Chapter 2. Developing a learning culture

The chapter presents diagnostic evidence on adult learning in Flanders, the factors that affect adult learning and specific policies and practices to foster a learning culture. Flanders can develop a learning culture by taking action in seven areas. These are: 1) raising awareness about the importance of adult learning; 2) tailoring adult education provision to the specific needs of adult learners; 3) transforming adult education providers into learning organisations; 4) making higher education more accessible for adult learners; 5) promoting work-based learning in post-secondary education; 6) promoting human resource practices that stimulate a learning culture in the workplace.

Introduction

Why developing a learning culture matters

Learning culture can be defined as the set of beliefs, values and attitudes, and resulting behaviours, favourable towards learning that a group shares (OECD, 2010[1]). A strong learning culture is imperative if a country wishes to thrive in an increasingly complex world. While the precise skills needs of the future are unknown, a strong learning culture ensures that individuals are ready to upgrade their existing skills or acquire new skills to adapt to new challenges and opportunities. For society at large there are economic (e.g. productivity, innovation, economic growth) and social benefits (e.g. well-being, social cohesion). A learning culture needs to be cultivated from an early age and reinforced during the later years. In this chapter, the focus will be on the notion of a learning culture as it relates to adults in Flanders and how much they engage in adult education.

In Flanders, participation in institutionalised adult education is around the OECD average, and low in comparison to Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany, which have the highest rates. This is despite the relatively high average skills levels of Flemish adults in most measures of cognitive skills, such as literacy, numeracy and, to a lesser extent, problem solving in technology-rich environments. Higher participation in adult education could help reduce the significant skill level differences that exist between high and low educated adults, older and younger generations, and natives and migrants (OECD, 2016[2]). It would also help mitigate the risks of skills obsolescence, which is important given that about 60% of the workforce in Flanders are potentially vulnerable to automation (Elliott, 2017[3]). Adult education could also facilitate the transition of adults from low demand to high demand occupations, such as healthcare, and support the integration of immigrants in Flanders (Vlaamse Regering, 2016[4]).

Fostering a learning culture and adult education are priorities for Flanders. In Flanders, long-term strategy Vision 2050 identifies “lifelong learning and a dynamic lifecourse” as one of the seven crucial transitions Flanders has to make in order to become an “inclusive, open, resilient and internationally connected region that creates prosperity and well-being for its citizens in a smart, innovative and sustainable manner” by 2050 (Vlaamse Regering, 2017[5]). As mentioned in Chapter 1, adult education has also been highlighted in PACT 2020 (VESOC, 2009[6]), the VESOC agreement on the reform of education and training incentives (Vlaamse Regering and SERV, 2017[7]), the Policy Paper Education and Training by the Department of Education (Crevits, 2014[8]), and the Strategic Literacy Plan (Vlaamse Regering, 2017[9]).

Overview of chapter

This chapter analyses available data and evidence on the participation in and quality of adult education in Flanders. It then proceeds to discuss the factors that influence adult education quality and participation. Next, it explores relevant general policies and practices to raise the quality of and participation in adult education, existing specific policies and practices of adult education in Flanders, and policies and practices from other countries that could be of interest for Flanders. The chapter concludes with recommendations of how to improve adult education.

Adult learning in Flanders

Context of adult learning in Flanders

Adults can learn through formal adult education, non-formal adult education and informal adult learning opportunities. Formal adult education occurs in a structured environment and leads to a nationally recognised formal qualification. Non-formal adult education also occurs in a structured environment, but may only lead to a diploma or certificate that is recognised by a sector or professional body. Informal adult learning is unstructured and does not lead to any qualification. When referring to formal and non-formal education, the term “adult education” will be used. When referring to formal, non-formal education and informal learning, the more encompassing term “adult learning” will be used. For more information, (Box 2.1).

In Flanders, the majority of adults in formal education attend Centres for Adult Education (Centra voor Volwassenonderwijs, CAE). Centres for Adult Education provide education in a wide range of skills such as technical skills and languages. The courses are modular and flexible (e.g. evening courses). After completing a module, the learner receives a partial certificate, and after completing an entire programme, the learner receives a formal certificate recognised by the Flemish government. The CAEs also give adults the opportunity to obtain a secondary education degree through “second chance education” (Tweedekansonderwijs, TKO). CAEs also have specific teacher training programmes, which from September 2019 will be moved to the university colleges (hogescholen). Centres for Adult Basic Education (Centra voor Basiseducatie, CABE) provide courses in basic skills (e.g. numeracy, digital skills) and Dutch as a second language.

Universities and university colleges (hogescholen) allow adult learners to combine work and study by providing a limited number of special tracks (werktrajecten) in some study fields (Box 2.5). Higher education institutions also offer advanced bachelor and advanced master’s degrees and postgraduate certificates, which allow adults with work experience to continue professional education. Through a credit contract, adult learners can take up specific courses from bachelor or masters programmes without enrolling on the entire programme. Currently, adult learners can pursue post-secondary VET to obtain an associate degree (Hoger beroepsonderwijs, Higher Vocational Education, HBO5) in the Centres for Adult Education; however, from September 2019 HBO5 will be moved to the university colleges, which will bring more adult learners into higher education institutions.

The Flemish Agency for Entrepreneurial Training Syntra (Vlaams Agentschap voor Ondernemingsvorming Syntra Vlaanderen, Syntra) provides apprenticeships (leertijd) for 15 to 25 year-olds. Apprentices usually spend four days a week in a company and one day a week in a Syntra training centre. The programme can lead to both a professional qualification and a diploma of secondary education, if the learner completes the general education component.

In terms of non-formal adult learning, the main training providers are employers. Syntra offers non-formal education, such as entrepreneurial training, sectoral training and additional specialised training. The Flemish Public Employment Services (VDAB) organises vocational training for job seekers. This training often leads to a professional qualification. VDAB also has specific programmes for target groups such as individual vocational training (Individuele beroepsopleiding, IBO), work experience placements, induction work placements, explorative internships and education qualifying training programmes (Onderwijskwalificerend opleidingstraject, OKOT). (See Chapter 6 on financing for more details). There are also many training courses provided by employers through the financing of sectoral covenants. (See Chapter 3 on skills imbalances, for more details). Concerning liberal arts adult education, part-time art education (Deeltijds kunstonderwijs, DKO) allows adults to enrol in art programmes in the academies for visual arts and the academies for music, drama and dance. Socio-cultural adult education is organised by various providers: associations, movements and training institutions (adult education institutes/training plus centres and national training institutions) (Eurydice, 2015[10]).

Box 2.1. Survey of Adults Skills (PIAAC): Measures of formal education, non-formal education and informal leaning

The Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) is an international survey conducted in over 40 countries and measures the key cognitive and workplace skills needed for individuals to participate in society and for economies to prosper.

Formal education: Formal education is provided in schools, colleges, universities or other educational institutions and leads to a certification that is taken up in the national educational classification.

Non-formal education: Non-formal education is defined as any organised and sustained educational activities that do not correspond exactly to the above definition of formal education. Non-formal education may therefore take place both within and outside educational institutions, and cater to persons of all ages. In the context of the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), non-formal education and learning refers to:

-

Courses through open and distance education. This covers courses which are similar to face-to-face courses, but take place via postal correspondence or electronic media, linking instructors/teachers/tutors or students who are not together in a classroom.

-

Organised sessions for on-the-job training or training by supervisors or co-workers. This type of training is characterised by planned periods of training, instruction or practical experience, using normal tools of work. It is usually organised by the employer to facilitate adaptation of (new) staff. It may include general training about the company and specific job-related instructions (safety and health hazards, working practices). It includes, for instance, organised training or instruction by management, supervisors or co-workers to help the respondent do his or her job better or to introduce him/her to new tasks. It can also take place in the presence of a tutor.

-

Seminars or workshops.

-

Courses or private lessons. This can refer to any course, regardless of the purpose (work or non-work).

Informal learning: Informal learning relates to typically unstructured, often unintentional, learning activities that do not lead to certification. In the workplace, this is a more or less an automatic by product of the regular production process of a firm. The Survey of Adult Skills asks several questions about types of informal learning: In your own job, how often do you learn new work-related things from co-workers or supervisors? How often does your job involve learning-by-doing from the tasks you perform?

Source: OECD (2011[12]), PIAAC Conceptual Framework of the Background Questionnaire Main Survey, www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/PIAAC(2011_11)MS_BQ_ConceptualFramework_1%20Dec%202011.pdf.

