3. Toward sound problem identification, policy formulation and design

This chapter identifies different management tools and policy instruments adopted by OECD Members to enhance the quality of problem identification, policy formulation and design. Practices presented in this chapter show that the following management tools can improve the quality of policy formulation and design: strategic planning, skills for developing policy, and digital capacities. This chapter also lays out how regulatory policy and budgetary governance can be used strategically to eschew governance failures during the policy formulation process. Regulatory policy and governance can help to ensure that regulations meet the desired objectives and new challenges as efficiently as possible and budgetary governance is an instrument to translate political commitment, goals and objectives into decisions on what policies receive financing and how these resources are generated.

The first step in sound policy-making is properly identifying a problem and designing the right response(s) to address it. Multiple factors influence the identification of policy challenges and their incorporation into the public agenda, including:

The capacity of representative institutions (for instance political parties, trade unions or trade associations) to articulate the challenge;

The media’s role in translating and communicating the challenge in a way that resonates with citizens;

The availability of data and evidence to enable the government to confirm that the issue is real and that it is in the government’s purview to address it;

Effective stakeholder-engagement that enables the government to launch and sustain dialogue with relevant civil-society actors and with citizens on the issue and on how to address it successfully; and

The capacity of the government to anticipate challenges through, for example, strategic foresight, horizon scanning and debates on alternative futures, including with civil society.

Chapters 1 and 2 of this Framework have highlighted governance practices that support open, equitable and evidence-informed problem identification as a way, inter alia, to avoid the capture of public policies by interest groups. Section 3.1.2 of this chapter also focuses on the importance of civil servants having the right analytical skills to define policy problems, notably to detect and understand their root causes.

Once an issue has been correctly identified, defined and framed, governments can determine adequate courses of action to solve the problem and/or implement a reform. . The policy formulation stage is the process by which governments translate long, medium and short-term policy goals into concrete courses of action.

The government is not a monolithic decision-maker, as such, the policy formulation process provides an opportunity for governments to collaborate with citizens, business and civil society organisations (CSOs), to innovate and deliver improved public service outcomes. Examples of co-production and co-decision-making range from referenda to consultation processes in which the course of action is developed and deliberated with a wide range of stakeholders and representative groups (OECD, 2011[44]). As explained in Chapter 2, engaging stakeholders can also constitutes a means to avoid policy capture during the policy-making process. This process can produce draft legislations, regulations, resource allocations or roadmaps and frameworks for future negotiations on more detailed plans. In an ideal setting, policy formulation therefore includes the identification, assessment, discussion and drafting of policy options to address societal needs and challenges.

One essential part of the formulation stage is the policy design, which deals with planning the implementation/enforcement, monitoring and evaluation stages. Ideally, based on a broad range of political and technical input, the government – and in particular, elected officials and senior management within it – will decide which tools and instruments they intend to use, and what financial and human resources they should allocate to implement and enforce a policy. Translating these visions and plans into achievable policies constitutes one of the greatest challenges in policy-making. Likewise, governments should consider evaluation mechanisms for new regulations and policies at the policy-formulation and design stage. Where relevant, specific regulations, such as sun-setting clauses should also be incorporated in the design of a policy. Decision makers usually have to choose among a wide array of options provided by an increasing range of policy advisors, from civil servants to such external actors as lobbying firms, private sector representatives, advisory or expert groups, NGOs, think tanks, academia, or political parties among others stakeholders. For instance, evidence shows that advisory bodies operating at arms' length from government are increasingly playing a role in policy-making and can constitute enablers for inclusive and sound policy-making (OECD, 2017[45]). The enablers outlined in Chapter 2 of this Framework emphasise the role that Centre of Government and institutional leadership play in driving the definition of strategic priorities and in leading the pursuit of medium term strategic planning to implement them.

Analysing and weighing the political, economic, social and environmental benefits and costs of different policy actions thus forms the core of the policy formulation phase. OECD evidence suggests that without a proper governance framework, public decisions and regulations are especially prone to be influenced or captured by special interests (CleanGovBiz, 2012[46]). Moreover, governance capacity failures such as limited financial, human and technological resources, or governance design failures such as the shortcomings of the institutional framework or inadequate regulations are a few of the numerous barriers to policy design that consequently hamper efficient policy implementation and service delivery

Having identified some of these barriers over the past decades, the OECD has pursued specific work in the governance of (1) management tools and (2) policy instruments that can enhance the quality of policy formulation and design:

Sections 3.1.1, 3.1.2 and 3.1.3 of this chapter focus on ways to bolster strategic planning, civil servants skills and digital capacities to improve policy formulation and design.

Section 3.2.1 lays out the way in which regulatory policy can be a strategic policy instrument to eschew governance design failures during the policy formulation process.

Section 3.2.2 of this chapter addresses the way in which budgetary governance can be used as a policy instrument to mitigate governance capacity shortcomings.

