copy the linklink copied!3. Policy recommendations and actions for a circular economy in Umeå, Sweden

In response to the challenges identified in Chapter 2, this chapter suggests some policy recommendations to implement a circular economy in the city of Umeå, Sweden. The policy recommendations are accompanied by a list of actions for concrete implementation, accordingly to international practices.

copy the linklink copied!Introduction

A total of 18 recommendations have been identified accordingly to the role of the city as promoter, facilitator and enabler of the circular economy (Table 3.1). These recommendations are accompanied by a set of actions aiming at supporting Umeå’s transition to a circular economy. The proposed actions are indicative and based on international practices while taking into account the local context. These international practices carried out in the field of the circular economy by cities, regions and national governments can serve as inspiration for the implementation of the recommendations. As such, they are not expected to be replicated in Umeå but rather provide the municipality with a set of examples for the development and implementation of the suggested actions.

It is important to note that:

-

Actions are neither compulsory nor binding: Identified actions address a variety of ways to implement and achieve objectives. However, they are neither compulsory nor binding. They represent suggestions, for which adequacy and feasibility should be carefully evaluated by the municipality of Umeå in an inclusive manner, involving stakeholders as appropriate. In turn, the combination of more than one action can be explored, if necessary.

-

Prioritisation of actions should be considered: Taking into account the unfeasibility of addressing all recommendations at the same time, prioritisation is key. As such, steps taken towards a circular transition should be progressive.

-

Resources for implementation should be assessed: The implementation of actions will require human, technical and financial resources. When prioritising and assessing the adequacy and feasibility of the suggested actions, the resources needed to put them in practice should be carefully evaluated, as well as the role of stakeholders that can contribute to the implementation phase.

-

The proposed actions should be updated in the future: New potential steps and objectives may emerge as actions start to be implemented.

-

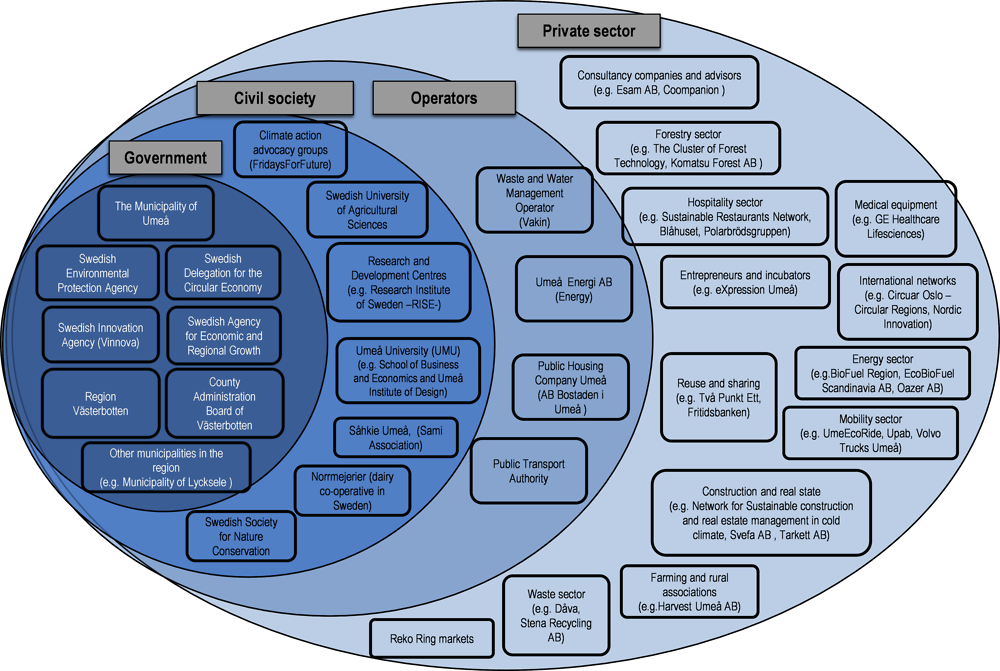

Several stakeholders should contribute to their implementation: Policy recommendations and related actions should be implemented as a shared responsibility across a wide range of actors. The stakeholder groups contributing to this report and to the identification of the actions are represented in Figure 3.1. They have a key role as “do-ers” of the circular economy system in Umeå, Sweden, along with other stakeholders that will be engaged in the future.

The city of Umeå can play a role as promoter, facilitator and enabler of the circular economy strategy. Cities act as promoters when they identify priorities, promote concrete projects and engage stakeholders; they are facilitators when fostering co-operation between stakeholders, citizens and levels of government. The city’s enabler role entails setting the necessary conditions for the circular economy (e.g. updating regulatory frameworks, catalysing funds, etc.). In order to boost the circular economy in Umeå, the municipality could implement the recommendations detailed in this section.

copy the linklink copied! Promoting a vision and a strategy for the circular economy

The city of Umeå can promote the circular economy, building on a strong political willingness and the existence of a dynamic business community. In order to boost the circular economy in Umeå, the municipality could implement the recommendations detailed in this section.

Map the existing circular initiatives

There are several circular-related initiatives in various sectors, from food to transport or construction. Mapping them would allow the city to: i) obtain deeper understanding of circular economy-related initiatives; ii) identify those sectors where circular initiatives are taking place at all stakeholder levels, as well as the gaps; iii) learn from success and failure; iv) develop an understanding of what the circular transition means for each sector; and v) explore potential cross-sector synergies and their common features. Some examples of mapping circular initiatives include: the city of Austin (United States) that created a directory of businesses that allows customers to participate in the circular economy (Austin's Circular Economy Story, 2020[1]). In the region of Flanders (Belgium), Circular Flanders is mapping the range of financing instruments available for the circular economy (OVAM, 2019[2]). Circular Oslo – Circular Regions applies a multi-stakeholder methodology and technology to map circular initiatives and identify environmental, economic and social impact. This methodology will be replicated within the Circular Regions Network and the data collected will be open source (Circular Oslo-Circular Regions, 2020[3]).

