Chapter 4. PRONATEC: governance and coverage

This chapter describes the PRONATEC adult training programme: its several initiatives, its governance structure, the profile of its participants and its geographical coverage. The chapter analyses some of the pros and cons of PRONATEC’s design and implementation. Throughout this analysis, whenever a particular challenge is identified in the design and implementation of the PRONATEC programme, some policy recommendations are suggested, based on best practices internationally.

The “Programa Nacional de Acesso ao Ensino Técnico e Emprego” (PRONATEC) is the most recent adult training programme implemented by the Brazilian Federal government.

4.1. PRONATEC initiatives

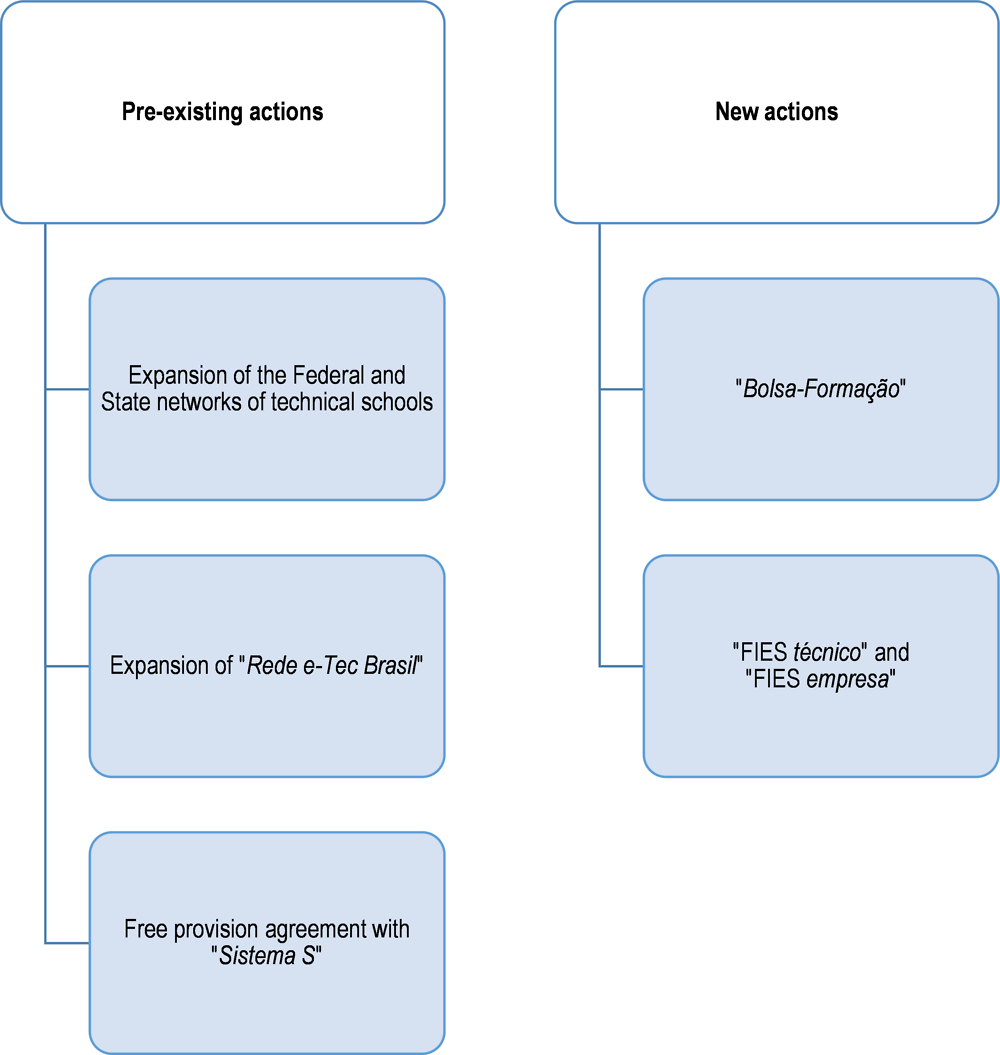

In 2011, the Federal government of Brazil created the “Programa Nacional de Acesso ao Ensino Técnico e Emprego” (National Programme for Access to Technical Education and Employment) or PRONATEC (Lei nr. 12.513, 26/10/2011). PRONATEC was a government-led initiative to expand the offer of vocational education, increase its quality and create incentives for every Brazilian citizen to enrol in free-form short adult training courses. The legal document that institutionalised PRONATEC refers to already existing initiatives, formalising them as Federal law, and launches two new lines of action Figure 4.1.

Amongst the already existing initiatives, the PRONATEC law formalised the national objectives of expanding the Federal and State networks of vocational schools and the number of vocational training courses available in distance learning. In fact, until the end of the 1990s, the Federal network of vocational schools consisted of only 140 establishments across the entire country. From 2003 onwards, successive Federal governments invested in the expansion of this network, delivering an additional 562 establishments by 2014, spread across 512 municipalities and every state (Gomide and Pires, 2013). Similarly, to expand the offer at the state level, in 2007, the Ministry of Education (MEC) created the programme “Brasil Profissionalizado”. This programme expanded the network of state vocational schools. States would sign agreements with the Ministry of Education (called “Termos de compromissos”) for the transfer of Federal funds to state governments that could only be used for the construction and the modernisation of vocational schools, the opening of training laboratories, and for the coaching of instructors and professors. Several investments were also made to expand the offer of vocational courses through distance learning. Also in 2007, MEC launched the programme “Rede e-Tec Brasil” through which it would finance state governments and municipalities, so that those would develop the necessary infra-structures for distance education. All these programmes were brought under the PRONATEC umbrella when the programme was institutionalised in 2011.

The law that institutionalised PRONATEC also revised the agreement of free training provision by technical schools from “Sistema S” (see Box 1.1). It stated that technical schools from “Sistema S” should increase their free training provision and use about two-thirds of their net profits to provide free places to individuals with low earnings and jobseekers. Additionally, the PRONATEC law stated that training courses provided freely by technical schools from “Sistema S” should have a minimum of 160 hours. There was no minimum amount of hours of training before that.

Two new lines of action were foreseen in the PRONATEC law, although only one of them was effectively developed. Since 2001, MEC have been managing a programme called “Fundo de Financiamento Estudantil” or FIES. This consisted in giving scholarships to students wanting to enrol in general tertiary education degrees approved and certified by MEC, but for which enrolment is not free. PRONATEC was meant to expand this initiative so as to provide funding for students wanting to enrol in vocational courses at the level of tertiary education – “FIES técnico” – and firms wanting to provide training to their collaborators – “FIES empresa”. Despite mentioning the initiatives, there were no other documents published after the PRONATEC law to regulate “FIES técnico” and “FIES empresa”, nor to provide further details about their implementation. Nevertheless, the fact that the PRONATEC law contemplated an initiative that would provide funding for employers to organise training activities on-the-job or sponsor their workers to enrol in further training, reveals that the Federal government was conscious of the importance and potential of continuous education and adult training. Furthermore, it also shows that, originally, PRONATEC was not only meant as a programme to increase the equality of opportunities and promote inclusiveness in the Brazilian society. In fact, the emphasis on employer or job-specific training means that the Federal government was also concerned with fulfilling employers’ skill needs with the ultimate aim of improving national productivity and competitiveness.

