Chapter 4. Priority challenges in adult learning requiring co-operation

In Slovenia, as in other OECD countries, two complex challenges facing the adult-learning system are: motivating more adults to learn and appropriately funding adult learning effectively and efficiently. Having strengthened the “enabling conditions” for co-operation (Chapter 2) and improved co-operation between specific actors (Chapter 3), Slovenia should take a more co-ordinated approach to addressing these two challenges as a priority. This chapter presents each of these priority areas in turn with 1) an overview of the current arrangements, roles and responsibilities; 2) a discussion of the opportunities for improvement; 3) examples of good practice from Slovenia and abroad; and 4) recommended actions to better address these two challenges, in order to boost adults’ learning and skills.

Improve co-operation on raising awareness about adult learning

Motivating more adults to learn and employers to invest in training will be essential for achieving Slovenia’s goal of raising participation in adult learning. This requires government, social partners and other stakeholders to effectively promote and raise awareness of the benefits of and opportunities for adult learning.

About half of Slovenia’s adults (48%) do not participate and do not want to participate in education and training (Eurostat, 2018[1]). Slovenia has been unsuccessful in reducing this figure over the last decade, which stood at 46% in 2007. Motivation to learn is lowest among low-skilled adults. In Slovenia, 57% of adults with low proficiency in numeracy or literacy do not participate, and do not want to participate in education and training (OECD, 2017[2]).

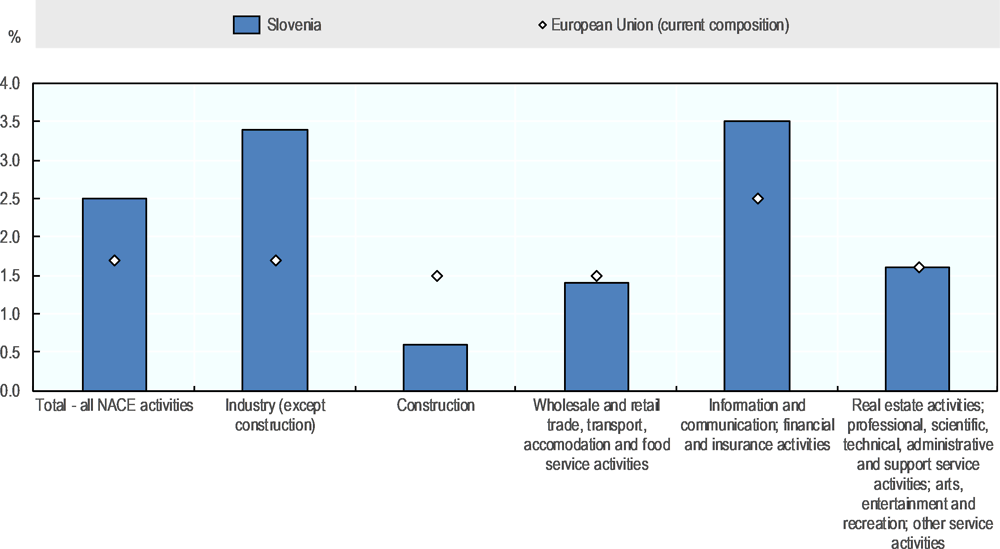

A relatively large share of enterprises in Slovenia provide financial support for continuing vocational training (CVT) for their workers, although the share is much smaller for certain groups. Only about 16% of enterprises in Slovenia1 provide no such support, below the EU average of 27% (Eurostat, 2018[3]). However, for small enterprises (10-49 employees) the rate is much higher at 32% (Eurostat, 2018[3]). In addition, support for CVT is relatively low in some sectors like construction, and trade, accommodation and transport (Figure 4.3).

OECD countries employ several approaches to promote adult learning among individuals and enterprises (OECD, 2005[4]), including ensuring policy co-ordination and coherence (see Actions 1–5), improving delivery and quality control (related to Actions 3 and 6), and promoting well-designed co-financing arrangements (see Action 8). In particular, promoting and improving the benefits of adult learning is important (OECD, 2005[4]). This requires providing high-quality information about the potential benefits of adult learning and the learning opportunities available to adults (see Action 3). It also requires the effective dissemination of this information on line, through outreach by various actors, guidance services and broader awareness campaigns.

Current arrangements for raising awareness about adult learning

In Slovenia, public agencies and providers seek to promote and raise awareness of adult learning in various ways, as do some social partners.

The Adult Education Master Plan (Resolucija o nacionalnem programu izobraževanja odraslih v Republiki Sloveniji za obdobje) (ReNPIO) established information provision, counselling and the promotion of adult learning as priority activities for 2013-20. These activities seek to (re)integrate adults into education, especially young and disadvantaged adults. To this end, the ReNPIO suggests free information and counselling activities, new counselling models and programmes, and improved career guidance in adult learning. It also recognises the importance of co-operation between professionals and organisations from different sectors, including social partners, for realising its priorities.

Since 1996, Slovenia’s Lifelong Learning Week has involved representatives of all sectors to promote the value of and opportunities for adult learning on a national scale (Box 4.1).

Since 1996 Slovenia’s Lifelong Learning Week has helped foster a culture of lifelong learning in the country. It promotes learning opportunities in various programmes and providers, guidance services, and social and cultural events at the national and local level.

The week commences with a grand opening and the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education’s (Andragoški center Republike Slovenije) (ACS) annual adult-learning awards, and involves an adult-learning conference, Learning Parades in selected towns, and a range of other events. The slogan of the campaign is “Slovenia, learning society” (Slovenija, učeča se dežela). The campaign seeks to build positive attitudes towards learning and education, and awareness of adult learning’s importance and pervasiveness.

Several actors are involved in Lifelong Learning Week, including:

-

The ACS provides the overall co-ordination of the project at the national level.

-

Regional and thematic co-ordinators – institutions such as Adult Education Centres (Ljudske univerze) (LUs) – act as initiators, directors and co-ordinators. They either work together in their own region or on a specific content area nationwide. For example, in 2018 there were 43 such regional co-ordinators and 16 thematic co-ordinators.

-

The event providers are organisations from various fields:

- formal and non-formal education (kindergartens, primary and secondary schools, LUs, Universities of the Third Age, study and reading circles) (Študijski in bralni krožki), counselling centres, self-study centres (Središča za samostojno učenje)

- work (businesses, Employment Service offices, trade unions)

- culture (cultural centres, libraries, museums, music and dance schools, cultural associations)

- social organisations (centres for social work, homes for the elderly, social associations)

- other institutions and associations in the fields of ecology, health, tourism, sport, youth organisations, etc.

The Ministry of Education, Science and Sport (Ministrstvo za izobraževanje, znanost in šport) (MIZŠ) and Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities (Ministrstvo za delo, družino, socialne zadeve in enake možnosti) (MDDSZ) are the main sponsors of Lifelong Learning Week and offer financial and other support for its implementation. A national committee is appointed for four years to steer and monitor Lifelong Learning Week at the strategic level, and consists of representatives of three ministries (MIZŠ, MDDSZ and Ministry of Culture [Ministrstvo za kulturo] [MK]), the ACS, providers, trade unions and chambers of commerce.

Source: ACS (2018[5]), LLW – Slovenian Lifelong Learning Week, https://llw.acs.si/about/.

Lifelong Learning Week has expanded significantly in last two decades in terms of providers, events, publications and visitors (Table 4.1).

The ACS seeks to motivate adults to learn by publicly recognising success stories through its annual awards for adult learning (Priznanja za promocijo učenja in znanja odraslih) (ACS Awards). There are three categories of ACS Awards: individuals; groups; and institutions, businesses or local communities. Awards are given based on various criteria, including extent of personal development, achievements after learning, extent of obstacles overcome, knowledge sharing and contribution to the wider environment. The ACS awards up to ten recipients each year in a public ceremony typically coinciding with the opening of Lifelong Learning Week.

The ACS has developed training and performance indicators to help providers effectively promote their adult-learning programmes. Promotion and Marketing in the Field of Adult Education (Promocija in trženje na področju izobraževanja odraslih) is an 8-hour training programme covering basic marketing approaches in adult learning. Approximately 39 practitioners enrolled in the training in 2018. The ACS’ self-evaluation framework for adult education, POKI (Box 2.10 in Chapter 2), includes quality indicators for general and targeted promotional activities in adult learning. Data on the number of education and training providers using these indicators are not available.

