Chapter 6. How to make apprenticeships work for youth at risk?

This chapter focuses on youth at risk: young people who are unemployed (often called NEET or not in education employment or training) or at risk of such an outcome. It identifies some of the common additional barriers facing such youth, including: weaker literacy, numeracy and general education; lack of work experience; and lack of relevant social networks and soft skills. The chapter critically reviews a number of policy interventions that might serve to increase the likelihood of employers offering apprenticeships to youth at risk, including financial subsidies, apprenticeship duration, preparatory programmes, and personalised support over the programme of training.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Issues and challenges

Apprenticeships can improve the job and life prospects of youth at risk

Apprenticeships have attracted increasing attention as a tool to support effective school-to-work transition, and can help to tackle youth unemployment and inactivity. The benefits of apprenticeships are especially significant for youth at risk, who are most likely to struggle to complete school or find good jobs. In this chapter, youth at risk are defined as youth not in employment, education or training (NEET), and those at risk of becoming NEET. International evidence suggests that apprenticeships may help school-to-work transition: OECD countries with a high share of youth in apprenticeships have lower rates of youth struggling to transition to employment (Quintini and Martin, 2014[1]). In the United States, a review of programme evaluations showed that combining vocational training with work placements can improve labour market outcomes for young people (Sattar, 2010[2]). The benefits of such programmes are sometimes not job-related: programmes involving work placements can help by keeping young people out of trouble and by reducing arrest, incarceration and mortality rates (Gelber, Isen and Kessler, 2014[3]; Sattar, 2010[2]).

Youth at risk are likely to face more challenges to find a placement

For youth at risk, however, finding a good apprenticeship can be difficult. Those living in underprivileged areas often have fewer job opportunities, and family and friends may be jobless or in low skill jobs, limiting the scope for informal connections to employers and recruiters. Even if contacts could be built with employers taking apprentices, one major hurdle remains: ensuring that employers actually offer apprenticeship placements to youth at risk.

The potential of apprenticeships will be realised only if they align with business interests

Some firms may take on young people at risk as apprentices through a desire to help or foster social cohesion in the community. However, employers also need to run a business and make a profit, and few can afford to hire an apprentice if that would generate losses for their enterprise. If the potential of apprenticeships for youth at risk is to be fully realised, programmes must not only provide an opportunity for employers to show social responsibility, but must also be well aligned with their business objectives. This requires a good understanding of the financial implications for employers of taking on youth at risk as apprentices.

One challenge is that youth at risk tend to have weaker skills than their peers

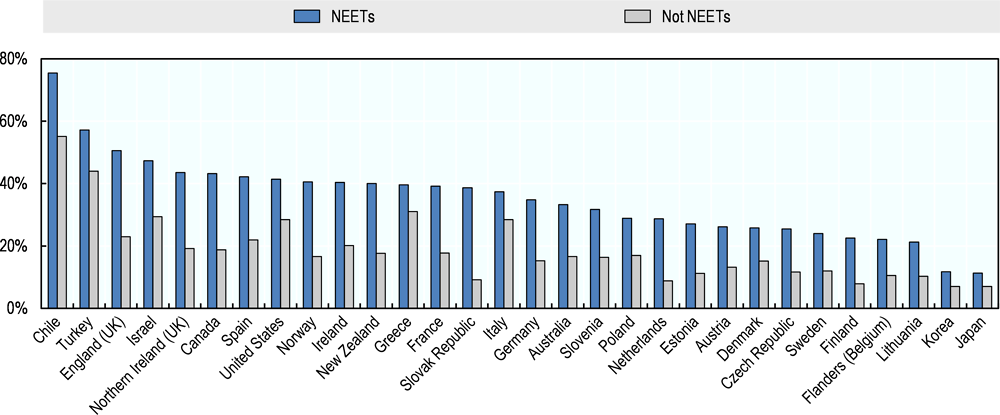

Youth at risk usually have relatively weak skills, which is one reason why employers may be reluctant to take them on as apprentices. Some of these weaknesses will be academic: NEETs tend to have weaker literacy and numeracy skills than young people in education, employment or training (Figure 6.1) Sometimes, the weakness concerns soft skills and personality attributes: studies have found that high school dropouts in the United States, and those who dropped out but completed high school through a second chance programme, had weaker non-cognitive or soft skills in some areas (e.g. persistence and conscientiousness) than those who never dropped out (Heckman and Rubinstein, 2001[4]; Heckman, Stixrud and Urzua, 2006[5]). Such differences between the typical profile of youth at risk and their peers are important for employers, because the skills of apprentices will affect how they perform at work and whether they will be able to successfully complete their training.

