Chapter 1. Overview: Meeting Paraguay’s development ambition

Paraguay has performed well in a range of development outcomes since 2003. The country has set out an ambitious development vision with the horizon of 2030 and a National Development Plan to meet that ambition. Challenges remain to sustain economic performance, increase the inclusivity of the country’s development pattern and buttress the process of institutional development. The objective of the Multi-dimensional Country Review (MDCR) is to support Paraguay in achieving its development objectives. The first volume identifies the key constraints to development in the country. This chapter presents the country’s development performance from a comparative and historical perspective, assesses performance across a range of well-being outcomes and, on the basis of the main results of the volume, identifies the key constraints to development in the country.

Paraguay has performed well in a range of development outcomes in recent years although major challenges lie ahead to meet the country’s ambitious development vision. Economic growth in the country has outpaced that of the region, driven by the tailwinds of rising export prices. Its proceeds have contributed to a large reduction in poverty. Well-being outcomes have improved notably in some areas, such as access to health or educational attainment. Challenges remain to sustain economic performance, increase the inclusivity of the country’s development pattern, and buttress the process of institutional development that has followed the democratic transition.

The Multi-dimensional Country Review (MDCR) of Paraguay is undertaken to support the country in achieving its development objectives. The MDCR is a process implemented in three phases, each leading to the production of a report. This first volume of the MDCR of Paraguay aims to identify the binding constraints to achieving sustainable and equitable improvements in well-being and economic growth. The second phase will further analyse the key constraints identified in order to formulate policy recommendations that can be integrated into Paraguay’s development strategy. The third and final phase of the MDCR will provide support to the implementation of these recommendations.

This overview chapter analyses the performance of Paraguay across key well-being dimensions and brings together the results of the thematic chapters to identify the key constraints to development in the country. First, it presents briefly the historical and structural context of Paraguay’s development path, and describes the country’s development vision as set out in its National Development Plan (PND). Second, the chapter analyses the country’s performance across a range of well-being indicators. Third, it summarises the assessments contained in the five thematic chapters. Finally, it concludes by summarising the main constraints to development in Paraguay.

Paraguay’s recent development performance

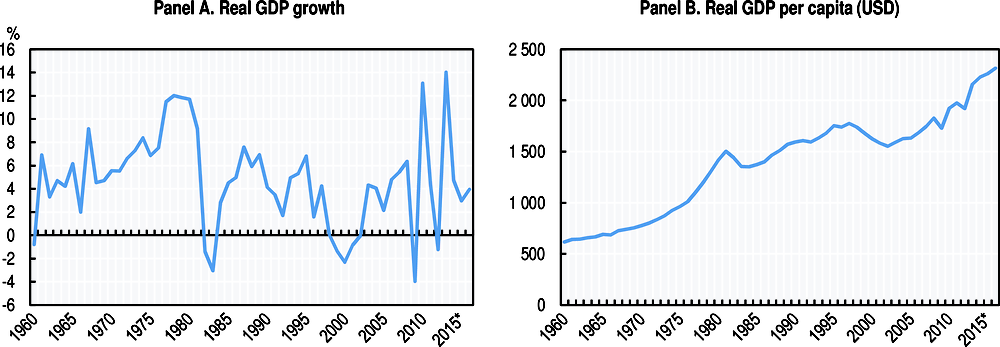

Since 2003 Paraguay has performed well in a range of development outcomes. Economic growth was mediocre throughout the 1990s and the economy suffered a long crisis in the early 2000s but after recovering in 2003 real gross domestic product (GDP) has grown at 4.6% per annum and, although it has slowed since 2013, the economy grew 4.0% in 2016 in the face of negative growth in the Latin American region. The proportion of the population in poverty has fallen substantially, from 58% in 2002 to 27% in 2015. The economy has become increasingly interconnected with the rest of the world and labour productivity has grown fairly rapidly, at 3.8% on average since 2004.

The recent period is a break from the economic history of the country since the middle of the 20th century. Following the civil war of 1947, and the fall in demand for agricultural commodities, the country’s economy slowed and fell behind its neighbours (Figure 1.1).1 The economy awoke from its slumber with the massive investment in the construction of the Itaipú dam, one of the largest hydroelectric power plants in the world, shared by Brazil and Paraguay, between 1973 and 1982, and the expansion of the agricultural frontier during the 1970s, resulting in average growth of 8.8%, including 20% growth in the construction sector. However, the economy returned to slow growth after the Itaipú boom, suffering from the Latin American “lost decade” in the 1980s and from political and economic instability from the democratic transition in 1989 until the crisis of the early 2000s (Arce, Krauer and Ovando, 2011; Fernández Valdovinos and Monge Naranjo, 2004).

Development in the country since 2003 has benefitted from favourable external and internal contexts. On the external front, the prices of key export products soared. The prices for soybeans and soybean oil more than tripled and the price of beef more than doubled between 2001 and the early 2010s and have remained at historically high levels despite a sharp fall in 2014. On the domestic front, Paraguay is in the midst of a long demographic transition and 28% of its population is young (15 to 29 years old). The low unemployment rate offers great potential for a demographic dividend to be reaped in the form of increased growth and economic dynamism.

Reforms undertaken since the democratic transition, and intensified during the most recent period, have contributed to the country’s capacity to benefit from a favourable external environment. Although they did not deliver a growth acceleration during the 1990s, key macroeconomic reforms undertaken during the decade set the stage for an improvement in macroeconomic management and introduced the essential building blocks of the country’s development model as it is today. Among the fundamental reforms in the 1990s were the unification of the exchange rate, a simplified tax code with greater emphasis on indirect taxation, fiscal adjustment and reform to public finances, and the joining of MERCOSUR common market created in 1991.

Continuing reforms have buttressed macroeconomic stability as one of the key features of the Paraguayan economy. An inflation-targeting regime with an explicit target since 2011 has succeeded in progressively lowering inflation and its volatility. Public sector external debt is very low at 23% of GDP (at the end of 2016), and the fiscal framework is sound. A fiscal responsibility law passed in 2013 limits the public deficit to 1.5% of GDP, even though the first years of its implementation have been challenging (see Chapter 2).

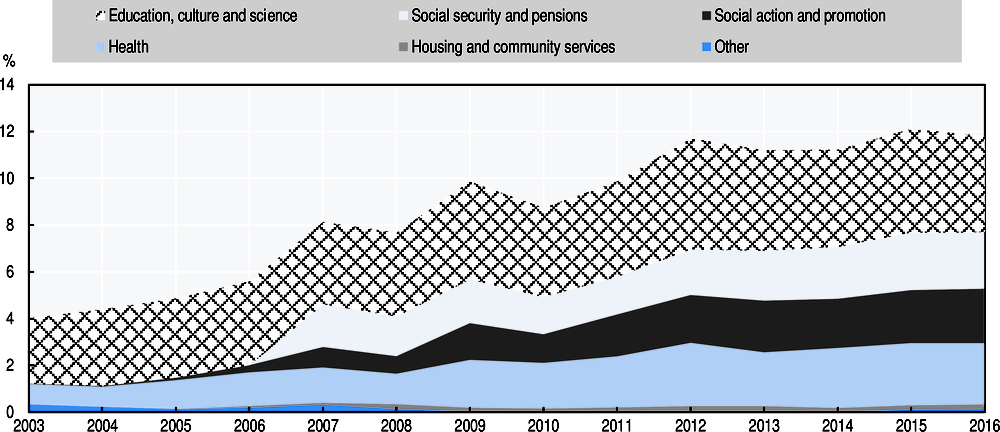

Priorities for government action have also shifted since 2003, with notable increases in public expenditure in social areas and on infrastructure. Paraguay does not produce reports or consolidated statements of public social expenditure for the whole of the public sector (it does report social expenditure for the central administration), nor are the domains that official figures classify as social comparable to those of OECD data. Nevertheless, available evidence shows an increase of social expenditure from 4.0% to 11.8% of GDP between 2003 and 2016 (Figure 1.2). This figure excludes a doubling of expenditure by social security institutions (from 2.1% to 4.4% of GDP) and significant increases in expenditure by autonomous bodies.2 In practice, this led to a massive expansion in the coverage of the two main anti-poverty programmes. The conditional cash transfer Tekoporã increased in coverage from 4 000 families in 2005 to 77 000 in 2009 to 140 000 as of 2016. Similarly, the non-contributory social pension, which covered less than 1 000 beneficiaries in 2010, covered 168 000 at the end of 2016 (see Chapter 3). Public infrastructure spending has soared, especially since 2011, doubling in nominal terms, and placing Paraguay above most countries in the region in terms of infrastructure investment as a share of GDP (see Chapter 2).

