Chapter 3. Institutional foundations for a sound digital government ecosystem

This chapter identifies and analyses the progress of African Portuguese-Speaking Countries and Timor-Leste (PALOP-TL) countries in establishing the institutional foundations needed to support digital government. Using the OECD Council Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies as a frame of reference, and taking into account the constraints and opportunities of employing digital technologies to enable core government functions, this chapter begins by considering the nature and quality of the policy frameworks adopted for digital government, before reviewing the mechanisms for institutional leadership and co-ordination, policy levers, and the key enablers that could strengthen policy implementation. The last section is dedicated to the digital skills panorama in the public sector of PALOP-TL countries. The chapter makes several concluding observations and recommendations on next steps for PALOP-TL countries.

Policy frameworks for digital government

The diverse experiences of PALOP-TL countries show that different pathways can be followed to govern the digital transformation of the public sector. There is no one-size fits all approach. From the institutional framework that supports digital government to stakeholder engagement, co-ordination and policy levers, the ability of each country to lead the digital transformation of the public sector will depend on the specificities of its institutional and governance ecosystem. In line with the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014), Figure 3.1 illustrates several dimensions that contribute to the analytical framework underlying this report.

This section looks at what is often considered the starting point for the digital transformation of the public sector: the design and implementation of a digital government strategy.

Digital government strategies constitute the blueprints for a country’s pathway to digital government. These strategies serve to harmonise and align policy objectives across different sectors of government to define a coherent, sequenced set of policy and operational actions, and to mobilise resources for inter-governmental policy implementation (see Box 3.1). Strategies can also serve to define the necessary governance mechanisms to support coherent and sustainable policy actions, in a manner that can be effectively supported by digital government stakeholders.

E-government strategies should answer at least three questions:

-

What? Objective of the strategy

-

Why? Social and economic impact of the strategy

-

How? Principals and strategic action of e-Government

It could also answer other questions:

-

When? Timeframe

-

Who? Organisations/responsibilities

-

How much? Fund needed for the implementation

Source: Ibledi (2017), Guidelines for the formulation of e-government strategies, ESCWA, Beirut, http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/unpan/unpan032960.pdf.

In the PALOP-TL region, five out of the six countries have adopted a digital government strategy (see Figure 3.2), reflecting both a government commitment to drive the digitalisation of their public sectors, and the tailor-made digital government ambitions of each country.

However, while virtually all PALOP-TL countries have developed digital government strategies, the nature and content of these strategies in terms of strategic focus, policy priorities, tasks or activities and monitoring mechanisms vary considerably from country to country (see Table 3.1). These varying strategies have yielded different dividends in terms of policy coherence, co-ordination, resourcing and action. The implementation period initially envisaged by the vast majority of these strategic instruments has already come to an end (Cabo Verde and Mozambique, 2010; Sao Tome and Principe, 2013; Angola, 2017), with an extension or update of these strategies now required, and already envisaged in many cases.

The design and development of a strategy and/or an action plan is an opportunity to involve public, private and civil society stakeholders, and to crowd source the objectives to be achieved and policy actions to be undertaken by the government. The inclusive design and development of these policies can serve to generate consensus among different policy agents, promoting co-ownership and a sense of shared responsibility for the projects and initiatives envisaged. It also enables synergies to be identified and adopted between existing strategies or actions (see Section 4.1).

Digital government strategies in the broader framework of information society policies

Experience has shown that designing strategic plans within the broader context of information society strategies (and national development plans) can enhance coherence with relevant government policy priorities, such as telecommunication infrastructure, Internet accessibility, digital literacy and digital inclusion. In light of this body of learning, e-government strategies can be grouped into two main types in the PALOP-TL region: 1) those created under the umbrella of broader information society policies; and 2) those that only establish a vision and lines of action in the area of digital government.

Angola and Cabo Verde have followed the first model, and both countries have developed e-government strategies1 within the broader context of their information society strategies, enabling the alignment of their e-government priorities – including interoperability, shared services and electronic democracy – with relevant sectoral plans.

Contrasting with Angola and Cape Verde, the Government of Mozambique has decided to adopt an Electronic Government Strategy (Estratégia de Governo Eletrónico) (Governo de Moçambique, 2006) that is fully aligned with the national development plan and national public sector reform strategies (although not an information society policy), thus ensuring the coherence and alignment of several sectoral policies (e.g. energy, telecommunications, transport and urban planning) and institutional players, and facilitating the attraction of international donor funding. In addition, the strategy explicitly aims to ensure coherence with the ICT Policy (from 2000) and the IT policy implementation strategy (Estratégia de Implementação da Política de Informática), approved in 200223.

In Sao Tome and Principe, the national e-government strategy was drafted in 2010, with the ambition of creating and implementing an information society in the country. It was designed in the form of a "project" with clearly defined objectives, results and activities, and a detailed implementation schedule and budget. In Timor-Leste, the digital government strategy is an integral part of the National Policy for ICT (Política Nacional para as Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicações), approved in February 2017 (and in force until 2019), with the strategic focus outlined in Table 3.1.