To ensure the effectiveness of, and support for, the course of action chosen by decision-makers, it is important that stakeholders perceive the policy action as valid, efficient and implementable. Thus, the policy formulation and design stage represents an opportunity for policymakers to ensure that practices associated with public governance values (chapter 1) are adopted, mainstreamed and integrated into the implementation process. In addition to the practices that will be highlighted in this chapter, successful practices and aspirations regarding mainstreaming of governance values are codified in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (2014) [OECD/LEGAL/0406], the amended OECD Recommendation on Promoting Good Institutional Practices for Policy Coherence for Development (2019) [OECD/LEGAL/0381] – which is under the responsibility of the Development Assistance Committee and in relation to which a revised Recommendation was developed in the Development Assistance Committee and Public Governance Committee - as well as the Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017) [OECD/LEGAL/0435], the Recommendation on Open Government (2017) [OECD/LEGAL/0438], and the Recommendation on Gender Equality in the Public Life (2015) [OECD/LEGAL/0418].

In the policy formulation and design stage, management tools constitute means to enhance public sector skills and capacity for policy design. They can serve as direct channels for policy implementation such as is the case of digital learning platforms. Some of the key management tools to improve the quality of policy design and therefore, shape policy outcomes are (1) strategic planning, (2) skills for developing policy, (3) digital capacities.

Strategic planning

A well-embedded planning practice can be instrumental in translating political commitments and ambitions into both long/medium-term strategies and operational action plans to guide the work of government. As such, strategic planning is a key management tool associated with enablers in sections 2.1 and 2.3 of this Framework. Strategic planning can be relevant to adjust domestic policies to match the multidisciplinary and complex nature of the 2030 agenda. When incorporating the Sustainable Development Goals to domestic plans, governments need to contend with their national realities and constraints as wells existing international commitments (OECD, 2019[47]). In this respect, lessons learned in country practice shows that:

Prioritisation should be an important part of the early stages of policy formulation, based on the problem-identification. Governments usually do not have resources to address all problems (simultaneously, at least). Prioritisation can lead to more realistic commitments and better-designed interventions which can help governments to develop more credible plans.

Planning needs to be systematic, ensuring alignment between various plans as well as between long-, medium- and short-term policy priorities towards a common goal

Strategic planning needs to ensure that policy instruments such as budgeting, regulations and workforce planning are oriented towards this strategy. Principle 2 of the OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance (2015[48]) [OECD/LEGAL/0410] aims to help policymakers use budget as a substantial policy instrument to achieve medium-term strategic priorities of the government, including those reflecting the SDGs.

Supreme Auditing Institutions can also play a critical role in designing a more strategic decision-making environment. Through their audit activities, these institutions are able to evaluate the adequacy of processes for long-term vision setting and for planning to transition goals into actions (OECD, 2016[18]).

Recent experiences in OECD Member countries show that when the planning process is open and includes stakeholder engagement, such as citizen-driven approaches through citizen participation mechanisms, strategic planning can enhance the legitimacy of policy-making and increase the sustainability of policies beyond the electoral cycle (OECD, 2016[23]).

On 19 February 2016, Norway adopted the Instructions for the Preparation of Central Government Measures (“Instructions for Official Studies”). The Instructions govern a broad range of central government measures and regulate, among other things, the timing of the policy development process, stakeholder coordination, impact analyses, public hearings and proposals for alternatives. The Instructions and associated guidelines aim to promote sound decision-making requirements for central government measures. This implies that the rationale for decisions is established prior to deciding which measure should be implemented.

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Government of Norway as part of the Policy Framework's consultation process

Skills for developing policy

Civil servants address problems of unprecedented complexity in increasingly pluralistic societies. In parallel, governance tools have evolved to be more digital, open and networked. The first challenge is therefore to identify which skills are needed for policy formulation and design, today and into the future. The OECD highlights a set of skills for a high-performing civil service: (1) skills for policy development, (2) skills for citizen engagement and service delivery, (3) skills for commissioning and contracting, and (4) skills for managing networks.

Skills for policy development are particularly important for the policy formulation stage. They combine traditional aptitudes, such as the capacity for providing evidence-based, balanced and objective advice while withstanding political and partisan pressure, with a new set of skills to meet expectations for digital, open and innovative government, technological transformations and the increasing complexity policy challenges The emphasis on evidence-informed decisions and innovation reflect the priorities established in sections 2.2 and 2.4 of this Framework. Policymakers need to know when and how to deploy institutional and administrative tools for policy formulation and design. Hence the importance of developing professional, strategic and innovation skills for:

Defining policy problems: civil servants need to be capable of detecting and understanding the root causes of policy challenges. This requires “analytical skills that can synthesise multiple disciplines and/or perspectives into a single narrative” (OECD, 2017[49]) including the capacity to interpret and integrate different and sometimes conflicting visions correctly, and to refocus and reframe policies. This also includes networking and digital skills to identify the right stakeholders and the right experts outside the civil service for engagement in policy formulation.