In practice, however, the main contribution of PRONATEC was to introduce “Bolsa Formação”. This initiative consists in providing free training courses, free access to the necessary teaching material, as well as a subsidy meant to cover the cost of commuting to school and a daily meal. The subsidy is available to individuals at risk of social exclusion and workers who would otherwise hardly engage into further training. Two types of training courses are offered and qualify for the subsidy within PRONATEC: vocational training courses (“Cursos técnicos profissionalizantes”) or short professional qualification courses meant to re-direct workers to a new occupation or to deepen their occupation-specific expertise (“Cursos de formação inicial e continuada” or “Cursos FIC”). The first type of course, hereafter Technical Courses, can last from one to three years or from 800 to 1 200 hours in total. The second type of course, hereafter FIC Courses, can last from three to six months or from 160 to 400 hours in total. While the former targets young individuals, potentially still in education, and leads to a qualification equivalent to lower or upper secondary education, the latter is particularly aimed at individuals who have already left education and integrated the labour market or who are actively looking for a job. FIC courses certificates do not provide any equivalence in terms of educational attainment. In this context, FIC courses are usually considered free-form training courses. Individuals qualifying for a subsidy for the first type of courses receive what is called a “Bolsa formação estudante” (“student training subsidy”) and those qualifying for a subsidy for the second type of courses receive a “Bolsa formação trabalhador” (“worker training subsidy”).

The Federal government, at the time, set up the ambitious objective of training 8 millions of workers in five years through the PRONATEC programme. Ultimately, the goal was to raise the earnings and employability of lower-income segments of the workforce, as well as increase employment in the formal sector. With PRONATEC, it became clear that adult training became again one of the main priorities of the Federal government. One important change with respect to the previous programmes – PLANFOR and PNQ – is that MEC became the main actor responsible for the development, implementation and management of the programme, instead of MTb. There were several reasons behind this change, some of them political. Nonetheless, by giving MEC a central role, PRONATEC became the first Federal adult training programme structured in articulation with the official education system in Brazil.

It is possible to retrieve the evolution of the number of PRONATEC participants until 2018, using the micro dataset of student’s records from “Sistema Nacional de Informações da Educação Profissional e Tecnológica” or SISTEC. SISTEC is the official portal from the Ministry of Education, where all training providers register their training offer – course openings, number of classes, location of classes, number of places available per class, etc. – and students enrol for courses with their personal details.

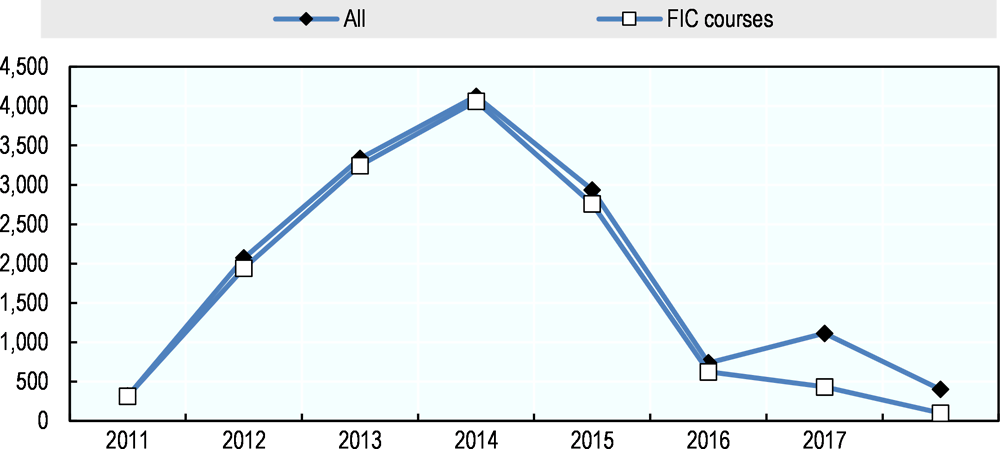

The number of PRONATEC participants each year is displayed in Figure 4.2. Every year, the number of students registered for FIC courses prevailed over the number of students registered for a Technical course (except in 2017). The programme reached high levels of participation in 2013 and 2014, but the number of participants significantly decreased in the following years. Some courses are cancelled for exogenous reasons or lack of participants before starting. Students who enrolled in courses that got cancelled are not taken into account in Figure 3.3. But all other students are accounted for, even those who may have dropped-out.

Given the importance of FIC courses as compared with Technical courses for most years of the programme, PRONATEC is effectively a large-scale adult learning programme. With PRONATEC, the Federal government kept one of the best elements of PNQ: the inter-ministerial collaboration. In fact, as discussed in the previous chapter, the dissemination campaign of PNQ had significantly improved thanks to the collaboration between MTb and MDS. In the governance of PRONATEC, inter-ministerial collaboration became a key element as explained in the following section. On the other hand, PRONATEC is a more centralised programme than PLANFOR and PNQ. Although still involved, lower administrative levels (States, Regional councils, Municipalities) have a less central role in the programme. With PRONATEC, Federal funds are no longer transferred to the State governments, for example, but directly used by MEC to pay training providers. Removing intermediaries in the process contributed to lowering the level of bureaucracy, and mostly, the risk for deviation of public funds.

4.2. PRONATEC governance

Unlike PNQ and PLANFOR, the management of PRONATEC is mostly under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education (MEC), with the collaboration of several ministries and other governing bodies. The collaboration of MEC with other ministries, formalised through a technical cooperation agreement (“Acordo de cooperação técnica”), and with State governments’ departments of education - formalised through terms of commitment (“Termo de compromisso”) - gave rise to several modalities of PRONATEC. Collaborating ministries and State governments’ departments of education (SEEDUCs) are referred to as “requesting partners” (“parceiros demandante”). Each requesting partner can establish, in collaboration with MEC, more than one modality of PRONATEC. Each modality has a different target group and, potentially, offers different types of training courses. Some modalities offer Technical courses, while others offer FIC courses.

Table 4.1. For instance, the Ministry of Labour (MTb) has five different modalities of PRONATEC offering FIC courses. Some modalities are active since 2011, while others were only created later on (such as PRONATEC “Aprendiz” and PRONATEC “ProJovem Trabalhador”). Each modality can have a particular target population. For example, “PRONATEC Mulheres Mil”, created by the Ministry of Social Development (MDS), offers training courses for women in situations of social vulnerability (women suffering from domestic violence, among other cases). Other partners do not target any segment of the population in particular. To illustrate this, the Ministry of Health (MS), with the modality “PRONATEC Saúde”, is open to any worker interested in pursuing training in the health area.

Every year, MEC publishes and updates the catalogues of training courses: “Guia de cursos FIC” for FIC courses and “Catálogo Nacional de Cursos Técnicos” for Technical courses. The catalogues specify the minimum and maximum number of hours of training for each course and provide a short description of the course content, the broad area of study in which that training course fits, and the minimum entry requirements to register for each course. Entry requirements may consist of a minimum age or level of education. Requesting partners consult the catalogues and inform MEC about the specific training needs of their target public. For that purpose, MEC prepared a template file called “Mapa da demanda” (demand map), to be filled and returned by each requesting partner. The information that needs to be provided in these demand maps includes the exact course code being requested, the code of the municipality where the training course should take place, the number of places that are needed for each combination of course and municipality, the course’s area of study, the course’s type (FIC or technical course), and finally, within which PRONATEC modality the course is being requested.