Adult learning in Flanders

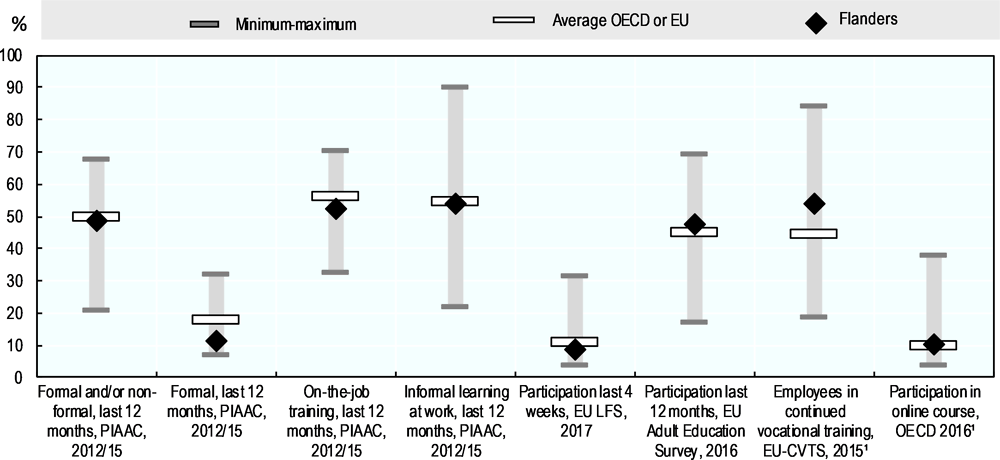

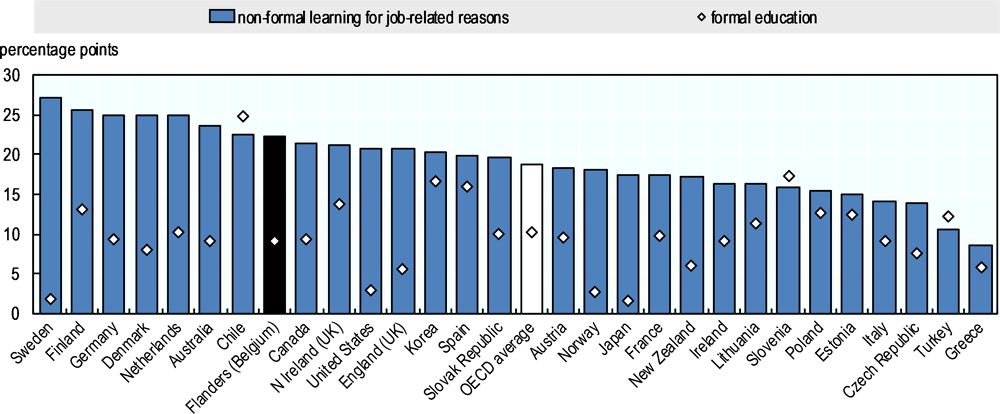

The level of adult learning in Flanders is around average in comparison with other countries. While Flanders has relatively high levels of skills on most measures of cognitive skills, the share of adults participating in different forms of adult learning, such as formal education1, non-formal education2, and informal learning, is around the OECD (PIAAC) average or EU average (OECD, 2016[2]). Similarly, participation levels are also around average in on-the-job training and online courses, but slightly above average in continued vocational training.

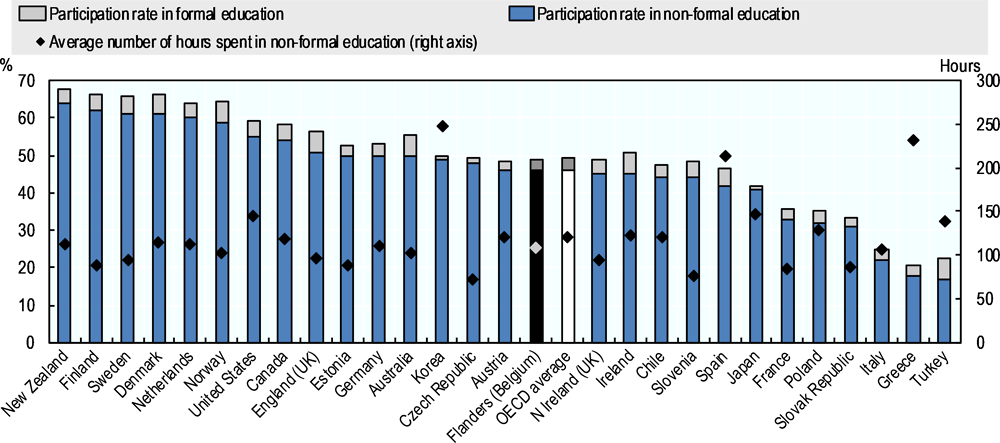

Flanders has an average participation rate in non-formal and formal education and average intensity, which refers to the average number of hours spent. This differs from countries like Spain, where the participation rate is comparable to Flanders, but the number of hours is significantly higher (OECD, 2016[2]). Other countries, such as Canada and the United States, have both higher participation rates and higher number of hours than the average. While having a higher intensity in adult education does not guarantee a better quality of adult education, it does provide adults with more time within a learning environment where acquisition of new skills can take place.

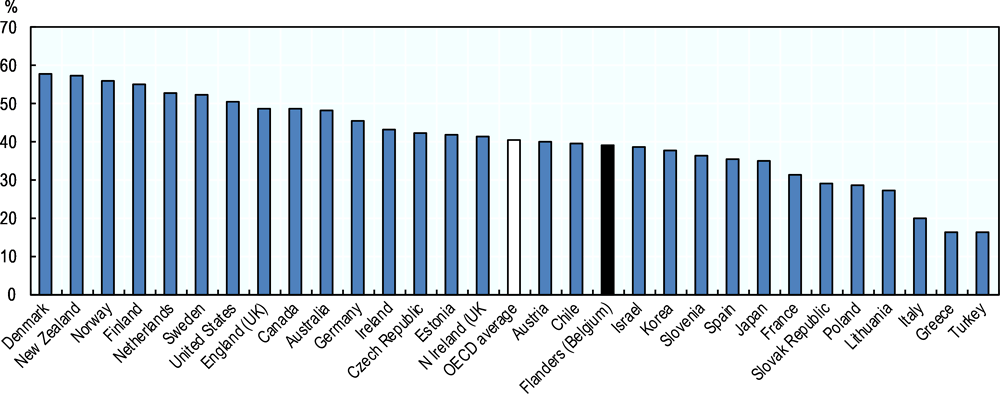

When considering job-relevant adult education the participation rate for adults in Flanders is around 39%, which is close to the OECD (PIAAC) average (41%) and falls behind leading countries such as the Netherlands (53%), Finland (55%), Norway (56%), New Zealand (57%) and Denmark (58%). There are also significant differences across socio-demographic groups.

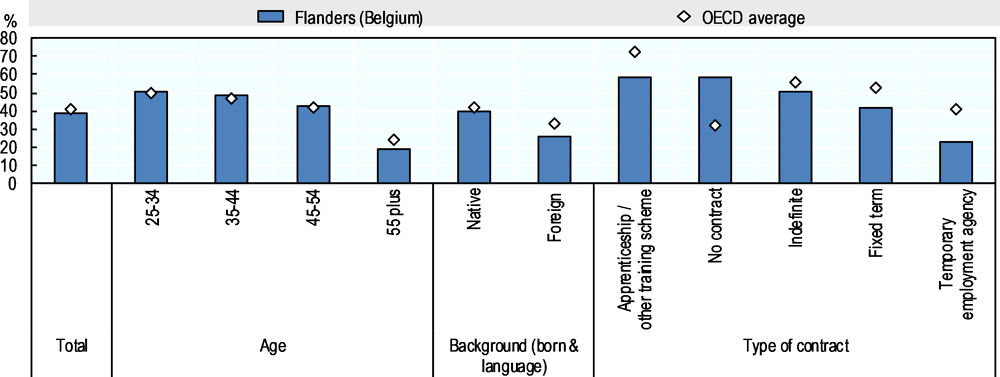

Older workers are much less likely than younger workers to participate in adult education. While for other age groups in Flanders the participation rate in job-related adult education is similar to the OECD average, those 55+ are much less likely to participate in this form of adult education than their peers in other OECD countries. From the employer’s perspective, it can make sense to invest more in younger workers, since there is more time to recuperate investment than for older workers. However, with an ageing population and a significant share of older workers who may want to remain professionally active past official retirement age, a low participation rate in adult education today could limit their employability in the future. For example, some may want to remain professionally active in their field, but would need to update their skills to do so. Others may want to work in other areas, but would require new skills to do so. There could also be health and social benefits for remaining active (VLOR, 2014[18]). According to projections by the United Nations (UN), by 2030 about 30.3% of Flanders, 27.9% of Wallonia and 18.7% of the Brussels-Capital Region will be 60 or over, which is slightly higher than other high-income countries (27.2%); similar to some neighbouring countries, such as France (29.9%); and lower than other neighbouring countries, such as Germany (36.1%) and the Netherlands (32%) (United Nations, 2015[19]).

Immigrant adults in Flanders also participate less in adult education. While 39% of natives in Flanders participate in job-related formal or non-formal education (on par with the OECD average), only 25% of immigrants do, which is below the OECD average. This is of particular concern, as immigrants in Flanders are three times more likely to have very low literacy rates3 than natives (38% vs. 13%). Female immigrants are even a more vulnerable group (SERV, 2018[20]). The demand of immigrants appears very high. For example, when immigrants do participate in non-formal education, they spend 60% more hours than native adults. This is similar to immigrants in Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands (OECD, 2018[21]). This may be largely due to the Dutch as a second language courses (Nederlands als Tweede Taal, NT2) that immigrants are enrolled in after arrival, which is compulsory for newcomers and ministers of official religions (Pulinx, n.d.[22]).