Key actions

-

Collect information on existing circular economy-related initiatives, such as projects, programmes, plans and roadmaps in various sectors (e.g. food, waste, water, transport, etc.), which implement, for example:

-

Regenerative design.

-

Sustainable production practices based on minimising raw material extraction.

-

Short mile distribution practices.

-

Sustainable consumption patterns aiming at minimising waste production.

-

-

Identify the stakeholders involved in these activities and possible linkages amongst them.

-

Identify both urban and rural initiatives enabling regional collaborations and the replication of best practices for scaling impacts.

-

Explore different ways to conduct the mapping, for example through:

-

An online platform to upload initiatives and projects in the field of the circular economy. This could take the form of an open-source database to be able to research any aspects from the circular initiatives (e.g. sectors, yeas, actors involved, etc.). A communication campaign to reach out to all stakeholders might be needed.

-

Offline platforms, gathering input from stakeholders through regular meetings, surveys, interviews and public consultations.

-

-

Continuously monitor circular economy events/seminars organised in the city.

-

Update and share the information collected through the mapping process.

Perform a urban metabolism analysis

Mapping material and energy flows within the municipality can help improve the planning and decision-making process for better use of resources and more efficient logistics. This is an opportunity to involve the universities and connect them with the territory and the circular economy. The city of Paris (France) and the city of Rotterdam (Netherlands) are cases where local authorities have conducted a metabolism analysis, identifying priority flows that highly impact the metabolism of the city and insights for the future sustainable design of the city (Circular Metabolism, 2017[4]; Municipality of Rotterdam, 2013[5]).

Key actions

-

Collaborate with universities and research and development (R&D) centres to carry out an urban metabolism study.

-

Evaluate the scale of the analysis at the metropolitan and regional levels, with the collaboration of competent authorities.

-

Identify concrete follow-up actions to reduce resource consumption and negative output, such as pollution. In the case of water, materials, energy, for example, digital solutions can be applied (e.g. water meters, mobile data applications for mobility solutions, applications for energy saving), in addition to appropriate policies.

-

Communicate and distribute the results of the metabolism flow analysis (e.g. through public exhibitions).

-

Conduct the metabolism flow analysis regularly (e.g. once a year or biannually), in addition to updating regularly environmental and climatic studies.

Link the circular economy with existing long-term plans

Synergies across climate adaptation policies and plans, mobility, land use and service provision could benefit from the implementation of circular economy principles, whereby resources are used at their foremost and waste minimised. Having a general overview of all the circular economy-related plans, strategies, policies and programmes could foster coherence across all the sectors and synergies across responsible bodies. For example, Sweden’s Rural Policy incorporates the circular economy in one of its four objectives (Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, 2015[6]).

Key actions

-

Identify existing initiatives and targets that can be achieved through a circular economy.

-

Identify synergies across existing and future initiatives in Umeå on climate change, rural policies, land use, waste management amongst others and their respective targets that can be achieved through applying circular economy principles, such as:

-

Reduction of extractive material.

-

Extension of the use and life cycle of products and materials.

-

Regeneration of natural systems.

-

-

Contact project officers of existing initiatives to identify links with the circular economy.

-

Organise workshops and ad hoc meetings to align interest across the different initiatives.

-

Link the circular economy with available indicators from other existing initiatives.

-

Identify potential overlaps between existing initiatives and a potential circular economy strategy.

Develop a strategy on the circular economy

Common objectives and a strong narrative on the circular economy strategy could help co-ordinate existing initiatives. The vision could take the form of a strategy. In this case, clear and shared objectives, targets and budget should be defined. The strategy could benefit from stakeholder engagement from phase zero. For example, designers, among others, could help frame the type of upstream activities needed to prevent waste production and increase the durability of products, goods and services. Once developed, measurable targets should be linked to objectives. Examples of measurement frameworks for a circular economy applied at the city level include: Measuring the Circular Economy Developing: An Indicator Set for Opportunity Peterborough (Morley, Looi and Zhao, 2018[7]), Indicators for a Circular Economy (Vercalsteren, Christis and Van Hoof, 2018[8]), and the Circular Economy Framework Monitoring Report, Greater Porto Area, Portugal (LIPOR, 2019[9]). There are several examples of cities and regions that have developed a circular vision and that could serve as inspiration for Umeå in the design and implementation of its strategy, such as those listed in Table 3.2.

Key actions

Engage stakeholders:

-

Engage key stakeholders to co-design a shared circular economy vision that reflects their needs and concerns (OECD, 2015[11]):

-

Map all stakeholders that have a stake in the outcome or are likely to be affected, as well as their responsibility, core motivations and interactions.

-

Define the ultimate line of decision-making, the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of input.

-

Use stakeholder engagement techniques, ensuring the effective representation of all stakeholders in the process.

-

Allocate proper financial and human resources and share needed information for result-oriented stakeholder engagement.

-

Regularly assess the process and outcomes of stakeholder engagement to learn, adjust and improve accordingly.

-

Embed engagement processes in clear legal and policy frameworks, organisational structures/principles and responsible authorities.

-

Customise the type and level of engagement to the needs and keeping the process flexible to changing circumstances.

-

Clarify how the inputs will be used.

-

Communicate clearly on the responsibility of each actor in the municipality.

-

-

Organising communication campaigns and activities in the city to raise awareness among stakeholders on the circular economy’s objectives and benefits and how citizens can contribute.

-

Creating participation spaces for citizens and stakeholders throughout the different implementation phases of the circular economy strategy. Instruments that can be used to share the ownership of the circular economy transition with stakeholders include:

-

Multi-stakeholder fora.

-

Workshops.

-

Breakfast meetings on the circular economy.

-

Co-creation methodologies.

-

Feedback loops.

-

Define goals and actions

-

Define result-oriented and realistic objectives, and ensure that they are coherent with the national and regional levels.

-

Define short-, medium- and long-term targets and sub-targets for the circular strategy (e.g. quantity of circular economy-related projects, number of circular buildings to be constructed, etc.).

