Chapter 7. Policy guidelines to improve the design of financial incentives to promote savings for retirement

This chapter provides eleven policy guidelines to help countries improve the design of their financial incentives to promote savings for retirement. It considers the different results discussed and examined in the previous chapters for arguing in support of each of the policy guidelines.

The purpose of this monograph has been to review how countries design financial incentives to promote savings for retirement and examine whether there is room for improvement. Given the fiscal cost that financial incentives entail to governments, it is important to verify whether they are effective tools to promote savings for retirement, taking into account different needs across different population subgroups.

Financial incentives covered in this monograph take two forms, tax incentives and non-tax incentives. Tax incentives come from a differential tax treatment applied to funded pension arrangements as compared to other savings vehicles. In all OECD countries, the tax regime applied to funded pension arrangements deviates from the “Taxed-Taxed-Exempt” (“TTE”) tax regime that usually applies to traditional forms of savings, and in which contributions are paid from after-tax earnings, the investment income generated by those savings is taxed and withdrawals are exempt from taxation. Half of the OECD countries apply the “Exempt-Exempt-Taxed” (“EET”) tax regime to retirement savings that exempts contributions and returns on investment from taxation, but taxes withdrawals.

Non-tax financial incentives are payments made by governments directly into the pension account of eligible individuals. They can take the form of matching contributions or fixed nominal subsidies. Government matching contributions are found in Australia, Austria, Chile, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Mexico, New Zealand, Turkey, the United States, Colombia and Croatia. Only five OECD countries use government fixed nominal subsidies to promote private pensions: Chile, Germany, Lithuania, Mexico and Turkey.

This chapter provides eleven policy guidelines to assist countries to improve the design of their financial incentives to promote savings for retirement. It combines the different results presented in the previous chapters to argue for each policy guideline.

7.1. Financial incentives are useful tools to promote savings for retirement

Financial incentives are useful tools to promote savings for retirement because they are effective at raising retirement savings and help people diversify their sources to finance retirement income.

Financial incentives are effective in raising retirement savings

Tax incentives are effective in raising participation in and contributions to retirement savings plans. Middle and high-income earners react to tax incentives that exempt contributions from taxable income in progressive personal income tax systems, where tax rates increase with taxable income (Chapter 4). This is because individuals respond to the upfront tax relief on contributions that reduces their current tax liability. When contributions are deductible from taxable income, tax relief on contributions increases when taxable income jumps from one tax bracket to the next.

Non-tax financial incentives are better suited to low-income earners. Low-income earners are less sensitive to tax incentives than other income groups. They may lack sufficient resources to afford contributions, but in addition, they may not have enough tax liability to fully enjoy tax relief and they are more likely to have low levels of understanding of tax-related issues. Non-tax financial incentives are therefore better suited to encourage these individuals to save for retirement. Empirical evidence shows that matching contributions and fixed nominal subsidies increase participation in retirement savings plans, especially among low-income earners, although the impact on contribution levels is less clear (Chapter 4).

Participation levels reached with financial incentives alone are typically lower than those obtained through compulsion or automatic enrolment mechanisms. However, some countries may prefer voluntary systems to implementing either of those two policies, while still willing to encourage individuals to save for retirement. Financial incentives keep individual choice and responsibility for retirement planning, as individuals should ultimately be the best placed to evaluate their personal circumstances and determine the most appropriate level of retirement savings that takes into account all of their sources of income.

Financial incentives lead to an increase in national savings, but it is not clear by how much. There is a debate on whether tax incentives for retirement savings plans increase retirement savings as a result of people actually increasing their overall savings (new savings) or as a result of people reallocating savings from traditional savings vehicles. Studies vary in their conclusions, with findings ranging from 9% to 100% of retirement savings representing new savings (Chapter 4). The empirical measurement of whether tax incentives for retirement savings lead to an increase in national savings is inconclusive because of a number of constraints and methodological issues. A reasonable estimate would be that between a quarter and a third of retirement savings in tax-favoured plans represent new savings.

There is, however, more consistent evidence in the literature that low-to-middle income earners are more likely to respond to tax incentives by increasing their overall savings, while high-income earners tend to reallocate their savings. As low-income earners have little wealth, when they decide to contribute to a tax-favoured retirement savings plan their contributions essentially represent new savings. By contrast, high-income earners are more likely to finance contributions to tax-favoured accounts by shifting assets from other taxable accounts or taking on more debt, rather than reducing their consumption.

Therefore, the proportion of new savings in tax-favoured retirement plans will depend on the marginal propensity to save of different income groups, and on whether tax incentives are designed in a manner that will make them more accessible by, or attractive to, individuals at different income levels.

This question of whether financial incentives create new savings is important, as granting financial incentives is costly for the government, in terms of forgone tax revenues or direct spending. The fiscal cost of financial incentives falls with the amount of new savings. However, even if they fail to increase national savings by bringing in new savings, financial incentives may still be a valuable mechanism to encourage people to earmark savings for retirement, in order to make sure that they have enough resources to finance retirement and will not rely on the public safety net once they retire.

