Chapter 3. Strengthening co-operation between specific actors for adult learning

In addition to strengthening the overall conditions for co-operation in adult learning (Chapter 2), Slovenia has opportunities to strengthen co-operation between specific actors: between ministries, with and between local actors, and between government (including public providers) and stakeholders (adult learners, employers and others). This chapter presents each of these three areas for action with: 1) an overview of current arrangements; 2) a summary of current challenges and opportunities; 3) examples of good practice from Slovenia and abroad; and 4) recommended actions for strengthening co-operation in order to boost adults’ learning and skills.

Strengthen inter-ministerial co-ordination for adult learning

Effective co-ordination between Slovenia’s ministries will be essential for improving participation, outcomes and cost-effectiveness in adult learning. In Slovenia, nine ministries have legislated responsibilities in adult learning. Between them, these ministries fund 34 Adult Education Centres (Ljudske univerze) (LUs), 17 Guidance Centres for adults, 58 Employment Offices, 20 Inter-Company Training Centres (Medpodjetniški izobraževalni centri) (MICs), and 11 Competence Centres for Human Resources Development (Kompetenčni centri za razvoj kadrov) (KOCs), among other adult learning-related services. Against this backdrop, inter-ministerial co-ordination is crucial to minimise overlaps and gaps in services, share experience and sectoral expertise, identify opportunities for partnerships, design adult learning policy to positively interact with other related policies (such as labour, social and development policy), and develop better processes for engaging with municipalities and stakeholders (OECD, 2005[1]; OECD, 2003[2]).

Several factors can facilitate effective inter-ministerial co-ordination in adult learning, including clear and shared priorities, goals, targets and responsibilities (see Action 1); an inclusive, influential and accountable co-ordination body (see Action 2), and high-quality information to enrich decision making and co-ordination (see Action 3).

In addition, effective inter-ministerial co-ordination requires that civil servants are appropriately skilled, responsible and recognised for their efforts. It also requires sufficient resources – of people, time and funding. Getting these aspects right for inter-ministerial co-ordination can also help improve the public administration’s engagement with municipalities (Action 5) and stakeholders (Action 6) in adult learning.

Current arrangements for inter-ministerial co-ordination

Slovenia has several mechanisms to help prioritise, facilitate and support inter-ministerial co-ordination in adult learning.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the Adult Education Master Plan 2013-2020 (Resolucija o nacionalnem programu izobraževanja odraslih v Republiki Sloveniji za obdobje 2013-2020) (ReNPIO) and the Adult Education Co-ordination Body (Koordinacija izobraževanja odraslih) (AE Body) support inter-ministerial co-ordination in adult learning. Adult education is provided on the basis of the ReNPIO, which documents the national goals, priority areas and activities necessary for its realisation and public funding from the ministries involved in adult education. The AE Body includes nine ministries among its 24 members.

More broadly, various strategies, rules, ad hoc partnerships and human resource management practices in the public administration seek to facilitate effective inter-ministerial co-ordination.

The current development strategy, the Slovenian Development Strategy 2030 (Strategija razvoja Slovenije 2030) (SRS 2030), sets a goal for “effective governance and a high-quality public service” (Šooš et al., 2017[3]). It lists several measures to realise this goal, including creating a highly developed culture of co-operation; promoting the acquisition of new knowledge and skills through strategically thought-out human resources planning; and promoting innovative forms of management, leadership, policy design and innovation among employees. Furthermore, the Public Administration Development Strategy 2015-2020 (Strategija razvoja javne uprave 2015-2020) (SJU 2020) outlines the vision of an efficient and stable public administration, and includes objectives for improved inter-ministerial co-ordination, human resource management and skills development for civil servants (Box 3.1). Both the SRS 2030 and the SJU 2020 also include goals for more effective stakeholder engagement in the policy process, and a user-centred approach to public services (see Action 6).

The SJU 2020 was adopted by the government in 2015, and aims to improve the quality and efficiency, transparency and responsibility of public administration. Among its strategic objectives, the SJU 2020 includes the responsive, effective and efficient operation of a user-oriented public administration; efficient human resource management and enhancing the competence of civil servants; and improving legislation and including key stakeholders.

Inter-ministerial co-operation

The SJU 2020 recognises that the sectoral organisation of the public administration is an obstacle to inter-ministerial co-operation, resulting in higher costs and lower service quality. The main measure it identifies to improve cross-sectoral co-operation is to connect and merge the functions of related bodies at the state and municipal level. The indicator it defines for the efficient organisation of the central public administration is an “increased number of successfully implemented inter-sectoral reform projects”. According to the progress report (Government of the Republic of Slovenia, 2018[4]), 10 inter-sectoral reform projects were successfully implemented from 2015 to 2017. The SJU 2020 also set targets for the implementation of joint public procurement, in order to improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness of public procurement.

Developing skills in the public administration

The SJU 2020 recognises that training civil servants is essential for improving their motivation, skills and satisfaction, and for improving service quality and user satisfaction. The SJU 2020 suggested establishing a competency model (see Box 3.3) and modernised training including: 1) a methodology to determine training needs and prepare training plans based on the competence analysis of employees; 2) tailoring the training programmes to specific target group needs; and 3) enhancing opportunities and motivation for learning.

Performance management

One goal of the SJU 2020 was a closer connection between work performance, promotion and remuneration. It establishes the competency model as a measure to achieve this goal. The SJU 2020 defines two indicators for monitoring the connection between performance and remuneration: “increased share of employees whose salary increased due to above-average performance” and “increased average ratio between the variable and fixed components of public sector salaries”.

In order to achieve the objectives of the SJU 2020 a working group for monitoring and implementing the SJU 2020 was established in 2017, consisting of strategic and operative groups.

Sources: MJU (2015[5]), Public administration 2020. Public Administration Development Strategy 2015-2020, www.mju.gov.si/fileadmin/mju.gov.si/pageuploads/JAVNA_UPRAVA/Kakovost/Strategija_razvoja_JU_2015-2020/Strategija_razvoja_ANG_final_web.pdf; Government of the Republic of Slovenia (2017[6]), Decision on the appointment of the Working group for monitoring and evaluation of the SJU 2020, www.mju.gov.si/fileadmin/mju.gov.si/pageuploads/JAVNA_UPRAVA/Kakovost/Strategija_razvoja_JU_2015-2020/KAZISklepVlade_Pa.pdf.

The 2001 Rules of Procedure of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia (Poslovnik Vlade Republike Slovenije) (Rules of Procedure) require inter-ministerial consultation and the harmonisation of proposals to government. The Rules of Procedure stipulate that proposals made to government for debate and decision (“government material”) must be harmonised across the ministries and government services it concerns, except when this is not possible due to urgency or for other reasons. When submitting government material, ministries must confirm the extent of their inter-ministerial consultation. The Government Office for Legislation checks ministries’ compliance with these requirements before proposals go to cabinet (National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia, 2014[7]).

The 2009 Public Sector Salary System Act (Zakon o sistemu plač v javnem sektorju) and subordinate decrees1 specify elements of inter-ministerial co-ordination that managers may use in performance appraisals and promotion decisions. The decrees stipulate that civil servants’ performance should be appraised and rated annually based on a wide range of criteria, one of which is the quality of co-operation and organisation of work, including mutual co-operation and teamwork, attitudes towards colleagues, knowledge transfer, and mentoring. The decrees also include criteria related to stakeholder engagement in policy making and attitudes towards service users (see Action 6).

Ministries can consult with each other informally and form ad hoc partnerships in adult learning. For example, the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport (Ministrstvo za izobraževanje, znanost in šport) (MIZŠ) establishes working groups when developing legislation, including other ministries as well as stakeholders. In addition, the national project team for the OECD-led National Skills Strategy for Slovenia consists of representatives of nine ministries. This team oversaw the Diagnostic Phase (2016-17) and Action Phase on governance of adult learning (2018).

