Chapter 2. The expansion of the financing for sustainable development system: More actors and resources

The sustainable development finance system has profoundly changed in recent years, with a greatly expanded number of actors. The expansion raises questions about the distribution of the roles and calls for a new mapping of contributions.

This chapter presents snapshots of the sustainable development finance landscape by presenting the volumes provided by different actors – external, domestic, public and private – and the repartition of different sources over time. A more granular picture is given about the different roles of actors and their resources. The chapter further examines the impact of the financial and economic shifts of recent years on these types of finance, with emphasis on the historical context and each financing type’s particular niche.

In brief

The Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) widens traditional definitions of development finance, outlining responsibilities and actions for domestic, international, private and public actors. The potential scope of resources available to finance sustainable development is greatly expanded.

Developing country governments and their resources are the central pillar of the financing for sustainable development landscape. But there is a clear need for more revenue.

-

In 2016, tax revenues amounted to USD 4.3 trillion, more than twice the volume of cross-border flows.

-

But the tax revenue-to-GDP ratios in low-income and least developed countries average 14% and in many cases are far below the 15% threshold recommended as necessary for effective state functioning.

Domestic investment makes up a substantial proportion of most countries’ GDP, but due to tighter financing conditions private investment appears to be in sharp decline.

-

Excluding the People’s Republic of China (“China”), domestic mergers and acquisitions declined by over 60% between 2010 and 2017, falling from USD 237 billion to USD 95 billion.

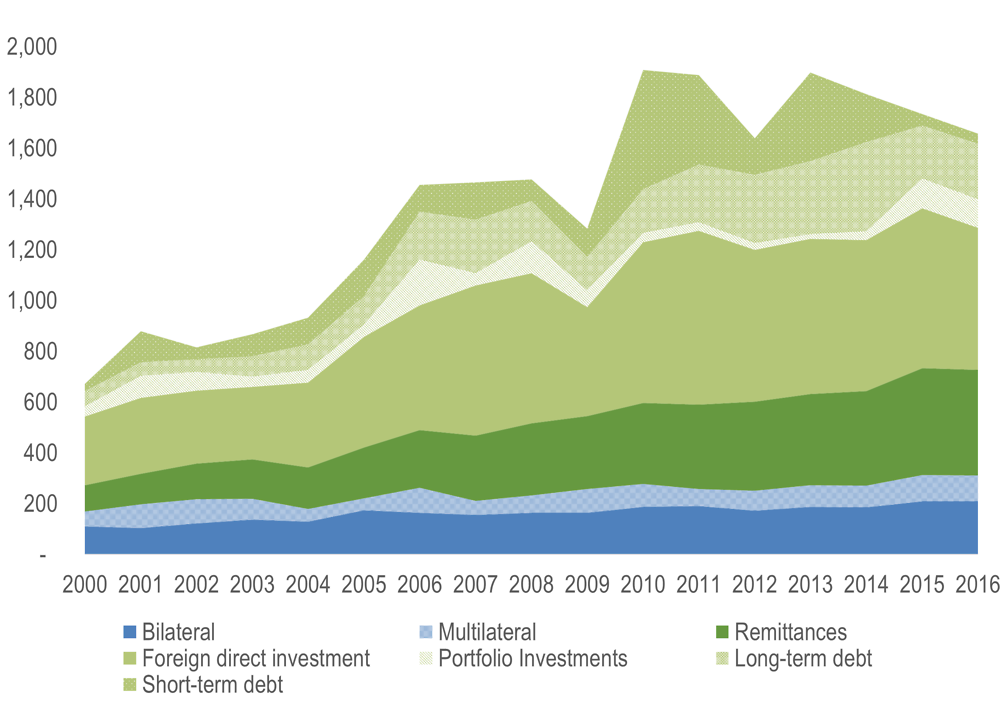

Substantial amounts of cross-border finance already flow to developing countries, amounting to a total of USD 1.7 trillion in 2016.

Private sector actors provide the bulk of cross-border finance, but these flows show an alarming decline.

-

Commercial investors are the single largest provider, with USD 890 billion in FDI, portfolio investment and long-term debt in 2016.

-

Developing countries have foregone between USD 400 and 450 billion of FDI from 2012-2016. In addition to the substantial decline in financing, this can mean fewer opportunities to access international markets and technical know-how.

Developing country emigrants provide remittances, the second largest and the most stable source of external financing for sustainable development.

-

Remitters sent USD 466 billion in 2017 and in some smaller economies these flows make up close to or more than 30% of national GDP, the latter being the case in Kyrgyzstan.

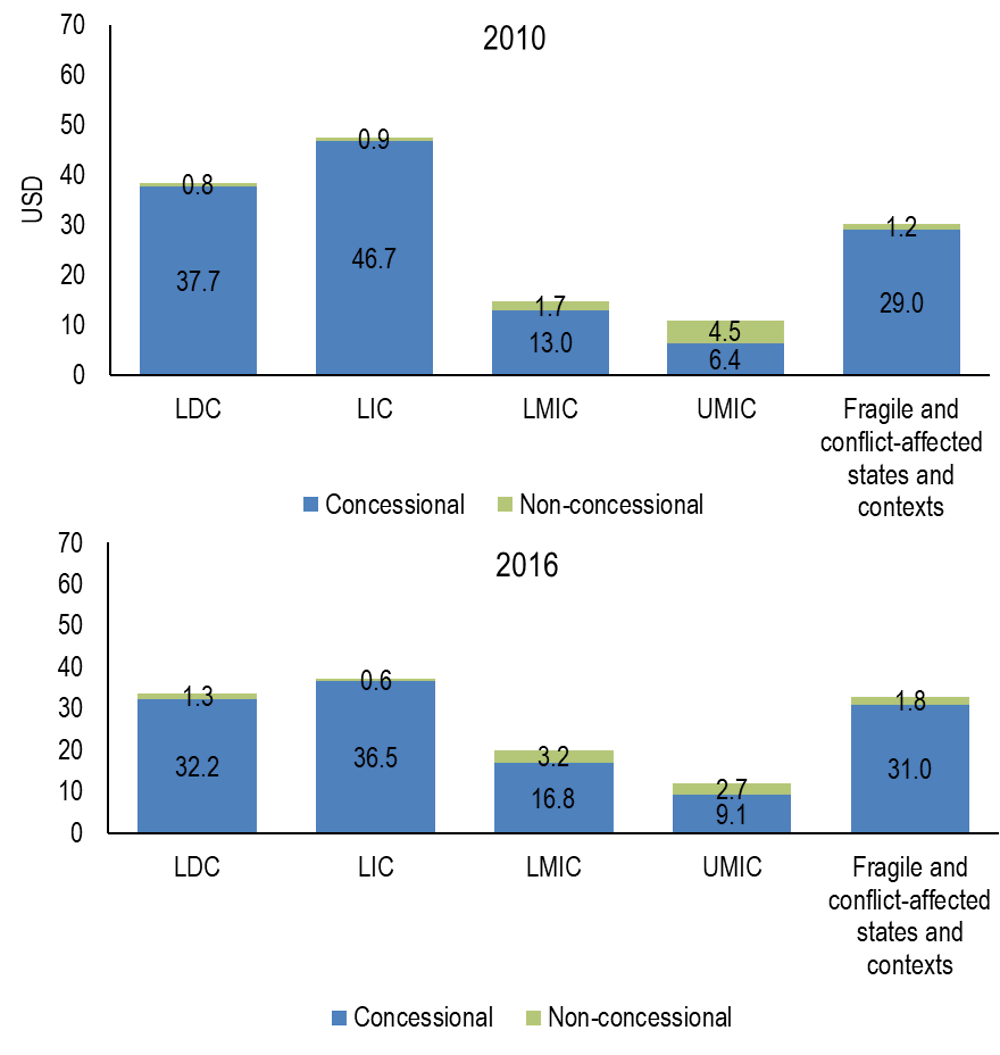

Public sector, i.e. official, providers deploy substantial resources and can play a special role in targeting the most vulnerable countries.

-

Bilateral and multilateral providers deployed USD 311 billion in 2016. Since 2000, financing provided at concessional terms grew most rapidly for the group of low-income countries and fragile and conflict-affected countries.

Philanthropic foundations are key players in the health sector and sometimes pioneer innovative financing solutions, but they have provided smaller volumes than other providers.

