Chapter 3. Country profiles: Institutional mechanisms for policy coherence

This chapter presents country profiles from 19 countries (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Japan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland) describing practices and institutional mechanisms that are relevant for enhancing policy coherence for sustainable development. It draws on country responses to a survey sent to all members of the informal network of national focal points for policy coherence (including all OECD member countries), organised with questions corresponding to the eight building blocks identified in Chapter 2 and considered central to coherent policy making. The chapter highlights country practices and mechanisms with a view to sharing experiences and improving mutual understanding in efforts to achieve more coherent SDG implementation. It concludes with three contributions by member institutions of the Partnership for Enhancing Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development presenting brief profiles of Nepal and Pakistan at the national level and a case study on vertical policy coherence in Brazil.

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include an internationally agreed target (SDG 17.14) that calls on all countries to enhance policy coherence for sustainable development (PCSD) as a means of implementation that applies to all SDGs. Countries are increasingly recognising the need to break out of institutional and policy silos to fully realise the benefits of synergistic actions and effectively manage unavoidable trade-offs across SDGs. The proposed global indicator to measure progress on the PCSD target aims to capture the “number of countries with mechanisms in place to enhance policy coherence for sustainable development”. There is currently a need for more clarity about the type of mechanisms that can support institutional and policy coherence in implementing highly interconnected SDGs, as well as for developing practical guidance on how to achieve and track progress on SDG 17.14 at the national level.

This chapter aims to respond to this need by highlighting institutional mechanisms (structures, processes and methods of work) for enhancing policy coherence in SDG implementation with examples drawn from current country experiences. It presents country profiles from 19 countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Japan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland, with information organised according to the eight building blocks set out in Chapter 2. Each country profile is based on information gathered from the country’s response to the 2017 Survey on applying the eight building blocks of PCSD in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, which was sent out to the members of the informal network of national focal points for policy coherence. This chapter also includes three contributions by NGO Federation of Nepal (NFN), Social Policy and Development Centre (SPDC), and Núcleo Girassol (Universidade Federal Fluminense) which are members of the Partnership for Enhancing Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development, presenting brief country profiles of Nepal and Pakistan, and a case study on vertical policy coherence in Brazil respectively.

The chapter provides an overview of different efforts, mechanisms and tools to enhance policy coherence for sustainable development. There is no single blueprint. It is up to each country to determine its institutional mechanisms for promoting policy coherence according with its national circumstances. Through the mutual exchange of experiences and discussions on what works and what does not, countries can identify solutions and strengthen efforts to ensure a coherent implementation of the SDGs. Going forward, this work aims to: 1) inform the update of the 2010 OECD Council Recommendation on good institutional practices for promoting policy coherence for development; 2) provide analytical input to the thematic reviews at the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development; and 3) provide input for developing the methodology for the global indicator for SDG Target 17.14.

Austria

New directives aimed at incorporating the SDGs into the programmes of all ministries helps to strengthen the commitment to policy coherence across the government. In January 2016 the Austrian Council of Ministers instructed all ministries to integrate the SDGs into their relevant programmes and strategies, and to develop new action plans for coherent implementation of the 2030 Agenda where necessary. Thus, line ministries share responsibility for achieving the SDGs in their respective areas (Statistik Austria, 2018[1]). Outline 2016 - Contributions to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by the Austrian Federal Ministries, published in March 2017, is evidence of political commitment and outlines national responsibilities and policy processes for SDG implementation (Bundeskanzleramt Österreich, 2017[2]). The relevance of policy coherence is thus systematically recognised in SDG implementation, albeit with a particular focus on the international level. An explicit commitment to PCSD is also articulated in the current Three Year Programme on Austrian Development Policy 2016-2018 (Federal Ministry for Europe, 2016[3]). An even stronger commitment will be incorporated in the next Three Year Programme 2019-2021 (OECD, 2017[4]).

A newly installed interministerial working group takes domestic and international objectives related to the SDGs into consideration to identify potential trade-offs. An interministerial working group co-chaired by the Federal Chancellery and Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been established to co-ordinate activities through information sharing and supports implementation of the SDGs as well as their promotion within society (Bundeskanzleramt Österreich, 2017[2]). SDG focal points from all ministries participate in its regular meetings, exchange information on different policy objectives and are thus able to identify trade-offs and synergies. At these meetings, the international perspective of PCSD is addressed. The Austrian Development Agency’s (ADA) work is guided by seven principles (Ownership; Do-no-harm; Equity, equality and non-discrimination; Participation and inclusion; Accountability and transparency; Empowerment; and Sustainability) to foster coherent policies and avoid unintended negative effects.

Belgium

Renewed political commitment at all levels and a long tradition towards sustainable development facilitate horizontal and vertical coherence. The commitment to sustainable development (SD) is enshrined in the Belgian constitution since 2007, to which the federal state, communities (Flemish, French and German-speaking) and regions (Wallonia, Flanders and Brussels-Capital) must contribute. Implementation of the 2030 Agenda relies on a variety of existing SD strategies adopted by respective levels of government. At the federal level, a 2050-time horizon Vision for SD was adopted in 2013 encompassing 55 long-term objectives, a set of indicators and federal plans (IFDD, 2018[5]). The federal strategy has been implemented through a five-year policy learning cycle (“report-plan-do-check-act”) since 1997. At the regional level, key strategic frameworks include: the second Walloon Strategy for SD, approved in 2016; Flemish Vision 2050 – a long-term strategy for Flanders (Box 3.1); the Regional SD plan adopted by the Brussels-Capital Region; and the second regional development plan of the German-speaking Community. Reflections are underway to adapt existing commitments and the institutional architecture for policy coherence for development to the new realities of the 2030 Agenda.

A new overarching strategic framework serves as a platform for the Belgian federal system to pursue the 2030 Agenda and SDGs coherently. The first National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS), approved in 2017, provides the umbrella for the main governmental actors at both federal and federated levels to combine their efforts to achieve the SDGs in a Belgian context. Priority themes include: sustainable food, sustainable building and housing, sustainable public procurement, means of implementation, awareness-raising and contributions to follow-up and review. There is a common understanding among the NSDS signatories of the need for strengthened forms of co-ordination. The NSDS envisages a national 2030 Agenda implementation report to be issued jointly to all parliaments twice per government term (Kingdom of Belgium, 2017[6]).

An institutional framework promoting transversal work and participation at all levels enhances policy coherence. The Interministerial Conference for Sustainable Development (IMCSD) – composed of federal, regional and community ministers responsible for SD and development co-operation – has been revitalised as the central co-ordination mechanism for SDG implementation. The Inter-departmental Commission for Sustainable Development (ICSD), chaired by the Federal Institute for SD, provides for co-ordination between federal government departments. Different mechanisms also support co-ordination within each level of power and help engage different societal groups, such as the multi-stakeholder advisory Federal Council for Sustainable Development and the Advisory Council for Policy Coherence for Development (PCD). The institutional framework should enable the country to ensure an effective interface between local, sub-national, national and international implementation, and honour its commitment to PCSD, provided that it allows for cross-sectoral action and enhanced capacities to assess the transboundary impact of domestic policies (Box 3.1).

At the federal level

The new Comprehensive Approach strategy note, designed jointly by the Foreign Ministry, the Ministry for Development Cooperation and the Ministry of Defence, sets out a coherent approach to Belgian foreign policy. Conscious that complex situations generally raise challenges of very different natures (political, social, ecological, economic, military, security), the Comprehensive Approach embeds development with in diplomacy, defence and the rule of law. The strategy note builds on the approach already developed for the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs (SDG 16 in particular), and helps to progressively break down the different policy silos. Recent examples include Belgian contributions to peace and stability in Iraq and in the Sahel, where permanent dialogue, evaluation and adjustment of Belgium’s approach requires all departments concerned to collectively set the overarching priorities and adjust mutual efforts.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has adjusted its internal organisational structure in light of synergies and created a department competent for environment and climate that covers both development and multilateral aspects of this theme.

