Chapter 6. A multi-level model of vicious circles of socio-economic segregation

This chapter develops a multi-level conceptual model of segregation, by using three conceptual levels – individuals and households, generations, and urban regions. Different socio-economic groups sort into different types of neighbourhoods and other domains, leading to patterns of segregation at the urban regional level. At the same time exposure to different socio-economic contexts also affects individual outcomes, and this subsequently leads to sorting processes into neighbourhoods and other domains. This vicious circle of sorting and contextual effects continuously crosses the three levels, and leads to higher levels of segregation. The chapter concludes with a discussion of several intervention strategies that focus on breaking the vicious circles to improve cities as places of opportunities by investing in people, in places and in transport.

Introduction

Income inequality has increased in many countries and as a result the gap between the poorest and the richest in society is the largest in 30 years (OECD, 2015). Although there are differences in the timing, intensity and directions of changes across countries (OECD, 2008), generally speaking higher income groups have benefited more from economic growth than lower income households. In particular, higher skilled people have seen their incomes rise, while those with fewer skills have not kept up (OECD, 2015).

Rising inequality in incomes and wealth (Piketty, 2013) is a major concern because it also influences inequality in other life domains, and has consequences for the education, health, life expectancy, employment prospects and wages of individuals. It can be expected that the higher the level of social inequalities in a society, the more difficult it is to experience upward social mobility because of the large socio-economic distance between lower and higher status groups. This is related to the idea that higher social inequalities reduce intergenerational social mobility (as in the Great Gatsby Curve phenomenon, see Krueger, 2012). On a societal level, inequality can harm social stability, and reduce trust in governments and institutions, and could even put at risk democratic processes as lower income groups become disengaged with politics (OECD, 2015).

Inequality has a clear spatial footprint in cities, where rich and poor people often live segregated in different neighbourhoods (Tammaru et al., 2016). In this chapter, the term segregation is used for the spatial separation of two or more groups in different domains of daily life, including residential neighbourhoods, schools and workplaces. Segregation can also occur in flows, for example when different population groups use different transport modes or the same transport at different times, as well as in digital space, for example in the form of digital communities (Tubergen, 2017). The main focus of this chapter is on spatial segregation in residential neighbourhoods, but segregation in schools and workplaces is also discussed.

Since 2001, socio-economic residential segregation of the rich and the poor has increased in many European cities. The international comparative study “Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities. East Meet West” (Tammaru et al., 2016) compares levels of socio-economic segregation in 2001 with that of 2011 in 12 European cities: Madrid, Tallinn, London, Stockholm, Vienna, Athens, Amsterdam, Budapest, Riga, Vilnius, Prague and Oslo (in order of decreasing levels of segregation). To put this in perspective it is important to mention that segregation in European cities is still relatively low compared to cities in, for example, Asia or North America. The comparative study identifies rising inequality as a major cause of increasing segregation (Musterd et al., 2017).

Like in most US cities, also in many European cities the rich live more concentrated than the poor (Florida, 2015); this is largely the case because higher income groups have more freedom in choosing where they want to live than lower income groups. Those with money sort into the most desirable neighbourhoods and communities by “voting with their feet”. Households with similar tastes and incomes choose to live together in the same communities where (public) services are best. Similarly, local communities compete to attract households by providing high quality services. This so-called Tiebout sorting effect (Tiebout, 1956) leads to the unequal distribution of services and segregation by income and social status (Corcoran, 2014). The sorting of higher income households into the most desirable neighbourhoods and communities increases house prices in these areas. This limits the choice of lower income groups who end up concentrated in those neighbourhoods where housing is cheap.

For those who live in the poorest neighbourhoods in cities, their residential neighbourhood is often the result of a lack of choice; they live there where there is a spatial concentration of affordable housing. The more clustered affordable housing is in a city, the more rapidly segregation levels rise. Segregation is deemed to be especially problematic when it is involuntary and when there are negative side effects of growing up and living in large spatial concentrations of poverty (Tammaru et al., 2016). Although the negative effects of the Tiebout sorting process are mediated by centrally co-ordinated provision of services, such as schools (Corcoran, 2014), it is still the case that in deprived communities, for example, school quality is lower than in more affluent communities.

The spatial concentration of poverty in neighbourhoods can have negative effects on the outcomes of individuals, especially for children. There is an ongoing debate on whether high levels of deprivation in certain neighbourhoods simply reflect the population composition of these neighbourhoods, or whether there are also additional negative contextual neighbourhood effects on individual outcomes. There is increasing evidence of negative neighbourhood effects of growing up in deprived neighbourhoods on outcomes of children, adolescents and adults (Hedman et al., 2015; Chetty et al., 2016). In many places, segregation by income also has ethnic and racial dimensions and it is often the case that non-Western immigrants and their descendants live concentrated in low income areas. Immigrants might therefore be more likely to suffer the consequences of negative neighbourhood effects.

The aim of this chapter is to come to a better understanding of the links between social inequalities and socio-economic segregation. Most of the segregation literature focusses on better understanding ethnic and racial dimensions of separation and processes behind socio-economic segregation have received less attention. As said before, the two dimensions of segregation are strongly connected; income differences are often also at the heart of ethnic and racial inequalities and as a result of differential sorting of ethnic and social groups into different housing and neighbourhood types of the city; overlapping overlap social, ethnic, housing and spatial disadvantages is the outcome.

This chapter will develop a multi-level conceptual model of segregation, by using three conceptual levels – individuals and households, generations, and urban regions – and the idea of vicious circles. As different socio-economic groups sort into different housing segments and residential neighbourhoods and other domains (work, school, leisure), at the aggregate level of urban regions patterns of segregation emerge. As a result of the sorting processes, individuals are exposed to concentrations of higher and lower income groups in their residential neighbourhood and other life domains. This sorting of people into different domains is not independent as, for example, children often go to a nearby school. As a result, children who grow up in a poverty neighbourhood often also go to a school with a low socio-economic status. The exposure to poverty concentrations in different domains affects individual outcomes through negative contextual (neighbourhood) effects. This creates vicious circles of sorting and contextual effects, which continuously cross levels and generations, and which leads to segregation at the level of cities and regions. For example, the concentration of poverty of the neighbourhood where parents live influences (or is related to) the concentration of poverty of their children’s school, and this will affect the outcomes of these children later in life (through contextual school and neighbourhood effects). There is strong intergenerational transmission of poverty and living in poverty neighbourhoods from parents to children, and these children affect their own children as they grow up (van Ham et al., 2014; De Vuijst et al., 2017; Hedman et al., 2017). These individual outcomes, in turn, reinforce the sorting of different socio-economic groups into different neighbourhoods. At the aggregate level of cities and regions this vicious circle contributes to spatial segregation by income in each of the domains (van Ham and Tammaru, 2016). Hence, housing and spatial inequalities have become a crucial part of the structures of inequalities in European cities.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. The next section presents a brief summary of changes of socio-economic segregation in European cities is presented. The third section outlines the main contours of a multi-level conceptual model of socio-economic segregation. Finally, the last section discusses some of the policy implications with a focus on breaking the vicious circles of segregation and improving cities as places of opportunities by investing in people, places and transport.