As indicated in Table 3.1 above, there is still no digital government strategy in place in Guinea-Bissau. However, during the fact-finding mission that preceded this review, the government representatives of Guinea-Bissau underlined that the development of a strategy for digital government was a short-term priority. In fact, during the drafting of the current review, the National Regulatory Authority for ICT (ARN) (Autoridade Reguladora Nacional), supervised by the Ministry of Telecommunications, was working on the formulation of a digital government strategy4. A consensus could not be reached on the legitimacy of the process of strategy formulation, considering that the responsibility for the co-ordination of the digital government policy has been legally attributed to CEVATEGE – Center for the Technological Valorization and Electronic Governance (Centro de Valorização Tecnológica e Governação Electrónica) (see Section 3.2)5.

Assessing digital government strategies in PALOP-TL countries

The alignment of the digital government strategies with the broader framework of the national development plans, public sector reforms and/or information society policies plays a significant role in PALOP-TL countries. Some digital government strategies pay particular attention to investment in telecommunication networks (Timor-Leste) as a measure to promote digital inclusion. In other countries, actions have been specifically planned and targeted to promote digital literacy and to provide public Internet access points, especially for the most disadvantaged groups and regions (Angola and Cabo Verde). The thematic areas covered by each strategy, and how actions are monitored, evaluated and budgeted, also significantly vary. Nevertheless, the evident ingredients of success across these digital government strategies are feasible with measurable action plans that are tied to carefully managed targets, budgets and investments, and that are also aligned with national level ICT sectoral investments (see Table 3.2).

Digital government is not a new policy for PALOP-TL countries. With the exception of Guinea-Bissau, which has not yet approved a strategy for this policy area, and Timor-Leste, which only recently adopted one, each of the four other PALOP-TL countries have had e-government/digital government strategies in place for a decade or more6. Accordingly, the opportunity exists to create second generation strategies that are better aligned with, and serve to enhance, the countries’ current achievements on digital government. These strategies could serve several headline objectives, such as tackling the inequalities produced by the digital divide or enabling countries to leapfrog stages of development (through enhanced public services delivery, digital innovation etc.), by more effectively seizing the opportunities of the digital transformation and leveraging current technological trends (e.g. social media, blockchain, cloud computing etc.).

Institutional leadership and co-ordination

In developing countries, including PALOP-TL countries, leadership and institutional capabilities can serve to ‘’engender a shared vision, mobilise long-term commitment, integrate ICT opportunities and investments into development strategies, align complementary policies concerning competition and skills, and pursue partnerships with civil society and the private sector” (Hanna, 2017). In PALOP-TL countries, the choices made about the institutional frameworks to support the execution of digital government strategies have proven to be essential for ensuring political coherence and driving relevant stakeholders towards the achievement of common goals around the digital transformation of the public sector. To this end, there is no one-size fits all standard institutional model to be adopted or followed, as such decisions depend on the context of each country. Nevertheless, some main trends can be identified in the PALOP-TL region.

The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014) highlights several particular attributes of institutional leadership and co-ordination as important for sustained and coherent digital government, including: clearly established institutional roles and responsibilities, cross-cutting mechanisms of co-ordination, and oversight and management.

The OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies suggests that high level articulation and leadership is needed that brings together ministers or senior officials and assures broad co-ordination and oversight of the digital government strategy. Alongside high-level political engagement, operational and technical co-ordination is needed to deal with implementation challenges and bottlenecks. Taken together, these two levels of co-ordination can assure the coherence and sustainability of the decisions, initiatives and projects to be executed.

Source: OECD (2016), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

Each PALOP-TL country has designated an institution responsible for the leadership and co-ordination of the actions and decisions taken on the use of ICT in central government (see Figure 3.3).

The role of a leading institution is particularly important in guiding and co-ordinating transformation efforts, particularly between sectors and levels of government, and in promoting a shift from agency thinking and government-centered approaches to systemic thinking and citizen-led implementation policies and approaches. In PALOP-TL countries there is a great deal of variation in the institutional models adopted. Differences are readily seen in the positioning of the agencies responsible for ICT within the hierarchy of government, as well as in their mandate (see Table 3.3). For example, in Angola and Mozambique, sectoral ministries take the lead in the co-ordination of digital government strategies. By contrast, in other PALOP-TL countries, the co-ordinating agencies are subject to the tutelage of the Office of the Prime Minister or to the Ministry of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers.

For countries in the early stages of a development transition process, there is no “best practice” approach to institutional leadership and co-ordination. To be effective, these models should be tailored to fit the given political and institutional context. In PALOP-TL countries, different models are adopted. In more stable political contexts, strong sector ministries are taking the lead (e.g. Mozambique and Angola). Elsewhere, in contexts where political dynamics are less stable or fragmented and institutional capabilities remain in the early stages of development (such as Guinea Bissau or Timor-Leste), digital government is led by the highest levels of government. Both models bring opportunities and constraints.

Mapping the institutional framework in PALOP-TL countries

In PALOP-TL countries, the institutional framework for digital government agencies vary widely and can be analysed around four domains or parameters:

-

1. Leadership (centralised in the Office of the Prime Minister or Presidency of the Council of Ministers or led by a sectoral agency) and reporting models (guidance and oversight).

-

2. Mandate (ranging from standard setting, supervision and co-ordination to service provision, as in Cabo Verde).

-

3. Human, logistical and financial resources.

-

4. Agency tasks or functions (for example, the aggregation of implementation and regulatory functions in a single agency, or delegation of those functions across different agencies, as in the case of Mozambique).