Taking on a young person at risk as an apprentice is costlier for employers

Weaker basic skills make apprentices less productive at work – an apprentice in car mechatronics will contribute less to business in a garage if they struggle to browse the vehicle manufacturer’s technical portal. Gaps in soft skills have a similar effect – some apprentices may struggle to arrive on time or handle conflicts with colleagues. Filling those gaps is one of the objectives of an apprenticeship, but it requires time and support, and some will need to catch up with initial weaknesses and may progress more slowly than average. This means that many youth at risk in apprenticeships will need more help to develop the required skills. The implication for firms is fewer benefits through productive work and higher costs in terms of instruction time.

Apprenticeship schemes need to be designed in ways that address the needs of youth at risk, while remaining attractive to employers

To realise the full potential of apprenticeships for youth at risk, it is important to ensure that the prospect of taking on a young person at risk aligns with the business interests of enterprises. This requires shifting the balance of costs and benefits to employers to make it more attractive for them to offer opportunities to this group. International evidence suggests that this is best done through non-financial measures.

Changing the parameters of apprenticeship schemes (e.g. apprentice wages, duration and how apprentices’ time is spent) can help make apprenticeships for youth at risk more attractive to employers. This may be implemented by:

-

Creating a targeted apprenticeship scheme with a modified design that is suitable to the specific needs of youth at risk and is attractive to employers, such as a shorter programme.

-

Putting in place preparatory programmes (pre-apprenticeships) and support measures for youth at risk enrolled on regular apprenticeship schemes.

Policy argument 1: Policy tools are likely to be most effective if they focus on system design and support

Several countries use financial incentives to encourage apprenticeships for youth at risk

Several countries use subsidies or tax breaks to encourage firms to offer apprenticeships to young people who struggle to find a placement. In Austria, firms taking on young people in “integrative apprenticeships” (IBA) receive higher subsidies than other firms, and public resources cover some of the additional training needed by apprentices and trainers in the firm (Wirtschaftskammer Österreich (WKO), 2016[7]). Australia offers a subsidy to those engaging an apprentice from specific groups, such as indigenous Australians and job seekers with severe barriers to employment (Australian Government, 2017[8]). France offers a higher tax break to firms that take on disadvantaged apprentices, including young people without a qualification and youth who have signed a “voluntary integration contract”, which targets those most disconnected from employment (Service-Public-Pro, 2016[9]).

Effectively targeting youth at risk is challenging

As set out in Chapter 2, international evidence offers limited support in favour of financial incentives as a means of encouraging apprenticeship provision. The arguments against subsidies to support youth at risk in apprenticeships are similar. Typically, there are sectors of the economy with labour shortages where employers are very happy to take on youth at risk as apprentices. Such sectors are likely to take advantage of any subsidy available, but it will mostly be deadweight with few additional apprentices being taken on. The evaluation of such a targeted subsidy by Germany illustrates this point. Germany launched a bonus scheme in 2008 that rewarded firms offering an apprenticeship to youth who had failed to find a placement or possessed only lower secondary schooling or less. Despite efforts to reward only additional placements (e.g. the bonus was offered only if the firm offered more placements than they had over the preceding three years), the evaluation of the scheme found that it made a difference to only one in ten cases – the other apprentices would have been hired anyway (Bonin, 2013[10]). The scheme was scrapped in 2010. The amount offered seemed too low to make a difference, and even with the bonus firms faced net costs by the end of the apprenticeship, even more so as disadvantaged participants needed more instruction time. This meant that firms ended up offering placements to young people they intended to hire upon completion, and who, – but in the vast majority of cases, would have been offered a place even without the subsidy (Mühlemann, 2016[11]).

