2. SME indebtedness and future financing for productive investment

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, public support has helped millions of SMEs worldwide to bridge long periods of depressed revenues and severe liquidity shortage. Whilst the level of SME indebtedness varies across countries, there are growing concerns about an emerging risk of SME default, and the possible impact on SME resilience and future productive investments. This raises more broadly the question of ensuring SMEs can access appropriate and diversified sources of financing in the longer term. Chapter 2 explores the issue of SME indebtedness and funding needs vis-à-vis recent changes in SME finance. It also discusses emerging trends in sustainable finance worldwide that raise new opportunities for SMEs, which are able to improve their environmental, social and governance performance and demonstrate it to investors.

Concerns about small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) indebtedness and future financing capacity will need to be addressed in order to promote recovery

Many SMEs have taken on more debt. Although two or three times more SMEs worldwide have benefitted from non-repayable forms of support than repayable ones (Facebook/OECD/World Bank, 2020[1]), government support has been often in the form of repayable support, which may increase SME debts and, in turn, increase default risk.

Before the crisis, SME and entrepreneurship (SME&E) financing conditions were broadly favourable. Generally, more favourable economic conditions meant that many SMEs were able to self-fund through own profits and revenues. In addition, access to bank lending was easier due to historically low interest rates and alternative sources, including equity funding and asset-based finance, which had become more widespread (OECD, 2020[2]).

In the wake of the crisis, bank finance has remained affordable and venture capital, after an initial drop, has recorded historical highs. The venture capital (VC) industry has shown exceptional resilience, benefitting from business opportunities brought by the pandemic.

Other alternative sources of financing have been more strongly impacted. Declines are observed in leasing and factoring transactions, as well as in online and trade finance.

In addition, lower production, wages and profits could lead to increased default rates by consumers and businesses, which could weaken loss absorption capacities of banks (OECD, 2021[3]) and, in turn, restrict access to finance for SME&Es. Tighter credit constraints may slow the recovery, as SME&Es’ ability to invest is curtailed.

To address SME&E indebtedness risk, government-backed loans often have flexible repayment conditions and countries are increasingly using non-debt support, such as equity and quasi-equity schemes (OECD, 2020[4]; 2021[5]). Banks themselves have also taken initiatives through debt repayment moratoria and flexible and tailored arrangements.

Emerging trends in sustainable finance worldwide are also poised to provide new funding flows. Funds engaged in sustainable investment have grown rapidly and incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations in investment plans is fast becoming mainstream, raising new opportunities for SMEs, which are able to improve their ESG performance and demonstrate it to investors (OECD, 2020[4]).

Moreover, high uncertainty is encouraging precautionary savings (Christensen, Maravalle and Rawdanowicz, 2020[6]), that could serve as a buffer and help restart the economy, although it remains unclear how widespread this has been for SMEs per se and to what extent these could be reassigned to productive investments when economic uncertainties dissipate.

Accessing appropriate sources of finance across all stages of their life cycle is critical for SMEs to start, innovate and grow (OECD, 2019[7]; 2020[8]). Conversely, financing constraints can weigh on their investment, business and innovation capacity, and negatively impact their productivity. Addressing the financing issue of SMEs is of particular importance in the way out of the crisis, to ensure they can engage the transformations needed, such as for instance digitalising or greening their processes and products or services.

SMEs combine different forms of funding, both internal (profits and revenues) and external (bank credit, asset-based finance, equity funding, etc.) to support their activities and growth (Figure 2.1). Internal profits and revenues remain their primary source of funding. Bank credit is their primary source of external funding but funding options also differ across firms, e.g. alternative debt for SMEs with lower risk of default but limited return on investment, or equity instruments for innovative ventures with high growth potential and higher return on investment but at higher risk (OECD, 2020[8]).

Typically, SMEs face internal and external barriers in accessing finance, due to a lack of collateral to be provided as guarantees, or insufficient financial skills of owners and managers, e.g. about funding options and alternatives. External market barriers arise from information asymmetries between financial institutions and SMEs, and relatively higher costs for funding institutions to serve SMEs. For some segments of the business population, especially new firms, start-ups and innovative ventures with high growth potential, the above challenges are typically more pronounced (higher uncertainty, more intangible – and difficult to collateralise – assets). The same stand for groups underrepresented in entrepreneurship, such as women, youth, seniors and migrants (OECD/EU, 2017[9]).