Adults in flexible forms of employment are less likely to participate in adult education. Around 50% of workers with indefinite contracts participate in job-related adult education, compared to only 42% of workers with a fixed term contract and 23% of those on a temporary contract with an employment agency. However, for the latter two groups participation in job-related adult education would be a particularly important investment for their career prospects and increase their chances for better quality jobs. The reduced participation may in part be due to employers being less willing to provide their temporary employees with training opportunities if there is no guarantee that they will stay long enough to allow employers to reap benefits from their investment. However, temporary employees are also not able to benefit from the many job-related adult education opportunities offered by VDAB, since they are often limited to the unemployed and not accessible to the currently employed. Stakeholders in the OECD workshops highlighted that this rigid system was not enabling current workers, such as those on temporary contracts, to proactively develop their skills for career moves.

The gap in participation between high and low-skilled adults in Flanders is large. Across all countries, low-skilled adults are significantly less likely than highly skilled adults to participate in adult education. This is the case for both formal and non-formal education (Figure 2.5). There is a similar pattern with level of education: adults with higher education levels are more likely to participate in adult education than adults with lower education levels. This reflects concerns raised by many stakeholders during the diagnostic workshop in May 2018 (Flanders, 2018[23]) that if not carefully guided by policy, adult education could be reinforcing inequalities stemming from early differences in initial education and family background rather than having a compensatory effect. A frequently mentioned term by stakeholders was the “Matthew effect”4 (Merton, 1968[24]) to describe the phenomenon that the advantaged being able to accumulate further advantages, while the disadvantaged are left behind. This highlights the importance of increasing efforts to ensure that the low-skilled, who have the most to gain from adult education, are actually participating.

Factors affecting adult learning

Motivation level of individuals

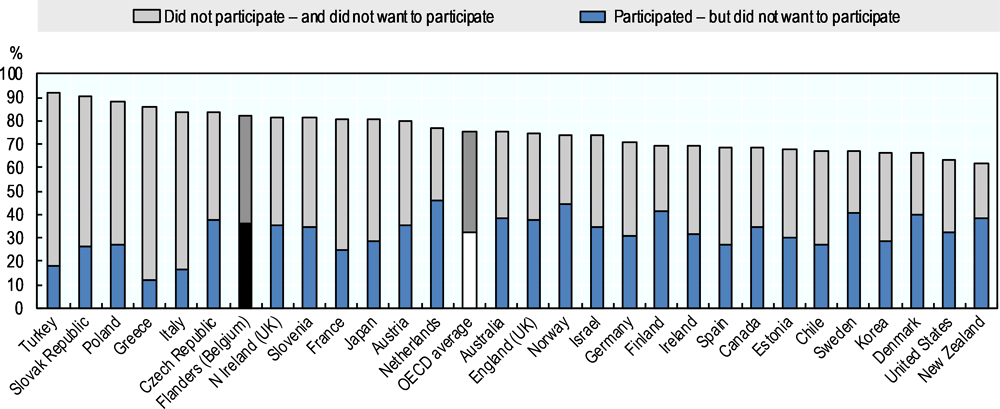

Motivation to learn is comparatively low among Flemish adults. A significant share of adults in Flanders reported not wanting to participate in adult education. Most of these individuals also did not participate in education, while others did despite their lack of motivation. While the lack of motivation is a common barrier across countries (Pont, 2004[25]), in Flanders the share of adults reporting that they are not interested in participating in adult education is significantly higher than the OECD average and leading countries such as New Zealand, the U.S. and Denmark. This is a reason for concern since motivation is considered to be key for successful adult education engagement (Carr and Claxton, 2002[26]), even more significant than socio-economic background (White, 2012[27]). Lower skilled adults are more likely to lack motivation than higher skilled adults (Lavrijsen and Nicaise, 2015[28]). The pattern is similar when looking at the readiness to learn index, which is made up of people’s responses to six questions in the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills that provide insight into people’s beliefs, values and attitudes towards learning – i.e. their learning culture. This proxy-measure of a learning culture at the individual level shows that adults in Flanders rank close to the bottom in comparison with adults in other OECD countries.

Fostering motivation for learning in the early years is critical to ensure disposition for lifelong learning as adults. The quality of teaching and the curriculum, as well as the engagement of students with different skill and motivation levels, are, among others, important factors. Once students drop out of initial education they are less likely to participate in adult education later on (VLOR, 2014[18]). The more young students can be engaged in a learning experience that fosters a positive attitude towards learning, the more likely they are to seek out and take up learning opportunities later as adults. The higher their skill levels and levels of education, the more equipped they will be to continue to learn in adulthood. This is particularly relevant for students who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those with low socio-economic family status, migration history and parents with low education levels. Providing these students with support early on can help them to develop a positive attitude towards learning and be equipped with the foundational skills that will enable them to continue to learn skills specific to their future needs. Later on improving work chances and career prospects as well as active participation as a citizen in society are also important factors to stimulate motivation for learning in adult life.

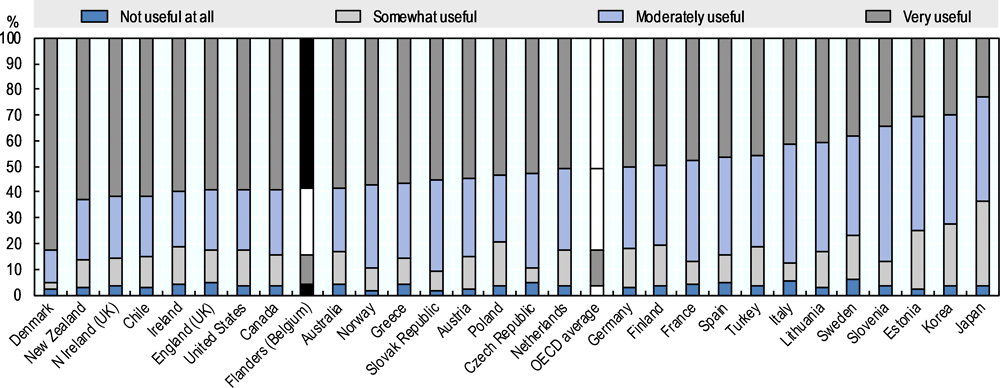

Relevance of adult education for jobs

Most adults participating in education find that it is relevant for their jobs, but there remains room for improvement. The share of people in Flanders who found formal or non-formal education useful for their job is above average, but not as high as in certain other OECD countries, such as Denmark and New Zealand. Many stakeholders participating in the OECD diagnostic workshop commented that the design and implementation of adult learning offers should place the learner at the centre and be undertaken in collaboration with key stakeholders, such as employers and unions (Flanders, 2018[23]). Low-skilled adults in particular tend not to see the relevance of formal and non-formal adult education. This may partly explain their lower participation rates (Vansteenkiste, 2014[29]), which reinforces the Matthew effect, with more skilled adults continuously upgrading their skills, while low-skilled adults are being left behind.

Accessibility of adult education

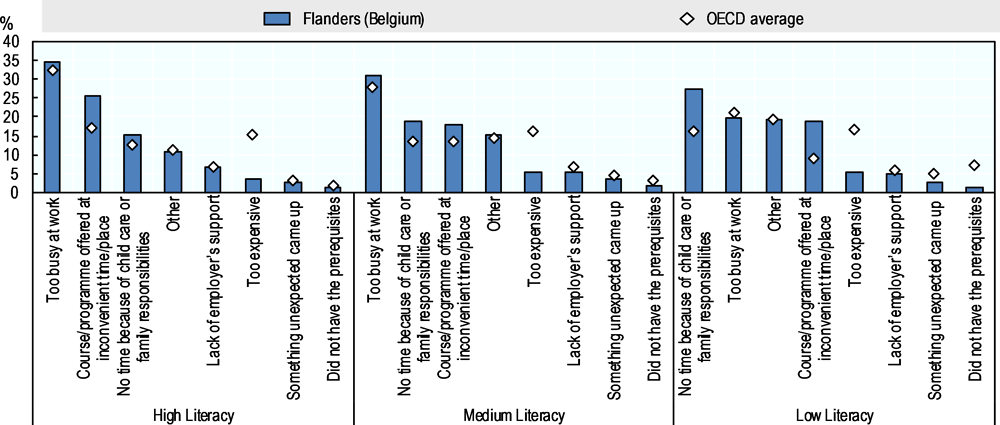

Time constraints due to work, competing family responsibilities and inconvenient time or place of adult education offers are the top limiting factors for Flemish adults. While these reasons are common in other OECD countries, in Flanders they appear to be more widespread. Other reasons mentioned were lack of employer support, cost, something coming up and not having the necessary requisites. While most of these obstacles are similarly common in Flanders as across other countries, there is a notable difference regarding the cost. In contrast to other OECD countries, the cost of adult education does not seem to be an obstacle to adults in Flanders. (This will be further discussed in Chapter 6 on financing).

While time constraints at work applies in particular to high and medium-skilled adults, competing family responsibilities is more relevant for low-skilled adults. This may be partly due to the types of jobs high and medium-skilled adults have, which may be more time intensive. Low-skilled adults may have fewer financial resources to afford childcare while participating in adult education. This suggests that policy interventions seeking to raise adult education participation may have to focus on different obstacles, depending on which group is being targeted.