In Angola, INFOSI is a product of the integration of the former National Center for Information Technologies (CNTI) and the Institute of Administrative Telecommunications (INATEL) in 2016. With an estimated 230 employees in central and provincial services, INFOSI leads several iconic digital government projects and initiatives: the State Private Network (see Section 4.2); the national public data centre; and Walking with ICT (Andando com as TIC), which makes wifi and digital training freely available, through a mobile rotating service, in remote areas of the country. INFOSI is also responsible for the definition of standards and guidelines (e.g. interoperability), which allows for more coherent digital government development across sectors and levels of government. To galvanise this function, INFOSI would benefit from developing model policy levers, such as budget thresholds and co-ordinated investments or business cases that could be used across the public sector (see Section 3.4).

In Cabo Verde, NOSI was created in 2003 as an operational and executive institution under the auspices of an Interministerial Commission for Innovation and Information Society (Comissão Interministerial para a Inovação e Sociedade de Informação) (Resolução n. 15/2003, de 7 de Julho) (see Section 3.3). NOSI is also the principal provider of digital services and products across public sector institutions, providing web design and platform development services, multimedia products, backup and software services and information storage. Today, NOSI has more than 200 employees dedicated to support the digitalisation of society, economy and public sector of Cabo Verde, and is widely considered a leading driver of strong digital government performance in Cabo Verde (see Chapter 17).

In 2014, NOSI became a public company (entidade pública empresarial) with administrative and financial autonomy (Decreto-Lei n. 13/2014). Under the supervision of the Prime Minister, NOSI is now under the economic and financial guidance of members of the government responsible for finance, ICT and public sector reform. Given the institution’s current role as regulator, co-ordinator of the digital government policy, and digital services provider, the OECD fact-finding mission concluded that a redefinition of its mandate and competencies might be prudent, in line with the “Cluster TIC- C@bo Verde Digital initiative”, approved by the Government of Cabo Verde in 2014 (see Section 3.4).

In Guinea Bissau, CEVATEGE was created in 2014 to co-ordinate digital government development efforts in the country. The institution is responsible for the government portal and for managing the national public domain (gov.gw). Although CEVATEGE has aggregated some level of digital government skill and expertise in-house, it has limited political or policy leverage regarding other public sector organisations, and has significant human, logistical and financial resource constraints, with no direct budget allocation. Reinforcement of CEVTEGE leadership and resources (both human and financial), and some level of investment in the development of policy levers for digital government (e.g. model business cases, procurement templates etc.), might enable the agency to better co-ordinate the country’s efforts towards digital government (see Section 3.4).

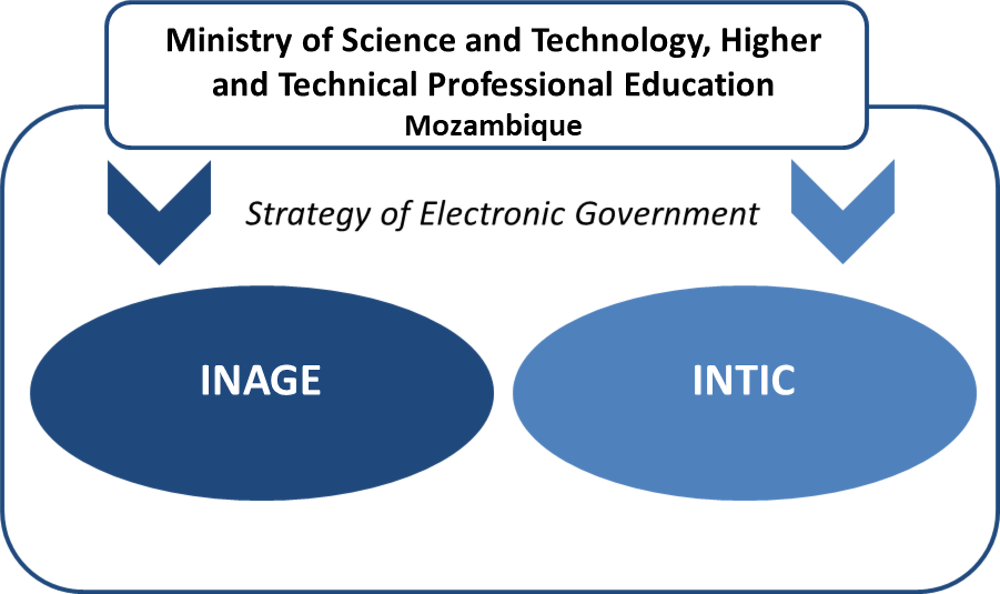

Created in November 2017 (Decreto 61/2017, de 6 de Novembro), INAGE in Mozambique leads digital government projects and initiatives, such as the management of the government's electronic network (GovNET), government data centres and the interoperability system8. Under this new policy framework (see Figure 3.7), the National Institute of Information and Communication Technologies (INTIC or Instituto Nacional de Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação), also under the Ministry of Science and Technology, Higher and Technical Professional Education, has a role in defining digital government policy and in supervising and regulating its implementation9. INTIC plays the role of the regulator, and INAGE is the national implementing agency for digital government. Given the recent creation of this new institutional framework, it is too early to gauge the success or failure of this strategic option.