Policy efforts are best focused on measures that do not involve financial incentives

International experience suggests that it is better to focus on tools that make offering apprenticeships to youth at risk attractive to employers, but without giving them money directly. For example, the evaluation of the German bonus scheme found that firms thought that strengthening basic skills among applicants and offering more support to weaker apprentices during training would have been more helpful than a subsidy (Wenzelmann, 2016[12]). Research from Switzerland (Mühlemann, Braendli and Wolter, 2013[13]) suggests that firms are willing to invest extra instruction time in apprentices with poor school grades, at least in occupations where they expect to reap net benefits during the course of the apprenticeship. This suggests that designing programmes in a way that allows firms to at least break even by the end of the training period is important to ensure access to apprenticeships among youth at risk.

Policy argument 2: Programmes can be designed to work for both employers and youth at risk

It is possible to design a programme for youth at risk that also works for employers and apprentices

Research evidence shows that by carefully adjusting the parameters of apprenticeship schemes (e.g. duration, apprentice wage, balance of time spent with the firms vs. at school or college), it is possible to design schemes that work for both youth at risk and employers. Employers need to break even by the end of the apprenticeship, while youth at risk need to develop targeted skills. For example, in Switzerland, firms that offer two-year apprenticeships designed with youth at risk explicitly in mind break even, on average, by the end of the training period. This is achieved while delivering good training: nearly half of completers proceed to higher level apprenticeships, and three-quarters of the remaining half find a job upon completion (Fuhrer and Schweri, 2010[14]). The programme includes various support tools (see Box 6.2).

Shorter programmes with flexible duration may work better for youth at risk

Offering apprenticeships in occupations for which a relatively short duration is suitable may help achieve higher completion rates. In Switzerland, two-year apprenticeships were created for youth at risk (most apprenticeships last three or four years). Austria has a special “integrative apprenticeship” in which apprentices may obtain a partial qualification or take longer to complete than an average apprentice (BMWFW, 2016[15]). As for any apprenticeship, programmes must not become dead ends: upon completion, apprentices should have the possibility to progress to higher levels of training.

Some occupations may fit youth at risk better than others

Employers may be more ready to go the extra mile and help struggling apprentices when they need those apprentices to contribute to production, rather than be left with training costs and few productive benefits. Research has found that in occupations where Swiss firms expected to break even by the end of apprenticeship, more attention was given to apprentices with poor school grades to help them catch up. The opposite occurred in occupations where firms hired apprentices to recruit the best upon completion. In these cases it was the highest performers who received extra training (Mühlemann, Braendli and Wolter, 2013[13]), which is not surprising, as if the key benefit for the firm comes from recruiting the best, they will focus on making the best apprentices even better. The implication is that occupations where firms can obtain benefits during the training period may work better for youth who need extra support. When employers hire apprentices with a view to reap benefits from productive work, rather than the prospect of recruiting them, it is particularly important to ensure that apprentices also learn useful occupational skills and are not exploited as cheap labour – Chapter 5 focuses on this issue.

Two-year apprenticeships (EBA) in Switzerland

These programmes target young people aged 15 and above who have completed lower secondary education, are at risk of dropping out from education and training, or who struggle to find a three or four-year apprenticeship. They are offered in around 60 occupations, such as retail sales assistant, healthcare assistant and hairdresser (SDBB, 2016[16]). Their structure is similar to longer apprenticeships and they combine firm-based and school-based components. EBA apprentices benefit from support measures, such as individual tutoring, remedial courses and support from in-company supervisors (SBFI, 2014[17]).

Those who complete may progress to three or four-year apprenticeships, typically joining the second year of the programme – 41% do so within two years of completion. Among those who do not pursue further training, 75% find employment within six months of completion (SBFI, 2014[17]).

