Chapter 3. Indigenous job creation through SMEs and entrepreneurship policies

Attracting inward investments into Indigenous communities require a clear investment environment as well as incentives for businesses to locate in a region. This requires many communities to encourage entrepreneurship and provide business development support services. This chapter examines key trends in entrepreneurship and SME activity of Indigenous People and provides examples of programmes that have been implemented at the local level.

Fostering entrepreneurship opportunities for Indigenous People

As a young and growing demographic group, forecasts suggest that the Indigenous population could represent about one fifth of Canada’s labour force growth over the next 20 years if gaps in the labour force participation rate were to close (Drummond, 2017). The provision of access to quality education and skills allows Indigenous People to ameliorate their participation in the labour force not only through increased employment and employee retention, but also through job creation as Indigenous entrepreneurs and SME owners—the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (CCAB) estimates that 36% of Indigenous businesses create further employment (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016).

Self-employed Indigenous People boost the economy not only through their own employment and commerce, but often through the employment of other staff members as well. However, Indigenous People often confront barriers when seeking to become entrepreneurs—access to business financing, professional networks and financial literacy are issues that many Indigenous People have to address when considering the path of self-employment. While difficult, these adversities can be addressed and lead to thriving examples of Canadian enterprises both on and off reserve.

Current state of Indigenous entrepreneurship and SMEs in Canada

Similar to trends observed in the general Indigenous population, the numbers of Indigenous entrepreneurs in Canada is increasing substantially. According to the 2011 Canadian census, there were more than 37 000 Indigenous People self-employed in 20111with nearly 10 000 Indigenous entrepreneurs entering the labour market from 2003 to 2011. In comparison with the 10.5% of non-Indigenous People who engage in self-employment, the 2011 NHS observes that 5.6% of Indigenous People were self-employed in 2011 (The Conference Board of Canada - Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

Indigenous businesses are also characterized as being profit and stability seeking (60%) in contrast to growth and risk (22%). Nearly two-thirds of Indigenous businesses have introduced new products, services or processes within three years of the survey, illustrating a prevalent culture of innovation and creativity (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). Additionally, the majority of Indigenous entrepreneurs’ markets are focused within their local community area (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016).

Mirroring the general population demographics, Indigenous entrepreneurs are considerably younger than their non-Indigenous counterparts. About 20% of Indigenous entrepreneurs are less than 25 years old, compared to 15% of non-Indigenous entrepreneurs. Therefore, organisations assisting Indigenous entrepreneurs may need to cater more services to a youthful market (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