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, SME&E financing conditions had eased (OECD, 2019[10]; 2020[2]). After the financial shock of 2008-09, SMEs had restored their profit margins (OECD, 2019[7]). The increasing demand for long-term loans, as opposed to short-term loans, signalled an increased capacity of SMEs to finance liquidity needs with internal resources and was supported by a low interest rate environment and improvements in the investment climate (OECD, 2019[10]).

SMEs and entrepreneurs were able to access lending, along with a broader range of financing instruments. Lending had largely recovered, with interest rates at historical lows, making it easier for small businesses to access credit. Alternative sources, including equity funding and asset-based finance, had become more widespread, offering diverse options to different profiles of firms and investors. The VC market was expanding rapidly in a majority of OECD countries (OECD, 2018[11]; 2020[2]). The online alternative finance market, comprising peer-to-peer lending activities, equity crowdfunding and invoice trading, has grown considerably in many countries, although from low bases (OECD, 2020[8]).

Nevertheless, SMEs continue to remain heavily dependent on self-funding, often based on internally generated revenues. One-third of all SMEs of EU28 countries reported not using any source of external financing at all, instead of relying on internally generated revenues for their growth or ultimately renouncing to grow at all (OECD, 2019[7]). Increasing profit margins could in part explain the sluggish growth in SME loans (OECD, 2019[7]; 2020[8]).

In the run-up to the pandemic, SME lending was on a sluggish growth path, as SMEs turned to internal finance or alternative instruments for financing their needs (OECD, 2020[2]). The rapid expansion of equity markets was still uneven, only serving a small share of the SME population, as signalled by an increase in the average deal tickets, high concentration of VC investments in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector, and high geographical concentration of investments in China and the United States (US) (OECD, 2017[12]). Online finance was also highly concentrated in China, the United Kingdom (UK) and the US, albeit markets also developing fast in many countries (OECD, 2020[8]).

In a climate of general economic slowdown, SME balance sheets have also become less favourable, the rebound in SME profits starting to level off as from 2019 (OECD, 2019[7]).

Bank finance instruments have remained relatively affordable and available during the COVID-19 crisis thus far. In contrast to the 2008-09 global financial crisis, banks are generally better capitalised and resilient, allowing to keep credit flowing. Preliminary evidence suggests that bank lending held up in the first half of 2020 in many areas of the world (OECD, 2020[2]). In some cases, volumes even increased to meet rising demand from small businesses in order to compensate for revenue shortfalls.

VC, after an initial drop, rebounded to historical highs, 2020 being an exceptional year. The pandemic created opportunities, especially for technology companies, to propose solutions that could respond to the shifting needs of businesses, the workforce and customers (TrueBridge, 2021[13]). In the first quarter of 2021, global venture investments reached USD 125 billion, a 94% year-on-year increase (Crunchbase, 2021[14]). In the US, investments remained robust over 2020. The activity was bolstered by strong demand for innovation and digital acceleration amidst the pandemic and regulatory improvements (Wall Street Journal, 2021[15]). In Europe, a survey conducted in October 2020 of VC fund managers and business angels investing in the area, highlighted general optimism regarding the state of business and expectations for the next 12 months (EIF, 2021[16]). Most of them reported that the COVID-19 crisis had a low impact on their investment strategy. Some VC market observers anticipate no shortage of capital for 2021, making start-up endeavours never easier to finance (MIT, 2021[17]; Wall Street Journal, 2021[15]). However, while the VC industry has been resilient, uncertainty led to a concentration of capital within well-established firms, i.e. increased total investments but fewer deals and greater deal ticket. Venture firms focused on supporting their portfolio companies through the emerging pandemic rather than seeking new investment opportunities (Crunchbase, 2021[14]).

