Chapter 6. Government communication and trust

This chapter explores the relationship between different communication models and trust in government institutions in Korea.* Based on results from the OECD-KDI survey it argues that for achieving higher institutional trust levels the following features in government communication are essential: democratic governance values; commitment by government leaders to build a horizontal relationship with its citizens; using the right channels; clear ground rules; resource capacity; and principles of transparency and fairness.

* This chapter was drafted by Taejun (David) Lee and Soonhee Kim from the KDI School of Public Policy and Management.

This chapter focuses on government communication effectiveness as a factor affecting public trust in government in Korea. The growing body of public administration literature on governance makes it clear: in order to resolve complex 21st century governance problems, government leaders need to build partnerships with citizens and communities and work collaboratively (Kettle, 2000; OECD, 2009; O'Leary and Bingham, 2008). When governance actors build trust and rely on civic norms, all levels of government are better able to implement policies effectively, provide high-quality services and make government innovation efforts more feasible and legitimate (Knack, 2002; Robert, Robert and Raffaella, 1993; Cleary and Carol, 2006). Scholars and practitioners posit that trust in government encourages compliance with laws and regulations and enhances the legitimacy and the effectiveness of democratic governance (Ayres and Braithwaite, 1992; Hetherington, 1999; OECD, 2017).

Considering the need for public trust in government to facilitate effective collaboration between government and civil society, there are complex challenges to overcome – and creative solutions to find. Previous chapters of this report emphasize that Korean government agencies should demonstrate their commitment to competence (i.e. responsiveness and reliability) and public values (i.e. integrity, openness and fairness) as a valid strategy for enhancing public trust in government.

In order to apply the OECD Trust Framework to the specific governance setting of Korea, both scholars and practitioners should consider how Korean citizen assess the key drivers of trust in government. This chapter poses the following research question: how do citizens’ assessments of the effectiveness of Korean government agencies at communication correlate with citizens’ perceptions of the key drivers of trust in government (i.e. competence and public values)? It concludes that citizens’ assessment of government communication effectiveness could be an important factor indirectly affecting public trust in government, through its effects on public perceptions of Korea’s public policy competence. In order to enhance government communication effectiveness, this chapter further analyses how national government agencies can reform their communication approaches to meet citizens’ expectations of active information sharing, two-way communication and participatory decision-making.

Based on the paradigm of participatory, deliberative and collaborative governance as a new way of connecting government and citizens in the 21st century (OECD, 2009), government agencies must determine the best communication approaches for diverse stakeholders in the context of Korea’s complex public policy settings. In light of declining trust and increasing demands for transparency in government in Korea, what communication strategies should they consider? Which ones will improve relationships with citizens, and lead to greater citizen participation and policy legitimacy?

Beyond Korea’s legacy of transforming e-services and transparency through e-government (Karippacheril et al., 2016), public institutions face a daunting challenge: how best to use the emerging digital media ecosystems to communicate with the target population and stakeholders – both in formulating policies and during the ongoing policy process – in a complete, clear, conspicuous, timely and intentional manner.

In parallel to the data collection for this report the Korean government was also seeking to build better government communication mechanisms. For example, it carried out an assessment of the overall government communication effectiveness at agency level, as part of managing government agencies’ performance (Kim and Moon, 2008; Kim, Cheong and Kim, 2014). As mentioned later in this chapter, several executive agencies were engaged in reforming agency-government communication mechanisms to better communicate with citizens. However, research is limited on citizens’ assessment of overall communication effectiveness at national government agency level, and this under-explored theme is worth further analysis.

This chapter uses six indicators of government communication effectiveness, described below. The chapter first analyses citizens’ assessment of government communication effectiveness at national government agency level. It then analyses how this assessment affects citizens’ perceptions of the competency and values of public institutions, which are drivers of public trust (See Chapter 2). Next, in order to find policy action recommendations to enhance government communication effectiveness, the chapter analyses cases of reform in government agencies to strengthen communication effectiveness.

Effective government communication matters for governance

Beyond a narrow definition of government communication as a process of informing relevant stakeholders and communities about public policy decisions, this chapter defines government communication as a systematic two-way communication process between government agencies and citizens at every stage of the public policy process – including agenda setting, decision making, policy implementation and monitoring and feedback. In an era of increased focus on governance, government communication is an important mechanism for facilitating relationships between government agencies and citizens in various communities.

Transforming from a closed system of public administration to an open system of collaborative governance inevitably leads practitioners to consider the relationship between states and citizens as a partnership, rather than a vertical relationship (OECD, 2009). However, a country like Korea – with its long history of Confucian culture and the legacy of government-led economic and social development – may find it particularly challenging to establish a horizontal relation between state and citizens (Kim, 2010). Therefore, the best approach could be a systematic government communication strategy, experimenting with various communication channels throughout the public policy process, to indirectly affect trust in public institutions through its effects on citizens’ perceptions of government competence and values.

A government communication strategy in a democracy needs to develop the competency of both public managers and citizens engaged in the communication process (OECD, 2009). It is essential to take government communication seriously in order to govern effectively, and urgent to determine how to build communication capacity for government employees and citizens in an era of collaborative governance. The Korean government must also develop flexible communication patterns, by constantly adapting the nature and tone of conversations to suit their context, both for government employees and citizens (Bartels, 2014).

From a citizen standpoint, the benefits of government communication can have several dimensions: information, empowerment, education, development, discussion and decisions. Government bodies provide citizens with information to try to enhance their perceptions, evaluations and choices, in order to improve the quality of citizen decision making. Since ordinary citizens have limited information about government and public policy, the primary reason for government communication by agencies is to ensure a supply of balanced information on public policy issues, changes and related resources. However, the success of government communication can only be judged to the extent that citizens notice and understand such information (Laing, 2003; Meijer, 2013; Sanders and Canel, 2015).

Alternatively, poorly designed government communication programmes that do not assess the context of specific policy issues and core stakeholders negatively affect government performance, policy effectiveness and governance values (Gelders, Bouckaert and van Ruler, 2007; Bouckaert and Van de Walle, 2003; Carpenter and Krause, 2012). Both academics and practitioners note the complexity of designing and evaluating various government communication programmes in different political systems (Laing, 2003; Liu et al., 2010). Government officials face the challenge of designing customised government communication programmes of various types, formats, and purposes, while keeping in mind the tensions of resource constraints and the complexity of engaging with diverse policy issues and stakeholders. More specifically, the relationship between the process of government communication and its effects have yet to be tested in the context of specific government communication programmes, governance values and political cultures in different countries (Froehlich and Rüdiger, 2006; Hong et al., 2012; Froehlich and Rüdiger, 2006; Hong et al., 2012; Waymer and Heath, 2015).

Government communication is a systematic two-way process between government agencies and citizens during a public policy process, including the stages mentioned above: agenda setting, decision making, policy implementation and monitoring and feedback. In order to analyse citizens’ overall assessment of government communication, this study uses six indicators, based on theory – and widely used as a performance measurement framework of government communication, as well as its guiding principles. They are: 1) symmetrical-ethical communication; 2) two-way communication; 3) informative communication; 4) transparent communication; 5) procedural fairness through communication; and 6) risk and crisis communication. Each indicator is examined in more detail below.

Symmetrical-ethical communication

While asymmetrical communication is an imbalance between a governmental organisation and the public, symmetrical communication focuses on keeping the balance between an organisation and the public (Grunig, Grunig and Dozier, 2002; Moynihan and Soss, 2014; Grunig, Grunig and Dozier, 2002; Grunig and Todd, 1984). Government organisations that promote symmetrical interaction see communication as a relational interplay, in which two or more actors construct beliefs, attitudes, value systems, choices and decisions together, so that they behave in ways that are symbiotic (Waymer, 2013; Kent, Taylor and White, 2003; Grunig and Grunig, 2006). In Korea, the public sector has rooted itself in a symmetrical-ethical worldview by striving to promote consensus building, interdependence and a holistic approach as ways to improve understanding (Lee, 2017; Moon and Park, 2014; Rhee, Kim and Lee, 2013).

Summarising the literature, symmetrical-ethical government communication reflects government organisations’ values about how to behave in society, rather than simply providing more sophisticated strategic management tools to manipulate the public. Symmetrical-ethical communication, as reflected and respected in the Korean public sector, aims to foster mutual trust and dialogue as a path to understanding in policy process and public governance (Choi and Han, 2014; Hwang, Moon and Lee, 2014). Together, symmetry and ethics in Korean government communication are about balancing the interests of organisations and the public, emphasising the government organisation’s moral duty to engage in deliberative discourse with the public when it comes to problem solving and decision making.

