Chapter 8. Compliance and enforcement

This chapter reviews how Slovenia’s strategy for enforcement and compliance, including the appeals process. Finally, it makes recommendations for how Slovenia could improve its enforcement and compliance regime. Although this area was not the primary focus of the regulatory policy review, this chapter does make some general recommendations for compliance and enforcement in Slovenia. An in-depth review could be done using the OECD Compliance and Enforcement Toolkit, which the OECD is currently developing.

The baseline for reviewing inspection and enforcement reform

This section uses the eleven best-practice principles that the OECD has compiled, based on international experience, as reference point for assessing Slovenia’s inspection and enforcement reform (Box 8.1).

-

Evidence based enforcement. Regulatory enforcement and inspections should be evidence-based and measurement-based: deciding what to inspect and how should be grounded on data and evidence, and results should be evaluated regularly.

-

Selectivity. Promoting compliance and enforcing rules should be left to market forces, private sector and civil society actions wherever possible: inspections and enforcement cannot be everywhere and address everything, and there are many other ways to achieve regulations’ objectives.

-

Risk focus and proportionality. Enforcement needs to be risk-based and proportionate: the frequency of inspections and the resources employed should be proportional to the level of risk and enforcement actions should be aiming at reducing the actual risk posed by infractions.

-

Responsive regulation. Enforcement should be based on “responsive regulation” principles: inspection enforcement actions should be modulated depending on the profile and behaviour of specific businesses.

-

Long term vision. Governments should adopt policies on regulatory enforcement and inspections: clear objectives should be set and institutional mechanisms set up with clear objectives and a long-term road-map.

-

Co-ordination and consolidation. Inspection functions should be co-ordinated and, where needed, consolidated: less duplication and overlaps will ensure better use of public resources, minimise burden on regulated subjects, and maximise effectiveness.

-

Transparent governance. Governance structures and human resources policies for regulatory enforcement should support transparency, professionalism, and results-oriented management. Execution of regulatory enforcement should be independent from political influence, and compliance promotion efforts should be rewarded.

-

Information integration. Information and communication technologies should be used to maximise risk-focus, co-ordination and information-sharing – as well as optimal use of resources.

-

Clear and fair process. Governments should ensure clarity of rules and process for enforcement and inspections: coherent legislation to organise inspections and enforcement needs to be adopted and published, and clearly articulate rights and obligations of officials and of businesses.

-

Compliance promotion. Transparency and compliance should be promoted through the use of appropriate instruments such as guidance, toolkits and checklists.

-

Professionalism. Inspectors should be trained and managed to ensure professionalism, integrity, consistency and transparency: this requires substantial training focusing not only on technical but also on generic inspection skills, and official guidelines for inspectors to help ensure consistency and fairness.

Source: OECD (2014), Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208117-en.

Compliance and enforcement policy framework in Slovenia

Regulations cannot be effective unless the regulation is “fit for purpose” and the regulated businesses and actors comply with the regulation. Well-designed regulation is not enough to bring benefits to citizens. Businesses and other regulatory actors must comply with the regulation for it to have any positive impact on citizens, such as better food safety, environmental protection and consumer safety.

In Slovenia, the Inspections Act, last updated in 2014, regulates most areas of compliance and enforcement, including:

-

general principles of inspection

-

organisation of inspection

-

status

-

rights and duties of inspectors

-

inspectors’ powers

-

the inspection procedure

-

inspection measures and

-

other issues relating to inspection.

The Inspections Act also contains 4 key principles to guide inspectors (see Box 8.2);

-

Principle of independence (Article 4)

-

Principle of the protection of the public interest and private interests (Article 5)

-

Principle of publicity (Article 6)

-

Principle of proportionality (Article 7).

Compliance and enforcement reform has come in three major stages since independence. The first major reform to Slovenia’s compliance and enforcement regime took place in 1995, when the Inspections Act was modified to split public administration between the state and municipal level. In addition the 1995 reform also placed inspectorates under their respective ministry and benefited from a higher level of autonomy.

In 2002, the Inspection Council was created to boost co-ordination between inspectorates, organising common inspections and encourage information exchange and legal aid. Changes to the Inspections Act have been generally minor since 2002. Later developments in 2005 and 2007 allowed the Inspection Council to conduct procedures for minor offences and strengthened regional co-ordination of inspections. According to the EU, the reforms led to a significant reduction in the number of appeals against inspectors’ decisions.

Inspectors operate within inspectorates and agencies, which are bodies within line ministries. Currently, there are 34 administrative bodies within Slovenia’s line ministries, including inspectorates, agencies, and other administrative bodies, such as the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia.

The Chief Inspector of each inspectorate must submit to the competent minister and to the Inspection Council annual reports containing information on the number of cases, the time required for resolving a particular case, meeting time limits in resolving particular cases, and the implementation of annual work plans.

Principle of independence: In performing inspection duties, inspectors shall, within the framework of their powers, act independently.

Principle of the protection of the public interest and private interests: Inspectors shall perform inspection duties with the purpose of protecting the public interest and the interests of legal and natural persons.

Principle of publicity: On the basis of and within the limits of the authorisation of the head, inspectors shall inform the public of their findings and measures taken if this is necessary to protect the rights of legal or natural persons and if this is necessary to ensure respect for the legal order or its provisions.

Principle of proportionality: Inspectors shall perform their duties in such a manner that, in exercising their powers, they shall interfere with the operation of legal and natural persons only to the extent necessary to ensure an effective inspection.