Some training programmes available to civil servants cover skills for co-operation and engagement, which can support inter-ministerial co-ordination. The Administration Academy (Upravna akademija) has legislated responsibility to provide training of relevance to all ministries. It currently offers various communication, teamwork and leadership training programmes, among others (Table 3.1). The human resources (HR) units within ministries may also arrange or provide their own training for staff (see Annex Table 3.A.1 for more details).

The number and seniority of people, and the time and funding allocated to adult learning and inter-ministerial co-ordination differ by mechanism and ministry (see Annex Table 3.A.2 for details).

At the MIZŠ, adult education comes under the responsibility of Higher Vocational and Adult Education Division at the Secondary, Higher Vocational and Adult Education Directorate. The size of the division has gradually increased over the last 10 years due to the increased number of EU projects, and now typically employs 10-14 civil servants. The Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities (Ministrstvo za delo, družino, socialne zadeve in enake možnosti) (MDDSZ) also has a Lifelong Learning Division at the Labour Market and Employment Directorate, although the division is smaller than at the MIZŠ. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food (Ministrstvo za kmetijstvo, gozdarstvo in prehrano) (MKGP) has appointed staff specifically to oversee the ministry’s adult learning activities, but this is uncommon among sectoral ministries.

The MIZŠ has a budget line to support the work of the Council of Experts of the Republic of Slovenia for Adult Education (Strokovni svet Republike Slovenije za izobraževanje odraslih) (SSIO) and its sub-committees. The MIZŠ pays attendance fees for non-government representatives and remunerates the president of the SSIO. In 2017, the SSIO met four times, and its Commission for Strategic Issues met three times. The AE Body, on the other hand, has no budget line. The decision-making authority of its 9 ministerial representatives is diverse, ranging from mid-management to state secretaries. It currently meets twice per year, despite an initial plan to meet monthly.

Opportunities to strengthen inter-ministerial co-ordination

Representatives of the ministries participating in the National Skills Strategy Action Phase highlighted the potential to strengthen inter-ministerial co-ordination for adult learning. This opportunity has also been highlighted in previous studies (Ivancic and Radovan, 2013[8]; Jelenc, 2007[9]; Krek and Metljak, 2011[10]). Ministry representatives cited the need to develop a culture of co-operation in Slovenia’s public administration, particularly for improved adult learning policy. They argued that awareness, learning and development, and recognition for co-operation are needed, not more rules. Ministry representatives also raised concerns about the levels and variability of resources allocated to inter-ministerial co-ordination.

Rules are not enough

Ministry representatives agreed that there is scope to do more to achieve the intent of the Rules of Procedure in adult learning policy making. There are examples of effective inter-ministerial co-ordination of adult learning policies via existing co-ordination mechanisms. Yet the ministry representatives agreed that the process for inter-ministerial reviews of proposals does not consistently result in substantive input into the content of adult learning policy proposals. Civil servants often feel they are too busy to fully engage in these processes. When they do, it is often out of goodwill, as there are no major consequences for engaging only partially with the proposals of other ministries. A previous OECD review found that inter-ministerial consultation in general occurs too late for meaningful input from various ministries (OECD, 2012[11]). Ministries may also invoke the urgency clause to exempt their own proposals from the requirement for inter-ministerial consultation.

However, the ministry representatives agreed that rules are not the core issue – neither the current set of rules nor improvements to them will be sufficient to drive inter-ministerial co-ordination. While rules and individual goodwill are necessary, they cannot generate the culture, depth and consistency of co-ordination between the ministries involved in adult learning envisioned by the SRS 2030 and SJU 2020. More importantly, the public administration needs to develop a culture of co-operation. This requires, among other things, civil servants being convinced of the value of co-operation and having sufficient skills and recognition to work effectively with others.

Learning and development

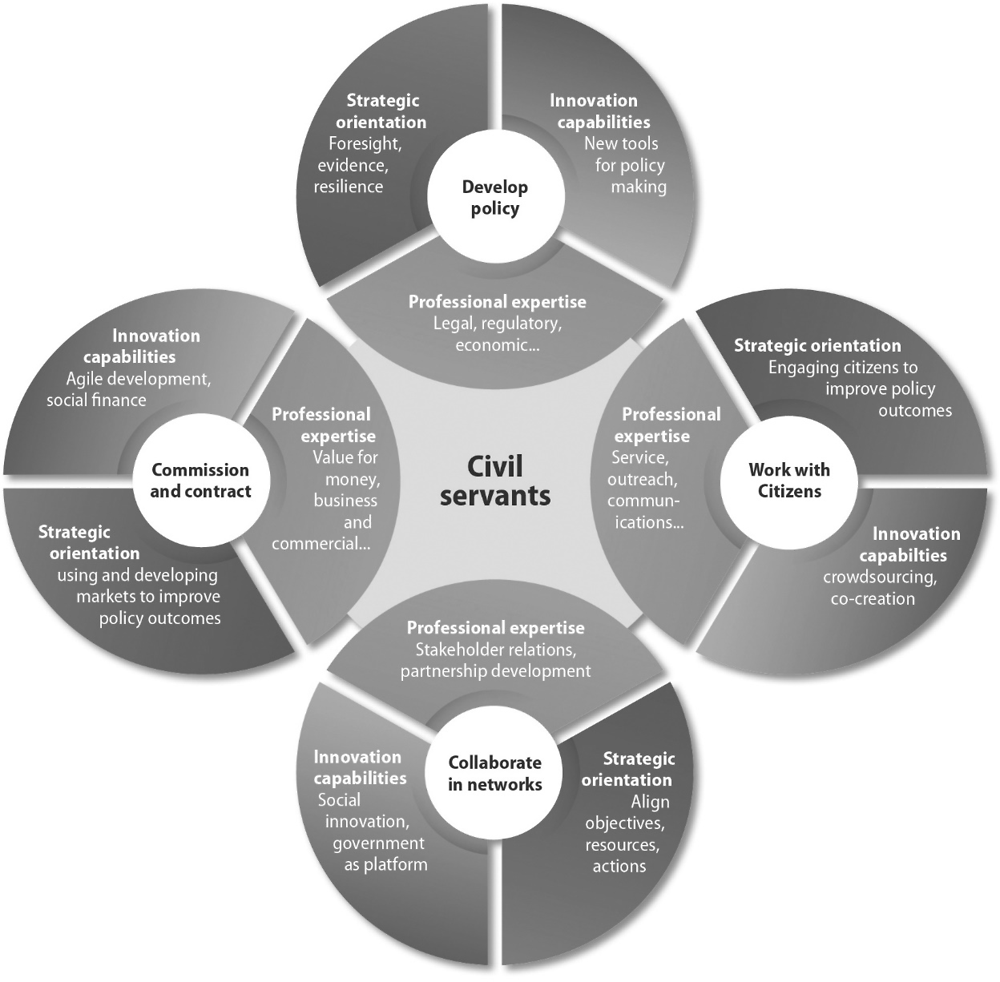

Ministry representatives stated that many civil servants may lack the skills and experience required for effective inter-ministerial co-ordination for adult learning, a point also made in a previous Slovenian study (Drofenik, 2013[12]). The OECD has identified four areas of skills required for modern civil services, each of which includes elements of co-operation (Figure 3.1). Effective inter-ministerial co-ordination requires civil servants to have skills to convene, collaborate and develop shared understanding through communication, trust and mutual commitment. Targeted training, inter-ministerial and cross-sectoral mobility assignments (exchanges), mentoring, coaching, networking, and peer learning can all help develop these skills (OECD, 2017[13]). In addition, these skills and forms of learning are also required for effective co-operation with municipalities (see Action 5) and stakeholders (see Action 6). If civil servants’ skills for co-operation are not developed, the impact of other actions to strengthen co-operation in adult learning will be diminished.

The public administration in Slovenia does not have a process for systematically assessing and responding to skills gaps among civil servants. Although the SJU 2020 envisions such a process, training needs are currently identified on an individual basis, typically during annual performance reviews. This information does not feed into the training delivery or procurement planning of the Administration Academy.

