Chapter 5. Biodiversity

Hungary has one of the largest continuous grasslands, an extensive system of underground caves and among the most important wetlands for birds in Europe. It was one of the first EU member states to have its Natura 2000 network of protected areas declared complete. However, 62% of species remain in an unfavourable state. This chapter reviews pressures influencing the status and trends of biodiversity; the institutions, policy instruments and financing established to promote conservation and sustainable use; and the degree to which biodiversity considerations have been mainstreamed into sectoral policies.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

5.1. Introduction

Hungary has made several important improvements in policies related to biodiversity conservation and sustainable use since 2008, supported by European Union (EU) directives and the Convention on Biological Diversity. It was one of the first EU member states to have its Natura 2000 network of protected areas declared complete in 2011. The conservation status of most habitats and species improved between 2007 and 2012. Hungary’s second National Biodiversity Strategy is also an improvement over its first, with measurable targets and identified actions.

However, over 80% of habitats of community importance, and 62% of species, remain in an unfavourable state. Further effort is needed to reduce pressures on biodiversity from land-use change, habitat fragmentation, pollution, invasive species and climate change. Agriculture and forestry sectors remain key sources of pressures, despite their inclusion in the Biodiversity Strategy. Attention is also needed in other sectors, such as energy, transportation, tourism and industry. Greater use of economic instruments, enhanced public financing and a renewed focus on implementation will be important to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss.

5.2. Pressures, state and trends

5.2.1. Status and trends

Hungary has one large biogeographic region – the Pannonian – that consists of a large flat alluvial basin and two major rivers, the Danube and Tisza. The area was once an inland sea, surrounded by hills and mountains. The Pannonian extends into Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Serbia, Croatia and Ukraine (EC, 2009). Hungary, for the most part, is at a low elevation with 84% of the country below 200 m above sea level. Only 2% of the country is above 400 m (ICPDR, 2006).

Hungary is one of the least forested countries in Europe, with around one-sixth of the Pannonian region remaining forested. Around 40% of the forest is plantations and semi-plantations of alien species. The transition zone between the forest and the plains is an important habitat for several species, including rare plants, grasshoppers and sand lizards.

Hungary has one of the largest continuous grasslands in Europe. The plains, home to endemic plants and animals, are also important for birds and rodents. Hungary has an extensive system of underground caves that are home to bats, as well as other unique species. The caves and thermal spas are attractive tourist destinations.

The largest rivers are the Danube, Tisza and Dráva, which have many tributaries. The rivers that flow out of the surrounding mountains and upstream countries are ideal habitats for rare freshwater fish and other water-dependent species. They have been considerably altered over centuries, but still harbour large areas of natural floodplain, forests and meadows. Hungary has several lakes, with Lake Balaton being one of the largest shallow lakes in Central Europe.

There are a range of wetland types, from permanent to ephemeral (characterised by annual flooding and drying). Hungary’s wetlands are among the most important in Europe to birds, particularly waterfowl and migratory species. Hundreds of thousands come to the salt marshes and shallow alkaline lakes to rest and feed during their annual migration.

The main threats to biodiversity are over-exploitation of natural resources, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation and ecosystem degradation from pollution and development, similar to other European countries. Invasive species spread easily in disturbed and degraded habitats, and climate change further deteriorates already stressed environmental systems (GoH, 2014b).

Natural environments

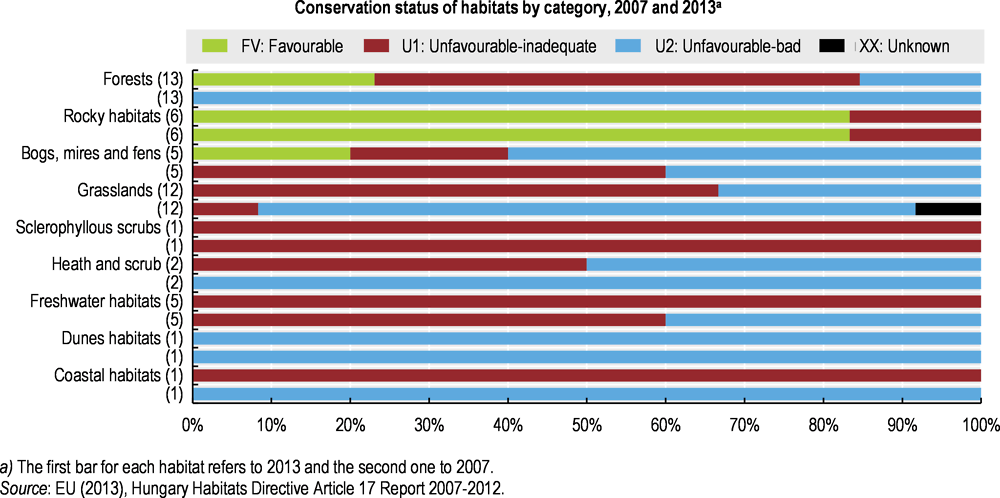

The condition of natural environments in Hungary, as with most countries in Europe, continues to raise concerns. Some 80% of Sites of Community Importance (SCIs) under the EU Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) have bad or unfavourable conservation status. Despite some improvement between 2007 and 2013, action taken to date has not been significant enough to shift priority habitats to favourable status.

Sites of community importance and special protection areas

Within Hungary’s Pannonian region are 479 SCIs and 56 Special Protection Areas under the EU Birds Directive (2009/147/EC). Together they cover about 21.4% of the total land area of the country (EC, 2018). Habitats with a favourable status increased from 11% to 19% over 2007-15, and the conservation status of more than half improved (GoH, 2014b).

The reported conservation status of forests improved slightly over the 2001-06 and the 2007-12 reporting periods, with 3 of the 13 forest habitats now in favourable condition. However, this is mainly due to a change in survey methodology and additional data rather than actual improvement (GoH, 2014b). The change in the status of wetlands was mixed: one habitat moved to favourable status, while another moved to unfavourable-bad status. The situation for grasslands improved somewhat, with the number of habitats in unfavourable-bad status decreasing from ten to four. There are no longer any freshwater habitats with unfavourable-bad status (Figure 5.1).

Water-dependent and wetland ecosystems

Around 56% of the 1 026 natural and artificial water bodies have been classified at risk due to pollution from households not connected to the sewage system, sewage treatment plants and agriculture. None of the 108 groundwater bodies is considered at risk, but 46 sites are identified as “possibly at risk” due to nitrate pollution (GoH, 2014b). While 8% of rivers, 18% of lakes and 68% of groundwater bodies are in excellent condition, 60% to 70% of surface waters are eutrophic with excess nutrients from agriculture and municipal wastewater (GoH, 2014b).

As 95% of Hungary’s surface waters originate from other countries, external factors can significantly influence their ecological status (GoH, 2015). International co-operation is therefore particularly important to improving the status of rivers. River regulation and flood management within Hungary have also significantly impacted water flow, water levels and alluvium conditions of water systems, with dams closing off river branches and backwaters (GoH, 2015).

Hungary has 29 designated wetlands of international importance under the Ramsar Convention on wetlands, covering 243 000 ha. Reduced water levels are a key issue for wetlands, with pressures from both human activities and climate change (GoH, 2015).

Flora and fauna

More than 53 000 species are present in Hungary, of which 82% are animals (CBD, 2017). Hungary’s Pannonian region covers only 3% of EU territory, but the region harbours 17% of the species listed in the Habitats Directive and 36% of species listed in the Birds Directive (GoH, 2014b). The high number reflects the level of biodiversity, endemism and fragility of species in the region (EC, 2009).

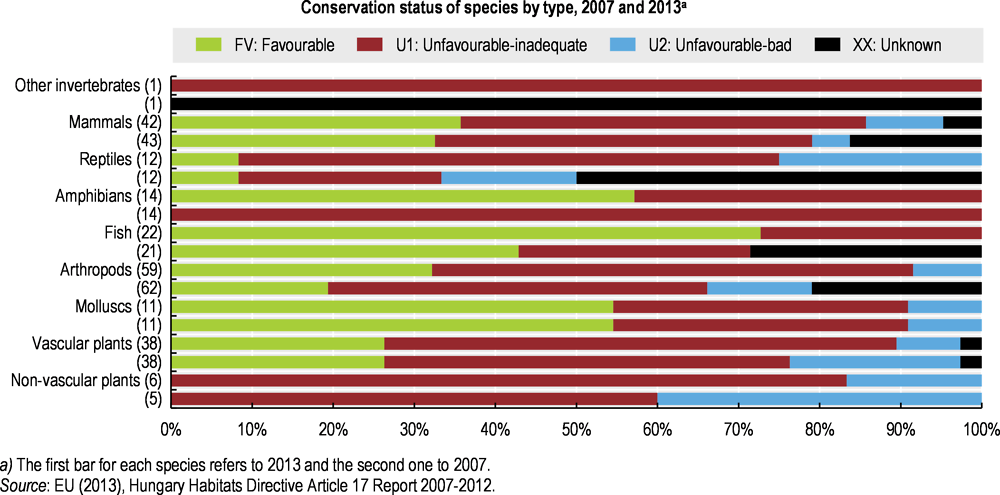

Around 62% of species under the Habitats Directive are in an unfavourable- inadequate or unfavourable-bad conservation status. The conservation status of 5% of species has improved since 2007, while the status of 4% has worsened (Figure 5.2).

