3. Cultivating positive attitudes and values in a learning ecosystem

Students develop values and attitudes within a learning ecosystem – formally, informally and non-formally. They learn through the formal school curriculum, but also through their peers and teachers at school, from siblings and parents at home, and from others with whom they interact in the community. This chapter explores the role of “hidden curriculum” in fostering students’ attitudes and values. It also introduces a curriculum redesign framework, which illustrates how various levels of the curriculum ecosystem interact with each other and impact design, content and implementation. This framework provides a model of how attitudes and values can be introduced and, in turn, influence the development of students’ beliefs, values, dispositions and behaviours. It also looks at data, research findings and shared experiences that can support the development of students’ attitudes and values, as well as personal perspectives on the values and attitudes students and teachers believe a holistic education should provide.

Cultivating positive attitudes and values in school can occur formally or informally. An increasing body of research suggests that students develop their attitudes and values in a large learning ecosystem, nourished from childhood and influencing students’ well-being as well as cognitive development into their adult lives.

One of the questions that arises with values and attitudes teaching is whether they are visible in the curriculum and taught explicitly, or left implicit and “caught” by students informally, as a result of their experiences with learning activities in the classroom or as part of their broader school life. Examples of explicit teaching include discussion of values and attitudes during formal gatherings such as assemblies, or specific approaches such as case studies and role plays, or engagement of learners in targeted classroom activities meant to develop their sense of accountability and duty (Maphalala and Mpofu, 2018[1]). Some countries have subjects such as moral education and ethics, or consider moral education or ethics as part of the cross-curricular themes or competencies and embed them into relevant subject areas (OECD, 2020[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]).

Values and attitudes that are not necessarily specified in the curriculum can also be “sought” or something that students might “aspire” to have or be. Teachers and parents often seek to cultivate a school or home culture with a certain set of values they believe to be important. Students often aspire to values modelled by their friends, siblings, teachers, parents, or professionals from the real world who may be engaged in values-oriented philanthropic activities, for example writers, musicians, or athletes, whom students might admire as role models.

The concept of a hidden curriculum is also relevant here. It refers to unspoken or implicit values, behaviours and norms that exist in educational settings, conveyed or communicated without awareness or intent (Alsubaie, 2015[4]; Jerald, 2006[5]). Teacher beliefs play a key role in this hidden curriculum and are a critical dimension of teacher quality in relation to non-academic competencies, when considering their observed practices in the classroom and their students’ perceptions of effectiveness (Witter, 2020[6]). Witter’s review suggests that student-centred beliefs about teaching and deeply oriented beliefs about learning correlate with better cognitive outcomes for students (Witter, 2020[6]), indicating that consciousness of values and beliefs is essential for pedagogical intervention.

To analyse how students develop their attitudes and values, not only being taught in formal learning settings, but also in informal and non-formal settings, a much broader analytical framework is necessary. The OECD E2030 project has set out a multi-layered ecosystem framework to curriculum change (with micro-, meso-, exo-, macro- and chrono-systems) (Figure 3.1). This can illustrate the complex landscape in which students learn from many people, including those other than teachers; even from animals and nature; from home, school or neighbourhood/community environments; or through the roles they are given to play; and learn from reflections on the experiences or events they have gone through.

A selection of proverbs/sayings from Japan and New Zealand below illustrates how it has been long perceived that attitudes and values are learned in a holistic environment, including formal, non-formal and informal learning (Box 3.1).

Words of wisdom or proverbs often suggest how attitudes and values can be developed from the environment and people around us, not only through formal teaching. Some examples are given below.

Cultural perspectives: Japan

“Tachiba-ga Hito-wo Sodateru” – When a person is given a certain role or a position, they will grow with the role/position through the actual experience of using the competencies needed for that role/position as well as through their aspiration to fill that role/position.

The Japanese national curriculum includes both subjects and non-subjects. Non-subject education includes “Tokubetsu katsudo/Tokkatsu” (special activities), such as classroom activities, student council activities, club activities and school events. Tokkatsu is intended to support fostering student agency, in particular, attitudes and values through experiential, collaborative and interactive learning. For classroom activities, students are often assigned to play a “role” in maintaining and improving their school life, through which they are expected to develop a sense of responsibility, leadership and agency. These roles are not limited to student representatives but include a wide range of responsibilities associated with running a classroom as a community, e.g. publishing classroom newspapers, creating a classroom mini-library, organising students to learn their own classrooms, organising school meals, organising fun activities, or taking care of a classroom pet. This wide-range approach to leadership roles allow many students to have the opportunity to experience “acting as a leader”. By experiencing the role, students develop a certain sets of attitudes and values e.g. responsibility, empathy, collaboration, conflict resolution, and patience. This also provides opportunities to develop and learn to value friendship based on trust.

Cultural perspectives: New Zealand

“Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi engari he toa takitini” – I come not with my own strengths but bring with me the gifts, talents and strengths of my family, tribe and ancestors.

From Te Whāriki (2017) In Māori tradition, children are seen to be inherently competent, capable and rich, complete and gifted no matter what their age or ability. Descended from lines that stretch back to the beginning of time, they are important living links between past, present and future, and a reflection of their ancestors. These ideas are fundamental to how Māori understand teaching and learning.

Source: (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2017[7]).

The OECD E2030 multi-layered ecosystem approach to curriculum change: Micro-, meso-, exo-, macro- and chrono-systems

Research points to an array of localised contextual factors and the reciprocal relationships among them that affect curriculum design and implementation (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998[8]; McLaughlin, 1990[9]; Spillane, Reiser and Reimer, 2002[10]; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2018[11]).

The OECD Education 2030 ecosystem approach to curriculum analysis (Figure 3.1; Table 3.1) reflects the scope and complexity of systems that interact, build upon and influence one another, which have an impact on an individual’s development through life. The model recognises the interactions between system levels, the students and their environments, and how these affect student learning. At the broadest macro-level, cultural and societal beliefs about the purpose of education are overarching influences that have an impact on curriculum design, implementation and student learning (OECD, 2020[12]).

The ecosystem approach to curriculum redesign provides a framework for consideration of how values and attitudes can be an integral part of the redesign process.

From students’ perspectives on how the ecosystem approach can be applied to their own learning, they highlight the important role of attitudes, values and skills, such as trust, empathy, and co-operation, as integral components that can connect all the people across these different layers of the learning ecosystem (Box 3.2).

As Miki has been studying online, she wishes to develop and is conceptualising, with the support of Dzhafar, from Almaty, Kazakhstan, an online collaborative learning platform. The platform is based on trust, empathy and co-operation to connect students and stakeholders all over the world. Its purpose is to provide opportunities for students to promote their ideas and make friends, and a space for companies and local governments to find and support them.

Miki and Dzhafar see the benefits of the platform during the impact of COVID-19, with direct connections reduced as students study at home and online. In Miki’s opinion, this is an opportunity to make stronger connections in different ways. Digitalisation can enable a society where “no one is left behind”.

The platform Dzhafar suggests to co-create is based on the ideas from a discussion about a “school of the future” which:

Miki and Dzhafar believe that the platform offers multiple opportunities and use the analogy of the components of a hamburger to describe these: the top bun of the hamburger represents the whole idea, the platform itself. They explain, “The platform is driven by students, and students see this as a vehicle for minimising barriers and creating a friendly and co-operative atmosphere. It is not about competition, it is all about collaboration.” In addition to the bun, the “ingredients” bring out flavour. The “ingredients” of the platform are the stakeholders who make this project possible: students, teachers, businesses and government agencies.

Government agencies:

“The bottom bun is the base, the foundation upon which all the ingredients are combined, the opportunity to bring all stakeholders together.” As a result of her own experiences and her need of a trusting environment to learn, Miki imagined this broad, collaborative space. “It’s about finding people around the world who can understand you and empathise with you. By teaming up with someone else, we can take our ideas closer to realisation. If the idea spreads around the world, it may become an important part of someone else's idea. I think it would be interesting to make friends and project partners all over the world through this platform.” Miki hopes that this platform could be a catalyst for a better society, “I would like to create this platform as a system that connects the world with trust, valuing the harmony between technology and philosophy.”

Source: Panel presentations of the OECD Joint Thematic Working Group Webinar of 21 June 2021.