The supply and uptake of co-operation-oriented training programmes is limited in the public administration. Table 3.1 shows the seven programmes the Administration Academy offers that it identified as covering co-operation skills. Enrolment in these programmes ranges from 90 to 460 participants per year and some of the programmes are only available to managers. And, while the Administration Academy uses a range of channels to promote its training, none of the ministerial staff consulted during the project were aware these programmes existed. Furthermore, the amount of training offered by individual ministries differs considerably (see Annex Table 3.A.1), and may be insufficient to boost the skills needed to support a culture of co-operation.

Existing learning opportunities for civil servants have only recently started to move away from traditional teaching modes like lectures. More use could be made of experiential learning, mobility assignments, mentoring, coaching, networking and peer learning. In particular, participants noted that inter-ministerial staff mobility is rare in the central public administration. There is a programme for staff exchanges between the public and private sector (Partnerstvo za spremembe), but these are typically short (e.g. 1-2 weeks) and placements may not necessarily align with the individual’s policy area (e.g. adult learning). This is a missed opportunity for staff to develop a cross-sectoral view of complex issues like adult learning policy.

Responsibility and recognition

Individual performance plans are not systematically used in Slovenia’s central public administration to encourage inter-ministerial co-operation, including for adult learning policy. While the current decrees on promotions include criteria that could be used to recognise co-operation, inter-ministerial co-ordination is not explicitly mentioned. Ministry representatives reported that they are expected to engage in inter-ministerial co-ordination (and stakeholder engagement) as part of their work. However, the degree to which this is explicit, formalised and recognised varies across teams and ministries. Linking promotion criteria to co-ordination and co-operation efforts in adult learning would help legitimise them as a priority. As other reviews have highlighted, managers may need to be more convinced of the value of the annual performance process and given better training and guidance to use it to its full potential (MJU, 2015[5]; OECD, 2012[11]).

Resourcing for co-operation

In some cases, the resources allocated to inter-ministerial co-ordination in adult learning policy may be insufficient to support effective co-operation. Some ministerial participants stated that they lack the time required to properly invest in co-ordination and engagement activities for adult learning policy. Staff responsibilities for adult learning within individual ministries may be unclear or insufficient, and too few staff may be dedicated to co-ordination and engagement. One previous review concluded that the adult education unit in the MIZŠ would need to be strengthened and expanded to successfully implement the national master plan for adult education (Jelenc, 2007[9]). The Adult Education Association (2012[15]) argued that the MIZŠ’ current adult education unit is overburdened by administrative tasks and lacks time for policy development. It called for the creation of a stand-alone directorate for adult education. Some participants cited hiring freezes and restrictions on part-time or short-term positions as contributing to “a lack of time” for co-ordination. Representatives delegated to the AE Body or ad hoc bodies by their ministries typically lack the decision-making capacity required to enter into inter-ministerial partnerships or other forms of co-operation.

While not focused on adult learning policy, the OECD review Slovenia: Towards a Strategic and Efficient State (2012[11]) made several recommendations for improving inter-ministerial co-ordination in Slovenia (Box 3.2).

Slovenia: Towards a Strategic and Efficient State (OECD 2012)

Commissioned by the Ministry of Public Administration (Ministrstvo za javno upravo) (MJU) and the Government Office for Development and European Affairs (Služba Vlade Republike Slovenije za razvoj in evropskes zadeve) (SVREZ), this review identified the main issues to be addressed for the development of a stronger and more effective central public administration in Slovenia. It recommended, among other things:

-

Promoting collaboration in the culture of the central public administration, by:

-

developing incentive structures, for example by including collaboration as one of the competence criteria for individual performance assessments

-

encouraging the development of networks to facilitate trust and relationship building, and opportunities for more integrated and organic consultation and collaboration between organisations within the central public administration

-

ensuring that consultation between entities in the central public administration starts at the beginning of the policy- and rule-making process

-

fostering positive relationships between the centre and line ministries, through arm’s-length steering rather than heavy-handed rules and procedures

-

where roadblocks appear, obtaining “buy-in” at the political level and encourage a discussion in the relevant cabinet committee.

-

-

Addressing disconnects at the political and administrative interface.

-

Establishing a more coherent centre of government.

-

Building capacity for strategy implementation.

-

Strengthening capacities for the prioritisation, monitoring and evaluation of policies.

-

Strengthening the individual staff performance management system.

Source: OECD (2012[11]), Slovenia: Towards a Strategic and Efficient State, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264173262-en.

Examples of good practice for inter-ministerial co-ordination

Slovenia’s Management by Objectives and Competency Model projects being piloted in the MJU will provide an opportunity for the ministries involved in adult learning to strengthen responsibilities, recognition and training for inter-ministerial co-ordination in adult learning (Box 3.3).

Management by Objectives (Ciljno vodenje) pilot in the MJU

In pursuit of the SJU 2020 goal for an improved and standardised performance management system, the MJU is piloting the Management by Objectives project. The overall aim is to define concrete performance objectives for individual staff that link to the strategic objectives of the ministry as a whole. The pilot is being implemented in four development phases:

-

Phase 1: System and content-based setting of objectives and the design of the management by objectives methodology.

-

Phase 2: Testing the suitability of the management by objectives system in public administration (providing feedback, evaluating and preparing recommendations for improvements).

-

Phase 3: Information support for management by objectives.

-

Phase 4: Communication, knowledge transfer, promotion and support in using management by objectives across the whole public administration.

Phase 1 of the pilot is complete, and has defined goals for the MJU at the ministry, directorate, unit and individual level. The findings of the pilot project will guide the introduction of management by objectives to other ministries and state administration bodies.

Competency Model (Kompetenčnega modela) pilot in the MJU

In pursuit of the SJU 2020 goal for more efficient human resource management, the MJU is piloting the Competency Model project to define, assess and develop the competencies required in the public administration now and in the future. The model seeks to facilitate the optimal use of human resources by establishing a connection between annual interviews, performance assessment, the training system, remuneration and promotion for civil servants.

The project has already defined the competencies of commitment to professionalism, strengthening co-operation, proactive work and a user-centred approach. The co-operation competency includes behaviour like “successfully co-operates with individuals who come outside of his / her working group”. These competencies will be further elaborated in the next steps of the project. The model will form the basis for analysing competency gaps in the civil service and organising training and career orientation services.

Sources: MJU (2017[16]) Management by Objectives, www.mju.gov.si/si/delovna_podrocja/kakovost_v_javni_upravi/ciljno_vodenje/; information provided by the MJU (10 August 2018); MJU (2018[17]), Establishing Competency Model, www.mju.gov.si/si/delovna_podrocja/zaposleni_v_drzavni_upravi/projekt_vzpostavitev_kompetencnega_modela/; data provided by the MJU (10 August 2018).

In Ireland, the government’s Civil Service Renewal Plan aimed to create a more unified and responsive civil service, including strengthening skills for policy making (Box 3.4).

Ireland launched a three-year action plan in 2014 that aimed to create a more unified and responsive civil service with the capacity to address the changes resulting from the economic recovery. This Civil Service Renewal Plan included actions to equip civil servants with the skills they need in a changing environment and to strengthen and expand their capacity for co-ordination with stakeholders. The plan was developed by an independent panel and a taskforce of civil servants from across all departments.

A key action was the development of a new shared model for delivering learning and development within the civil service.

This model called for a unified Learning and Development Strategy to be drawn up based on assessments of future skill requirements within the service. From this, common learning and development programmes were to be established and shared between departments. As of 2017, this curriculum had been agreed upon and adopted, and the contracts awarded to training providers. This was co-ordinated by the One Learning Centre, established to centrally operate and maintain the new model of delivery and suite of programmes. These programmes were designed to introduce new skills and behaviour and are to be reinforced by evaluations intended to ensure consistency in outcomes across departments.