Background

Fundamentally, socio-economic segregation in cities is a symptom of income and wealth inequality (Tammaru et al., 2016; van Ham et al., 2016). The extent to which inequality leads to spatial segregation is strongly related to welfare and housing market systems, and to the spatial organisation of the urban housing market (van Ham et al., 2016). The type of welfare and housing market system in a country can either soften or enhance the effects of income inequality (Musterd and Ostendorf, 1998). Europe generally has a tradition of strong welfare states compared to the rest of the world (Esping Andersen 1990), and because of this, the level of segregation in European cities, although growing, is still low compared to the rest of the world; the most segregated cities in Europe are still less segregated than most major cities in the United States (Florida, 2015).

Urban planning shapes segregation patterns as well. Every city has spatial concentrations of low and high cost housing. In many European cities, from the 1950s to the 1980s, there was a great demand for affordable housing related to rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. Especially in the 1960s and 1970s, this resulted in the development of large housing estates, often consisting of social or public housing, and often at the edges of cities (Hess et al., 2018). A good example is the “million home programme” in Sweden, where one million (mostly public rented) homes were built in only 15 years (Andersson and Bråmå, 2018). Initially these housing estates housed the middle classes, but from the late 1970s these estates became the areas of residence of lower income households and immigrant families (due to relative depreciation as a result of better alternatives for the middle classes). The strong spatial clustering of social and public housing has led to very high levels of segregation by income and ethnicity in many cities.

Not only income differences but also the housing allocation systems in the social housing sector can contribute to segregation. In, for example, the Netherlands and the UK, social housing was originally allocated through waiting lists, but now most social housing is allocated using choice-based letting systems. In these systems households can express preferences with regard to the dwelling and neighbourhoods, and as a result, those most in need of urgent housing, end up in the least desirable housing stock (Manley and Van Ham, 2011). The choice-based letting system also contributes to segregation by ethnic background (van Ham and Manley, 2009). Especially upon arrival, immigrants have the most urgent need of housing. In European cities, among the inhabitants of affordable housing, people with an immigration background are often overrepresented, and hence, social, ethnic, housing and neighbourhood inequalities overlap, reinforced by the increase of marketisation of the housing sector. In some cities, such as Stockholm, where low cost housing is highly concentrated in some parts of the city, and where marketisation of the housing sector is high, levels of segregation have risen quickly as well (Andersson and Kährik, 2016).

Although segregation by income as a social phenomenon is often seen as problematic, this is not necessarily the case from the perspective of individuals. Segregation can also be positive if it is the result of free choice. The most affluent households often live the most segregated as they have the income to choose neighbourhoods of their own preference. But also less affluent households can live segregated by choice. The literature clearly shows that households tend to choose neighbourhoods with people who are very similar to themselves in terms of income, class, ethnicity and religion (Feijten and van Ham, 2009; Schelling, 1969, 1971; Clark, 1991). Living among similar people can have major benefits as it can reduce conflict, give people a sense of safety, and foster social networks. Living in enclaves with people with similar preferences, needs, and life styles can also have the benefit of shared services and facilities (such as shops, cultural and religious facilities).

Extreme levels of ethnic and socio-economic segregation are often perceived as undesirable by (local) governments, even more so when such segregation is involuntary. When individual choice gets restricted or when people face discrimination on the housing market, segregation becomes problematic also from the individuals’ perspective. Especially the process of residualisation of social housing, as is quite common in many European countries, has limited the housing choice of low-income groups (Kleinhans and van Ham, 2013). Citizens, but also local and national governments, express concern over increasing inequality and spatial segregation in European cities. There is the risk that when the more affluent and the poor live more and more separate lives, this might lead to estrangement and fear for others. This is especially the case when there are very clear spatial borders within cities; such as gated communities for the affluent who separate themselves from the rest of the population, and so-called no-go-areas with extreme concentrations of poverty and high levels of crime. It has been argued that such extreme spatial separation can lead to social unrest, and even conflict and riots (Tammaru et al., 2016). The riots in Paris (2005), London (2011) and Stockholm (2013) cannot be seen separate from high concentrations of poverty in these cities, often in combination with high levels of ethnic segregation (Tammaru et al., 2016).

There is also a large literature on neighbourhood effects which suggests that living in poverty concentration neighbourhoods can have negative effects on individual outcomes such as health, income, education and general well-being (van Ham et al., 2012). There is increasing evidence that such effects especially harm children who grow up in poverty concentration neighbourhoods (Hedman et al., 2015; Chetty et al., 2016). And there is also recent evidence that living in deprived neighbourhoods harms the earnings of adults, even after controlling for non-random selection into residential neighbourhoods (van Ham et al., 2017). Potential causal mechanisms run through socialisation effects, negative peer group effects, but also stigma effects, and a lack of social networks to find a job. Also living in neighbourhoods which are spatially cut off from centres of employment are expected to harm the employment prospects of residents. As a result, living in poverty concentration neighbourhoods can harm the potential of adults and children.

Recent studies by van Ham et al. (2017), and a re-evaluation of the Moving to Opportunity experiment by Chetty et al. (2016) have shown strong evidence of neighbourhood effects. These results give reason for concern about increasing levels of socio-economic segregation. These concerns are further fuelled by the fact that socio-economic and ethnic segregation are often strongly connected to each other, and segregation is repeated over multiple life domains. For example, residential segregation in Sweden was found to be strongly related to workplace segregation (van Ham and Tammaru, 2016). There is no simple one-on-one relationship, but many first and second generation immigrants from outside the European Union belong to the lowest income groups and live concentrated in the lowest income neighbourhoods of cities (see Kahanec et al., 2010). Research clearly shows that, especially for low income non-western ethnic minorities, there is strong intergenerational transmission of living in low income neighbourhoods: children who grow up in low income neighbourhoods are very likely to live in similar low income neighbourhoods as adults (Hedman et al., 2015; De Vuijst et al., 2017).