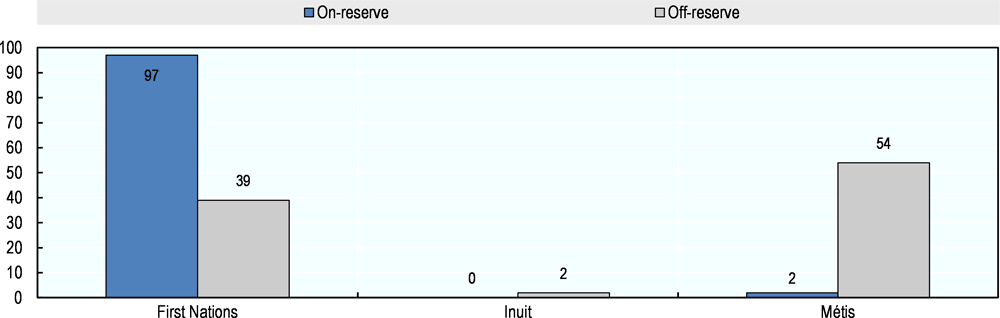

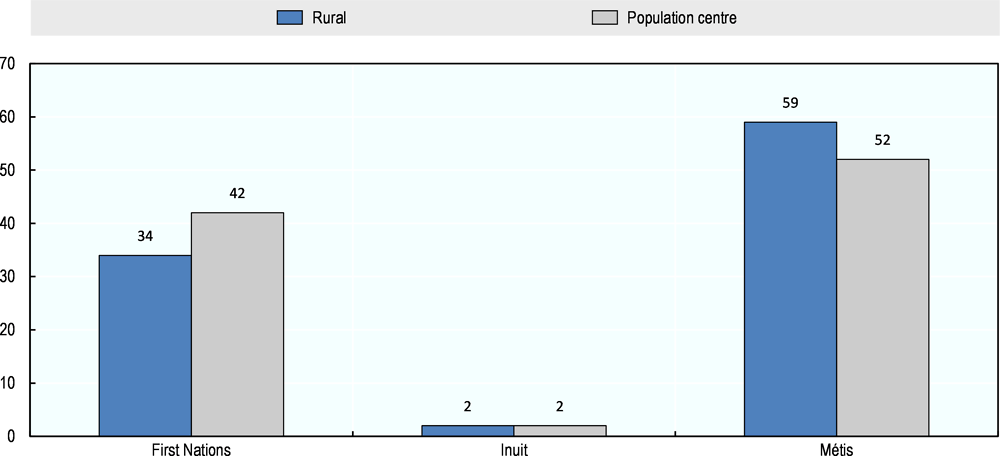

Geographic location

At a provincial and territorial level, the majority of Indigenous entrepreneurs live in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec. According to CCAB, “self-employed Aboriginal people remain over represented in British Colombia and Alberta and underrepresented in Manitoba and Saskatchewan” compared to the total population in each area (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). At a regional level, the majority of Indigenous entrepreneurs are located off-reserve, with about 40% living in census metropolitan areas (SMA) of 100 000 people or more (DePratto, 2017) (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). Furthermore, at a local level, most Indigenous businesses are home-based with two-thirds of self-employed entrepreneurs operating from their personal dwelling area (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). Of the on-reserve self-employed Indigenous population, 97% was comprised of First Nations people in 2011. Indigenous entrepreneurs on-reserve and in rural areas face additional challenges accessing larger markets and financial institutions. Some even have difficulties acquiring a bank account, let alone access to business loans. In contrast, Indigenous entrepreneurs living in an urban context have access to a larger market and network of resources. However, middle income Indigenous entrepreneurs may receive less attention from programme support while still facing a variety of structural and socioeconomic issues (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

Size, stage and structure

CCAB data from a 2016 survey states that 60% of Indigenous entrepreneurs describe their businesses as established (within the business cycle) (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). The same survey demonstrations that 73% of Indigenous business are unincorporated, with more than 60% of Indigenous businesses are sole proprietorships (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016) (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). These businesses provide to be easier to start in terms of structure and bureaucracy, but also, on-reserve entrepreneurs are further encouraged to use this model since corporations can still be taxed on reserves.

Within incorporated Indigenous businesses, there are Aboriginal Economic Development Corporations (AEDCs). About 260 are operating nationwide and the majority have less than 100 employees. While many are considered small businesses, they often have a large impact on their communities through employment. Furthermore, more than 66% of their employees are usually Indigenous People. AEDCs are normally owned by Indigenous governments, with a board of directors appointed by the Chief and Council and the local community as shareholders. These organisations are most prominently found in Ontario and within the industries of construction, energy, property management and tourism. In addition, AEDCs are more likely to use government funding to finance start-up costs rather than funds from personal savings or private businesses (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

Trends in Industries

Data from the Conference Board of Canada (2017) shows that Indigenous entrepreneurs are predominately found in the construction; professional, scientific and technical services; other services (except public administration); agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting industries; and health care and social assistance. However, when comparing male and female entrepreneurs, Indigenous females most commonly work in healthcare and social assistance (18%) while Indigenous males most prevalently work in the construction industry (29.2 %) (The Conference Board of Canada - Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). Furthermore, construction and agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting were the two most common industries where Indigenous entrepreneurs worked in both on-reserve and in rural areas. At an urban level, the construction and professional, scientific, and technical services were the two top industries where Indigenous entrepreneurs worked. In general, Indigenous entrepreneurs are underrepresented in knowledge sectors and occupations while being overrepresented in the construction industry in particular (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016).