Source: Fuhrer, M., and J. Schweri (2010[14]) “Two-year apprenticeships for young people with learning difficulties: a cost-benefit analysis for training firms”, Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, Vol. 2/22, www.skbf-csre.ch; SBFI (2014[17]), Zweijährige Berufliche Grundbildung mit Eidgenössischem Berufsattest, Staatssekretariat für Bildung, Forschung und Innovation, www.sbfi.admin.ch/berufsbildung; SDBB (2016[16]), Career guidance website “EBA-Beruf – 2-jährige Lehre”, www.berufsberatung.ch.

Integrative apprenticeships (IBA) in Austria

Integrative apprenticeships were introduced in 2003 and accounted for 6% of apprentices in 2014 (Dornmayr, 2012[18]). They target learners with special needs, people with disabilities, and those without a basic school-leaving certificate (BMWFW, 2016[15]). Participants can take longer to complete by one or two years, or may obtain a partial qualification. They receive support both during work placement and at school. The school-based component is adapted to the needs of IBA apprentices: teachers can attend targeted training courses, additional assistance is available to support teaching, and class sizes are reduced. Those in the partial qualification pathway follow individualised curricula and attend smaller classes.

Source: BMWFW (2016[15]), Lehrausbildung in verlängerter Lehrzeit und in Teilqualifikation, www.bmwfw.gv.at/Berufsausbildung; Dornmayr, H. (2012[18]), Berufseinmündung von AbsolventInnen der Integrativen Berufsausbildung, Institut für Bildungsforschung der Wirtschaft, www.bmwfw.gv.at/Berufsausbildung/LehrlingsUndBerufsausbildung.

Youth at risk often need preparatory programmes to get them ready for apprenticeships

When apprentices are well prepared – for example, they have caught up with any gaps in literacy or numeracy, have carefully chosen their target occupation, and are ready to operate and learn in a real work environment – they will be more attractive in the eyes of potential employers and have better chances of completing their training. Many countries pursue extensive pre-apprenticeship programmes to this end.

-

Pre-apprenticeship programmes encourage and offer financial resources to prepare youth at risk for apprenticeships.

-

Given the diversity of approaches in this area, and the limited evidence base, new initiatives should be piloted and evaluated with the most effective programmes rolled out.

Policy argument 1: Pre-apprenticeship programmes can help transition youth at risk into apprenticeships

Pre-apprenticeships can help prepare youth at risk for an apprenticeship programme

Given the many challenges of encouraging employers to offer apprenticeships to young people who are inadequately prepared, an alternative approach is to tackle weaknesses in the skillset of youth at risk before the apprenticeship starts. The objective is to help young people at risk with some of their foundation skills in such a way as to improve their chances of finding a good apprenticeship placement. Such pre-apprenticeships can address weaknesses in literacy or numeracy, develop initial vocational skills, and improve key soft and employability skills. Employers will find better prepared potential apprentices a more worthwhile investment as they will contribute more easily to production, learn faster, need less support to remedy initial weaknesses, and will be less likely to drop out.

Their role is particularly important when an apprenticeship is a pathway within upper secondary vocational education and training (VET)

Pre-apprenticeship programmes, which build a bridge to apprenticeships, are found in many OECD countries (see Table 6.1). In addition to developing academic, vocational and soft skills, programmes often aim to help match participants to available placements by offering career guidance, work placements and job search training. In countries where upper secondary VET is usually delivered through youth apprenticeships (e.g. several countries in continental Europe), failure to find a placement may lead to disconnection from the labour market and learning opportunities. In these countries, pre-apprenticeships act as a bridge between lower secondary and upper secondary education. Sometimes, programmes target youth at risk without links to formal pre-apprenticeship frameworks. For example, in the United States, many programmes are developed by public and private stakeholders, which creates both a rich field of innovation and a challenge for sustaining and upscaling approaches that work.