Beyond its geographical position, in the heart of South America and without direct access to the sea, Paraguay’s current and future growth path depends on a number of structural factors. Among them the most determinant are the importance of agriculture and animal husbandry in the country’s economy and society, the territorial distribution of the population and the on-going demographic transition, and Paraguay’s position as a major hydroelectricity producer.

Economy and society in Paraguay are characterised by the size of agriculture in the country’s economy. The share of the primary sector in the economy has remained relatively stable and large since the 1970s, with decade averages of between 24% and 28% of GDP. It even increased in the first decade of the 2000s with the increase in commodity prices before falling back in the first half of the 2010s with the fall in prices (Chapter 2). The contribution of livestock has increased in the past 25 years from 3.3% of GDP to 5.9% in 2016, while agriculture contributed 11.4% of GDP in 2016 (at current prices). Even these figures under-represent the importance of agriculture and animal husbandry in the country. Indeed, agro-industry also accounts for more than half of manufacturing value added, as well as significant shares of transport and service output. The agro-industrial value chain is estimated to generate 28.9% of GDP (Investor, 2015), and Masi (2014) estimates that in the boom year of 2013, agro-industry contributed 57% of GDP growth. This explains why the variability in agricultural output, largely driven by weather conditions, has an impact on the economy over and above its direct contribution to GDP.

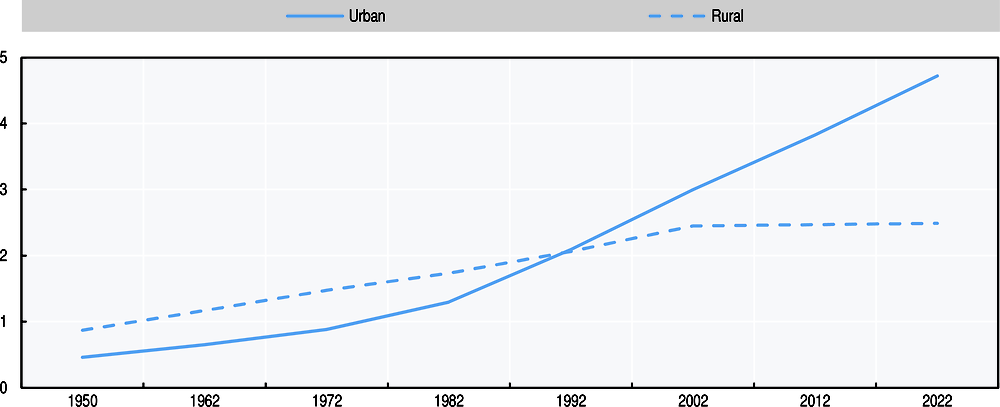

The territorial distribution of the population and its recent evolution are also major on-going changes. The colonial occupation of Paraguay was heavily concentrated in frontier areas focused on defence, and, in the early years of independence, port towns (Asunción and Concepción on the Paraguay river, Encarnación on the Paraná river). Since independence, the settlement of the country has progressed via largely agricultural colonisation and the development of border towns, of which Ciudad del Este is the largest. As a result, the rate of urbanisation has lagged behind that of other countries in the region, and reached 60% of the population in 2015. More than half of the urban population is concentrated in the metropolitan area of Asunción and another 13% in Ciudad del Este and its metropolitan area. Urbanisation has progressed rapidly since 1980, driven by increased migration from rural to urban areas. Since 2000 the combination of internal migration and falling fertility has led to a stagnating and ageing population in rural areas (Investor, 2015). The pattern of urbanisation is also changing. In the ten years between the 2002 and 2012 censuses, the rate of growth of greater Asunción (1.8% per annum) and Ciudad del Este (2.2%) was much slower than that of the rest of the urban areas (3.5%) in the country, signalling renewed dynamism among intermediary urban centres in Paraguay.

The ongoing demographic transition is a major opportunity for development. Paraguay is a very young country. According to official demographic projections, 28% of the population are aged between 15 and 29 and that indicator is currently at its maximum. The demographic transition is under way and is relatively slow. While gross death rates are projected to be at their minimum in 2017, birth rates are not projected to converge with death rates until well into the second half of the century. As a result young cohorts arriving into the labour market are large and will be in the years to come, offering opportunities for growth but also straining the capacity of the economy to provide good formal jobs to all.

Paraguay’s hydroelectric production capacity is also a major characteristic of the country’s economy. The two binational power plants, shared respectively with Brazil (Itaipú) and Argentina (Yacyretá), together house installed capacity of 17 200 megawatts (MW) which are shared between Paraguay and its neighbours. Since Paraguay only uses a fraction of its share of electricity, the rest is exported, making it the largest exporter of clean electricity in the world. The two binationals contribute about 10% to GDP. Royalties and compensations from the two dams also generate public revenues (11% of total public revenues in 2016 [Chapter 2]), of which a sizeable proportion is channelled to local governments and earmarked for capital expenditures and social infrastructure. Paraguay’s generation capacity also endows the country with spare capacity in low-cost electricity, a major asset for the attraction of foreign investment.

Paraguay’s development ambition: The National Development Plan

In 2014, Paraguay adopted its first National Development Plan (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo, PND) (Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, 2014). Entitled “Building the Paraguay of 2030” (Construyendo el Paraguay del 2030), the PND is an ambitious agenda for mid-term development with a 2030 horizon. The PND is directed along three strategic axes: (i) poverty reduction and social development; (ii) inclusive economic growth; and (iii) inserting Paraguay into the world. It follows four cross-cutting themes (equality of opportunity, efficient and transparent public management, territorial development and land management, and environmental sustainability). Together, these form 12 strategies with a monitoring framework based largely on numerical targets.

The PND is a strategic document, backed by a legislative framework and linked to the budget. It was adopted by presidential decree in December 2014. Article 177 of the 1992 constitution mandates that compliance with national development plans be obligatory for the public sector. Adherence to the PND is part of the guidelines for the development of budget proposals put forward by the Ministry of Finance. The planning authority (Secretaría Técnica de Planificación, STP) is responsible for the development of local and sectoral development plans adhering to the PND. The STP also plays a co-ordinating role with the Ministry of Finance, carried out through inter-agency working groups. Finally, the STP supports the implementation of the PND through the development of monitoring and planning tools. It has developed an outcome-based planning management tool in which budget proposals are linked to specific PND objectives and which also functions as a monitoring tool, collecting information on output delivery from implementing agencies.

Paraguay’s plan to achieve its vision for 2030 is ambitious. The objective of eradicating extreme poverty is within reach if the rate of poverty reduction achieved since the late 1990s is maintained, but this alone will require constant policy innovation to reach the poorest and increase their living standards. Achieving average GDP growth of 6.8% in the medium run will also be challenging in a more difficult external environment. Paraguay’s growth performance in the past ten years has been better than most comparator countries, but below that objective (Chapter 2). Some of the most ambitious objectives do not have numerical targets. For example, consolidating the network of transport while reducing costs and integrating the country with the rest of the world requires large infrastructure investments. The same is true for a number of objectives that will require significant progress in institutional development, such as achieving universal social security coverage or establishing land management and zoning plans in all municipalities.

The National Development Plan can contribute to policy continuity. The PND’s development was based on a wide consultation process with the central and local administrations, civil society and other stakeholders. It is supported by a national committee of citizens from the private sector, academia, and civil society, the Equipo Nacional de Estrategia País (ENEP). ENEP, with its wide representativity of Paraguayan society, acts as a guardian of the PND and follows its implementation. Given its long horizon and its institutional backing, the PND can contribute to avoiding policy reversals, by establishing long-term policy objectives that cut across line ministries and agencies.

The MDCR assists Paraguay in meeting its development goals

Development is inherently multi-dimensional and cannot be reduced to a single objective or indicator, even factors as determinant as economic growth or as socially relevant as poverty. The OECD’s MDCRs analyse development challenges from a wide variety of perspectives, using a combination of tools: a gap analysis across a dashboard of indicators, detailed cross-country benchmarking with a set of comparator countries, and a visioning exercise to identify priority outcomes for citizens in the country.

Following the adoption of Agenda 2030 by the United Nations as global development agenda (UN, 2015) and given the alignment of Paraguay’s PND with the objective framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, this report adopts the five areas of critical importance of Agenda 2030 as guiding themes for each chapter: prosperity, people, planet, peace and institutions, partnership and financing development.

To assess accurately Paraguay’s economic and social strengths and weaknesses, the MDCR goes beyond benchmarking them relative to averages and adopts a comparative approach with the help of a group of benchmarking countries, selected jointly by the team undertaking the review and Paraguay. The choice of these countries is based on factors such as income per capita, size, structural characteristics and the degree to which experiences from some of these countries could be useful models for policy development in Paraguay. The comparator countries selected are: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Israel, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Thailand, and Uruguay.