In the selection of measures, inspectors, taking account of the gravity of the violation, shall impose a measure more favourable to the person liable if this achieves the purpose of the regulation.

In setting the time limit for the elimination of irregularities, an inspector shall take into account the gravity of the violation, its consequences for the public interest and the circumstances determining the time period within which the natural or legal person supervised by the inspector (hereinafter: the person liable) can, by acting with due care, eliminate irregularities.

Source: Inspections Act, Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, No. 56/2002, 26/2007, 40/2014 (accessed 10 August 2017).

Unfortunately, according to Florentin Blanc, “gray areas” in which multiple inspectorates cover the same policy area still existed as late as 2012 (Blanc, 2012) even after reforms and the establishment of the Inspection Council. For example, several inspectorates and agencies in Slovenia are charged with the inspection of nuclear material. Some countries have completed sectoral reviews of enforcement regimes to reduce overlap and simplify co-ordination and administration of enforcement procedures (see Box 8.3). The last amendments in 2014 were increasing the efficiency and co-ordination of inspection services. On the basis of amendments, the work of the inspectors is based on the annual work planning, about which the Government is notified in advance.

Sir Philip Hampton’s 2005 review, “Reducing administrative burdens: effective inspection and enforcement” considered how to reduce unnecessary administration for businesses. The Hampton Review set out some key principles that should be consistently applied throughout the regulatory system:

-

regulators, and the regulatory system as a whole, should use comprehensive risk assessment to concentrate resources on the areas that need them most

-

regulators should be accountable for the efficiency and effectiveness of their activities, while remaining independent in the decisions they take

-

no inspection should take place without a reason

-

businesses should not have to give unnecessary information, nor give the same piece of information twice

-

the few businesses that persistently break regulations should be identified quickly and face proportionate and meaningful sanctions

-

regulators should provide authoritative, accessible advice easily and cheaply

-

regulators should be of the right size and scope, and no new regulator should be created where an existing one can do the work; and

-

regulators should recognise that a key element of their activity will be to allow, or even encourage, economic progress and only to intervene when there is a clear case for protection.

Source: “Assessing our Regulatory System – The Hampton Review”, Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2005), http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.bis.gov.uk/policies/better-regulation/improving-regulatory-delivery/assessing-our-regulatory-system.

Risk-based approaches to compliance

Regulatory enforcement strategies in Slovenia are still mostly based on sanctions. However, there is some development in the use of alternative approaches such as:

-

Risk-based inspections planning: Inspectorates are planning their work on the basis of risk-assessments and reallocate resources to in-depth audits in high-risk areas.

-

Co-ordination and joint planning: Membership in the Inspection Council, a permanent interministerial working body, is rapidly increasing to enhance co-ordination in inspections. In addition to the common long-term and short-term objectives, the work of inspections is co-ordinated in terms of better use of public resources.

-

Organisational measures: In August 2014, mainly operative Customs Administration of the Republic of Slovenia (CURS) and mostly administrative Tax Administration of the Republic of Slovenia (DURS) merged into the Financial Administration of the Republic of Slovenia (Furs). The priority tasks of Furs are detection of tax evasions, and customs and excise duty irregularities, preventive activities, supervision of cash operation, combat against smuggling and detection of smuggled goods (illicit drugs, forgeries), with a special emphasis on fight against undeclared work.

-

Information integration: At the Ministry of Public Administration is in the planning stage a project called eInspections, whose main aim is to use information and communication technologies to maximise risk-focus, co-ordination and information-sharing – as well as optimal use of resources.

-

Informing stakeholders: On the websites of inspections we can find guidelines, frequently asked questions and answers, useful information and toolkits.

-

Public campaigns: In recent years we have witnessed a number of public campaigns aimed at strengthening compliance (see Box 8.4).

The public campaign “Let’s stop undeclared work” – aimed at preventing undeclared work – was launched on 31 August 2010 by the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs, in co-operation with the relevant supervisory authorities and with the support of the social partners.

The campaign was aimed at the general public, especially enterprises, workers and consumers, and set out to:

-

inform people about the benefits of paying taxes and to emphasise the fact that social security contributions provide social security,

-

raise awareness regarding the negative effects for the consumers (i.e. no invoice = no warranty);

-

promote a positive image of compliance with employment and social security regulation and to emphasise the importance and purpose of the payment of social security contributions and the payment of taxes.

-

underline the negative effects of undeclared work that leads to unfair market competition: business entities that are operating in accordance with the regulations are disadvantaged as they cannot compete with those engaged in undeclared work.

Posters and leaflets aimed at the general public were available at all regional offices of the Employment Service of Slovenia, at social work centres, local administrative units, at the tax office. They were distributed also through the offices of all social partners participating in the campaign. Promotional materials were available also at various trade fair activities organised by these institutions. Promotional materials were posted on the state administration, supervisory authorities and e-government websites. Ads were published in various magazines aimed at entrepreneurs and craftsmen as well as on the radio. The campaign more precisely included the following promotional materials:

-

print of hoardings and rental of poster sites at 60 different locations;

-

print and distribution of leaflets in the range of 30 000 pieces;

-

print and distribution of B2 size posters in the range of 700 pieces;

-

production and release of radio ads on radio stations VAL 202 and Radio Centre (ads were playing for one week); www.protisiviekonomiji.si/fileadmin/template/vklopi_razum/images/slider/slider.jpg;

-

publication of ads in the journal Craftsman (Obrtnik), Entrepreneur (Podjetnik), in the gazette of Slovenian Chamber of Commerce;

-

publication of campaign banners and logos on the websites of ministries, supervisory authorities and participant institutions.