Two-way communication

While one-way communication or “monologue” disseminates information and persuasive messages, two-way communication or “dialogue” exchanges information and meaning (Grunig, Grunig and Dozier, 2002; Sanders and Canel, 2015; Gilad, Maor and Bloom, 2015). The presence of feedback and dialogue in a communication process are keys to distinguish two-way communication from one-way communication, and this applies in Korea (Grunig and Hunt, 1984; Grunig and Grunig, 2006).

Specifically, feedback is a process that encourages communicators to share the thoughts and behaviours involved in government communication and decision-making processes (Kent et al., 2013). However, it is still possible that an information provider will manipulate audiences’ opinions on public problems and policy issues due to a lack of information symmetry, value co-orientation or co-operative decision making (Bartels, 2014; Laursen and Valentini, 2015; Ni and Wang, 2011; Gilad, Maor and Bloom, 2015).

Fortunately, information and communication technology (ICT) has evolved in a way that can maximise two-way interaction between the government and the Korean public. In this ecosystem, Korean governments can listen in a timely and efficient way to citizens and communicate with them on a regular basis. At the same time, Korean citizens can also use ICT to create and deliver proposals, requests, opinions, or ideas to government entities. Korea’s public sector has become more willing recently to adjust and balance ideas, opinions, decisions and behaviour between government and public, through a negotiated dialogue using ICT, rather than its former bureaucratic, vertical communication with citizens (Chung, 2017; Kim and Moon, 2008; Rhee, Kim and Lee, 2013).

Informative communication

One of the primary objectives of government communication is to aid citizens and stakeholders in deliberation, participation and collaboration (Piotrowski and Van Ryzn, 2007; Waymer, 2013). The potential benefits of government communication can only be achieved to the extent that citizens notice and understand its content. Effective government communication involves the interplay between information provision on the senders’ side and use of information on the audiences’ side.

Government officers must consider the audience when creating policy information in order to facilitate understanding (Kim and Lee, 2012; Reynaers and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2015). In other words, government communication should be perceived as providing credible information that explains policy decision making (Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch, 2012; Lee, Yun and Haley, 2017).

Empirical studies have found that Korean citizens increasingly expect government communications to be useful, and have more confidence in the institutional role of government when its communication is perceived as credible and informative (Kim, et al., 2014; Hwang et al., 2014). Moreover, a stream of research in Korea supports the notion that citizens who find government messages helpful are more likely to develop favourable attitudes toward a given public policy and its related organisations (Chung, 2016, 2017; Lee, 2016). Government communication and policy messages deemed informative received more attention. This suggests that informative government communications were perceived as more useful and therefore improved citizens' opinion of government.

Transparent communication

Transparency is vital to creating new mechanisms and institutions with higher standards of decision making. Transparency enhances the legitimacy of government decisions, by widely disseminating information about public sector decision processes, procedures, functioning and performance (Heald, 2012; Meijer, 2013; Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2014; Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2014).

Furthermore, a crucial element of transparency is making the necessary information available to engender active disclosure, inward observability, critical scrutiny and increasing accountability by the outside world (Grimmelikjuijsen, 2012; Welch, 2012; Meijer, Curtin and Hillebrandt, 2012). Transparency is the principle that enables the public to obtain information about the operations and structures of a government entity and allows people to monitor and assess the government’s internal workings and/or performance outcome (Piotrowski and Van, 2007). The concept of transparency includes visible, inferable information that is easily accessible, can be correctly understood by the public and allows people to derive accurate conclusions (Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch, 2012; Reynaers and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2015; Welch, Hinnant and Moon, 2005).

Therefore, transparent communication in Korea’s public sector requires government organisations to make publicly available all policy information that can be released legally – whether positive or negative in nature – in a manner that is accurate, timely, balanced and unequivocal (Lee and Chung, 2016; Kim and Moon, 2010). In particular, as citizens’ diminishing interest in public affairs and lower levels of trust in government institutions are mostly due to maladministration and perceived high level corruption, Korean governments should practise transparent communication to achieve accountability, legitimacy and trust, as well as to combat high level corruption (Kim and Lee, 2012; Grimmelikhijsen et al., 2013).

The purpose of a transparent communication process is not merely to increase the flow of information, but also to improve public understanding (Lee, 2016). Disclosed policy information should meet the requirements of truthfulness and completeness; and the key to obtaining substantial completeness is anticipating what target audiences need to know (Lee, 2016).

Procedural fairness via communication

Citizens’ perceptions of government procedures as fair, through engaging with government communication, is a main source of policy legitimacy in public institutions (Bingham, Nabatchi and O'Leary, 2005; Webler and Tuler, 2000). Citizen acceptance or support of government decisions and policy actions increases when they feel that communicative procedures are participatory and fair (Kim, 2017; Shin and Lee, 2016). Additionally, there is considerable evidence that overcoming citizens' cynicism about government communication is essential to developing governance capacity and communication effectiveness in the public sector (Chung, 2016; Lee, 2017).

Recently, Korean government organisations have recognised that demonstrating procedural fairness via government communication means maintaining good quality relationships and citizen participation (Moon and Park, 2014; Rhee, Kim and Lee, 2013). Treating citizens fairly and with respect and giving them a voice can strengthen citizen–government relationships; this in turn cultivates social capital in community, society and culture (Kent, Taylor and White, 2003; Welch, 2012).

There is also emerging evidence that citizen observation and participation in fair procedures facilitated by government communication services helps improve transparency in government and government policy (Liu and Horsley, 2007; Moynihan and Soss, 2014). As discussed earlier, the transparency of an organisation can be measured by policy stakeholders’ perceptions of incorporating their point of views into determining what and how much information they really need, and how well government organisations are fulfilling that need.

Procedural fairness and equal treatment also require government accountability and inclusiveness in Korea (Chung, 2017; Kim, Jeong and Park, 2015). In many Korean contexts, government organisations continue to be accountable for their words, actions and decisions. Communication services towards all stakeholders with whom the government serve and interact are designed to foster partnership, with the private sector and members of the public (Choi and Han, 2014; Kim et al., 2015; Lee and Choi, 2014). To this end, Korean government organisations strategically exploit new media technology, including social media, in order to allow citizens to provide feedback that develops shared values and improves governance policies and practices. This ICT-based approach can enhance trust and satisfaction with services in the public sector.

Risk and crisis communication

The quality of relationship between governments and citizens is influenced by man-made crises such as industrial accidents, foodborne illnesses, corporate malfeasance or terrorist attacks; and by natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods or infectious diseases. The broad range of health issues from chronic diseases to emerging and novel risks are increasing in intensity with effects cascading beyond national borders, triggering economic changes and deteriorating environmental conditions coupled with climate change and shocks to society (OECD, 2017). Risk communication serves to inform citizens and businesses of potential exposure to hazardous events before they occur, and to encourage investment in precautionary measures that avoid, reduce, or transfer risks.

The four core objectives of risk communication suggested by the OECD (2017) are:

-

Inform people of risks and how to handle them.

-

Teach people to change their behaviour and habits to reduce risks to wealth, health and happiness.

-

Enhance the confidence of public institutions that are in charge of risk assessment and management.

-

Build a governance structure capable of inviting the public and stakeholders to participate in the decision-making process and resolve conflicts involved in risk assessment and management.

Once a hazardous event has begun or just occurred, crisis communication directs its audience to take specific actions (OECD, 2017). Crisis communication is a fundamental component of a sound governance framework that builds and develops more robust societies and economies. Governments have a basic responsibility to identify, monitor and anticipate critical hazards and threats via risk analysis (Jaque, 2009; Sellnow et al., 2015). For example, in terms of crisis prevention, Jaque (2007) addresses that public managers responsible for crisis communication keep investing in the institutional and strategic development of early warning and scanning – such as audits, preventive maintenance, issue monitoring, social forecasting, environmental scanning, anticipatory management and future studies (Jaque, 2007, 2009). In addition, the following can be useful, timely information resources: leadership surveys; media content analyses; public opinion surveys; legislative trend analyses; participation in trade associations; literature reviews; conference attendance; social big data analytics (computer-based issue monitoring), monitoring key websites and social media, and chat-group analysis (Avery et al., 2010; Yang, Aloe, and Freely, 2014).

Government, in partnership with other key actors, should continually improve public awareness of critical risks to ensure that communities are stable and secure in times of crisis (Sellnow et al., 2015). Crisis communication also gives timely support to governments in developing an adaptive, agile approach to mobilising and co-ordinating households and business, inter-agency and international stakeholders to manage critical risks and emergencies (Bakir, 2006; Yang, Aloe and Freely, 2014).