Financing

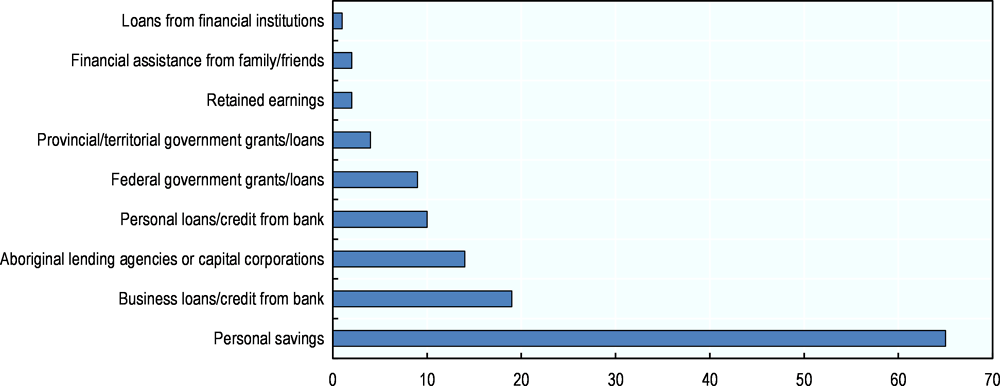

For Indigenous People who do participate in self-employment, the main sources of financing for Indigenous entrepreneur are the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA), Aboriginal Financial Institutions (AFIs), Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and several major Canadian banks (The Conference Board of Canada - Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). However, 65% of Indigenous entrepreneurs surveyed by CCAB stated that they started their business through the use of personal savings (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). Furthermore, only 14% of funding for Indigenous start-ups came from Indigenous lending institutions and 19% from bank or governmental financing. Therefore, some self-employed Indigenous People resort to finding business funding through the use of the personal savings of their family and social networks, credit cards, or revenues from multiple services (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

Future performance

A 2017 business survey shows that 77% of Canadians recognise the importance of thriving Indigenous enterprises for the creation of sustainable economic opportunities. (Sodexo, 2017). 76% of Indigenous entrepreneurs in the CCAB survey also observed net profits in 2015, a 15% increase from 2010 (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). A majority of Canadians also believed that supporting strong Indigenous businesses was an important pathway to healing Canada’s relationship with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians.

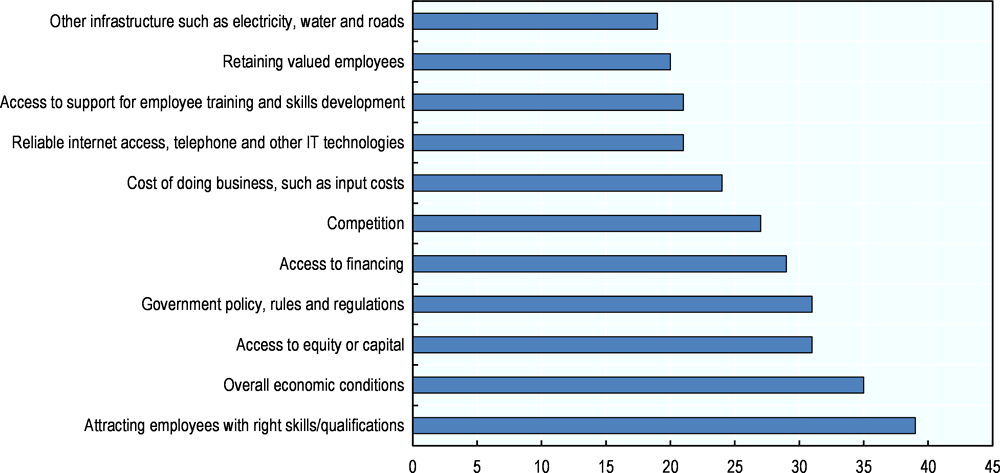

Which barriers are inhibiting the growth and sustainability of Indigenous entrepreneurs and SME owners?

Through the process of starting and managing their own companies, Indigenous entrepreneurs are often met with challenges. The Conference Board of Canada identified these issues as structural, financial, cultural and institutional barriers (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). However, while some barriers remain as significant adversities, like the economic environment for Indigenous entrepreneurs, others can be more easily addressed. Respondents in the CCAB survey stated that while they anticipate several barriers to successful operations, infrastructure is of least concern (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). Through greater understanding of each issue, these barriers can be addressed more suitably.

Financial barriers

Access to capital/equity

Despite the aforementioned avenues for financing, personal savings are often used to fund the majority of Indigenous businesses. Moreover, loans or credits from banks or government programmes are not used by a majority of Indigenous entrepreneurs (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). CCAB data found 56% of Indigenous businesses had difficulty accessing capital for reason such as “a lack of collateral (8%); being a new, high-risks business (8%); having too much debt or poor credit rating (8%); dealing with bureaucracy (8%); and being Aboriginal (7%)” (The Conference Board of Canada - Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

While prevalent, sole proprietorship businesses can often be labelled as high risk and have difficulties lending from banks. Indigenous sole proprieties on-reserve have some benefits, like protection from banks seizing property due to the Indian Act. However, this in turn makes it difficult for them to receive loans since they may not have other assets to offer as collateral. Furthermore, start-up, poor credit ratings, high debt, socio-economic disadvantages, and discrimination can often add to Indigenous sole-proprietors’ label as high-risk in the eyes of leaders (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