Birds

Many species that are endangered in the rest of Europe still breed in large numbers in the Pannonian region. Every spring and autumn, hundreds of thousands of birds come to rest and feed in the region during their annual migration.

Populations of farmland bird and wild duck species have declined since 2005, but forest birds have been relatively more stable (GoH, 2015). Reporting for 2008-12 under Article 12 of the EU Birds Directive analysed the population trends of birds. It found that 19% of breeding birds and 15% of wintering birds declined in population over 24 years (Figure 5.3). The long-term status of 52% of breeding birds is unknown. The focus to date has largely been on common birds and threatened species, leaving those in-between with limited monitoring. A new government initiative aims to map breeding birds and estimate the populations of medium-rare species.

5.2.2. Pressures on biodiversity

Land-use change and fragmentation

Over time, land use has changed considerably in Hungary. At the end of the 19th century, large-scale canalisation and land reclamation drained floodplains to make way for crop production. During the period, the Tisza River was shortened by 134 km. A network of dykes and drainage channels was constructed across the plains, transforming the vegetation of the region. Over the last 150 years, around 93% of Hungary’s floodplain was lost and over 60% of land in the Pannonian biogeographical region was converted to arable land (EC, 2009). Natural system modifications, such as water abstractions, dredging and fire suppression, continue to be key pressures on biodiversity.

Net habitat loss has increased since 2004 (Mihok et al., 2017). Though many arable lands and other agricultural areas are being abandoned, agricultural production has increased and intensified. Agriculture remains one of the most significant pressures on biodiversity (Section 5.6.1). Forest area1 has increased from 21% to 23% as a share of the total terrestrial area over 2000-14, but this is due primarily to plantations of non-native tree species (Section 5.6.3). Indigenous trees represent around 57% of the forested area (CBD, 2017).

Landscape fragmentation is a leading cause of the decrease in wildlife populations in Europe. Fragmentation prevents access to resources, facilitates the spread of invasive species, reduces habitat area and quality, and isolates species into smaller and more vulnerable fractions (EEA, 2011). In Hungary, fragmentation from roads, railways and urban expansion is greatest in and around the Budapest Metropolitan Area (which comprises roughly one-third of Hungary’s population). However, fragmentation is also increasing across the country. For example, between 1990 and 2011, the country’s road network grew by over 2 600 km. By 2027, it is expected to grow by an additional 2 600 km (Bata and Mezosi, 2013).

Invasive species

Currently, 13% of natural and near-natural habitats are heavily infested with invasive species (GoH, 2014b). There are 41 plant and 35 animal species that are considered a threat to indigenous flora and fauna. Of these, 17 plant species and 3 animal species represent a high ecological risk (GoH, 2015).

Invasive species can impact the reproduction and germination of indigenous species, carry diseases and push out local fauna (GoH, 2015). Forest plantations of species such as black locust (false acacia) can spread and become a problematic invasive species in protected areas despite limitations on planting (Section 5.6.3).

Pollution

Pollution, which can have a significant impact on biodiversity, is a major cause of habitat degradation for aquatic species. As noted in Section 5.2.1, 60% to 70% of surface waters in Hungary are eutrophic. The main contributors to eutrophication are nitrogen, phosphorus and ammonia pollution. These can come from air emissions, run-off from agricultural activities or municipal wastewater. Nitrogen oxide emissions dropped 27% between 2005 and 2015. However, emissions from agriculture increased by more than 30% over the period. Ammonia emissions, also mainly from agriculture, dropped during the economic slowdown, but almost returned to 2005 levels by 2015. This will make it difficult for Hungary to meet its EU target for ammonia (-34% compared to 2005 levels over 2020-29).

Climate change

Climate change will increase the vulnerability of species in Hungary. Increased evaporation, for example, is expected to reduce the surface area of smaller lakes. In addition, certain wetland habitats and shallow oxbow rivers may become dry. This will decrease the habitat of waterfowl and nesting sites for birds and may cause other species to migrate from dry areas. The risk of higher saline content and eutrophication will also increase (Climate Change Post, 2017). If water consumption, particularly from agriculture, remains unchanged, certain regions could face water shortages that will further impact biodiversity.

5.3. Strategic and institutional framework

Hungary has a strong legislative framework to support biodiversity, with legislation covering nature conservation, forests, fisheries and other areas. The country’s biodiversity policy is largely determined by EU legislation, particularly the Birds and Habitats Directives. As noted in Chapter 2. , Hungary has significantly transformed its governance system relating to the environment and biodiversity over the past decade. A full assessment of the implications for biodiversity has not been completed. However, anecdotal evidence suggests negative impacts have accompanied the integration benefits. Greater effort is needed to clarify policy direction, co-ordinate across relevant organisations, monitor and evaluate results, and increase financial and human resource capacity in district offices.

5.3.1. Strategic framework

In 2015, the Hungarian government adopted its second National Biodiversity Strategy (2015-20). The strategy is linked to the Aichi targets under the Convention on Biological Diversity. It has 6 strategic areas, 20 objectives, 69 measurable targets and 168 related actions, as well as a variety of indicators to measure progress (Table 5.1). Implementation will rely on the European Union as well as on Hungarian funding, although many actions do not have cost estimates. The strategy requires an interim evaluation in 2017 and a retroactive evaluation in 2021 (GoH, 2015).

The strategy, relatively comprehensive and ambitious, improves upon the previous version, which did not have measurable targets. However, the strategy could have stronger linkages to sectors beyond agriculture, forestry and fisheries. The strategy has no influence on other ministries beyond the Ministry of Agriculture (which is now responsible for biodiversity, agriculture, forestry and fisheries). The interim evaluation of the National Biodiversity Strategy in 2018 is expected to indicate progress in implementation.

Biodiversity commitments are made in several other strategies and plans, though with insufficient cross-references or connections to the Biodiversity Strategy. The National Nature Conservation Master Plan 2015-20, part of the National Environmental Programme approved by Parliament, sets the main policy objectives and priorities for the relationship between the economy and the environment (GoH, 2014b). Biodiversity has also been integrated into the National Sustainable Development Framework Strategy 2012-24, the National Rural Development Strategy 2012-20, the National Action Plan for the Development of Ecological Farming and the Fourth National Environmental Programme 2014-20. The National Environmental Programme 2015-20 includes the protection of natural values and resources and their sustainable use as one of three strategic objectives. It also makes linkages to biodiversity in several areas, including agriculture, silviculture, mineral resources management and traffic. There has also been some integration of biodiversity aspects into the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, the National Water Strategy and the National Forest Programme 2006-15 (GoH, 2014b). The partnership agreement between the European Commission and Hungary for 2014-20 includes several operational programmes (OPs). Biodiversity considerations are well integrated into some, such as the Environmental and Energy Efficiency OP, but less so into others, such as the Integrated Transport OP that primarily aims to increase road and rail transport (EC, 2014c).

International commitments

Hungary ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1994. Since then, it has produced five national reports and two national strategies and action plans supporting the convention. Hungary ratified the Nagoya Protocol on access to genetic resources and a fair and equitable sharing of benefits from their use in April 2014, with entry into force in October 2014 (GoH, 2014b).

All but one native species listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) are strictly protected in Hungary. The country represents the European Union at the CITES Standing Committee. The National Park Directorates have strong co-operative relationships, having 43 projects with cross-border countries and 12 with other countries. Hungary’s biodiversity policies are influenced by regional conventions such as the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats.

5.3.2. Institutional framework

Government

Environmental policy is largely the responsibility of the central government and its territorial institutions. These bodies share operational and enforcement responsibilities with regional and local authorities. Hungary is one of the only EU member states without a dedicated environment ministry (Chapter 2. ). In 2010, biodiversity policy, along with other environmental policy responsibilities, was transferred to the Ministry of Rural Development (renamed the Ministry of Agriculture in 2014). In 2012, water management was transferred to the Ministry of Interior.