-

Of the USD 8 billion of philanthropic giving that flowed into developing countries per year from 2013-2015, an average USD 3.21 billion or 40% of the total targeted the health sector.

Financing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing countries can only be successful if these different contributions are fully understood and exploited. Although the sum of available resources holds great promise to meet the financing needs of the 2030 Agenda, they are not yet sufficiently oriented towards development goals – and, indeed, bringing together this diverse set of actors with different motivations is an enormous challenge in itself.

Data constraints, for example regarding actors in developing countries, make it difficult to fully take in the total picture.

-

One example of such constraints is that estimates on the amounts of concessional finance provided by China in a year range from USD 3 billion to USD 7 billion.

-

Another example is that while domestic public expenditure and private investment are important drivers of financing for development, data on their volumes and uses are extremely limited.

A further challenge is that the SDGs and the AAAA reflect commitments by countries that are made in the name of non-state, third parties who also have important roles in financing for sustainable development. Decisions regarding some of the largest pools of resources – cross-border investments and remittances – are based on private actors’ considerations that are not primarily motivated by the SDGs. A key challenge, then, is to identify win-win opportunities that meet the motives of such private actors and contribute to the achievement of the SDGs at the same time.

Domestic sources of financing and internal drivers

The AAAA underscores that every country has primary responsibility for its own economic and social development (paragraph 9). The ultimate aim of development finance efforts is to achieve a sustainable development finance system that is based on well-functioning and effective domestic mechanisms and integrated into the global system. Effective and efficient tax systems, public financial management systems, governance, and vibrant and resilient markets all play key roles.

While it is the primary role of domestic actors in developing countries to ensure that these internal drivers and domestic resources function properly, the international community and external resources (flows) could support their efforts. The domestic and international spheres are highly interconnected in areas such as taxation and the financial system, highlighting the importance of the international environment and policy framework to support an individual country’s efforts.

Domestic public sector

The domestic public sector’s resources affect the Sustainable Development Goals

Governments have the primary responsibility for implementation of the 2030 Agenda, through direct financing and setting the regulatory environment for foreign and domestic private investment.

Tax revenues are the largest source of finance, exceeding the volumes of any single cross-border resource. In 2016, tax revenues in developing countries amounted to USD 4.3 trillion. The share of tax revenues in the overall finance mix varied from 42.7% in least developed countries and 42.4% in low-income countries to 62.2% in lower middle-income countries and 78.2% in upper middle-income countries.

Greater public resources are associated with greater spending on SDGs such as health (SDG 3) and education (SDG 4).1 Domestic public resources can help tackle inequality (SDG 10) by redistributing wealth in ways that are acceptable to society as a whole. While evidence on the redistributive implications of tax systems in developing countries remains limited, recent findings confirm that fiscal systems in developing and developed countries can reduce inequality and support inclusive growth (Box 2.1).

The experience of developed countries shows that sound fiscal policies can play an essential role in mitigating inequalities and also can foster sustainable growth. Most countries have experienced a rise in income and wealth inequality in recent decades, but to different extents and at different speeds. The dynamics of inequality are strongly influenced by management of public wealth, regulation of financial markets, labour laws and fiscal policies such as efforts to prevent tax evasion (Alvaredo et al., 2018[6]). The experience of developed countries with regard to inequality and fiscal policies has proven that progressive taxation, well-targeted transfers and quality expenditure to benefit the poor show great potential to efficiently perform redistribution. Indeed, regression-based studies, carried out for the most part in developed economies, suggest that higher spending on social benefits and greater reliance on direct taxes may reduce inequalities (IMF, 2014[7]).

How taxes are structured matters for their impact on inequality. Indirect taxes are usually regressive because poorer populations consume a greater proportion of their income. Direct taxes levied on labour, capital income, wealth and inheritance are more likely to be progressive and are more likely to reduce inequality, if designed to impose higher tax rates on individuals who are able to contribute more (Alvaredo et al., 2018[6]).

Like taxes, social expenditures can reduce inequality. Expenditure on education and health systems that cover a wide range of the population may bring about better employment prospects, wider participation in the political process and increased well-being, and so foster equality of opportunities (OECD, 2008[8]). Social safety nets such as unemployment benefits and social pensions can improve the resilience of households to economic shocks and, in this way, help to lift the most vulnerable individuals out of poverty (World Bank, 2018[9]).

The composition of spending can be as important as the volume of public resources available, and redistributive spending can help rebalance regressive features in the tax system. It thus is important to look at redistributive impact of the fiscal system as a whole. A commitment to equity in the design of fiscal policies can itself support a reduction of inequality. Social spending as a share of GDP in most low-income and middle-income countries amounts to barely half the average social spending in high-income countries. An ongoing study of 28 low-income and middle-income countries has found that fiscal policies2 unambiguously reduce inequality and increase equality of income. They also have a poverty-decreasing effect in most countries (Lustig, 2017[10]).

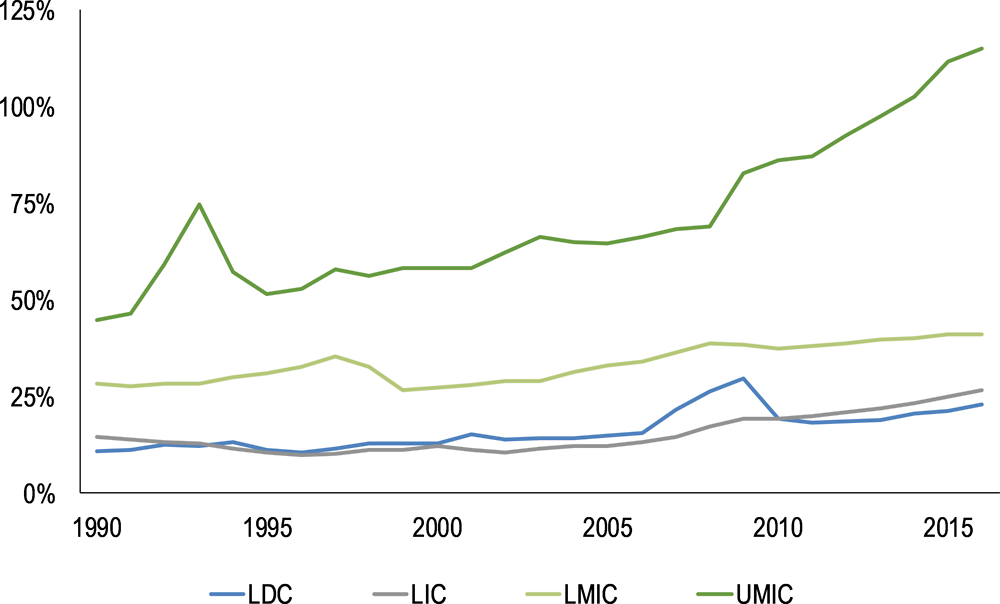

Domestic public resources are not yet sufficient to meet global and country ambitions

Countries may choose different approaches to the financing of development that involve lower tax ratios; different dimensions of development such as fragility, economic vulnerability and human capital development may affect the ability to raise revenues.3 Without an agreed, ideal tax-to-GDP ratio, a ratio of 15% is increasingly recommended as a minimum benchmark for effective state functioning (IMF et al., 2016[11]) (Gaspar, Jaramillo and Wingender, 2016[12]). As shown in Figure 2.2 2.2, low-income and least developed countries remain some distance below this ratio, although since 2005, some progress has been made in increasing the ratios. The average ratio in middle-income countries is above 15% but this is still well below the 2016 OECD average of 34.3%,4 indicating significant room to grow tax revenues to finance sustainable development. Such growth becomes increasingly urgent if – due to rising debt levels in developing countries – opportunities to finance public spending through debt financing narrow in the future (Chapter 5).

There are substantial differences in countries’ ability and capacity to increase tax revenues. Moreover, mobilising more tax revenues may not always be desirable given the opportunity costs it involves. Tax effort estimates gauge the ratio between revenue and potential revenue given a country’s current GDP, level of development, etc. While there is relatively little research in this area, one study by Fenochietto and Pessino (2013[13]) has found high-income countries showed a higher tax effort (77%) than did low-income countries (65%) and middle-income countries (64%). However, there is significant variation within these categories and a large number of developing countries appeared to be operating close to their potential. Regionally, Africa had the second-highest level of tax effort (71%), behind only Europe (77%) and significantly ahead of Asia Pacific (59%).