To conclude, the most important cause of socio-economic segregation is income inequality, which has increased in Europe in the last 30 years. This increase is strongly connected with macro-level factors such as globalisation and restructuring of the labour market (Sassen, 1991; Hamnett, 1994; Tammaru et al., 2016). In a globalised economy, highly-skilled workers can sell their labour across the globe that drives up their incomes, while low-skilled workers face the competition with workers from other countries that put their wages under pressure or leaves them without a job. Those who are not able to adapt to a changing economy and labour market, can thus fall into long term poverty. Globalisation of the labour market has happened in parallel with the marketisation of the housing sector. Generally speaking it can be expected that more market involvement in housing contributes to a firmer relation between income disparities and segregation as the lowest income households sort into the cheapest housing stock which is often spatially concentrated in certain neighbourhoods. Hence, both income inequalities and levels of socio-economic segregation have risen in European cities.

Vicious circles of segregation at the individual and household level

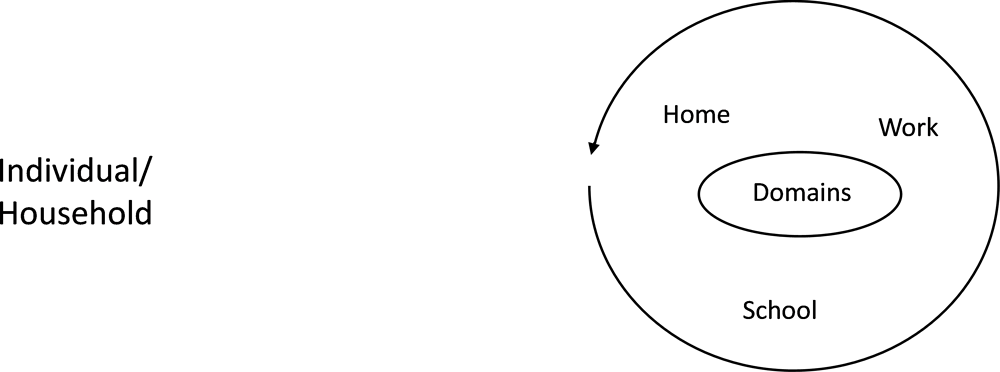

Segregation, in the sense of spatial separation of two or more groups, does not only take place in residential neighbourhoods, but also in other domains such as schools and workplaces. Segregation is traditionally measured at the level of residential neighbourhoods, which makes sense both conceptually and empirically (van Ham and Tammaru, 2016). The home is where people live, it is the starting point of their daily activities and their neighbourhood strongly reflects their socio-economic status. Neighbourhoods are also still a crucial place of interaction with others, especially for certain groups such as children, parents of children, the elderly, and ethnic minorities (Van Kempen and Wissink, 2014). Empirically, most census based countries only collect data on the residential locations of households (census tracts, postcode areas, or grid cells), and not for other domains in life, such as work, school and leisure. So residential neighbourhoods have been the natural units to measure segregation.

However, the concept of segregation (by income, ethnic background, etc.) is also relevant for other domains in life (van Ham and Tammaru, 2016). Segregation has also been found in work places (Bygren, 2013; Ellis, Wright and Parks, 2004, 2007; Glitz, 2014; Strömgren et al., 2014), at the level of individual households (Dribe and Lundh, 2008; Haandrikman, 2014; Houston et al., 2005; Kalmijn, 1998), for places of leisure time activities (Kamenik, Tammaru and Toomet, 2015; Schnell and Yoav, 2001; Silm and Ahas, 2014), schools (Andersson, Osth, and Malmberg, 2010; Malmberg, Andersson and Bergsten, 2014; Reardon, Yun and McNulty Eitle, 2000), and transport (Schwanen and Kwan, 2012). Different socio-economic or ethnic groups use different modes of transport, or travel at different times of the day. Very early in the morning, the underground system in major cities is populated by cleaners and other lower status service workers, while during the traditional rush hour times, the system is populated by white collar workers. Also different lines in the same city are populated by different groups at the same time of the day. Segregation can also take more a-spatial forms in social networks and virtual domains such as social media (Joassart-Marcelli, 2014). Using data from Facebook, Hofstra et al. (2017) showed that large online networks are more strongly segregated by ethnicity than by gender.

Socio-economic segregation and ethnic segregation are strongly connected since immigration tends to bring along polarising effects on the labour market (Sassen, 1991). Ethnic minorities are often overrepresented in certain niches of the labour market with less secure labour contracts and lower pay levels and, as a consequence, they sort into the poorest neighbourhoods of cities where affordable housing is available. These low cost neighbourhoods used to be in the inner cities, but in the last three decades, the highest concentrations of poverty groups and ethnic minorities have formed in modernist high-rise housing estates built in the late 1950s through the early 1980s. As the gentrification process of many inner cities proceeds, the suburbanisation of low-income groups has become a new important trend in European cities (Musterd et al., 2017).

A study in Sweden found that segregation in residential neighbourhoods is connected with segregation at workplaces (Strömgren et al., 2014). This study used longitudinal, georeferenced Swedish population register data, which enabled them to observe all immigrants in Sweden in the 1990–2005 period, and fixed-effects regressions. In line with previous research they found lower levels of workplace ethnic segregation than residential segregation (Strömgren et al., 2014). Their main finding was that low levels of residential segregation reduce workplace segregation, even after taking into account unobserved characteristics of immigrants’ such as willingness and ability to integrate into the host society. Differences in labour market outcomes, in turn, affect housing choice or the lack of thereof and, hence, residential segregation. A recent book from the United States by Krysan and Crowder (2017) describes cycles of racial segregation in the US. Analyses of national-level surveys and in-depth interviews with people in Chicago showed that everyday social processes shape residential segregation, and that everyday life domains are heavily intertwined.

A domains approach to understanding linked residential, school and workplace careers over the life course, focussing on ethnic and racial segregation is presented in van Ham and Tammaru (2016). This framework can also be used to understand socio-economic segregation. There are two mechanisms through which the exposure of individuals and households to poverty concentrations in different domains is connected. The first mechanism runs largely through direct spatial proximity. For example, children often go to a school close to their home, and as a result the socio-economic composition of the neighbourhood and local schools often overlap. This is even more the case in systems with school districts. The very concept of neighbourhood was based on the idea of school districts (Perry, 1929) and until today, schools are often neighbourhood based. Also leisure time activities often take place close to home (Kukk et al., 2017) and as a result people often socialise with people from the same urban areas.

The second mechanism runs through contextual effects (see also next section on intergenerational mechanisms). For example, children growing up in neighbourhoods with high concentrations of low income households will mostly go to schools where most children come from low income families. The school composition is likely to affect the test scores of children, their social networks, the educational choices that they make later in life, and ultimately their job finding networks and opportunities later in life. This will in turn have an effect on sorting of these children as adults into different residential neighbourhoods and other domains. And as a result there is a vicious circle of exposure to poverty concentrations through sorting, contextual effects and subsequently sorting. On the aggregate level this vicious circle will contribute to patterns of segregation in multiple domains, as illustrated in Figure 5.1.