Individual education institutions raise awareness and reach out to prospective learners about their programmes in different ways and to differing degrees. A study involving interviews with seven providers of adult education and training in Slovenia found that none had developed specific outreach activities for under-represented learners, such as unemployed or Roma adults (Ivančič, Špolar and Radovan, 2010[7]). The study found that upper secondary and higher education providers focused their outreach and promotional activities on adults who are willing and able to pay for learning. The LUs took a more proactive and widespread approach to outreach, directly mailing households; advertising on line, in papers and on posters; contacting the human resources departments of employers; and presenting to employers. To reach under-represented groups, LUs liaised with social workers, Universities of the Third Age, local societies, associations, clubs and the Employment Office, and met face-to-face with members of the Roma community. Some LUs, such as the LU in Jesenice, have employed someone from the local migrant community to reach out and promote learning opportunities. Finally, Inter-Company Training Centres (Medpodjetniški izobraževalni centri) (MICs) can play a role in raising the awareness of companies and adults about sector-specific training opportunities.

Slovenia has a well-developed and expanding network of professional guidance counsellors, who play an important role in promoting adult learning. Professional counsellors in Slovenia’s 17 Regional Guidance Centres can help adults identify their learning needs, find relevant programmes and financial support, persist with their programmes, and plan their careers. They focus on assisting adults with low levels of skills, those aged over 50, migrants and Roma. In 2017, approximately 13 400 adults attended individual guidance counselling sessions in Slovenia. With the 2018 Adult Education Act (Zakon o izobraževanju odraslih) (ZIO-1 Act) establishing educational guidance counselling as a public service, the number of regional guidance centres will increase to 34, and public expenditure will increase to EUR 2 million per year. Similarly, career counsellors in the Employment Service of Slovenia’s (Zavod Republike Slovenije za zaposlovanje) (ZRSZ) 12 regional Career Centres provide unemployed and at-risk adults with information and guidance on potential career paths and training opportunities. In 2017, about 20 300 individuals attended meetings with the ZRSZ’s career counsellors.

The Expert Group for Lifelong Career Guidance provides a forum for various actors to co-ordinate Slovenia’s career guidance services. Established in 2008 by the MIZŠ, the group comprises representatives of the University of Ljubljana, the MDDSZ, MIZŠ, ACS, Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Vocational Education and Training (Center Republike Slovenije za poklicno izobraževanje) (CPI), ZRSZ and the Euroguidance Centre of Slovenia. The expert group’s role is to co-ordinate policies and projects; monitor the implementation of training; provide reports, proposals and advice to policy makers; design a draft national strategy; and oversee the quality systems and annual reporting of members (Hergan et al., 2016[8]).

The Centres for Social Work (Centri za socialno delo) (CSDs) also have an important role in promoting adult learning to the long-term unemployed and adults who are not active in the labour market. In co-ordination with the ZRSZ, professional social activators in Slovenia’s 14 regional CSDs identify inactive adults to participate in short-term (3.5 month) or long-term (11 month) education programmes. The purpose of these programmes is to improve the motivation, social and functional skills of disengaged adults, and support them re-entering the labour market. The project aims to work with 3 000 individuals per year.

As noted in Chapter 2 (Action 3), Slovenia has several online portals that offer adults information on available adult-learning programmes. These include the ACS’ portal Where to Obtain Knowledge? (Kam po znanje?), the ZRSZ’s portals Where and How? (Kam in kako?), e-Advisor (s-Svetovalec), and the CPI’s portal My Choice (Moja izbira).

Schools can also play a role in promoting adult learning by referring parents with low levels of skills to education programmes. We Read and Write Together (Beremo in pišemo skupaj) is a family literacy programme for parents with low levels of basic skills. It seeks to improve parents’ literacy and basic skills in order to refine their social skills, develop a family reading culture, provide motivation for lifelong learning and encourage active citizenship. Teachers can refer parents to LUs to access the programmes. In 2011-13, approximately 1 200 participants enrolled in this programme.

Some social partners explicitly set goals to promote adult learning among their members. For example, the Posavje regional chamber of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia (Gospodarska zbornica Slovenije) (GZS) stipulates awareness raising of training opportunities as one of their main services. At the national level, both the GZS and Chamber of Craft and Small Business of Slovenia (Obrtna zbornica Slovenije) (OZS) provide some training programmes for their members, but do not mention promotion or awareness raising among their functions. The Association of Free Trade Unions of Slovenia (Zveza svobodnih sindikatov Slovenije) (ZSSS) includes the promotion of adult education among its objectives. It seeks to motivate its members to learn by seeking appropriate conditions and recognition for their education, and raising awareness among employers about the benefits of training and among union members about opportunities for formal and non-formal education. On the other hand, the Confederation of Trade Unions 90 (Konfederacija sindikatov 90) does not mention education or training among its priority tasks.

The EU recognises promotion and raising awareness of adult learning as a priority, and has developed associated guidance and tools. The Council Resolution on a Renewed European Agenda for Adult Learning (2011[9]) called upon states to foster greater awareness among adults, employers and social partners of the benefits of adult learning, and make full use of the lifelong learning tools agreed at EU level. The European Commission (EC) has developed various tools to assist member states in promoting adult learning, including a network of national co-ordinators who promote adult learning in their countries, as well as the European Guide on Strategies for Improving Participation in and Awareness of Adult Learning (2012[10]). The objectives of the guide are to 1) show how to make adult learning more popular and more accessible for identified target groups; 2) analyse existing initiatives already carried out in terms of awareness raising in the field of adult education; and 3) provide recommendations for future activities and propose which existing strategies should be used.

Opportunities to improve co-operation on awareness raising

Slovenia has a relatively well-developed system for raising awareness about adult-learning opportunities and benefits. The Lifelong Learning Week has been internationally recognised as a good practice, and the ZIO-1 Act expanded publicly funded guidance and counselling services for potential adult learners.

However, several participants in this project reported that awareness-raising efforts for adult learning currently lack widespread cross-sectoral support. The ACS, MIZŠ and MDDSZ services (guidance counsellors, LUs and ZRSZ offices) largely drive these efforts. Participants agreed that all sectors should share responsibility for promoting and raising awareness of adult learning and do more to co-ordinate their efforts.

There is a particular need to raise awareness of the benefits of learning among unemployed and inactive adults in Slovenia, as well as small enterprises. The gap in participation between employed and unemployed or inactive adults in Slovenia widened between 2007 and 2016 (Figure 1.3 in Chapter 1). A relatively high share of the CVT sponsored by small enterprises (41%) consists of “obligatory courses on health and safety at work” (Eurostat, 2018[3]). It is important that such training meets the learning needs of adults and the skills needs of enterprises.

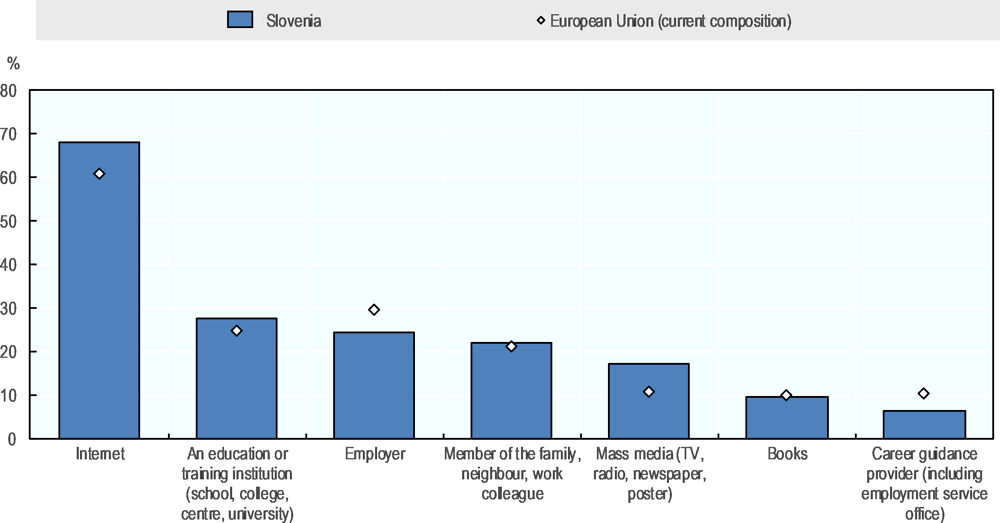

Data from the EC’s Adult Education Survey support the notion that various actors and media have a role in raising awareness about adult learning in Slovenia. In 2016, about 56% of adults in Slovenia reported that they had searched for information on formal and non-formal education and training opportunities. This was higher than all EU countries except Luxembourg and Denmark (Eurostat, 2018[1]). According to the latest data (2011), Slovenian adults draw on a wide range of sources for information on adult-learning opportunities (Figure 4.1).

