Chapter 7. Greece’s humanitarian assistance

This chapter looks at how Greece minimises the impact of shocks and crises, as well as how it works to save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity in crisis and disaster settings. Over the review period, Greek humanitarian aid was limited to one-off assistance and has now almost completely stalled. Despite this, Greece is involved in global and European policy fora to promote more effective humanitarian aid. The Directorate General of International Development Cooperation-Hellenic Aid could use this time to reflect on how Greece could build a distinctive humanitarian comparative advantage in order to make a meaningful contribution when it is able to reactivate its bilateral humanitarian aid. Greece will have to strengthen its own capacity, including in civil protection. It will also need to reinforce its partnerships, notably with its own civil society, which has gained deep humanitarian experience while responding to the crises.

Strategic framework

Over the review period, Greek humanitarian aid was limited to one-off assistance and has now almost completely stalled. In 2016, Greece complemented its significant efforts to manage incoming migration flows with a substantial participation in the humanitarian window of the EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey. Despite its meagre humanitarian capacities, Greece is involved in global and European policy fora to promote more effective humanitarian aid.

Greece has no humanitarian policy, but follows the humanitarian policy landscape

Greek humanitarian aid is rooted in the 1999 law that created Hellenic Aid (Government of Greece, 1999). Different ministries – notably finance, foreign affairs, health and national defence – can provide humanitarian assistance through in-kind aid and civil protection assets. Greece does not have a specific humanitarian policy and (as noted in the previous review) has not clearly defined its humanitarian goals (OECD, 2013). However, Greece participates in humanitarian policy fora, such as the European Council’s Working Party on Humanitarian Aid and Food Aid (COHAFA). At the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, Greece made 21 commitments, many of them relating to migration management and refugee protection. Other World Humanitarian Summit commitments align with Greece’s effort in peace building and conflict prevention (Chapter 1). Greece’s internal policy and practice in receiving migrants broadly aligns with those pledges (Chapter 5).

Humanitarian aid has stalled

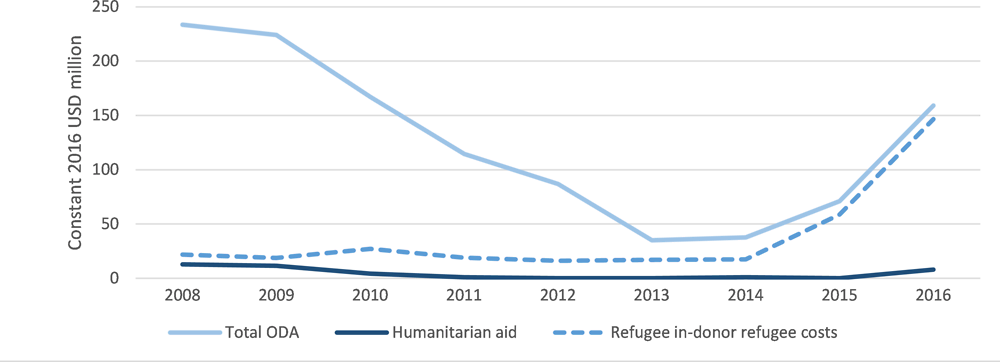

The 1999 decree fixed the target of attributing 25% of Greece’s development assistance funds to humanitarian aid (Government of Greece, 1999). Greece has not reached this target; in 2015-16, its average humanitarian aid stood at 3.5%, compared with the OECD Development Assistance Committee average of 11.9%1 (OECD, 2018). Since 2011, the level of Greek humanitarian aid has remained below USD 1 million (US dollars). The country’s current economic and social situation does not yet allow resuming a stronger humanitarian programme, as in-donor refugee costs still represent the main share of Greek official development assistance (ODA) (Figure 7.1). In 2016, Greece only reported USD 8 million in humanitarian aid to the EU Facility for Refugees. In 2017, it reported a single project totalling USD 360 577 to the humanitarian Financial Tracking System (FTS) managed by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), reflecting the priority accorded to the Syria crisis, which drives many people to seek asylum in Europe by passing through Greece.2

Effective programme design

Because the Directorate General of International Development Cooperation-Hellenic Aid of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DG Hellenic Aid) is not involved in the response to large-scale domestic humanitarian needs, the gap is widening with a very active civil society that is building its expertise and capacity. DG Hellenic Aid could use this time to reflect on how Greece could build a distinctive humanitarian comparative advantage in order to make a meaningful contribution when it is able to reactivate its bilateral humanitarian aid.

