4. Ensuring cross-cultural reliability and validity

The purpose of this chapter is to present a reliability and validity case study investigating the scoring of the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) of higher education students in Finland as well as the United States. This study contributes to the overall literature on establishing equivalency for an international assessment of students’ critical thinking and written communication skills. Two prior studies, similar in nature, both found that results from a translated and adapted performance-based assessment are comparable (">Zahner and Steedle, 2014[1]; Zahner and Ciolfi, 2018[2]). This chapter presents a third case using CLA+ across two languages and cultures.

One of the main concerns surrounding an international assessment is the reliability and validity of the process, particularly because the translation and adaptation of the assessment is especially challenging (Geisinger, 1994[3]; Hambleton, 2004[4]; Wolf, Zahner and Benjamin, 2015[5]; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, Shavelson and Kuhn, 2015[6]). Although international assessments such as the Organisation for Economic and Co-operation Development’s (OECD) own Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) are well-established and widely adopted, international assessments in higher education are especially challenging because differences across countries (e.g., educational systems, level of autonomy of higher education institution, socio-economic status) increase the complexity of testing (Blömeke et al., 2013[7]). This becomes even more challenging when using performance-based assessments, which require higher education students to generate a unique response as opposed to selecting one from a set of options.

However, this global research collaboration has created an opportunity to investigate cross-cultural comparisons of a performance-based assessment of generic skills. One such opportunity is through the translation and adaptation of assessments into students’ native languages to be administered and scored across countries. Due to differences in culture, language, and other demographics, one important study is to examine the reliability of such translations and adaptations, particularly for a performance-based assessment that includes writing. In order to draw valid score inferences, it is assumed that individuals who earn the same observed score on these instruments have the same standing on the construct regardless of the language in which they were assessed. The evaluation of several criteria could aid in meeting the assumption:

2. The construct is measured in the same manner across nations.

3. Items that are believed to be equivalent across nations are linguistically and statistically equivalent.

4. Similar scores across different culturally adapted versions of the assessment reflect similar degrees of proficiency.

The purpose of this chapter is to present a reliability and validity case study investigating the scoring of the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) of higher education students in Finland as well as the United States. This study contributes to the overall literature on establishing equivalency for an international assessment of students’ critical thinking and written communication skills. Two prior studies, similar in nature, both found that results from a translated and adapted performance-based assessment are comparable (Zahner and Steedle, 2014[1]; Zahner and Ciolfi, 2018[2]). This chapter presents a third case using CLA+ across two languages and cultures.

Performance tasks and scoring

In a Performance Task (PT), students are asked to generate their own answers to questions as the evidence of skill attainment (Hyytinen and Toom, 2019[8]; Shavelson, 2010[9]). PTs are typically based on the criterion-sampling approach (Hyytinen and Toom, 2019[8]; McClelland, 1973[10]; Shavelson, 2010[9]; Shavelson, Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and Mariño, 2018[11]). In that sense, their aim is to elicit what students know and can do (McClelland, 1973[10]; Shavelson, 2010[9]; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019[12]). That is, PTs engage students in applying their skills in genuine or “authentic” contexts, not simply memorising a body of factual knowledge or recognising the correct answer from a list of options. A PT, with its open-ended questions, requires the integration of several skills, for example, analysing, evaluating, and synthesising information and justifying conclusions by utilising the available evidence (Hyytinen et al., 2015[13]; Shavelson, 2010[9]).

Recently, several challenges relating to the use, reliability, and interpretation of PTs have been reported (Attali, 2014[14]; Shavelson, Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and Mariño, 2018[11]; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019[12]). Answering a PT takes time and effort from students. Thus, relatively few constructs can be observed and assessed within one PT compared to multiple-choice tests (Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019[12]). Another challenge relates to scoring. The way in which students’ responses are scored plays a crucial role in assessment validity (Solano-Flores, 2012[15]). The scoring criteria of PT responses need to be developed and defined so that they are in line with the construct measured (Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019[12]). Moreover, students’ written responses are typically scored by using human evaluation. Therefore, it has been suggested that the scoring of PTs is open to bias (Hyytinen et al., 2015[13]; Popham, 2003[16]).