An important element of the domains approach is time. Individual lives consist of a sequence of residential episodes in different neighbourhoods. Living in a poverty concentration neighbourhood for a short period of time in a certain stage of your life can be expected to have a widely different effect on individual outcomes than a lifelong exposure to high poverty neighbourhoods or poverty in other domains. When taking a life course approach, the interlinkages of exposure to poverty in different domains can be seen within a longer time period and over the generations.

Intergenerational vicious circles of segregation

The idea of the vicious circle of exposure to poverty concentrations partly runs from parents to children. It is well known from the sociological literature that “the fortunes of children are linked to their parents” (Becker and Tomes, 1979, 1153), and that individual characteristics, such as incomes and educational attainment, correlate strongly between parents and their children (D’Addio, 2007). The extent to which socioeconomic (dis)advantage is transmitted between generations is receiving increasing attention (van Ham et al., 2014). According to the UK government report Opening Doors, Breaking Barriers: A Strategy for Social Mobility “In Britain today, life chances are narrowed for too many by the circumstances of their birth: the home they’re born into, the neighbourhood they grow up in or the jobs their parents do. Patterns of inequality are imprinted from one generation to the next” (Nick Clegg, Cabinet Office, 2011). The liberal objective to break the links between ascribed or inherited characteristics and individual outcomes is now an important policy objective in many countries, and advocated for both equity and efficiency reasons (OECD, 2010; see also van Ham et al., 2014).

It has been suggested that the intergenerational transmission of socio-economic status also has a spatial dimension (Duncan and Raudenbush, 2001; Jencks and Mayer, 1990; Samson and Wilson, 1995; van Ham et al., 2012; van Ham et al., 2014). And indeed it has been found repeatedly that children who grow up in a deprived neighbourhood are more likely than others to live in a similar neighbourhood when they become adults (van Ham et al., 2014). As a consequence, exposure to poverty concentrations reproduces itself over generations, and hence also segregation itself is reproduced. The neighbourhood outcomes of children are related to the neighbourhood status of their parents, and when these children become adults themselves, their neighbourhood status will affect the type of neighbourhoods their children will live in.

An important mediator of intergenerational transmission of poverty pertains to education. Children who grow up in a deprived neighbourhood are likely to also go to a school with children from low income family backgrounds, which subsequently can have an effect on their level of education, their job finding networks, and eventually their labour career. Ultimately this then affects the type of neighbourhoods they will live in as adults. So intergenerational transmission of living in poverty concentration neighbourhoods might cause neighbourhood effects on individual outcomes, and subsequently influence neighbourhood outcomes, leading to intergenerational neighbourhood effects.

Studies on the intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood type have only emerged in the last ten years. One of the first studies is by Vartanian et al. (2007), using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics linked with US Census data (see also van Ham et al., 2014). This study showed that childhood neighbourhood disadvantage has negative effects on adult neighbourhood type for those growing up in the poorest neighbourhoods. Vartanian et al. (2007) argue that family poverty and the likelihood of living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods is inherited across generations and they explain this intergenerational transmission using neighbourhood effects theory. They suggest that children growing up in poverty areas will experience negative neighbourhood effects on their income and employment opportunities, limiting their subsequent options in the housing market as an independent adult (see also van Ham et al., 2014).

Another US study showed that the intergenerational transmission of living in poverty neighbourhoods results in intergenerational transmission of racial inequality in individual outcomes, as black Americans were more likely to continuously live in deprived neighbourhoods than others, and thus to be exposed to local concentrations of deprivation (Sharkey, 2008). Sharkey (2008) shows that more than 70% of the African-American children who grow up in the most deprived areas of the US live in very similar types of neighbourhoods when they are adults. In another study it was suggested that intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood might run over multiple generations (Sharkey and Elwert, 2011). In his book “Stuck in place”, Sharkey (2013) emphasises the racial dimensions for especially the poor African-American families in the United States (see also Hedman et al., 2017). “The problem of urban poverty […] is not only that concentrated poverty has intensified and racial segregation has persisted but that the same families have experienced the consequences of life in the most disadvantaged environments for multiple generations” (Sharkey, 2013, 26, italics in original as quoted in Hedman et al., 2017).

A study using Swedish individual level geo-coded longitudinal register data by van Ham et al. (2014) also showed strong evidence of intergenerational transmission of living in poverty concentration neighbourhoods. It was found that after leaving the parental home, the characteristics of the parental neighbourhood continue to affect the neighbourhood outcomes of children, even after controlling for parental income levels and the education of children. Very similar effects were found for the Netherlands by De Vuijst et al. (2017). Interestingly, while spatial patterns of ethnic minority groups within Dutch and Swedish society are not directly comparable to American “black neighbourhoods”, intergenerational neighbourhood patterns were still shown to be much stronger for ethnic minorities than for other groups (van Ham et al., 2014; De Vuijst et al., 2017). The study by De Vuijst et al. (2017) on data from the Netherlands also showed that obtaining a degree in higher education is a way to break the link between neighbourhood outcomes for parents and children, but only for the native Dutch population, and not for individuals from ethnic minority groups (De Vuijst et al., 2017).

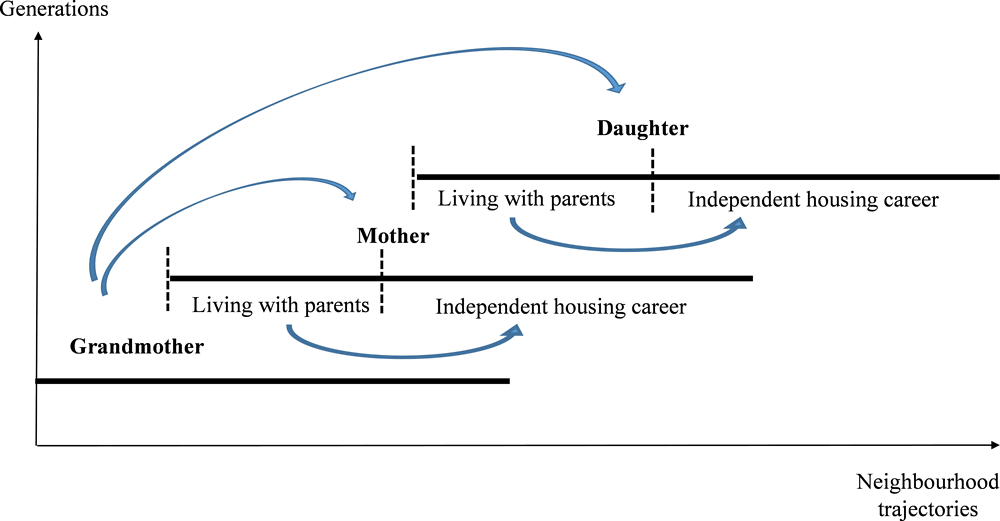

Sharkey (2013) provides compelling theoretical arguments to support the idea of multi-generational transmission of neighbourhoods, but his study is based on a theoretical model and does not actually use data for more than two generations. The first study to actually use data for three generations is by Hedman et al. (2017) who use Swedish data on the residential locations of grandmothers, their daughters and granddaughters. They found that the share of low-income people in the neighbourhoods for the youngest generation is correlated with the neighbourhood environments of their mothers and, to some extent, grandmothers. They also found an effect of geographical distance between the three generation of women; intergenerational transmission is stronger for those living in close spatial proximity. But whereas women whose mothers and grandmothers live in high-income areas benefit from staying close, women whose mothers and grandmothers live in low-income areas do better if they move further away (Hedman et al., 2017).