-

Align the objectives of the circular economy strategy with the goals of existing policies (e.g. energy transition, climate change, smart city and urban planning).

-

Identify key sectors (e.g. urban regeneration, tourism, construction, waste, etc.) that could generate relevant economic, environmental and social impacts, establish priorities and possible partners.

-

Identify activities that can be relevant in shifting from a linear to a circular system (e.g. eco-design, services rather than ownership).

-

Design a set of actions to implement the defined objectives, set their expected outcomes and allocate a budget and (human and technical) resources to each of the actions.

Develop a financial plan

-

Design a set of actions for the achievement of objectives, define their expected outcomes and allocate a budget and resources to each of the actions.

-

Develop a financial plan for the implementation of the strategy

-

Identify and communicate the costs (environmental, social and opportunity costs) and benefits of circular activities compared to linear approaches (baseline scenario or no action taken).

Monitoring, evaluation and communication

-

Regularly monitor the progress of the strategy’s implementation; evaluate its impacts to make improvements and communicate the results to the public. The indicators proposed in by the OECD (forthcoming[10]) can be taken into account:

Setting the strategy

-

No. of public administrations/departments involved in the design of the circular economy imitative.

-

No. of actions identified to achieve the objectives.

-

No. of circular economy projects to implement the actions.

-

No. of staff employed for the circular economy initiative’s design within the city/region/administration.

-

No. of stakeholders involved to co-create the circular economy imitative.

-

No. of projects financed by the city/regional government/Total number of projects.

-

No. of projects financed by the private sectors/Total number of projects.

Implementing the strategy

-

Waste diverted from landfill (T/inhabitant/year or %).

-

CO2 emission avoided (T CO2/capita or %).

-

Raw material avoided (T/inhabitant/year or %).

-

Use of recovered material (T/inhabitant/year or %).

-

Energy savings (Kgoe/inhabitant/year or %).

-

Water savings (ML/inhabitant/year or %).

-

Promote circular economy practices, through guidelines for specific sectors

There is a growing interest among entrepreneurs from different sectors on the transition from the linear to the circular economy. This is the case of the construction, food and waste sectors, for example. However, it is often the case that regulation, economic and financial instruments, as well as data are unknown or uncertain. The municipality could clarify, through guidelines for several sectors, the opportunities and practicalities that could help promote the transition. Designing these guidelines may help identify those sectors with a higher impact on the circular economy.

Key actions

-

Based on the mapping of circular economy-related initiatives (as above), develop guidelines for specific sectors to share with entrepreneurs and other actors. For example, guidelines for each sector could foresee information on existing regulation, spaces for experimentation, incentives, certifications, economic instruments, fiscal tools, etc.

-

Organise networking events/fora to foster collaboration and exchange of good practices among companies from the same sector.

Map future jobs and skills

There are two kinds of major issues related to jobs in Umeå: first, besides the presence of renowned universities, students leave the city after completing their studies for more appealing job opportunities, mainly in the capital. Second, while there is a demand for low-skilled jobs, there is not enough workforce to meet it. Mapping job opportunities for the circular economy would help match supply and demand in the job market of the city and its surrounding areas. This exercise would provide the municipality with an overview of the future employment situation and identify the most vulnerable sectors. Some international experiences are the following: the city of Paris (France) has already conducted research on the current levels of circular economy jobs at the local level (City of Paris, 2019[12]); the city of Toronto (Canada), measures the social impact of the circular economy through three indicators: the number of green jobs created, the number of city staff trained in GPP and asset/sharing utilisation activities (OECD, 2019[13]). Furthermore, Amsterdam (Netherlands) and London (United Kingdom) are good examples of cities undertaking efforts to identify jobs related to the circular economy:

-

In 2015, the London Waste and Recycling Board (LWARB) published the study Employment and the Circular Economy – Job Creation Through Resource Efficiency, which counted 46 700 jobs in circular economy activities in 2013 (2015[14]). The report forecasts the number of net circular jobs that could be created in the city by 2030, accordingly to the level of job specialisation. The study clusters the following levels depending on the needed skills:

-

High skilled occupations are defined as managers, directors and senior officials; professional occupations; and associate professional and technical positions.

-

Medium skilled jobs are identified as administrative and secretarial roles; skilled trade occupations; and process, plant and machine operatives.

-

Low-skilled positions are associated with sales and customer services and elementary occupations.

-

-

The Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (AMA), Netherlands, has published the Circular Jobs & Skills in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area report, which identifies 140 000 circular jobs (Circle Economy/EHERO, 2018[15]). The study identifies six groups of skills relevant to future circular jobs: basic skills (capacities that facilitate acquiring new knowledge); complex problem solving (abilities to solve new, complex problems in real-world settings); resource management skills (capacities for efficient resource allocation); social skills (abilities to work with people towards achieving common goals); systems skills (capacities to understand, evaluate and enhance “sociotechnical systems”); and technical skills (competencies to design, arrange, use and repair machines and technological systems).

Key actions

-

Carry out specific studies and research aimed at detecting future job opportunities in the city, for example, jobs in rental, repair, industrial and regenerative design, digital innovation, education, professional services, etc.

-

Distinguish jobs by type of skills required, for example from basic to high skills (low wage job category to managerial positions) or accordingly to the skills specifically required (e.g. technical, social, etc.).

Promote circular businesses through labels, certifications and awards

The municipality could consider introducing a label for circular activities located in Umeå, whether for food (e.g. restaurants), construction or other sectors. The introduction of these labels could be a means to incentivise businesses to produce according to circular economy principles while providing consumers with information to make conscious consumption choices. Criteria for labelling could be formulated following detailed studies by universities and research centres. Awards can also incentivise businesses, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society to contribute to the transition to a circular economy. Several examples are illustrated in Box 3.1.

Key actions

-

Consider developing a local label or certification for products, initiatives or organisations that are implementing circular practices in Umeå, defining common guidelines for circular economy products and processes at a local level.

-

Collaborate with local universities and research centres to analyse the criteria for circular labels or certifications.

-

Select sectors in order to undertake pilot experiments on circular labels and/or certificates.