Designing Solutions: civil servants need the skills to understand potential future scenarios, and find resilient solutions to future challenges. These might include foresight skills and systems and design thinking to understand and influence the interactions among internal and external stakeholders and reconcile different sector expertise. They need to be able to identify and harness internal and external resources to facilitate the refining and implementation of the solution. They need to understand what has worked in the recent past and identify best practice that can be adapted to current problems.

Influencing the policy agenda: Senior civil servants and those working on policy development need the skills to understand the political environment and identify the right opportunities to move forward with policy initiatives and to advise politicians on options and trade-offs. Beyond the analysis of technocratic issues, civil servants therefore need to be able to take into consideration political and social values issues. This requires judgement skills to provide timely advice, recognise and manage risk and uncertainty, and design policy proposals in a way that responds to the political imperatives of the moment. Moreover, skills for communicating policy ideas, such as visual presentations and storytelling, can be central for the interaction with elected and politically-appointed decision-makers.

Once governments have identified the skills needed for policy formulation and design, the second challenge is to establish how governments can best invest in these skills to improve outcomes (see Box 3.2 for an example). The OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability (2019[9]) [OECD/LEGAL/0445] provides guidance to Adherents on how to invest in public service capability to develop an effective and trusted public service. This includes specific principles and guidance to:

Continuously identify skills and competencies needed to transform political vision into services which deliver value to society;

Attract and retain employees with the required skills and competencies;

Recruit, select and promote trough transparent, open and merit-based processes, to guarantee fair and equal treatment;

Develop the necessary skills and competencies by creating a learning culture and environment in the public service;

Assess, reward and recognise performance, talent and initiative.

The Framework for Client-Friendly Public Administration 2030 is a strategic document defining development of Czech public administration in the period 2021-2030. It highlights a number of measures to bolster skills for developing policy:

Implementation of evidence-informed decision-making in public administration - including specialised training of public officials responsible for analytical research and reports (strategic goal (SG) 3.1.1)

Establishment of Working group on cooperation of analytical units and establishment of analytical teams within the civil service - collaborative network and web platform for sharing the analytical data (SG 3.1.3, 3.1.4)

Development of skills to provide timely policy advice and analysis (SG 3.1.1)

In order to develop effective and trusted public service – implementation of training for front desk public officials with the aim of improvement of client-oriented communication and services; new tool for centralised civil servants´ training targeting common cross-sectional issues using e-learning (SG 1.1.5, 4.3.1)

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Government of the Czech Republic as part of the Policy Framework's consultation process

Digital capacities

In order to allow relevant stakeholders to collaborate actively with policymakers in the formulation of public policies, the government’s digital capacities are fundamental. The OECD Recommendation on Open Government (2017[22]) [OECD/LEGAL/0438] emphasises that new technologies and digital progress allow for a more participative and collaborative policy design process through more meaningful stakeholder engagement. Indeed, digital tools generate better access to information and therefore increase citizen participation in the formulation of public policies. This can contribute to obtain equitable decision-making, which is one of the enablers of sound policy-making in Section 2.2. of this Framework).

The digitalisation process of the court system in Latvia is exemplified by the launching of the court e-services portal manas.tiesas.lv, which is free of charge and allows the general public to track any court proceedings in any court of Latvia. This initiative aims to provide direct access to the courts through the use of technologies and improve information and service delivery to citizens and businesses.

Additionally, since 2018, Latvia has been in the process of creating a unified electronic proceedings system for the courts. It aims to reduce the length of proceedings and provide wider access to information. This initiative will include electronic data exchange between relevant institutions, access to case materials and electronic updates for participants, as well as statistical data in open data format.

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Government of Latvia as part of the Policy Framework’s consultation process; Tiesu Administracija; The court Administration Judicial System in Latvia https://www.ta.gov.lv/UserFiles/TA_buklets_ENG.pdf

The new digital environment enables and empowers rapidly evolving dynamics and relations between stakeholders to which the public sector has to rapidly adapt (OECD, 2014[31]). The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (2014[31]) [OECD/LEGAL/0406] stresses that new digital capacities also change expectations on government’s ability to deliver public value. As a result, governments are encouraged to integrate efficiency to other societal policy objectives in the governing of digital technologies. A sound digital government strategy therefore goes hand in hand with the enablers change management and innovation that are discussed in Section 2.4 of this Framework.

The Norwegian Government Agency for Financial Management launched the web-portal “statsregnskapet.no” (state public accounts) in October 2017. The portal provides up to date financial data for all ministries and central government agencies, searchable by budget chapter and standard chart of accounts. This resource provides a basis for cross-agency comparison and the analysis of resource consumption trends over time in an open data format.

