Chapter 1. Gender equality in Canada: the state of play

This chapter outlines Canada’s relative position in the OECD for key international gender indicators and provides a historical context on government action in relation to gender equality. The chapter also outlines the current political commitment to a 'feminist agenda' in Canada, and looks at the extent to which this has acted as a catalyst for the federal administration to accelerate the implementation of gender equality initiatives. Finally, the chapter outlines the role of government-wide gender equality policy strategies at federal and sub-national levels in Canada, building on the recently launched Gender Results Framework.

1.1. Introduction

Canada has a tradition of support for gender equality, a principle which is enshrined at the constitutional level and which has been advanced through political and administrative initiatives over successive governments. This has contributed to Canada scoring well in international metrics of gender equality, particularly in the area of educational attainment and women’s participation in the labour market. But challenges remain, for example in the gender wage gap; in women’s under-representation in engineering and computer sciences education subjects; women's access to leadership positions in the private sector; and gender-based violence. Canada’s Indigenous peoples face additional challenges in society and in public life, and this can compound the gender inequalities they experience. This chapter outlines Canada’s relative position in the OECD for key international gender indicators and provides a historical context on government action in relation to gender equality. The chapter also outlines the current political commitment to a 'feminist agenda', and looks at the extent to which this has acted as a catalyst for the federal administration to accelerate the implementation of gender equality initiatives.

1.2. Gender equality: policy achievements, impacts and challenges

1.2.1. Gender equality in leadership

In the political sphere, in 2015, the federal Government appointed Canada's first-ever gender parity Cabinet in which key ministerial positions such as Justice and Foreign Affairs are held by women. This delivered a clear signal, both nationally and internationally, about the high-level commitment to gender equality and inclusion as central principles of public governance.

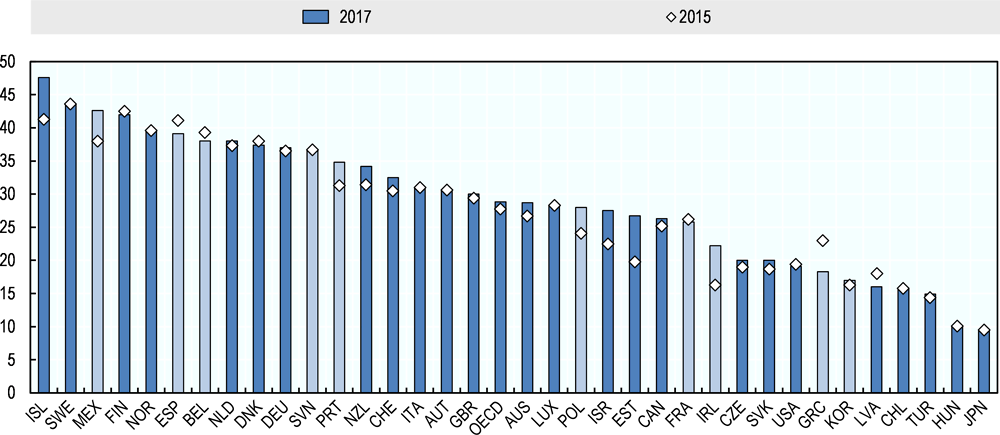

Despite these gains in equal representation in the Cabinet, women remain underrepresented in the Canadian Parliament. Only 26% of Canada’s Members of Parliament (MPs) in the House of Commons are women, compared to the OECD average of 29% in 2017 (see Figure 1.1). In the Senate, the representation of women is somewhat higher: 43% of Senators are women, a significant increase from 36% in 2011. At the sub-national level, women currently represent 29.6% (222 out of 751) of all provincial and territorial legislators across Canada (OECD, 2017[1])1.

In the private sector, while there has been an upward trend in the representation of women in senior management and on corporate boards in Canada, there is room for progress. Women in director positions continue to account for a minority of Canadian board seats. In 2016, the share of seats held by women on boards of directors in publicly listed companies was 19.4% (comparable to an OECD average of 20% OECD)2.

1.2.2. Gender equality in the labour market

Canada has one of the smallest gender employment gaps in the OECD but despite recent progress in this area, gender gaps remain. This remains a high priority for the government because figures show that advancing women’s equality in Canada has the potential to add $150 billion in incremental GDP in 2026 (or a 0.6% increase to annual GDP growth) (McKinsey Global Institute, 2017[2]). Employment rates for immigrant women are also higher than the OECD average and relatively close to women born in Canada (OECD, 2017[5]). However, the employment rate gap is particularly large between recent immigrant women (i.e. those in Canada for 5 years or less) and women born in Canada (58.5% for recent immigrant women aged 25-54 versus 82% for native-born women aged 25-54). The Government of Canada implements an overarching strategy, the Employment Equity Act, to improve gender equality in Canadian civil service employment. The government has also established hiring targets for women and men, based on the availability of women and men in the specific professional areas in the labour market. As of March 2016, women comprised 54.4% of the Federal public service workforce, while the Workforce Availability for Women was estimated at 52.5%.

Low employment rates are concentrated among women with young children, including single mothers (OECD (forthcoming), 2018[3]). (Moyser, 2017[4]) found that the gender employment gap is greater in localities with high childcare fees than in those with lower childcare costs in Canada. While family cash benefits – notably, the Canada Child Benefit - provide a source of funds for families to pay for childcare, they do not reduce the marginal cost of childcare (OECD (forthcoming), 2018[3]). Additionally, research shows that there can be a high penalty for flexibility in some high-wage occupations, showing that rewards to working long hours are an obstacle for closing the gender pay gap (Goldin, 2014[5]). Over time, the underrepresentation of women in top jobs accounts for a growing share of the gender gap, after taking into consideration the usual list of factors including education, occupation, industry, etc. (Canadian Institute for Advanced Research & Vancouver School of Economics, 2016[6])

Men’s take-up of parental leave in Canada is low with the exception of the province of Québec. Fathers often earn more than their partners, and it usually makes economic sense for the mother to take the bulk of the paid leave. In 2017, Canada introduced an option to extend the duration of Employment Insurance (EI) parental leave benefits from 12 months to 18 months at a lower income replacement rate.