Other alternative sources of SME&E finance have suffered more. Declines have been observed in leasing and hire purchases and factoring transactions. Provisions by lessors rose significantly in the first half of 2020, as more lessees were unable to repay their leasing, leading to a significant fall in the operating income of lessors. In addition, the volumes of new leasing businesses declined severely in the second quarter of the year (Leaseurope, 2020[18]), altogether questioning the future profitability of the sector. In Europe, factoring volumes declined by around 6% in the first half of 2020, reflecting decreased client turnover, but the market is expected to rebound as economic growth picks up (FCI, 2020[19]). Sharp drops also occurred in online financial transactions as the sector faces a crisis of this magnitude for the first time.

Online alternative finance could face long-lasting impacts, with consolidation in the sector (OECD, 2020[2]). Smaller players with weaker capital buffers are expected to leave the sector, leading to a more concentrated market, potentially reducing online finance supply for many smaller businesses and limiting progress in financial inclusion. At the same time, the crisis also presents an opportunity for the industry, especially over the longer term. The current circumstances have increased the demand for alternative finance. The ongoing trend of increasing collaboration between financial technology (fintech) companies, banks and other established financial institutions will also likely be strengthened given the growing importance for financial incumbents to provide online services (IMF, 2020[20]).

Trade finance instruments have come under increasing pressure, with a possible drop in demand. As both domestic and international supply chains are under strain, the scope to rely more on inter-firm lending is severely reduced (OECD, 2020[2]). However, as the current crisis may push actors to adopt more digital tools, banks may reduce their traditional reliance on paper-based processes and the inherent back-office staffing costs (ICC, 2020[21]). This development, if it materialises, would likely enable more SMEs to adopt trade finance instruments (OECD, 2021[22]).

At the same time, there is some concern that the breakdown of supply chains may affect trade finance1 (ICC, 2020[21]), in particular since instruments tend to be highly vulnerable to economic downturns (OECD, 2020[23]; 2021[22]).

Backsliding on the diversification of SME financing instruments would reverse a positive trend towards achieving a better balance between bank lending and other financing instruments for SMEs, in line with the G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing (2015[24]) and towards serving the financing needs of a broader SME population.

Going forward, the resilience of the banking and financing sector will be critical. Lower production, lower wages and lower profits could lead to increased default rates by consumers and businesses, which in turn could contribute to increasing debt, defaults on mortgages and downward pressure on real estate prices. Taken together, depressed economic conditions and rising non-performing loans could weaken the loss absorption capacities of banks (OECD, 2021[3]). The contagion could spread further to energy and financial markets. For instance, as output slowed down in 2020, oil prices already reached their lowest levels in years and commodity prices dropped. Risk aversion has increased in financial markets, with the US 10-year interest rate falling to a record low and equity prices declining sharply.

The sudden and steep drop in sales has exacerbated SME cash flow issues and reduced their profit prospects. The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted SME difficulties in mobilising liquidity and accessing short-term financing solutions and it may also undermine their investment prospects.

Many SMEs have compensated for declining revenues by taking on more debt, often with this enhanced government support. Most preliminary data indicate an increase in loan volumes in the first half of 2020, following an uptick in SME demand (OECD, 2020[2]).