After receiving the demand maps from all the requesting partners of PRONATEC, MEC aggregates the demand for courses to verify whether different partners have requested similar training courses in the same location and if a sufficient number of places has been requested to justify a course opening. Training requests within PRONATEC modalities considered exclusive (marked by “E” in Figure 4.1) cannot be aggregated with requests from other partners. This means that training classes are opened exclusively for the candidates pre-selected by the requesting partner within that modality. Training requests within PRONATEC modalities considered priority (marked with “P” in Figure 4.1) can be aggregated with other demands, but the targeted population by the respective demanding partner should be prioritised when filling the training places available. Other candidates can enrol in these training classes, but only if places remain unfilled by the targeted public Training requests within the remaining PRONATEC modalities (marked by “S” in Figure 4.1, standing for “Shared”) can be freely aggregated with other requests (further details are provided in the next chapter).

After this process, MEC consults with different training providers in each location to understand whether such course openings are feasible. The training providers’ infrastructures and the availability of professors and instructors will determine the feasibility for the subsequent calendar term. This process of consultation with training providers to determine which course openings are feasible is called “pactuação” (further details in the next chapter). Training providers can then register their course openings in the SISTEC portal and start accepting students’ registrations.

Individuals can enrol in training courses (FIC and Technical) by one of three different ways. First, individuals can be selected by a requesting partner who then takes charge of the individuals’ pre-enrolment. Second, from all the remaining vacancies, not already filled by individuals selected by the requesting partners, and for all the vacancies that are not exclusive to a particular target group, individuals can pre-enrol directly through the PRONATEC website (http://pronatec.mec.gov.br). Finally, for Technical courses only, individuals can also apply via the SISUTEC website (http://sisutec.mec.gov.br). When selected by a requesting partner or pre-enrolling via the PRONATEC website, individuals qualify for a training subsidy (“Bolsa formação”).

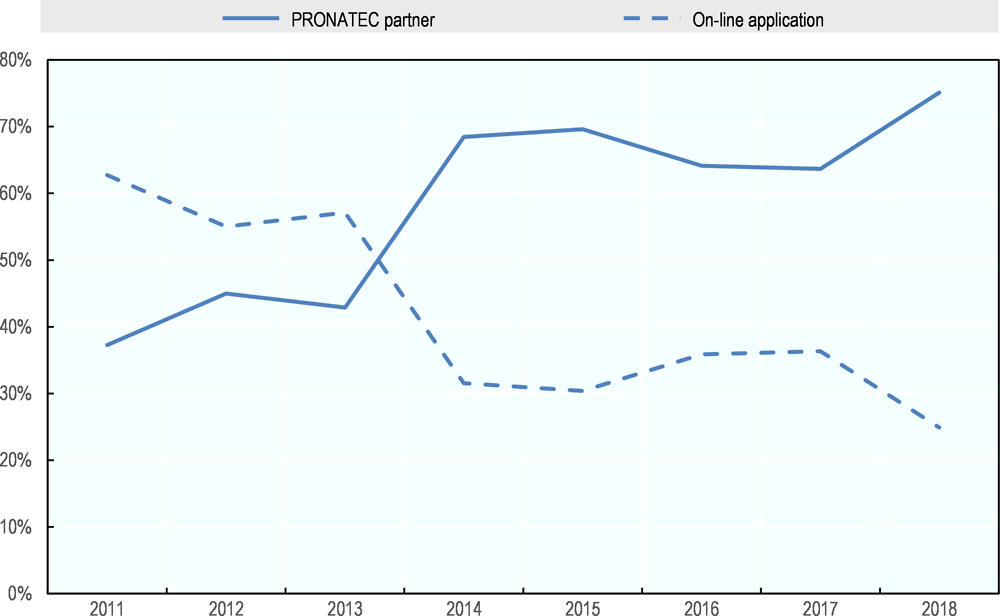

Figure 4.4 displays the number of students that were selected and pre-enrolled by a requesting partner and the number of students that pre-enrolled directly on-line via the PRONATEC website or the SISUTEC portal. Since 2014, most students are selected and pre-enrolled by requesting partners, meaning that most vacancies available for PRONATEC training courses are targeted to particular segments of the population or aimed at fulfilling a determined policy objective.

Inter-ministerial collaboration is one of the most successful aspects of the PRONATEC programme. Thanks to this governance structure and the involvement of several ministries and state departments of education, PRONATEC was able to reach a wide public and to address training needs for all sectors of activity: health, defence, business and administration, industry, tourism, etc. The fact that all ministries coordinated in a unique programme also avoids the duplication of efforts and overlap of different initiatives, with sometimes similar objectives and target public. Furthermore, with a unique programme, several policy objectives, concerning the action of several ministries, can be pursued: democratisation of professional education, promotion of inclusiveness, reduction of poverty, improving labour productivity and firms’ competitiveness, promotion of exports, etc. In this context, PRONATEC’s governance structure should be preserved and should serve as an example to other countries aiming to implement a large-scale adult training programme.

Pre-registration does not guarantee a place into any training course. Requesting partners can eventually select and pre-enrol more individuals than places available for the training courses they requested. Individuals need to confirm their enrolment in person at the training institution. Places for training are then confirmed on a first-come first-served basis by the training provider. Training providers are ultimately responsible for checking individuals’ documentation and making sure that minimum entry requirements are effectively met. Pre-enrolled individuals can be refused into a course by the training provider for lack of entry requirements. Finally, some courses can be cancelled by the training provider if an insufficient number of individuals comes to confirm their pre-enrolment. Further details about the enrolment procedure will be provided in the next chapter.

Figure 4.5 and Figure 4.6 show the number of PRONATEC participants per requesting partner and per modality offering FIC courses. The modality developed by MDS called “PRONATEC Brasil sem miséria” (PRONATEC Brazil without poverty) was the PRONATEC modality that most contributed for the total number of programme participants so far. The second most important modality, in terms of number of participants, although far behind “PRONATEC Brasil sem miséria”, was “PRONATEC Seguro-Desemprego” (PRONATEC unemployment insurance), carried by MTb.

State departments of education have also been largely contributing for the programme by requesting training courses in their municipalities and identifying suitable candidates locally. A quarter of all enrolments in PRONATEC training courses were made through SEEDUCs. Therefore, although PRONATEC gives a less central role to state governments by not transferring them public funds directly, with the established governance structure of PRONATEC, local authorities still have the opportunity to address local training needs.

Although each requesting partner contributes to disseminate information about the programme and their PRONATEC modalities, in particular towards their target public, MEC takes charge of the overall advertising expenses with PRONATEC each year. Figure 4.7 shows that PRONATEC made up the majority of the advertising expenses of that Ministry in 2013 – the year before the programme reached its pick of participation. In fact, PRONATEC was well advertised throughout the country between 2013 and 2014, using mostly street billboards and flyers (Figure 4.8 and Figure 4.9).

However, although MEC’s advertising expenses have been increasing in the last four years, expenses related to PRONATEC almost ceased. Effective and inclusive adult learning systems should start by promoting the benefits of adult learning. In fact, evidence suggests that adults, and in particular low-skilled individuals, are not always able to recognise the need to develop their skills further (OECD, 2018; Windisch, 2015). Public awareness campaigns can come in many forms: media channels (TV, radio, print press, online and social media, etc.), public events (fairs, conferences, workshops, exhibits, etc.), networks of contacts, or even direct mail.