In Sao Tome and Principe, INIC (created in 2008) has varying responsibilities, including the management of the data centre, support for digital technologies management among different institutions of government, and the development of a fibre optic backbone to enable efficient communication infrastructure across the public sector. The lack of resources does, however, constitute an obstacle for the development of INIC’s mission and its mandate or authority, and the allocation of human and financial resource allocation to INIC would need to be significantly strengthened for it to play a meaningful role in digital government. INIC could also be responsible for overseeing ICT investment in the public sector, thus improving the coherence and sustainability of ICT projects across the different sectors of the government.

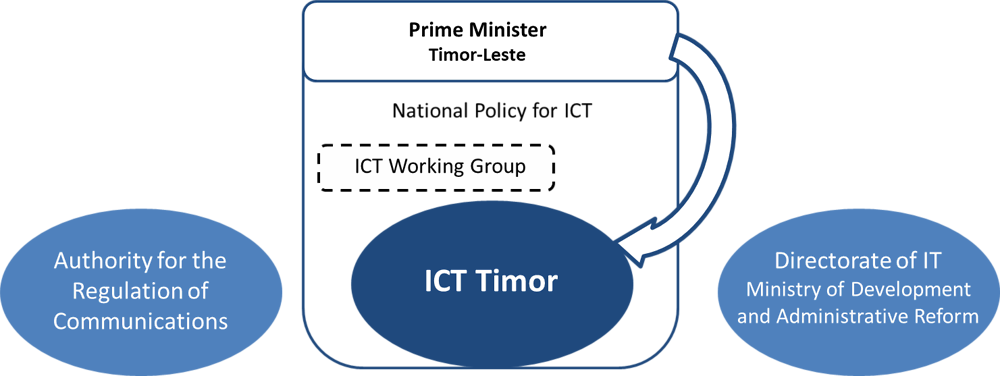

In Timor-Leste, besides the newly created public entity for digital government development - TIC Timor10 - the Directorate of IT (Direcção de Tecnologias da Informação)11 and the Authority for the Regulation of Communications (Autoridade Reguladora das Comunicações) have important functions, including the procurement and installation of a fibre optic network, and maintenance of a communication system between the government and the municipalities. It would be important for the Government of Timor-Leste to clarify the different roles performed by TIC Timor, by the Directorate of IT and by the Authority for the Regulation of Communications, to ensure that the current model of institutional governance does not cause further fragmentation of the sector.

Assessing the effectiveness of governance models in the PALOP-TL region

The presence of hybrid institutional arrangements for digital government development in each of the six PALOP-TL countries signals that there is no single model or approach for driving the digitalisation of the public sector. What works well in one country may not work well elsewhere. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify some common elements – including the mandate assigned to e-government agencies and the models of leadership and learning – that have contributed to improved digital government outcomes for PALOP-TL countries.

Appraising the mandates assigned to digital government agencies

The hybrid mandates of NOSI in Cabo Verde and INFOSI in Angola have enabled robust operational capacities, in large part due to political, human and financial benefits that have subsequently accrued to the relevant development agency. Both agencies are responsible for a diverse set of functions, ranging from the design and execution of digital government policies, to the provision of services and, to a certain extent, the definition of the technical standards and guidelines on ICT investment across the administration of government. Although ambitious, the exercise of such a mandate has the advantage of rapidly accelerating government efforts towards digital government, helping to disseminate the vision of political leadership in a clear and focused way. It is also the case, however, particularly in Cabo Verde, that the broad scope of NOSI’s mandate has generated some resistance from the private sector. NOSI is in a clearly dominant market position as it provides digital services across the public sector and limits the access of private companies to the ICT domestic market unless they participate in the public tenders launched and managed by NOSI itself. Despite this, the hybrid institutional models of Angola and Cabo Verde stand out as potential examples for other PALOP-TL countries, particularly those in the early stages of implementing their digital government strategies, such as Timor-Leste and Guinea-Bissau. This approach has demonstrated that the concentration of policy decision making, standard setting, financial resources and the development of ICT skills in a single government agency can boost digital transformation across the public sector.

It is too early to gauge the relative potential for INAGE in Mozambique and TIC Timor in Timor-Leste to effectively lead digital government activities across government. In Mozambique, the two public agencies recently created (INAGE and INTIC) could provide valuable lessons on how best to avoid any potential conflicts of interest between digital government agencies, ICT regulators and national telecommunications regulators in PALOP-TL countries. By contrast, the newly created digital government agency in Timor-Leste will be dependent on the government's commitment to the digital agenda and to its efforts to avoid the fragmentation of institutional responsibilities in this sector.

Neither INIC in Sao Tome and Principe or CEVATEGE in Guinea-Bissau are operating at desirable levels of efficiency and effectiveness, partly due to the lack of human and financial resources allocated to them.

Setting the models of leadership and tutelage

In terms of leadership and supervision, two approaches are evident: either the government creates specialised agencies (such as INFOSI or INAGE), which report to the sectoral ministries (Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Technologies in Angola, and Ministry of Science and Technology, Higher and Professional Technical Education in Mozambique); or e-government agencies retain some level of autonomy (NOSI, CEVATEGE, INIC and TIC Timor) but remain subject to the direct oversight of the Office of the Prime Minister, or the Minister for the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. In Cabo Verde, NOSI functions under the auspices of an Inter-ministerial Commission, which ensures political coherence around the digital agenda.