In scoring, the scorers analyse the quality of the response based on a scoring rubric that describes the characteristics of typical features at each score level. It has been assumed that it is very difficult for scorers to converge on a single scoring standard (Attali, 2014[14]; Braun et al., 2020[17]). Disagreements about the quality of the response across the scorers result in inconsistencies in scoring. However, most of the inconsistencies stem from incorrect interpretation of the scoring rubric (Borowiec and Castle, 2019[18]). Extensive scorer training and rubric development via cognitive interviews have been proposed as solutions for ensuring consistent scoring (Borowiec and Castle, 2019[18]; Shavelson, Baxter and Gao, 1993[19]); see also Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al (2019[12]). Consequently, the use of PTs is considered time-consuming and expensive, as a large amount of time and effort is needed to train scorers and to score the responses consistently (Attali, 2014[14]; Braun, 2019[20]).

Cross-cultural challenges in PT scoring

Cross-cultural assessments may have challenges due to cultural and linguistic differences or technical and methodological issues (Hambleton, 2004[4]; Solano-Flores, 2012[15]). This case study focuses on cross-cultural challenges in the scoring of PTs. To our knowledge, cross-cultural scoring presents two types of possible challenges. First, the scoring rubric may not meet the conventions of the second culture, in this case Finnish. Second, scorers may interpret responses and the scoring rubric in a different way than originally intended due to cultural differences (Braun et al., 2020[17]). For instance, in Finland there is no substantive assessment culture: there are hardly any high-stakes assessments in schools or higher education institutions (e.g., (Sahlberg, 2011[21])), and therefore, scorers may have limited experience with such evaluation.

Furthermore, Finnish is inherently different from English, which is the original language of the present assessment. Finnish belongs to the Finno-Ugric language group, distinct from English and Indo-European languages. This means the languages are structurally very different. It also seems that linguistic conventions are different between the two languages. For instance, it has been found that Finnish has different rhetoric practices compared to English (Mauranen, 1993[22]). These differences between languages may influence how scorers from each country interpret responses and scoring principles.

It has been noted that often in cross-cultural assessments, the same individuals do not establish the content to be assessed, write and develop the task, create the scoring rubric, and score students’ answers. Therefore, it is important that there is a shared understanding of the elements of the assessment among different contributors in order to make sure that the constructs are measured and scored in the same manner across cultures (Solano-Flores, 2012[15]).

This case study stems from a national project that investigated the level of Finnish undergraduate students’ generic skills, what factors are connected with the level of generic skills, and to what extent these skills develop during higher education studies (Ursin et al., 2015[23]) (Chapter X). The participants were students at the initial and final stages of their undergraduate degree programmes. During the 2019 -2020 academic year, 2 402 students from 18 participating Finnish institutions completed a translated and culturally adapted version of the CLA+ that included a PT and a set of 25 selected-response questions (SRQs). This case study investigates a subset of the students’ PT responses.

As described in detail in Chapter 2, CLA+ is a performance-based assessment of analytic reasoning and evaluation, problem solving, and written communication skills. It consists of two sections: a PT, which requires students to generate a written response to a given scenario, and SRQs. Students have 60 minutes to complete the PT and 30 minutes for the SRQs.

United States context

In the United States, most participating institutions of higher education have traditionally used CLA+ for value-added purposes. To this end, they assess a sample of entering first-year students typically during the fall semester and compare those students to a sample of exiting fourth-year students typically assessed during the spring semester. The demographic characteristics of the student population in the USA are presented in Table 4.1.