Finally, crisis communication strengthens the qualities that are needed to cope with unplanned cataclysmic events and their impacts: crisis leadership, capacity to understand a crisis situation, informed decision-making and public budget flexibility. To this end, government should incorporate evidence-based participatory communication and learning from experience into governance practices for national resilience and responsiveness, as a way to foster trust in government (Jaque, 2007, 2009).

Against this backdrop, Korean government institutions could emphasise an integrated approach to risk and crisis communication to empower citizens and stakeholders to take action swiftly to avoid and minimise risks, minimising the consequences of emergencies.

For instance, the Korean government should make optimal use of interactive media channels and social media for risk and crisis communication. Social/mobile media helps disseminate information rapidly through different channels, as a horizontal, decentralised and relationship-focused communication tool. This helps to target information and adapts communication strategies to particular audiences’ contexts. It also promotes a more interactive exchange of relevant information among stakeholders, directly or indirectly affecting risk and crisis policy decisions and implementation processes (Chung, 2016; Lee and Choi, 2014). At the same time, governments play the role of information intermediary, monitoring the accuracy of information flow among the public by using ICT as an effective means of risk and crisis intervention (Kim, Jeong and Park, 2015; Lee and Kim, 2015).

Sample and procedures

Based on the dimensions of government communication effectiveness outlined above, this study developed the following methods for measuring government communication effectiveness in the context of Korean society. Similarly to previous chapters, the evidence presented here comes from the 2016 OECD-KDI trust survey fielded in early 2016 to 3000 Korean households. Descriptive statistics of the survey are presented in Table 6.1. In turn, these variables are used as control variables to analyse the relationship between the assessment of government communication and citizens’ perceptions of the key drivers of trust in public institutions (i.e. competence and values).

Measurement

In this study, all variables were measured using multiple item scales. Table 6.2 summarises all the measurement items of policy effectiveness dimensions as well as the measurements of drivers of trust in public institutions. This study employed a ten-point Likert scale in order to optimise the measure of population variances in the variables, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 10 indicated “strongly agree”. All survey questions used to measure all variables of the current study, and the results of the reliability tests with Cronbach’s alpha, are presented in Table 6. 2.

Findings: Citizen assessment of government communication effectiveness

Variations in demographic characteristics

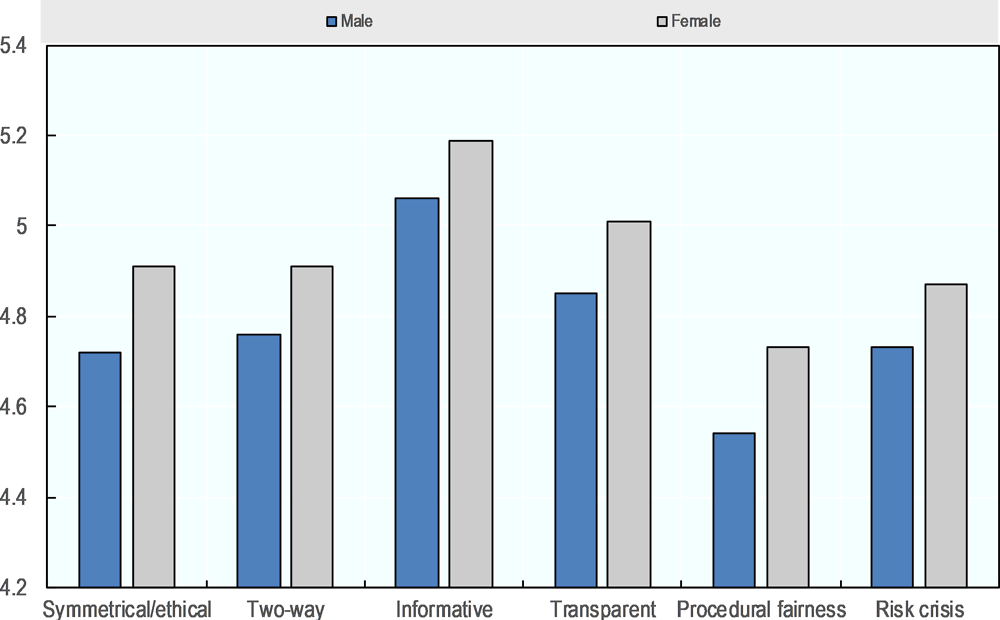

Table 6.3 and Figure 6.2 show the gender differences in assessing government communication constructs. Regarding all constructs of government communication effectiveness, females perceive the Park Geun-hye government’s communication efforts and activities (February 2016) to be more effective than males do. Interestingly, as mentioned earlier, women participants expressed slightly higher trust in institutions, even though gender was not a statistically significant factor for trust in public institutions.

However, both female and male participants gave higher scores on for the informative dimension of government communication. In addition, both male and female participants in the survey gave the lowest assessment score for procedural fairness in government communication.

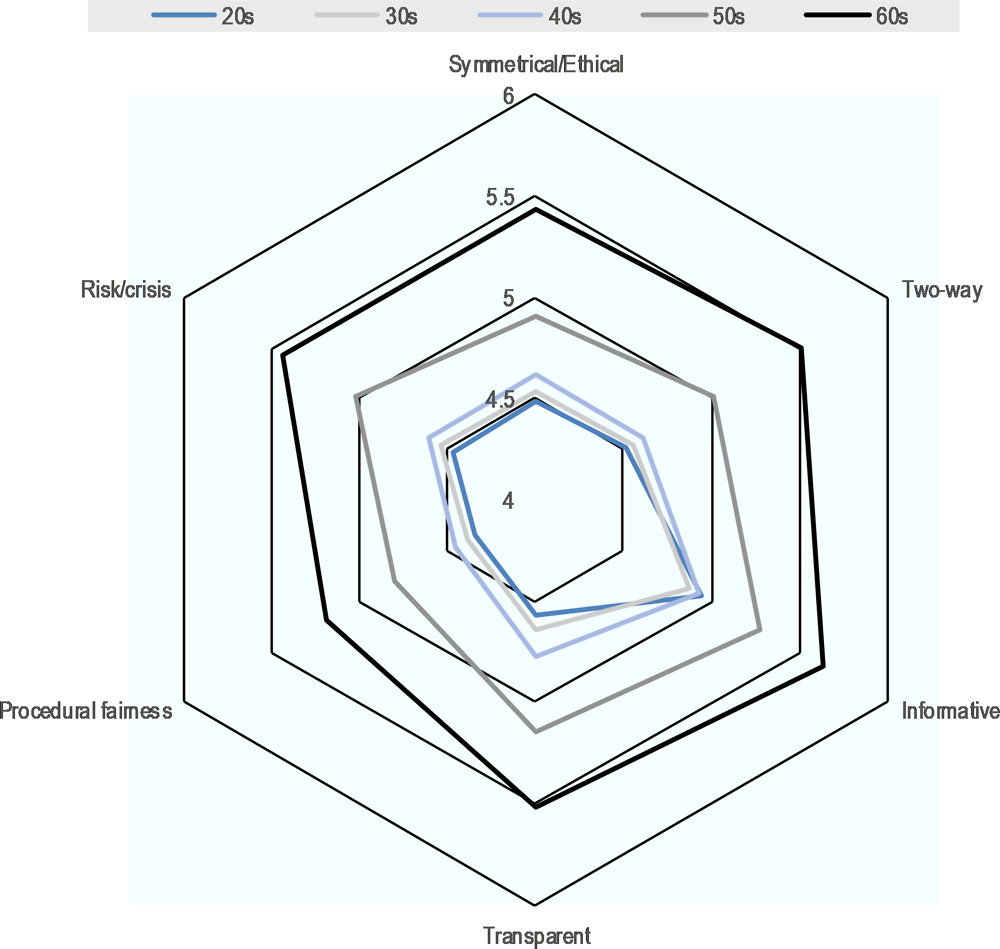

Table 6.4 and Figure 6.3 show the overall age differences in assessing government communication constructs. The group aged 60 and above indicates the highest scores for government communication effectiveness, more than any other group for all constructs. Except for informative communication (where the 20s age group is the second highest), the perception of those in their 50s is more positive than those in their 40s, 30s and 20s. Interestingly, these “generation gap” findings are similar to the findings of trust in public institutions by generation. Overall, public trust in government data show that older citizens express higher levels of trust in government than the younger generation.

