Chapter 9. What is the right financing for fragile contexts?

This chapter looks at ways to improve both domestic and international development financing in fragile contexts. It discusses the importance of increasing the coherence and complementarity of all financial flows and making sure that each finance strategy is tailored to the unique requirements of each fragile context. The chapter goes on to discuss which financial tools are appropriate in different cases, the impact of sequencing and timing of different financial flows, and best practices to ensure these flows provide the right incentives for stability and sustained peace.

The aspirations of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda require an updated approach to bringing together financial flows from public and private sources – both domestic and international – that mixes and matches ODA (aid) flows with local tax and customs revenue, private investment, remittances, philanthropic spending, loans, and other types of financing. Nowhere is this more important than in fragile contexts with the greatest potential risks and the greatest potential returns (Poole, 2018[1]) (Poole, 2018[1]).

To achieve these aspirations, leave no one behind and scale-up financing resources for fragile contexts requires getting four things right:

-

The right amount of financing

-

The right financing tools

-

Deploying finance over the right timeframe

-

Ensuring that finance delivers the right incentives for stability.

New approaches to financing for development bring in a more diverse cast of actors with different interests and experiences as well as new tools and ways of working. In addition, the challenges in fragile contexts vary significantly, as do the means at their disposal to attract and create development financing. As outlined in Trend Twelve (see Chapter 1), navigating systems with dual complexities – in this case, the complexities of both financing and fragility – will require an approach that is highly context-specific.

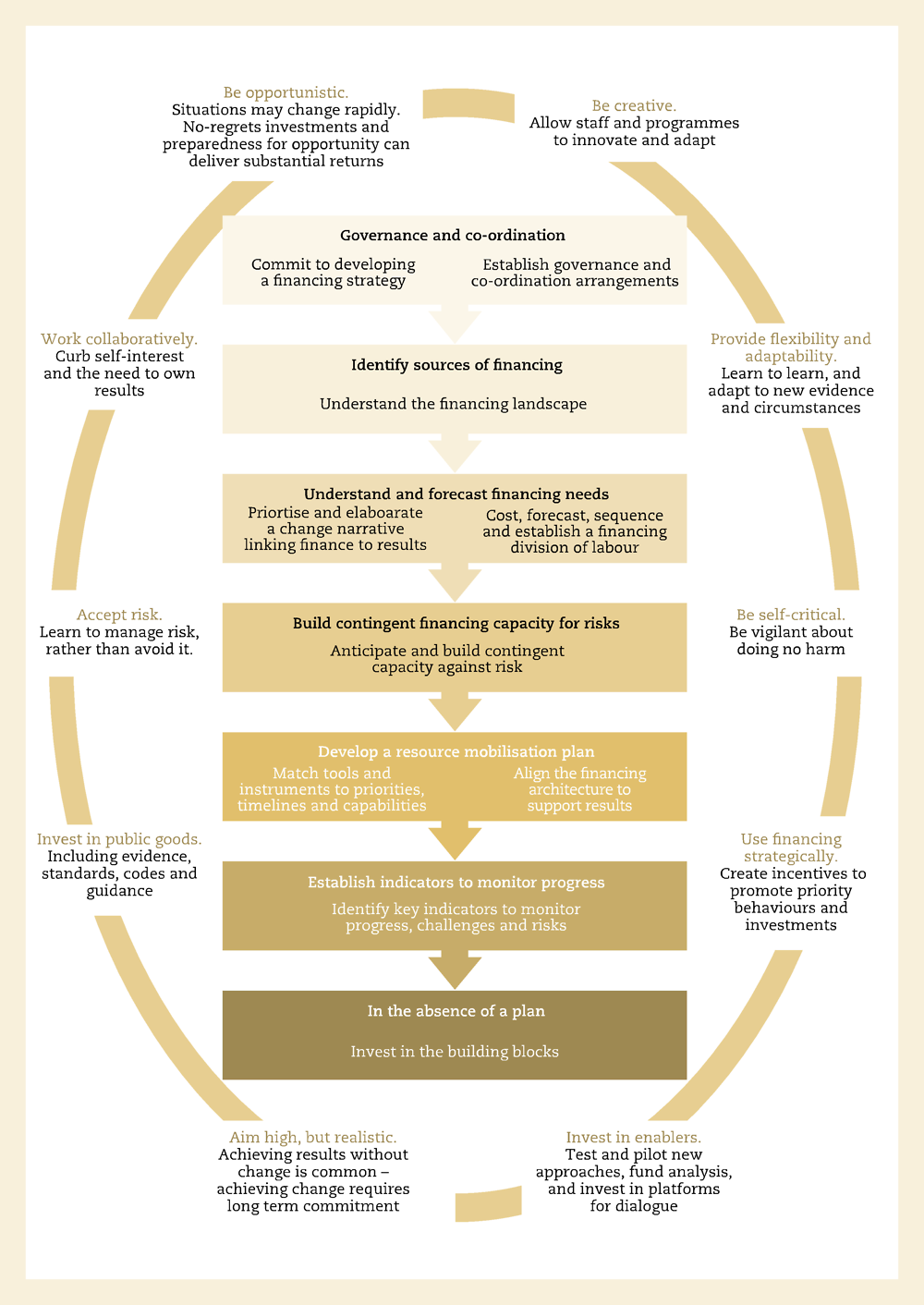

Indeed, there is neither a magic formula nor a one-size-fits-all solution for the right development financing in fragile contexts. Rather, financing strategies that are specifically tailored to each context are needed to get financing right in fragile situations. One tool that can help deliver these tailored strategies is the Financing for Stability Model of the International Network on Conflict and Fragility (INCAF) that is shown in Figure 9.1. This model helps development actors in different contexts build financing strategies that look beyond immediate financing gaps to the potential contributions of different financing actors and flows to stability, humanitarian, resilience and peacebuilding goals.