The Department for Nature Conservation and the Department of National Parks and Landscape Protection share responsibility for biodiversity policy development and programme management. These departments fall under the Ministry of Agriculture, which has a total staff of 56. There are also 10 National Park Directorates, with 1 100 employees. The regional nature conservation authorities have 86 employees spread across 19 counties. An additional 66 employees work on invasive alien species, which reflects the challenge in Hungary. Environment and nature regulatory enforcement was recently transferred from the 10 regional nature conservation authorities to the 19 county government offices and 197 district offices as part of the State Territorial Administration Reform (Chapter 2. ). The transfer has been a challenge for biodiversity conservation, since the 83 staff from the authorities, with different specialties, are now dispersed across 19 offices, with only 3 additional staff. Training has begun, but it will take time, additional resources and continued effort to ensure that the transfer improves biodiversity outcomes.

Civil society

There are 50 to 60 non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Hungary working on nature conservation. The NGOs receive some funding from the Ministry of Agriculture’s Green Fund, which has been reduced by more than 30% since 2011. Some NGOs participate in several committees. These include the Hungarian Man and Biosphere Committee (2010), which controls 6 biosphere reserves, and the Hungarian Ramsar National Committee, which oversees 29 Ramsar wetland sites. NGOs have also been recipients of HUF 1.38 billion (EUR 4.4 million) in financing from the EU LIFE Capacity Building in Hungary project that supports nature conservation. In addition to reduced government funding to NGOs, recent legislative changes increased financial reporting requirements for NGOs receiving more than EUR 24 000 from foreign donors (including the European Union). This may make it more difficult for conservation NGOs to remain viable (Thorpe, 2017).

Two NGOs in particular have contributed significantly to nature conservation in Hungary. WWF Hungary has operated for 25 years, working with national parks conservation authorities, other NGOs, educational institutions, business representatives and the local population to promote nature conservation. Birdlife Hungary, founded in 1974, advocates for nature conservation of birds and their habitats, works to raise awareness and undertakes monitoring and research in partnership with the government. The NGOs have expressed strong concerns about the impact of government changes, such as the merger of the Environment Ministry with the Ministry of Agriculture, on nature conservation. They did, however, successfully argue against a bill proposing to transfer land management rights of National Park Directorates to a centralised National Land Fund (Benedetti, 2015; WWF et al., 2016, 2015).

Private biodiversity stakeholders

Most private action has been stimulated by government subsidies. However, in 2008, the electricity sector came together with Birdlife Hungary and state nature conservation bodies to sign the Accessible Sky Agreement, aimed at minimising bird mortality along power lines by 2020. The agreement is supported by 2008 legislation requiring power lines to be constructed in a bird-friendly manner. A study prioritised power lines for retrofit, and a new EU LIFE+ project aims to bury priority power lines in the area of the largest great bustard population in Hungary. However, progress has recently slowed.

Scientific and technical expertise

Hungary does not have one single programme to support research and development (R&D) related to biodiversity. There are instead general calls for research, where biodiversity-related research is eligible to apply. Some major projects related to biodiversity have been funded, including research for mitigating the negative effect of climate change, land-use change and biological invasion.

Hungary has several initiatives related to conservation of genetic resources, including the Centre for Plant Diversity and the Research Centre for Farm Animal Gene Conservation. The centres maintain and co-ordinate protection of conventional agricultural plant varieties and endangered old Hungarian farm animal species in gene banks.

Environmental impact assessment and strategic environmental assessment

In Hungary, environmental impact assessment (EIA) is required for activities that are likely to have adverse effects on biodiversity. In 2005, the scope of EIA was extended to include not only the impact of individual projects, but also their cumulative and global effects. The EU Habitats Directive also requires the assessment of any plan or investment that may have a significant impact on any Natura 2000 territory. The analysis is required to cover impacts on soil, air, water, wildlife and the built environment (Chapter 2. ). A lack of localised data on species and ecosystems, particularly outside of protected areas, can limit the extent to which biodiversity is considered in some assessments (Section 5.4.1).

Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is required for regional plans, settlement structure plans, the National Development Plan, operative programmes, road network development plans, and other local and sectoral plans or programmes. SEA considers environmental effects of implementing the plan or programme, including on biodiversity and Natura 2000 areas.

5.4. Information systems

The environmental awareness of Hungarians increased from 41% to 55% over 2007-11. However, only 10% of respondents were familiar with the term “biodiversity” in 2011. This highlights the need for further education and information dissemination relating to biodiversity (GoH, 2014b). As part of its response, the government established the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in 2012. The platform aims to promote adequate use of scientific information and strengthen the relationship between science and political decision making (GoH, 2015). Monitoring systems and ecosystem indicators have also improved. However, detailed and local information needed to inform decisions on projects or policies remains inadequate, particularly outside of protected areas.

In 2010, the Ministry of Agriculture created a brand of National Park Products. It identifies products made in protected natural areas based on local traditions consistent with the principles of sustainable development. Currently, 158 producers use the label for more than 618 products, including syrups, fruit juices, wines, salami, sausages, jams, honey, cheese and smoked trout. The programme helps raise environmental awareness and strengthen co-operation between nature conservation, rural development and economic growth.

Source: NPT (2017).

5.4.1. National Biodiversity Monitoring System

A National Biodiversity Monitoring System (NBMS), introduced in 1998, assesses the status of, and long-term changes in, species and habitats. Monitoring takes place at the national and local levels. The number of locations and species populations examined has increased steadily since the system was introduced.

The data generated from the NBMS are entered into the Nature Conservation Information System. This is a geographic information system (GIS) linking biological protection, biodiversity monitoring, geology nature preservation, nature conservation and asset management. Hungary launched a voluntary online nature observation programme in 2009 to collect data on animal and plant species from the general public (GoH, 2015).

The EU Birds and Habitats Directives require expansion of the NBMS to monitor species and habitats of community importance. The nature conservation status of only 2% of the 208 species of community importance remained unknown in 2013, down from 17% in 2007, demonstrating improvement, though work continues to increase the quality of data. None of the 46 habitat types was classified in the unknown category (GoH, 2015).

Ecological data at the local level are limited outside of protected areas. EIA and SEA often require local GIS-based data, as well as habitat and soil maps. Historically, the cost of obtaining the data needed to adequately analyse biodiversity impacts was prohibitive. However, the government is working to improve the availability of, and access to, relevant data through national ecosystem mapping and an open data policy.

5.4.2. Ecosystem service information

Hungary’s planned mapping and assessment of ecosystems and their services in 2016-20 will help address data gaps and improve biodiversity knowledge. Specifically, it will include improved data collection, monitoring and research related to biodiversity within and outside protected areas. The project will produce a map of ecosystems and a survey of their status, a map and prioritised list of ecosystem services, and guidance on the protection of natural and close-to-natural ecosystems and their services. This information will be key for policy makers and could form the foundation of future work to determine monetary values for ecosystem services. The use of ecosystem service assessments is an important communication lever to justify public investment in biodiversity, including in protected areas. For example, initial estimates of the value of forest provisioning services alone are close to HUF 1 000 billion (approximately EUR 3.3 billion) (GoH, 2014b).

5.5. Instruments for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use

Hungary has a number of instruments to ensure biodiversity conservation and sustainable use. Over and above regulatory approaches, which are generally preferred for protecting habitats and species of importance, economic instruments can finance programmes in favour of biodiversity. They can also contribute to the integration of biodiversity considerations into economic sectors (Section 5.6).

5.5.1. Protecting ecosystems, habitats and species

Protected areas

Hungary has already surpassed the Aichi target to protect at least 17% of land and water under its jurisdiction by 2020. It was also one of the first EU member states to have its Natura 2000 network of protected areas declared complete in 2011. However, work remains to complete management plans for all the protected areas, improve coverage of species types and address the shortage of park rangers.

The total size of territory under protection in Hungary increased from 9.4% under national legislation to 22.2% when Hungary was brought into the EU Natura 2000 network in 2004 (CBD, 2017). Nature conservation sites of local importance cover almost 0.5% of the country (GoH, 2014b).

Hungary’s protected areas network is considered sufficient for all habitats and species of European importance. It consists primarily of national parks and landscape protected areas (Figure 5.5). The proportion of grasslands under protection is more than double the EU average (GoH, 2014b). Over half of national protected areas are forest, with 22% of forests located in a protected area. Over 70% of inland waters belong to the Natura 2000 network (GoH, 2014b). The area of protection has remained relatively stable since 2008, with minor extensions and adjustments reflecting more accurate delineation (Figure 5.5). Protection is now measured at 22.6% of the territory. In October 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled that measures that result in deterioration of the environment are contrary to the Fundamental Law, specifically referencing the sale of Natura 2000 land to farmers and the use of associated revenue to reduce state debt (CCH, 2017).

Work remains to improve management of protected areas. The number of areas with management plans has increased, growing from 45 of 211 (21%) in 2008 to 180 of 307 (59%) in 2016 (GoH, 2014b). However, only 8% to 10% of protected areas had binding management plans as of 2016. There are also no national data available on the extent of management plans for local protected areas, as this is left to local governments.