In February 2015 the Government decided to launch a public campaign “Activate your mind – Request an invoice!”, aimed at raising public awareness of the negative impacts of the informal economy. In addition to promotional activities in the form of posters, leaflets, radio and TV advertising, a website www.protisiviekonomiji.si/ was created.

Citizens can use web application to scan received invoice and send it to the financial administration. On the website names of citizens receiving a prize of EUR 15 000 are published. Promotional video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7aqabkksqao.

Source: Responses to the Slovenia Regulatory Policy Review Survey.

Appeals

The Slovenian Constitution defines the right to legal remedies as one of the basic human rights and fundamental freedoms. Everyone is guaranteed the right to appeal or to any other legal remedy against the decisions of courts and other state authorities, local community authorities, and bearers of public authority that determines rights, duties, or legal interests.

The General Administrative Procedure Act,1 in force since 2000, regulates administrative procedures in Slovenia. Administrative sanctions issued as a result of administrative procedures are subject to an administrative appeal, which is mandatory before a review of legality by the Administrative Court. An administrative appeal is filed on average in approximately 1-3% of cases.

The General Administrative Procedure Act (GAPA) furthermore lists seven procedural failures, which are considered to be severe violations. These can be classed into three groups:

-

issues relating to unlawfulness (illegality) linked to the administrative body (jurisdiction, the impartiality of officials),

-

issues relating to the party (legal interest, proper representation, the right to be heard, communication in an official language), and

-

issues relating to the administrative act as a prescribed form (such as the fact that it must be in writing and contain the prescribed elements).

In Slovenia, the judicial review in administrative matters is defined by the 2006 Administrative Dispute Act (Zakon o upravnem sporu, ZUS-1, ADA). After a decision by the Administrative Court or the appellate Supreme Court, parties may also pursue the matter before the Constitutional Court as well as the European Court of Human Rights. This sometimes makes the protection of parties’ rights rather difficult since in order to have access to court the parties must exhaust all prior remedies, which is often quite ineffective due to the months-long procedures.

An appeal must be filed in 15 days, unless statute provides otherwise. In the case of regulatory enforcement decisions issued by the bodies affiliated to the ministries, the line ministry is the appellate authority. The ministry examines whether an appeal is allowed and due, and whether it was filed by an entitled person. If the appeal is not allowed, if it is late, or if it was not filed by an entitled person, it is rejected by an order.

Assessment and recommendations

The Slovenia government could consider sector reviews and reviews of inspectorates’ competencies where necessary to simplify administration of compliance and enforcement. A continuing challenge for compliance and enforcement in Slovenia is co-ordination. Although the Inspection Council has greatly supported interagency co-ordination on compliance and enforcement, some institutional gaps remain. Specifically, areas of enforcement are sometimes still spread among several institutions when consolidation may simplify administration. On the other hand, the Market Inspectorate has an extremely wide-range of responsibilities across varied policy areas. In this case, it may be possible reorganise or consolidate inspection duties to be more effective.

The government should bolster the use risk-based approaches to enforcement in Slovenia. Regulatory enforcement strategies continue to be mostly based on prescribing sanctions to regulated businesses and individuals. The Government of Slovenia should introduce changes to the Inspections Act to encourage inspectors to use risk-based strategies, such as warnings for minor or unintentional infractions, so that strained inspection resources can be used to in-depth audits of high-risk areas. All inspectorates should move to focus on raising compliance rather than simply handing out sanctions. They could accomplish this by issuing guidance materials, providing inspection checklists, or through information portals (see Principle 10 of the Compliance and Enforcement Principles).

Compliance and enforcement strategies should be developed along with the draft proposals. In many cases in Slovenia, it appears that regulations were developed without considering how it would strain compliance and enforcement resources that are already spread thin. The Government of Slovenia’s fiscal constraints over the past few years have created a situation where inspectorates’ budgets have not always grown with their responsibilities. Ministries should always plan and account for the costs and implementation of enforcing a regulation during the development of regulation, so that resources can be targets to ensure compliance once the law is promulgated.

Slovenia could develop a central information system to share information on specific businesses between inspectorates. The central information system could include company profiles with information that helps inspectors make targeted decisions about which businesses may be the most likely to not be in compliance. The information system would be accessible to all inspectors and could also help them jointly plan inspections of specific businesses.

Bibliography

OECD (2014), Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208117-en.

OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

Blanc, F. and G. Ottimofiore (2012), “Regulatory and Supervisory Authorities in Council of Europe Member States Responsible for Inspections and Control of Activities in the Economic Sphere – structures, practices and examples”, Technical Paper prepared for the PRECOP-FR.

Blanc, F. (2012), “Inspection Reforms: Why, How, and with what effect”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/s0_overall%20report%20presentation_fb_final%20edit.pdf (accessed 3 January 2018).