Such strategies provide the foundation for the right financing for fragile contexts. But formidable challenges remain to systematically delivering this financing. To overcome these will require increasing staffing capacity to help absorb additional funds and better programme in a landscape of increasingly diverse financial flows; enabling flexible, risk-tolerant financial tools; creating the right incentives for working collaboratively; and increasing financial literacy in the system (Poole, 2018[1]).

This chapter discusses additional challenges and successes related to ensuring the right financing for fragile situations.

9.1. The right amount of financing

9.1.1. Financing is highly context-specific

More financing does not automatically bring more peace. The 15 extremely fragile contexts in the OECD fragility framework, which are also the least peaceful contexts, already receive more official development assistance (ODA) than the other 43 fragile contexts put together: USD 31.1 billion compared to USD 27 billion in 2016.

Nor should it be assumed that fragile contexts with high levels of financial flows are getting the right amount of financing and that those with fewer financial resources are underfunded. While the international community uses financial appeals and programme budgets as proxies for need, in reality programming costs vary significantly across the different dimensions of fragility and from context to context. For example, and as highlighted in Chapter 5, programming to build social cohesion often will be significantly less expensive than large infrastructure projects to address economic fragility. ODA for Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goal (PSG) 4 (economic foundations and livelihoods) exceeded ODA for PSGs 1, 2 and 3 (legitimate politics, security and justice) – at USD 16.3 billion versus USD 4.54 billion in 2016. But this does not necessarily mean that there is too much funding for economic issues or too little for politics, security and justice.

Likewise, insecure environments also drive up programme costs. The World Food Programme, for instance, estimates that it could reduce costs by nearly USD 1 billion each year if humanitarian access in such environments improved (WFP, 2017[3]). This serves to demonstrate further that the right amount of financing is highly context specific.

9.1.2. The right mix and match of different development financing flows will help to maximise their value in each fragile context

There are ways to get more value and impact from the various flows of finance in fragile contexts. Rather than focusing on increasing the amount of those flows, or by seeking to change how they are targeted, additional value can be created through synergies: through seeking to understand how the range of different flows are actually being used and also by helping the different flows – public, private, domestic and international – to become complementary and coherent. This will help reinforce the collective impact of all development financing flows on stability and resilience in individual fragile contexts.

Synergies also enable flows such as Islamic social finance, remittances, private flows, ODA and investments from non-traditional donors to become part of a coherent overall financing landscape in different contexts.

Islamic social finance, in particular, is increasingly cited as an important solution for fragility.1 This takes a number of forms. The Islamic Development Bank is investing in a range of fragile contexts (IDB, 2017[4]). It also is a part of the Global Concessional Financing Facility,2 which is supported by a number of international organisations and provides development support on concessional terms to middle-income countries affected by refugee crises. Another source of such financing is zakat, the mandatory Muslim practice of giving 2.5% of one’s accumulated wealth for charitable purposes every year. Globally, zakat is estimated to amount to tens of billions of dollars annually, with between 23% and 57% of the total zakat used for humanitarian assistance (Stirk, 2015[5]). In Sudan, for instance, zakat is mandatory, regulated and used predominantly for social safety nets.3

Remittances represent another important flow whose impact can be maximised in the right mix, as discussed in Chapter 6. Fragile contexts received USD 111 billion in remittances in 2016. These flows primarily supplement the incomes of poor households on a regular basis and in times of shock, with the effect of increasing aggregate demand and thus employment and livelihoods (Ratha et al., 2011, p. 60[6]). However, remittances can also lead to negative economic drivers, for instance when they are used for purchasing imported goods, as has been seen in Haiti (INCAF, forthcoming[7]).

Private financing must also play a part in better financing in fragile contexts. However, as noted in Chapter 6, fragile contexts are difficult environments in which to mobilise and attract external private financing. On a practical level, high levels of risk and volatility and a shortage of partners and viable investment projects act to limit investment opportunities (Leo, Ramachandran and Thuotte, 2012[8]). Infrastructure constraints, inefficient business regulation procedures and low levels of skilled domestic labour also make the cost of doing business relatively high, which is another constraint on private finance. Therefore, in fragile contexts, there is a strong argument for focusing development finance on broader and longer-term public investments and macroeconomic reforms; supporting the development of pipelines of investable projects; and strengthening the investment-enabling environment before attempting to crowd in private funds (Poole, 2018[1]).

All of the above types of financing flows form an integral part of the development landscape. It may be difficult to influence the size of these flows, how they are spent and where they have development impact. Nevertheless, it is essential to ensure coherence among the different flows as much as possible. In this way, their collective value for development outcomes in fragile contexts can be maximised.

9.1.3. Investments in security can also catalyse greater value from development flows

Improved security can also help increase financing flows by enabling and stimulating economic growth and livelihoods and by improving domestic resource (tax) mobilisation, as described in Chapter 7. The 2017 Revenue Statistics in Africa report, which compiles fiscal statistics in 16 African countries, finds that the average tax-to-GDP ratio in these countries was 19.1% in 2015, but was much lower in the fragile contexts in this group – for example, 10.8% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (OECD/ATAF/AUC, 2017[9]).