The coverage of the Natura 2000 sites is very good for habitat types. Almost three-quarters of assessed sites have 75% to 100% coverage, and the remaining quarter has 25% to 74% coverage (GoH, 2014a). For species types, the coverage is less complete. Slightly more than half of assessed species have 75% to 100% coverage; around 40% have 25% to 74% coverage; and 5% have 0% to 24% coverage (GoH, 2014a).

There is a shortage of park rangers. One ranger covers an average of 372 km2, including 80 km2 of Natura 2000 or nationally protected areas. More than 700 volunteer civil nature guards assist in patrolling and fill some of the capacity gap, but do not have the same training as rangers.

Species action plans

The EU LIFE programme has funded projects that target conservation of individual species, including the great bustard, the Hungarian meadow viper, the Saker falcon and the red-footed falcon. Most species conservation efforts focus on protected areas. However, there have been some initiatives elsewhere, such as projects to make power lines more bird-friendly, subsidies for good environmental practices in agriculture, and restrictions on farming and forestry in habitats of strictly protected species. Habitat reconstruction and habitat development has been carried out on 5% of Natura 2000 areas (GoH, 2014b).

Invasive species management

National legislation prohibits the unauthorised introduction of new invasive organisms and requires that agricultural lands be maintained free of weeds. Activities to eradicate or manage invasive species have taken place in most protected areas to varying degrees, depending on the level of concern and financing available. However, outside of protected areas, there has been limited effort. Hungary is participating in a European-wide awareness-raising initiative – NatureWatch – that allows citizens to identify and report invasive alien species online (GoH, 2014b).

5.5.2. Economic instruments

Economic instruments, such as taxes or subsidies that discourage activities harmful to biodiversity or encourage beneficial activities, can play an important role in biodiversity conservation and sustainable use policy. They can help correct market failures that lead to overexploitation of natural resources, degradation of ecosystems and impacts on species and their habitats. Hungary uses economic instruments in several areas, but has relied mainly on subsidies for the agriculture sectors where key pressures on biodiversity remain. There is scope to expand the use of taxes and charges in areas such as ammonia emissions and the cultivation of flooded land. In addition, Hungary could expand subsidy payments for ecosystem services to areas such as control of invasive species, modernisation of irrigation systems and protection of species or habitat outside of protected areas.

Taxes, fees and charges

Hungary has a number of taxes, fees and charges linked to biodiversity. Investors pay non-refundable application fees for licences that give them the right to use natural resources or protected species. No licences have been issued to commercial fishers since January 2016. However, recreational fishers and anglers must pay for tickets from the fishing rights holder. The charge depends on the water body and frequency of use (daily, weekly, monthly, annually). Revenue from the tickets is used to fund fisheries-related activities of state interest.

Protected areas have several fees associated with them. These include fees at visitor centres and interpretation sites. Protected areas are, however, for the most part free to visit.

Hungary’s water resource fee is calculated for each user based on the volume and purpose of water use, as well as the type and quality of the water resource. A new pressure multiplier was introduced to the fee at the beginning of 2017 to reflect the EU Water Framework Directive. The multiplier increases the fee for groundwater bodies that have an “at risk” or “bad” quantitative status.

Hungary also uses a “land protection contribution” charge linked to a permit to use agricultural land for another purpose, such as conversion to urban use. The charge depends on whether the land-use change is temporary or permanent, as well as on the agricultural quality and size of the land. Exemptions to the payment are provided for some public utilities, state and local rental housing, irrigation, soil and conservation facilities, as well as social, health and sports facilities. Over 2013-16, the charge raised around HUF 1.5 to HUF 2.2 billion (EUR 4.9 to EUR 7.1 million) of general budget revenue.

A soil conservation charge is also levied on anyone who removes humic (containing organic matter) topsoil. Revenue from the charge helps finance regulatory tasks related to soil conservation on agricultural land. A forest protection charge also applies to the use of forest, unless the forest is replaced.

Payments for ecosystem services

EU agricultural and rural development subsidies encourage biodiversity-friendly practices (Section 5.6.1). Other subsidy programmes encourage actions beneficial to biodiversity, such as payments for afforestation and forest rehabilitation (Section 5.6.3) and payments for environmentally-friendly aquaculture practices (Section 5.6.2). In some cases, nature conservation authorities may pay compensation to a proprietor for damage by a protected animal species or by management restriction or prohibition. The majority of these types of payments have been to farmers, and some forest owners. The most relevant species for the payment are birds such as the corncrake, black stork, white-tailed eagle and collared pratincole. Further use of payment for ecosystem service schemes could be considered to alleviate pressures on biodiversity, such as improving control of invasive species, modernising irrigation systems and protection of species or habitat outside of protected areas.

5.5.3. Public financial support

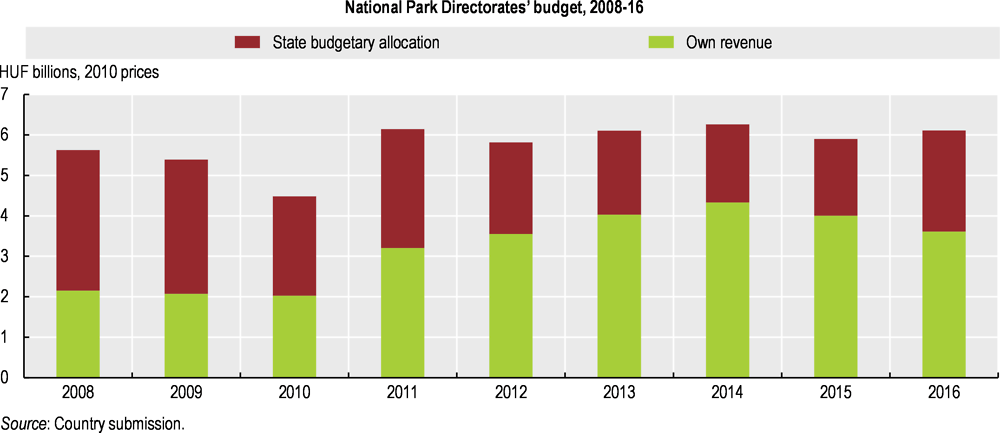

The budget for the National Park Directorates has increased since 2008, largely as a result of substantial revenues raised by the directorates themselves. Nature conservation funding from the European Union has declined, but Hungary could still significantly benefit from the EU LIFE programme that co-finances specific projects.

The Ministry of Agriculture does not allocate an independent budget to the Department for Nature Conservation or the Department of National Parks and Landscape Protection. Their funding is included in the overall ministry budget, which may risk a loss of resources if priorities shift. Capital, county and district government offices also receive a general budget from the Annual Budget Act, with no specified allocation for nature conservation. It is therefore difficult to assess trends in funding for nature conservation over time. National Park Directorates do, however, receive a separate budget.

The budget for National Park Directorates has increased since 2008 (Figure 5.6), with a significant portion (almost 60%) sourced from their own revenues (HUF 4.1 billion in 2016). The directorates generate revenue from the use of protected land for environmentally-friendly farming, including crops and livestock, as well as ecotourism. The lands are also eligible for EU agricultural grants. Revenue declined between 2014 and 2016 due to a change in rules under the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and public funding was increased to fill the gap. Environmental groups have, however, expressed concern that the directorates’ dependence on own-source revenue is distorting decision making, favouring revenue-generating activities over nature conservation (WWF Hungary et al., 2015).

Between 2007 and 2013, HUF 45.3 billion (EUR 147 million) was provided for direct nature conservation investments under the Environment and Energy Operational Programme and the Central Hungary Operational Programme. The funds supported 214 projects targeting 130 000 ha of land within protected areas, with National Park Directorates receiving 66% of the funding. Most projects related to improving natural habitats or nature management infrastructure. In 2014-20, HUF 37.8 billion ha under the Environment and Energy Efficiency Operational Programme and the Central Hungary Operational Programme is available for direct nature investments. These include ecological restoration projects and investments in nature management infrastructure on at least 100 000 ha of protected areas and/or Natura 2000 sites. Additional funding of HUF 4.5 billion will be provided for ecotourism investments in National Park Directorates (down from HUF 7.3 billion over 2007-13). The drop in EU funding related to nature conservation results from shifting EU priorities, such as the focus on urban green areas and ecotourism in World Heritage Sites. In addition, numerous nature educational facilities were improved in 2007-13, reducing the need for new financing.

The nature and biodiversity component of the EU LIFE programme co-finances best practice and demonstration projects that contribute to implementation of the Birds and Habitats Directives and the Natura 2000 network. This is an important source of financing for Hungary’s National Park Directorates. Over 2008-16, the programme financed 19 projects in Hungary, providing more than EUR 1 million towards total costs of EUR 2.1 million. However, changes in budgeting in 2012 may have reduced capacity to apply for EU funding (WWF Hungary et al., 2015).

