Chapter 4. France: Social protection for the self-employed

This chapter discusses the ongoing efforts to integrate the social protection of self-employed workers into the general social protection system in France. Several autonomous schemes and a complex system of contribution rates and entitlements obscure the relationship between gross and net wages and hinder the mobility of workers across jobs and occupations. While there have been efforts to harmonise the social protection of self-employed workers and employees, differences in coverage and contribution rates remain. The social protection of employees and self-employed workers is also managed by diverse institutions which are imperfectly coordinated. This paper describes the contribution rates and the social protection of various forms of employment in France. It provides information about the different components of the social protection of self-employed people (the organisation of schemes and their financial architecture, membership of the schemes, contributions and benefits) and compares the situation of different kinds of self-employed workers with that of employees. The chapter also discusses a special unemployment scheme for performing artists and related occupations, the Intermittents du spectacle.

4.1. Introduction

In France, the social protection of employees is provided by the general social security system and by the public unemployment insurance scheme. Self-employed workers are covered by separate schemes. These schemes have been progressively integrated into the general social security system, but this convergence remains partial: self-employed workers pay lower contributions and have lower coverage than employees. This situation, which creates complexities, is a source of problems for the overall management of the social protection system. It also creates inequalities between self-employed workers and employees, and barriers to mobility between paid employment and self-employment. And this situation is becoming more problematic because current changes in forms of work and employment call into question the boundaries between employment and self-employment.

In order to shed light on this issue, this paper describes the contributions rates and the social protection of various forms of employment in France. It provides information about the different components of the social protection of self-employed people (the organisation of schemes and their financial architecture, membership of the schemes, contributions and benefits). It compares the situation of different kinds of self-employed workers with that of employees.

The paper shows that there have been various efforts to harmonise the social protection of self-employed workers and employees during the last three decades, starting from a situation in which the self-employed had significantly less social insurance coverage than employees. However, the systems are not fully harmonised. The social protection of employees and self-employed workers is managed by diverse institutions which are imperfectly coordinated. This is a source of complexity and a lack of transparency.

In particular, contribution rates for employees change according to the level of the wage, with different thresholds for different types of contributions. There are also different rates for self-employed workers, with thresholds depending on income, but these rates and thresholds are different from those of employees. The complexity of contribution rates, and the lack of clear distinction between contributory and non-contributory schemes make it difficult to compare the contributions and the social benefits of employees and self-employed workers at present. This situation represents a barrier to mobility between self-employment and dependent employment as it is difficult to figure out the relationship between gross income and net income, including social benefits, in each situation. This is also an obstacle to the convergence of the social protection of employees and self-employed workers.

This paper is organised as follows. Section 4.2 briefly presents the general architecture of the French social protection system, including the situation of self-employed workers within this system. Section 4.3 outlines the characteristics of self-employed workers. Section 4.4 highlights the social contributions paid by self-employed workers and compares them with those paid by wage earners. Section 4.5 outlines the social benefits available to self-employed workers, while the financial situation and the administrative organisation of the social protection schemes for self-employed workers are described in Section 4.6. Section 4.7 focuses on the situation of workers of the entertainment industry, who benefit from a special system called intermittents du spectacle. Section 4.8 summarises the main findings and makes proposals to improve the French social protection system.

4.2. An overview of the French social protection system

4.2.1. The general architecture of the social protection system

In France, social protection is provided by the general social security system, established in 1945, and by the public unemployment insurance scheme, created in 1958.

The general social security system aims to unify all forms of social insurance in France within a single fund, which is financed by a single-rate contribution and managed by the government with the participation of social partners. Functionally, social security assists people when they are confronted throughout their lives with different events or situations that can have a costly financial impact. Four branches are defined by the Social Security Code, each of which is intended to cover a type of risk, with their own methods of coverage and benefits:

-

1. The health branch (sickness, maternity, incapacity, death)

-

2. The occupational accidents and diseases branch

-

3. The old-age and retirement branch

-

4. The family branch (including disability, housing)

The unemployment insurance scheme was created by the social partners. This scheme is not linked to the general social security scheme but is run by an independent association (Unédic), which is managed by employer bodies and trade union organisations. It is compulsory for the majority of employers and employees in the private sector. The self-employed are not eligible for unemployment insurance.

4.2.2. A brief overview of the social protection situation of the self-employed

A short history

At the time of the creation of the general social security system in 1945, the self-employed opposed their integration into the main system. This was followed by a period of piecemeal integration of some professions and some risks, but not others.

Compulsory, but occupation-based and independently organised pension systems were established, and in the 1960s, the self-employed acquired health and accident insurance protection. However, because these schemes were not fully integrated with the general scheme and had lower contribution rates, the self-employed still received lower benefits, which led to concerns that the status would become less attractive. Demographic shifts within professions – such as the increase in the average age in the farming industry – led to infusions of government money into individual occupational schemes.

Since the late 1970s, the social protection treatment of the self-employed has been gradually aligned with the general system: Family benefits for the self-employed were incorporated into the general scheme in 1978; in-kind benefits from the health insurance were aligned to the general system in 2000, followed by sickness benefit payments in 2016. Also, the pension system has converged with the general system to some extent, especially for craftsmen and retail traders, but to a lesser degree for the liberal professions.

The current situation

The organisation of basic social protection for self-employed workers remains characterised by a plurality of schemes, the scope of which varies across professions.

Self-employed workers are covered by six basic compulsory schemes:

-

1. the system for farmers (managed by the social mutual agricultural – MSA);

-

2. the sickness insurance scheme for non-agricultural non-salaried workers, managed by the Régime Social des Indépendants (RSI), the social security agency for the self-employed;

-

3. the two pension schemes for craftsmen on the one hand and managers and traders on the other hand (managed by the RSI);

-

4. the basic pension scheme for the liberal professions, managed by the CNAVPL fund (Caisse nationale d’assurance vieillesse des professions libérales);

-

5. the basic pension scheme for lawyers, managed by the CNBF fund (Caisse nationale des barreaux français);

-

6. certain self-employed people are also covered by the general scheme for all or part of their social protection (for instance, doctors charging authorized fees and other liberal health care professionals).