Financial incentives help people diversify their sources of retirement income

How best to allocate government resources to enhance retirement income is an important issue to consider. Is it better to provide financial incentives to encourage people to save in supplementary funded pension schemes, or to increase benefits paid by the mandatory pay-as-you-go (PAYG) public pension scheme? The financial resources allocated to financial incentives could be used instead to increase pension benefits in the PAYG public scheme. To address this question, the analysis that follows uses hypothetical scenarios to illustrate some of the implications of removing financial incentives in favour of higher spending in public pension systems.

The baseline scenario represents a situation where financial incentives for retirement savings are in place. It assumes that an average earner subject to a constant 30% marginal tax rate contributes 10% of gross wages yearly to an “EET” supplementary pension plan from age 20 to 64 and withdraws benefits afterwards in the form of a 20-year fixed nominal annuity. The overall cost to the government comes from the tax exemption of returns on investment. Assuming average earnings of EUR 35 000, inflation of 2%, productivity growth of 1.25%, real returns of 3% and a real discount of 3%, the total fiscal cost over the lifetime of the individual amounts to EUR 27 844 in present value terms and the after-tax yearly pension income the individual would receive from age 65 to 84 amounts to EUR 54 854.

Removing tax incentives and using the money to finance additional public pension benefits would reduce the overall level of benefits compared to the baseline. This new scenario assumes that the individual stops contributing to a supplementary pension plan because tax incentives have been removed. It keeps the fiscal cost constant by assuming that the equivalent amount of money (EUR 27 844 over the lifetime of the individual in present value) is used to finance additional public pension benefits for the individual. That money can finance a yearly after-tax additional public pension of EUR 19 706 from age 65 to 84, or only 36% of the pension income generated by a full career of contributions into a tax-incentivised retirement plan (EUR 54 854).

To cover the resulting gap in pension income while keeping the cost to the government constant, the individual would need to save some additional funds in a non-tax-favoured savings vehicle (“TTE”). Contributions to a “TTE” vehicle would not increase the fiscal cost for the government, as this tax regime is the assumed baseline for the taxation of savings. The individual would need to contribute 9% of gross wages pre-tax, or 6.3% after-tax, into a “TTE” vehicle to reach the same level of benefits as were produced by the tax-favoured savings and the lower level of public pension benefits in the baseline. This is less than the 10% contribution rate in the baseline. However, it is not clear whether, without financial incentives, the individual would actually save that amount, in particular given that the “TTE” tax regime discourages savings (in favour of consumption).1

The level of contributions in non-tax-favoured savings vehicles could be further reduced if the government were to create a fund to accumulate and invest the money allocated to the financial incentives over the lifetime of the individual. This would allow the government, as long as the accumulated resources are earmarked for this purpose only, to finance larger additional public pension benefits and reduce the amount of contributions that the individual would have to save in a non-tax-favoured plan to reach the same level of overall pension income as in the baseline scenario. The reduction in the contribution rate would depend on the returns earned by the investment of the government fund, which in turn would depend on whether this fund could invest in a large range of asset classes like any other pension fund or just in long-term government bonds.

This simple example shows that it could be difficult for a government to remove financial incentives and use the equivalent amount of money to increase public pension benefits. If this were done it might leave individuals with a lower retirement income if they do not make extra savings in a non-incentivised plan. In addition, it is contrary to the OECD principle of diversifying the sources to finance retirement income (Chapter 1 of (OECD, 2016[1])).

7.2. Tax rules should be straightforward, stable and common to all retirement savings plans in the country

Complex tax incentives’ structures and frequent changes to the tax rules may reduce the impact of tax incentives on retirement savings.

Tax incentives are difficult to understand. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2012, only 46% of survey respondents knew that money paid into private pensions qualifies for tax relief (Macleod et al., 2012[2]). Moreover, when people are provided choice between plans with different tax treatments, their lack of understanding may lead them to misjudge the alternative plans and fail to pick the most appropriate tax regime. For example, Beshears et al. (2017[3]) show that employees in the United States who are offered choice between a Roth 401(k) plan (upfront taxation, “TEE”) and a traditional 401(k) plan (taxation upon withdrawal, “EET”) do not contribute less to their occupational pension plan than employees who could only contribute to a traditional plan. With upfront taxation, lower after-tax contributions are needed to achieve the same after-tax benefit in retirement as with taxation upon withdrawal (assuming that tax rates remain the same over the lifetime). The authors therefore expected that contributions would go down after the introduction of the Roth option in the occupational pension plan. The authors find that the insensitivity of contributions to the introduction of the Roth option is partially driven by ignorance and/or neglect of the different tax rules.