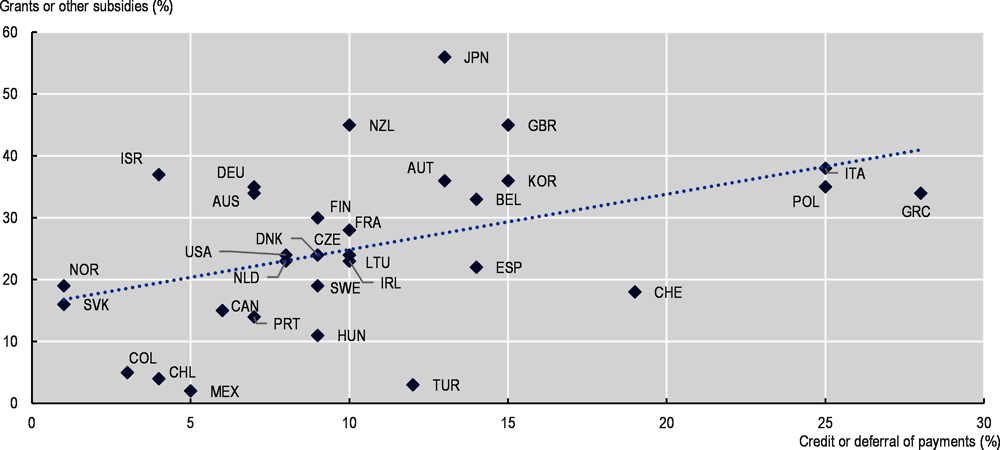

The SME indebtedness risk varies significantly across countries. Few internationally harmonised data are available on the actual uptake of public support by the SME sector. The Facebook/OECD/World Bank survey (2020[1]) partially fills in this evidence gap. The survey focuses on firms with a Facebook page, signalling former – even basic – forms of digitalisation. Results show that SMEs have not been able to access financing schemes in the same way across countries.2 In Greece, Italy and Poland, more than 25% of SMEs (with a Facebook page) have received public support in repayable forms, such as credit or deferral of payments since the beginning of the pandemic. They are therefore more likely to have to repay than in Norway or the Slovak Republic, where they are less than 1% in this case.

While public policies have helped alleviate liquidity constraints, they have also contributed to increasing the risks of SME indebtedness. Public support to SME financing has taken a variety of forms, including repayable and non-repayable ones (Box 2.1). The most common programmes by governments appear to have been debt-related programmes, i.e. loans and loan guarantees. But grant schemes have also been set up in various countries from the first wave of the pandemic and they have become more widely used by governments and more generous in the second half of the year (OECD, 2021[5]). They have also been the most used policy instruments to support research and development (R&D) and innovation by SMEs during the crisis (EC/OECD, 2021[25]). Such schemes show, however, great variety in design (Box 2.1), which could have an impact on the likelihood of some SME populations or entrepreneurs to have accessed non-repayable support.

Debt-generating measures

The most common programmes by governments during the pandemic appears to have been debt-related programmes, i.e. loans and loan guarantees. Many governments have introduced or extended incentives for commercial banks to lend to SMEs. Adjustments in loan guarantee schemes have included increased guaranteeing capacity, an increased proportion of a loan that can be covered by guarantee, reduced processing and guarantee fees, fast-track procedures and reduced documentation requirements, the extension of repayment periods, the extension of eligibility criteria (EBRD, 2020[26]). The OECD survey on COVID-19 government financing support programmes for businesses indicates that, in December 2020, public support in OECD countries remained focused on providing loans and loan guarantees, with the total size of programmes differing significantly from several millions of USD to more than USD 500 billion in some cases (OECD, 2020[27]).

Deferral of payment have allowed SMEs to alleviate liquidity pressures but repayments will need to be made. A relatively large number of countries introduced deferrals on corporate and income tax payments (90%), while a smaller share also included the deferral of value added tax (24%) and social security and pension contributions (21%) (EBRD, 2020[26]).

In addition, loan guarantees have been accompanied by direct lending by public institutions. A large number of governments have introduced new public lending facilities, expanding existing schemes, easing the procedures for access or lowering interest rates (OECD, 2021[5]). Canada has introduced a Business Credit Availability Programme, which provides more than CAD10 billion of additional support to businesses experiencing cash flow issues. As part of its USD 2 trillion stimulus package, the US has opened a USD 367 billion no-interest loan scheme for SMEs with fewer than 500 employees, to cover employee salaries, rental costs and other expenses. Japan expanded the amount of its special no-interest loans offered to SMEs with no collateral.

Grants and subsidies

Grant schemes have also been set up in various countries from the first wave of the pandemic, and they became more widely used by governments and more generous in the second half of the year (OECD, 2021[5]). Such schemes show great variety in design, in terms of the population or sectors targeted, in terms of the eligibility criteria and ultimately in terms of the absolute support or face amount of the support provided (Table 2.1). For example, some grant schemes provide a fixed amount to beneficiaries (e.g. Australia, Chile, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand), while others provide support based on the share of revenue lost (e.g. Austria, Denmark, France, Sweden). Some schemes initially target hard-hit sectors and increase gradually the coverage to other sectors and sizes of companies (e.g. Netherlands). Given the broader uptake of these schemes by SMEs, it would be interesting to understand in a more systematic way how these differences in design could have affected the resilience and survival of different types of firms.