Openness of higher education for adult learners

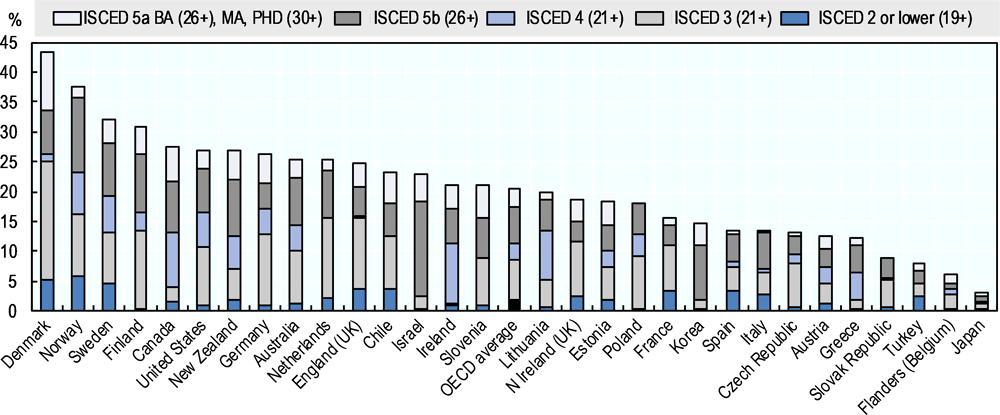

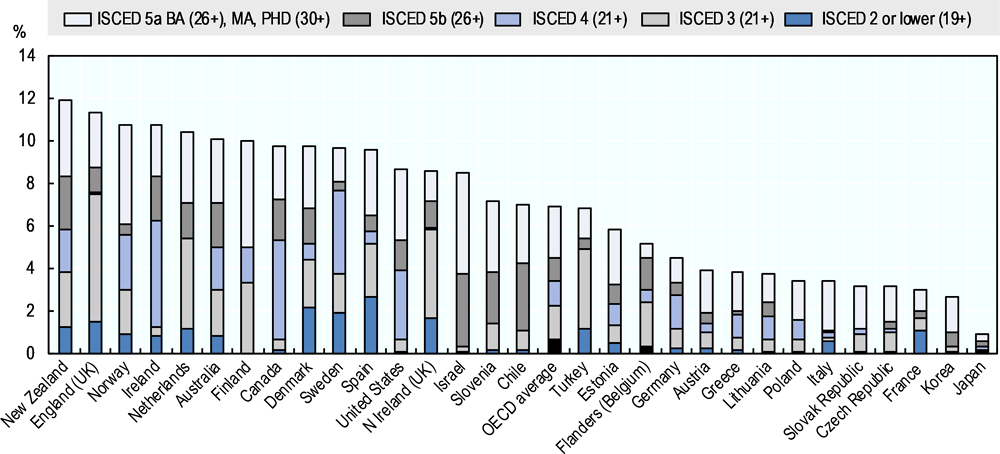

The higher education system in Flanders is underdeveloped for adult learners. In Flanders, the share of adults who have completed a higher education degree beyond the normative age5 is one of the lowest across OECD countries, with only Japan having a lower share. Only around 1% of Flemish adults were able to complete a typical university degree (bachelor’s, master’s, PhDs – ISCED 5a) at such a non-normative age. This is significantly lower than in other countries, such as Denmark (10%) and Finland (5%). This “stock measure” reflects that the higher education system has historically had a low degree of openness for Flemish adults. However, Flanders has already taken important steps to make higher education more open for adult learners. To analyse the more recent situation, the “flow measure” is used and it provides information about the incidence of participating in higher education in the previous 12 months. In this measure, Flanders falls below the OECD average, although it is not at the end of the ranking, and has only about 1% of adults participating in typical university courses (bachelor’s, master’s, PhDs – ISCED 5a). This is lower than in other countries such as Norway and New Zealand, where 5% and 4% of adults, respectively, have recently participated in higher education at a non-normative age. Higher education systems can play an important role in helping adults develop their skills further, which raises their labour market outcomes and productivity levels (Desjardins and Lee, 2016[30]).

Employer support for adult education

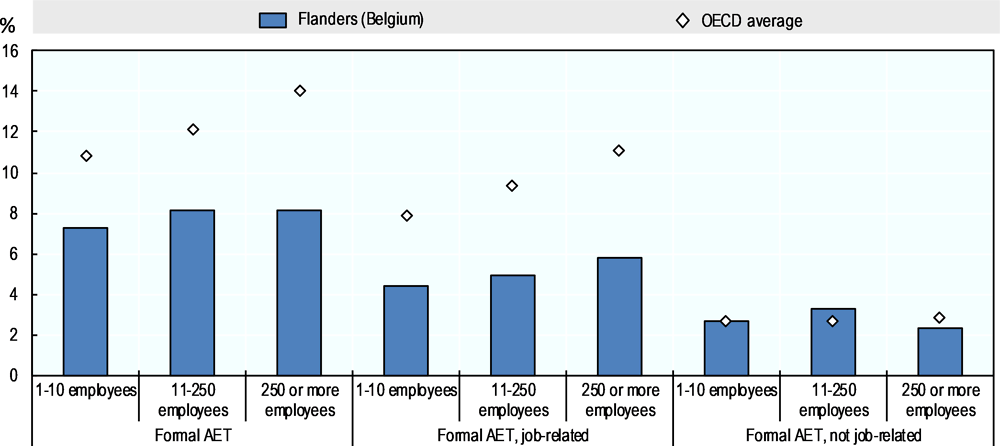

Large firms invest more in their employees’ skills development. This is the case for all forms of formal and non-formal job-related education. For purposes not related to the job, the participation rate is similar across firms regardless of size. A number of surveys (i.e. PIAAC, Adult Education Survey or Labour Force Survey) find that the smaller the firm the less likely the workers to receive job-related formal and non-formal education. This is the case across all countries. Larger firms typically have more disposable resources to invest in their staff. Small firms are also more concerned that after they invest in their workers they could be poached by larger firms, which can typically afford a more generous compensation package (OECD, 2015[31]). In Flanders, workers in larger firms are more likely to participate in job-related formal and non-formal education (Stichting Innovatie & Arbeid, 2015[32]). This is concerning, as there is a large number of micro and small and medium-sized enterprises in Flanders (UNIZO, 2014[33]).

Policies and practices to foster a learning culture

Fostering a learning culture and raising participation in and quality of adult education is possible through relevant policies and practices, which are presented in this section. This section is based on input from the stakeholder workshops, bilateral meetings, site visits and OECD analysis of international and national data sources and literature. Stakeholder perspectives on specific recommendations are indicated where they appear.

During the two OECD Skills Strategy workshops in May and September 2018, stakeholders in the groups assigned to the topic of learning culture discussed a wide range of issues and proposed recommendations. The OECD has carefully considered each of the perspectives and recommendations and incorporated them, as much as possible, in this section. However, due to the large number of ideas, and in order to go in-depth and provide concrete and elaborated recommendations, not all could be featured here. An overview of all the ideas that Flanders may wish to consider in the future can be found in annex A. Some ideas are integrated into other chapters rather than here (e.g. sectoral covenants, bottleneck occupations and career guidance in Chapter 3; information on adult learning in Chapter 5; and incentive measures for adult learning and financing of adult learning in Chapter 6).

Raise awareness about the importance of adult learning

As described in the previous section, the motivation level of Flemish adults for adult learning is comparatively low. Motivation is considered to be the key for successful adult education engagement. Willingness to participate in learning depends on factors that are both intrinsic (e.g. the desire to learn a subject) and extrinsic (e.g. improved chances for a better job), and governments can introduce policies that strengthen these factors in order to increase the motivation to participate. To raise the motivation level of adults to participate, especially the most vulnerable, it would help to make adults more aware of the benefits of adult learning, which include higher employability and earnings (Card, Kluve and Weber, 2015[34]) and non-economic returns such as mental health (Hammond, 2004[35]), well-being (Sabates, Hammond and Fellow, 2008[36]), civic engagement (Field, 2009[37]), and personal attributes such as confidence and self-efficacy (Hammond and Feinstein, 2006[38]). Employers play a key role in providing and stimulating education and training at work, and their support for adult learning depends strongly on immediate needs and expected returns. Increased employer awareness of the importance and benefits of adult learning – including the positive effects on productivity and long-term employability – could help to increase their support for adult learning.

Initiatives to raise awareness of adult learning have been developed, implemented and discussed in various countries and institutions. For example, campaigns in the form of multimedia advertisements and “adult learning weeks” are widespread in countries such as Denmark, Finland, Portugal and Slovenia. Effective initiatives to raise awareness should intend to change attitudes, knowledge and behaviours, and can take various forms. The EU, based on a number of best practice case studies, made a list of the steps to take to improve both participation in and awareness of adult learning (European Commission, 2012[39]). This list includes, for instance, the identification of target groups and relevant tools, and the development and promotion of an adult learning campaign.