A widening gap between government and civil society

Since Greece does not have a specific humanitarian strategy, it relies on its embassy network, the European Union or its operational partners to relay a humanitarian request from an affected country. Mainly because of the migration flows to Europe through Greece that occurred due to the crisis in Syria, the Middle East became a clear priority; since 2016, Greek humanitarian action has been routed to the Syria crisis.

Greece provides its humanitarian aid either directly – through direct financial or in-kind support to the affected country, notably in response to natural disasters – or indirectly – through operational partners, such as UN agencies Greece decides to support or Greek non-governmental organisations (NGOs) selected through a call for proposals. The last call for proposals for humanitarian aid was organised in 2009. Relations with the humanitarian NGOs has been marred by fraud allegations and the ongoing court cases, creating a gap between government and civil society organisations (CSOs), including religious CSOs. This gap is widening, because NGOs are very active in responding to the current domestic humanitarian needs, whereas DG Hellenic Aid is not involved in the response to the domestic migration crisis.

Greece can use this crisis time to build a comparative advantage

When Greece is able to reactivate its humanitarian aid, it will be useful for DG Hellenic Aid to craft a targeted approach. It could focus on a limited area of sectoral expertise in which it could add value to the overall humanitarian community, as when it supported the humanitarian co-ordination in Syria in 2017. As seen with other countries, such a niche approach is a good way for a donor with a modest budget to make a meaningful contribution to a humanitarian response. Greece could use this time where it is not undertaking humanitarian operations to reflect on whether it wants to build such a comparative advantage, what that could be, and which partnerships would be required to take it forward.

Effective delivery, partnerships and instruments

Greece is undergoing simultaneous crises, such as the migration crisis and natural hazards. With limited capacity to cope with immense needs, Greece has relied on adapted EU emergency mechanisms. When crisis needs wane, Greece will have to strengthen its own capacity, including in civil protection. It will also need to reinforce its partnerships, notably with its own civil society, which has gained deep humanitarian experience while responding to the crises.

EU Civil Protection certification should be a priority

Because Greece is subject to a broad range of natural or man-made disasters domestically, it has built a civil protection capacity and is connected to the European Response Coordination Centre. The General Secretariat for Civil Protection under the Ministry of Interior also sends assistance abroad, e.g. to Serbia or Bosnia and Herzegovina during the 2014 floods. The Greek Civil Protection is not yet certified under the EU Civil Protection Mechanism.3 Given its exposure to hazards and its geographic position, upgrading Greece’s national response capacity to EU standards could strengthen its ability to deploy civil protection assets in other countries in the Western Balkan region.

The EU framework represents new opportunities to rebuild partnership with NGOs

DG Hellenic Aid is not involved in the response to domestic humanitarian issues. By contrast, Greek CSOs are thoroughly involved in responding to the emergency needs of migrants on the islands and their longer-term needs on the mainland. In doing so, they have acquired significant experience, co-ordinating with the Greek security apparatus and administration, as well as foreign partners and donors, such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the International Organization for Migration and the European Union.

No Greek NGO had a Framework Partnership Agreement (FPA) with the European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) before the current migration crisis, meaning none of them was able to receive funds from DG ECHO to support their action. Recognising the instrumental role of Greek NGOs in meeting humanitarian needs in Greece, DG ECHO has launched a specific FPA for action within the European Union;4 this procedure has already benefited three Greek NGOs.5 This enhanced national humanitarian expertise could be an opportunity for the Greek Government to rebuild trust between DG Hellenic Aid and the Greek humanitarian NGOs, which would prove useful when Greece is ready to resume a fully fledged humanitarian programme.