At the regional level

Vision 2050 in Flanders has identified seven transition priorities as flagship initiatives cutting across policy areas and requiring involvement of different ministers: the circular economy; smart living; industry 4.0; lifelong learning and a dynamic professional career; healthcare and living together in 2050; transport and mobility; and energy. The focus is on addressing regional challenges and achieving significant progress in key opportunity areas rather than trying to implement an all-encompassing approach. This makes the transition towards a sustainable path more manageable and concrete for stakeholders and public opinion while facilitating co-operation amongst departments and, ultimately, faster and better results. It also facilitates continuous learning amongst all stakeholders, although respective responsibilities for results could be clearer.

Source: OECD (2017[7]).

Czech Republic

A renewed umbrella framework and commitment to policy coherence enables the government to pursue 2030 Agenda coherently. The strategy Czech Republic 2030, with sustainable development and wellbeing at its core, uses PCSD as a guiding principle for national, regional and local policies (Office of the Government of the Czech Republic, 2017[8]). The Government Council for Sustainable Development (GCSD), chaired by the First Deputy Minister and Minister for the Environment since April 2018, plays an important role in promoting PCSD across the government. The commitment to PCSD is also reaffirmed in the Development Cooperation Strategy of the Czech Republic 2018-2030. Translating commitment into practice would be supported by greater awareness on PCSD and by fostering an administrative culture of cross-sectoral co-operation within the public service.

A co-ordinating body allows for a shared approach to sustainable development domestically and abroad. The SDG implementation process is led by the Ministry of Environment and supported by the Government Council for Sustainable Development (GCSD). The GCSD provides a platform for inter-sectoral policy co-ordination among central administrative authorities. Ministries and other stakeholders contribute to its work through nine thematic committees (Box 3.2). The establishment of a formal co-ordination mechanism among GCSD committees is being discussed, raising the possibility for the GCSD to arbitrate between committees and ministries to resolve any overlaps or inconsistencies in the formulation and implementation of policies (OECD, 2017[9]). An effective interface between the GCSD and the Council for Development Cooperation would support a unified approach to PCSD and help to ensure synergies between domestic and international actions the country has identified as a major challenge in DAC reviews (OECD, 2016[10]).

A monitoring and reporting system focused on priority areas, as well as synergies and trade-offs, will be instrumental in enhancing policy coherence. Czech Republic 2030 identifies six priority clusters: People and Society; Economy; Resilient Ecosystems; Regions and Municipalities; Global Development and Good Governance, which help in identifying thematic synergies, managing trade-offs and reporting coherently. A biannual analytical Report on the Quality of Life and its Sustainability will be submitted to the government, building on indicators operationalising the 97 specific goals outlined in Czech Republic 2030. GCSD committees are responsible for data collection and indicator preparation within their respective fields. The draft report will be prepared by the Sustainable Development Department of the Office of the Government and consequently be subject to consultations with relevant committees and approval by the GCSD before submission. The Czech Statistical Office plays a key role in providing relevant data and is responsible for co-ordination related to the global set of indicators (Office of the Government of the Czech Republic, 2017[11]).

In July 2015, the government of the Czech Republic tasked the prime minister with revising the 2010 national Strategic Framework for Sustainable Development. This process aimed to formulate key priority areas and long-term objectives for sustainable development and well-being, mainstream the SDGs into national policies, and identify opportunities and threats as well as global megatrends influencing the development of the Czech Republic.

In mid-2015 the prime minister invited all government advisory bodies and major CSO networks to send proposals for the country’s long-term development. Inputs were collected online via the Database of Strategies, a special application created for this opportunity operated by the Ministry of Regional Development. By 15 October 2015, 49 organisations and institutions had provided 172 inputs.

The Government Council for Sustainable Development (GCSD) team edited and evaluated the inputs. The National Network for Foresight, consisting of six academic institutions and think-tanks focusing on strategic management and foresight, supported their efforts. On the basis of their analysis using the DELPHI method, relevant inputs were selected and, through the similar added keywords, added to each input clustered into six key areas. The selected areas were presented at the Sustainable Development Forum in December 2015 and consulted with relevant GCSD committees.

A nearly two-year process of drafting of the Czech Republic 2030 strategy followed. This involved organisation of six roundtables (one for each key area), organisation of eight regional roundtables, two public hearings, consultations in both chambers of parliament and numerous consultations with experts across different sectors. Overall, around 500 experts and 100 different organisations participated in the process.

Source: OECD (2017[9]).

Estonia

The Sustainable Estonia 21 strategy is revitalising longstanding commitments for sustainable development and policy coherence. Adopted by Parliament in 2005, Sustainable Estonia 21 serves as strategic framework for achieving the SDGs (Estonian Government, 2005[12]). The Sustainable Development Commission launched a review of Sustainable Estonia 21 and its implementation mechanisms to make it compatible with the 2030 Agenda. With preparations for the new planning period starting in 2018, the SDGs will be integrated into the government’s sectoral and thematic strategies and action plans. Estonia has also committed to establishing an initial framework for policy coherence by 2020 (Government Office Republic of Estonia, 2016[13]).

Existing co-ordination mechanisms at all levels support policy coherence and integration. The Government Office Strategy Unit co-ordinates work on sustainable development at the central government level. It also co-ordinates other strategies (e.g. Estonia 2020, Estonia’s EU policy), putting it in a position to align priorities and ensure coherence across various horizontal planning documents. An interministerial working group comprising representatives from all ministries and Statistics Estonia supports implementation of Sustainable Estonia 21 and the SDGs, develops national sustainable development indicators and prepares the VNR. The Sustainable Development Commission, a non-governmental advisory umbrella organisation, monitors implementation of Sustainable Estonia 21. It meets four to five times a year to discuss strategic action plans before their adoption by the government and publishes focus reports with policy recommendations (OECD, 2017[14]). Coherence between sustainable sector-specific policies can be further enhanced by strengthening co-ordination mechanisms and going beyond information sharing and division of responsibilities (OECD, 2017[15]).

Impact assessments support coherence by requiring that economic, social and environmental aspects be taken into account in all strategic planning documents and EU positions. The impact assessments cover: social, including demographic impact; security and foreign policy; the economy; the living and natural environment; regional development; and the organisation of government institutions and local governments. In addition, a strategic environmental impact assessment (covering natural, social, economic and cultural environment) must be conducted when compiling strategic planning documents and local plans, in accordance with the Environmental Impact Assessment Act (OECD, 2017[14]).

Source: Government Office Republic of Estonia (2016[13]).

Finland

Political commitment at the highest level and a whole-of-government strategic framework put policy coherence at the forefront. The national 2030 Agenda implementation process is led by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). The Finland we want by 2050, adopted in 2014 and updated in 2016, aims at reconciling economic, social and environment imperatives. (National Comission on Sustainable Development, 2016[16]). The strategy provides a long-term strategic framework for a whole-of-society commitment to sustainable development. The government’s plan for the 2030 Agenda, submitted to the parliament in 2017, is the framework for implementation, national follow-up and review up until 2030. The plan focuses on two key areas: 1) a carbon-neutral and resource-wise Finland; and 2) a non-discriminatory, equal and competent Finland. It also outlines domestic and international commitments and makes an explicit commitment to policy coherence to support sustainable development (PMO Finland, 2017[17]). The development policy, which is an integral part of Finland’s foreign and security policy, includes priority areas based on the 2030 Agenda and SDGs: gender equality and the empowerment of girls and women; supporting economies in developing countries in creating jobs, sources of livelihood and well-being; democratic and functioning societies; better food security and access to water and energy; and the sustainability of natural resources (PMO Finland, 2016[18]).