Investments in reducing insecurity in fragile contexts can also lower costs in fragile contexts by reducing needs as well as the cost of implementing programmes.

Demonstrating the key role that investments in security play in promoting development and stability, and to help to ensure there is the right amount of financing for fragile contexts, a greater percentage of peacekeeping expenditure is now being counted as ODA. The co-efficient was increased to 15% from 7% as of 2016 data.4

9.1.4. Climate financing is hard to mobilise for fragile contexts

Climate financing should also contribute to the overall mix of flows to fragile contexts, and help to grow the amount of finance, as many fragile contexts are also exposed to climate risks. In 2016, the OECD fragility framework recognised the environmental dimension of fragility for the first time. This report finds that 51 of the 58 countries in the 2018 framework are severely or highly fragile on the environmental dimension. Yet climate financing is extremely difficult to obtain in fragile contexts, in part because these instruments require tangible results in short timeframes, which are difficult in a complicated environment.

9.1.5. Fragile contexts attract many bilateral partners but few of them are significant

The right amount of financing also requires development partners to make significant and not just token investments. In addition, dependence on one or two main partners can leave fragile societies overly exposed to shifts in aid policy.

Bilateral donors have many different reasons and criteria for investing in fragile situations. The criteria are usually a mix of quantitative and qualitative measures based on needs, such as poverty measures and the presence of humanitarian crises; historical ties, commercial and geopolitical interests; and regional and global public goods that often including those related to migration and violent extremism.

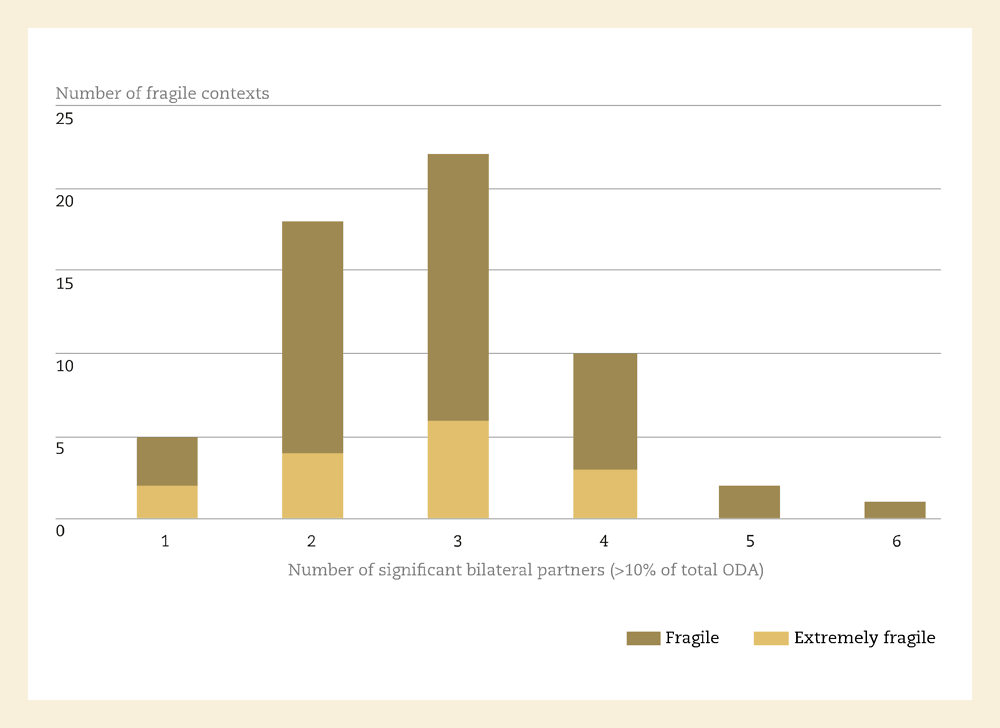

As a result, fragile situations not only have a broad range but also a large number of bilateral donors – on average 23. At one end of the spectrum, Afghanistan, Egypt, Syria, and the West Bank and Gaza Strip each had 30 bilateral donors in 2016. At the other end, Equatorial Guinea and Solomon Islands each had 11 donors in 2016. These numbers do not tell the full story, however. Most fragile contexts actually have only two or three significant bilateral donors, that is, donors who represent over 10% of the total ODA disbursed in that context (Figure 9.2). This means that ODA spent in fragile contexts is often concentrated in the hands of a small number of donors, among them usually European Union institutions and the United States. It also means that the remainder of the ODA can be highly fragmented. Fragmentation makes donor co-ordination challenging, while over-reliance on two major donors leaves fragile situations excessively exposed to shifts in individual agency aid policy.