In theory, the second model of leadership and supervision should more readily overcome institutional silos. In the case of Cabo Verde, the proximity of NOSI to the Prime Minister's office was particularly important in the years following its creation as it allowed the digital transformation to be adopted as a whole of government mission and enabled NOSI to overcome diverse political, legislative and technical constraints. By contrast, in Angola and Mozambique the dissemination and co-ordinated implementation of digital government strategies by all government ministries and agencies depends to a large extent on the technical capacity and political weight that the sectoral minister carries regarding other members of the government. The extent to which the government interprets the digital agenda as a national imperative is also relevant. However, even in countries where the government intends to lead the digital agenda at the highest level, there are cases in which the leadership and authority appears fragmented and is challenged by political silos. In Timor-Leste, for instance, the recent TIC Timor, as a lead agency in the Office of the Prime Minister, now operates in parallel to the Directorate of IT, which continues to play a leading role on digital government strategy through the Ministry of Development and Administrative Reform.

In some PALOP-TL countries, sectoral ministries, although limited in number, develop and lead their own action plans, often outside the formal leadership of the agencies co-ordinating digital government. Both Ministries of Finance in Angola and Mozambique, for example, procure their own ICT equipment (e.g. data centres), which contradicts centralised interoperability standards and procurement policies. Nevertheless, the adoption of these measures, although potentially divergent and uncoordinated, can allow for a rapid evolution in the provision of digital services to citizens and companies, and could serve as good practice examples for other sectors of government.

Identifying additional constraints

Based on the assessment above, the following policy issues emerged as potential constraints to the foundations for effective digital government:

-

Leadership de jure vs de facto – Guinea-Bissau and Timor-Leste demonstrate the risks of proliferating government institutions with competing responsibilities for digital government12, as this can serve to undermine the leadership, authority and coherence among responsible agencies. In the absence of powerful leading and co-ordinating institutions, digital silos replicate the institutional silos, and pilots and digital platforms proliferate without sharing (Hanna, 2016).

-

Regulation vs implementation – Cabo Verde reflects the potential tension that exists when co-ordinating units assume different and incompatible functions (e.g. acting both as regulator and service provider). In the case of Cabo Verde, the effective implementation of the “Cluster TIC - C@bo Verde Digital initiative” should bring some clarity to the institutional framework in the country (but this is not a problem unique to Cabo Verde, and often arises or has the potential to arise elsewhere).

-

Shared services vs siloed efforts – the proliferation of ICT units in the line ministries (e.g. Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Justice) can undermine a coherent and co-ordinated approach to digital government. Strong leading institutions, with the authority and resources needed, can minimise this effect, promoting synergies and shared services to support collaborative approaches to digital government in partnership with other public sector organisations.

Mechanisms of co-ordination and culture of co-operation

Effective institutional co-ordination is central to promoting consensus and inter-agency linkages for digital government. It also enables the shared definition of standards and corporate acceptance of policy levers to secure coherent digital government policies (OECD, 2017a). Given the complex, cross-cutting and rapidly evolving nature of digital trends, appropriate mechanisms of co-ordination are productive means by which to secure multi-stakeholder engagement, alignment of sectoral decisions with the overarching objectives of digital government policies, and coherence and sustainability of strategic initiatives. Policy co-ordination mechanisms, including, for example, regular information and data exchange or inter-agency monitoring and reporting, also enable better monitoring and serve to inform policy and decision makers about the progress and impact of digital government projects across different sectors and levels of government. The promotion of a coherent and sustainable digital transformation of PALOP-TL public sectors, which is a phenomenon horizontal by nature, will require prioritising the effective use of policy co-ordination mechanisms to sustain the necessary shift from an agency-thinking to a system-thinking approach across the countries.

The extent to which this has begun to occur varies across PALOP-TL countries, with Cabo Verde, and to a lesser extent Mozambique and Angola, making more progress than others. Several potentially useful mechanisms of co-ordination exist on paper but are not yet operating in practice, including, for example: the Council for Information Technologies (Conselho para as Tecnologias da Informação) in Angola, the Strategic Council of the ICT cluster in Cabo Verde and the ICT Working Group in Timor-Leste. These lacunae suggest that either these institutions were overreached and not yet needed, or that they do not have the authority, legitimacy and resources to function as intended.

Policy levers to streamline digital technology investment

The existence of a national digital government strategy (Section 3.1), a lead institution (Section 3.2) and institutional mechanisms of co-ordination (Section 3.3) are important building blocks for effective digital government. However, governments are also encouraged to adopt policy levers, such as business cases, project management models, protocols or standards for commissioning ICT, and budget thresholds, to drive coherent policy implementation across sectors and levels of government (see Figure 3.10). The development of institutional tools or policy levers to plan and prepare digital initiatives or projects can assist governments to prioritise policy actions, and make cost-benefit analyses of public investments effective13. It is also an effective means to ensure the efficiency, effectiveness and alignment of procurement activities, avoiding gaps and overlaps that can result from agency-driven approaches14.

In line with the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014) and the work developed by the OECD Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders), the six policy levers outlined in Table 3.4 are recommended as constructive tools for smarter and more sustainable digital government policies.

In PALOP-TL countries, some of the institutions responsible for co-ordinating digital government policies have adopted relatively structured approaches or mechanisms to optimise the planning, preparation and implementation of investments in digital technologies across sectors:

-

In Angola, the Ministry of Planning and Territorial Development is responsible for overseeing public sector investments, and regularly asks the opinion of INFOSI before approving digital technology investments across different sectors of the government. Although this procedure could be done in a more institutionalised way, it allows INFOSI to secure its digital government co-ordination role on large and/or strategic digital technologies investments being made across the Angolan public sector.