Enhanced co-ordination across and within government underpins policy coherence and fosters policy integration. The Prime Minister’s Office co-ordinates national SDG implementation. An interministerial Coordination Network consisting of sustainable development focal points from each line ministry supports the co-ordination function of the PMO. The National Commission on Sustainable Development (NCSD), a prime minister-led multi-stakeholder forum, brings together the public and private sectors, CSOs, academia and municipalities and regions with the task of integrating sustainable development into Finnish policies, measures and everyday practices at different levels. The Development Policy Committee (DPC), a parliamentary body, is tasked with following up on SDG implementation from a development policy perspective, and with monitoring implementation of the government programme in compliance with development policy guidelines (PMO Finland, 2016[18]). Since the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, collaboration between these two committees is being intensified. Traditionally, policy coherence for development has been under the responsibility of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, with a thematic focus on issues such as food security, aid for trade, migration, tax and development, and peace and development (OECD, 2017[19]). With the 2030 Agenda, PCSD is becoming a shared responsibility for all governmental bodies.

Systematic and participatory follow-up and review enhance stakeholder engagement and policy coherence at all levels. Finland relies on a wide range of sources to build its evidence base and inform policy. These include scientific panels, think-tanks, research institutions, citizen engagement and an active civil society. Implementation of the 2030 Agenda will be reported on annually to the parliament as part of the government’s annual report. From 2017 onwards, each branch of government will provide information on steps taken to advance the 2030 Agenda. The DPC, which monitors and assesses implementation of Finland’s international development commitments, will play a key role in the follow-up and review of the global dimension of the national implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Finland is also developing a national follow-up system that enables stakeholder participation (Box 3.3). Finland has in place the key building blocks for ensuring a coherent implementation of the SDGs going forward.

Finland’s national follow-up and review system is anchored in the eight objectives of its long-term strategic framework. Policy making is linked to the eight objectives via ten indicator baskets, which in turn consist of four to five indicators and are connected to more than one objective. The baskets serve as the framework for discussions on interpretations and put a lens on entities that are relevant in terms of political decision making.

The indicators in each basket will be reviewed, interpreted and updated once a year by relevant authorities. The purpose is to assess the significance of the change in the indicator value from the perspective of sustainable development. This is followed by a public, multi-stakeholder dialogue where anyone can present different interpretations and introduce new information. This process helps to inform political decision making.

The open discussion takes place on the Prime Minister’s Office sustainable development website (kestavakehitys.fi/seuranta) on a rolling basis to discuss a different basket each month. After the update of all baskets, the NCSD and the PMO organise an annual event on the state and future of sustainable development. The event coincides with the parliament discussion on the government’s annual report to the parliament.

Source: PMO Finland (2017[21]).

Source: Prime Minister’s Office, Finland.

Germany

A unified strategy with commitment at the highest level promotes PCSD. The German Sustainable Development Strategy, adopted by the cabinet in January 2017, is the key policy instrument for implementation of the 2030 Agenda under the direct aegis of the Federal Chancellery. The strategy bundles various policy areas to achieve greater coherence in light of the large number of systemic interdependencies and contains the ambition to use the 2030 Agenda as an opportunity to increase efforts for policy coherence, with particular reference to SDG 17.14 (German Federal Government, 2016[22]). It thus provides a good basis for further enhancing Germany’s sustained commitment to PCSD (OECD, 2015[23]).

The centre of government promotes PCSD through an issues-based approach backed by all ministries. The State Secretaries’ Committee (SSC) is the central steering institution of the Sustainable Development Strategy. It is composed of representatives from all ministries and chaired by the Head of the Federal Chancellery. Germany’s whole-of-government approach also requires all ministries to participate actively in the SD Working Group (UAL-AG), which prepares the meetings of the SSC and helps to implement and further develop the strategy. The SSC meets regularly to address important cross-cutting or sectoral issues on a consensus basis, e.g. setting a new political framework for topics or announcing concrete actions. While Germany has implemented many mechanisms after its first VNR, such as the establishment of SD co-ordinators in each ministry, it could go further to harness the potential of societal stakeholders (German Federal Government, 2016[24]). Plans to establish a standing working group of societal actors (“Dialoggruppe”) to support the preparation of SSC meetings should thus move ahead (OECD, 2017[25]).

Indicators established to measure transboundary and domestic impacts set a good example for tracking progress on PCSD. The German Sustainable Development Strategy contains 63 key indicators including at least one indicator-backed target for each SDG. An interministerial working group of representatives from the government and the statistical offices develops and adopts new indicators, while the Federal Statistical Office reports on progress every two years. This enables independent continuous monitoring while maintaining the possibility for revision. Thirteen new topics and 30 indicators have been added to the strategy, some of which include transboundary consequences of national policies. Two examples are a target to increase the share of imports from LDCs, and another to increase membership of the Textile Partnership (Destatis, 2017[26]).

PCSD enables countries to consider transboundary effects of domestic policies. This includes national production and consumption patterns, as well as trade agreements. The German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa (GISCO) is a multi-stakeholder initiative including policy makers and business stakeholders from the cocoa, chocolate and confectionery industry, the German retail grocery trade and civil society. It brings together relevant actors from Germany with those from producing countries and international initiatives to promote sustainable cocoa production. GISCO currently has more than 70 members and is open to other interested parties.

The goal of GISCO is to improve the lives of cocoa farmers and their families, preserve natural resources and biodiversity in cocoa-producing countries and ultimately increase the proportion of sustainable cocoa production. The Federal Government is represented in the alliance by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. The initiative exemplifies how national co-ordinated action across ministries, including stakeholders and the transboundary perspectives can create synergies supporting several SDGs simultaneously.

Source: OECD (2017[25]), German Federal Government (2016[22]).

Greece

A new strategy and SDG-aware public service and law making process supports policy integration and coherence during the whole policy cycle. The National Growth Strategy currently under elaboration will provide the framework to implement the SDGs taking into account national circumstances. Policy coherence, integrated planning and co-ordination are recognised as critical means of implementation. Updated guidelines are being developed by the General Secretariat of the Government (GSG) to ensure that Regulatory Impact Assessment Reports, which accompany the draft laws as well as the ex post evaluation of existing legislation, systematically take into account the three dimensions of sustainable development as reflected in the 2030 Agenda and SDGs. In parallel, training seminars for public employees are held by the GSG in collaboration with the National School of Public Administration and Local Government (EKDDA) to raise awareness of the importance of integrating the three dimensions of sustainable development and for building a network of policy makers across sectors and government levels with shared responsibility for PCSD and the SDGs (Box 3.5).

A permanent co-ordination mechanism at the highest level fosters commitment and continuity in policy coherence efforts. In December 2016, the co-ordination of national efforts to implement the SDGs was assigned by law to the GSG. As a permanent mechanism close to the political leadership and working closely with the parliament, the GSG plays a key role in promoting a whole-of-government approach, preventing and resolving overlaps and disagreements, and mainstreaming SDGs into thematic legislation and sectoral policies. An interministerial co-ordination network for the SDGs was established in 2016 to support the work of the GSG. Two ministries take key roles in the co-ordination network: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs remains responsible for the external dimension of the SDGs, while the Ministry of Environment and Energy is thematically responsible for the implementation of seven SDGs (i.e. 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14 partly and 15). At the regional and local levels, the GSG co-operates closely with the Association of Greek Regions (ENPE) and the Central Union of Municipalities of Greece (KEDE) with a view to localising the SDGs. The GSG also engages key stakeholders in the process (e.g. civil society and social partners, the private sector, academia) and monitors SDG implementation in co-operation with ELSTAT (the statistical authority) (OECD, 2017[27]).