The OECD-KDI trust survey analysed earlier confirms this gap. As depicted in Figures 6.5 and 6.6, people in their 20s and 30s not only express the lowest levels of perceived trustworthiness in public institutions, but also the lowest levels of government communication effectiveness. Maybe due to easy access to ICT tools and advanced e-government websites, the 20s and 30s gave relatively high scores for the informative dimension. However, their assessment of the other dimensions was lower than that of all the other age groups. These findings imply that meeting the communication expectations of younger generations could be a challenging policy agenda for government agencies.

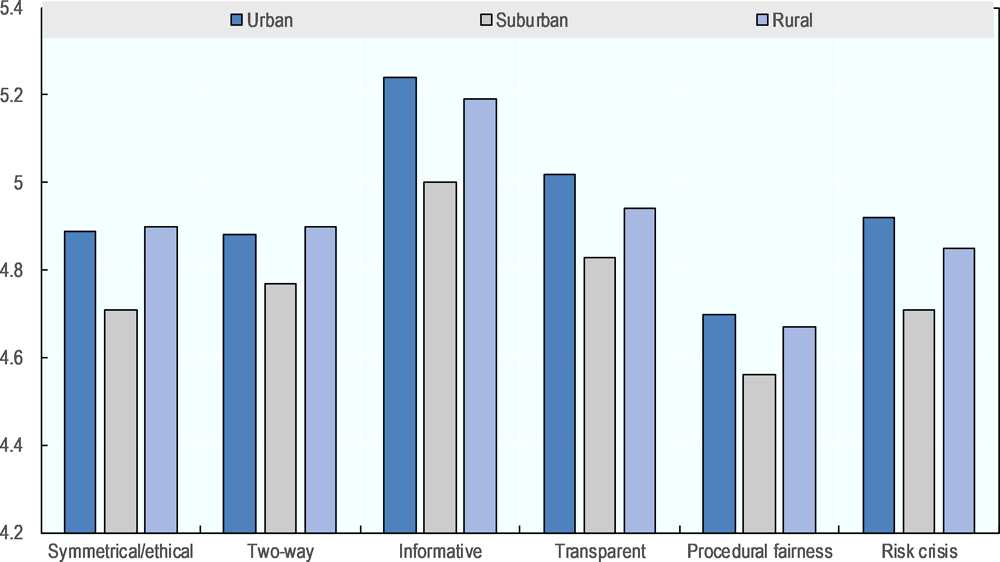

Table 6.5 shows group differences by place of residence (or home location) on government communication constructs. There are significant differences between the assessments of symmetric-ethical, informative, transparent, and risk-crisis communication among groups living in urban, suburban or rural locations, while there are no differences in assessing two-way and procedural fairness communication.

As indicated in Figures 6.8 and 6.9, the findings also indicate that government agencies need to pay more attention to people in suburban areas; they gave the lowest scores for government communication effectiveness, including symmetric-ethical, informative, transparent and risk-crisis communication.

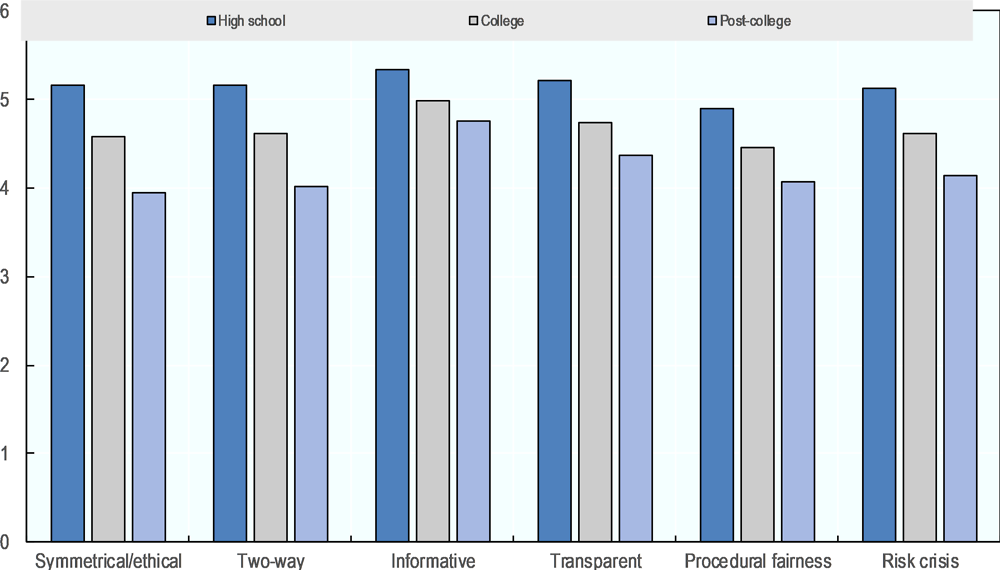

Table 6.6 and Figure 6.5 show group differences by education level in assessing government communication constructs. People educated to high-school graduate level evaluate government communication as more effective than those educated to college or post-college level for all constructs. Considering the growing college-educated population in Korea, government agencies now have the challenges of meeting their expectations of better government communication in all six dimensions.

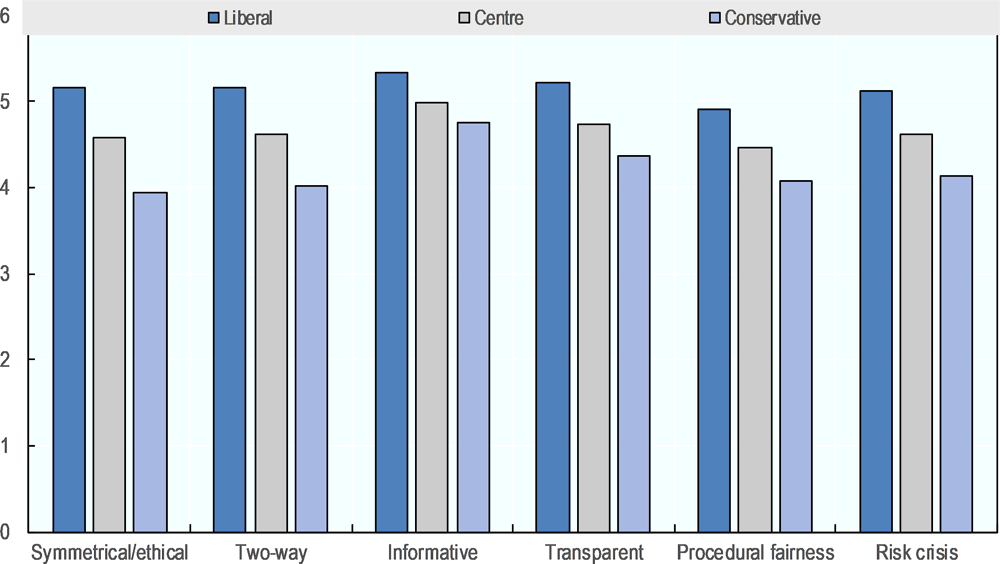

Table 6.7 and Figure 6.6 show group differences by political orientation in assessing government communication constructs. Specifically, people with a conservative political ideology see all constructs of government communication as more effective than those with central and liberal orientations. It is worth noting that this finding shows a similar tendency to that of trust in public institutions by political ideology. As mentioned earlier, survey participants with conservative political views express greater trust in public institutions.

Opportunities for policy action

Improving government communication in Korea: Gaps and opportunities

Improving symmetrical-ethical communication

While government organisations in Korea have recently started to consider the impact of how they communicate on colleagues, clients, organisations and wider society, it is crucial to emphasize that they should adhere to high ethical standards when communicating. Indeed, the symmetrical-ethical model could be a useful tool to promote dialogue between organisations and their public while keeping integrity at the centre of problem solving.

Box 6.1 offers examples of the government applying symmetrical-ethical communication to certain issues.