Education, financial literacy and capacity

As demonstrated in the previous chapter, there are substantial gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous education and skill outcomes. Furthermore, 68% of Indigenous entrepreneurs state that they have had difficulties finding qualified Indigenous employees (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). Financial literacy can be simply defined as knowledge of financial management. In comparison, financial capacity encapsulates both financial education and opportunities to participate in affordable and reliable financial products and services. The Conference Board of Canada states, “education, literacy, and numeracy challenges combined with the remote nature of many Aboriginal communities and their infrastructure deficits, all play a role in weakening financial literacy. In addition, Collin argues that ‘cultural barriers such as language, values that affect financial decisions, the persistence of non-cash-based economies, lack of trust toward financial institutions, and habituation to government programme management culture of all affect financial literacy’ for Aboriginal entrepreneurs” (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

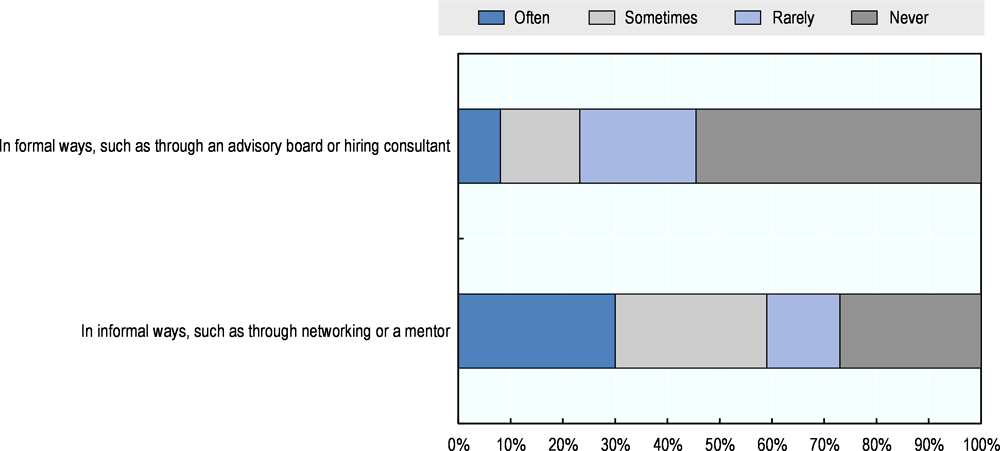

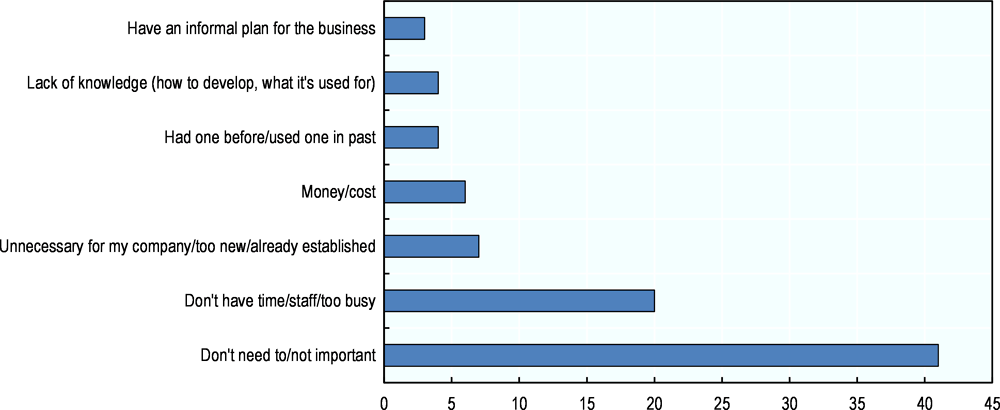

Many Indigenous businesses supply the market with a specialization in the product or service they provide. However, in regards to entrepreneurship and SMEs, less Indigenous People (20.7%) are trained in business and management in comparison to non-Indigenous People (26.8%) (Statistics Canada, 2018). For example, TD Economics reports that only 31% of Indigenous businesses have a formal business plan (DePratto, 2017). Therefore, in instances where Indigenous entrepreneurs lack business training, many of these businesses have the potential to generate more growth and profitability through supports from further education and training. For instance, the possession of a business plan has been correlated to innovation and growth within Indigenous businesses (DePratto, 2017).