Especially where tax effort is already high, increasing revenues often depends not just on tax policy changes and administrative improvements but also on growth and structural changes in the economy. In consequence, growing the domestic private sector is vital, as is discussed further elsewhere in this chapter. Many developing countries also have very large informal sectors and underground economies where cash transactions leave no audit trails for tax purposes. Even where income is declared, it is often grossly underestimated. Many developing countries face additional challenges to growing tax revenues, among them weak revenue administrations and poor governance. But assertive policy approaches can make a difference, as shown in the essay on Indonesia’s tax reform (Box 2.2 “Tax reform and quality spending are crucial for a more sustainable and inclusive economy”).

International tax policies also have a substantive impact on tax revenues, for example by eroding multinational enterprises’ ability to shift profits offshore and avoid corporate taxes in the countries of operation. This is particularly important for developing countries, for which spillovers in international corporate taxation are especially marked and important (IMF, 2014[14]).

Reform is essential for revenue collection and equity promotion

Understanding that a sound tax system is a core element to support sustainable development, the government of Indonesia recently implemented the tax amnesty programme. Launched in 2016, this programme has successfully involved 973 400 taxpayers with total redemption payments reaching Rupiahs 115.9 trillion (around USD 8.5 billion) and a total of IDR 4 865.7 trillion (approximately USD 366 billion) worth of assets have been declared to Indonesia's tax office under the programme, surpassing the government’s target.

As a follow-up to the tax amnesty programme, the government of Indonesia has also implemented a comprehensive tax system reform to enhance progressivity and to address ineffective and excessive incentives and exemptions. Through simplification of the tax administration process, tax compliance will be enhanced in the short term. To maintain the compliance in the long term, tax education will be integrated into the formal education programme. The use of information technology will facilitate the improvement of tax database management and tax monitoring.

The quality of spending helps drive sustainable and inclusive development

Following an increase in global oil prices, Indonesia undertook reforms in the fuel subsidy scheme in 2015, to increase the fiscal space and to reduce incentive distortions from mis-targeted subsidies. Fuel subsidies amounting to Rupiahs 180 trillion were re allocated to more productive spending such as infrastructure financing, which increased significantly to Rupiahs 410.4 trillion in 2018 from Rupiahs 154.7 trillion in 2014.

Removal of the fuel subsidy also provided the opportunity to increase budget allocations to other priorities such as health, education and social assistance. In addition, the government is currently ramping up the social services programmes and increasing transfers to subnational governments and villages to create a more balanced, inclusive and sustainable economy.

The OECD has an important role to play

Learning from Indonesia’s experience, the OECD’s role in financing for development can include helping developing countries to bridge their policy gaps in addressing sustainable and inclusive development while also bringing them closer to a level playing field. This means capacity building through country-level policy review and global-level policy and performance benchmarking. In addition, the OECD can help to fine tune and improve the implementation of initiatives and programmes by providing review and assessment on progress, identifying problems, and providing policy recommendations at the global, regional and country level. In addition, and, based on its country-level work, the OECD can provide advice to better link global and regional initiatives to country priorities, thus further enhancing country ownership and commitment.

International efforts are needed for more domestic resource mobilisation

International partners need to consider how best to support developing countries to reach their potential to mobilise greater domestic revenue. For most countries, the most effective actions will be a combination of development co-operation and policy coherence. The Addis Tax Initiative acknowledges this: donor country signatories have committed to collectively double their spending on tax capacity development between 2015 and 2020 and to improve policy coherence for development in tax matters.

Committing resources for capacity building is important, but this must be matched with a commitment to ensuring impact. Even when doubled, ODA to domestic revenue mobilisation will only be USD 445 million and represent just around 0.3% of ODA, so ensuring maximum return is important. To do so may require new approaches to capacity building. One innovative approach is that of Tax Inspectors Without Borders, which deploys experienced tax auditors to work with countries’ revenue authorities on live cases and has mobilised USD 414 million in additional tax revenue so far. Its return on investment is thus more than 100:1.

Additionally, domestic policies in developed countries can be aligned to support domestic revenue mobilisation in other countries. The most obvious way to accomplish this is by adopting new international standards on exchange of information and taxation of multinational enterprises and by supporting their implementation. These standards commit countries to co-operation and therefore enhance the ability of all countries to raise revenues (Chapter 5). The automatic exchange of information (AEOI) will enable tax authorities to automatically receive information about their taxpayers’ offshore financial accounts. Over 100 jurisdictions are currently committed to implementing AEOI. Bringing more developing countries into this network offers huge potential, as testified by Indonesia’s experience and described in Box 2.2. The OECD/Group of Twenty (G20) Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project provides a range of tools to address the main methods used by multinational enterprises to shift profit offshore. Moreover, the 117 countries and jurisdictions that are members of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS are committed to meeting the four minimum standards that address cross-border challenges. Both information exchange and the BEPS Actions significantly increase the information available to and options for developing countries to effectively tax cross-border activity. To further realise this potential, it is important that the tools are designed in a way that is fit for purpose and especially that takes account of capacity constraints in developing countries. In this regard, the establishment of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS is a significant development as it brings developing countries into the international standard-setting processes on tax on an equal footing.

Efforts to grow tax revenues must be accompanied by support for strong public financial management systems. The role of governments is not only to mobilise resources but also to use those resources to advance sustainable development. Improvements in the tax system that are not accompanied by improvements in the way resources are spent are not likely to achieve the desired development outcomes. To ensure that resources are spent in an effective and sustainable way, it is important to embed domestic resource mobilisation approaches in broader fiscal governance frameworks.

Domestic private sector

Domestic investment is the main source of capital formation, but it appears to be in decline

Domestic private investment can take the form of investment by private enterprises of retained profits and/or finance from other sources and potentially through banks, private equity or the growing number of stock markets.

Domestic private investment is challenging to measure empirically because indicators are often mingled with other categories. One possible proxy to estimate the portion of capital formation financed by domestic resources is gross fixed capital formation less FDI as a percentage of GDP. Figure 2.3 shows that despite considerable variation across developing countries, total domestic investments generally make up a sizable portion of GDP. The relationship between domestic investments and GDP increases steeply at lower per capita income levels and reaches over 20% of GDP for many developing countries including low-income countries and lower middle-income countries. In comparison, total external financing on average represents less than 20% in low-income countries, less than 10% lower middle-income countries and less than 5% in upper middle-income countries.

Domestic private investment appears to be in decline. Excluding China, domestic mergers and acquisitions (M&A) declined by over 60% between 2010 and 2017, falling to USD 95 billion from USD 237 billion. This decline corresponds closely to the broader downward trend in foreign investment and especially cross-border M&A in developing countries, which fell by about USD 72 billion, or 30%, as discussed later in this chapter. With some notable exceptions,5 domestic M&A has fallen faster. This suggests that some of the same factors that have reversed the foreign investment trajectory, such as economic recovery in developed countries and record levels of corporate debt in developing countries, are also dampening domestic investment M&A.

To counterbalance these trends, active measures have to be taken to promote domestic investment in developing countries by addressing bottlenecks and risks. The international community can support this by providing technical as well as financial assistance for a better enabling environment including legal and regulatory frameworks.

Financial sector development is a key driver of domestic investment

In designing enabling environments, financial sector development will be key. A well-functioning financial system mobilises domestic savings, improves resource allocation, and facilitates diversification and management of risk (Levine, 2005[16]). Financial sector development is a critical enabler of the 2030 Agenda. Indeed it is included as a target in 8 of the 17 SDGs. These include SDG 1 on eradicating poverty; SDG 2 on ending hunger, achieving food security and promoting sustainable agriculture; SDG 3 on ensuring health and well-being; SDG 5 on achieving gender equality; SDG 8 on promoting economic growth and jobs; SDG 9 on supporting industry, innovation, and infrastructure; and SDG 10 on reducing inequality. SDG 17 on strengthening the means of implementation also includes an implicit role for greater financial inclusion through greater savings mobilisation for more investment and growth (UN Capital Development Fund, 2018[17]).