There are opportunities for several actors and sources to play a more effective role in raising awareness and motivating adults to learn in Slovenia.

Online portals

Improving Slovenia’s online portals for adult-learning opportunities will be essential to raise awareness of adult-learning. The Internet is by far the most commonly used source of information on learning opportunities, and is used more frequently in Slovenia than in other EU countries (Figure 4.1). It is essential that Slovenia’s online portals for adult learning are user friendly and comprehensive, and are integrated with information on the benefits of adult learning and skills needs. Collaboration between the ACS, ZRSZ and CPI will be important in this regard (see Action 3).

Education and training providers

Adult education and training providers in Slovenia have an important role in promoting adult learning, but some providers are lagging behind. In Slovenia, providers are the second-most common source of information on learning opportunities for adults (Figure 4.1). Despite the priority given to under-represented learners in the ReNPIO, most providers do not appear to have specific strategies for promoting learning among these groups. In particular, formal education institutions (upper secondary and tertiary) have limited incentives to reach out to vulnerable groups, as tuition fees would preclude many adults from participating (OECD, 2017[11]). Only 39 practitioners enrolled in the ACS’ Promotion and Marketing in Adult Learning training programme in 2018. Furthermore, good practices like employing representatives of target groups to undertake outreach (as occurs in the LU of Jesenice) are not widespread (Ivančič, Špolar and Radovan, 2010[7]).

Guidance and career counsellors

Guidance counsellors can now play a stronger role in raising awareness of adult learning in Slovenia. Counsellors in LUs are well placed to reach local disadvantaged groups, while the ZRSZ’s counsellors and the CSDs’ case workers are well placed to reach unemployed and inactive adults respectively. According to the 2011 data, Slovenian adults rarely used career guidance providers (including Employment Service offices) for information on learning opportunities (Figure 4.1). The expansion of guidance counselling services under the ZIO-1 Act (2018) is an opportunity for counsellors to play a more prominent role in motivating adults to learn. More comprehensive information on the availability and quality of learning opportunities (Action 3) will support guidance counsellors. It will be important that guidance counsellors promote not only the programmes of their LUs, as LUs accounted for only 6% of providers and 9% of participants in adult learning in Slovenia in 2014/2015 (Taštanoska, 2017[12]). The efficacy of guidance services should be evaluated and monitored over time (Action 3).

Employers

A growing share of enterprises in Slovenia sponsor CVT for workers, but employers could play a greater role still in motivating adults to learn. Smaller enterprises and certain sectors (construction, and trade, accommodation and transport) offer relatively less support for CVT. Employers could also play a greater role in informing workers about relevant learning opportunities. In Slovenia, 25% of adults looking for information on learning possibilities consulted their employer, compared to 47% in France, 41% in the UK and 37% in Denmark (Eurostat, 2018[1]). In the past, the ACS had plans to develop guidance services in the workplace in collaboration with employers, trade union representatives, training managers and human resource managers in small and medium-sized enterprises (Ivančič, Špolar and Radovan, 2010[7]). This has occurred to some extent through specific programmes. For instance, the Competence Centres for Human Resources Development (Kompetenčni centri za razvoj kadrov) (KOCs) of the Public Scholarship Development, Disability and Maintenance Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (Javni štipendijski, razvojni, invalidski in preživninski sklad Republike Slovenije) (JŠRIP), have helped strengthen the HR capacities and training needs assessment of participating employers. More generally, however, it appears that progress on strengthening guidance in workplaces has been limited and is not a clear priority under the ZIO-1 Act.

Social partners

Social partners have a central role in raising awareness of the benefits of learning among employers and employees. A range of international research based on in-depth case studies suggests that working with social partners to plan, promote and recruit adults to learning has improved adults’ skills and employability (European Commission, 2015[13]). In Slovenia, despite declining union and business chamber membership, a relatively high share of employees in Slovenia are covered by collective agreements: 65%, compared to only 33% across the OECD in 2013 (OECD, 2017[14]). However, social partners need to raise the profile of adult education and training among workers and employers, and this should be reflected in collective agreements.

Employers’ associations are well placed to take a lead role in raising employers’ awareness of and motivation for investing in skills (particularly micro and small enterprises). There are five major inter-sectoral employers’ associations in Slovenia (Kanjuo Mrčela, 2018[15]), and several smaller ones. In 2013 in Slovenia, about 60% of employees in the private sector worked in firms affiliated to an employers’ association, above the average for the 26 OECD countries for which data is available (OECD, 2017[14]). However, few associations include promotion of learning among their objectives or services, and some do not actively promote learning. Research into vocational education and training (VET) promotion in Slovenia (Hergan et al., 2016[8]; ReferNet Slovenia, 2011[16]) found that the OZS is quite active in sharing information on apprenticeships and learning opportunities, and promoting craft occupations and job prospects. On the other hand, the research found that the GZS only occasionally undertakes VET promotion activities and is not very active in providing guidance.

Trade unions are well placed to take a lead role in raising awareness and motivation for adult learning among workers, especially low-skilled workers. Slovenia has 49 trade unions, associations or confederations (MDDSZ, 2018[17]). About 21% of employees were members of a union in 2013, above the OECD average of 17% (OECD, 2017[14]). However, while some trade unions, such as ZSSS, have explicit objectives to motivate workers and employers to engage in training, others do not (PERGAM, Konfederacija sindikatov 90 etc.). Some representatives of the ministries involved in this project stated that trade unions in Slovenia have not yet embraced their role in promoting education and training. Some trade unions’ are concerned that education and training is not sufficiently recognised in workers’ remuneration and promotion (Ivančič, Špolar and Radovan, 2010[7]).

Mass media

Compared to other EU countries, the mass media are a relatively important source of information about learning possibilities in Slovenia (Figure 4.1). This confirms the potential for raising awareness about the value of adult learning through high-quality and well-co-ordinated media campaigns. In particular, Slovenia’s Radiotelevizija Slovenija Act 2005 defines the role of public media in raising cultural awareness, suggesting an important role for public media in raising awareness about adult learning.

The LLL Strategy of Slovenia (2007) put a high priority on effective promotion and awareness-raising activities in order to realise the ideal of adult learning (Box 4.2).

Lifelong Learning Strategy of Slovenia (2007)

The LLL Strategy included among its 14 strategic objectives to:

-

enhance awareness that learning results in increased self-confidence, creativity, entrepreneurial spirit and knowledge, and skills and qualifications to support active participation in economic and social life, and a better quality of life

-

make all people aware that they are entitled to learning and education

-

promote lifelong learning as a fundamental life value with all public resources and media for communication and advertising.

The LLL Strategy also included, as one of its 10 “strategic cores”, to “offer information and counselling to people who want to learn or who are learning”. It recommended, among other things:

-

adopting a strategy of lifelong counselling, to ensure its implementation for different target groups and workers, and in other counselling services for adults.

-

providing access to information and counselling as equally as possible, to all adults in all environments

-

reaching out to adults in their environment to encourage demand, rather than waiting for adults to come to the service

-

linking and co-ordinating different counselling services and centres at the state and regional levels, to ensure complementarity, efficiency and quality.

The LLL Strategy included promotion among its implementation measures, and recommended stronger support and promotion of lifelong learning in the media, as well as special promotional events and projects including Lifelong Learning Week, panels on lifelong learning, mottos and slogans (e.g. “lifelong learning for everybody”), exhibitions, leaflets, awards and other promotional material.

Source: Jelenc (2007[18]), Lifelong Learning Strategy in Slovenia, www.mss.gov.si/fileadmin/mss.gov.si/pageuploads/podrocje/razvoj_solstva/IU2010/Strategija_VZU.pdf.

