Chapter 7. Enhancing integrity in public procurement in Mexico City

In line with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, this chapter assesses whether Mexico City has developed and implemented effective general standards for public procurement procedures, as well as specific procurement safeguards to preserve integrity in the public procurement system. The chapter reviews the transparency and the digitalisation of the system, but also the access to procurement information. It also describes how to preserve integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers and civil society. This chapter also analyses the conflict of interest framework for public procurement officials and the private sector. Lastly, it describes the oversight and control mechanisms in place as well as the remedies and sanctions system.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

7.1. Introduction

Public procurement refers to the process of identifying what is needed; determining who the best person or organisation is to supply this need; and ensuring that what is needed is delivered to the right place, at the right time, for the best price, and that all this is done in a fair and open manner. It accounts for a substantial portion of the taxpayers’ money in OECD member and partner countries, representing, on average, 12% of GDP and 29% of national budget. Public procurement is a crucial pillar of strategic governance and services delivery for government and a key economic activity of governments. With such high financial interests at stake, the numerous volume of transactions, and the close interaction between the public and the private sectors, many opportunities are present for private gain and waste at the expense of taxpayers.

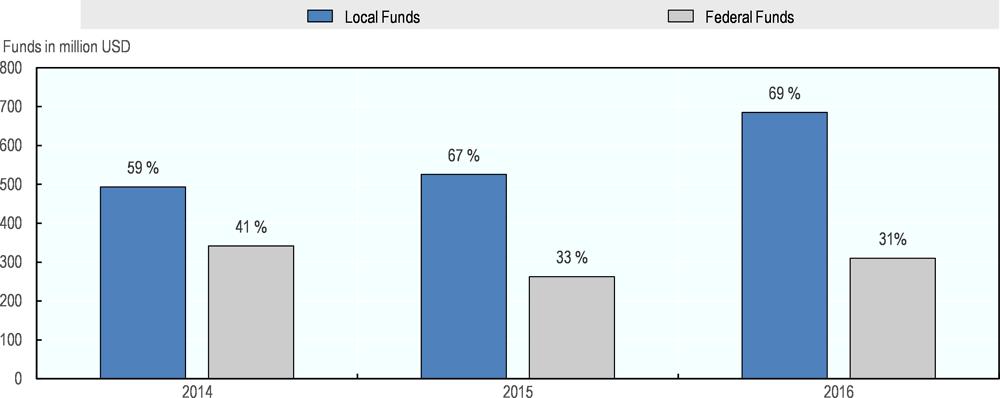

Governments are expected to prevent and mitigate these risks and carry out public procurement activities efficiently and with high standards of conduct. The goal is to ensure high quality of service delivery and safeguard the public interest, in all phases of the procurement cycle and at all levels of government where integrity breaches can occur. With its federal government structure, Mexico is one of the OECD countries where procurement at the sub-central level is greater than the national level (see Figure 7.1). The share of public procurement at the sub-central level is around 70% and Mexico City’s public procurement accounts for a large proportion of the country’s spending: USD 985 million.

Enhancing integrity and public procurement systems has been identified as a clear priority in the country which is undertaking reforms at the federal and also at the state level. This priority was highlighted in the eight measures on integrity announced by the president and also in the programme of Mexico City’s government. Of these eight measures, four, described in Box 7.1, directly target the procurement process.

-

A Protocol of Conduct for Public Servants in Public Procurement, and on the granting and extension of licences, permits, authorisations and concessions (Acuerdo por el que se expide el protocolo de actuación en materia de contrataciones públicas, otorgamiento y prorrogo de licencias, permisos, autorizaciones y concesiones), which is included in the General Law on Administrative Responsibilities (Ley General de Responsabilidades Administrativas);

-

A Registry of Public Servants of the Federal Public Administration involved in public procurement processes (Registro de servidores públicos de la Administración Pública Federal que intervienen en procedimientos de contrataciones públicas), including their classification according to their levels of responsibility and their certification;

-

An online publication of sanctioned suppliers, specifying the reason for the sanction;

-

Increased collaboration with the private sector to reinforce transparency in procurement procedures and decision making to reinforce integrity by involving citizens in identifying vulnerable processes and procedures, and the development of co-operation agreements with chambers of commerce and civil society organisations.

Source: Adapted from http://www.gob.mx/presidencia/prensa/anuncia-el-presidente-enrique-pena-nieto-un-conjunto-de-acciones-ejecutivas-para-prevenir-la-corrupcion-y-los-conflictos-de-interes.

Mexico City has two different public procurement systems, depending on the source of funding. When using federal funds, contracting authorities (CAs) have to follow the federal system. However, when using local funds, CAs have to follow exclusively the system developed at the local level by Mexico City. As described in Figure 7.2, in 2016, 69% of CDMX public procurement derived from local funds. The public procurement regulatory framework when using local funds is based primarily on the local public procurement law (Ley de Adquisiciones para el distrito federal, or PPL), which was revised in September 2016, as well as the Public Works law (Ley de Obras Públicas del Distrito Federal, or PWL), which was revised in September 2015. For the implementation of each of these two laws, Mexico City issued regulations (Reglamento de La Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público, or REGPPL, and Reglamento de la Ley de Obras Públicas del distrito federal, or REGPWL).

In addition to the laws and regulations mentioned above, Mexico City issued two circulars regulating procurement activities and resource management: Circular 1 for ministries, administrative Units, decentralised bodies and public administration entities of the public administration of the Federal District; Circular 1 bis for territorial demarcations (delegaciones).

When contracting authorities of Mexico City (ministries, administrative units, decentralised bodies, public administration entities and territorial demarcations) use federal funds, they are subject to the federal regulatory framework: the Law on Acquisitions, Leasing and Services of the Public Sector (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público, or LAASSP) and the Law on Public Works and Related Services (Ley de Obras Públicas y Servicios relacionados con las mismas, LOPSRM). While mentioning the two systems, this chapter will focus on the system developed by Mexico City, analysing the legal and institutional framework but also the processes to ensure and enhance integrity in the public procurement system.

This chapter is organised into four sections: 1) enhancing transparency and access to information on public procurement processes and activities; 2) preserving integrity and promoting a culture of integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers and civil society; 3) encouraging public integrity through an effective management of conflict of interest in the procurement process; 4) strengthening the accountability, control and risk management system of public procurement processes.

7.2. Enhancing transparency and access to information on public procurement processes and activities

7.2.1. Enhancing the access to procurement opportunities and the efficiency of the system by reducing the use of exceptions to open and competitive tendering.

Integrity risks are also linked to the procurement method used by contracting authorities (CAs). The use of open and competitive tendering should be the standard method for conducting procurement as a means of driving efficiencies, fighting corruption, obtaining fair and reasonable pricing and ensuring a competitive outcome. If exceptional circumstances justify limitations to competitive tendering and the use of single-source procurement, they should be limited, pre-defined and when they are used, should require appropriate justification and adequate oversight, taking into account the increased risk of corruption, including by foreign suppliers (OECD, 2015[2]). Indeed, according to the Foreign Bribery Report, more than half of the foreign bribery cases occurred in obtaining a public procurement contract. Therefore, the inappropriate choice of the procurement procedure entails a high risk of corruption, particularly with a lack of proper justification for the use of non-competitive procedures and the abuse of non-competitive procedures on the basis of legal exceptions: contract splitting, abuse of extreme urgency and unsupported modifications (OECD, 2016[3]).