Increases in fringe financial services

A lack of access to financial institutions combined with a deficiency in financial capacity have provided an environment for fringe financial services to expand in many Indigenous communities. Fringe financial services, or predatory lending, impact small-sized businesses in particular. The Conference Board of Canada states that “Predatory lending encompasses a wide variety of services, including but not limited to, pawnshops, payday lenders, and cheque cashers, all of which can be very expensive” (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

Geographic barriers impacting Indigenous entrepreneurs

Only 50 branches of major Canadian banks are located in Indigenous communities across Canada (the 50 branches are within the major Canadian banks, such as Bank of Montreal, Toronto Dominion Bank, CIBC, Royal Bank of Canada and Scotiabank). Some Indigenous communities have loan and support programmes. For example, Ulnooweg has been providing loans and business services to Aboriginal entrepreneurs in Atlantic Canada since 1986. However, in many rural communities, there are fewer and less diverse business opportunities compared to more urbanised places or cities with a larger population and stronger density of business activities” (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017).

TD Economics reported that a substantial amount of Indigenous businesses had difficulties with internet access (DePratto, 2017). The 2016 National Aboriginal Business Survey reported that 40% of Indigenous business owners either have no or unreliable internet access (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). This issue is partially related to geography and resources rural entrepreneurs can access (DePratto, 2017).

Which policies and programmes have been implemented to foster entrepreneurial and SME growth and sustainability for Indigenous People?

