2. Scope of the review and analytical framework

This chapter provides a brief overview of the main aspects of the external procedures in place in Brazil to assure the quality of the federal higher education system – the subject of this review - before setting out the framework that the review team has used to structure and guide its assessment of the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of these procedures. To contextualise the analysis in the review and the analytical framework used, the chapter also provides a brief review of some of the main developments and challenges faced by higher education quality assurance systems internationally.

2.1. Focus of this chapter

This chapter provides a brief overview of the main aspects of the external procedures in place in Brazil to assure the quality of the federal higher education system, before setting out the framework that the review team has used to structure and guide its assessment of the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of these procedures.

As with other OECD education policy reviews, this review provides a qualitative assessment of the specific policies under scrutiny. It takes into account the objectives established by national authorities for the policies in question and bases its judgements on documentary evidence and stakeholder opinion regarding the implementation of the policies in Brazil; lessons from international standards and practice in other OECD and partner countries; and the experience and expert opinion of the review team members.

The review recognises that systems for the external quality assurance of higher education, like other types of public policy, need to be tailored to the specific situation in the jurisdictions where they are applied. As in other policy fields, there is no single set of “best practices” in the external quality assurance of higher education that can be applied uniformly to all higher education systems. This review therefore presents international standards and guidelines – to the extent that these exist – and practice examples from other countries as reference points and potential sources of inspiration for Brazil, rather ready-made models that could or should be applied in the Brazilian context.

The simple analytical framework used to guide the review – outlined more fully later in this chapter - is based on standard policy evaluation criteria. The most important criteria are the relevance of the objectives of different parts of the external quality assurance system to the challenges and requirements of the Brazilian context; the effectiveness of the different aspects of the system in achieving their objectives; and the efficiency (and cost-effectiveness) with which they do this. In judging the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of different aspects of the quality assurance system for higher education in Brazil, the review team has taken into account domestic criteria (for example, does the system fulfil the objectives established by Brazilian legislators? Is the system considered to be effective by Brazilian stakeholders?); and international criteria (for example, does the Brazilian system promote minimum quality standards, differentiated assessment of quality or quality enhancement as well as systems in other jurisdictions?).

Before setting out in more detail the analytical framework and the evaluative questions that structure the rest of the analysis, the following sections, first, provide an overview of main components of Brazil’s external quality assurance systems for higher education and, second, briefly examine the development of external quality assurance systems in higher education more generally, and common challenges faced internationally.

2.2. External quality assurance of higher education in Brazil

The federal government regulates most higher education in Brazil

Brazil has well-established systems in place at national level to regulate the operation of public and private higher education providers in the federal higher education system and assess and monitor the quality of their teaching and learning activities.

Within Brazil’s federal governance structure, responsibility for providing and regulating higher education is formally shared between the federal government, the 27 federative units (the 26 states and the federal district of Brasília) and the municipalities. The federation, many states and a small proportion of (large) municipalities all have public higher education institutions (HEIs) falling under their responsibility. All private higher education providers in the country legally fall under the regulatory responsibility of the federal government. The “federal higher education system” thus comprises federal public and all private HEIs. Of the roughly 2 400 HEIs in Brazil, 92% (federal public and private) fall under the regulatory responsibility of the federal government and these institutions, together, account for 91% of undergraduate enrolment. 75% total undergraduate enrolment in Brazil is in the private sector (see Section 3.4 for an overview of the Brazilian higher education landscape).

Quality is assured through related processes of regulation, evaluation and supervision

The federal authorities assure the quality of higher education institutions and undergraduate education1 in the federal system through a combination of distinct, but closely related, processes referred to as regulation, evaluation and supervision and currently coordinated by the Ministry of Education (MEC):

The regulation of higher education, undertaken by Secretariat for Regulation and Supervision of Higher Education (SERES), a division of MEC, involves issuing formal approval (in the form of regulatory acts) for the operation of higher education institutions and individual undergraduate programmes. All public and private HEIs in the federal system formally require accredited status to operate2 (and periodic re-accreditation) and official recognition of the undergraduate programmes they provide. Programme recognition must also be renewed periodically, based on the results of quality evaluations. As discussed in Chapter 4 depending on their level of institutional autonomy, institutions may also need prior authorisation from MEC to start new undergraduate programmes.