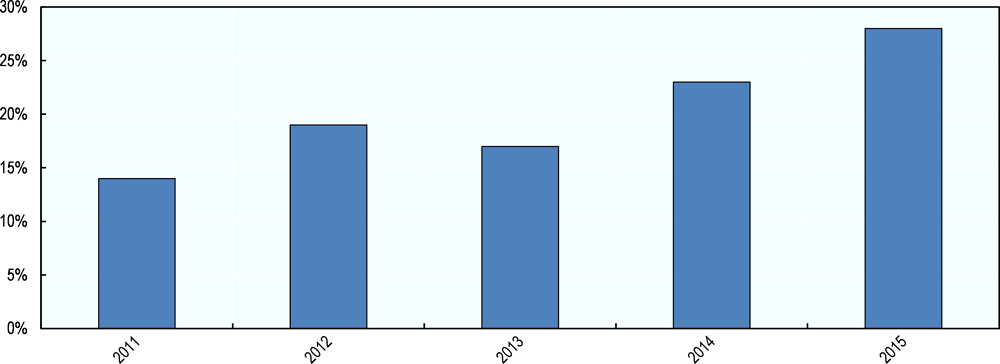

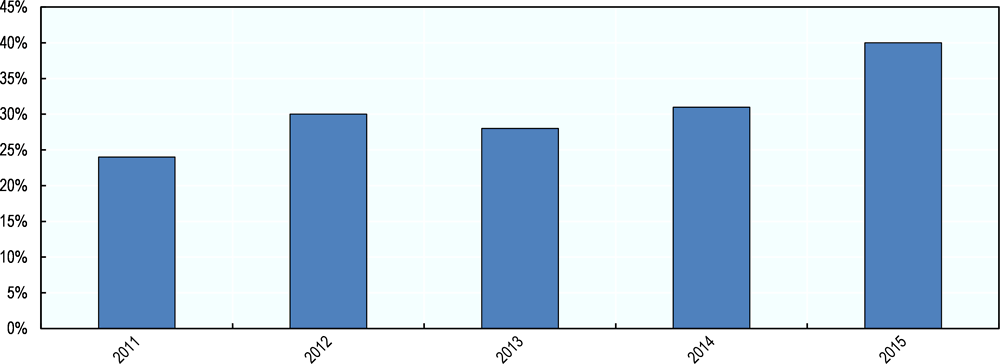

Ministries who participated in the preparation of responses for the Slovenia regulatory policy review estimated generally high level of compliance with regulations, though compliance rates are not monitored systematically.

Inspection bodies act as bodies affiliated to the ministries:

-

Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities

-

Labour Inspectorate

-

Ministry of Finance

-

Financial Administration

-

Public Payments Administration

-

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food

-

Inspectorate for Agriculture and the Environment

-

The Administration for Food Safety, Veterinary and Plant Protection

-

Ministry of Culture

-

Culture and Media Inspectorate

-

Ministry of the Interior

-

Inspectorate for Interior Affairs

-

Ministry of Public Administration

-

Public Sector Inspectorate

-

Ministry of Defence

-

Defence Inspectorate

-

Inspectorate for Protection against Natural and Other Disasters

-

Ministry of Infrastructure

-

Infrastructure Inspectorate

-

Maritime Administration

-

Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning

-

Inspectorate of the Republic of Slovenia for the Environment and Spatial Planning

-

Nuclear Safety Administration

-

Ministry of Economic Development and Technology

-

Market Inspectorate

-

Metrology Institute of the Republic of Slovenia

-

Ministry of Education, Science and Sport

-

Inspectorate for Education and Sport

-

Ministry of Health

-

Health Inspectorate

Inspection bodies publish criteria to prioritise inspections, taking into account risk assessment in each area. They also publish annual reports and work plans for the coming year.

Some key findings of the inspection bodies:

Market Inspectorate

Market Inspectorate carried out 16 982 inspections in 2015. It imposed 4 144 administrative measures (3 785 warnings based on the Inspection Act2 and 1 359 administrative decisions) and 6 950 offence proceedings.

Labour Inspectorate

Labour Inspectorate conducted 16 077 inspections in 2015. It imposed 12 056 administrative measures and offence proceedings (12 122 2014). The Inspectorate finds that situation in the area of occupational safety and health is deteriorating, as the number of offenses detected increases over the years.3

Financial administration

Inspection Council

Based on the Inspection Act4 (Official Gazette of RS, No. 43/07 – official consolidated text and 40/14) Inspection Council, the permanent interministerial working body for the mutual co-ordination of work, was established.

According to data from the annual report 520.181 inspections were carried out in 2015. There were 88 157 imposed measures – 53 099 administrative measures and 35 058 offence proceedings.5

In 2014, 519 097 inspections were carried out. There were 83 328 imposed measures – 53 134 administrative measures and 30 194 offence proceedings.

Compared to 2014, there were 4.01% more administrative measures and 2.04% less offence proceedings imposed in 2013.

Relevance of inspections and enforcement issues

Designing and adopting sound regulations is of little use if they are not complied with – and, to promote such compliance, appropriate systems and measures need to be in place, including effective and efficient regulatory inspections and enforcement. International experience and research have shown that this is unfortunately often far from being the case, and that inspection and enforcement regimes are often simultaneously burdensome and ineffective (see e.g. Hampton, 2005; World Bank Group, 2011; OECD, 2012, 2014).

