Chapter 15. Lao PDR

Lao PDR has focused its SME policy on improving the legal and regulatory environment to support SME development. It has been developing targeted SME policies since the early 2000s and benefits from a relatively good institutional framework and a dedicated fund for SME development. It is increasingly interested in policies to enhance SME productivity and integration into GVCs, but these areas currently lack sufficient funding.

Overview

Economic structure and development priorities

Economic structure

Lao PDR is a lower middle-income country located at the heart of the Greater Mekong Subregion. It has the lowest population density in ASEAN, with a population of 6.6 million spread over 236 800 km2 (ASEC, 2016[1]). It is richly endowed with natural resources such as copper, gold, tin, gypsum, gemstones and timber, and these resources, particular copper, remain the primary driver of GDP and exports.1 The economy remains highly agrarian, with 60.3% of the population living in rural areas2 (World Bank, 2016a[2]) and agriculture accounting for around 71.4% of employment in 2016 (ILO, 2016[3]) and 24.8% of value added in 2014 (World Bank, 2016a[2]) (last available data). Since the early 1990s, Lao PDR has prioritised the development of an additional resource, electricity, through substantial investment in hydropower facilities, making use of its vast river network and access to the Mekong River Basin as well as its sparsely populated territory. Electricity now accounts for around 30% of exports recorded by customs (IHA, 2016[4]), and its hydropower is an important energy source for neighbouring Thailand, China and Viet Nam.

Lao PDR is currently one of the fastest growing countries in the world, sustaining a GDP growth rate above 5% almost every year since 1992.3 However, much of this growth has been driven by booming copper prices and foreign direct investment (FDI) in hydropower and mining activities.4 FDI inflows peaked in 2015 at USD 1.1 billion. To build up its industrial base, the government has prioritised the attraction of FDI and the development of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) since the early 2000s. Yet currently only two SEZs appear to be active,5 and investments remains concentrated in low value-added activities outsourced from neighbouring countries. As a landlocked country with significant infrastructure gaps, Lao PDR is heavily dependent on its neighbours for trade, with China, Thailand and Viet Nam accounting for almost 90% of total trade in 2016 (MIT, 2016[5]). Yet it benefits from a young and active population, and this could be leveraged for future growth: around 53.9% of the population are aged 24 or under (World Bank, 2016a[2]), and in 2010 (latest available data) only 5.1% of young people were not in employment, education or training (NEET) (ILO, 2016[3]).

Sustained growth over the long term is threatened by rather weak public finances, a persistent current account deficit and very high external debt. Lao PDR has run a negative government balance since at least 2000 and a negative current account balance every year since at least 1980, save the year 2000 (IMF, 2017[6]). Tax collection remains relatively weak, with taxes on income, profits and capital gains contributing a very low share of total tax revenue (9.4%). The recent slump in copper prices has exacerbated the budget deficit. There is also strong domestic demand for foreign-sourced consumer goods, with automobiles constituting one of the biggest merchandise imports (8.4%) in 2016 (MIT, 2016[5]).6 Downside risks include slower external demand from China, Thailand and Viet Nam, which absorb the majority of Laotian exports,7 and adverse weather conditions, with agriculture accounting for one-sixth of the total economy (IMF, 2018[7]).

Going forward, the government could continue its efforts to establish a broader base for growth. Lao PDR has an emerging eco-tourism industry, which currently accounts for around 85% of service exports and is becoming an important source of foreign receipts. SME development could also help: large enterprises are more likely to source externally (especially from Thailand), and therefore more competitive SMEs, including as input suppliers, could help tackle the current account deficit while providing new sources of growth.

Reform priorities

The Lao PDR government’s current economic development priorities were elaborated or revised by the National Assembly on 22 April 2016. This included two long-term plans: a 15-year strategy, known as Vision 2030, and a 10-year strategy, known as the National Strategy on Socio-Economic Development 2025 (2015-2025). The main objective of NSSD 2025 is to double per capita gross national income (GNI) by 2020, while the main objective of Vision 2030 is to quadruple per capita GNI by 2030. The ultimate goals of Vision 2030 are for Lao PDR to become an industrialised middle-income country with sound infrastructure; to enhance living standards, human development and social security provisions for its people; to reduce rural-urban income disparities and ensure a sustainable use of resources and conservation; and to have competitive enterprises that are integrated into regional and global production networks. NSSD 2025 proposes long-term strategies that support the objectives of Vision 2030.

Lao PDR’s mid-term economic development priorities are outlined under the 8th National Socio-economic Development Plan (NSEDP), which covers the period 2016 to 2020. The main objective of this plan is to move Lao PDR out of the least-developed-country category by 2020.8 In addition, it aims to reduce the poverty rate by around half,9 to achieve sustainable human development and to ensure the sustainable use of natural resources. To achieve these objectives, it aims to achieve real GDP growth of not less than 7.5% per annum on average over the five year period. It envisions doing this by building up Lao PDR’s industrial base (so that industry accounts for at least 32% of GDP and agriculture not more than 19%); reducing its external debt and moderating inflation; reducing regional disparities through a careful consideration of economic geography in planning economic development policies; enhancing education and skills (particularly in technical subjects and entrepreneurial competencies); and increasing the volume and results of official development assistance via enhanced co-operation. As a landlocked country, increased engagement with regional and international partners is a priority theme of the plan.

Private sector development and enterprise structure

Business environment trends

Despite an impressive economic growth rate over the past 25 years, private sector activity in Lao PDR continues to be hampered by relatively low education levels among the local workforce, cumbersome tax rates and regulations, a high cost of credit, limited infrastructure and rather high barriers to starting a business (WEF, 2017[8]; World Bank, 2017[9]). These conditions, coupled with a “deals-based” approach to business activity and the enforcement of regulations (World Bank, 2017[9]),10 may discourage productive enterprise outside the primary resource sector, particularly for SMEs.

Medium-sized enterprises cite limited transportation infrastructure as a key constraint to doing business, while small enterprises cite tax rates (World Bank, 2016b[10]). The government has enacted reforms since the 2104 ASPI assessment in order to improve the business environment for domestic and foreign firms. These include changes to the country’s tax regime, such as revision of excise taxes, better administration of value-added tax, improved methods of valuing imported vehicles for the purpose of calculating import taxes and the elimination of tax exemptions for oil imports in public projects (IMF, 2017[11]). Lao PDR also has a preferential tax regime in place for SMEs that aims to reduce the administrative burden of filing taxes: enterprises with an annual revenue of less than LAK 12 million (Lao kip), which are exempt from value-added tax (VAT) payment, are not charged profit tax but instead must pay a lump-sum progressive tax rate of 3% to 7%, depending on revenue and the nature of their activity.

SME sector

A total of 178 557 registered enterprises were operating in Lao PDR as of 2013, of which around 75%, or 134 577, participated in the country’s 2013 Economic Census. According to the census, around 99.8% of the participating units, or 124 567, were classified as SMEs. The majority of these were micro enterprises, with those employing five workers or less accounting for 86% of all enterprises. This, alongside data from other surveys (GIZ, 2014[12]), suggests that there may be a “missing middle” in the country’s production structure, in common with many other emerging economies in Southeast Asia and beyond.11 A missing middle may indicate that SMEs face significant barriers to expansion, and this could be compounded by the fact that Laotian enterprises have access only to a small domestic market for goods and services. Surveys suggest that very few private Laotian enterprises export (GIZ, 2014[12]).

Laotian SMEs provide a slightly higher structural contribution to employment than in OECD countries, accounting for around 82.2% of total private-sector employment, according to the 2013 census (LSB, 2013[13]). Data is not collected on contribution to GDP or value added.