There is a lot of heterogeneity in the tax treatment of retirement savings plans within countries, adding complexity and confusion. Chapter 2 shows that the tax treatment of contributions to retirement savings plans may change according to the source of the contributions (the employee or the employer), their mandatory or voluntary nature, the type of plan into which they are paid (personal or occupational), or the income of the plan member. In addition, limits to the amount of contributions attracting tax relief may differ for different types of contribution. In countries where returns are taxed, tax rates may vary according to the holding period of the investments, the type of asset class, or the income of the plan member. Moreover, the tax treatment of pension income may differ according to the source of the contributions, the form of the post-retirement product or the age of retirement. All this heterogeneity in the tax treatment of retirement savings complicates the decision that individuals may need to make about how, when, where and how much to save for retirement.

Finally, frequent changes to tax rules may reduce trust in the pension system and prevent individuals from adequately planning ahead.

Tax rules for retirement savings should therefore be straightforward, stable and common to all retirement savings plans in the country to avoid creating confusion among people who may find difficult to understand the differences and choose the best option for them.

7.3. The design of tax and non-tax incentives for retirement savings should at least make all income groups neutral between consuming and saving

Chapter 3 introduced the overall tax advantage which is used throughout the monograph to assess whether the tax treatment of retirement savings and the non-tax incentives paid by governments provide a financial or tax advantage when people save for retirement. The overall tax advantage is defined as the difference in the present value of total tax paid on contributions, returns on investment and withdrawals when an individual saves in a benchmark savings vehicle or in an incentivised retirement plan, given a constant contribution rate during the entire career. It is expressed as a percentage of the present value of pre-tax contributions. The overall tax advantage therefore represents the amount saved in taxes by the individual over working and retirement years when contributing the same amount (before tax) to an incentivised pension plan rather than to a benchmark savings vehicle.

The overall tax advantage should not be confused with the incentive to save. A positive overall tax advantage means that the individual would save in taxes paid when contributing to an incentivised retirement plan rather than to a benchmark savings vehicle. It does not mean that the individual has an incentive to save. The overall tax advantage and the incentive to save are two different measures.

The incentive to save is measured by the after-tax rate of return. A tax system is neutral when the way present and future consumption is taxed makes the individual indifferent between consuming and saving. This is achieved when the after-tax rate of return is equal to the before-tax rate of return.

Taxing returns creates a disincentive to save because the present value of the income is greater if it is used for consumption today than if it is used for consumption tomorrow (Mirrlees et al., 2011[4]). The tax regime that applies to most traditional forms of savings (“TTE”) therefore reduces the incentive to save.

Therefore, the tax treatment of retirement savings may lead to a positive overall tax advantage independently of whether the individual has an incentive to save, is indifferent between saving and consuming, or has an disincentive to save (i.e. the after-tax rate of return may be larger, equal or lower than the before-tax rate of return).

As PAYG public pension systems are under increasing strain due to population ageing and financial sustainability concerns, the tax treatment of retirement savings should at least not discourage savings. It may even be justifiable to incentivise retirement savings more for certain groups of individuals, in breach of tax neutrality. Interactions with the public pension system and the general tax system should also be carefully analysed. People will refrain from saving for retirement if doing so reduces their entitlements to public pensions or other forms of tax relief.

A number of different designs can reach tax neutrality between saving and consuming under certain assumptions. Taxing retirement savings upon withdrawal (“EET”) achieves tax neutrality provided that the individual faces a constant personal income tax rate over time. Upfront taxation of retirement savings (“TEE”) also achieves tax neutrality as long as returns are not above the “normal return to saving”. The normal return to saving is the return that just compensates for delaying consumption. It is also often called the risk-free return (Mirrlees et al., 2011[4]).