Comparing the benefits available to employees in the general social security scheme with those available to self-employed workers, three main types of benefits can be distinguished:

-

1. Universal benefits that are not contingent on professional status by design, but which might still be less accessible to the self-employed in practice (family and housing benefits, basic health insurance, minimum retirement pension);

-

2. benefits provided by occupation-specific schemes, some of which are relatively harmonised between the self-employed and dependent workers, such as retirement benefits, while others differ quite substantially, as with replacement income in the event of sickness, maternity, paternity or disability;

-

3. coverage for risks that are uninsured or only insured on an optional basis for the self-employed (occupational accidents, complementary health and welfare benefits, unemployment or loss of income).

Individuals are assigned to a scheme once it is determined that they exercise an activity professionally and are not salaried employees. The nature of this activity – commercial, artisanal, industrial, liberal profession or agricultural – determines which scheme manages their contributions and entitlements. In case of disagreement between the social security agency and the worker, the civil courts decide.

This process raises several issues: first, the distinction between dependent employees and the self-employed is not simple in practice. The concept of legal subordination, derived from case law, is central in this respect: it describes a work relationship in which the employer has the power to issue orders and directives, to supervise their execution and to punish any infractions. A person who performs work on behalf of an employer in return for remuneration in a permanent legal subordination relationship is considered to be an employee. While self-employment is determined on the basis of material evidence – e.g. absence of an employment contract, registration in the Trade and Companies Register (Registre du Commerce et des Sociétés) – if there is found to be a relationship of permanent legal subordination, the person is treated as a dependent employee. In this case, a reclassification of the employment relationship leads to a change in its affiliation scheme and penalties for the employer.

Second, whether the activity is salaried or not, affiliation to a scheme presupposes that the activity is of a professional nature. A voluntary activity that does not offer remuneration in kind or in cash does not give rise to affiliation. The professional nature of the activity is established in a variety of ways. For the commercial, craft or liberal professions, affiliation is triggered by registration in professional registers and registers of firms via a centre de formalité des entreprises (CFE).

Third, the recognition of a self-employed activity results in affiliation to a scheme for self-employed people, which will receive the contributions paid and provide the associated benefits. However, there are numerous exceptions that may lead to independent workers (in particular, non-salaried managers of co-operatives or companies) being affiliated to the general scheme for wage earners. These exceptions make the social protection system more complicated.

4.3. The characteristics of self-employed workers

Self-employed workers are all affiliated to the social protection scheme for self-employed people, the Régime Social des Indépendants (RSI) for non-agricultural workers. A distinction can be made between traditional self-employed workers and micro-entrepreneurs. The micro-entrepreneur1 scheme, introduced in 2009, simplifies the process of setting up a business, as well as the payment of social contributions if business revenue remains below set thresholds (see Section 4.3). These are essentially individual contractors or managers of limited liability companies. In 2015, economically active2 micro-entrepreneurs accounted for 28% of self-employed workers.

4.3.1. The share of self-employment in total employment

Self-employed workers accounted for about 10.3% of total employment in 2015. Their share of total employment decreased until the early 2000s, falling from 12.8% in 1990 to 8.8% in 2002 (Figure 4.1). It began to increase from 2003 onwards, with an acceleration following the introduction of the micro-entrepreneur scheme in 2009, and reached a plateau of about 10.4% in 2013. Over the long term, it is the decline in agricultural employment, driven by strong productivity gains, but also by a greater propensity to work under the status of dependent employee, which explains the decline in self-employment.

From 1990 to the mid-2000s, a significant number of self-employed jobs were lost in the tertiary sector, particularly as a result of the shift in the retail sector and the accelerated development of large stores (Panel A, Figure 4.2). In the more recent period, it has been the relative dynamism of the creation of self-employed jobs in services, but also in the construction sector, which has led to a revival of non-wage employment. It has been driven by the creation of the micro-entrepreneur scheme in 2009, although some of the jobs created in this context have simply replaced traditional non-salaried jobs.

Panel B in Figure 4.2 shows that self-employment has accounted for a large share of job creation since the beginning of the 2000s, in contrast to the previous period. From 2001 to 2015, self-employment accounts for 34% of net job creation in all non-agricultural sectors. From 2009 to 2015, the creation of self-employed jobs was (nearly) twice as great as growth in paid employment. This important contribution of self-employment to job creation has also been observed in the United States since 2005.3

4.3.2. Sectors of activity of self-employed workers

For 89% of self-employed workers, self-employment is their main activity, with the rest deriving most of their earned income from paid employment.4 Half of the self-employed are concentrated in commerce and commercial crafts (21%), health care (17%) and construction (14%), whereas these sectors account for only one-third of private employees. There are also many self-employed workers in services: 13% work in specialised scientific and technical activities (legal professions, accounting, management consulting, architecture, engineering, advertising, design etc.) and 21% in services for individuals: catering, accommodation, artistic and recreational activities, teaching, hairdressing, beauty care or other personal care services. On the other hand, less than 5% of the self-employed work in industry (excluding commercial crafts), whereas the share of wage earners in industry is three times that level.

4.3.3. The strong income disparities among self-employed workers

Income disparities among the self-employed are much more pronounced than among dependent employees. In 2014, 10% of non-salaried workers (excluding micro-entrepreneurs) reported a zero income because they did not receive any benefits or professional income (ranging from 2% for health professionals to more than 20% for those working in real estate or arts and entertainment). Excluding those who had no income, one in ten received less than EUR 480 per month. This share is 2.5 times higher than that of private sector employees. One self-employed worker in four receives less than EUR 1 080 per month and half less than EUR 2 230. At the top of the remuneration scale, one in four self-employed workers receives more than EUR 4 320 per month and one in ten more than EUR 7 880. This amount is more than twice as high as that of paid employees. Non-store5 retailing generates the lowest revenues (EUR 1 040 per month on average), behind hairdressing and beauty care, artistic and recreational activities, taxis and other personal care services (EUR 1 330 to 1 410 monthly). Doctors and dentists receive the highest incomes (EUR 8 310), followed by the legal and accounting professions (EUR 7 630) and the pharmaceutical trade (EUR 7 480).