One example that could be followed by the Brazilian government comes from Slovenia, where the Institute for Adult Education has been organising an annual lifelong learning week since 1996, which includes more than 1 500 events, implemented in cooperation with other partners across the country. This has proved very successful in mobilising participation in adult learning programmes, while remaining cost-effective (Box 4.1).

Since 1996, the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education (SIAE), through the Slovenian Lifelong Learning Week (LLW), has been working on implementing a culture of continuous learning by attracting public attention to thousands of inspiring educational, promotional, information and guidance, as well as social and cultural events. The exhaustive list of events can be found in the LLW’s website: https://llw.acs.si/about/.

The LLW has become a festival which annually involves several hundreds of institutions, NGOs, interest groups and other stakeholders. The project has received the financial support of the Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, as well as the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport. Event coordinators complement this public funding with their own resources and financial help from sponsors and donors.

Every year, the LLW committee attributes three types of awards which are disclosed during the national LLW opening ceremony: the individual learning award, the learning group award, and the learning institution award. These awards are meant at rewarding outstanding individuals, groups and institutions who have invested their resources in learning and yielded admirable results, such as personal growth, improving their working and social status, influenced their environment (family, community, neighbourhood, etc.) to learn or who have promoted the knowledge of others. Until 2008, 15 awards were given annually. Since then, for budgetary reasons, the number of awards has lowered, but still five awards have been attributed each year.

Another initiative linked to the LLW is the “Role Models Attract campaign”. LLW award winners record themselves telling their story and how lifelong learning has improved their lives. These video-portraits are then spread to target groups, contributing for the promotion of lifelong learning opportunities.

There is little public information about the overall budget dedicated to PRONATEC. Given that PRONATEC was institutionalised by Law, funding for the programme came directly from the Federal government’s annual budget. According to several press articles, successive Federal government allocated a total amount of BRL 10 billion (EUR 2.32 billion) for the PRONATEC programme between 2011 and 2015. This value does not include Federal funds transferred to technical schools from “Sistema S” within the context of the agreement of free training provision for vulnerable workers. More recently, the Federal government invested about BRL 110 million in 2016 and BRL 41 million in 2017, therefore significantly reducing the amount of public funds dedicated to the PRONATEC programme. This drastic reduction in public investment is the reason behind the fall in PRONATEC advertising expenses, as well as the fall in the number of PRONATEC participants in the recent years.

4.3. The profile of PRONATEC participants

When pre-enrolling candidates in PRONATEC courses, requesting partners are encouraged to submit to MEC a document that describes the methodology adopted in mobilising the targeted public and selecting candidates. The criteria used to sort candidates should be transparent and clearly communicated to the public. Requesting partners can use questionnaires, interviews, cognitive tests or other methods to collect information about potential candidates for their selection process. There is not a standard procedure that applied to all requesting partners and each has the freedom and autonomy to adopt the preferred selection method.

Requesting partners are also required to make sure that candidates meet the minimum entry requirements – in terms of age and educational attainment. When there are no such minimum requirements, requesting partners are asked to consider whether candidates possess the knowledge and experience required to successfully complete the training course or, at least, if it is feasible for them to follow the course content. This assessment of previous knowledge and competencies remains largely at the discretion of the requesting partner’s staff in charge of the selection. For example, for PRONATEC “Seguro Desemprego”, staff at the SINE offices in each region can make that decision. Consequently, the criteria used for that judgement can change from one requesting partner to the other, or even, from one staff at the same SINE’s office to the other, as there are no strict guidelines or procedures to recognise candidates’ previous knowledge and experience.

While there is a decentralised programme in Brazil for the formal recognition of prior learning, this programme – called “Rede CERTIFIC” - was never fully developed and implemented (see Box 4.2). As a consequence, individuals have no means of proving that the experience and knowledge they have accumulated over time is sufficient to attend and successfully complete a specific PRONATEC course. The lack of a well-functioning programme for the formal recognition of prior learning partly explains why assessments of candidates remains largely on requesting partners’ staff’s discretion.

In 2014, the Ministry of Education (MEC) and the Ministry of Labour (MTb) collaborated to create a programme of formal recognition of prior learning called “Rede CERTIFIC” (Portaria SETEC n. 8 de 02/05/2014 and Portaria Interministerial n. 5 de 2/04/2014). The objective of this programme was to formally recognise the knowledge, skills and professional competencies acquired by individuals through their family life, civic engagements, involvement with social partners and professional experience. This formal recognition could lead to a certification with equivalence to a particular educational level.

The formal recognition of prior learning would occur in a decentralised manner, directly through the authorised schools from the “CERTIFIC” network. Federal, state and municipal technical schools would need to apply to become part of the “CERTIFIC” network and be authorised to issue formal certifications based on prior learning. The formal certifications issued by the “Rede CERTIFIC” programme could only be equivalent to vocational education diplomas. The methods to assess the candidates was to be developed directly by staff at the authorised schools.

In the 2014 legal document that creates the programme “Rede CERTIFIC”, MEC and MTb planned to create a national council that would develop the procedure of authorising schools to become part of the CERTIFIC network and general guidance for these schools on how to assess candidates. Ultimately, the responsibility of supervising and monitoring the programme fell on the department of Professional and Technological Education at MEC.

However, there were no further actions from either ministry to develop this programme. In practice, there are very few schools belonging to the “CERTIFIC” network and the number of certificates issued remains very small. The small scale of “Rede CERTIFIC” has prevented it from having a meaningful impact so far.

Older workers are those most likely to benefit from programmes that recognise prior learning and accumulation of experience. In fact, older workers have left formal education long ago and may not possess the formal requirements, qualifications or pre-entry conditions to enrol in a PRONATEC course. Validating and certifying older workers’ skills can help to re-engage them with learning activities.

Figure 4.10 depicts the age distribution of FIC courses participants. Even excluding technical courses and focusing on adult training, younger workers - between 16 and 20 years old - constitute the majority of participants. Participation in FIC courses decreases monotonically with age. Hence, older workers seem to have benefited less from the programme, although they might be the workers at higher risk of exclusion from the labour market due to technological changes.

Developing a full-scale system to recognise prior learning could improve the Brazilian adult learning system and, in particular, the PRONATEC programme in two aspects: (i) it would contribute to engage older workers into adult learning, who are vulnerable of being excluded from the programme based on the lack of entry requirements; and (ii) it would establish a framework to assess candidates’ background when selecting them for PRONATEC courses, avoiding that staff from different ministries, SINE’s offices or state departments of education, apply different criteria or benefit their personal network of family and friends in the access to subsidised training courses. One potential example to follow is the Portuguese programme “Passaporte Qualifica” (Box 4.3).

The programme “Passaporte Qualifica” was launched in March 2017 with the objective of raising the educational level and the formal qualifications of the Portuguese workforce, as well as to engage adult workers in further education. It consists in a programme for the formal recognition of competencies acquired through experience and informal learning.

“Passaporte Qualifica” starts with a web portal where individual workers can create a profile and register all the formal qualifications obtained, as well as all the skills they consider they accumulated throughout their adult life so far. After completing their profile, users of the portal can run a simulator on-line to consult potential and alternative pathways. The simulator will take into account the qualifications and skills acquired so far and suggest potential training courses or modules that, if taken, could lead to a formal certification and the recognition of a particular educational level. Whenever possible, the simulator will suggest more than one possible pathways to a formal certification.

