Chapter 1. Migration Snap-shot of the city of Paris

1.1. Migration insights: National and local level flows, stock and legal framework

Official statistical data on the presence of migrants use three categories: immigrants, foreign nationals and native-born individuals with at least one parent who is a migrant. According to the most recent INSEE data, immigrant (i.e. individuals born foreign in a foreign country who might have obtained French nationality) represented on January 2014, 8.9% of the population in France (Brutel, 2016; OECD, 2017b). While there has been evolution in the countries of origin in the past 45 years, the main countries remain Italy, Spain, Portugal, Algeria and Morocco. France has a long history of international migration and the presence of migrants today results from several migration inflows from the 20th century. Between the two world wars, workers from Spain and Italy arrived in the country responding to the needs of the expanding industrial and agricultural sectors. After 1945, the reconstruction efforts particularly important in the most populated urban areas, called for workers from colonial Algeria, first, and other Maghreb areas after. They were followed from the 1960s by Portuguese and sub-Saharan Africa nationals, and by the end of the century arrivals of Asian migrants coming mainly from Turkey and China (Brutel, 2016). In 1968, there was a strong concentration of economic activity in the Île-de France region which accounted for, at that time, 40% of the industrial work and 30% of the French population. Consistently, 50% of immigrants settled in Île-de France. Yet, while industrial labour has been declining since the 1970s, especially in these areas, the immigrant population is still highly concentrated in these zones (Brutel, 2016).

Foreign-born represented in 2017 12.3% of France population. The rate of foreign-born over total population is lower in France compared to the OECD average (13.1%) and to other EU peers: in Germany foreign-born represent 15.4% of the population, in Belgium 16.7, in Austria 18.9% and in Switzerland 29.5% (OECD, 2018[1]).

While the population of foreign residents is smaller than in other European countries and France is close to the EU-27 average in terms of migrant population, the role of France as receiver of migrants throughout the 20th century means that France has a large second-generation migrant population, which is tracked by the INSEE through the “descendants of migrants” category (descendants d’immigrés). In 2008, France was the EU-27 country with the highest percentage of descendants of migrants (Bouvier, 2012). In 2015, 7.3 million people (11% of the population) born in France had at least one immigrant parent. Among them, 45% are of European origin, 31% from the Maghreb (i.e. Northern African), 11% Sub-Saharan Africa, 9% Asia, 4% America and Oceania (Brutel, 2017). Descendants of migrants are not as geographically clustered as immigrants: 30% of descendants of migrants live in the urban area of Paris (Brutel, 2017).

1.1.1. The urban area of Paris as a migration hub

The distribution of migrants across the territory is highly concentrated. According to the INSEE, 90% of migrants having arrived in the country in the past five years live in large urban areas (Brutel, 2016). The geographic localisation of recently arrived migrants follows the existing distribution, as areas which received the first migration inflows remained the main destinations for incoming migration arrivals (Noiriel, 2002; Safi, 2009). According to the national statistics institute (INSEE), the concentration of migrants is higher than the one of non-migrants: while nine out of ten migrants live in urban areas spaces, this is the case for eight out of ten non-migrants (Safi, 2009; Diaz-Ramirez, Liebig, Thoreau and Veneri, 2018).

The city of Paris has a long history of attracting foreigners. As a European hub, Paris has the most diverse population in France with more than 150 nationalities represented in the city. According to INSEE data, while the Île-de-France region hosts around 20% of the total population in France, 40% of migrants present in mainland France reside in this region. A third of migrants arrived in the past five years live in Île-de-France. (Brutel, 2016; OECD, 2017b).

15% of Paris population has a foreign nationality and 20% is foreign born (among which more than a third have acquired French nationality). The most common nationalities are Algeria, China, Portugal, Morocco and Italy.

1.1.2. Migration legislative framework

According to French legislation1, non EU-foreign residents are required to obtain a residence permit: either (1) the temporary residence permit (Carte de séjour temporaire) which is the first residence permit that a foreigner receives and lasts for a year , (2) the pluri-annual residence card (Carte de séjour pluriannuelle) for a maximum length of four years addressed to foreigners who have already been admitted in France and only delivered after a first residence permit, (3) the resident card which is valid for 10 years and renewable, (4) the permanent resident card which is the completion of the integration path and allows the foreigner to live and work in France without renewing a residence permit. There are long delays to obtain administrative appointments for the residence permit which leads to repetitive deliverance of “récépissés”, temporarily substituting for the residence permits (Vandendriessche, 2012). For a complete presentation of the OECD’s work on recent legislative changes in France, refer to « Le recrutement des travailleurs immigrés en France » (OECD, 2017b).