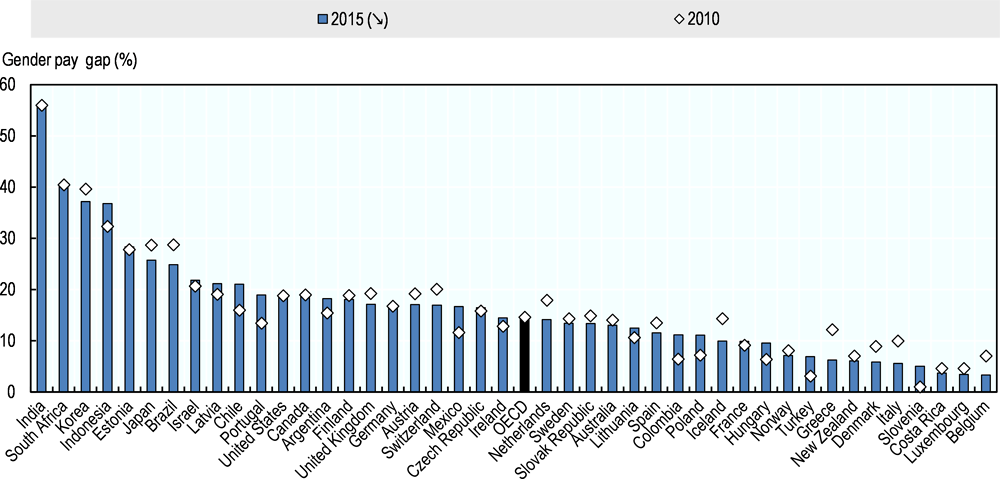

The gender wage gap in Canada persists and there is significant progress required. Examining the hourly rate, a measure which partially controls for the fact that men on average work more hours than women, shows that for every dollar of hourly wages a man working full-time earns in Canada, the average Canadian full-time female employee earns around 88 cents – placing Canada 15th out of 29 OECD countries based on the hourly gender wage gap (Government of Canada, 2018[7]). As one means to help overcome this, the Government of Canada has committed to introduce pay equity legislation in 2018 to ensure that employees in federally regulated workplaces (Government of Canada, 2018[7]). Although a direct impact of this legislation on the wage gap is not anticipated.

1.2.3. Women in education

In the education sphere, while women earn more bachelor’s degrees than men in Canada (60%), there are important and persistent gender differences in the subjects that young men and women study at college and university. There are lower proportions of Canadian women in STEM fields and in doctoral studies (OECD, 2017[1]), where Canadian men represent 67% of all STEM graduates (Government of Canada, 2018[8]). Conversely, Canadian women are disproportionately represented in the studies of health and education, accounting for about 80% of all graduates in Personal and Social Education (PSE). Moreover, OECD research shows that Canadian girls and women perform worse than their male peers in mathematics as teenagers (OECD, 2017[1]) and further research suggests that barriers to closing this STEM education gender gap are related to implicit bias and gender stereotypes, as well as to broader socio-economic, structural and cultural factors (Wells, 2018[9]). It appears that these gaps become greater as they move into adulthood; Canadian women also have lower scores in financial literacy (OECD, 2017[1]). These gender gaps in academic fields are reflected in the labour force and while women have made headway into certain male-dominated industries and occupations (those with 25% or less women in total employment), there is still a significant gender gap in many occupations. Women continue to be highly overrepresented in clerical, service, and health-related occupations in Canada, while men tend to be over overrepresented in craft, operator, and labourer jobs (Catalyst, 2017[10]). Male-dominated industries are especially vulnerable to masculine stereotypes which make it difficult for women to progress and excel, and male-dominated occupations generally pay more than female-dominated ones (Catalyst, 2017[10]), further entrenching the gender pay gap.

1.2.4. Gender-based violence

There is room for progress regarding tackling gender-based violence. According to Statistics Canada findings, women self-reported slightly more than 1.2 million violent victimisation incidents, representing 56% of all violent incidents, and women have a 20% higher risk of being victimised than men (Mahony, 2011[11]). SWC indicates that the economic costs of intimate partner violence against Canadian women is $4.8 billion annually and the economic costs of sexual assault/other sexual offences against Canadian women are estimated to be $3.6 billion annually. To tackle this, in 2017, SWC developed Canada’s first federal Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence.

1.2.5. Indigenous women

Indigenous women and girls are particularly vulnerable to gender inequalities in Canada. Indigenous women are over three times more likely than non-Indigenous women to report spousal violence. In fact, being Indigenous is a key risk factor on its own for experiencing violence (Status of Women Canada, 2017[12]). Work by the FEWO Committee has also highlighted a crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada. The current government has put this crisis at the heart of its agenda through the Speech of the Throne, which lays out Government's top priorities, and launched an inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Indigenous women also face particular challenges in educational attainment and labour market outcomes and access to justice. With regard to the gender wage gap, Indigenous women employed full-time earn 26 percent less than non-Indigenous men, and Indigenous women with a university degree earn 33 percent less (McInturff and Lambert, 2016[13]).

1.3. Government action in relation to gender equality: a historical context

Canada has undertaken a series of initiatives over the past half-century to promote gender equality. Key milestones over this period are set out in Box 1.1. Canada has also championed, among other countries, the development and adoption of the 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life (the 2015 Recommendation). In the past two decades, the Canadian approach to GBA+ has evolved into a modern, sophisticated and distinctive tool across the OECD for the mainstreaming of gender equality in public policy making (see Chapter 2).

Key milestones in gender equality can be categorised into three periods: Making Commitments (1970 - 1995), Setting the Stage (1995 - 2002) and Building Accountability (2003 - present):

Making Commitments (1970 - 1995)

-

1970: Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women investigated all matters pertaining to the status of women in Canada and was presented to the Parliament.