Examples of good practice awareness raising for adult learning

In Croatia, the Agency for VET and Adult Education led the development of a Strategic Framework for Promotion of Lifelong Learning, which establishes communication plans and promotional activities targeted to different groups of adults (Box 4.3).

Croatia’s Strategic Framework for Promotion of Lifelong Learning 2017-21 (Strategic Framework) provides analysis of the state of lifelong learning, basic strategic orientation for the promotion of lifelong learning activities, and communication plans which outline promotional activities for specific target groups. Different promotional activities are targeted to:

-

students in formal education

-

existing and potential participants in adult education

-

employers

-

vulnerable social groups

-

education policy decision-makers, and

-

providers of services in adult education.

Analysis undertaken for the Strategic Framework generated several findings of relevance to the design of the promotion strategy, including the characteristics of adult learners, the main barriers to participation, and the most common motivations for participating in adult education.

The Strategic Framework is expected to contribute to the advancement of the annual Lifelong Learning Week. The main priorities for the promotion of lifelong learning in Croatia involve raising awareness of the need for learning throughout life, learning for personal and social development, the benefits of lifelong learning for adjustment to changes in the labour market, the specific needs of students, career advancement and employability, and the significance of non-formal and informal forms of learning.

Source: Cedefop (2018[19]), New framework for promoting lifelong learning and adult education, www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/croatia-new-framework-promoting-lifelong-learning-and-adult-education.

In the United Kingdom, UnionLearn of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) raises awareness of the importance of adult learning and promotes its adult-learning services and funds to affiliated unions and workers (Box 4.4).

In the United Kingdom, trade unions affiliated to the TUC benefit from the services of an institution named UnionLearn. This organisation is the learning and skills branch of the TUC and is in charge of assisting unions in delivering learning opportunities and skill improvement for their members as well as helping unions to become learning organisations. UnionLearn also acts as a broker connecting employers, learners and education providers (typically for literacy, numeracy, vocational, adult learning and other training programmes), and promotes learning agreements with employers.

An important part of UnionLearn’s activities is to raise awareness of the importance of adult learning, and promote its adult-learning services and funds to affiliated unions and workers. It does this in several ways, including through the support of Union Learning Representatives, promotional materials and awareness events. According to the 2016 evaluation report of Union Learning Fund, 52% of people got involved in UnionLearn activities mainly through the support of Union Learning Representatives, 25% through promotional materials and 20% through union-organised awareness events, among other routes.

The employers involved in UnionLearn’s activities have also played an important role in promoting and providing information on adult learning. About 82% of the employers that engaged with unions on learning did it with the purpose of raising awareness of the benefits of learning and/or training.

These actions have reached a diverse group of members and have been particularly successful in engaging older workers and learners from minority ethnic groups.

The union’s learning activities are supported with resources from the Union Learning Fund, created in 1998 under the authority of the Department for Education and Employment. The main objective of the fund is to develop the capacity of trade unions and Union Learning Representatives to work with employers, employees and learning providers to encourage greater take-up of learning in the workplace. Unions can access the Union Learning Fund on an annual basis (through an application process), by focusing their learning activities on priority areas of government’s skills policy.

Source: Stuart et. al. (2016[20]), Evaluation of the Union Learning Fund Rounds 15-16 and Support Role of UnionLearn: Final Report, www.unionlearn.org.uk/2016-evaluation.

Recommended Action 7: Improving co-operation on awareness raising

In light of these current arrangements, challenges and good practices, employers and chambers, trade unions, providers and government agencies could better co-ordinate their efforts to motivate more adults to learn and employers to invest in training.

Action 7

Employers and their associations, trade unions, ministries, LUs, MICs, CSDs, ZRSZ offices, municipalities, schools, public media outlets and others should better share responsibility for raising awareness about the benefits of and opportunities for adult learning.

These actors should co-operate to design, fund and implement an action plan for promoting adult learning in Slovenia. The action plan should motivate more adults to participate in and employers to sponsor education and training, contributing to a culture of lifelong learning in Slovenia. The action plan should involve a national multimedia campaign to raise general awareness, building on the success of Lifelong Learning Week. It should also detail appropriate awareness-raising, guidance and outreach initiatives at the regional and local level. The action plan should allocate responsibility to individual sectors and/or agencies for reaching out to specific target groups of adults closest to them: employers’ associations for smaller enterprises; trade unions for low-skilled workers; the ZRSZ for the registered unemployed; CSDs for inactive adults; municipalities, LUs and Guidance Centres for other local disadvantaged groups; and schools to reach parents with low levels of skills.

This action plan should support the achievement of Slovenia’s goals for adult learning (Action 1) and be overseen by the improved AE Body (Action 2). It should be supported by improved information on learning opportunities and outcomes (Action 3), local and regional stakeholders (Action 5) and cross-sectoral funding (Action 8).

More specifically, in designing and implementing a co-ordinated and comprehensive action plan for promoting adult learning to individuals and employers, consideration should be given to:

-

1. The target audience: how will the promotion be targeted to different groups of adults, including those under-represented in adult learning (e.g. low-skilled, inactive and older adults), as well as high-skilled adults.

-

2. Key messages: for example, the opportunities for adult learning in Slovenia, and potential benefits of participating in adult learning, using the information generated by Action 3, as well as personal success stories.

-

3. Key modes: the most effective modes of promotion (such as visits, group sessions, online, television and radio, print etc.) to be used for different target groups.

-

4. Roles and responsibilities: each sector should take a lead role for specific groups of adults, for example:

-

a. Trade unions should formally adopt the promotion of adult learning for workers as a priority, and take a lead role in raising awareness among working adults, particularly those with low levels of skills and education.

-

b. Employers’ associations should make promotion of employer-sponsored training one of their priorities, and take a lead role in motivating employers to invest in the skills of workers, particularly for micro and small enterprises. Individual employers should play a greater role in informing workers about relevant learning opportunities.

-

c. MICs should co-ordinate with local employers’ associations and trade unions to promote sector- and technology-specific training opportunities among local enterprises and adults.

-

d. LUs and guidance counsellors should take a lead role in raising awareness among disadvantaged or marginalised adults in their regions, invest in their promotional capacity, and develop effective, proactive outreach strategies.

-

e. The ZRSZ and CSD should take a lead role in raising awareness among unemployed adults and those receiving social benefits.

-

f. Pre-schools and schools should take a lead role in raising awareness among parents with low levels of skills, and refer them to guidance counsellors, LUs and other local providers.

-

g. Publicly funded media outlets should serve as the main media platform for raising general awareness of the benefits of and opportunities for adult learning.

-

-

5. Expanding existing campaigns and initiatives: including Slovenia’s Lifelong Learning Week and the ACS Awards.

-

6. Governance: the action plan should ultimately be geared towards achieving the goals and priorities of the adult-learning master plan (Action 1), overseen by a whole-of-government, cross-sectoral adult-learning body (Action 2) with input from the Expert Group for Lifelong Career Guidance, and underpinned by performance indicators and ongoing evaluation.

Improve co-operation to fund adult learning effectively and efficiently

Shared, sustainable and well-targeted funding is essential for improving participation, outcomes and cost effectiveness in adult learning. Funding of this sort requires effective co-ordination between government, social partners and learners (OECD, 2003, p. 221[21]).

Total expenditure on adult learning needs to be high and stable enough to support participation, particularly among disengaged groups. Neither the central government, municipalities, employers nor individuals have sufficient resources to provide this funding alone, making co-financing essential in adult learning.

Co-financing of adult learning is also important because individuals, employers and society typically share the benefits of adult learning (OECD, 2017[22]). Individuals can accrue direct personal, employment and social benefits from participating in adult learning. Employers benefit when education and training leads to more motivated, adaptable and productive workers. Society as a whole benefits from adult learning when it improves employment and earnings, as this increases tax revenues and lowers public spending on labour market programmes. Society also benefits from adult learning that empowers adults to be healthier and more trusting of others, and active in volunteering and voting (OECD, 2016[23]).