9.2. The right financial tools

9.2.1. Financial tools vary significantly from context to context and over time

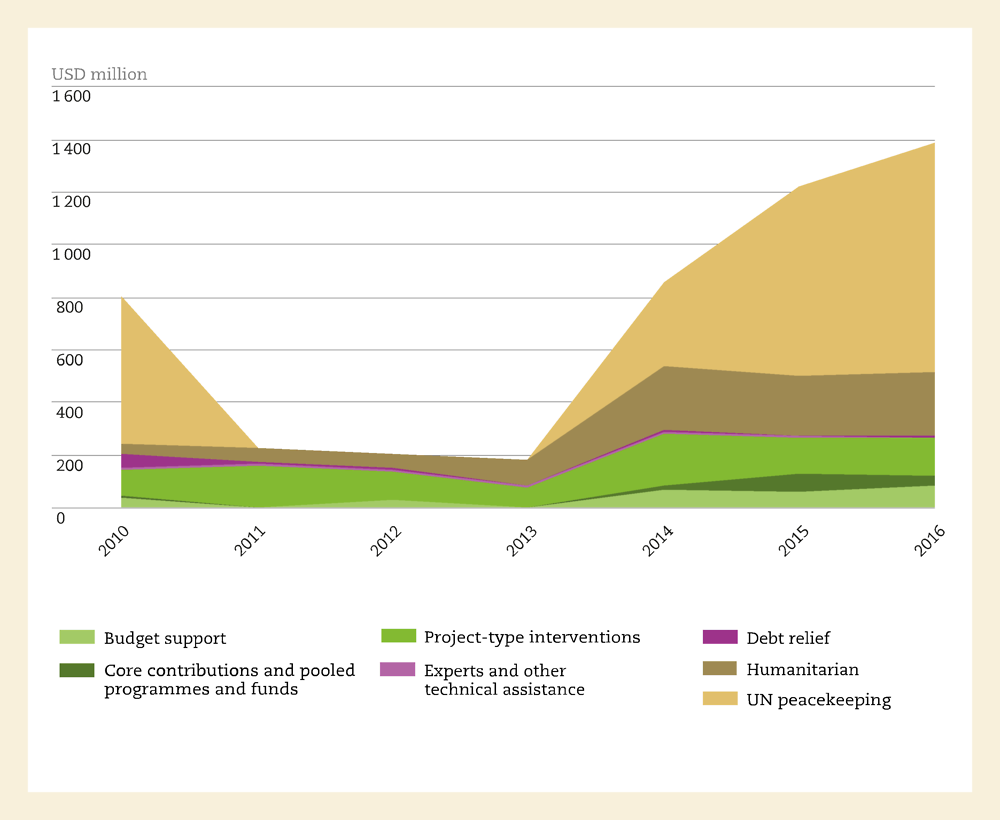

A comparative analysis of different ODA tools and peacekeeping flows shows that the types of aid used can vary significantly over time and among different contexts. The reason for this variation often relates to the particular bilateral donors who are investing in a particular context and to the tools they have in their own toolboxes, rather than to proactive decisions about which financing tools are the most appropriate for each context.

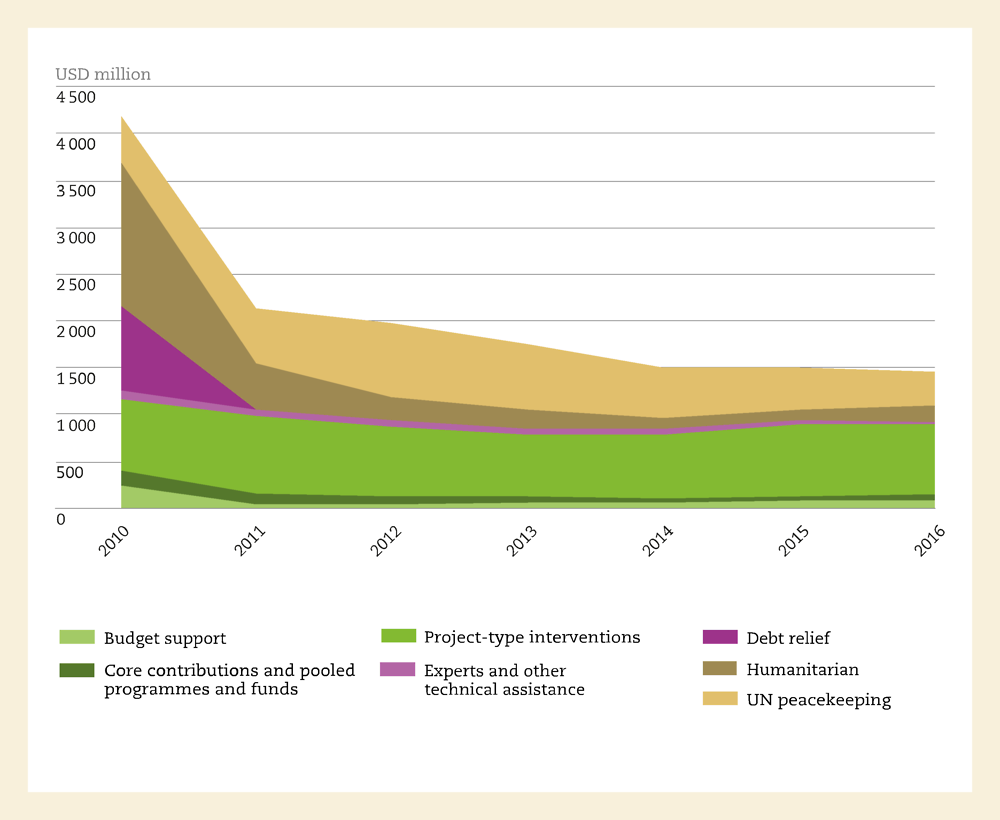

Haiti, an extremely fragile context without active conflict, has seen significant shifts in the types of aid offered over the last seven years (Figure 9.3). ODA to Haiti spiked in 2010, when humanitarian aid poured into the country in response to the earthquake that devastated much of the country. By 2012, these humanitarian flows had tapered off almost completely. The volume of development investments also increased in 2010, remaining fairly constant out to 2016. However, rather than focusing on building capacity – which might be expected in a recovery situation without conflict – these flows remain largely project-type interventions. Technical assistance, which can be used to build capacity, has decreased over the post-earthquake period to USD 27.5 million in 2016 from USD 75.6 million in 2010. There will be another significant change in development finance flows when the peacekeeping mission (MINUJUSTH) transitions from a peacekeeping to development role.