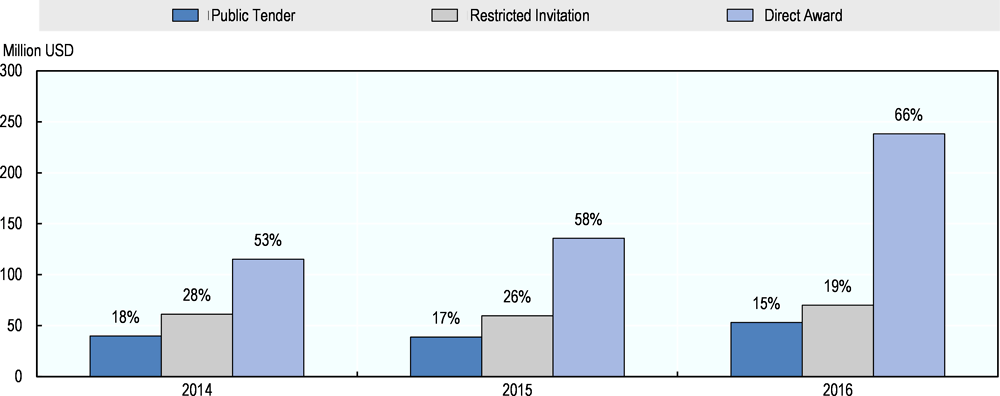

In Mexico City, the procurement regulatory framework provides the possibility to use three procurement methods: open tender (licitación pública), which is the general rule, restricted tender (invitación a cuando menos tres proveedores) and direct award (adjudicación directa). The exceptions to open tender are defined in Articles 54, 55 and 57 of the PPL and Article 63 of the PWL, which allow for various circumstances. Box 7.2 describes legal exceptions to open and competitive tender.

1. Artwork or goods and services with no appropriate /technical substitutes;

2. anything that poses a danger or entails alteration to the social order, economy, public services, health, safety or the environment of any zone or region of the Federal District;

2 bis. when it is demonstrated that there are better conditions in terms of price, quality, financing or opportunity;

3. the respective contract has been terminated for causes that can be attributed to the supplier;

4. after an open tender or restricted tender procedure that has been declared deserted;

4 bis. for public interest or confidentiality reasons;

5. justified reasons for the procurement of a particular brand;

6. procurement of perishable goods, prepared foods, grains and basic or semi-processed food products for immediate use or consumption;

7. consultancy services, studies and research, audits and services of a similar nature, whose procurement under the open tendering may affect the public interest or disclose confidential information about the public service;

8. procurement with specific marginalised rural or urban groups ( social procurement);

9. in the case of acquisitions of assets, leasings or contract of services made by ministries, deconcentrated bodies, territorial demarcations and government entities for productive processes to comply with their mandates or for commercial purposes;

10. the procurement of insurance, maintenance, preservation, restoration and repair services of goods in which it is not possible to define its scope, establish the catalogue of concepts and quantities of work or determine the corresponding specifications;

11. procurement with natural or legal persons who are not usual suppliers and who, because they are in a state of liquidation or dissolution or under judicial intervention, can offer goods and services under exceptionally favourable conditions;

12. professional services provided by legal persons;

13. procurement with natural or legal persons offering goods and services of a cultural, artistic or scientific nature, in which it is not possible to define the quality, achieve or compare results;

14. military goods and services;

15. medications, healing material, and special equipment for hospitals, clinics or necessary for health services;

16. goods and services with an official price;

17. goods and services involving technological innovation generating a transfer of technology to the city and/or investment and/or employment;

18. goods and services for activities directly linked to the development of scientific and technological research.

19. when the contract has not been formalised, due to causes attributable to the supplier.

Source: Mexico City Public Procurement Law (2016), http://www3.contraloriadf.gob.mx/prontuario/index.php/normativas/Template/ver_mas/65234/31/1/1

The heads of CAs authorise exceptions to open tender, based on justifications provided by the concerned departments. In 2016, more than 66% of Mexico City’s public procurement was performed through direct award and more than 19% through restricted tenders. In other OECD countries, open tenders are used much more frequently. In 2013, for instance, they represented 82% of total procedures in Spain, 72% in Germany and 88% in Sweden. In Mexico City, the use of exceptions has risen in the past three years: 82% in 2014, 83% in 2015 and 85% in 2016 (see Figure 7.3). Mexico City should consider reducing the cases of legal exceptions to open tender in the related articles of the PPL and PWL, to decrease the associated integrity risks.

7.2.2. Improving the monitoring of exceptions to competitive tenders.

In addition to the control system in place, Mexico City developed a specific control mechanism to ensure the integrity and the efficiency of the system: Procurement committees. This committee is a group of designated officials set up to independently review and assess procurement activities whose main goal is to ensure the efficiency and the integrity of the system. In a procurement process, this is considered the first line of defence in the three lines of defence model.

Procurement committees exist at the central level and at the delegation level and also at the level of the government entity (for this last, see Box 7.3). A key role of procurement committees is to issue an opinion on exceptions to competitive and open procedures. CAs are required to send a report on direct awards on a monthly basis to the Office of the Comptroller-General.

1. Draft and approve its manual of integration and operation;

2. Prepare and approve the annual working programme and evaluate it on a quarterly basis;

3. Monitor compliance with their agreements;

4. Apply the general guidelines and policies issued by the Central Committee;

5. Establish policies for price verification, quality tests, environmental aspects and other requirements formulated by its operational areas, in accordance with the policies established by the Central Committee;

6. Review procurement programmes and budgets as well as formulate observations and recommendations;

7. Issue an opinion on some exceptions to open tender provided for in Article 54 of the Law, except for its clauses IV and XII;

8. Issue internal policies and guidelines on procurement, taking into consideration the proposals made by the central committee;

9. Promote policies concerning the consolidation of procurement, and terms of payment;

10. Analyse, on a quarterly basis, reports on the ruled cases submitted by the procurement units, as well as the general outcomes of procurement;

11. Apply, disseminate and monitor compliance with the Law, the Regulations and other applicable provisions.

Source: Regulation on Public Procurement Law: http://www3.contraloriadf.gob.mx/prontuario/index.php/normativas/Template/ver_mas/62838/48/2/1

The composition of the procurement committee is more or less similar at all levels (central, delegation and government entity). All members can speak, however not all of them can vote. Table 7.1 provides a description of members of a procurement committee and their rights. Officials from the Office of the Comptroller do have not the right to vote in those committees which is in line with international best practices since they are also auditing the procurement procedures. For direct award, despite the fact that procurement committees might act as the first line of defence, no specific and deep controls are performed before the award of the contract. As noted, around 85% of procurement in Mexico City involved exceptions to competitive tenders in 2016. This high share of exceptions casts some doubt on the efficacy of the system. Mexico City should enhance the control on exceptions to competitive procedures and consider the possibility of publishing their justification.

7.2.3. Encouraging the digitalisation of the procurement system by developing a comprehensive e-procurement system.

E-procurement, the use of information and communication technologies in public procurement, can increase transparency, facilitate access to public tenders, reduce direct interaction between procurement officials and companies, increasing outreach and competition, and allow for easier detection of irregularities and corruption, such as bid- rigging schemes (OECD, 2016[4]). The digitalisation of procurement strengthens internal anti-corruption controls and detection of integrity breaches, and provides audit services trails that may facilitate investigation activities (see Box 7.4 for details on how Korea’s e-procurement system fostered transparency and integrity).