Geographically, SMEs appear to be concentrated in the country’s three most populous regions – Vientiane prefecture (which accounts for 12.9% of the population and 28.2% of MSMEs), Savannakhet province (15.2% of the population and 11.0% of MSMEs), and Champasak province (9.1% of the population and 9.2% of MSMEs) – with a significant skew towards the capital (LSB, 2013[13]). Small and micro enterprises tend to be concentrated in wholesale and retail trade (46.0% of small enterprises and 69.4% of micro enterprises), followed by manufacturing activities (19.4% and 11.2%) and accommodation and food services (17.5% and 11.2%). Medium-sized enterprises are most present in the same three activities, but are most highly concentrated in manufacturing (28.2%). Medium-sized enterprises also account for the highest number of establishments in mining and quarrying activities (43%) and electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply (47.1%), while large enterprises account for 4.7% and 11.0% of total establishments respectively in these sectors.

SME policy

Between 1975 and 1985, the government of Lao PDR adopted principles of central planning with the aim of achieving rapid socio-economic development. During this time, the country nationalised all industry and foreign trade and began the collectivisation of agriculture, with commercial activity by individual persons and private enterprises banned until 1979. This started to change following the introduction of the New Economic Mechanism in 1986, which began to move Lao PDR towards readopting the principles of a market economy. Reforms were begun in three areas: i) macroeconomic stabilisation; ii) price and market liberalisation; and iii) restructuring and privatisation of state-owned enterprises. In 1994, the Enterprise Law provided a legal foundation for private enterprise, including SMEs.

A push for SME development in particular occurred in 2004 with the Decree on the Promotion and Development of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises No. 42/PM. The SME Promotion and Development Committee (SMEPDC) and the SME Promotion and Development Office (SMEPDO) were created at the same time. The first dedicated SME development strategy12 was elaborated in 2006, and a project on private-sector development, with a focus on SMEs, was begun with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2007.

Many of Lao PDR’s institutions and policies for SMEs have their roots in this project, which ran from 2007 to 2009, and particularly in its successor project, the Second Private Sector and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Development Programme (PSSEDP), which was implemented between 2009 and 2011. Under the first PSSEDP, a monitoring and evaluations unit was established within SMEPDO to assess implementation of its strategy, and monitoring reports were developed. Under the second PSSEDP, the country’s Law on the Promotion of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SME Law) was developed and approved (2011), and efforts were made to streamline regulations and to socialise the use good regulatory practices among policy makers. Sub-programme 1 of the second PSSEDP (the general component, under which most of these activities took place) was attached with an ADB grant of USD 10 million and a loan of USD 5 million.

Since completion of these projects, the government of Lao PDR has increased its ownership of SME policy, which is increasingly becoming a priority for policy makers. Implementation of the strategy is partially funded through the central government budget. Development assistance agencies are still active in this area, of which the most dominant are perhaps the ADB, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the World Bank. Aside from horizontal activities, GIZ focuses its interventions on two priority sectors – coffee and tourism – where it believes Laotian SMEs could develop a comparative advantage.

2018 ASPI results

Strengthening the institutional, regulatory and operational environment (Dimensions 5 and 6)

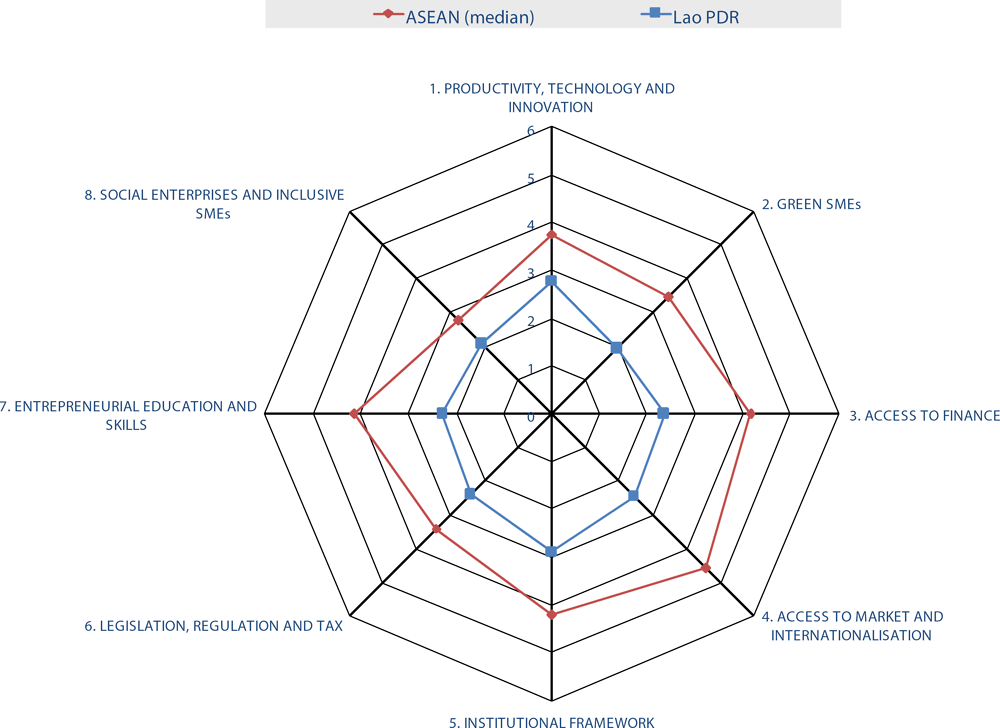

SME policies are at a relatively early stage in Lao PDR due to the fact that this has only recently become a policy priority for the national government. Yet the country has benefitted from and successfully co-operated with development assistance agencies13 in this area since 2007, resulting in a more active and better structured SME policy than in the other CLM countries. The same holds true for measures to simplify the operational environment for SMEs, although substantial efforts will still be required in the areas of e-governance, company registration and filing tax. Lao PDR’s scores of 2.89 for institutional framework and 2.40 for legislation, regulation and tax reflect these findings.

Framework for strategic planning, design and coordination of SME policy

The body responsible for formulating SME policy in Lao PDR is the Department of SME Promotion (DOSMEP), under the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (MIC). It succeeded SMEPDC, which had been established in 2004 and was chaired by the Minister of Industry and Commerce and comprised 26 members including 15 representatives of the private sector and 10 representatives of government institutions at vice minister or equivalent level. SMEPDC was responsible for overall co-ordination and formulation of SME development policies, as well as overall co-ordination of development partner assistance and high-level stakeholder consultation. This committee was disbanded in 2011 following enactment of the SME Law, and its responsibilities were transferred to DOSMEP in a push to increase government ownership of the policy.

DOSMEP is responsible for drafting the country’s SME strategy, co-ordinating with line ministries and reporting to the Central Committee. It employs 36 staff but does not yet have local offices in place. SME development policies are supported by the SME Promotion and Development Fund, which was set up in 2011 under the SME Law. This fund receives income from the national budget, international grants or loans, voluntary contributions and service fees. In 2017, the fund amounted to around USD 4 million.

Since 2006, SMEPDC and then DOSMEP have developed a mid-term (five-year) strategy for SME development. The current strategy, the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Plan, runs from 2016-2020. Its main objectives are to promote productivity and innovation, access to finance, business development services, access to markets, entrepreneurship, a favourable business environment and reducing custom and tax costs. These objectives echo the previous five-year strategy’s objectives, save the last, which is new. It was developed in consultation with stakeholders including the private sector and government ministries. The strategy was developed in reference to the goals of the five-year Industry and Commerce Sector Development Plan (2016-2020), the 8th National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2016-2020) and the ASEAN Strategic Action Plan for SME Development (2016-2025), as well as the country’s commitments under the Sustainable Development Goals. It contains concrete targets in each policy area covered. A budget of LAK 569 billion was assigned for implementation of the 2016 Small and Medium Enterprises Development Plan. Of this, 16.9% was projected to come from domestic sources (the government budget and the private sector) and 83.2% from development assistance agencies. The SME Development Plan was endorsed by a Prime Ministerial Decree on 18 January 2017.

An SME monitoring unit within DOSMEP specifies performance targets and monitors implementation of the strategy, although it faces capacity constraints. SME data are in principle collected every five years via an economic census, and every two years via an enterprise survey conducted by GIZ. The economic census is carried out by the Lao PDR Statistics Bureau, which employs a mixed approach due to capacity constraints (particularly budgetary) and a high rate of enterprise informality. Data on large enterprises are collected via a census, and a sample of informal enterprises is studied via a household survey. Data collected in the economic census therefore may not be fully representative, and the data from the last census (2013) are not yet available to the public. Data are not collected on SME contribution to GDP or value added.

