Chapter 6. The local dimension of SME and entrepreneurship policy in Indonesia

This chapter presents information on the local dimension of SME and entrepreneurship policy in Indonesia. It includes information on geographical differences in economic and SME activity, the role of local governments in SME policy, existing mechanisms for the tailoring of national policies to the local context, and mechanisms to ensure policy co-ordination among different levels of government. Indonesia features large local variations in wealth, the business environment, SME and entrepreneurship activity, and enterprise access to strategic resources, which reflect the large size of the population and the geographical expanse of the country. A large-scale devolution of powers in the early 2000s has given significant SME policy functions to local governments, which has helped provide the necessary flexibility to target national policies to the local context. Nonetheless, appropriate tailoring of national policies to local business needs and effective policy co-ordination across levels of government are on occasion impaired by the large number of government institutions involved in SME policy and by uneven policy capacities at the local level.

The local context for SME and entrepreneurship policy

This section looks at geographical variations in wealth (GDP per capita), the business environment, business activity, and access to strategic resources (e.g. bank loans and business development services) in Indonesia. It points to strong heterogeneity in economic conditions and SME performance across provinces, which reflects the geographical expanse of Indonesia and calls for the tailoring of national policies to the local context.

Geographical variations in GDP per capita

Indonesia has a population of 261 million people distributed across roughly 1 000 inhabited islands. The distribution of the population is somewhat uneven, with over half (55%) of the population living on the island of Java which also hosts the capital city of Jakarta.

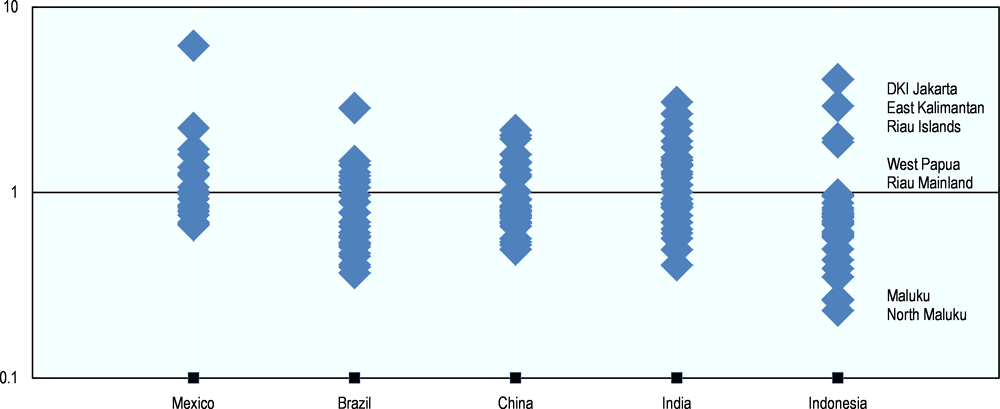

There are strong geographical variations in GDP per capita across the country. For 28 of the overall 34 provinces which comprise Indonesia, GDP per capita varies between IDR 15 million (East Nusa Tenggara) and IDR 48 million (Papua), already a significant range. However, for the top six provinces, this range is even wider, between IDR 72 million in West Papua and IDR 195 million in the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (Figure 6.1). Besides the capital-city effect – Jakarta’s GDP per capita is four times higher than the national average – natural resource endowments explain the other peaks, notably oil and gas (East Kalimantan, Riau and Riau Islands), copper and gold (Papua) and palm oil (again Riau and Riau Islands). Indonesia’s poorest provinces, on the other hand, are typically remote southern and eastern islands lacking significant natural resources (e.g. Maluku). Indonesia’s GDP per capita is also much more dispersed than in other major emerging-market economies (Figure 6.2).