4.3.4. The number of micro-entrepreneurs

Since the creation of the micro-entrepreneur scheme in 2009, the presence of micro-entrepreneurs has expanded in many sectors of activity. They represent 65% of self-employed workers in the non-store retail trade, design, photography, translation and certain personal care services such as cosmetics. On the contrary, there are hardly any of them in sectors composed mainly of regulated professions which do not qualify for this status.

Economically active micro-entrepreneurs earned an average of EUR 410 per month in 2014, one-eighth of the average income of other self-employed. More than one in four earned less than EUR 70 per month, half less than EUR 240 and one in ten more than EUR 1 110. The low income of micro-entrepreneurs is partly due to the ceilings imposed on revenue to be eligible for the scheme, but also to the fact that it is often a supplementary activity: at the end of 2014, nearly one in three micro-entrepreneurs combined self-employment and dependent employment, compared with one in ten of other self-employed workers. The total earnings of those who combine self-employment and dependent employment reached EUR 2 100 per month in 2014, of which only 14% came from self-employment. Micro-entrepreneurs who did not engage in paid employment earned an average of EUR 460 per month. Among the regular self-employed, the total earned income of those who combined self-employment and dependent employment amounted to EUR 5 820 per month, of which almost half came from their self-employment. The parallel exercise of a wage-earning activity is very common for non-salaried workers in education, health care, and artistic and recreational activities.

4.4. The social contributions paid by self-employed workers

Any analysis of the social contributions of the self-employed and their comparison with that of wage earners is complicated by the fact that the self-employed can carry out their activities under different company structures. While craftsmen and retail traders can choose from a wide range of company legal forms, this is not the case for certain liberal professions: the legal and judicial professions, as well as most health professionals, cannot practice within the scope of a limited liability company (SARL in France). Only those who operate alone, who are not among the so-called “regulated” liberal professions or farmers, and whose income does not exceed a certain threshold can be micro-entrepreneurs.

Hence, the social security treatment of different types of self-employed people can vary considerably, and depends both on the sector and the profession that the self-employed person is active in, as well as their chosen form of self-employment. This section first describes the social contributions paid by craftsmen, traders and micro-entrepreneurs, leaving aside the liberal professions and the farmers.6 The social contributions of self-employed workers are then compared with those of dependent employees.

4.4.1. Contributions paid by craftsmen, traders and micro-entrepreneurs

Craftsmen and traders

Tax base

The contributions of self-employed workers are calculated on the basis of the professional income taken into account for the calculation of income tax, i.e. the profits of the firm or the remuneration of the head of the company. This calculation excludes any tax exemptions and includes dividends received if more than 10% of the share capital is held. It also incorporates the 10% flat-rate tax allowance for professional expenses.

For the first and second year of activity, the contributions are determined provisionally on a flat-rate basis. They are recalculated the following year, after the first tax declaration.

Contribution rates

Contributions are proportional to self-employment income. Each type of contribution is subject to a specific rate. Initially, contributions are calculated on a provisional basis. Then they are recalculated on the basis of the real income declared at the time of the self-employed person’s income declaration. At the beginning of the year, the first contributions are based on the income of two years earlier. In the course of the year, contributions are adjusted to take account of the previous year’s income and contributions adjustment.

If the entrepreneur makes a loss or their income is below the minimum income threshold, some of their contributions are set at a fixed minimum amount (Table 4.1). One annual minimum pension contribution counts as three contribution quarters for basic pension entitlement (160-172 contribution quarters are required to receive a basic pension, depending on the year of birth).

The compulsory contribution rates of artisans and traders whose income exceeds these thresholds are displayed in Table 4.2. The CSG social security contribution (contribution sociale généralisée) and the CRDS contribution to repayment of debt of the social security system (contribution au remboursement de la dette sociale) do not give entitlement to specific benefits but have been introduced to contribute to the financing and reduction of the debt of the social security system. They are levied on all earnings, including pensions. The contribution for vocational training gives the self-employed person a right to vocational training.

Unlike wage earners, the self-employed do not make contributions and are not covered for accidents at work, occupational diseases and unemployment risks. However, it is possible to take out voluntary insurance for these risks. The contributions are tax deductible, within a certain limit, as explained below, in Section 4.5.

Micro-entrepreneurs

The social contributions of micro-entrepreneurs are determined so as to ensure an equivalent level between the effective rate of social contributions paid and income tax for micro-entrepreneurs and artisans and traders. But micro-entrepreneurs benefit from a simplified system for calculating and paying compulsory contributions and social contributions. To be able to file as micro-entrepreneurs, their 2017 revenue was not allowed to exceed:

-

EUR 82 800 for the sale of goods, or for accommodation services, except for rental of furnished accommodation, which had a threshold of EUR 33 200.

-

EUR 33 200 for services in the industrial/commercial and non-commercial categories. The company is not subject to VAT (no billing of VAT or recovery of VAT on purchases). The micro-entrepreneur cannot deduct any costs (telephone, travel etc.).

Each month or each quarter, the micro-entrepreneurs must calculate and pay their social contributions based on their actual gross revenue. They pay a flat rate that includes all contributions related to compulsory social protection: health care, daily sickness benefit (for artisans and traders only), CSG, CRDS, family allowances, basic pension, complementary pension, incapacity and death.

There are three different rates depending on the field of activity of the micro-entrepreneur: 13.1% for purchase/resale of goods, sale of foodstuffs for consumption on site and accommodation services; 22.7% for commercial or craft services; 22.5% for liberal professions. In contrast to artisans and traders, micro-entrepreneurs do not have to pay minimum contributions.

Micro-entrepreneurs pay a contribution for vocational training, calculated as a percentage of revenue, which amounts to 0.10% for traders, 0.20% for professionals and service providers, and 0.30% for craftsmen.

4.4.2. Comparison of the total amount of contributions due for self-employed workers and employees

This section analyses the social charges levied on identical income profiles of regular self-employed workers (craftsmen and traders) and dependent employees. The amount paid by micro-entrepreneurs is in principle identical to that of artisans and traders, even though micro-entrepreneurs pay social contributions at a flat rate.7 The following therefore compares the situation of regular self-employed workers with that of employees, on the assumption that that the situations of micro-entrepreneurs and regular self-employed workers are similar.