-

In Cabo Verde, since NOSI co-ordinates digital government policy and acts as the main service provider of digital technology services for the country’s public sector (e.g. management of ICT infrastructure, software development, data hosting in public datacentre), the institution plays an important role in optimising and ensuring the coherence of digital technology investments across the public sector. The management of the Private Technological Network of the State (RTPE) and of the IGRP (Integrated Government Resources Planning) makes available more than 100 solutions to public entities and directly attributes to NOSI’s critical co-ordinating levers that allow strategic policy alignment and reinforced coherence across different sectors and levels of government.

-

In Mozambique, INAGE is responsible for “the approval of development projects, acquisition of information systems, applications, database and ICT equipment to provide Electronic Government services” (Secretariado do Conselho de Ministros, 2017). The new established institute in Mozambique is also responsible for the creation of an electronic communication platform of the government for all entities of the state, including the management and development of shared applications to be used by public institutions. In this sense, although INAGE was recently established, its mandate shows the willingness of the Government of Mozambique to ensure efficiency and coherence on digital technologies investments.

Despite these important achievements, almost across the board PALOP-TL countries continue to face ICT expenditure overlaps across different sectors of government (e.g. atomised procurement of hardware and software licences, multiplicity of IT assistance contracts), reflecting substantial inefficiencies and missed opportunities of co-operation.

The elementary examples of policy and operational measures currently adopted in PALOP-TL countries to improve the uptake and implementation of digital government do not necessarily constitute model or exemplary practices in these areas. Nevertheless, they do constitute useful first steps towards the creation of more robust policy levers, and an important means by which to begin turning policy into action. Given persistent and cross-cutting problems of effective institutional co-ordination and implementation of digital government policies in practice, each of these six countries would benefit to varying degrees from strengthening their focus on enabling policy levers.

Developing the key enablers

Shifting from silo-based ICT approaches, where each public agency focuses on its own opportunities and challenges, to system-thinking approaches, where public administration goals, priorities and ways of addressing them are understood as a whole, requires the development of technical key enablers that can contribute decisively to an integrated, coherent and sustainable digital government policy. Aligned with key recommendation 6 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014) – “Ensure coherent use of digital technologies across policy areas and levels of government” - and considering the PALOP-TL assessed context, the development of the following key enablers should be prioritised by the governments of the six countries:

-

1. Interoperability frameworks (see Section 2.5.2)

-

2. Data centres (see Section 2.5.2)

-

3. Digital identity (see Section 4.2)

The three key enablers demonstrate not only the opportunities, but also the challenges that PALOP-TL countries currently face in building digital government. Many improvements could still be made to scale up and optimise the benefits of existing key enablers, both in countries at earlier stages of development (such as Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe and Timor-Leste), and in the more developed PALOP-TL economies (Angola, Cabo Verde and Mozambique). As demonstrated by the examples above, the creation of key enablers is the first step towards creating a coherent and sustainable digital government, and continued and iterative progress in these areas is encouraged across the PALOP-TL region.

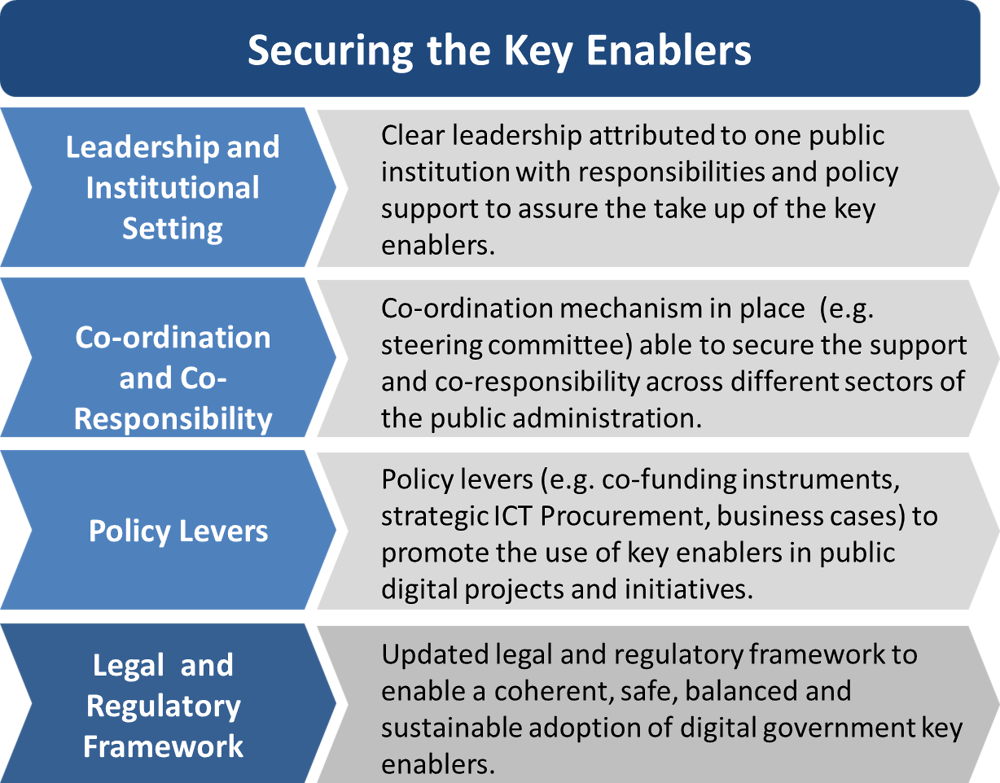

However, key enablers cannot work alone, and require an adequate legal and regulatory foundation to enable their adoption. The following dimensions are important pre-requisites or accompaniments to render their use effective (see Figure 3.12): leadership and institutional setting (see Section 3.1 and 3.2), co-ordination and co-responsibility (see Section 3.3), policy levers (see Section 3.4), and legal and regulatory framework.