In addition to this quantitative dimension, the MDCR includes a series of participatory workshops. These workshops enable the OECD team to connect with diverse perspectives in the country and to bring together different elements of Paraguayan society to reflect on the challenges of development, as well as on the context in which policy responses will be implemented. They serve as a platform for dialogue and a means to test recommendations and ensure they are adapted to the context and are relevant. A multi-stakeholder workshop was organised in Asunción in March 2017 with participants from the public and private sectors and civil society (see Box 1.1).

As part of the OECD Multi-dimensional Country Review (MDCR) methodology, a series of workshops are organised throughout the review to connect with a diversity of perspectives of Paraguayan society and identify challenges and solutions to inclusive, sustainable development together with local stakeholders and experts. A first workshop entitled “Paraguay: Future, challenges and global environment” was organised in Asunción on 23 March 2017. The workshop was co-hosted by the Secretaría Técnica de Planificación (STP), and brought together over 40 participants from the public sector, the private sector, academia and civil society.

The workshop aimed to capture citizen aspirations for the future of their country, and discuss major obstacles to realising progress. The first session of the day focused on developing success stories of Paraguay in 2030, and capturing citizen normative preferences for the future (see Annex 1.A1). Participants were divided into groups and were asked to develop narratives from citizens’ perspectives of a Paraguay in 2030 where all policies had succeeded. Participants subsequently extracted the different categories in their stories, which were subsequently clustered into policy areas modelled on the OECD’s “How’s life” framework.

Participants’ stories described a whole range of different citizen profiles: men and women, young and old, some with graduate education and others not having completed high school education, some in high skilled professions like engineers and others in manual labour, some from Asunción and others from different regions, including indigenous groups. All fictional citizens enjoyed middle class family lives, with stable decent work based on existing industries, leisure time, good health and education for workers and their children.

The stories described an integrated Paraguay, importance was placed on good connectivity between Asunción and the rest of the country. Diet, fresh food and healthy living were also features of many of these fictional citizens’ lives, as was the use of electric cars and bicycles. Several of the stories described decent livelihoods from farm holdings well integrated in value chains. This involved the efficient organisation of producers, access to financing, and favourable export opportunities. Finally, most stories described a meritocratic system, where citizens who benefited from free education were offered opportunities through scholarships and could travel abroad for their further education but returned to their home country where they found good jobs and were able to provide a prosperous future for their children.

All 11 dimensions of the OECD’s “How’s life” framework were identified in participants’ stories, yet two new dimensions were added: culture and identity, and inequality which was noted as a transversal theme. Participants engaged in a rich discussion around the major obstacles to realising progress and the development objectives of the PND. The most frequently mentioned obstacles holding the country back related to the social sphere with issues such as regional and economic inequality, vulnerability, poor healthcare provision and outcomes for citizens, and skills. Participants also emphasised low investment and insufficient regard for Paraguay’s cultural heritage and identity, and the lack of accommodation of indigenous culture in Paraguay’s cultural identity.

When discussing the root of these obstacles, lack of policy planning, anticipation, and proper implementation were cited. Participants also highlighted the poor management of resources, corruption, lack of compliance with the law, and authorities’ limited capacity to enforce it. The question of skilled human resources was also raised, and weakness in delivery of social services was in part attributed to a lack of trained professionals across several fields. Finally, participants noted that policy often sought to treat all citizens equally, and as a result was not always inclusive, just as institutions were seldom designed to accommodate diversity, perpetuating inequalities.

Paraguay has taken steps to engage with the OECD to find further support for its development objectives. This engagement is piloted by an inter-agency commission under the co-ordination of the STP. It takes several forms, including the simultaneous implementation of an MDCR and of a Public Governance Review, which will analyse in detail the issues of co-ordination by the centre of government, planning and budgeting, open government, human resource management and multi-level governance. Paraguay is also stepping up its participation in OECD committees and analysing the OECD’s normative body to support its own reform agenda.

How’s life in Paraguay? An overview of the OECD well-being framework

Development is often considered synonymous with economic growth, and yet growth in GDP is only one element of development. If aggregate increases in productivity and material wealth do not produce meaningful gains in the overall well-being of a country’s population, development has failed in both human and economic terms. Economic growth is only a means to an end – the sustainable and equitable improvement of people’s lives. To assess comprehensively life within a country, it is necessary to go beyond macroeconomic indicators and monitor well-being across the many different areas that matter for citizens.

Part of the OECD MDCR benchmark analysis examined a range of well-being indicators in Paraguay. Well-being is a multi-dimensional concept and can be difficult to define in isolation as it covers many areas of people’s lives. However, the core idea is relatively intuitive: well-being encompasses those aspects of life that people would consider essential to meet one’s needs, pursue one’s goals and feel satisfied with life (Box 1.2).

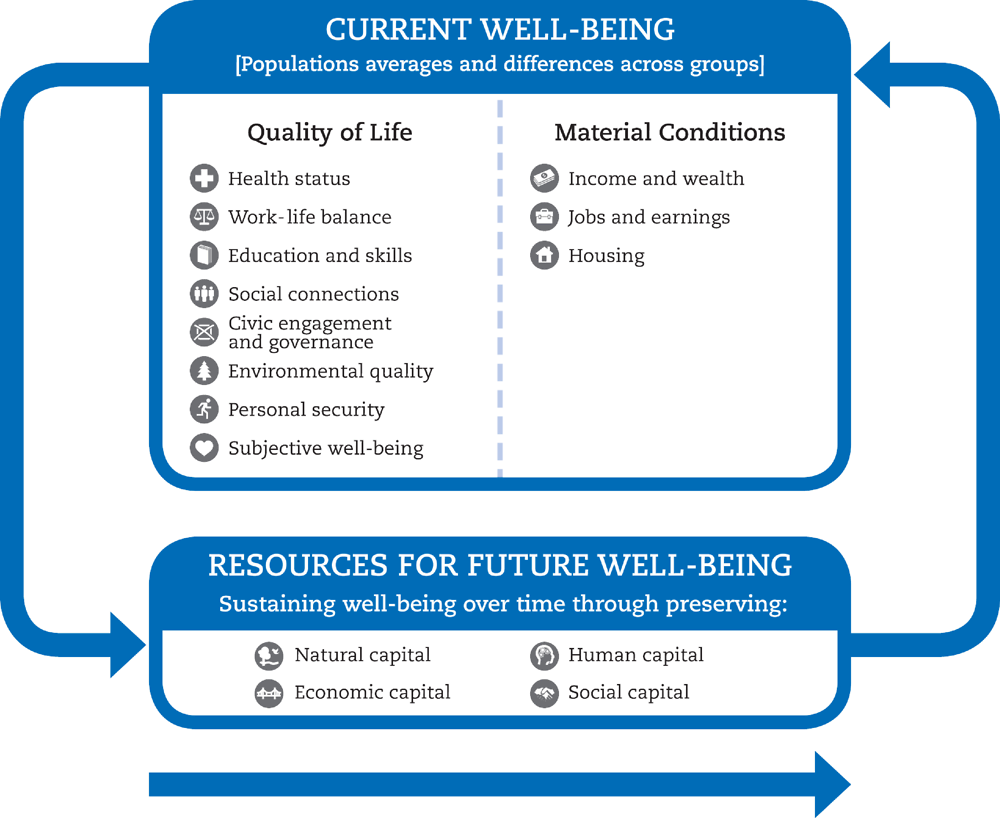

The OECD has developed a framework for measuring well-being in OECD countries based on national initiatives undertaken in several countries and several years of collaboration with experts and representatives from national governments (OECD, 2011). This “How’s Life” framework has also been adapted to measure well-being in non-OECD countries, taking into account the literature on measuring development outcomes and embracing the realities of these countries. Its dimensions have been redefined better to match the availability of data, the priorities and critical concerns of these countries (Boarini, Kolev and McGregor, 2014).