The Office of Coordination, Institutional, International and European Affairs of the General Secretariat of the Government (GSG), in co-operation with the National School of Public Administration and Local Government (EKDDA), organised in November 2017 a three-day seminar on the SDGs to train senior public employees on the international, European and national dimensions of the SDGs. Another seminar organised by the Better Regulation Office of the GSG seeks to highlight, among others, the importance of integrating the three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, and environmental) in the better regulation tools. Through these educational and training seminars, senior officials from line ministries and local and regional administrations become fully aware of the vision, principles and core priorities of the 2030 Agenda. The initiative is also helping to build a network of senior policy makers across sectors and government levels with shared responsibility and commitment to PCSD and SDGs.

Source: OECD (2017[27]).

Japan

Interministerial co-ordination at the highest level backed by a concrete action plan provides a strong basis for policy coherence. In May 2016 the government established the SDGs Promotion Headquarters (Box 3.6). This new body, composed of all cabinet ministers, is led by the prime minister. It acts as a control tower to ensure a whole-of-government approach to SDG implementation and fosters co-operation among ministries (Government of Japan, 2017[28]). In December 2017, the SDG Promotion Headquarters adopted the SDGs Action Plan 2018, which focuses on three overarching goals: 1) promoting Society 5.0, which corresponds to the SDGs, 2) vitalising local areas through SDGs, and 3) empowering women and future generations. By setting these three cross-cutting themes, Japan recognises their indivisibility and the need for integrated approaches for implementation (OECD, 2017[29]) . The action plan also includes a wide range of specific government projects that are categorised by eight priority areas, along with the SDG s Implementation Guiding Principles.

Guiding principles for implementation support policy integration in pursuit of the SDGs. In December 2016, the SDGs Promotion Headquarters adopted The SDGs Implementation Guiding Principles. The guidance set out a vision1; five implementation principles (universality, inclusiveness, participation, integration, and transparency and accountability); eight priority areas (including 140 specific measures to be implemented both domestically and through international co-operation); and an approach to the follow-up and review process. The Guiding Principles provide a framework for integrating the SDGs into the plans, strategies and policies of ministries and government agencies. They also aim to mobilise all ministries and government agencies by partnering with stakeholders to implement the SDGs, based on an analysis of the present situation in Japan and abroad (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017[30]).

Setting national long-term priorities enables the political leadership to pursue the 2030 Agenda and SDGs more coherently. By translating the SDGs into concrete action at national level, the government has identified eight priority areas in which all ministries are required to contribute: 1) Empowerment of All People; 2) Achievement of Good Health and Longevity; 3) Creating Growth Markets, Revitalization of Rural Areas, and Promoting Science Technology and Innovation; 4) Sustainable and Resilient Land Use, Promoting Quality Infrastructure; 5) Energy Conservation, Renewable Energy, Climate Change Countermeasures, and Sound Material-Cycle Society; 6) Conservation of Environment, including Biodiversity, Forests and the Oceans; 7) Achieving Peaceful, Safe and Secure Societies; and 8) Strengthening the Means and Frameworks for Implementation of the SDGs. A first follow-up and review of progress will be conducted in 2019. According to this outline, Japan plans to enhance policy coherence for sustainable development (target 17.14) at the international level by supporting developing countries in establishing implementation systems for the SDGs (Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017[30]) .

The SDGs Promotion Headquarters is responsible for raising awareness of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs Implementation Guiding Principles. It proactively plans and leads communication activities to promote SDGs-related measures as a national movement in order to increase public understanding and support for engagement with the SDGs.

As part of this effort, the government is fostering the sharing of good practices among implementing partners, including the private sector, by giving awards and promoting the use of SDGs logos and branding. The government will further promote Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) as well as encourage learning about SDGs in all settings, including schools, households, workplaces and local communities. The aim is to give children, who will lead society in 2030 and beyond, the competencies to create sustainable societies and a sustainable world.

The SDGs Action Plan 2018 recognises international events such as the HLPF, the G20, the 2019 Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) in 2019, the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2020 and bidding for 2025 Expo as suitable occasions to further raise awareness of the SDGs and promote their implementation.

Source: OECD (2017[29]).

Lithuania

Commitment to coherence at the national and international levels provides a good basis to pursue more integrated policies. Last amended in 2011, The National Strategy for Sustainable Development (NSSD) is Lithuania’s main strategic document ensuring national commitment and implementation of the SDGs and PCSD. It aligns with the SDGs and stresses commitment to policy coherence as a main implementation principle (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2011[31]). The long-term strategic document Lithuania 2030 contains the vision and goal to reach a top ten position in Europe on development and happiness indices (State Progress Council, 2012[32]). The government is currently updating this strategy as well as the body responsible for its supervision: the National Progress Council. Regarding development co-operation, for the first time the government adopted an Inter-Governmental Development Cooperation Action Plan for the period 2017-2019 which defines policy guidelines and implementing measures. The multi-stakeholder forum led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the National Development Cooperation Commission, NDCC), is responsible for PCD in development co-operation. It meets at least twice a year and submits proposals to the MFA on development co-operation policies. This cross-ministerial collaboration strengthens the interface between internal and external commitment to PCSD.

Updating institutional mechanisms can provide an opportunity to enhance and integrate co-ordination mechanisms for policy coherence at the national level. The Ministry of Environment (MoE) co-ordinates the implementation of the national strategy and functions as secretariat for the National Commission on Sustainable Development (NCSD). The NCSD is chaired by the prime minister and comprises representatives from ministries, municipal institutions, NGOs, academia and business. In August 2016 the NCSD identified six areas of highest importance to Lithuania: combating social exclusion and eradication of poverty; healthy lifestyle; energy efficiency and climate change; sustainable consumption and production; high quality education; and development co-operation. The MoE has established an intergovernmental working group that provides inputs for the implementation of SDGs in Lithuania. Currently in reform, the National Progress Council and NCSD will be merged to create a unified body responsible for the implementation of 2030 Agenda, and include mechanisms for arbitration in the case of conflict. This institutional change will facilitate co-ordination for coherent policies. Lithuania is planning to strengthen the role of the Prime Minister’s Office in the future and might consider moving the NCSD from the MoE to a high level. Such actions have facilitated effective co-ordination in other countries (UNDP, 2017[33]).

Current collaboration across ministries provides lessons for future reporting on policy coherence. Aiming to nationalise the SDGs, the MoE along with all relevant ministries has mapped and evaluated the coherence between the 17 SDGs and the national strategy and other relevant strategic documents (OECD, 2017[34]). Currently stakeholders are invited to participate in the meetings of the Inter-institutional Working Group, including the Prime Minister’s Office and the MoE (responsible for co-ordinating VNR preparations). The MoE reports every two years on implementation progress of the NSSD, while the national statistics office is responsible for collecting, collating and publishing sustainable development indicators.

Integrated approaches minimise adverse environmental impacts and maximise eco-efficiency. In Lithuania, different governmental institutions co-ordinate their actions in order to increase awareness and ensure the integration of environmental aspects into the implementation measures in their respective policies. Ministries collaborate to approve necessary norms, normative standards and rules as means to achieve environmental objectives. An integral approach is applied to transport, industry, energy, construction, agriculture, housing, tourism, healthcare and other sectors by promoting the use of best available techniques (BAT), effective pollution prevention technologies, and by taking into consideration the life cycle approach to production. Lithuania has implemented an integrated system of pollution prevention and control which includes water, air and soil protection and waste management measures. It ensures compliance via three principles: 1) the BAT is applied and, natural resources are used rationally, economically and energy efficiently; 2) waste is prevented, prepared for reuse, recycled, recovered or disposed of; 3) usage of hazardous substances is reduced and these substances are gradually replaced with less hazardous ones.