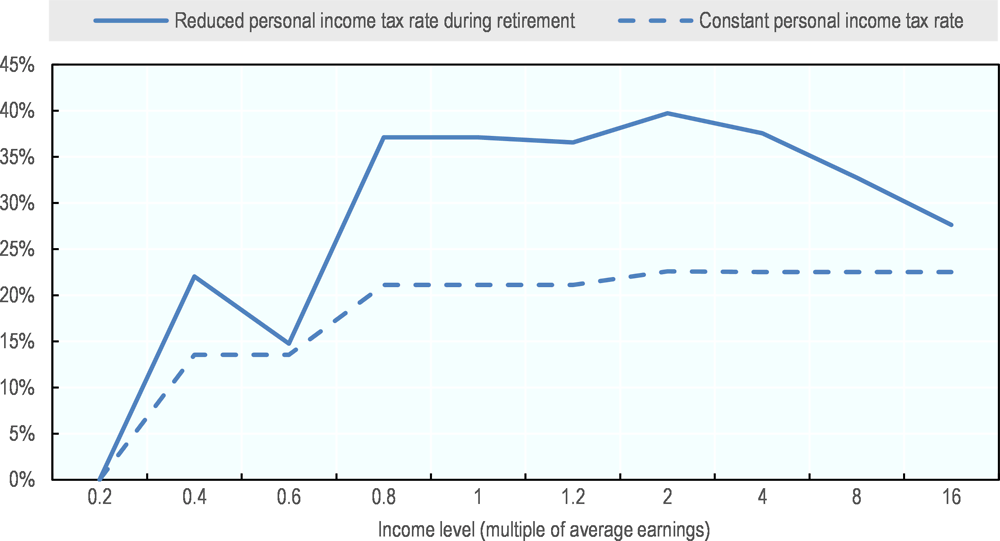

Taxing retirement savings upon withdrawal is likely to breach tax neutrality and to provide incentives to save, in particular for middle to upper-middle income groups. Retirement income is usually lower than income from work, hence retirement income is likely to be taxed at a lower average rate than income from work. In that case, the tax paid on withdrawals may not compensate fully for the initial tax relief on contributions and the overall tax advantage is larger. This also means that the tax regime favours saving over consuming. This is illustrated in Figure 7.1. The dashed line represents the situation when individuals face a constant personal income tax rate over time, implying that the “EET” tax regime achieves tax neutrality for all income groups. The solid line shows that, when individuals face a lower tax rate in retirement than while working, the “EET” tax regime provides an incentive to save as the overall tax advantage exceeds the one achieved with tax neutrality, in particular for middle to upper-middle income earners. For high-income earners, there is a convergence towards tax neutrality because the higher is the income, the less likely is the individual to experience a fall in tax rate at retirement.

It should be noted that tax neutrality does not imply that the tax expenditure related to tax incentives for retirement savings will be equally distributed among different income groups. Tax neutrality only implies that the after-tax rate of return is equal to the before-tax rate of return for all income groups, creating no distortion between present and future consumption.

Tax expenditures related to the tax treatment of retirement savings will tend to be concentrated on high-income individuals for three main reasons. First, in voluntary pension systems, high-income earners are more likely to participate in private pension plans than other income groups, reflecting their higher propensity and capacity to save. Second, their higher income results in a greater value of the tax relief per household even when the tax rate is the same for everyone. Third, in tax systems where tax rates increase with taxable income, high-income earners face the highest marginal tax rates, thereby benefiting more on every unit of the flows that attract tax relief.

7.4. Countries with an “EET” tax regime already in place should maintain the structure of deferred taxation

The most common tax treatment of retirement savings exempts contributions and returns on investment from taxation, and taxes pension benefits and withdrawals as income. Half of the OECD countries currently apply a variant of the “EET” tax regime. The other half is split across five other tax regimes.

This tax regime always generates a long-term fiscal cost to the government. In mature pension systems, taxes collected on withdrawals are large and therefore fiscal costs are lower. The introduction of pension arrangements with an “EET” tax treatment leads to a sharp increase in the net tax expenditure that arises from comparing against a “TTE” benchmark tax treatment, as no one initially receives pension benefits (i.e. no tax revenues on withdrawals) while participants make tax-deductible contributions and start accumulating assets tax free. Over time, however, former contributors become retirees and receive pension benefits on which they pay taxes, thereby reducing the net tax expenditure. Once the system has reached maturity, i.e. all retirees draw their pension based on a full career and constant contribution rules, the net tax expenditure stabilises at its steady-state level. That level is positive as taxes collected on withdrawals are lower than tax revenues forgone on contributions and on accrued income, implying a long-term fiscal cost for the government. However, the size of withdrawals in a given year exceeds the size of contributions, as withdrawals are the result of several years of contributions accumulating with compound interests. Taxes collected on withdrawals each year therefore more than compensate for tax revenues forgone on contributions (Chapter 5).

Countries already using the “EET” tax regime should therefore maintain the structure of deferred taxation. The upfront cost incurred at the introduction of the funded pension system is already behind and the rewards in the form of increased tax collection on pension income are in the horizon. As societies continue to age, these larger tax revenues may additionally help cope with increased pressure on public services.

Policy proposals to modify the “EET” tax regime on retirement savings should consider the short-term and long-term impacts on the fiscal cost. Chapter 6 shows that different tax treatments that provide the same overall tax advantage to the individual can have different implications on the fiscal cost. For example, switching from taxation upon withdrawal (“EET”) to upfront taxation (“TEE”) would reduce the fiscal cost in the short term but actually increase it in the long term. At the time of the switch, the fiscal cost drops significantly as contributions stop being tax deductible and the current generation of retirees pay taxes on their pension benefits because they have contributed under the “EET” tax regime. Over time, however, tax revenues collected on withdrawals decline as new generations of retirees have contributed under the “TEE” tax regime. This increases the fiscal cost up to a level that is higher than just before the switch, because taxes collected on withdrawals under a mature “EET” tax regime are higher than taxes collected on contributions under a mature “TEE” tax regime.