Scope of SME policy

A legal SME definition was developed in 2011 under the SME Law. It disaggregates micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, and includes indicators of both value and employment to determine firm size. However, it applies different thresholds by sector, as well as two indicators of value (turnover and assets), which may reduce its ease of use. It is only necessary to use one of these indicators to classify firm size, and therefore the definition may not be used consistently through different government agencies, despite being gazetted in law. Its upper threshold in the employment criterion is also rather low (an upper threshold of 200 employees is typical across the OECD), but this is common in many smaller economies.

High informality rates may exclude a large number of SMEs from policy interventions. Data from international sources on informality in Lao PDR are scarce, but DOSMEP’s 2016 Small and Medium Enterprises Development Plan estimates that 86% of the country’s enterprises are either micro enterprises that operate informally or family businesses without proper business registration. There are few programmes in place to tackle informality, save some measures to streamline and enhance company registration procedures.

Development of legislation and regulatory policies affecting SMEs

The development of laws and regulations in Lao PDR is governed by the Law on Making Legislation No. 19/2012. This law stipulates that draft laws will be circulated to a range of stakeholders including the private sector, complete with an explanatory note and an impact assessment, and that the Ministry of Justice will only consider laws submitted with these two documents attached. Lao PDR is still in an early phase of simplifying regulations that may impact small businesses and of applying good regulatory practices (GRPs). However, the country has a relatively embedded practice of public-private consultation, and has been developing tools and programmes to socialise the use of RIA among regulators since 2009.

Many activities to foster GRPs took place as part of the ADB’s Second Private Sector and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Development Programme (2009-11). As part of this programme, an inter-ministerial RIA task force was established in 2009, headed by MIC. The task force drafted a national RIA strategy and a five-year action plan to institutionalise a regulatory review process across government. A pilot RIA programme and implementation unit were established within MIC. This unit developed a set of RIA guidelines and selected a set of legislations that would go through the RIA process between 2010 and 2011. To facilitate more systematic and active dialogue between government and the private sector, a number of provincial private–public dialogue forums were established.14 Under this programme, both RIA and public-private consultations had a focus on SMEs.

Since completion of this project, the use of RIA has been continued and extended. However, the capacity to conduct a rigorous assessment remains rather low and in practice rarely includes consideration of SMEs. This move away from an SME focus is demonstrated by the decision in 2015 to transfer the RIA unit from the MIC to the Ministry of Justice. Impact assessments now consider broad economic impacts, social impacts and government impacts over a five-year horizon. Likewise, public-private consultations generally take place through national chambers of commerce, and these consultations do not strategically select or strongly represent SME stakeholders.

Company registration and ease of filing tax

Launching a company is relatively burdensome in Lao PDR. Eight types of company are recognised in the company register, of which the most common is a sole proprietorship. Launching a company currently takes around 67 days, costs 3.4% of income per capita and involves eight procedures.15 None of these steps can be fully completed online, and the applicant must interact with 11 different agencies (more if it is an agricultural company).16 Registering to pay VAT is a particular bottleneck as it takes around three weeks (World Bank, 2017[9]). Measures could be taken to streamline this procedure. Currently the registration of domestic companies falls under the institutional mandate of the MIC’s Enterprise Registration and Management Department. This department and the Tax Department (Ministry of Finance) currently use different company identification numbers, but there is a plan to consolidate these two numbers into one. First, however, the Tax Department must reform its information and communications technology (ICT) systems to be compatible with the Enterprise Registration Department; a project is ongoing to achieve this. Lao PDR currently has only two one-stop shops to consolidate business registration, both of which are in the capital. One is for domestic companies (within the MIC) and the other for foreign companies (within the Ministry of Planning and Investment).17 Some Lao enterprises are known to the authorities but only partially registered. This is because enterprises can select to register with provincial district centres in lieu of the MIC, and these centres are then required to share this information with the ministry. Such centres are currently operating in 147 districts (all save one), but only 32 districts have sufficient ICT systems in place to synchronise this information with the ministry, and therefore only these centres can issue licenses.

Tax filing is also rather burdensome. To comply with tax filing regulations, a company must file 35 payments per year, taking 362 hours on average, although a relatively low rate of tax is applied by international standards, at 26.2% of total profits. Steps could be taken to streamline the payment of VAT, which currently takes 219 hours, or about 60% of the total time required to file tax.

E-governance facilities

E-governance platforms are at an early stage of development in Lao PDR. The country’s Law on Electronic Transactions (2012) could be extended to the use of e-signature, though this may require further enhancements. Two institutions have undertaken activities to develop e-governance platforms, the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Post and Communications, and this may limit their coherence. Financial support to develop e-governance platforms is being sought from development assistance agencies.

Facilitating SME access to finance (Dimension 3)

Lao PDR has a relatively underdeveloped financial sector according to global indicators. It is ranked 75th for financial market development by the World Economic Forum (WEF, 2017[8]) and 77th for ease of getting credit by the World Bank (World Bank, 2017[9]). The country receives higher scores than its mean for the legal rights index and affordability of financial services, but its overall score is substantially diminished by a low performance on indicators of access to and regulation of equity instruments, as well as bank soundness. SMEs may find it difficult to access formal external finance and a relatively limited range of products are available. When loans are extended, collateral requirements are very high, averaging 275.9% of the value of the loan in some surveys (World Bank, 2016b[10]), and there are few measures in place to address this. Overall, the country has a low level of financial intermediation. Domestic credit to the private sector, a proxy measure of this, stood at only 20.9% of GDP in 2010, the last date for which data is available (World Bank, 2016a[2]). The country’s Dimension 3 score of 2.36 reflects these findings.

Legal, regulatory and institutional framework

For debt financing, facilities to assess and hedge against credit risk are available but still in an early phase. A credit information registry, the Credit Information Bureau (CIB) of Bank of Lao PDR (BOL), was created in 2010, but it still covers only around 11.2% of the population (World Bank, 2017[9]).18 The BOL is currently in talks with international financial institutions to reform its credit reporting system, for instance by allowing for the creation of private credit bureaus. Financial institutions also face limitations in utilising contracting elements such as securitisation to mitigate credit risk. The government has enacted a series of reforms to enhance its secured transaction framework, notably via the 2005 Law on Secured Transactions No. 06/NA, which permitted security over movable property, including intangible property (such as intellectual property) by way of a pledge,19 and the 2011 Decree on the Implementation of the Secured Transaction Law No. 178/PM, which eliminated a requirement to register the asset with a notary and created an online movable assets registry, the Registry Office for Security Interests in Movable Property. However, issues remain with enforcement. In order to ensure full enforcement, it is still necessary to be notarised,20 and effective debt resolution is hindered by the lack of a court system and the outdated Law on Bankruptcy of Enterprises. A cadastre is in place, but a large share of land property is not formally registered21 and the vast majority of land rights are still transferred in informal markets (OECD, 2017[14]). Digitisation of the cadastre is at an early stage.

For equity financing, the country has had a stock market since 2012, the Lao Securities Exchange (LSX), but it remains relatively shallow and illiquid. Only five companies are currently listed on the LSX, with a combined market capitalisation of around USD 1.34 billion as of March 2017 (OECD, 2017[14]). The first company to be listed on the exchange was Electricité du Lao PDR-Generation Public Company, which accounts for more than 80% of the exchange’s market capitalisation. Given the bourse’s limited depth and turnover, it makes sense that a specialised SME platform has not yet been established. Consequently, no public programmes are in place to facilitate the listing of SMEs.