A recent study by Chetty et al. (2016) shows that the parental neighbourhood has important and long lasting effects on the outcomes of their children. Chetty et al. set out to re-study data from the famous Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment in the United States. This experiment was started in 1994 by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in a number of US cities. Thousands of public housing tenants were randomly assigned to three groups: an experimental group that received a voucher to move to a better neighbourhood, a group that received a voucher but was free to move where they wanted, and a group that received no voucher. The idea was that moving to a better neighbourhood would show positive effects on income and employment for adults, and on the behaviour and school results of children. The initial outcomes showed no effects of moving to a better neighbourhood (only some minor effects on mental health, see Katz et al. (2000) and several follow-up studies). But the recent study by Chetty et al. (2016) revealed that children who moved from a high poverty neighbourhood to a low poverty neighbourhood before the age of 13 earned 31% more as adults compared to those who did not move to a better neighbourhood. There was no effect for children who moved after the age of 13. The fact that Chetty et al. found these effects where previous studies found none was likely due to the fact that they had a much longer time series of data which revealed the effect of the age at which children moved to a better neighbourhood.

In conclusion, there is a strong connection between the neighbourhoods people live in, and the neighbourhood they grew up in, and there is even a relationship with the neighbourhood status between multiple generations. These intergenerational transmissions of the residential neighbourhood suggest important vicious circles of exposure to poverty between generations where children are affected by where their parents lived, and subsequently they then affect their own children later in life. These vicious circles of multi-generational transmissions of exposure to poverty neighbourhoods are illustrated Figure 5.2 (from Hedman et al., 2017).

Source: Hedman et al. (2017), “Three generations of intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood context”, IZA working paper.

Vicious circles of segregation at the urban regional level

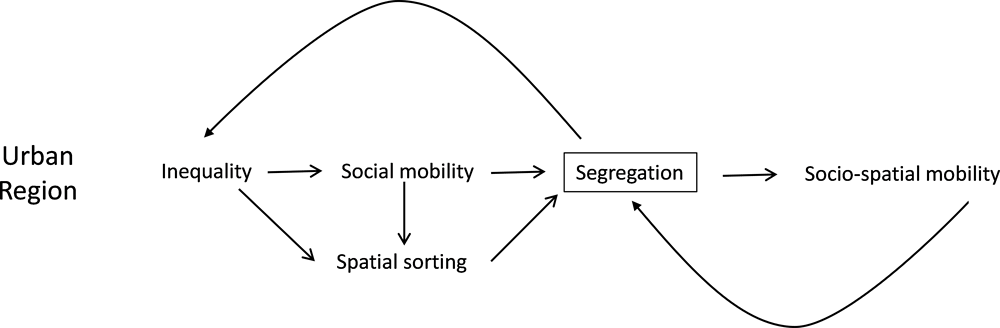

A recent study by Nieuwenhuis et al. (2017) found that “the combination of high levels of social inequalities and high levels of spatial segregation tend to lead to a vicious circle of segregation for low income groups, where it is difficult to undertake both upward social mobility and upward spatial mobility”. This research suggests that there are vicious circles of segregation at the level of urban regions. The idea is that rising inequality in cities leads to reduced social mobility because the “socio-economic distance” between the lowest and the highest income groups is large and as a consequence it is difficult to move up the social ladder. Both a high level of inequality and a lack of social mobility lead to spatial sorting of households into neighbourhoods, where the lowest income groups tend to concentrate in neighbourhoods where housing is cheap. This leads to segregation by socio-economic class.

Segregation then has a negative effect on the probability of upward socio-spatial mobility of individuals, because in segregated cities it is hard to move to a better neighbourhood. This is likely the case because of the social “distance” between poor and rich neighbourhoods, which is reflected in house price levels. In many larger European cities, and especially in inner city areas, housing prices start to get beyond the reach of middle-income households, and as a result, low-income groups, and lower middle income groups, are pushed more and more to the edges of the metropolitan region (Atkinson, 2016; Beaverstock et al., 2004; Musterd et al., 2017). David Hulchanski (2010) describes this process for the metropolitan area of Toronto where three cities have emerged: a central city for the wealthy, an in between city for the middle classes, and a suburban city for the poor. Sometimes, the emergence of such new spatial patterns of socio-economic classes is not yet visible because of ongoing processes of gentrification (see Marcinczak et al., 2013; Sykora, 2009 on the segregation paradox) or because of time lags between growing inequalities and growing socio-economic segregation (Tammaru et al., 2017; Wessel, 2016).

Nieuwenhuis et al. (2017) suggest that when segregation reduces the level of socio-spatial mobility this (re)produces segregation by petrifying the existing socio-spatial patterns in the city, which in turn is likely to affect inequality through negative neighbourhood effects of living in deprived neighbourhoods (see Figure 5.3 for an illustration of this mechanism). In their comparative study of Estonia, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom, they further explain that the stronger the role of markets, the more intense the socio-spatial mobility as both the top and the bottom socioeconomic groups start to sort into different types of neighbourhoods. Socio-spatial structures start to petrify once high levels of segregation have emerged, making it more difficult to move to a better neighbourhood. This urban spatial mechanism is related to the idea of The Great Gatsby Curve phenomenon; higher social inequalities reduce intergenerational social mobility (Krueger, 2012). Nieuwenhuis et al. (2017) argue that high levels of segregation (spatial inequality) reduces upward socio spatial mobility.

The idea of the vicious circles of segregation combines sorting mechanisms into poverty concentrations in neighbourhoods and other domains, with mechanisms of contextual effects on individual outcomes. Some of these processes run between generations. Sorting mechanisms sort low income groups in deprived neighbourhoods, which also affects exposure to poverty in schools and leisure activities. Contextual effects of these domains have an effect on individual outcomes, including income, work and health. And these outcomes influence the sorting processes of individuals and households into poverty concentration neighbourhoods. On the aggregate level these vicious circles of exposure to poverty concentrations lead to segregation. When there are high levels of inequality and segregation in an urban region, this reduces the probability of socio-economic and socio-spatial mobility, reinforcing existing spatial patterns of inequality.