Source: EBRD (2020[26]), “State credit guarantee schemes: Supporting SME access to finance amid the Covid-19 crisis”; OECD (2020[27]), “COVID-19 Government Financing Support Programmes for Businesses”, http://www.oecd.org/finance/COVID-19-Government-Financing-Support-Programmes-for-Businesses.pdf; OECD (2021[5]), “One year of SME and entrepreneurship policy responses to COVID-19: Lessons learned to “build back better“”, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/one-year-of-sme-and-entrepreneurship-policy-responses-to-covid-19-lessons-learned-to-build-back-better-9a230220/#blocknotes-d7e2460.

SME survey data actually show that non-repayable forms of support may have been more popular among SMEs than repayable ones (Facebook/OECD/World Bank, 2020[1]). SMEs have been able to combine different forms of support since the beginning of the pandemic (Chapter 1). In countries where they have had greater access to public credit, they also tend to have received more grants or subsidies. Two to three times more SMEs worldwide appear to have benefitted from non-repayable forms of support than repayable ones. In particular, 56% of SMEs (with a Facebook page) in Japan have received grants and subsidies, as compared to 13% of them that got credit and deferrals of payment. Likewise, 45% of SMEs in New Zealand and the UK have received non-repayable support, for 10% and 15% of them respectively getting repayable support.

While bankruptcy may be a greater risk for smaller firms (Chapter 1), the risk of indebtedness is likely to be higher among larger SMEs. The empirical analysis conducted in Chapter 1 shows a size effect on the likelihood of SMEs to get credits but no effect on their uptake of grants. In other words, the largest SMEs have accessed extra credits more often than smaller ones and could be more at risk of loan default in the future.

To address the risk of SME over-indebtedness, government-backed loans often have flexible repayment conditions to help SMEs and entrepreneurs avoid default during the crisis. Banks themselves have also taken a number of initiatives to support SMEs, namely through debt repayment moratoria (sometimes backed by governments, sometimes on banks’ initiative), delayed payments and flexible and tailored arrangements.

As part of longer-term solutions, governments are increasingly using non-debt support, such as grants, equity and quasi-equity schemes and hybrid instruments (see also Box 2.1). During the renewed lockdown and containment measures in the autumn of 2020, these grant schemes became more widely used and were made more generous, reflecting the increasingly challenging financial situation of SMEs, especially in hard-hit sectors, and increasing recognition of the importance of avoiding SME over-indebtedness. In addition, some countries used grants as a proactive means to support recovery. Ireland, for instance, introduced a new grant scheme in August 2020 that aimed to allow SMEs to restart and reopen. In July 2020, Israel announced a grant scheme for small businesses whereby SMEs can get a ILS-1 000 grant to acquire a fibre optic Internet connection3 (OECD, 2021[5]).

Likewise, some governments are providing convertible loans, which allow a loan to be converted to equity if a borrower is unable to repay it. This type of instrument is beneficial for borrower SMEs as well as for lending banks. SMEs are able to have liquidity at zero interest, companies’ growth potential is not impacted and banks have the opportunity to recoup the capital in the medium and long terms. The Future Fund in the UK has set up convertible loans from GBP 250 000 for SMEs. To be eligible, SMEs need to meet some conditions such as a minimum of GBP 250 000 previously raised in equity investment (British Business Bank, 2020) (OECD, 2020[2]).

The use of equity instruments has several advantages over debt instruments and offers better prospects for SMEs to invest and grow once the recovery sets in. In particular, the use of equity over debt reduces the leverage ratio, which in turn increases the credit rating and lowers the costs of borrowing and the probability of default. In addition, equity instruments lend themselves to co-investments from the private sector, thereby enabling more funds to be channelled towards SMEs (OECD, 2020). Nonetheless, equity instruments often have limited take-up (with the exception of high-potential start-ups and mid-sized firms), since SME owners are often reluctant to weaken their ownership and give investors voting rights. Barriers also arise from a lack of familiarity with equity instruments or high transaction costs.