Policy argument 2: Programmes that allow learners to start apprenticeships outside firms should focus on transition into the regular system

Some countries have programmes that allow young people to start an apprenticeship outside firms

A different approach is to allow young people to start a form of “shadow” apprenticeship without a work placement, and then help them transition into a regular apprenticeship. For example, Austria established special courses (called überbetriebliche Ausbildung [ÜBA]) for young people who cannot find a placement, which provide a shadow apprenticeship based in a workshop that simulates the employer. Around a quarter of participants transition into regular apprenticeships, the remainder obtain the same qualification as apprentices but through a school-based programme (Hofbauer, Kugi-Mazza and Sinowatz, 2014[20]). In Germany, similar programmes (Berufsausbildung in außerbetrieblichen Einrichtungen [BaE]) are offered in several occupations and target disadvantaged youth and those with learning difficulties. After the first year, participants are encouraged to find a regular apprentice position, and those who do not succeed may continue within the programme and obtain a qualification (Bonin et al., 2010[21]).

However, such programmes miss some important benefits of apprenticeships

Such programmes have advantages for young people who cannot immediately find a regular apprenticeship placement as they can start earning a wage and obtain a qualification. However, these programmes lack some of the benefits of regular apprenticeships, for example, participants do not have the same opportunities to develop soft skills as regular apprentices (e.g. they do not interact with real bosses and colleagues). Also, the supply of apprenticeship positions in firms sends a signal about their needs – in these programmes those signals are missed.

Policy argument 3: Given the wide range of approaches in this area, more evaluation evidence would be desirable

Evaluations are essential to identify what works

Pre-apprenticeship programmes tend to be costly, so identifying which approaches work best is essential. If a pre-apprenticeship programme does not develop useful skills it risks becoming stigmatising for participants rather than a pathway to good jobs. Evaluation evidence can help to identify whether a programme works so that successful initiatives can be expanded and unsuccessful ones discontinued.

Obtaining solid evidence is difficult

Even within individual countries, programmes offered often vary in terms of content, duration and funding, so average results may be a poor indicator of the quality of individual programmes. In addition, identifying what would have happened to participants had they not pursued the programme is a challenge. In most countries, all eligible youth willing to enter are provided with access, so a comparison of those offered the programmes and those not offered the programme is not possible. Pre-apprenticeship participants tend to be more disadvantaged and have weaker skills than those who choose other pathways or jobs at the same age (Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2016[22]; Karmel and Oliver, 2011[23]). This means that higher dropout rates from apprenticeships among those who pursued a pre-apprenticeship (as found in Germany) may reflect weaker skills at the outset, rather than the poor quality of pre-apprenticeship programmes. In Australia, evaluations found that the link between pre-apprenticeship participation and apprenticeship completion varied across trades (Karmel and Oliver, 2011[23]).

Youth at risk often require additional support over the duration of the apprenticeship

Youth at risk are more likely to struggle to complete their apprenticeship than an average apprentice, and dropout commonly leads to weak labour market outcomes. It is also costly for employers, who will have invested in finding and training the apprentice and, following a dropout, are left with costs and no chance of benefitting from apprentices’ contributions to productive work.

The difficulties faced by youth at risk during apprenticeships may concern academic coursework, conflict with the training company, or may be of personal nature. To increase the chances of successful completion and help apprentices participate in the training firm’s activities:

-

Youth at risk who undertake apprenticeships should be provided with additional support. This may include remedial courses (e.g. in literacy and numeracy), mentoring and coaching.

-

Employers should be helped to build their capacity to provide apprenticeships to youth at risk. For example, support with how to handle difficulties that may arise with apprentices, and how to deliver training effectively on-the-job (e.g. training for supervisors, online forum for supervisors).

Policy argument 1: Supporting youth at risk during apprentices can benefit both employers and apprentices

Once access to apprenticeship is secured, support is needed to avoid dropout

Many young people at risk find completing an apprenticeship challenging. Data from England (United Kingdom), Germany and Switzerland show that apprentices with a minority background, weak school results and learning difficulties, have higher dropout rates. Soft skills and apprentice motivation are also important, with employers reporting a lack of effort as a common cause for dropout (Gambin and Hogarth, 2016[24]; Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2016[22]; Stalder and Schmid, 2006[25]). Supporting apprentices during their training can help them achieve a qualification, while also benefitting their employers.