-

Engage a dialogue with the private sector in order to discuss the development of a local declaration for businesses and organisations to express their commitment to the circular transition.

-

Organise a call for projects or a challenge to stimulate circular businesses that could be awarded according to innovative ideas and results.

Certifications are created to assure stakeholders and clients that products and services meet requirements linked to the circular economy. Both the private sector and national and subnational authorities are taking steps in this regard to develop and introduce labels for the circular economy:

-

OrganiTrust®, a worldwide certification body, issues certificates on the circular economy in the following sectors: food contact materials, personal care and cosmetics, furniture, children toys, textiles and fabrics, electronics, building materials, medical safety equipment and household chemicals and detergents. In addition, it also provides this qualification to some service activities, which include transport, construction, telecommunications, cleaning and parking. Once the product or service has achieved the certification, it must be renewed annually.

-

The Amsterdam Made Certificate was developed upon request of Amsterdam City Council (Netherlands). Its main objective consists of informing consumers about products that are made in the Amsterdam area, while seeking to boost creativity, innovation, sustainability and craftsmanship.

-

The French roadmap for the circular economy, 50 Measures for a 100% Circular Economy, launched by the Ministry for an Ecological and Solidary Transition (Ministère de la Transition Écologique et Solidaire) in 2018, includes the deployment of voluntary environmental labelling in five pilot sectors (furnishing, textile, hotels, electronic products and food products).

-

The White Paper on the Circular Economy of Greater Paris (2015[16]) contemplates 65 proposals, including the design and use of circular economy labels. More precisely, it aims to provide higher visibility of existing environmental labels, such as the French NF Environment (a collective certification label for producers that comply with environmental quality specifications) and the European ecolabel, as well as the development of a quality label for second-hand products. The city of Paris is also advancing in the creation of the “NF Habitat HQE” certification, specific for the construction sector. The certification aims to define a “circular economy profile” adding new specific requirements. Besides meeting all mandatory requirements established in the NF HQE Base, construction projects should reach at least 40% of the points established in the “circular economy profile” to be considered circular (e.g. inclusion of a waste management plan, use of recycled materials, development of life-analysis calculations, eco-certification of wood, considering deconstruction processes, establishing synergies with local actors in the surrounding areas, among others).

Source: French Government (2018[17]), 50 Measures for a 100% Circular Economy, http://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/FREC%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2019); Amsterdam (2019[18]), Homepage, http://www.amsterdammade.org/en/ (accessed on 6 June 2019); Paris City Council (2015[16]), White Paper on the Circular Economy of Greater Paris, https://api-site.paris.fr/images/77050 (accessed on 11 June 2019); Organi Trust (2019[19]), Circular Economy and Organic Certification, https://organitrust.org/ (accessed on 11 June 2019); HGB-GBC (2017[20]), Circular Economy for HQE Sustainable Construction.

Promote a circular economy culture

Creating participation spaces to involve citizens, businesses and other relevant actors in public debates and events could raise awareness, stimulate ideas and collaborations. In addition, it would be an opportunity to encourage citizens to embrace sustainable consumption choices in their daily lives. There are several successful examples of promoting the circular economy culture and raising awareness such as: the organisation of a circular weekend in Valladolid, Spain (Circular Weekend, 2019[21]); the organisation of visits to schools in Finland for raising awareness and increasing knowledge of the circular economy among students between the ages of 13 and 16 (Sitra, 2019[22]); and a showroom and educational activities in Germany to spread knowledge on the circular economy and Cradle to Cradle (Cradle to Cradle NGO, 2019[23]).

Key actions

-

Launch communication campaigns to show the impacts of the circular economy (compared to a linear system) and communicate on how citizens and different actors can contribute to it.

-

Create a dedicated website in order to share knowledge and good practices concerning the circular economy.

-

Organise events for knowledge sharing, networking and the promotion of the circular economy at the local level, as well as conferences and seminars at schools and universities in order to raise awareness among children and students in Umeå.

-

Share success stories with the citizens (e.g. through social media, newspapers, television).

-

Use social media to provide quick updates and information on the topic and related events.

-

Make citizens active players in the transition towards the circular economy through co-creation workshops, surveys and contests to identify circular solutions in a range of sectors, from food to sustainable mobility, as well as to gather inputs for new ideas and practices.

-

Organise co-creation thematic workshops to gather inputs from citizens. Instruments for stakeholders engagement include:

-

Multi-stakeholder fora.

-

Workshops.

-

Breakfast meetings on the circular economy.

-

Co-creation methodologies.

-

Feedback loops.

-

copy the linklink copied!Facilitating multilevel co-ordination for the circular economy

The municipality can facilitate collaborations and co-operation among a wide range of actors to make the circular economy happen on the ground. Ways forward are presented below.

Set up co-ordination mechanisms within the municipality

Co-ordination across municipal departments is needed to set priorities and make investment decisions. Also, municipal departments could strengthen collaboration with the City Council Executive Board’s Committees (the Business development executive Committee; the Planning Committee; and the Sustainability Committee) and several independent political committees (e.g. Technical board, the Building board and the Environment board) that will be involved in specific circular economy activities. Co-ordination across these bodies and municipal departments would be needed to avoid duplications or grey areas. Different cities are advancing co-ordination through the creation of dedicated horizontal working groups (Melbourne, Australia, Toronto, Canada and Oulu, Finland); establishing specific teams in charge of coordinating their circular transition (Brussels, Belgium, Paris, France, Amsterdam and Rotterdam, Netherlands, London, United Kingdom, Ljubljana, Slovenia); or setting-up a co-ordination body between the city and the metropolitan area (Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, Spain) (OECD, forthcoming[10]).

Key actions

-

Identify how several municipal departments can relate to the circular economy in their policies (e.g. public procurement, environment, innovation, etc.).

-

Consider appointing a person or a workgroup responsible for co-ordinating the work on the circular economy with a clear mandate over all departments in the municipality to set short-, medium- and long-term goals for the co-ordinator/workgroup, monitor progress and evaluate impacts. Define the ways for co-ordination:

-

Ad hoc meetings.