Government 3.0 Design Group is a team of government officials, citizens and service designers that reinterprets and develops public policy from a citizen’s perspective. Its main role is to enhance the effectiveness of government policy. The design group was formed for one particular topic, but the practice of re-interpreting policy from the citizen’s point of view during policy development became embedded in service design methodologies. In 2015, the design group was shown to achieve policy improvements in 67 cases, mostly (80.6%) in creating new types of public services (information collection, welfare facilities, programme content development and environmental activities) and in improving the service delivery process (19.4%; public policy regulation, administrative processes, career and start-up programmes). This government-citizen-expert collaboration has also improved participants’ perceptions of government. In 2016, the Government 3.0 Design Group was nominated for a gold award in the service design sector of the iF Design Awards 2016, held in Germany. Minister of the Interior in Korea commented, “the Government 3.0 Design Group demonstrated a creative role model for policy makers, experts and citizens to participate in efforts to improve public services.”

e-People. The Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC) of the Republic of Korea is in responsible for handling complaints and petitions via the e-People online portal system (www.epeople.go.kr). Through this portal, people can express their opinions on unfair or ineffective administrative handling, infringements of their rights and interests, improving institutions and policies; all governmental administrative organisations link to the portal, through which they can receive and process people’s complaints and suggestions. Once submitted, people’s civil service requests are categorised into both “Anti-corruption and Civil Rights Commission” and “processing organisations” to define which organisation is responsible. ACRC recognises that e-People has contributed to improving administration efficiency and increasing citizen participation. Processing time has reduced by nearly half – from 12 days to 6.9 days per case between 2005 and 2008 – despite the number of suggestions soaring from 16,086 to 57,851. This effective handling of people’s requests has raised citizen satisfaction levels by over 20 percentage points to 51.2% within the same period. Alongside better government efficiency, the integrated system has helped to improve not only individuals’ lives but also to secure the public-sector transparency.

The Korean government keeps working to make communication effective in boosting public participation, collaboration and deliberation; and, moreover, leading to positive perceptions of public institutions and enhancing social capital between government and citizens. Some examples of the government using two-way communication follow.

The vision of the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) is “safe food and drugs, healthy people, happy society” for the people of South Korea. Recently, MFDS has been re-positioned as a friendly and well-known government organisation, thanks to employing “fourth industrial technologies – such as a 360° virtual reality web drama and a mobile phone-based augmented reality game, leveraging crowd-sourcing strategies (see Box 6.2). In this way, MFDS has been trying to move away from one-way to two-way communication between public and government, which has contributed to an increase in awareness of food and drug safety, and public agreement with food and drug safety policies.

360° virtual reality web-drama production

The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) in Korea has launched a web-drama production, Birth of a Professional, using VR (virtual reality) – the first time trial from a government organisation. The purpose of this was to provide practically reachable policy advertising promotion in the public with using new technology film contents. The 3D drama was screened at two renowned festivals for film and cartoons (the 21st Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival and the 21st Seoul International Cartoon and Animation Festival). The film story is about how newly employed staff at MFDS becomes a professional expert while dealing with adulterated foods.

A food poisoning augmented reality game

MFDS has created a mobile phone-based AR (augmented reality) game, “Sik-Jung-Dok-Jap GO” (means ‘catching food poison’ in Korean), which educates users how to prevent food poisoning. After playing the game, participants’ level of awareness on “three key methods of food poisoning prevention” increased on average by 53%.

MFDS has also distributed education guidelines to be used at kindergartens and elementary schools through 10 ministries (including the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Gender Equality and Family), 17 provinces and cities, and 6 agencies related to the food poisoning issue.

MFDS plans to distribute the AR game to other countries that need education on food poisoning prevention.

Improving informative communication

The nature of effective government communication is to provide appropriate information to its various audiences and boost interaction between them and/or with government. For this reason, government communication should be perceived by the public as understandable and useful. Box 6.3 provides an example of government efforts towards informative communication.

The Korea Broadcast Advertising Corporation (KOBACO) is an affiliate of the Public Service Advertising of the Korea Communications Commission (KCC). KOBACO carries out public service advertising campaigns to help form public consensus on government policies and major social issues. The essential feature of its work is to interact with people, entailing inclusive campaigning.

KOBACO and the Korea Advertising Council carry out surveys to identify major social issues and related public opinions; they then discuss the results and make them available to the public. The idea is to assess what the social agendas are and share this publicly. KOBACO also holds the Korea Public Service Advertising Festival, which aims to form a public consensus on social issues and promote awareness of good practice. At the festival they hold advertising competitions for primary school students, and exhibit award-winning advertising campaigns from Cannes, Clio and New York festivals. A variety of programmes in booths for the public to engage with demonstrate that everyone can freely communicate with and experience a public services campaign. KOBACO also runs campaigns for educational purposes, such as delivering public services advertising (PSA) classes and producing PSA textbooks.

Commitment to transparent communication

As a general rule Korean government organisations try to make their actions and decisions understandable to all interested parties. Transparent communication could be an effective way of increasing public trust in government, as it could influence the responsiveness and openness dimensions of the trust framework. As mentioned earlier, the purpose of a transparent communication process is not merely to increase the flow of information, but also to improve understanding. Thus, government communication should meet the requirements of truthfulness and substantial completeness. Some examples follow that show the government’s efforts towards transparent communication (see Boxes 6.4 and 6.5).

The Republic of Korea ranked as one of the top performers for budget transparency in the Asia Pacific Region and its score of 60 out of 100 is substantially higher than the global average score of 42, according to the Open Budget Index released in 2017. This is the result of years of continual effort. In 1987, the democratic transition highlighted the need for government fiscal transparency. The first transparency reforms were implemented under the president in the early 1990s, when a law mandated that high-level public officials must disclose their assets. However, widespread corruption in the public sector and many other financial scandals led to the financial turmoil of the “IMF crisis” in 1997.

Afterwards, the Korean government resorted to systemising its fiscal reform efforts and launched the Digital Budget and Accounting System (dBrain). The dBrain system aims to enable an accurate analysis of fiscal data and information, providing policy makers with real-time support for policy formulations. It aimed to improve the credibility of the national budget and to integrate and connect up the fiscal information system – not only for central and local government, but also public enterprises. The Korean government also created Open Fiscal Data (www.openfiscaldata.go.kr), which daily processing amount of money exceeds $5.1 billion, also handles 360,000 tasks daily, and approximately 55,000 civil servants use this system regularly at work, according to the Telecommunications Technology Association (TTA) 2013 report. This Open Fiscal Data System is connected to 44 administrative institutions and 63 other external organization information systems, and has the Fiscal Information Disclosure function which monitors government budgeting and financing in a real-time. These data are displayed in visible forms such as mobile graphs and tree maps to aid public understanding. The dBrain system has seen a great deal of positive effects in boosting transparency, budget efficiency and civil participation, while reducing corruption. As a result, public trust in government has improved, and citizens’ checks on government budget spending have contributed to combatting waste.

In 2004, the Korean government established the Five-year Plan for Public Information Distribution Support Projects, and has continued its efforts to promote e-government and open government data (OGD) ever since. In 2013 the government announced Government 3.0 – making government data available to the public to re-use as a raw material for creative and innovative economic activities.

The main objectives were to improve efficiency in public services and government transparency; to promote inclusive citizen engagement; and eventually to boost economic growth. The 2013 Act on Provision and Active Use of Public Data obliged the government and public organisations to launch OGD programmes to make their machine-readable data available to the public. In January 2016, the Public Data Provision and Use Revitalisation Act was established to provide a legal basis for public openness and information use.

As a result, a wide range of public data – such as on history, culture, arts, education, public policy, statistics, law, land management, weather and disaster prevention – are available via a public data portal (www.data.go.kr). The Open Data Portal provides more than 17,000 datasets disclosed by the government for free use by people for their convenience and to create added-value activities such as the Night Owl Bus in Seoul and more.

Establishing the Open Data Portal has been shown to generate benefits both for government and citizens. As the volume of open data provided by the portal increased from 5,272 datasets in 2013 to 17,064 datasets in 2015, its use by the public increased over 100 times from 13,923 types of data to 1,401,929 datasets within the same period. The Korean government has not only reduced budget waste by making its administration more efficient through OGD, but also officially acknowledged how OGD can be a reliable methodology which opens new door for the citizens to bring innovations themselves in the real life.

Values of procedural fairness through communication

The perception of being fairly treated in communication processes is a main source of public trust in government. Public support for the government increases when people feel that procedures are fair. According to the findings of this study, procedural fairness through communication is positively influential on many indicators of trust in government, such as perceptions of responsiveness, reliability, integrity, openness, and fairness.

Therefore, the Korean government should keep working on these communication efforts for all policy decision making and activities. Boxes 6.6, 6.7 and 6.8 give examples of government efforts towards fairness communication.

Gwanghwamoon in central Seoul, is symbolic for Korean democracy; it was the location of a series of protests against corruption under previous president between October 2016 and April 2017. With a strong emphasis on government-citizen communication, the new administration under President Moon Jae-in has initiated a nationwide forum for citizens to share their policy suggestions. Following its inauguration in May 2017, the new administration opened a forum on Gwanghwamoon’s First Avenue to call for citizen participation in policy making over a period of 50 days – inviting all citizens to join the Government Transition Committee. In the venue, citizens could publicly share their ideas from the stage and discuss future government plans. The on-site booth operated from Tuesdays to Sundays, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (and until 8 p.m. on Wednesdays), and the online channels were available 24/7 via text messages, call centres, its website (www.gwanghwamoon1st.go.kr), and emails.