Geographical variations in the business environment

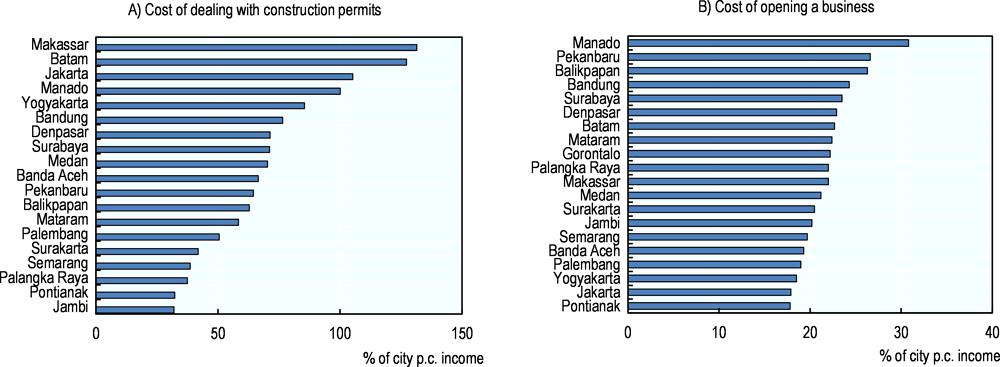

Geographical variations in the quality of the business environment have been captured by two subnational World Bank Doing Business surveys in 2010 and 2012. These two surveys benchmarked 14 Indonesian cities and found considerable differences in the burden of business regulations. For example, in 2012, the cost of dealing with construction permits ranged between 132% of annual per capita income in Makassar (South Sulawesi) and 32% in Jambi (Central Sumatra), while the cost of opening a business in relation to income per capita was nearly twice as high in Manado (North Sulawesi) as in Pontianak (Borneo): 31% compared with 18%. The number of days to open a business also changed across provinces, although there was no evident relationship with the incurred costs. At the time of the 2012 survey, for example, it took 42 days to open a business in Pontianak and 34 days in Manado (Figure 6.3).

The quality of the local business environment also includes the efficiency and effectiveness of the local public sector in delivering public services (William, Ritzen and Woolcock, 2006). The Indonesia Governance Index captures the quality of local political office, bureaucracy, civil society and economic society in Indonesia through a composite index (Gismar, Lockman and Hidayat, 2012). This index shows that the quality of local government is best in Yogyakarta and worst in North Maluku, suggesting that it is linked, among other things, to local levels of income. Such heterogeneity is also likely to have an impact on the capacity of local governments to design and implement effective SME and entrepreneurship programmes.

Aware of such heterogeneity in business regulations, the Indonesian government has launched several economic policy reforms to simplify and harmonise business regulations across provinces. For example, the 2016 XII Economic Policy Package specifically aimed to remove regulatory burdens for businesses and improve the ease of doing business. Nevertheless, the Monitoring Committee for the Implementation of Regional Autonomy (KPPOD) has found that despite these efforts there are still many overlaps in regulations which are partly the consequence of the speed at which the decentralisation process has taken place and which has left behind conflicting laws and unclear jurisdictions across different levels of governments (KPPOD, 2016).

Geographical variations in SME and entrepreneurship activity

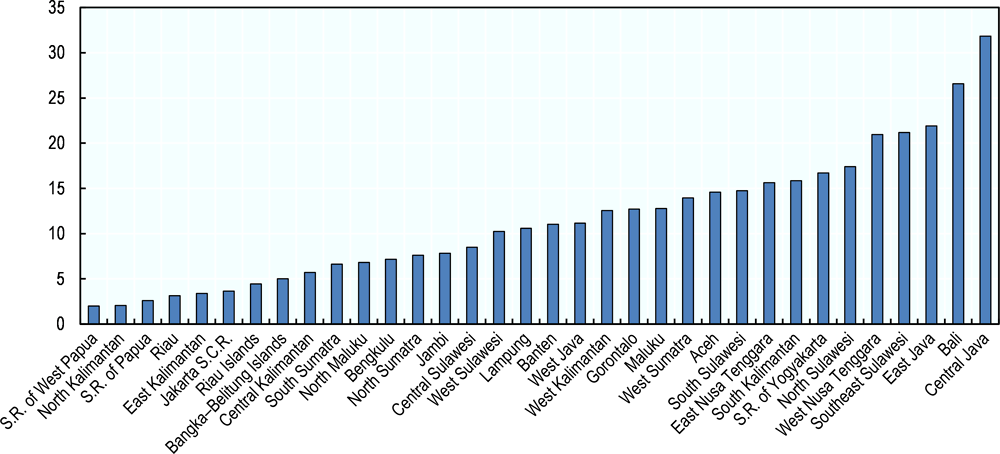

Geographical differences are also evident in SME and entrepreneurship activity. Figure 6.4, based on information from the annual Micro and Small Manufacturing Industry Survey of the Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS), shows substantial variations across Indonesian provinces with respect to industry-based small business density, which is measured as the number of industry-based businesses with 1-19 employees per 1 000 people. The densely populated areas of Central Java, Bali and East Java have the highest ratios (between 21 and 31), while the lowest ratios (2-3 businesses per 1 000 inhabitants) are found in the Special Region of West Papua, Papua, North and East Kalimantan, and Riau. Overall, 25 of the total 34 provinces had ratios below 20 small businesses per 1 000 people in 2015.