SERES makes its decisions regarding the accreditation and re-accreditation of HEIs and the authorisation, recognition and renewal of recognition of undergraduate programmes taking into account the results of institutional and programme evaluations, undertaken by the evaluation division of the Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (INEP). These evaluation activities encompass external assessment of institutions and programmes and assessment of student learning outcomes through the National Examination of Student Performance (ENADE). Collectively, these three types of evaluation (institutional, programme and student) form the National System of Higher Education Evaluation (SINAES), which was established in its current form in 2004 (Presidência da República, 2004[1]). The evaluation of institutions and programmes (discussed in more depth in the following chapters) is based on on-site inspections by external review panels, results obtained by graduates in ENADE and, at present, a limited number of other quantitative indicators intended to measure programme quality.

Alongside its regulatory duties (the issuing of regulatory acts), SERES is also tasked with the supervision of quality in the federal higher education system. In practice, this means ongoing monitoring of quality levels in the federal higher education system, using the results produced by the evaluation work coordinated by INEP, and taking preventive and corrective measures when quality problems are identified in individual programmes and institutions (Presidência da República, 2017, pp. 1, art.2[2]). SERES can require institutions to take steps to address quality problems identified in evaluations, impose sanctions or proactively require intensified monitoring and evaluation of particular programmes or institutions.

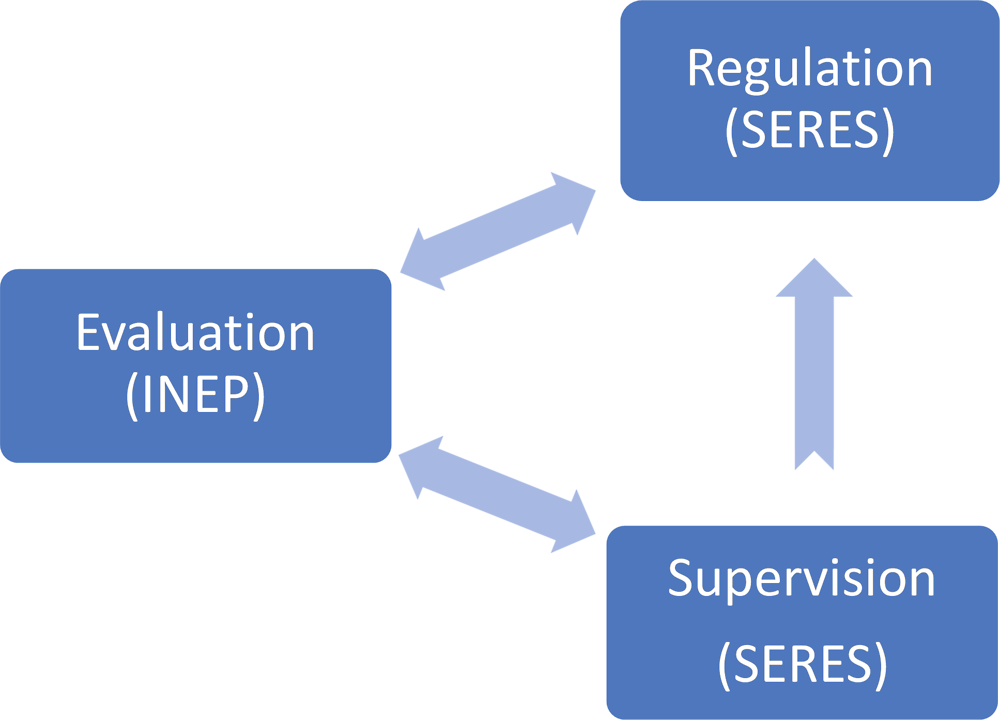

Figure 2.1 illustrates the inter-relationship between regulation, evaluation and supervision, whereby the evaluation activities, coordinated by INEP, that make up the SINAES feed into the regulatory and supervisory activities undertaken by SERES.