Globally, some progress is being made in terms of promoting financial sector development. Financial sector deepening, which can be measured by the extent of domestic credit generation and its share in GDP, has increased especially sharply for upper middle-income countries (Figure 2.4). At the same time, the ratio in low-income countries has increased by nearly 50% since 1990 but nevertheless remains very low, suggesting the need for additional deepening. Weak institutional, legal and regulatory environments and capacities are often cited as the main challenges to be overcome to deepen the financial system (IMF, 2012[18]).

In addition to depth, financial sector access, efficiency and stability are important for development outcomes (Levine, 2005[16]). Between 2011 and 2017, the proportion of the world’s adult population with an account at a financial institution grew to 69% from 51%, an increase of about 1.2 billion people (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018[19]). Technological advances have led to an expansion of financial services: mobile banking services now are helping to reach large numbers of unbanked people and extend formal financial services to the poor, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, 73% of adults have a mobile payment account and about 50% have one in Uganda and Zimbabwe (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018[19]). Nevertheless, serious concerns remain about the security of transactions that are made through mobile banking, and regulatory mechanisms are not yet in place (Reaves et al., 2017[20]).

Foreign-owned banks dominate the banking systems of many developing countries, notably in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. This brings competition and efficiency but also the risk of transmitting external shocks. For developing countries, the median share of assets held by foreign banks rose to 52% in 2008 from 8% in 1995. In comparison, the median share in developed countries rose to 27% from 5% over the same period.6 Foreign banks can bring competition, efficiency and a stabilising influence on domestic economies in times of crisis (Cull et al., 2017[21]). But the global financial crisis highlighted that foreign banks also can transmit external shocks and crises to the domestic economy by reducing their lending earlier and faster than domestic banks and by repatriating funds to their home countries (Anginer et al., 2014[22]).

There have been efforts since the crisis to ensure that developing country concerns are reflected in the international financial system. At the request of the G20, the Financial Stability Board, in collaboration with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, has been monitoring the effects of regulatory reforms on emerging markets and developing economies, taking developing country concerns into account in the design of the international regulatory framework. With the recent finalisation of global financial regulatory reforms, international financial organisations also are preparing to step up capacity-building efforts to assist the implementation of the new standards. An example is the launch by the IMF of the Financial Sector Stability Fund in November 2017 to assist low-income and lower middle-income countries as they assess and address risks and vulnerabilities in the financial sector.

Despite significant progress, deficiencies or market failures can often hamper access to finance for segments of society. A lack of sustainable lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) constrains growth in low-income countries. The International Financial Corporation (2013[23]) estimates that the credit financing gap for formal SMEs in developing economies is close to USD 1 trillion. A gender gap in access to finance also persists. Globally, 72% of men have a bank account compared to just 65% of women, and the gender gap is even higher – at nine percentage points – in developing countries (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018[19]).

Policy makers have to ensure that the financial sector is socially and environmentally sustainable. Initiatives to build what Grameen Capital India has termed a “capital-with-a-conscience ecosystem” are examples of ongoing efforts described in Box 2.3 “Getting private resources on board for sustainable development”. Particular attention has to be given to low-income countries, as financial sector inefficiencies tend to weigh more heavily on these places than on middle-income countries, as the former tend to be more vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices and external financing (Eichengreen, Park and Shin, 2017[24]).

GOOOOAAAAAALLLLLL! The frenzied celebration that reverberates across the globe every time a goal is scored reflects the seemingly universal passion for football. The game cuts across generations, blurs political boundaries and traverses ethnic divisions. Sadly, some other things do too – hunger, refugee crises, poverty and global warming, to name a few. And yet, everywhere I look, there also exist shining examples of H.O.P.E.

Holistic approach. Governments, corporations, capital markets, non-governmental organisations, etc. need to find integrated solutions. One exceptional example is the catalytic potential of using corporate social responsibility/philanthropic capital to de-risk investment from the capital markets. The financial sector can help guide companies to look towards a long-term sustainable future. Grameen Foundation’s Growth Guarantees programme did precisely that by bringing together donors, international and local banks, microfinance institutions, and poor, vulnerable women borrowers.

Outcome funding. For too long, the focus has been financing for inputs such as grants for health programmes, budget allocations for education outreach and similar targets. However, the recent innovations in outcome financing or “pay for success” seem to be gathering momentum. The Educate Girls programme in Rajasthan, India, aims to improve learning outcomes and enrolment in schools in Rajasthan. This has tremendous potential, as capital market players can collaborate with development agencies to structure innovative financing vehicles that de-risk the investor and ensure outcomes are well-defined, measured and achieved, leading to a win-win situation for all.

Policy-led leadership. Policy makers have a key role as enablers in meeting the 2030 Agenda. Some of the recent policies in India are heartening – changing the country’s fund architecture to include social venture capital funds, the Companies Act regulation proposing that 2% of profits be contributed to CSR, the Central Bank regulations related to priority sector lending and small finance banks – and they point as well to a greater sensitivity and a crowding-in of conscious capital. Similar policy initiatives in developing countries could trigger the initial momentum required to catalyse the development of the market. Globally, countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States have also instituted treasury initiatives to attract commercial capital to the impact landscape.

Ecosystem. Each stakeholder has a role to play. But the effect is even more pronounced, scalable and sustainable when an enabling ecosystem is created. It is heartening to witness the collaboration, especially regarding sustainable development, among many multilateral agencies, foundations, corporations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The OECD is a stellar case in point with its pioneering work on such issues as impact measurement and blended finance. At Grameen Capital India, we are committed to building a “capital-with-a-conscience” ecosystem, helping to connect enterprises serving the poor with mainstream capital markets. Today a unique debt vehicle has been added, with plans to create a Social Venture Fund and a Social Stock Exchange to democratise funding access for impact enterprises.

Clearly, desperate times call for creative, compassionate and collaborative (and sometimes desperate, out-of-the-box) measures if we are to meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. I can only imagine the universal euphoria that will erupt when each goal is met. I am sure I will be cheering with my loudest “GOOOOAAAAAALLLLLL!”

External actors and financing flows

External flows can be crucial in financing the SDGs. They can help to fill gaps in low domestic savings, fund productive investments and promote development of domestic enabling environments. External financing flows are defined by the type of actor. Financial flows that originate from public sector actors, i.e. bilateral and multilateral providers, are referred to as official flows and are either concessional or non-concessional. The financing provided by private actors, on the other hand, take the form of commercial investments, philanthropic flows and/or remittances.

External financing flows increased through the MDG era but have fallen since 2013

The volume of external finance available to developing countries has been substantial, increasing to USD 1.7 trillion in 20167 from roughly USD 675 billion in 2000. But trends since 2013 are more sobering, with a decline in total external finance of 12% (see Figure 2.5).

Trends over time of external flows vary depending on the type of flow:

-

The rates of increase in private investment flows have declined, a trend that holds across all income groups.

-

Official flows to low-income countries have declined recently in favour of a more rapid increase for middle-income countries.

-

Growth in remittances has remained stable in the low-income country context while remittances are increasing at a slower pace for upper middle-income countries.

Different actors have different roles

The international community calls on all the various actors to play a part in financing for sustainable development, but this goal is complicated by the individual objectives of different actors.

-

Concessional flows as well as philanthropic flows usually aim to further sustainable development.

-

Commercial investments are driven by a profit motive.

-

Remitters are mainly motivated to contribute to the well-being of individual recipients at the household level.

To evaluate the implications of trends in cross-border actors and their resources, it is important to understand their role in the sustainable development financing system. Private sector actors can bring productivity gains and job creation while the public sector can have a comparative advantage in targeting poverty and gender inequality. Moreover, the sectoral destination may vary according to the type of actor. While the private sector tends to invest in economic sectors such as manufacturing, official flows are well placed to target social sectors such as health and education (see Chapter 4). These roles can change at different income levels (see Chapter 6).

The destination of flows also varies by the type of actor. Low-income countries tend to have a higher reliance on official and especially concessional flows while for lower middle-income countries (LMICs), remittances are a major source of external financing. Non-concessional official flows target LMICs and upper middle-income countries (UMICs). The major share of private finance goes to UMICs but it is an important source for LMICs as well (Figure 2.6).

Currently, USD 1.7 trillion in resources are already flowing into developing countries but not every dollar will have the same development impact, as Chapter 4 discusses further. To ensure these are spent in a way that is conducive to sustainable development, the diversity and distinct comparative advantages of actors must be exploited.