The action also undertook to review the Civil Service Competency Framework on the basis of regular skills audits and to develop a technology solution to the co-ordination of skills across the Civil Service. The One Learning Centre designed a civil service-wide skills register that will form part of the technology solution and the path to a learning management system.

Sources: Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (2014[18]), The Civil Service Renewal Plan, www.per.gov.ie/civil-service-renewal; OECD (2017[13]), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264280724-en.

Recommended Action 4: Strengthening inter-ministerial co-ordination

In light of these current arrangements, challenges and good practices, Slovenia can strengthen the culture of inter-ministerial co-ordination (and engagement more generally) in adult learning policy making, by taking the following actions.

Action 4

The government should improve awareness, skills, recognition and resourcing for co-operation in the public administration, to strengthen co-operation within, between and by ministries.

The government should survey the individuals working on adult learning within ministries, agencies and existing cross-sectoral bodies, in order to assess and address gaps in skills, recognition and resourcing for co-operation. In light of the survey results, the government should: raise awareness about the importance of co-operation in adult learning, improve opportunities for developing skills for co-operation in the public administration, strengthen requirements for and recognition of effective co-operation, and resource co-operation efforts effectively. While focused on adult learning, this action should contribute to the achievement of the SRS 2030 goals for “effective governance and high-quality public service”.

This action should build civil servants’ capacity for: strategic governance (Actions 1 and 2), integrating diverse information into decision making (Action 3) and adopting a user-centred approach in adult learning (Action 6). The government should also consider extending learning opportunities to municipalities and public providers to support their role in adult learning (Action 5).

Specifically, the government should:

-

1. Undertake a survey of individuals in ministries, agencies, co-ordination bodies and expert councils involved in adult learning to establish a baseline estimate of: the current resources (people, time and funding) devoted to inter-ministerial co-ordination, stakeholder engagement and expert advice for adult learning policy; and whether the skills and training of staff involved in these co-operation efforts are sufficient.

-

a. In light of the results of this baseline survey, the relevant ministries, agencies, bodies and councils should document good practice for resourcing inter-ministerial co-ordination, stakeholder engagement and expert advice in adult learning, and advise the government on current resource gaps/constraints and how they might be filled. A whole-of-government, cross-sectoral body for adult learning could be responsible for preparing this advice (Action 2).

-

-

2. Raise awareness and promote understanding of:

-

a. The benefits of co-ordination and engagement for adult learning policy – such as minimising overlaps and gaps in adult learning services, increasing the likelihood of successful implementation, better meeting the needs of individual adults, capitalising on the distinct strengths of each sector, facilitating cross-sectoral learning, generating complementarities between related policies – and how these can improve adult learning participation, outcomes and/or cost-effectiveness.

-

b. Good practice examples of co-operation from Slovenia and abroad. For example, from the field of adult learning, cross-sectoral initiatives that include an element of adult skills and learning (e.g. the S4) or related policy fields (such as labour, social or economic policy).

-

-

3. Promote and expand learning and development opportunities for the civil servants involved in adult learning policy, incorporating:

-

a. An initial “learning needs” assessment: this should involve a survey of staff perceptions about whether they have the time, skills, and learning and development opportunities required to effectively engage in inter-ministerial co-ordination and stakeholder engagement in policy making.

-

b. A broad range of skills, such as policy analysis and advice (including user-centred design), managing networks (including skills for inter-ministerial co-ordination, negotiation and conflict resolution), citizen engagement and service delivery (such as co-creation), and commissioning and contracting services (e.g. through public tenders).

-

c. A broad range of methods, such as practice-based, on-the-job and online training; mentoring and coaching; networking; and peer learning and mobility assignments.

-

d. Municipalities: the central government, in consultation with municipalities, should extend this awareness and learning initiative to municipal staff involved in adult learning.

-

e. Existing national and EU funding sources: for example, any available funds for technical assistance and capacity building.

-

-

4. Strengthen individual and team responsibility and recognition for co-operation, by:

-

a. Requiring individuals and teams to co-operate. After evaluating and refining the current Management by Objectives pilot in the MJU, the government should apply this system to the teams and/or individual staff in the central public administration involved in adult learning policy. This system should include specific performance objectives for inter-ministerial co-ordination and stakeholder engagement.

-

b. Recognising individuals and teams for effective co-operation. Effective inter-ministerial co-ordination and stakeholder engagement should be systematically recognised in performance appraisals and become one criterion for promotions. This could remain informal, or formalised in the Decree on Promoting Officials to Titles or the Rules on the Promotion of Public Employees into Salary Grades.

-

Strengthen co-operation with municipalities and between local actors

Effective co-operation with and between actors at the local and regional level is also important for improving participation, outcomes and cost-effectiveness in adult learning (OECD, 2003, p. 221[2]). Effective co-operation between ministries and Slovenia’s 212 municipalities can help the ministries to better tailor policies to local/regional needs, and the municipalities to contribute more effectively to realising national goals for adult learning. Effective co-operation between local and regional actors themselves (municipalities, providers, employers, social partners and others) can help minimise geographical overlaps or gaps in services, facilitate knowledge exchange, reveal opportunities for partnerships that increase quality and/or cost-effectiveness, co-ordinate engagement with central government, and support policy coherence within regions and across sectors (development, social policy, etc.).

Several factors can support effective co-operation with and between actors at the local and regional level. These include clear and shared priorities, goals, targets and responsibilities for adult learning (Action 1); an influential and accountable co-ordination body that includes local/regional representatives (Action 2); and high-quality information to enrich decision-making and co-ordination (Action 3) all covered in Chapter 2. Having the right skills, accountability, recognition and resources for co-operation in the central government (Action 4) can also support ministries’ co-operation with municipalities.

In addition, regional bodies can provide a forum for local and regional actors to identify and pursue opportunities for co-operation. Meanwhile, central government ministries and agencies can support the contributions of local and regional actors to achieving national goals for adult learning through funding design and the recognition and dissemination of good practices.

Current arrangements for co-operation with local actors

Slovenia’s 212 municipalities have an important and growing role in adult learning. The 2007 Local Self-Government Act (Zakon o lokalni samoupravi) stipulates that municipalities should create the conditions to enable adult education to contribute to the development of the municipality and its inhabitants’ quality of life. The new Adult Education Act (Zakon o izobraževanju odraslih [ZIO-1 Act], 2018)) requires municipalities to develop annual plans for adult education (Letni programi izobraževanja odraslih) (Box 3.5).

The municipalities own the premises of Slovenia’s 34 LUs. In 2017, 75 of the 212 municipalities reported spending on adult education to the Ministry of Finance. According to a sample of municipalities’ 2018 budgets, operational expenditure on adult education ranges from EUR 0 in some municipalities to EUR 14 per capita in Črnomelj (Table 4.4 in Chapter 4).

The new ZIO-1 Act (2018) stipulates that municipalities must adopt an Annual Plan for Adult Education (AL Plan). The plans must include:

-

annual targets and indicators

-

priority areas and associated actions

-

the amount of funding from the national/municipal budget to implement the annual programme

-

the actors responsible for implementing the plan

-

information on how the plan’s implementation will be monitored.

The act also allows municipalities to adopt joint AL Plans with other municipalities.

Among the AL Plans that municipalities had created and publicly released by mid-2018, the contents are quite variable. For example:

-

The Municipality of Jesenice’s AL Plan (2018) is one page long and lists three projects (Multigenerational Centre, University of Elders and the Cultural Heritage Project) and municipal financing of EUR 135 100.

-

The Municipality of Ajdovščina’s AL Plan (2017) provides key information about the local LU and description of its six programmes (career counselling and workshops for youth, computer literacy programmes for the elderly and the unemployed, programmes for raising the basic competencies of the population, the centre for intergenerational learning, and training programmes at the Learning Centre in Brje, Urban Garden Learning). The municipality provides co-financing of EUR 35 000.