In 2002, Public Procurement Service (PPS), the central procurement agency of Korea, introduced a fully integrated, end-to-end e-procurement system called KONEPS. This system covers the entire procurement cycle electronically (including a one-time registration, tendering, contracts, inspection and payment) and related documents are exchanged online.

According to PPS, the system has boosted efficiency in procurement and significantly reduced transaction costs. In addition, the system has increased participation in public tenders and has considerably improved transparency, eliminating instances of corruption by preventing illegal practices and collusive acts. For example, on KONEPS, the Korea Fair Trade Commission runs the Korean BRIAS system, an automated detection system for detecting suspicious bid strategies. According to the integrity assessment conducted by Korea Anti-corruption and Civil Rights Commission, the Integrity Perception Index of PPS has improved from 6.8 to 8.52 out of 10 since the launch of KONEPS.

Source: (OECD, 2016[3]), Preventing Corruption in Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Corruption-in-Public-Procurement-Brochure.pdf.

When using federal funds, contracting authorities (CAs) are subject to the LAASSP (the federal public procurement law) and are required to use the federal e-procurement platform, CompraNet. However, when CAs are using local funds (69% of the total funds), Mexico City has not yet developed an end-to-end e-procurement system, which is under development. Many provisions of the PPL and the PWL mention the possibility of using electronic means in the procurement process, but in practice, most of the communication between suppliers and contracting authorities is performed by mail and face-to-face meetings, which increases the risk of corruption in procurement activities.

The development of the E-procurement system is co-ordinated by the Ministry of Finance (Secretaría de Finanzas) and the Administrative Office of the Government of Mexico City (Oficialía Mayor), the administration Office of the Government of Mexico City in charge of the internal administration of the Public Administration (human and material resources). The main objective of the system is to have in place an automated, transparent and modern electronic tool to prevent corruption. According to the Office of the Comptroller-General, the E-procurement system of Mexico City will be implemented in seven phases: 1) publication of an agreement by the Head of the Government of Mexico City to oblige all CAs to use the E-procurement system; 2) Mexico City will procure the necessary hardware and software; 3) decision by a commission in charge of regulating prices of the goods and services that will be procured through the e-procurement system; 4) creating a registry of suppliers; 5) definition of the administrative units that will use the system; 6) training public officials on the new system; 7) operating the system.

However, during the fact-finding mission, the different stakeholders did not provide information on the timeline for the implementation of the system or on its functionality. Some functionalities, such as e-submission, are crucial for preserving the integrity of the system. Although the main goal of the system is to prevent corruption acts and integrity breaches, it seems that not all goods and services will have to be procured through the system, which could compromise the integrity of the system. Mexico City should consider developing an end-to-end e-procurement system used by all contracting authorities and for the procurement of all goods and services, but also for public works.

7.2.4. Mexico City could benefit from implementing and enhancing electronic tools such as electronic price catalogues and suppliers’ registries.

Electronic price catalogues of goods and services in common use are a powerful tool not only for avoiding mismanagement and waste of public funds but corruption. CAs will have to use the price established in the catalogue as a reference price for market analysis. Funds are then better accounted for and used for their intended purpose. This is a common practice in OECD countries, for instance, to fight corruption. In Italy, the National Anti-corruption Authority, ANAC, has been empowered to determine reference prices (G20, 2016[5]).

In Mexico City, Article 6 of the PPL stipulates that the Administrative Office of the Government of Mexico City (Oficialía Mayor) must establish an electronic price catalogue for goods and services in common use; this catalogue should be updated regularly to perform an efficient market analysis. However, a price catalogue has not yet been developed, despite the fact that this provision has been included in the legal framework since April 2010. To comply with the PPL and enhance the integrity of the system, the Administrative Office of the Government should make the price catalogue available without delay.

The Ministry of Public Works implemented a similar concept, known as the “Costs tab” (Tabulador de precios), a price catalogue for goods and services related to public works. This catalogue should be used by all CAs in Mexico City to evaluate project costs, but also for bid evaluations in a tender procedure. To set the reference price, the Ministry of Public Works sends requests for quotation (RFQs) only to suppliers located in Mexico City, although no restrictions prevent suppliers from other states to participate in procurement opportunities in the city. To establish an appropriate estimate of reference prices, the Ministry of Public Works should consider reviewing its methodology by sending RFQs not only to suppliers located in Mexico City but also to relevant ones in other states.

An additional electronic tool to avoid waste of public funds is the establishment of a suppliers’ registry. Usually this registry is used to compile and store legal and financial information on suppliers, together with their field of activity and the categories of goods and services they can supply. An efficient suppliers’ registry should be updated regularly and include information on suppliers’ performance on public contracts, including information on integrity breaches, so CAs can select only reliable suppliers complying with integrity standards (see Box 7.5 for an example of the suppliers registry in the United States).

The System for Award Management (SAM, www.sam.gov) is a free website owned and operated by the US government that consolidates the capability of various legacy databases and systems used in federal procurement and awards processes. For information on suppliers, it covers the following systems:

-

The Central Contractor Registration (CCR) is the federal government’s primary vendor database, which collects, validates, stores, and disseminates vendor data in support of agency acquisition missions. Both current and potential vendors are required to register in the CCR to be eligible for federal contracts. Once vendors are registered, their data are shared with other federal electronic business systems that promote paperless communication and co-operation between systems. The information and capabilities of CCR are gradually being transferred into SAM.

-

The Excluded Parties Lists System (EPLS) was a web-based system that identified parties excluded from receiving federal contracts, certain subcontracts and certain types of federal financial and non-financial assistance and benefits. The EPLS was updated to reflect government-wide administrative and statutory exclusions, and also included suspected terrorists and individuals barred from entering the United States. The user was able to search, view, and download current and archived exclusions. All the exclusion capabilities of the EPLS were transferred to SAM in November 2012. Furthermore, federal agencies have been required since July 2009 to post all contractor performance evaluations on the Past Performance Information Retrieval System or PPIRS (www.ppirs.gov). This web-based, government-wide application provides timely and pertinent information on a contractor’s past performance to the federal acquisition community for making source selection decisions. PPIRS provides a query capability for authorised users to retrieve report card information detailing a contractor's past performance. Federal regulations require that report cards be completed annually by customers during the life of the contract. The PPIRS consists of several sub-systems and databases (e.g. the Contractor Performance System, Past Performance Data Base, and Construction Contractor Appraisal Support System).

Source: (OECD, 2013[6]), Colombia: Implementing Good Governance, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris.

In Mexico City, Articles 14.2 to 14.7 of the PPL provide for the development by the Administrative Office of the Government of Mexico City (Oficialía Mayor) of a suppliers’ registry (padrón de proveedores) for goods and services (www.proveedores.cdmx.gob.mx). The pilot phase started with the participation of few suppliers. Suppliers can register online by sending all information electronically. They will be then “pre-registered” and a disciplinary body composed of accountants and lawyers will be responsible for analysing the information and authorising the final registration of suppliers. To be registered, suppliers must submit documents including a written declaration under oath that they do not fall into any of the categories described in Article 39 of the PPL concerning breaches of integrity (see section 7.4).

The Ministry of Public Works has already implemented such a registry. However, it is not considered an electronic registry for two reasons: 1) suppliers must send their documents by mail, meaning that it is not possible to register online; 2) the registry is not managed electronically; the Ministry uploads the new list of suppliers with whom CAs can enter into contract every month, adding the recently registered suppliers and deleting the ones whose registration was cancelled. The list published online carries only the registration number and name of each supplier. The Ministry of Public works could benefit from implementing a full electronic suppliers’ registry with constantly updated information; and adding additional information on the list of suppliers such as the field of work, the identification number provided by the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit and the names of the managers. Indeed, adding information can enable procurement officials find out whether they are in a potential conflict of interest situation.