Commercial investors

-

Private investment including FDI, portfolio investment and long-term debt to developing economies amounted to around USD 890 billion in 2016.

-

Investment flows are drying up one after another. This process started with cross-border mergers and acquisitions, which started to decline around 2012 and were down by USD 72 billion in 2017 from the high of USD 234 billion reached in 2011.

-

FDI flows, which constitute the largest private investment flow, are following this downward trend. Over the period 2015-16, FDI flows to developing countries fell by USD 70 billion, or 11%, a trend that appears to have continued into 2017.

-

Most recently, project finance in the first half of 2018 was down by 30% year on year.

Commercial investors have become increasingly important and diverse

Over the past 30 years, multinational enterprises (MNEs) have become important actors channelling FDI8 to establish a presence in developing countries. Over the last 20 years in particular, the nature of MNE investment flows to developing countries has evolved beyond a relatively narrow focus on the extractive industries to become one of the cornerstones, along with trade, of global value chains (GVCs) Box 2.4. Many developing countries are now involved in the production of increasingly sophisticated goods and services that feed into the international production networks of MNEs. Global value chains are increasingly used as channels contributing to sustainable development, mostly through financial transfers but also through the transfer of knowledge, standards and skills.

MNEs also engage in portfolio investments, especially within the context of strategic partnerships with other MNEs and domestic firms. Multinational enterprises base their decisions to invest on a broad range of factors including market size, labour force skills, macroeconomic and institutional stability, physical infrastructure, and natural resources.

Other actors involved in portfolio investments include institutional investors such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, mutual funds, private equity funds, and hedge funds. Often these investors seek opportunities in developing countries to reduce the risks of their investment portfolios through diversification and higher returns. Since financial assets in developing countries have low correlation with returns in developed economies, they complement the risk-return profile of financial investors in developed countries.

Trade has always been central to economic co-operation and development. The current global system overseeing trade and investment evolved from efforts to create a rules-based system after the Second World War that would regulate investment and business practices, establish labour standards, and promote development. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, or GATT, grew out of these efforts and led to the World Trade Organization (WTO). A series of tariff reductions resulted in significant trade liberalisation and growth in international trade. For several decades, global trade grew substantially faster than global GDP.

Global value chains (GVCs) have had a significant impact on development. These international production and distribution networks have increased developing countries’ growth prospects and integration in global markets. For example, their share of global value-added trade rose to 40% in 2012 from 20% in 1990 (UNCTAD, 2013[25]). GDP-per-capita growth rates in economies showing the fastest‐growing participation in global value chains are about two percentage points above the average. However, the benefits of GVCs are concentrated in specific regions including North America, Europe and East Asia, meaning many developing countries are being left behind (UNCTAD, 2013[25]).

Multinational corporations generate some 80% of trade flows (UNCTAD (2013[25]), which are intrinsically linked with FDI decisions. Trade and FDI can be seen as two facets of a single economic activity: international production sharing (World Economic Forum, 2013[26]). The positive correlation between FDI stocks and global value chain participation is especially present in the poorest countries, indicating that FDI may be an important way for developing countries to access and increase their participation in global value chains (UNCTAD, 2013[25]).

Some GVC activities are declining, raising questions about the future of trade’s impact on development. Since the Second World War, the volume of world trade has on average grown about 1.5 times faster than world GDP, and in the 1990s it grew more than twice as fast. However, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the ratio of trade growth to GDP growth has fallen to around 1:1 and GVC activities also decreased (World Bank Group et al., 2017[27]). It is not yet clear whether this may change the nexus between investment, trade and development, or what the impacts will be on financing for development.

Investors in developing countries themselves account for one-quarter of global FDI outflows, up from around 12-13% before the 2008-09 global financial crisis (World Bank, 2013[28]). The rapid rise of China as one of the world’s largest sources of FDI, including through Chinese state-owned enterprises, has been particularly important (Box 2.5).

The growing visibility of this relatively new kind of actor – the state-owned enterprise (SOE) – goes hand in hand with the growing significance of investments from developing countries, as these countries often channel their investment through SOEs. Although not strictly a private sector actor, state-owned enterprises often behave in ways that are similar to their private sector MNE counterparts. This may mask significant government involvement in some cases. Data on FDI do not allow for a distinction between international investments by state-owned enterprises and privately-owned MNEs, but data on cross-border M&A suggest conservatively that the former account for around 10-20% of global FDI flows.

Finally, a multitude of private actors are often involved in project finance, one of the most important forms of investment from a development perspective and a primary method for financing so-called greenfield investments. Project finance usually involves a combination of MNEs and commercial lenders as well as many of the public-sector partners discussed later in this chapter, such as bilateral and multilateral donors, regional development banks, and export credit agencies. Although project finance is smaller in volume terms than are other private flows, it is important from an SDG perspective insofar as it often directly supports specific SDGs. Among these are SDG 7 (the development of renewable sources of energy), and SDG 9 (transport infrastructure).

An increasingly important source of investment in developing countries is China. A major driver of China’s outward investment has been its One Belt, One Road initiative, which has channelled billions of dollars into infrastructure projects in the Eurasian countries and beyond (OECD, forthcoming).

One indicator of China’s growing influence is the increase in merger and acquisition (M&A) investments. Chinese M&A accounted for 20% of all cross-border M&A received by developing countries, making China the top source of investment into developing countries ahead of Japan and the United States. Chinese investment in developing countries grew rapidly beginning around 2010 and has continued to grow even as the Chinese government has been reigning in outward investment more generally. Overall outward M&A from China declined by USD 115 billion, or 53%, between 2016 and 2017, but M&A to developing countries doubled to USD 25 billion (Figure 2.7).9

This increase in Chinese investment in developing countries would seem to represent a purposeful, policy-driven trend. Most of this investment is being undertaken by fully owned Chinese state-owned enterprises, as it has been since the Chinese investment boom in developing countries started in 2010. Over this eight-year period, fully owned state-owned enterprises undertook 63% of this investment in value terms.10 These data likely understate the extent to which the government participates in China’s outward investment flows, especially in the context of the One Belt, One Road initiative, insofar as they do not include the activities of partially state-owned firms or the role of state-owned banks in financing outward investments by privately owned firms.

Private finance can bring benefits beyond pure financing

Private investors are the single largest providers of cross-border financing to developing countries. This means that encouraging even a relatively small share of this investment to align to the SDGs has significant potential. Even without intending to, private investors and the FDI they generate are particularly relevant for the SDGs for a variety of reasons including but not limited to the following:

-

They transmit new technologies

-

They provide access to new international markets

-

They can fill gaps that domestic investors and other investors or sources of financing cannot reach

-

They can generate decent jobs and tend to pay higher wages and better uphold the principles of responsible business conduct than domestic enterprises

-

They tend to create business linkages in the economy that support domestic enterprises

-

They generate revenues

Private sector actors can play especially important roles in the financing of specific Sustainable Development Goals such as SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy) and SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure). Where public budgets are under strain, private investors can fill infrastructure financing gaps and bring expertise to improve project efficiency. Chapter 4 explores the specific contributions of commercial investors towards the SDGs in greater detail.

These benefits, however, are not always automatic or even guaranteed. The logic and motivations driving private investors differ from those of public actors and investment returns need to be transformed into development gains. To harness the full sustainable development potential of private investors, it is important to identify mutually beneficial opportunities that satisfy the objectives of private actors and contribute to the achievement of the SDGs at the same time. Moreover, a key challenge is to move away from a narrow focus on quantities and volumes to the quality and development impact of financing, as discussed further in Part II.