Such a combination of ineffectiveness at achieving the stated goals of regulation (safety, health, or any other type of public benefit and welfare), and of considerable economic burden (loss of time, turnover and resources for active businesses – and decreased investment because of regulatory uncertainty), is particularly sharply in evidence in “transition” economies, notably those of countries that used to be part of the former Soviet Union. The reasons for this are many, and include several traits that have been “carried over” from the previous command-economy system:

Regulatory regimes that are highly prescriptive and cover far more aspects of economic activity than accepted good practice – resulting in more fields and types of regulatory control

A large number of institutions in charge of regulatory control and enforcement, with relatively high staffing levels – which mechanically drive a larger number of inspections, a high degree of fragmentation, as well as an important “constituency” that tends to resist changes towards a different (somewhat “lighter touch”) system.

Crucially, an approach to regulatory enforcement and a vision of regulatory drivers that are founded on an “adversarial” approach to duty holders (businesses, and also citizens) – this approach emphasises deterrence rather than trust, and reflects a “presumed guilty” view.

In addition, in a number of countries, these aspects are compounded by an overall weak rule of law, insufficient compensation for inspectors, and deep ethical issues in public administration, and result in inspections being primarily an instrument of corruption.6 This, of course, results in inspections that also completely cease to fulfil their stated function – ensuring that the goals of regulations are achieved.

Improving regulatory inspections and enforcement regimes is thus a priority that corresponds to a set of objectives for governments: reducing the economic burden and thus facilitating investment and growth and maximising the regulatory effectiveness in terms of social welfare with constant or decreasing state resources (particularly important in times of economic crisis. In “transition” economies, reducing corruption (that contributes to both objectives) is also often specifically articulated as a priority. More deeply, inspection regimes that are more effective, efficient and transparent (and, of course, not corrupt) strongly contribute to reinforcing the legitimacy of public action and authorities, and this in turn drives improved compliance.

Drivers of compliance: striking the right balance

A common view underpinning “heavy handed” inspection and enforcement approaches is that people comply with rules only if they are under supervision and there is a realistic threat of punishment for violations. This “dissuasion-based” view results in efforts to inspect each and every establishment as often as possible. It is found in every country around the world, but is particularly strong in post-Soviet regulatory regimes, fueled by a history of hostility towards and suspicion of private initiative. Business operators are held to be pure rational calculators, only likely to comply if the costs of non-compliance are high, and punishment close to certain.

In fact, decades of research and international examples show decisively that this view is mistaken, and that such an approach results in disappointing compliance levels. Across a number of countries and fields, it has been found that compliance is fostered by at least three types of drivers: moral values, legitimacy of authorities, and rational calculations (dissuasion) – but that dissuasion appears to be the weakest of the three. In addition, even though inspections and enforcement can promote compliance through dissuasion, when they are perceived as excessive, heavy-handed, unethical or otherwise not transparent, they produce negative effects in terms of compliance that tend to outweigh whatever benefits dissuasion may have produced (see e.g. Tyler, 2003; Kirchler, 2007; Blanc et al., 2015).

Moral values are one of the strongest drivers of compliance. Though primarily formed during childhood, they can be influenced through public policy and regulatory interventions – but on the long term (e.g. through school education). For this reason, and because moral values are not always easily connected to regulations, it is not possible to design interventions to promote regulatory compliance that would rely exclusively on moral values.

Dissuasion is, clearly, a driver of compliance that is more “straightforward” to use in regulatory interventions – but it has important limitations. First, even to the extent that probability of detection and fear of punishment do play a role, their effects are mediated by the values of the regulated subjects (see Kirchler, 2007) – meaning that those whose moral values already tend to support compliance will experience a stronger dissuasion effect, but those whose moral values do not will be far less influenced (whereas these are precisely those that need to be influenced). Second, really strong dissuasion tends to have considerable costs – both in terms of finances and freedom (personal and economic). In practice, strong deterrence is impossible to achieve in most cases: the resources required would be far too high (in a world of limited resources, society cannot commit enough resources to deterring violations in each and every regulatory field), and the intrusion on privacy and limitations of individual freedoms would be far too high (see Tyler, 2003). Finally, when efforts at dissuasion are felt to be excessively intrusive or even abusive (indiscriminate visits and checks, as well as sanctions imposed regardless of the risk level, disrespectful and/or unethical behaviour by inspectors, requirements that hinder initiative too strongly etc.), they tend to negatively affect procedural justice, which in turn weakens what is probably the strongest of compliance drivers. This phenomenon is particularly well in evidence in post-Soviet states, where extensive regulations and heavy enforcement are not accompanied by high compliance, but rather by a general disrespect of rules, which tend to be seen as being tools of oppression or graft, and not as instruments of safety and social welfare.

Indeed, the degree to which regulated subjects (citizens, business operators…) find authorities and rules legitimate has consistently been found to be one of the strongest drivers of compliance (possibly the strongest one). Most importantly, it is also the one that is most easily influenced (strengthened, or weakened) by the actions of public authorities. In turn, the strongest element influencing legitimacy has been found to be procedural justice – the extent to which actions of public authorities are perceived by those whom they affect as fair, not in terms of their results, but of the process which they follow. Key elements of procedural justice are fairness of interpersonal treatment, behaviour by authorities that fosters motive-based trust, giving duty holders a real voice in the process. It entails respectful treatment of duty holders, ethical behaviour and self-imposed limits on discretionary power (non-biased and consistent decision making), and demonstrating that regulated subjects are listened to and their arguments, issues, requests etc. carefully considered. When procedural justice is high, the legitimacy of authorities increases, and with it the legitimacy of the rules they edict and the decisions they take – and with increased legitimacy comes increased compliance (see Tyler, 2003). In addition procedural justice, and the legitimacy it fosters, are long-term drivers of compliance, and largely self-sustaining. They do not require an increase in resources – but a change in behaviours and approaches, in how authority is exercised, which may be very significant.