Separate procedures exist to assure the quality of academic postgraduate programmes

Postgraduate education in Brazil3 takes the form of either purely vocational “specialisation” programmes, referred to in the Brazilian system as lato sensu programmes (which include MBAs), or academic Master’s, Professional Master’s and Doctoral programmes, which are classed as stricto sensu postgraduate programmes. Accredited HEIs in the federal education system may provide lato sensu programmes without regulatory authorisation or recognition from MEC, provided they operate at least one formally recognised undergraduate programme or at least one approved stricto sensu postgraduate programme (Presidência da República, 2017, p. 29.2[2]). The provision of academic, stricto sensu, postgraduate programmes in conditioned on prior evaluation and approval by the Foundation for the Coordination and Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES), a decentralised agency of the Ministry of Education.

CAPES has been responsible for assuring the quality of academic postgraduate educational programmes since the mid-1970s. Since 1998, it has operated a quality assurance system that requires all proposed new academic postgraduate programmes to achieve a positive evaluation score in a peer review process and, from then on, to receive a positive evaluation in periodic reviews (currently every four years). CAPES is responsible for the quality assurance of all academic postgraduate programmes in Brazil, including in state and municipal institutions, which are not subject to SINAES. In practice, it fulfils the roles of evaluation, regulation and supervision for academic postgraduate programmes – functions which are split between INEP and SERES for undergraduate provision in the federal system.

However, CAPES only evaluates individual postgraduate programmes. It requires that all programmes within its remit be provided in formally accredited institutions and thus relies on SERES and state education authorities to undertake institutional accreditation (for institutions in the federal and state systems, respectively). Moreover, the results of CAPES evaluations are taken into account in a composite indicator of institutional quality used by INEP (see Chapter 7).

The normative framework for SINAES has recently been updated

The legal basis governing higher education in Brazil is provided in the federal Constitution and by the 1996 Education Act (Presidência da República, 1996[3]), which establishes basic principles concerning the role of higher education, the division of competences between the Union and the states and the role of the federal government in quality assurance. SINAES was established by a specific law passed by Congress in 2004 (Presidência da República, 2004[1]). This sets out the basic principles of the SINAES, including the requirement for institutional, programme and student assessments, the role of on-site inspections and ENADE, and the relationship between evaluation, regulation and supervision. The current regime for evaluation of stricto sensu postgraduate provision was established through ordinances (portarias) issued by MEC and CAPES from 1998 onwards and which have been updated periodically.

The detailed implementation rules for SINAES (evaluation) and the processes of regulation and supervision, reflecting the 2004 law, were initially established in a 2006 presidential decree (Presidência da República, 2006[4]) and supplemented by ordinances issued directly by MEC. This decree was replaced at the end of a 2017 by a new decree setting out the processes of evaluation, regulation and supervision in greater detail than had previously been the case (Presidência da República, 2017[2]). The changes brought about by this new decree are discussed in the relevant sections of this report. In broad terms, however, it seeks to simplify the administrative processes related to authorisation of undergraduate programmes and modifications to programmes, rationalise procedures for on-site inspections and provide more clarity about the preventive and corrective measures SERES may take in its supervisory role (MEC, 2017[5]).

These recent changes have been reflected to the extent possible in the review findings and taken into account in the formulation of recommendations. However, as the changes have only recently started to be reflected in the practices of SERES and INEP, it has not been possible to seek views from stakeholders about their practical impact or to judge their effectiveness in practice.