Support during apprenticeships benefits employers, which encourages them to offer placements

Youth at risk tend to need more instruction time (creating higher costs for employers), will develop skills more slowly (generating fewer benefits for the firm), and are more likely to drop out. Offering extra support helps apprentices to learn faster and overcome any difficulties, get on better with their employer and school, and have better chances of completion. As a result, employers benefit from better performing apprentices and can reduce the risks of costly dropout. The availability of additional support can encourage employers to hire youth at risk as apprentices. For example, a master carpenter may be reluctant to take on a young person who struggled at school as they may worry about the apprentice not being able to cope with the mathematics needed to work out the rise and run for a staircase. If extra support is available, this may reassure the master carpenter that the apprentice will fit in with the firm.

Schools and mentors can help overcome learning and personal problems

Apprentices may receive help with academic or technical coursework (e.g. remedial courses) or with preparing for exams. Mentors or coaches may help apprentices with everyday problems and act as mediators if problems arise between the apprentice and their firm or school.

Australia

The Apprenticeship Support Network aims to help employers to recruit, train and retain apprentices, and to help apprentices to succeed. Eleven regional networks provide advice and support services for employers and apprentices through universal services for all employers and apprentices, administrative support, payment processing and regular contact, as well as targeted services for those needing additional support. Where there is a risk of non-completion, additional services (e.g. mentoring) will help apprentices and employers to work through difficulties. Those who may be unsuited to an apprenticeship will receive help to find alternative training pathways. Services provided by the Network are funded by the Australian Government and delivered by private providers.

Austria

Training assistants, funded by public resources, work extensively with youth in integrative apprenticeships, which target youth with special needs, disabilities and dropouts from basic schooling. They take care of administrative tasks and prepare the firm for the arrival of the apprentice. During the training period they provide tutorial support and act as mediators if difficulties arise. Most training assistants are trained in special education and have work experience with disadvantaged youth.

Germany

Apprenticeship assistance, funded by government, is offered free of charge to apprentices or dropouts to help them find a way back into apprenticeships. Assistance includes remedial education and help with homework, mentoring to help with everyday problems, and mediation in case of conflict with the school or company. A support plan is established with the apprentice, which typically involves three hours of individual assistance per week, as well as some group sessions.

Switzerland

Apprentices in two-year programmes are entitled to publicly funded individual coaching. Around half of those entitled take up the opportunity, mostly to tackle weak language skills, learning difficulties or psychological problems. Most coaches are former teachers, learning therapists or social workers, and receive targeted training in preparation for their job (e.g. 300-hour training in Zurich).

Source: Kis, V. (2016[19]), “Work-based learning for youth at risk: Getting employers on board”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 150, https://doi.org/10.1787/5e122a91-en; Australian Government (2018[26]), Australian Apprenticeship Support Network, www.australianapprenticeships.gov.au/australian-apprenticeship-support-network.

International evidence suggests support during apprenticeships can work

Evaluating initiatives in this field is difficult because all those who seek support typically receive support. However, there is a great deal of variation within countries as to how initiatives are implemented. Available studies suggest that support for struggling apprentices can help promote successful completion. Studies of Australian apprentices found that the lack of support is a common cause of dropout. Having a credible third party that is available to apprentices facing personal problems or arguments in the workplace can reduce dropout (Snell and Hart, 2008[27]; Deloitte Access Economics, 2014[28]). Support directed to employers can also be very constructive. This may involve improving management capacity within firms so that employers are better able to deal with the challenges of integrating an apprentice into daily activities, training them and handling problems that arise. In Germany, the temporary suspension of mandatory training for apprentice supervisors led to an increase in dropout rates (BIBB, 2009[29]), which led to the re-introduction of the training requirement after a six-year suspension.