Sources of external finance for MSMEs

The government has a few instruments in place to stimulate bank lending to SMEs. One of its main instruments is the Lao Development Bank (LDB), a specialised government-owned development bank that was formed through merger in 2003 to address the missing market and that was transformed in 2008 to focus on SME lending. In addition, credit lines are provided for SME lending, and associated loans are extended with an interest rate cap. Through the SME Promotion and Development Fund (SPDF), the LDB can provide loans to SMEs at a capped interest rate of 9%-10% per annum. Between 2012 and 2018, this scheme provided loans worth LAK 52.7 billion to 128 SMEs. Between 2016 and 2018, the SPDF and the World Bank also co-financed a scheme to provide a credit line to three banks (ST Bank, Sacom Bank and the Lao-China Bank) for SME loans capped at a low interest rate of 3%-4%. There is no public (or private) credit guarantee scheme operating in the country, although DOSMEP and the BOL are currently looking into developing one, perhaps financed through the SPDF. There is no government-sponsored export financing schemes.

One of the main sources of external financing for MSMEs is microfinance, provided through the country’s wide network of village banks. These institutions were originally set up by NGOs and donor agencies after the country began to open up in the 1990s, and they have proliferated since then. Accurate data on the village banks are scarce. But according to estimates, members numbered around 430 000 (6% of the Laotian population) in 2011 and they held an aggregated loan portfolio of around USD 37 million (GIZ, 2012[15]). There are few programmes to increase regulatory oversight of these institutions or to support other financial institutions in providing microfinance products.

Leasing products are becoming increasingly available in Lao PDR, with the number of specialised leasing companies increasing from 9 in 2013 to 30 by 2017.22 However, they are mainly used to purchase consumer goods, particularly automobiles, and are not commonly used by SMEs to secure corporate credit. Leasing companies are regulated by the BOL. Other asset-based instruments are available but they operate at a relatively low volume, partially due to difficulties in liquidating assets.

Equity instruments are very scarce in Lao PDR, but this is mainly due to a lack of viable business ideas and of founders able to pitch convincingly in English. There are no private equity/venture capital (PE/VC) firms based in the country, but start-ups can still access funds, particularly those focused on the Mekong region, such as the Mekong Angel Investors Network or various initiatives of the Mekong Business Initiative. There are no government programmes in place to stimulate PE/VC financing, but this is wise given the limited mass of such firms as well as the need to address more pressing issues. No regulatory framework for PE/VC financing is in place.

Enhancing access to market and internationalisation (Dimension 4)

With a score of 2.45 for this dimension, Lao PDR is still at an early stage of developing policies to improve SME market access and internationalisation. Since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) on 2 February 2013, Lao PDR has conducted policy reforms to conform to WTO agreements and create a favourable environment for business operations and attracting investment. Particular emphasis has been given to reducing trade procedures and promoting transparency and predictability in importing and exporting goods. Nevertheless, support for SMEs needs to be strengthened in many areas of business internationalisation.

Export promotion

Lao PDR has shown increasing concern to promote the growth of SMEs, including by exporting their products. Through the 2011 SME Law,23 the government encourages all sectors to support SME access to markets. Initiatives to promote SME exports have mainly been channelled through MIC, via DOSMEP, the Department of Import-Export and the Department of Trade Promotion.

Nevertheless, Lao PDR is still developing strategies to expand its SMEs’ access to international markets and to enhance their competitiveness in export activities. Many export promotion initiatives for SMEs are still fragmented and rely on support from foreign donors. In February 2017, the country’s first SME Service Centre was established at the office of the Lao National Chamber of Commerce and Industry (LNCCI), at a cost of USD 100 000. The service centre provides SMEs with updates on market information and connectivity through seminars and training sessions, with support from a Lao-German co-operation project known as the Regional Economic Integration of Lao PDR into ASEAN, Trade and Entrepreneurship Development (RELATED). In December 2017, Germany’s GIZ organised a review of implementation of the RELATED project. In another example of support activities, an Effective Export Marketing Workshop was conducted in October 2017 by the Hinrich Foundation, in partnership with World Wide Fund for Nature-Lao PDR, to improve the knowledge and practical skills of SMEs for promoting their products overseas (Keopaseuth, 2017[16]).

The government has also engaged SMEs in trade fairs to expose them to opportunities to gain greater market access and product awareness. For example, the MIC co-organises an annual Lao-Thai Trade Exhibition/Thailand Week in Vientiane with Thailand’s Department of International Trade Promotion to display products from Lao and Thai SMEs. The 2015 exhibition was followed by short vocational training sessions run by experienced trainers from Thailand’s Nong Khai Vocational College and designed to build the capabilities of Lao SMEs to develop their products. In September 2017, an Indonesian Trade and Tourism Fair was conducted in Vientiane as part of a set of events to mark the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two countries (KPL, 2017[17]). The event, which displayed SME products from both countries, featured a workshop on product packaging for Lao SMEs and a batik workshop to introduce Indonesian cultural heritage. Such exposure can help SMEs to expand their knowledge about overseas markets and establish business connections with overseas trading partners.

Integration to GVCs

Lao PDR articulated its commitment to facilitate SME integration into global value chains (GVCs) in its 2011 SME Law.24 Under the law, SME integration into GVCs is to be achieved through foreign investment projects to encourage local materials sourcing and transfer of technology and skills to local SMEs, and through the development of business clustering. Specific strategies and actions to establish SME linkages with GVCs were not mentioned.

As of January 2016, the country had established three special economic zones (SEZs) and 10 specific economic zones and was preparing to develop another specific economic zone in Hadxaifong district near the Thai border (The Nation, 2016). In August 2017, the government invited a Chinese company, Guangdong Yellow River Industrial Group, to conduct a feasibility study on development of the Khonphapheng SEZ in Champasak province (Xin, 2017[18]). The Pakse-Japan SME SEZ is also in Champasak province, which borders on Thailand and Cambodia. Developed since 2015 by Nishimatsu Construction Co. Ltd. and Savan TVS Consultant Co. Ltd., it aims to provide business clustering for small businesses.

The government has so far focused on attracting large-scale investors to invest in the country’s SEZs, mainly through tax exemption schemes, rather than defining ways to foster SME integration into GVCs through SEZ development. As of April 2017, 239 foreign companies had a presence in Lao SEZs, compared to 57 companies owned by Lao private entities and 22 joint ventures. The new Law on Investment Promotion,25 enacted in 2016, does not specify any measures to promote SME linkages with larger companies and multinational corporations (MNCs) or technology and skills transfer from such companies to SMEs. In its 2017 Investment Policy Review on Lao PDR, the OECD noted that SEZs had the potential to play a key role in transforming the economy and that measures should be taken to encourage linkages between MNCs and SMEs.

Initiatives with the potential to establish business linkages between Lao SMEs and MNCs have emerged with support from foreign donors. Some are aimed at attracting foreign SMEs to expand into Lao PDR and at promoting business matchmaking with Lao SMEs. In July 2016, for example, Thailand’s Krungsri (Bank of Ayudhya PCL) organised a programme for Thai SMEs and entrepreneurs to do business in Lao PDR through a business matching event called “Krungsri Business Journey: The Opportunity in Lao PDR” (Krungsri, 2016[19]). In March 2017, an event called “The Lao PDR-China Roadshow for Bank of China SMEs Cross-Border Trade and Investment Conference” was held to present a Chinese service to enhance linkages between Lao SMEs and Chinese businesses. The event, held in Vientiane, was organised by SMEPDO, the LNCCI and Bank of China.

Use of e-commerce

E-commerce is still in an early development phase in Lao PDR, and the country does not yet have a full set of laws to regulate e-commerce activities. As of December 2016, Lao PDR had an estimated 1.5 million internet users, or about 22.1% of the total population, according to Internet World Stats. It has a Law on Electronic Transactions, but its Law on Consumer Protection does not yet cover e-commerce. More specific laws on e-commerce are under consideration.

Nevertheless, several initiatives have been taken to promote the use of e-commerce among Lao SMEs. A key initiative is Plaosme, an e-commerce platform launched in August 2017 to support Lao SMEs in their e-commerce and export capability. The platform was developed under the Lao SME Export and E-commerce Development (SEED) project by DOSMEP and the MIC’s Department of Trade Promotion, in collaboration with the LNCCI. It offers a digital marketplace, business matching and access to trade associations across ASEAN, among other services. Although registration is free for Lao SMEs, many Plaosme services are not free of charge. Use of the programme is picking up steam, with the number of registered companies increasing from 48 in February 2018 to 118 in March 2018, according to the Laotian Times, which added that 72 of the registered companies were owned by women.