5.6. Mainstreaming biodiversity into economic sectors

Hungary has done relatively well in mainstreaming biodiversity into the strategic plans for agriculture, forestry and fisheries, which are included in the National Biodiversity Strategy and managed under the same ministry. However, it has been less successful at implementation and in integrating biodiversity considerations into other sectoral strategies, notably energy, industry, transportation and tourism. Spatial planning and EIA appear to be the main policy tools to address biodiversity impacts in these sectors.

Further work remains to reduce pesticide use, ammonia emissions and cultivation of flooded land, and to modernise irrigation systems and increase organic farming. Forest area has increased, but the plantations of non-native species are relatively large. Hungary is also one of the largest bioethanol producers in the European Union, making it important to monitor the land-use and biodiversity impacts of growing production. Policies that support biofuel production can encourage agricultural expansion, and therefore risk increased pressures on biodiversity over time.

5.6.1. Agriculture

Hungary’s fertile plains, climate and water availability support a strong agricultural sector. Agricultural land, which covers 59% of total land area, consists of 48% arable land, 9% grassland and 2% gardens, vineyards and orchards. Rural residents, who represent 46% of the population, depend significantly on agriculture for employment, and the agriculture industry accounts for 15% of Hungary’s gross domestic product (GDP). Farm sizes are smaller in Hungary than elsewhere in the European Union, with 87% of farms having less than 5 ha (EC, 2014a).

The key pressures on biodiversity in agriculture areas are from excessive use of natural resources, pesticide use, invasive species, a lack of modern technology and modern practices, and climate change (GoH, 2015). Hungary experiences both drought and flooding, yet its outdated irrigation system only covers 2.4% of the agricultural area (EC, 2014a). Legislation and flood management programmes continue to support cultivation of regularly flooded areas, threatening wetlands (CBD, 2017). The abandonment of grazing also presents a threat to grasslands (GoH, 2015).

Pesticide use

Pesticide sales in Hungary increased significantly between 2011 and 2015, and the intensity of their use per hectare is among the ten highest in European countries of the OECD (Figure 5.7). Hungary’s 2012 National Plant Protection Plan describes several actions to limit pesticide use. These include limits on pesticide purchases; training and information to reduce exposure; pilot projects to showcase good practice; encouragement of organic farming; protection of vulnerable ecosystems; control of hazardous waste; and inspection of equipment. However, weather extremes, new invasive pests, EU bans of certain substances and a lack of manual labour have increased overall use of pesticides.

Hungary is also one of the few EU member countries that still allows aerial spraying of pesticides, under very strict conditions (EC, 2017). Inadequate use of fertilisers is also a risk due to accumulation of heavy metals in the soil. Heavy metals can be integrated into the food chain, acidify the soil and contaminate groundwater (GoH, 2015). The Hungarian government does not support a tax on pesticides, as is used in France, Denmark, Norway and Sweden. It is concerned that a tax would increase the purchase of black market pesticides from other countries. However, additional measures may be required to address pesticide use that is negatively impacting ecosystems and species if the Plant Protection Plan does not produce measurable improvement.

Organic farming

Organic farming could benefit biodiversity as it can reduce use of chemical or synthetic fertilisers or pesticides and limit livestock density (although additional use of manure may sometimes increase ammonia emissions and nitrate leaching). It is also an economic opportunity for Hungary, given market conditions in Europe, existing restrictions on genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and favourable climate and soil conditions for organic farming. The country has a relatively small share of organic farming compared to other OECD member countries, though the total area increased from 2.4% to 3.5% over 2010-16 (Figure 5.8). Roughly 80% to 85% of certified organic products made in Hungary are exported without processing.

In 2014, Hungary developed an Action Plan for Developing Organic Farming that focuses on incremental improvements to regulations, training, research and product promotion. The plan is in accordance with the European Action Plan for Organic Food and Farming. It aims to at least double the organic farming area (reaching 300 000 ha) and controlled livestock by 2020. It also seeks to increase organic bee colonies, local processing of animal products and use of organic products in public catering. The National Biodiversity Strategy also proposes subsidies for experimental ecological farming (GoH, 2015).

Organic farms are eligible for funding designated for sustainable agricultural practices under the EU CAP. They are also eligible for Rural Development Programme funding in 2014-20, which supports both conversion and maintenance. Achieving 350 000 ha of organic farming by 2020 will be challenging, given that the area was only 129 735 ha in 2015 – a level virtually unchanged since 2012 (FiBL and iFOAM, 2017). In 2016, the area of organic farms receiving support was 133 679 ha. At this rate, the total area would need to grow by over 35 000 ha per year to reach the 2020 target. Hungary has, however, achieved GMO-free agriculture through its 2006 strategy (MRD, 2017).

Ammonia emissions

Agriculture accounts for over 90% of ammonia (NH3) emissions in Hungary (EMEP, 2017). Ammonia contributes to acid deposition and eutrophication, affecting soil and water quality (Section 5.2.1). The EU directive on atmospheric pollutants (2016/2284/EU) sets a target for Hungary to reduce ammonia emissions by 10% below 2005 levels over 2020-29 and by 32% thereafter. In 2015, Hungary’s ammonia emissions were 1% below 2005 levels. However, this is higher than 2010 levels, which had reached 10% below 2005 (EMEP, 2017). Further effort, through increased regulation or taxation, is needed to reduce agricultural sources of ammonia emissions, to both meet the EU directive and address eutrophication in Hungary’s lakes.

Agriculture subsidies

Hungary has not assessed environmentally harmful subsidies comprehensively. However, it has committed to review support policies detrimental to the preservation of agricultural biodiversity and amend them as necessary in its National Biodiversity Strategy. The National Rural Development Strategy 2012-20 also sets a target to revise harmful subsidies. In 2015, agricultural support was reformed in line with the EU CAP and environment-related support was added. The revised programme aims to maintain permanent grasslands, promote crop diversification and encourage designation of agriculture that is environmentally friendly. There are indications, however, that some subsidies harmful to biodiversity remain, such as those related to flood protection that encourage the drainage of regularly flooded land important to birds and other species.

In 2012, Hungarian farmers received HUF 650 billion (EUR 2.1 billion) in agricultural-rural development support. Of this amount, 14% was related to environmental measures that contribute directly or indirectly to biodiversity. Since the reform of the EU CAP in 1999, agro-environmental measures have been mandatory for rural development programmes of member states. In Hungary, 20% of the agricultural area is now part of the agri-environmental programme, of which 48% is dedicated to the preservation of agricultural biodiversity (GoH, 2015).

The agri-environmental programme has a focus on high nature value areas (HNVAs). These encourage the preservation and maintenance of nature-friendly farming, habitat protection, the continuation of biodiversity and protection of the landscape and cultural values. The total area of designated HNVAs in Hungary is 1.2 million ha, with 900 000 ha eligible for support. In 2011, farmers requested payments for more than 94 000 ha of arable land and more than 100 000 ha of grassland (GoH, 2015). As noted in Section 5.5.3, National Park Directorates also receive EU subsidies for environmentally friendly farming in protected areas. It will be important to gradually expand the promotion of environmentally friendly farming practices through both information provision and subsidy programmes to all agricultural areas until sustainable practices are widespread.

As mentioned in Section 5.5.2, payments are available for Natura 2000 grasslands to compensate farmers for restrictions put in place. Farmers may apply for an annual payment of EUR 69 per hectare. The amount of compensated area has grown from 75 000 ha to 319 000 ha over the past eight years. Farmers are also eligible for public support for investments that have a positive environmental impact but do not generate a financial return (EUR 6.4 million was received between 2011 and 2015, and EUR 19 million more is available for 2014-20). In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture launched the Productive Village Programme to revitalise former backyard orchards and vineyards to both increase rural incomes and preserve the genes of local fruits. Hungary could consider a broader payment for ecosystem services programme for sustainable farming practices outside of protected areas. This might be financed through taxes on negative inputs to, or outputs from, agriculture such as pesticide use and ammonia emissions.

5.6.2. Fisheries and aquaculture

As noted in Section 3.2, no permits have been issued for commercial fishing since 2016. Aquaculture, which dominates the fisheries sector, is expected to continue growing. Aquaculture can have both positive and negative impacts on biodiversity. In Hungary, 80% of bird species and 60% of otters live on fish farms (PMO, 2015). While this is positive for birds and otters, this can be harmful to aquaculture production. Aquaculture can also reduce pressure on overexploited wild fish stocks and promote species diversity. However, careful management is important for several reasons (Diana, 2009). Non-native species that escape from aquaculture can become invasive and effluents can cause eutrophication. In addition, there is a risk of disease transmission to wild fish. Finally, ecologically sensitive lands should not be used. These risks are more relevant for intensive aquaculture than fish ponds.