Finnish context

The main feature of evaluation in Finnish higher education is that it is enhancement-oriented so that the focus is on providing support and information to further enhance the quality of the programmes and institutions. Consequently, the evaluation of Finnish higher education favours more formative ways of evaluation as opposed to summative evaluation focusing on the achievement of specified targets (Ursin, 2020[24]). Hence, the use of standardised tests, such as CLA+, is not typical in Finnish higher education institutions, and this case study was the first of this calibre to utilise a standardised test to investigate generic skills of Finnish undergraduate students. Nonetheless, similar to the United States, the 18 participating higher education institutions from Finland tested entering first-year students typically in the fall semester and exiting third-year students typically during the spring semester. The Finnish sample consisted of 2 402 students (1 538 entering and 864 exiting students) from the 2019-2020 academic year (Table 4.2).

PTs

For the PT, students are given an engaging, real-world scenario along with a set of documents such as research articles, newspaper and magazine articles, maps, graphs, and opinion pieces pertaining to the scenario. They are asked to make a decision or recommendation after analysing these documents and to write a response justifying their decision/recommendation by providing reasons and evidence both for their argument and against the opposing argument(s). There is no one correct answer for any PT. Rather, students are scored on how well they support and justify their decision with the information provided in the documents. No prior knowledge of any particular domain is necessary to do well, nor is there an interaction between the topic of the PT and the students’ field of study (Steedle and Bradley, 2012[25]).

The CLA+ scoring rubric (Chapter 2) for the PT has three subscores: Analysis and Problem Solving (APS), Writing Effectiveness (WE), and Writing Mechanics (WM).

The APS subscore measures students’ ability to interpret, analyse, and evaluate the quality of the information that is provided in the document library. This entails identifying information that is relevant to a problem, highlighting connected and conflicting information, detecting flaws in logic and questionable assumptions, and explaining why information is credible, unreliable, or limited. It also evaluates how well students consider and weigh information from discrete sources to make decisions, draw conclusions, or propose a course of action that logically follows from valid arguments, evidence, and examples. Students are also expected to consider the implications of their decisions and suggest additional research when appropriate.

The WE subscore evaluates how well students construct an organised and logically cohesive argument by providing elaboration on facts or ideas. For example, students can explain how evidence bears on the problem by providing examples from the documents and emphasising especially convincing evidence.

The WM subscore measures how well students follow the grammatical and writing conventions of the native language. This includes factors such as vocabulary, diction, punctuation, transitions, spelling, and phrasing.

Each student receives a raw score from 1-6 on each of the subscores, so, in this study, student total scores ranged from 3-18. If a student failed to respond to the task or gave a response that was off topic, a score of 0 (the equivalent of N/A) was given for all three subscores, and these student responses were eliminated from any subsequent analyses.

The rubric was also translated from English into Finnish. The scoring rubric was originally developed to be specific to each PT (Klein et al., 2007[26]; Shavelson, 2008[27]). However, this method of using unique rubrics for individual tasks created an issue with the standardisation, and thus validity, of the assessment. In 2008, a standardised version of the scoring rubric was introduced to address this threat to validity. The standardised version was designed to measure the underlying constructs assessed (i.e., analytic reasoning and evaluation, problem solving, writing effectiveness, and writing mechanics) that are applicable to all versions of the PT. This method of using a common rubric for PTs was found to be useful for improving students’ skills (with feedback) across multiple fields of study (Cargas, Williams and Rosenberg, 2017[28]).

In fact, having a common rubric for a performance-based assessment of domain-agnostic skills was one of the reasons the CLA was selected to be the anchor for the “generic skills strand” of the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) project, an international feasibility study sponsored by the OECD (AHELO, 2012[29]; 2014[30]; Tremblay, Lalancette and Roseveare, 2012[31]) to measure higher education students’ “generic” skills using PTs in a global context. The results from this feasibility study indicated that it was indeed possible to validly and reliably assess students’ critical thinking and written communication skills with a common, translated and culturally adapted PT and rubric (Zahner and Steedle, 2014[1]). This result was replicated in a subsequent international comparative study between American and Italian higher education students (Zahner and Ciolfi, 2018[2]).