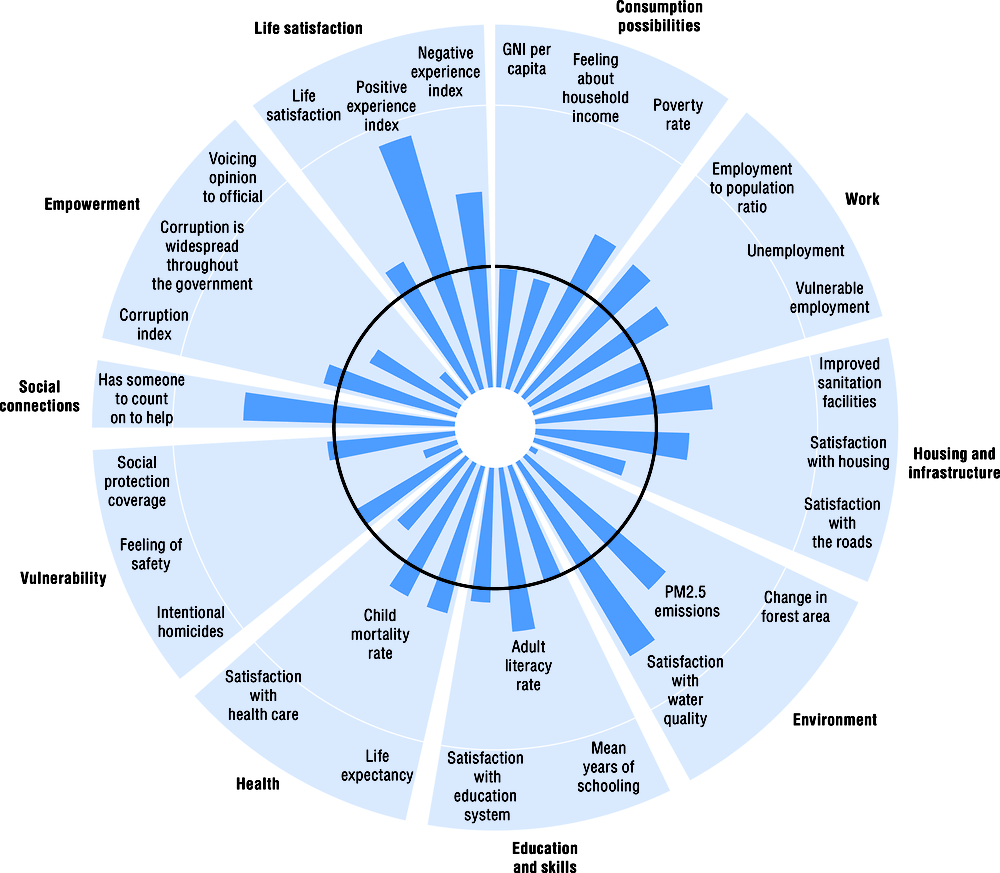

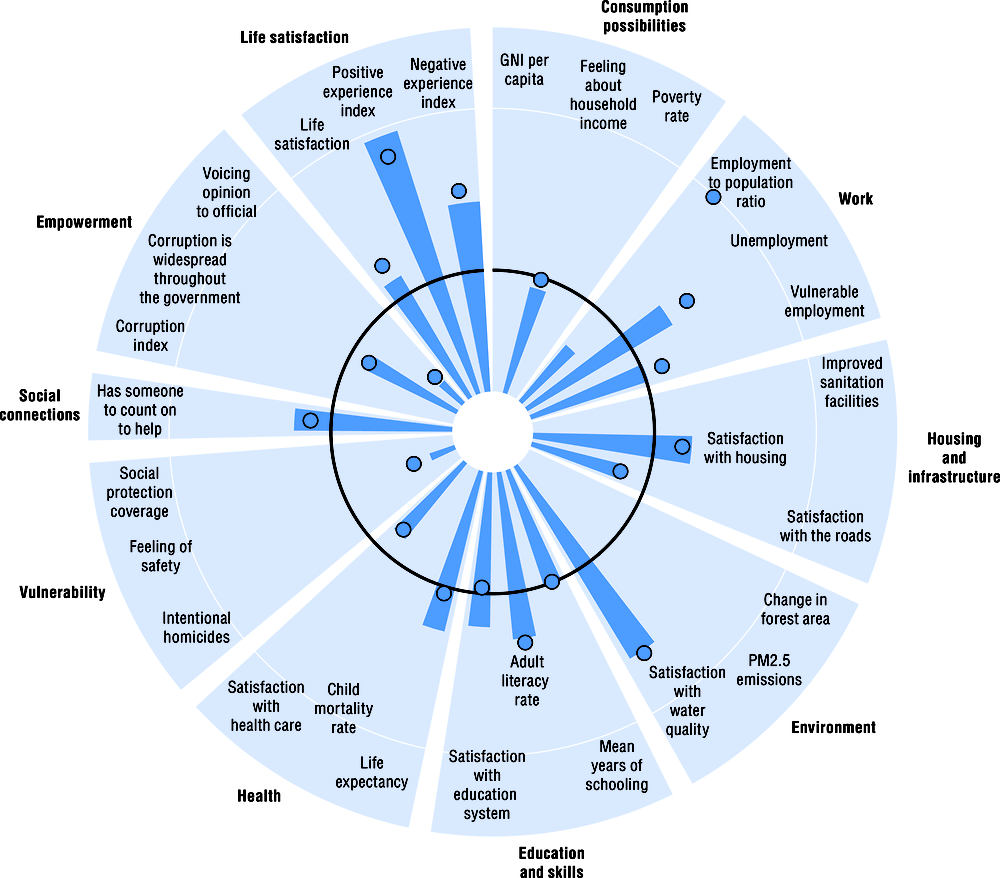

This adjusted framework, like the original one, measures well-being outcomes in two broad fields. The first, material conditions, comprises the dimensions of consumption possibilities, work and housing conditions and infrastructure. The second, quality of life, comprises health status, education and skills, social connections, empowerment and participation, vulnerability and life evaluations, feelings and meaning — i.e. the main aspects of subjective well-being (Figure 1.4). These ten dimensions are used to measure current well-being. They are complemented with another set of indicators to measure the sustainability of current well-being in the future. The framework emphasises the importance of preserving the natural, human, economic and social resources that are essential for ensuring the well-being of future generations.

The OECD well-being framework is informed by a number of analytical principles. First, it is concerned with the well-being of individuals rather than aggregate economic conditions. Second, it focuses on well-being outputs rather than inputs, recognising that outcomes may be uncorrelated with the resources devoted to achieving them. Third, it emphasises the need to measure the distribution of well-being outcomes to identify inequalities across and within population groups. Finally, it considers both objective and subjective indicators, as people’s own evaluations and feelings about their lives matter as much as the objective conditions in which they live (OECD, 2011).

Figure 1.5 shows Paraguay’s performance across a range of indicators that are representative of the ten dimensions of the OECD’s well-being framework. Paraguay’s actual performance (the blue bars) is shown in contrast to its expected performance given its level of economic development (the black circle). Results that are outside the circle therefore represent better-than-expected outcomes; results inside the circle show lower-than-expected outcomes; and the longer the bar, the better Paraguay’s performance in that indicator in relation to its expected outcome.

When it comes to well-being, Paraguay has areas of strengths and weaknesses (Figure 1.5). Paraguay performs reasonably well in the areas of work, social connections and life evaluations but it underperforms in the areas of consumption and empowerment. In most dimensions, the overall situation is relatively good compared to countries of the same level of development. However, many areas are characterised by high levels of inequality. Incomes, access to improved sanitation, health insurance coverage and satisfaction with transport infrastructure differ markedly between rural and urban dwellers (Chapters 3 and 5). Less educated and poorer citizens have worse perceptions of key public services and institutions like the health and justice systems than those who are better educated of better off.

People have jobs but income is relatively low, transport infrastructure is poor, and there is a sizeable quality deficit in housing

Gross national income (GNI) per capita captures the gross flow of income to individuals from earnings, self-employment and income from capital.3 In 2015, Paraguay’s GNI was USD 8 176 (2011 constant PPP) which is slightly below what is expected for countries with similar GDP per capita. In turn, the Paraguayan values are somehow below the Latin American and Caribbean average of USD 12 107 (2011 constant PPP). Similarly, satisfaction with living standards is relatively low. Only 53% of Paraguayans reported in 2015 that they can either get by on, or live comfortably with, their household income, a figure within the same range as the average for the past 7 years. Yet, reaching 7% in 2014 the poverty rate at the international poverty line of USD 3.10 in PPP was lower than what could be expected given the level of development and below the LAC average (11.4%). Poverty according to the national poverty line fell from 45% in 2007 to 27% in 2015 and extreme poverty fell from 14.0% to 5.4% in the same period (Chapter 3). If the 10-year trend continues, Paraguay is on track to meeting its goal of achieving extreme poverty below 3% by 2030.

Labour force participation is high in Paraguay. The ratio of employment to population is 66% among individuals over the age of 15 and has remained stable in the past ten years. In turn, despite having increased from 5% in 2013 to 6% in 2016, unemployment was comparatively low, both in terms of the country’s level of development and when compared to the average for Latin America and the Caribbean (6.8%). The share of those in vulnerable employment, i.e. unpaid family workers and own-account workers, is around 40% and is slightly lower than what could be expected given Paraguay’s level of development. Indeed, vulnerable employment has fallen by almost ten percentage points over the past ten years, thanks largely to the expansion of wage and salaried work. The employment gap between women and men, on the other hand, is larger than in most OECD and benchmark economies and has evolved little over time.