Policy, people and places

Curriculum redesign and implementation is a complex process that involves the intersection of multiple policy dimensions, a range of people and diversity of places (Honig, 2006[16]). Thus, the complex learning ecosystems can also be re-conceptualised through these three dimensions, which can cut across the micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, and chrono-systems:

The policy dimension of curriculum redesign and implementation includes the goals, tools, documents, programmes and resources associated with the redesigned curriculum. This can include, for example, national curriculum, standards, or learning objectives (macro), teacher licensing and training (exo), school-level policy and guidance documents (meso), lesson or unit plans in classrooms (micro). Top-down approaches to curriculum design and implementation suggest a clear delineation between those who design curriculum (e.g. experts, government officials) and those who are given, or mandated, a curriculum to implement (e.g. teachers). Bottom-up approaches to implementation grant autonomy to local district, schools and educators, often involving students themselves, to design, make decisions about, and implement curriculum. Top-down and bottom-up approaches emphasise an iterative relationship between curriculum design and implementation, suggesting that how a curriculum is designed impacts implementation and how implementation unfolds reshapes the curriculum design (Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2018[11]; Tichnor-Wagner, 2019[17]).

People include all of those who play a role in designing and implementing curriculum. This includes, for example: students, teachers, parents, school leaders (micro and meso), teacher educators and community members (exo), and administrators, policymakers, and the media (macro). Teachers of course implement the curriculum, which is informed by the needs of the students in the classroom. They also can participate in the design phase. School leaders and administrators typically play a more significant role, but, as discussed in the policy dimension, other stakeholders should also be involved.

Places, or the varied contexts in which a curriculum is taught, shape implementation. This includes individual teachers’ prior experiences and beliefs; the level of trust among administrators and teachers; how school leaders frame and prioritise new curriculum; the vision that school leaders set for the school; opportunities for teacher collaboration and the nature of those interactions; available resources such as money, materials and time; competing policy demands; and workplace norms such as trust, communication, and collaboration (Bryk, Camburn and Louis, 1999[18]; Coburn, 2001[19]; Coburn and Russell, 2008[20]; Chapman, Wright and Pascoe, 2016[21]; Cheung and Wong, 2012[22]; Hamilton et al., 2013[23]; Stringfield et al., 1998[24]; Wohlstetter, Houston and Buck, 2015[25]; Priestley and Biesta, 2013[26]; Simmons and MacLean, 2016[27]).

Students, teachers and school leaders, as well as their educational environments, are part of a larger ecosystem in which parents and communities also play a role. At a government level, it is evident that there is extensive support for curriculum content to include attitudes and values and that this is promoted within the broader ecosystem, from teachers and parents to all wider educational stakeholders. Students can co-create learning environments in their classes, supporting teachers’ explicit and hidden curricula. They can be aspirational to others or role models in fostering attitudes and values among their peers. Different strategies are in place to make sure the whole curriculum is effectively implemented.

Stakeholders at all levels are responsible for teaching values and attitudes throughout students’ educational journeys. Students are learners but also active observers who seek and absorb attitudes and behaviours to which they are exposed in their social environments. Parental support is crucial for a healthy and solid social-emotional development. Teachers are known to be the main creators of classroom cultures and direct influencers of students’ growth mindset (Bryan et al., 2021[28]), and, in general, values drivers, even without intent; their influence is developed from early childhood education and care. Finally, the influence of local communities, foundations, private companies and other social partners can be essential for encouraging students’ passions, career and personal ambitions, as well as motivation for lifelong learning.

Student aspirations for developing attitudes and values in school

Putting students at the centre of learning implies taking into consideration the values that matter most to them. When asked about which values should be part of the curriculum and therefore implemented in schools, students have strong opinions, based on their own experiences and aspirations for their societies. In feedback, students indicated that personal and school experiences, both positive and negative, and expectations for their adult lives were what influenced the values and attitudes they considered during their time at school.

Curriculum designers face challenges related to incorporating values in curriculum, such as resistance to inclusion, and difficulties in reaching consensus across diverse stakeholders on which values (if any) to include. While these difficulties may seem common across systems, they are not generalisable across contexts. A study in England showed that students expect schools to help them develop particular values as part of the education of the whole child. The study, which examined the perceptions of over 5 000 students aged from 10 to 19, reported that students expect teachers to engage in character-development education about the values which can assist in their holistic development (Arthur, 2011[29]). Curriculum designers may be heartened to know that students themselves appreciate that curriculum covers values in addition to disciplinary learning.

At OECD Education 2030 workshops and related opportunities for collaboration and sharing of ideas, students discussed how cognitive and social/emotional skills are prerequisites for further learning, developing student agency and ensuring well-being. The following personal reflections highlight the values and attitudes that students considered as imperatives of curriculum design (Box 3.3).

Carina – Empathy required for teamwork, respect and co-operation

17-year-old Carina recognises that her experiences directly influence the attitudes and values she most prizes. The Brazilian-Portuguese student has studied in two different countries and is now preparing for university as she completes her senior year in Portugal, specialising in Sciences and Technologies. Intending to follow a path in STEAM, Carina believes that understanding individual differences should be taught from an early age. As someone who is both passionate about foreign languages and technological development, she finds it frustrating that peers try to categorise her in either a science or a humanities program.

17-year-old Carina recognises that her experiences directly influence the attitudes and values she most prizes. The Brazilian-Portuguese student has studied in two different countries and is now preparing for university as she completes her senior year in Portugal, specialising in Sciences and Technologies. Intending to follow a path in STEAM, Carina believes that understanding individual differences should be taught from an early age. As someone who is both passionate about foreign languages and technological development, she finds it frustrating that peers try to categorise her in either a science or a humanities program.

Regardless of the area of knowledge to which one dedicates oneself, she thinks that teamwork, respect, and co-operation should be encouraged and learned within the classroom, bringing teachers and students together to strive for the well-being of all. Carina sees empathy and compromise as essential components of co-operation and teamwork.

Curiosity, motivation, and confidence building up for agency

She also thinks curiosity should be encouraged as it impacts students’ motivation to learn. For Carina, empowering students means giving them knowledge, skills and the tools needed to make an impact. Having teachers encourage students in the process, so one becomes more confident in one’s own abilities, positively affects their sense of agency.

Carina remarks that innovation, progress and development can only happen tomorrow if we pay close attention to the way our students are evolving today. The personal pursuit of knowledge with the occasional aid of parents, teachers, colleagues, is an approach she advocates. “All of the values I mentioned should be taught, caught and sought in a student’s daily life: taught and caught by and with teachers, family members and peers, and sought by the student either by themselves or whilst co-operating with others. Co-creation and co-construction both apply in this context. Values guide our attitudes, so it makes sense that, for holistic, complex individuals like humans, holistic values are taught, caught and sought. Regardless of where I am, what I’m studying or what I’m planning to do next, I know for a fact that I will guide myself by values that emphasise who I am”.

Source: Panel presentations of the OECD Joint Thematic Working Group Webinar of 21 June 2021.

Arfath – Creativity, interaction, freedom, justice and equity

Arfath is a 15-year-old student from Bangalore who shared that he believes the three most important values to develop in curriculum are creativity, interaction and freedom.

In his opinion, many and varied talents bring creativity into the world. Creativity relies on imagination and new ideas. Interaction, for Arfath, helps us develop; it allows us to meet new people, to have enriching conversations, to learn from and with others and to produce work collectively, developing our learning experience in groups.

He believes that there is still discrimination in terms of gender, caste and religion and sees equity as freedom: “We have to eliminate discrimination and understand that everyone is equal and has equal rights ... using our own words and our own thinking are important so we can develop a better self and a better world.”

Source: OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030 Student Voices on Curriculum (Re)design campaign, bit.ly/2030StudentVoice.

Tara – collaboration, learning from failure and trust

Tara, a 13-year-old student from Indonesia, believes that the most relevant values to be incorporated into curriculum are positive social interactions and collaboration with other students, teachers and friends; learning from the experience of failure; and trust.

Tara, a 13-year-old student from Indonesia, believes that the most relevant values to be incorporated into curriculum are positive social interactions and collaboration with other students, teachers and friends; learning from the experience of failure; and trust.

“Socialising and learning with classmates create a comfortable environment, which can help reduce anxiety and stress in students who have so much responsibility, positive interactions also create a welcoming atmosphere for newcomers. The experience of failure is knowing and embracing that mistakes happen and that we can learn from them. Making a mistake not only helps us improve but also promotes independence and self-confidence.

Feedback that includes reference to mistakes can be more meaningful than grades. Grades only increase anxiety and stress! Building trust enables students and teachers to feel safe while interacting – students are better able to focus on lessons, instead of being worried about making the teacher upset.”

Tara sums up these interconnected values: “Let’s create a healthier and happier class environment for a better future!”

Source: OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030 Student Voices on Curriculum (Re)design campaign, bit.ly/2030StudentVoice.