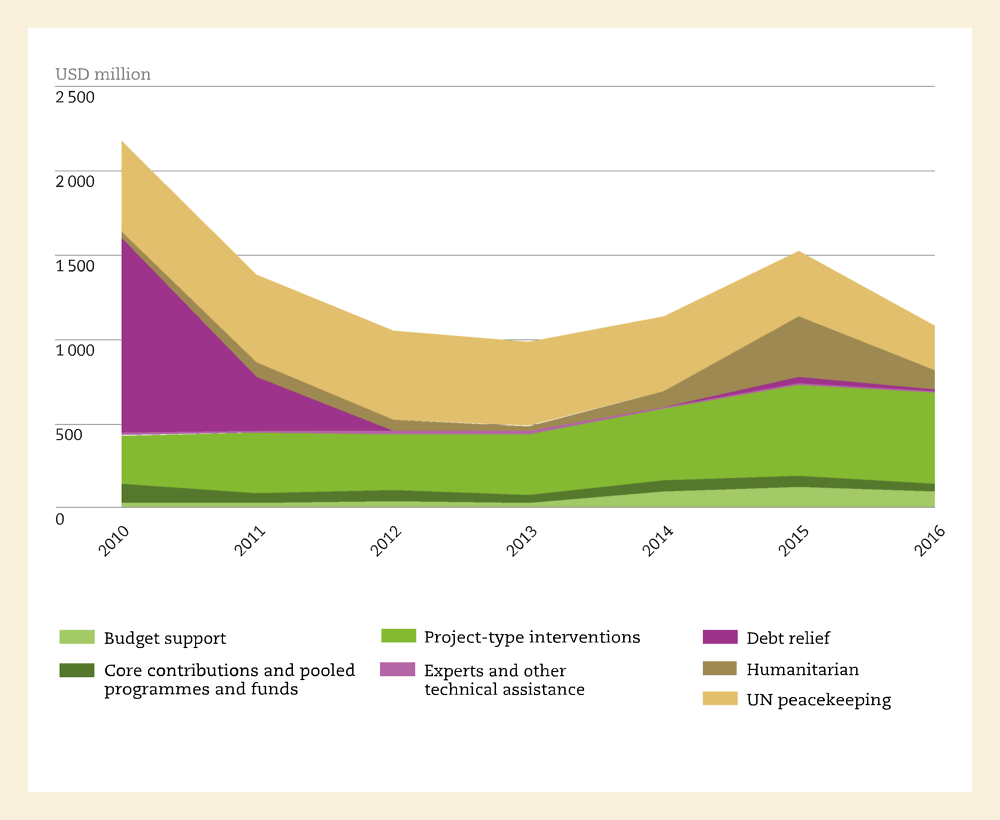

Liberia, another post-crisis context, saw a significant spike in overall ODA in 2015 due to a massive influx in humanitarian assistance for the Ebola crisis (Figure 9.4). This was accompanied by an uptick in development assistance, largely in the form of project-type interventions that have grown by nearly 2 000%, to USD 545.6 million in 2016 from USD 28 million in 2007. It appears that in the Liberia context, as is the case in some other contexts, rapid growth in development programming is easier to accomplish through project-type interventions than by using other modalities.

The Central African Republic, an extremely fragile context with an active conflict situation, has seen humanitarian assistance dominate the ODA landscape since 2012 (Figure 9.5). In 2016, humanitarian assistance, at USD 246.9 million, was almost equal to ODA delivered using development assistance tools. While this may be appropriate for a context experiencing significant conflict, it is noteworthy that even in this very challenging environment, budget support – all from France – represented a significant part of the development support to Central African Republic, or 16.7% in 2016. This is in contrast to Haiti and Liberia, which potentially are more stable situations and where budget support was a very minor part of the development picture.

9.2.2. Contingent financing is often an afterthought at best

Fragile situations can evolve rapidly, either because of ongoing shocks or due to new opportunities. Yet development planning and prioritisation processes rarely plan for and build in financing capacity against risk. Risk financing instruments have been successfully applied to fragile situations, notably the African Risk Capacity sovereign disaster risk financing pool,5 which helps governments to make financial provision for disaster risks. However, neither national financial protection strategies nor contingent arrangements by development financers are systematic in fragile contexts.

In addition, readiness actions in anticipation of major new flows are also too rare. For example, sanctions on Sudan were lifted in 2017, so now would be the time for development actors to build absorption capacity and draw up initial plans in preparation for potential new financing, whether in the form of new private inflows, an eventual scale up of multilateral bank investments or other flows. This could be done on a no-regrets basis, i.e. delivering useful development results even if the increase in development investments does not arrive in the short term (Poole and Scott, 2018[2]).