2.3. Quality assurance in higher education internationally: developments and challenges

External quality assurance in higher education has developed in recent decades

The development of quality assurance systems in higher education is a comparatively recent phenomenon. Historically, the quality of learning and teaching in higher education was generally – and largely implicitly - assumed to be guaranteed by the presence of academics with an established record of scholarship. A high degree of individual academic autonomy in universities meant that, in many countries, neither public officials nor university and faculty management frequently intervened in the teaching activities of staff members. Although governments may have granted or withdrawn permission for universities to operate, and may have provided funding, owned buildings and even regulated staff conditions and salaries in public institutions, in much of the world they rarely or never engaged with institutions’ day-to-day teaching and research activities. This pattern of strongly independent public or private not-for-profit institutions is the traditional model of higher education institutions in most of Latin America.

Over the last three decades, this situation has evolved, as governments across the world have introduced external quality assurance systems for higher education and higher education institutions have increasingly developed formalised internal quality procedures for learning and teaching. Key factors driving increased government intervention have included the expansion of higher education and the break-down of historical trust relationships among small elites; the expansion of demand-absorbing private sector provision – particularly in Latin America and Eastern and Southern Europe; and a broader trend for governments and society to demand greater evidence of performance and value for money from publicly supported institutions and services (OECD, 2008[6]; Brunner and Miranda, 2016[7]).

Quality assurance systems have different objectives

Literature on quality assurance in higher education often distinguishes between the related goals of accountability and quality enhancement (ESG, 2015[8]; CHEA, 2016[9]). Accountability refers to the aim of providing information to assure the public (including students and their families) of the quality of higher education institutions’ activities. This is a goal common to virtually all external quality assurance systems in higher education. Quality enhancement involves providing advice and recommendations on how higher education providers might improve what they are doing, and is a less well-established aspect of many external quality assurance systems.

Some external ‘quality assurance’ systems are essentially little more than licensing systems, where higher education providers are authorised to operate by public authorities if they meet minimal operating requirements. Such systems provide only a minimum level of accountability, which is essentially limited to providing the public with information on whether a provider is legally registered or not. Other systems make authorisation and accreditation of higher education activities (or the allocation of public funds) dependent on positive results from a more in-depth evaluation of indicators of quality. Depending on the relevance and quality of the criteria and data sources used by HEIs and external evaluation agencies, such systems might be expected to offer a greater guarantee of minimum quality standards and, as a result, a better degree of accountability. In addition to providing these kinds of accountability guarantees, the most advanced external quality systems also seek to promote enhancement of quality and continuous improvement. Such systems generally seek to move beyond external regulation and control to promote a quality culture in all areas of higher education activity, in partnership with HEIs and academic staff.

Defining and measuring quality is challenging

Arriving at a shared understanding of what quality in higher education is and how it should be measured has proved challenging for those involved in developing and running quality assurance systems (CHEA, 2016[9]). There are at least three main reasons for this:

-

1. As noted in the 2015 Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area ‘Higher education aims to fulfil multiple purposes’ and ‘stakeholders, who may prioritise different purposes, can view quality in higher education differently’. The importance attached to different aspects of the educational process or different kinds of learning outcome acquired by students (for example, theoretical knowledge as opposed to practical skills) can vary between individuals and groups within a single higher education system and internationally. The co-existence of higher education institutions with diverse missions and types of programme is explicitly acknowledged in the Brazilian legislation establishing the SINAES (Presidência da República, 2004, p. art.3[1]).

-

2. The expansion of higher education has led to more diverse modes of provision and student populations, and to demands for a more diverse set of programmes and institutional profiles. This means that quality in higher education now comes in more diverse forms and needs to be measured in more diverse ways.

-

3. Even when there is agreement on the components of quality in different types of higher education context, it may be conceptually and technically difficult to measure these components in a reliable way. If what is important may not always be measurable, what is measurable may not always be important. In the absence of reliable or feasible direct measures of different aspects of quality, quality assurance systems frequently resort to the use of proxy measures, which themselves can become the subject of disagreement.