-

The Municipality of Ljubljana’s AL Plan references EU strategies and the ReNPIO, as well as the Strategy for the Development of Education in the Municipality of Ljubljana (2009-19). The AL Plan describes six programmes, and details their target groups, content, methods of implementation and evaluation, events, timelines, and financing. Two providers – the Cene Štupar LU and the University of the Third Age – are responsible for realising the programme. The municipality provides financing of EUR 85 000 for the plan.

Sources: National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia (2018[19]), Adult Education Act, http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO7641; Annual plan from Jesenice Municipality provided by LU Jesenice (10 May 2018); Municipality of Ajdovščina (2017[20]), Annual Plan for Adult Education in the Municipality of Ajdovščina 2018, www.ajdovscina.si/mma/Letni%20program%20izobrazevanja%20odraslih%20v%20obcini%20Ajdovscina%202018.pdf/2017121511300549/?m=1513333803; Annual plan from Ljubljana Municipality provided by LU Cene Štupar (5 October 2018).

Co-operation between ministries and municipalities

The ministries involved in adult learning and Slovenia’s 212 municipalities interact through various, mainly indirect, mechanisms. These include:

-

The e-Democracy online portal: the portal gives all sectors, including municipalities, 30 days to comment on all legislative proposals.

-

Municipal associations: the Local Self-Government Act established associations to represent municipalities’ interests in national policy development, and requires the government to consult these associations on policies of relevance to municipalities. There are currently three associations in Slovenia: the Association of Municipalities and Towns of Slovenia (Skupnost občin) (SOS), the Association of Municipalities of Slovenia (Združenje občin Slovenije) (ZOS) and the Association of City Municipalities of Slovenia (Združenje mestnih občin Slovenije) (ZMOS).

-

The AE Body: one municipal association, the SOS, is currently a member (municipalities are not represented in the SSIO).

-

The National Council: Slovenia’s upper parliamentary chamber (the National Council) includes 22 representatives of local interests.

-

The Local Self-Government Service at the MJU: the MJU’s responsibilities include the system of local self-government in Slovenia. It co-operates with the municipal associations, and provides professional assistance to municipalities to help them comply with and implement regulations.

-

Regional development agencies (Regionalne razvojne agencije) (RRAs)): although Slovenia does not have a regional level of government, it does have 12 RRAs that seek balanced development across regions (OECD, 2016[21]). Each RRA has established a Committee for Human Resources. Each RRA prepares a Regional Development Plan (Regionalni razvojni program) (RRP), and 11 out of the 12 RRPs include goals/targets for adult learning (see Box 3.7 for one example). RRAs are required to submit their RRPs to the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology (Ministrstvo za gospodarski razvoj in tehnologijo) (MGRT), and both are required to ensure alignment of the RRPs with the SRS 2030 and other national policies.

-

Regional adult learning service providers: the ministries involved in adult learning also engage with local actors indirectly via their own agencies. Providers of adult learning services such as LUs (MIZŠ), MICs (MIZŠ), KOCs (MDDSZ) and Employment Service Offices “represent” and implement the central government’s priorities and policies at the local/regional level. They also “represent” and convey local/regional level needs in national forums such as working groups for legislative development, and the AE Body.

The development of the new ZIO-1 Act provides a recent example of how some of these mechanisms are utilised in adult learning policy making (Box 3.6).

In 2016, the Minister of Education, Science and Sports formed a working group to prepare a new ZIO Act. The working group operated from December 2016 to May 2017 and held six co-ordination meetings, presented the draft act in various forums and published the act on the e-Democracy portal for public comment.

The MIZŠ and municipalities engaged in various ways during this process, including:

-

the MIZŠ held co-ordination meetings for the preparation of the new law with municipal representatives from the Dolenjska region (individual municipalities), the SOS, ZOS and head of the Local Self-Government Service at the MJU

-

the AE Body, which includes SOS, discussed the proposal

-

all three municipal associations provided comments on the act on the e-Democracy online portal

-

in December 2017, the National Council (which includes 22 municipal representatives) assented to the act, and stated that adult education requires an integrated approach from all ministries.

Source: MIZŠ (2017[22]), Proposal of the Adult Education Act, http://vrs-3.vlada.si/MANDAT14/VLADNAGRADIVA.NSF/18a6b9887c33a0bdc12570e50034eb54/7844fac71ebd3f17c12581c500210d44/$FILE/ZIO_vlgr_25_10_17.pdf.

Co-operation between local actors

Municipalities and the other local and regional actors involved in adult learning (providers, social partners and others) can potentially co-operate with each other through the mechanisms described above. These include:

-

Regional adult learning service providers: providers of adult learning services – LUs, MICs, KOCs, etc. – also serve as co-ordination points for local and regional adult learning activities. Lifelong learning centres (Centri vseživljenjskega učenja) previously played this role in the period 2008 to 2013.

-

RRAs: the Committees for Human Resources comprise regional representatives of LUs, secondary schools, business chambers, NGOs, and the Employment Service of Slovenia (Zavod Republike Slovenije za zaposlovanje) (ZRSZ), all of whom are stakeholders in adult learning.

-

Regional networks: Slovenia’s 12 Councils of Regions (Svet regij), each of which comprises mayors from within the region, allow mayors to share information and identify opportunities for co-operation, including in adult learning.

-

Municipal associations: Slovenia’s municipal associations implement joint development projects, and organise seminars, workshops, conferences and working meetings on priority issues facing municipalities, which could include inter-municipal co-ordination in adult learning.

-

Professional associations: Slovenia’s five professional associations of adult education providers could potentially facilitate partnerships, consortiums and other forms of co-operation between providers.

The Promotion of Balanced Regional Development Act (2011) established RRPs to guide regional development. RRAs design the RRPs, and the MGRT is responsible for ensuring that the regional plans are coherent with the national development strategy and other national strategies. Eleven of Slovenia’s 12 RRPs include adult learning-related priorities and targets.

As an example, the RRP of the Primorsko-notranjska region describes objectives, indicators, activities and projects for adult learning.

The RRP’s analysis of human resource development identifies:

-

Strengths: the growing participation of adults in lifelong learning, and support services for counselling, entrepreneurship development, education and training.

-

Weaknesses: the decreasing number of lifelong learning programmes, and misalignment with employers’ needs.

-

Opportunities: identifying labour market needs, adapting education programmes to the needs of the regional economy, strengthening co-operation between employers and others, and integrating the concept of sustainable development into education programmes.

-

Threats: late adaptation of education and training programmes to the needs of the economy, and limited interest in technical or other professions needed by economy.

The RRP has an objective to promote participation in learning and the labour market, and sets numerical targets for adult learning participation, the number of providers and the number of programmes in the region. To realise these targets, the RRP plans numerous activities, such as creating dialogue between regional stakeholders in adult learning, including stakeholders when anticipating skills needs, updating curricula and practical training, and promoting flexible learning pathways. The RRP allocated EUR 4 million to implement these activities, some of which went to the Postojna MIC and the Career Centre at the Ilirska Bistrica Centre for Social Work.

The Committee for Human Resources and Social Development overseeing these aspects of the RRA included nine representatives in total, from the municipality, the ZRSZ, the Centre for Social Work, a regional network of NGOs, the region’s LU, the region’s School Centre, the Pensioners’ Association and a company.

The Regional Council of Mayors monitors the achievement of the RRP, adopting the annual and final report on implementation.

Sources: RRA Notranjsko-kraške regije (2015[23]), Regional Development Programme of Primorsko-notranjska region, www.rra-zk.si/materiali/priloge/slo/rrp-nkr-2014-2020-s-popravki_april-2015.pdf; National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia (2011[24]), Promotion of Balanced Regional Development Act, www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO5801; National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia (2012[25]), Decree on Regional Development Programmes, http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=URED6106.

Opportunities to improve co-operation with local actors

There are opportunities to improve co-ordination and co-operation both between central government and municipalities, and within and between actors at the regional and local level.

Co-operation between ministries and municipalities

Despite the important and growing role of municipalities in adult learning, there is limited co-ordination and co-operation between ministries and municipalities for developing and implementing adult learning policy.