During the lifetime of the project, more than 180,000 policy suggestions were collected and all became seeds for the better future. And there were various types of suggestions like insistence on blind recruitment, raising voice on using more renewable energy, on making fair competition order throughout the whole society including the education system, noise complaint issues from downstairs neighbour in the apartments, and more. At the end of the 50 days, President Moon Jae-in held a broadcasted session to report on the project results. All the suggestions were shared on the website by category and number, and major suggestions reflected in national plans are followed up regularly on the website. The Gwanghwamoon First Avenue website remains an open channel for citizen policy discussions to this day.

Public conflict over nuclear power has caused problems in Korea. The first built nuclear power plant in Korea “Kori 1” operated from 1977 and shut down permanently in 2017. Even the closure of the plant there have been conflicts over the construction of new nuclear power plants, radioactive waste management and building power transmission lines, and other relevant policies have been delayed. This has left Korea with a number of economic and social burdens. The Korea Nuclear Energy Agency is committed to promoting a sustainable energy policy, conflict resolution and social consensus on nuclear energy.

On 7 July 2017, after consulting related ministries, the Office for Government Policy Co-ordination announced the establishment of a public relations committee for Shin-Kori 5 and 6 – the two latest proposed nuclear reactors, which have been a source of great controversy. The Shin-Kori Committee will consist of nine members including the chair, who must be neutral. The committee members will represent each field of the humanities, science and technology, survey and statistics, and conflict management, and must mediate public communications neutrally. Gender balance and youth representation were also taken into consideration in the committee’s composition. The committee selection process will be based on recommendations by eight professional organisations, including those both for and against nuclear power, for the first 24 candidates. In this way, each referee organisation can recommend three candidates who must include one or more woman, while humanities and science and technology organisations have to include one or more candidate between the ages of 20 to 30. The State Co-ordination Office won’t disclose the names of the candidates to protect their privacy and will later publicise the final committee members.

Once formed, the chair and the committee members into public discussion for three months, aiming to manage the process of public debate fairly, create public consensus and promote government-citizen communication. Although the committee does not have the authority to decide on whether to suspend construction of Shingori Units 5 and 6, its main role is to facilitate the opinions of experts and stakeholders, to be properly reflected in the government’s decision.

Citizen participatory budgeting is a system that allows residents to directly participate in the process of budget allocation, traditionally monopolised by local government. The first international experiences date from the late 1980s and it started to influence Korea in the 2000s. A turning point in the movement was in 2011, the government established a legislative system for implementing citizen participatory budgeting. As a result, the Metropolitan City of Seoul has been actively implementing a budget system that allows citizen participation since 2012. This participation by new stakeholders has changed the structure of budgeting authority, procedures and decision-making methods. Participatory budgeting is regarded as a “paradigm shift”, in that it breaks down established budgeting methods and adopts new principles and processes, with the core values and motivation of the new system at their heart.

The Seoul Participatory Budget website (yesan.seoul.go.kr) displays the projects for which residents participated in budgeting by category and geography, as well as educational materials for enhancing budgetary understanding and a forum for suggesting city budget changes. The number of city businesses conducted with citizen participation has increased approximately 20 times, from 223 to 3 979 between 2013 and 2016, and the size of the participatory budget has grown more than tenfold, from USD 503 000 to USD 5 400 million, during the same period. The Participatory Budget Committee, formed to monitor activities and publish system assessments, has helped expand citizen participatory budgeting in Seoul. The city government has also reflected on its outcomes over the last five years and revised the system to help achieve a fairer budgeting system.

Capacity building for risk and crisis communication

The last meaningful finding of the current empirical study is that effective government communication during risk, crisis and/or disaster situations is a key that positively influences the drivers of trust in government, including perceptions of responsiveness, reliability, integrity, openness and fairness. As the main findings suggest, the Korean government puts more effort into communication when a crisis occurs in order to communicate with a number of public audiences. Boxes 6.9 and 6.10 give examples of what the government has done in terms of risk, crisis and disaster communication.

When it comes to national health issues, prevention is at least as important as cure. Although immunisation is key to avoiding preventable diseases such as measles and polio, a lack of public awareness has led to low immunisation rates. The Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention, therefore, carries out immunisation support as one of the government’s major projects, and has received significant investment since 2013. Children under 12 years old are eligible for 15 types of immunisations for free, while the elderly (over 65) are offered two types of immunisation. To facilitate this project, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP) has committed to organising effective health communication for the entire nation. An analysis conducted by the CDCP showed lackadaisical public perceptions, believing that immunisation is a concern for mothers and children, not a societal issue. As mothers’ economic activities increase, it has become more likely that one or two vaccinations for children will not be given on time, and the full immunisation rate was lower for older cohorts. For example, immunisation rates were found to be 93% for 1 year-olds, 80.4% for 3 year-olds, and 60% for 6 year-olds. The results implied a need to focus public attention on immunisation. In turn, in general the elderly also reported comparatively low immunisation rates.

CDCP therefore organised a campaign targeting children under 12 and the elderly over 65 in particular, as well as adults and relevant organisations such as government offices, the media, education and medical centres. In 2015, CDCP implemented a variety of programmes suitable for each target group. For children aged 4-7, they produced musical shows and puppet shows on disease prevention, while creating online and offline communities to communicate with and educate mothers. They also organised various events for adults to promote immunisation for themselves and their families. The media, health communication contests, public advertisements and social media were also used to reach out to the public.

These extensive measures did improve public awareness of immunisation, built communication channels and increased immunisation rates for the elderly by 12%. According to a public survey on policy satisfaction, 93.8% showed satisfaction with the government’s support for influenza vaccinations. Moreover, the immunisation support policy was selected as the best policy in 2015 by the public.

Various financial scams use telecommunications, such as telephone calls, mobile phone text messaging and the Internet. In 2014, phishing scams accounted for KRW 216.6 billion, an increase of 58.6% over the previous year. Criminals increased the damage inflicted by impersonating government agencies such as prosecutors and financial institutions. On the other hand, financial fraud monitoring agencies lacked the means of reaching the public immediately when fraud damage rapidly increased or a new law appeared. In response, the government established a co-operation system with financial fraud monitoring agencies – such as the National Police Agency, the Financial Supervisory Service and the Korea Consumer Agency – to establish an early warning system to prevent financial fraud.

These agencies are responsible for monitoring and analysing financial fraud cases through telecommunication services. The Korea Communications Commission sends warning messages if crucial damage is expected, in collaboration with three major telecommunication companies (LG U-plus, KT and SK Telecom). If an offence is expected to result in widespread damage, the three telecommunications operators send a text message to their 48 million subscribers with instructions and countermeasures from the Korea Communications Commission. The early warning system, according to Government 3.0, is expected to prevent large-scale financial fraud damage with its systematic and pre-emptive countermeasures. The early warning system should thus help effectively address, prevent and avoid financial fraud.

Strengthening government communication: management capacity

This report highlights how government communication strategies affect citizens' trust in public institutions. Government communication policies need to be aligned with governance values and ethics, and establish an ecosystem in the public sector that is conducive to mutual understanding, deliberative discourse and optimal decision making.

When designing and implementing government communication services, public managers should be sensitive to the target citizens’ social and cultural realities as well as the political and economic dimension. Only then can communication services elicit meaningful responses from people and hope to enhance public well-being. The old one-way, top-down bureaucratic communication model no longer applies. Government managers will need to delve into communication strategies that empower citizens to engage in direct interaction over policy issues.

Moreover, government communication managers should exploit communication strategies that can turn government vision into reality. Government needs to remain committed to improvement, measuring the impact of communication strategies objectively, in order to reform organisations with a focus on greater openness, engagement and social capital.

Lastly, given the socioeconomic impact of digital and social media in public management, government communication should invest in digitalisation to maintain a seamless relationship with tech-savvy citizens. Given that mobile and social media use is a common denominator among young adults, government communication managers should use these more agile and adaptive communication approaches. This can facilitate a two-way, symmetrical exchange of information on government policy, decisions and actions, especially with groups of people who have higher levels of digital and media literacy than government capacity and expertise.