Quality education is education that is fit for purpose

Notwithstanding these challenges, recent international efforts to develop a shared understanding of quality in higher education (CHEA, 2016, p. 48[9]) argue that quality education is best conceived of in terms of fitness for purpose. In other words, good quality higher education is education that:

-

1. Sets out to deliver the right kinds of learning outcomes for students – where the right kinds of learning outcomes are ones that meet the needs of students and society. The concept of learning outcomes encompasses both breadth and depth of knowledge and skills: good quality education programmes establish the right intended learning objectives, at the right level of complexity for their target student population;

-

2. Creates and uses a learning environment (qualified teachers, teaching methods, learning resources, opportunities to gain practical experience, etc.) suitable for achieving these learning outcomes and;

-

3. Succeeds in practice in delivering the intended learning outcomes for as many participating students as possible who begin studying.

The first element above is about intentions and, specifically, setting relevant learning objectives. The second element concerns inputs (including teaching staff and resources) and processes (including teaching methods and activities). The third element deals with the output4 of the educational process. In addition, those concerned with the quality of higher education may look at the broader outcomes of graduates who have gone through the educational process and in particular their entry into and progression within the labour market. Outcomes in this sense are influenced by the educational process, but also by a range of other external factors.

Quality systems focus on inputs and processes, less frequently on outputs and outcomes

External quality assurance systems in higher education initially focused to a large extent on measuring inputs, such as the level of qualification of teaching staff and the number of books in the library, as a way of gauging the quality of provision. Although input measures are usually readily available and objective, on their own they provide little evidence of quality in practice. The fact that a member of teaching staff has a Master’s degree of a PhD might be considered important and perhaps necessary, but it is not sufficient to assure their ability as a teacher. Funding is another input. Adequate funding might be assumed to be a precondition for creating an effective learning environment. However, defining what level of funding is ‘adequate’ is often challenging and controversial and, once defined, adequate funding is not, in itself, a guarantee of quality.

Processes – in particular learning, teaching and assessment methods – can provide an indication of the likely effectiveness of the teaching and learning experience for students, and are therefore monitored in many quality assurance systems in higher education. For example, procedures for external marking of written assessments and examinations may be taken into account as an indicator of the reliability of assessment processes (and thus the validity of the results and qualifications awarded by an educational programme). However, many aspects of teaching and learning are difficult to capture and assess in a binary (yes/no) or quantitative way, which makes it difficult to collect quantitative data on such processes.

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on the possibility of using output and outcome information in quality assurance systems. The most direct outputs of the educational process are graduates with increased knowledge and skills (learning outcomes) acquired through their education. Isolating the specific added value of a student’s higher education experience from other factors like the social and cultural background is intrinsically very challenging. However, internationally, standardised tests are used in some jurisdictions to measure the skills and competences of higher education students and graduates in a comparable manner.

In the United States, for example, the CLA and CLA+ tests have been deployed widely to test generic competences (CAE, 2018[10]), while in Mexico, the Exámenes Generales para el Egreso de Licenciatura (EGEL) are used by many institutions to test graduates in specific disciplinary areas (CENEVAL, 2018[11]). In Colombia, all higher education students are required to take a general competence test (Saber Pro) in order to graduate (ICFES, 2018[12]). Although the Saber Pro exams in Colombia are compulsory, the results obtained by students are not used directly to generate quality scores for the institutions they attended. As discussed in Chapter 5, the ENADE examination in Brazil is the only example, in a major higher education system, of large-scale, external examinations that are both compulsory for students and used directly in the quality assurance of programmes and institutions.

Other output or outcome related measures do not look at student learning per se, but rather at indirectly related issues. For outputs, this includes graduation and completion (e.g. proportion of students successfully completing their course). For outcomes, this includes employment outcomes (e.g. proportion of graduates that are employed and in what types of job).