Variance in small business density can be influenced by many local factors, such as the presence of large employers, natural resource endowments (since large companies tend to dominate the exploitation of natural resources), whether the province is mostly rural or urban, and the weight of the informal sector.

Geographical variations in access to resources: loans and BDS

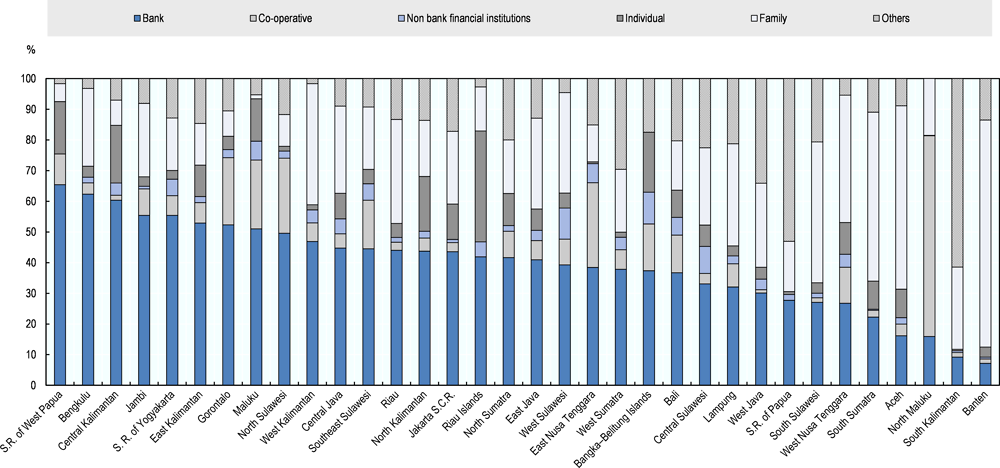

The BPS “Micro and Small Manufacturing Industry Survey” also provides insights on the access of small manufacturing companies to strategic resources, such as bank loans and business development services (BDS). The extent to which bank loans are the main source of loans ranged from 7% in Banten to 65% in the Special Region of West Papua in 2015. Family loans, and to a lesser degree, loans from individuals replaced bank loans as the main source of finance in certain specific cases, such as Banten, Aceh, South Sumatra and South Sulawesi. Loans from co-operatives were, on the other hand, mostly used in remote provinces such as North Maluku and East Nusa Tenggara (Figure 6.5).

With respect to the main reasons for small businesses not obtaining a loan, these were similar across all provinces. The most commonly reported reason was that a loan was not needed at the time of the survey, followed by procedural difficulties (notably in Java and Tenggara) and high collateral requirements (notably in Java, Bali and Sumatra). However, while the order of importance was similar, the incidence of each motive/barrier changed considerably by province. For example, “procedural difficulties” were mentioned by only 9% of small industrial companies in Bali, but by 26% in North Kalimantan and 53% in Maluku, where it was the single most important barrier to receiving a loan.