Aquaculture production grew by almost 35% over 2000-15, reaching 1.3% of EU-28 aquaculture production in 2015 (FAO, 2017). The majority of production comes from extensive fish ponds (GoH, 2014b). Carp remains the main fish species produced in fish ponds, but geothermal water resources are providing potential for other species such as the African catfish in intensive systems (Varadi, 2011). Hungary ranks seventh within the European Union in freshwater aquaculture production, representing 6.2% of the total volume. However, it is the third largest producer of common carp and the second largest producer of North African catfish. The Multiannual National Strategy Plan on Aquaculture of Hungary targets a 25% increase in production from 2013 levels by 2023.

Despite some advancements, Hungary (along with other Central and Eastern European countries) has generally lagged in aquaculture innovation relative to other OECD member countries (Varadi, 2011). There is no direct reference to aquaculture in the National Biodiversity Strategy. However, Hungary’s Fisheries Operational Programme 2014-20 sets an objective to protect and restore aquatic biodiversity and ecosystems and promotes environmentally-friendly aquaculture. Under the EU Common Fisheries Policy, aquaculture producers may be eligible for financing from the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund for conversion to organic aquaculture (which requires biodiversity-friendly approaches) that covers loss of revenue or additional costs for three years (EC, 2014b).

5.6.3. Forestry

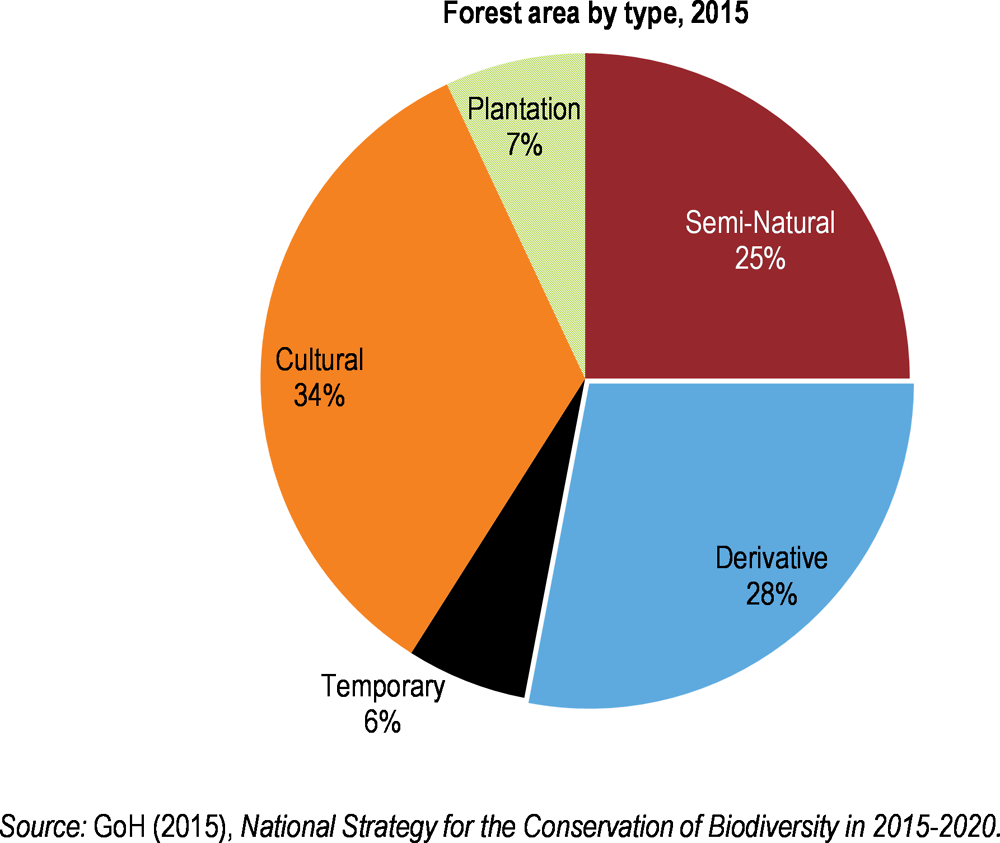

Forest cover (as the share of the total terrestrial area) has increased from a low of 11% in the mid-20th century to 23% in 2014. Significantly, 53% of the forested area is considered favourable to biodiversity because it is close to natural (derivative) or semi-natural (the area covered by natural forests is negligible). The remaining 47% is mainly plantations and semi-plantations of non-native species (Figure 5.9). Some non-native species can be harmful to biodiversity in certain circumstances. For example, the false acacia (black locust) that represents 24% of forest area, can be considered invasive in some environments when it is planted near native vegetation, as it can reduce light for plants and invertebrates and change the microclimate and soil quality (SEP, 2017). Other invasive species represent only around 1% of total managed forest area, but can be relatively concentrated in some regions such as river flood basins. Almost 24% of forests have nature conservation as their primary function, but strict forest reserves account for only 0.6% of total forest area (GoH, 2014b).

While the overall proportion of forests is low, nearly 60% of forests are located in blocks larger than 1 000 ha. The health condition of Hungary’s forests is considered good in comparison to other EU countries and has not changed considerably in the last few years. The government has set a goal of reaching 27% forest coverage by 2050 (GoH, 2017). The area of indigenous trees is increasing, but the overall extent of forest in Hungary only increased by 0.2% between 2010 and 2015 (FAO, 2015; GoH, 2015). Afforestation in protected areas is limited to native tree species. The EU Rural Development Programme provides HUF 50 billion (EUR 160 million) for afforestation over 2014-20, but this will only allow for the plantation of 25 000 ha. The Ministry of Agriculture is, however, planning to launch a national programme to increase forest cover to meet afforestation goals and support biomass energy expansion.

The Forest Act renewed in 2009 categorises forests according to the ratio of native, introduced and invasive tree species. Different management objectives are set for each category, with regulatory decrees specifying tree species for afforestation and forest regeneration, rotation ages by stand categories, the size of buffer zones around bird nesting places and other restrictions. Compensation for forest owners affected by Natura 2000 restrictions began in 2012 and covered 90 000 ha in 2014. Some forestry companies have also implemented management methods voluntarily. Modification of the Forest Act in 2016 has, however, raised concerns among environmental groups about weakening biodiversity safeguards and sustainable forest management. Specifically, they question policies that promote the economic function of forests, that shift the concept of sustainable forest management away from close-to-nature management and that allow the cutting of native tree species with replacement by non-native species (WWF Hungary et al., 2016).

Forest certification has increased, growing from no certification in 2000 to 321 000 ha in 2014 (25% of forest designated for production). All certification is with the Forest Stewardship Council, which implies that products come from responsibly managed forests that are evaluated to meet both environmental and social standards. Further growth in the percentage-certified forest would be worthwhile, consistent with the National Biodiversity Strategy objective to increase nature-friendly forestry.

5.6.4. Spatial planning

Outside of the agriculture, forestry and fishery/aquaculture sectors, there is little direct reference to biodiversity-related actions in sectoral plans and no reference to other sectors in the National Biodiversity Strategy. In those other sectors, spatial planning is a key tool for mainstreaming. However, it is not clear that decision makers always give equal weight to biodiversity considerations in specific development projects.

Hungary’s National Spatial Plan, developed by the Prime Minister’s Office, was established through legislation in 2003. It defines specific zones, with detailed regulation of what can take place within the zones. These requirements must guide municipal-, regional- and national-level planning. The plan has also undergone a SEA.

The National Ecological Network (updated in 2014) includes natural and semi-natural habitats of national importance (including Natura 2000 areas) and a system of ecological corridors and buffer zones that links the core areas together. The network covered 36.4% of the country in 2016, up 0.4% from 2008 (Figure 5.10). Of the total area, 54% is defined as core, 25% as ecological corridors and 21% as buffer zones. The National Spatial Plan imposes rules that restrict development, transportation infrastructure or new open pit mines within the zone. For example, transport infrastructure is permitted as long as it integrates wildlife passages below or above highways, which ensure the survival of natural habitat and functioning of ecological corridors. However, technical solutions will not be enough to mitigate the impacts of habitat fragmentation or loss for some species. The zones of the network, in terms of core areas, ecological corridors and buffer zones, were harmonised with the Pan-European ecological network category system in 2009.

There are also other zones with specific requirements, including the Zone of High Water Bed (3% of territory); the Zone of Excellent-quality Forest Areas (12% of territory); the Zone of World Heritage Sites; the Zone of Excellent-quality Arable Land Areas; and the Zone of Areas of High Importance Landscape. Regional and county spatial plans guide settlement structural plans at the local level. As noted in Chapter 2. , SEA of local structural plans has been required since 2005, but very few have actually been conducted.