SRQs

CLA+ includes a set of 25 SRQs that are also document-based and designed to measure the same construct as the APS subscore of the PT. Ten measure Data Literacy (DL) (e.g. making an inference); ten, critical reading and evaluation (CRE) (e.g. identifying assumptions); and five measure critiquing arguments (CA) (e.g. detecting logical fallacies). This section of the assessment was not analysed for this project as it was automatically machine-scored.

Translation and adaptation

CLA+ is translated and culturally adapted using the internationally accepted five-step translation process that is in compliance with International Test Commission (Bartram et al., 2018[32]) guidelines. The Council for Aid to Education (CAE) follows the guidelines used for the localisation process of major international studies such as PISA, Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), PIAAC, and AHELO. The process includes a translatability review, double translation and reconciliation, client review, focused verification, and cognitive labs.

During the translatability review, source material is reviewed to confirm that the text will adapt well to the native language and culture. Particular attention is paid to disambiguation of source, respecting key correspondences between stimuli and questions, and deciding what should or should not be adapted to local context. Two independent translators then review the text and provide translations. The translations are reconciled and sent to the lead project manager for review and an opportunity to provide minor suggestions. The translated CLA+ items are sent for a focused verification. Cognitive labs are then carried out with the assistance of participating institutions and the institutional teams to ensure the translation and adaptation process was effective.

The CLA+, including the rubric used in this study, was translated into Finnish and Swedish, which are the two main official languages of Finland. The adaptation and translation of both language versions of the task included several phases, as described above. Firstly, the test instruments were translated from English into the target language. Then, two translators (who had knowledge of English-speaking cultures but whose native language was the primary language of the target culture) independently checked and confirmed the translations. Subsequently, the research team in Finland reconciled and verified the revisions. The translations were then pretested in cognitive labs among 20 Finnish undergraduate students, with final modifications incorporated, as necessary. The use of cognitive labs with think-aloud protocols and interviews made it possible to ensure that the translation and adaptation process had not altered the meaning or difficulty of the task (Hyytinen et al., 2021[33]; Leighton, 2017[34]).

This case study only investigated a subset of Finnish student responses. Finnish was specifically selected due to its differences from English as well as the significantly larger number of student responses in Finnish compared to Finnish-Swedish.

CLA+ was administered online via a secure testing platform during an assigned testing window ranging from August 2019 into March 2020. In September 2019, a CAE measurement science team member went to Finland to conduct a two-day in-person scorer training. The first day consisted of an introduction to the PT, an overview of the online scoring interface, a thorough review of the PT and all of the associated documents, and a review of the scoring handbook, followed by initial scoring and calibration of the training papers. As part of scoring the calibration papers, each scorer independently scored a student’s response to the PT. Each scorer then shared their three subscores (APS, WE, and WM) with the group. The CAE colleague then revealed the CAE-verified score for the training paper. A discussion of the CAE score compared to the Finnish scores followed each paper. On the second day, the group completed the scoring of the preselected calibration papers as well as discussed a plan for completing the scoring process.

Following this in-person meeting, the two lead scorers in Finland double-scored the first batch of student responses and selected their calibration papers based on their agreement and the distribution of scores. Fifty calibration papers were selected to be inputted into the scoring queue in order to check for consistency of scoring. A scorer would receive one of these calibration papers every 15 or 20 responses. If they did not score within the appropriate range of the previously scored paper, they would enter into a separate training queue of more previously scored validity papers. If they failed again, they would need remediation, which is one-on-one consultation with the lead scorer. Following remediation, the scorer would once again need to pass a set of training papers before being allowed back into the scoring queue. Remediation occurred once for the Finnish scoring team. As a point of reference, the American scorers, in any given administration of this PT, require remediation an average of 1.7 times per semester, although the volume of student responses is much larger for the American scorers.