It is essential to design an approach to regulatory inspections and enforcement that finds the right balance between achieving the needed level of dissuasion, and fostering procedural justice. Repeated inspection visits, even handled in the most respectful and fair way possible, will still produce a feeling of accumulated burden which will reduce the feeling of procedural justice (one tends to feel unfairly treated when control is too frequent). This negative effect on compliance gets far worse when enforcement methods are not optimal in terms of behaviour, but feature abusive discretion, lack of transparency, disrespectful treatment, refusal to hear the duty holder’s views or take them into account etc. Unfortunately, “oppressive enforcement and harassment” are quite frequent in regulatory inspection and enforcement practices, and this is a major factor in the failure of regulations to produce their desired effects, because of resistance by regulated subjects leading to low compliance. An optimal system should strike the right balance to fit all the different categories of regulated subjects – the majority which tend to comply voluntarily if the preconditions for compliance exist (legitimacy in particular, as well as knowledge, and regulations that are realistically within their means in terms of complexity and costs, investment etc.), as well as a minority which tend to be “rational calculators” (see Voermans, 2014; Elffers, 1997). For them, an element of dissuasion is essential to make them the “right” choice – and this dissuasion will also ensure the majority of “voluntary compliers” that there is a “level playing field” – but this dissuasion should not become so burdensome that it alienates the majority.

Best practice principles and fundamental elements for reform

Inspections and enforcement apply across a variety of regulatory fields: technical safety inspections (themselves quite diverse: food hygiene, environment, OSH, etc.), revenue inspections (taxes and customs), and often a number of other regulatory compliance checks (on employment law, state language, gambling, currency regulations etc.). Institutions conducting inspections range from small specialised outfits with a few staff, to major structures with dozens of thousands of employees (in particular tax inspectorates). Institutions, their status, governance etc. are likewise diverse. On the other hand, there is a considerable level of agreement on what good practices for inspections are, and on how to conduct reforms to improve existing regimes.

-

Evidence-based enforcement. Regulatory enforcement and inspections should be evidence-based and measurement-based: deciding what to inspect and how should be grounded on data and evidence, and results should be evaluated regularly.

-

Selectivity. Promoting compliance and enforcing rules should be left to market forces, private sector and civil society actions wherever possible: inspections and enforcement cannot be everywhere and address everything, and there are many other ways to achieve regulations’ objectives.

-

Risk focus and proportionality. Enforcement needs to be risk-based and proportionate: the frequency of inspections and the resources employed should be proportional to the level of risk and enforcement actions should be aiming at reducing the actual risk posed by infractions.

-

Responsive regulation. Enforcement should be based on “responsive regulation” principles: inspection enforcement actions should be modulated depending on the profile and behaviour of specific businesses.

-

Long term vision. Governments should adopt policies on regulatory enforcement and inspections: clear objectives should be set and institutional mechanisms set up with clear objectives and a long-term road-map.

-

Co-ordination and consolidation. Inspection functions should be co-ordinated and, where needed, consolidated: less duplication and overlaps will ensure better use of public resources, minimise burden on regulated subjects, and maximise effectiveness.

-

Transparent governance. Governance structures and human resources policies for regulatory enforcement should support transparency, professionalism, and results-oriented management. Execution of regulatory enforcement should be independent from political influence, and compliance promotion efforts should be rewarded.

-

Information integration. Information and communication technologies should be used to maximise risk-focus, co-ordination and information-sharing – as well as optimal use of resources.

-

Clear and fair process. Governments should ensure clarity of rules and process for enforcement and inspections: coherent legislation to organise inspections and enforcement needs to be adopted and published, and clearly articulate rights and obligations of officials and of businesses.

-

Compliance promotion. Transparency and compliance should be promoted through the use of appropriate instruments such as guidance, toolkits and checklists.

-

Professionalism. Inspectors should be trained and managed to ensure professionalism, integrity, consistency and transparency: this requires substantial training focusing not only on technical but also on generic inspection skills, and official guidelines for inspectors to help ensure consistency and fairness.

The OECD has compiled, based on international experience, a list of eleven good-practice principles for inspections and enforcement: evidence-based enforcement, selectivity, risk focus and proportionality, responsive regulation, long term vision, co-ordination and consolidation, transparent governance, information integration, clear and fair process, compliance promotion, Professionalism (Box 8.5).

To implement these, the fundamental approaches on which reform should be based include:

-

Risk focus and risk proportionality: inspection resources and targeting should be based on the level of risk presented by activities/establishments – and enforcement responses should be proportional to the risks identified during inspection visits.

-

Co-ordination and consolidation: avoid duplication and overlaps in inspection mandates and missions – share information between different inspection fields

-

Better inspection methods: tools (like checklists), training, guidelines, etc. should all contribute to more transparency and predictability in enforcement decisions, as well as more risk proportionality and more attention to compliance promotion.

-

Compliance focus: all the work of inspectorates should be geared at improving compliance and public welfare outcomes – this means a major focus on information, outreach, guidance etc. – and a change in how inspectors interact with businesses.

-

Governance and performance management: institutional design and structures, management, internal processes and procedures, compensation, performance management etc. should all be aligned with reform objectives, compliance promotion goal, and contribute to transparency, effectiveness, efficiency etc.