After consulting the different possible pathways generated by the simulator, individuals can choose one of the alternatives and obtain further information about the training modules or credits that have been validated based on their prior experience, and those that are still missing to obtain a formal certification or the recognition of a particular educational level. Individuals can also consult the list of recognised training centres where they could enrol for the missing modules or credits.

The on-line profile can be constantly updated with the new qualifications obtained, modules or credits completed. After all credits are validated, individuals can print out their “Qualifica” passport and present themselves at a “Qualifica” centre to request the formal recognition of their qualification or educational level. There are more than 250 “Qualifica” centres across the country.

The web portal has an extensive list of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and a phone number that can be dialled to obtain further information about the programme. There are also several video tutorials to understand how a profile should be created and how to take the most of the on-line simulator.

Further information can be found following the link https://www.passaportequalifica.gov.pt/.

With the micro data from SISTEC, it is also possible to compare the completion rates and drop-out rates per demographic group and across individual characteristics. Figure 4.11 compares the number of participants in FIC courses by gender, between 2011 and 2018, across all PRONATEC modalities. Women were clearly more highly represented than men. In fact, there are 20 percentage points difference between the participation of men and women. Out of all participants, women were also more likely to enrol through distance learning and women achieved higher completion rates than men. Otherwise, the percentage of students that could not enrol due to course cancellation, because the course was already full or for lack of entry requirements, is not significantly different for men and women. Therefore, there were no apparent differences between men and women in terms of participation in PRONATEC training.

The data also suggests that there were no significant differences between individuals of different ethnical groups. Additionally, individuals with some disability and individuals living in rural communities, did not exhibit a different pattern than the remaining PRONATEC participants. Distance learning was equally attractive and accessible to all demographic segments of the population, since no group in particular seem to have adopted this modality more than others.

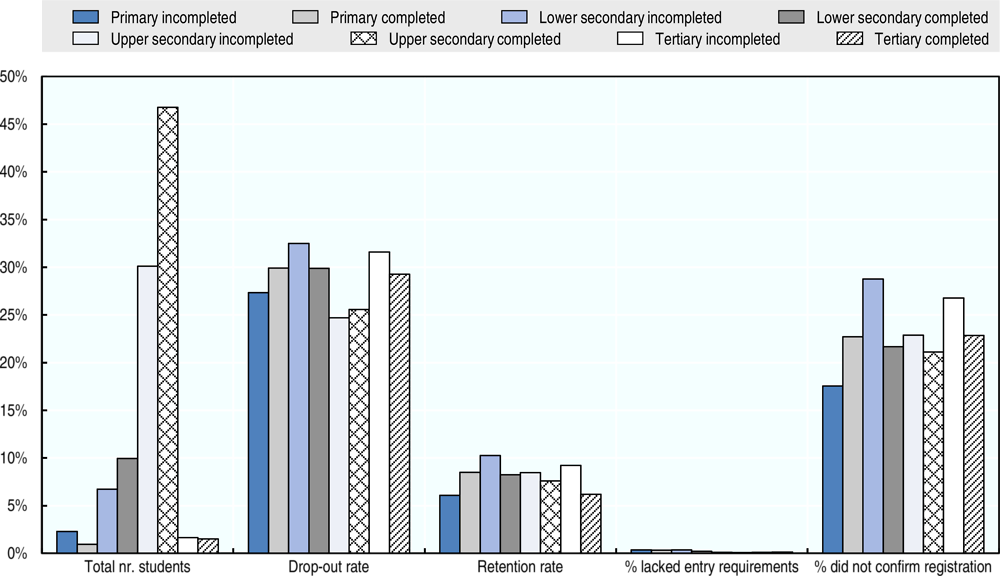

Figure 4.12 shows the distribution of FIC courses participants by educational attainment, also between 2011 and 2018, across all modalities and training courses. The most represented group was that of individuals with completed upper secondary education, followed by those who did not complete upper secondary school. Workers with completed primary education are the least represented amongst FIC courses participants. It is possible that minimum educational attainment as entry condition for a large fraction of training courses, worked against individuals with solely primary education. In fact, pre-enrolled individuals with completed and uncompleted primary education are those more likely to have been prevented from confirming enrolment due to lack of entry requirements. This consideration further supports the idea that developing and implementing a system to recognise prior learning, knowledge and experience is highly recommended (see again Box 4.3). Individuals who initiated but did not complete lower secondary education are those more likely to drop-out, more likely to fail the completion of the course and be retained, and also, more likely not to show up to confirm their enrolment, a potential symptom of lack of motivation.

Figure 4.13 compares the same outcomes for two distinct groups: individuals who were in receipt of unemployment benefits when starting the training course and those who were not. Although one could expect that individuals who received unemployment benefits are those who could benefit the most from training and should be more motivated – for being out of work and not sufficiently long to be discouraged – they exhibit higher drop-out rates, lower completion rates and were more likely not to show up to confirm their pre-enrolment. These could be explained by the fact that individuals who receive unemployment benefits might be low skilled workers who are generally harder to engage into learning activities. Another potential explanation is that enrolment in a PRONATEC training course was made mandatory for individuals who were receiving unemployment benefits for the second time in their working career. These workers may not have been particularly motivated to complete the course they were pre-enrolled into, but may have confirmed their enrolment solely with the purpose of meeting all requirements to receive the unemployment benefit.

Although there were no major differences in outcomes across demographic groups, except for individuals under unemployment benefits and those who aren’t, some segments of the population that were meant to be targeted by PRONATEC may still be underrepresented amongst training participants. This seems to be the case for older workers. This is a segment of the working population that might be particularly vulnerable and at risk of social exclusion, and that would deserve more attention from policy makers to ensure that there is equal opportunity in access to training and labour market opportunities.