7.2.5. Enforcing the provisions of the Transparency Law to access procurement information.

Transparency is critical for minimising the risks inherent in public procurement. It is also a key mechanism to enhance integrity by helping to hold all stakeholders accountable for their actions. In addition to the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement (OECD, 2015[2]), the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity also promotes “transparency and an open government, including ensuring access to information and open data, along with timely responses to requests for information” (OECD, 2017[7]). A timely degree of transparency should be observed in each phase of the public procurement cycle from procurement planning to payment of the contract. It includes publishing information on procurement plans, tender documentation, award decisions, contract amendments and completion of the contract.

In May 2016, in line with the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement, Mexico City adopted the Law on Transparency, Access to Public Information and Accountability (Ley de Transparencia, Acceso a la Información Pública y Rendición de Cuentas de la Ciudad de México, or LTAIPRC). This contains provisions governing transparency in public procurement, in particular Articles 121 and 141 mandating contracting authorities (CAs) to publish procurement information on their website (see Box 7.6 for information all CAs are required to make available on their website).

a) For open and restricted tenders:

-

1. The call for tender or invitation issued, as well as the legal grounds applied to carry out the procedure;

-

2. names of participants or suppliers invited;

-

3. name of the winner and a justification;

-

4. the area in charge of the procedure and the one in charge of the performance of the contract;

-

5. calls and invitations published;

-

6. award notice/decision;

-

7. the contract, date, amount and delivery time/performance of the services or public works;

-

8. monitoring and supervision mechanisms, including urban and environmental impact studies, as appropriate;

-

9. the budget item, in accordance with the classifier by object of expenditure, if applicable;

-

10. origin of resources specifying whether they are federal, or local, as well as the type of participation fund or respective contribution;

-

11. modifying agreements that, if applicable, are signed, specifying the object and date;

-

12. reports of physical and financial progress on the works or services contracted;

-

13. the termination agreement;

-

14. the settlement;

b) Direct awards:

-

1. the proposal sent by the bidder;

-

2. the justification and legal grounds for carrying out the procedure;

-

3. the authorisation of the exercise of the option;

-

4. where applicable, the price quotations, specifying the names of the suppliers and the amounts;

-

5. the name of the natural or legal person to whom the contract was awarded;

-

6. the requesting administrative unit and the person responsible for its execution;

-

7. the number, date, amount of the contract and period of delivery or execution of the services or work;

-

8. monitoring and supervision mechanisms, including, where appropriate, urban and environmental impact studies, when appropriate;

-

9. progress reports on contracted works or services;

-

10. the termination agreement.

Source: Law on transparency, access to public information and accountability of the city of Mexico, http://www.infodf.org.mx/documentospdf/Ley%20de%20Transparencia,%20Acceso%20a%20la%20Informaci%C3%B3n%20P%C3%BAblica%20y%20Rendici%C3%B3n%20de%20Cuentas%20de%20la%20Ciudad%20de%20M%C3%A9xico.pdf.

The institute in charge of monitoring compliance with the LTAIPRC is INFODF (Instituto de Acceso a la Información Pública y Protección de los Datos Personales de la Ciudad de Mexico). This autonomous entity supervises access to information, guaranteeing the fundamental right of all citizens to share, investigate and request public information and participate in the policy-making process. It opens up public organisations’ information to citizens by publishing timely, verifiable, comprehensive, accessible, updated and complete information in an appropriate format.

Each government entity should have a “Transparency” section on its website, where information is published and classified by article of the LTAIPRC. When looking for procurement information, users need to know the articles of the LTAIPRC related to procurement and then search for the information needed. The system currently in place is not user-friendly, since it requires knowing the LTAIPRC or entails extra research to understand under which articles the information can be found. Furthermore, after several verifications, it seems that the Law on Transparency, Access to Public Information and Accountability is not applied in its entirety, since information is missing and not published online, reducing the transparency and the efficiency of the system in all the procurement phases. This also holds for the tender preparation phase, since CAs do not publish information on their procurement plans which is crucial for engaging suppliers and ensuring the perfect match between demand and supply but also in ensuring that all suppliers have the same level of information. Mexico City should consider enforcing the Transparency Law and implementing a user-friendly website where potential suppliers, civil society and other stakeholders can access the information.

7.2.6. Encouraging the use of the open contracting portal by all contracting authorities

Another initiative implemented in Mexico City is the Open Contracting Partnership, which is about publishing and using open, accessible and timely information on public procurement. The publication of information and its use enables a better engagement, participation and also allows for monitoring of public spending by civil society and other stakeholders (Box 7.7 describes the benefits of open contracting and provides concrete evidence-based examples).

Mexico City is the first city in the world where some contracting authorities publish contracting information on the planning, tendering, awarding and implementation stages using the Open Contracting Data Standard through the open contracting portal (http://www.contratosabiertos.cdmx.gob.mx/contratos) which was launched in 2016. In the first semester of 2017, only three CAs were registered in the platform: The Ministry of Finance (Secretaría de Finanzas), the Oficialía Mayor and the Ministry of Public Works (Secretaría de Obras). The Ministry of Public Works was using an accounting and budgeting system SICOP (Sistema de Contabilidad y Presupuesto) which had functions similar to the open contracting portal, allowing for monitoring of the physical and financial progress of public works. Users, such as officials from the Office of the Comptroller (Contraloría de la Ciudad de Mexico), found this system very useful for conducting their activities. However the system was ended recently, which might be explained by the fact that the Ministry of Public Works joined the open contracting portal.

An effective enforcement of the LTAIPRC is key to enhance the transparency of the system at the CAs’ level, but the Open Contracting platform could have a greater impact. It would make procurement information centralised, publicly available and reusable, which is crucial for policy makers, civil society and the private sector. Mexico City should then encourage the use of the open contracting portal by all CAs of the city.

The benefits of open contracting

Publishing and using structured and standardised information about public contracting can help stakeholders to:

-

deliver better value for money for governments,

-

create fairer competition and a level playing field for business, especially smaller firms,

-

drive higher-quality goods, works, and services for citizens,

-

prevent fraud and corruption,

-

promote smarter analysis and better solutions for public problems.

This public access to open contracting data builds trust and ensures that the trillions of dollars spent by government results in better services, goods and infrastructure projects.

The evidence so far

In Slovakia, full publication of government contracts helped expose wasteful spending, fraud and also led to a significant increase in competition for other contracts subsequently, encouraging small businesses and public innovation.

Openness pays huge returns on investment. South Korea’s transparent e-procurement system KONEPS saved the public sector USD 1.4 billion in costs. It also saved businesses USD 6.6 billion. Time taken to process bids dropped from 30 hours to just two.

7.2.7. Extending deadlines for economic operators to submit their bids.

Enhancing the access to public procurement opportunities by potential economic operators of all sizes is crucial to get the best value for money through fair competition. In addition to the publication of procurement information, including procurement plans and tender opportunities, another key factor influencing the participation of economic operators in public procurement is the deadline set by contracting authorities for potential suppliers to submit their bid. Longer deadlines enhance the competition among bidders and can reduce opportunities for corruption. Indeed, with longer deadlines: 1) more economic operators will be aware of procurement opportunities and 2) suppliers may have more time to prepare their bids and thus to submit them.