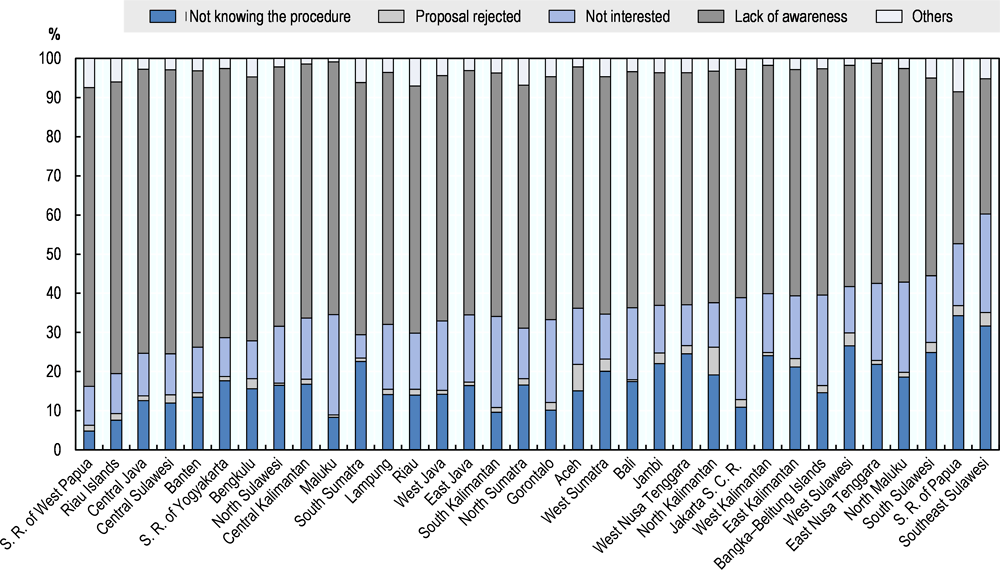

Provincial conditions also affect the take-up of BDS, which ranged between 1.5% in the eastern province of Maluku and 14% in the Special Region of Papua. Lack of awareness about BDS was the main reason across all provinces for entrepreneurs and small business owners not using them. Where lack of awareness was less pronounced, procedural difficulties were often pointed out (South Sulawesi and the Special Region of Papua) (Figure 6.6) (see chapter 7 for a more detailed analysis of BDS provision in Indonesia).

Local government responsibilities in SME policy

Transforming from a long history of centralisation, Indonesia has undertaken a programme of extensive and rapid decentralisation since 1999. Law 22/1999, which was implemented in 2001 and resulted in the so-called “Big Bang” devolution, transferred many functions to subnational governments in all but a few tasks expressly assigned to the central government (defence, justice, police and planning). Because of the decentralisation process, the regional share in total government spending quickly doubled and two-thirds of the central government workforce was transferred to the regions (Hofman and Kaiser, 2002). As of 2012, fiscal transfers from the national government constituted 82% of the revenues at the district level, 66% at the city level and 34% at the provincial level, while own source revenues were 7% at the district level, 18% at the city level and 46% at the provincial level. Decentralisation has also led to a rise in the number of governmental units at all four sub-national tiers of government: provinces, regencies and cities, districts, and villages (Table 6.1).

Following the decentralisation process, local government responsibilities in SME policy have grown to include the fulfilment of regulatory functions (e.g. business licenses and permits) and the design and implementation of support programmes (e.g. access to finance, infrastructure provision, business information and partnership, and trade promotion). One of the consequences of increased local autonomy has, therefore, been stronger variations in regulatory and licensing regimes across provinces.

In addition, a recent law on local government responsibilities (Law 23/2014) assigns the task of supporting specific enterprise sizes to different tiers of government. More specifically, this law provides that:

-

The national government is responsible for the development of co-operatives and for providing education, training, and guidance for all SMEs. Furthermore, it is responsible for the development of medium-sized enterprises through other policies beyond education, training and guidance.

-

The provincial government is responsible for the development of small enterprises (except for education, training and guidance provision).

-

The city/regency government is responsible for the development of micro-enterprises (except for education, training and guidance provision).

While Law 23/2014 makes SME policy a legal obligation for local governments, it lacks a clear rationale by limiting the possibility for local governments to have policies for enterprises of a different size to the one they are responsible for by law. As it stands, this law might cause confusion among policymakers and entrepreneurs and might generate overlaps in certain cases and leave policy gaps in others. Furthermore, there is a risk that, if fully implemented, this law could leave micro and small companies in poorer regions managed and supported by local administrations with lower financial and human resource capacities than those in richer regions, thus widening the development divide among Indonesian provinces and regencies/cities.

At the very local level (i.e. district level), SME development falls within the responsibility of the Heads of District. At this level, whether SME development is a priority and whether national and provincial programmes are properly implemented often depends on the political agenda of the Head of District and the capacity of local government staff, adding a further element of volatility to the breadth and depth of SME policies at the local level.

Although local governments have a high degree of autonomy to tailor national programmes to local circumstances, limited local resources often inhibit the development of adequate policies, especially at the city and district levels. The range of SME and entrepreneurship programmes is, therefore, narrow in some places, and policies supporting the upgrading of SMEs into higher-value added activities are relatively sporadic. Limited local resources also mean that national attempts to simplify the system of business permits and licenses can be resisted at the local level because local governments wish to protect the revenue stream generated from granting such permits.