Flemish adults can easily access information and guidance on adult learning opportunities, for instance by using career guidance vouchers and visiting websites with information on second chance education and flexible higher education options such as “www.onderwijskiezer.be”, but policies to actively enhance awareness of the importance of adult learning are limited. The challenge for Flanders is to develop policies to effectively raise awareness of the target groups most in need.

The government and stakeholders should raise awareness of the importance of adult learning in a rapidly changing environment (SERV, 2018[40]). Multiple stakeholders, such as libraries, youth organisations, education providers, local authorities and companies, can all play their role in encouraging lifelong learning and continuous skills development. Making learning more attractive and creating positive learning experiences for learners are key in this cultural transition and in fostering motivation.

The government, training institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), employers, sectoral training providers, and other relevant stakeholders should embed adult learning within a lifelong development approach. This means the whole path to development should be taken into account. Instead of incidental learning, a continuous development approach is needed. Learners should be aware of their career paths and training needs and companies should train workers towards specific career paths. Training institutions and public employment services should incorporate this lifelong development approach in their business models. (See Chapter 5 on governance, for more information).

International Adult Learners’ Week in Europe

International Adult Learners’ Week in Europe (IntALWinE) was a Europe-wide network that linked co-ordinators of national learning festivals in 15 European countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Italy, Hungary, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). It was supported by the EU programme Grundtvig. The three-year network project, which ran from 2003-2005, was co-ordinated by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL) and drew on and built up the strategic potential of learning festivals, with a view to developing a more consolidated European framework of co-operation. It also aimed to enhance the role of adult learners and use their input while developing learning processes.

United Kingdom – Premier League Reading Stars

The National Literacy Trust is an independent UK charity that works to transform lives through literacy by supporting those who struggle with literacy and the people who work with them. It conducts research on issues relating to literacy and works with teachers, literacy professionals and librarians. It provides literacy news and teaching resources to the 48 000 visitors to its website every month. The National Literacy Trust developed the Premier League Reading Stars programme, a reading motivation project that aimed to harness the power of football to encourage people to enjoy reading. It targeted hard to reach groups in society who may not have shown an interest in reading, but who do have a passion for football. Although primarily aimed at school age children, this project also engaged with and benefited parents. The project was implemented through a partnership with the UK Premier League and the participation of local libraries, which organised a series of football and reading activity based meetings for local children and their families.

Portugal – Minuto Qualifica

The introduction of the Qualifica Programme in Portugal which aims to reboot Portugal’s strategy to upgrade the education and skills of adults has been supported by several information tools. One includes a large-scale television campaign, Minuto Qualifica, launched in July 2017. The campaign includes 100 different video clips, each one to two minutes long, describing real-life situations and the impact of adult learning. The Qualifica Programme also has a web portal (Portal Qualifica) that provides access to a range of information on adult learning through multiple channels, including social media.

Sources: European Commission Directorate-General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) (2012[41]), Strategies for improving participation in and awareness of adult learning, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/024feeda-773e-4249-8808-158716e4296c; OECD (2018[42]), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/oecd-skills-studies_23078731https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/oecd-skills-studies_23078731

Tailor adult education provision to the specific needs of adult learners

A flexible adult education system is needed to respond to the diverse needs of a broad spectrum of adult learners with different backgrounds, as well as to the continuously evolving skill needs of the labour market. A flexible adult education system has an adaptive curriculum co-designed with various stakeholders. It matches adults to relevant adult education courses, which are provided in accessible formats (SERV, 2016[43]).

The curriculum of adult education courses should be designed, implemented and revised in co-operation with the instructors of adult education courses, employers, and adult learners themselves (Baert, 2014[44]). Through such a process the curriculum could become more “life-centred” in the sense that it will relate to real-life events and topics that directly affect the adults (e.g. job prospects, community and neighbourhood) (Vermeersch and Vandenbroucke, 2009[45]). Participants in the OECD Skills Strategy workshops emphasised the importance of focusing on the learner and including them in skills development decisions, so that the adult education content is directly relevant to their specific needs (Flanders, 2018[23]; Flanders, 2018[46]). The process of developing and obtaining approval for a revised or new curriculum needs to be shortened so that it can be relatively quickly adapted if needed. Currently, it takes at least two years for a curriculum to be designed and officially approved (VLOR, 2015[47]).

Matching adults to relevant adult education courses and granting them access can be achieved through systems of skills validation. These systems are particularly useful when linked to a qualification framework that makes formal, non-formal and informal learning visible and comparable (Baert, 2014[44]; Vermeersch and Vandenbroucke, 2009[45]). Such skills validation (Erkenning van Verworven Competenties, EVC) systems need to be tailor-made and available offline and online (SERV, 2015[48]). (See Chapter 3 on skills imbalances for a more in-depth discussion of this). Skills validation is particularly relevant for migrants who often lack the national credentials of the host country to certify their skills. Formally recognising existing skill sets acquired in their home countries could allow them to not repeat courses in their areas of expertise, but to focus instead on learning opportunities that increase their chances of successful integration (e.g. how to access healthcare, applying for a job) (VLOR, 2016[49]).

Providing adult education in a variety of learning environments could increase accessibility and thus raise participation. Some learning environments may be more accessible due to their familiarity with the target group and their location. This is particularly relevant for marginalised groups who may otherwise not know how to participate or feel intimidated by formal education institutions due to past bad experiences in the formal education system. Alternative venues include libraries, museums, sports clubs, religious buildings, cafes and day care centres. Box 2.3 for Flemish and international examples. It may be useful to offer adults with competing family responsibilities simultaneous childcare services while the parent(s) participate in adult education; this is particularly relevant for low-skilled adults who reported childcare as the main barrier. Accessibility to adult education may also be increased through flexible education formats, such as e-learning (e.g. massive open online courses), blended learning and distance learning. Adults who have difficulties being physically present in adult education courses due to their work schedule or family responsibilities could join virtually from home at a time of their convenience, i.e. after work or when children are asleep or taken care of. A certain amount of familiarity with and availability of technology would be required to fully benefit from these options.

The government, NGOs, employers, sectoral training providers, and other relevant stakeholders should partner to make adult education more accessible and relevant. They could, for example, co-create the curriculum, match adults to relevant adult education courses through skills validation, and expand the available learning environments of adult education courses. This would mean that those who are least likely to participate can be reached where they are and encouraged to participate. Such a partnership can distribute the cost of adult education provision and enable finding creative ways of tailoring the adult education experience to their needs.

Flanders – Dutch for mothers (formal)

Low-literate women with young children often do not participate in integration courses, as they are not designed for their needs, and because of young children that form a practical barrier. In May 2015, the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) launched a project call to start a specific Dutch course for mothers with young children from third countries (non-EU countries). By organising the courses at primary schools, the practical barrier disappears and mothers have the chance to participate in a civic integration programme. The main purpose is to teach these mothers Dutch and to involve them in the education of their children. The courses address the following four aspects: 1) Dutch language lessons: 2) support in healthcare and education; 3) raising development opportunities for children; and 4) integration and strengthening of mothers. The programme depends on local initiatives. Because of the lack of any structural co-operation, the programme requires good co-operation between primary schools, the local centre for basic adult education (centrum voor basiseducatie) and other agencies, such as Kind&Gezin which is the Flemish Agency for children and families. There are no exact evaluation results from the pilot projects that have been organised so far, but after the end of the programme, the mothers were asked to describe their experience. Most of the mothers reported feeling less isolated because of the contact and shared experience with other mothers. They also reported feeling more confident to go to the library, the local market or to make use of public transportation. In many cases, the Dutch for mothers’ courses also acted as a first step to other formal adult learning programmes.

England (UK) – Skills for Life

In 2001, England launched a national strategy to improve literacy and numeracy among adults and English for speakers of other languages. The Skills for Life strategy was supported by a national curriculum, framework of standards and assessments, and large national campaigns on television during prime time. The target group are the unemployed, low-skilled workers, young adults and other groups at risk of exclusion. Adult learning centres and colleges provide most of the courses, but trade unions, social and cultural services, employers and sport clubs are also being encouraged to provide general numeracy and literacy training.

Sweden – Swedish Higher Vocational Education

The Swedish Higher Vocational Education (HVE) programme is post-secondary vocational education that combines theoretical and applied studies in close co-operation with employers. The programmes are oriented towards the needs of the labour market and allow adult learners to put learning into practice through work-based learning. The Swedish government established HVE in 2001 to fill a gap in the Swedish education system by providing non-university higher education programmes in specific fields where there is an explicit demand from the labour market. The Swedish National Agency for HVE is the regulatory authority of the HVE programme. Its main task is to analyse the demand for qualified workforce in the labour market, decide which HVE programmes will be offered that year, and allocate public funding to the corresponding education providers. Employers and industries are involved closely in the design of the courses and participate actively by giving lectures and participating in projects. Evaluation results are released each year, which are overall strong: seven out of ten students have a job before graduating and nine of ten students are employed or self-employed one year after graduation.