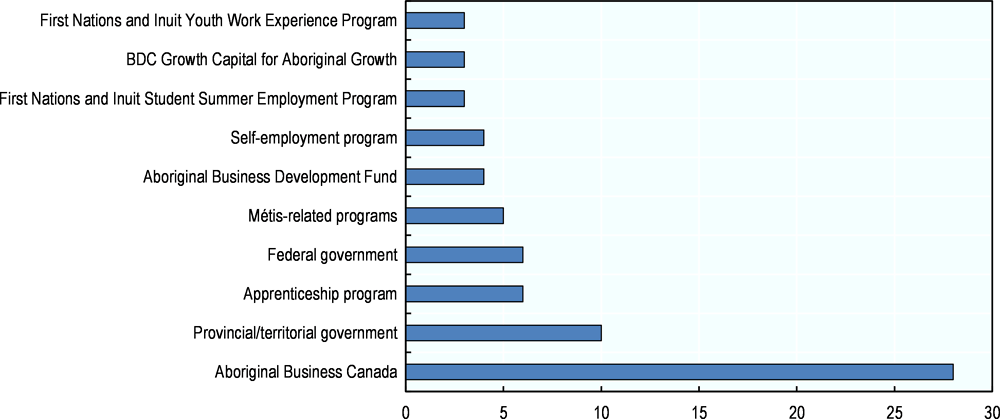

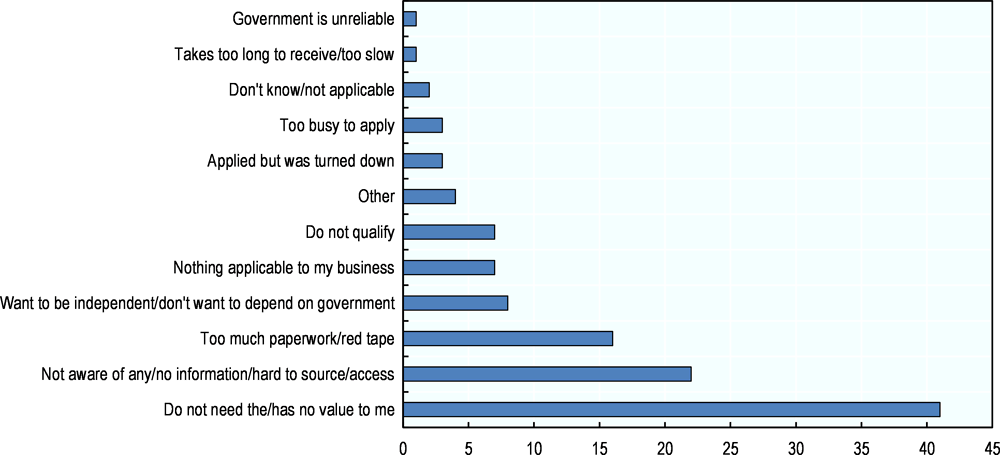

Despite barriers in starting and growing businesses, Indigenous entrepreneurs are optimistic, nearly three-fourths surveyed in CCAB’s 2016 Aboriginal Business Survey felt their business would still be operating in five years (The Conference Board of Canada - Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). But to increase growth and profitability, there are untapped resources in which Indigenous entrepreneurs can capitalise. In their 2016 survey of Indigenous businesses, the CCAB asked about participation in governmental programmes. 43% of respondents had participated in any governmental programme. Of this group, the governmental programme most frequently referenced was Aboriginal Business Canada (a programme no longer operating). Through greater access, creation and expansion of current programmes, both Indigenous entrepreneurs and the Canadian economy can benefit from business growth. There are some good examples below of existing programmes and policies, which aim to provide more entrepreneurship opportunities to Indigenous People.

First Nations Bank of Canada

The First Nations Bank of Canada is the first Canadian chartered bank to be independently controlled by Indigenous shareholders. The First Nations Bank of Canada provides financial services to Indigenous People and is an advocate for the growth of the Indigenous economy and the economic well-being of Indigenous People. The Bank aims to increase shareholder value by participating in and promoting the development of the Indigenous economy.

The Bank was conceived and developed by Indigenous People, for Indigenous People and regards itself as an important step toward Indigenous economic self-sufficiency. The strategic directive of the founding shareholders was to grow the Bank and increase Indigenous ownership to the point that the Bank would be controlled by a widely held group of Indigenous shareholders. The Bank is over 80% owned and controlled by Indigenous shareholders from Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Quebec (First Nations Bank of Canada, 2018).

The Canadian Centre for Aboriginal Entrepreneurship (CCAE)

The CCAE has assisted more than 75 business owners to start their new firm. CCAE provides entrepreneurship training, consultation services, speaking and writing services, and project management recommendations (Canadian Centre for Aboriginal Entrepreneurship, 2017). The Aboriginal Best (Business and Entrepreneurship Skills Training) programme of CCAE has worked with 95 Indigenous communities, including more than 2 000 participants (Canadian Centre for Aboriginal Entrepreneurship, 2017) (Aboriginal Business & Entrepreneurship Skills Training, 2018).

Aboriginal Women’s Business Entrepreneurship Network

The Aboriginal Women’s Business Entrepreneurship Network (AWBEN) was initiated in December 2012 by Native Women’s Association of Canada. It was created to:

-

Provide a safe, supportive, collaborative, empowering and culturally supportive environment that addresses the unique challenges of female Indigenous entrepreneurs and aspiring female Indigenous entrepreneurs;

-

Enhance, develop and accelerate growth for current and aspiring female Indigenous entrepreneurs in a sustainable way through programs and resources, and

-

Promote community leadership through volunteerism as a reflection of respect and reciprocity and will be paramount to the foundation of the Aboriginal Women's Business Entrepreneurship Network.

Understanding how entrepreneurship and SME policies are being implemented through case study analysis

MAWIW Council

Isolated First Nations communities face several barriers in pursuing economic development opportunities. The remoteness factor of communities’ means limited outside traffic and this has a big impact on corporations wanting to invest in the area. This often limits diversity in economic development opportunities on Indigenous communities, as most organisations or businesses that come to town are related to mining. Thus, giving members limited employment choices. Secondly, politics plays a role in creating economic development opportunities, as Chiefs and Councils on-reserve serve two year terms. This presents a huge limitation as community leaders are unable to carry out long-term goals because they are constantly campaigning for a re-election. Though, there is a political shift happening in many communities to have four year terms for their leaders, it is not a reality in every community. This limits economic growth in MAWIW First Nations’ communities. There are Economic Development Officers (EDOs) situated in each community to assist members with capacity development. These efforts are supported by JEDI, as they provide specific programmes and service to help individuals start up their own businesses.

On the other hand, MAWIW Council does not offer direct programmes for economic development or entrepreneurship programmes in their communities, as their primary focus is on providing employment and training services. However, JEDI works closely with all First Nations’ communities to offer economic development and entrepreneurship services. One good example is the Business Incubator Program (see Box 3.1).

Indigenous Business Incubator Program provides entrepreneurs with knowledge of business basics like preparing customized business plans, accessing funding and how to effectively market their products and services. In this 10 week programme which focuses on tourism, trades and technology, individuals can also receive mentorship from experienced entrepreneurs working in the same field. The Indigenous Business Accelerator Program on the other hand helps individuals gain business knowledge in the aerospace and defence industry, with employment in, Information Communication Technology (ICT), Industrial Manufacturing, Security, Clean Energy and Consulting. Participants of this programme also get access to key resources such as venture capital funds, research and development organisations and meeting with players in the industry (Joint Economic Development Initiative, 2018). Thus, community members are able to access entrepreneurship services through JEDI; however, with limited capacity, not everyone is able to take advantage of the programmes.

