Chapter 3. Greece’s financing for development

This chapter considers how international and national commitments drive the volume and allocations of Greece’s official development assistance (ODA). It also explores Greece’s other financing efforts in support of the 2030 Agenda. Greece has maintained its commitment to development co-operation during the economic and migration crises. The economic recession saw Greece’s ODA drop to USD 190 million in 2013, representing just 0.10% of gross national income. Since the ODA budget was cut in 2009, the main components of Greece’s bilateral aid have been in-donor refugee costs and scholarships. In the wake of the economic crisis, Greece has adopted a pragmatic approach to its multilateral assistance. The country seeks to meet its commitments to EU institutions and other multilateral organisations. Although Greece recognises the private sector’s potential contribution to sustainable development, it has not set a clear approach to attracting finance beyond ODA.

Overall volume of official development assistance

Greece has maintained its commitment to development co-operation during the economic and migration crises. The economic recession saw Greece’s ODA drop to USD 190 million in 2013, representing just 0.10% of gross national income. This is the lowest amount of ODA provided by Greece since joining the DAC in 1999. Greece’s statistical reporting conforms to OECD DAC guidelines, although it has recently reported no expenditure on other official flows and negative private flows.

Greece has increased its ODA in response to the refugee crisis

As a member of the European Union (EU), Greece has agreed to reach 0.7% of official development assistance (ODA) as a share of gross national income (GNI) by 2030. However, the government has not clearly stated the target ODA level it wants to achieve or how it will do so. The Ministry of Finance has signalled its intention to reinstate the country’s efforts to reach the target of 0.7% once the economy has recovered.

The 2018 state budget is the last submitted under Greece’s macroeconomic adjustment programme. The OECD Economic Survey of Greece projects that gross domestic product growth will rise to 2.3% in 2019 as the economy recovers, the strongest increase since the onset of the economic crisis (OECD, 2018a). This positive momentum may offer Greece the space to increase its expenditure on development co-operation.

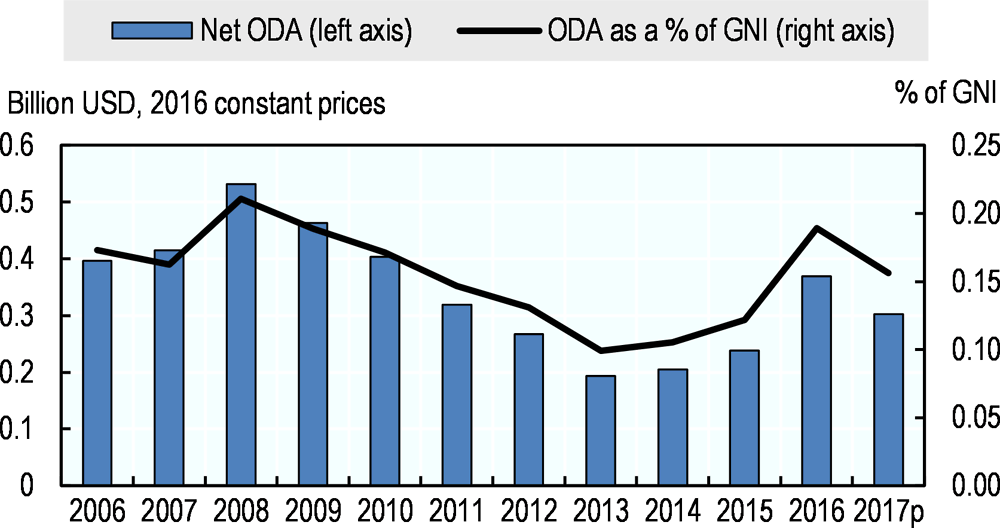

Greek ODA flows have traditionally been volatile, and ODA has fluctuated considerably since the 2011 peer review (OECD, 2013) (Figure 3.1). As the economic recession intensified, Greece instituted significant budget cuts. Its ODA dropped from USD 525 million (0.21% of GNI) in 2008 to a low of USD 191 million (0.10%) in 2013 (2016 constant prices). Greece’s ODA subsequently recovered as the country responded to the migration crisis and the need to support refugees. Despite these crises, Greece has maintained its commitment to development co-operation.

In 2016, Greece provided USD 368.5 million in net ODA, representing 0.19% of GNI and a 56.4% increase in real terms since 2015. Preliminary figures indicate that Greece’s ODA fell to USD 310 million in constant prices in 2017 (0.16% of GNI), partly owing to lower expenditure on in-donor refugee costs. Greece ranks 25th among the 30 DAC members in terms of ODA as a percentage of GNI (ODA/GNI), and 26th in ODA volume (OECD, 2018b).