Table 4.3 details the contributions charged for employees, making a distinction between employees’ and employers’ contributions. This table shows that the different contributions change depending on the wage level and also the status (executive versus non-executive) of the employee. Therefore, comparing the contributions paid by employees and by self-employed workers is not an easy task.

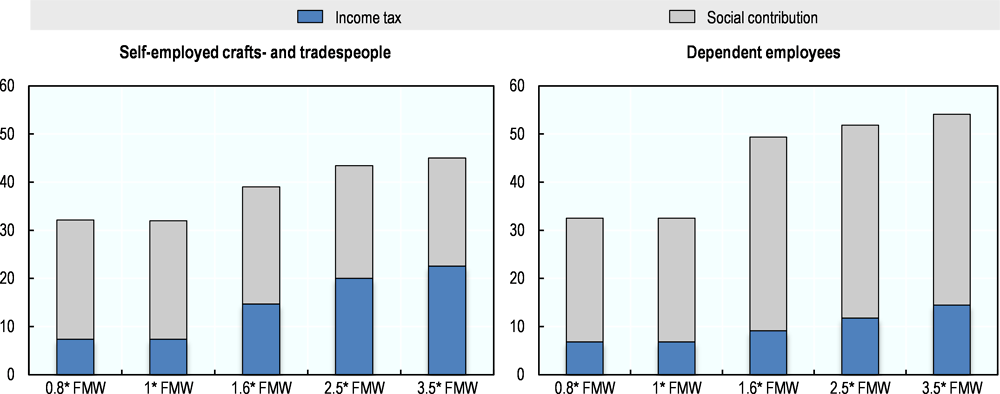

Another source of complexity arises from the fact that the tax base for income tax is not calculated in the same way for these two categories of workers. Moreover, there are significant reductions in contribution rates for employees whose hourly wage is less than 1.6 times the French minimum wage (known as the Smic). For this reason, Figure 4.3 presents several examples illustrating the situation of single full-time workers at five different income levels relative to the monthly French minimum wage.8 The following types of charges (including reductions for those on low wages) are taken into account when they apply: family allowances, health care, pensions, unemployment, occupational accident, training, transport, apprenticeship contributions, and income tax (including the flat-rate tax CSG and CRDS taxes).

The total tax wedge is almost identical for self-employed workers and dependent employees up to the minimum wage (see Figure 4.3). Up to this level, the share of gross income taken up by social contributions and income taxes is almost identical for these two categories of workers. Theoretically, the social contributions paid by employees are higher than for the self-employed, but this is cancelled out by deductions at low levels. These deductions become smaller as the wage rises and come to an end once income reaches 1.6 times the minimum wage. This means that employees pay more social contributions than self-employed workers when income is above the monthly minimum wage. The lower social contributions paid by self-employed workers above the minimum wage are partly offset by higher income tax. Nevertheless, the total tax wedge is about 10 percentage points higher for employees than for self-employed workers when the income is above the minimum wage.

4.5. Social benefits for self-employed workers

As mentioned in Section 4.2, three main types of coverage are available for self-employed workers: 1) universal coverage that is not connected to status; 2) coverage based on occupation-specific schemes; 3) coverage which is not insured or is only insured on a voluntary basis. This section covers these three types of coverage.

4.5.1. Universal coverage: family and housing benefits, basic health insurance

Family and housing benefits

For family benefits and basic health insurance, the coverage proposed by the social security system is now not linked to professional status: the rights are identical, regardless of the schemes that people are affiliated to. The amount of family and housing benefits is also not dependent on a person’s professional situation. It depends on the family configuration, the income level and whether the person owns or rents their home.

Basic health insurance

The payment of health care costs is guaranteed for everyone, either by virtue of their professional activity or their regular and stable residence in the country. The professional regimes only manage the provision of health care – entitlements do not vary across professional schemes. That is, the system is designed such that individuals transitioning between professions do not have to worry about a change in their or their dependents’ health care coverage.

Moreover, like the rest of the population, self-employed workers are eligible for aid for the acquisition of supplementary health coverage (ACS) and complementary universal health insurance (CMU-C).9

4.5.2. Specific benefits: old-age pensions, sickness, maternity, paternity or disability10

Old-age pensions

In France, all old-age pension regimes have two compulsory components: basic and supplementary pensions. All regimes know this duality. The pensions of craftsmen and traders are managed by the RSI.

The pension scheme for craftsmen and traders is now equivalent to that of private sector employees with respect to parameters such as the retirement age and the annual revaluation of pensions. However, the contribution bases and rates continue to differ because the nature of self-employed income necessarily means that contribution bases are calculated differently and there are no employer contributions.

Sickness

Traders and craftsmen can be entitled to cash sickness benefits if they have been affiliated for more than a year and are up to date with their contributions for health insurance and daily sickness benefit.

The self-employed are entitled to a cash sickness benefit that provides the same basic replacement rate as employees, equal to 50% of their daily income, but:

-

their period for averaging earnings is longer (three years rather than three months);

-

they do not benefit from a higher replacement rate if they have dependent children, while dependent employees do;

-

they have a longer waiting period (seven rather than three days).

Self-employed workers (except micro-entrepreneurs) also have the option of paying a specific contribution to benefit from a minimum daily allowance of EUR 21 (in 2017).

Maternity and paternity

In-kind medical services related to pregnancy and childbirth are fully covered for all women, regardless of employment status.

Self-employed women are entitled to maternity benefits if their contributions were paid on time by the end of the previous year. A daily allowance is payable for up to 74 days, and 30 additional days may be added in the case of complications. The period for averaging earnings is the past three years. The daily allowance is EUR 54 if the annual income is above EUR 3 608 and just EUR 5 otherwise.

The situation is more favourable for dependent employees: if they have worked for at least 150 hours during the three months preceding the maternity leave, they receive their full salary payment up to a ceiling. Collective agreements however may stipulate continued payment of the full salary by the employer during the entire maternity leave. The leave period is 112 days for the first and second birth, and 182 days for subsequent births.

Employees and self-employed workers are granted 11 days’ paternity leave when a child is born. The daily allowance amounts to 79% of the daily wage for employees, with a minimum of EUR 9.30 and a maximum of EUR 85. The daily allowance for self-employed workers is EUR 50.