Another initiative to facilitate e-commerce is the e-payment service of Banque pour le Commerce Extérieur Lao (BCEL), a state-owned commercial bank. Since 2013, BCEL’s e-payment service has been the only financial technology available in the country. In co-operation with CyberSource, a California-based e-commerce credit-card payment system, BCEL provides an online payment service that allows businesses to accept online payments at any time from anywhere around the globe. Lao PDR may soon enjoy another e-payment service: Thailand’s currency exchange company, SuperRich, has confirmed that it is working on a digital platform for foreign exchange, cash transfers and payment services and that it is seeking approval from the Lao authorities (Fintech Singapore, 2017[4]).

Quality standards

Lao PDR is working to develop infrastructure to promote quality standards compliance. The Department of Standardisation and Metrology (DOSM) was established in 2011 under the Ministry of Science and Technology and is now a participating member of International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO). A technical agency called the Lao National Accreditation Bureau (LNAB) is currently being formed within DOSM, according to the Lao Trade Portal. LNAB will participate in International Laboratory Accreditation Co-operation and the International Accreditation Forum. It will seek candidates to become certified accreditation assessors. Selected candidates will receive training and be certified in accordance with international requirements. The Lao Trade Portal also provides information on national standards.

As the national standardisation system is still being developed, initiatives to support SME compliance have not been defined. But capacity-building activities on quality standards development and compliance have emerged under the National Quality Infrastructure framework, part of the Trade and Private Sector Development Roadmap developed with support from the Enhanced Integrated Framework.26 In May 2015, a one-day workshop for SMEs was held in Vientiane on quality management and how to help SMEs to generate more revenue, implement quality activities and improve product safety. DOSM staff have participated in other workshops on quality standards. On food safety standards, LNAB will establish a food administration and inspection system in co-operation with Nakhone Sup Group Sole Co. Ltd., a Lao private enterprise, under a memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed in February 2017 (Xinhua, 2017[20]).

Trade facilitation

Lao PDR, which is still in the development phase of trade facilitation, garnered low scores in the 2017 OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (TFIs) used in this 2018 ASPI. Nevertheless, the country has moved forward with trade facilitation programmes. It established the Lao National Single Window (LNSW) under the Ministry of Finance, the MIC and the Lao Customs Department, and has worked to develop the LNSW and integrate it within the ASEAN Single Window (ASW) through the US-ASEAN Connectivity through Trade and Investment (US-ACTI) project. Lao PDR has also installed Asycuda, an automated customs management system, at 11 of its international border check points, such as the Thanaleng border post and the Namphao International border check point, with support from the World Bank and other donors. Asycuda is being developed to be rolled out to all border posts nationwide. An Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) programme is being implemented.

Lao PDR has established a National Committee on Trade Facilitation, which is chaired by the prime minister; the MIC serves as its secretariat. In 2017 the country adopted a Trade Facilitation Roadmap for 2017-2020. This Roadmap aims to reduce time and costs in business operation through one-stop inspection, improved LNSW service, the AEO programme and linkage of customs clearance with neighbouring countries. The roadmap has six strategies for facilitating trade: i) developing institutional mechanisms for effective co-ordination among line departments; ii) strengthening governance structure at the subnational level for improved communication, implementation and monitoring of trade facilitation measures; iii) cross-border co-operation and regional integration; iv) collaboration with the private sector; v) promoting simplification of procedures through a one-stop inspection service that has been initially implemented by the Trade Facilitation Secretariat; and vi) full implementation of the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement. Many of Lao PDR’s trade facilitation programmes are financed under the multi-donor Second Trade Development Facility Project (TDF 2).

The Lao Trade Portal plays a key role in promoting transparency and predictability in cross-border trading. It is home to the National Trade Repository, which disseminates information on tariff nomenclature, rules of origin, non-tariff measures, administrative rulings and national trade and customs laws and rules. It also serves as an enquiry point and a one-stop source on the basic steps of import and export procedures. Despite its progress on developing trade facilitation infrastructure, Lao PDR still lacks measures and initiatives specifically aimed at helping SMEs to deal with customs procedures. Integrating a support system for SMEs within the trade facilitation framework could facilitate SME growth beyond domestic borders and help Lao businesses to thrive in global trade.

Boosting productivity, innovation and adoption of new technologies (Dimension 1 and 2)

Lao PDR is seeking to promote productivity and productive agglomerations, but the actions it has taken correspond to the resources currently available in the country. The economy suffers from low labour productivity and an inadequately educated workforce. This affects not only the quality of jobs but also the country’s capacity to attract investment. While real wages have continuously risen over time, labour productivity has not improved, affecting firm-level competitiveness. Low productivity also affects the development of SMEs and hinders the creation of business linkages with foreign affiliates. Although some good initiatives are in place, more could be done in this area. Lao PDR’s Dimension 1 score of 2.76 indicates that some policy work has taken place, but that further efforts, especially related to implementation, would be welcome.

Lao PDR has only recently started to develop policies related to the greening of SMEs, although this subject has traditionally been important in the country. With a Dimension 2 score of 1.94, the country is still at an early stage of policy development in this area.

Productivity measures

DOSMEP, under the MIC, is the main policy development and implementation agency for national productivity, including SMEs. DOSMEP also functions as the country’s National Productivity Organisation, which co-ordinates with the Asian Productivity Organisation. Productivity growth is at the core of the 8th National Socio-economic Development Plan 2016-2020 as well as the SME Development Plan 2016-2020. DOSMEP co-operates with the Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Education and Sport, the LNCCI, academic institutions and line ministries in the implementation of productivity-related programmes for SMEs. Private-sector consultations took place during the policy development process.

The government promotes SME productivity and innovation by seeking to make working methods more industrial and more creative. Policies include: enhancing the efficiency of production and service management; providing matching grants of up to 50% to support investment in technology transfer; training and dissemination of information on new innovations in production management, product design and development; and production and services improvement. DOSMEP provides training and consultancy to SMEs regarding productivity enhancement. In addition, it assists entrepreneurs to be trained abroad to improve the quality of products, but mainly in the agro-food sector. However, the budget for productivity enhancement programmes is limited and is mostly funded by donors, and existing programmes cover only a limited number of SMEs. Furthermore, there are no clear government key performance indicators (KPIs) on productivity.

Business development services

The government has a policy that specifically addresses business development services (BDS) for SMEs and would-be entrepreneurs, but there is no dedicated strategy. The SME Development Plan 2011-2015 had a specific focus on BDS. The new plan for 2016-2020 aims to increase the ratio of SMEs that have received BDS from 4.28% in 2013 to 30% in 2020. DOSMEP is the main policy-making body for BDS services.

In terms of implementation, DOSMEP has a government budget for BDS that is approved annually, but it is limited and donor funding plays an important role. The main programme, the Business Assistance Facility, offers advice on business growth plans and covers up to 50% of associated costs. At least 228 companies have benefitted from this programme. The Lao-India Entrepreneurship Development Centre has implemented a training course on New Enterprises Creation offering capacity building and support with business plan development, mainly for students. The government provides online information on the most relevant programmes and has developed a list of institutions and experts on the provision of support and services. A pilot SME Service Centre was established in 2017 in Vientiane by DOSMEP, the MIC, and the LNCCI, in co-operation with GIZ.

Productive agglomerations and clusters enhancement

The recently amended 2016 Investment Promotion Law provides the legal basis for the establishment and development of Special Economic Zones in Lao PDR. The SEZs consist of industrial zones primarily focusing on the ICT, services, trade and tourism sectors.