The National Environmental Programme also includes objectives related to increasing both the quantity and quality of urban green spaces. Most implementation measures are, however, at the county and local level. These include surveying underused urban areas and increasing their green spaces by giving them new functions and setting up a cadastre of brownfield sites at the municipal level. Environmental groups have, however, expressed concern that these measures are not implemented.

Transportation, and road transport in particular, is also rapidly increasing. Approximately 394 km of new highways were built in 2009-16. Some new roads affect protected areas, despite the requirements of the National Spatial Plan. A 2009 study estimated the annual costs of habitat fragmentation and loss associated with the public road network at HUF 34.4 billion (EUR 111 million). The costs of the railway network were estimated at HUF 19.5 billion (EUR 63 million) (Lukács et al., 2009). The National Environmental Programme calls for consideration of nature, environment, water management, and landscape conservation aspects during preparation and implementation of transport infrastructure. This, in turn, would help mainstream conservation of ecological values. However, implementation is weakened by a lack of biodiversity expertise and territorial-level indicators to support decision making. The new Operational Programme for Integrated Transport anticipates the addition of almost 240 km of highway and prioritises international road and railway accessibility (EC, 2014d).

5.6.5. Energy

The Hungarian Energy Strategy 2030 includes a section on environmental protection and nature conservation, and references landscape and nature conservation requirements in environmental assessments (MND, 2012). No specific measures are outlined, however.

Hungary is one of the largest bioethanol producers in the European Union. Biofuels and biomass electricity production can encourage agricultural expansion, and therefore affect biodiversity. The European Union has set a 2020 target of 10% renewable energy content in transport energy consumption. A country can reach this target through biofuels, electro-mobility and biogas-based transport. Conventional biofuels, which are mainly produced from corn, are permitted to contribute no more than 7% to the target.

The EU directive to reduce indirect land-use change for biofuels and bioliquids (2015/1513/EU) restricts the amount of biofuels produced from food sources. The European Commission has also recommended phasing out conventional biofuels after 2020. In Hungary, mandatory blending requirements for biofuels have been the main policy tool since 2011. The compulsory inclusion level is set at 4.9%, and will go up to 6.4% for 2019-20. While Hungary’s production of biofuels increased significantly between 2000 and 2014, the amount of land used for it decreased by around 4% and is not expected to increase despite the 2020 target.

Biomass use for heat and power production has also increased (Chapter 1. ). Hungary has targets to reach 10.9% renewables in electricity generation, and 18.9% in heating and cooling by 2020. The biomass volume used for this purpose has not yet had a significant impact on land-use change. Future increases in forest plantations intended for energy use could, however, negatively affect biodiversity, depending on the tree species used and forestry practices. In its 2017 review of Hungary, the International Energy Agency posited that the country was close to reaching the limits of biomass production. It recommended pursuit of other renewable technologies such as solar, wind and geothermal (IEA, 2017).

While Hungary has only three major hydroelectric power plants, the facilities must build and operate fish ladders when obstructing the passage of fish on watercourses. Natural or near-natural shoreline of watercourses and lakes are also conserved as a wetland habitat.

5.6.6. Industry

Industry, including construction, represented 32% of value added in Hungary in 2015. Within the industry sector, the main sub-sectors are food products, beverages and tobacco; rubber and plastic products; basic metals and fabricated metal products; and chemicals and chemical products (HCSO, 2017a). Hungary’s oil and gas and mining sectors are relatively small, but there is potential for growth in the future. Sectoral strategies do not include specific measures or indicators relating to biodiversity.

Industrial impacts on biodiversity, water and soil are, however, covered by the EU Environmental Liability Directive, which has been transposed into Hungarian law (Chapter 2. ). EIA can also address the impact of industrial projects on biodiversity. Indications are that the green economy element of the 2016 Irinyi Plan on Innovative Industry Development Directions in Hungary will promote the use of renewable technologies, renewable energy, the circular economy and improved resource efficiency. It could be expanded, however, to also make linkages to biodiversity and limiting risks from pollution or industrial accidents, such as the major toxic spill from a Hungarian alumina factory in 2010 (Chapter 2. ). The 2010 incident clearly shows that industrial accidents can be devastating for biodiversity. Adequate preventive measures recommended by the OECD in the areas of chemical safety and waste management (as part of the OECD acquis) can ultimately support the protection of biodiversity and the environment.

Although mining represents only 0.2% of GDP, Hungary has a number of exploitable deposits of bauxite, manganese and uranium, as well as reserves of crude oil, natural gas, coal and lignite. The Hungarian government is interested in pursuing economic opportunities in mining and fossil fuels, and reducing dependence on imports.

Expanded mining and fossil fuel extraction could have an impact on biodiversity if not managed carefully. Habitat destruction, fragmentation and pollution would be significant risks. Many mineral deposits are located in mountain areas that are both popular tourist attractions and valuable habitat for biodiversity. The National Environmental Programme includes an objective to reduce the environmental impacts and damages during extraction and use of mineral raw materials. However, the measures related to the objective are not specific to biodiversity.

5.6.7. Tourism

The number of overall visits to Hungary increased by almost 20% between 2009 and 2016 (HCSO, 2017b). Eco-tourism is also becoming more popular. Between 2008 and 2014, the number of guest nights and accommodations on national protected areas in Hungary increased by 30.6%. Increased tourism can help contribute to knowledge and awareness of biodiversity. At the same time, it can have negative impacts from increased waste, ecosystem degradation, habitat fragmentation, pollution, soil erosion and disturbance of endangered species.

Inside protected areas in Hungary, the location of visitor infrastructure and nature trails is carefully chosen to avoid impacts on sensitive habitats and species. Outside of protected areas, however, there are few restrictions relating to the impacts of tourism on biodiversity. A travel website for Hungary developed by the Hungarian Tourism Organisation emphasises opportunities for fishing and hunting as part of eco-tourism, but makes no reference to restrictions (GotoHungary, 2017).

Hungary’s National Tourism Development Strategy 2030 is the core document defining the system of targets and methods for tourism management. The document does reference the importance of ecological sustainability and the risks of climate change, intense urbanisation and excessive tourism to popular destinations. It even includes a goal of “co-operative tourism” that works in harmony with the environment. However, no indicator for measuring progress relates to the environment or biodiversity (HTA, 2017). Rather, the focus is on increasing tourism, with a goal of increasing the contribution of tourism to GDP from 10% to 16% by 2030 (BBJ, 2017). The National Environmental Programme includes a section on tourism, but focuses on objectives related to expanding eco-tourism. It does not address pressures to biodiversity from tourism.

As tourism expands in Hungary, it will be increasingly important to make direct linkages with biodiversity priorities at the national, regional and local levels. In this way, Hungary can identify specific policies and indicators for the sector and include them in tourism and biodiversity strategies. The UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) developed recommendations relating to tourism and biodiversity in 2010. For its part, the Secretariat of the Ramsar Convention partnered with UNWTO in 2012 to provide guidance on sustainable tourism in wetlands (UNWTO, 2010; SRCW/UNWTO, 2012). Private operators within the tourism industry could also be encouraged to seek sustainable tourism certification through the Global Sustainable Tourism Council or another body. Chile, for example, created its own sustainable criteria for Chilean Tourist Accommodation and Destinations, drawing on work by the UNWTO (OECD/ ECLAC, 2016).

Strategic and institutional framework

-

Expand the National Biodiversity Strategy to incorporate specific commitments and indicators related to energy, transport, tourism, industry and mining; improve policy coherence and cross-linkage with sectoral strategies and plans; ensure clear accountability for achieving targets; identify financial and human resources for specific actions to achieve targets.

Information systems

-

Continue to improve knowledge of the extent and value of ecosystem services and habitat and soil maps within and outside protected areas, sectoral data sharing, and accessibility and communication of information to the public.

Biodiversity protection and financing

-

Ensure measures are in place to enhance the conservation status of threatened species, both in and outside protected areas by improving wildlife corridors and restricting infrastructure expansion to reduce fragmentation of habitats.

-

Complete management plans of protected areas with legal force and ensure sufficient financial resources for effective implementation; provide dedicated budgets for nature conservation departments to improve the predictability of financing and reduce the risk of shifting short-term priorities; increase budget funding for National Park Directorates to reduce the need for substantial revenue-raising activity that may be contrary to biodiversity objectives.

Mainstreaming biodiversity across sectors

-

Implement additional measures in the agricultural sector to reduce ammonia emissions, curb pesticide use and limit cultivation of flooded land; use subsidies and payments for ecosystem services and information provision to promote the modernisation of irrigation systems, nature conservation and restoration activities outside of protected areas; significantly increase the share of organic farming.

-

Expand afforestation of indigenous species beyond protected areas; increase sustainability certification of forest companies; maintain sustainable forest management objectives.