Public sector colleagues who do not work in communication can devalue the role of communication in the sector. Indeed, intergovernmental relations and cross-department communication within and between government organisations can influence or alter policy of governments and hold government officers accountable to raise public awareness and inform the public about current activities. Moreover, quality communication service for government organizations and practitioners can strengthen the position of governments over parliaments and increase access information and necessities for engagement and cooperation bilaterally. Nonetheless, inadequate budget and highly skilled roles have been a key problem for government communication activities than can rapidly adapt to fundamental changes in demographics, social values, media and technology compared to private sector communication.

Building communication capacity: governance approach

Government should become more interdependent with policy actors and stakeholders to achieve their goals. The findings in this chapter show that the following factors matter in more effective government communication: democratic governance values; commitment by government leaders to build a horizontal relationship with its citizens; using the right channels; clear ground rules; resource capacity; and principles of transparency and fairness. Our study therefore opens up a myriad of recommendations for government communication managers in the following:

-

Communicate and inform the public of the mission, values, and roles of the government organisation and its policies that benefit external stakeholders.

-

Facilitate the flow of information within a government organisation or project, to enhance synergistic, efficient operation and to avoid duplication.

-

Raise awareness of “hot” public issues and employ relevant communication and media strategies in order to support changes in perceptions, attitudes, and behaviour of the targeted population and the wider public.

-

Inform, support and reassure the public in times of risk, crisis, and disaster so that both society and government reputation can stay resilient.

-

Create environments for sustainable change in society and the public sector, by engaging stakeholders through horizontal communication that meets legal requirements (of integrity, honesty, objectivity and so on) when making decisions that affect their lives.

-

Develop an integrated government communication model and performance measurement framework across communication strategies, including citizen participation, in order to measure and maximise the impact of government communications.

-

Government should be confident and knowledgeable about using digital technology – such as the internet of things, mobile technology, big data, artificial intelligence, and the cloud – in order to gain citizen insights into policy making, develop media strategies for implementing policies, and bring about maximum communication impacts.

Aligning government communication goals with good governance values should be high on the agenda to enhance public trust in government institutions in Korea , by making a commitment to the value of openness, government agencies could make communication patterns flexible – such as providing budget information online at the time of policy implementation. This kind of online information-sharing system could also provide excellent opportunities for designing two-way communication mechanisms and customised, easy-to-understand budget information for various population groups. A stronger commitment to implementing the Freedom of Information Act should be considered as well, as a way of enhancing the public’s assessment of government communication effectiveness.

Accountability should be a foundational value for government communication. Effective ways to demonstrate this value include proactively sharing government data, online and offline; analysing agency performance; policy evaluations; and programme monitoring information. Also, getting feedback from diverse citizens could facilitate citizens’ assessment of government communication effectiveness.

Delivering on the value of accountability in government communication demands co-ordination. The prime minister’s office could pay closer attention to co-ordinating and sharing policy performance data among national government agencies, and between national and sub-national government agencies, in order to better target information for citizens by policy area. For example, Statistics Korea could expand its collaboration efforts with government agencies for speedy policy performance data sharing, such as on regional variations in small business start-ups, labour markets, and quality of life and well-being indicators for diverse groups of citizens. Strengthening the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission’s capacity for participatory governance is important to allow proactive two-way communication with citizens on the performance of anti-corruption policies and public dispute resolution.

Commitment to participatory governance should be a priority to improve government communication with citizens, addressing citizen as experts and partners in solving community concerns, including emergency and crisis management and public dispute resolution. With this in view, government agencies should strengthen participatory governance by adopting horizontal and diversified two-way communication tools, of both online and offline, customised for specific groups of citizens. Through participatory governance, civil servants and citizens can engage in authentic communication and deliberative decision-making processes.

In order to deliver participatory governance, government should consider expanding citizen engagement programmes to give people more opportunity to participate in the agenda-setting stage of the policy process. The Korean government’s advanced e-government systems could be used to design participation in setting agendas by opening the process to the public. Online policy forums to set the agenda of a specific policy area could allow more citizens to gain access to policy issues, provide input and observe how those issues are shaped by citizens’ input. However, considering that the digital divide may limit some groups’ participation, proactive offline programmes should be developed reaching out to younger generations, low-income families and rural communities. Special attention should be paid to government capacity for responsiveness in managing the participation programme, with quality feedback and proactive two-way communication between public managers and citizen participants in agenda setting.

Government should prioritise proactive, authentic and co-ordinated communication with people in their 20s and 30s, especially for government agencies delivering policies directly relevant to their interests. Government leadership should consider creative forms of offline and online communication with younger people to promote understanding of their culture, as well as to promote understanding between generations. To improve young people’s assessment of government communication effectiveness, government agencies should experiment with various engagement opportunities, from consultation to participatory decision making.

Finally, communication training programmes for civil servants could be redesigned to meet the increasing need for engagement and creative problem solving in a complex era for governance and policy setting. Redesigned training programmes could include a simulation approach for dealing with the media, public communication, listening, persuasion, negotiation, dispute resolution and facilitation.

To reiterate, this chapter goes beyond a narrow definition of government communication as a process of informing relevant stakeholders and communities about public policy decisions. Instead, it defines government communication as being systematic and two-way between government agencies and citizens throughout the public policy process, from agenda setting, decision making, policy implementation to monitoring and feedback. It concludes that government communication is an important mechanism for building relationship between government agencies and citizens in various communities.

References

Avery, E. J. et al. (2010), “A quantitative review of crisis communication research in public relations from 1991 to 2009”, Public Relations Review, Vol. 36/2, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 190-192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.01.001.

Ayres, I. and J. Braithwaite (1992), Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate, Oxford University Press, New York.

Bakir, V. (2006), “Policy agenda setting and risk communication: Greenpeace, Shell, and issues of trust”, Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, Vol. 11/3, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 67-88, https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X06289213.

Bartels, K. P. (2014), “Communicative capacity: The added value of public encounters for participatory democracy”, The American Review of Public Administration, Vol. 44/6, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 656-674, https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074013478152.

Bingham, L. B., T. Nabatchi and R. O'Leary (2005), “The new governance: Practices and processes for stakeholder and citizen participation in the work of government”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 65/5, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 547-558, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00482.x.

Bouckaert, G. and S. Van de Walle (2003), “Comparing measures of citizen trust and user satisfaction as indicators of ‘good governance’: Difficulties in linking trust and satisfaction indicators”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 69/3, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 329-343, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0020852303693003.

Carpenter, D. P. and G. A. Krause (2012), “Reputation and public administration", Public Administration Review, Vol. 72/1, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 26-32, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02506.x.

Choi, Y.-S. and M. Han (2014), “The effects of government’s conflict management strategy on public communication behaviors and policy acceptance”, The Korean Journal of Advertising, Vol. 25/1, pp. 91-125. https://doi.org/10.14377/KJA.2014.01.15.9

Chung, W. J. (2017), “A study of policy acceptance: Based on the case of the Korea-China free trade agreement (FTA)”, The Korean Journal of Advertising and Public Relations, Vol. 19/3, pp. 99-135. https://doi.org/ 10.16914/kjapr.2017.19.3.99

Chung, W. J. (2016), “The effects of government crisis communication strategies on the level of trust in government and the communication intention among the public buffering effects of authenticity in the case of the Sewol ferry tragedy”, The Korean Journal of Advertising and Public Relations, Vol. 18/3, pp. 32-57. https://doi.org/ 10.16914/kjapr.2017.19.3.99

Cleary, M. R. and S. C. Carol (2006), Democracy and the Culture of Skepticism: Political Trust in Argentina and Mexico, Russell Sage Foundation Publications, New York.

Froehlich, R. and B. Rüdiger (2006), “Framing political public relations: Measuring success of political communication strategies in Germany”, Public Relations Review, Vol. 32/1, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 18-25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2005.10.003.

Gelders, D., G. Bouckaert and B. van Ruler (2007), “Communication management in the public sector: consequences for public communication about policy intentions”, Government Information Quarterly, Vol. 24/2, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 326-337, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2006.06.009.

Gelders, D. and Ø. Ihlen (2010), “Government communication about potential policies: Public relations, propaganda or both?” Public Relations Review, Vol. 36/1, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 59-62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.08.012.

Gilad, S., M. Maor and P. B.-N. Bloom (2015), “Organizational reputation, the content of public allegations, and regulatory communication”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol. 25/2, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 451-478, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut041.

Grimmelikhuijsen, S. et al. (2014), “Organizational arrangements for targeted transparency”, Information Polity, Vol. 19/1, IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp. 115-127, https://content.iospress.com/articles/information-polity/ip000325.