The public procurement regulatory framework of Mexico City foresees tight deadlines that can limit the participation of suppliers to tender opportunities. For instance, Article 43 of the PPL mentions that tender documents should be available only for a minimum of three days after the publication of the tender notice; Article 44 foresees that in the event of changes to the tender documents occurring after the bid opening session, suppliers have up to three days to adjust their economic proposal. No data is publicly available, and none was provided to assess the real time offered to suppliers to submit their bids; however, to enhance competition and the integrity of the system, Mexico City should consider extending the deadlines set in its regulatory framework to enhance the participation of suppliers in procurement opportunities (see Box 7.8 for examples of time limits to submit bids in Mexico at the federal level and in the European Union).

Mexico:

At the federal level, the minimum time limit to submit a bid for international tenders in set to 20 calendar days, while for national tenders, it is set at 15 days.

European Union:

Open procedure

In an open procedure, any business may submit a tender. The minimum time limit for submission of tenders is 35 days from the publication date of the contract notice. If a prior information notice is published, this time limit can be reduced to 15 days.

Restricted procedure

In a restricted procedure, any business may ask to participate, but only those who are pre-selected are invited to submit a tender. The time limit to request participation is 37 days from the publication of the contract notice. The public authority then selects at least 5 candidates with the required capabilities, who have 40 days to submit a tender from the date when the invitation was sent. This time limit can be reduced to 36 days, if a prior information notice has been published.

Source: http://europa.eu/youreurope/business/public-tenders/rules-procedures/index_en.htm.

7.2.8. Introducing pre-publication for tender documents, to enhance competition and the integrity of the system.

A crucial tool for enhancing access to procurement opportunities is the publication of a prior information notice and the pre-publication of tender documents. This is generally regarded as a best practice: 1) to make the maximum number of suppliers aware of upcoming procurement opportunities, and 2) to give potential suppliers opportunities to provide comments on tender documents before they are formally published. This ensures efficient competition and avoids such integrity breaches as tailored technical specifications. There is no specific rule or timeline for the pre-publication of tender documents or the publication of pre-information notices. However, the sooner the contracting authority (CA) acts, the greater the impact will be for competition and for integrity.

The legal framework of Mexico City does not include provisions regulating the publication of a pre-information notice or the pre-publication of tender documents. CAs in the city therefore do not use them. The city’s legal framework only includes provisions regulating clarification meetings, where potential bidders can ask the CA to clarify specific aspects of the tender documents. This can lead to changes to the tender documentation. Introducing tools such as the pre-information notice or the pre-publication of tender documents could enhance the integrity of Mexico City’s procurement system and access to procurement opportunities.

7.3. Preserving integrity and promoting a culture of integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers and civil society

Procurement officials should demonstrate high ethical standards and moral values, professionalism, performing their duties based on principles of fairness and non-discrimination. Safeguarding integrity is crucial to curb corruption in the public procurement.

7.3.1. Developing a tailored anti-corruption strategy for public procurement.

After the adoption of the new constitution of Mexico City on January 2017, which granted greater political autonomy to the city, a series of anti-corruption and integrity reforms together with a Local Anti-corruption System are being implemented. On May 2015, a Decree was published in Mexico’s Federal Official Gazette by which several provisions of the Constitution were amended, added or repealed, to prevent and detect corruption and, to sanction administrative responsibility, but also to control public resources with the final goal of eradicating corrupt practices (see Chapter 1).

Given that public procurement is a high-risk area for corruption and integrity breaches, many countries have developed a targeted anti-corruption strategy or law for procurement. Both Austria (see Box 7.9) and Mexico at the federal level have instituted one, although Mexico’s was abrogated when the General Law of Administrative Responsibilities (Ley General de Responsabilidades Administrativas) took effect (see Box 7.10). However in Mexico City, public procurement was not addressed directly in the anti-corruption system. During the fact-finding mission, it was noted that the PPL and PWL will be revised at a later stage, after the integrity reforms are adopted. Mexico City could then benefit from drafting an anti-corruption strategy for public procurement, in line with the anti-corruption system and integrity reforms and after reviewing its regulatory framework for procurement.

Integrity is at the heart of the Anti-corruption Strategy developed by the Austrian Federal Procurement Agency (BBG), and embodied in the following actions:

-

Set precise organisational procedures (clear definition of roles and structures).

-

Incorporate anti-corruption measures into workday life.

-

Constantly reassess and improve the strategy.

-

Constantly raise the awareness of staff.

-

Sharpen the focus on the consequences of corruption.

The Strategy contains an explicit regulation of the main values and strategies for preventing corruption, clear definition of grey areas (e.g. the difference between customer care and corruption), clear rules on accepting gifts, and rules on outside employment. It also sets out for employees a clear understanding of emergency management.

Source: (OECD, 2016[3]), Preventing Corruption in Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Corruption-in-Public-Procurement-Brochure.pdf.

The Federal Anti-corruption Law on Public Procurement (Ley Federal Anticorrupción en Contrataciones Públicas, LFACP), adopted in June 2012, has the following provisions to address issues of corruption and fraud:

-

Penalties and liabilities for both Mexican and foreign individuals and government entities for violating the law while participating in any federal procurement process, and also applying to other related professions that may have an influence on the integrity of the public procurement process (including, but not limited to, public servants).

-

Mexican individuals and government entities involved in corruption in international business transactions are equally liable.

-

Acts such as influence, bribery, collusion, omission, evasion, filing false information and forgery are considered infractions (Article 8).

-

Penalties for violation of the law include fines and legal disqualification (inhabilitación) from the relevant working sector for periods ranging from three months to eight years for individuals and three months to ten years for government entities (Article 27).

-

Pleading guilty and co-operating in the investigation reduces the sanctions by up to 50%, if the plea is submitted within 15 working days after the notification of the administrative disciplinary proceedings (Articles 20 and 31).

-

The identity of whistle-blowers must remain confidential (Article 10).

Source: (OECD, 2015[8]), Effective Delivery of Large Infrastructure Projects: The Case of the New International Airport of Mexico City, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The integrity of the procurement system is ensured by several provisions in the PPL and PWL, such as the establishment of procurement committees and Citizen Comptrollers, the blacklisting of suppliers and also oversight of procurement plans and budgets by Mexico City’s Ministry of Finance (Secretaría de Finanzas). However, the procurement regulatory framework also includes provisions threatening the integrity of the system, such as giving suppliers short deadlines for submitting their bids (see Section 7.2) and also provisions increasing the risk of collusion: 1) clarification meetings with written and oral questions; 2) public meetings to present tender results, offering suppliers the possibility of presenting a better offer during the meeting; 3) allowing bidders to attend the bid opening meeting; 4) organising of joint site visits for bidders when required in the tender. The OECD Guidelines for Fighting Bid Rigging in Public Procurement (OECD, 2009[9]) recommends avoiding bringing potential suppliers together by holding regularly scheduled pre-bid meetings. Mexico City could benefit from reviewing its procurement framework in the light of international best practices and integrity reforms.

Many other laws govern the integrity of the public procurement system (see Chapter 3). They include Article 47 of the Federal Law of Public Servants’ Responsibilities (abrogated) (Ley Federal de Responsabilidades de los Servidores Públicos, or LFRSP), Articles 7 and 8 of the Federal Law of Public Servants’ Administrative Responsibilities (Ley Federal de Responsabilidades Administrativas de los Servidores Públicos, or LFRASP) and Articles 21, 43, 44, 45, 59 and 70 of the General Law of Administrative Responsibilities (Ley General de Responsabilidades Administrativas, or LGRA).