Digital government policies require that diverse laws and regulations are in place to ensure citizen and company digital rights, institutionalise digital procedures and services, attribute legal value to specific digital instruments (e.g. digital signatures), promote digitally adapted procurement procedures, secure personal data protection, and guarantee the security of systems and transactions. Given the rapid pace of innovation in the digital technology sector, governments, particularly developing country governments, are often faced with the difficult task of keeping their legal and regulatory frameworks regularly updated in order to seize and address any obstacles to the digital transformation of their public sectors15. This often comes at the cost of enabling support for implementation or productive investment elsewhere, for example, around the establishment of administrative enablers, where much could be achieved to advance the digital transformation. During the six fact-finding missions to the PALOP-TL countries, the interviewed stakeholders often cited delays in the progress of legal/regulatory reform as a binding constraint in policy implementation in the country (e.g. interoperability, digital identity, ICT procurement).

Effective digital government across PALOP-TL countries will ultimately hinge on the simultaneous reform of legal, administrative and policy implementation approaches. PALOP-TL countries should maintain a functional balance between each of these elements of reform, as well as ensure that their legal and regulatory architecture is clearly informed by a combination of innovation and evidence-based learning and adaptation.

Digital skills for a sustainable digital government

The trends of digital transformation in peoples’ lives have important implications for their expectations of government and of the ecosystem in which they operate. However, it is important to understand the skillsets required to support digital transformation and enable a shift from e-government to digital government, as well as the role of civil servants in a digitally transformed public sector (OECD, forthcoming b).

Governments often face challenges in attracting and retaining digital talent in the public sector, and effectively balancing this approach with outsourced private solutions, commissioning, and public-private co-operation. Three particular types of skillsets are useful: digital user skills, digital professional skills and digital complementary skills (see Figure 3.13).

Stakeholders interviewed for this study identified these skillsets as necessary for enabling and sustaining a digital transformation in PALOP-TL countries and for reducing the digital divide that can result without these skills. However, none of these countries have dedicated strategies in place to attract public servants who are adequately trained in the use of ICT, or strategies that recognise and retain those skills through an ICT career structure.

A constructive first step towards building and retaining the skills needed in government would be to audit or take stock of existing digital skills, and assess these skills against the current and future administrative needs of the government. Such an assessment could serve as a blueprint or roadmap for recruiting talent. The opportunity also exists for governments across the PALOP-TL region to make use of the digital skills and expertise of entrepreneurs, vocational training and tertiary institutions in the public sector to enable and deepen digital skills both inside and outside of government for the benefit of end users. These connections could also play an important role in supporting the links to digital innovation and development.

Through strategic articulation with public Internet access initiatives, inclusive digital government actions can also improve access to digital services and serve to identify and engage segments of the population more vulnerable to information and digital exclusion.

References

CEVATEGE (2018), Linkedin profile, www.linkedin.com/company/cevatege/.

Decreto 61/2017, de 6 de Novembro, Cria o Instituto Nacional de Governo Electrónico (INAGE), Maputo, Moçambique.

Decreto-Lei n. 13/2014, de 25 de Fevereiro, Cria o Núcleo Operacional da Sociedade da Informação, Entidade Pública Empresarial, abreviadamente NOSI, EPE, Praia, Cabo Verde.

Decreto-Lei n. 19/2008, de 16 de Junho, Criação do Instituto de Inovação e Conhecimento, São Tomé, São Tomé e Príncipe.

Governo de Angola (2013a), Plano Nacional da Sociedade da Informação 2013-2017, www.governo.gov.ao/VerPublicacao.aspx?id=1191.

Governo de Angola (2013b), Plano Estratégico para a Governação Electrónica 2013-2017, www.governo.gov.ao/VerPublicacao.aspx?id=1192.

Governo de Cabo Verde (2005a), Programa Estratégico para a Sociedade de Informação, www.caboverde-info.com/eng/Economia-Moderna/Eixos-da-Economia/Tecnologias-de-Informacao-e-Comunicacao-TIC-Ecossistema-numerico-4D/PESI-Programa-Estrategico-para-a-Sociedade-de-Informacao.

Governo de Cabo Verde (2005b), Plano de Ação para a Governação Eletrónica, www.caboverde-info.com/Economia-Moderna/Eixos-da-Economia/Tecnologias-de-Informacao-e-Comunicacao-TIC-Ecossistema-numerico-4D/PAGE-Plano-de-Acao-para-a-Governacao-Eletronica.

Governo de Moçambique (2006), Estratégia de Governo Electrónico, www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/por/content/download/1430/12107/version/1/file/Estrategia+do+Governo+Electr%E2%80%94nico-Mocambique.pdf.