-

1971: The position of Minister responsible for the Status of Women was created.

-

1981: Canada ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

-

1982: The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guaranteeing equality rights was enacted.

-

1985: The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibiting gender-based discrimination was adopted.

Setting the Stage (1995 - 2002)

-

1995: Canada adopted the Beijing Declaration and the Platform for Action.

-

1995: The Government of Canada committed to conducting GBA on all future legislation, policies, and programmes and developed the Federal Plan for Gender Equality (1995-2000).

-

2000: The Agenda for Gender Equality, a five year government-wide strategy to accelerate the implementation of GBA, was adopted.

Building Accountability (2003 - present)

-

2004: The Standing Committee on the Status of Women (FEWO) was established in the House of Commons.

-

2009: The Office of the Auditor General published an audit of Gender-Based Analysis.

-

2009: Status of Women Canada and the central agencies developed a Departmental Action Plan on Gender-Based Analysis.

-

2011: Status of Women Canada rebranded GBA as GBA+ to factor in diverse identity circumstances into the analysis.

-

2015: The first-ever full Minister for the Status of Women was appointed.

-

2015: The Auditor General published an audit on Implementing Gender-Based Analysis.

-

2016: The application of GBA+ is made mandatory for all Memorandums to Cabinet and Treasury Board submissions.

-

2016: Status of Women Canada, the Privy Council Office and the Treasury Board Secretariat release the GBA+ Action Plan (2016-2020).

-

2017: Federal Budget 2017 was accompanied by a Gender Budgeting Statement for the first time.

Source: (Status of Women Canada,(n.d.)[14])

1.4. The arrival of a “feminist government” in 2015

In 2015, the newly elected Government signalled its wish to advance its commitment to feminism and feminist government in both domestic and foreign policy spheres2. Arising from this heightened focus on gender equality, diversity and inclusion, the systems and processes of policy making have been re-assessed and adapted with a view of enhancing their impact3. In the domestic sphere, the public commitment has been directly reflected within the mandates of all ministers who are expected to ensure diversity and gender parity in leadership positions. The federal Government took steps to boost the role and prominence of the federal gender apparatus4. Canada also released its first-ever Gender Statement as an integral part of the federal budget in 2017 and further advanced gender budgeting in 2018 (see Chapter 5). In the foreign policy sphere, the Government rolled out its first Feminist International Assistance Policy and it has put gender equality as one of the key priorities for Canada's G7 Presidency in 2018.

Securing leadership and commitment to gender equality at the highest political level is a vital ingredient for advancing gender equality, as stressed in the 2015 Recommendation. While it is soon to evaluate the impact of this commitment in the long run, in the short term, the OECD noted that the federal administration has been incentivised to demonstrate better results for gender equality. The high level political commitment has also increased the attention given to gender-based analysis across Departments. While independent civil society organisations and women's associations recognise that there remains important room for progress in several policy spheres, most such organisations recognise current efforts as crucial steps towards a supportive, enabling environment for gender equality policy.

The following section provides an overview of gender equality gains in recent years.

1.4.1. A government reflective of gender equality and diversity

The 2015 Recommendation promotes correcting gender inequalities through a coordinated, coherent approach to gender equality across all areas of public policy making, including in senior management and political representation. The Government of Canada has moved to correct gender imbalances in leadership appointments in the public sector. An example is the creation of Canada’s first gender-balanced Cabinet, together with the appointment of women to key ministerial portfolios such as Foreign Affairs, Justice and Labour. This has resulted in an increase of female ministers from 30.8% to 50% in Canada, well above the OECD average of 28% in 2017. Canada now ranks among the top countries across the OECD in terms of women in ministerial positions at the federal/national level5 (see Figure 1.4).The Prime Minister has also mandated all Ministers to ensure diversity and gender parity in leadership positions within their portfolios.

These high level political developments have put positive pressure across the federal administration to demonstrate better results on gender equality. An example comes from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) where the Chief of the Defence Staff set a target to increase the percentage of female staff from 15% to at least 25% by 2026 (see Box 1.2).

In this example, the use of behavioural insights (BI) was instrumental in developing a more gender balanced approach to recruitment. The use of BI has gained traction in many OECD countries to help institutions better design, implement, and enhance interventions across a range of topics (OECD, 2017[15]). In the area of gender equality, a growing body of evidence shows that BI can be helpful in reducing conscious and unconscious gender bias and stereotypes in governments, boardrooms and classrooms (Bohnet, 2016[16]). Given the high potential, the Impact and Innovation Unit could consider the application of BI in relation to gender equality and diversity a routine element of its portfolio. The Unit would also benefit from applying a gender lens, where possible, to the support that it provides to departments.

In November 2015, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) approached the Impact and Innovation Unit (IIU) – a unit in the PCO which experiments with new applying approaches to solve complex policy and programme challenges - for help with increasing the number of women staff. The Chief of the Defence Staff set a target to increase the percentage from the current 15% to at least 25% by 2026.

A research project was designed by the IIU to support this goal using behavioural insights (BI).The research looked at how BI could be applied to the recruitment process; recruitment marketing and communications and policies and guidelines and made 20 recommendations including:

-

Using gender-neutral job titles for all occupations;

-

Mandating gender disclosure on job application forms and including a third gender option;

-

Running randomised controlled trials to test different types of applicant correspondence and identifying the most effective message format;

-

Researching possible barriers in five key CAF policy areas: deployments and relocation; leave without pay; childcare support; long-term commitment/ability to resign; and culture/diversity.

Although this project focused on female recruitment, many of the findings apply to all CAF applicants, regardless of gender, and the recommendations have the potential to enhance the overall ease, effectiveness and success of the CAF’s recruitment process.

