and even exporting knowledge rather than focusing on producing specific commodities.

Invest in digital technologies to develop an information system for the monitoring of the agri-environmental performance of farms and for the redesign of policies towards environmental sustainability priorities. Norway has considerable geo-localised data and information from different sources. The government should commit to the use of this information system in the implementation, design and evaluation of its agri-environmental programmes. The new information system will respond to the emerging climate and environmental challenges and contribute to innovation in this area.

Keep and strengthen international cooperation for agri-food research and innovation. This includes collaboration and partnerships for funding, project design and implementation, publications and adoption of innovation.

Norway should pursue policies to improve the competitiveness of wood-based products relative to traditional concrete and steel. This could include changes to building codes to decarbonise construction, mandates for use in public buildings, and tax credits.

References

[3] Agriculture Budget Committee (2019), Resultatkontroll_2019, NIBIO.

[4] Directorate for Social Security and Preparedness (DSB) (2017), Risiko-og sårbarheits-analyse av norsk matforsyning - Risk and vulnerability in Food Supply, for samfunnstryggleik og beredskap (DSB).

[6] Hodge, I. (2008), “To what extent are environmental externalities a joint product of agriculture? Overview and policy implications”, in OECD (ed.), OECD Multifunctionality in Agriculture: Evaluating the Degree of Jointness, Policy Implications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264033627-en.

[1] Ministry for Agriculture and Food (2016), Melding til Stortinget Endring og utvikling - White paper to the Parliament: A future-oriented agriculture production er on future orientations for agriculture, http://www.fagbokforlaget.no/offpub.

[5] OECD (2003), Multifunctionality: The Policy Implications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264104532-en.

[2] Productivity Commission (2015), Productivity – Underpinning Growth and Welfare, Summary and the Commission Proposals, 13.15, https://produktivitetskommisjonen.no/files/2015/04/summary_firstreport_productivityCommi.

[7] Ryan, M. (2019), “Evaluating the economic benefits and costs of antimicrobial use in food-producing animals”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 132, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f859f644-en.