High uncertainty is encouraging precautionary savings that could also serve as a buffer and help restart the economy, provided the business environment becomes favourable to risk-taking. When customers were asked to stay home and shops and businesses to close doors, final demand collapsed. Losses of income suffered by entrepreneurs and workers prompted firms and people to reduce consumer spending and pile savings. Firms’ preference went to holding cash to raise buffers and avoid liquidity shortfalls. A February 2021 survey of French micro, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) highlights that cash flow has improved over the past three months and liquidities position has never been perceived more positively since May 2018 when the first MSME survey was launched (BPI France, 2021[28]). The share of MSMEs that have mobilised their government-backed loan (prêt garanti par l’Etat, PGE) has remained limited (23%), claims being essentially motivated by the creation of precautionary liquidities.4 By the same token, bank deposits of non-financial corporations have increased rapidly in Japan, the US and many European countries, far above the average growth rates observed over the past five years (Christensen, Maravalle and Rawdanowicz, 2020[6]). Deposits of households have increased as well but to a smaller extent. In contrast, during the global financial crisis, corporate deposits declined with the credit crunch and households’ deposits increased at a smaller rate. It remains however unclear if precautionary savings were more the fact of larger corporations than SMEs and to what extent these liquidity reserves could be reassigned in due time to productive investments.

Looking ahead, there is a growing trend towards sustainable finance worldwide, including through recovery packages

Funds flowing into sustainable investment have grown, with over USD 30 trillion of assets worldwide incorporating some level of environmental, social and governance (ESG) consideration (OECD, 2020[48]). In fact, ESG investing is becoming increasingly mainstream, as financial institutions seek to green their products, portfolios and businesses, including SMEs and entrepreneurs, shifting their business models to align with the green transition. This growth has been spurred by shifts in demand from across the finance ecosystem, driven both by the pursuit of traditional financial value and by the pursuit of non-financial, values-driven outcomes.

SME&Es, however, face a number of challenges to accessing sustainable finance. On the demand side, barriers include a lack of awareness of financial opportunities, the need for more affordable and long-term patient capital, a lack of investor readiness and difficulties in meeting reporting requirements and externalities that may be positive for society, with private returns being less than socially optimal. Supply-side barriers include information asymmetries between financial institutions and SMEs, a limited range of sustainable financing products, insufficient diversity of financial institutions with an appetite for sustainable investments and the “niche” nature of green markets, which result in the incompatibility of investors’ and entrepreneurs’ ideals and objectives (OECD, 2013[17]). SMEs and entrepreneurs need to be enabled to access this financing in order to play their part in the environmental transition.

References

[28] BPI France (2021), Barometre PME Fevrier 2021. Impact de la crise sur la situation financière et le financement des entreprises, https://lelab.bpifrance.fr/enquetes/barometre-pme-fevrier-2021-impact-de-la-crise-sur-la-situation-financiere-et-le-financement-des-entreprises (accessed on 23 March 2021).

[6] Christensen, A., A. Maravalle and L. Rawdanowicz (2020), “The increase in bank deposits during the COVID-19 crisis: Possible drivers and implications”, Ecoscope, https://oecdecoscope.blog/2020/12/10/the-increase-in-bank-deposits-during-the-covid-19-crisis-possible-drivers-and-implications/.

[14] Crunchbase (2021), “Global venture funding hits all-time record high $125B in Q1 2021”, https://news.crunchbase.com/news/global-venture-hits-an-all-time-high-in-q1-2021-a-record-125-billion-funding/ (accessed on 11 May 2021).

[26] EBRD (2020), “State credit guarantee schemes: Supporting SME access to finance amid the Covid-19 crisis”.

[25] EC/OECD (2021), SMEs: Policies Tackling COVID-19, STI Policy Compass, https://stip.oecd.org/covid/target-groups/TG31 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

[16] EIF (2021), “EIF Venture Capital, Private Equity Mid-Market & Business Angels Surveys 2020: Market sentiment – COVID-19 impact – Policy measures”, EIF Working Paper, https://www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif_working_paper_2021_71.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2021).

[1] Facebook/OECD/World Bank (2020), Future of Business Survey.

[19] FCI (2020), “Press release: EU factoring turnover figures in the first half of 2020”, https://fci.nl/en/news/press-release-eu-factoring-turnover-figures-first-half-2020.