In addition to a lack of resources, local governments may lack the capacity to properly analyse the local situation and develop and implement appropriate policy responses, especially in less developed regions. The long tradition of centralisation in Indonesia has meant that for a long time local governments did not have the necessity to build the capacity for local economic development planning and policies (Nasution, 2016), although this has partly improved after the main decentralisation reform of the early 2000s. Monitoring and evaluation activities are also uneven and often focused upon counting quantitative inputs, activities and outputs of policies rather than focusing upon outcomes and longer-term impacts.

It follows that some of the generic supply-side policies are insufficiently differentiated and tailored to the local context. Examples include a lack of appropriate local access to finance initiatives for non-trade sectors such as fisheries and forestry in areas where these are key sectors; digitalisation initiatives that are not sufficiently matched to the different stages of business development; and limited export and internationalisation promotion for SMEs at the local level, with the partial exception of major cities (see chapter 5 for more details on national programmes).

Other stakeholders have made progress in tailoring their services to local conditions. The Association of Business Development Services of Indonesia (ABDSI), for example, has focused on developing vocational training, access to seed capital, and provision of equipment in border and under-developed areas, including in primary sectors such as fisheries and forestry. Going forward, business associations and chambers of commerce could become anchor institutions to provide capacity building to local governments, as shown by the example of Germany (see Box 6.1).

Description of the approach

Several branches of the German Chambers of Commerce and Industry have developed checklists, training seminars and online support materials to help local governments to create a business-friendly environment for entrepreneurs and SMEs in their community, city, or region. The checklist includes questions on whether one-stop shops have been enacted locally, how high quality and transparency in service provision to businesses is secured, and what online services have been established. According to the local branches of the chamber of commerce, this initiative has helped raise awareness in local communities on how policy can stimulate entrepreneurship locally, including how local public officials can facilitate service provision for SMEs and entrepreneurs.

Success factors

Key success factors have been the traditionally close ties of the local chambers of commerce with city and village governments, which have helped to build a relationship of mutual trust, as well as the organisation of inter-communal seminars in which different communities were able to exchange and learn from each other on how to improve the local business climate.

Obstacles and responses

Key challenges have included difficulties in overcoming institutional rigidities such as limited flexibility in the allocation of staff and the lack of available budget to implement certain support measures. These issues were solved in a number of areas through co-operation among smaller municipalities and inclusion of practical implementation aspects in training events and seminars.

Relevance to Indonesia

One of the key issues in local entrepreneurship and SME policy formulation is a lack of capacity on how to create a business-friendly local environment and how to actively support entrepreneurship and SME development locally. The national government could consider a training academy in collaboration with the chambers of commerce to build local government knowledge on key issues related to local economic strategy building, strategic marketing and branding, and business aftercare services.

Sources for further information:

https://www.dihk.de/themenfelder/wirtschaftspolitik (in German)

Mechanisms for tailoring national SME and entrepreneurship programmes to local conditions

Two co-ordination mechanisms ensure that national SME and entrepreneurship policies are tailored to local needs. The first is a bottom-up policy co-ordination process which provides the lower levels of government with the opportunity to express their views. This consultation process has its starting point in each village through regular village council meetings and goes through district, regency/city and finally province to the central government to feed into national policy making. While this mechanism theoretically provides local governments with the possibility to feed into national policy development, it is unclear to what extent it is implemented across provinces. Moreover, as noted earlier, research and analytical capacities to identify local conditions and issues and to inform policy making is uneven across local governments.

The second co-ordination mechanism, of a more top-down nature, ensures that nationally-funded SME programmes are tailored to local circumstances through the setting of national targets that local governments are responsible for delivering. However, such targets tend to focus on the numbers of certain activities rather than on their contents and outcomes, thus reducing the scope for adaptation to local conditions.

In addition, the decentralised governance system of Indonesia has offered substantial autonomy for governments at local levels, which also supports policy tailoring. For example, the national One Village, One Product Programme focuses on targeting support for the development of a product that is unique to its local area. This programme is effective in addressing local conditions through relying on local knowledge, skills, traditions and resources. However, one possible downside is that a similar programme could end up reinforcing economic specialisations in low value-added activities at the expense of promoting upgrading of existing products or the creation of new products.

Clear policy targeting is also evident locally in programmes for specific groups such as women and youth, for sectors and key products (e.g. food, furniture, garments), and for geographical areas, such as lagging and border regions. Combinations of such targeting are also utilised where appropriate (see Box 6.2). The leadership of responsible national ministries is also visible in offering support at the local level. For example, the Ministry of Industry runs the Indonesian Footwear Development Centre, which focuses support on size standardisation, product quality and branding in footwear, and the Bali Creative Industry Centre, which develops competences in animation and ICT, crafts, and fashion.