Ministries could engage more effectively with municipalities during the design and drafting of adult learning-related legislation and policy. Representatives of the ministries participating in the National Skills Strategy Action Phase cited no direct lines of communication with municipalities. The SOS is the only municipal association involved in any of the national cross-sectoral bodies for adult learning (the AE Body, SSIO and SSPSI; see Chapter 2). Neither municipalities nor their associations were involved in the development of the ReNPIO (see Chapter 2). Ministries and municipalities did interact in various ways during the development of the 2018 ZIO-1 Act (Box 3.6). However, some municipal representatives, such as the ZMOS, were not included in the MIZŠ’ direct engagement, and have been critical of the process.

The central government is not making full use of municipalities’ insights about local/regional needs, and the challenges and opportunities municipalities face in implementing national adult learning laws/policies locally.

The ReNPIO and the municipal AL Plans could be more closely connected. The ReNPIO does not articulate the role of municipalities in contributing to the achievement of its goals and targets. By mid-2018, many municipalities still did not have an AL Plan. The existing AL Plans are highly variable in their level of detail and their coherence with the ReNPIO. Most of the AL Plans that are publicly available describe their local LU and co-financed projects. With a few exceptions (e.g. the Municipality of Ljubljana) they do not include the other elements required in the ZIO-1 Act: annual targets and indicators, priority areas and associated actions, specifying the actors responsible for implementation, and how implementation will be monitored. The MIZŠ needs an effective process to monitor and enforce the implementation of the AL Plans.

Co-operation between ministries and municipalities is challenging because of the large number of municipalities and their limited engagement capacity. Slovenia has 10.3 municipalities per 100 000 inhabitants, which is higher than in most unitary countries including Latvia (6.1), Estonia (6.0) and Ireland (0.7) (OECD, 2018[26]). Municipalities, especially smaller ones, may simply lack the human resources required to directly engage with ministries. Some municipalities have a social policy officer in charge of educational and social programmes and expenditure. However, some representatives of municipalities involved in this project stated that, because these roles are quite broad, these officers have limited capacity to engage with specific national policies. Some social policy officers consulted during this project were not aware of the ZIO-1 Act until after its enactment.

Despite these challenges, effective co-operation between ministries and representatives of municipalities will be essential if Slovenia is to effectively tailor its national policies to local/regional needs, and if municipalities are to help realise national goals for adult learning.

Co-operation between local actors

Several stakeholders participating in the National Skills Strategy Action Phase stated that co-operation between actors at the local level is a strong point of Slovenia’s adult learning system. Regional adult learning-related centres (LUs, MICs, KOCs, etc.) do act as hubs for co-operation between providers, municipalities, local employers, social partners and others. MICs, for example, connect learners of different ages and education levels, researchers, mentors, local companies, chambers and their local communities (for an example, see Box 3.11). However, participating stakeholders considered that local and regional co-operation in adult learning could be made more systematic, in order to harness the resources, knowledge and capacity of multiple municipalities and stakeholders.

No municipalities have availed themselves of the option to develop joint AL Plans with other municipalities under the 2018 ZIO-1 Act. Slovenia’s Education White Paper (Krek and Metljak, 2011[10]) specifically identified the need for regional strategies and annual plans for adult learning.

Municipalities lack a culture of co-operation and of joint service provision, and there are few examples of municipalities entering into partnerships with each other for adult learning. Indeed, some representatives of municipalities participating in this project stated that municipalities typically consider that the costs and complexity of inter-municipal partnerships outweigh the benefits. The perceived and objective reasons for this need to be better understood and overcome if partnerships are to become more systematic.

Municipalities and local stakeholders are often unaware of the potential for, or successful examples of local and regional partnerships in adult learning. While the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education (Andragoški center Republike Slovenije) (ACS) has an established awards programme for success stories and good practice in adult learning, this does not currently focus on local and regional partnerships. There is a need for greater recognition of successful local and regional partnerships in adult learning (as in Jesenice, Box 3.10) and dissemination of these examples to inspire local and regional co-operation.

The RRAs and Regional Councils of Mayors do not appear to be facilitating regional partnerships for adult learning. This partly reflects the fact that their remits are much wider than adult learning. Adult learning does not appear to be high on the agenda of the Regional Councils of Mayors. Slovenia’s LLL Strategy cited the need for regional authorities to co-fund LLL services (Jelenc, 2007[9]), while Slovenia’s Education White Paper (Krek and Metljak, 2011[10]) identified the need for municipal and/or inter-municipal management structures for adult learning.

Although public funding for adult learning in Slovenia is almost entirely tender-based, ministries are not using tenders to spur local or regional co-operation. Currently, national tenders do not include a standard clause to prioritise or otherwise reward partnerships between providers, municipalities, employers or social partners at the local or regional levels.

Previous strategies and studies have made recommendations to improve co-operation between the central and municipal governments, and between local actors for adult learning (Box 3.8).

White Paper on Education in the Republic of Slovenia (2011)

The white paper recommended:

-

Adult education should be defined as the original obligation of the regions. It is also necessary to define regional management structures that will develop and monitor the field of adult education.

-

Municipal and inter-municipal management structures should be responsible for providing access to general non-formal education, implementing national adult education policy, meeting the learning needs of local adults. They should create strategies for developing adult education, and annual adult education plans.

Access of Adults to Formal and Non‐Formal Education – Policies and Priorities (2010)

This study focused on the contribution of Slovenia’s education system to the process of making lifelong learning a reality, and its role as a potential agency of social integration. It recommended that, because of its close links with the community, adult education and learning should be linked more strongly to the regional and municipal level, accompanied by adequate funds to enable the realisation of development plans.

Lifelong Learning Strategy of Slovenia (2007)

The LLL Strategy set 14 objectives, one of which was to “facilitate implementation and use of knowledge, skills and learning as the fundamental source and driving force for the development of local and regional areas as well as development of social networks within them”. To achieve this objective, the strategy recommended that:

-

LLL must become an integral part of local and regional policies and programmes, and local and regional authorities must co-fund LLL services.

-

Local communities must provide infrastructure to make LLL accessible (e.g. day-care services and suitable transport).

-

Different partners should help implement LLL at the local levels (e.g. enterprises, chambers, employment service, non-governmental, development, educational and other organisations).

-

Public, private, volunteer and other organisations involved in LLL should plan partnerships in local communities in pursuit of efficiency gains. To this end, Centres for Lifelong Learning could be established in legislation and act as umbrella networks, attracting all key regional partners into their management.

Sources: Krek and Metljak (2011[10]), Education White Paper of the Republic of Slovenia, http://pefprints.pef.uni-lj.si/1195/; Ivančič, Špolar and Radovan (2010[27]), Access of Adults to Formal and Non-Formal Education – Policies and Priorities: The Case of Slovenia, http://www.dcu.ie/sites/default/files/edc/pdf/sloveniasp5.pdf; Jelenc (2007[9]), Lifelong Learning Strategy in Slovenia, http://www.mss.gov.si/fileadmin/mss.gov.si/pageuploads/podrocje/razvoj_solstva/IU2010/Strategija_VZU.pdf.

Examples of good practice co-operation with local actors

There are good practice examples in OECD countries and in Slovenia of processes to facilitate co-operation for adult learning between the central and subnational level of government, and between local actors.

Co-operation between ministries and municipalities

In the Netherlands, adult learning is co-ordinated through Regional Education Centres. The centres aim to increase overall access to adult learning opportunities, and achieve the central government’s goal of increasing the educational attainment of minority and underprivileged groups. Through these centres, municipalities are responsible for providing education which will meet the demands of their communities, including vulnerable groups. State funding is allotted to municipalities on the basis of the number of adults, including vulnerable adults in the municipality. The municipalities then have the autonomy to sign contracts on the basis of need with local providers for adult education through the Regional Education Centres (Desjardins, 2017[28]).