Lao PDR scored 85% in the 2014 ERIA FIL assessment, an increase of five percentage points since 2011. Despite improvements in foreign investment liberalisation, it is still below the ASEAN median. Lao PDR is one of three countries in ASEAN where the agriculture and natural resources sector is more open than the manufacturing sector. Currently, there are two active SEZs in the country. Few linkages between foreign affiliates and local firms currently exist, notably due to the type of FDI attracted and the lack of absorptive capacities of local SMEs (OECD, 2017[14]). Also, most companies currently operating in Lao PDR’s SEZs are foreign-owned, and their links with local enterprises, including SMEs, could be further enhanced. Incentives for special economic zones and specific economic zones are in compliance with the Decree on the Establishment and Activities of respective zones (areas). They include corporate tax exemption from four to ten years for zone 1 in the agriculture, industry, handicraft and service sectors. There are also some non-fiscal incentives such as immigration benefits for foreign investors. Monitoring mechanisms are very limited and KPIs have not been developed.

Technological innovation

A specific innovation strategy is under development in Lao PDR. The country’s current Science and Technology Strategy (2016-2025) mainly covers innovation-related issues and includes six action plans, including a Technology and Innovation Action Plan. This plan, which was developed by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MST), does not have a focus on SMEs. The Department of Intellectual Property at MST is a dedicated agency for technological innovation and plans to establish Technology Innovation Support Centres (TISCs). MST also has a goal to develop sustainable innovation infrastructure.

The Department of Technology and Innovation is the body responsible for implementation and co-ordination with relevant stakeholders. However, its resources are limited and its staff of only 44 covers the entire country. There are currently no government-funded programmes to support innovative SMEs. Only ad hoc activities have taken place, mainly in partnership with donors and focused on awareness raising and incubation support through donor assistance (GIZ). Some academic institutions promote technology transfer and are trying to develop curricula on the promotion of technologies. The only infrastructure in place for local SMEs is LIBIC, an information technology business incubation centre managed by the Faculty of Engineering at the National University of Lao PDR. The centre was set up with donor support (JICA). There is a plan to establish innovation demonstration centres in three regions.

The intellectual property rights (IPR) framework in Lao PDR is still under development, but matters are improving. A comprehensive intellectual property law has been in place since 2012 covering most areas of IPR. Protection and enforcement of IPR is still relatively weak. However, the law offers a fairly efficient system for registration of most major IPR. A recent advance was the enactment of an MST decision on the implementation of geographical indications under the Law on Intellectual Property.

Environmental policies targeting SMEs

Lao PDR is still developing environmental policies targeting SMEs. Several national plans – the National Socio-Economic Development Plan 2016-2020, the National Tourism Plan 2016-2020 and the Agriculture Plan – will impact SMEs, but they do not lay out environmental policies for them and do not include policies that specifically support the greening of SMEs. Other national plans, which focus on environmental sustainability, target larger enterprises and are less likely to impact SMEs. These include the Environment Protection Law, which sets standards for natural resource use and provides for the use of clean technology and good practices for waste generation and disposal, and the National Renewable Energy Strategy, which establishes targets for renewable energy.

Since mid-2017, the government has worked with the World Bank to conduct its First Programmatic Green Growth Development Policy Operation. The project supports the development of a national strategy for green growth and the mainstreaming of green growth principles across the national development strategy. The green growth plan that results from this project is an exciting opportunity to support the greening of SMEs.

Incentives and instruments for green SMEs

Lao PDR currently has no regulatory incentives to support the greening of SMEs and, as noted above, its approach to environmental regulation targets larger projects rather than SMEs. However, this may change as the country updates its approach to environmental regulation and support for green growth. In terms of financial incentives and support schemes, the government has provided some funding for enterprise greening, but this is not specifically targeted at SMEs. A number of projects have been developed through the SWITCH-Asia programme funded by the EU, including support for eco-labels in specific sectors, sustainable supply-chain management and cleaner production. Greening also plays a role in some donor-funded projects. Under the Lao PDR-World Bank Small and Medium Enterprise Access to Finance Project, for example, participant SMEs must fulfil certain environmental criteria prior to being granted a loan. Recently, the SME Promotion and Development Fund signed an MoU with the Lao Viet Bank to provide loans to SMEs under this project, and again only environmentally friendly SMEs can participate.

Stimulating entrepreneurship and human capital development (Dimensions 7 and 8)

Nearly 60% of Lao PDR’s population is under 25 years old, according to a 2015 estimate by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), making human capital development an important element to unlock the country’s growth potential (UNFPA, 2015[21]). As the large majority of businesses in Lao PDR are SMEs, it is essential for the country to increase its commitment to invest in entrepreneurial education and skills promotion. Lao PDR relies heavily on donor support to promote entrepreneurship and is in a developing phase of elaborating its own support policies. This is reflected in its Dimension 7 score of 2.29. In Dimension 8 on social enterprises and inclusive SMEs, Lao PDR scores only 2.05, placing it at an early stage of policy development in this area as well.

Entrepreneurial education

Lao PDR has been developing its education system to improve integration of entrepreneurial learning (EL) elements, in recognition of the importance of nurturing entrepreneurial mindsets and skills from an early age. Developing quality human resources with high skills and professionalism to respond to the demand for entrepreneurs is a main objective of the latest Education and Sports Sector Development Plan (2016-2020) of the Ministry of Education and (MoES, 2015[22]). The plan aims to enhance lower secondary curricula to include adequate content on basic vocational and entrepreneurship by developing manuals and instructional materials. It encourages entrepreneurs to participate in aligning national curricula standards and the national education qualifications framework with business-world requirements. In addition, the latest SME Development Master Plan 2016-2020, developed with World Bank support, outlined New Entrepreneur Creation and Development as a key focus area.

Entrepreneurship education development has received support from multiple foreign donors. An example is the introduction of EL elements through the Know About Business (KAB) package. Developed with support from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and adopted by Lao PDR’s Ministry of Education and Sports in 2010, KAB has been rolled out through the national curriculum for upper secondary schools. In partnership with the Lao-India Entrepreneurship Development Centre (LIEDC), teacher training courses have been conducted to deliver the KAB package. The latest KAB training session, on 24-28 July 2017, was attended by 39 participants. It is difficult to determine how KAB has been implemented in schools, as monitoring and evaluation information has not been published. Other donors have supported vocational education. The Korea International Co-operation Agency provided grant aid amounting to USD 5 million to facilitate skills development via a 2017-2020 project to improve the Lao-Korea Skills Development Institute, while Lao-German co-operation programmes supported the development of Vocational Education and Training schools in Sayaboury and Houaphan in 2013.

In 2016, the ADB proposed the second Strengthening Higher Education Project (SHEP) to build on the achievements and lessons learned from the first SHEP in 2009 (ADB, 2009[23]). The project introduced innovative approaches to improving higher education in Lao PDR. The second SHEP, with a focus on entrepreneurship training, was to provide support to four public universities: Champasak University, National University of Lao PDR (NUOL), Savannakhet University and Souphanouvong University. It aims to develop standards, curricula and instructional materials for entrepreneurship programmes and to train relevant administrative and academic staff by 2018. Laotian universities have shown increased awareness of developing EL on their campuses. A delegation from NUOL, a leading university in Vientiane and a partner of the Greater Mekong Sub-Region Academic and Research Network (GMSARN) and the ASEAN University Network (AUN), recently visited Kobe University in Japan to discuss entrepreneurial training and the possibility of future co-operation (Kobe University, 2017[24]).

Entrepreneurial skills

Despite rising awareness in Lao PDR of the importance of fostering entrepreneurship knowledge and skills, initiatives and activities have been fragmented, with heavy reliance on donor support and partnerships with foreign entities. One notable initiative to enhance Laotian entrepreneurial skills is through training courses and other capacity-building activities under LIEDC. Established under the India-ASEAN Fund and inaugurated in Vientiane in 2004, LIEDC has since trained Lao entrepreneurs to set up small and medium-scale businesses, with ILO support to ensure the training quality. Examples of capacity-building activities under LIEDC include New Enterprise Creation training in December 2017 and a three-month training course on entrepreneurship conducted in March 2017. However, the mechanisms for aspiring entrepreneurs to participate in the LIEDC training sessions are not clear. It is also not clear whether any incentives for participation, like training grants, have been introduced.