The relationship between output and outcome measures and course quality is not always straightforward. Although a high-quality course may be expected to provide good support to students from different backgrounds to allow them to complete their course successfully, a 100% completion rate may be an indication of low standards, rather than good quality. While it is logical to assume that high quality courses prepare students well to get good jobs, graduate employment outcomes depend on a wide range of factors beyond the quality of the educational programme. Graduates from a prestigious, but objectively poor quality, course may consistently succeed in getting good jobs. Graduates from high quality courses may have difficulty in finding appropriate work if the relationship between the course content and knowledge and skills required in the labour market is weak or general employment conditions are difficult.

Measuring the quality of postgraduate education may present specific challenges. Although the quality of taught Master’s programmes is often assured using the same types of indicators as for undergraduate education, the quality of research-oriented Master’s and doctoral programmes is also influenced to a great extent by the broader research environment in which they take place. Assessment of the quality of postgraduate provision may therefore consider research-related input, process and output indicators. These can include the research performance of the academic department hosting the programme (input), opportunities for postgraduate students to attend conferences or organise and participate in research-related events (process) or the number and quality of research outputs by students (output). In a world where postgraduate students increasingly go on to work outside academia and scientific research, however, the quality indicators used need to adapt to take this into account.

2.4. An analytical framework for the review

The objectives of the review

The terms of reference for this review, agreed with the Ministry of Education at the start of the project, call on the review team to assess the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the external quality assurance procedures applicable to undergraduate and postgraduate programmes and HEIs in the federal higher education system in Brazil. Specially, the terms of reference ask the team to consider the effectiveness and efficiency of the systems in a) ensuring minimum quality standards (basic accountability); b) providing differentiated measurement of quality (between types of provision and levels of quality offered) and; c) promoting improvement of quality and quality-oriented practices in HEIs (quality enhancement). The team was invited to provide an analysis in relation to these points and recommendations for improving the systems in place.

Disaggregating the different components of the quality assurance system

As illustrated by the earlier discussion, the procedures for external quality assurance system in the federal higher education system comprise a set of distinct processes for HEIs, undergraduate programmes and stricto sensu postgraduate programmes. For each of these, specific procedures exist governing:

-

1. “Market entry” for new institutions and programmes, based on ex-ante assessment of the likely quality of the institution or programme proposed (before they begin operation);

-

2. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of quality for existing institutions and programmes and;

-

3. The provision of feedback to programmes and institutions and actions to taken to respond to quality problems detected through the evaluation processes, including sanctions.

These three stages of quality assurance, which bring together the regulatory and supervisory functions of SERES, the evaluation function of INEP and the combined evaluation and supervisory roles of CAPES, are illustrated in Figure 2.2.

The review set out to analyse all of these components. Taking into account the way the different components are organised in practice and related to each other, they have been grouped and analysed as follows:

-

1. Market entry for new HEIs and new undergraduate programmes (SINAES evaluation by INEP and regulatory decisions by SERES) – analysed in Chapter 4 of this report.

-

2. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of existing undergraduate programmes and related feedback and corrective measures (SINAES evaluation by INEP and regulation and supervision decisions by SERES) – analysed in Chapter 5.

-

3. Market entry and periodic evaluation of stricto sensu postgraduate programmes and related feedback and corrective measures, coordinated by CAPES – analysed in Chapter 6.

-

4. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of HEIs and feedback and corrective measures (SINAES evaluation by INEP and regulation and supervision decisions by SERES) – analysed in Chapter 7.

In addition, Chapter 8 of this report analyses the governance and administrative bodies and arrangements that have been created to implement and oversee the processes outlined above.

An evaluative framework to structure the analysis

The terms of reference for the review specify basic evaluation criteria, which should structure the assessment of the components of the higher education quality assurance systems set out above:

-

1. The analysis of the relevance of the procedures and governance arrangements needs to consider the extent to which the objectives of these procedures and arrangements respond to the challenges and requirements of the Brazilian context. The objectives of processes and arrangements may be specified explicitly in legislation or be implicit in the approaches taken to implementation.