Sources: Vervaet and Geens (2016[50]) (2016). Inburgering op maat van laaggeletterde vrouwen met jonge kinderen: draaiboek,www.esf-vlaanderen.be/nl/projectenkaart/gent-vzw-proeftuin-inburgering-op-maat-van-laaggeletterde-vrouwen-met-jonge-kinderen; Centrum voor Basiseducatie Kempen ((n.d.)[51]), Project Moeder-Taal draaiboek,www.isom.be/documents/Draaiboek-Moeder-Taal-Geel.pdf. Department for Education and Skills (2004[52]), Skills for Life – the national strategy for improving adult literacy and numeracy skills: Delivering the vision 2001-2004, http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/7187/7/ACF35CE_Redacted.pdf Cedefop (2015[53]), Sweden – attractiveness of higher vocational education programmes, www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/sweden-attractiveness-higher-vocational-education-programmes OECD (2013[54]), A Skills beyond School Commentary on Sweden, www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/ASkillsBeyondSchoolCommentaryOnSweden.pdf

Transform adult education providers into learning organisations

There are seven strategies, processes and structures that define a learning organisation in the field of education: 1) developing and sharing a vision centred on the learning of all students; 2) creating and supporting continuous learning opportunities for all staff; 3) promoting team learning and collaboration among staff; 4) establishing a culture of inquiry, innovation and exploration; 5) establishing embedded systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning; 6) learning with and from the external environment and larger learning system; and 7) modelling and growing learning leadership (Yang, Watkins and Marsick, 2004[55]; Kools and Stoll, 2016[56]). While some of these issues will be covered in Chapter 5 on governance, the focus in this chapter will be on supporting continuous learning opportunities for all staff and promoting team learning.

Continuous learning opportunities for all adult education staff are critical for the quality of adult education provision. This applies in particular to those working in the non-formal adult education sector, which tends to be less regulated and less well developed in terms of recruitment, initial training, certification and professional development of staff than the formal education sector. Since most adult education occurs in non-formal settings, the majority of adult education teachers, with the exception of teachers of the Centres for Adult Education and the Centres for Adult Basic Education, are not subject to such rigour. This means that, in practice, staff quality can vary greatly, with significant implications for the quality of the adult educational experience. For example, there is a lack of initial and in-service training for adult education teachers, coaches and instructors in Flanders, which means that many may not be sufficiently prepared and supported to teach adult students (Baert, 2014[44]). Induction programmes are important to help new teaching staff settle into the adult education centre, participate in peer work with other teaching staff, and receive mentoring by more experienced and effective teaching staff. The induction programmes have been found to increase teaching staff’s commitment, retention and student achievement (Cohen and Fuller, 2006[57]; Fletcher, Strong and Villar, 2008[58]). Feedback and formal appraisals can also have a positive impact on teaching staff’s level of job satisfaction and feelings of self-efficacy, as well as student learning and outcomes (Fuchs and Fuchs, 1986[59]; Hattie, 2009[60]). Professional development opportunities allow teaching staff to update and learn new skills for teaching, which is particularly important given the changing skill needs. This also applies to other professionals involved in the provision of adult education, including administrators of adult education, adult education curriculum designers, those in charge of training in companies (vorming training opleidings-verantwoordelijke, VTO), guidance counsellors of adult learners and social workers supporting marginalised adult learners.

In Flanders, Centres for Adult Education and Centres for Adult Basic Education, which provide formal adult education, are subject to regulations and quality control by the inspectorate. All of their teaching staff are required to have specific qualifications and to participate regularly in professional development. These same regulations do not apply to other adult learning providers.

Promoting team learning and collaboration among adult education professionals is important for more effective delivery of adult education. During the journey through the adult education system, the adult learner interacts with many adult education professionals. They all play an important role in ensuring that the adult education experience is relevant and of good quality. Better adult education provision can occur when these professionals collaborate through exchanging information about the specific needs of the adult learner, discussing how to adapt the adult education curriculum to the adult learner, and providing each other with constructive feedback and insights on how to improve. Technology can support such a collaborative environment by creating platforms for professional collaboration to occur (Falk and Drayton, 2009[61]). Other ways of collaborating include regular meetings to discuss challenges and potential solutions (Senge, 2012[62]), learning how to work together (Lunenburg, 2011[63]; Watkins and Marsick, 1999[64]), and external facilitation (Senge, 2012[62]).

The Support Centre for Non-formal Adult Education (SoCius) offers training and organises meetings for staff members of socio-cultural organisations involved in adult learning. It provides them with opportunities to interact with one another, engage in peer learning and potentially collaborate (Broek and Buiskool Zoetermeer, 2013[65]).

During the Skills Strategy workshops participants emphasised the importance of teachers working together to improve teaching quality. Some Centres for Adult Education (Centra voor Volwassenenonderwijs, CAE) are already promoting peer learning among their teachers, and collaboration among teachers from different disciplines could also be fostered. Workshop participants recommended that teachers be provided with internship opportunities in industry so that they can keep up to date with continuous changes and better ensure the labour market relevance of education.

Currently, higher vocational education (HBO5) that leads to an associate degree is provided by the Centres for Adult Education (Centra voor volwassenonderwijs), but from September 2019 will move to university colleges (hogescholen) (VLOR, 2017[66]) Some Skills Strategy workshop participants expressed their concerns that this move may mean that the offered courses will become more theoretical and less applied. This could happen if, for example, the instructors of these courses are no longer lecturers from industry but rather academic university staff (SERV, 2017[67]). Maintaining industry experts as guest lecturers after the move could help ensure that the curriculum remains closely aligned with labour market needs (Flanders, 2018[23]; Flanders, 2018[46]). Guest lecturers from industry should also receive some training to help them teach effectively and apply adequate pedagogical strategies for adult learners.

Norway

Skills Norway, in co-operation with teacher training institutions, universities and university colleges, developed a formal training model for teachers who teach basic skills to adults. It is a 30-credit programme spread over two semesters that focuses on teaching digital skills as part of basic skills. The goal is to enable adults to master the challenges of working and community life in an increasingly digitised world, as well as the qualification and certification of those who teach adults basic digital skills. Skills Norway also organises one-day seminars for professional development of adult teachers.

Germany

Community Adult Education Centres in the Stuttgart area established the Course Teachers Academy (CTA) in 1988. The CTA aims to provide a broad range of training and retraining courses for part-time and freelance staff in adult education. Besides providing access to a basic adult teaching qualification, the CTA allows teaching staff to keep their qualification continuously up to date and to receive training in a particular subject to meet any new qualification requirements. After participating in a course, teachers gain a certificate from the Academy. The Academy’s target group are the 50 000-60 000 course teachers in the Stuttgart area.

Sources: Kompetanse Norge (2018[68]), Basic skills – Kompetanse Norge, www.kompetansenorge.no/English/Basic-skills/#ob=9145; Plato and Research voor Beleid (2008[69]), Adult Learning Professions in Europe. A study of the current situation, trends and issues, www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/MumAE/adultprofreport_en.pdf.

Teacher training institutions, universities and university colleges (hogescholen), as well as other adult education providers (Centres for Adult Education and others), should do more to transform themselves into learning organisations. This would mean ensuring that all staff involved in adult education are given opportunities to receive further professional development and supported to collaborate.

Make higher education more accessible for adult learners

Higher education institutions have an underutilised potential to support adults in pursuing specific courses for current or future job needs. This may entail getting a degree or just one or few courses. Workers undertaking such courses may, as a result, be able to increase their chances for better earnings and career progressions (Blossfeld et al., 2014[70]). For immigrants whose initial degree from their home country was not officially recognised or doesn’t hold the same value in the host country, getting another degree in the host country may provide them with better job prospects and facilitate social integration. Expanding higher education for adult learners is also important for higher education institutions, since demographic changes have led to the number of traditional students declining. Countering this trend with an increased intake of adult learners could help higher education institutions remain financially sustainable.

Flanders, along with Italy and Japan, has one of lowest shares of adult learners in its higher education system (Desjardins and Lee, 2016[30]). Although all higher education courses can be accessed by students regardless of their age, in practice most students are traditional students who went on to higher education after finishing secondary education at age 18. There are, nonetheless, some mature students. Universities and university colleges (hogescholen) account for around 13% and 8% of formal adult education, respectively (Lavrijsen and Nicaise, 2015[11]). Flemish universities and university colleges have some specific programmes that target adult learners: postgraduate certificates, short courses in continuing education, bachelor’s and master’s programmes for adults learners, and advanced bachelor’s and master’s programmes to expand knowledge in the area of the first degree (Box 2.5). Distance programmes for adult learners are available through the Dutch Open University, which is supported by Open Higher Education study centres from the Flemish universities.

In the academic year 2017-2018, in university colleges only about 24% of the students in an advanced bachelor’s programme and 23% of the students in an advanced master’s programme are over 30 years of age. This indicates that participation of mature adults over 30 years who have a lot of work experience is relatively small in these programmes. Instead, these programmes are mostly taken up by traditional students, after they completed their bachelor’s or master’s degree, as well as young professionals who have limited work experience (Vlaamse Overheid, 2018[71]).