Bank Indonesia has implemented a nationwide programme jointly with local governments to increase women’s participation in economic activities and in the formal banking system. In Papua, the identified local economic potential mostly involved handicrafts for domestic and export markets. The programme aimed to support women through education, training and individual mentoring on aspects related to business planning, marketing and technology. The programme also encouraged the formation of formal groups of women producers with the aim of enhancing their chances of receiving credit from local banks. Finally, an annual sales exhibition is organised in Jakarta that brings products for sale from all 46 areas where the programme has been operating.

Mechanisms for co-ordinating national-local SME and entrepreneurship programmes

The main policy co-ordinating mechanisms in Indonesia work in a top-down fashion. At the central level, the Ministry of National Development Planning (BAPPENAS) prepares Long-Term, Medium-Term and Annual National Development Plans, based on priorities set out at the Presidential level. These plans provide broad economic policy directions and inform the work of all technical ministries, each of which prepares a “Strategic Plan” to fulfil its mandate. Co-ordinating Ministries, notably the Co-ordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs in the case of SME policy, also play an important role in the co-ordination of the work of technical ministers (see chapter 4 for more details on the governance of national SME policy).

Local governments at province, regency/city, and district levels each have Medium-Term Development Plans that are used to adapt the national plans to local conditions. In addition, the elected governors have the possibility to introduce their own local priorities following their election. Annual co-ordination meetings are held between national and local-level stakeholders that involve national and local government and the private and civic sectors. Quarterly regional meetings are also used for information exchange, technical co-ordination and programme adjustment activities.

National technical ministries collaborate with the local level either directly or through their local representative offices. For example, the national Ministry of Co-operatives and SMEs, in the framework of the Integrated Business Services Centres (see chapter 7), has encouraged local governments to use existing buildings to provide services to SMEs and entrepreneurs so as to reduce the need for national government funding. On this occasion, local governments have also been asked to engage and lever in resources from other local stakeholders including banks, universities, and research centres.

Joint working between national ministries and local governments has also led to policy innovations in certain cases, for example on gender empowerment (see Box 6.3).

In 2016, the gender budgeting and home industry programme was piloted in a three-year Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection and the city of Cilegon in the province of Banten. Cilegon is a relatively poor area in the national context; identified local issues included high levels of migrant flows and people trafficking. The aim of the programme was, first, to provide greater gender transparency in the local government budgeting process and, second, to develop a programme to support women’s home-based business start-ups. The programme was match funded by the national Ministry and the local government on a phased basis, reducing from 100% national funding in Year 1 to 20% in Year 3 and 100% local funding in Year 4.

Identified as a longstanding issue, co-ordination between the national and local levels in Indonesia is complicated by the large number of national and subnational governmental units involved in SME policy and by uneven policy capacity at the local level (Budiharsono, 2014; OECD, 2016a). Other key problems identified by different ministries include the need for a better understanding of SME and co-operative development issues at the local level; reducing duplication and clarifying roles and responsibilities, especially for programme implementation; increasing the funding and incentives for programmes that stimulate productivity improvement; and enhancing monitoring and evaluation (see, for example, Burger et al., 2015).

Mechanisms for co-ordination among local governments and their partners in SME and entrepreneurship policy

Horizontal co-ordination – i.e. co-ordination among local governments and between local governments and other local stakeholders – is central to aligning and integrating local activities in support of SMEs and entrepreneurship. At the provincial level, the Forums of Economic and Resource Development, which include the provincial government, business associations, academics, and other service providers, are a key co-ordination mechanism (Phelps and Wijava, 2016). The forums, which are present in many provinces, bring together policy makers and key local stakeholders and also involve the regency/city and district governments.

Cluster Consultation Forums have also been utilised to engage the government with SMEs, cutting across government geographical boundaries and levels. Examples include industrial, agricultural and tourism clusters, such as footwear in Cibaduyut (Western Java) and ceramics in Plered (Special Region of Yogyakarta). Cluster forums support information and knowledge exchange and the targeting of policy support for SMEs and entrepreneurs working within the cluster.

Formal co-operation between local governments, however, has been limited by the lack of appropriate regulations to govern it (Budiharsono, 2014). Provincial governments have highlighted the lack of a legal basis for certain kinds of collaborative activities and joint projects.