7.5. Countries should consider the fiscal space and demographic trends before introducing a new retirement savings system with financial incentives

The total fiscal cost of financial incentives varies greatly across countries, but remains in the low single digits of GDP. Chapter 5 estimates the current and future profile of the net tax expenditure related to private pensions in Australia, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Iceland, Latvia, Mexico, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic and the United States.2 The net tax expenditure in a given year is measured as the net amount of personal income tax revenues forgone on contributions, revenues forgone on accrued income and revenues collected on withdrawals that arise when comparing with the tax treatment of traditional savings accounts (“TTE”). It adds to direct spending associated with non-tax incentives, when relevant, in order to estimate a total fiscal cost. The fiscal cost varies from 2%-3% of GDP in Australia and Iceland to 0.1%-0.3% of GDP in Chile, Mexico, New Zealand and the Slovak Republic, and it even turns negative in Denmark, indicating an overall positive fiscal effect in the future.

In addition, the fiscal cost evolves over time and depends on the level of maturity of the pension systems and the age profile of the total population of the country.

A mature pension system is one in which current retirees draw their pension based on a full career and constant contribution rules. Individuals who were already in the labour market when a new pension system was introduced will draw their pension on a part of their career only. Similarly, if the contribution rate to the system changes, it will take some time to see retirees drawing their pension based on the new contribution rate during their entire career.

The maturing phase may cause the fiscal cost to deviate from its long-term steady-state level. During the maturing phase, aggregate asset and benefit levels increase over time until they reach a stable level (steady state). However, there is a lag in the growth of benefits behind that of assets and investment income. Depending on which flows are taxed, this lag may create temporary increases or decreases in the net tax expenditure before it reaches its steady-state level. For example, all tax regimes that tax pension benefits (e.g. “EET”, “ETT”, “TET”) will create a hump shaped net tax expenditure during the maturing phase of the pension system because, as the density of contributions progresses, asset and investment income levels grow and so do, with a lag, benefit levels and their associated tax collection.

Demographics also affect the fiscal cost related to financial incentives because cohorts of different sizes modify the flows and stocks in the pension system. When there is a population bulge, the new larger cohorts entering the labour market raise the aggregate levels of earnings, GDP and contributions. Asset levels increase only with a lag. When those larger cohorts retire, it is the aggregate level of benefits that increases. The different flows and stocks in the pension system go back to their initial level when all the individuals in the larger cohorts have passed away. The changes in the levels of contributions, assets, investment income and benefits will affect the net tax expenditure, and depending on which flows are taxed, the net tax expenditure may be temporarily above or below its steady-state level.

Countries introducing a new retirement savings system with financial incentives should therefore consider the fiscal space and demographic trends. The fiscal space will determine how generous the financial incentives can be, as different approaches to designing financial incentives will produce a different fiscal cost (Chapter 6). In addition, as the pension system matures, the fiscal cost will develop differently depending on the tax regime chosen before reaching its steady state. For example, countries should be aware that introducing a pension system where only withdrawals are taxed will create a larger upfront fiscal cost. This needs to be fully disclosed and accounted for when introducing reforms to avoid creating a political backlash, especially in times of economic crises. Finally, demographic trends matter as they may temporarily inflate or deflate the fiscal cost.

7.6. Identifying the retirement savings needs and capabilities of different population groups could help countries to improve the design of financial incentives

The role of supplementary pension schemes has evolved over time. Historically, public PAYG pension schemes played a predominant role in retirement income provision in most jurisdictions. Supplementary funded pension schemes were mostly for high-income earners who wanted to top up their public pension to maintain their standard of living in retirement. The relative importance of PAYG and supplementary funded pension schemes has been changing over time. Concerns over both the financial sustainability and the retirement adequacy of pension systems lead many countries to reduce the generosity of public pension schemes (e.g. increase in the retirement age, less generous indexation mechanisms) and to strengthen the role of supplementary funded pension schemes (OECD, 2015[5]). As a result, the design of financial incentives to promote supplementary funded pension schemes should evolve and adapt to the needs of a broader and more diverse population.

Specific financial incentives to encourage poor individuals to contribute voluntarily to a supplementary funded pension scheme are not likely to be necessary. Workers whose income is below or around the poverty line cannot afford to save in supplementary funded pension schemes. At retirement, they will rely on the public pension scheme only and the safety net should prevent them from falling into poverty.

The situation may be different for mandatory pension systems when the labour market is highly informal. Chile and Mexico for example provide government subsidies for people contributing to their individual pension accounts. Although both systems are mandatory for employees, large labour informality prevents universal coverage. As informality is more widespread among low-income workers, financial incentives target those workers in order to increase their contribution densities.

Financial incentives should adapt to the savings needs of different groups of individuals. In many countries, public pensions are calculated according to a defined benefit formula that delivers different replacement rates to different income groups. Individuals whose replacement rate does not permit them to maintain their standard of living in retirement should save more in supplementary pension schemes. Financial incentives may need to be higher for those with higher savings needs.