-

Improve the effectiveness of the National Ecological Network Zone instrument and other spatial planning policies by developing regional-level biodiversity indicators and using biodiversity experts to support informed decisions; avoid destruction of green space and fragmentation of habitat where possible, including in areas with no formal protection.

-

Monitor the impact of biofuel and biomass production on land-use change and other factors influencing biodiversity, producing publicly available indicators to help inform decision making; give preference to added-value organic farming over biofuel and biomass production.

References

Bata, T. and G. Mezosi (2013), Assessing Landscape Sensitivity Based on Fragmentation Caused by the Artificial Barriers in Hungary, April 2013, University of Szeged, www.researchgate.net/publication/272124261.

BBJ (2017), “Tourism strategy focuses on sports, culture and health”, Budapest Business Journal, 17 October 2017, https://bbj.hu/politics/tourism-strategy-focuses-on-sports-culture-and-health-_140324.

Benedetti, L. (2015), “Hungary’s nature is in peril”, Birdlife Hungary News blog, 11 May 2015, www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/news/hungary%E2%80%99s-nature-peril.

CBD (2017), Hungary – Country Profile website, www.cbd.int/countries/profile/default.shtml?country=hu (accessed 20 June 2017).

CCH (2017), The Constitutional Court Adopted Another Decision Protecting Natural Resources, The Constitutional Court of Hungary, 26 October 2017, http://hunconcourt.hu/announcement/the-constitutional-court-adopted-another-decision-protecting-natural-resources-2/.

Climate Change Post (2017), Biodiversity Hungary website, www.climatechangepost.com/hungary/biodiversity/ (accessed 20 June 2017).

Diana, J.S. (2009), “Aquaculture production and biodiversity conservation”, Bioscience, Vol. 59/1, Oxford University Press, pp. 27-38, https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2009.59.1.7.

EC (2018), Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/38 of 12 December 2017 adopting the ninth update of the list of sites of community importance for the Pannonian biogeographical region, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 January 2018, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32018D0038&from=EN.

EC (2017a), “Attitudes of European citizens towards the environment”, Special Eurobarometer, No. 468, October 2017, European Commission, Brussels, http://mehi.hu/sites/default/files/ebs_468_en_1.pdf.

EC (2017b), Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on Member State National Action Plans and on progress in the implementation of Directive 2009/128/EC on the Sustainable Use of Pesticides, 10 October 2017, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/plant/docs/pesticides_sup_report-overview_en.pdf.

EC (2014a), Factsheet on 2014-2020 Rural Development Programme for Hungary, European Commission, Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/rural-development-2014-2020/country-files/hu/factsheet-hungary_en.pdf.

EC (2014b), Organic Farming: A Guide on Support Opportunities for Organic Producers in Europe, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/organic/sites/orgfarming/files/docs/body/support-opportunities-guide_en.pdf.

EC (2014c), Summary of the Partnership Agreement for Hungary, 2014-2020, 26 August 2014, European Commission, Brussels, www.palyazat.gov.hu/program_szechenyi_2020.

EC (2014d), Integrated Transport Operational Programme 2014-2020: Hungary, European Commission, Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/atlas/programmes/2014-2020/hungary/2014hu16m1op003.

EC (2013), “Impact Assessment” accompanying the document Proposal for a Council and European Parliament Regulation on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species, Staff Working Document, SWD 2013, 0321 final, European Commission, Brussels, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52013SC0321&from=EN.

EC (2009), Natura 2000 in the Pannonian Region, European Commission, Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/platform/knowledge_base/150_pannonian_region_en.htm.

EEA (2011), “Landscape fragmentation in Europe”, EEA Report, No. 2/2011, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen, www.eea.europa.eu/publications/landscape-fragmentation-in-europe.

EMEP (2017), WebDab (database), www.ceip.at/webdab_emepdatabase/ (accessed 11 October 2017).

FAO (2017), FAO Statistics, Global Aquaculture Production (database), www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/global-aquaculture-production/en (accessed 18 June 2017).

FAO (2015), Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 website, www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/en/ (accessed 25 June 2017).

FiBL and iFOAM (2017), The World of Organic Agriculture 2017, Willer, H. and J. Lernoud, eds., Research Institute of Organic Agriculture and Organics International, Frick, Switzerland, https://shop.fibl.org/CHen/mwdownloads/download/link/id/785/?ref=1.

GoH (2017), National Landscape Strategy (2017-2026), Government of Hungary, Budapest, www.kormany.hu/download/f/8f/11000/Hungarian%20National%20Landscape%20Strategy_2017-2026_webre.pdf.

GoH (2015), National Strategy for the Conservation of Biodiversity in 2015-2020, Government of Hungary, Budapest, www.cbd.int/doc/world/hu/hu-nbsap-v2-en.pdf.

GoH (2014a), National Summary for Article 17, Government of Hungary, Budapest, https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/d5c1f10b-7a2d-444d-9738-c8cdd0295b9f/HU_20140528.pdf.

GoH (2014b), Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity – Hungary, Government of Hungary, Budapest, April 2014, www.cbd.int/doc/world/hu/hu-nr-05-en.pdf.

GoH (2013), National Framework Strategy on Sustainable Development of Hungary, Government of Hungary, Budapest, www.stakeholderforum.org/fileadmin/files/National%20Framework%20Strategy%20on%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf.

GotoHungary (2017), Back to Nature! Ecotourism in Hungary website, http://gotohungary.com/eco-tourism2 (accessed 16 November 2017).

HCSO (2017a), Value of industrial production and sales, in Time Series of Annual Data – Industry, Hungarian Central Statistical Office, www.ksh.hu/stadat_annual_4_2 (accessed 12 June 2017).

HCSO (2017b), The number of inbound trips to Hungary and the related expenditures, in Time Series of Annual Data – Tourism, Catering 2009-2016, Hungarian Central Statistical Office, www.ksh.hu/docs/eng/xstadat/xstadat_annual/i_ogt002a.html (accessed 4 July 2017).

HDN (2017), “Government accepts tourism development strategy in Hungary”, Hungarian Daily News, 16 October 2017, https://dailynewshungary.com/government-accepts-tourism-development-strategy-hungary/.

HTA (2017), National Tourism Development Strategy 2030: Executive Summary, Hungarian Tourism Agency, Budapest, http://szakmai.itthon.hu/documents/28123/44398839/mtu_strategia_2030-english.pdf/79fc6922-095c-4e7b-89de-6aeebaa49f91.

ICPDR (2015), The Danube River Basin District Management Plan: Update 2015 website, www.icpdr.org/main/management-plans-danube-river-basin-published (accessed 3 July 2017).

ICPDR (2006), Danube Facts and Figures: Hungary website, www.icpdr.org/main/danube-basin/hungary (accessed 3 July 2017).

IEA (2017), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Hungary 2017, IEA, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278264-en.

IUCN (2013), Hungary’s Biodiversity at Risk: A Call for Action, International Union for Conservation of Nature, May 2013, https://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/hungary_s_biodiversity_at_risk_fact_sheet_may_2013.pdf.

Lukács, A. et al. (2009), The Social Balance of Road and Rail Transport in Hungary, www.levego.hu/sites/default/files/social_balance_transport_hungary_20110131.pdf.

Mihók, B. et al. (2017), “Biodiversity on the waves of history: Conservation in a changing social and institutional environment in Hungary, a post-soviet EU member state”, Biological Conservation, Vol. 211 (2017), Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 67-75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.05.005.

MND (2012), National Energy Strategy 2030, Ministry of National Development of Hungary, Budapest, www.iea.org/media/pams/hungary/HungarianEnergyStrategy2030.pdf.

MRD (2017), Together for a GMO-free Agriculture website, http://gmo.kormany.hu/domestic-regulation (accessed 3 July 2017).

NPT (2017), Nemzeti Parki Termék (National Park Products) website, http://nemzetiparkitermek.hu/ (accessed 15 September 2017).

OECD/ECLAC (2016), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Chile 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252615-en.

OMSZ (2017), Informative Inventory Report 2015, (CLRTAP reporting) Hungarian Meteorological Service, Budapest.

OMSZ (2017), National Inventory Report for 1985-2015, (UNFCCC reporting) Hungarian Meteorological Service, Budapest.

PMO (2015), Fisheries Operational Programme of Hungary 2007-2013, Prime Minister’s Office, http://halaszat.kormany.hu/download/9/6c/01000/HOP2007-2013_4mod_eng20150521.pdf.

Ramsar (2017), Annotated List of Wetlands of International Importance: Hungary website, www.ramsar.org/wetland/hungary (accessed 29 June 2017).

Salamin, G. (2009), “Planning spatial development in Hungary”, presentation at the national processes and co-operation of Visegrád four countries workshop, Vienna, 17 June 2009, www.oerok.gv.at/fileadmin/Bilder/2.Reiter-Raum_u._Region/1.OEREK/OEREK_2011/8_SALAMIN_VATI.pdf.