1.1.3. Recent inflows of asylum seekers and refugees

Like in many other European contexts, the number of asylum seekers and refugees has sharply increased since 2015. In 2015, the number of first-time asylum applications climbed sharply with a 25.5% surge, to 75 000 applications. The growth continued in 2016, reaching the highest peak in French history with 79 000 first-time applications (OECD, 2017a). Most asylum seekers were from Sudan, Afghanistan, Haiti, Albania, Syria, Democratic Republic of Congo and Guinea (OECD, 2017a). France granted international protection to around 43 000 people in 2017 through refugee or subsidiary protection status. Overall, the OFPRA accepts 29% of first instance requests, a figure which climbs up to 38% when including successful appeals before the National Court of Asylum Rights.

1.1.4. Asylum legislative framework

French asylum legislation has evolved since 2014 and further details are given in Annex C.

A 2015 reform granted new rights to asylum seekers (e.g. automatically suspends decisions after appeals have been heard by the National Court of Asylum CNDA) and sped up the process of application with a target to process asylum applications on average of nine months by the end of 2016. Yet according to numbers provided by the Ministry of Interior, in 2016 the procedure lasted 14 months. In February 2018, a new Asylum bill was proposed by the national government engaged in reducing the asylum registration process, instruction and judgment phases. It aims to reduce to six months the length of instruction of asylum demands (appeal included), which would especially concern Île-de-France where the concentration of asylum seekers makes the procedure longer. It also aims to reduce from 120 to 90 days the registration time once the migrant has entered France, and the time available for appealing a rejection (from a month to 15 days)2. This law was being debated at the time of publication; therefore, its final characteristics cannot be presented here.

1.1.5. Distribution of asylum seekers and refugees in France

Over the past two years, Paris has experienced an increase in the arrivals of humanitarian migrants like many other urban centres in Europe. Île-de-France receives around 40% of spontaneous arrival inflows of asylum seekers in the national territory. Out of the 63 649 asylum requests made in 2016 in France, 24 020 were submitted in the region of Île-de-France, including almost half of them in the city of Paris (10 151) (OFPRA, 2017).

Preliminary observations on the location of asylum seekers gathered by the OECD in 2017 identify that the number of asylum seekers hosted in accommodation facilities by the national government is higher in the regions of Grand-Est and Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes than in Île-de-France, illustrating the efforts of the government to spread reception pressure from the capital region to other parts of the country (see 4.1.4) (Proietti and Veneri, 2017).

At the regional level, Île-de-France is the biggest third region in terms of the number of hosted asylum seekers in the accommodation system, from preliminary observations gathered in 2017 (Proietti and Veneri, 2017).