Granting financial incentives to high-income earners may be controversial. High-income earners usually get the lowest replacement rates from public PAYG pension schemes. They need to save to complement their public pension and maintain their standard of living. Should they get financial incentives to do so? One the one hand, high-income earners probably do not need to get financial incentives to save. They have a higher propensity to save than other income groups and will save whatever the tax treatment applied to the savings vehicle. Moreover, they tend to shift their savings from non-tax-favoured to tax-favoured vehicles rather than creating new savings, as shown in Chapter 4. On the other hand, policy makers may want to make sure that more savings are earmarked for retirement and allocated to long-term investments. In addition, countries may want to treat all retirement savings, whether through PAYG or funded pension arrangements, equally with respect to the tax code.3 Following these arguments, tax regimes that reach tax neutrality could be used to equalise the incentive to save across all income groups. These do not grant excessive tax advantages to high-income earners (Figure 7.1), provided that the interaction with the personal income tax system is taken into consideration when designing the incentive (e.g. the “EET” system grants a higher incentive to save to middle and upper-middle income earners when their marginal income tax rate falls at retirement). In addition, limits to the amount of contributions attracting tax relief should be established to restrict the possibility of using retirement savings plans as tax optimisation tools.

7.7. Tax credits, fixed-rate tax deductions or matching contributions may be used when the aim is to provide an equivalent tax advantage across income groups

In some countries, policy makers may consider that most individuals should get an equivalent overall tax advantage because savings needs are similar across the population. For example, when the mandatory pension system is defined contribution in nature (either financial and notional), replacement rates are equal across a large range of income levels, so that most individuals have the same needs to save in supplementary funded pension schemes to complement their mandatory pension.

Tax deductions at fixed rate and tax credits are alternatives to tax deductions at the marginal rate that achieve a smoother distribution with income. As shown in Figure 7.1, the “EET” tax regime provides a larger overall tax advantage to middle and upper-middle income earners. It is possible to adjust the “EET” tax regime by changing the tax treatment of contributions to reach a smoother distribution of the overall tax advantage by income. Tax deductions at fixed rate and tax credits can be used to achieve this. They provide the same tax relief on after-tax contributions to all individuals, independent of their income level and marginal income tax rate. Both approaches are strictly equivalent when the tax credit is refundable. When the tax credit is non-refundable, individuals who pay no or little income tax do not get the tax credit or not in full, respectively.

Compared to tax deductions at the marginal rate, tax deductions at fixed rate and tax credits typically reduce the overall tax advantage for high-income earners and increase it for low-income earners (Chapter 6). The number of winners and losers depends on how high the level of the credit rate or deduction rate is set. The lower the credit rate, the higher the number of individuals worse-off from a reduction in the overall tax advantage and the lower the number of individuals benefitting from an increase in the overall tax advantage. The reduction in the overall tax advantage can still be achieved without removing the incentive to save to any individual. As seen previously, with the “EET” tax regime, middle to upper-middle income earners get an overall tax advantage that is above tax neutrality. There may be room therefore to reduce their overall tax advantage without completely removing their incentive to save.

The structure of tax declaration and tax collection may influence individuals’ perception of tax credits and tax deductions and lead to different levels of savings. For example, when pension contributions are deducted from pay before calculating and paying personal income tax, the tax relief is provided automatically and saved in the pension account. This may not be the case when tax deductions and tax credits need to be claimed through the income tax declaration. When contributions are first taxed at the individual’s marginal rate, the tax refund (fixed rate of deduction or tax credit) may be provided later in the year or even the following year to the individual. If individuals anticipate that they will eventually get a tax refund, they can increase their after-tax contribution to save the whole tax relief in the pension account. However, if they do not anticipate it, the after-tax contribution may not be as high as with an automatic direct tax deduction.

Another approach to smoothing out the overall tax advantage across income groups is to combine the “EET” tax regime with matching contributions. Policy makers should keep in mind the starting point when designing financial incentives. Most OECD countries already have tax incentives in place, in particular the “EET” tax regime. Introducing matching contributions when retirement savings already enjoy an “EET” tax regime would be a practical solution to smooth out the overall tax advantage across income groups. Indeed, it would increase the tax advantage on contributions for all earners in the same proportion (equivalent to the match rate). At the same time, it would increase assets accumulated, pension benefits and the amount of tax due on the latter. That increase in tax due on withdrawals would hit higher-income earners harder, as they are the ones subject to the highest marginal tax rates. All in all, the introduction of a matching contribution would increase the overall tax advantage for all individuals, but less so for high-income earners. It therefore helps to achieve a smoother tax advantage across income groups (Chapter 6). It would however incur an additional fiscal cost. In the long run, this additional cost would be smaller than the direct spending on the matching contribution, as it is partially compensated by an increase in taxes collected on the higher withdrawals.

7.8. Non-tax incentives, in particular fixed nominal subsidies, may be used when low-income earners save too little compared to their savings needs

In some countries, low-income earners above the poverty line may not qualify for the safety net when they retire and find themselves with replacement rates too low to maintain their standard of living. In that case, policy makers may want to target those individuals to receive a greater incentive to contribute to supplementary funded pension schemes in order to encourage them to complement their public pension.

Non-tax financial incentives are better tools to encourage retirement savings among low-income earners for several reasons.