Environment and health considerations must be considered as part of an environmental impact assessment of a proposed economic activity before implementation. (Law No I-1495, last amended in April 2016). This set-up prevents environmental deterioration and ensures inclusive and representative decision making on at local, regional and national levels.

Source: OECD (2017[34]).

Luxembourg

With a clearly stated commitment, Luxembourg has engaged in a process to strengthen governance for policy coherence. The approach pursued through the third National Plan for Sustainable Development (NPSD), due in 2018, aims to identify policies likely to have an impact on the three dimensions of sustainable development, in line with the 2030 Agenda, and will further address PCSD (OECD, 2017[35]). The report on implementation of the 2030 Agenda adopted by the government in May 2017 emphasises the need to establish mechanisms and institutions to support SDG17.14. It further outlines the whole-of-government approach envisioned for SDG implementation and the need for enhanced co-ordination and efficiency in order to ensure the mobilisation and use of all available resources (Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, 2017[36]). The 2017 VNR states the need to ensure the maximum coherence of policies both internally and externally in SDG implementation (Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, 2017[37]).

New institutional arrangements for collaboration among ministries can help enhance coherence between domestic and international policies for delivering on the SDGs. The Inter-Departmental Commission on Sustainable Development (ICSD), composed of representatives from all ministries and government administrations, is the central co-ordinator of domestic sustainable development policies. Established in 2004, the ICSD will be equipped with the necessary competencies to address PCSD via the NPSD as well as to promote and monitor SDG implementation and draft reports. The Interministerial Committee for Development Cooperation (ICD) meets six times a year to identify and discuss trade-offs and synergies and formulate non-binding recommendations to the government regarding PCD. In 2014 it adopted a new working method involving consultations with civil society, choice of subjects, analysis and findings. Members of the ICSD participate in the ICD and vice-versa (OECD, 2017[35]). Policy coherence efforts can benefit from the introduction of a specific mandate to resolve potential incoherence issues that might arise during SDG implementation (OECD, 2017[38]).

To strengthen the coherence and the whole-of-government approach to fight climate change, several ministries work closely together, including the Department of Environment of the Ministry of Sustainable Development and Infrastructure, the Directorate for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, and the Ministry of Finance.

Cross-representation of sector experts has been introduced to promote coherence. The Department of the Environment is represented in the Interministerial Committee for Development Cooperation (ICD), in the Lux-development executing agency and in its audit committee. The Directorate for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs is represented in the Interdepartmental Commission on Sustainable Development (ICSD) and in the Climate and Energy Fund (FCE).

There is greater co-operation in strategy and criteria. In May 2017, FCE adopted its strategy and eligibility criteria for international climate financing in collaboration with the Directorate for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Affairs. The ICD has also adopted a set of criteria for environmental and climate policy.

Vertical coherence has also increased. A climate pact between the municipalities and the Luxembourg state guides municipalities in the implementation of their energy and climate policy, and municipalities agree to establish an “energy accounting system” for buildings, public lighting and communal vehicles. This partnership and the participation of various actors at the municipality level have helped to intensify efforts in energy and climate policies.

Source: OECD (2017[35]).

Mexico

An explicit commitment of the State towards the 2030 Agenda, backed by an implementation strategy, provides the basis for aligning efforts at federal, state and municipal levels. In 2016, Mexico’s president affirmed in his statement to the 71st UN General Assembly that his country had embraced implementation of the 2030 Agenda as a “commitment of the State”.2 A National Council for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, chaired by the president, was established in 2017 as a bonding mechanism between the federal and local governments, civil society, the private sector and academia. Its main purpose is to “coordinate the actions for the design, execution and evaluation of [...] policies [...] for the compliance with the… 2030 Agenda.”3 A National Strategy for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda will be developed under the coordination of the President’s Office. The new strategy will set out national priorities, targets, public policies, concrete actions and indicators based on a broad consultation process involving stakeholders at the federal, state, and local levels. The National Governors’ Conference (CONAGO) has established an Executive Committee for Compliance with the 2030 Agenda: so far, 21 out of 32 states have established local councils to implement the 2030 Agenda at the state level. Practical guidelines have also been developed to this effect in state and municipal development plans (Government of Mexico, 2017[39]). Finally, the Senate has set up a Working Group for the Legislative Follow-up of the SDGs.

Leadership at the highest level is helping to lay institutional foundations to ensure that commitment towards the 2030 Agenda transcends government administrations. Co-ordination for national implementation is led by the Office of the President. The National Council for the 2030 Agenda, chaired by the president himself, has been established as a mechanism for improving national planning with a clear strategic vision. The new National Strategy for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda will incorporate a long-term vision to guide the elaboration of future National Development Plans (NDP).

National planning and budgetary processes provide essential tools for policy integration and coherence. The National Planning Law was updated in 2017 and now mandates current and upcoming federal administrations to take into consideration the principles of the 2030 Agenda. It also integrates the three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social and environmental). Finally, the updated Planning Law mandates to take a 20-year perspective into consideration. The SDGs Specialised Technical Committee (CTEODS), led by the Office of the President and the Institute of Statistics and Geography, developed a framework with the Ministry of Finance to integrate planning, public finance management, policy making and oversight to support the achievement of the SDGs. Within this framework, the Ministry of Finance has identified mechanisms in collaboration with UNDP to link budget allocations with the SDGs with a view to strengthening strategic planning, monitoring and evaluation (Box 3.9).

The Office of the President, the National Institute of Statistics and Geography and the Ministry of Finance, with the support from the United Nations Development Programme, have sought to define and develop mechanisms to link Mexico’s budget with the SDGs. The purpose was to identify specific budget items and estimate the allocation sufficient to contribute to progress on the SDGs, using a results-based management perspective.

Given the current indirect link between budgets and SDGs, Mexico used key elements of its institutional architecture to strengthen the connection: 1) national planning; 2) programmatic structure based on budgetary programmes; 3) the performance evaluation system; and 4) accounting harmonisation. Building on this, two main steps have been taken:

-

Linking: each ministry has applied the performance evaluation system and national planning to match their programmes to the SDGs;

-

Quantifying: programmes that contribute to each SDG target were identified indicating a direct or indirect contribution in order to estimate the total investment per target and overall. 102 SDG targets were further disaggregated by different topics (sub-goals), allowing a more precise indication of any sub-goal to which a programme is linked.

As a result of this process, Mexico has improved information to:

-

identify the link between the current national planning (medium-term) and the long-term SDGs;

-

assess the percentage of SDGs linked to government programmes and, conversely, the number of programmes linked to each SDG;

-

communicate the country’s starting point and what has been achieved;

-

make public policy decisions and budget allocations based on an initial analysis of how much is currently invested in each SDG.

Source: Mexican Ministry of Finance (2017[41]).