-

Permanent working group on the circular economy.

-

A technical and political board.

-

Formal or informal fora that gather all municipal departments.

-

Periodical communications on circular economy activities.

-

Facilitate co-ordination with the national government

Co-ordinating with the national government would help align local and national strategies and objectives and ensure consistency amongst objectives. The National Delegation on the Circular Economy will also support this process and may involve subnational governments in the future. For example, the National Delegation on the Circular Economy will also support this process and may involve subnational governments in the future. The Public Waste Agency of Flanders (OVAM) took the initiative in 2018 to set up a national platform for the circular economy, through which the top levels of federal and regional environment departments, economy/innovation departments and finance departments meet twice a year to decide on common action in priority policy fields (OECD, forthcoming[10]), In Spain, the Spanish national strategy created an inter-ministerial body that includes the national government, the autonomous regions and the local governments through the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces (FEMP).

Key actions

-

Several options can be considered to co-ordinate local and national government, such as:

-

A dedicated forum for aligning interests across local and national authorities.

-

Regular meetings between representatives of different departments and agencies in order to provide the opportunity for communication and dialogue.

-

Regular co-ordination groups/meetings with the National Delegation on the Circular Economy.

-

Seminars and workshops together with the national government.

-

Contracts/deals with the national government as tools for dialogue, for experimenting, empowering and learning. The Green Deal Circular Procurement (Box 3.2) is an agreement between organisations that aims to encourage the purchase of goods that are produced in a circular way.

-

-

In addition, the municipality could:

-

Identify the areas where the national contribution is needed to carry out circular initiatives at a local level.

-

Actively participate in public consultations at the national level, when appropriate.

-

Proactively propose circular economy-related actions to the National Delegation on the Circular Economy.

-

Share information with national authorities about local needs preferences, ongoing activities and outcomes.

-

Facilitate co-ordination with the region

A number of strategies at the regional level, including on food, regional development and transport, could benefit from exchanges with the municipality of Umeå in order to harmonise objectives and enhance the effectiveness of the implementation of policies and programmes at the local and regional levels. Moreover, it could ensure consistency between local and regional initiatives and identify potential mismatches between local and regional needs. Västerbotten Region co-ordinates five networks, gathering municipal public officials and a range of stakeholders to find solutions to common problems concerning waste, water and sewage, planning and building, environment and emergency services. As such, the networks could be a useful platform to advance co-ordination actions related to the circular economy. As an example of multilevel co-ordination, the Brussels Region Regional Programme for the Circular Economy 2016-20 is co-ordinated by three Ministers and four regional administrative bodies (Government of the Brussels-Capital Region, 2016[24]).

Key actions

-

Strengthen co-ordination frameworks between the municipality and the region to work on the circular economy, considering the following options:

-

Bodies between regional and local authorities that can take the form of committees, commissions, agencies or working groups.

-

Ad hoc meetings for city-region co-ordination.

-

Network on the circular economy that includes representatives from the region and from all municipalities in Västerbotten.

-

Co-operation agreements between Umeå, the region of Västerbotten and other municipalities of the region for the implementation of joint projects on the circular economy.

-

Joint actions between the municipality and the region and implementation of pilot projects.

-

Joint roadmap with the region of Västerbotten for co-ordination, harmonisation of objectives and improvement of implementation of policies.

-

-

Include circular economy as a key topic on the existing sectoral networks co-ordinated by the region of Västerbotten (e.g. waste, environment, water and sewage).

-

Explore inter-municipal collaboration opportunities in order to detect common needs within the region.

Facilitate collaboration with universities, existing businesses and start-ups

Collaboration with key stakeholders would build knowledge on the circular economy and identify synergies. Further engagement with the academic sector can be considered to build knowledge on circular dimensions that can help the city to identify key sectors and opportunities such as bio-economy and circular design. For example, the city of Amsterdam has been working in triple helix (government, business and academia) and quadruple helix (incorporating citizens to the previous groups) collaboration in different projects, including the circular neighbourhood (e.g. Buiksloterham) (Amsterdam Smart City, 2019[25]). In Paris (France), the Paris & Co incubator merges big and small companies and start-ups work together, exchanging ideas and testing pilots (OECD, forthcoming[10]; Paris&Co, 2020[26]). Furthermore, Circular Oslo-Circular Region (Norway) developed an open-source toolkit for cross-sectoral partnerships (Circular Oslo-Circular Regions, 2020[27]).

Key actions

-

Explore opportunities to sign collaboration agreements between the municipality and the university to work on prioritised areas related to the circular economy at the local level.

-

Identify possible pilots and experimentations that would involve research and development (R&D) departments and university departments, based on identified needs of the municipality.

-

Collaborate with universities to implement the circular economy in existing educational programmes.

-

Organise matchmaking events with business actors from different sectors to start a pilot on circular business models.

-

Collect academic and business proposals to put in place circular activities with social impact and consider support for implementation (e.g. fostering the adoption of shared mobility plans at the company level).

-

Create interactive online platforms of information to encourage stakeholders to exchange with each other on their needs and monitor the activities and updates of the platform.

-

Create co-working spaces for cross-fertilisation amongst several actors.

Facilitate the territorial linkages between urban and rural areas

The forestry, bio-economy and farming sectors could further incorporate circular economy principles to their activities (e.g. sewage sludge is being used as fertiliser in an experimental way in the forest) while strengthening the connection between city and rural areas. The food strategy, currently under development at the regional level, is an opportunity to improve the co-ordination between urban and rural areas and encourage the creation of local production and distribution of food networks. A stronger connection between urban and rural areas may result in a better understanding of the challenges and opportunities for these areas in their transition towards a circular economy. By strengthening the dialogue between rural and urban areas, it would develop a better knowledge of the benefits of their collaboration. For example, in the city of Kitakyushu (Japan), a food recycling loop between rural-urban areas has been established and in Tampere (Finland), rural-urban partnerships have been established related to the biogas sector. The partnership works as a hub that brings together and connects different actors (e.g. farms, power plant operators and logistics) that have not been in contact before (OECD, forthcoming[10]).