Shared information systems for inspections: characteristics and benefits

Risk-based planning cannot be done without each agency having data on all objects under supervision, which is costly and difficult to update – while, at the same time, because many of the risk dimensions are correlated, and because a non-compliant business tends to be thus in several areas, inspectorate would be able to improve their risk analysis if they also had data from other inspectorates. In addition, many inspectorates (even in OECD countries) have been found not to have proper information systems in the sense of systems allowing them to plan their activities based on risk, and to record the inspections results – setting up a system for each of these separately, and “populating” each separately with data on all objects, is far more costly than setting up a joint system. All these points speak strongly for setting up as much as possible joint information systems shared by most or all inspectorates.

The information system should be built on a database that includes the following data:

-

List of all business entities and of all establishments (not only all companies/businesses, but also all separate premises) in the country.

-

For each establishment, have data on a set of relevant parameters corresponding to different risk factors, some “general” risk parameters generally relevant to all or most types of inspections (e.g. size, volumes handled, type of technology or process, etc.), and other more specific ones grouped by risk dimensions (e.g. food safety, workplace safety etc.).

-

List all inspections and their results.

-

Automatically generate risk ratings for each business and establishment.

-

Automatically generate inspections selection and schedule.

-

Filter and analyse data reporting.

More advanced systems can also incorporate functions to plan activities inside the inspectorate and manage processes, have online checklists, etc. (Blanc, 2012).

Best practice today dictates that various inspectorates should ideally co-ordinate their activities to ensure that all relevant risks are properly addressed during a joint inspection process. However, experience shows that inspections tend to be uncoordinated, unplanned and carried out in silos, regardless of industry or jurisdiction. Typically inspecting organisations do not share much information or regularly communicate Information technology has a key role in improving efficiency, transparency, and accountability in business inspections. A select number of jurisdictions have made efforts to implement inspection management solutions that are shared across multiple inspectorates, albeit with various levels of success. Online research and a series of in-depth interviews with government officials who participated in this study showed that a successful SIMS implementation yields:

-

Improved targeting through a better identification and follow up of risks.

-

Decreased administrative burden for businesses and entrepreneurs to comply with regulation.

-

Increased quality and effectiveness of inspections leading to improved regulatory compliance.

-

Improved internal efficiency and reduced administrative costs for governments.

-

Increased transparency of inspection operations for businesses and citizens leading to a decrease in corruption.

These benefits usually result from:

-

Gathering and consolidating more consistent and comprehensive information on enterprises subject to inspection.

-

Streamlining the inspection process to increase inspector efficiency.

-

Formalising policy and procedures to ensure consistency.

-

Automating and supporting decision-making to reduce subjectivity in operations and maximise the use of resources.

-

Sharing information across inspectorates to co-ordinate inspection scope, improve preparation and outcomes, as well as reduce the inspection burden of individual inspectorates.

-

Providing public access to relevant information leading to increased transparency and accountability.

Basic solutions incorporate information about businesses and entrepreneurs, their characteristics (e.g. locations, size, industry, etc.) and previous inspection results to allow for simple planning of future inspection activities. These systems typically provide a full inspection history by business and location and use a checklist to obtain consistency across inspections; however, there is typically very limited automation.

Intermediate solutions have functionality to trigger follow-up activities based on the outcome of an inspection and allow for automated integration of inspection practices across inspectorates. They are ideally integrated with government business registries or other sources of enterprise information.

Advanced solutions include a variety of other features and functions including:

-

Risk-based inspection planning, which allows for the scheduling and planning of inspections based on a risk assessment of the business that includes key information such as size of the business, previous inspection results, industry, geography, and data from other inspectorates or government information sources.

-

Automated or real-time integration with other information sources, which generally fall under two broad categories: i) registry information (e.g., business/ company registration information, licences and permits); and ii) risk information (e.g., business/company risk based on its activities and profile, results of inspections or reports from other inspectorates).

-

Comprehensive mobile inspection capabilities, including tools and technologies that give inspectors the ability to view schedules and inspection records as well as record inspection results while onsite.

-

Performance management capabilities enabled through business analytics, which are aligned with risk-based planning and provides capabilities for inspectorates to monitor the efficiency and output of their inspection programme and individual inspectors.

-

Public portal capabilities involves, providing access to businesses and the general public to view inspection requirements and results, submit complaints, and appeal an inspection (Wille and Blanc, 2013).

Bibliography

Ayres, I. and J. Braithwaite (1992), Responsive regulation: transcending the Deregulation debate, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Blanc, F. (2012), “Reforming Inspections: Why, How and to What Effect?”, OECD, Paris.

Braithwaite, J. (2011), “The essence of responsive regulation”, UBC Law Review, Vol. 44/3, pp. 475-520.

Gunningham, N. (2010), “Enforcement and Compliance Strategies”, in The Oxford Handbook of Regulation, Baldwin, R., M. Cave and M. Lodge (eds.), Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 120-145.

Hampton, P. (2005), “Reducing administrative burdens: effective inspection and enforcement”, HM Treasury, London, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090609003228/http://www.berr.gov.uk/files/file22988.pdf.

Hawkins, K. (ed.) (1992), The Uses of Discretion, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Kirchler, E. (2007), The Economic Psychology of Tax Behaviour, Cambridge University Press.

Löfstedt, R.E. (2011), “Reclaiming health and safety for all: An independent review of health and safety legislation”, presented to the UK Parliament in 2011.