Access to decent housing and infrastructure is another key dimension of material conditions. Paraguay provides access to improved sanitation facilities in their houses4 to 88.6% of its population, a value above what could be expected for its level of development, and up from 62% in 2005. Given the rate of improvement, the goal of achieving universal improved sanitation could be met even before 2030. Similarly, in 2015 54% of Paraguayans were satisfied with the availability of affordable housing, a value that is also above what could be expected given the development level of the country. Official estimates of the housing deficit suggest the deficit pertains to quality, in particular in terms of access to piped water and to the public sanitation grid. Only 17% of the housing deficit is quantitative, that signals the need for building new housing units (Chapter 3). Conversely, for the same year only 44% of people in Paraguay reported being satisfied with the roads, a value that is below what could be expected given the country’s level of development as well as the LAC average (53%). Satisfaction with roads has deteriorated in the past ten years, with 55% of people reporting being satisfied in 2005, which reinforces the significant infrastructure challenge the country faces (Chapters 2 and 5).

Moving ahead: Closing gaps in environment, vulnerability and empowerment

Based on the experience of countries with similar GDP, Paraguay displays mixed results in terms of its environmental performance. It performs better than expected on PM2.5 levels – a measure of particulate matter (PM) of 2.5 micrometres, a size that has severe health effects – with a value of 14.3 micrograms per cubic metre in 2015. In turn, Paraguayans are remarkably satisfied with the water quality as reported by 88% of the population and considerably above what could be expected for its development level. Conversely, the country scores well below expectations on the change of its forest area that, according to 2015 data, experienced a reduction of 17.1% over ten years.

While having a good education makes it easier for people to get a good job, a good education is more than a passport to work. The opportunity to learn new skills can intrinsically be rewarding, and education is generally valued by people as an outcome in its own right. Paraguay performs reasonably well given its level of development. Mean years of schooling of the population aged 25 and above are 8.68 and the adult literacy rate is 95%. Progress in adult literacy has been slow (3 percentage points between 2005 and 2015) but the target of universal literacy by 2030 is within reach. Conversely, weaknesses in the production of key education statistics, in particular enrolment rates, make it very challenging to assess progress in access to education. This is a source of concern given that the PND establishes five numerical targets to be met in enrolment rates (for early childhood education, pre-school, and the three cycles in basic education). In the absence of better measures of the quality of the education system, the reported level of satisfaction is considered. In 2015, two-thirds of Paraguayans reported being satisfied with the education system, a value that is above what would be expected for a country with Paraguay’s level of development and that has been consistently high over the past years, probably reflecting the density of the school network.

Good health is a major determinant of quality of life and a core dimension of well-being. In addition to its intrinsic value, it is vital for people’s ability to work and participate in social life. Life expectancy at birth in Paraguay is 73.6 years (70.8 years for men and 76.5 years for women) according to the most recent projections (DGEEC, 2015). In this regard, Paraguay performs relatively well given its level of development. Progress in life expectancy has been slow (2.4 years gained on average in ten years); indeed too slow to meet the target of 79 years by 2030. The recorded child mortality rate per 1 000 live births in 2015 was 16.4, still higher than the average for Latin America and the Caribbean.5 However, fewer than half of Paraguayans (43%) reported being satisfied with the health system, a figure that is below what could be expected given the country’s level of economic development and similar to the value from ten years ago (48%) (Gallup, 2016).

In the OECD well-being framework vulnerability is understood as the exposure to risks such as food or income insecurity, job loss, illness, or physical violence. Paraguay’s results in this dimension of the framework are either as expected or below expectations given its level of development. In 2014, its rate of intentional homicides per 100 000 people was 8.4 – much lower than the LAC average (25.04 per 100 000 people), a full 9 points below the level ten years ago, and as expected given Paraguay’s level of economic development; however, the average could hide some worrisome values in specific regions (see Chapter 5). At the same time, people’s perceived level of safety is relatively low: in 2016 only half of Paraguayans surveyed reported that they felt safe walking home alone at night, which is much lower than the expected value. Beyond, personal security economic insecurity is another source of vulnerability with the capacity to affect the quality of life. Slightly more than half of Paraguayans were covered by social protection, labour and transfer programmes in 2011, a level that is a little higher than what could be expected for a country with a similar level of development. Despite this good relative performance, health insurance coverage has stagnated below 30% of the population since 2013. Even if it were to continue on the upward trend of the first decade of the 2000s (4.4 percentage points over 10 years), the target of universal social security coverage would not be reached by 2030. This gap in social security is largely due to the persistence of informality (Chapter 3).

Social connections in Paraguay are relatively strong. Good proxies of the strength of close personal networks in a country are the proportion of people feeling that they can count on others in times of need and the amount of time people spend with friends and family. In Paraguay, 91% of those surveyed said that they have at least one friend or a relative that they can turn to for help in a time of need, a value which is above the LAC average (84%).

Paraguay has significant weaknesses in the area of empowerment and participation. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (Transparency International, 2016), which ranks countries based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be by business people and country analysts, Paraguay ranks relatively low (123/176) for countries where data are available. This is in line with its level of economic development. Notwithstanding Paraguay’s relatively low score, its performance in the Corruption Perception Index has improved markedly since it entered the ranking in 2002 as one of the countries with the highest perception of corruption among those ranked (98/102). Between 2010 and 2016, the country gained 23 places in the ranking while the total number of countries remained stable. However, according to the Gallup World Poll, 74% of the population think corruption is widespread in government and only 19% believe that elections are honest (see Chapter 5). In respect of participation, just 8% of people have voiced their opinion to a public official, the lowest value amongst LAC countries. Finally, only 28% of the population trust the government (see Chapter 5).

Life evaluation is measured through three distinct channels to disentangle people’s daily experiences (feelings and emotions) from overall life satisfaction. These measures are based on the idea that people are the best judges of how their own lives are going (OECD, 2011). Using the Cantril Ladder, a measure which asks respondents to rate their lives as a whole on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 representing the worst possible evaluation and 10 representing the best, average life satisfaction in Paraguay is 5.6, as compared with a Latin American average of 5.9 but still above what is expected for a country with a similar level of development. Using a set of ten positive and negative “experiences”, Paraguay shows more unbalanced results (higher-than-expected on the positive experiences but lower-than-expected on the negative experiences). These experiences include, on the one hand, feeling well-rested, laughing and smiling, enjoyment, feeling respected, and learning or doing something interesting, and stress, sadness, physical pain, worry and anger on the other. The high overall level of subjective well-being relative to the level that could be predicted based on the country’s GDP per capita is a feature that Paraguay shares with most other Latin American countries.

The well-being framework within each dimension: The case of gender inequalities

The OECD well-being framework also takes account of inequalities within each dimension, consistent with the idea that community welfare reflects both average outcomes and how they are distributed across people with different characteristics. For instance, gender inequality is a cross-cutting issue that should be gauged across every dimension of well-being. Women tend to have lower outcomes in most of the dimensions of well-being and lag significantly in the areas of jobs, vulnerability life evaluation and consumption possibilities (Figure 1.6). In particular, in respect of jobs, they are more likely to be out of the labour market and have a higher risk of being unemployed.

Assessment and key constraints to development in Paraguay

Prosperity

The Paraguayan economy remains among the strongest growing in the region but with significant volatility. This growth volatility is mainly due to its reliance on agriculture and livestock production as leading economic activities. Over the past few decades, Paraguay’s exports have been marked by low levels of diversification and are mainly concentrated in products such as soybeans, beef meat and electricity. However, in recent years, some diversification across export destinations has been observed, shifting from the neighbouring countries towards the European Union and Asia. Moreover, there has been a gradual increase in the technological content of exports; the growth in export during the 2000s has been accompanied by an increase in the share of agriculture-based manufacturing products from 25% to 35% of total exports. Labour reallocation from agriculture to other sectors, especially manufacturing and services, shows that structural transformation is proceeding at pace. As a result a number of sectors (livestock, construction, financial services) have seen their shares of value added grow, while manufacturing has contributed an increasingly larger share to aggregate growth.

Monetary policy and the inflation-targeting regime have helped to control inflation volatility with both the explicit target and the tolerance range being gradually adjusted downwards. To support the monetary policy framework, efforts to develop the financial system and the interbank market should be strengthened and liquidity conditions carefully monitored. The introduction of the Fiscal Responsibility Law (FRL) and the Advisory Fiscal Council represent an important step in terms of fiscal sustainability, as part of a broader package of reforms in macro-fiscal policy. The implementation of the FRL has been challenging and the possibility of amending the law is being considered as it does not allow for the implementation of counter-cyclical measures and represents a constraint on public investment. Any changes should be analysed carefully, should guarantee credibility, and should be clearly communicated. The fiscal framework is sound but tax collection and capital investment should be improved. Tax collection in Paraguay is still low compared to benchmark countries despite recent improvements, in particular in tax collection from domestic activity. This is particularly because of low tax rates (more details in Chapter 6) although evasion and informality also play a role. Government efforts to contain current spending are noteworthy, having declined in recent years and allowing for a slight increase in social spending and government investment. However, although starting to pick up, the level of investment in Paraguay has been considerably lower than in OECD and Latin American countries. Paraguay still faces significant challenges in budgetary execution and management of public investment projects. Further government efforts to facilitate capital investment would contribute to boosting growth.