-

Article 47 (abrogated) of the LFRSP determines obligations and duties of public servants, including public procurement officials.

-

Article 7 of the LFRASP mentions the responsibility of public officials to perform their duties in compliance with the LFRSP, and following the principles of lawfulness, honesty, loyalty impartiality and efficiency of the public service.

-

Article 8-XII of the LFRASP describes the “gift policy”, prohibiting public officials to receive and accept gifts, favours, jobs.

-

Article 57 (abrogated) of LFRSP stipulates that every public official may report, in writing to the internal control department of each CA, any breaches entailing the administrative responsibility of other public officials.

-

Article 49 (abrogated) of LFRSP stipulates that every government entity should have a unit where everyone can report breaches (including integrity breaches) by public officials for their obligations.

-

Article 43 of LGRA and LRA of Mexico City creates the regime for public servants participating in public procurement.

-

Article 44 of the LGRA and LRA of Mexico City established the obligation to issue and implement a protocol for public procurement by the Co-ordination Committee of the national and local Anti-corruption System.

-

Article 59 of the LGRA and the LRA of Mexico City establishes open-term contracting as a serious offence.

-

Article 70 of the LGRA and LRA of Mexico City establishes collusion in public procurement as individual act and as a serious offence.

All procurement officials must comply with all the provisions of the LFRSP, but many provisions are directly linked to public procurement (see Box 7.11).

Article 21. The Secretariats may sign collaboration agreements with natural or legal persons participating in public contracting, as well as with chambers of commerce or industrial or trade organisations, with the aim of guiding them in setting up self-regulation mechanisms that include the implementation of internal controls and an integrity programme to ensure the development of an ethical culture in their organisation.

Article 43. The National Digital Platform will include a list of the names and affiliation of the public servants who are involved in public procurement procedures, whether in the processing, attention and resolution for the award of a contract, granting of a concession, licence, permit or authorisation and its extensions, as well as the alienation of movable assets and those that rule on appraisals, which will be updated every two weeks. The formats and mechanisms for recording the information shall be determined by the Co-ordinating Committee. The information referred to in this Article shall be made available to the public on an Internet portal.

Article 44. The Co-ordinating Committee shall issue the protocol of action in contracting that the Secretariats and the internal control bodies shall implement. This protocol of action must be complied with by the public servants registered in the National Digital Platform. Where applicable, they will apply the formats individuals use to declare business, personal or family ties or relations, as well as possible conflicts of Interest, under the principle of maximum publicity and in the terms of the applicable regulations on transparency. The National Digital Platform system shall include the list of individuals, natural and legal persons, who are barred from contracts with public bodies arising from administrative procedures other than those provided for by this Law.

Article 45. The Secretariats or internal control bodies shall supervise the execution of public procurement procedures by the contracting parties, to ensure that they are carried out in accordance with the relevant provisions, carrying out the appropriate checks if they discover anomalies.

Article 59. A public servant who authorises any type of hiring, as well as the selection, appointment or designation, of anyone prevented by legal provision or disqualified by a resolution of the competent authority from occupying a job, shall be responsible for improper hiring, position or commission in the public service or disqualified from contracting with public bodies, provided that in the case of disqualifications, at the time of authorisation, they are registered in the national system on the National Digital Platform listing public servants and individuals who have been subject to sanctions.

Article 70. An individual who executes with one or more private parties, in matters of public contracting, actions that involve or have the object or effect of obtaining an undue benefit or advantage in federal, local or municipal public contracting, shall be deemed to collude. Collusion shall also be considered to be collusion when individuals agree or enter into contracts, agreements, arrangements or combinations between competitors, the object or effect of which is to obtain an undue advantage or to cause damage to the tax authorities or to the assets of public bodies. When the infraction has been carried out through an intermediary with the intent to obtain some benefit or advantage in the public procurement in question, both shall be punished under this Law. […]

Articles 21, 43, 44, 45, 59 and 70 of the LRA of Mexico City are aligned with the public procurement provisions of the LGRA.

Source: The General Law on Administrative Responsibilities.

7.3.2. Encouraging integrity among procurement officials through tailored training programmes and developing a clear integrity capacity strategy.

Public procurement is increasingly recognised as a strategic profession, playing a key role in preventing mismanagement, waste and potential corruption. The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement recommends that adherents to ensure that procurement officials meet high professional standards for knowledge, practical implementation and integrity by providing a dedicated and regularly updated set of tools to require high standards of integrity for all stakeholders in the procurement cycle. All actors involved in the procurement process should demonstrate high standards of integrity, to cultivate integrity in the procurement process (OECD, 2015[2]).

A prerequisite for any institution is the clear identification of officials working in public procurement. Mexico City could not provide information on the size of the public procurement workforce. However, the Oficialía is conducting a diagnostic evaluation of public procurement officials, collecting detailed information on their background. As a first step, Mexico City should clearly identify all officials involved in the procurement process, so strategies can be formulated to enhance the system’s integrity and efficiency.

The Administrative Office of the Government of Mexico City (Oficialía Mayor) and the Office of the Comptroller-General (Contraloría de la Ciudad de México) have been providing training on public procurement to enhance understanding of public procurement processes. The Office of the Comptroller-General organised those training sessions with Mexico City’s School of Public Administration (Escuela de Administración pública de la ciudad de Mexico). However, information gathered in the fact-finding mission suggests that integrity issues are not directly covered in the training.

In 2014, in addition to those courses, at the request of the Administrative Office of the Government of Mexico City (Oficialía Mayor), a certification programme for public procurement officials was established in the School of Public Administration to ensure that the officials have the knowledge, experience and capacity for their duties. This certification also covered integrity issues, but was intended only for directors (strategic level) and heads of units (operational level), not for all public procurement officials. Mexico City should generalise the certification to all levels of officials working on public procurement, tailoring the programme to their responsibilities, with a focus on integrity.

In the capacity-building area, developing e-learning tools is a relatively cost-efficient way to increase capacity. The Office of the Comptroller-General runs online courses covering topics including public procurement, public ethics, and public works. The courses are intended for the general public and civil society, but can also be undertaken by public officials. However, the courses are not accessible online, which undercuts the efforts of the Office of the Comptroller-General to develop the training. For this initiative to bear fruit, the Office of the Comptroller-General should leverage its IT system to ensure the constant availability online of e-learning courses. Moreover the city’s Public Administration School provides online courses covering integrity issues. It seems from information provided during the fact-finding mission that their content was theoretical rather than relevant to the daily work situations public officials encounter in exercising their duties. E-learning courses tailored to public procurement officials’ daily work situations could be helpful.

7.3.3. Promoting transparency and a merit-based approach to hiring, and generalising use of the EPI to all the city’s procurement officials.

In addition to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity promotes a merit-based approach by employing professional, qualified people with a deep commitment to integrity in public service. For transparency, all vacant positions of public officials should be published online and a competitive process should be instituted, to ensure a merit-based approach. Mexico City does not have a civil service career in the public sector (see Chapter 3) and thus, except for unionised officials, public officials have contracts of limited duration. The law stipulates that any posts vacant be published on the government entities’ website and a competitive selection process be carried out, but not all entities apply the law. This holds true for public procurement officials. Mexico City should then consider promoting transparency and a merit-based approach in its hiring procedures.