Policy implications: breaking the circles

Before developing some directions for policy to reduce levels of segregation it is important to repeat that segregation by socio-economic status is not necessarily a bad thing. Many groups live together in neighbourhoods because they choose to live there with people who are similar to them. For individuals and households, in fact, segregation can have advantages for a variety of reasons as mentioned before. However, it is also clear from the literature that there are negative side effects of segregation, and especially of living in poverty concentration neighbourhoods, and particularly for children (see Hedman et al., 2015; Chetty et al., 2016). In the end, the question whether policy should fight segregation is partially a political and possibly also a moral question (Buitelaar et al., 2018).

The multi-level model of vicious circles of exposure to poverty concentrations and the resulting patterns of segregation leads to several ideas of how to break these vicious circles and how to improve cities as places of opportunities by investing in places, people, and transport, if there is a political wish to do so. Generally speaking there are three types of policy responses to segregation by socio-economic status: place-based policies, people based policies and connectivity based policies (see also van Ham et al. 2012; van Ham et al., 2016).

The place-based policies, as conceptualised here, mainly focus on the physical upgrading of deprived neighbourhoods. By demolishing low cost (social) housing and rebuilding more expensive rental and owner-occupied housing the socio-economic mix of households can be influenced. Often these policies are referred to as social mix policies (Atkinson and Kintrea, 2002; Musterd, 2002). Place-based policies require huge investments, but within a relatively short period of time a neighbourhood can be upgraded by replacing buildings and people. Such policies can only be successful if middle class households can be attracted to deprived neighbourhoods, which is not an easy task to accomplish (Lelévrier and Melic, forthcoming).

Place-based policies were popular up to the start of the financial crisis in 2008, and since then most of the larger initiatives in Europe have ended or have been stopped due to financial constraints (Zwiers et al., 2016). There have been warnings that policy should not strive to upgrade all neighbourhoods (in terms of their socio-economic status) in a city as this might lead to displacement of low income households to outside the metropolitan region. Expanding the supply of “good” neighbourhoods will only be beneficial for low income groups if in parallel also investments are made in education and social mobility for those groups. Also, every city needs low cost neighbourhoods to house new arrivals, low income workers and students. If such neighbourhoods are not available this might lead to a spatial mismatch between locations of employment and residential locations for low income workers.

There is a strong belief that social mix policies also have a positive effect on the original residents of deprived neighbourhoods. The idea is that introducing middle income households in such neighbourhoods will create positive role models and job finding networks. There is no solid evidence that this is actually the case. Recently, many European media evaluated the current situation in the Paris suburbs which were the stage of the 2005 riots. Ten years after the riots, and despite many billions in investments in these suburbs, little seems to have changed. Newspapers headlined “10 years after the riots, nothing changed” (Chrisafis, 2015) and “it goes better with the stones, but not with the people” (Giesen, 2015). Also in the Netherlands evaluation of large scale urban restructuring comes to similar conclusions: place-based investments have been successful in upgrading buildings and infrastructure, but the people have not benefitted in terms of jobs and income.

Place-based policies have the ability to reduce levels of segregation, but will only have limited effects on breaking some of the vicious circles that lead to segregation as described in this chapter. By reducing poverty concentrations in cities and by mixing socio-economic groups, people might also meet others from different socio-economic groups in different domains, such as workplaces, schools and during leisure activities. Diluting poverty concentrations might also reduce intergenerational transmissions of living in deprived neighbourhoods, and it might positively affect social mobility. However, it is unlikely that place-based policies alone will have long lasting effects on reducing levels of segregation; in the end place based policies only reduce concentrations of low income groups, without affecting the underlying mechanisms that lead to persistent poverty. To break some of the vicious circles of segregation it is needed to invest in people and opportunities.

People-based policies focus on reducing poverty and creating opportunities for people in the areas of education and employment. People-based policies require a very long term perspective as it might take a generation or longer to reduce (intergenerational) poverty. The success of people-based policies are not always visible in local communities as success might leak away. If people-based policies are successful, then children do well in school and move to higher education, and people might get jobs, more income, and hence a larger choice set on the housing market, and as a result move to a better neighbourhood. The success of such policies might therefore end up in other parts of the urban region, and the people who leave might be replaced by other low income households.

People-based policies and investing in education might break some of the vicious circles leading to segregation. Education introduces people into new networks which is likely to result in more diverse networks also in other domains of life, such as schools, workplaces and leisure. More diverse networks will affect partner choice, job matching, and education, and can have a positive effect on income and therefore affect residential choices. Obtaining a higher level of education will also help to severe intergenerational transmission of living in deprived neighbourhoods. Those who are born in a low income neighbourhood and who get a higher education degree are increasing their chances of living in a better neighbourhood as adults (De Vuijst et al., 2017).

Moving households from high poverty neighbourhoods to low poverty neighbourhoods, like in the Moving to Opportunity programme, is also a type of people-based policy. But one that also affects places as well. Moving people affects both the composition of neighbourhoods, and the spatial opportunity structure of the households who move. The research by Chetty et al. (2016) shows that in the US “moving to opportunity” can have positive effects on the incomes of children as they grow up, but only in the long run. It is not simple to translate these results to other national contexts and policies. One could argue that based on the work by Chetty et al. it is beneficial to create more socio-economically mixed neighbourhoods. But this mixing probably only works when low income households are re-located to higher income neighbourhoods, but not the other way around.

Finally, connectivity based policies are focused on physically linking deprived neighbourhoods with places of opportunity in the larger urban region. If public transport would be for free, there would be less barriers for people living in low income neighbourhoods to travel to jobs or schools in other parts of the city (Hess et al., 2018). This is especially relevant for those living in large, often high rise, housing estates which are often located at the edge of cities, and physically separated from places with job opportunities.

In conclusion, place-based policies do not necessarily reduce poverty and inequality, and people-based policies might not have the desired local effect. In the end, segregation of the poor is often a symptom of inequality and poverty. Segregation exists because there is inequality and because housing is spatially organised by socio-economic status. Reducing levels of segregation by socially mixing neighbourhoods will have some effects on inequality and social mobility, but in the end directly reducing poverty through education seems to be the most efficient way forward. A better transport accessibility can also help to break some of the vicious circles that lead to segregation by bringing people to places of opportunity. So the best strategy seems to be a mix of policies, tailored at specific neighbourhoods and cities, where neighbourhoods should not be viewed in isolation, but how they function within the larger urban housing and labour markets. Such an urban wide view should also include policies which stimulate intra-urban mobility through public transport, aiming at improving access to jobs and services.