Source: (Government of Canada, 2016[17])

1.5. Sustaining the momentum on gender equality

The Government of Canada has invested in strengthening the federal gender apparatus at an unprecedented pace. For the purposes of this report, the federal gender apparatus can be described as institutions, policies, tools and accountability structures to promote gender equality and mainstreaming at the federal level.

From a historical perspective, the development of the gender equality apparatus at the federal level has not been linear. As in number of OECD countries, the gender apparatus in Canada has experienced rollbacks contingent on the shifts in power. For example, Status of Women Canada (SWC), which is the main federal government organisation mandated to coordinate policy with respect to women’s rights, has seen its mandate narrowed and budget significantly reduced throughout different administrations. A number of regional offices were also closed down. The absence of a legislative underpinning for SWC has reinforced the organisation’s vulnerability to the shifts in power (see Chapter 2).

The implementation of the Cabinet commitment to GBA+ has also been uneven across federal departments. Almost 15 years after the Cabinet commitment to GBA, the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) reported in 2009 that there was no evidence of the analysis being considered or documented in decision-making. A follow-up audit by the OAG in 2015 concluded that while SWC made progress in supporting the departmental implementation of gender-based analysis, analysis by departments was still missing, incomplete or inconsistent (see Chapter 3).

Recent developments go some way to address these challenges. The appointment of the first Cabinet-level Minister of Status of Women in November 2015 marks a step forward in terms of strengthening the federal gender apparatus, and ensures that gender equality and diversity considerations are systematically brought to the Cabinet table. In 2018, to further solidify and formalise the important role of SWC and its Minister – and in accordance with preliminary OECD recommendations in the preparation of this Report - the Federal Budget announced the introduction of departmental legislation to make SWC an official Department of the Government of Canada, almost fifty years after its establishment. The funding of SWC was also significantly restored and increased between 2015 and 2018. There is scope to further build on these advances to sustain them into the future, as discussed under Chapter 2.

A further development in Budget 2018 which aligned with preliminary OECD recommendations was the introduction of a Gender Results Framework (GRF) which establishes a whole-of-government tool to track how Canada is performing against key indicators relating to gender equality.

Another important development has been the creation of the Deputy Ministers' Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion (the Task Force) co-chaired by the Deputy Ministers of SWC and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The mandate of the Task Force is to examine and formulate advice on how to promote inclusion and implement the Government's commitment to a feminist domestic agenda. Its recommendations are due to be formulated by summer 2018. In the absence of an overarching federal government strategy in relation to gender equality, the recommendations of the Task Force will be instrumental in guiding future gender equality reforms, whose progress can be tracked using the recently introduced GRF.

Improvements in the implementation of gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) have also been implemented in recent years. Following the 2015 OAG audit of GBA+ and the subsequent recommendations of the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (FEWO), the government made mandatory since 2016 that evidence be provided to demonstrate that GBA+ has been considered and completed as necessary for all submissions brought before Cabinet and the Treasury Board (see Chapter 3). In the same year, GBA+ was integrated into the government's new Policy on Results (also see Chapter 3). In 2017, the Minister of Finance advised departments that all budget proposals should also be accompanied by a GBA+ assessment (see Chapter 5). Canada is now one the few OECD countries where gender analysis is mainstreamed within routine Cabinet policy process, in accordance with the 2015 Recommendation. Work is currently underway to make GBA+ mandatory for regulatory impact analysis. Early indications show that these initiatives have already yielded positive impacts on the GBA+ capacity within federal departments and agencies. In addition, since GBA+ became mandatory, more departments appear to be collecting gender-disaggregated data (Status of Women Canada, 2018). Looking ahead, there is scope to further embed GBA+ across the different phases of the policy cycle, from problem definition to evaluation and impact analysis. Chapter 3 examines in more detail how the achievements from this wave of reforms can be consolidated and built upon.

Important advances have also been made regarding accountability and monitoring structures for GBA+. These include giving the Privy Council Office (PCO) and the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) a stronger “challenge” function in relation to GBA+; introducing an annual GBA+ implementation Survey sent to Deputy Ministers by SWC; and a commitment to report to the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee on the implementation of GBA+.

Other strides in advancing the federal gender apparatus on the policy side include the launch of a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in 2016 as well as the adoption of Canada's first Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence in 2017. These developments address historical gaps in the federal governance processes for gender equality.

1.5.1. The role of gender equality strategies at federal and sub-national levels

Canada has a unique opportunity to reverse persistent gaps in gender equality. The establishment of a Gender Results Framework as part of Budget 2018 provides strong foundations upon which a commonly agreed upon strategy for gender equality and diversity can be built, in line with the 2015 Recommendation, to boost progress in Canada. Such a strategy would provide a policy umbrella under which gender mainstreaming and targeted initiatives meet to advance society-wide goals for gender equality. Indeed, the development of a gender equality strategy has become common practice across the OECD. Currently more than half of all OECD countries have national or federal multi-year gender equality strategies in place, although their implementation and effectiveness varies across countries (see e.g. Box 1.3).

Specifics in relation to a federal gender equality strategy

Development of a federal gender equality strategy would not be a new exercise for Canada. SWC published Canada's first Federal Plan for Gender Equality in 1995 in collaboration with 24 federal departments and agencies in response to the United Nations' call for member states to formulate a national plan to advance the situation of women. In 2000, SWC developed the second five year government-wide strategy to accelerate the implementation of GBA. These experiences have provided valuable lessons for future strategies. In particular, it has become clear that these strategies are most effective when there is buy-in from central agencies and line departments; identification of adequate resources; focus on achieving outcome oriented objectives; and the identification of clear lines of accountability at the highest political level.

A number of initiatives are underway at the federal level provide useful ground work for the development of an overarching gender equality strategy. This includes the recent investment in a new centre for Gender Diversity and Inclusion Statistics; the preparation of Diversity and Inclusion Charter led by the PCO; and the Gender Results Framework (GRF) introduced as part of Budget 2018 which lays out government's priorities for gender equality. The development of the GRF marked an important step towards strengthening transparency of and accountability for gender equality priorities in Canada.