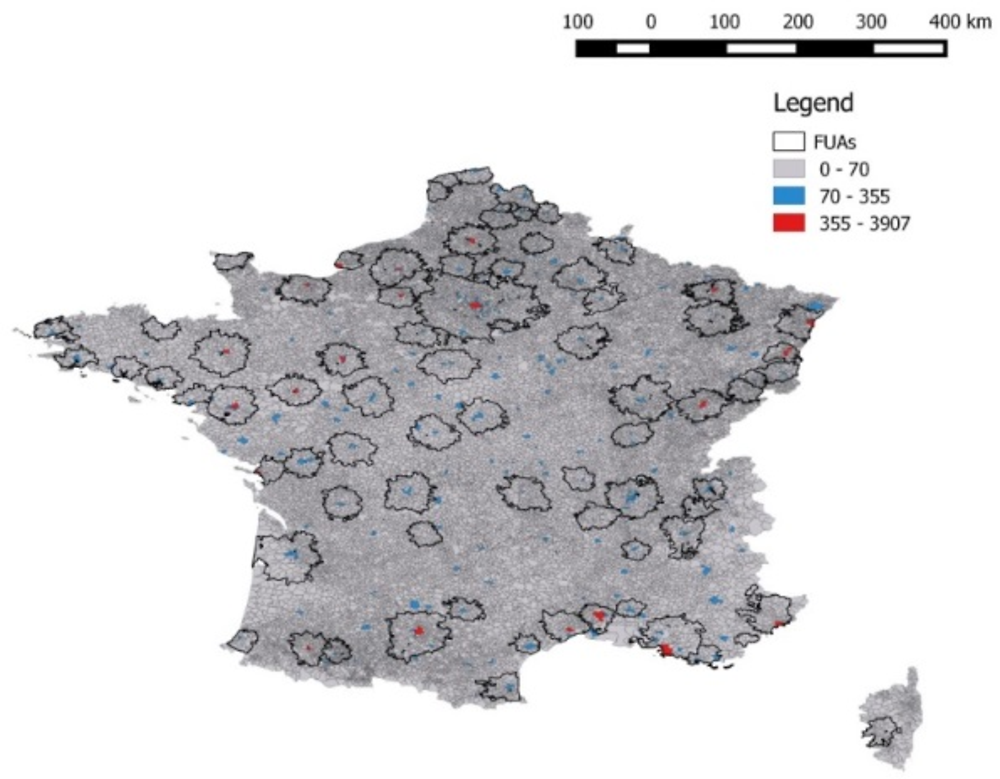

In France, there is a relatively high concentration of asylum seekers in urban areas (See Figure 1). While the number of municipalities in France is the highest across the OECD (above 36 000), only a small percentage of the municipalities (less than 5%) were hosting asylum seekers at the beginning of 2017. In the city of Paris, there were 3 907 asylum seekers hosted in accommodation centres in 2017 (AT-SA; CADA; HUDA) (see Section 2.1.4).

Migrants accounted for 76% of the total homeless population in Paris in 2015 (APUR, 2017a). In July 2017, 2 700 migrants lived in the streets of Paris. Since 2015, the media has reported the presence of newly arrived persons who gather in Parisian street camps in specific neighbourhoods such as La Chapelle, La Villette and Boulevard Stalingrad. Most irregular migrant street camps are located in the Northeast area of the city, the areas which has historically had a higher share of migrants. Since 2017, following the 2016 evacuation of the Calais camp, several NGOs have highlighted further increases in the presence of homeless migrants in Paris. As of March 2018, the asylum-related NGO France Terre d’Asile which undertakes maraudes3 to identify and support homeless migrants, has counted 1 885 migrants living in street camps made of tents (400 in Canal Saint Martin and 1 400 in Quai du Lot and Quai de l’Allier in the northern border between Paris and the neighbouring city of Saint Denis) (Baumard, 2018)4. Some of them fall within the Dublin protocol and thus cannot directly access the French asylum procedure. Some cannot access shelter facilities because of lack of capacity. Following the government strategy, the Police Prefecture is in charge of sheltering those migrants who are “a priori” asylum seekers. In the first semester of 2017, the Paris prefecture (information collected by the OECD during field interviews) had conducted 70 evacuation operations and transferred future asylum seekers from the spontaneous camps to emergency humanitarian centres (100 CHU present in Île-de France). Once filed their asylum request, asylum seekers would be transferred to a reception centre (CADA) during the application procedure (see more details in Section 2.1.4). Some NGOs reported that this method does not eliminate the formation of other camps.

1.2. City Well-being and inclusion

The following section will introduce some integration outcomes while describing the residential and economic characteristics of the city.

The OECD measure of well-being in regions (TL2 level) shows that income inequalities across French regions are larger than in Germany but smaller than in the United Kingdom: households’ adjusted disposable income is 40% higher in Île-de-France than in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. (OECD, 2016b).

In the region of Île-de-France (TL2), in which Paris is situated, well-being is quite different from the average well-being. Île-de-France is performing better in the accessibility to services, health, jobs and income. Instead, Île-de-France is a slightly worse performer in education, safety, life satisfaction and sense of community and among the worse in civic engagement, housing and environment (ad-hoc analysis based on OECD well-being dataset 2017).

1.2.1. A dynamic European hub with a strong economy

Paris is the economic and political capital of France, and the most populous city: 2 220 445 inhabitants. The Parisian region (Île-de-France) comprises 12 million people. According to Paris region data, it has the highest GDP in the European Union in terms of value generation, accounting for 30.3% of France’s GDP, and 4.5% of the EU’s GDP (Paris Region, 2018).

Paris is an attractive city with the highest employment rate in France. The Parisian territory is a dense and dynamic economic fabric that is able to create employment in leading recruiting sectors. Paris fared better during the economic crisis than the overall national territory and its employment area has a considerable potential with 34 000 jobs (Mairie de Paris, 2015a). Paris is an attractive territory for companies. 600 companies are created every week and there are more than 367 322 active companies (Mairie de Paris, 2015a)

White collar, executive and senior intellectual jobs are increasing. The city hosts the French and/or European headquarters of several international corporations. It is also an academic and research and development centre with several institutions of higher learning that attract a diverse student body from Europe and other countries. The economic attractiveness of the city was reinforced when the world’s biggest start-up campus - Station F - was inaugurated in 2017 (https://stationf.co/). Further, Paris is the world’s most popular tourist destination.

Paris is globally attractive and competitive but these economic transformations led to an increasing dual structure in which low skilled immigrant and foreign residents cannot access the increasingly knowledge intensive labour market and high added value employment opportunities (Lelévrier et al., 2017).