Yet, despite these widespread benefits, in certain cases adult learning may not occur without targeted government support (OECD, 2017[22]). Financial barriers are acute for those earning low incomes and older workers. In Slovenia, adults who want to participate in learning but face barriers to doing so, cite costs as their main barrier. Individual employers may lack financial incentives to invest in workers’ general skills as opposed to those specific to their business. Smaller employers in particular may lack the management capacity, time and budget to make substantive investments in training. Targeted public funding is therefore likely to be necessary for disadvantaged groups (such as adults with low incomes), certain types of businesses (such as smaller enterprises) and certain types of training (such as for general skills).

Current arrangements for funding adult learning

Nine ministries reported expenditure on adult-learning related programmes in Slovenia’s 2018 Annual Plan for the Adult Education Master Plan (Letni program izobraževanja odraslih v Republiki Sloveniji) (LPIO) (2017[24]), totalling EUR 82.7 million. In total, over half of this expenditure (57%) is sourced from the European Social Funds (ESF) (Table 4.2).

While not currently included in the action plan, the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (Ministrstvo za gospodarski razvoj in tehnologijo) (MGRT) also funds several programmes that include adult learning, such as Slovenske poslovne točke and entrepreneurship training for highly educated unemployed women.

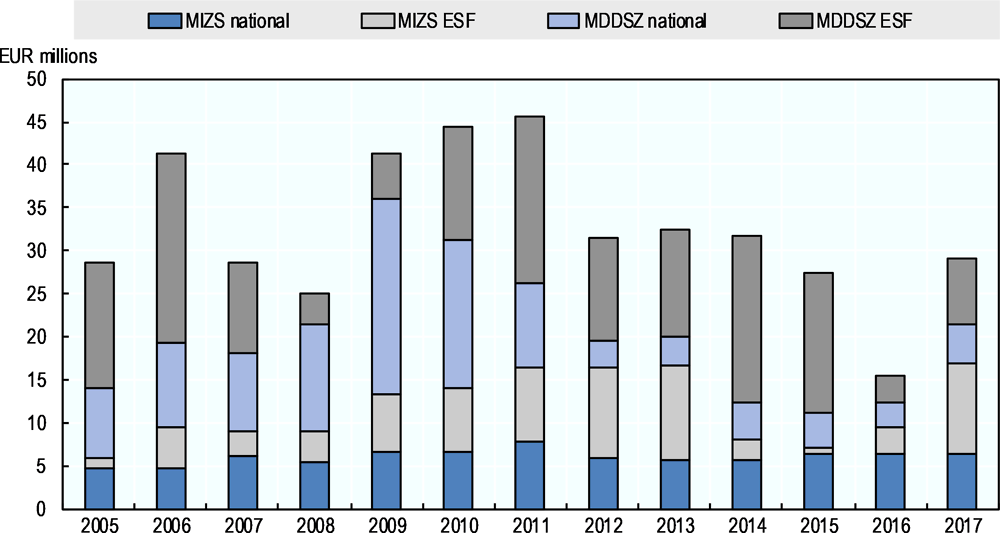

Central government funding of adult learning has fluctuated considerably since 2005, reflecting variations in both national and ESF funding (Figure 4.2).

The amount and continuity of public expenditure on adult learning in Slovenia differs depending on the form and level of education. Public funding of adult learning is highly concentrated in non-formal, predominately job-related education and training (Table 4.3). Public funding of adult learning is largely project (ESF) based, available in some periods and not in others, but this differs across types of learning (Annex Table 4.A.1). For example, permanent public funding is available to cover the full, upfront costs of second-chance basic education (ISCED 1-2). However, public funding is largely project-based and occasionally available for second-chance secondary education (ISCED 3), and rarely available for tertiary education and training (currently only ISCED 5). Most major publicly funded programmes for non-formal education and training are project (ESF) based and funded.

Many of Slovenia’s 212 municipalities fund adult education programmes, although this varies considerably between municipalities (Table 4.4).

Relatively limited data are available on businesses’ expenditure on adult learning in Slovenia. The available data suggest that enterprises in Slovenia’s industry (manufacturing) sector, and in the information and communication, financial and insurance services sectors spend a relatively large amount on CVT. In contrast, those in the construction sector spend relatively little (Figure 4.3). Overall, Slovenian enterprises spend EUR 688 on CVT per employed person, above the EU average of EUR 585 (adjusted for purchasing power parity) (Eurostat, 2018[3]).

Slovenia’s Employment Relationship Act (2013) provides that employer support for adult education and training be specified in a contract or collective agreement. A relatively high share of employees in Slovenia are covered by collective agreements: 65%, compared to only 33% across the OECD in 2013, although this share has steadily declined from 100% in 2005, when membership of an employers’ association was made voluntary (OECD, 2017[14]). Furthermore, the generosity of provisions for workers’ education and training differs considerably between agreements (Table 4.5).

Slovenia does not collect data on individuals’ expenditure on adult learning. While the SURS’ 3-yearly household survey (Anketa o porabi v gospodinjstvih) asks respondents how much they spend on primary, secondary, tertiary and “other” education, it is not possible to reliably isolate expenditure on adult education. The government should expand its adult-learning data collection (Action 3).

Some government agencies enter co-funding arrangements with employers when implementing specific adult-learning programmes. For example, the MDDSZ funds 50-70% of the training and other services delivered by KOCs, with participating employers funding the rest. Under the public tender for co-financing informal education and training of employees, the JŠRIP funds 70% of employees’ non-formal education and training costs, up to a specified limit (Table 4.7).

Sectoral education and training funds are now uncommon in Slovenia. Until 2008, the collective agreement of the national Chamber of Craft and Small Business of Slovenia (Obrtno-podjetniška zbornica Slovenije) required members to contribute 1% of the minimum wage per employee to an education fund. Employers were entitled to reimbursement for education and training expenses as specified by the collective agreement. The collective agreement no longer establishes a national education fund, but allows members of regional chambers to establish their own funds. As a result, four regional chambers established the Foundation for Employee Training (Zavod za izobraževanje delavcev) which covers businesses in approximately 30 municipalities around Ljubljana. The Education Fund Maribor (Sklad za izobraževanje Maribor) was established by four regional chambers, but is expected to be closed in 2019.

As in many EU countries, the system for ministries and adult-learning providers to access EU funds is rather complex. It is regulated by several EU and national laws, and involves different managing authorities and bodies: the Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy (Služba Vlade Republike Slovenije za razvoj in evropsko kohezijsko politiko) (SVRK) is the managing authority while individual ministries are intermediate bodies. Two national manuals and two national guidelines, as well instructions provided by the individual ministries, seek to outline this process. For the programme period 2014-20, the process broadly involved:

-

At the EU level, the EU cohesion budget and strategic orientations for EU cohesion policy are formulated.

-

At the national level, the SVRK (as the managing authority) prepares a partnership agreement in co-operation with other ministries and stakeholders.

-

The SVRK co-ordinates and confirms the Operational Programme for the Implementation of the EU Cohesion Policy with the EC (October-December 2014), which forms the basis for ministries to prepare individual project proposals as intermediate bodies.

-

Ministries co-ordinate and confirm individual project proposals with the SVRK, as the managing authority responsible for the compliance of the projects with provisions in EU and national legislative and strategic documents.

-

Ministries release public tenders and select providers.

-

During the implementation of projects, intermediate bodies or the Budget Supervision Office will conduct several content, administrative and financial audits, and contractors submit a substantive and financial (intermediate and financial) report on the progress of the project.

-

Ministries review contractors’ reports and, once satisfied, pay the contractors. Audits of the project may be conducted after completion.

Opportunities to improve co-operation on funding of adult learning

There are a number of strengths and good practices in the way adult learning is funded in Slovenia. A large number of ministries (10) fund adult-learning related programmes, covering the sectors and groups with which they work most closely. Second-chance basic education (ISCED 1-2), various basic skills programmes and guidance services are established as public services and fully publicly funded. In 2018, public expenditure on adult learning will reach its highest level since at least 2005. Many municipalities are funding adult-learning services. The share of Slovenian enterprises funding CVT for their employees has risen over the last decade, and is relatively high by international standards. Overall, Slovenian enterprises spend considerably more on CVT than those across the EU on average. And there are examples of co-funding between government and employers on certain adult-learning related programmes.