Key actions

-

Foster urban-rural partnerships for collaboration in specific sectors (e.g. food, forest, bio-economy) (OECD, 2013[28]):

-

Clarify the partnership objectives, actions and roles of key urban and rural actors.

-

Create circular loops in the bio-economy sector; use of organic waste as fertiliser; last-mile distribution, etc.

-

Share the knowledge and exchange good practices from the urban-rural partnership.

-

Evaluate the results of the partnership.

-

-

Launch communication campaigns in urban and rural areas to present their role in the circular economy transition, the potential benefits of co-operation and to explain how each individual can play a role in the circular transition.

copy the linklink copied!Enabling the economics and governance conditions for the uptake of the circular economy

Making the circular economy happen is about enabling the necessary governance and economic conditions. As such, the city government could:

Identify the regulatory instruments that need to be adapted to foster the transition to a circular economy

The transition to a circular economy would require proper regulation in some sectors such as waste, water, food, and building and construction, to name but a few. Identifying available tools such as specific requirements for land use, environmental permits (e.g. for decentralised water, waste and energy systems), regulation for pilots and experimentation, would clarify potential regulatory uncertainties across different legal entities, gaps and future needs. For example, in the Netherlands, the legal and regulatory framework at the local and regional levels is expected to adapt to the National Circular Economy Strategy (OECD, forthcoming[10]).

Key actions

-

Build a dialogue between the city council, civil society and private sector to identify the main regulatory and legal barriers and identify the sectors where action can be taken (e.g. energy system, the definition of waste and second-hand materials) through ad hoc meetings.

-

Identify regulatory gaps and obstacles, which may go beyond the local sphere as per competency of other levels of governments.

-

Establish a dialogue with regional and national government to exchange about potential regulatory obstacles that can encourage the transition towards a circular economy.

-

Share with the regional and national regulatory authorities the main regulatory barriers and potential solutions identified.

-

Advise companies on consultations concerning circular economy-related legislation.

-

Hold a proactive role in the definition of new legislation instead of being a follower of actions from the national government.

-

Identify areas for opportunities to set specific requirements on land allocation (e.g. energy use, water requirements, demolition, circular construction).

Identify fiscal and economic tools for the circular economy

Economic and fiscal tools can incentivise or disincentivise behaviour to move from a linear to a circular economy. For example, they can affect production modalities and consumption patterns. There is a range of practices in this area, such as the Dutch government’s DIFTAR system (a recollecting scheme based on differentiated tariffs that aims to provide incentives to improve waste separation at source) and discounts on waste fees to businesses in Milan (Italy) and San Francisco (United States).

Key actions

-

Explore the measures that the municipality can apply according to its fiscal competencies. A variety of fiscal and economic tools have been identified from international practices, such as (OECD, forthcoming[10]):

-

Tax reductions on second-hand materials that have already been taxed.

-

Reduction of VAT/taxes as appropriate.

-

Discount on waste fees according to preselected criteria.

-

Differentiated tariffs for waste separation and recycling.

-

Grantns to finance circular economy initiatives.

-

Creation of legislative and normative incentives such as rewarding companies through corporate income tax (e.g. based on the waste generation level, water and energy consumption, use of recycled materials as raw materials).

-

Implement Green Public Procurement

Public procurement is a powerful tool cities can use to promote eco-efficiency and eco-design, reducing the negative environmental impacts of public purchases at the local level. Some international examples can provide inspiration concerning innovative procurement for the circular economy. Box 3.2 presents examples of Green Public Procurement (GPP) experiences. The creation of a monitoring and evaluation framework for GPP will help analyse the procurement policy results, enabling the city to incorporate the lessons learned in the design of new procurement policies and regulations. For instance, the city of Ljubljana (Lithuania) has included some environmental requirements in its tenders; in Paris (France), local authorities have adopted a scheme for responsible public procurement and the city of Toronto (Canada) (OECD, forthcoming[10]), has developed a Circular Economy Procurement Implementation Plan and Framework to use its purchasing power as a driver for waste reduction, economic growth and social prosperity (City of Toronto, 2018[29]).

Key actions

-

Include circular criteria in technical specifications, procurement selection and award criteria, as well as in contract performance clauses (e.g. reuse, durability, reparability, second-hand or remanufactured products).

-

Adapt the public procurement evaluation system, favouring the social and environmental ratings in comparison with the price criteria.

-

Establish clear requirements in tenders in order to foster the change of materials, quality and maintenance (e.g. use of secondary materials in publicly purchased goods).

-

Apply life-cycle analysis approach and develop criteria to evaluate the life cycle of the assets used by each municipal service and use them to perform analysis of infrastructure, solutions and suppliers to foster more sustainable solutions in municipal services.

-

Provide training for staff responsible for the inclusion of GPP.

In OECD member countries, public procurement accounts for approximately 12% of gross domestic product (GDP). Sub-national governments, including cities, are responsible for around 63% of public procurement. Almost all OECD countries have developed strategies or policies to support Green Public Procurement (GPP). High-impact sectors are: buildings, food and catering, vehicles and energy-using products.

According to the European Commission (EC, 2016[30]), the impact of public procurement on the transition to a circular economy is worth around EUR 2 trillion in the European Union, around 14% of GDP. There are several examples of GPP that include circular criteria:

-

Public procurement for circular economy building developments: Amsterdam (Netherlands) has developed its Roadmap for Circular Land Tendering (2017[31]) that includes 32 performance-based indicators for circular economy building developments.

-

Public procurement to encourage the use of circular business models: The city of Zurich (Switzerland) took the decision to lease printing equipment rather than buying it outright, thus only paying per page printed and incentivising better printer performance and energy use.

-

Public procurement to promote “product as a service” schemes: The municipality of Bollnäs (Sweden) has applied what the local government calls “functional public procurement” (funktionsupphandlingen) to rent light as a service in municipal pre-schools and schools. The service is provided by a start-up that received support from Umeå’s BIC Factory business incubator.