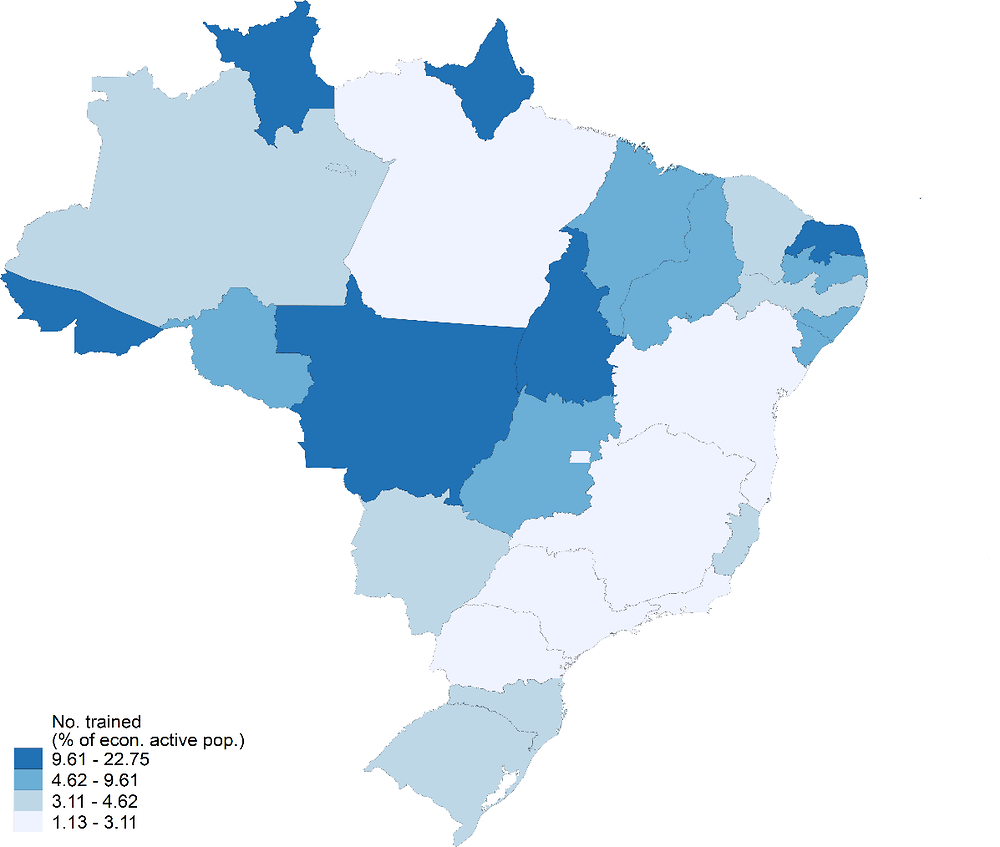

4.4. Geographical coverage

One of the merits of the PRONATEC adult learning programme is its vast geographical coverage, despite the country’s large area, the heterogeneity and diversity of its regions and the existence of remote areas that are hardly connected with urban centres or by any infra-structure. Figure 4.14 shows the number of students who were registered for a PRONATEC FIC course between 2011 and 2018 by state. The number of students enrolled is expressed as a percentage of the economically active population1 in each state and the Federal District. PRONATEC has been particularly active in the states of Acre, Amapá, Mato Grosso, Rio Grande do Norte, Roraima and Tocantins, covering almost 30% of the economically active population. These are all states with a GDP per person lower than USD 10 000 as of 2011, according to official data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics or IBGE (“Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística”). Only the states of Maranhão and Piauí have lower GDP per person. In the richest regions of Brazil, namely Distrito Federal and the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, PRONATEC covered less than 5% of the economically active population. Therefore, PRONATEC seems to have been particularly effective in reaching out to the population living in the poorest areas of Brazil.

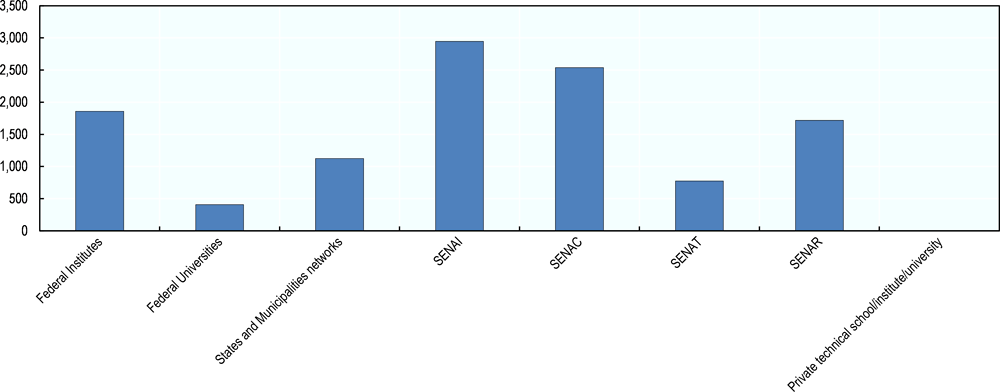

Overall, PRONATEC has covered as much as 4 125 different municipalities in 2014, out of 5 570 in total (Figure 4.15). These figures refer mostly to FIC courses. In 2014, there were PRONATEC FIC course in 4 063 municipalities out of 5 570 across the entire country. However, not all types of training providers contribute equally to spread the offer of PRONATEC courses across the country, and especially, in remote geographical regions.

Figure 4.16 shows the number of municipalities across the country covered by each type of training provider. As will be thoroughly discussed in the next chapter, PRONATEC courses can only be provided by Federal Institutes, state and municipal technical schools, Federal Universities, technical schools from the S-system (SENAI, SENAC, SENAR and SENAT) or private technical schools duly accredited by MEC. Among all of these types of training providers, SENAI and SENAC are particularly well represented geographically, reaching more than 2 500 municipalities each. SENAI and SENAC are closely followed by Federal Institutes, while the lowest coverage goes to private institutions. Technical schools from “Sistema S” have, therefore, a fundamental role in the geographical coverage of the programme. SENAI, for example, holds a network of 555 fixed units and 442 mobile units, through which it can hold FIC courses. The mobile units, in particular, can be transported across the country by truck, train, or even by boat, in order to reach remote municipalities where there are no technical schools and where the infra-structures do not allow individuals to commute easily. These mobile units are particularly well-adapted to the morphology of states like Pará and Amazonas, for example.

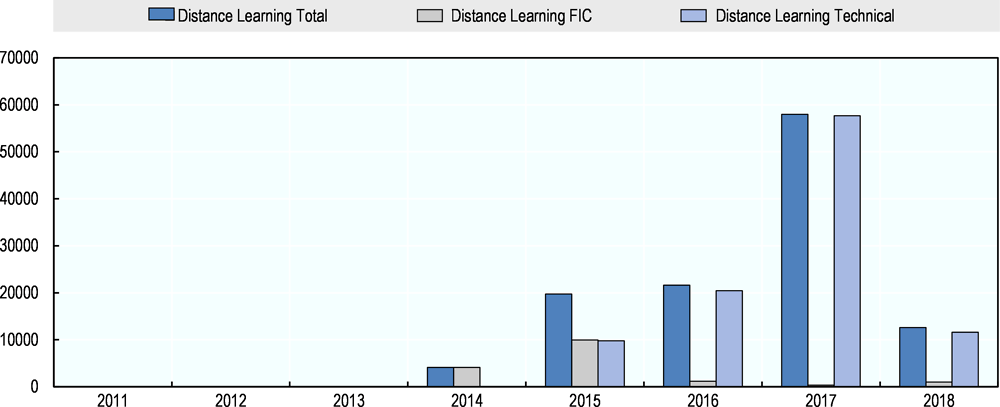

A cost-effective alternative would be to promote the offer of flexible learning opportunities. Training courses available on-line, by correspondence, taking learning materials home and learning remotely without being in regular face-to-face contact with a teacher in the classroom, are some examples of flexible learning opportunities. Training providers who possess the appropriate infra-structure can offer distance learning courses within PRONATEC. However, distance learning has not been really widespread for FIC courses, as suggested by Figure 4.17. Based on SISTEC’s records, students enrolled in training courses through distance learning did not have lower completion rates than students who attended regular training courses in person. Therefore, further efforts should be made by the government to boost the offer of distance learning courses.

Another possibility, which has been exploited in some OECD countries, is to offer training courses in a modular or credit-based format. Modular approaches consist in individuals completing self-contained learning modules that can be combined to eventually gain a full qualification. Individuals could complete one self-contained module at a time, possibly in different times of the year, combining modules from different training providers, potentially at different locations. The Danish adult learning system, for example, strongly relies on such modular approach (OECD, 2018). Individuals working towards a qualification in Labour and Market Training Centres (“Arbejdsmarkedsuddannelse”) can choose from a wide range of training modules, some of which may be organised within the general education system. In Mexico, individuals enrolled in the “Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo” (Model for Life and Work) programme can combine different modules with different topics, some of which are delivered in an on-line platform.