As highlighted by Tara (Box 3.3), it is important to provide students with space where they can feel safe and learn from failures. This is particularly important for students’ well-being, and part of the conditions that make students’ learning more effective and enjoyable. For this, it is important to avoid creating excessive pressure to learn new and more content, as well as anxieties and stress about exams (OECD, 2020[2]); this can be deeply rooted in the culture with attitudes and values such as fear of failure, fear of losing, or fear of missing out (Box 3.4).

Kiasuism: Definition, origins and implications

Kiasu is a lexical innovation used in Singapore to describe a preoccupation with the refusal of allowing oneself to lose out on any opportunity to get more, win or be superior to others (Ho, Munro and Carr, 2020[30]). In the context of education, it is commonly used in Singapore to describe the lengths to which parents will go to ensure their children do not lose out to their peers academically (Bedford and Chua, 2018[31]).

The origins of Kiasuism stems from the Chinese-Hokien dialect, literally translating to “the fear of losing”. Kiasuism is expressed in the fear of failure, the fear of being ridiculed, and the fear of social evaluation. The term FOMO (“fear of missing out”) among social media users, particularly teenagers and young adults, appears to be a similar experience to kiasuism, resulting in heightened levels of anxiety and competitiveness (Milyavskaya et al., 2018[32]).

The traits of kiasuism create barriers in education (Bedford and Chua, 2018[31]) due to anxiety about making mistakes, failing in examinations and jobs, or falling behind peers. Although the kiasu attitude can manifest positively as diligence and hard work (Chua, 1989[33]), it can lead to negative, envious and selfish behaviours if unbridled. Kiasuism surfaces in education as a desire to be ahead of peers in terms of academic performance and, ultimately, societal standing upon graduation. There is high pressure from society and parents for students to do well academically, resulting in an examination and results-oriented system with a general lack of curiosity for intellectual pursuit (Ho et al., 1998[34]). In the hope of giving their children an edge over others, parents go to great lengths to ensure that their children receive as many educational advantages as possible. This includes tuition and enrichment classes, or even relocating to neighbourhoods near “good” schools in order to gain prioritised chances for their child’s admission to these schools. This “more is better to get ahead” syndrome can result in overload and burnout for Singaporean students, as tuition and enrichment classes often come at the sacrifice of play and rest time. This widens the socio-economic disparity and deepens the fault lines of society when only students of higher socio-economic status stand to benefit from such opportunities.

Studies on Kiasuism

Three decades ago, the Report of the Advisory Council on Youths (1989[35]) identified kiasuism as an underlying attitude of Singapore youth’s approach to education, work and other aspects of their lives. Three decades later, kiasuism continues to be an integral part of Singapore society, governing many attitudes and behaviours across areas of life and generations. The National Values Assessment Survey (NVA) organised by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) in 2012, 2015 and 2018, identified kiasu as the top value of Singapore society in all three years (aAdvantage Consulting Group, 2018[36]). A recent cross-cultural comparison study involving 136 Singaporeans and 128 Australian university students, suggested that kiasuism is a not unique to Singaporean culture (Ho, Munro and Carr, 2020[30]). Another study on kiasuism identified its cognitive aspects and concluded that kiasuism is a single dimension with a range of outcomes, with the motivation for an exhibited behaviour as the determining factor. In recent years, more light has been shed on kiasuism and the hyper-competitive culture in Singapore as well as how it is affecting the mental well-being of students (Poh, 2018[37]).

Policy response and alternative pathways for success

To address student well-being, the Ministry of Education in Singapore has been taking steps to “loosen” the education system, with the hope of making it less of a “pressure cooker”. These include restructuring national examination assessment and curriculum systems. For example, the T-score system for the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) was recently changed into a wider grade band system, which is less rigid and finely differentiated, discouraging students, teachers and parents from being overly focused on “chasing that last mark”.

There has also been stronger emphasis on recognising students’ non-academic abilities in other areas like sports, performing arts, uniformed groups and community service. Due to increased mental health issues brought about by the pandemic, MOE has also reduced the scope of year-end examinations in 2021 and is aiming to hire more school counsellors to ensure students’ mental well-being (Lim, 2021[38]).

“Against a more competitive landscape, there can also be demands to make our tests sharper to distinguish one student from another. However, we should be careful and not go overboard,” cautioned Mr Chan Chun Sing, Singapore’s Minister of Education (Min, 2021[39]). He raised students (and parents) not being so concerned about competing with their peers, rather to develop a healthy hunger for personal excellence and growth, preparing themselves for the modern economy where opportunities abound to create a new future for themselves.

Source: Oon seng Tan, Ee Ling Low, Jocelyn Tan, and Jallene Chua from National Institute of Education, Singapore.

FOMO

“FOMO” stands for the “fear of missing out” and refers to the feeling of “anxiety, whereby one is compulsively concerned that he/she might miss an opportunity for social interaction, a rewarding experience, profitable investment or other satisfying event” or “an overwhelming urge to be in two or more places at once, fuelled by the fear that missing out on something could put a dent in one's happiness". Research has shown that there is a relationship between FOMO and mental health, social functioning, sleep, academic performance/productivity, neuro-developmental disorders, and physical well-being.

For students’ learning, several studies have examined the relationship between Internet use and academic performance. While some studies have indicated positive links between these among high school students, others have started to explore possible links with problematic Internet use behaviours, suggesting that some characteristics of cyberspace put teenagers at risk, combined with adolescent traits, e.g. developmental changes during pubertal maturation and brain development, sensitivity to stimulation, relationship with parents, and an expanding social peer environment.

Other recent studies have started to explore the relationships between FOMO, problematic internet use, and students’ learning approaches (e.g. deep or surface learning) and suggest that self-regulation might help students control their levels of FOMO and their problematic Internet use inside and outside of learning environments.

In relation to attitudes and values, self-regulation is aligned with mindfulness, reflective thinking and meta-learning (See Chapter 2), and developing values and attitudes such as respect for self and self-worth may help mitigate the effects of FOMO.

Sources: Gupta and Sharma (2021[40]) “Fear of missing out: A brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health”; Alt and Boniel-Nissim (2018[41]) “Links between Adolescents' Deep and Surface Learning Approaches, Problematic Internet Use, and Fear of Missing Out (FoMO)”; Abel, Buff and Burr (2016[42]) “Social Media and the Fear of Missing Out: Scale Development and Assessment”; Haggis (2003[43]) “Constructing images of ourselves? A critical investigation into ‘approaches to learning’ research in higher education”.

To shape a better future towards increased well-being of individuals and the planet, today’s society needs a new narrative and a big mindset shift, along with systemic change, for which revising the goals of education set out in curricula is of fundamental importance.

Research findings about students’ attitudes and values for better learning and well-being

How can these attitudes and values students aspire to develop with their own sense of purpose help them to thrive in today’s and tomorrow’s world? Research suggests that social and emotional learning is correlated with increased student academic outcomes and highlights the importance non-cognitive factors play on psychological well-being and the education of the whole child/learner (Darling-Hammond and Cook-Harvey, 2018[44]; Farrington et al., 2012[45]; Weissberg and Cascarino, 2013[46]; Kanopka et al., 2020[47]; OECD, 2021[48]).

How will such skills, attitudes and values support students to enhance their learning and well-being or further develop other types of skills, attitudes and values? The following section will summarise some of the recent findings from the OECD data and literature that are relevant to the types of attitudes and values considered as part of future-ready competencies in the OECD Learning Compass.

Persistence, eagerness to learn new things, and curiosity

A recent OECD report shows, for example, that students’ social and emotional skills are strongly related to their psychological well-being and that 15-year-old students who describe themselves as highly creative also tend to report greater levels of persistence and eagerness to learn new things (OECD, 2021[48]) The study also reported that students’ social and emotional skills are strong predictors of school grades, irrespective of students’ background, age cohort and location. This is particularly the case for attitudinal skills, such as persistence and curiosity, which are strong predictors of student performance among 10-year-old and 15-year-old students (OECD, 2021[48]).

Motivation to learn, motivation to achieve and goal orientation

The impact of quality values education is not limited to students’ affective development and well-being; it also has the potential to improve their academic progress (Benninga et al., 2003[49]; Benninga et al., 2016[50]; Lovat and Clement, 2008[51]; Zins et al., 2004[52]; Berkowitz and Bier, 2007[53]). Students who understand and internalise values and attitudes may, in turn, be more motivated to learn and engage in critical thinking activities. Indeed, incorporating values into education has the potential to promote behaviours that make learning more effective for students.

PISA 2012 results showed that two of the most important ingredients for success in school are the motivation to achieve and being goal-oriented (OECD, 2013[54]). These attitudes allow students with less ability but more determination to be better able to pursue and achieve their goals than students with more ability but who are unable to set objectives for themselves (Eccles and Wigfield, 2002[55]; Duckworth et al., 2010[56]).