Community Futures Treaty Seven (CFT7)

In the area of entrepreneurship, CFT7 builds the Treaty Seven economy through community economic development and entrepreneur capacity building in order to assist and support Treaty Seven First Nations and their members towards economic success. This includes a general loan fund where loans are provided to establish or expand a business. In these cases, business must be at least 51% owned by Treaty Seven Members and the maximum loan per business is 25 000 CDN. All loans require equity of 10% (or proof of sweat equity) and they are provided to businesses located on and off-reserve. All loans require community support through a Band Council Resolution (on-reserve only) and there must be a business mandate to increase the employment of Treaty Seven Members over the long-term.

CFT7 has also a business development programme, which provides technical assistance to Indigenous entrepreneurs. This programme offers support to review business plans; assist in the creation & development of a business, counselling; identifying potential market opportunities; entrepreneurial training as well as small business workshops and entrepreneurial training available upon request.

CFT7 also operates First Nations Youth Entrepreneur Symposium which includes some team building and risk taking activities. This is an annual event and the symposium concludes with a banker’s panel in which participants present a draft business plan for feedback on how to improve and make the business plan bankable. Qualified trainers are usually onsite to assist with the development of the business plan.

Kiikenomaga Kikenjigewen Employment & Training Services (KKETS)

Related to the lack of education is the absence of business knowledge, which creates a barrier for entrepreneurial members of the community population that want to start up their own business. The ASAP programme offers an entrepreneur credit, an elective course to those who want to learn more about being an entrepreneur. The course teaches participants how to write a business plan and the major requirements of opening up a business. Due to funding limitations, KKETS does not offer any additional services or programmes for entrepreneurs where they can seek help as they go through the process of starting their own business.

The Centre for Aboriginal Human Resources and Development

CAHRD does not offer specific training related to entrepreneurship. In the past, business development programmes were offered by the Neeginan Centre under pilot funding but they were not continued. The Centre has created a social enterprise - Mother Earth Recycling, which has been operating under the auspices of Neeginan Centre and CAHRD (see Box 3.2).

Mother Earth Recycling (MER) is a Winnipeg-based Indigenous social enterprise. The goal of the social enterprise is to provide meaningful training and employment opportunities to the Indigenous community through environmentally sustainable initiatives. MER began in 2012 as a partnership between Neeginan Centre, the Centre for Aboriginal Human Resource Development, and the Aboriginal Council of Winnipeg, as a place for community members to find training and job opportunities, while providing a much-needed service to the City. MER offers mattress, box springs, and e-waste pickup and drop off from residential homes, businesses, and industries across Manitoba. Part of the early success of MER is due to its innovative collaboration and partnerships. The owners and all three levels (e.g. municipal, provincial and federal) of government have invested resources in the development of MER. Public participation and support have also greatly contributed to its success. The act of recycling has cultural significance for Indigenous communities in Canada. Embedded within traditional Indigenous worldviews is the concept of collective responsibility to respect and maintain the natural environment, and use only what is needed for sustenance. The commitment to environmental sustainability enables Indigenous employees to reconnect with an integral part of their culture.

Critical success factors identified from the case studies

Evidences of entrepreneurial best practices were present throughout the case studies examined in this report. These examples of successful Indigenous enterprises in turn provide helpful lessons for continued success among all Indigenous businesses. Many of case studies looked to changes in both financial institutions and entrepreneurial education as areas that can improve to produce even higher results.

Making financial capital more accessible

The case studies’ showed that financial institutions and Indigenous entrepreneurs appear to be disconnected in regards to financial capital. With 65% of Indigenous entrepreneurs using their personal savings as funding, financial institutions have ample room for growth in their support for Indigenous businesses (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). When Indigenous entrepreneurs have better access to loans and credit, more jobs can be created through new enterprises and maintained through stable finances (The Conference Board of Canada, 2017).

While several financial institutions would like to lend to more self-employed Indigenous People, poor credit scores can prevents some entrepreneurs from participating. Considering funding barriers, alternative financing can be found through a greater use of micro loans. The amounts lent would be smaller and easier to manage, allowing Indigenous borrowers to consistently increase their credit ratings. Additionally, credit building programmes also offer ways to allow Indigenous entrepreneurs to change their credit ratings in a structured and accountable environment (The Conference Board of Canada, 2017).