Hanna, N. (2017), Here's how developing countries can embrace the digital revolution, World Economic Forum, Geneva, www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/03/heres-how-developing-countries-can-embrace-the-digital-revolution.

Hanna, N. (2016), “Thinking about digital dividends”, Information Technologies & International Development, Vol. 12/3, pp. 25–30, http://itidjournal.org/index.php/itid/article/viewFile/1539/553.

Instituto de Inovação e Conhecimento (2010), Projecto STP EM REDE 2010-2013, São Tomé.

Ibledi, N. (2017), Guidelines for the formulation of e-government strategies, ESCWA, Beirut

Lei n. 3 /2017, de 9 de Janeiro, Lei de Transacções Electrónicas, Maputo, Moçambique.

OECD (2018a), Survey of the Study Promoting the Digital Transformation of African Portuguese-Speaking Countries and Timor-Leste, OECD, Paris.

OECD (forthcoming a), The Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: helping Governments Respond to the needs of Networked Societies, OECD, Paris.

OECD (forthcoming b), Issue Paper on “the Digital Government framework”, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2017a), Creating a Citizen-Driven Environment through good ICT Governance – The Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: Helping Governments respond to the needs of Networked Societies, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2017b), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

OECD (2016), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

OECD (2014), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/recommendation-on-digital-government-strategies.htm.

PASP PALOP-TL (2018), Instituto Nacional de Fomento para a Sociedade da Informação, Project’s Website, consulted on 11/05/2018, www.pasp-paloptl.org/pt/pagina/instituto-nacional-de-fomento-para-sociedade-da-informacao.

Resolução do Governo N.º 9/2017 de 15 de Fevereiro, Política Nacional para as Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicações (TIC) (2017 a 2019), Dili.

Resolução n. 15/2003, de 7 de Julho, Cria a Comissão Interministerial para a Inovacão e a Sociedade da Informação, Praia, Cabo Verde.

Secretariado do Conselho de Ministros (2017), Comunicado, October 3, Maputo, Mozambique. www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/por/content/download/8086/60989/version/1/file/COMUNICADO+DA+34.%C2%AA+SOCM-2017.pdf.

Tavares, Orlando (2016), Cabo Verde - Quinze Anos de Governação Eletrónica Integrada, Praia.

Notes

← 1. Angola has adopted a Strategic Plan for Electronic Governance, which incorporates a vision of ”governance focused on developing more oriented, relevant and accessible public services to citizens and businesses” (Governo de Angola, 2003a and 2003b); and the Action Plan for Electronic Government in Cabo Verde (Governo de Cabo Verde, 2005a and 2005b).

← 2. With the objective of improving the knowledge and expertise of human resources on ICT tools and the technological modernisation and innovation of public administration.

← 3. During the preparation of the current review, the Government of Mozambique was finalising the revision of the Electronic Government Strategy along with the above mentioned policies, which will give place to the “Mozambique Information Society Policy”. The new policy, discussed with public and private stakeholders during 2017, should be approved by the government in 2018. In doing so, Mozambique shall follow the good practice adopted by Angola and Cabo Verde, putting the digital government strategy under the broader umbrella of an information society policy.

← 4. The assignment was awarded to a private consultant, recruited by the Economic Union for Africa (UNECA).

← 5. Notwithstanding the above, there is a general consensus among stakeholders that the strategy should be developed within the broader framework of the national development plan (in particular axis 1, "Strengthening the democratic rule of law, promoting good governance and reforming the state institutions").

← 6. 2003 in Angola, 2005 in Cabo Verde, 2006 in Mozambique, 2010 in Sao Tome and Principe and 2017 in Timor-Leste.

← 7. A Framework for Integrated Government Resources Planning (IGRP), delivered through a Private Technological Network of the State (Rede Tecnológica Privativa do Estado) (RTPE), connects government institutions and makes available more than 100 solutions to public entities through a shared service approach to avoid the duplication of efforts and promote savings across the public sector.

← 8. The following objectives are attributed to the new institute: a) creation of an electronic communication platform of the government for all entities of the state; b) approval mechanism for the development of projects, acquisition of information systems, applications, database and ICT equipment to provide electronic government services; and c) ensure the management of the government’s electronic network (Secretariado do Conselho de Ministros, 2017).

← 9. Law 3/2017 on Electronic Transactions (9 January), attributes to INTIC the function of “regulating electronic transactions, electronic commerce and the electronic government”.

← 10. Government Resolution 9/2017 15 of February.

← 11. The Directorate of IT reports to the Ministry of Development and Administrative Reform.

← 12. CEVATEGE and ARN in Guinea Bissau and TIC Timor and the Directorate of IT and the Authority for the Regulation of Communications in Timor-Leste.

← 13. Different cost structures need to be considered (e.g. specialised human resources, specific hardware, development of tailored software, security tests, usability tests, load tests, legal consulting services) to address multiple contingencies (e.g. sector of application, profile of final users, expected demands, future technological evolution, national or international regulations) (OECD, 2017b).

← 14. Investments in digital technologies are becoming increasingly complex, and governments often have to manage in a context of significant budget and procurement constraints, rapidly evolving technology, together with rising expectations of transparency and collaboration on the part of private and civil society interests (OECD, 2016).

← 15. Key recommendation 12 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014) encourages OECD member countries and adherent countries to “ensure that general and sector-specific legal and regulatory frameworks allow digital opportunities to be seized” namely by “reviewing them as appropriate”.