Strengthening productivity and competitiveness is also essential for sustaining long-term growth but several challenges remain. Although Paraguay has shown strong growth in recent years, the income gap remains high compared to OECD countries and most of the difference is explained by labour productivity. Despite government efforts and implemented measures, several challenges still remain to boost productivity and competitiveness. Resources invested in research and development activities in Paraguay are low relative to benchmark countries while private sector investment and involvement should be strengthened. There is also wide scope to boost productivity by improving the quality of education and reducing skills mismatches while high-quality infrastructure and connectivity are fundamental to both raising productivity levels and improving social inclusion. The institutional and regulatory framework should be set in a way that boosts further competition and government efforts to help to reduce barriers to investment, trade and entrepreneurship are therefore welcome.

People

Paraguay’s growth performance has led to improvements in incomes but inequality remains substantial. The recent period of economic growth has contributed to raising the living standards of many Paraguayans. In the period 2007-14, income growth “lifted all boats”, contributing to a significant fall in income poverty, which fell from 45% in 2007 to 27% in 2015. Macroeconomic stabilisation also contributed to containing poverty by limiting food price inflation. In contrast to the fall in poverty, inequality remains high in Paraguay and a major concern of citizens. Income inequality has fallen in the past five years but less than in other Latin American countries in the past decade. The territorial dimension is an important contributor to inequality. Levels of monetary and non-monetary deprivation are higher in rural areas, in terms of income poverty but also of access to water and sanitation or health insurance. Public social programmes have expanded notably in the years since 2009. Among them, the social pension and the main conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme (Tekoporã) have noticeable effects on income poverty, although they remain small. In fact, taken as a whole, the fiscal taxation and redistribution system in Paraguay has very limited impacts on inequality and poverty. The impact of social policy in other areas of well-being is larger and better documented, in particular in terms of children’s use of health and education services. The expansion of free universal health care provision by the Ministry of Health has also contributed to improved outcomes by reducing gaps in the accessibility of service, in particular between urban and rural households. A notable expansion in housing programmes, whose budgets have more than doubled in real terms, has made it possible to build 10 000 dwellings a year since 2015.

Employment outcomes are quantitatively good, although informality and job quality remain major challenges. Net job creation over the medium term has been good, overtaking rapid growth in the working age population. As a result, unemployment is low and labour force participation remains stable at levels comparable to benchmark countries, although female labour force participation is low and volatile. The sector distribution of employment points to a dynamic structural transformation process, with agricultural employment falling by ten percentage points in favour of services and construction. These changes have been particularly notable in rural areas, including with the development of secondary sector jobs. This transformation has seen a steady increase in salaried work in both the public and the private sectors. In spite of these changes, job quality remains an issue for many workers: domestic workers, unpaid family worker and own-account workers account for 46% of employment and almost two-thirds in rural areas. Informality, which concerns 64% of workers outside agriculture is a major issue, and explains why 44.5% of employees do not earn the minimum wage and why social security coverage is low. Informality poses a challenge due to the absence of a suitable social protection regime (pension and health insurance) for independent workers. The share of informal employment has fallen by a percentage point per year on average in the past five years, a relatively slow pace compared to the process of structural transformation and the prevalence of informality. Labour market institutions are relatively weak, with low rates of unionisation and little collective bargaining. While employment protection legislation is not particularly stringent, the combination of high minimum wages relative to market wages, and of contribution rules in social security make formalisation costly for employees.

Education outcomes have progressed but need further improvement. Although it performs at the expected level for its level of development, the country is among those with the lowest adult educational attainment among the benchmark countries, with 8.7 years of education among adults on average. The cohorts educated since 1990 have significantly higher attainment but estimates of school life expectancy for Paraguay are lower than for benchmark countries, which casts doubt on whether this will be sufficient to catch up. Although limitations in statistical capacity hamper the analysis of access to education, survey data suggest that access to primary and lower secondary education is nearly generalised, with the exception of indigenous areas, thanks in part to previous education reforms aiming at expanding coverage. Gaps in access to school remain significant for pre-primary education and upper secondary education, and in both cases gaps between rural and urban areas remain wide. Progress in recent years has been notable in secondary school and especially in tertiary education, where access has grown rapidly although, at 35%, gross enrolment rates remain low compared to benchmark countries. The quality of education remains a major challenge. Learning outcomes underperform with respect to the expected proficiency as described in the national curriculum (for almost three quarters of grade 3 students) and relative to benchmarking countries in the region. Among the main challenges facing the education sector are gaps in the qualification of teaching staff and in infrastructure. Improving the skills of teachers is one of the key objectives of Paraguay’s recently created national programme for postgraduate scholarships abroad (BECAL), which also finances postgraduate studies for researchers and science and technology specialists. The Fondo Nacional de Inversión Pública y de Desarrollo (FONACIDE), created in 2012, channels resources from the royalties obtained from the binational plant of Itaipú to education, research and social infrastructure. FONACIDE has been instrumental in sustaining the increase in funding to support education, especially through financing investment in schools. In spite of a recovery in public expenditure in education and earmarking of funds for social infrastructure, limited absorption capacity is a constraint on the speed at which these challenges can be overcome.

The efficiency of social service delivery is limited by the fragmentation of the social protection system and informality. The prevalence of informal employment and contribution rules for own-account workers limit the coverage of contributory social security to 22% for the pension system and 29% for health insurance. The pension system is characterised by the multiplicity of regimes, subject to light regulation and with varying degrees of financial health. The generous provisions of the general regime contrast with the low coverage and the expansion of the non-contributory pension financed by the general budget. The health system is also fragmented both on the financing side and in service delivery. Despite advances in free universal health care provision, the elimination of user fees in Ministry of Health services and programmes to grant free drugs to certain categories, health is largely financed by households, and out-of-pocket payments were estimated to be as high as 49% in 2014. High out-of-pocket payments create obstacles to effective use of health services and reinforce inequalities in health status. Social assistance and income support programmes are also fragmented, with overlapping objectives and differences in targeting methods. The consolidation of anti-poverty measures under an umbrella programme (Sembrando oportunidades), the ongoing implementation of a single targeting tool and improved ad hoc co-ordination are contributing to greater efficiency. However, given the relatively weak impact of transfers on monetary poverty, there is potential for greater effectiveness in institutionally co-ordinated action. To succeed in addressing informality, co-ordination in programme design, implementation and enforcement is a necessity.

Planet

Geography has endowed Paraguay with one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. With access to a large tropical forest and a vast number of water endowments, the country provides abundant resources for agriculture and livestock development. With one of the cleanest energy mixes in the region, based on the use of hydropower, Paraguay has managed to keep the economy’s carbon intensity at low levels and allowed the country to manage air pollution. Total greenhouse emissions also remain relatively low. However, the current economic expansion, largely based on the use of land for agriculture and livestock development, has put increasing environmental pressure on the country. Deforestation remains one of the most critical issues in terms of environmental sustainability.

While costs are low by comparison with other countries, access to public services, including water, sanitation and waste management, is still limited for a large part of the population, and regional disparities in the quality and distribution of these services persist. The rapid urbanisation process has increased pressure in Asunción and intermediary cities, and water shortages and poor water quality are major concerns for the authorities, particularly in urban areas. In rural areas, natural disaster prevention has gained importance after two recent episodes where agricultural production was affected.

To maintain the current economic momentum and guarantee that it benefits the entire population, Paraguay needs to incorporate the sustainable use of environmental resources and capabilities into its development agenda. There are considerable needs in terms of environmental protection that are not being met. The regulatory framework against deforestation is insufficient and is not being implemented, and more support to strengthen the institutional setting is needed, particularly at the local level. Waste management is another issue of concern, and is mostly based on landfilling as the primary disposal method.

With access to abundant clean hydropower energy, Paraguay could be at the forefront of environmental policy in the region, promoting renewable energy, building an energy-efficient technology, improving energy utilisation in transport, among other areas. However, only 29% of total energy consumption comes from this clean electricity, the bulk coming from fuel and biomass. Transport, which accounts for nearly 90% of Paraguay’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, is one area where improvements could be introduced, introducing electricity-based systems and incentives to reduce biomass consumption in the industry sector. Improving land management will be fundamental to the implementation of a strategic plan for the environment.