These attitudes are also crucial beyond school: being motivated and able to successfully set and pursue goals can be driving forces behind lifelong learning for future citizens (OECD, 2013[54]). These aspects, e.g. goal-setting and motivation, are deeply connected with the concept of student agency in the OECD Learning Compass (OECD, 2019[57]).

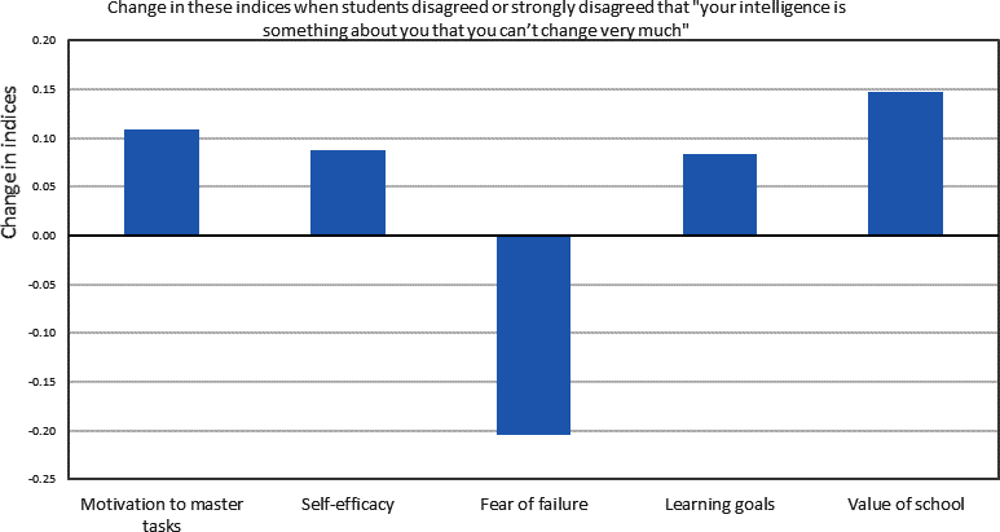

Growth mindset, self-efficacy, higher levels of motivation and lower levels of fear of failure

PISA 2018 data showed that when students had higher motivation and self-efficacy, set more ambitious learning goals, and valued school more, they scored higher in reading, mathematics and science. The data also showed that students scored higher on reading when they reported greater co-operation among peers and that students who reported having a growth mindset scored higher in PISA. Furthermore, the analysis suggests how student attitudes are interrelated across different aspects, e.g. students with a growth mindset valued school more, set more ambitious learning goals, reported higher levels of self-efficacy, and displayed higher levels of motivation and lower levels of fear of failure (OECD, 2019[58]).

As discussed earlier, hidden curriculum can play a positive or negative role in education at a system or school level; therefore, it is important to be aware of its potential and how it may manifest in school (Alsubaie, 2015[4]). Teachers may employ a hidden curriculum to complement official curriculum’s expected values, or to encourage learners to develop behaviour patterns that are valued in society (Cornelius-Ukpepi, Edoho and Ndifon, 2007[59]).

Teacher self-awareness and self-reflection are necessary to making a valuable hidden curriculum an explicit adjunct to the intended written curriculum. The OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030 project is currently exploring the types of competencies future-ready teachers need, and is working on the teacher-related concept-making and vision-making, e.g. new interpretations of teacher agency and teacher well-being. The visions will be developed into the OECD Teaching Compass, which will mirror the OECD Learning Compass.

The following section will explore research findings and cutting-edge practices regarding teachers’ increased support of student learning and well-being; e.g. teachers’ self-efficacy, collective teacher collective self-efficacy; teachers’ perceptions of a subject discipline's boundaries; teacher agency, co-agency; mutual trust, respect and responsibility – with students and parents; and relationships, school climate, and growth mindset classroom cultures.

Teachers’ self-efficacy, enthusiasm for better student learning outcomes, job satisfaction and relationships at work

Teachers' attitudes and beliefs of expectancy and self-efficacy have been found to promote student cognitive engagement and achievement in academic activities (Archambault, Janosz and Chouinard, 2012[60]). In past decades, a number of studies pointed out the important role of teachers’ self-efficacy on student achievement outcomes (Anderson, Greene and Loewen, 1988[61]; Midgley, Feldlaufer and Eccles, 1989[62]; Mujis and Reynolds, 2000[63]). Different studies have proven that teachers who possess a high sense of self-efficacy and believe in their capacity to help students learn are usually more satisfied with their own work and with their students’ behaviours and learning abilities (Pajares and Graham, 1999[64]; Tschannen-Moran, Hoy and Hoy, 1998[65]; Caprara et al., 2006[66]).

Other studies confirm this – teacher self-belief engenders positive attitudes, such as greater professional accomplishments, more stimulating relationships with colleagues, and higher enthusiasm regarding their role as teachers (Evans, 1998[67]; Ross, 1998[68]; Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001[69]) – attitudes that will in turn have a positive impact on students’ motivation, and on their willingness to keep involved and on task, and their positive attitudes towards school (Ashton and Webb, 1986[70]; Evans, 1998[67]; Soodak and Podell, 1993[71]; Ross, Hogaboam-Gray and Hannay, 2001[72]). Teacher enthusiasm and support also predicted student enjoyment of reading (OECD, 2019[58]).

At schools in which teachers’ collective self-efficacy is strong, students perform better and the influence of individual characteristics, such as socio-economic status and ethnicity, on achievement is reduced (Bandura, 1993[73]; Newmann, Rutter and Smith, 1989[74]; Archambault, Janosz and Chouinard, 2012[60]). This is highly aligned with the concept of agency, co-agency and collective agency, not only for students but also for teachers.

Teachers’ perceptions of subject discipline boundaries for students' curiosity, epistemic knowledge, humility and attitudes towards learning-to-learn

Children’s epistemic curiosity in the classroom is in large part directed by their teacher and their perceptions of the subject discipline’s boundaries (Bernstein, 2000[75]). For example, in secondary schools, there is a tendency to teach individual subjects in silos, apart from other subjects. When subject compartmentalisation becomes entrenched, consideration of wider contexts or the scope of real-world problems can be diminished (Billingsley et al., 2016[76]). This has been illustrated in a scenario where students walked out of a history class and a science class with different explanations as to why the Titanic sank and different perceptions of who was to blame.

In a world that rewards individuals who can create, apply and synthesise knowledge (OECD, 2013[77]; OECD, 2016[78]) examining big questions and real-world problems helps to build student resilience to misinformation and can improve students’ attitudes towards learning. For example, participants in a big questions workshop called ‘Renoir’s Painting’ used scientific and artistic ways of investigating to address the question: “How did audiences see and react to Renoir’s portrait Madame Léon Clapisson when it was first painted?” (see (Billingsley and Windsor, 2020[79])). Another example of the workshop was to question whether robots can ever be persons succeeded in developing participants’ appreciation of the strengths and limitations of science and the distinctive natures of different disciplines in a real-world context (Billingsley and Nassaji, 2019[80]).

These workshops aimed and succeeded in increasing students’ epistemic insight and in particular, their epistemic curiosity and their critical thinking about the nature, application and communication of knowledge. Pedagogies and practice that assist young people to become knowledgeable require learning spaces that cultivate intellectual and moral virtues like wisdom and compassion, alongside pedagogies that enhance students’ capacities to work with uncertainty and consider different disciplinary perspectives (Billingsley et al., 2018[81]) (OECD, 2019[82]).

Teacher agency and co-agency building on mutual trust, respect and responsibility –with students and parents – for better relationships, school climate, and growth mindset classroom cultures

When teachers have high expectations, believe students have the ability to learn, and take responsibility for students’ learning, students are more engaged, feel more competent while they are learning, learn more, use fewer avoidance strategies when facing difficulties, and perform better (Feldlaufer, Midgley and Eccles, 1988[83]; Lee and Loeb, 2000[84]; Stipek and Daniels, 1988[85]). Moreover, regardless of students’ abilities, when teachers trust students’ potential and ability to learn, students feel more competent and report greater engagement and achievement (Brophy, 1983[86]; Connell and Wellborn, 1991[87]; Goddard, Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001[88]).

The recent health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has changed priorities globally. New values have emerged as part of tackling the crisis, to both guide responses to possible future crises of this same magnitude, and to learn from this situation. In essence, the pandemic provided teachers and parents with the opportunity, though unplanned, to assess the extent to which children and young people successfully exhibited or demonstrated what emerged as essential values and dispositions such as trust, respect, responsibility and reliability during this time (Lambert, 2020[89]).