However, the representatives of ministries and stakeholders participating in this project stated that government, employers and individuals need to fund adult learning more effectively and efficiently. This means better sharing the costs of learning, ensuring funding is sustainable, and better targeting funding to where it will yield the highest overall returns for individuals, enterprises and society.

Several participants in this project questioned whether the total amount of funding for adult learning in Slovenia is sufficient. The relationship between funding and participation is not straightforward in the countries with available data on adult-learning funding (Box 4.5). However, a threshold level of funding for adult learning is important to make the system viable, and enhance both access and quality.

Existing data suggest that spending on adult learning from public and private sources ranges from 0.6% to 1.1% of gross domestic product (GDP) across 18 OECD countries with available data. Government spending amounts to about 0.1% to 0.2% of GDP. Employers are the main funders of adult learning, typically providing around 0.4% to 0.5% of GDP. Individuals spend around 0.2% to 0.3% of GDP.

No straightforward correlation between funding and participation

Countries with the highest level of spending on active labour market policies (ALMPs), from 0.9% to 1.8% of GDP, such as Denmark, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands, also have the highest probability of participation in adult learning among disadvantaged adults, with 35% to 42% of adults reporting having participated in adult learning over the past 12 months. However, countries like Austria, Belgium or Germany spend higher shares of GDP on adult learning (0.7-0.9% of GDP), than countries like Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom (0.1-0.3%), but they have lower participation rates among disadvantaged adults (20-25% as opposed to 25-30%). Countries achieving relatively high participation with lower expenditure tend to target funding on a smaller group of people (the most disadvantaged).

Funding and outcomes: Insights from PISA

At the school level, funding levels are positively associated with students’ outcomes up to a certain point. The OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data show that in countries with cumulative expenditure per student below USD 50 000 annually, the effect of spending is significantly associated with higher PISA scores. But for countries with cumulative expenditure above USD 50 000, like Slovenia and most other OECD countries, the effect of spending is not significant.

Sources: FiBS and DIE (2013[27]), Developing the Adult Learning Sector. Lot 2: Financing the Adult Learning Sector; Desjardins (2017[28]), Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems: Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies and Constraints; OECD (2018[29]), Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Portugal: Strengthening the Adult-Learning System, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298705-en.

Total public funding of adult learning in Slovenia for 2018 (EUR 82 million) equates to approximately EUR 210 per low-skilled adult, or EUR 70 per adult (Table 4.6).

Funding needs to be sufficient to support low-skilled adults to develop their skills. About 50 000 (12%) low-skilled adults in Slovenia reported that although they wanted to participate in formal or non-formal education, they had been prevented from doing so. Cost or lack of financing is the barrier most frequently cited by low-skilled adults in Slovenia, more frequently than in the OECD overall (OECD, 2017[11]). It is essential to target funding to the adults who need it most, especially the low-skilled and unemployed. It is also essential that the government systematically evaluates the outcomes being achieved by publicly funded programmes and providers, in order to allocate funding more effectively over time (Action 3).

The instability of public funding for adult learning in Slovenia threatens the sector’s ability to achieve national goals for adult learning. Overall, participation in adult learning and public expenditure on it have followed a similar profile in Slovenia over the last decade (Figure 1.2 in Chapter 1 and Figure 4.2), highlighting the role of public funding in supporting participation. For the MDDSZ and the MIZŠ, which account for almost 70% of public expenditure on adult learning, total expenditure has ranged from EUR 45.5 million in 2011 down to EUR 15.5 million in 2016 (Figure 4.2). The largest variations have been in MDDSZ funding for training-related ALMPs. This is a concern given the link between ALMP expenditure and participation by disadvantaged adults (Box 4.5). Indeed, in Slovenia, participation in learning by unemployed adults has declined over the last decade (Figure 1.2 in Chapter 1). Furthermore, several representatives of adult-learning providers involved in this project reported that funding volatility has resulted in substantial staff redundancies and programme reductions in years of low funding. They saw this as a threat to the long-term development and performance of the adult-learning sector.

Low-educated adults typically do not receive public funding to complete their upper secondary education (vocational or general), which hinders learning of this form. In 2016, only 12.7% of adults (25-64 year-olds) in Slovenia had not attained an upper secondary education or higher, well below the OECD average of 21.6% (OECD, 2017[31]). For the few who do not have a basic school education (ISCED 2), completing it is a legally guaranteed right and is free of charge. However, for those who wish to complete an upper secondary education (ISCED 3), public funding is only sometimes available, and then only as a reimbursement. Several participants in this project stated that adults are often not aware of this funding, and many do not access it because they cannot afford the upfront costs.

Slovenia’s adult-learning system is highly reliant on the ESF. In Slovenia’s 2018 LPIO, 57% of total adult-learning expenditure of the nine ministries is EU funded. EU funding accounts for as much as 77% of MDDSZ expenditure and 72% of MIZŠ expenditure. Reliance on the ESF has drawbacks (OECD, 2018[29]).

First, EU funding may fall in the future, as the EU reconsiders its priorities in a context of increased demands, from migration to security and defence. In addition, the EU budget will be reduced by the United Kingdom’s departure (European Commission, 2017[32]). As of May 2018, the EC’s proposal for the “ESF+” for 2021-27 is a total budget of EUR 89.7 billion (constant prices, up from EUR 86.4 billion in 2014-20) (Lecerf, 2018[33]). However, the proposed ESF+ would have a broader scope of issues to cover than the current one (including migrants and social integration). The funding available for adult learning in Slovenia is yet to be negotiated.

Second, as EU structural funds are time limited and distributed through public tenders, gaps can open up in the provision of learning opportunities in between programming periods, or when policy changes occur and require public authorities to re-apply for EU funds and launch public tenders. Some ministries stated that this has contributed to significant gaps in provision, lasting 1-2 years at the beginning of the operational periods (2007 onwards and 2014 onwards). For example, the MIZŠ’ first education programmes for the operational period 2014-20 did not start until the beginning of 2016, and contributed to the staff reductions in the adult-learning sector noted earlier.

On the other hand, the reliance on EU funding brings with it pressure for Slovenia to meet the EC’s growing expectations of evaluation and accountability in adult learning. A comprehensive outcomes evaluation framework (Action 3) is essential in this regard.

Several participants in this project stated that administrative complexity associated with Slovenia’s tender- and project-based approach to funding adult learning has also contributed to project delays and gaps in service provision. Some ministries (as intermediate bodies) cited complex EU and national processes for accessing EU funds and distributing it via tenders, referencing Slovenia’s lengthy national manuals and guidelines. Some representatives from the local level also noted the complexity of tendering for service contracts, and cited a lack of contracting skills at the local level (see Actions 4 and 5). They also stated that the timing of national tenders is unpredictable, and often not aligned with municipalities’ budget cycles. As a result, municipalities, LUs and others are sometimes precluded from accessing funds and delivering services to their communities. The EC proposes to simplify the management and payment of funds and reduce the number of controls and audits for the ESF+ in order to reduce administrative burden (European Commission, 2018[34]). The SVRK is seeking to develop measures to reduce the administrative burden for beneficiaries in the partnership agreement.

While many municipalities fund adult education, some are lagging behind. Funding of adult education varies considerably by municipality, and some municipalities provide no funding at all (Table 4.4). This may perpetuate regional disparities not only in adult-learning access and participation, but in economic and social development. Lagging municipalities should develop Adult Education Annual Plans, unilaterally or jointly with neighbouring municipalities, and commit funding to support adult learning.

Social dialogue and collective agreements have not ensured employers in different sectors and of all sizes are effectively investing in the skills of working adults. At the national level, the Economic and Social Council (Ekonomsko-socialni svet) (ESS) rarely discusses adult skills and learning-related policy (see Action 7), and has not specifically discussed cross-sectoral funding mechanisms. At the sectoral level, some collective agreements – the Paper and Paper-converting Industry, Crafts and Entrepreneurship, Construction, Public Utility Services, Electricity Industry, etc. – have only limited provisions for supporting education and training for workers (Table 4.5). Employers in some sectors – construction, and trade, transport, accommodation and food services – spend relatively little on CVT by national and/or international standards (Figure 4.3). As such, many low-skilled workers in these sectors are not benefiting from employer-sponsored continuing vocational training.

As the coverage of collective agreements continues to decline, and new forms of non-standard work arise, social partners and government will need to find new ways to support education and training for different sectors, enterprises and workers.