The Netherlands

Commitment and experience in delivering coherent policies for development abroad can provide lessons for applying a PCSD lens to domestic policies. The 2017-2021 Dutch Coalition Agreement Confidence in the Future, which has a strong focus on sustainability, proposes policies and actions that are in substance strongly aligned with the SDGs. Moreover, it stresses the importance of coherence both internally and externally. Regarding international commitments, the forthcoming policy note on foreign trade and development co-operation takes the SDGs explicitly as the guiding framework (Government of The Netherlands, 2017[42]). The national action plan on policy coherence for development, stemming from 2016, includes goals linked to the SDGs focusing on eight priority areas: international trade agreements; access to medicine; tax avoidance; sustainable value chains; remittance transaction costs; climate change; investment protection; and food security (OECD, 2017[43]). This issues-based approach helps to identify synergies and trade-offs, and to monitor the coherence of policies (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017[44]). The adoption of the 2030 Agenda renewed attention to policy coherence including persistent challenges (Kingdom of the Netherlands, 2017[45]). To this end, the Netherlands engaged in discussions to concretise the concept and co-financed a discussion paper (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017[44]).4

Policy coherence is ensured by the Council of Ministers, while SDG implementation is co-ordinated by the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation. As the executive council of the Dutch government, the Council of Ministers initiates laws and policies and is in a position to take into account transboundary and inter-generational interests as well as to achieve a balanced approach to the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. Led by the prime minister and including the deputy prime minister, it meets every week to debate proposed decisions (OECD, 2017[46]). In a further effort to increase effectiveness and enhance policy coherence, particularly between aid, trade and foreign affairs, two ministers notably have cross-cutting mandates: the Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy and the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation (OECD, 2017[43]). Responsibility for SDG implementation is assigned to all relevant ministers in accordance with their existing responsibilities. This provides a sound basis on which to proceed. This approach does require clear co-ordination and assessment of policy proposals in order to avoid conflicts or overlaps (Netherlands Court of Audit, 2017[47]).

Whole-of-society engagement and expertise contribute to effective monitoring processes. Statistics Netherlands (CBS) identifies actors and data sources for SDG monitoring in Measuring the SDGs: An Initial Picture for the Netherlands (Statistics Netherlands, 2017[48]). The report’s second edition, published in March 2018, acknowledges possible difficulties to quantify SDG 17.14 (Statistics Netherlands, 2018[49]). Two additional annual reports to parliament exist: one on SDG implementation and the other on policy coherence. A multi-stakeholder online platform, the SDG Charter and its SDG Gateway, link companies, NGOs, knowledge institutes and philanthropists who wish to partner for the SDGs. In addition, many municipalities give visibility to local initiatives online and encourage the participation by society, as illustrated by best practices in the country’s 2017 VNR.

The Minister for Foreign Trade and Development is looking into the feasibility of introducing a “SDG test” (or “check”) across government departments in response to a request from Parliament. Such an instrument, carried out in collaboration with other ministries, could potentially contribute to enhancing policy coherence by allowing for an ex ante assessment of whether new policy proposals are in line with the SDGs. The pros and cons of such a test have already been communicated to Parliament in a policy letter in September 2017. The Ministry reported back to Parliament (Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation budget discussion – 23 November 2017).

Source: OECD (2017[46]).

Poland

A national strategy and the Multiannual Development Cooperation Programme provide a strong basis for coherent SDG implementation. The Strategy for Responsible Development (SRD), adopted by the Council of Ministers in February 2017, aims to support implementation of the 2030 Agenda. It outlines the principles, priorities, objectives and implementation instruments of a new model for Poland’s economic, social and spatial development with perspectives up to 2030 (OECD, 2017[50]). It also provides a system for co-ordinated and integrated implementation defining the roles of respective public institutions and ways of collaboration with other stakeholders. The SRD introduces a wide variety of initiatives and is being implemented with a project approach. The second Multiannual Development Cooperation Programme 2016-2020 incorporates policy coherence as a principle of development co-operation with an explicit link to support SDG implementation and ensure consistency with the global goals (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015[51]). Poland has established two priority areas for policy coherence: 1) addressing illicit financial flows, in particular tax avoidance/evasion and money laundering and 2) promoting standards and principles of Corporate Social Responsibility and Responsible Business Conduct. Both priorities are implemented according to annual action plans in co-operation with all relevant ministries (OECD, 2017[52]) (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2016[53]).

An effective interface between different interministerial mechanisms will be instrumental in ensuring a coherent implementation, both domestically and internationally. The Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Technology co-ordinates national SDG implementation. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) is responsible for co-ordination of the coherence of domestic policies focusing on developing countries within the two established priority areas for PCD. Contact points in ministries support efforts to promote PCD, while ministries remain responsible for coherence between the SDGs and sectoral policies (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015[51]). PCD challenges are discussed in several institutional structures. The Development Cooperation Programme Board defines and discusses annual action plans on PCD priority areas (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015[51]). The Economic Committee of the Council of Ministers (ECCM) and the Coordinating Committee for Development Policy (CCDP) provide additional platforms for exchanging information and seeking consensus in the case of divergent positions. Furthermore, the government has created a special Task Force for Cohesion of the SRD with the 2030 Agenda within the CCDP, consisting of representatives from national and local government, academia and the socio-economic community. The MFA is represented in this task force, thus allowing for PCD issues to be raised and discussed during its meetings (OECD, 2017[50]).

Regulatory impact assessments can be instrumental in considering transboundary impacts of national policies. Poland has adapted its Guidelines for Regulatory Impact Assessments to include a question about the transboundary impact of national regulations on social and economic development in Poland’s priority countries (OECD, 2017[52]). This is an important step towards monitoring PCSD, applicable in the future to other policies and countries. The Minister of Investment and Economic Development reports annually on SRD implementation progress. The report is submitted for comments to the CCDP and for consideration to the Council of Ministers that oversees implementation and conducts periodic inspections of the monitoring process. Poland will submit a report on ministerial actions for PCD and a report on the performance of annual action plans to their Development Cooperation Programme Board, the OECD and the EC (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015[51]).

The Polish government, with the Ministry of Investment and Economic Development taking a leading role, has proposed the Program for Silesia as one of the strategic projects of its Strategy for Responsible Development (SRD). The programme, adopted by the Council of Ministers on 14 February 2018, was subject to consultations with other ministers (i.e. Ministry of Energy) and stakeholders, e.g. the Voivodeship Council of Social Dialogue (VCSD) in Katowice and other Silesian partners. The starting point for the development of goals, activities and identification of the most important development projects in this document was the “Agreement on the Integrated Development Policy of the Silesian Voivodship” signed by members of the VCSD in 2016.

Silesia is recognised in the SRD as one of the key areas of intervention at national level, struggling with adaptation and restructuring difficulties. It is one of the strongest economic regions in Poland, but has recently experienced a slowdown in growth and decline in the quality of life of its inhabitants. The Government’s Program for Silesia includes an integrated set of investment and soft operations.

This is the first programme in the regional government policy that co-ordinates funding sources from both national and European programmes and institutions. The main objective of the Program is to change the economic profile of the region and to gradually replace traditional sectors of the economy such as mining and metallurgy with new ventures in more productive, inclusive, innovative and technologically advanced sectors.

Source: (OECD, 2017[52]).

Portugal

New guidelines are being developed to strengthen policy coherence in support of SDG implementation, building on existing legislation. The 2030 Agenda has created new momentum for policy coherence at the highest level of government. Political commitment, as anchored in existing legislation and mechanisms to promote policy coherence for development (PCD), is being reaffirmed with the introduction of new intra-governmental guidelines aligned to the 2030 Agenda. Since 2010, the Council of Ministers Resolution 82/2010 has provided a legal framework for ensuring coherence between national policies that may impact on other countries, while the Strategic Concept for Portuguese Co-operation 2014-2020 has promoted policy coherence with regard to development co-operation. Following the adoption in 2015 of the 2030 Agenda, in 2016 the Council of Ministers adopted intra-governmental guidelines that take into account the need to closely align domestic and international dimensions of SDG implementation. These guidelines will further enhance PCSD, as will the importance attributed to PCSD in Portugal’s 2017 Voluntary National Review (Ministry of Foreign Affairs Portugal, 2017[54]).