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Government of Norway as part of the Policy Framework's consultation process.

However, often governments are not yet adequately equipped to make use of digital innovations and new technologies. Moreover, as described in Section 3.1.2 of the Framework, civil servants are often insufficiently trained to make use of new technologies. Digital progress and its impact on enhancing the capacity to guide or steer the policy process require governments to assess on a regular basis their digital capacities so that these can be adjusted to reflect the vagaries of a constantly changing digital environment. To this end, governments can secure political commitment to the digital government agenda, by promoting cross-ministerial collaboration and facilitating the co-ordination of relevant levels of government. Failures of government to make the transitions could incur serious security breaches and subsequent loss of citizen trust in public institutions. Digital Government Strategies should therefore reflect a risk management approach which addresses security and privacy concerns (OECD, 2014[31]).

The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (2014[31]) [OECD/LEGAL/0406] helps governments adopt more coherent and strategic approaches for “digital technologies use in all areas and at all levels of the administration” that stimulate more open, participatory and innovative administrations and that are aligned with governments’ own digital capacities. Digital tools alone do not guarantee success, developing strategies and standards for their use is therefore paramount. In order to develop and implement digital government strategies, the Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies suggests that governments:

Does your government have in place a robust multi-year strategic planning framework? Does this framework link strategic plans together and with the national budget?

Has your government undertaken specific measures to build civil service skills for policy formulation and design (e.g. through recruitment, promotion and training frameworks)?

Has your government established a legal or policy framework to facilitate the use of ICT as a mean to foster engagement and more participatory approaches in decision-making and the service design and delivery process?

Does your government evaluate the efficiency of its public procurement system?

During the problem-identification and policy-formulation phase policymakers not only have to decide what to do in setting the objectives they aim to achieve, they need to consider how best to address the problem by deliberating about costs and effects of proposed solutions. As part of this process, policymakers have to decide which substantial policy instruments can best be deployed to address a problem and implement a solution. Substantial policy instruments or tools are “the actual means or devices that governments make use of in implementing policies” (Howlett, Ramesh and Perl, 2009[42]). In the area of public governance, the OECD highlights the importance of the policy instruments of budgeting and rule-making to ensure that policies can meet the desired objectives and new challenges in as efficient as possible.

Regulatory policy and governance

A central policy instrument used by governments to intervene in economic matters and steer societal development are regulations. Policymakers can use regulation as an instrument, by imposing binding rules or limiting access to certain benefits and/or advantages directly or indirectly. When they are proportionate, targeted and smart they can improve social, economic and environmental conditions. When regulations are inadequate, consequences can be severe: non-implementable laws, frequent legislative chances, both of which undermine legal certainty and the business environment. To ensure regulations are not excessively burdensome, the OECD calls for governments to identify and revise public policies that unduly restrict competition by adopting more pro-competitive alternatives. The OECD Recommendation on Competition Assessment (2009[50]) [OECD/LEGAL/0376], under the responsibility of the OECD’s Competition Committee, encourages further governmental efforts to reduce unduly restrictive regulations and promote beneficial market activity

The 2008 global financial and economic crisis and its underlying failings in governance and regulation have shown the importance of regulatory policy as an instrument for sound policy-making. A “well-functioning national regulatory framework for transparent and efficient markets is central to re-injecting confidence and restoring [economic] growth” (OECD, 2012[27]) Moreover, sound regulations can eventually help policymakers meet fundamental social objectives in areas such as health, social welfare or public safety and represent an important instrument to master environmental challenges.

However, adopting the right regulations as an instrument to solve policy problems is a continuously demanding task. Policymakers have to evaluate if regulation is necessary and to what extent means other than regulatory instruments, such as awareness and communication campaigns, self-regulation or co-regulation, could be more effective and efficient to achieve policy objectives. To help governments implement and advance regulatory practice that meets stated public policy objectives, the Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD, 2012[27]) [OECD/LEGAL/0390]:

Provides governments with clear and timely guidance on the principles, mechanisms and institutions required to improve the design, enforcement and review of their regulatory framework to the highest standards;

Advises governments on the effective use of regulation to achieve better social, environmental and economic outcomes; and

Calls for a “whole-of-government” approach to regulatory reform, with an emphasis on the importance of consultation, co-ordination, communication and co-operation to address the challenges posed by the inter-connectedness of sectors and economies.

Being the first comprehensive international statement on regulatory policy since the financial crisis, the Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance advises policymakers on regulation design and quality during the policy formulation phase. The Recommendation highlights the importance of the public-governance values highlighted in Chapter 1 and in the OECD Recommendation on Open Government (2017[22]) [OECD/LEGAL/0438], including transparency and participation in the regulatory process “to ensure that regulation serves the public interest and is informed by the legitimate to needs of those interested in and affected by regulation”.