School climate can be conceptualised as students’ sense of belonging, disciplinary climate and teacher support, among other features (OECD, 2019[58]). A report on the inclusion of values in the Australian curriculum indicates that education about values has the potential to positively impact school climate, the classroom environment and teacher-student relationships, therefore supporting better student learning outcomes and more positive attitudes and behaviours (Curriculum Corporation, 2003[90]). Values education can also improve interactions between students, which in turn contributes to more harmonious and productive learning environments (Lovat, 2011[91]) (Flay and Allred, 2010[92]; Goodwin, Costa and Adonu, 2004[93]; Snyder et al., 2009[94]; Watson, 2006[95]).

A positive school climate is recognised as being critical for students, teachers, parents and school leaders. Research conducted with 480 adolescents from urban schools in Sydney, Australia, found that non-instructional aspects of the school experience, such as the relationships that adolescents had with adults at school and with peers, were protective factors that contributed to their resilience and academic achievement (Wasonga, Christman and Kilmer, 2003[96]). Values in curriculum that promote behaviours and attitudes around co-operation, enthusiasm and self-efficacy among students and teachers may, in turn, relate to better performance.

Classroom cultures with growth mindset help to support and galvanise student motivation, behaviour and performance by giving students an adaptive way to make meaning from everyday academic experiences. Research shows that students guided by a growth (vs. fixed) mindset tend to pursue goals that emphasise mastering challenges (as opposed to goals designed to bring positive and avoid negative judgements of their ability). They tend to view failures and setbacks as signs that they need to exert more effort and try new strategies (rather than as signs that they lack ability), and they tend to see mistakes and confusion as an important part of the learning process (rather than an indicator of limited potential) (Murphy et al., 2021[97]). New strategies are needed to achieve new vision, cultivate new school cultures, and new competency-based curriculum, which highlight the important role that attitudes and values can play. The experience of a school in Israel illustrates how a new skills-based curriculum incorporated co-agency and collaboration as essential components of its development (Box 3.5).

Defining a new set of values and the Learning Compass ecosystem

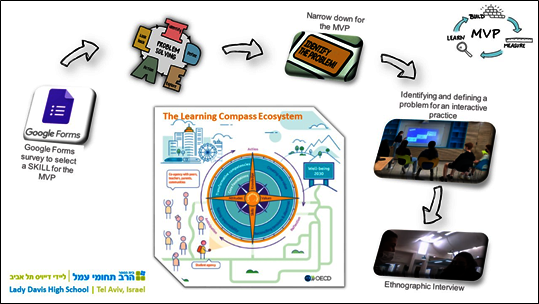

Lady Davis, a public high school in Tel Aviv (1 800 students, Grades 7-12 and 200 teachers), is known for its unique culture of change. It has a focus on pedagogical autonomy for all teachers, which provides a fertile soil for innovative and creative learning projects. During the first COVID-19 lockdown, harnessing the pedagogical changes accelerated by the move to online learning, the leadership team of the school promoted a re-definition of the school’s values.

The result was a set of transformative values which signified the need to create a new normal: from “I must” to “I wish”; from compulsion to choice; from passive to active; from oppressive time to liberating time; from matriculation examinations to maturation processes.

In light of these new values, the Lady Davis team embraced the OECD 2030 Learning Compass as the basis for a pedagogical ecosystem, for new skills-based curriculum and which will be an antidote to national curriculum overload. A design-thinking workshop with the leadership team and selected teachers developed a new concept of schooling – “unleashing the nature of learning” – for both students and teachers, emphasising teacher agency, student agency and co-agency. The focus is on skills development – communication skills, thinking skills and social and emotional skills.

Lean Startup for skills-based curriculum

Time was an important factor in the process of change and Sarah Halperin, the Principal of Lady Davis decided to employ entrepreneurship and agile methods for the development of their new curriculum. The Lean Startup methodology was a “game changer” for the project:

A group of six teachers developed an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) for quick testing of ideas using a build-measure-learn formula.

They started with a survey to select the best skillset for students, and voted overwhelmingly for “problem solving”.

They then broke the problem solving concept into its component parts and decided to focus on defining a problem, the basic yet most difficult part in the process of conceptualising this skill.

A small group of students joined the development team and used the Learning Compass 2030’s AAR (Anticipation-Action-Reflection) cycle to define simple, complex and wicked problems, utilising active learning in a flipped classroom model.

The MVP concluded with an ethnographic interview, a design-thinking method that enabled students and teachers to take a holistic approach and deepen the relevance and the importance of the skill development to their agency.

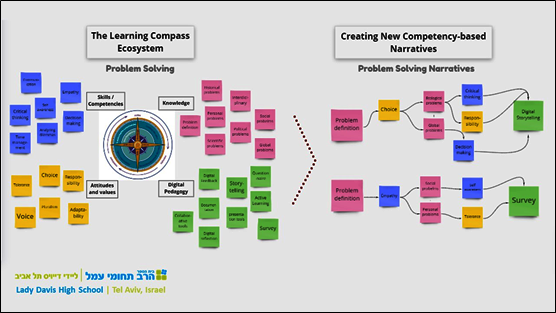

New school culture: Co-agency and collaboration

The success of the MVP helped the Lady Davis team develop a pedagogical model based on the Learning Compass ecosystem for skills-based curriculum. To the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values they added “digital pedagogy”, which includes:

This learning model begins with creative brainstorming that supports an interconnected pedagogical frame. This method allows developers to connect interdisciplinary views and define the interplay between different components. It also enables developers to create diverse narratives that further refine the learning modules.

Lady Davis High School is now introducing skills-based curriculum stems from the ecosystem of the Learning Compass. This new direction will gradually replace parts of the traditional national curriculum. Their philosophy of change is aligned to Buckminster Fuller’s maxim that “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

Source: OECD (2019[57]), Conceptual learning framework: Learning Compass 2030; The OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030 School Networks: Guy Levi, Digital curriculum developer, Lady Davis High School, Tel Aviv, Israel.

In a study of teachers’ exemplarity, Vivienne Collinson (2012[98]) identified sources of teacher attitudes and values, the most quoted being:

Teachers interviewed for her study identified two additional sources of values and attitudes: philosophy/ religion (as a source during adulthood, not simply from family and close associates during childhood) and intensive, post-certification professional development over a period of time. The study highlights the important role of teacher professional development on values: “well-designed professional development may be able to help teachers surface, articulate, understand, and synthesise their own values into a coherent worldview and to appreciate how their values and attitudes affect their work and those whose lives they influence” (Collinson, 2012[98]).

While consolidated research has shown that parental backgrounds (e.g. their social, economic and cultural capital) as well as the home environments (e.g. books at home, safe and secure environment) can affect their children’s learning and well-being, the actual activities they are engaged in, as well as their beliefs and behaviours at home, can also make a difference either positively or negatively. For example, excessive demands from parents and/or parental pressure to help their children succeed in school, which may seem natural and well meaning, can take a toll on children’s academic performance and well-being.

Parental attitudes and values associated with student learning outcomes

All parents can make a difference for their children and play an important role in their children's development of attitudes and values. For example, In the PISA global competence analyses introduced in Chapter 2, a positive association was found between parents’ attitudes towards immigrants and those of their children across all 14 countries that collected data from the parents’ questionnaire. This suggests that parents can play important and complementary roles in developing a positive intercultural and global understanding among adolescents. Parents can transmit not only knowledge about global issues but also attitudes and values; as role models, showing interest in and understanding other cultures, demonstrating tolerance towards those who are different from them and awareness of global issues that affect us all.