Macrory, R. (2006), “Regulatory Justice: Making Sanctions Effective”, final Report, Better Regulation Executive, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills of the United Kingdom, London, November, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121212135622/http://www.bis.gov.uk/files/file44593.pdf.

OECD (2014), Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208117-en.

Ogus, A. (1994), Regulation: legal form and economic theory, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Scholz, J.T. (1994), “Managing Regulatory Enforcement in the United States”, in Handbook of Regulation and Administrative Law, Rosenbloom, D.H. and R.D. Schwartz (eds.), Marcel Dekker, New York, pp. 423-466.

Sparrow, M. (2008), The character of harms: operational challenges in control, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Tyler, T.R. (2003), “Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law”, Crime and Justice, Vol. 30, pp. 283-357.

Tyler, T.R. (1990), “Why People Obey the Law”, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Voermans W. (2014), “Motive-Based Enforcement”, in Mader, L. and S. Kabyshev (eds.), Regulatory Reforms; Implementation and Compliance, Proceedings of the Tenth Congress of the International Association of Legislation (IAL) in Veliky Novgorod, 28-29 June 2012, Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 41-61.

Wille, J. and F. Blanc (2013), “Implementing a shared inspection management system: insights from recent international experience”, Technical Guidance for Reform Implementation, Nuts & bolts, Washington, D.C, World Bank Group, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/04/20217202/implementing-shared-inspection-management-system-insights-recent-international-experience.

The 2015 Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) present up-to-date evidence of OECD member countries’ and the European Commission’s regulatory policy and governance practices advocated in the 2012 Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance. They cover in detail three principles of the 2012 Recommendation: stakeholder engagement, Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) and ex post evaluation, and provide a baseline measurement to track countries’ progress over time and identify areas for reform. The Indicators present information for all 34 OECD member countries and the European Commission as of 31 December 2014.

The 2015 Indicators draw upon responses to the 2014 Regulatory Indicators survey. Answers were provided by delegates to RPC and central government officials. Compared to previous surveys, the 2014 survey puts a stronger focus on evidence and examples to support country responses, as well as on insights into how different countries approach similar regulatory policy requirements. The survey questionnaire has been developed in close co-operation with RPC delegates and members of the OECD Steering Group on Measuring Regulatory Performance. Survey answers underwent a verification process carried out by the OECD Secretariat in co-operation with delegates to the RPC in order to enhance data quality and ensure comparability of answers across countries and over time.

The survey focuses on RIA and stakeholder engagement processes for developing regulations (both primary laws and subordinate regulations) that are carried out by the executive branch of the national government and that apply to all policy areas. Questions regarding ex post evaluation cover all national regulations regardless of whether they were initiated by parliament or the executive. Based on available information, most national regulations are covered by survey answers, with some variation across countries. Most countries in the sample have parliamentary systems. The majority of their national primary laws therefore largely originate from initiatives of the executive. This is not the case, however, for the United States where no primary laws are initiated by the executive, or, to a lesser extent, for Mexico and Korea where the share of primary laws initiated by the executive is low compared to other OECD member countries (4% over the period 2009-2012 and 30% in 2013 in Mexico and 16% in Korea over the period 2011-13).

Based on the information collected through the 2014 survey, the OECD has constructed three composite indicators on RIA, stakeholder engagement for developing regulations, and ex post evaluation of regulations in order to help present the information collected in an easily expressible format. Each composite indicator is composed of four equally weighted categories: systematic adoption, methodology, transparency, and oversight and quality control.

While composite indicators are useful in their ability to integrate large amounts of information into an easily understood format (Freudenberg, 2003), they cannot be context specific and cannot fully capture the complex realities of the quality, use and impact of regulatory policy. In-depth OECD country peer reviews are therefore required to complement the indicators and provide readers with an in-depth assessment of the quality of a country’s regulatory policy, taking into account the specific governance structures, administrative cultures and institutional and constitutional settings to provide context-specific recommendations. Moreover, the results of the iREG indicators, as those of all composite indicators, are sensitive to methodological choices. It is therefore not advisable to make statements about the relative performance of countries with similar scores. Please note that while the implementation of the measures assessed by the indicators aim to deliver better regulations, the indicators should not be interpreted as a measurement of the quality of regulation itself.

All underlying data and scores for the composite indicators are available at www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/indicators-regulatory-policy-and-governance.htm.

Further information on the indicator design and methodology, as well as the full list of survey questions covered by the indicators can be found in: Arndt, C. et al. (2015), “2015 Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance: Design, Methodology and Key Results”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris. Results and first analysis of the indicators are available in the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015.

Source: www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/indicators-regulatory-policy-and-governance.htm.

Notes

← 1. http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO1603.

← 2. www.pisrs.si/pis.web/pregledpredpisa?id=zako3209.

← 3. www.id.gov.si/fileadmin/id.gov.si/pageuploads/splosno/letna_porocila/lp_irsd_2015_www.pdf.

← 4. www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO3209.

← 5. www.mju.gov.si/fileadmin/mju.gov.si/pageuploads/javna_uprava/sous/mnenja/letno_porocilo_inspekcijskega_sveta_za_leto_2015.pdf.

← 6. See for instance, successive survey reports published by the IFC in Ukraine, Tajikistan etc.: www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/regprojects_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/tjbee_home/overview/survey/ and www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/regprojects_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/uspp_home/projectmaterials/pmsurveys/.