-

Public procurement to stimulate social and institutional innovation: The region of Flanders (Belgium) implemented the Green Deal Circular Procurement (GDCP) between 2017 and 2019. Inspired by the Dutch Green Deal on Circular Purchasing (launched in 2013), the joint project was signed by 162 participants (companies and organisations), the Flemish Minister of Environment and its initiators Circular Flanders, The Shift, the Association of Flemish Cities and Municipalities (VVSG) and the Federation for a Better Environment (BBL). In total, 108 purchasing organisations, local authorities, companies, financial institutions and 54 facilitators have been involved. During the 2 years of the initiative, the signatories of the GDCP have conducted more than 100 circular procurement pilot experimentations, building knowledge and experience, and testing tools and methodologies and new forms of chain co-operation.

Some of the obstacles identified in pursuing GPP include: the perception that green products and services may be more expensive than conventional ones; public officials’ lack of technical knowledge on integrating environmental standards in the procurement process; and the absence of monitoring mechanisms to evaluate the achievements of the goals.

Source: OECD (2015[32]), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2019); Municipality of Amsterdam (2017[31]), Roadmap Circular Land Tendering, https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/projects/roadmap-circular-land-tendering (accessed on 28 January 2020); EC (2017[33]), Public Procurement for a Circular Economy: Good Practice and Guidance, http://europa.eu/contact (accessed on 7 November 2019); Municipality of Bollnäs (2018[34]), “New light with many advantages”, https://www.bollnas.se/index.php/88-aktuellt/2525-nytt-ljus-med-manga-foerdelar (accessed on 28 January 2020); The Shift (2019[35]), Green Deal Circular Procurement in Flanders, https://theshift.be/en/projects/green-deal-circular-procurement-in-flanders (accessed on 28 January 2020); OVAM (2020[36]), Green Deal Circular Purchasing, http://www.vlaanderen-circulair.be/nl/onze-projecten/detail/green-deal-circulair-aankopen (accessed on 5 February 2020); OECD (forthcoming[10]), The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, Synthesis Report, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Foster capacity building for the circular economy

Within the municipality of Umeå, capacities can be built in order to design, set and implement circular economy policies that would require new skills, technical competencies and a holistic approach. At the same time, collaborations with universities could be set up to build capacities for entrepreneurs and provide them with the necessary tools to foster the circular transition in the city. For instance, the Chamber of Commerce of Glasgow (United Kingdom) provides capacity-building programmes for businesses aiming to transition to a circular economy (Zero Waste Scotland, 2020[37]).

Key actions

-

Review and analyse the required skills and capacities for carrying out all activities associated with designing, setting, implementing and monitoring the circular economy strategy, such as:

-

Setting circular economy plans/programmes that are realistic, result-oriented, tailored and coherent with national and regional objectives.

-

Co-ordinating across different levels of government, ensuring complementarities and achieving economies of scale across boundaries.

-

Engaging stakeholders in the planning process of circular economy strategy.

-

Ensuring adequate financial resources by linking strategic plans to multi-annual budgets and mobilising private sector financing.

-

Allocating adequate human resources.

-

Collecting and analysing data, monitoring progress and carrying out evaluations.

-

-

Develop, in collaboration with the university for example, targeted capacity-building programmes for public officials and entrepreneurs.

Develop a monitoring and evaluation framework for a circular economy strategy

Once in place, the circular economy strategy would benefit from the existence of a monitoring scheme, as it will help to identify how “circular” the city is, what works, what does not work and what can be improved. The proposed OECD indicators for the evaluation of the circular economy strategy in cities and regions, detailed in Box 3.3, could be helpful in this regard.

Key actions

-

Identify available indicators and data for the monitoring of progress and assessment of results of the circular economy strategy.

-

Create a monitoring and evaluation framework, considering environmental (e.g. resources, waste and circulation processes), flows (e.g. water, energy, products, food, transportation, information, people) and social (e.g. number of circular jobs created) indicators.

-

Generate open data sources if possible (e.g. the publication of consistent and up-to-date information about how people and public vehicles move around the city and other forms of open data can boost the development of innovative start-ups).

-

Collect information on empty buildings, materials used for construction and waste streams and make it publicly accessible.

-

Make inventories of circular economy initiatives and update it regularly.

-

Make an inventory of laws and regulations that can foster the transition from a linear to a circular economy.

-

Use output indicators to evaluate the results of the strategy (e.g. CO2 emission saved, raw material avoided, use of recovered material, energy savings, etc.).

-

Self-assess how “circular” the city is by using the OECD self-assessment framework (OECD, forthcoming[10]).

-

Incorporate the information system into the online circular economy information platform that should be regularly updated and easily accessible.

-

Share with citizens and stakeholders the outcomes and impacts of the strategy through a website.

The proposed OECD Circular Economy Scoreboard for cities and regions consists of a self-assessment of key governance conditions to evaluate the level of advancement towards a circular economy in cities and regions. It is composed of ten key dimensions, whose implementation governments and stakeholders can evaluate based on a scoreboard system, indicating the level of implementation of each dimension (Newcomer, In progress and Advanced).

According to the self-evaluation, the city/region will identify its own level of advancement toward the transition to a circular economy, identify gaps and set its own targets for improvement. The methodology for self-assessment consists in a scoreboard system that can indicate the level of advancement of circular cities and regions towards the transition. Sub-indicators to better specify each dimension are under development and will be tested in the case studies of the OECD Programme on the Circular Economy in Cities and Regions.

Source: OECD (forthcoming[10]), The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, Synthesis Report, OECD Publishing, Paris.

References

[18] Amsterdam Made (2019), Homepage, http://www.amsterdammade.org/en/ (accessed on 6 June 2019).

[25] Amsterdam Smart City (2019), Circular Buiksloterham, https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/projects/circulair-buiksloterham (accessed on 6 June 2019).