An era of foreign investment prosperity for developing countries comes to an end

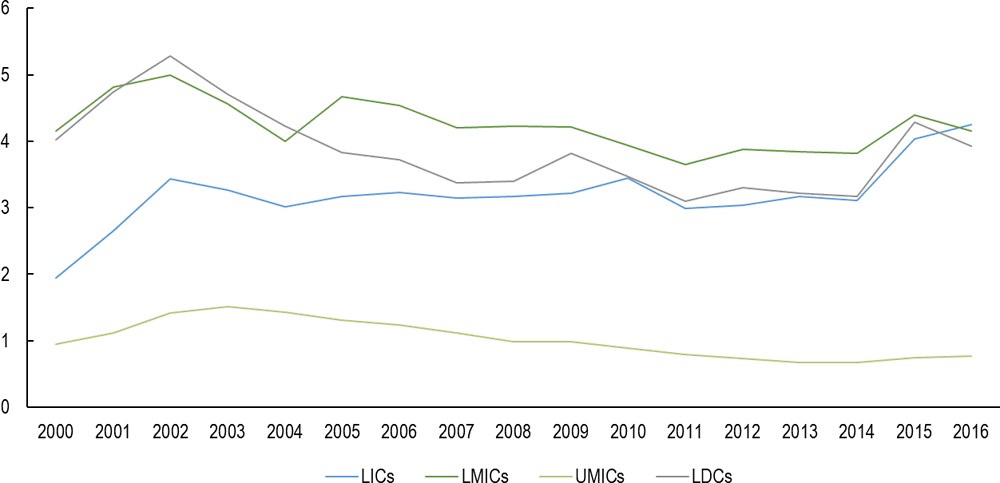

Private investment including FDI, portfolio investment and long-term debt to developing economies amounted to around USD 890 billion in 2016. At their peak in the early 2000s, private investment inflows amounted to more than 8% of GDP for LICs and UMICs.11 In the period 2000-16, private investment as a share of GDP was on average 6.2% for LICs, 5.6% for UMICs and 4% for LMICs. With fluctuations from year to year, the share of private investment over GDP has generally declined compared to the early 2000s and early 2010s (Figure 2.8).

FDI, which makes up the largest part of these flows, has shown relatively solid growth and resilience until recently. Developing economies fared relatively better than developed countries during the financial crisis and experienced a one-year decline in FDI of around 30%, with volumes dropping to around USD 430 billion12 in 2009 compared to the 40% drop in global FDI flows. FDI flows recovered strongly in 2010, thanks in large part to a 50% increase in flows to developing economies that year. Over the following five years, flows to developing countries were relatively stable, growing to around USD 630 billion in 2015.

This period of FDI prosperity, as some have called it, came to an end in 2016, when FDI flows reversed course at the global level. Over the period 2015-16, flows to developing countries fell by USD 70 billion, or 11%, in a trend that seemed to continue into 2017. The reasons behind these declines include a mix of broad cyclical and more country-specific factors. Among the former are tighter monetary policy in developed economies and the reversal of the commodity super-cycle (OECD, 2016[31]). More country-specific factors include various sources of geopolitical instability, concerns over rising protectionism and record levels of corporate debt in emerging markets (IMF, 2016[32]). FDI outflows to developed countries followed a similarly broad reversal.

Trends in mergers and acquisitions13 in developing countries show that, in contrast to FDI inflows, M&A inflows were already beginning to decline in 2012 (Figure 2.9). Overall, M&A volumes in developing countries were USD 162 billion in 2017, down by USD 72 billion from the high of USD 234 billion that was reached in 2011. The biggest declines were in upper middle-income developing countries, with annual M&A inflows to China decline by USD 19 billion between 2011 and 2017, to Chile by USD 14 billion, to Turkey by USD 10 billion and to Brazil by USD 9 billion.

The decline in cross-border M&A would not be a negative development on its own had it been offset by a rise in domestic M&A, since this is a trend generally associated with economic development. Over the past decade, developed countries received 29% of their M&A investment from foreign sources; 71% was generated domestically.

In contrast, developing countries received 44% of their M&A investment from foreign sources and generated 56% domestically. The main reason for this difference relates to domestic market weaknesses, imperfections and failures such as a weak domestic financial sector. These can hold back domestic investors but foreign investors are able to overcome them given their significant resources. However, as noted, domestic M&A in developing countries has trended downward more rapidly than cross-border M&A flows, suggesting an overall decline in private sector investment in developing countries.

This downward trend is mirrored in project finance flows. Despite showing resilience to the overall downward investment trends in 2016 and 2017, project finance in 2018 experienced its worst first half in ten years, with volumes down 30% year-on-year (Figure 2.5) and affecting all regions. The number of new transactions declined by 50% to 377 in the first half of 2018 from 725 in the same period of 2017. In addition, around 38% of project finance was for refinancing purposes, up from 24% in the first six months of 2017. In other words, just as the volume of project finance is declining, a shrinking share is going towards new projects.

Policy action is needed to counteract the decline in foreign investment

Business investment in developing countries is currently like a river whose feeder streams are drying up one after another. This process started with cross-border M&A, which started to decline around 2012. This was followed declines in FDI and domestic M&A in 2016, and most recently, in the first half of 2018, in project finance. Portfolio investment is also under pressure in developing countries as interest rates begin to rise in the developed economies and record-high levels of corporate debt have raised the spectre of financial turbulence (OECD, 2018[33]).

Whether this situation worsens depends on many variables. But the current trend is clearly not encouraging. Given data limitations, putting a precise number on the extent to which private business investments in developing countries have shrunk is not possible. However, an orders-of-magnitude calculation based upon cumulative declines in FDI against a counter-factual assumption of zero growth from the previous high in FDI in 2011 suggests that developing countries have foregone between USD 400 and USD 450 billion of FDI from 2012-2016.

Given this scenario, which is leading from billions to millions instead of billions to trillions, an urgent and challenging policy agenda suggests itself. Elements of such an agenda might be expected to address the following challenges:

-

The global rules for trade and investment need to be improved and made to work better in support of an open, rules-based global economy. One of the greatest threats for developing countries would be the widespread outbreak of protectionist trade and investment wars that could accelerate what to date has been a significant but measured retreat of the private sector from developing countries.

-

As private sources of financing that align with and can support achievement of the SDGs retreat, public sources will become relatively more important and will need to play a counter-cyclical role, while recognising that they cannot fill the gap left by the private sector. The author of the essay “Adapt finance and the financial system to “save the world”” calls for the strategic use of public resources to mobilise and attract private capital. This will be difficult in developing countries given that declining business investment has a knock-on negative impact on the ability of governments to maintain adequate levels of tax receipts; this could feed negative spirals as public spending on critical business infrastructure is cut back, further undermining business climates. Co-ordination among donors to maximise the development impact of official development assistance ODA and other forms of public financing becomes critical.

-

Considerable scope remains for pursuing domestic policy reform agendas to improve business climates and to put in place investment promotion and facilitation strategies. Private investment has been declining but continues to play a critical role in helping countries to develop critical infrastructure, generate employment and foster innovation. Governments have an important role to play in helping to better align business interests and the SDGs, thus generating more development impact from less investment. Fostering such closer alignment can also be achieved through the promotion of responsible business conduct.

Private flows constitute the largest single source of foreign financing going to developing countries. Looking forward and beyond the looming development crisis, much more needs to be understood about private flows and the full implications of this financing for achievement of the SDGs. The AAAA created high expectations regarding the contribution of the private sector to sustainable development – expectations that stand in contrast to the current trend line of private flows. This points to an important knowledge gap that will need to be filled to inform an empirical policy-oriented agenda in the future.

Without a doubt, 2015 was a pivotal year. The Addis Ababa conference on financing for development. The unanimous agreement in New York by the United Nations of the Sustainable Development Goals. The climate agreement in Paris. A truly ambitious set of goals and commitments and nearly three years on, substantial progress is being made. However, if we are genuinely serious about these agreements and about these commitments, then it is imperative that we adapt finance and the financial system. Both of these must be revamped to meet the expectations we have created. We need to keep pushing hard to make the necessary progress and get points on the scoreboard before apathy sets in.

Collectively, we need to focus on the key tenet of “billions to trillions” that I and others led back in 2015. We must mobilise and attract private sector capital to finance much needed investment in emerging and developing economies. History has demonstrated that this capital will typically not flow there naturally, at least not in the amounts needed. Mechanisms need to be set up that will create that flow.

Here is where the rest of the system has a vital role to play. Embedding such an approach into the overall finance system will drive the capital. This means that every participant, every stakeholder, has to orientate the way it thinks about capital mobilisation. The multilateral development banks and donor countries are pivotal as they have the resources and the appropriate layers of capital and systems that can be brought together with the private sector capital for that clichéd “win-win”. Regulators are also critical and need to continually evolve to meet the new paradigms and to help fuel innovation within an appropriate framework. This is not an easy task by any means but is much needed if we are to restore the trust that was lost following the financial crisis. The pressure is even greater now to ensure that we are undertaking more than just superficial changes but rather proper, deep transformations – a real change for many of the incumbent participants.