A similar exercise by the Victorian Government in Australia has shown early indications of success. In 2015, the state government committed to achieving gender parity across all paid government board positions, with women’s representation standing at just 38% at the time. The following year the government launched its gender equality strategy, incorporating this goal as one of its priorities. The annual progress report for the strategy recorded progress against strategic priorities. The Victorian Government's gender equality strategy and related annual progress reports assisted transparency and accountability and helped the government make progress in relation to its gender equality commitments. As of 2018, 53% of paid public board positions were held by women (The Victorian Government, 2018[18]).

While the Canadian GRF is intended to become a whole-of-government tool to track gender equality results, the current commitment is to apply it to Budget 2018 and future budgets. There is scope to strengthen interlinkages with the on-going initiatives of SWC and PCO, and complement it with an implementation plan – in the context of the government's results and delivery agenda - so that there is further clarity among government and civil society stakeholders about:

-

Which institutional actors are accountable for progress in relation to different objectives in the GRF;

-

How the government's gender equality priorities are linked to the results and delivery frameworks of each department (see Chapter 3); and

-

How the government can maximise the impact of its gender mainstreaming tools (e.g., GBA+ in policies, budgets, regulations, procurement, etc.) to achieve the objectives in the GRF.

In rolling out an implementation strategy for the GRF, the government's Action Plan for Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) for 2016-2020 puts forward a comprehensive and sophisticated governance plan to implement GBA+ and can provide a useful foundation. Moving forward, there are opportunities to strengthen understanding and knowledge on gender gaps across federal departments and their policy areas, highlighted by federal departments as a common barrier to full implementation of GBA+. There are also opportunities to clarify the gender outcomes that are being sought through the use of GBA+ and gender budgeting (although some individual departments have taken notable steps in this area in recent years).

There are promising examples of gender equality implementation strategies across the OECD that Canada may draw inspiration from. Further details on the content and governance processes for each of these strategies are presented in Box 1.3. All of these strategies adopt a 'dual approach' whereby targeted initiatives are coupled with gender mainstreaming requirements in line with the 2015 Recommendation.

Finland

In May 2016, Finland launched its Government Action Plan for Gender Equality 2016 – 2019, consisting of an overarching gender equality strategy of around thirty measures covering all ministries. The strategy contributes to meeting international commitments laid out in the United Nation’s Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the European Council’s Istanbul Convention, as well as the government’s programme for the promotion of equality between women and men.

The Action Plan was built on the directions given by experts and key stakeholders consulted during the preparation process and it was later finalised in collaboration with the ministries. It offers concrete actions and realistic goals articulated around six areas: labour market equality, reconciliation of work, family and parenthood, gender equality in education and sports, intimate partner violence and violence against women, men’s wellbeing and health and decision-making that promotes gender equality. For each of these areas, the strategy sets objectives to be achieved during the government’s term and others for the long-term. Besides the specific thematic measures that fall into its respective ministry, the plan also includes measures to ensure that all ministries assess the gender impacts of their activities and take them into account in their decision-making.

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health is responsible for the coordination of the work related to the Action Plan. However, the Action Plan requires extensive inter-ministerial cooperation and commitment. A working group has been appointed to support and monitor the implementation of the plan and report to government.

Spain

In 2014, the Spanish Government launched the government’s Strategic Plan for Equal Opportunities 2014-2016. The strategy was developed with the aim of ensuring a high degree of consensus and viability. To this end, the plan drew on work by the Spanish Women’s Institute and existing European strategies such as the EU’s Strategy for Equality between Women and Men 2010-2015 and Europe 2020 Strategy, as well as reports and proposals from the Equality Commissions of both the Spanish Congress and Senate. Objectives and measures were set in collaboration with line ministries. The Plan was also sent to the Council for Women’s Participation for final consultation.

The Strategic Plan for Equal Opportunities 2014-2016 is articulated around seven action axes: labour market and gender pay gap equality, balance between personal, family, and work life and co-responsibility in family responsibilities, eradication of violence against women, women’s participation in political life and economical and social spheres, education, development of gender equality actions in sectorial politics and mainstreaming gender in the Government’s policies and actions.

In each of the seven axes, the strategy provides an overview of the situation and sets specific objectives, lines of action and planned measures. For some axes, special measures targeting rural and especially vulnerable women were introduced.

The plan includes a clear governance scheme, based on a classification of three disparate types of agents:

-

Responsible Agents: Each of the Ministerial departments and in particular the Ministry for Health, Social Affairs and Equality are responsible for the implementation of the plan in its competency areas.

-

Support Agents: Equality Units of the Ministries are responsible for facilitating and ensuring line ministries execute the plan’s measures.

-

Coordination Agents: The General Authority for Equal Opportunities and the Women’s Institute are responsible for the preparation, monitoring and evaluation of the Plan, as well as coordinating the Equality Units and general plan coordination.

The Plan also commits to developing an Evaluation Program which would include a selection of indicators corresponding to the Plan’s objectives, to allow for better monitoring, assess the level of implementation and evaluate the final results.

Australia, Government of Victoria

In 2016, the State Government of Victoria launched Safe and Strong: A Victorian Gender Equality Strategy, which sets out founding reforms that lay the groundwork and set a new standard for action by the Victorian Government on reducing violence against women and delivering gender equality. Safe and Strong has been informed by the diverse voices and experiences of more than 1,200 Victorians through consultations with specific groups and communities across a wide range of sectors and industries, including Indigenous Victorians, people with a disability, seniors, young people, culturally diverse communities and LGBTI Victorians. The Strategy provides a needs analysis and draws on global evidence of what works in gender equality. The Strategy lays out long-term outcomes that the Victorian Government aspires to reach and its commitment to measure and track progress through an outcomes framework.