Transparency can positively add to the accountability of policymakers and increase citizens’ trust in the regulatory framework. The Recommendation on Open Government stresses the role of public consultations to engage stakeholders in all aspects of the policy-making process, including consideration and discussion about alternative options and the drafting process of regulatory proposals. Consultation and engagement eventually improve the transparency and quality of regulations through the collection of ideas, information and evidence from stakeholders regarding public policy-making. In turn, governments should be transparent about the way in which consultations influenced the process to support a lasting dialogue between external stakeholders and public authorities.

External consultation is a crucial element to prevent regulators from being subjected to one-sided influences, especially during the formulation phase and therefore to ensure that regulators act in the public interest and serve social cohesion. The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017[11]) [OECD/LEGAL/0435] further highlights the importance of levelling the playing field by granting all stakeholders – in particular, stakeholders with diverging interests – access in the development of public policies. This requires measures to ensure constructive stakeholder engagement in policy-making procedures, as well as instilling integrity and transparency in lobbying activities and political financing. Overall, transparency and stakeholder engagement (also important components of the OECD Recommendation on Open Government (2017) [OECD/LEGAL/0438], which is discussed in Section 1.2) can further reinforce trust in government, strengthen the inclusiveness of regulations and help to increase compliance with regulations by developing a sense of ownership

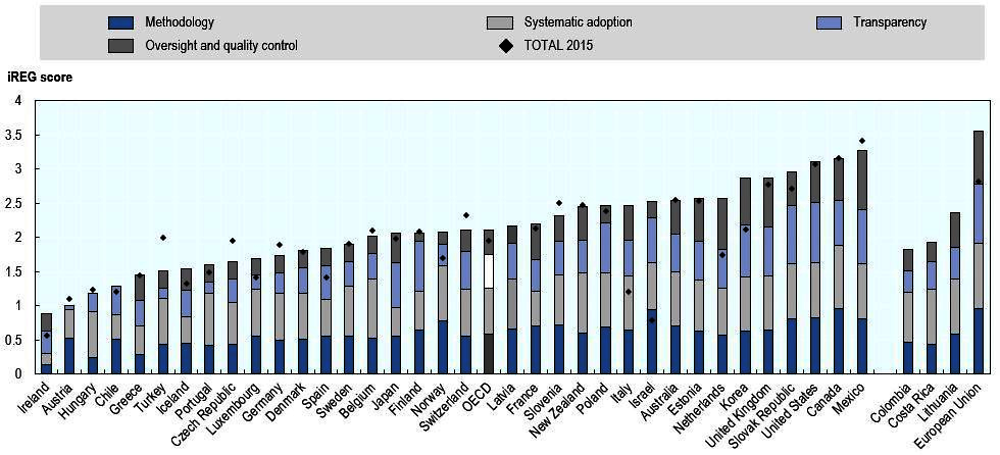

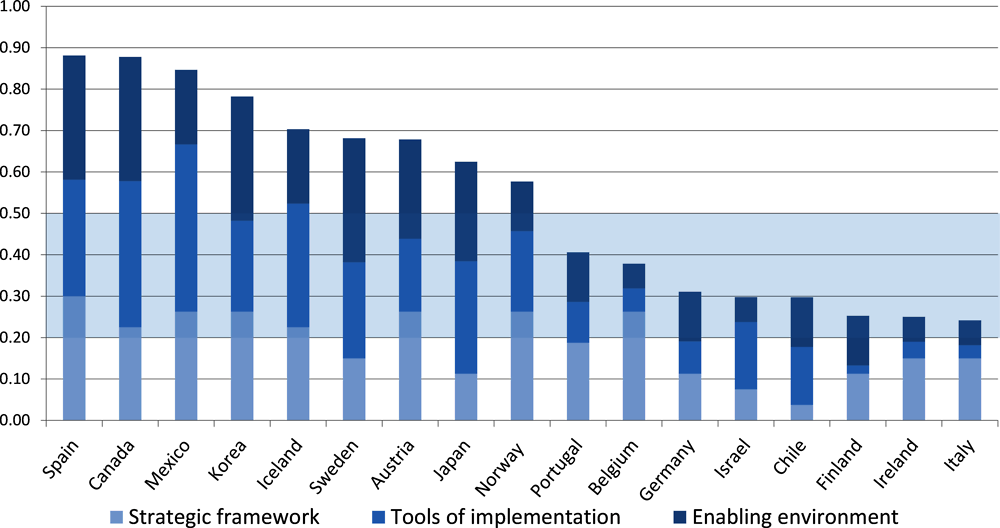

The majority of OECD Member countries have adopted stakeholder-engagement practices for the development of regulations. They use various forms of engagement, ranging from public online consultation to informal participation mechanisms. Countries with the highest scores of stakeholder-engagement in developing regulations have for instance adopted frameworks to open consultation processes to all parties interested and to disclose all stakeholder comments as well as government responses (see Figure 3.1).