Once scoring commenced, there was an internal calibration meeting for the Finnish team as well as a meeting with CAE as many months had passed between the training and scoring.

Scoring equivalency case study

In order to assess the equivalency of scoring across countries, we sought to answer two research questions. The first was how well does a translated and culturally adapted performance-based assessment requiring students to generate a written response get scored across countries and languages? The second was whether equivalence can be established across the two forms of the assessment.

As part of this case study, two sets of scoring equivalency papers were selected and scored. Both sets were selected from a larger pool of responses that had perfect agreement between the initial two scorers in the system. Since mid-level scores were overrepresented in this reduced response pool, the final sample was selected by randomly selecting 1-4 responses from each score level.

Sample A consisted of 20 papers initially written in English that had previously been scored by American scorers. For this case study, these papers were scored by Finnish scorers who had mastery of the English language (Table 4.3). Sample B consisted of 20 papers that were initially written in Finnish and scored by Finnish scorers that were subsequently translated into English and scored by American scorers. In the translation of these Sample B papers from Finnish into American English, all the typos and other errors in the original student response were included as much as possible, given the differences between the two languages. These student responses were scored by American scorers.

For this equivalency case study, scorers from both countries who scored the cross-country responses were blind to the scores from the other pair of scorers. Scorer agreement within countries was examined by calculating correlations between scorers. The scoring equivalence data were analysed by comparing mean scores on common sets of translated responses across countries.

Scoring equivalency case study

This case study investigated whether PT results could be reliably scored in a standardised international testing environment. Analyses were conducted to investigate whether student responses received the same scores regardless of language or country. “Sameness” was examined in two ways: relative and absolute. The first refers to whether the relative standings of the responses were consistent (i.e. highly correlated) regardless of language or country. The second reflects whether the mean scores of the responses were equal.

Relative Quality of Scores: How well does a translated and culturally adapted performance-based assessment requiring students to generate a written response get scored across countries and languages?

To determine whether the scorers agreed with one another about the relative quality of the responses, correlation coefficients among pairs of scorers, both within and across countries, were calculated. The within-country analyses showed that student responses could be reliably scored within each country. The data presented in Table 4.4 and Table 4.5 show the inter-rater correlations for double-scoring U.S. students by U.S. scorers and Finnish students by Finnish scorers, respectively. These data are presented to show the results of the operational testing.

For the scoring equivalency case study, each student response was scored by a total of four scorers: two from the United States and two from Finland. As shown in Table 4.6, the inter-country correlations of the total scores, for two scorers, in each country were high, with r = .95 for Sample A and r = .93 for Sample B. The correlation of .95 indicates that the two Finnish scorers that scored the 20 U.S. PTs had a strong linear relationship. The correlation of .93 indicates that the two U.S. scorers that scored the 20 Finnish PTs that were translated into English also had a strong linear relationship.

Correlations between the two teams for the subscores were not as high as they were for total score, ranging from r = .88–.92 for Sample A and r = .89–.91 for Sample B (Table 4.7).

WM may need to be discussed in more detail because the Finnish scorers were not native English speakers and the Finnish papers that were back-translated into English may not have captured all of the language nuances of Finnish.

Absolute Quality of Scores: Can equivalency be established across the two forms of the assessment?