Beyond offering training courses in every region of the country and exhibiting high levels of enrolment everywhere, the successful completion of a training course can also be substantially influenced by local infra-structures. Individuals living in areas of poor transportation infra-structures, for example, may have more difficulties to attend training regularly, waste more of their time commuting from one place to the other, and experience greater physical tiredness at the end of the day. All these factors may substantially affect their ability to successfully complete the training course. This is particularly relevant, given that the value of the training subsidy per hour has been set at a constant rate for all regions of the country (further details on the training subsidy will be provided in the next chapter). This means that individuals living in remote areas, with very little options to commute to school, receive the same subsidy than individuals living in urban areas with a well-developed public transportation system.

The constant value for the PRONATEC training subsidy or “Bolsa Formação” across individuals, regions, training centres and training courses, is one of the biggest limitations in the implementation of the PRONATEC programme. In fact, different individuals have different capacities to save and invest in their own professional development. Individuals with different family situations will also have more or less opportunities to enrol in lifelong learning opportunities. Individuals with kids, for example, may not be able to attend evening courses, unless they are able to hire a babysitter or other services to take care of their children while occupied. Workers living in different regions experience different costs from commuting. The PRONATEC training subsidy should be adjusted accordingly. In fact, if regions are not equally attended by the programme, this could even contribute to widen the gap in economic growth and well-being across different areas of the country.

One argument for keeping the value of the “Bolsa Formação” constant across regions and individuals is that it simplifies the administrative procedure of transferring public funds to training participants. Additionally, differentiating the value of the subsidy across individuals could lead to undesirable situations of discrimination or personal favours. However, there are other ways of avoiding abuses of power and misuse of public funds that would not jeopardise the implementation of the programme.

The government could consider a fixed set of possible values for the “Bolsa Formação” and there could be clearly defined criteria to qualify for each of the different subsidies. As long as the overall procedure is kept transparent, it becomes easier to detect possible frauds and abuses of power. This system of multiple values for the training subsidy - depending on clearly defined observable individual characteristics - could be accompanied with regular audits to PRONATEC partners selecting candidates, schools and participating individuals. The government could set up a computerized management system of the training subsidies attributed, where information about individual participants could be cross-checked with administrative databases on earnings, wealth and the receipt of other social benefits.

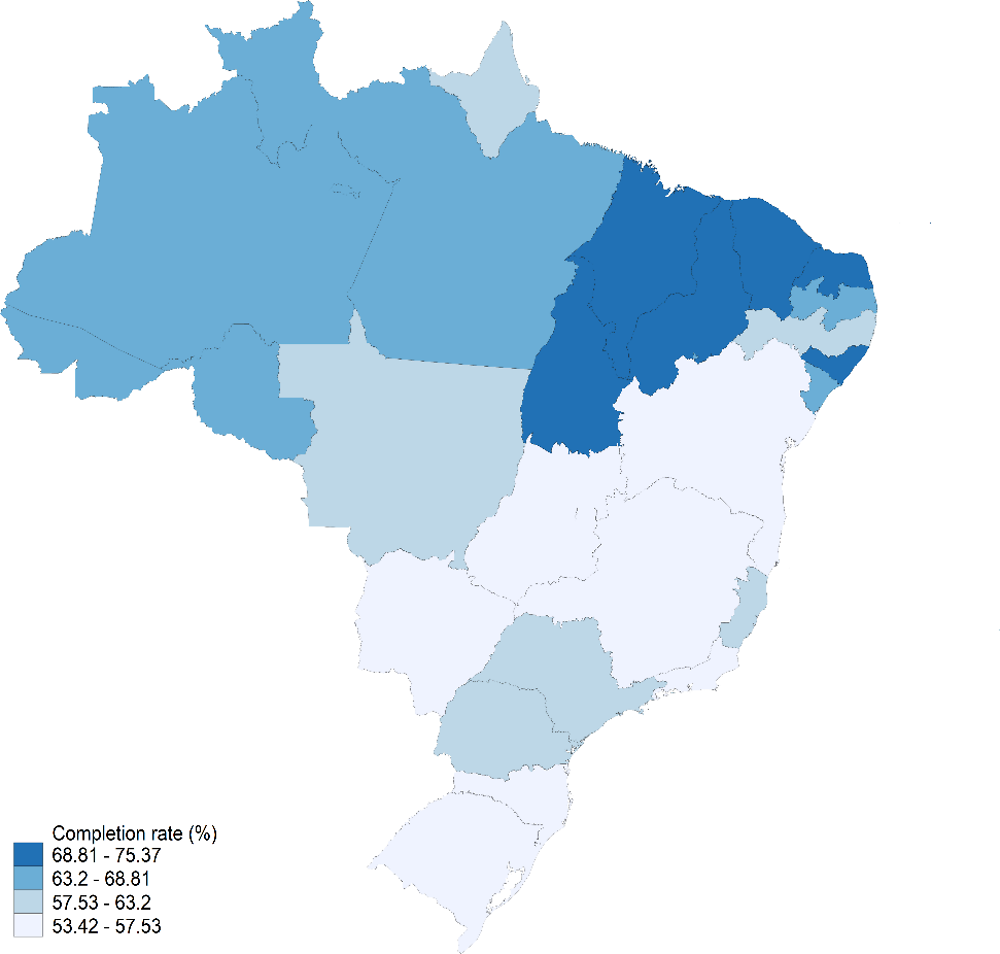

Figure 4.18 and Figure 4.19 represent the completion rate for FIC courses between 2011 and 2018 by state and by municipality. States from the north-east region exhibit the highest completion rates. Alagoas, Ceará, Maranhão, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte and Tocantins all obtained completion rates between 70% and 75% of the total number of students who confirmed their enrolment and effectively started a training course. However, these averages hide significant intra-state variation. Completion rates within one state can easily vary between close to 0% and more than 75%.

Regions that are less densely populated and where some communities are difficult to reach, such as in the states of Acre, Amazonas, Pará and Rondônia, for example, also reached relatively high completion rates, between 60% and 70% of the total number of students who confirmed their enrolment in a training course that effectively started. The lowest completion rates – and the highest dropout rates – can be found in States from the southern and south-eastern regions, such as Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.

Despite its wide geographical reach, the effectiveness of the PRONATEC programme to fulfil specific local demand for training may have been limited. In fact, as previously mentioned, training courses subsidised by PRONATEC need to be selected from the national catalogue published by MEC, “Guia de cursos FIC”. It is possible that in some states, or even municipalities, training needs are not contemplated by courses proposed in the FIC national catalogue. By centrally defining a list of training courses that can be subsidised within the PRONATEC programme, MEC tends to select training courses which will be demanded in all areas of the country, ignoring training courses that might be urgently needed in only a few remote areas of the country. This was the case, for example, in the states of Amazonas and Pará. To overcome this limitation and satisfy the demand for very specific training needs, some states have developed their own adult learning programmes (see the example in Box 4.4).

In 2016, the state government of Pará approved a law that creates the state adult learning programme “Pará Profissional”. The institutionalisation of this programme through a formal law ensures that the programme will continue beyond the specific government that developed it and the successive electoral cycles. This formalisation was put in place so as to maximise the long-term returns of the initiative. The objective of the programme “Pará profissional” is identical to the objectives of PRONATEC, but applied to the municipalities within the state of Pará.