Bibliography

Andersson, E.K., Osth, J. and Malmberg, B. (2010), “Ethnic segregation and performance inequality in the Swedish school system: A regional perspective”, Environment and Planning A, 42(11), pp. 2674–2686.

Andersson, R. and A. Kährik (2016), “Widening gaps: Segregation dynamics during two decades of

economic and institutional change in Stockholm”, in T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham and S. Musterd (eds) “Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities. East meets West”, Routledge: London.

Andersson, R. and Å. Bråmå (2018), “The Stockholm estates – a tale of the importance of initial conditions, macroeconomic dependencies, tenure and immigration”, in D.B. Hess, T. Tammaru and M. van Ham (eds), Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges, Springer: Dordrecht.

Atkinson, R. (2016), “Limited exposure: Social concealment, mobility and engagement with public space by the super-rich in London”, Environment and Planning A, 48(7), pp. 1302–1317.

Atkinson, R. and K. Kintrea (2002), “Area effects: What do they mean for British Housing and Regeneration Policy?”, European Journal of Housing Policy, 2, pp. 147–166.

Beaverstock, J.V., P. Hubbard and J.R. Short (2004), “Getting away with it? Exposing the geographies of the super-rich”, Geoforum, 35(4), pp. 401–407.

Becker, G.S. and N. Tomes (1979), “An equilibrium theory of the distribution of income and intergenerational mobility”, Journal of Political Economy, 87(6), pp. 1153–1189.

Buitelaar, E., A. Weterings and R. Ponds (2018), Cities, Economic Inequality and Justice. Reflections and Alternative Perspectives, Routledge, London.

Bygren, M. (2013), “Unpacking the causes of ethnic segregation across workplaces”, Acta Sociologica, 56(1), pp. 3–19.

Cabinet Office (2011), Opening Doors, Breaking Barriers: A Strategy for Social Mobility, London.

Chetty, R., N. Hendren and L.F. Katz (2016), “The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment”, American Economic Review, 106(4), pp. 855-902.

Chrisafis, A. (2015), Nothing's Changed: 10 Years after French Riots, Banlieues Remain in Crisis, The Guardian, 22 October 2015.

Clark, W.A.V. (1991), “Residential preferences and neighborhood racial segregation - a test of the Schelling segregation model”, Demography, 28, pp. 1–19.

Concoran, S.P. (2014), “Tiebout sorting”, in D.J. Brewer and L.O. Picus, Encyclopedia of Education Economics and Finance, Sage, pp. 787–788.

D'Addio, A.C. (2007), “Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantage: Mobility or Immobility Across Generations?”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 52, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/217730505550.

De Vuijst, E., M. van Ham and R. Kleinhans (2017), “The moderating effect of higher education on the intergenerational transmission of residing in poverty neighbourhoods”, Environment and Planning A, 49(9), pp. 2135–2154.

Dribe, M. and C. Lundh (2008), “Intermarriage and immigrant integration in Sweden”, Acta Sociologica, 51(4), pp. 329–354.

Duncan, G.J. and S.W. Raudenbush (2001), “Neighborhoods and adolescent development: How can we determine the links?”, in A. Booth and A.C. Crouter (eds), Does it Take a Village? Community Effects on Children, Adolescents, and Families, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 105–136.

Ellis, M., R. Wright and V. Parks (2007), “Geography and the immigrant division of labour”, Economic Geography, 83(3), pp. 255–281.

Ellis, M., R. Wright and V. Parks (2004), “Work together, live apart? Geographies of racial and ethnic segregation at home and at work”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 94(3), pp. 620–637.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990), The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Feijten, P.M. and M. van Ham (2009), “Neighbourhood change… reason to leave?”, Urban Studies, 46, pp. 2103–2122.

Florida, R. (2015), “Economic segregation and inequality in Europe's Cities. These are not just American problems”, Citylab, 16 November 2015.

Giesen, P. (2015), “Met de stenen gaat het goed, met de mensen een stuk minder” (The stones are doing fine, the people not so much), Volkskrant, 26 October 2015.

Glitz, A. (2014), “Ethnic segregation in Germany”, Labour Economics, 29, pp. 28–40.

Haandrikman, K. (2014), “Binational marriages in Sweden: Is there an EU effect?”, Population, Space and Place, 20(2), pp. 177–199.

Hamnett, C. (1994), “Social polarization in global cities: theory and evidence”, Urban Studies, 31, pp. 401–425.

Hedman, L., M. van Ham and T. Tammaru (2017), “Three generations of intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood context”, IZA working paper.

Hedman, L., Manley, D., Van Ham, M., and Östh, J. (2015), “Cumulative exposure to disadvantage and the intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood effects”, Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), pp. 195–215.

Hess, D.B., T. Tammaru and M. van Ham (2018), “Lessons learned from pan-European study of large housing estates: origins, trajectories of change, and future prospects”, in D.B. Hess, T. Tammaru and M. van Ham, Housing Estates in Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges. Springer.

Hofstra, B., Corten, R., van Tubergen, F., and N.B. Ellison (2017), “Sources of segregation in social networks: A novel approach using Facebook”, American Sociological Review, 82(3), pp. 625–656.

Houston, S., Wright, R., Ellis, M., Holloway, S., and M. Hudson (2005), “Places of possibility: Where mixed-race partners meet”, Progress in Human Geography, 29(6), pp. 700–717.

Hulchanski, D. (2010), “The three cities within Toronto: Income polarization among Toronto's neighbourhoods, 1970-2005”, Cities Centre, University of Toronto.

Jencks, C. and S.E. Mayer (1990), “The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighbourhood”, in L.E. Lynn and M.G.H. McGeary (eds), Inner-City Poverty in the United States, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp. 111–186.

Joassart-Marcelli, P. (2014), “Gender, social network geographies, and low-wage employment among recent Mexican immigrants in Los Angeles”, Urban Geography, 35(6), pp. 822–856.

Kahanec, M., A. Zaiceva and K. Zimmermann (2010), “Ethnic minorities in the European Union: An overview”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 5397, IZA, Bonn, http://ftp.iza.org/dp5397.pdf

Kalmijn, M. (1998), “Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends”, Annual Review of Sociology, 24, pp. 395–421.

Kamenik, K., T. Tammaru and O. Toomet (2015), “Ethnic segmentation in leisure time activities in Estonia”, Leisure Studies, 34(5), pp. 566–587.

Katz, L.F., J.R. Kling and J.B. Liebman (2000), “Moving to opportunity in Boston: Early results of a randomized mobility experiment”, NBER Working Paper, No. w7973.