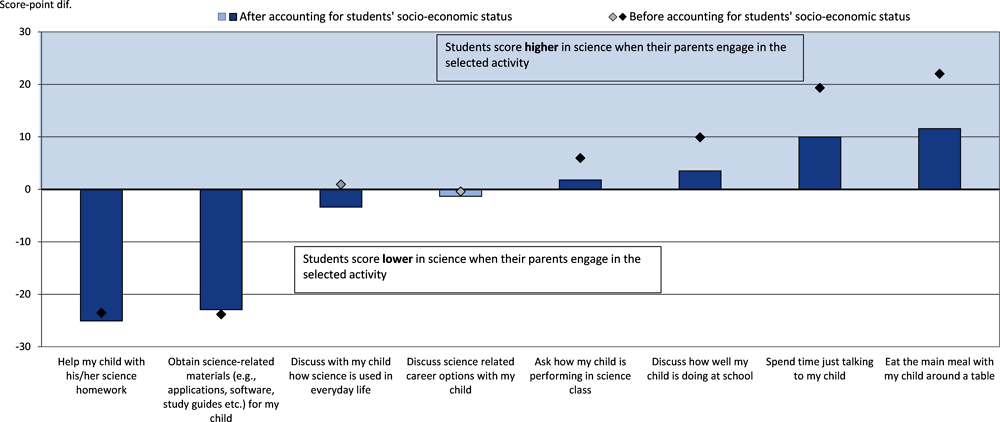

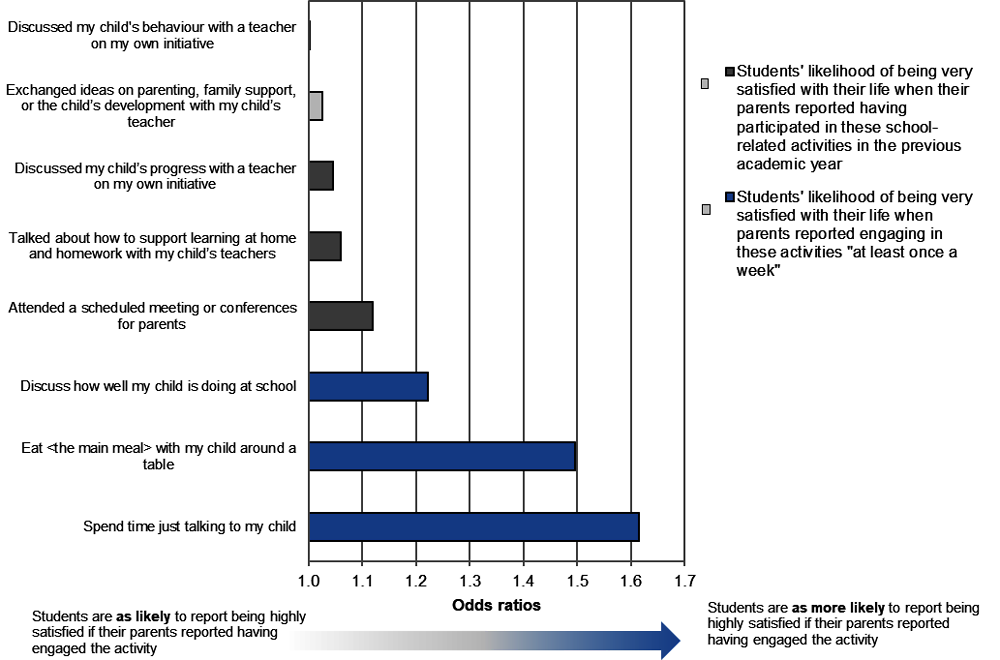

In PISA 2015, parental involvement in their children’s education and lives were found to be positively related to their performance in science (OECD, 2017[99]). Not all forms of engagement are equal, however. Figure 3.3 shows that parental activities that may not necessarily be school-specific, such as eating the main meal with the child around a table or simply spending time talking to their child are also positively associated with students’ higher performance in science. On the other hand, more direct support related to science learning such as helping with homework, obtaining science-related materials or discussing how science relates to everyday life has shown negative associations (OECD, 2017[99]).

This suggests that parents’ knowledge about a subject and support to their children in this subject-specific area may not be as relevant for their children’s performance as some of the more routine actions that are rooted in parents’ values and attitudes, such as valuing an enriching parent-child relationship, considering it important to spend time or eat together, and caring for how their children are doing in school and in life.

Research shows the importance of parents supporting their children at home with homework when they are young, but adolescents and pre-adolescents seem to benefit more from different types of parental support as they transition into more autonomous stages of their lives (Fan, 2010[100]; Hill and Tyson, 2009[101]; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2010[102]).

Parental attitudes and values associated with student well-being

The occurrence of these parental routine and relational activities at least once a week has also shown to be positively associated with greater levels of students’ life satisfaction (Figure 3.4). Research has shown the positive effects on children of high expectations combined with responsive and warm parental support (Burns, 2019[103]); (Georgiou, Ioannou and Stavrinides, 2017[104]; Kalimuthu, 2018[105]), but when those expectations are unrealistic, from either parents or teachers, children are likely to suffer.

Parents face enormous pressure to help their children succeed at school, especially as students approach important transitions, such as preparing for entry to university, which often requires that they pass competitive entry examinations. Parents may also have their own high expectations throughout their child’s development about how well they need to achieve in school.

Excessive parental expectations and overly protective attitudes associated with student learning and well-being

Unrealistic curriculum demands may cause teachers to assign some of the content that cannot be covered in the classroom to homework, for example, expecting them to learn by themselves. While homework can be used as a tool to support students’ motivation and achievement, when it is excessive it has a negative impact on students’ mental and physical health (Bempechat, 2004[106]). Excessive study hours can be translated into less time for students to engage in other critical activities for their development, such as sleeping, exercising and having time for socialising with family and friends, and may not necessarily lead to better student learning (Chraif and Anitei, 2012[107]; OECD, 2016[78]).

Parental responses may include a load of additional school-related materials, or over-involvement in helping with homework. This can aggravate school environments already experiencing curriculum overload (OECD, 2020[2]), which in turn leads to homework overload. Homework overload and/or excessive parental expectations can also lead parents to schedule after-school private lessons/tutoring, a practice that is common in Asian countries where a shadow education system has developed (OECD, 2020[2]; Bray, 2007[108]). Specialised tutoring services are common in Korea (hagwons) and in Japan (juku) as well as in parts of Europe. In an effort to boost students’ achievement and their chances of being accepted into prestigious universities, this tutoring can add a substantive load of supplementary demands on the already burdened lives of students and inadvertently lead to negative psychological and educational outcomes (OECD, 2020[2]; Bukowski, 2017[109]).

As mentioned, high parental involvement is positively related to better psychological adjustment and life satisfaction as well as improved general physical health among adult children (Burns, 2019[103]; Fingerman et al., 2012[110]). On the other hand, parents’ unrealistic expectations of their children’s success, coupled with overly protective attitudes can exacerbate the emotional and mental pressure on their children. A recent OECD report shows the uncertain benefits of “helicopter” parenting, i.e. when parents figuratively “hover above” their children to protect them from harm. Children of helicopter parents are less likely to become resilient, show lower levels of psychological well-being and are more likely to experience anxiety and depression, and to engage in risky behaviours such as binge drinking and sexual risk-taking such as among college students (Burns, 2019[103]; Odenweller, Booth-Butterfield and Weber, 2014[111]; Lemoyne and Buchanan, 2011[112]; Segrin et al., 2012[113]; Bendikas, 2010[114]). These students also tend to experience lower academic outcomes, such as lower grades, lower level of engagement at school, as well as lower self‐efficacy and resilience (Burns, 2019[103]; Shaw, 2017[115]).

The issue of intensive parenting or the over-involvement of parents has received much public attention, in particular, with some new terminologies to categorise hyper-parenting especially among (upper) middle class parents, such as “over-parenting” and “tiger parenting”, in addition to “helicopter parenting” (Ulferts, 2020[116]). Since parenting can support or hinder the development of a certain attitudes and values in children based on parents’ own attitudes and values, careful attention, observation and reflection is required on the ecosystemic relationship between parents and children, in particular, when supporting co-agency between the two.

Resilience is an important component in helping individuals reconcile tensions and dilemmas and overcome adversity. The PISA 2018 findings point to academic resilience1; in 64 of 77 countries, the more academically resilient students were those who reported having more support from their parents, having a growth mindset, and experiencing a positive school climate (OECD, 2019[58]).

PISA 2018 has also shown that there are external factors influencing students’ attitudes, such as parents’ emotional support, teachers’ support and school climate (OECD, 2019[117]) This is particularly relevant when students experience the effects of long-standing conflicts, and complex health, environmental and well-being challenges. Bouncing back from loss and defeat is essential for working productively towards solutions. And, thus, it is of particular importance that policy, school and curricula set an explicit goal towards equity and student well-being (OECD, 2021[118]); in particular, for students who may lack parental support, who have lost their parents, who are victims of child abuse or child neglect, or who need to provide care for their parents at the expense of their own learning and well-being.

Attitudes and values towards lifelong learning, starting from early childhood education and care

Positive attitudes and dispositions to learn have crucial relevance for developing a lifelong learning mindset in students. While individual attitudes and dispositions to learn largely develop early in life – starting in the home, and continuing through kindergarten and throughout the schooling years – the benefits carry on into adulthood (Tuckett and Field, 2016[119]). In fact, individuals who have positive learning attitudes are more likely to engage in further learning throughout life (OECD, 2021[120]).

The recent OECD Measuring What Matters for Child Well-Being report states that early caregiving experiences lead children to form internal working models, representing beliefs and expectations they hold about themselves, the social world and relationships (OECD, 2021[121]). Children who feel secure and safe in their environment enjoy higher self-esteem and self-confidence, and are able to self-regulate and be resilient. Insecurely attached children have difficulties self-regulating and managing stress, and are more likely to experience relationship difficulties in adulthood and encounter difficulties in rearing their own children (Howe, 2005[122]).