-

2. The analysis of the effectiveness of the different aspects of the system focuses on the extent to which they achieve their explicit and implicit objectives in practice.

-

3. The analysis of the efficiency of the different aspects of the system considers the relationship between the resources committed to the processes and bodies and results and impact achieved.

These are the core criteria used in many policy and programme evaluation frameworks used by national and international bodies, including and UNESCO and the OECD (UNESCO, 2007[13]; OECD/DAC, 2018[14]). The assessment of effectiveness is often complemented by consideration of the wider impact of policies and programmes, in an attempt to capture effects beyond the immediate outputs of the policy or programme in question. A full analysis of the results and impacts of the Brazilian external quality assurance system would be methodologically challenging in the absence of any counter-factual situations (higher education not subject to the quality procedures being examined). In any case, such an impact analysis is beyond the scope of this review. Nevertheless, the review team has sought to consider the wider effects of the quality assurance system, to the extent possible.

As noted, the review assesses the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency (and wider impact) of the higher education quality assurance system in Brazil using two main types of judgement criteria:

-

1. Domestic criteria, which are based on objectives, viewpoints and evidence encountered in Brazil, including the explicit objectives of the Brazilian legislation and stakeholder perceptions about effectiveness and efficiency and;

-

2. International criteria, which take into account international standards and guidelines for effective external quality assurance in higher education and examples of effective practice in other jurisdictions.

Many variables can affect the design of quality assurance systems in higher education. National contexts have a strong impact on how quality assurance systems are configured and there is no one-size-fits-all institutional model of good practice. However, the analyses of various international associations working in the field of quality assurance in higher education point to a growing international consensus around a set of principles that can guide the design of effective external quality assurance. Based on existing international guidelines and available literature, some of the key attributes one might expect to see in an effective external quality assurance system, and their relationship to relevance, effective and efficiency, are summarised in Table 2.2 below.

Key questions will be addressed for each component of the quality assurance system

The domestic and international judgement criteria have been used to inform the analysis and conclusions in the subsequent sections of this report. For each component of the Brazilian external quality assurance system for higher education (grouped above), the report addresses the following key questions:

-

1. Relevance: Are the objectives of this component of the quality assurance system clear and relevant to needs in the Brazilian context?

-

2. Effectiveness: Does this component of the system use appropriate indicators (measures) of quality that would allow it to measure quality in line with the Brazilian legislation and international good practice?

-

3. Effectiveness: Is responsibility for assuring the quality of higher education appropriately distributed between higher education providers and external authorities and between different external authorities in this component of the QA system, taking into account the objective of Brazilian legislation and international experience?

-

4. Effectiveness: Is the information about quality collected / assembled in this component of the system used well to inform effective decisions about quality, promote quality improvement or increase transparency, in line with Brazilian legislation and international good practice?

-

5. Effectiveness: Is this component of the system able to adapt flexibility to accommodate change and does it actively promote innovation?

-

6. Efficiency: Is this component of the system efficient in line of the resource committed and the effects generated. Is it cost effective and does it maintain administrative burden at a minimum?

References

[7] Brunner, J. and D. Miranda (2016), Educación Superior en Iberoamérica - Informe 2016 - Aseguramiento de la Calidad, Centro Interuniversitario de Desarrollo (CINDA), Santiago de Chile, http://www.cinda.cl (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[10] CAE (2018), CLA+ for Higher Education, Council for Aid to Education, https://cae.org/flagship-assessments-cla-cwra/cla/ (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[11] CENEVAL (2018), Exámenes Generales para el Egreso de Licenciatura (EGEL), CENEVAL, http://www.ceneval.edu.mx/examenes-generales-de-egreso (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[9] CHEA (2016), The CIQG International Quality Principles: Toward a Shared Understanding of Quality, Council for Higher Education Accreditation , Washington, DC, http://www.chea..

[8] ESG (2015), Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG).