First, low-income earners are not very sensitive to tax incentives. Besides the fact that low-income earners may lack sufficient resources to afford contributions, they may not have enough tax liability to fully enjoy tax relief and they are more likely to lack adequate understanding of tax-related issues. As shown in Chapter 4, among low-income earners, the combination of a progressive tax system and tax-deductible contributions may not encourage retirement savings. Carbonnier, Direr and Slimani Houti (2014[6]) find that low-income earners aged 45 to 55 do not increase their contribution level when their marginal tax rate increases. This suggests that the structure of the income tax system is not the main factor for low-income earners in deciding about their contribution level.

Second, non-tax incentives are not linked to the individual’s tax status, making them attractive for all individuals. Matching contributions and fixed nominal subsidies are payments made directly by the government into the pension account of eligible individuals. As non-tax incentives are not linked to the individual’s tax status, the value of the incentive is not limited by the tax liability.4 Therefore all individuals can fully benefit from them as long as they fulfil the entitlement requirements (e.g. having an income below a certain level, contributing a certain proportion of income). Non-tax incentives can also be used to target disadvantaged groups, such as young workers or women.

Third, non-tax incentives are automatically saved into the pension account, while this may not be the case with tax incentives. Non-tax incentives are indeed directly invested in the pension plan, therefore increasing the assets accumulated at retirement and thus future pension benefits. By contrast, individuals eligible for a tax credit or a tax deduction (when for example it needs to be claimed) may not save the value of the tax incentive in the pension account if they do not increase their after-tax contributions in anticipation of the receipt of the tax refund.

Fourth, the design of matching contributions and fixed nominal subsidies makes them ideal tools to target low-income earners. Fixed nominal subsidies naturally provide a higher overall tax advantage to low-income earners as the value of the subsidy represents a higher share of their income. This applies independently of the structure of the personal income tax system (higher tax rates for higher taxable income or fixed tax rate). In all countries using this approach, the subsidy is used as a complement to tax incentives, so that all income groups get an overall tax advantage when contributing to a supplementary funded pension scheme, with an extra encouragement for low-income earners. Targeted matching contributions and capped matching contributions can achieve similar results. In addition, matching contributions alone (i.e. associated with the “TTE” tax regime) also provide larger incentives to low-income earners. This approach provides an overall tax advantage that declines with income because the match rate applies on after-tax contributions and the additional investment income generated by the matching contributions is taxed. The reduction in the overall tax advantage may, however, remove the incentive to save for high-income earners.

7.9. Countries using tax credits may consider making them refundable and converting them into non-tax incentives

Refundable tax credits are more attractive for low-income earners. Tax credits should be refundable when the policy objective when introducing a tax credit is to provide the same tax relief to all individuals on their contributions. With non-refundable tax credits, individuals with low or no income tax liability only get, respectively, part of the tax credit or nothing. By contrast, individuals with a low tax liability can still benefit from refundable tax credits as the difference between the value of the credit and the tax liability is paid to the individual.

In addition, the value of the tax credit could be paid directly into the pension account (converting the tax credit into a non-tax incentive) to help individuals to build larger pots to finance retirement. As seen previously, individuals may not save the value of the tax credit in their pension account as the tax credit is usually received well after contributions were made and taxed.

Moreover, people may be more responsive when the incentive is framed as a matching contribution rather than as a tax credit. Saez (2009[7]) shows that individuals receiving a 50% matching contribution participate more in retirement savings plans and contribute more than individuals receiving an equivalent incentive framed as a 33% tax credit.5 The results imply that taxpayers do not perceive the match and the tax credit to be economically identical. Some individuals may have perceived the 33% credit rate as equivalent to a 33% match rate, thereby reducing the incentive. Another explanation could be linked to behavioural factors. Individuals had to wait for two weeks to receive the credit rebate, and due to loss aversion, contributing, for example, USD 450 and then receiving USD 150 back may feel more painful than contributing just USD 300 and obtaining a match of USD 150 to reach the same USD 450 total contribution.

7.10. Countries where pension benefits and withdrawals are tax exempt may consider restricting the choice of the post-retirement product when granting financial incentives

Early withdrawals and lump sum payments may be inconsistent with granting financial incentives to promote savings for retirement. When financial incentives aim at encouraging people to complement their public pension by saving in a supplementary funded pension scheme, certain withdrawal options may be inappropriate. For example, early withdrawals will eventually reduce the level of the supplementary funded pension, possibly reducing overall retirement income. Moreover, lump sum payments may be used for other purposes than financing a supplementary funded pension. Lump sums may however improve the financial situation of retirees when they are used to pay off a debt for example, but at the cost of reducing overall retirement income and potentially affecting its adequacy.

Taxing pension benefits discourages early withdrawals and lump sum payments when the amounts received are added to the individuals’ earnings and taxed at their marginal rate. Early withdrawals when the individual is still working and earning work income may therefore push taxable income into a higher tax bracket. In the same way, lump sum payments may represent large amounts that fall into a higher tax bracket than regular pension payments (annuities or programmed withdrawals). Some countries like Ireland and the United Kingdom tax lump sums only partially in order to reach a more neutral tax treatment across the different post-retirement products. However, the majority of countries taxing retirement benefits apply the same tax treatment across the different types of post-retirement product, i.e. life annuity, programmed withdrawal or lump sum, thereby discouraging lump sum payments (Chapter 2).