Slovenia lacks a systematic approach for government, employers and individuals to appropriately share the costs of skills development. There is co-funding between government and employers, but it is ad hoc and programme dependent. Sectoral training funds are rare in Slovenia, and the few that remain do not receive contributions from public sources. One Slovenian study (Drofenik, 2013[35]) which conducted inter-ministerial and cross-sectoral focus groups found general support for sectoral training funds, and noted the importance of having social partners leading the design of these funds.

A more comprehensive, shared and sustainable financing mix for adult learning, with more targeted support for those adults, and enterprises, which stand to benefit most from training but lack the capacity to pay, should be a priority for Slovenia. There are a range of comprehensive financing measures that Slovenia could consider to support concerted action between multiple stakeholders of adult learning.

Examples of good practice in sharing the costs of adult learning

There are a small number of promising examples of co-financing of adult-learning programmes in Slovenia (Table 4.7). The KOC programme has provided human resources and training support to employers, and is co-funded by the JŠRIP and the participating employers. The experience has shown that involving employers in the design/delivery of these programmes is important to encourage co-financing. The Non-formal Education and Training of Employees programme is co-funded by JŠRIP and participating employees.

Several countries provide targeted support to adults wishing to complete their upper secondary education. As of 2015, the Flemish Community of Belgium, Denmark, Spain and Sweden had financial schemes specifically aimed at supporting low-educated adults wishing to undertake upper secondary education. These targeted co-funding measures mainly take the form of specific grants and allowances, but also include training vouchers or paid training leave (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[38]). In Sweden, second-chance upper secondary education is offered free of charge. Finland goes even further, covering not just tuition costs but the foregone earnings of adults participating in formal education. Its Adult Education Allowance is publicly funded and replaces the foregone earnings of employees and self-employed persons who decide to pursue vocational studies. To be eligible for the allowance, the applicant must participate in studies leading to a degree, or in vocational or continuing education organised by a Finnish educational institution under public supervision.

Various models exist to establish cost-sharing approaches between government, employers and individuals (OECD, 2018[29]). In Norway, for example, funding responsibility is based on who is expected to benefit from the learning (Box 4.6). This is complemented by active policy efforts to enhance the quality of all adult-learning activity, including non-formal learning.

Norway’s shared funding model for adult learning seeks to assign responsibility for funding to the party that is expected to benefit from the education or training. Norway distinguishes between programmes that provide basic skills, enhance job performance or support worker mobility. It considers that government and society benefit most from increasing the basic skills of its population, while employers benefit from job-specific training leading to productivity gains, and individuals from training that raises their employability or mobility in the labour market. In practice, costs are generally shared in the following ways:

-

Developing basic skills: the national Ministry of Education and Research supports basic skills through funding The Basic Competence in Working Life Programme (EUR 16.4 million in 2017) in workplaces. Any employer, public or private, can apply for funding for projects that meet key criteria defined by the Ministry of Education and Research. These are:

-

Basic skills training should be linked to job-related activities and learning activities should be connected with the normal operations of the employer.

-

The skills taught should correspond to those of lower secondary school level. Courses need to reflect competence goals in the Framework for Basic Skills for Adults.

-

Courses should be flexible to meet the needs of all participants and to strengthen their motivation to learn.

-

-

Second-chance school: municipal or county authorities cover the cost of second-chance school education for adults (primary and secondary level), making it free of charge for participants.

-

Tertiary education: individuals or their employers pay for continuing education courses in public universities and university colleges that prepare them for the labour market or improve the quality of life.

-

General non-formal education and training: the government and individuals co-fund non-formal adult learning and education provided by adult education associations.

-

Job-related non-formal education and training: private enterprises providing further education for their employees not related to basic skills, for example, in the form of on-the-job training, cover the full costs. Trade unions also have funds for further and continuing education, for which their members can apply.

Sources: OECD (2018[29]), Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Portugal: Strengthening the Adult-Learning System, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298705-en; Eurydice (2018[39]), Norway: Adult Education and Training Funding, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/adult-education-and-training-funding-54_en; Bjerkaker (2016[40]), Adult and Continuing Education in Norway, https://doi.org/10.3278/37/0576w.

Public funding can be used to leverage private funding, especially from social partners (OECD, 2018[29]). Such mechanisms can take various forms, including agreements between government and social partners that contain both funding commitments and objectives. Examples from France and the Netherlands featured in a recent OECD review of financial incentives (2017, pp. 94-95[22]):

-

In France, the Employment and Skills Development Actions programme aims to help employers solve sectoral skills pressures. It provides government funding for specific skills development projects, which are then designed and implemented by social partners.

To implement this programme, a framework agreement is signed between the government and an employer organisation to make funding available for various training programmes. The amount of funding is negotiable and depends on the nature of the planned interventions, the size of the employers involved, the degree of disadvantage of the groups targeted and the extent of the co-financing from employers.

-

In the Netherlands, Sector Plans are temporary plans to help overcome specific education and training challenges in certain sectors or regions, such as a mismatch between the demand for and supply of labour. The social partners are heavily involved in drafting and implementing these plans, and contribute a substantial share of the funding, but the state covers up to 50% of the total cost for a period of up to 24 months (36 months in the case of work-based training or work-based qualifications, a specific type of vocational training.)

Recommended Action 8: Improve co-operation on funding adult learning

In light of these current arrangements, challenges and good practices, the central government, municipalities, employers, social partners and individuals could improve their co-operation on funding adult learning effectively and efficiently. They can do this by taking the following actions.

Action 8

The government, employers and their associations, trade unions and adult learners should more systematically share, target and streamline the funding of adult learning.

The ESS, with support from the expanded AE Body (Action 2), should develop a high-level “funding agreement” outlining how government, employers and individuals should share the costs of investing in different types of adult learning and skills.

The government should provide full, upfront financial support to low-skilled adults to attend second-chance and basic skills programmes. Social partners should strengthen provisions for education and training in lagging collective agreements, and the government should monitor their implementation. In sectors with relatively low expenditure on or participation in adult education and training, social partners should pilot sectoral training funds, which the government should partially co-finance. In particular, these funds should support low-skilled workers, those not covered by collective agreements or in non-standard work, as well as micro and small enterprises. Finally, the ministries involved in adult learning and the SVRK should jointly review, streamline and improve national processes for accessing and allocating EU funds, as part of broader streamlining efforts.

Slovenia’s shared funding arrangements for adult learning should ultimately support the achievement of its goals for adult learning (Action 1). Funding priorities should be discussed by the expanded AE Body (Action 2) and increasingly based on improved information on learning activities and outcomes, and skills needs and mismatches (Action 3).

More specifically:

-

1. In the ESS, government, social partners and representatives of adult learners should develop a high-level “funding agreement” for shared and sustainable funding, to underpin the achievement of Slovenia’s adult-learning master plan (Action 1).

-

a. The agreement should outline broad parameters for how government, employers, social partners and individuals will share the costs of different types of adult learning, based on:

-

i. Who benefits from different types of adult learning and skills? For example, employers might pay more for job-related than non-job-related learning, and individuals might pay more for transversal education and training.

-

ii. Who incurs costs due to adult learning? For example, financial support might be needed for workers and employers who forego income for training.

-

iii. Who has capacity to pay for adult learning and skills? For example, high levels of public support for adults with relatively low incomes, and support from public and sectoral funds for micro and small enterprises.

-

-

b. It should also specify the main funding mechanisms (for example, sectoral training funds or government subsidies) and target levels of expenditure for each sector, in order to realise Slovenia’s goals for adult learning.

-

-

2. As part of this funding agreement, central government, municipalities, employers and social partners should improve funding for target groups of adults:

-

a. The government should minimise cost-related barriers to adults with low education/levels of skills participating in learning, by guaranteeing full and upfront financial support to all adults who participate in:

-

i. second-chance school education at the upper secondary level

-

ii. basic skills training (e.g. literacy, numeracy and digital).

In terms of eligibility, this training could be made available to all adults:

-

a) whose educational attainment is below the upper secondary level

-

b) who are objectively assessed by a guidance counsellor or other professional as having low proficiency levels in literacy, numeracy and/or digital skills, for example as measured by the OECD’s Education and Skills Online tool.