Most adult learners in these courses tend to already have a higher education degree, which reinforces the Matthew effect. Adults participating in higher education programmes who do not have a higher education degree are a small minority, which indicates that higher education in Flanders does not yet constitute a clear first/second chance option for adult learners. Pursuing higher education studies while working is also not common in Flanders. In the academic year 2017-2018, only 5,262 students in university colleges and 1,718 students in university combined working with studying (Vlaamse Overheid, 2018[72]). The courses, which are more accessible for adult learners in terms of when they are organised (e.g. evening classes) and modality (e.g. online), tend to be focused on specific fields of study, such as teacher training and nursing, and overall in social sciences and humanities (De Lathouwer et al., 2006[73]). There are only very limited offerings in other fields, such as science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) or subjects related to other bottleneck occupations (see Chapter 3 for more on these). This may partly be due to cost, since the limited number of students per class, as well as additional instruction times in evenings and weekends, can make this expensive (Boeren, 2011[74]).

Other countries, such as Denmark, Finland, Norway, the United Kingdom, and Singapore have much higher proportions of adult students who are 30 years and older participating in higher education. Denmark has a parallel system in higher education with a range of programmes specifically targeting adults, including masters, diploma and VVU (videregående voksenuddannelse) degrees (higher education degrees for adults). The Danish system in particular has increased access with skills validation processes that allow participants with relevant work experience to be admitted to diploma programmes without any other formal degree requirements.

Participants in the Skills Strategy workshops stressed the importance of making the higher education sector in Flanders more accessible for adults. They suggested that it was important to increase flexibility in the format and times of course offerings. Higher education courses could be offered in a more modular format, which presents the learning material of courses in self-contained units so that adult students can take them one at a time and more spread out. This would provide adult learners, who may not be able to complete a whole course in one attempt, the flexibility to finish the course over a longer period through taking one module at a time. This could be combined with the offer of more convenient learning times for adults, such as evenings and weekends.

In Flanders, the Second Chance Education programme (Tweede Kansonderwijs, TKO), part of CAE, offers early school leavers opportunities to get a secondary education degree through modular courses and during the evening (Box 2.5). Something similar could also be done at the higher education level.

When family care issues make participation in adult education difficult, complementary social policies are needed to address these issues, for example, childcare offered on or near higher education premises while the parent participates in adult education (Vermeersch and Vandenbroucke, 2009[45]).

Higher education institutions should consider enlarging the accessible course offerings for adult learners, including courses in areas such as science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) or specific bottleneck occupations (see Chapter 3 for more on these). Requirements of who can access these courses should also become more flexible and take previous work experience into account by assessment of prior learning. Courses should be tailored to adult learners needs and should be set up in broad collaboration with other higher education institutions and with businesses/sectors to create advantages in both the content (multi-disciplinary knowledge) and the organisation (fewer staff and infrastructural costs/overhead).

Flanders – Adult education in higher education

Universities and university colleges (hogescholen) in Flanders offer different possibilities for adults who are unable to be regular full-time students. Students can follow all bachelor’s and master’s programmes provided by the universities on a part-time basis, but regular courses are spread over the week. Universities and university colleges also provide special tracks of the regular bachelor’s and master’s programmes for students who combine work and study (werktrajecten). These programmes combine distance learning and a flexible organisation of the programme. Courses can take place, for example, in the evenings and weekends or are grouped on one or two days in the week. The requirements and qualifications are the same as those of the regular bachelor’s and master’s programmes. These flexible tracks are mainly provided by the university colleges (professional bachelor’s), especially for bachelor’s in education (primary education and secondary education), nursing and information and communication technology (ICT). In general, Flemish universities do not provide many bachelor’s and master’s programmes that can be followed in the evening and/or weekends. Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) was the first university to provide flexible master’s programmes for adults and now has a broad offer for students who combine work and study.

To broaden and expand the knowledge and competences acquired in an initial bachelor’s or master’s programme, students can follow an advanced bachelor’s or master’s degree programme. Students can start this type of programme immediately after the initial bachelor/master programme or after some work experience. University colleges and universities can also award postgraduate certificates after the successful completion of learning pathways with a study load of at least 20 credits. The purpose of these courses, in the context of continuing professional education, is to add further breadth or depth to the competences acquired on completion of a bachelor’s or master’s programme.

Adults can also follow certain parts of higher education through a credit contract, which allows adult learners to choose relevant courses without entering a whole bachelor’s/master’s programme. After participating successfully in the course, the student receives a proof of credit.

Flanders – Second chance education

Second chance education (Tweedekansonderwijs, TKO) is part of the formal adult education system and is provided by the Centres for Adult Education. It offers early school leavers the opportunity to obtain a degree of secondary education and opens the door for further education. Options include general education or a combination of professional education and additional general education. The modular structure and the possibility to follow evening courses gives adult learners the flexibility to set out their personal learning path. Each year, 10 000 adults are enrolled in second chance education and around 1 500 adult learners obtain a degree. As a financial incentive, graduates are paid back their tuition fees when obtaining a diploma. Recently, the Department for Adult Education joined the Visible Skills of Adults (VISKA) programme (part of the Erasmus+ programme) that aims to focus on the visibility of skills of vulnerable groups by the skills validation (EVC) from both formal and non-formal education.

The Danish parallel competence system

Denmark has one of the highest participation rates in adult education and training. In 2016, adult participation in both formal and non-formal education was over 50% for adults aged between 25 and 65. These high participation rates can be attributed to both the long tradition of adult learning in Denmark and the flexible system. In 1996, Denmark introduced an education system for adults that is parallel to the regular system: the adult and continuing education (ACE) system. This gives adults the chance to obtain secondary and/or higher education degrees. Secondary education includes basic and general adult education (Grundlæggende Voksenuddannelser, GVU, and Almen Voksenuddannelse, AVU) as well a higher preparatory degree (Højere forberedelses eksamen, HF) and labour market training (Arbejdsmarkedsuddannelser, AMU). Higher education gives adults the possibility to obtain a master’s degree or to follow modules at universities. There are also short-cycle higher education programmes (e.g. Videregående voksenuddannelser, VVU and Diplom uddannelser, diploma programmes) that make higher education more accessible for adults. The diploma programmes (corresponding to a bachelor’s degree), for example, are built in modules that may be taken together or separately according to the interests of adult learners. The education emphasises the competences the participant has from any previous work experience and the qualifications needed in the profession. Through skills validation, participants can also be admitted to diploma programmes without any formal degree requirements.

Since its introduction, the ACE system has undergone numerous reforms to make it even more flexible, demand-led and adaptable to the needs of the labour market. In 2003, it shifted to a competence-based system with over 130 competence descriptions defined by the Danish Ministry of Children and Education and social partners. Recently, a tripartite agreement involving the government, unions and employer’s organisations reformed the AMU programme in order to provide adults with or without existing vocational training with vocational adult and continuing education opportunities. The agreement emphasises a more flexible and digital training system, easier access to AMU programmes and financial incentives for both learners and employers.

Sources: Onderwijskiezer (2018[75]), Flexible studying in higher education, emph="italic">www.onderwijskiezer.be/v2/hoger/hoger_flexibel.php; Flanders (2018[76]), OECD Skills Strategy for Flanders Questionnaire; Cedefop (2012[77]), Vocational education and training in Denmark: short description, www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/4112_en.pdf; Danish Adult Education Association (2011[78]), Adult Education in Denmark, https://www.daea.dk/media/335952/vux_utb_dk_eng_2011.pdf Ministry of Education Denmark (2008[79]), The Development and State of the Art of Adult Learning and Education (ALE), http://asemlllhub.org/fileadmin/www.asem.au.dk/national_strategies/Denmark.pdf; Eurofound (2017[80]), Denmark: Social partners welcome new tripartite agreement on adult and continuing education, www.eurofound.europa.eu/printpdf/publications/article/2018/denmark-social-partners-welcome-new-tripartite-agreement-on-adult-and-continuing-education; OECD (2012[81]), A Skills beyond School Review of Denmark, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264173668-en; Eurostat (2018[15]), Participation in education and training (last 12 months), http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=trng_aes_100&lang=en.

Promote work-based learning in post-secondary education

Work-based learning is learning that takes place through a combination of observing, undertaking and reflecting on work in workplaces. There are different types of work-based learning schemes. Structured work-based learning schemes (e.g. apprenticeships, dual learning) combine on-the-job and off-the-job components of equal importance and typically lead to a formal qualification. A regulatory framework determines the duration, learning outcomes, funding and compensation arrangements. There is usually a contract between the learner and the firm. Work placements (e.g. internships, work shadowing opportunities) usually complement formal education programmes, are shorter, and are less regulated (Kis, 2016[82]).

Work-based learning has a positive effect on individuals as well as companies. Workplaces are important learning environments for individuals to develop technical and general skills (OECD, 2010[83]). Work-based learning allows companies to train employees and future employees. Providing a work-based learning placement (leerwerkplek) for students also positively affects the learning culture of the company, since work-based learning decreases the separation between working and learning (Heene et al., 2018[84]) and introduces an environment for learning (e.g. mentoring system).