Sources: (Government of Finland, 2016[19]); (Government of Spain, 2014[20]); (The Victorian Government, 2018[18])

Specifics in relation to a pan-Canadian gender equality strategy

Canada has a broad range of longstanding international gender-related commitments, including CEDAW, the SDGs, the Beijing Platform for Action and OECD Gender Recommendations. There is scope to complement these external commitments with an over-arching Canada-specific strategy based on the gender equality and inclusion priorities that are most relevant, and that can feed most directly into federal policy making. Indeed, in the concluding observations of the latest periodic reports of Canada on the implementation of CEDAW, the Committee expressed concern about “the absence of a comprehensive national gender equality strategy, policy and action plan addressing the structural factors that cause persistent gender inequalities.” As a result, the Committee recommended that Canada “develops a comprehensive national gender strategy, policy and action plan addressing the structural factors that cause persistent inequalities” (United Nations, 2016[21]). Similar concerns regarding the absence of a national strategy were raised by civil society organisations6 in reports submitted to the Committee (OXFAM Canada, 2017[22]); (Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action (FAFIA), 2016[23]).

In the context of Canada's constitutional principles and federalism, a pan-Canadian strategy could entail a set of shared priorities, objectives and commonly agreed indicators on gender. A gender equality strategy could also roll out a governance structure and a common monitoring framework. It would recognise the prerogative of different levels of government to design their own policies while advancing shared priorities.

The development of a pan-Canadian gender equality strategy should draw upon examples of pan-Canadian strategies developed/being developed in other policy sectors such as environmental protection and early learning and childcare (see Box 1.4). Other recent examples include the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Declaration on Public Sector Innovation and the National Strategy for Financial Literacy.

Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change

Over the coming year federal, provincial and territorial governments will work collaboratively through a new working group established under the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment and through innovation Ministers to identify and develop appropriate ways to measure progress in the Pan-Canadian Framework, including through use of indicators which draw on existing best practices. Future reports will also identify policy outcomes, track progress using indicators against objectives, and provide recommendations on new opportunities for collaboration or expanded areas of work.

The implementation of the Pan-Canadian Framework is a collaborative effort and shared responsibility of federal, provincial and territorial governments. A governance structure has been established to support intergovernmental coordination on Pan-Canadian Framework implementation and reporting. Nine FTP Ministerial Tables are responsible for coordinating Pan-Canadian Framework actions that fall within their respective Ministerial Portfolios.

A Federal-Provincial-Territorial Coordinating Committee of Experts has been established to develop the annual Synthesis Report to First Ministers that integrates Pan-Canadian Framework related input from the FTP Ministerial Tables.

The Intergovernmental Affairs Deputy Minister plays a key role in finalising and delivering this annual report to the First Ministers.

In order to avoid duplication with provincial and territorial reporting mechanisms, this work will build on existing climate change reporting across governments including drawing on existing indicators and best practices.

Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework

On June 12, 2017, Federal, Provincial and Territorial Ministers Responsible for Early Learning and Child Care agreed to a Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. The new Framework sets the foundation for governments to work towards a shared long-term vision where all children across Canada can experience the enriching environment of quality early learning and child care. The guiding principles of the Framework are to increase quality, accessibility, affordability, flexibility and inclusivity in early learning and child care.

Governments are to work together, recognising that provinces and territories have the primary responsibility for the design and delivery of early learning and child care systems. Each provincial and territorial government determines its own priorities for early learning and child care and the Framework provides flexibility on how provinces and territories will meet objectives defined in the Framework.

Governments are to report annually on progress made in relation to the Framework and the impact of federal funding, while reflecting the priorities of each jurisdiction in early learning and child care.

Source: (Government of Canada, 2017[24])

Some civil society stakeholders noted that the 1967 Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada could provide a useful starting point for discussions around a pan-Canadian strategy for gender equality. The Royal Commission was established at a moment where women's rights issues were to the forefront nationally and internationally, and reflected a widespread sense of urgency to take action. Elements of the current international discourse on gender equality, and on empowerment of women and girls, are similarly in tune with the agenda of feminist reform within Canada. Against this background, it may be timely for the federal government to open a nation-wide dialogue about how gender inequality and inclusion can be addressed in a coordinated way.

Moving forward, in the context of Canada's stated commitment to gender equality and its results and delivery agenda, the OECD suggests that Canada builds on positive steps it has taken recently by establishing a Gender Results Framework, and use this framework as a foundation for:

-

The development of an overarching gender equality strategy at the federal level, with specific targets, clear allocation of roles, resources and lines of accountability for the whole-of-government, and an accompanying implementation plan and a data strategy. “Anchoring” and aligning this strategy with the results and delivery agenda of the Government and each department (e.g. mandate letters, Results and Delivery Charters, departmental results frameworks) could maximise its effective implementation. (see Recommendation 9)

-

Engagement with Federal, Provincial and Territorial Governments to work towards a pan-Canadian approach and strategy to gender equality, and to support Canada in implementing its international commitments such as CEDAW and SDGs. The impact of such an approach could be boosted by aligning policy objectives developed at Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) levels, while respecting the autonomy and flexibility of FPT governments in designing their own policies.

This twin-tracked approach clarifies the overarching gender equality objectives for government as well as civil society and allows Canada to address gender inequalities from a holistic and people-centred perspective. This in turn helps improve policy prioritisation as well as transparency and accountability. There is also the potential for enhanced dialogue between the FPT levels of government, facilitating improved policy coherence and a platform to share good practices.

References

[54] Andalusian Regional Government Administration (2014), PROGRESS IN THE ANDALUSIAN GRB INITIATIVE: GENDER AUDITS, https://www.wu.ac.at/fileadmin/wu/d/i/vw3/Session_3_Cirujano_Gualda_Romero.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[48] Australian Government((n.d.)), National Women's Alliances | Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2018, https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/grants-and-funding/national-womens-alliances (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[46] Batliwala, S., S. Rosenhek and J. Miller (2013), “WOMEN MOVING MOUNTAINS: COLLECTIVE IMPACT OF THE DUTCH MDG3 FUND HOW RESOURCES ADVANCE WOMEN'S RIGHTS AND GENDER EQUALITY”, https://www.awid.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Women%20Moving%20Mountains.pdf.