Intermediary institutions are used in other national contexts to support co-ordination between local governments and other local stakeholders in the public, private and civic sectors. These institutions can be set up with the explicit objective of bringing partners together, facilitating dialogue, building capacity, and aligning policy and programme objectives, expenditure and activities. They can be jointly funded by the partners and can have a specific policy focus, as shown by the example of the Japanese Kosetsushi Centres focusing their support on innovation and technology upgrading (see Box 6.4).

Description of the approach

Japan’s local public technology centres (Kosetsushi Centres) help SMEs through technology consulting and, increasingly, by acting as a network hub for more general knowledge transfer. They focus mainly on manufacturing, food industry and design, and have inspired other similar local intermediary organisations to support SME innovation in Japan.

For example, Sasebo City in the prefecture of Nagasaki works closely with West Kyushu Techno-Consortium based at one of the technology colleges in the city. The consortium was established in 2006 to connect surrounding municipalities in the North of the Nagasaki Prefecture with other public and private actors, including the local foundation for industrial promotion, Kosetsushi Centres, industry, universities and other technical colleges in the area. The consortium aims to develop innovative technology and enhance skills for local development.

Another example is the Fukui Prefecture which established the Open Innovation Promotion Organisation in 2016. This organisation aims to facilitate and co-ordinate a programme which encourages R&D-centred collaboration among university, industry, government and financial institutions. The prefecture government responds to R&D needs of local SMEs not only through local networks and intermediaries, including the Kosetsushi Centres, but also by mobilising networks with national research institutes and large corporations beyond the local jurisdiction.

Success factors

The nature and functions of local innovation support mechanisms for SMEs have changed over the years in Japan both at prefecture and city/municipality levels. Kosetsushi Centres have existed since the late 19th century and have been funded by local authorities. They have played an important role in the Japanese innovation system through supporting local technological innovation, particularly providing consulting services for local manufacturing SMEs. In recent years, the scope of Kosetsushi Centres has shifted from only providing R&D-oriented support to a more “needs-driven” intermediary function facilitating networking and knowledge transfer among local SMEs (Nobuya and Akira, 2016). These centres are also building broader collaborative relationships with universities, sometimes connecting beyond local authority jurisdictions.

Obstacles and responses

The rise of the intangible economy has meant a growing importance of intangible assets beyond R&D. To respond to this major shift, the Kosetsushi Centres have moved from being R&D centres to hubs of knowledge transfer which work on both technological and non-technological innovation. Furthermore, job mobility of local public officers, which is common in Japan, helps co-ordination among local governments, the Kosetsushi Centres and other local stakeholders even when formal local co-ordination mechanisms are not in place.

Relevance to Indonesia

Indonesian SMEs face problems in adopting new technologies for improving productivity. While local programmes have been developed in some provinces, strong institutions and arrangements to align and co-ordinate initiatives aimed at supporting technology innovation in small enterprises are relatively sporadic. The Japanese Kosetsushi Centres, and similar other initiatives, could be a model for local government engagement with local partners from industry and universities to support SME innovation at the local level.

Sources for further information

Fukui prefecture: http://www.yuchi.pref.fukui.jp/en/fukui/1300-4m.html.

Nishi Kyushu Techno consortium: http://www.sasebo.ac.jp/~kikaku/yoran/16youran/pages/35.html.

Nobuya, F. and G. Akira (2016), Problem Solving and Intermediation by Local Public Technology Centers in Regional Innovation Systems, first report on a branch-level survey on technical consultation, http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Indonesia is characterised by large geographical variations in wealth, the quality of the business environment, SME and entrepreneurship activity and enterprise access to strategic resources (e.g. loans and business support services). A devolution process started in the early 2000s has helped provide the necessary flexibility to target policy to local needs; however, there are still challenges both with regard to the tailoring of national SME and entrepreneurship policies to the local context and to ensuring effective policy co-ordination across levels of government. Both are made difficult by the large number of national and subnational institutions involved in SME policy and by uneven policy capacity at the local level.

Furthermore, the recent law on the role of local government in SME policy (Law 23/2014) is a source of complexity by giving policy responsibility for firms of different sizes to different levels of government. This law is difficult to implement and, if fully implemented, would likely leave SMEs in poorer provinces and regencies/cities supported by subnational governments with poorer resources and capacities.

Based on this analysis the following recommendations are offered to strengthen the local dimension of SME and entrepreneurship policy in Indonesia.