In Lithuania, municipalities have major responsibilities for implementing adult learning policy. They are accountable to central government and receive support from it (Box 3.9).

In Lithuania, both the central government and the 60 municipal governments participate in shaping and implementing adult education policy. Two types of municipal institutions are involved in implementing national policy for adult learning at the local level:

-

Municipal councils comprise elected officials, including the local mayor. With respect to adult learning, councils set out long-term objectives and measures, confirm municipal action plans, appoint a co-ordinator to implement the action plans, and develop a network of providers catering to local needs.

-

Administrative municipal institutions analyse the state of adult education, ensure that national policy is implemented, co-ordinate action plans for adult learning, organise learning and guidance services, and provide information to the Ministry of Education and Science and the public about the state of adult education in the municipality.

Research in Lithuania found that implementation of adult education policy was weakest at the municipal level of government. It also found that local leaders sometimes lacked general knowledge on adult education, as well as skills for strategic education planning, research and inter-institutional communication. In response, the new Law on Non-formal Adult Education and Continuous Learning established co-ordinators of non-formal adult education and continuous learning, and the central government implemented a range of projects to build awareness of and capacity for adult learning policy at the local level. These projects included:

-

1. a cycle of seminars for representatives of regional and local authorities and social partners on strategic planning of adult education and inter-institutional co-operation

-

2. a cycle of practical training carried out for municipality adult education co-ordinators

-

3. non-formal adult education support provided for adult education co-ordinators at municipalities

-

4. a conference held to assess progress in adult education policy and regional results, and to discuss activities to be continued

-

5. participation in international events relating to the implementation of the European agenda for adult learning.

Sources: Eurydice (2018[29]), Lithuania: Organisation and Governance, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/organisation-and-governance-44_en; Republic of Lithuania (2011[30]), Law Amending the Law on Education, https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.407836; European Commission (2015[31]), National Co-ordinators for the Implementation of the European Agenda for Adult Learning, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/sites/eacea-site/files/call_11_2015_compendium_al_agenda.pdf.

Co-operation between local actors

In the municipality of Jesenice in north-west Slovenia, the LU, municipal government, local employers and the local small-business chamber co-operate to design, deliver and finance adult learning services tailored to local needs (Box 3.10).

The LU of Jesenice has established several partnerships with stakeholders and municipalities (Jesenice, Kranjska Gora, Žirovnica and Bohinj) within its region. This has involved co-designing programmes with local employers and associations, co-funding several programmes with the local municipality, and tendering for ESF funding as a consortium or in partnership.

From 2016 to 2018, the LU has co-designed (and delivered) tailored ICT, language and communication training with 17 local employers, in a number of sectors:

-

the health sector: including with the Regional Hospital Jesenice, Health Centre Jesenice, Retirement Home Franceta Berglja Jesenice, Retirement Home Viharnik Kranjska Gora

-

the tourism sector: including with HIT Alpinea Kranjska Gora, Vogel Ski Centre Bohinj

-

the public sector: including with the Municipality of Jesenice.

The centre has successfully applied for several EU and national tenders in partnership with other adult education providers, municipalities, retirement homes, pensioners’ associations and youth organisation in Gorenjska region. The successful projects include counselling and assessing knowledge of employees (Svetovanje in vrednotenje znanja zaposlenih), acquisition of basic and professional competencies of employees (Pridobivanje temeljnih in poklicnih kompetenc zaposlenih), Multigenerational Centre of Gorenjska (Večgeneracijski center Gorenjske), Norway Financial Mechanism Programme “Fit and healthy towards old age!” (Čili in zdravi starosti naproti!), and Erasmus+ “Chain Experiment” (Verižni eksperiment).

The municipal government of Jesenice and the LU co-finance several programmes. The municipality budgeted EUR 135 100 for adult education expenditure for 2018 (Table 4.4 in Chapter 4). It co-finances several of the centre’s projects that address local learning needs, such as an Albanian-speaking guidance counsellor to support access to language education and other forms of training for members of this community.

Local actors report that effective adult learning partnerships in the Jesenice municipality have yielded several benefits in the local area, contributing to:

-

Improved quality of adult learning services, ensuring they are tailored to the needs of local employers, workers and other adults. For example, three language courses (Italian, German and Slovene) adapted to the needs of tourism workers in Kranjska Gora, communication courses adapted to the needs of technical staff in the local hospital, and Slovene language courses for Albanian women.

-

Greater success in accessing EU tenders (e.g. counselling and assessing knowledge of employees).

-

Increased supply of free adult learning services for adults (e.g. Multigenerational Centre in 2017), increasing participation.

Sources: MIZŠ (2013[32]), Jesenice LU, http://lu-jesenice.net/; OECD visit to Ljudska univerza Jesenice (15 May 2018); information provided by the Director of Ljudska univerza Jesenice (8 August 2018).

The MIC in Velenje serves as a hub for adults and businesses from the local and neighbouring municipalities to undertake technology-oriented training and projects (Box 3.11).

The MIC in Velenje is a centre of excellence in modern technologies that combines general, professional and practical knowledge in various forms of education. It has 43 specialised classrooms equipped with technical laboratories for electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, mechatronics and robotics. At the MIC students, adults and researchers work with 55 trained mentors to undertake practical training and projects, and develop prototypes. The MIC is a unit of the Velenje School Centre (ŠC Velenje), which consists of 5 secondary schools and the higher vocational school. During the 2017/18 school year, the entire ŠC Velenje offered 25 secondary and 6 post-secondary professional programmes for 2 517 students, including 500 adults.

The MIC places special emphasis on partnering with local businesses of all sizes (such as Gorenje and Premogovnik Velenje), business chambers and the local community. It serves the local and neighbouring municipalities and regions, such as Savinjska and Koroška. The MIC’s vision includes being:

-

a regional centre for lifelong learning offering functional training in computer science and modern ICT; validation of non-formal and informal learning; courses and seminars in automation, hydraulics, computer numerical control technology, mechatronics and explosion protection; master craftsman exams; and foreign language courses

-

a partner in a regional entrepreneurial incubator: MIC participates in the transfer of educational and research activities into entrepreneurial practices, and actively connects with businesses in the transfer of knowledge and technologies.

Source: Velenje School Centre (2017[33]), Inter-Company Training Centre Velenje, http://mic.scv.si/.

Denmark and Germany have taken a systematic approach to facilitating regional partnerships in adult learning (Box 3.12).

Germany’s Learning Regions – Promotion of Networks programme

This German national policy was in place between 2001 and 2008, and funded the creation of regional networks designed to build linkages between employers, formal and non-formal education, and training providers. These regions were to implement the national policy priorities for lifelong learning from the bottom up. The programme aimed to create Learning Regions that would in time become self-sustaining without government funding, which was gradually phased out to encourage the sourcing of alternate funding. From 2009, the programme was succeeded by the Learning in Place programme, which focused more heavily on public-private partnerships for funding.

Evaluations of the regional networks showed that they were most successful when they connected and were coherent with other policies, such as reducing unemployment, as this gave them increased relevance and access to resources. Evaluation showed these networks to be effective in improving regional education markets by increasing transparency and therefore allowing supply and demand to be closer to market needs.

The Bad Tolz region is an example of a successful network that continued after national funding stopped. It continued to function in two areas, co-ordinating for-profit events that generate revenue, and providing services and information to the community, such as the Learning Festival and the Family Compass family support initiative. The network is governed by a board that successfully co-ordinated private partnerships to fund these community services.

Denmark’s VEU (Voksen- og EfterUddannelse) Centres

VEU Centres are regional networks of adult education and training institutions, providing a hub for both education and training, and guidance to employers and individuals. Denmark’s 13 VEU Centres are largely self-governing but renegotiate their budget with government yearly through local authorities. They do so by entering a development contract with the Ministry of Education that specifies their shared goals and the targets they will achieve in exchange for government funding. This encourages co-operation between the centres and providers to meet common targets in order to ensure and increase the state funding.