Co-operation is key. The public and private sectors need to work together. This necessitates a fundamental shift in how each views the other and how, on a basic level, each is willing to engage in business with the other. This will be successful only when both make significant moves. Improved co-operation among public sector actors also is needed. Additionally, the private sector must continually reassess and advance to a more long-term perspective in the way it carries out its business. The real beauty of all this change is that, given the different incentive mechanisms, the new co-operation can be truly symbiotic. Money will follow cultural changes. Shift in culture will mean shift of money!

Fundamental change is needed. Stamina and patience are required. If we can come together and adapt, if we are willing to pay this “price”, then we stand a chance of achieving the rightly ambitious goals. The rub? If we are serious, if we are not inconsequential – which like most I hope we are – we do not have a choice.

Migrant remitters

-

Beginning in the early 2000s, global remittance flows increased sharply, aided by technological advances in financial infrastructure that significantly reduced the costs of transmitting funds.

-

The amount of global remittances rose to USD 466 billion in 2017 from USD 122 billion in 2000, making remittances the second largest type of cross-border financing to developing countries.

-

The average cost of sending remittances has remained flat at 7.1% – far higher than the SDG target (indicator 10.c) of less than 3%.

Migrants from developing countries act as providers of financing for sustainable development

Recent years have seen an increase in international migration. In 2015, 3.3% of the world’s population or 244 million people were international migrants. This is a significant increase from the estimated 155 million people who were international migrants in 2000 and who then represented 2.8% of the world’s population. Many of the migrants come from developing countries and send home remittances to support their families.

Decisions to send remittances are essentially private and personal in nature. Remitters may be motivated by altruism, but they are not necessarily taking into explicit consideration the achievement of the SDGs in their home countries. As outlined in Box 2.7 migrants are influenced by a range of factors that can include a desire to support family members and the intention to prepare for a return to their home country (OECD, 2006[34]). The willingness to remit also depends on the duration of migration (the length of time a migrant intends to stay abroad and whether the stay is temporary or permanent); family situation (whether the migrant is single or married and has children); and network effects (whether the migrant moved alone or with family members and the degree of attachments to those left behind) (OECD, 2006[34]).

A number of theories to explain the motives for sending remittances have been put forward, ranging from pure altruism (e.g. the migrant’s concern for relatives left in the home country) to pure self-interest (e.g. aspiration to inherit or desire to invest in financial assets or real estate in the home country). One theory between those two extremes rests on an insurance model that views migration and remittance as a household risk strategy that builds on informal agreements with family members remaining in the home country. In this scenario, the migrant’s family finances the initial costs of the migration project that the migrant alone often cannot cover. In turn and once the migrant secures employment, high enough earnings and positive expectations about further income, he or she sends remittances to the family to finance investments such as education of the younger generation and/or to support the family during emergencies and times of need (OECD, 2006[34]).

Remittances are also sent collectively through migrant and diaspora associations such as hometown associations or diaspora direct investments, often with an explicit development orientation. Diaspora groups form hometown associations in the country of destination to collectively support the country of origin through investments in development projects. Mexican migrants in the United States, for example, form such associations to channel funds back to Mexico’s poorest rural areas with high levels of out-migration. Another form of such financing is investment by diaspora-owned firms or firms with diaspora members in top management in productive activities (Rodriguez-Montemayor, 2012[35]).

Remittance volumes have surged to become the second largest source of external financing

The volume of remittance flows has continued to steadily climb in tandem with the movement of people. Experience has shown that remittances, constituting a steady stream of foreign exchange, can help to alleviate poverty and stimulate economic growth in migrants’ countries of origin (Singer, 2010[36]). A case in point is Korea. Remittances from Korean workers in West Germany and the Middle East and from Korean soldiers deployed to Viet Nam provided foreign exchange that contributed to jumpstarting the rapid economic development in the 1960s.

Beginning in the early 2000s, global remittance flows increased sharply, helped by technological advances in financial infrastructure that significantly reduced the costs of transmitting funds.14 The amount of global remittances rose to USD 466 billion in 2017 from USD 122 billion in 2000, making remittances the second largest type of cross-border financing to developing countries. Regional growth trends and projections suggest remittances will increase in developing countries overall, following a decline in 2015 and 2016 that is attributed to weak economic growth in the sending countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Russian Federation (“Russia”) and to exchange rate movements.

Remittances make up a sizable portion, around 4%, of GDP in both lower middle-income countries and low-income countries (Figure 2.10). For lower middle-income countries, it has remained fairly constant from the early 2000s through 2016. But the share of remittances in GDP increased sharply for low-income countries, doubling during this period. Among the top receiving countries in terms of remittances as a share of GDP are small economies such as Kyrgyzstan, Tonga and Tajikistan, which each receive more than or close to 30% of GDP in remittances. In nine out of ten top receiving countries, remittances correspond to 20% of GDP or more.

Transaction costs involved in sending remittances to developing countries, however, far exceed the SDG target (indicator 10.c) of less than 3%. The average cost of sending remittances has remained flat at 7.1% (Figure 2.11Moving towards financing for development), with the lowest average transaction costs in South Asia (5.2%) and highest in sub-Saharan Africa (9.4%). Remittance costs across many African corridors and small islands in the Pacific remain above 10% because of the low volumes of formal flows, inadequate penetration of new technologies and lack of a competitive market environment (Ratha et al., 2018[37]). Potential remedies in terms of domestic policy are discussed in the essay “How to mobilise remittances for development financing”.

Remittances can be mobilised for development financing

For a long time, remittances were ignored as small change. But these small sums of money sent by migrants to family back home in developing countries actually add up to more than three times the total of official development assistance (ODA). In 2017, remittances reached USD 466 billion. In contrast to the outlook for ODA – flat at best for the medium term – remittances are expected to rise at an annual rate of over 4%. The true size of remittances, including flows through informal channels, is significantly larger.

Yet remittances are private money and they should not be used (through taxes) for public spending. There is also a concern that most of the remittances received by poor families are used for essential consumption such as for food, clothing and housing, although we know now that they are also used for financing education and business investments. Remittance flows are more stable than private investment flows. These flows are also better targeted to the needs of recipient households, given they are timelier, and better monitored than official aid.

Can these private flows be used for more productive investments and for funding public goods? The answer is yes. Removing regulatory barriers can reduce remittance costs and translate into additional USD 20 billion in flows per year to poorer households in developing countries. Remittances can be used to improve sovereign credit ratings and bond ratings, thereby reducing the costs of financing programmes. And remittance channels can be used to mobilise USD 50 billion or more of diaspora savings through the issuance of diaspora bonds.

Lower regulatory barriers

Today, when the costs of cross-border communication have become negligible, it costs more than 9% on average to send money to a family in sub-Saharan Africa. Except in a few large country corridors, remittance costs on average top 5% in all regions, which is significantly higher than the SDG target of 3% (SDG indicator 10.c). If remittance costs are reduced by 3 percentage points, say, they could save more than USD 20 billion in the hands of migrants and their families. Remittance channels are used not only by migrants to send money to families but also for small payments for trade, investment and philanthropy.

Remittance costs can be reduced rapidly by allowing new remittance service providers into a market dominated by few large players. One self-evident option is to end exclusivity partnerships between the national post offices (especially in the OECD countries) and large money transfer operators. Another would be to recognise that small remittances are overwhelmingly used for personal uses and carry very low risks of money laundering and financing of terrorism. This would open up the market to new players using more efficient and cheaper technologies such as mobile phone or blockchain technologies.

Remittances are the most stable form of cross-border flows and can have a positive development impact

Migrants’ remittances present the most stable form of cross-border flows to developing countries. While private capital flows tend to rise during favourable economic cycles and fall in bad times, remittances appear to react less violently and may even rise during recessions in recipient countries. For example, remittances to developing countries continued to rise steadily in 1998-2001 when private capital flows declined in the wake of the Asian financial crisis (Ratha, 2005[39]). While remittances are relatively stable at aggregate levels, inflows to individual developing countries may be quite volatile, impacting on economic stability (Jackman, 2013[40]).