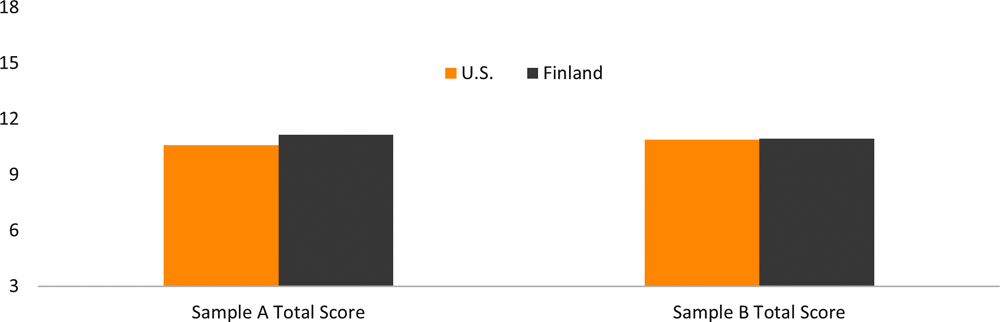

To determine whether the scorers agreed with one another on the absolute quality of the scores, the mean scores across countries were analysed. Figure 4.1 illustrates the mean total scores for each country for Sample A and Sample B.

There was no significant difference in the mean total scores for both sets of 20 papers in Sample A (t19 = -1.70; p = .11) and Sample B (t19 = -0.14; p = .89). The pattern of mean scores suggests that translating responses did not affect the perceived response quality or that there was no difference in scorer leniency across countries.

The individual subscores were also analysed. For Sample A (Figure 4.2), the difference between the two groups of scorers was not significant for APS and WE, but for WM, there was a significant difference between the two groups (MUSA = 3.55, MFin = 4.03; p = .004). One possible explanation is that the Finnish scorers, although familiar with American English, were scoring student responses in a language that was not their native language.

There were no significant differences in the average subscores across the two teams for Sample B (Figure 4.3), where the Finnish student responses were translated and culturally adapted into English. The observed difference in means for Sample A for WM was not seen in Sample B.

The results suggest that translated responses are scored the same as responses originally composed in the native language of the scorer.

This case study of scoring equivalency across languages and countries provides several findings of interest to international assessment programmes. The first is that scoring reliability within countries was high, indicating that scorer training was effective within each country participating in the case study (cf. (Borowiec and Castle, 2019[18]; Shavelson, Baxter and Gao, 1993[19]; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019[12]). Thus, students can be assessed on their higher order skills using an open-ended performance-based assessment within a given country. Similarly, when comparing results across countries, there were no notable between-country differences in the judgment of the absolute quality of the students’ PT responses.

The scores assigned to responses were highly consistent within a country (Table 4.4 and Table 4.5) as well as across countries (Table 4.6 and Table 4.7). The results indicate that with appropriate training and calibration, it is possible to achieve scoring reliability across countries.

A final finding from this case study is that it is feasible to develop, translate, administer, and score the responses to a computer-based, college-level, open-ended assessment of general knowledge, skills, and abilities that are applicable to many countries. Scores from an international testing programme can be calibrated to recognise relative response quality, as well as absolute response quality. The scores on such tests can provide valid and reliable data for large-scale international studies. Results from these types of assessments can be used in large-scale assessment programmes globally. With the increasing popularity of performance-based assessments and a global interest in critical thinking skills, it makes sense to further investigate international assessment of these skills.

Although the results indicate a high correlation between the two countries, there may be additional cultural variables that are not reflected in the results. The papers from the two countries were unique in some respects, leading the team to conclude that there is additional research into the cross-cultural context that needs to be explored (e.g., (Braun et al., 2020[17])).

Language-wise, the samples were not equal, which is often a necessity in a cross-cultural investigation, but it is also a limitation. Sample A (English) was scored by the Finnish team, who are not native speakers of English. While fluent, they are not familiar with all conventions of the English language. This was the probable cause in the difference between the team scores in WM in Sample A. Furthermore, Sample B (Finnish) comprised responses that were translated to English to enable the American team to score. Translated texts generally have been found to be different from original texts in terms of vocabulary and structural aspects (e.g., (Eskola, 2004[35])). However, no significant differences were found between the team scores in WM in Sample B. While it is clear that some of the errors in the responses were lost in translation, it is plausible that high correlation of different error types explained the agreement. In other words, errors that could be translated, such as typos, were strong indicators of other, more language-specific errors. More research is needed to understand if the international scoring rubric captures all characteristics of languages other than English (e.g., Finnish) in terms of WM.