In July 2016, Mexico City introduced a new recruitment evaluation mechanism: the Integral and Preventing Evaluation, EPI (Evaluación Preventiva Integral). The EPI (see Box 3.11) is intended to evaluate public officials’ behaviour starting at the recruitment stage, and continuing to the termination of employment. It consists of four evaluations seeking to measure public officials’ level of trust, reliability, integrity and professional competences: with a psychometric test, psychological test, socio-economic investigations and polygraph examinations.

The EPI is not used for all procurement officials, however. It is not applicable either 1) for unionised officials, officials working in ministries, territorial demarcations (delegaciones), deconcentrated administrative bodies and other government entities of Mexico City public administration, or 2) for officials moving from one organisation to another without a salary increase. This is intended to ensure the hiring of officials of integrity, but no action is planned for officials already working as procurement officials. Mexico City should consider generalising the use of EPI for procurement officials of all CAs of the city and develop a dedicated mechanism for officials already working as public procurement officials.

7.3.4. Raising awareness in the private sector about the risk of corruption.

Public procurement contracts should contain “no corruption” warranties and measures should be implemented to verify the truthfulness of suppliers’ guarantees that they have not and will not engage in corruption in connection with the contract. One possibility is to include Integrity Pacts for every procurement procedure. These are agreements between the contracting authority offering a contract and the potential suppliers willing to submit a bid. The agreement provides that potential suppliers abstain from bribery, collusion and other corrupt practices for the extent of the contract. The legal representatives of firms are then aware and directly accountable for the unlawful behaviour. In some OECD countries, integrity pacts have been used as an effective tool in fighting corruption.

Article 33 XXI of the PPL foresees that legal representatives of bidders should submit a declaration under oath that they are not under one of the restrictive cases provided for in Article 39 of the PPL and Article 37 of the PWL. These include cases associated with the poor performance of suppliers and their compliance with the PPL, but also cases related to the integrity of the system. If a potential supplier falls in such a case, CAs are prohibited from entering into contract with it (see Box 7.12, describing cases related to integrity breaches). In addition to the declaration under oath, bidders have to submit a declaration that they have no conflict of interest (see section 7.4).

I. Those in which the public servants involved in any way in the bidding and award of the contract has a personal, family or business interest, including those that may be of benefit to them, their spouse or blood relatives until the fourth degree by affinity or civil, or for third parties with whom they have professional, work or business relations, or for partners or companies of which the public servant or the aforementioned persons form or have been a member;

II. Those who hold a job, position or commission in the federal public service or the Federal District, or have performed it until one year before the publication of the call, or date of conclusion of the contract (direct awards), or without the prior written authorisation of the Comptroller in accordance with the Public Servants' Responsibilities Act, as well as persons incapable of performing a job, position or commission in the public service.

V. Those who have provided information that is false, those who have provided information or documentation whose issuance is not recognised by the competent public person or those who have acted with intent or bad faith at some stage of the tender procedure or in the process for the award of a contract, at its conclusion, during its validity, or during the presentation or dismissal of a nonconformity;

VI. Those who have entered into contracts in contravention of the provisions of this Act or those that unjustifiably and for reasons attributable to them do not formalise the contract awarded;

IX. Those that by themselves or through companies that are part of the same business group, make opinions, expert opinions and appraisals, that are required to settle disputes between such persons and the dependencies, deconcentrated bodies, delegations and government entities;

X.- Those that are prevented by resolution of the Comptroller in the terms of Title 5 of this provision and Title Six of the Public Works Act of the Federal District, or by resolution of the Ministry of Public Administration of the Federal Government or of the competent authorities of the governments of the federal entities or municipalities;

XI. Natural or legal persons, government entities’ partners, or their representatives, who are affiliated with others who are participating in the same procedure;

XII.- Those individuals, partners of legal persons, their administrators or representatives, who form or have been a part of the same at the time of committing the infraction, who are prevented by resolution of the Comptroller, the Ministry of Public Administration of the Federal Government or the competent authorities of the governments of the federal entities or municipalities;

XIV. When it is verified by the convenor during or after the tender or restricted invitation or procedure or the conclusion or within the term of the contracts, that some supplier agreed with another or others to raise the prices of the goods or services.

XV. Others that for any reason are prevented from doing so by legal provision.

Source: Mexico City Public Procurement Law, http://www3.contraloriadf.gob.mx/prontuario/index.php/normativas/Template/ver_mas/65234/31/1/1.

Despite these measures, it is still necessary to increase awareness of corruption risks in the private sector. Indeed, raising awareness only for the public sector is not the most efficient approach for ensuring high integrity standards. The public sector can play a key role in fostering the awareness of the private sector by organising trainings and capacity building activities on integrity issues.

In Mexico City, no specific actions have been developed with the private sector to enhance the integrity of the system. In addition to targeting suppliers and potential suppliers directly, by organising awareness- raising sessions and trainings on integrity issues, Mexico City could also benefit from developing measures with chambers of commerce and federations that play a key role in reaching suppliers and raising their awareness.

Potential suppliers should also be encouraged to take voluntary steps to reinforce integrity in their relationship with the government. These include codes of conduct, integrity training programmes for employees, corporate procedures to report fraud and corruption, internal controls, certification and audits by a third independent party. In Mexico, at the federal level, the Ministry of Public Administration (SFP) developed the Business Integrity Programme Model in 2017 (see Box 7.13).

To help design and implement Business Integrity Programmes, in line with the provisions of Article 21 and 25 of the Law on Administrative Responsibilities, the Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de la Función Pública, or SFP) provides a Business Integrity Programme Model.

The document includes suggestions, good practices, general guidelines that the private sector could implement. In addition, it includes also examples of implementation from firms from different sectors.

The main objective of this document is to support the private sector.

Source: (Secretaría de la Función Pública, 2017[10]), Modelo de Programa de Integridad Empresarial, https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/272749/Modelo_de_Programa_de_Integridad_Empresarial.pdf.

7.4. Encouraging public integrity through an effective management of conflict of interest in the procurement process

Integrity in the public sector requires adherence to values and principles ensuring the ethical behaviour of public officials but also from the private sector. Serving the public interest is one of the major missions of governments and public institutions. Public procurement officials are expected to perform their duties with integrity, in a fair, unbiased way. Governments play a key role in ensuring that public officials do not allow their private interests to compromise official decision making and public management.

To guarantee the integrity of the system, public officials need clear guidelines, to ensure a clear identification of conflicts of interest and mechanisms for managing them.

7.4.1. Complementing the general Code of Ethics with a specific code of conduct/code of ethics for procurement officials

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement and the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity recommend requiring high standards of integrity for all stakeholders in the procurement cycle. Those standards can be reflected in integrity frameworks or codes of conduct applicable to public-sector employees. The codes of conduct should clarify expectations and serve as a basis for disciplinary, administrative, civil and/or criminal investigation and sanctions, as appropriate. They can also set out in broad terms the values and principles that define the professional role of the civil service or they can focus on the application of such principles in practice.

In some high-risk areas, officials need specific guidance and standards to mitigate the risks associated with the complexity of the area. Public procurement is one concrete example of such a high-risk area; so developing standards for procurement officials, and in particular, specific restrictions and prohibitions, aim to ensure that officials’ private interests (see Chapter 3) do not improperly influence the performance of their public duties and responsibilities (see Box 7.14 on Canada’s procurement Code of Conduct).

The Government of Canada is responsible for maintaining the confidence of the vendor community and the Canadian public in the procurement system, by conducting procurement in an accountable, ethical and transparent manner.