9.2.3. Pooled funds should complement and not substitute for other instruments

The popularity of pooling funds from multiple donors into a single instrument, a multi-partner trust or pooled fund has peaked and ebbed over the last decade, including in fragile contexts. As of April 2018, there were 66 pooled funds operating in 37 fragile contexts, with total approved budgets of USD 247.7 million, representing 71.6% of the total approved budgets for all United Nations (UN) pooled funds (UN Development Group, 2018[13]). As noted in a recent discussion paper (UN Development Group, 2016[14]), pooled funds can help improve risk management for individual development partners, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected contexts. However, they should complement rather than substitute for agency-specific instruments and more thought needs to be given to maximising their comparative advantage. Therefore, a review of the individual pooled mechanisms in fragile contexts would be useful to ensure they are playing a catalytic and coherent role and are operating to maximum efficiency. In Sudan, for example, there is significant potential to harmonise and align the work of the four pooled instruments, with many benefits in terms of information sharing on partner performance and results, aligning goals, and clarifying division of labour (INCAF, 2017[15]).

9.2.4. The missing middle is hampering investment in public goods

The quest for value for money and reduced administrative burden has led to what has come to be widely called a “missing middle” where middle-sized projects can no longer attract financing. Preliminary research conducted by the OECD found that a large grouping of projects range in size from around USD 1 000 to USD 30 000. These tend to be small-scale projects with limited scope for broader impact and with high administrative burdens relative to the amount of funding received. The next grouping of projects starts at USD 2 million for bilateral donors and at USD 10 million for multilateral donors.

Programmes with budgets in the missing middle, between these groupings, face more complicated funding challenges. These can include projects of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that are targeted at soft areas such as social cohesion, for instance. To deal with these challenges, some UN agencies report that they bundle projects to make sure that they are sufficiently substantial to interest a donor. But only development actors with sizeable absorption capacity are able to use this tactic. Given the importance of the softer social and political dimensions of fragility, it will be important to overcome the missing middle challenge.

The push to deliver results in country also has led to a shift of the budget envelopes of OECD members towards country programmes, with only minor funding left over for policy areas and global public goods. As a result, a number of global inter-agency initiatives have been left in financial difficulty. This has been the case particularly in the risk management community, with global partnerships such as the Capacity for Disaster Reduction Initiative (CADRI), the INFORM Index for Risk Management and the Global Preparedness Partnership all experiencing difficulties in raising predictable financing.

9.2.5. Technical assistance is inadequate

It is widely recognised that fragile situations are characterised by weak capacity to deliver basic services and weak capacity to carry out basic governance functions. However, investment in building capacity is very low and technical assistance has consistently made up only between 1% and 2% of ODA to fragile contexts since 2010 (OECD, n.d.[10]). In Haiti, for example, only USD 65.6 million was invested in technical assistance in 2016, despite the clear need for improved capacity in the technical ministries (INCAF, forthcoming[7]). If the international community is to make good on its New Deal promise to use and strengthen country systems, there will need to be greater investment in technical assistance.

9.2.6. Mobilising financing for decentralisation is also complicated

Mobilising financing for sub-national institutions and domestic resource mobilisation at the sub-national level in fragile contexts also can be complicated, leaving such institutions often chronically underfunded despite recognition that pockets of fragility often exist at the sub-national level. This situation is further complicated by what are often low levels of absorption capacity at the sub-national level. For example, in Madagascar, the Local Development Fund, a donor-supported initiative housed in the Ministry of Interior, provides funds to local authorities based on objective criteria. But in practice, and mostly due to lack of absorption capacity at local level, the sums transferred are very small, often in the range of USD 500 to USD 5 000.

9.2.7. Care is required before making new loans to fragile contexts

Many fragile contexts have issues with debt sustainability. This means that their borrowing strategies and international community lending strategies need to take care to limit the associated risk of debt distress. Levels of indebtedness in most fragile contexts are increasing; their average debt-to-GDP ratio has risen steadily to a projected 50.5% in 2017, up from 37.5% in 2012.6 Higher levels of indebtedness intensify the borrowers’ exposure to market risks and create challenges for debt resolution, especially when debt is secured on commercial terms from non-commercial sources (IMF, 2018[16]).

Five fragile contexts – Chad, Gambia, South Sudan, Sudan and Zimbabwe – are already in debt distress, meaning they are already having difficulties in servicing their external debt.7 To counter the risk of debt distress, factors such as the likelihood of conflict and other shocks and the existing debt burden should be factored into lending and borrowing decisions in fragile contexts, as such factors will create economic disruptions and a loss in resilience that can hamper long-term growth prospects and affect debt sustainability.

9.2.8. Development financing wherever possible and humanitarian financing only when necessary

Humanitarian financing makes up a major proportion of total ODA in fragile contexts and so must be actively factored into development financing strategies. In 2016, humanitarian financing constituted 25% of ODA to fragile contexts, or USD 18.3 billion (Chapter 4). In the run-up to the 2015 World Humanitarian Summit, policy makers focused on improving the quality and efficient use of humanitarian financing, resulting in agreements such as the Grand Bargain.8 However, there is broad agreement that the humanitarian system, which experienced a shortfall in funding of an estimated 40% in 2016, is badly overstretched (Development Initiatives, 2017[17]).

A major policy push is under way for greater coherence among development, humanitarian and peace actors. It is driven by recognition that longer-term development approaches addressing underlying vulnerability, in combination with necessary life-saving humanitarian interventions, help to build resilience to future shocks and to minimise the impact of current crises. In consequence, they are more impactful than emergency relief alone. In fragile contexts especially, the international community should thus adopt the overarching principle of development programming and financing wherever possible and humanitarian assistance only when necessary.