-

Build capacity among local policy makers to develop local SME and entrepreneurship policies, including through information and awareness raising, training and guidance material, and mentoring and peer learning networks between stronger and weaker local governments.

-

Encourage local-level reviews of the range of SME programmes in place to ensure an appropriate policy mix, which should also include programmes aimed at upgrading SME productivity through the use of new technologies, workforce training and/or managerial skills upgrading.

-

Match quantity with quality targets for SME and entrepreneurship policy outcomes at the local level. This will require changing targets from focusing solely on the total numbers of SMEs and entrepreneurs created and/or sustained to a wider focus on their quality in relation to indicators such as value added, wage levels and employment.

-

Consider amending Law 23/2014 where it assigns responsibility for the development of specific business size classes to specific levels of government (micro-enterprises to regencies or cities, small enterprises to provinces, and medium-sized enterprises to the national level) since this is a source of complexity and risks widening the development divide between more and less prosperous regions.

-

Further streamline business regulation procedures and limit the negative impact of administrative fragmentation caused by the increase in the number of local government units.

-

Develop and enhance mechanisms to improve co-ordination between government institutions at national and local levels, and among local governments, through more regular co-ordination meetings and policy dialogue on SME and entrepreneurship policies.

-

Strengthen policy monitoring and evaluation systems and better align national and local-level monitoring and evaluation approaches and activities.

References

Brunori, D. (2003), Local Tax Policy: A Federalist Perspective, Urban Institute Press, Washington DC.

Budiharsono, S. (2014), Local Economic Development: The Indonesia Experience, https://de.slideshare.net/budiharsonos/local-economic-development-the-indonesian-experiences.

Burger, N., C. Chazali, A. Gaduh, A. Rothenberg, I. Tjandraningsih and S. Weilant (2015), Reforming Policies for Small and Medium Enterprises in Indonesia, RAND Corporation and Tim Nasional Percepatan Penanggulangan Kemiskinan (TNP2K), Jakarta, Indonesia.

Gismar, A., I. Lockman and L. Hidayat (2012), Towards A Well-Informed Society and Responsive Government , Executive Report Indonesia Governance Index 2012, The Partnership For Governance Reform, Kemitraan Bagi Pembaruan Tata Pemerintahan), http://www.kemitraan.or.id/igi/index.php/data/publication/factsheet/275-igi-executive-report.

Hofman, B. and K. Kaiser (2002), “The Making of the Big Bang and its Aftermath: A Political Economy Perspective”, paper presented at the conference “Can Decentralization Help Rebuild Indonesia?”, Atlanta, 1-3 May 2002, http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/decentralization/March2004Course/Hofman2.pdf.

KPPOD (Monitoring Committee for the Implementation of Regional Autonomy) (2016), Evaluation of the Implementation of the Economic Policy Package on Regulatory Reform across Indonesian Regions, (in Indonesian), KPPOD Publishing, Jakarta, https://www.kppod.org/backend/files/laporan_penelitian/eodb-reformasi-kemudahan-berusaha.pdf.

Nasution, A. (2016), “Government decentralization program in Indonesia”, ADBI Working Paper 601, Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/201116/adbi-wp601.pdf.

Nobuya, F. and G. Akira (2016), Problem Solving and Intermediation by Local Public Technology Centers in Regional Innovation Systems, first report on a branch-level survey on technical consultation, http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/.

OECD (2016a), OECD Economic Surveys: Indonesia 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-idn-2016-en.

OECD (2016b), Open Government in Indonesia, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265905-en.

Phelps, N. and H. Wijaya (2016), “Joint action in action? Local economic development forums and industry cluster development in Central Java, Indonesia”, International Development Planning Review, Vol. 38, N. 4, pp. 425-448, https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2016.24.

Strickland, T. (2016), “Funding and financing urban infrastructure: a UK-US comparison”, Newcastle University, Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation, https://theses.ncl.ac.uk/dspace/bitstream/10443/3148/1/Strickland%2C%20T.%202016.pdf.

William, E., J. Ritzen and M. Woolcock (2006), “Social cohesion, institutions, and growth”, Economics and Politics, Vol. 18, N. 2, pp. 103-120, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2006.00165.x.

World Bank (2012), Doing business in Indonesia 2012, World Bank, Washington DC, http://www.doingbusiness.org/~/media/WBG/DoingBusiness/Documents/Subnational-Reports/DB12-Indonesia.p.