By contrast, when withdrawals are tax exempt, individuals are not penalised for withdrawing early or choosing a lump sum. This may defeat the purpose of encouraging people to save in supplementary funded pension schemes in order to complement their public pension.

In this context, several measures could be used to restrict the choice of the post-retirement product. For example, Chapter 2 shows that some countries provide tax relief on contributions conditional on people complying with certain rules, such as contributing for a minimum period (e.g. Belgium, Estonia and Luxembourg), not retiring before a certain age (e.g. Belgium, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg and Sweden) or taking benefits in a certain form (e.g. Finland, Germany, Portugal and Sweden). Other countries take back some of the subsidies in the case of early withdrawals (e.g. Turkey) or lump sum payments (e.g. Austria, Chile). An alternative option is to incentivise people to annuitize their pension income through a more favourable tax treatment for annuities as compared to programmed withdrawals and lump sums (e.g. the Czech Republic, Estonia and Korea) or through a government subsidy (e.g. Turkey).

7.11. Countries need to regularly update tax-deductibility ceilings and the value of non-tax incentives to maintain the attractiveness of saving for retirement

Ceilings on tax-deductible contributions are common in OECD countries and cap the amount contributed by high-income earners. Limits to the amount of contributions attracting tax relief can be defined as a proportion of the contributor’s income up to a nominal ceiling, or as a fixed nominal amount, usually a multiple of a reference value in the country (Chapter 2). When excess contributions are allowed, they are usually taxed at the individual’s marginal tax rate. In some countries, tax penalties also apply for excess contributions unless the individual withdraws the amount in excess of the ceiling. This creates a strong disincentive for high-income earners to contribute above the ceiling and de facto caps their contributions.

Tax-deductibility ceilings for contributions tend to be updated yearly only in line with price inflation, if at all. When wages grow faster than inflation, not indexing tax-deductibility ceilings, or indexing only in line with inflation, increases the proportion of individuals reaching the ceiling over time and reduces their contributions to retirement plans. This may be inconsistent with the policy objective of helping people to improve their chances of obtaining a higher retirement income by saving in supplementary funded pension schemes.

Similarly, keeping the value of non-tax incentives constant over time may reduce the attractiveness of saving for retirement and lower the positive impact on participation. Most countries providing matching contributions and fixed nominal subsidies do not update the maximum contribution and subsidy value on a yearly basis. In economies with growing wages, this implies that the value of the incentive represents a lower share of people’s income over time. Regular updates are therefore needed to keep the incentive at least constant.

References

[3] Beshears, J. et al. (2017), “Does Front-Loading Taxation Increase Savings? Evidence From Roth 401(K) Introductions”, Journal of Public Economics 151, pp. 84-95, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20738.

[6] Carbonnier, C., A. Direr and I. Slimani Houti (2014), “Do savers respond to tax incentives? The case of retirement savings”, Annals of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 113-114, pp. 225-256.

[2] Macleod, P. et al. (2012), Attitudes to Pensions: The 2012 survey, Department for Work and Pensions.

[4] Mirrlees, J. et al. (2011), Tax by design, Oxford University Press.

[1] OECD (2016), OECD Pensions Outlook 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/pens_outlook-2016-en.

[5] OECD (2015), Pensions at a Glance 2015: OECD and G20 indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2015-en.

[7] Saez, E. (2009), “Details Matter: The Impact of Presentation and Information on the Take-up of Financial Incentives for Retirement Saving”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 1/1, pp. 204-228, https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.1.1.204.

[8] Sandler, R. (2002), Medium and long-term retail savings in the UK: A review.

Notes

← 1. The incentive to save is measured by the after-tax rate of return. A tax system is neutral when it does not distort an individual’s choice between present and future consumption. This is achieved when the after-tax rate of return is equal to the before-tax rate of return. With the “TTE” tax regime, the after-tax rate of return is lower than the before-tax rate of return. This reduces the incentive to save as the present value of the income is greater if it is used for consumption today than if it is used for consumption tomorrow.

← 2. Only a limited number of countries is included in the analysis, as the calculations require a large amount of data.

← 3. Another argument for granting financial incentives to high-income earners could be the desire to maintain the social contract that supports the poverty alleviation functions of public pension schemes.

← 4. Refundable tax credits can replicate the economic effects of non-tax incentives, as long as they are refunded directly into a pension account.

← 5. A credit rate of t is economically equivalent to a match rate on the contribution of t/(1-t). For example, a 25% refundable tax credit is economically equivalent to a matching contribution of one-third. This is because the tax credit rate is expressed as an inclusive rate (i.e. including the value of the credit), while the match rate is expressed as an exclusive rate (i.e. excluding the value of the matching contribution).