The Code of Conduct for Procurement will aid the government in fulfilling its commitment to reform procurement, ensuring greater transparency, accountability, and the highest standards of ethical conduct. The Code consolidates the government’s existing legal, regulatory and policy requirements into a concise and transparent statement of the expectations the government has of its employees and its suppliers.

The Code of Conduct for Procurement provides all those involved in the procurement process – public servants and vendors alike – with a clear statement of mutual expectations to ensure a common basic understanding among all participants in procurement.

The code reflects the policy of the Government of Canada and is framed by the principles set out in the Financial Administration Act and the Federal Accountability Act. It consolidates the federal government's measures on conflict of interest, post-employment measures and anti-corruption, as well as other legislative and policy requirements relating specifically to procurement. This code is intended to summarise existing law by providing a single point of reference on key responsibilities and obligations for both public servants and vendors. In addition, it describes vendor complaints and procedural safeguards.

The government expects that all those involved in the procurement process will abide by the provisions of this code.

Source: Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) (n.d.), The Code of Conduct for Procurement, www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/app-acq/cndt-cndct/contexte-context-eng.html (accessed 17 June 2017).

To safeguard the integrity and ethics in Mexico City, the city has three main instruments (see Chapter 3): the Federal Law of Public Servants’ Responsibilities (Ley Federal de Responsabilidades de los Servidores Públicos, or LFRSP), the Ethics Code (Código de Ética de los servidores públicos para el Distrito Federal, or CESPDF) adopted in 2014 and a Charter of Duties of Public Officials (Carta de Obligaciones de los servidores públicos, or COSP). All public officials in Mexico City should follow the provisions specified in those instruments. However, given that public procurement is a high-risk area, Mexico City could benefit from developing a specific code of conduct for public officials working in procurement activities, given that at the federal level, specific guidelines are to be implemented in the context of the National Anti-corruption System.

7.4.2. Generalising conflict of interest policies to all officials working on public procurement and monitoring them effectively.

A conflict of interest arises when individuals or corporations (either in the government or private) is in a position to exploit their professional or official capacity in some way for personal or corporate benefit. Most common conflicts of interest are related to personal, family or business interests and activities, gifts and hospitality, disclosure of confidential information, and future employment. Public procurement positions are thus considered high-risk positions.

The regulatory framework of Mexico City to safeguard the integrity of the system is fragmented (see Chapter 3). Provisions related to conflicts of interest are disseminated in the Law on Administrative Responsibilities, the Ethics Code, and the Charter of Duties of Public Officials. In 2014, complementing its regulatory framework related to integrity, Mexico City developed a conflict of interest policy based on four types of declarations:

-

1. asset declaration

-

2. declaration of conflict of interest

-

3. tax declaration

-

4. declaration of no conflict of interest.

This preventive system aims to reduce significantly integrity breaches in both the public and the private sector. While the three first declarations should be submitted by public officials, the last one (declaration of no conflict of interest) should be submitted by public officials but also by bidders. The three first declarations should be submitted on a yearly basis; but a declaration of non-conflict of interest should be submitted by public officials participating in the procurement activity and the bidders for every tender/ procurement activity.

A first step is to determine which public officials are subject to the different declarations. Table 3.6 in Chapter 3 of this review provides a description of public officials subject to public disclosure in the current conflict of interest legal framework. However, the fact-finding mission suggested that implementation of the different declarations in terms of targeted audience is inconsistent. In some cases, only heads of units submit the declarations, and in other cases, they are submitted by other officials participating in the tender procedure.

From the information collected during the fact-finding mission, five categories of officials are directly involved in the procurement process:

-

1. heads of CAs

-

2. officials in charge of the tender procedure

-

3. officials in the technical area

-

4. officials assisting in the preparation of the procurement procedure (personal de base- unionised)

-

5. members of the procurement committee.

All those officials can have access to information related to a specific procurement procedure and could potentially have an influence in the decision-making process. Mexico City should require all public officials intervening in the procurement process to fill all declarations (when applicable), and in particular a declaration of non-conflict of interest.

The management of conflict of interest in Mexico City consists basically in monitoring public officials’ compliance to submit their declarations of assets, tax and interests rather than implementing within the organisation effective preventing mechanisms to avoid exposing public officials to a conflict of interest.

The Office of the Comptroller performs random checks on some declarations submitted by public officials. However, it has limited staff capacity to conduct checks, and has not developed a strategy targeting in priority high-risk areas such a public procurement and specific procurement procedures. Mexico City should grant the control body access to the information submitted in the different declarations, to monitor the data submitted.

7.5. Strengthening the accountability, control and risk management system for public procurement processes

7.5.1. Strengthening the review system by introducing alternative mechanisms and enhancing the system’s transparency.

Any stakeholder, including unsuccessful tenderers, who believes that the public procurement process was conducted in violation of relevant laws, must have access to an effective review and remedy mechanism. Those mechanisms help build confidence among businesses and increase the overall fairness, lawfulness and transparency of the procurement procedure. The OECD recommends that complaints be handled in a fair, timely and transparent way, by setting up an effective course of action to challenge procurement decisions to correct defects, prevent wrongdoing and build the confidence of bidders, including foreign competitors, in the integrity and fairness of the public procurement system (OECD, 2015[2]).

In Mexico City, bidders may challenge a public procurement procedure by submitting a written request to the Office of the Comptroller five days after the issuance of a decision. The Office of the Comptroller-General must then issue a decision within ten days of an audience. No alternative mechanisms are in effect in Mexico City. The Office of the Comptroller-General did not provide information on the number of challenges to procurement decisions. However, during the fact-finding mission, members of civil society noted that very few challenges are attempted, given the lack of trust in the system. Mexico City should consider introducing alternative mechanisms to improve its remedies system.

Decisions issued by the Office of the Comptroller-General are not published online; but the information can be accessed on request. To improve the transparency of the remedies system, Mexico City would benefit from publishing those decisions.

In many OECD countries, decisions can be challenged by all stakeholders, including civil society and potential suppliers not participating in the procurement procedure. However, in Mexico City, only bidders participating in a procurement procedure can challenge decisions. To enhance trust in the system, Mexico City should consider the possibility of enabling all stakeholders to challenge procurement decisions.

7.5.2. Updating procedure manuals and enhancing the capacity of officials in charge of controlling public procurement activities.

The oversight of procurement activities is essential in supporting accountability and promoting integrity and efficiency in the public procurement process. Without an adequate control system, an environment is created in which assets are not protected against loss or misuse; good practices are not followed; goals and objectives may not be accomplished; and individuals are not deterred from engaging in dishonest, illegal or unethical acts. It is particularly important to have functioning internal controls in procurement, including financial control, internal audit and management control (OECD, 2007[11]). The Office of the Comptroller is the government entity in charge of performing those controls and thus safeguarding the integrity of the system.

In Mexico City, every contracting authority (CA) has a procedural manual approved by the General Co-ordination of Administrative Modernisation (CGMA) which is responsible for determining whether each manual meets basic requirements. When performing controls, officials from the Office of the Comptroller have to verify that procurement activities are in line with requirements set in the manual. However, interviews with stakeholders suggest that the manuals are not always updated and do not take into account external parameters and processes that do not depend on the CAs. Mexico City should consider updating procedure manuals and aligning them with current processes.

Public procurement is no longer considered an administrative activity. To perform controls on procurement activities, officials need to understand the procurement framework and the systems and processes in place. It is crucial for countries and institutions to assess not only the capacity of public procurement officials but of officials in charge of procurement oversight (see Box 7.15).