Institutional mechanisms are being adapted to better co-ordinate the internal and external dimensions of SDG implementation and foster policy integration. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs co-ordinates overall implementation of the SDGs, together with the Ministry of Planning and Infrastructures, in line with intra-governmental guidelines adopted in 2016. Two supporting bodies are responsible for co-ordinating the internal and external dimensions, respectively: the Interministerial Commission of Foreign Policy (CIPE) and the Interministerial Commission for Co-operation Policy (CIC). A network of focal points from different government departments, led by the Institute for Co-operation and Language (Camões I.P.), seeks to facilitate information sharing on policy implications; mainstream policy coherence concerns into sectoral policies; and identify potential synergies and trade-offs between different policy objectives. Ongoing efforts to establish PCSD priorities, together with a National Plan for Policy Coherence for Development, will further strengthen cross-sectoral collaboration and integration (OECD, 2017[55]).

The National Institute for Statistics (Statistics Portugal) identifies appropriate data sources and helps facilitate consistency across different levels of monitoring and reporting. Statistics Portugal works closely with the statistical departments of different ministries and other national authorities involved in SDG implementation at the national level. It also monitors regional and global SDG initiatives, together with e.g. the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) and Eurostat. These processes have enabled national and international mapping of available indicators and data sources for monitoring the SDGs in Portugal. All existing information is made available on a single SDG platform on Statistic Portugal’s website in order to give the public easy access and an overview of identified indicators (OECD, 2017[55]).

Slovak Republic

Policy coherence is one of the guiding principles of the Slovak 2030 Agenda implementation strategy, adopted in July 2017. The country is currently defining a limited number of national priorities for achieving the SDGs. This process involves all relevant line ministries and will set long-term priorities and measurable goals. PCSD is viewed as an integral part and enabling mechanism of SDG implementation. The government acknowledges the need for co-ordinated action horizontally and vertically.

Co-ordination mechanisms help to operationalise the policy coherence guiding principles. The Deputy Prime Minister´s Office for Investments and Informatization (DPMO) is responsible for Agenda 2030 implementation at the national level. It seeks to engage political leaders and co-ordinate government policies for sustainable development through the Government Council for Agenda 2030. The mechanism allows for information sharing and arbitration in the case of disagreement in the process of defining long-term national priorities, and takes into consideration both domestic and international objectives related to implementation of the SDGs. The DPMO is currently working to present a final draft of priorities acceptable for all by mid-2018. The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs is responsible for the external dimension of Agenda 2030 and co-operates closely with the DPMO.

Slovenia

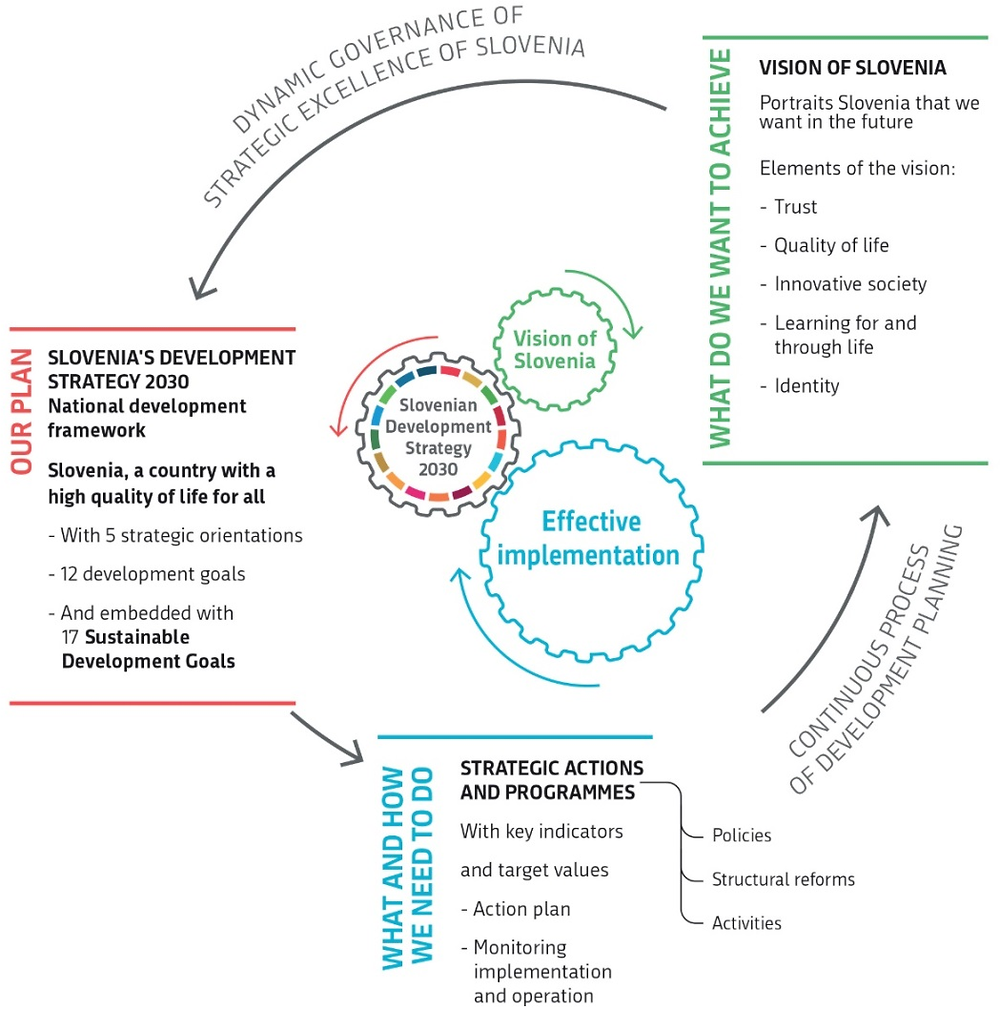

A new national development strategy aligned with the SDGs lays the foundation for enhancing policy coherence for sustainable development. The Slovenian Development Strategy 2030, adopted by the government in December 2017, builds on the Vision of Slovenia and incorporates the SDGs. With an overarching objective to provide a high quality of life for all, it sets out five strategic orientations and 12 interlinked national goals mapped to each SDG: highly productive economy that creates added value for all; resilient, inclusive, safe and responsible society; well-preserved natural environment; efficient and competent governance driven by co-operation; and learning for and though life. The strategy highlights the need to consider interconnections and cross-cutting elements and integrate policies at the national level. It also emphasises the need to establish better mechanisms for horizontal and multilevel co-operation. Implementation will be guided by a four-year national development policy programme (NDPP) and a medium-term fiscal strategy, as well as corresponding horizontal and sectoral, regional and municipal strategies, programmes and operational measures (Government of the Republic of Slovenia, 2017[57]).

New institutional mechanisms aim to strengthen co-ordination, stakeholder involvement and policy coherence. At the beginning of 2017 the government established the Permanent Interministerial Working Group on Development Policies (IMWG) to foster an integrated approach and promote policy coherence. The group is co-ordinated by the Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy, and consists of two representatives from each ministry who act as focal points for development policies and the 2030 Agenda. Representatives of the National Statistical Office and the Institution for Macroeconomic Analysis and Development are also members of the IMWG (Government of the Republic of Slovenia, 2017[58]). The group operates as a mechanism for horizontal collaboration in preparing the Slovenian Development Strategy 2030 and the VNR. Policy coherence efforts could be enhanced by giving the IMWG a policy arbitration mandate (OECD, 2017[59]). The government plans to establish a new special advisory body, the Council for Development, to oversee delivery of the Slovenian Development Strategy 2030. The Council will include a range of stakeholders including private sector, civil society, representatives of regional and local communities and the government. The Court of Audit follows implementation gaps, considering them to be one of the key criteria for deciding on what to audit, and points out areas where problems might occur (OECD, 2017[60]).

Source: Government of the Republic of Slovenia (2017[57]).