Reporting conforms to OECD rules, but there is room for improvement

Greece reports all of its ODA expenditure through the DAC statistics and is one of ten OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members rated “fair”. Areas for improvement include its descriptive fields, ODA eligibility and reported channel names (OECD, 2018c). The country has not responded to the DAC forward-spending surveys. In addition, it has reported no expenditure on other official flows since 2008 and private flows since 2014.

In the spirit of reaching common ground, Greece was an active participant in the DAC Temporary Working Group on Refugees and Migrants. It adopted the Clarifications to the Statistical Reporting Directives on in-donor refugee costs issued in 2017 (OECD, 2017), although it is working on fully adapting its methods and data collection.

Bilateral ODA allocations

Since the ODA budget was cut in 2009, the main components of Greece’s bilateral aid have been in-donor refugee costs and scholarships. Greece is most likely to be under-reporting its expenditure on refugees. Greece’s share of bilateral ODA targeted towards gender and the environment is low by DAC standards.

Bilateral ODA mostly targets in-donor refugee costs

Albania, Greece’s neighbour in the Western Balkans, has traditionally been the largest recipient of Greece’s assistance. In 2009, Greece spent 52% of its bilateral ODA in the Balkans, principally in the form of scholarships and imputed student costs to build capacity in partner countries. Several ministries and foundations offer scholarships. However, until recently, Greece had not taken action to assess the impact of its scholarship programme.

As Balkan countries prepared to accede to the European Union, Greece’s focus began to shift to Middle Eastern countries. Thus, although bilateral ODA increased in 2015 because of the refugee crisis, only 8.51% of the total went to the Balkans.

Prior to the onset of the economic crisis, 7.8% of bilateral ODA over 2002-06 was channelled to and through NGOs. In 2007, mounting questions regarding several projects funded by the Directorate General of International Development Cooperation-Hellenic Aid of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DG Hellenic Aid) led to stopping the calls for proposals, effectively severing ties with NGOs (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018).

As a result of budget cuts stemming from the economic crisis, Greece’s bilateral aid dropped from 44.4% of total ODA in 2008 to 18.3% in 2013. Disbursements were limited to scholarships and imputed student costs, as well as in-donor refugee costs (around USD 16-17 million per year). In 2015, owing to an increase in the number of asylum seekers, Greece spent an additional USD 38 million on in-donor refugee costs, and bilateral ODA rose to 30.1% of total ODA. In 2016, bilateral ODA grew by a further USD 88 million, spurred by the significant increase in the number of refugees, whose costs are managed by line ministries rather than DG Hellenic Aid. There were no bilateral disbursements through civil society organisations, the private sector or partner countries.

In 2016, Greece’s bilateral aid amounted to USD 159.1 million – 43.19% of total ODA. Of this amount, USD 146.6 million covered in-donor refugee costs (92.15% of bilateral ODA and 40% of total ODA); USD 1.78 million (1.1% of bilateral ODA) paid for scholarships; and USD 8 million (5% of bilateral ODA) – a multi-bi contribution – was disbursed through EU institutions to the EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey for the Syrian refugees (Annex B).

While expenditure on in-donor refugee costs has significantly increased since 2014, Greek stakeholders note that substantial under-reporting is likely, given the difficulty of determining the cost of providing services refugees can freely access (e.g. health, education and welfare services, and services paid for by municipalities – such as security, first aid on the islands, and provision of shelter). In 2016, the cost may have exceeded the reported USD 146.6 million.

Greece’s expenditure on cross-cutting issues is low by DAC standards

In 2016, USD 2.9 million of Greece’s bilateral ODA had gender equality and women’s empowerment as a principal or significant objective, representing 25% of Greece’s bilateral allocable ODA, compared to the DAC country average of 36%.

USD 1 million of bilateral ODA supported the environment in 2016, representing 8.5% of Greek bilateral aid, compared to the 2016 DAC country average of 28%; the same percentage was spent on climate change mitigation and adaptation, compared to the DAC country average of 24%.

Multilateral ODA allocations

In the wake of the economic crisis, Greece has adopted a pragmatic approach to its multilateral assistance. The country seeks to meet its commitments – primarily assessed contributions – to EU institutions and other multilateral organisations. Relevant ministries determine which institution to support, and whether voluntary contributions are warranted.