[12] ICFES (2018), Información general del examen Saber Pro, Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación, http://www2.icfes.gov.co/estudiantes-y-padres/saber-pro-estudiantes/informacion-general-del-examen (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[15] INQAAHE (2016), INQAAHE Guidelines of Good Practices 2016 - revised edition, International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE), Barcelona, http://www.inqaahe.org/.

[5] MEC (2017), Decreto desburocratiza e premia instituições pela qualidade (Decree reduces bureaucracy and rewards institutions for quality), Ministério da Educação, http://portal.mec.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/212-educacao-superior-1690610854/58611-decreto-desburocratiza-e-premia-instituicoes-pela-qualidade (accessed on 12 November 2018).

[6] OECD (2008), OECD Reviews of Tertiary Education: Mexico 2008, OECD Reviews of Tertiary Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264039247-en.

[14] OECD/DAC (2018), DAC Criteria for Evaluating Development Assistance, OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm (accessed on 14 November 2018).

[2] Presidência da República (2017), Decreto Nº 9.235, de 15 de dezembro de 2017 - Dispõe sobre o exercício das funções de regulação, supervisão e avaliação das instituições de educação superior e dos cursos superiores de graduação e de pós-graduação no sistema federal de ensino. (Decree 9235 of 15 December 2017 - concerning exercise of the functions of regulation, supervision and evaluation of higher education institutions and undergraduate and postgraduate courses in the federal education system), http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2017/Decreto/D9235.htm (accessed on 10 November 2018).

[4] Presidência da República (2006), Decreto nº 5773 de 9 de maio de 2006, Dispõe sobre o exercício das funções de regulação, supervisão e avaliação de instituições de educação superior e cursos superiores de graduação e seqüenciais no sistema federal de ensino. (Decree 5773 concerning the exercise of the functions of regulation, supervision and evaluation of higher education institutions and undergraduate and short-cycle programmes in the federal education system), http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2004-2006/2006/Decreto/D5773.htm (accessed on 12 November 2018).

[1] Presidência da República (2004), Lei no 10 861 de 14 de Abril 2004, Institui o Sistema Nacional de Avaliação da Educação Superior – SINAES e dá outras providências (Law 10 861 establishing the National System for the Evaluation of Higher Education - SINAES and other measures), http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2004/lei/l10.861.htm (accessed on 10 November 2018).

[3] Presidência da República (1996), Lei Nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. (Law 9394 establishing basic guidelines for national education), http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L9394.htm (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[13] UNESCO (2007), Evaluation Handbook, UNESCO Internal Oversight Service Evaluation Section, Paris, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001557/155748E.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2018).

Notes

← 1. Undergraduate education (graduação) in Brazil encompasses a) 4-6-year Bachelor's degrees (Bacharel), which are academically oriented and account for the majority of enrolment; b) Licentiate's degrees (Licenciado), which are 3-4-year teacher training qualifications and; c) professionally oriented, 2-3-year Advanced Technology Programmes (Cursos Superiores de Tecnologia). All of these qualifications are classified as ISCED 6.

← 2. Public HEIs have de facto accredited status through their acts of establishment, but formally require periodic re-accreditation.

← 3. Postgraduate education in Brazil encompasses a) academic Master’s degrees; b) professional Master’s degrees; and c) doctoral degrees. These qualifications are classified as stricto sensu postgraduate degrees and classified respectively as ISCED 7 (academic and professional Master’s) and ISCED 8 (doctoral degrees). In addition, many higher education institutions in Brazil offer professionally oriented postgraduate qualifications referred to as Specialisation degrees (Cursos de especialização em nível de pós-graduação). These are classified as lato sensu qualifications, which do not give access to doctoral degrees and are not evaluated by CAPES.

← 4. The terms ‘output’ and ‘outcome’ are not used consistently in literature about education systems and educational performance. In this report, qualified graduates with additional knowledge and skills are classed as an output of the educational process. Outcome is used primarily to refer to the subsequent labour market outcomes of graduates.