Another limitation of this case study concerns the sample size. A rather small sample of students’ answers from only two countries was analysed. This may indicate the risk of potential bias in the results. In addition, the results may not be applicable to other cultures or languages.

Although the findings should be interpreted with caution, this case study provides new insights into PT scoring across two different countries and languages. The results can be utilised as a basis for more extensive empirical studies. In the future, we hope to complete the study by including additional countries in our analyses. Additionally, we hope to develop tools to help individual students identify and improve their areas of strength and opportunity. This can be accomplished through more detailed student and institutional reports that provide pathways to success as well as verified micro-credentials for essential university and workplace success skills such as those measured by CLA+.

This chapter and the research behind it would not have been possible without the support of the authors’ institutions, their colleagues, and the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. We would especially like to thank Tess Dawber, Kari Nissinen, Kelly Rotholz, Kaisa Silvennoinen, Auli Toom, and Zac Varieur.

References

[30] AHELO (2014), Testing student and university performance globally: OECD’s AHELO, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/edu/skills-beyond-school/testingstudentanduniversityperformancegloballyoecdsahelo.htm.

[29] AHELO (2012), AHELO feasibility study interim report, OECD.

[14] Attali, Y. (2014), “A Ranking Method for Evaluating Constructed Responses”, Educational and Psychological Measurement, Vol. 74/5, pp. 795-808, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164414527450.

[32] Bartram, D. et al. (2018), “ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (Second Edition)”, International Journal of Testing, Vol. 18/2, pp. 101-134, https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2017.1398166.

[7] Blömeke, S. et al. (2013), Modeling and measuring competencies in higher education: Tasks and challenges, Sense, Rotterdam, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-867-4.

[18] Borowiec, K. and C. Castle (2019), “Using rater cognition to improve generalizability of an assessment of scientific argumentation”, Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, Vol. 24/1, https://doi.org/10.7275/ey9d-p954.

[20] Braun, H. (2019), “Performance assessment and standardization in higher education: A problematic conjunction?”, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 89/3, pp. 429-440, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12274.

[17] Braun, H. et al. (2020), “Performance Assessment of Critical Thinking: Conceptualization, Design, and Implementation”, Frontiers in Education, Vol. 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00156.

[28] Cargas, S., S. Williams and M. Rosenberg (2017), “An approach to teaching critical thinking across disciplines using performance tasks with a common rubric”, Thinking Skills and Creativity, Vol. 26, pp. 24-37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.05.005.

[35] Eskola, S. (2004), “Untypical frequencies in translated language: A corpus-based study on a literary corpus of translated and non-translated Finnish”, in Translation universals: do they exist?.

[3] Geisinger, K. (1994), “Cross-Cultural Normative Assessment: Translation and Adaptation Issues Influencing the Normative Interpretation of Assessment Instruments”, Psychological Assessment, Vol. 6/4, p. 304, https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.304.

[4] Hambleton, R. (2004), “Issues, designs, and technical guidelines for adapting tests into multiple languages and cultures”, in Adapting Educational and Psychological Tests for Cross-Cultural Assessment, Lawrence Erlbaum, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410611758.

[13] Hyytinen, H. et al. (2015), “Problematising the equivalence of the test results of performance-based critical thinking tests for undergraduate students”, Studies in Educational Evaluation, Vol. 44, pp. 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.11.001.

[8] Hyytinen, H. and A. Toom (2019), “Developing a performance assessment task in the Finnish higher education context: Conceptual and empirical insights”, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 89/3, pp. 551-563, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12283.

[33] Hyytinen, H. et al. (2021), “The dynamic relationship between response processes and self-regulation in critical thinking assessments”, Studies in Educational Evaluation, Vol. 71, p. 101090, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101090.