In order to assess benefits, costs and effect of different regulatory and non-regulatory solutions during the policy formulation stage, ex-ante Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) offers policymakers a key instrument to promote the best response to specific policy problems. OECD experience has shown that conducting ex-ante RIA improves the governments’ capacity to regulate efficiently and enables policymakers to identify the policy solution that is most suitable to reach public policy goals. The OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (2012[27]) [OECD/LEGAL/0390] suggests governments “integrate Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) into the early stages of the policy process for the formulation of new regulatory proposals” and offers guidance for the design and implementation of assessment practices.

RIA can help increase policy coherence by revealing regulatory proposals’ trade-offs and identifying potential beneficiaries of regulations. In addition, RIA can also add to a more evidence-informed policy-making and help prevent regulatory failure due to unnecessary regulation, or lack of regulation when regulatory policy would be required. The collection of evidence through the RIA process can enhance the accountability of policy decisions at the formulation phase. Furthermore, external oversight and control bodies such as Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) can verify whether a coherent, evidence-based and reliable RIA accompanied the drafting of regulations (OECD, 2017[36]). The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017[11]) [OECD/LEGAL/0435] emphasises their crucial role in promoting accountable public decision-making.

All OECD Member countries have adopted formal requirements and developed methodologies for conducting RIA (OECD, 2018[52]). Ideally, RIA should not only assess the potential costs and benefits of regulatory proposals, but also try to determine any compliance and enforcement issues associated with a regulation.

The Securities and Exchange Commission in Italy (CONSOB) practiced the evaluation cycle by introducing regulation on equity crowdfunding. The process featured a mapping of burdens of implementing the regulation for various stakeholders as well as a qualitative analysis of the costs benefits analysis.

The report on Regulatory Impact Analysis activity published with the adaptation of the regulation in 2013, mentions the expected consequences of the regulation for different types of stakeholders. The report also contains a Regulatory Impact Assessment, which allows checking whether the objectives intended by legislators are actually achieved and estimating the costs and benefits, and contains a set of indicators for the ex-post cost and benefits analysis of the regulation. After the regulation took effect, CONSOB began monitoring based on data gathered for the quantification of the indicators and on the outcome of consultation procedures.

As a result of this evaluation, CONSOB defined an alternative intervention option. This consists in strengthening protections to effectively create a trustworthy environment for investors and minimise the burdens of all stakeholders involved. These stakeholders are those capable of maximizing the cost/benefit ratio, encouraging informed investment and fostering the provision of high standards of service by portals. The revised regulation’s expected benefits and costs were shown in a subsequent consultation.

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Government of Italy as part of the Policy Framework's consultation process

Budgetary Governance

Another policy instrument for sound public governance is budgeting. The budget reflects a government’s policy priorities and translates political commitments, goals and objectives into decisions on the financial resources allocated to pursue them, and on how these financial resources are to be generated. It enables the government to establish spending priorities related to the pursuit of its strategic objectives and to proceed with a sequencing of initiatives that takes into account the availability of financial resources as defined in the fiscal framework. As mentioned above in section 3.1.1, governments are more systematically aligning planning priorities with spending priorities by ensuring greater linkages between planning and budgeting. This is particularly the case when governments pursue Performance-Based budgeting (see Box 3.6 on Estonia’s efforts in this regard). In conjunction with strategic planning, budgetary governance can improve the extent to which resource allocation promotes the design of policies in support of national Sustainable Development Goals., and ensure the continuity of these policy objectives beyond electoral cycles (OECD, 2019[47]). Fiscal councils, parliamentary budget offices or Supreme Auditing Institutions can fulfil this purpose, by providing oversight to budgetary debates for instance or ensuring the underlying assumptions of the budget are sound. Additionally, effective public internal control and a risk management approach are paramount to ensure states develop efficient policies in a legal, ethical and financially appropriate manner.

Estonia is currently transitioning towards performance-based budgeting. In May 2019, the Government approved Estonia’s first performance-based State Budget Strategy 2020-2023 and State Budget for 2020. The transition to an output-based approach requires ministries to reduce the number of programmes’ objectives and link these to performance indicators. These reforms aim to achieve more effective and efficient public services, and improve budgetary decision-making.

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Government of Estonia as part of the Policy Framework's consultation process

Through budget allocation, policymakers can strategically encourage or discourage particular courses of action. Government spending can, for instance, influence the provision of services or infrastructure in case of market imperfections or failure in areas such as public health or environment protection and serve as leverage to encourage private investment and innovation (Box 3.7). Moreover, public expenditure can positively contribute to spatial, social and economic cohesion. Through the use of fiscal instruments, such as taxes, tariffs, duties and charges, policymakers can also help discourage certain economic or private behaviours.