Other initiatives to increase skills among Laotian entrepreneurs are taking place under ASEAN-wide co-operation schemes. For example, the ASEAN SME Academy has sponsored capacity-building activities. The academy is a multi-stakeholder collaboration under the US-ASEAN Business Alliance, with support from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the US-ASEAN Business Council. In October 2016, a two-day training-of-trainers programme took place in Vientiane with representatives from the Young Entrepreneurs Association, LIEDC and other organisations. Another initiative is sponsored by the ASEAN Centre of Entrepreneurship (ACE) platform. The first start-up support services platform in ASEAN, ACE provides key services to help SMEs grow their business. The platform is supported by the Malaysian Global Innovation and Creativity Centre (MaGIC) and has operated throughout ASEAN. Support provided under ACE in Lao PDR includes co-working space and start-up assistance by Asiastar, business incubation services by the Lao IT Business Incubation Centre and a community for entrepreneurs by the Young Entrepreneurs Association of Lao PDR.

Social entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurship is a relatively new concept in Lao PDR and there is no formal shared definition for social enterprise. The National University of Lao PDR has conducted studies covering the concept of social enterprise. Social development is covered by the 8th National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020), but social enterprises are not mentioned directly. Decrees on the establishment of associations and international non-profit organisations were issued in 2009 and 2010 respectively, and more than 30 organisations have since registered with the Ministry of Home Affairs as an association or foundation. It is not clear which ministry would have a mandate to cover social enterprises in Lao PDR. The Ministry of Agriculture has a mandate to cover co-operatives.

Although government actions have not been identified yet, private initiatives have taken place. Several social enterprises are operating in the country, but they had to be registered as for-profit organisations. One example is Xaoban, a social enterprise in Vientiane that produces high-quality food products using local ingredients and, according to its website, supports local farmers and “socially marginalised people from across the country”. The Participatory Development Training Centre (PADETC) provides capacity building for non-profit organisations to improve the skills of small businesses. PADETC manages a Small Grants Fund, supported by Oxfam Novib. Grants of USD 5 000 to USD 10 000 are available for institutional strengthening and programme support, especially in the areas of agriculture, education and youth development. Actions have also been taken by associations. For example, the Lao Business Women’s Association organised a workshop on Women Social Entrepreneurship Development in 2015.

Inclusive entrepreneurship

Lao PDR has a number of policies for promoting women entrepreneurship. In 2006, it developed a National Strategy for the Advancement of Women 2011-15 (NSAW). The National Commission for the Advancement of Women in Lao PDR, which oversees the strategy, is the focal point for gender mainstreaming within the government. The Lao Women’s Union, the main policy development body on women’s entrepreneurship, has begun preparing NSAW for the 2016-2020 period. Few implementation activities have taken place, but there is a plan to establish a Women’s Entrepreneurship Development Centre in Vientiane with the support of USAID. The centre is expected to provide a space for women to learn the skills they need to start and develop a business. It is being planned by the Lao Women’s Union, the Lao Handicraft Association, the LNCCI, the Lao Business Women’s Association and the Lao Microfinance Institution. Microcredit institutions are present in the country and are active with women entrepreneurs.

Lao PDR has identified the promotion of youth entrepreneurship as a policy priority under the country’s SME Promotion Law and its SME Development Plans for 2011-15 and 2016-20. There are currently a few programmes in place, and the Lao Youth Union has been designated as the main policy co-ordination body. Initiatives are generally organised by LIEDC (under the Higher Education Department of the Ministry of Education and Sport), or by the Young Entrepreneurs Association of Lao PDR. These typically take the form of awareness-raising and capacity-building events, or the provision of mentorship support. A few years ago the government launched a pilot STEPS project (2011-13) with the World Bank, which focused on supporting 200 young entrepreneurs, mainly women, with a particular focus on career counselling.

The Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare is the main co-ordination body for developing policy for the promotion of entrepreneurship for persons with disabilities (PWD). Although there is no dedicated strategy, the Lao Disabled Women’s Development Centre is relatively active and provides training to some 30 participants a year on issues including entrepreneurship. This work is based on the previous projects INCLUDE and WEDGE supported by the ILO.

The way forward

Strengthening the institutional, regulatory and operational environment

Lao PDR has a rather strong institutional framework for SME policy, particularly given its income level, but the operational environment for SMEs is still fairly burdensome. Going forward, Lao PDR could:

Institutional framework for SME policy

-

Enhance SME statistics. Access to reliable data on Lao PDR’s enterprise population will be a crucial element for designing and delivering targeted SME policies. To increase the accuracy of these statistics, Lao PDR could seek technical assistance from international or bilateral agencies with demonstrated expertise.

-

Consider reviewing the country’s SME definition. The fact that Lao PDR includes three criteria and three sectors in its SME definition decreases its ease of use and its likelihood of being applied consistently through the public administration. The government could consider setting up a working group to review and potentially update the definition, taking into account administrative capacity and the current structure of Laotian firms.

-

Consider re-establishing an SME policy committee. SME policies are gaining high-level traction in Lao PDR, but awareness and co-ordination of targeted SME policies remain limited, partially due to capacity constraints. Lao PDR could use the current high-level interest in SME policy to re-establish an SME policy committee. This type of institution can play an important role in co-ordinating and sequencing policies, ensuring high-level and inter-ministerial engagement and co-ordinating interventions with development assistance agencies.

Legislation, regulation and tax

-

Send key officials to study the use of RIA in other AMS. Lao PDR has taken significant steps to inculcate good practices in the process of developing regulations. More practical use of such methods could facilitate their increased adoption. This could be achieved by sending key officials to observe other AMS policy makers who have demonstrated expertise in this area. These officials could then train other regulators in Lao PDR on how to implement these practices.

-

Step up efforts to increase the ease of filing tax. Only around 9.4% of total tax revenue in Lao PDR currently comes from taxes on income, profits and capital gains, and procedures to file tax are relatively complicated. In conjunction with efforts to streamline tax filing more broadly, Lao PDR could draft a roadmap for the development of an online tax-filing platform. However, such a roadmap should take into consideration the fact that only around 22% of the country’s population currently have internet access, and therefore preliminary steps will be required before such a platform can operate at scale. Pilot steps could first be considered in urban centres.

Facilitating SME access to finance

Lao PDR has undertaken a number of reforms in this area over recent years, but credit information remains limited, movable assets are rarely accepted as a security and few government programmes are in place to stimulate MSME lending. To increase MSME access to credit, Lao PDR could:

-

Develop legislation to facilitate private credit bureaus. Credit information coverage in Lao PDR is currently rather low. Private credit bureaus, which provide financial institutions with value-added services such as credit scoring, could encourage more banks to report credit information, thereby increasing coverage.

-

Consider developing a credit guarantee scheme. Credit guarantee schemes can be a market-friendly instrument to encourage lending to SMEs. A diagnostic exercise could be completed to explore whether a credit guarantee scheme is desirable and feasible, as well as what form it should take.

Enhancing access to market and internationalisation

Despite progress in developing policies to help local businesses to go global, Lao PDR needs to define clearer mechanisms and support that is specifically designed to help SMEs unlock the potential benefits of utilising government programmes. Lao PDR could consider the following actions to expedite the progress of policy development in SME internationalisation:

-

Reduce or eliminate fees for SME capacity-building programmes. Allocating budget to decrease the fees for such programmes would make it easier for SMEs to get the assistance they need. Lao PDR has started to develop capacity-building programmes for SMEs under its Plaosme initiative. Eliminating the fee to access those programmes could help a great deal, although a symbolic contribution could be beneficial to ensure the commitment of the SMEs to the training.

-

Develop clear strategies to integrate SMEs into GVCs. Lao PDR is being progressive in attracting foreign investment into its growing SEZs. This provides an opportunity for the country to establish linkages between local SMEs and large companies and MNCs, if facilitated with laws and mechanisms to ensure the engagement of local SMEs in the SEZs.