The main contribution of “Pará Profissional” relies on the identification of specific local training needs that are not contemplated by PRONATEC and the nationally defined catalogue of FIC courses. By limiting its scope to one state, communication, coordination and collaboration between members of the state government, municipalities, local schools, social partners and private firms is much facilitated. Together, and under the responsibility of the programme’s coordinators in the state government, partners identify what are the skill needs of each community and whether such needs can be met by the existing local training offer.

For example, one of the skill needs identified by local partners that could not be met by PRONATEC or the existing training offer, consisted of tourist guides for religious routes in the state of Pará. In fact, pilgrims on religious routes are one of the biggest tourist attractions in the state. However, there was no national programme offering training for such specific local skill need. Another example is training courses to learn how to handle latex and incorporate it into other products and with other materials. This is also a very specific need of the region, which exports raw latex to the rest of the country, but could benefit from exporting latex-based products of higher value added.

Once specific local skill needs are identified, the different partners establish a formal collaboration agreement so as to develop a new training course that can fill this skill shortage. Schools or social partners can provide the classroom, other infra-structures and instructors when possible. Private firms can contribute with equipment’s, experienced instructors, or the organisation of practical tutorials and internships. The state government can provide the funds to hire new instructors, purchase missing equipment or rent classroom space if needed. This generates some flexibility in the training location, schedule and content, allowing courses to take place closer to the targeted public and to meet the needs of local communities.

When a free course is opened, a public announcement is made so that anyone in the state can apply for the training course. Staff at the government of Pará collect applications, sort them, select candidates and pre-enrol them into the training courses. Students do not receive any training subsidy, unlike for PRONATEC. Therefore, it is possible that students enrolling for a course provided through “Pará professional” are more motivated and engaged.

But to reduce drop-out rates from the programme, state government staff, together with their partners, always organise an induction session for each course explaining its content, the expected work load, the criteria for successful completion, the occupations for which the course may lead to, the expected employment rate and average earnings in those occupations, among other things. Students are allowed to cancel their enrolment after the induction session if they believe that the course does not meet their expectations. Because this session happens very early in the process, students who cancelled their enrolment after the induction session can still be replaced by other candidates kept on a waiting list. According to staff at the state government of Pará, induction sessions have been very effective in improving the completion rates of training courses offered in the context of “Pará professional”.

The programme has set a target of training 10 000 individuals per year, with a budget of BRL 8 million, and until 2019. This budget was made of only state funds. Nonetheless, further funds can be obtained through private-public partnerships in the organisation of specific training courses.

While this is a promising initiative, the programme is still developing and there is insufficient data yet to assess its merits. For the moment, it remains a low-scale programme and its results may not be easily extrapolated to larger initiatives.

Two considerations can be made out of the example from “Pará professional” (Box 4.4). First, that the organisation of induction sessions prior to the start of a PRONATEC training course, or at the early stages of the training course, might be a useful and costless mechanism of reducing drop-out rates. In fact, further information and career guidance is needed to avoid unrealistic expectations, feelings of frustration and to maximise the potential of the public investment made in the PRONATEC programme. Career guidance, more generally, helps individuals to understand their skill set and development needs, as well as navigating through the available learning opportunities and training courses that would best suit them (OECD, 2018). Examples of career guidance services from other countries are provided in Box 4.5.

Second, it is possible that, by creating incentives for training providers to supply courses that are listed in the national catalogue of FIC courses, but that do not necessarily match urgent local demand for skills, PRONATEC even contributes to misalign training needs and training offered in some regions, in the medium-long term. In fact, training providers may be tempted to invest in infra-structures, equipment and materials that allow them to increase their offer of training courses which are subsidised. To capitalise on such investments, training providers may want to continue offering the same courses for a relatively long time horizon. The next chapter will carefully analyse the alignment of training needs and PRONATEC’s training offer.

To be effective career guidance takes into account timely labour market information and the outputs of skill assessment and anticipation exercises. Career guidance can be delivered by the public employment services (PES), specialised public guidance services, or yet, career guidance websites (OECD, 2018).

In Iceland, social partners and the government are working together in the Education and Training Service Centre to develop career guidance services in cooperation with education providers around the country.

Other countries have developed one-stop-shops where individuals can get all the information they need in one place. For example, the House of Guidance (Maison de l’Orientation) in Luxembourg opened in 2012 following the collective effort of five departments across the Ministries of Education, Labour and Higher Education. The house provides a one-stop-shop for education and labour market orientation. Previously targeted at a younger age group, there has been a greater focus on adult learners since 2017.

Similarly, the project Education Shop (Leerwinkel) in West Flanders (Belgium) is an independent one-stop-shop for advice on educational options and financial support. The project focuses specifically on adults with low education levels, immigrants and detainees.

References

Cassiolato, M. and R. Coutinho Garcia (2014), PRONATEC: múltiplos arranjos e ações para ampliar o acesso à educação profissional, Boletin de Análise Político-Institucional, IPEA. http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/2406/1/TD_1919.pdf.

Gomide, A. and R. Pires (2013), Arranjos institucionais de políticas críticas ao desenvolvimento, Boletim de análise político-institucional, Brasília: IPEA, n. 3. http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/5910/1/BAPI_n03_p71-75_NP_Arranjos_Diest_2013-mar.pdf.

OECD (2018), Getting Skills Right: Future-ready adult learning systems, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Ministério da Educação - Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (2017), Manual de gestão Bolsa-Formação do Programa Nacional de Acesso ao Ensino Técnico e Emprego – PRONATEC, 2ª edição. http://portal.mec.gov.br/docman/marco-2017-pdf/61681-setec-manual-de-gestao-da-bolsa-formacao-pdf/file.

Ministério da Educação - Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (2011), Guia PRONATEC de cursos FIC, 1ª edição. http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/tags/tag/36436-guia-pronatec-de-cursos-fic.

Ministério da Educação - Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (2012), Guia PRONATEC de cursos FIC, 2ª edição. http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/tags/tag/36436-guia-pronatec-de-cursos-fic.

Ministério da Educação - Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (2013), Guia PRONATEC de cursos FIC, 3ª edição. http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/tags/tag/36436-guia-pronatec-de-cursos-fic.

Ministério da Educação - Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (2016), Guia PRONATEC de cursos FIC, 4ª edição. http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/tags/tag/36436-guia-pronatec-de-cursos-fic.

Ministério da Educação – Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica – Diretoria de Articulação e Expansão das Redes de Educação Tecnológica – Coordenação Geral de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica a Distância e Tecnologias Educacionais (2018), Manual do usuário: Registro e confirmação de frequência para Bolsa-Formação, Instituições Públicas e SNA, versão 2.0. http://eadcafe2017.muz.ifsuldeminas.edu.br/pluginfile.php/67/mod_forum/attachment/55247/V2-2018-Manual_do_Usuario_de_Confirmacao_e_Registro_de_Frequencia_para_Bolsa_Formacao%20%281%29.pdf.

PRONATEC: Situações de Matrícula, Versão 35.3, de 13 de Abril de 2015. https://map.mec.gov.br/attachments/63137/Pronatec%20Situa%C3%A7%C3%B5es%20de%20Matr%C3%ADcula%20-%20Anexo%20NI%2066.pdf.

Windisch H. (2015), Adults with low literacy and numeracy skills: a literature review on policy intervention, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 123, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrxnjdd3r5k-en.

Note

← 1. The economically active population includes all individuals in legal age of work that are employed or unemployed and actively looking for a job. It excludes individuals still in education, discouraged unemployed workers who are no longer looking for a job, as well as individuals unable to work.