Furthermore, more funds could be allocated to Aboriginal Financial Institutions (AFIs) to support more start-up ventures and to support the growth of more mature ventures as well. Currently only 22% of Indigenous businesses survey stated that they were seeking further growth and expansion (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). The number of Indigenous businesses that could move into positions of growth and expansion could rise dramatically if they had reliable and more extensive funds beyond their personal savings. The profits from these companies could in turn boost their local, regional and national economy.

Closing financial literacy and capacity gaps

With increases in access to financial capital, case studies indicated that there should be equal attention given towards the education of Indigenous borrowers in financial literacy and capacity. In particular, there are gaps in participation and outcomes for some groups of Indigenous entrepreneurs, such as youth and women, which show that they need even further support. These educational initiatives can allow Indigenous entrepreneurs the ability to make the most of their new resources.

One of the easiest ways to target Indigenous entrepreneurs seeking financial capital is to attach financial literacy and capacity education to lending requirements. Banks and other financial institutions can work with local stakeholders to create programmes highly relevant to Indigenous borrowers. These programmes would protect the credit rating of Indigenous entrepreneurs while also reducing risks in noncompliance of loan repayments (The Conference Board of Canada, 2017).

While there are still fewer women entrepreneurs compared to men, a large portion are women. Women entrepreneurs also report requiring fewer funds to start their business. Therefore, micro-lending could be a beneficial solution to their business needs in some cases. However, Métis Financial Institutions report that micro lending can sometimes be more of a burden than the funds are worth in terms of administrative requirements. Therefore, women should be educated about the benefits and disadvantages of each option to select the most appropriate method needed to finance their businesses (The Conference Board of Canada, 2017).

With one fifth of Indigenous entrepreneurs less than 25 years old (compared to on 15% of non-Indigenous entrepreneurs), financial institutions need to prepare their programming and educational services to be marketed to younger audiences as well. With far less experience managing personal funds as well, these entrepreneurs will need to be exposed to holistic financial literacy and capacity training to ensure that they have been exposed to all aspects of financial management. Finally, these entrepreneurs may need additional assistance meeting additionally requirements needed when applying for loans or credit (The Conference Board of Canada, 2017).

Note

1. However, the population of Indigenous entrepreneurs recorded by the 2011 NHS possibly underestimates the number of on-reserve entrepreneurs. The 2015 Canadian Business Patterns (CBP) data from the Statistics Canada Business Register shows 10 000 businesses located on-reserve (compared to 3 000 captured by the 2011 NHS) (The Conference Board of Canada – Northern and Aboriginal Policy, 2017). Moreover, TD Economics reported that about 2% of registered SMEs in Canada (e.g. around 32 000 businesses) were owned by Indigenous People (DePratto, 2017). Due to different sources and metrics for measuring the presence of Indigenous entrepreneurs and SME owners, it is difficult to obtain a consistent figure on the prevalence of Indigenous businesses in Canada.

References

Aboriginal Business & Entrepreneurship Skills Training (2018), Aboriginal Entrepreneurship & Business Skills Training, http://aboriginalbest.com/ (accessed on 13 February 2018).

Canadian Centre for Aboriginal Entrepreneurship(2017) Aboriginal BEST, http://www.ccae.ca/aboriginal-best/ (accessed on 23 October 2017).

Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (2016), Promise and Prosperity: the 2016 Aboriginal Business Survey, https://www.ccab.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/CCAB-PP-Report-V2-SQ-Pages.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2017).

DePratto, B. (2017), Aboriginal Businesses Increasingly Embracing Innovation, TD Economics, https://www.td.com/document/PDF/economics/special/AboriginalBusiness2017.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2017).

Drummond, A. (2017), The Contribution of Aboriginal People to Future Labour Force Growth in Canada, Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

Joint Economic Development Intiative (2018), Annual Report 2016-2017.

Statistics Canada (2011), Calculations based on Public Use Microdata File, http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/pumf-fmgd/index-eng.cfm.

The Conference Board of Canada - Northern and Aboriginal Policy (2017), Opportunities to improve the financial ecosystem for Aboriginal entrepreneurs and SMEs in Canada, NACCA and BDC, http://nacca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ProjectSummary_NACCA-BDC_Feb14_2017.pdf.