Disability

Like employees, self-employed workers can benefit from pensions for either total or partial disability. The pension for total disability is paid if the insured person is assessed by a doctor to be in a state of total and definitive disability and if access to employment is severely and permanently restricted. Similar rules and allowances apply to wage earners.

4.5.3. Optional coverage: occupational accidents, complementary health and welfare benefits, unemployment or loss of income

Occupational accidents and occupational diseases

Occupational accident and occupational disease coverage is restricted to employees or people working on behalf of an employer. This principle is founded on the idea of the subordination of the employee to the employer who has obligations and the means to reduce occupational risks. As a result, craftsmen and traders, as well as the liberal professions, are not subject to compulsory insurance for the risk of occupational accidents and occupational diseases.

The RSI does not cover its members for industrial accidents and occupational illnesses. However, it offers a health promotion and risk prevention programme (RSI Prévention Pro) that includes specially tailored and personalised medical support (a free medical appointment entirely dedicated to the avoidance of occupational hazards) as well as comprehensive information on the risks connected with different jobs and how to protect oneself. However, self-employed workers can apply for voluntary membership in the work accident and occupational illness insurance programme of the general scheme. The contribution rates are determined by the regional social insurance agencies, and are aligned, in principle, with those of employees belonging to similar professions.

The lack of compulsory coverage may pose a problem for self-employed workers who are exposed to occupational risks, for example in subcontracting or activities in construction or the delivery business In fact, the lack of occupational accident and occupational illness coverage is one of the most important reasons why self-employed workers appeal to courts to requalify their work relationships as employment relationships..11

Complementary health insurance

Since 1 January 2016 all private sector companies have to offer complementary health insurance which covers part of the expenditure on medical care and equipment (especially dental and glasses) not reimbursed by basic health insurance. The self-employed can take out such additional health insurance on a voluntary basis. In order to encourage the development of social protection for the self-employed, contributions to certain group insurance contracts, known as Madelin contracts, and certain optional supplementary pension schemes were made tax deductible. The Madelin Law (11 February 1994), allows business and traders (except micro-entrepreneurs) to deduct contributions for voluntary insurance for incapacity to work, disability and death, unemployment and health insurance from their taxes, up to a ceiling. The subsidy is similar to that for dependent employees. 12 In 2012, 94% of the self-employed were covered by a complementary health insurance, provided by private insurers, compared with 96.6% for private sector wage earners.13

Unemployment

For unemployment risks, coverage for self-employed workers is optional. However, they can deduct contributions to a loss-of-employment contract subscribed under the Madelin scheme from their taxable income.14 This insurance is supplied by private insurers, who define when a self-employed worker is “unemployed” for the purpose of their insurance plan in their contracts.15

The public unemployment insurance for private sector dependent employees provides two schemes for entrepreneurs who paid contributions when they were wage earners. Entrepreneurs have the choice between the two schemes and may benefit from both schemes in succession.

-

1. The aid for starting or taking over a business (ARCE) allows unemployed people starting a business to opt for the payment of a capital amount corresponding to 45% of the remaining entitlement to unemployment insurance benefits, which is in two instalments. To access this, applicants already have to have been granted another aid called ACCRE, which provides relief from social security contributions for unemployed people starting or taking over a business. ACCRE is only awarded after the authorities have examined the validity of the entrepreneur’s plan. The first half of the ARCE capital payment is made on the date on which all the required conditions are met. The second half is paid six months after the establishment of the company, provided that the beneficiary is still carrying on the activity. If the beneficiary ceases the activity for reasons beyond their control (for example, a natural disaster requiring them to close their business or abandon their project due to the impossibility of meeting their social and/or tax obligations), they may get monthly unemployment insurance benefits, up to the level of their remaining entitlement minus the amount of aid received. Some 40 900 people benefited from the ARCE in 2016 (out of a total of about 3.2 million recipients of unemployment insurance).16

-

2. Rather than a capital endowment, the person starting or taking over a company can choose to receive monthly unemployment benefits, minus 70% of the remuneration from their activity. The combination of unemployment insurance benefits and remuneration cannot exceed the former monthly reference salary (salary of the former activity on which the unemployment benefit rights are opened). According to Unédic, in the second quarter of 2015, there were on average 44 760 unemployment benefit recipients who simultaneously had a self-employed activity.

The two previous sections have shown that for the rights of a universal nature, such as health care costs or family benefits, the self-employed regimes have been integrated into the general social security scheme. For rights of a more contributory nature (pensions, cash benefits), acquired rights are generally slightly lower for the self-employed, due to (overall) lower contributions. For certain other aspects of social protection, self-employed workers have chosen not to put in place a collective protective system (unemployment, work accident, incapacity and death). In these areas, employees benefit from better social protection than the self-employed, with higher compulsory contributions. Beyond these differences, the main weakness of the system is its complexity due to the diversity of rules for contributions and benefits. This diversity points to a lack of transparency. Moreover, the lack of distinction between contributory and non-contributory schemes make it very difficult to establish the relation between the contributions and the benefits, both for employees and self-employed workers.

4.6. The financial situation and management of the social security regime for self-employed workers

4.6.1. The governance and financial situation of the RSI

The social security scheme for artisans, traders and micro-entrepreneurs is managed by the RSI (Régime Social des Indépendants) created in 2006. It is a financially autonomous, French private-law body whose mission is to provide compulsory social protection for self-employed people. It is administered by representatives of self-employed workers.

In an effort to simplify the administration of social protection for the self-employed, the RSI gained sole responsibility for the social protection of craftsmen and traders in 2008. The RSI does not collect social security contributions, but relies on the URSSAF (Unions de recouvrement des cotisations de sécurité sociale et d’allocations familiales),17 a network of private bodies which also collects the social security contributions of dependent employees for the general social security system.

The RSI is organised in 30 funds: a national fund and 29 regional funds. The boards of directors of the national fund (50 directors) and the regional funds (24 to 36 members) are managed by elected representatives of the self-employed.

In 2016,18 the RSI managed the social insurance of 6.5 million active and retired self-employed workers and their dependents, 2.8 million contributors (37% traders, 35% artisans and 28% professionals), 4.6 million beneficiaries of health benefits and 2 million retirees.