[26] Klein, S. et al. (2007), “The collegiate learning assessment: Facts and fantasies”, Evaluation Review, Vol. 31/5, pp. 415-439, https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X07303318.

[34] Leighton, J. (2017), Using Think-Aloud Interviews and Cognitive Labs in Educational Research, Oxford University Press, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199372904.001.0001.

[22] Mauranen, A. (1993), “Cultural differences in academic discourse - problems of a linguistic and cultural minority”, in The Competent Intercultural Communicator: AFinLA Yearbook.

[10] McClelland, D. (1973), “Testing for competence rather than for “intelligence””, The American psychologist, Vol. 28/1, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034092.

[16] Popham, W. (2003), Test Better, Teach Better: The Instructional Role of Assessment, ASCD, https://www.ascd.org/books/test-better-teach-better?variant=102088E4.

[21] Sahlberg, P. (2011), “Introduction: Yes We Can (Learn from Each Other)”, in FINNISH LESSONS: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland?.

[9] Shavelson, R. (2010), Measuring college learning responsibly: Accountability in a new era, Stanford University Press, https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=16434.

[27] Shavelson, R. (2008), The collegiate learning assessment, Forum for the Future of Higher Education, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271429276_The_collegiate_learning_assessment.

[19] Shavelson, R., G. Baxter and X. Gao (1993), “Sampling Variability of Performance Assessments”, Journal of Educational Measurement, Vol. 30/3, pp. 215-232, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.1993.tb00424.x.

[11] Shavelson, R., O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and J. Mariño (2018), “International Performance Assessment of Learning in Higher Education (iPAL): Research and Development”, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_10.

[15] Solano-Flores, G. (2012), Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium: Translation accommodations framework for testing English language learners in mathematics, Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), https://portal.smarterbalanced.org/library/en/translation-accommodations-framework-for-testing-english-language-learners-in-mathematics.pdf.

[25] Steedle, J. and M. Bradley (2012), Majors matter: Differential performance on a test of general college outcomes [Paper presentation], Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, Canada.

[31] Tremblay, K., D. Lalancette and D. Roseveare (2012), “Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) Feasibility Study”, Feasibility study report, Vol. 1, https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/AHELOFSReportVolume1.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

[36] Tremblay, K., D. Lalancette and D. Roseveare (2012), Assessment of higher education learning outcomes feasibility study report: Design and implementation, OECD, Paris, http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/241317.

[24] Ursin, J. (2020), “Assessment in Higher Education (Finland)”, in Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350996489.0014.

[23] Ursin, J. et al. (2015), “Problematising the equivalence of the test results of performance-based critical thinking tests for undergraduate students”, Studies in Educational Evaluation, Vol. 44, pp. 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.11.001.

[37] Ursin, J. et al. (2021), Assessment of undergraduate students’ generic skills in Finland: Finding of the Kappas! Project (Report No. 2021: 31), Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture.

[5] Wolf, R., D. Zahner and R. Benjamin (2015), “Methodological challenges in international comparative post-secondary assessment programs: lessons learned and the road ahead”, Studies in Higher Education, Vol. 40/3, pp. 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1004239.

[2] Zahner, D. and A. Ciolfi (2018), “International Comparison of a Performance-Based Assessment in Higher Education”, in Olga Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. (eds.), Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Higher Education: Cross-National Comparisons and Perspectives, Springer, New York, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_11.

[1] Zahner, D. and J. Steedle (2014), Evaluating performance task scoring comparability in an international testing programme [Paper presentation], The 2014 National Council on Measurement in Education, Philadelphia, PA.

[6] Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., R. Shavelson and C. Kuhn (2015), “The international state of research on measurement of competency in higher education”, Studies in Higher Education, Vol. 40/3, pp. 393-411, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1004241.

[12] Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O. et al. (2019), “On the complementarity of holistic and analytic approaches to performance assessment scoring”, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 89/3, pp. 468-484, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12286.