-

Develop a programme to improve the quality of SME products. This would help SMEs to become more competitive in foreign markets. The programme could cover international standards compliance and aspects of product quality improvement, such as branding and product innovation. Initiatives could take the form of intensive training and financial support for SMEs to increase their product quality.

Boosting productivity, innovation and adoption of new technologies

To increase productivity, boost innovation, promote the adoption of new technologies and support the greening of SMEs, Lao PDR could:

Productivity, technology and innovation

-

Further develop clear implementation plans with dedicated budgets. These plans should promote productivity, the development of BDS and innovation. Although there are dedicated strategies, implementation often remains vague and covers few companies. With Lao PDR’s low level of resources, activities focused on improving labour productivity and education of the workforce should be a priority.

-

Build on links with the private sector. Lao PDR should take advantage of the presence of international companies to improve the skills of local SMEs. Policy measures could include: facilitating domestic companies’ participation in SEZs, especially manufacturing; further promoting the concept of responsible business conduct as a way of bridging skills gaps; and increasing productivity through links to the foreign companies.

-

Increase awareness about the benefits of improved productivity and innovation. Local SMEs are often not aware of the importance of innovation and how they can improve productivity. Information campaigns, awards and competitions could be a way forward. Involving the private sector and academia in developing such campaigns could be beneficial and help reach larger audiences.

Environmental policies and SMEs

-

Mainstream the greening of SMEs within existing policies. Lao PDR’s new green growth efforts should support the greening of SMEs. A horizontal approach will help all SMEs access support for more efficient and cleaner energy use. This would be preferable to a narrower focus on explicitly green industries.

-

Boost awareness of the advantages of greening. The government could further increase awareness among SMEs of the advantages of greening and could disseminate information on any support mechanisms available.

-

Conduct feasibility analysis. The government could build on good practice examples, such as those implemented through the SWITCH-Asia initiative, to determine which projects have worked so far and to fund them from the budget so that they have longevity and can reach a greater portion of SMEs.

Stimulating entrepreneurship and human capital development

Entrepreneurial education and skills

Lao PDR’s young population could make an important contribution to the country’s economic future. To tap into this potential, the country could develop more concrete measures to foster entrepreneurship in both the national education system and human-capital-related development plans. Several actions could be considered:

-

Use lessons learned from donor support to improve entrepreneurship strategy. Lao PDR could utilise the initiatives and programmes that have been conducted with donor support to come up with improved national strategic plans and strategic programmes on entrepreneurship promotion. Identifying the stumbling blocks encountered during the implementation of donor programmes would help put Lao PDR in a better position to address those challenges in formulating future strategic action plans and initiatives to nurture entrepreneurship.

-

Integrate monitoring and evaluation into entrepreneurship education. This is important to ensure the effectiveness of future entrepreneurial education schemes. Lao PDR should incorporate sound monitoring and evaluation mechanisms into the policy framework in formulating initiatives on entrepreneurial education and training.

-

Strengthen entrepreneurial education in schools at all levels of education. This would support Lao PDR in reaping the benefits of having a young workforce. Equipping young people with quality entrepreneurial skills would enhance SME competitiveness and foster the country’s economic growth.

Social and inclusive entrepreneurship

-

Develop a clear definition or set of criteria for social enterprise. The lack of a legal definition of a social enterprise sets the stage for confusion. It is important to clarify the definition or to set the criteria for identification as a social enterprise. It would be also beneficial to agree on which institution should hold the mandate for social enterprises, inclusive businesses and/or sustainable enterprises.

-

Develop policies integrating the specific needs of target groups. The government might consider developing strategies to meet specific needs of target groups, such as access to finance and specific training facilities as well as means of delivery. These points should be analysed and integrated into the action plan. The strategies should be implemented with the government budget or donor assistance.

-

Explore increased collaboration with the private sector. The government could consider collaborating with the private sector on social and inclusive entrepreneurship. Policy makers could enhance this collaboration by developing incentives and promoting responsible-business-conduct programmes that could help starting or would-be entrepreneurs get access to skills and business experience.

References

[23] ADB (2009), Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors: Proposed Asian Development Fund Grant to the Lao PDR for Strengthening Higher Education Project, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/199481/48127-002-rrp/pdf.

[1] ASEC (2016), AMS: Selected Basic Indicators, https://data.aseanstats.org/.

[12] GIZ (2014), HRDME Enterprise Survey 2013 for Lao PDR, GIZ, Vientiane, https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2014-en-hrdme-enterprise-survey-2013.pdf.

[15] GIZ (2012), Microfinance in the Lao PDR, https://www.giz.de/de/downloads/giz2012-en-microfinace-lao-pdr.pdf.

[4] IHA (2016), 2016 Hydropower Status Report, https://www.hydropower.org/country-profiles/laos.

[3] ILO (2016), Key Indicators of the Labour Market, http://www.ilo.org/ilostat.

[7] IMF (2018), Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Staff Report for the 2017 Article IV Consultation, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484348536.002.

[11] IMF (2017), Lao People's Democratic Republic: 2016 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Lao PDR, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., https://doi.org/10.5089/9781475579451.002.

[6] IMF (2017), World Economic Outlook Database, October 2017, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2017/02/weodata/weoselgr.aspx.

[16] Keopaseuth, P. (2017), “Hinrich Foundation and WWF-Lao PDR co-organize SME export marketing workshop”, Hinrich Foundation, http://hinrichfoundation.com/exporters-suppliers/hinrich-foundation-wwf-laos-co-organize-sme-export-marketing-workshop/ (accessed on 28 June 2018).

[24] Kobe University (2017), “Visit from the National University of Laos”, Kobe News, http://www.kobe-u.ac.jp/en/NEWS/info/2017_04_21_01.html (accessed on 15 February 2018).

[17] KPL (2017), “People flock to Indonesia trade and tourism fairs”, Lao News Agency, http://kpl.gov.la/En/Detail.aspx?id=28266.

[19] Krungsri (2016), “Krungsri bolsters business matching to boost trade network and Thai business growth in Lao PDR”, Krungsri News, http://www.krungsri.com/bank/en/NewsandActivities/Krungsri-Banking-News/krungsri-business-journey-lao.html (accessed on 15 February 2018).

[13] LSB (2013), Economic Census of Lao PDR.

[5] MIT (2016), Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/.

[22] MoES (2015), Education and Sports Sector Development Plan (2016-2020), http://www.dvv-international.la/fileadmin/files/south-and-southeast-asia/documents/ESDP_2016-2020-EN.pdf.

[14] OECD (2017), Investment Policy Review of Lao PDR, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276055-en.

[21] UNFPA (2015), “Lao PDR adolescent and youth situation analysis report”, UNFPA News, http://lao.unfpa.org/news/lao-pdr-adolescent-and-youth-situation-analysis-report (accessed on 18 February 2018).

[8] WEF (2017), Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018, World Economic Forum, Geneva, https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-competitiveness-report-2017-2018.

[9] World Bank (2017), Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs, World Bank Group, Washington D.C., http://hdl.handle.net/10986/28608.

[10] World Bank (2016b), Enterprise Survey of Lao PDR, http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/data/exploreeconomies/2016/lao-pdr.

[2] World Bank (2016a), World Development Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0683-4.

[25] World Bank (2016b), World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) dataset, https://wits.worldbank.org/.

[20] Xinhua (2017), “Laos to establish FDA-like food, drug, beverage quality inspection system”, SINA, http://english.sina.com/news/2017-02-10/detail-ifyamkpy8770331.shtml (accessed on 18 February 2018).

[18] Xin, Z. (2017), “Lao government approve Chinese company to conduct SEZ feasibility study”, Xinhua, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-08/02/c_136491811.htm (accessed on 28 June 2018).

Notes

← 1. Raw materials accounted for 47% of exported products (excluding electricity) in 2016 (World Bank, 2016b[25]).

← 2. Although this is down from 90.4% in 1970, and urbanisation has accelerated since 2000.

← 3. Save a blip in 1998, when GDP grew at a rate of 4% (a relatively small negative impact from the Asian Financial Crisis).