Early attachment security is found to influence measures of emotional health, self-esteem, agency and self-confidence, ego resilience, and social competence in interactions with peers, teachers, romantic partners and others (Suess and Sroufe, 2005[123]). Attachment security is also an important consideration in treating childhood health and behavioural difficulties and neurodevelopmental disorders (Rees, 2005[124]).

However, issues are often raised for children transitioning from the culture of early childhood education and care to the school culture, which is often moving more towards teacher-centred from child-centred, and more towards academic subject-area focus from interdisciplinary learning and well-being, for example. The OECD analyses on the transition suggest that the focus should be revisiting the vision, purpose and values of schooling and making schools ready for children, not children ready for school (OECD, 2017[125]).

Portugal ensures continuous learning across different levels of education through “clusters”. While the Portuguese curriculum frameworks are organised by age groups (OECD, 2020[2]); these curriculum frameworks can be interwoven by using a coherent theme from early childhood to young adolescence, for example, STE(A)M carefully designed for developmentally age-appropriate practices (Box 3.6).

Preparing students for a complex and unpredictable future is a concern assumed by Alcanena Schools Cluster. A vertical plan for STEM, along with a vertical plan for the development of socio-emotional skills, were designed for 3 to 18-year-olds, so as to complement the development of cognitive and socio-emotional skills. In preschool (3-5-year-olds), children have their first contact with science and technology. Curiosity and willingness to learn are encouraged within the Science XXS project, in partnership with the Life Science Centre. At the age of 3, children also take their first steps into the digital world through robotics and the Digital Kids project.

At primary school (6-9-year olds), students are invited to play the role of scientists for a week at the Life Science Centre, initiating scientific projects and epistemic knowledge. At the age of 10-11, STEM is extended to STEAM, as the schools believe the arts have a fundamental role in unveiling students’ skills, as well as their self-discovery. Thus, combining arts with sciences and technologies is essential at this age. That is the rationale for Alcanena Schools Cluster hosting artistic residencies, where three artists from the cultural association Materiais Diversos, work on voice, movement, philosophy and fine arts in intersection with the core curriculum and the local environment.

From 12 to 18 years, the investigative path gains new breadth to respond to community problems through the establishment of partnerships between higher education institutions and universities and secondary education. Students develop interdisciplinary projects throughout the year. Challenging formal and/or informal learning situations are created to ensure that each student can develop their own potential, learn and assume their ability to transform themselves, the school and the community.

Epistemic knowledge goes hand in hand with interdisciplinary knowledge, with transformative competencies, attitudes, skills and values, with core and local curriculum. All territory is regarded as a source of learning. Therefore, community problems might involve a response to local problems; the presentation of challenges; the relocation of learning “outside the four walls”, where curiosity and critical spirit are stimulated; the integration of technology as a constant, with resilience, empathy and creativity going hand in hand with information literacy and scientific literature. Learning takes place at innovative learning labs, such as the Future Classroom lab; Makerslab; Foodlab; Artslab; in the schoolyard; on a stage; in the mountains; at a factory; or at the Life Science Centre.

“To sum up, our STE(A)M strategy aims to create a sustained STE(A)M ecosystem which is developed in three different ways: at the level of interdisciplinary curriculum implementation; at the level of curriculum design with the creation of new subjects and timetables; at the level of partnerships, with universities, music schools, technological hubs and cultural organisations.”

Source: Presentation by Ana Cohen, Alcanena Schools Cluster (Portugal) Principal at Education, Education 2030 Focus Group 4

Connections of attitudes and values in local and global communities with those of school ethos and aspirations

Community can play a significant role in shaping and reshaping the attitudes and values students aspire to. By encountering new cultures, learning about power (balance and rebalance), and discovering what it means to be a member of a society, students can find their communities to be a powerful source of values and attitudes education (Schultz, 1990[126]). Involving students within communities can be a solution to the long-time dichotomy between theory and practice that has always existed in the educational process (Schön, 1983[127]; Schön, 1987[128]).

Students who have participated in school-sponsored community service programmes describe their service experience as a critical turning point in shaping the direction of their educational programme, as well as of their future vocational choice. The opportunity to encounter the needs of their community in a structured way has helped lend focus to the rigorous study they undertake in their academic programme (Schultz, 1990[126]). Indeed, volunteering and collaborating with external members of society, such as associations or foundations, can provide opportunities to put into practice theoretical learning on values and attitudes.

In the spirit of learning in a wider ecosystem than simply that of the school context, schools are creating programmes and methods to link lessons and school life to post-school life. These approaches promote student autonomy and are designed to build power of choice and positive expectations regarding their school career, professional and personal futures.

The following stories are examples of programmes that link school education to broader, integrated and authentic learning. The competencies, including attitudes and values, learned through such programmes are believed to endure for life after-school. Box 3.7 illustrates how collective impact can be brought out by combining different approaches e.g. curriculum autonomy and flexibility, student profile development and monitoring, pedagogical framework, and collaborative partnerships e.g. among schools, vocational education and training, and higher education institutions.

The Student Profile by the End of Compulsory Schooling (PA) is recognised as a reference for inclusive education and for responding to the challenges of the future. With curricular autonomy and flexibility, schools can build educational responses that lead to the development of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values, based on humanism.

The creation of the PA National Schools Network for sharing best practice allows the promotion of collaborative learning among different educational stakeholders (students, teachers, parents/guardians, companies and others). The network aims to identify and analyse possible solutions or innovative responses to the organisation and functioning of school and curriculum to develop the values, attitudes and transformative competencies that are defined in the Students’ Profile (PA).

Why: The Students’ Profile by the End of Compulsory Schooling (PA) and Curricular Autonomy and Flexibility

How: Network for sharing practice and promoting collaborative learning dynamics between different educational communities. Identification and analysis of possible solutions and innovative responses for the organisation and functioning of the school and the curriculum in order to develop values, attitudes and transformative competences defined in PA

The PA network focuses on ensuring support to:

The Portuguese Schools Network defined the next steps:

interaction between students from the eight schools of the network: providing learning experiences based on the curriculum;

interaction between teachers from the eight schools of the network: providing immersive and collaborative experiences;

approaching and co-operating with higher education institutions to develop more robust investigation/action research about teaching and learning practices implemented in the eight schools;

themed forums, webinars and workshops for teachers, students and partners of the eight schools in the network with researchers and experts.

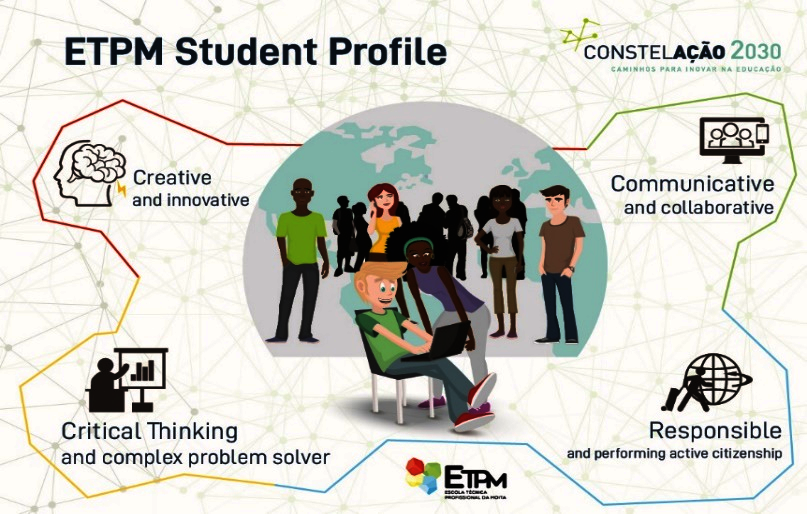

ESCOLA TÉCNICA PROFISSIONAL DA MOITA: Connecting schools through pedagogical framework

Escola Técnica Profissional da Moita (ETPM) provides Level IV vocational secondary education in seven professional areas. With more than 500 students and a pedagogical team of around 50 teachers, ETPM is part of the PA National Schools Network and has been implementing and monitoring its Pedagogical Innovation Framework (Constellation 2030) since 2016. This framework enables the co-construction of students’ and educators’ profiles to meet the current and future demands and challenges of the 21st century at the centre of the school's mission. It consists of the systematisation of interdependent relationships in a set of pedagogical dimensions that are critical for the co-construction of individual profiles, which then guide the school's transformative process.