Multilateral co-operation forms a large share of Greece’s ODA

Greece spends a large amount of ODA on multilateral assistance. In 2016, it channelled USD 217.4 million (59% of its ODA) to and through multilaterals, compared with USD 166.9 million in 2015. In 2016, core contributions to EU institutions amounted to USD 191 million, including USD 61.42 million allocated to the European Development Fund (EDF); USD 13 million to United Nations institutions; and USD 5 million to other international organisations or institutions (Annex B).

While allocation of the bilateral co-operation budget is normally managed by Hellenic Aid, allocations to multilateral organisations are made autonomously by relevant line ministries. Each ministry includes the forecasted ODA disbursements in its budget; it determines which institutions to support, and whether to provide voluntary contributions. This approach complicates the visibility, planning and monitoring of multilateral ODA. Moreover, no multi-year planning is in place.

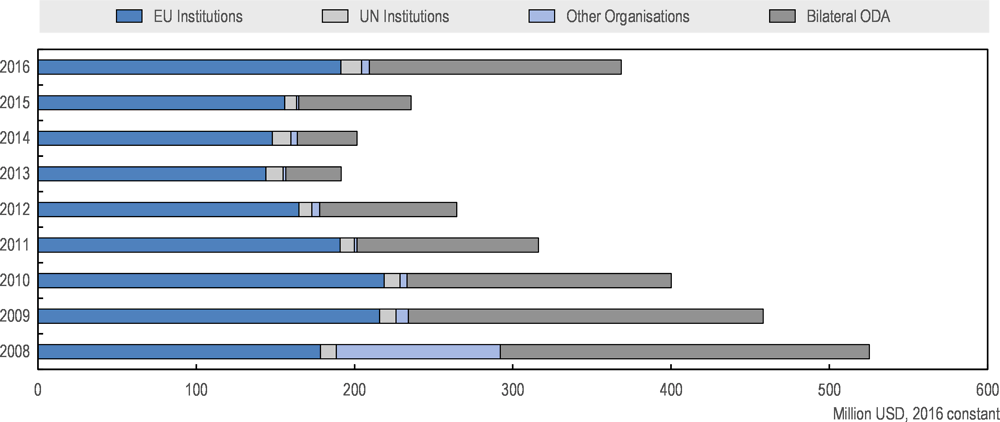

Between 2008 and 2016, the bulk of Greece’s multilateral disbursements was directed to the European Union and the EDF. In 2008, 61% of multilateral ODA was allocated to EU institutions, whereas the share of allocations to the European Union did not drop below 90% of total multilateral aid over 2008-16 (Figure 3.2). Greece’s allocation to other multilaterals organisations, including regional development banks and international and regional organisations, represented a significant share of its multilateral aid until 2008, but has since decreased significantly. The amount disbursed to regional banks, for example, dropped from USD 33.07 million in 2008 to USD 0.56 million in 2012.

Financing for development

Although Greece recognises the private sector’s potential contribution to sustainable development, it has not set a clear approach to attracting finance beyond ODA. DG Hellenic Aid could consider how to leverage the comparative advantage of Greece’s private sector to support sustainable development in developing countries.

Greece should explore catalysing development finance in addition to ODA

DG Hellenic Aid recognises the potential role of the private sector in supporting sustainable development. However, Greece does not currently use ODA as a catalyst to leverage additional sources of development finance, such as private-sector investment, nor does it have the resources to support domestic-resource mobilisation in partner countries. DG Hellenic Aid’s engagement with the private sector is largely limited to one-off events.

DG Hellenic Aid could consider the comparative advantage of Greece’s private sector and engage in a strategic conversation with private-sector representatives about using this comparative advantage to support sustainable development in developing countries. For example, Greece might envisage leveraging its significant maritime expertise and its strong role in global shipping.

References

Government sources

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2018), “Memorandum submitted by the Greek Authorities to the Development Assistance Committee/DAC of the OECD”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Athens.

Other sources

OECD (2018a), OECD Economic Surveys: Greece 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-grc-2018-en.

OECD (2018b), “OECD Development aid stable in 2017 with more sent to poorest countries”, OECD press release, http://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/ODA-2017-complete-data-tables.pdf.

OECD (2018c), “DAC Working Party on Development Finance Statistics, DAC Statistical Reporting Issues in 2017 on flows in 2016”, OECD, Paris, DCD/DAC/STAT(2018)33.

OECD (2017), ‘’Clarifications to the Statistical Reporting Directives On In-Donor Refugee Costs , DAC Temporary Working Group (TWG) on Refugees and Migration, OECD, Paris, DCD/DAC(2017)35/FINAL

OECD (2013), OECD Development Assistance Peer Reviews: Greece 2011, OECD Development Assistance Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264117112-en