Grimmelikhijsen, S. et al. (2013), “The Effect of Tranparency on Trust in Government: A Cross-National Comparative Experiment”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 73/4, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 575-586, https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12047.

Grimmelikjuijsen, S. G. (2012), “Linking transparency, knowledge and citizen trust in government: An experiment”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 78/1, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 50-73, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852311429667.

Grimmelikhuijsen, S. and E. Welch (2012), “Developing and testing a theoretical framework for computer-mediated transparency of local government”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 72/4, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 562-571, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02532.x.

Grunig, J. E. and L. A. Grunig (2006), “Characteristics of excellent communication”, in T. L. Gillis (ed.), The IABC Handbook of Organizational Comunication: A Guide to International Communication, Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco.

Grunig, L. A., J. Grunig and D. Dozier (2002), Excellent Public Relations and Effective Organizations: A Study of Communication Management in Three Countries, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Grunig., J. and T. Hunt (1984), Managing Public Relations, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York.

Grunig, J. E. and H. Todd (1984), Managing Public Relations, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York.

Heald, D. (2012), “Why is transparency about public expenditure so elusive? International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 78/1, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 30-49, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852311429931.

Hetherington, M. J. (1999), “The effect of political trust on the presidential vote, 1968-96”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 93/2, APSA, Washington DC, pp. 311–26, www.jstor.org/stable/2585398.

Hong, H. et al. (2012), “Public segmentation and government–public relationship building: A cluster analysis of publics in the United States and 19 European countries”, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 24/1, Taylor and Francis, Abingdon, UK, pp. 37-68, https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2012.626135.

Hwang, S., B. Moon and J. Lee (2014), “Developing the public dialogue evaluation model for local governments based on the AHP (analytic hierarchy process) method”, Korean Journal of Journalism and Communication Studies, Vol. 58/5, pp. 255-284. https://www.comm.or.kr/English/About/Mission

Jaques, T. (2009), “Issue and crisis management: Quicksand in the definitional landscape”, Public Relations Review, Vol. 35/3, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 280-286, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.03.003.

Jaques, T. (2007), “Issue management and crisis management: An integrated, non-linear, relational construct”, Public Relations Review, Vol. 33/2, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 147-157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2007.02.001.

Karippacheril, T. G. et al. (2016), Bringing Government into the 21st Century: The Korean Digital Governance Experience, World Bank, Washington DC, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/24579.

Kent, M. L., M. Taylor and W. J. White (2003), “The relationship between web site design and organizational responsiveness to stakeholders”, Public Relations Review, Vol. 29/1, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 63-77, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00194-7.

Kettle, D. F. (2000), “The transformation of governance: Globalization, devolution, and the role of government”. Public Administration Review, Vol. 60/6, ASPA, Washington DC, pp. 488-497, https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00112.

Kim, G.-R. and M.-J. Moon (2008), “Reactions and effects on public policy PR according to public characteristics: Focusing on types of information and information preference”, The Korea Public Administration Journal, Vol. 17/2, pp. 33-57. https://www.kipa.re.kr/site/eng/main.do

Kim, H., J. Y. Jeong and N. Park (2015), “The perception gap of PR officers between their capacity evaluation and necessity for education: On the five major areas of PR”, Journal of Public Relations, Vol. 19/1, pp. 61-84. http://www.kaspr.net/index.asp

Kim, L.-S. (2017), “An exploratory study of factors determining communication between local council and citizens: Focusing on citizens’ perceptions”, Journal of Korean Association for Local Government and Administration Studies, Vol. 31/2, pp. 199-218. http://www.kalgas.or.kr/

Kim, S. (2010), “Public trust in government in Japan and South Korea: Does the rise of critical citizens matter?” Public Administration Review, Vol. 70/5, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 801-810, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02207.x.

Kim, S. and J. Lee (2012), “E‐participation, transparency, and trust in local government”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 72/6, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 819-828, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02593.x.

Kim, Y.-K., Y.-J. Cheong and Y. Kim (2014), “A scale development study for evaluating public institutions: Focusing on citizens’ perceptions of institution image, organization-public relationship and administrative service,” Korean Journal of Journalism and Communication Studies, Vol. 58/4, pp. 70-95. https://www.comm.or.kr/English/About/Mission

Kim, Y. K., Moon B. (2010). “A study of developing and validating public campaign brand equity scale”, The Korean Journal of Advertising, Vol. 29(5)

Kim, U., Helgensen G and B. Mang Ahn (2002), “Democracy, Trust and Political Efficacy: Comparative analysis of Danish and Korean Political Culture”, Applied Psychology: An International Review”, Oxford, 51(2), pp 318-353

Knack, S. (2002), “Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the States”, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 46/4, MPSA, Bloomington, IN, pp. 772-85, www.jstor.org/stable/3088433.

Laing, A. (2003), “Marketing in the public sector: Towards a typology of public services”, Marketing Theory, Vol. 3/4, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 427-445, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593103042005.

Laursen, B. and C. Valentini (2015), “Mediatization and government communication”, The International Journal of Press/Politics, Vol. 20/1, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 26-44, https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214556513.

Lee, H. O. and Y. Choi (2014), “Beyond the situational crisis communication theory: Where to go from now on? Journal of Public Relations, Vol. 18/1, pp. 444-475. http://www.kaspr.net/index.asp

Lee, T. (2017), “Antecedents and consequences of government officers' micro-boundary spanning behaviors: A government communication perspective”, The Korean Journal of Advertising and Public Relations, Vol. 19/1, pp. 5-37.

Lee, T. (2016), “Persuasiveness of information disclosure in financial services advertising and regulatory expectations for financial consumer protection,” The Korean Journal of Advertising and Public Relations, Vol. 18/1, pp. 112-139.

Lee and Chung. (2016), “An Empirical Assessment of the Influence of Transparency and Trust in Government on Lay Citizens’ Communicative Actions Relative to Conflict of Interest in the Public Servic,” The Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 20 No.3, pp. 84-112.

Lee, T., T. Yun and E. Haley (2017), “What you think you know: The effects of prior financial education and readability on financial disclosure processing”, Journal of Behavioral Finance, Vol. 18/2, Taylor and Francis, Abingdon, UK, pp. 125-142, https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2017.1276064.

Lee, T. and B. J. Kim (2015), An empirical analysis of the applicability of social big data analytics to public policy communication planning, Journal of Public Relations, Vol. 19/1, pp. 355-384. http://www.kaspr.net/index.asp

Liu, B. F. et al. (2010), “Government and corporate communication practices: Do the differences matter?” Journal of Applied Communication Research, Vol. 38/2, Taylor and Francis, Abingdon, UK, pp. 189-213, https://doi.org/10.1080/00909881003639528.

Liu, B. F. and J. S. Horsley (2007), “The government communication decision wheel: Toward a public relations model for the public sector”, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 19/4, Taylor and Francis, Abingdon, UK, pp. 377-393, https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260701402473.

Meijer, A. (2013), “Understanding the complex dynamics of transparency”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 73/3, Francis and Taylor , Abingdon, UK, pp. 429-439, https://doi.org/10.1080/00909881003639528.

Meijer, A. J., D. Curtin and M. Hillebrandt (2012), “Open government: Connecting vision and voice”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 78/1, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 10-29, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852311429533.

Moon, B. B. and G. Park (2014), “The differential roles of trust and distrust in conflict management of Korean Government”, Journal of Public Relations, Vol. 18/3, pp. 216-240. http://www.kaspr.net/index.asp

Moynihan, D. P. and J. Soss (2014), “Policy feedback and the politics of administration”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 74/3, Francis and Taylor , Abingdon, UK, pp. 320-332, https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12200.

Ni, L. and Q. Wang (2011), “Anxiety and uncertainty management in an intercultural setting: The impact on organization–public relationships”, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 23/3, Taylor and Francis, Abingdon, UK, pp. 269-301, https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2011.582205.

OECD (2017), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en.

OECD (2009), Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/20774036.

O'Leary, R. and L. B. Bingham (2008), The Collaborative Public Manager, Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC.

Piotrowski, S. and G. G. van Ryzn (2007), “Citizen attitudes toward transparency in local government”, The American Review of Public Administration, Vol. 37/3, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 306-323, https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074006296777.

Renn, O., T. Webler and P. M. Wiedemann (eds.) (1995), Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse, Vol. 10, Springer Science and Business Media, Berlin.

Reynaers, A. and S. Grimmelikhuijsen (2015), “Transparency in public-private partnerships: Not so bad after all?” Public Administration, Vol. 93/3, ASPA, Washington, DC, pp. 609-626, https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12142.