[52] Bochel, H. and A. Berthier (2018), SPICe Briefing: Committee witnesses: gender and representation, https://sp-bpr-en-prod-cdnep.azureedge.net/published/2018/2/27/Committee-witnesses--gender-and-representation/SB%2018-16.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[16] Bohnet, I. (2016), What works: Gender Equality by Design, Harvard University Press.

[23] Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action (FAFIA) (2016), Because its 2016! A National Gender Equality Plan, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/CAN/INT_CEDAW_NGO_CAN_25417_E.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2017).

[6] Canadian Institute for Advanced Research & Vancouver School of Economics (2016), Earnings Inequality and the Gender Pay Gap, http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/nfortin/Fortin_EarningsInequalityGenderPayGap.pdf.

[10] Catalyst (2017), Women In Male-Dominated Industries And Occupations, http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/women-male-dominated-industries-and-occupations.

[62] Congressional Budget Office (2016), CBO's 2016 Long-Term Projections for Social Security: Additional Information, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/52298-socialsecuritychartbook.pdf.

[59] Downes, R., L. Von Trapp and S. Nicol (2016), “Gender budgeting in OECD countries”, OECD Journal on Budgeting 3, http://www.oecd.org/gender/Gender-Budgeting-in-OECD-countries.pdf.

[27] EIGE (2018), Spain – Structures, http://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/countries/spain/structures.

[51] European Parliament (2016), Report on Gender Mainstreaming in the work of the European Parliament - A8-0034/2016, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=REPORT&reference=A8-2016-0034&language=EN (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[50] European Parliament (2003), European Parliament resolution on gender mainstreaming in the European Parliament (2002/2025(INI)), http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P5-TA-2003-0098+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN.

[29] Flumian, M. (2016), “What Trudeau’s committees tell us about his government | Institute on Governance”, Institute on Governance, https://iog.ca/research-publications/publications/what-trudeaus-committees-tell-us-about-his-government/ (accessed on 21 January 2018).

[5] Goldin, C. (2014), “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter”, American Economic Review, Vol. 104/4, pp. 1091-1119.

[8] Government of Canada (2018), Budget 2018: Equality + Growth, A Strong Middle Class, https://www.budget.gc.ca/2018/docs/plan/budget-2018-en.pdf.

[7] Government of Canada (2018), Budget Plan + Growth, https://financebudget.azurewebsites.net/2018/docs/plan/chap-01-en.html?wbdisable=true.

[44] Government of Canada (2018), Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada - Canada.ca, https://www.canada.ca/en/innovation-science-economic-development.html.

[33] Government of Canada (2018), Mandate Letter Tracker: Delivering results for Canadians, https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/campaigns/mandate-tracker-results-canadians.html (accessed on 10 February 2018).

[38] Government of Canada (2018), Policy on Results, https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=31300 (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[57] Government of Canada (2017), Budget 2017: Building a Strong Middle Class, https://www.budget.gc.ca/2017/docs/plan/budget-2017-en.pdf.

[45] Government of Canada (2017), Fact Sheet: It’s time to pay attention, http://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/violence/strategy-strategie/fs-fi-3-en.html.

[24] Government of Canada (2017), Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework - Canada.ca, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/early-learning-child-care/reports/2017-multilateral-framework.html (accessed on 11 December 2017).

[34] Government of Canada (2017), Results and Delivery in Canada: Building on momentum, http://www.fmi.ca/media/1200856/results_and_delivery_building_momentum_october_2017.pdf.

[56] Government of Canada (2016), Fall Economic Statement 2016, https://www.budget.gc.ca/fes-eea/2016/docs/statement-enonce/fes-eea-2016-eng.pdf.

[17] Government of Canada (2016), Increasing Recruitment of Women into the Canadian Armed Forces.

[41] Government of Canada((n.d.)), Charter Statements - Canada's System of Justice, 2018, http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/charter-charte/index.html (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[43] Government of Canada((n.d.)), Employment Insurance Service Quality Review Report: Making Citizens Central, 2017, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/ei/ei-list/reports/service-quality-review-report.html.

[19] Government of Finland (2016), Government Action Plan For Gender Equality 2016–2019, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/79305/03_2017_Tasa-arvo-ohjelma_Enkku_kansilla.pdf?sequence=1.

[60] Government of Iceland((n.d.)), Gender Budgeting, 2018, https://www.government.is/topics/economic-affairs-and-public-finances/gender-budgeting/ (accessed on 16 May 2018).

[20] Government of Spain (2014), Plan Estratégico de Igualdad de Oportunidades 2014-2016, http://www.inmujer.gob.es/actualidad/PEIO/docs/PEIO2014-2016.pdf.

[47] Government of Sweden (2014), Sweden's follow-up of the Platform for Action from the UN's, https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/b2f5cc340526433f8e33df3024d510e3/swedens-follow-up-of-the-platform-for-action-from-the-uns-fourth-world-conference-on-women-in-beijing-1995---covering-the-period-between-20092014.

[65] Government of Sweden (2007), Moving Ahead: Gender budgeting in Sweden, http://store1.digitalcity.eu.com/store/clients/release/AAAAGNJH/doc/gender-budgeting-in-sweden_2007.09.29-12.22.48.pdf.

[53] House of Commons Canada (2008), Committee Report No. 9 - FEWO (39-2) - House of Commons of Canada, http://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/39-2/FEWO/report-9/.

[26] House of Commons Canada (2007), Report of the Standing Committee on the Status of Women: The impacts of funding and program changes at Status of Women Canada, http://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/391/FEWO/Reports/RP2876038/feworp18/feworp18-e.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2018).

[49] House of Commons Canada((n.d.)), FEWO - About, 2018, https://www.ourcommons.ca/Committees/en/FEWO/About (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[36] IMF (2017), Gender Budgeting in G7 Countries, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2017/05/12/pp041917gender-budgeting-in-g7-countries.