9.3. Financing at the right time

9.3.1. Programming should be phased and sequenced to match the timing of financial flows

Different types of financial flows are transferred, realised or disbursed over different periods of time, whether they are public, private, domestic or international. ODA is disbursed in accordance with an individual donor’s financial year or conditions attached to particular grants. Domestic budget allocations are made in line with the budgetary cycle. Remittances may peak at certain times of the year, and people’s livelihoods – especially of those who make up the informal economy – will vary across the year, dependent on factors like agricultural cycles. Programme planning should take into account the timing of these different flows and attempt to match expenditure and investments as closely as possible to the different inflows of financing over the year.

Another key factor in getting the timing right is forecasting the intended contribution and trajectory of domestic and international public and private financing sources, noting that the predictability of forward estimates can vary enormously (Poole and Scott, 2018[2]). This type of forecasting allows programming to be matched to changes in the financing landscape. For example, Haiti has ambitions to become an emerging economy by 2030. To realise this ambition, Haiti will need to reduce its reliance on external financial flows such as ODA and instead step up domestic resource mobilisation, customs duty collection and other revenue-generating activities. Programming could thus be tailored to ensure that, in the short term, ODA flows build resilience to disasters, catalyse growth, increase capacity for tax collection and strengthen public financial management; in the longer term, Haiti’s development will be driven from tax revenues and ODA may play only a niche role (INCAF, forthcoming[7]).

9.4. Financing that creates the right incentives for stability

9.4.1. Financing that promotes peace and does no harm

Financing should be designed to help provide the right incentives for sustained peace. As Jenks and Topping (2017[18]) note, there are a number of ways that this can happen:

-

Strategies that include a financing strategy can help overcome or reduce competition for resources from the initial planning stages.

-

The way financing is structured and targeted can help to ensure that a response moves beyond care and maintenance efforts to also deliver sustainable peace outcomes.

-

Financial flows can help to bring sensitive topics to the table and create pressure for their resolution, for example by making future funds flows contingent on ensuring refugee rights or free and fair elections.

-

Greater financing for local actors can change the way that societies are involved in their own future, while greater transparency in financing can help create local demand for better outcomes.

-

Facilitating the collection of domestic tax revenue and its investment in basic services and good governance can help support the state-society contract.

-

Financial flows direct to municipalities can help ensure that sustainable peace is also an objective in fast-growing, fragile cities.

-

Financing should be designed to guard against disincentives, which means continuing to finance places that are showing a good track record towards peace.

9.4.2. Mutual accountability frameworks

Ensuring that financing is right, and that the right incentives are in place, does not stop at the planning process. It must continue through the life of the programme cycle and be based on a mutually agreed set of strategic indicators that are monitored both through peer pressure and domestic accountability.

Mutual accountability frameworks can be powerful tools. They can ensure that all aspects of development financing are working towards coherent results and provide a useful set of incentives to ensure that all actors are living up to their commitments – financial and otherwise – to improve stability (Box 9.1).

Successful mutual accountability frameworks include the following features:

-

Partner government leadership

-

Efforts to strengthen national capacity for ownership and leadership

-

Strong domestic accountability by including domestic stakeholders

-

Donor “peer pressure” aspects

-

Built on existing mechanisms where possible, such as existing co-ordination structures

-

Can be sector-based or at sub-national level, not just at national level

-

Use independent monitoring and evidence where possible

-

Start small and grow over time

-

Transparent

-

As practical and simple as possible to make it more inclusive and workable

Source: (OECD DAC Task Team on Mutual Accountability, n.d.[19]), “10 tips on mutual accountability”, www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/49656297.pdf.

9.4.3. Financing tools and practices can help to incentivise inclusive growth

How financing is used to catalyse and underwrite economic growth in a fragile context is critical to ensuring that growth is inclusive and therefore contributes to promoting sustainable peace. Inclusive growth is economic growth that creates opportunity for all segments of the population and distributes the dividends of increased prosperity fairly across society, both in monetary and non-monetary terms.

Addressing structural disincentives to doing business can be a good way for ODA to catalyse private sector growth. This is equally true for structural disincentives to attracting foreign investment and growing the domestic private sector. Fragile economies made up 79% of the bottom quarter of the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index in 2017 (World Bank, 2017[20]). Each context may feature distinct opportunities for promoting inclusive economic growth, as can be seen in the discussion of opportunities in Central African Republic in Box 9.2.

Changes in the way ODA operates could help to support inclusive growth in Central African Republic. Changes can include:

-

Ensuring that ODA projects subcontract to local enterprises and focus on building the governance and technical capacities of those enterprises

-

Rewriting licence agreements with major banking and telecommunications operators so that they extend operations outside of Bangui, the capital, and thus act as a catalyst for development elsewhere in the country

-

Providing financing for stimulating growth in the informal sector

-

Promoting the return of displaced people to stimulate the agricultural sector

-

Investing in energy production, infrastructure and education, as deficits in these areas significantly constrain economic growth

-

Increasing investor confidence by investing in security and improving the ease of doing business

Source: (INCAF, 2017[21]), “Central African Republic: Accelerated Recovery Framework – Towards a financing strategy”, www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/docs/Financing_for_ Stability_CAR_en.pdf.

Getting the financing right in a fragile context is a complex task. It requires a financing strategy that mixes and matches a range of public, private, domestic and international flows to promote peace. Development financing should be used wherever and whenever possible and humanitarian financing only when necessary. People with the right skills are needed to help develop effective financial portfolios and manage the myriad of financial instruments and flows that are required to deliver the right financial solution for each fragile situation. Investment in building financial skills capacity and in providing expert technical support will thus be critical for success. It is also important to invest in demonstrating the added value of better financing so that good practices are shared and that new and innovative models of financing are scaled up and transferred to other contexts. Success breeds success.