-

-

-

b. Social partners should strengthen provisions for education and training in lagging collective agreements, aligning them with current best practice, such as the collective agreement for the Banking and Finance sector. The government should particularly monitor the implementation of education and training in these lagging sectors.

-

c. In sectors with relatively low investment or participation in adult education and training, social partners should pilot sectoral training funds, and the central government and relevant municipal governments should contribute to these funds. In particular, social partners and government should seek to improve financial support for micro and small enterprises, low-skilled workers, workers not covered by collective agreements and workers in non-standard forms of work (e.g. temporary) to enable them to access the benefits of training.

-

-

3. Ministries, municipalities and stakeholders should make better use of European Union funding for adult learning, in order to improve participation, outcomes and/or cost effectiveness. This could be achieved by:

-

a. Simplifying national procedures and guidance for accessing and allocating EU funds: as part of broader streamlining efforts, the ministries involved in adult learning and the SVRK should jointly review, streamline and otherwise improve national processes for accessing and allocating EU funds as a priority, without undermining due process and probity. In doing so, they should identify and adapt relevant examples from the EC and other EU member countries.

-

b. Starting to plan for new financial periods earlier: for example, assess opportunities to commence strategic national planning and inter-ministerial co-ordination for the new financial period (2021-27), in preparation for effective bilateral strategic planning and negotiation with the European Commission, to minimise future gaps in adult-learning expenditure.

-

c. Raising skills for commissioning and contracting services: for example, expanding learning and development opportunities for the public administration (Action 4), and developing and co-funding training for municipalities and local/regional stakeholders on utilising EU funds. This could involve extending training in skills for commissioning and contracting services to the local level (Action 5).

-

d. Systematically forming beneficial inter-ministerial and cross-sectoral partnerships in adult learning.

-

References

[5] ACS (2018), LLW – Slovenian Lifelong Learning Week, Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, https://llw.acs.si/about/ (accessed on 21 October 2018).

[6] ACS (2017), Osebna izkaznica projekta TVU [Identity Card of TVU], Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, http://tvu.acs.si/datoteke/TVU2017/Osebna%20izkaznica%20TVU%202017.pdf.

[40] Bjerkaker, S. (2016), Adult and Continuing Education in Norway, Bielefeld, https://doi.org/10.3278/37/0576w.

[19] Cedefop (2018), New framework for promoting lifelong learning and adult education, Cedefop website, http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/croatia-new-framework-promoting-lifelong-learning-and-adult-education.

[41] CeZaR (2018), Statistični podatki o knjižnicah [Statistical data on libraries], Slovenian Library Network Development Centre, https://cezar.nuk.uni-lj.si/statistika/index.php (accessed on 04 November 2018).

[9] Council of the European Union (2011), Council Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32011G1220%2801%29.

[28] Desjardins, R. (2017), Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems: Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies and Constraints, Bloombsbury.

[35] Drofenik, O. (2013), Izobraževanje odraslih kot področje medresorskega sodelovanja (Adult Education as the Inter-Ministerial Field), Slovenian Adult Education Association, Ljubljana, http://arhiv.acs.si/porocila/Izobrazevanje_odraslih_kot_podrocje_medresorskega_sodelovanja.pdf (accessed on 03 October 2018).

[34] European Commission (2018), “Questions and answers on the new Social Fund and Globalisation Adjustment Fund for the period 2021-2027”, Fact Sheet, No. MEMO/18/3922, European Commission, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-3922_en.htm (accessed on 02 September 2018).

[32] European Commission (2017), “Reflection paper on the future of EU finances”, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/reflection-paper-eu-finances_en.pdf.

[13] European Commission (2015), An In-Depth Analysis of Adult Learning Policies and their Effectiveness in Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2767/076649.

[10] European Commission (2012), Strategies for improving participation in and awareness of adult learning, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2766/26886.

[38] European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015), Adult Education and Training in Europe: Widening Access to Learning Opportunities, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/doi:10.2797/75257.

[1] Eurostat (2018), Adult Education Survey (AES), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 17 October 2018).

[3] Eurostat (2018), Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

[30] Eurostat (2018), Population on 1 January by age group and sex (database), http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=demo_pjangroup&lang=en (accessed on 02 November 2018).

[39] Eurydice (2018), Norway: Adult Education and Training Funding, Eurydice, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/adult-education-and-training-funding-54_en (accessed on 15 October 2018).

[27] FiBS and DIE (2013), Developing the Adult Learning Sector. Lot 2: Financing the Adult Learning Sector, Report prepared for the European Commission/DG Education and Culture, Berlin.

[24] Government of the Republic of Slovenia (2017), Letni program izobraževanja odraslih v Republiki Sloveniji za leto 2018 [Annual Plan for the Adult Education Master Plan 2018], http://www.mizs.gov.si/fileadmin/mizs.gov.si/pageuploads/podrocje/odrasli/Letni_program_izobrazevanja/2017/LPIO_2018_sprejet_na_vladi_-_27.7.2017.doc.

[42] GZS (2018), SPOT, Slovenska poslovna točka (Slovenia Business Link), https://www.gzs.si/SPOT (accessed on 04 November 2018).

[8] Hergan, M. et al. (2016), Vocational Education and Training in Europe: Slovenia, VET in Europe Reports, Cedefop, http://libserver.cedefop.europa.eu/vetelib/2016/2016_CR_SI.pdf.

[7] Ivančič, A., V. Špolar and M. Radovan (2010), Access of Adults to Formal and Non-Formal Education – Policies and Priorities: The Case of Slovenia, Andragoški Center Slovenije, Ljubljana, https://www.dcu.ie/sites/default/files/edc/pdf/sloveniasp5.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2018).

[18] Jelenc, Z. (ed.) (2007), Strategija vseživljenjskosti učenja v Sloveniji (Lifelong Learning Strategy in Slovenia), Ministry of Education and Sport of the Republic of Slovenia in cooperation with the Public Institute Educational Research Institute of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, http://www.mss.gov.si/fileadmin/mss.gov.si/pageuploads/podrocje/razvoj_solstva/IU2010/Strategija_VZU.pdf.

[36] JŠRIP((n.d.)), Javni štipendijski, razvojni, invalidski in preživninski sklad Republike Slovenije (Public Scholarship Development, Disability and Maintenance Fund of the Republic of Slovenia), http://www.sklad-kadri.si/ (accessed on 13 October 2018).

[15] Kanjuo Mrčela, A. (2018), Living and working in Slovenia, Eurofund, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/country/slovenia#actors-and-institutions (accessed on 19 October 2018).

[33] Lecerf, M. (2018), “European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) 2021-2027”, EU Legislation in Progress, European Parliamentary Research Service, Brussels, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2018)625154 (accessed on 02 September 2018).

[17] MDDSZ (2018), Seznam reprezentativnih sindikatov (List of Representative Syndicates), Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, http://www.mddsz.gov.si/si/delovna_podrocja/delovna_razmerja_in_pravice_iz_dela/socialno_partnerstvo/seznam_reprezentativnih_sindikatov/ (accessed on 13 October 2018).

[25] MIZS (2018), Izobraževanja odraslih: LPIOs (2005-2017) [Adult education: LPIOs (2005-2017)], Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, http://www.mizs.gov.si/delovna_podrocja/direktorat_za_srednje_in_visje_solstvo_ter_izobrazevanje_odraslih/izobrazevanje_odraslih/.

[26] MIZŠ (2018), Poročilo o realizaciji Letnega programa izobraževanja odraslih Republike Slovenije za leto 2017 (LPIO 2017) [Report on the implementation of the Annual Plan for the Adult Education Master Plan 2017], Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, http://www.mizs.gov.si/delovna_podrocja/direktorat_za_srednje_in_visje_solstvo_ter_izobrazevanje_odraslih/izobrazevanje_odraslih/.

[29] OECD (2018), Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Portugal: Strengthening the Adult-Learning System, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298705-en.

[31] OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

[22] OECD (2017), Financial Incentives for Steering Education and Training, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272415-en.

[14] OECD (2017), OECD Employment Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2017-en.

[11] OECD (2017), OECD Skills Strategy Diagnostic Report: Slovenia 2017, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264287709-en.

[2] OECD (2017), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) database (2012, 2015), http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/ (accessed on 23 March 2017).

[23] OECD (2016), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.