RSI contribution rates and benefits are set by the general social insurance system rather than by the RSI itself. The demographic structure and income distribution of the RSI members create a structural deficit of around EUR 6 billion per year. This deficit is financed by a specific tax (the C3S tax)19 and by transfers from other funds based on compensation mechanisms that take account of differences in their demographic structures.

The creation of the RSI in 2006 was intended to unify the management of specific schemes. The aim was to limit management costs and improve the quality of benefits for self-employed workers. However, since its inception, the RSI has suffered serious malfunctions, documented by several reports.20

The first stage of the reform establishing the RSI was to merge the national sickness insurance fund for self-employed workers (Canam) and the separate fund for the old-age pensions of traders and artisans (Cancava). This merger made it possible to significantly reduce the number of administrative procedures and declarations of contributions for affiliates. The number of funds decreased from 90 to 30, and the number of directors was reduced by two-thirds. This first aspect of the reform did not raise any particular difficulties.

The second stage of the reform was to entrust the URSSAF network, which already handled the self-employed’s contributions for family allowances and CSG and CRDS payments, with the collection of all their social security contributions. The RSI did not have the capacity, particularly in terms of IT resources, to ensure the collection of these contributions, but the RSI administrators nevertheless endeavoured to partly hold on to this role. However, the management of contributions and benefits for the self-employed requires permanent information flows between the RSI and the URSSAF. This integration has resulted in major malfunctions, including insufficient collection of contributions, erroneous recoveries and unpaid benefits to insured workers.

The latest report on the RSI, released in 2015,21 proposed a package of measures to improve the coverage of self-employed workers, by bringing it closer to that of employees, and to make the management of the RSI more effective, while maintaining its autonomy. However, the programme of the president of the French republic elected in 2017 does not follow the conclusions of this report: it schedules a merger of the RSI with the general social security scheme. But the managers of the RSI are opposed to this development, arguing that the URSSAF will not be able to deal with the specific situation of the self-employed.

All in all, this section has shown that the system of social protection lacks transparency and homogeneity. Its main weaknesses are the absence of a unified governance of the different schemes for all workers, whether employed or self-employed, the complexity and heterogeneity of rules for contributions and benefits, and the lack of distinction between the contributory and the non-contributory schemes.

4.7. The specific situation of the “intermittents du spectacle”

The productions of entertainment companies are often by nature of limited duration, which leads them to contract with artists, technicians and workers for defined periods. They may hire an artist or a technician, as part of a production, for a contract of one day or more. France has created an original system for artists and technicians in the entertainment industry, called intermittents du spectacle (intermittent performers). They are employees and benefit as such from the social security system for employees. But they are eligible for a specific unemployment insurance scheme that takes account of their particular situation, which involves a succession of fixed-term contracts and alternating periods of employment and unemployment.

This type of system was instituted in 1936 for technicians and filmmakers. It was integrated into the general unemployment insurance system (Unédic) in 1965 and progressively extended to audio technicians, the audio-visual sector and to performers and performing arts technicians.

This section presents the unemployment insurance system of the intermittents du spectacle and discusses the issues raised by this system.

4.7.1. The eligibility rules

Intermittent performers must belong to one of the following two categories:

-

1. Performing artists on a fixed-term contract;

-

2. Blue-collar workers or technicians working on a fixed-term contract, with both their occupations and their hiring firm’s activities listed in a collective agreement.

Fixed-term contracts under the intermittents scheme are more flexible than under standard French labour law.22 While standard temporary contracts may only be extended twice, there is no limit on the number of extensions under the intermittents scheme. There is also no waiting period between two fixed-term contracts, while labour law stipulates a waiting period of at least one-third of the contract duration.

To benefit from unemployment benefit the intermittent employee must have worked a certain number of hours in a given period. The minimum period is 507 hours (or 43 days if the contract stipulates days of work instead of hours, in which case one day is calculated as 12 hours) during the last 319 days for artists or the last 304 days for blue-collar workers or technicians.

The level of benefits is calculated at the time of registration on the basis of reported hours and reported earnings during the 12-month base period. The net replacement rate, calculated on the basis of the daily wage, is about 85% at the level of the minimum wage and 70% at twice the minimum wage. If claimants are totally unemployed throughout the period of their claim and receive unemployment benefits each month, the potential duration of benefits is 243 days (eight months). Intermittent workers claiming unemployment benefit are allowed to work, including with their previous employers. In this case, the level of unemployment benefit is reduced, and depends on the hours of work reported each month during the period of the claim. However, the benefits foregone in one month are not lost – they can be paid in a later month. The corresponding benefit transfers delay the potential benefit exhaustion date. At the exhaustion date, the eligibility condition is reassessed. If claimants have worked 507 hours over the 12-month period preceding the exhaustion date, they remain eligible for unemployment benefits.

By way of comparison, the general scheme for unemployment benefit requires 122 days of work or 610 hours of work in the last 28 months for those under 50 or 36 months for those aged 50 and over. The replacement ratio is similar to that of intermittent workers. One day of work provides entitlement for one day of unemployment benefit coverage with a maximum limit of 24 months for those under 50 or 36 months for those aged 50 and over. Like intermittent workers, workers claiming unemployment benefit in the general scheme are allowed to work, including with their previous employers.23 The level of unemployment benefit is reduced in the same way as for intermittent workers and the reduction in benefits similarly delays the potential benefit exhaustion date. At the exhaustion date, the eligibility condition is reassessed. If claimants fulfil the eligibility conditions described above, they remain eligible for unemployment benefit.

4.7.2. The issues raised by the “intermittents du spectacle” scheme

All in all, the intermittent scheme is very generous and provides little incentive to work beyond the minimum number of hours required to gain entitlement to unemployment benefit. It allows arts workers to combine earned income with unemployment benefits indefinitely, if they work at least two months over a ten-month period, so this scheme is very attractive for them.

The number of arts workers increased fivefold between 1980 and 2015 while the number of arts workers claiming unemployment benefit jumped from 7 000 to 113 000 (Figure 4.4). In 2015, about 40% of arts workers claimed unemployment benefit thanks to the intermittent scheme. Moreover, the Cour des comptes (2012a) stresses that a significant number of intermittent arts workers leave their work situation once they have acquired sufficient rights to be eligible for unemployment benefit, and only resume their activity once these rights are exhausted. This phenomenon is also fuelled by employers' practices. A large proportion of compensated unemployment spells are attributable to comings and goings within the same company. This recurrence suggests that many companies have adapted their workforce management to take advantage of the benefits provided by the unemployment insurance system.