A tripartite agreement on lifelong learning between the government and social partners in 2017 emphasised their role as a “one-stop shop” for accessing education and training. Simplified learning pathways make them the single point of entry for vocational education and training (VET), a user-centred approach that aims to simplify access to learning for individuals. The VEU Centres are believed to have contributed to more effective and efficient delivery of adult learning in Denmark, having helped to reduce gaps in participation across the country’s different regions.

Sources: European Commission (2015[34]), An In-Depth Analysis of Adult Learning Policies and their Effectiveness in Europe, https://doi.org/10.2767/076649; Desjardins (2017[28]), Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems: Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies and Constraints; European Commission (2017[35]), Education and Training Monitor 2017: Denmark, https://doi.org/10.2766/16554; Reghenzani-Kearns and Kearns (2012[36]), “Lifelong learning in German learning cities/regions”, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1000173.pdf; Thinesse-Demel (2009[37]), “Background report: Germany (regional report)”, www.learning-regions.net/images/stories/rokbox/background_report_germany_regional.pdf.

Recommended Action 5: Strengthening co-ordination with local actors

In light of these current arrangements, challenges and good practices, Slovenia should strengthen co-operation between ministries and municipalities, and between local and regional actors themselves, by taking the following actions.

Action 5

The central government and municipalities should co-ordinate more effectively to ensure coherence between national and local adult learning policies and programmes. Municipalities and other local actors should strengthen their co-operation to improve the relevance, impact and cost-effectiveness of adult learning services.

Municipalities and regional development agencies should actively contribute to Actions 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8, and ensure that their plans and activities are aligned with the national master plan (Action 1). Furthermore, municipalities, regional development agencies and service providers should use regional processes (such as Regional Councils of Mayors and RRAs) to identify and realise opportunities for partnerships in adult learning.

In addition to including local and regional stakeholders in Actions 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8, ministries should use public tenders to reward local and regional partnerships, and the ACS should recognise and widely publicise successful examples of such partnerships.

More specifically:

-

1. To improve co-operation between ministries and municipalities:

-

a. Ministries of the central government should:

-

i. include representatives of municipalities and regions in Actions 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8, and consider extending co-operation-oriented training opportunities to municipal staff responsible for adult learning (see Action 4)

-

ii. invite representatives of Slovenia’s Municipal Associations, Regional Councils of Mayors and/or RRAs to join the expanded AE Body (Action 2)

-

iii. develop ways to more proactively and directly reach out to municipalities to keep them well informed about developments in national adult learning policy, including proposals to amend or enact legislation

-

iv. monitor the implementation and impacts of new provisions for municipalities in the ZIO-1 Act (2018), including for municipal annual plans for adult education.

-

-

b. Municipalities and regional development agencies should:

-

i. actively contribute to Actions 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8

-

ii. ensure that their plans and activities are aligned with the national master plan (Action 1). Specifically, municipalities and RRAs should review, discuss and update their Annual Plans for Adult Learning and RRPs respectively, to ensure they contribute to achieving the goals of the next adult learning master plan (Action 1).

-

-

-

2. To improve co-operation in adult learning at the subnational level, between local and regional actors:

-

a. Local and regional actors (municipalities, providers, employers, social partners, non-government organisations and others) should raise the profile of adult learning in existing regional bodies such as Regional Councils of Mayors and/or RRAs, or develop a new regional body for adult learning. The selected body should identify and realise opportunities for partnerships (co-design, co-funding and/or co-delivery) to improve participation, outcomes and/or cost-effectiveness in adult learning.

-

b. Municipalities should pilot joint municipal annual plans for adult education, underpinned by joint funding, to harness the resources, expertise and networks of multiple municipalities, and facilitate inter-municipal capacity building.

-

c. The central government should use public tenders to reward and encourage local and regional partnerships in the delivery of adult learning services, for example by making partnerships one criterion for selecting providers.

-

d. The ACS, in consultation with the Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Vocational Education and Training (Center Republike Slovenije za poklicno izobraževanje) (CPI) and other relevant bodies, should identify, publicly recognise and disseminate examples of successful local and regional partnerships in delivering adult learning.

-

Strengthen government engagement with stakeholders for adult learning

Effective co-operation between government (ministries and agencies) and publicly funded providers on the one hand, and stakeholders on the other, is essential for improving participation, outcomes and cost-effectiveness in adult learning. This involves effective government engagement with stakeholders in the adult learning policy-making process. It also involves providers engaging with stakeholders to co-design, co-deliver and/or co-fund adult learning services, and ensuring services are tailored to users’ needs.

Complex, multi-dimensional policy challenges like adult learning increasingly require civil servants to work directly with citizens and service users, leveraging the “wisdom of the crowd” to co-create better solutions that take into account service users’ needs and limitations (OECD, 2017[13]). Engaging end users in the design of adult learning services can help ensure services meet their needs.

Several factors can support effective co-operation between government actors and stakeholders. Some of these factors are the focus of Actions 1-3 (Chapter 2) including involving stakeholders in establishing a master plan for adult learning (Action 1), an improved co-ordination body (Action 2), and generating and using high-quality information on learning and skills needs (Action 3). Appropriate skills, accountability, recognition and resources for co-operation within central government can also support ministries’ co-operation with stakeholders (see Action 4). In addition, government actors must actively monitor the extent to which adult learning services meet the diverse needs of adults, and systematically employ a “user-centred” approach to designing adult learning policies and services.

Current arrangements for engaging stakeholders in adult learning

Many diverse government actors and stakeholders have a role in Slovenia’s adult learning system. At least 9 ministries fund adult learning services, while many public institutions deliver adult learning: 34 LUs, 28 public higher vocational colleges, 3 public universities and 1 public higher education institution. Private providers of adult learning include 20 private higher vocational colleges, 1 private university and 49 private higher education institutions, as well as 192 special adult education institutions, 32 parts of enterprises, 7 employer associations’ educational centres, and 201 NGOs. Other important stakeholders include individual adult learners, 5 professional associations of adult education providers, individual employers, 5 major inter-sectoral employer associations (and smaller associations), 49 trade unions, community organisations and researchers.

The SRS 2030 and SJU 2020 have set effective government engagement with stakeholders in policy and programme design as a strategic priority (Box 3.13).

Slovenia has made effective stakeholder engagement and a user-centred approach to designing and delivering public services a strategic priority in the SRS 2030 and SJU 2020.

The SRS 2030 pinpoints the working methods of the public sector as “the key to increasing trust among citizens”, and states that “public policy must foresee and respond effectively and above all more quickly to changes and challenges and thus provide high-quality services for citizens…” The SRS 2030 states that Slovenia will achieve its goal of “Effective governance and high-quality public service” by, among other things:

-

the consistent inclusion of stakeholders at all levels of developing and monitoring policy

-

strengthening co-operation and the assumption of responsibility among partners in the social dialogue

-

designing user-friendly, accessible, transparent and efficient public services in an inclusive manner with the relevant stakeholders.

The SJU 2020 envisions the decisions and activities of the public administration being based on the expected benefits to and needs of end users. It states that a fundamental change in thinking will be required, based on the awareness that the administration serves its users. The vision of the SJU 2020 is based on several principles and values, including “responsiveness and user-orientation”. In order to achieve the vision, the key strategic goals of SJU 2020 include “responsive, effective and efficient operation of user-oriented public administration” and “improving legislation, reducing legislative burdens, assessing impacts, and including key stakeholders”.

Sources: Šooš et al. (2017[3]), Slovenian Development Strategy 2030, www.vlada.si/fileadmin/dokumenti/si/projekti/2017/srs2030/en/Slovenia_2030.pdf; MJU (2015[5]), Public administration 2020. Public Administration Development Strategy 2015-2020, www.mju.gov.si/fileadmin/mju.gov.si/pageuploads/JAVNA_UPRAVA/Kakovost/Strategija_razvoja_JU_2015-2020/Strategija_razvoja_ANG_final_web.pdf.