Use of work-based learning in vocational programmes is increasing, but mostly at the secondary education level. Work-based learning in VET offers on-the-job experiences that make it easier to acquire both hard skills by using modern equipment and soft skills by working with people (OECD, 2010[83]). There is still a strong emphasis on school-based over work-based learning in vocational programmes in Belgium. In Flanders, work-based learning is offered in part-time vocational secondary education (deeltijds beroeps secundair onderwijs, DBSO) and in Syntra (leertijd). In the school year 2017-2018, 6 668 agreements for work-based learning were registered on the online registration platform “www.werkplekduaal.be” (Vlaams Partnerschap Duaal Leren, 2018[85]). Flanders introduced dual learning (duaal leren) in a pilot project in the 7th year of vocational upper secondary education (beroeps secundair onderwijs, BSO), in the upper secondary vocational and technical education (beroeps en technisch secundair Onderwijs, BSO and TSO) and part-time vocational secondary education (deeltijds beroeps secundair onderwijs, DBSO) and in specialised secondary education (buitengewoon secundair Onderwijs BuSO). In the school year 2017-2018, 503 students participated in the pilot project “School desk in the work place” (Schoolbank op de werkplek) (Box 2.6) (Vlaams Partnerschap Duaal Leren, 2018[85]). However, 105 students dropped out during the year. The most popular fields of study are hair care, electrical installations, healthcare, childcare and car maintenance (De Tijd, 2018[86]). In the school year 2018-2019, more than 1 000 students started a dual learning programme. Dual learning will be introduced as an equivalent path to full-time education as of September 2019.

Work-based learning is used to train the unemployed. The Individual Vocational Training (Individuele Beroepsopleiding, IBO) programme is the largest work-based learning programme in Flanders (others include work-based learning at VDAB, training internships, training projects with companies, work experience internships, profession immersion internships, activation internships and short training with internships on the work floor). IBO allows employers to hire a jobseeker and, with the financial support of VDAB, train them in the workplace, typically over a period of 4-26 weeks. The wage and social security contributions of the individual are covered by VDAB, and the employer is only expected to pay a “productivity premium”. In return, the employer is expected to hire the individual after the training, normally on a permanent contract. This programme has been highly successful, with 90% of participants still working in the same company where they trained one year later.

Some types of work-based learning are common in university colleges (hogescholen). While mandatory periods of work placement are required in most professional bachelor’s degree programmes offered by university colleges, there is no formal regulation for more structured forms of work-based learning (i.e. dual learning). However, structured work-based learning has been found to provide an important stepping-stone for participants to move from education to employment (Kis, 2010[87]). From September 2019, a new reform will move associate degrees (HBO5-opleidingen), which are short-cycle higher education programmes formerly provided by the Centres for Adult Education (Centra voor volwassenonderwijs) that offer dual learning components, to university colleges. This could be an opportunity for university colleges to expand dual learning to the professional bachelor’s degree programme.

Work-based learning in universities could be expanded. In universities, most bachelor’s and master’s programmes do not require work-based learning at all, and some programmes (e.g. business studies) require only a short-term work placement. The exceptions are in specific study fields, with work placements ranging from several months (e.g. psychology, education) to years (e.g. medical studies) (Verhaest and Baert, 2018[88]). More work-based learning opportunities, whether work placements or dual learning, could be beneficial for university students in helping them transition from education to work.

Work-based learning in adult education is sparse. In some adult education programmes, such as associate degrees from CABEs, there is a work-based learning component. However, these associate degrees are now being transferred to university colleges. Other adult education programmes could be improved by incorporating work-based learning elements to benefit adult learners who would like better employment chances. This is particularly relevant for the employed in Flanders. While the unemployed can benefit from many work-based learning programmes, the employed do not have such opportunities. Providing them with work-based learning opportunities could enable them to proactively prepare themselves for career progression and transitions without having to wait until becoming unemployed to take the necessary steps.

Education providers and employers, among other stakeholders, should examine the possibility of expanding work-based learning in university colleges, universities and adult education. These stakeholders should participate in the European Structural Fund call for tenders that seeks to support pilot projects on dual learning in higher education and adult education (ESF Vlaanderen, 2018[89]). Employers and education providers should also be supported by the government to widely apply a framework for high-quality workplaces, which establishes quality criteria covering curriculum, programme duration, physical resources, and qualification requirements.

Dual training: Chemical process techniques – BASF

The chemical production company BASF was one of the first companies to facilitate dual learning for students enrolled in chemical process techniques education through the project “School desk in the work place” (Schoolbank op de werkplek). After two years, BASF indicates that it is a win-win situation for the school, the company and the student. The schools can rely on the infrastructure and technology of the companies and the students can apply their knowledge under supervision within a realistic working environment in which they also acquire the right working attitudes regarding safety, interaction with colleagues and punctuality. The dual form of learning strengthens the content of the training and offers well-trained candidates to the company. From the first pilot project in 2016, all students (25) have found a job in the sector. Recently, the bonus for employers and students (start-en stagebonus) has been reformed to make it more transparent and to simplify the administrative process. There is broad support for extending dual training to other types of education programmes.

Hands-on Enterprise Architect Training (HEAT) programme

In this advanced master’s degree, students combine working in an ICT strategy consulting company and the IC (inno.com) institute that offers the Master’s of Science in Enterprise Architecture. The HEAT programme illustrates the great potential of dual learning as a learning method in higher education, especially in STEM related study areas.

Sources: Dekocker (2016[90]), Ready for dual? How to encourage employers to join in dual learning?; De Standaard (2018[91]), Dual learning is catching on in the chemicals sector, www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20180912_03738405; Jobat (2018[92]), Chemicals sector reaps the benefits of dual learning, www.jobat.be/nl/artikels/chemiesector-plukt-vruchten-van-duaal-leren/; SERV (2018[93]), Skills above: 11 inspiring practices in Flanders, www.serv.be/serv/publicatie/vaardigheden-boven-11-inspirerende-praktijken-vlaanderen; Syntra Vlaanderen (2018[94]), “Dual learning and lifelong learning in higher education: the HEAT case”, www.syntravlaanderen.be/duaal-leren-en-levenslang-leren-in-het-hoger-onderwijs-de-heat-case.

Promote human resource practices that stimulate a learning culture in the workplace

Promoting a learning culture in the workplace matters. While reducing the number of low-skilled adults through strong initial education is key, the workplace for many adults is the most important place for continuous learning in adulthood. Learning in the workplace ensures that employees continue to adapt to changing skill demands and remain employable (Ellinger, 2004[95]). It is important for companies to have a learning workforce so that they can quickly adapt to evolving needs, adopt new approaches and technologies and not fall behind their competition (Ellström, 2002[96]). In comparison to full-time formal adult education, learning in the workplace, both non-formal and informal, is less costly and is directly relevant for the job, as acquired skills can be immediately deployed without a time lag (Baert, De Witte and Sterck, 2000[97]; Boud and Garrick, 1999[98]).

Since the readiness to learn index indicates that the disposition to learn on one’s own is relatively low in Flanders, firms could take a more proactive role in stimulating their employees to undertake learning. They could provide the right environment through specific human resource and managerial practices that encourage employees to grow professionally and develop in their jobs (Billett, 2004[99]).

Certain human resource practices can incentivise employees to learn. A number of human resource practices can influence the decisions of workers to participate in learning (Clauwaert and Van Bree, 2008[100]). These include having access to training courses, internal meetings, collegial consultations, job rotation, feedback mechanisms and mandatory on-the-job learning courses (Eraut, 1994[101]; Education Development Center, 1998[102]). Researchers in Belgium identified that among these the most important condition for fostering learning in the workplace was creating opportunities for employees to receive feedback. Feedback could be received through a manager, mentor, coach, or buddy. It could take place informally in a debrief session or career consultations, as well as more formally during performance reviews and general appraisal (Kyndt, Dochy and Nijs, 2009[103]; Bednall, Sanders and Runhaar, 2013[104]). Since employees with lower education levels are less likely to participate in these practices, the firm should encourage this group of people in particular.

Participants in the Skills Strategy workshops made a number of recommendations for stimulating learning through human resource practices. One suggestion was to include participation in training in job descriptions of employees, feature learning as part of the vision and mission of the firm, and develop a strategic skills development plan for the firm. This would make it clear to the employee at the point of hiring that continuing to learn was an expectation and important value in the workplace. Another suggestion was to stimulate learning through increasing the mobility of employees within the firm. The assumption was that by allowing employees to move internally they would be able to acquire new skills (Flanders, 2018[23]; Flanders, 2018[46]).

Managers play a critical role in promoting a positive learning culture in the company (Baert, 2014[44]). Skills Strategy workshop participants mentioned that managers in companies define the company culture and determine how time is being spent. It was suggested that training should be provided to managers, with funding for such manager training coming from sector funds. The training should consist of learning how to communicate and provide feedback to their employees, conduct regular career consultation sessions, provide regular performance reviews, and publicly recognise and celebrate learning achievements. One concern raised was that it was also necessary to ensure that managers are actually able to take the time to implement these new ideas. A good example of management promoting such a learning culture in a company is Marine Harvest Pieters, based in Bruges. Managers in this firm reach out to their staff members and encourage them to participate in internal and external training (see Chapter 4 for more details). They also introduced a buddy system that allows new employees to receive support and immediate feedback.

Since Flanders has many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that may not have a strong human resource infrastructure to implement such policies, targeted support may be required. For example, government could provide or subsidise training for managers and employees in SMEs. Funding from sector covenants may also help cover the costs of such initiatives.