[24] G20/OECD (2015), “G20/OECD High-level principles on SME financing”, http://www.oecd.org/finance/G20-OECD-High-Level-Principles-on-SME-Financing.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

[21] ICC (2020), Trade Finance and COVID-19: Priming the Market to Drive a Rapid Economic Recovery, International Chamber of Commerce, https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/05/icc-trade-financing-covid19.pdf.

[20] IMF (2020), The Promise of Fintech: Financial Inclusion in the Post COVID-19 Era, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/DP/2020/English/PFFIEA.ashx.

[18] Leaseurope (2020), Leaseurope Index Q1 2020, https://www.leaseurope.org/_flysystem/s3?file=2020-06/Leaseurope%20Index%20Q1%202020_Public.pdf.

[17] MIT (2021), “With optimism running high in venture capital, 4 trends to watch”, MIT Management Sloan School, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/optimism-running-high-venture-capital-4-trends-to-watch (accessed on 11 May 2021).

[29] OECD (2021), “Annex 1.A. Overview of the different types of SME and entrepreneurship policy support instruments”, in One year of SME and entrepreneurship policy responses to COVID-19: Lessons learned to “build back better””, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/one-year-of-sme-and-entrepreneurship-policy-responses-to-covid-19-lessons-learned-to-build-back-better-9a230220/#annex-d1e2375.

[5] OECD (2021), “One year of SME and entrepreneurship policy responses to COVID-19: Lessons learned to “build back better“”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/one-year-of-sme-and-entrepreneurship-policy-responses-to-covid-19-lessons-learned-to-build-back-better-9a230220/#blocknotes-d7e2460.

[3] OECD (2021), The COVID-19 crisis and banking system resilience: Simulation of losses on nonperforming loans and policy implications, OECD Paris, https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-markets/COVID-19-crisis-and-banking-system-resilience.pdf.

[22] OECD (2021), “Trade finance for SMEs in the digital era”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 24, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e505fe39-en.

[27] OECD (2020), “COVID-19 Government Financing Support Programmes for Businesses”, OECD Paris, http://www.oecd.org/finance/COVID-19-Government-Financing-Support-Programmes-for-Businesses.pdf.

[8] OECD (2020), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2020: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/061fe03d-en.

[4] OECD (2020), OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2020: Sustainable and Resilient Finance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eb61fd29-en.

[2] OECD (2020), “The impact of COVID-19 on SME financing: A special edition of the OECD Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs Scoreboard”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ecd81a65-en.

[23] OECD (2020), “Trade finance in times of crisis: Responses from export credit agencies”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/trade-finance-in-times-of-crisis-responses-from-export-credit-agencies-946a21db/#section-d1e74.

[10] OECD (2019), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2019: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2019-en.

[7] OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/34907e9c-en.

[11] OECD (2018), Entrepreneurship at a Glance: 2018 Highlights, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/sdd/business-stats/EAG-2018-Highlights.pdf.

[12] OECD (2017), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2017-en.

[9] OECD/EU (2017), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2017: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264283602-en.

[13] TrueBridge (2021), “State of the venture capital industry - Market analysis”, https://issuu.com/truebridgecapital/docs/state_of_vc_2021_4.5.21 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

[15] Wall Street Journal (2021), “The venture-capital trends to watch”, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-venture-capital-trends-to-watch-11620578655.

Notes

← 1. Trade finance products typically include intra-firm financing, inter-firm financing or more dedicated tools such as letters of credit, advance payment guarantees, performance bonds and export credit insurance or guarantees (OECD, 2020[23]).

← 2. The OECD survey on COVID-19 government financing support programmes for businesses that has been conducted with the jurisdictions in charge of administrating the same programmes also stresses wide variances in programme usage and access across countries and between programmes within countries. Respondents estimate that programmes were used more than expected, largely because of a demand from SMEs that were unable to access other financing channels.

← 3. See https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3838519,00.html.

← 4. 59% of the companies that obtained the PGE loan would use the maximum term to repay it, i.e. 6 years, 9% expect to pay it back in full as early as 2021 and 8% of MSME managers fear a non-repayment of the PGE, a proportion that is increasing regularly. More than half of executives report an increase in their company’s debt levels during the crisis. This increase was more than 50% for 15% of them.