Conclusion

The question addressed in this chapter is how apprenticeships can be made to work for youth at risk of poor outcomes, being either out of education and employment or at risk of such a status. There is a solid basis to believe that apprenticeships can help make school-to-work transitions easier for such youth. While many countries offer employer subsidies to take on apprentices with weak academic profiles or from disadvantaged backgrounds, evidence of the efficacy of such financial incentives is unpersuasive. More effective are interventions designed to increase the speed with which a youth at risk apprentice can be expected to become a skilled, productive worker to cover the costs incurred by employers in their training. These include changes to the standard duration of an apprenticeship (either shorter or longer than is normally the case), preparatory programmes to help make a young person more attractive to an apprentice recruiter, or personalised support to tackle problems encountered by an apprentice whilst undertaking the apprenticeship.

References

[26] Australian Government (2018), Australian Apprenticeship Support Network, http://www.australianapprenticeships.gov.au/australian-apprenticeship-support-network (accessed on 5 February 2018).

[8] Australian Government (2017), Australian Apprenticeships, http://www.australianapprenticeships.gov.au (accessed on 30 August 2017).

[22] Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (2016), Bildung in Deutschland 2016 Ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zu Bildung und Migration Bildung in Deutschland 2016, (Group of Writers on Educational Reporting, Education in Germany 2016: An Indicator-based Report with an Analysis Concerning Education and Migration in Germany, W. Bertelsmann Verlag, https://www.bildungsbericht.de/de/bildungsberichte-seit-2006/bildungsbericht-2016/pdf-bildungsbericht-2016/bildungsbericht-2016.

[29] BIBB (2009), “Ausbilder-Eignungsverordnung Vom 21 Januar 2009 ("Trainer aptitude regulations from 21 January 2009")”, Bundesgesetzblatt 5, http://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/ausbilder_eignungsverordnung.pdf.

[15] BMWFW (2016), Lehrausbildung in verlängerter Lehrzeit und in Teilqualifikation, (Extended Apprenticeship Training and Sub-qualification), Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy, http://www.bmwfw.gv.at/Berufsausbildung.

[10] Bonin, H. (2013), Begleitforschung „Auswirkungen des Ausbildungsbonus auf den Ausbildungsmarkt und die öffentlichen Haushalte“, (Accompanying Research "Impacts of the Training Bonus on the Training Market and Public Budgets“), Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Berlin, http://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Publikationen/Forschungsberichte/fb438-Ausbildungsbonus-2013.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

[21] Bonin, H. et al. (2010), Vorstudie zur Evaluation von Fördermaßnahmen für Jugendliche im SGB II und SGB III, (Preliminary Study on the Evaluation of Support Programmes for Young Adults, Codes of Social Law (SGB) II, III: Final Report), Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), Ramboll and INFAS, http://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Publikationen/fb-fb405-evaluation-sgbII-sgbIII.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

[28] Deloitte Access Economics (2014), Australian Apprenticeships Mentoring Package Interim Evaluation, Deloitte Access Economics, Barton, https://www.australianapprenticeships.gov.au/sites/ausapps/files/publication-documents/report_-_aamp_mentoring_package_interim_evaluation.pdf.

[18] Dornmayr, H. (2012), Berufseinmündung von AbsolventInnen der Integrativen Berufsausbildung, (Labour Market Entry of Graduates of Integrative Professional Training), Institute for Research on Qualifications and Training of the Austrian Economy, http://www.bmwfw.gv.at/Berufsausbildung/LehrlingsUndBerufsausbildung.

[14] Fuhrer, M. and J. Schweri (2010), “Two-year apprenticeships for young people with learning difficulties: a cost-benefit analysis for training firms”, Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, Vol. 2/22, pp. 107-125.

[24] Gambin, L. and T. Hogarth (2016), “Factors affecting completion of apprenticeship training in England”, Journal of Education and Work, Vol. 29/4, pp. 470-493, https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2014.997679.

[3] Gelber, A., A. Isen and J. Kessler (2014), “The effects of youth employment: Evidence from New York City Summer Youth Employment Program Lotteries”, NBER Working Paper, No. 20810, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20810.

[4] Heckman, J. and Y. Rubinstein (2001), “The importance of noncognitive skills: Lessons from the GED Testing Program”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 91/2, pp. 145-149, http://jenni.uchicago.edu/papers/Heckman_Rubinstein_AER_2001_91_2.pdf.