Poor infrastructure governance is one of the most common bottlenecks to achieving long-term development. It affects not only the capacity of the public sector to deliver quality infrastructure but also has a negative impact on investment by the private sector. Good governance promotes value for money and allows financing to flow, poor governance generates waste and discourages investment.

The OECD Framework for the Governance of Infrastructure has been recognised by national governments and other international organisations as the main policy framework to ensure countries invest in the right projects, in a way that is cost effective, affordable and trusted by investors, users and citizens. After 5 years of implementation, it is proposed to update the Framework and, in the process, embody it in an OECD Recommendation. The Framework is designed to help governments improve their management of infrastructure policy from strategic planning all the way to project level delivery. It is built around ten key dimensions across the governance cycle of infrastructure, including determining a long-term national strategic vision for infrastructure; integration of infrastructure policy with other government priorities; co-ordination mechanisms for infrastructure policy within and across levels of government; stakeholder engagement and consultation. It furthermore looks at procedures to monitor performance of the asset throughout its life and measures needed to safeguard integrity at each phase of infrastructure projects; as well as the procedures used to ensure feasibility, affordability and cost efficiency; and under which conditions projects with private participation can lead to better outcomes.

Source: OECD (2017[56]) Getting Infrastructure Right: a Framework for Better Governance.

Along with effective expenditure management, tax policy and tax administration reform can be a crucial starting point to improve state capacity and launch needed reforms (OECD, 2013[55]). Moreover, taxation often elicits demands for more responsiveness and accountability coupled with better management of expenditures. Conversely, reliance on taxes creates incentives for governments to be more receptive to demands from the public. However, tax policy must strike a difficult balance between securing revenues without constraining innovation, productivity, and inclusive economic growth. The OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration supports the Committee on Fiscal Affairs and its bodies to assist countries in devising sound tax policies and tax administration reforms. For instance, the Global Revenue Statistics Database provides the largest public source of comparable tax revenue data and strengthens governments’ capacity to develop and implement tax policy reforms. Additionally, the OECD's Tax Administration Series provides internationally comparative data on aspects of tax systems and their administration in 58 advanced and emerging economies.

A budget oriented towards inclusiveness, can encourage the adoption of more inclusive policies during the policy formulation phase. Adopting a gender perspective with regard to budget decisions, by making use of special processes and analytical tools can help to promote gender-responsive policies that address existing gender inequalities and disparities. The 2018 OECD Budget Practices and Procedures Survey has shown that nearly half the OECD Member countries (17 countries) had already introduced and adopted gender mainstreaming in the budget process (OECD, 2018[53]).

Reflecting environmental considerations in budget documents and fiscal frameworks, including the annual budget, can help governments to ensure financing and implementation of policies to attain their environmental objectives. By ensuring that national expenditure and revenue processes are aligned with goals on climate and environmental policies, governments can, moreover, increase the accountability of their commitments and move towards environmentally sustainable development as stipulated by the Paris Agreement on climate change and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Budgetary governance is crucial to help governments navigate trade-offs between different goals, for instance between industrial growth and biodiversity (OECD, 2019[47]).

Given its central importance for public governance and policy-making, the OECD has developed the OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance (2015[48]) [OECD/LEGAL/0410], which focuses on “the processes, laws, structures and institutions in place for ensuring that the budgeting system meets its objectives in an effective, sustainable and enduring manner” (OECD, 2015[48]).

Providing a concise overview of good budgetary practices, the Recommendation on Budgetary Governance contains ten principles that can serve as guidance for policymakers to make use of the budget system to achieve policy objectives and meet the challenges of the future. In addition to the aforementioned principle 2 (on linking budgeting with national priorities, in line with Section 2.1 of the framework), three principles are of particular importance for the policy formulation phase:

Principle 3 calls upon governments to design the capital budgeting framework in a way that it supports meeting national development needs in a cost-effective and coherent manner. How governments prioritise, plan, budget, deliver, regulate and evaluate their capital investment is essential to ensure that infrastructure projects meet their timeframe, budget, and service delivery objectives.

Principle 4 points to the importance of ensuring that budget documents and data are open, transparent and accessible, reflecting the value of openness highlighted in Chapter 1 of the framework. Only with clear, factual budget reports that inform the stage of policy formulation, policymakers can take sufficiently informed budget decision to address policy problems. All budget information should further be presented in comparable format to discuss policy choices with citizens, civil society and other stakeholders to promote effective decision-making and accountability.

Principle 5 recommends policy-makers to provide for an inclusive, participative and realistic debate on budgetary choices that need to be made in the general public interest. Engagement with parliaments, citizens and civil society organisations in a realistic debate about key priorities, trade-offs, opportunity costs and value for money can increase the quality of budgetary decisions. But public engagement also requires the provision of clarity about relative costs and benefits of the public expenditure programmes and tax expenditures. The provision of citizen-friendly, accessible budget reports is also key to increase citizen interest in budgetary governance.