Accordingly, arts workers cost more to the unemployment insurance system than other workers employed in unstable jobs who do not benefit from the intermittent scheme. In all unemployment insurance systems, the amount of unemployment benefit provided to unemployed workers previously on fixed-term contracts is larger than their unemployment insurance contributions. Nevertheless, according to the Cour des comptes (2012a), temporary agency workers receive 2.5 times more in allowances than they pay in contributions. This ratio increases to 3.6 for employees on fixed-term contracts and reaches 5.2 for intermittent arts workers. Financial transfers are clearly higher for intermittent arts workers than for other types of fixed-term contracts. The difference between the expenditure on benefits and contributions paid by arts workers amounted to about EUR 1 billion per year between 2007 and 2012.

The high cost of the intermittent schemes has led to many attempts at reforms by the social partners, who manage the unemployment insurance system. But the strong opposition of arts workers, who organise many demonstrations when their benefits are threatened, has prevented significant changes so far.

In order to reduce the financial cost of the scheme to the unemployment insurance system, in 2014 the government created a fund endowed with EUR 90 million every year (the FONPEPS, Fonds national pour l'emploi pérenne dans le spectacle), which provides bonuses to companies hiring arts workers. The bonus increases with the duration of the contract and reaches a maximum of EUR 28 000 for an open-ended contract.24 However, it is clear that this reform is not sufficient to significantly improve the financial situation of the intermittent scheme.

4.8. Conclusion

The previous sections show that various paths have been taken to foster the convergence of social protection of employees and self-employed workers. Nevertheless, social protection for self-employed workers remains different to that of employees in the following ways:

For rights of a universal nature, such as health care costs or family benefits, the self-employed regimes have been integrated into the general social security scheme. Contributions for self-employed people are higher than for those in paid employment because employers’ contributions for wage earners on low incomes benefit from exemptions financed from the central government budget, i.e. by all taxpayers. However, as self-employed workers pay less income tax than employees, the tax wedge of self-employed workers is roughly identical to that of employees at income levels below or equal to the minimum wage of a full-time worker, and is lower than that of employees at higher income levels.

For rights of a more contributory nature (pensions, cash benefits), acquired rights are generally lower for the self-employed, due to (overall) lower contributions, despite the financial integration of the branch pensions of craftsmen and traders and an effort to bring their contribution rates to the basic pension system closer to those of employees.

For certain other aspects of social protection, self-employed workers have chosen not to put in place a collective protective system (unemployment, work accident, incapacity and death). In these areas, employees benefit from better social protection than the self-employed, but also have higher compulsory contribution rates than the self-employed.

The intermittents du spectacle scheme provides generous unemployment insurance for workers in the entertainment industry, whose jobs are naturally unstable. But the cost of this system raises serious doubts about its sustainability and the possibility of extending it to other professions.

All in all, the social protection system lacks transparency and homogeneity, and these weaknesses make the system difficult to reform. On the one hand, the wide range of situations of the self-employed relative to that of employees is a real obstacle to merging the management of the social protection systems of the two groups. On the other hand, the convergence of the rules for contributions and benefits for employees and self-employed workers is difficult, in particular because the contributions of the self-employed are lower. A way to ensure this convergence could be to implement identical compulsory and optional contributions, with associated benefits, for employees and self-employed workers. But this would mean either increasing the compulsory contributions of the self-employed, who would be opposed to such a development, or lowering the compulsory contributions and associated benefits of employees. It is likely that the managers of the regimes receiving less income because of the drop in employees’ mandatory contributions would strongly oppose this.

But these difficulties have to be overcome. The core of the French social protection system is designed for the archetype of a full-time, permanent worker with a single employer. This means that it is not equipped to provide adequate insurance for the growing number of workers with non-standard forms of employment (temporary jobs, part-time jobs, self-employment). The rise in non-standard forms of employment, largely resulting from globalisation and technological progress, is a fundamental trend that is likely to continue and spread in the future. It is therefore essential to adapt social protection to this new environment. In particular, social protection should pool risks and facilitate the mobility of workers across all types of jobs to ensure the adaptability of the labour force. Past experience shows that this is not an easy task: the creation of the scheme providing unemployment insurance to artists and technicians in the entertainment industry, who alternate between frequent periods of employment and unemployment, has been very costly. Its generosity has attracted a large number of people in the entertainment industry. Once created, it has been difficult to reform due to the resistance of those enjoying its generous benefits. This failure indicates that the social protection system has to be adapted cautiously, by competent bodies, avoiding the creation of significant advantages to specific categories of workers or sectors. It is also important to avoid designing a system in which some categories of workers are subject to higher social contributions, because firms then have incentives to shift work to other workers, subject to lower social contributions but with less protection.

In these circumstances, the French social protection system should be improved by unifying the governance of the different schemes for all workers, whether employed or self-employed, and by making a clearer distinction between the contributory and the non-contributory schemes.

From a practical perspective,25 it is important to merge the schemes that cover the same risks for all workers by unifying the governance and accrual of entitlements in compulsory pension schemes and defining the set of health risks covered by universal social health care and refocusing optional insurance on health care that falls outside of this set.

Moreover, the architecture of social protection should be reorganized with a non-contributory section (family benefits, health insurance, fight against poverty, etc.) incorporated into the state budget and financed by taxation, and a contributory section (retirement pensions, unemployment insurance, daily sickness benefit allowances etc.) financed by social security contributions. The non-contributory and the contributory schemes should be homogeneous for employed and self-employed workers while some contributory schemes could be optional for both statuses.

References

Acoss, 2016, Les auto-entrepreneurs fin 2015, Acoss Stat n°235 - Juillet 2016.

Archambault, H. Combrexelle, J.D. Jean-Patrick Gille, J.P., (2015) , Batir un cadre stabilisé et sécurisé pour les intermittents du spectacle. Rapport au Premier Ministre.

Blandin, M.C and Blondin, M. (2013), Régime des intermittents : réformer pour pérenniser, , Sénat, Rapport d’Information, 23 December 2013.