Organisation fit for purpose

DG Hellenic Aid could use this time to reflect with relevant stakeholders on the nature of Greece’s added value when its aid volume recovers.

Greece keeps abreast of humanitarian policy development

Only one person follows humanitarian issues within DG Hellenic Aid, mainly focusing on advocacy and international events, notably through the COHAFA. Even without available funds for bilateral humanitarian aid, Greece follows discussions in the global policy arena to keep abreast of evolving humanitarian issues. DG Hellenic Aid could also take the opportunity of its minimal humanitarian operations to liaise with other relevant ministries and CSOs to discuss and start planning for Greece’s potential added value in responding to future crises.

Results, learning and accountability

The Greek Government has created a special service within the Ministry of Digital Policy, Telecommunications and Information to streamline communication about the migration crisis. Establishing an ad-hoc communication line is good practice when government action involves different ministries.

Greece has established a good intergovernmental communication structure

Without a proper humanitarian programme to manage, DG Hellenic Aid does not have results to measure or communicate. However, many other ministries and government departments are involved in responding to the migration crisis. In 2016, the Ministry of Digital Policy, Telecommunications and Information established a Special Secretariat for Crisis Management Communication, which focuses on communicating migration and refugee policy, and regularly issues a public document communicating the government response and providing official figures (Government of Greece, 2018). Such communication materials are useful when many ministries are involved in the crisis response, and when such large-scale crises fuel interdependence between the media and the domestic political agenda (Terlixidou, 2016).

References

Government sources

Government of Greece (2018), Newsletter On the Refugee-Migration Issue, No. 2, 2018, Ministry of Digital Policy, Telecommunication and Media, Special Secretariat for Crisis Management Communication, Athens, http://mindigital.gr/index.php/pliroforiaka-stoixeia/.

Government of Greece (1999), Law 2731/1999, Article 18, Paragraph 1 (Official Gazette 138A/5-7-1999) on the “Regulation of Matters of Bilateral Development Cooperation and Assistance, Non-Governmental Organizations and Other Provisions”, https://nomoi.info/ΦΕΚ-Α-138-1999-σελ-1.html (in Greek).

Other sources

OECD (2018), “Aid at glance by donor, data visualisation by donor”, OECD website, https://public.tableau.com/views/AidAtAGlance/DACmembers?:embed=y&:display_count=no?&:showVizHome=no#1 (accessed 9 August 2018).

OECD (2013), OECD Development Assistance Peer Reviews: Greece 2011, OECD Development Assistance Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264117112-en.

Terlixidou, K. (2016), “L’élaboration de l’agenda politique. La construction des problèmes publics: l’exemple du traitement de la crise migratoire en Grèce de l’été 2015”, research file, unpublished, University of Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris.

Notes

← 1. See ODA distribution by sector, OECD website: https://public.tableau.com/views/AidAtAGlance/DACmembers?%3Aembed=y&%3Adisplay_count=no%3F&%3AshowVizHome=no#1.

← 2. See the FTS managed by OCHA, 2017: https://fts.unocha.org/donors/4547/summary/2017.

← 3. The EU Mechanism for Civil Protection enables co-ordinated assistance from the participating governments to victims of natural and man-made disasters in Europe and elsewhere. The Mechanism currently includes all 28 EU Member States, as well as Iceland, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Turkey: http://ec.europa.eu/echo/what/civil-protection/mechanism_en.

← 4. Since March 2016, the Emergency Support Regulation allows the European Commission to conclude new FPAs to facilitate awarding financing to implement emergency support actions within the European Union: http://dgecho-partners-helpdesk.eu/become_a_partner/esr_fpa/start.

← 5. Médecins du Monde Greece, The Smile of the Child, and Metadrasi: https://ec.europa.eu/echo/sites/echo-site/files/weblistpartners_0718.pdf.