Peace and institutions

Paraguay’s vision for 2030 is that of a democratic, supportive state, subsidiary, transparent and geared towards the provision of equal opportunities. Governance institutions in the country are still undergoing fundamental transformations. Today, democracy in the country is still in a consolidation phase. The process of consolidation since the transition to democracy in 1989 has been convoluted. Fewer than half of Paraguayans consider that democracy is preferable to any other form of government and fewer than one quarter of citizens are satisfied with how democracy works in the country. Satisfaction with democracy almost doubled between 2006 and 2015 in spite of several episodes of political instability, signalling a certain degree of resilience of democratic institutions. Further strengthening the justice system is crucial for ensuring the rule of law. Only 28% of Paraguayans trust the judiciary, compared to 42% in benchmarking countries and 54% in the OECD. Those in urban areas and with higher education have higher levels of trust, as they are able to overcome barriers to access justice. The justice problem faces a number of constraints, including the range of functions that the Supreme Court fulfils on top of its core function of administering justice, the relatively small number of judges, and the pervasive influence of entrenched informal institutions that limit judicial independence.

Perceived personal insecurity is comparatively high in Paraguay, although violence is unequally spread and more prevalent in border areas. Homicide rates have fallen considerably in the past years, and homicides are concentrated in a small number of departments in border areas and the area of operation of the Paraguayan People’s Army guerrilla group. Despite ongoing efforts, smuggling, drug trafficking, counterfeiting and money-laundering continue to take advantage of porous borders and weak law enforcement.

The capacity of government is limited by its relatively small size. Government expenditure reached 25% of GDP in 2015, compared to 34% in LAC countries and 45% in OECD countries. Public employment is also relatively low. Strategically planning for the right mix of skills in the civil service in the years to come will help the government meet strategic objectives as well as increase efficiency, responsiveness and quality in service delivery. In turn improvements in service delivery and maintaining commitment to inclusiveness, transparency and efficiency are needed for increasing levels of trust in government, which remain low. Indeed, satisfaction with service delivery is a significant challenge in Paraguay. While satisfaction with the education system is relatively high, satisfaction with health care, transport infrastructure and the transport system is low relative to benchmarks and particularly so for rural dwellers and for the most disadvantaged.

Paraguay has advanced towards the development of a comprehensive and coherent integrity system, with transparency playing a major role, but ensuring its effectiveness remains a big challenge. Perceptions of corruption by citizens are high, relative to regional peers and have evolved little in the past ten years. The government has taken a number of initiatives as part of a National Plan for the Prevention of Corruption. Among them, a key institutional pillar is the creation of a national anti-corruption agency (SENAC) which has been successful in co-ordinating and ensuring that all institutions in the executive branch establish an anti-corruption unit, and in raising awareness about public sector integrity issues. Transparency efforts play a major role in the fight against corruption. Paraguay has made strides against corruption in public procurement by making all procurement information available on line and including a whistle-blowing function in the procurement agency’s electronic platform. The mandatory provision of information on the use of public resources, including the remuneration of civil servants, and the law on transparency and access to information adopted in 2014 also underpin the government’s strategy for increasing citizen oversight of public affairs. Significant challenges remain, however, including ensuring political will to follow through on complaints raised, of which only a small number have so far led to administrative investigation, and the limitations in the scope of SENAC’s action, which focuses only on embezzlement, but not other forms of corruption, and the absence of a specific provision for whistle-blower protection.

The development of the open government strategy in Paraguay has spearheaded a whole-of-government approach to promote transparency, empower citizens, fight corruption and harness new technologies for strengthening governance. Following a first action plan in which most of the actions were effectively linked to the development of information systems and less to mechanisms for civic participation and accountability, and which was faced with a degree of resistance, the action plan for the 2014-16 period was conceived through a participatory approach with 12 government institutions and nine civil society organisations. Progress in the form of legal and institutional reform has been notable and the country ranks fourth among Latin American countries with information in the OECD Index on Open Government Data and above the OECD average in the same index. While considerable efforts have been made to enhance openness by making information available, challenges remain to tailor public information to citizens’ needs and strengthen accountability mechanisms.

Partnerships and financing for development

Analysis of financing flows for development shows that they are low in Paraguay compared to both the benchmarking countries and the OECD. Given the country’s prudent fiscal stance and low reliance on public debt, public financing comes mostly from fiscal space. Fiscal space is helped by idiosyncratically high non-tax revenues from the two binational power plants, but constrained by relatively low tax revenues, reflecting low tax rates and evasion rates above the regional average. The weight of non-discretionary expenditures, which represent almost half of total public expenditure, also limits fiscal space. The country has recently made notable progress on both fronts. Tax revenues have increased by 5.4% of GDP since 2000 and the country has implemented major fiscal reforms, including the progressive implementation of the personal income tax since 2012, the expansion of VAT to the agricultural sector and the introduction of a tax on profit from agricultural activities in 2014. Measures are also being taken to limit the growth of the public wage bill, to reduce the weight of non-discretionary expenditures, which has led to public investment and capital expenditure growing at much higher rates than current expenditures, even if the weight of the latter remains high at 85% of total expenditure.

Private development flows, at 5.5% of GDP are relatively modest compared to public financing flows of 11.8% of GDP. Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows remain small: they accounted for 1.16% of GDP in 2016, the third lowest in the region. The importance of FDI is growing, however, and the government’s investment attraction strategy is bearing fruit. Net FDI flows averaged 1.7% in 2010-16, an improvement compared to previous periods, and inward flows increased by 5% in 2016, against the trend in the South American region, where they fell by 9%. The recent dynamism in FDI flows has been partially driven by efforts to create an attractive regulatory framework and measures to attract investment. These measures have contributed to transforming the composition of investment with a notable increase in the maquila industry, increased diversification in countries of origin, and the development of sectors with greater job creation prospects such as automotive components.

The stability of the Paraguayan financial system is a major asset for development, but it needs to be further developed and become more inclusive. The banking sector is well capitalised, with sufficient access to sources of deposit financing and highly profitable. Credit growth has accelerated in recent years, with 26% average banking credit growth over the 2005-15 period, and banking credit to the private sector reached 43% in 2015. To better finance development, the regulation of the financial sector as a whole needs to be strengthened beyond that of the banking sector. Moreover, high interest rate spreads and reliance on short-term finance reflect constraints in the quality and availability of creditor information as well as the reliance on consumption credits. Financial inclusion is still very low and unequal in the country in spite of rapid growth in credit. Together, these constraints prevent the financial sector from making an even greater contribution to the country’s development.

Key constraints to development in Paraguay

The main constraints to development identified by the first phase of the MDCR are interrelated and stem from the institutional and economic history of Paraguay, as well as from its growth model. The country’s development path has been largely dependent on the development of highly productive mechanised agriculture and extensive animal farming, in a context of highly concentrated ownership of factors of production, especially land. As a result, the primary distribution of income in the country is unequal, the distribution of opportunities across the territory is uneven, and there are strong pressures on environmental resources. The country’s economy has developed alongside a state with relatively limited reach, with relatively low taxation and public expenditure, where a number of markets are lightly or not regulated and where direct control of economic endeavours by the state is rare, with exceptions in network industries and energy in particular. In such a context, power relations that permeated the state under the authoritarian regime through a number of informal practices, and which remain to some extent, limit the efficiency of public service delivery, the equality of treatment and the efficacy of enforcement.

The Paraguayan government faces two major challenges in achieving the country’s vision, given its development model: to steer the economy to deliver sustainable growth in the medium term and to improve the country’s capacity to stem inequality. The agriculture-based development model as it has developed makes both of these tasks more difficult. Mechanised agriculture generates few jobs and the absence of diversification explains in part the high levels of informality in the country as many create their own jobs in low-value added services sectors. Informality fuels inequality in earnings and implies lower efficiency in tax collection, further weakening the capacity of the state both to alter the secondary distribution of income and to steer the structural transformation of the economy.

This system is evolving through changes in fiscal policy and emerging diversification. A major shift occurred in 2014 with the fiscal reform, extending VAT to agricultural produce and reforming the tax on profits from agricultural activity. Together, these reforms significantly raised the fiscal contribution of the sector to the public purse, although it remains smaller than its share of value added. Another key development is the progressive structural transformation taking place. The development of the agribusiness value chain itself can increase indirect job creation in firms offering services to agricultural producers (technical assistance, marketing of inputs like seeds, finance, transport and others) although many of these activities require qualified labour. While the thrust of industrial policy in Paraguay rests on exploiting comparative advantage by moving up the value chain in agricultural products and development agro-industry and related services, non-traditional sectors have also developed recently, especially as maquilas integrated into global value chains.

One of the major challenges for Paraguay is to buttress sources of economic prosperity that will sustain growth in the medium term. The current high contribution of total factor productivity to economic growth is an encouraging symptom of the ongoing structural transformation and institutional development in the country. However, the contribution of capital accumulation is lower than could be expected in the country given its position relative to the region and the scope for productive investments with both economic and social returns, as the large infrastructure needs suggest. The efforts on the part of the public sector in this regard are noteworthy. Within the limits imposed by the fiscal responsibility law, public investment has grown rapidly in recent years, and efforts are under way to increase tax revenues and improve the balance in the composition of expenditure. A large share of non-tax revenues is earmarked for infrastructure spending, shielding it from political intervention. However, given the size of the Paraguayan state, this will not suffice. Given the country’s very prudent approach to international debt, the government is implementing means of intervention that will crowd in private financing, such as public-private partnerships.