Kleinhans, R. and M. van Ham (2013), “Lessons learned from the largest tenure mix operation in the world: Right to buy in the United Kingdom”, Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 15(2), pp. 101–118.

Krueger, A.B. (2012), The Rise and Consequences of Inequality in the United States, Speech given on January 12, 2012, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/krueger_cap_speech_final_remarks.pdf.

Krysan, M. and K. Crowder (2017), Cycle of Segregation. Social Processes and Residential Stratification, The Russell Sage Foundation: New York.

Kukk K., van Ham M. and Tammaru T. (2017) “EthniCity of leisure: A domains approach to

ethnic integration during free time activities”, Journal of Economic and Social Geography (TESG),

forthcoming.

Lelévrier, C. and T. Melic (forthcoming), “Housing estates in the Paris region: Impoverishment or social fragmentation?”, in D. Hess, T. Tammaru and M. van Ham, Housing Estates in Europe - Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges, Springer: London.

Malmberg, B, E.K. Andersson and Z. Bergsten (2014), “Composite geographical context and school choice attitudes in Sweden: A study based on individually defined, scalable neighborhoods”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(4), pp. 869–888.

Manley, D. and M. van Ham (2011), “Choice-based letting, ethnicity and segregation in England”, Urban Studies, 48(14), pp. 3125–3143.

Marcińczak, S., M. Gentile and M. Stępniak (2013), “Paradoxes of (post) socialist segregation: Metropolitan socio spatial divisions under socialism and after in Poland”, Urban Geography, 34(3), pp. 327–352.

Musterd, S. (2002), “Response: Mixed housing policy: A European (Dutch) perspective”, Housing Studies, 17, pp. 139-143.

Musterd, S., S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham and T. Tammaru (2017), “Socio-economic segregation in European Capital Cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich”, Urban Geography, 38(7), pp. 1062-1083.

Musterd, S. and W. Ostendorf (eds) (1998), “Urban segregation and the welfare state: Inequality and exclusion in western cities”, Routledge, London.

Nieuwenhuis, J., Tammaru, T., van Ham, M., Hedman, L., and D. Manley (2017), “Does segregation reduce socio-spatial mobility? Evidence from four European countries with different inequality and segregation contexts”, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 11123.

OECD (2015), In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264235120-en.

OECD (2010), Economic Policy Reforms 2010: Going for Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/growth-2010-en .

OECD (2008), Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264044197-en.

Perry, C.A. (1929), “The Neighborhood Unit, A scheme of arrangement for the family-life community”, Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs, Monograph 1, 7, The Russell Sage Foundation: New York.

Piketty, T. (2013), Capital in the 21st Century, Harvard University Press, Harvard.

Reardon, S.F., J.T. Yun and T. McNulty Eitle (2000), “The changing structure of school segregation: Measurement and evidence of multiracial metropolitan-area school segregation, 1989–1995”, Demography, 37(3), pp. 351–364.

Sampson, R.J. and W.J. Wilson (1995), “Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality”, in J. Hagan and R.D. Peterson (eds), Crime and Inequality, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Sassen, S. (1991), The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Schelling, T.C. (1971), “Dynamic models of segregation”, Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 1, pp. 143–186.

Schelling, T.C. (1969), “Models of segregation”, The American Economic Review, 59, pp. 488–493

Schnell, I. and B. Yoav (2001), “The sociospatial isolation of agents in everyday life spaces as an aspect of segregation”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 91(4), pp. 622–636.

Schwanen, T. and M.P. Kwan (2012), “Critical space-time geographies”, Environment and Planning A, 44(9), pp. 2043–2048.

Sharkey, P. (2013), Stuck in Place. Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress toward Racial Equality, University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London.

Sharkey, P. (2008), “The intergenerational transmission of context”, American Journal of Sociology, 113(4), pp. 931–969, https://doi.org/10.1086/522804.

Sharkey, P. and F. Elwert (2011), “The legacy of disadvantage: Multigenerational neighborhood effects on cognitive ability”, American Journal of Sociology, 116(6), p. 1934–81.

Silm, S. and R. Ahas (2014b), “The temporal variation of ethnic segregation in a city: Evidence from a mobile phone use dataset”, Social Science Research, 47, pp. 30–43.

Strömgren, M. et al. (2014), “Factors shaping workplace segregation between natives and immigrants”, Demography, 51(2), pp. 645–671.

Sýkora, L. (2009), “New socio-spatial formations: places of residential segregation and separation in Czechia”, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie [Magazine for Economic and Social Geography], 100(4), pp. 417-435.

Tammaru, T. et al. (eds) (2016), Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West. Routledge, Oxford.

Tiebout, C.M. (1956), “A pure theory of local expenditures”, Journal of Political Economy, 64, pp. 416–424.

van Kempen, R. and B. Wissink (2014), “Between places and flows: Towards a new agenda for

neighbourhood research in an age of mobility”, Geografiska Annaler: Series B Human Geography

96(2): pp. 95–108.

van Ham, M., S. Boschman and M. Vogel (2017) Incorporating Neighbourhood Choice in a Model of Neighbourhood Effects on Income. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10694.

van Ham, M. and D. Manley (2009), “Social housing allocation, choice and neighbourhood ethnic mix in England”. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 24, pp. 407–422.

van Ham, M. and T. Tammaru (2016), “New perspectives on ethnic segregation over time and space. A domains approach”, Urban Geography, 37(7), pp.953–962.

van Ham, M., Manley, D., Bailey, N., Simpson, L., and D. Maclennan (eds) (2012), Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives, Springer, Dordrecht.

van Ham, M., Hedman, L., Manley, D., Coulter, R., and J. Östh (2014), “Intergenerational transmission of neighbourhood poverty: An analysis of neighbourhood histories of individuals”, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(3), pp. 402-417, https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12040.

van Ham, M., Tammaru, T., de Vuijst, E., and M. Zwiers (2016), “Spatial segregation and socio-economic mobility in European cities”, IZA working paper, 10277.

Vartanian, T.P., P. Walker Buck and P. Gleason (2007), “Intergenerational neighborhood-type mobility: Examining differences between blacks and whites”, Housing Studies, 22(5), pp. 833–856, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030701474792.

Wessel, T. (2016), “Economic segregation in Oslo: polarisation as a contingent outcome’ in T.

Tammaru, S.Marcińczak, M. van Ham and S. Musterd, Socio- Economic Segregation in European

Capital Cities. East meets West”, Routledge: London

Zwiers, M., Bolt, G., Van Ham, M., and R. van Kempen (2016), “The global financial crisis and neighborhood decline”, Urban Geography, 37(5), pp. 664–684.