[5] Heckman, J., J. Stixrud and S. Urzua (2006), “The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 24, pp. 411-482, http://www.nber.org/papers/w12006.

[20] Hofbauer, S., E. Kugi-Mazza and L. Sinowatz (2014), Erfolgsmodell ÜBA: Eine Analyse der Effekte von Investitionen in die überbetriebliche Ausbildung ÜBA auf Arbeitsmarkt und öffentliche Haushalte, (Success Model ÜBA: An Analysis of the Effects of Investments in External Vocational Training (ÜBA) fort he Labour Market and Public Budgets), WISO, Linz, http://www.isw-linz.at/themen/dbdocs/LF_Hofbauer_Kugi_Sinowatz_03_14.pdf.

[23] Karmel, T. and D. Oliver (2011), Pre-apprenticeships and their Impact on Apprenticeship Completion and Satisfaction, National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), Adelaide, https://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/publications/all-publications/pre-apprenticeships-and-their-impact-on-apprenticeship-completion-and-satisfaction.

[19] Kis, V. (2016), “Work-based learning for youth at risk: Getting employers on board”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 150, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5e122a91-en.

[11] Mühlemann, S. (2016), “The cost and benefits of work-based learning”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 143, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlpl4s6g0zv-en.

[13] Mühlemann, S., R. Braendli and S. Wolter (2013), “Invest in the best or compensate the weak? An empirical analysis of the heterogeneity of a firm's provision of human capita”, Evidence-based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, Vol. 1/1, pp. 80-95, http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/20493981311318629.

[6] OECD (2015), OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), http://www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

[1] Quintini, G. and S. Martin (2014), “Same same but different: School-to-work transitions in emerging and advanced economies”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 154, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jzbb2t1rcwc-en.

[2] Sattar, S. (2010), “Evidence scan of work experience programs”, Mathematica Policy Research Reports, No. 685b2a650bdf4437b1de31c2e, Mathematica Policy Research, Oakland, https://ideas.repec.org/p/mpr/mprres/685b2a650bdf4437b1de31c2e1c9c173.html.

[17] SBFI (2014), Zweijährige Berufliche Grundbildung mit Eidgenössischem, (Two-year Basic Education Culminating in a Federal Vocational Certificate), Swiss State Secretary for Education and Research, https://www.sbfi.admin.ch/dam/sbfi/de/dokumente/leitfaden_zweijaehrigeberuflichegrundbildungmiteidgenoessischemb.pdf.download.pdf/leitfaden_zweijaehrigeberuflichegrundbildungmiteidgenoessischemb.pdf.

[16] SDBB (2016), EBA-Beruf – 2-jährige Lehre (EBA-Professions - Two-year Apprenticeship), (EBA-Professions - Two-year Apprenticeship), http://www.berufsberatung.ch. (accessed on 20 October 2016).

[9] Service-Public-Pro (2016), Crédit d’impôt apprentissage, https://www.service-public.fr/professionnels-entreprises/vosdroits/F31957.

[27] Snell, D. and A. Hart (2008), “Reasons for non-completion and dissatisfaction among apprentices and trainees: A regional case study”, International Journal of Training Research, Vol. 6/1, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.5172/ijtr.6.1.44.

[25] Stalder, B. and E. Schmid (2006), Lehrvertragsauflösungen, ihre Ursachen und Konsequenzen. Ergebnisse aus dem Projekt LEVA, (Cancellation of Apprenticeship Contracts - Causes and Consequences, Results of Project LEVA), https://www.be.ch/portal/de/veroeffentlichungen/publikationen.assetref/dam/documents/ERZ/GS/de/BiEv/ERZ_2006_Lehrvertragsaufloesungen_ihre_Ursachen_und_Konsequenzen.pdf.

[12] Wenzelmann, F. (2016), Lessons from Subsidies in Germany: The Ausbildungsbonus.

[7] Wirtschaftskammer Österreich (WKO) (2016), Wirtschaftskammer Österreich, (Austrian Chamber of Commerce), https://www.wko.at/service/foerderungen/integrative-berufsausbildung-und-teilqualifizierungen.html.