Only then will peace be financed the right way, with the right amount of financing, using the right financial tools, for the right length of time and in a way that delivers the right incentives for peace and, by extension, for sustainable development in the world’s most complex and difficult operating environments.

References

[17] Development Initiatives (2017), Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2017 - Executive Summary, http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GHA-Report-2017-Executive-summary.pdf.

[4] IDB (2017), IDB's Support for Fragile and Conflict-Affected States, Islamic Development Bank, http://www.idbgbf.org/portal/detailed.aspx?id=883 (accessed on 07 May 2018).

[16] IMF (2018), “Macroeconomic developments and prospects in low-income developing countries - 2018”, Policy Papers, International Monetary Fund (IMF), http://www.imf.org/external/pp/ppindex.aspx.

[21] INCAF (2017), Central African Republic: Accelerated Recovery Framework - Towards a financing strategy, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/docs/Financing_for_Stability_CAR_en.pdf..

[15] INCAF (2017), From Funding to Financing: Financing Strategy Mission Report - Sudan, May 2017, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/docs/funding_to_financing_sudan.pdf.

[7] INCAF (forthcoming), Towards a Financing Strategy for Haiti, OECD, Paris.

[18] Jenks, B. and J. Topping (2017), Financing the UN Development System: Pathways to Reposition for Agenda 2030, Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, http://www.daghammarskjold.se/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Financing-Report-2017_Interactive.pdf.

[8] Leo, B., V. Ramachandran and R. Thuotte (2012), Supporting Private Business Growth in African Fragile States: A Guiding Framework for the World Bank Group in South Sudan and Other Nations, Center for Global Development, https://www.cgdev.org/files/1426061_file_Leo_Ramachandran_Thuotte_fragile_states_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 07 May 2018).

[10] OECD (n.d.), “Creditor Reporting System”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1. (accessed on 15 May 2018)

[19] OECD DAC Task Team on Mutual Accountability (n.d.), “Ten tips on mutual accountability”, http://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/49656297.pdf.

[9] OECD/ATAF/AUC (2017), Revenue Statistics in Africa 2017, OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264280854-en-fr.

[1] Poole, L. (2018), “Financing for stability in the post-2015 era”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 10, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c4193fef-en.

[2] Poole, L. and R. Scott (2018), “Financing for stability: Guidance for practitioners”, OECD Development Policy Papers, No. 11, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f3c7f33-en.

[6] Ratha, D. et al. (2011), Leveraging Migration for Africa. Remittances, Skills, and Investments, World Bank, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTDECPROSPECTS/Resources/476882-1157133580628/AfricaStudyEntireBook.pdf.

[5] Stirk, C. (2015), “An act of faith: Humanitarian financing and zakat”, Briefing Paper, Development Initiatives, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EMBARGOED%2026_03_2015%20Zakat_report_V9a.pdf.

[22] UN (2015), Implementation of General Assembly resolutions - Report of the Secretary-General (A/70/331), United Nations General Assembly, http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/331/Add.1.

[12] UN (n.d.), UN Peacekeeping Fact Sheets, 2013-2017, United Nations, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/how-we-are-funded (accessed on 25 May 2018).

[11] UN (n.d.), Year in Review, 2006-2012, United Nations, https://shop.un.org/series/year-review-united-nations-peace-operations (accessed on 25 May 2018).

[13] UN Development Group (2018), Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office Gateaway, http://mptf.undp.org/. (accessed on 15 May 2018)

[14] UN Development Group (2016), “The role of UN pooled financing mechanisms to deliver the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda”, Discussion Paper, United Nations Development Group, https://www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/qcpr/undg-paper-on-pooled-financing-for-agenda-2030.pdf.

[3] WFP (2017), World Food Assistance 2017: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead, World Food Programme (WFP), https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000019564/download/?_ga=2.159725242.605904495.1522418679-1250376136.1522418679.

[20] World Bank (2017), Doing Business 2017: Equal Opportunity for All, World Bank, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0948-4.

Notes

← 1. See, for example, comments by global experts cited by the Islamic Development Bank in March 2016, at www.isdb-pilot.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/En.PAP-Press-12.03.2016-V2.pdf.

← 2. Further information on the Global Concessional Financing Facility is at https://globalcff.org/about-us/.

← 3. Sudan’s laws make zakat mandatory. The government-run Zakat Chamber, established in 1990 and operating under the auspices of the Ministry of Social Welfare, is responsible for its distribution. A 2% zakat tax is automatically deducted from the salaries of people who earn more than USD 1 500 per month and the Sudanese government also makes significant contributions to the Zakat Fund. In 2011-12, a total of 700 million Sudanese pounds (about USD 105 million) was collected. Beneficiaries include disabled people, refugees, poor students, the homeless, orphans, mentally ill people, people with health problems, and those deemed the poorest of the poor. Sudan’s government also provides these groups with free health insurance.

← 4. For more information, see https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/ODA-Coefficient-for-UN-Peacekeeping-Operations.pdf.

← 5. See www.africanriskcapacity.org for more information on African Risk Capacity.

← 6. The IMF directly supplied data on indebtedness, which were then analysed using the OECD fragility framework results. Indebtedness data for 2017 are projected. No data are available for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Libya, Somalia, Swaziland, Syria, Timor-Leste, and West Bank and Gaza Strip.

← 7. The International Monetary Fund provided these data to the authors.

← 8. For more details on the Grand Bargain, see https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain-hosted-iasc.