Value for Money Unit in Slovakia

The Value for Money (VfM) unit of the Slovakian Ministry of Finance cooperates with other analytical units across various ministries to identify unnecessary public expenditures of the government. For instance, any investment exceeding 40 million Euros must undergo a cost-benefit analysis carried out by the Value For Money Unit. The Government Office (the CoG unit in the Slovakian Government) has created an Implementation Unit to assess whether or not VfM unit recommendations are carried out.

Microsimulation of taxes and social contributions in Poland

Poland’s Ministry of Finance has built a microsimulation model to estimate the fiscal costs of policy proposals in the areas of personal income tax and social security contributions. The model is based on individual data from tax returns and the Social Security fund. It is applied to estimate the fiscal costs of changes in personal income tax, social security contributions and health insurance contributions. Advanced modelling tools based on administrative individual data provide a useful assessment of policy interventions and therefore generate evidence-based policy.

Source: Example of country practice provided by the Governments of Slovakia and Poland as part of the Policy Framework's consultation process

Has the government established policies, institutions and tools to ensure the quality and coherence of regulatory policy (e.g. the design, oversight and enforcement of rules in all sectors)?

Has the government established institutions and tools to ensure the involvement of stakeholders in the policy formulation process (with informing affected parties about the policy intentions and embedding an interactive dialogue with stakeholders in the process)?

To what extent are regulatory impact assessments used to evaluate the wider impacts and consequences of regulations, including on the competition, SMA and investment climate?

Does your government ensure the alignment of the annual budget, its multi-year budget frameworks as well as its capital-expenditure planning with strategic policy objectives, such as national development plans or the SDGs?

Has your government established mechanisms to facilitate or promote budget transparency and to discuss the budget with stakeholders such as citizens and civil society organisations during the budget-setting process?

Has your government implemented - or is planning to implement - specific policies for the development of a gender perspective on budget decisions?

Has your government implemented – or is planning to implement – specific policies to reflect environmental considerations in the budget documents and fiscal frameworks?

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability (2019) [OECD/LEGAL/0445]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (2017) [OECD/LEGAL/0438]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (2014) [OECD/LEGAL/0406]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance (2012) [OECD/LEGAL/0390]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Development (2019) [OECD/LEGAL/0381]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity (2017) [OECD/LEGAL/0435]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance (2015) [OECD/LEGAL/0410]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance (2012) [OECD/LEGAL/0390]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Competition Assessment (2009) [OECD/LEGAL/0376]

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Improving the Quality of Government Regulation (1995) [OECD/LEGAL/0278]

OECD Public Governance Review: Skills for a High Performing Civil Service (2017)

OECD Best Practice Principles on Stakeholder Engagement in Regulatory Policy (forthcoming)

OECD CleanGovBiz Toolkit “Regulatory Policy: Improving Governance” (2012)

OECD Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing (2016)

OECD Principles for Public Governance of Public-Private Partnerships (2012)

OECD Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing Gender Equality (2015)

OECD Tax Administration 2019: Comparative information on OECD and other Advanced and Emerging Economies (2019)

References

[46] CleanGovBiz (2012), Regulatory policy: improving governance, http://www.cleangovbiz.org (accessed on 4 October 2019).

[42] Howlett, M., M. Ramesh and A. Perl (2009), Studying Public Policy, Oxford University Press.

[47] OECD (2019), Governance as an SDG Accelerator : Country Experiences and Tools, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0666b085-en.

[9] OECD (2019), Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability.

[52] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[53] OECD (2018), OECD Budget Practices and Procedures Survey, Questions 32 and 36, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[56] OECD (2017), Getting Infrastructure Right: A framework for better governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264272453-en.

[11] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity.

[22] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government.

[49] OECD (2017), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[45] OECD (2017), Policy Advisory Systems: Supporting Good Governance and Sound Public Decision Making, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264283664-en.

[23] OECD (2016), Open Government:The global context and the way forward, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[18] OECD (2016), Supreme Audit Institutions and Good Governance: Oversight, Insight and Foresight, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264263871-en.

[57] OECD (2016), Survey on Gender Budgeting, OECD.

[48] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance.

[31] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies.

[55] OECD (2013), “Taxation and governance”, in Tax and Development: Aid Modalities for Strengthening Tax Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264177581-6-en.

[27] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance.

[44] OECD (2011), Together for Better Public Services: Partnering with Citizens and Civil Society, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264118843-en.

[50] OECD (2009), Recommendation of the Council on Competition Assessment.

[51] OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/indicators-regulatory-policy-and-governance.htm (accessed on 7 October 2019).