EPTM highlights the following:

1. The Career Projects programme:

What? The objective is to continue the lifelong learning projects of all students enrolled at ETPM, as they transition from basic education to secondary education and from there to post-school life. The process is monitored by a multidisciplinary pedagogical team of tutors, teachers, psychologists and professionals from partner companies. The Career Project programme is developed with all students during the 3-year cycle of the vocational course.

Why? It is intended to improve, for all students, the power of choice, autonomy, and expectations regarding their school career, and their professional and personal futures. The programme supports them in their development of conscious, flexible life and career projects, subject to change and updating throughout life. The programme promotes more hands on, intentional and meaningful training, enabling the pedagogical team to better understand the student, his/her potential, needs and ambitions.

How? The programme uses methods/practices that provide the foundations for vocational exploration and the consequent decision-making processes, organised in stages and fully integrated with the curriculum of the different subject areas. It builds learning paths that are personalised. The programme establishes a structured and intentional connection between the curriculum, the development of soft skills in the students' profiles and the domains of self-knowledge, self-regulation and self-efficacy.

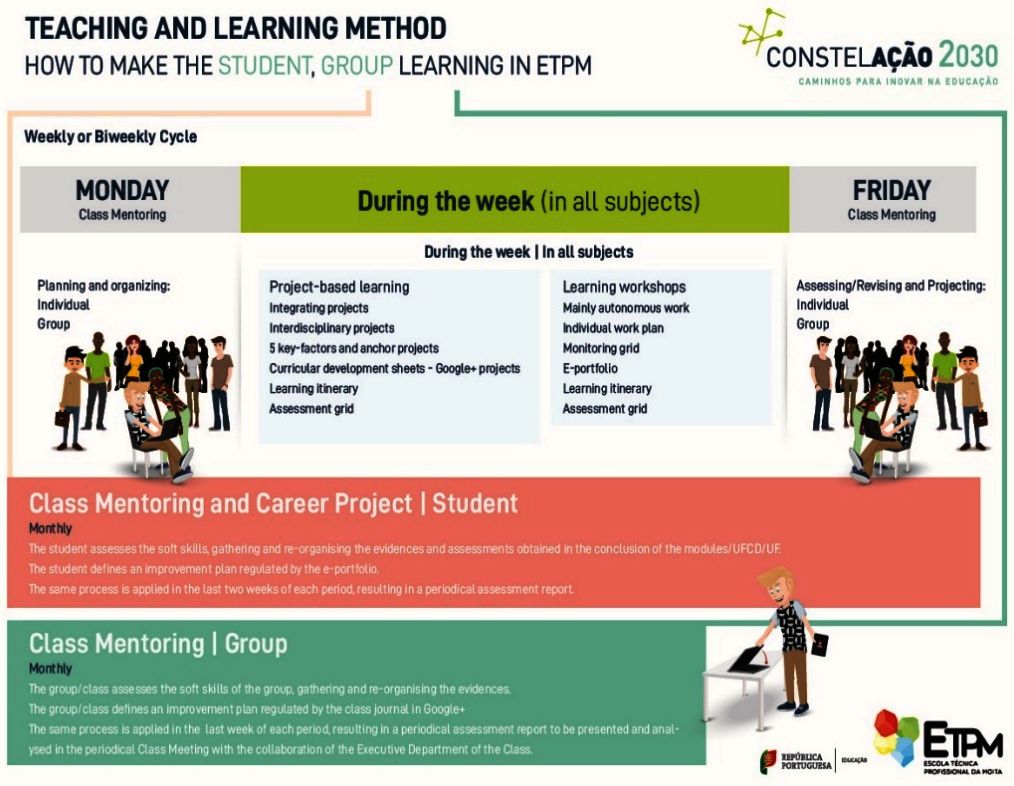

2. Class Mentoring

What? It is a permanent bi-weekly mentoring process developed in all school learning groups. The objective is to establish routines for planning, self-assessment and co-assessment of learning, focused on the development of collaboration, communication, problem solving and critical and creative thinking in students. Class Mentoring is based on learning groups: the tutor (one of the teachers of the pedagogical team) and the students of that learning group. However, groups of students from different classes, courses and years are also formed according to the challenges and projects in which they are engaged. These projects result from different curricular options that promote articulation among students for the design of integrated and multidisciplinary solutions.

Why? These routines aim to regularly mobilise students' effective participation in the options related to curriculum design and implementation, in the defining of learning situations, in the establishment of collaborative learning (peer) routines and in consistent processes of self-assessment and group assessment.

How? Results and impacts

In order to evaluate the results and impacts of the implementation of the framework in the development of the transversal skills provided in the PA on students and educators, ETPM implemented a system of self-assessment and quality assurance with the participation of all educators (principals, teachers, non-teachers, employers and guardians) and students.

Step 1 - Monitoring and self-assessment

Students: weekly, monthly, quarterly and annual self-assessment of the knowledge and skills of the PA and implementation of individual improvement and action plans (Class Tutorials and Notebook);

Student groups: weekly, monthly, quarterly and annual co-evaluation and implementation of improvement and action plans for each learning group (Class Tutorials and group regulation instruments);

Teachers, psychologists and professionals from partner companies: weekly working sessions of pedagogical teams in PDCA logic, promoting the articulation between the assessment of learning and transversal skills developed by students, and self-assessment process of students and groups of students, establishing a final collaborative design between students and teachers of individual and group improvement plans;

Quarterly self-assessment of the evolution of school results. Indicators: success, attendance and dropout rates, inter- and multidisciplinary level approach to curriculum design and implementation. Design and implementation of quarterly and annual improvement plans.

Annual self-assessment of school results obtained by students at the end of course cycle. Indicators: course completion and labour market integration rates, and students continuing studies.

Step 2 – Research and external evaluation

ETPM created and is implementing ProHUB – Research & Innovation for Vocational Education – which works as a research platform, exclusively dedicated to vocational education, located on campus. This platform connects professional education operators, higher education researchers, associations and companies from different professional sectors to develop research, monitoring and evaluation processes for innovative and transformative practices in vocational education.

“Our pedagogical innovation framework is being investigated and analysed, by higher education researchers in the area of educational sciences, educational psychology and neurosciences as well as actions for sharing and reflection that have been developed in other regional and national projects”.

Source: Presentation by Guilherme Rocha, Pedagogical Director of Escola Técnica Profissional da Moita (VET School).

Better engagement in community and conflict management

Embedding values and attitudes in curriculum has consequences for society as well as individuals (Harrison, Morris and Ryan, 2016[129]) by helping students develop a greater awareness of the wider community, and understanding of the impact of their attitudes and actions on that community (Farrer, 2010[130]). A qualitative study in the United States reported that a group of students receiving values education was able to demonstrate a deep understanding of conflict management, as reported by their teachers, education counsellors and administrators (Khoury, 2017[131])

The U.N. Sustainable Development Goals Indicator 4.7.1 is agreed as the “extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education; and (d) student assessment”. As discussed in Chapter 1, the development of attitudes and values (e.g. “respect for people from other countries”) are integral to “global citizenship education” and it is increasingly embedded in different subject learning, while countries/jurisdictions make different choices on the extent to which it will be integrated into curriculum and into which subject areas it is embedded. Furthermore, when it comes to actual classroom practice, careful design is required in order to boost student agency, e.g. ignite a sense of purpose in children and students discovering the global-local continuum. A school in Germany has a school culture based on UNESCO’s four pillars of education and below is one student’s experience of this approach (Box 3.8).

Elias is an 18-year-old student attending Evangelische Schule Berlin Zentrum in Germany. The school culture is based on UNESCO's four pillars of education – learning to know, learning to live together, learning to do, and learning to be – with attitudes and values integral to the pillars.

Elias is an 18-year-old student attending Evangelische Schule Berlin Zentrum in Germany. The school culture is based on UNESCO's four pillars of education – learning to know, learning to live together, learning to do, and learning to be – with attitudes and values integral to the pillars.

Elias' school values the participation of a range of education stakeholders and believes that this collaborative approach enables the school's learning community: students, teachers, parents/ guardians, social workers, facility and operations staff, the school board and external partners to come together to decide what the school community needs; and this is reflected in the topics taught and how the curriculum and timetable are designed.

Prioritising student voice in particular, the school holds “Life & Works Skills” workshops twice a year to listen to students' needs and determine how they can they can offer learning experiences relevant to these needs. Additionally, every student has a tutor – often a teacher – who Elias describes as a person the student can trust and who helps the student get through everyday life. Elias finds it particularly helpful for students who are preparing to graduate to have a tutor on their side. They can go to the tutor with questions, reflect on their progress, and identify areas where they are doing well and where they can improve. Together, students and teachers set goals for the second half of the school year, evaluating learning and anticipating the next steps of development.