The second major challenge is to increase the inclusiveness of the development path. Further improvements in infrastructure would contribute to integrating territories better. This would increase economic opportunities and the ability to deliver public services in remote areas. In terms of social policy, the flagship social assistance programmes have grown rapidly in the past few years, but the fragmentation of social protection limits its efficiency and undermines equality of opportunity. The prevalence of informal work is a key cause of this fragmentation, of which one important dimension is between social security –which covers formally employed workers– and non-contributory systems – which cover informal workers or the poor.

Improving educational outcomes is a crucial element in fulfilling the potential of all citizens. It is also a critical ingredient to reduce inequality in the distribution of market incomes. As structural transformation and internal migration progress, the capacity of new entrants into the manufacturing and, especially, the services sectors, to enter more productive segments, is of great importance also to ensuring that structural transformation contributes to productivity growth in the country. Recent successes in ensuring the quality of education and in expanding vocational training and professional education should be greatly expanded; they can contribute to making education more pertinent for the labour market.

Increasing inclusiveness also requires more inclusive patterns of production. They can generate livelihood opportunities to vulnerable groups across the country’s territories. Indeed, the PND considers regional development and productive diversification jointly as one of the 12 strategies for implementation. The strategy is currently focused on increasing productivity and developing opportunities for smallholder agriculture. The development of formal manufacturing jobs in rural areas and the importance of non-farm activities in stimulating rural development in the region and elsewhere suggest that such a strategy should consider activities in the agri-food value chain besides agriculture, and beyond.

The main constraints identified can be bundled together into two overlapping domains: constraints that limit structural transformation and sustainable growth, and constraints that limit the capacity of the state. In each of these domains, three priority areas for action can be identified:

Structural transformation that unlocks new sources of growth can be encouraged by:

-

Continued efforts to close the quantitative and qualitative gap in infrastructure, which is a major component of the historical investment deficit in Paraguay and affects the potential return of new investments as well as their geographic location.

-

A systemic approach to education reform, so as to increase attainment and ensure a better match between the skills generated by the education system and the demands of the economy.

-

Further efforts to strengthen governance so as to ensure that public affairs are, and are perceived to be, efficient and fair.

The capacity of the state to steer the economy in a sustainable growth path and to further social development can be strengthened by:

-

Further unlocking finance for development through domestic resource mobilisation and crowding in private investment flows.

-

Addressing informality and the fragmentation of the social protection system that has emerged as a result and which limits the efficiency of public action in poverty reduction and redistribution. Addressing this issue requires reforms in the areas of old age pensions, health and social assistance, as well as an integrated approach to informality.

-

Developing a territorial approach to public policy that accounts for the specific comparative advantages and circumstances of each territory and builds upon local development plans.

References

Arce, L. D., J. C. Herken Krauer, and F. Ovando (2011), “La Economía del Paraguay entre 1940-2008: Crecimiento, Convergencia Regional e Incertidumbres” [The Paraguayan economy between 1940 and 2008: Growth, regional convergence and uncertainties], Working Paper No. 5, Paraguay. 200 Years of Independent Life. From Instability and Stagnation to the Challenge of Sustainable Growth and Social Equity Series. Tinker Foundation and CADEP, Asunción.

BCP (2017), Statistical annex to the economic report (database), Banco Central de Paraguay, https://www.bcp.gov.py/anexo-estadistico-del-informe-economico-i365.

Boarini R., A. Kolev and A. McGregor (2014), “Measuring well-being and progress in countries at different stages of development: Towards a more universal conceptual framework”, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxss4hv2d8n-en.

DGEEC (2015), Paraguay. Proyección de la Población Nacional, Áreas Urbana y Rural por Sexo y Edad, 2000-2025. Revisión 2015 [Paraguay, Projections of national population, for rural and urban areas, by gender and age, 2000-2025. 2015 Revision], Dirección General de Estadística, Encuestas y Censos, Fernando de la Mora, October, www.dgeec.gov.py/Publicaciones/Biblioteca/proyeccion%20nacional/Estimacion%20y%20proyeccion%20Nacional.pdf.

Fernández Valdovinos, C. G. and A. Monge Naranjo (2004), “Economic Growth in Paraguay”, Economic and Social Study Series, RE1-04-009, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington DC.

Gallup (2016), Gallup World Poll, http://www.gallup.com/services/170945/world-poll.aspx (accessed 1 June 2017).

Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay (2014), Plan Nacional de Desarrollo. Construyendo el Paraguay del 2030, Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, http://www.stp.gov.py/pnd/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/pnd2030.pdf.

Investor (2015), Agricultura y desarrollo en Paraguay, Unión de Gremios de la Producción, Asunción.

Masi, F. (2014), “2015: El crecimiento económico y el factor agroalimentario”, Economía y Sociedad No. 27, CADEP, Asunción, www.cadep.org.py/2015/10/economia-y-sociedad-n31-2/.

Ministerio de Hacienda (2017), “Evolución del Gasto Social 2003 a 2017” [Social Expenditure 2003 to 2017], Asunción, http://www.hacienda.gov.py/web-presupuesto/index.php?c=275.

OECD (2015), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en.

OECD (2011), How’s Life? Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264121164-en.

Transparency International (2016), Corruption Perception Index (database), http://www.transparency.org.

UN (2015), “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, Outcome document of the United Nations summit for the adoption of the post-2015 development agenda, A/RES/70/1, United Nations, New York, http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E.

UNESCO (2017), UIS.stat (database), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx (accessed September 2017).

UNICEF (2015), “Levels & Trends in Child Mortality”, Estimates developed by the Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, UNPD.

World Bank (2016), World Development Indicators (database), Washington DC, http://data.worldbank.org.

During the workshop “Paraguay: Future, challenges and global environment”, participants prepared stories describing the life of ordinary citizens in Paraguay in 2030 in a future where development policy has succeeded. These stories are summarised here.

“Aracy González is 40 years old and is a civil servant. She lives in San Lorenzo but works in Asunción. She has a healthy breakfast and uses public transport to get to work. Schoolchildren, sportsmen and professionals also use public transport, all keen to go to work. While she travels, she obtains useful information for her job via IT. Her working time is flexible, she can go to the office only 2 or 3 days a week. Her work is measured by her productivity and not the amount of time she is at the office. All the work is done electronically. On her way back from work, she picks up her children at the community centre. There is no informal work. All amenities are handy in the community: education, leisure activities, etc. She fulfilled her objectives and is happy.”

“Jasmine is 32 years old and from Carapeguá. She studied Administration at a university outside Asunción. There is a pig slaughterhouse in Carapeguá where she has been hired as head of department. She gets up at 4 am and works until 2pm and has a car of her own. Jasmine benefits from social security, a reformed IPS capitalised with resources from Itaipú. She has 2 children, 4 and 6 years old. Her husband works in a 7 hectare farm. He works in a programme for the production of pig feed. He gets home in time to welcome the boys after school, who study until 4:00 pm. Once a year they enjoy a vacation in the coast of Brazil. They live with their parents who do not have insurance but do receive certain subsidies form the government. Jasmine likes her home and is happy that she did not have to sell her lands and move to the city, though she does enjoy occasional trip to Asuncion to visit the malls and shops. Jasmine participates in a women’s club and the boys go fishing on weekends.”

“Estanislao Bacete is 33 years old and lives in Bache San Pedro. He did not go to university. He is married to Juana, who is 30 years old. They have 2 children of 8 and 10 years: Juanita and Pedrito. They are farmers, but live comfortably as their harvest has low production risks, and is integrated in a value chain. The family enjoy a healthy diet, with a balanced family breakfast every morning with fresh milk. The children go to school on public transport and the school has a single shift. Juanita is to participate in the Mathematical Olympiads in Mexico. Her dream is to get a scholarship to study economics in Chicago. Estanislao enjoys a quiet life, with stable income, health and vacations. He feels like an integrated citizen who can provide for his family.”

“Mariana is 30 years old, and is currently studying for a masters’ degree in civil engineering abroad. Originally from Aripahuari, she has been offered a job in Asunción upon return from her studies to fulfil her scholarship’s requirement. Mariana has a son. She could not bring him to school but the father took leave to take care of the child. He has a good job opportunity, has medical benefits, security, and efficient public transport to reach the city. They live in a city where you can get around by bicycle or walking. The father was unemployed for a year but wants to raise capital to start a company. Mariana is happy because the family is able to avail of welfare and she is in a situation where she can realise her professional dream and can contribute to her country.”