These benefits of remittances enhance the creditworthiness of developing countries. The World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Framework allows recipient countries to carry higher levels of debt when the ratio of remittances is higher than 10% of their domestic income and 20% of exported goods and services (IMF, 2017[41]).

At the micro level, too, remittances can have a positive impact on development and poverty. They are shown to increase the income of recipient households and remove financial constraints, reinforcing a household’s ability to resist external shocks. In some countries, “households that receive remittances are more likely to engage in productive activities such as owning businesses, real estate or agricultural assets” and tend to spend more on education (OECD, 2017[42]). However, the link between remittances and higher investments is not always straightforward. In some cases, remittance income is spent on the daily consumption of basic goods rather than in investments in human and physical capital (Adams and Cuecuecha, 2010[43]).

Policies in remittance sending and recipient countries can enhance development impact

How can remittances be best harnessed to benefit sustainable development? Although an important source of cross-border financing, remittances must be considered separately from other forms of financing for development due to their essentially personal nature. Not all remittances contribute to sustainable development and measuring the portion of remittances targeting sustainable development is challenging (Chapter 4).

To strengthen the development impact of remittances and make sure that remittances can be used in the most beneficial way for the migrants and their families, policy should focus on creating an enabling environment that supports the use of remittances for long-term investments (OECD, 2017[42]). For example, policies that foster financial inclusion of migrants and remittance recipients and that promote financial literacy can help to channel remittances towards investment in human capital and productive activities.

Domestic policies in remittance-sending countries that help to ensure the effective transfer of remittances at the level of non-state intermediaries also can enhance the development impact of remitters and diaspora communities (Chapter 5). Both the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and the 2030 Agenda point to high transaction costs as a potentially productive area for policy intervention.

Philanthropic foundations

-

Philanthropic giving is dominated by a handful of large players based in the United States and Europe. Just 20 foundations provided 81% of total philanthropic giving to developing countries during 2013-15. Nearly three-quarters of the amount originated from foundations based in the United States.

-

Philanthropic giving to developing countries amounted to USD 23.9 billion in the 2013-15 period, or USD 7.96 billion per year on average.

-

Middle-income countries received 67% of the flows. 37% went to lower middle-income countries and 30% to upper middle-income countries. Only a third of the flows went to least developed countries and other low-income countries.

Foundations continue the long-standing human tradition of philanthropic giving

Philanthropy has been a part of human civilisation for thousands of years. In ancient China, clan-based lineage organisations provided allowances to widows and orphans, distributed grain to the poor and built schools for children (UNDP, 2016[44]) Philanthropy is also deeply ingrained in the Judeo-Christian tradition, evidenced by the ancient Hebrews’ gifting of one-tenth of their income to those in need, and it is also a pillar of Islam, which requires zakat giving (Andrews, 1950[45]).

In the 20th century, some of the wealthiest industrialists in the United States, such as John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, organised their philanthropic giving at an unprecedented scale with the aim of systematically addressing the social needs of the day. These philanthropists said they considered it the duty of the rich to use their skills and fortune to benefit the wider community and poor.

A surge in entrepreneurial wealth over the last 30 years has brought with it a new class of philanthropists. By bringing a business approach to philanthropy and focusing on strategy, innovation and partnerships, these actors play a unique and pioneering role in the financing for sustainable development system.

In terms of volumes, a handful of large players based in the United States and Europe dominate philanthropic giving to developing countries. A survey conducted in connection with the recent OECD (2018[46]) report, Private Philanthropy for Development, finds that just 20 foundations provided 81% of total philanthropic giving to developing countries during 2013-15 and nearly three-quarters of all such philanthropy originated from foundations based in the United States. The Annex to this chapter provides further details. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, headquartered in the United States, alone accounts for nearly half (49%) of total giving, which largely explains the finding about geographic concentration. Of the 143 foundations included in the OECD data survey sample, other top originating countries were the United Kingdom (7% of total philanthropic giving), Netherlands (5%), Switzerland (2%), Canada (2%) and the United Arab Emirates (2%).

Philanthropic giving nevertheless is relatively small in volume

Philanthropic giving to developing countries amounted to USD 23.9 billion in the 2013-15 period, or USD 7.96 billion per year on average (OECD, 2018[46]). While philanthropic giving remains relatively modest compared to financing for development more broadly, foundations have become major partners in some specific areas. For example, in the health and reproductive health sectors in 2013-15, support from philanthropic foundations constituted the third-largest source of financing for developing countries, after support from the United States and from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Almost three-quarters (74%) of foundations’ giving in 2013-15 supported activities in social infrastructure and services such as health, education, human rights and social protection (Figure 2.12). Overall, health was the main sector targeted by philanthropic giving – far ahead of other sectors – with USD 12.6 billion or 53% of the total. The Gates Foundation was the major player in this arena, accounting for 72% of total giving to health. The donations of other foundations accounted for only the remaining 28% of the sector total, although the OECD survey shows that health and reproductive health was also their main funding priority.

Philanthropy also mainly targeted middle-income countries, who in total received 67% of the flows. 37% went to lower middle-income countries and 30% to upper middle-income countries. Only a third of country allocable funding went to least developed countries and other low-income countries (OECD, 2018[46]).

Some philanthropic foundations play key roles innovating and collaborating with other actors

Philanthropic foundations are increasingly influential actors in international development. The largest players in particular, and notably the Gates Foundation, are actively shaping the agenda setting and funding priorities of international organisations and governments by virtue of the size of their grant making, networking and active advocacy.

In some cases, philanthropic foundations can play a special role in financing for sustainable development because they are relatively less risk averse and relatively more are willing to invest in innovative business concepts and financing models (Marten and Witte, 2008[47]). Box 2.9 “Unlocking financial innovation to accelerate pro-poor innovation” reviews the range of possible collaborative opportunities with philanthropic foundations who can provide the seed capital for innovative solutions to development problems. Yet the vast majority of philanthropic foundations are traditional in the instruments and channels of delivery they use (OECD, 2018[46]).

Combined with commitment from the global community, technology and innovation can be powerful forces for improving global health and reducing poverty. Think of the potential of new crop varieties to help alleviate extreme poverty by increasing crop yields, resilience and nutritional value. Or the potential benefits of developing and widely deploying digital identification systems that can improve access to government services and give impoverished people a chance to join the formal economy and improve their lives.

But for these visions to become reality, change is needed in how the development community does business. First, governments and donors need to work more closely with those who have special expertise in helping countries adopt innovative technologies. The private sector and philanthropic organisations can and must help in this regard. Second, scaling innovation will require more flexible financing policies and a greater appetite for risk on the part of the largest providers of development finance and most notably multilateral development banks, other development finance institutions, and large institutional and private investors.

One way this can happen is through a segmentation of development finance. Philanthropic capital, which can absorb higher risks than many other types of development finance, should be used to pilot innovation. International financing institutions can then take successful pilots to scale more often than they do now. Philanthropic providers also need to become better aligned to ensure that promising ideas are supported from the conceptual stage through scaled broad deployment.

By focusing on appropriate risk sharing and mitigation, international financial institutions and the donor community can also better unlock private sector investment to do what it does best: finance commercially viable investments and bring to the table the sector’s know-how and openness to innovation. Scarce public and concessional resources can then be freed up to focus on where they are most needed.

Donors also need to engage in clear-eyed cost-benefit analyses to determine a risk-adjusted economic (not just financial) rate of return and to guide allocation toward purposes that truly help those in greatest need. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has sometimes learned this lesson the hard way. One example is an investment we made to encourage commercial banks to lend to smallholder farmers. The risk sharing facility we created ultimately did not catalyse greater access to finance for smallholders. And once the facility was withdrawn, the costs to commercial banks to maintain lending were prohibitive and funding dropped.

Greater success is likely through co-operation between international finance institutions and donors. The Climate Investment Funds are a good example. A multibillion-dollar partnership of donors and development banks, the funds offer concessional financing to middle income countries for adoption of renewable energy technologies. This model could be used for scaling other promising innovations.

Another good recent example of such co-operation is the Gates Foundation and the Inter-American Development Bank working together to end malaria in Central America. The foundation’s grant money is blended with bank resources in a way that provides strong incentives for countries to implement effective programmes against malaria.

Partnerships are key. At the Gates Foundation, we are ready to partner with governments and the international finance community for the benefit of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the world. Together, we can accelerate pro-poor innovation for developing countries.