[1] Austin’s Circular Economy Story (2020), Welcome to Austin’s Circular Economy Story!, https://kumu.io/ARRCircularEconomy/austins-circular-economy-story (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[15] Circle Economy/EHERO (2018), Circular Jobs and Skills in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area, https://assets.website-files.com/5d26d80e8836af7216ed124d/5d26d80e8836af6ddeed12a2_Circle%20Economy%20-%20Circular%20Jobs%20and%20Skills%20in%20the%20Amsterdam%20Metropolitan%20Area.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

[38] Circular Flanders (2019), Indicators for a Circular Economy, https://vlaanderen-circulair.be/en/summa-ce-centre/publications/indicators-for-a-circular-economy (accessed on 7 November 2019).

[4] Circular Metabolism (2017), The Circular Economy Plan of Paris, http://www.circularmetabolism.com/input/11 (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[40] Circular Metabolism (2017), The Circular Economy Plan of Paris, https://www.circularmetabolism.com/input/11 (accessed on 3 December 2019).

[3] Circular Oslo-Circular Regions (2020), About Circular Regions, https://circularoslo.com/about-circular-oslo-norway/ (accessed on 12 February 2020).

[27] Circular Oslo-Circular Regions (2020), Partnership Methodologies and Toolkit, https://circular-regions.gitbook.io/partnership-methodologies-and-toolkit-for-collabor/methodology (accessed on 12 February 2020).

[21] Circular Weekend (2019), Emprendedores y economía circular, http://circularweekend.org/ (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[12] City of Paris (2019), Quantifier les emplois de l’économie circulaire de Paris - synthèse.

[29] City of Toronto (2018), Circular Economy Procurement Implementation Plan and Framework.

[23] Cradle to Cradle NGO (2019), Homepage, https://c2c-ev.de/ (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[33] EC (2017), Public Procurement for a Circular Economy: Good Practice and Guidance, European Commission, http://europa.eu/contact (accessed on 7 November 2019).

[30] EC (2016), Green public procurement drives the circular economy | Environment for Europeans, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/efe/news/green-public-procurement-drives-circular-economy-2016-09-05_en (accessed on 6 March 2020).

[39] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2019), Denmark: Public Procurement as a Circular Economy Enabler, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/case-studies/denmark-public-procurement-as-a-circular-economy-enabler (accessed on 28 January 2020).

[17] French Government (2018), 50 Measures for a 100% Circular Economy, http://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/FREC%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2019).

[24] Government of the Brussels-Capital Region (2016), Regional Programme for the Circular economy 2016-2020 (PREC).

[20] HGB-GBC (2017), Circular Economy for HQE Sustainable Construction.

[9] LIPOR (2019), Economia Circular: Resíduo como Recurso, https://lipor.pt/pt/a-lipor/o-negocio/economia-circular-residuo-como-recurso/ (accessed on 6 November 2019).

[14] LWARB (2015), Employment and the Circular Economy - Job Creation Through Resource Efficiency in London, London Waste and Recycling Board, http://www.wrap.org.uk (accessed on 12 February 2020).

[6] Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation (2015), A rural development programme for Sweden, https://www.government.se/4adb0c/contentassets/3d8c0f8317224257859ba46dea31a374/a-rural-development-programme-for-sweden (accessed on 5 March 2020).

[7] Morley, A., E. Looi and C. Zhao (2018), Measuring the Circular Economy Developing: An Indicator Set for Opportunity Peterborough.

[31] Municipality of Amsterdam (2017), Roadmap Circular Land Tendering, https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/projects/roadmap-circular-land-tendering (accessed on 28 January 2020).

[34] Municipality of Bollnäs (2018), “New light with many advantages”, https://www.bollnas.se/index.php/88-aktuellt/2525-nytt-ljus-med-manga-foerdelar (accessed on 28 January 2020).

[5] Municipality of Rotterdam (2013), Urban Metabolism – Rotterdam, http://www.fabrications.nl/portfolio-item/rotterdammetabolism/ (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[13] OECD (2019), 1stOECD Roundtable on the Circular Economy in Cities and Regions - Highlights, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/Round-circul-eco-Highlights.pdf.

[32] OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2019).

[11] OECD (2015), Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231122-en.

[28] OECD (2013), Rural-Urban Partnerships: An Integrated Approach to Economic Development, OECD Rural Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204812-en.

[10] OECD (forthcoming), The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, Synthesis Report, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[19] Organi Trust (2019), Circular Economy and Organic Certification, https://organitrust.org/ (accessed on 11 June 2019).

[36] OVAM (2020), Green Deal Circular Purchasing, http://www.vlaanderen-circulair.be/nl/onze-projecten/detail/green-deal-circulair-aankopen (accessed on 5 February 2020).

[2] OVAM (2019), CIRCULAR FLANDERS Together towards a circular economy Kick-off Statement, https://www.vlaanderen-circulair.be/src/Frontend/Files/userfiles/files/Circular%20Flanders%20Kick-Off%20Statement.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2020).

[16] Paris City Council (2015), White Paper on the Circular Economy of Greater Paris, https://api-site.paris.fr/images/77050 (accessed on 11 June 2019).

[26] Paris&Co (2020), Homepage, https://www.parisandco.com/ (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[22] Sitra (2019), “Visits to schools to teach pupils about the circular economy”, https://www.sitra.fi/en/projects/visits-schools-teach-pupils-circular-economy/#what-is-it-about (accessed on 13 February 2020).

[35] The Shift (2019), Green Deal Circular Procurement in Flanders, https://theshift.be/en/projects/green-deal-circular-procurement-in-flanders (accessed on 28 January 2020).

[8] Vercalsteren, A., M. Christis and V. Van Hoof (2018), Indicators for a Circular Economy, Circular Flanders, https://vlaanderen-circulair.be/src/Frontend/Files/userfiles/files/Summa%20-%20Indicators%20for%20a%20Circular%20Economy.pdf.

[37] Zero Waste Scotland (2020), Circular Glasgow, http://www.zerowastescotland.org.uk/circular-economy/circular-glasgow (accessed on 13 February 2020).

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/4ec5dbcd-en

© OECD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.