Bozio, A. and Dormont, B. (2016), Governance of Social Protection: Transparency and Effectiveness, Les notes du conseil d’analyse économique, no 28, January 2016

Bulteau, S. and Verdier, F., (2015), Rapport de la Mission parlementaire sur le Régime Social des Indépendants (RSI), Rapport au Premier Ministre.

Cahuc, P. and Prost, C. (2015), Improving the Unemployment Insurance System in Order to Contain Employment Instability, Les notes du conseil d’analyse économique, n° 24, September 2015.

Cardoux, J.N and Godefroy, J.P. (2014), Rapport d’information fait au nom de la mission d'évaluation et de contrôle de la sécurité sociale et de la commission des affaires sociales sur le régime social des indépendants, Sénat.

Chauchard J.-P (2009), Les avatars du travail indépendant , Droit social, n°11.

Cour des Comptes, (2012), Rapport annuel sur le financement de la sécurité sociale en septembre 2012,

Cour des Comptes (2012a), Le régime des intermittents du spectacle : la persistance d’une dérive massive, Cour des comptes, Rapport public annuel 2012 – février 2012, pp. 369-393.

Cour des Comptes, (2016), Rapport annuel sur le financement de la sécurité sociale en septembre 2016.

DREES, (2016), La complémentaire santé : acteurs, bénéficiaires, garanties - édition 2016.

Haut Conseil du financement de la protection sociale, (2016), Rapport sur la protection sociale des non salariés et son financement.

Haut conseil pour l’avenir de l’assurance maladie, (2013), La généralisation de la couverture complémentaire en santé.

IGAS, (2016), Contribution au rapport au Parlement sur les aides fiscales et sociales à l’acquisition d’une complémentaire santé, rapport 2015-143R, avril 2016.

IGF-IGAS, (2013), Evaluation du régime de l’auto-entrepreneur, Rapport, avril 2013.

Insee, (2015), Emploi et revenus des indépendants Insee Références Édition 2015.

Insee (2016), Revenus d’activité des non-salariés en 2014, Hausse pour les indépendants « classiques », baisse pour les auto-entrepreneurs, Insee Première, n°1627, December.

Katz, L., Krueger, A., 2016, The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995-2015, NBER Working Paper No. 22667.

Menger, P.M. (2005), Les intermittents du spectacle. Sociologie d'une exception, Éditions de l'école des hautes études en sciences sociales, 2005.

Pole Emploi (2016) Intermittents du spectacle, Décret du 13 juillet 2016, September 2016.

RSI (2017), Rapport annuel 2016.

Unedic, (2017), Rapport d'activité 2016 : L'Assurance chômage en actions.

Notes

← 1. The auto-entrepreneur scheme allows an individual entrepreneur to declare the creation of his business in a simplified way, and to benefit from a specific system for determining social contributions (a flat rate as a percentage of turnover) and the micro-entreprise tax regime (exclusion from VAT and the calculation of taxable profit as turnover minus a flat-rate allowance for professional expenses, which varies depending on the type of activity). Since 19 December 2014, auto-entrepreneurs have been referred to as micro-entrepreneurs. Certain activities are excluded from the micro-entrepreneur regime, particularly activities relating to real estate VAT (transactions involving property dealers, developers or real estate agents, and transactions in the shares of real estate companies), and the leasing of commercial buildings, equipment and consumer durables.

← 2. A micro-entrepreneur is economically active if he/she has reported positive turnover in the year. Some 61.2% of micro-entrepreneurs were economically active in 2015 (Acoss, 2016).

← 3. Katz and Krueger (2016).

← 4. Insee (2016)

← 5. Retail sales via mail order, the Internet, direct sellers and vending machines.

← 6. This part relies mainly on the report of the Haut conseil de la sécurité sociale (2016) which presents the work of a special commission composed of representatives of the different administrations and stakeholders, and in particular the Direction de la sécurité sociale and the Direction de la législation fiscale.

← 7. This has been the case since 2013. Before 2013, micro-entrepreneurs benefited from lower social contributions, but the Finance Law of 2013, laid down the principle of such rates being determined in a way that ensured equivalence in the effective rates of social contributions paid and income tax for micro-entrepreneurs and artisans and traders (IGF-IGAS, 2013).

← 8. In 2017, the hourly minimum wage was set at EUR 9.76, which corresponds to a full-time monthly wage of EUR 1 480. It represents 64% of the median wage.

← 9. http://www.aide-complementaire-sante.info/comparatif-cmu-acs/

← 10. The information provided in this section has been retrieved from the web site https://www.rsi.fr for self-employed workers and from https://www.ameli.fr for employees. More details can be found on these sites.

← 11. Chauchard (2009).

← 12. Haut conseil pour l’avenir de l’assurance maladie, (2013), p 60.

← 13. DREES (2016), p 52.

← 14. Micro-entrepreneurs are not eligible for this deduction.

← 15. Haut conseil de la sécurité sociale (2016), p 289.

← 16. Unedic (2017).

← 17. The URSSAF (Unions de recouvrement des cotisations de sécurité sociale et d’allocations familiales) are private bodies entrusted with a public service mission, which consists of collecting employees’ and employers’ contributions to the general social security system as well as other bodies and institutions (the unemployment insurance scheme, the national housing fund, the old age solidarity fund, the supplementary pension schemes etc.).

← 18. RSI (2017).

← 19. Established in 1970, C3S (contribution sociale de solidarité des sociétés) is a turnover tax. The basis of the C3S is turnover minus EUR 19 million. The normal tax rate is 0.16% of turnover. The C3S contributes to the financing of pension schemes for artisans, traders and micro-entrepreneurs.

← 20. Bulteau and Verdier (2015), Cardoux and Godefroy (2014), Cour des Comptes (2012).

← 21. Bulteau and Verdier (2015).

← 22. More flexible, fixed-term contracts, called contrats d’usage, can also be used for some other activities, the list of which is set by decree, including hotels and restaurants, education, removals, leisure centres.

← 23. Cahuc and Prost (2015).

← 24. EUR 10 000 the first year, EUR 8 000 the second year, EUR 6 000 the third year and EUR 4 000 the fourth year if the wage is lower than three times the minimum wage.

← 25. See Bozio and Dormont (2016).