Spain

A new high-level interministerial mechanism is increasing the relevance of the SDGs in the national policy agenda and helping to mobilise the government. A High-Level Group for 2030 Agenda (HLG) was created in September 2017, under the authority of the Government Delegated Commission for Economic Affairs, to co-ordinate SDG implementation. The HLG is chaired by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, with the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Environment and the Minister of Public Works serving as vice-chairpersons. The HLG is composed of representatives of all ministries at director-general level, along with the Director of the Economic Office of the prime minister, the State Secretary for International Cooperation and Ibero-America, the State Secretary for Territorial Administration, and the National Statistics Institute. It is open to participation of the private sector, civil society organisations, parliaments, academia and experts. Its main functions are to: foster integration of the SDGs and targets into national public policy frameworks; co-ordinate and ensure coherence between diverse sectoral policies and legislative initiatives; promote the elaboration of a national strategy for sustainable development, prepare national reviews of Spain for the UNHLPF, and define and co-ordinate the Spanish position on the 2030 Agenda and SDGs in international forums (BOE, 2017[62]).

A longstanding tradition of promoting policy coherence for development is paving the way for establishing a policy coherence system adapted to the 2030 Agenda. Spain is one of a handful of countries that has written its commitment to PCD into its legal framework (OECD, 2013[63]).5 It has also put in place the three elements of PCD: political commitment backed by a legal basis; co-ordination mechanisms with specific mandates for promoting PCD (including a dedicated unit for PCD and a network of focal points, the Inter-territorial Commission of Cooperation, Interministerial Commission of Cooperation and Development Cooperation Council); and the obligation to report biennially to the parliament and the public (OECD, 2016[64]). Building on this experience, Spain is currently shifting from PCD towards PCSD. The newly-created HLG for 2030 Agenda has enhancing coherence between sectoral policies and among legislative initiatives for SDG implementation as one of its main functions.

Existing consultation bodies at different levels of government will be essential for ensuring vertical coherence in SDG implementation. There are diverse consultation bodies among different levels of government which will address implementation of the 2030 Agenda and can help enhance coherence. These include:

-

The Conference of Presidents operates at the highest level of the executive power (presidents of regions, in the remit of their competences and territories, have functions comparable to those of prime ministers in the national context). This assembly provides a forum for dialogue between presidents both of the national government and the regions.

-

Sectoral conferences at ministerial level. This structure is replicated at the regional level to engage cities and municipalities.

-

Territorial bodies called provincial councils that aim to optimise services of small cities and municipalities, and that operate in an intermediate stage between regions and municipalities.

-

The Senate, as a territorial upper chamber in which a certain number of senators have been appointed by Regional Chambers. This chamber is the last instance for the approval of laws in Spain. In 2017, the Senate established a study group that is preparing a report on the SDGs and its implications at national, regional and municipal levels.

Sweden

A new National Action Plan will apply the Policy for Global Development (PGD) as a key tool for mobilising coherent whole-of-government action. The PDG mandated all ministries for the first time to develop internal action plans with concrete goals and clear responsibilities for the work of the PGD linked to the 2030 Agenda (Government of Sweden, 2017[66]). This process provided an opportunity to anticipate and manage potential conflicts of interest between sectors and between domestic and international priorities in 2014–2016. The most recent government communication, Sweden’s policy for global development in the implementation of Agenda 2030, sets out the government’s work for 2016-2017 covering and reporting on all SDGs. The government reports examples of its work with the PGU under the 2030 Agenda and the Global Goals. One section of this communication is a more in-depth report of five areas where the Government has expressed a particular ambition during the period – feminist foreign policy; sustainable business; sustainable consumption and production; climate and sea; and capital flight and tax evasion – identifying areas where conflicting objectives within and across government might limit opportunities to achieve equitable and sustainable global development and where alignment and synergies are present. The communication further outlines the responsible ministries for each PGD area under the respective global goals. Policy coherence is thereby considered as the backbone of PGD (Government Offices of Sweden, 2018[67]).

Reports to parliament every two years enhance transparency in the handling of conflicts of interest and strengthen co-ordination for policy coherence. The Minister for Public Administration at the Ministry of Finance is responsible for co-ordinating national implementation of the 2030 Agenda. All ministries at the level of policy officers/analysts participate in a monthly interministerial working group. In addition, a consultation group for the 2030 Agenda meets three to four times a year with participation of state secretaries from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Environment and Energy, the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation. The Minister for International Development Cooperation and Climate at the MFA is responsible for Sweden’s contribution to international SDG implementation. A PCSD co-ordination team at the MFA guides the ministries by checking documents and decisions for the degree of mainstreaming and PCSD in the 2030 Agenda. Each ministry, however, retains responsibility within its respective policy domain to adopt policies and raise potential conflicts to a political level.

The Government expects Swedish companies to use international sustainable business guidelines as a basis for their work, in Sweden and in other markets. In December 2015 it submitted a Communication to the Parliament on its policy for sustainable business (Communication 2015/16:69). The communication sets out the Government’s expectations of companies’ work on sustainability and practical recommendations on how to achieve them.

The international guidelines incorporate primarily the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Companies, the UN Global Compact, the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the fundamental conventions of the ILO and tripartite declarations as well as the 2030 Agenda. On the basis of this Communication, the Government created a platform in 2016 to provide guidance for sustainable business geared towards Swedish companies.

The Government has additionally drawn up a national Action Plan for business and human rights that contains about fifty measures to put the UN’s Guiding Principles in this area into practice. The Action Plan urges Swedish companies, and others, in line with the UN’s Guiding Principles, to adopt company policies that take into account respect for human rights in their operations, put in place an internal process to survey and control risks in the value chain with regard to human rights infringements (due diligence) and, ensure transparency by reporting on risks.

Source: OECD (2017[68]).

Switzerland

A shared strategic framework with clear guidelines is instrumental for pursuing policy coherence. The Sustainable Development Strategy (SDS) 2016–2019, adopted by the Federal Council, is an important instrument and reference framework for implementation of the 2030 Agenda. It includes an action plan with nine thematic areas explicitly linked to each SDG. Furthermore, new legislative projects and processes must reference the SDGs. PCSD is an important instrument for integrating sustainable development into sectoral policies, and one of five Federal Council guidelines (Swiss Federal Council, 2016[69]). Political commitment to PCSD is thus expressed at the highest federal level. The Swiss decentralised governance system and culture of consensual decision making means, however, that the SDS has limited practical implication at the local level (OECD, 2017[70]). Instead, it will be crucial to strengthen alignment or vertical policy coherence between the Confederation, cantons and communes.

Co-ordination and consultation across and within levels of government can support coherent policies. The Federal Council, a seven-member executive council heading the federal administration and operating as a collective presidency and a cabinet, promotes PCSD through a regularly two-tiered consultation mechanism. First, the office in charge of a policy organises a technical consultation to gather and consolidate comments from other offices. Thereafter, political consultation among Federal Councillors prior to and in view of final decisions balances out different perspectives, trying to take into account concerns of sustainable development. Nevertheless, the political consultation reflects political interests and power structures and outcomes are not always in line with sustainable development (OECD, 2017[70]). Implementation of the SDS and the SDGs in domestic policy is co-ordinated by an interdepartmental committee of directors and the associated management office, co-led by the Federal Office for Spatial Development (ARE) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). They co-ordinate work on national and international SDG implementation and include representatives from relevant Federal Offices, such as the Federal Offices for the Environment, Health, Agriculture, Statistics, Economic Affairs, Foreign Affairs and Federal Chancellery (Swiss Confederation, 2018[71]). This co-leadership arrangement by the MoE and MFA helps to take into consideration both domestic and international objectives and foster coherence in the implementation of the SDGs.