[11] Mahony, T. (2011), “Women and the Criminal Justice System”, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-503-X, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2010001/article/11416-eng.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[13] McInturff, K. and B. Lambert (2016), Making Women Count: The Unequal Economics of Women's Work, | Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, OXFAM Canada, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/making-women-count-0 (accessed on 01 January 2018).

[2] McKinsey Global Institute (2017), The power of parity: Advancing women’s equality in Canada, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality/the-power-of-parity-advancing-womens-equality-in-canada (accessed on 16 May 2018).

[4] Moyser, M. (2017), Women and Paid Work, Statistics Canada, March, available online at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14694-eng.htm.

[15] OECD (2017), Behavioural Insights and Public Policy: Lessons from Around the World., OECD Publishing.

[28] OECD (2017), Building an inclusive Mexico : Policies and Good Governance for Gender Equality, OECD Publishing.

[42] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, http://www.oecd.org/gov/Recommendation-Open-Government-Approved-Council-141217.pdf.

[1] OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281318-en.

[32] OECD (2016), Open Government The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing.

[31] OECD (2016), “Open Government: The Global Context and The Way Forward”, http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/4216481e.pdf?expires=1516890637&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=36020513E75CAF56257B41F9DC2A3AFC (accessed on 25 January 2018).

[25] OECD (2015), “Delivering from the Centre: Strengthening the role of the centre of government in driving priority strategies”, https://www.oecd.org/gov/cog-2015-delivering-priority-strategies.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2018).

[37] OECD (Forthcoming), Budgeting in Austria.

[39] OECD (Forthcoming), Budgeting Outlook 2018.

[58] OECD (Forthcoming), Budgeting Practices and Procedures Dataset.

[64] OECD (Forthcoming), Governance Guidelines for Gender Budgeting.

[3] OECD (forthcoming) (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Canada, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[30] Office of the Auditor General Canada (2016), Implementing Gender-Based Analysis, http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201602_01_e_41058.html (accessed on 24 January 2018).

[55] Office of the Auditor General of Canada((n.d.)), The Environment and Sustainable Development Guide, 2018, http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/meth_lp_e_19275.html (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[22] OXFAM Canada (2017), Feminist Scorecard 2017: Tracking government action to advance women’s rights and gender equality, http://www.oxfam.ca (accessed on 11 December 2017).

[35] Schratzenstaller, M. (2014), The implementation of gender responsive budgeting in Austria as central element of a major budget reform, https://www.wu.ac.at/fileadmin/wu/d/i/vw3/Session_4_Schratzenstaller.pdf.

[63] Sharp, R. and R. Broomhill (2013), A Case Study of Gender Responsive Budgeting in Australia, https://consultations.worldbank.org/Data/hub/files/grb_papers_australia_updf_final.pdf.

[12] Status of Women Canada (2017), It's Time: Canada's Strategy To Prevent and Address Gender-based Violence, Government of Canada, http://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/violence/strategy-strategie/GBV_Fact_sheets_2.pdf (accessed on 01 January 2018).

[14] Status of Women Canada((n.d.)), The History of GBA+ Domestic and International Milestones.

[61] Swedish Fiscal Policy Council (2016), Finanspolitiska rådets rapport 2016, http://www.finanspolitiskaradet.com/download/18.21a8337f154abc1a5dd28c15/1463487699296/Svensk+finanspolitik+2016.pdf.

[18] The Victorian Government (2018), Safe and Strong: A Victorian Gender Equality Strategy. Achievements Report Year One, https://www.vic.gov.au/system/user_files/Documents/women/1801009_Safe_and_strong_first_year_report_summary_10_%C6%92_web.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2018).

[40] UK National Audit Office (2016), Sustainability in the spending review, https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Sustainability-in-the-Spending-Review.pdf.

[21] United Nations (2016), “Concluding observations on the combined eighth and ninth periodic reports of Canada*”, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N16/402/03/PDF/N1640203.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 11 December 2017).

[9] Wells, M. (2018), Closing the Engineering Gender Gap, https://www.design-engineering.com/features/engineering-gender-gap/.

Notes

← 1. OECD calculations based on official websites of Provincial and Territorial legislatures.

https://www.leg.bc.ca/wotv/pages/representation-today.aspx http://www.legassembly.gov.yk.ca/members/index.html http://www.ontla.on.ca/web/members/members_current.do?locale=en&ord=Riding&dir=ASC&list_type=all_mpps

https://www.assembly.ab.ca/lao/mla/SeatPlan.pdf

https://nslegislature.ca/members/profiles

http://www.assnat.qc.ca/en/deputes/

http://www.assembly.nu.ca/members/mla

http://www.legassembly.sk.ca/mlas/

https://gov.mb.ca/legislature/members/mla_list_alphabetical.html

http://www.assembly.pe.ca/current-members

http://www1.gnb.ca/legis/bios/58/index-e.asp

http://www.assembly.gov.nt.ca/members

http://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/transition/tab_2_1-en.html

← 2. OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281318-en

← 3. http://www.canadabeyond150.ca/themes-methods-en.html

← 4. The federal gender apparatus can be described as institutions, policies, tools and accountability structures to promote gender equality and mainstreaming at the federal level.

← 5. Along with France, Iceland, Sweden and Slovenia

← 6. Feminist Alliance for International Action highlights ''the need for a comprehensive plan is underscored by the fact that Canada has no national machinery for the advancement of women. Federal, provincial and territorial governments have different mechanisms; British Columbia has none, and some have assigned little authority or resources to this portfolio. Discussion among governments on women's equality issues takes place at meetings of Status of Women Ministers, but there is no formal co-ordination." OXFAM Canada also recommends implementing the CEDAW Committee’s 2016 recommendation for Canada to develop a comprehensive national gender equality strategy, policy and action plan that addresses the structural factors causing inequality.