1.2.2. Segregation patterns in the city

Socioeconomic disparities and spatial segregation are sharp in Paris. Recent OECD research has shown that the French capital has one of the highest income inequalities relative to its population, on par with cities such as San Francisco (OECD, Making cities work for all, 2016; OECD, Divided cities, 2018). The metropolitan area of Greater Paris has the highest income inequalities among French metropolises (APUR, 2017b). Within the metropolitan area, it is in the city of Paris where income inequalities are wider: after redistribution the income of the more affluent households is 6.6 times higher than the income of the poorest households (APUR, 2017b).

Unemployment rates vary across the districts of Paris. The highest share of unemployed and economically-deprived individuals is concentrated in neighbourhoods in the east and north and some clusters in the southern districts. In contrast, there is a considerably low unemployment rate in the affluent central and western districts and in most parts of the city’s south. Intermediate districts, north of the river Seine, bridge between these contrasting areas (UCL INEQ-CITIES Atlas, 2017).

Similarly, beneficiaries of the government’s minimum allowances are concentrated in the same north eastern districts. The 18th, 19th and 20th arrondissements account for 38% of Paris’ welfare beneficiaries yet they account for only 26% of the active population of the city (Mairie de Paris, 2015a based on INSEE RP 2012). Social housing distribution across the city of Paris is highly uneven. Today, social housing is concentrated in three districts: almost 50% of the total social housing stock is in two -northeast arrondissements (19th and 20th) and a southern district (13th) (APUR, 2017c).

In the city of Paris there are twenty Priority districts targeted by the national government through the City Policy (see box 2.2), located mainly in the east and north (13th, 18th, 19th and 20th arrondissements but also in the 10th, 11th 14th and 17th). The choice of the neighbourhoods is based on the single criterion of poverty concentration. These districts reflect high levels of economic deprivation, 26% of residents in area targeted by the city policy live below the low-income threshold, versus the Paris average of 11% (APUR, 2016a).

Migrants are concentrated in the outer districts and neighbouring municipalities of Greater Paris. Since 1968, the concentration of the immigrant population within Île-de-France and particularly Paris’ urban area has increased (Safi, 2009). According to 2007, INSEE data, the spatial concentration of migrants in Paris has been accelerating with the share of migrants rising in the areas where migrant presence was already the strongest in 1999. Other factors influencing the choice of the neighbourhood are the lower housing costs and the higher availability of social housing. INSEE data shows that the migrant population is more present in the Northeast Parisian Arrondissements (e.g. 18th, 19th, 20th) and neighbouring municipalities (i.e. Saint-Denis, La Courneuve, Gennevilliers, Bobigny). In fact, Eric Lejoindre, Mayor of the 18th Arrondissement, an area in which migration has a great impact, invited at an OECD event in April 2018 stated that his district is and has historically been a “land of welcome”. In Parisian City Policy districts (see Figure 1.5), 30% of residents are foreign, while on average migrants represent 20% of the city population (APUR, 2016a). Concentration per nationality differs: African migrants’ concentration (Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa) has increased whereas Spanish and Italian immigrant tended to disperse (Safi 2009 based on INSEE population census).

1.2.3. Public opinion and perception of migrants

The increasing arrivals of vulnerable migrants to the city in 2015 triggered a large solidarity wave from the Parisian society. However, the Parisian and French population remains divided with regard to migrants. A 2016 IFOP study illustrates, that the Parisian and French population tends to be sceptical of migrants and especially asylum applicants. Only 33% of Parisian interviewees (national average 27%) believe migrants arriving in France have an economic or financial potential and 59% of Parisians (national average 61%) believe that there is an overall lack of capacity in France to welcome additional new arrivals (IFOP, 2016). Migrants remain a dividing issue within the French society at large, with an August 2016 IPSOS survey indicating that 57% of French respondents think that there are too many immigrants in the country, and only 11% deem migration to have a positive impact on the country (IPSOS, 2016). Furthermore, research conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2016 across the EU showed that only 26% of French people think that diversity makes their country a better place to live, and highlights scepticism amongst a wide share of the population that migrants can truly integrate (Pew Research Centre, 2016).

Notes

← 1. Code de l’entrée et du séjour des étrangers et du droit d’asile.

← 2. Further information about asylum legislation can be found at: https://es.scribd.com/document/368911950/Presentation-des-dispositions-du-projet-de-loi-asile-immigration#from_embed

← 3. “Maraudes” are undertaken by NGOs on a regular basis. They are walks throughout Paris to identify and count vulnerable residents in the streets and provide them with social support.

← 4. Updated information on the evolution of street camps in Paris can be found in: http://www.lemonde.fr/journaliste/maryline-baumard/