Chapter 1. The legal and institutional framework of the public procurement function in Nuevo León

This chapter describes the governance structure of the procurement function of the State Government of Nuevo León, which is currently undergoing a process of centralisation. The chapter analyses the potential benefits and risks of a centralised purchasing arrangement, as well as the role of a procurement strategy and business model in advancing value-for-money. In addition, this chapter discusses the regulatory framework applicable not only to the acquisition of goods and services, but also to the development of public works. Finally, the chapter describes the process of procurement planning followed by central ministries of the state government, and the extent to which public procurement processes are linked to budgeting and public financial management.

1.1. Procurement structure and governance

As of February 2017, the public administration of the state of Nuevo León (APE) included 329 administrative units of the centralised administration (i.e., ministries, deputy ministries and directorates). The parastatal sector comprised 71 entities, including decentralised public bodies, decentralised public bodies with citizen participation, enterprises with state participation and public funds (fideicomisos públicos).

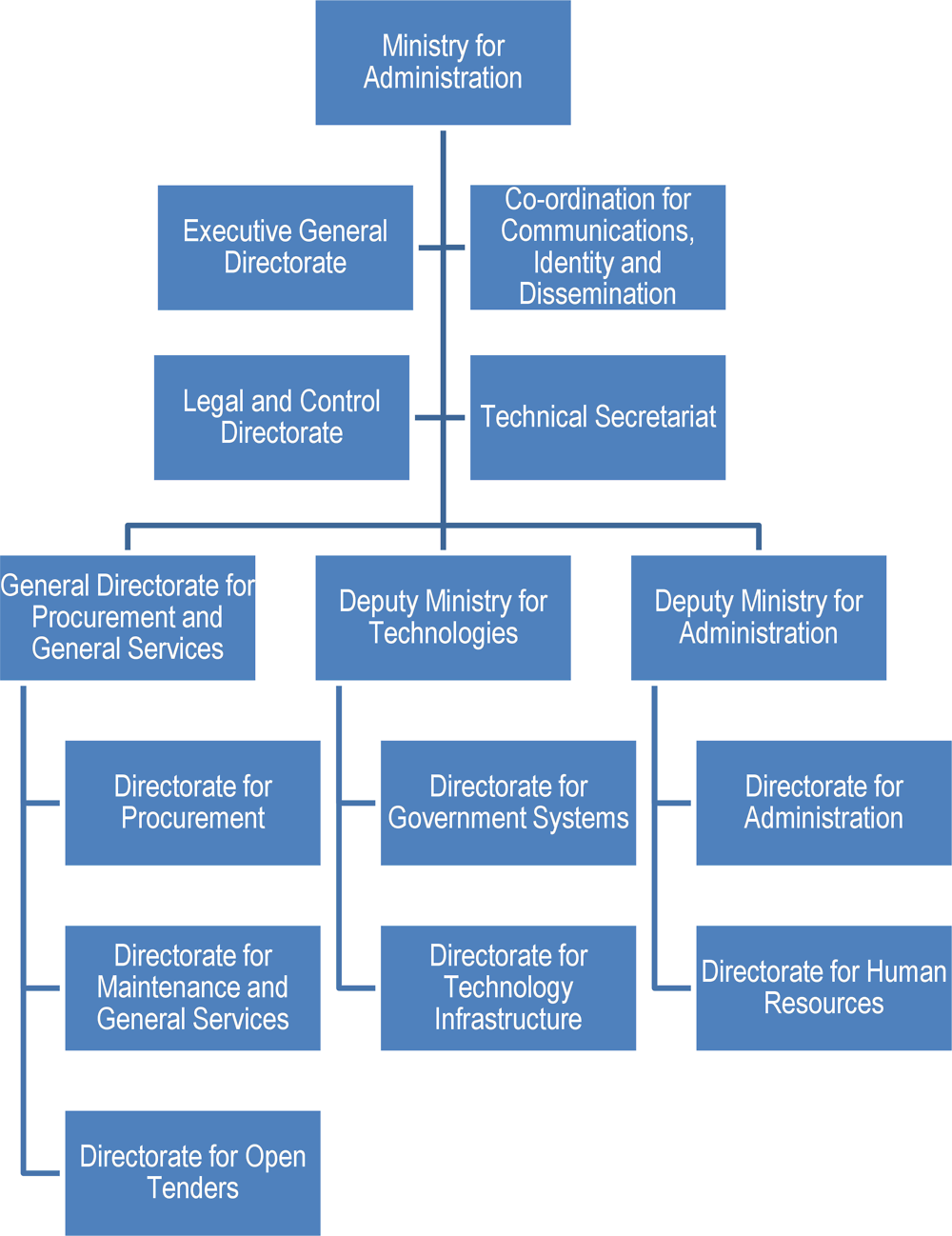

The current administration, elected for the 2015-2021 term, is reorganising the structure of the government, according to an amendment to the Organisational Law of the Public Administration of the State of Nuevo León (Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública para el Estado de Nuevo León, LOAPENL), passed in April 2016. This amendment establishes the separation of the Undersecretariat of Administration from the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury (Secretaría de Finanzas y Tesorería General del Estado) to create a new Secretariat of Administration (Secretaría de Administración, SA). In principle, the SA will gradually absorb the administrative personnel, including procurement staff, from the central administration and parastatal entities. The State Attorney General’s Office (PGJE), the State Secretariat of Public Security (SSPE), and the Office of the Comptroller for Government Transparency (Contraloría y Transparencia Gubernamental, CTG) are notable exceptions.1 The SA is structured according to the organisational chart in Figure 1.1.

Source: (Secretariat of Administration, 2016[1]).

For all practical purposes, the SA represents the Central Purchasing Body (UCC) of the State Government of Nuevo León (SGNL). The SA has the following procurement-related powers (State Government of Nuevo León, 2017[2]):

-

monitoring compliance with the laws and regulations applicable to material resources and services, and supervising and ensuring that ministries and entities comply with their powers related to these matters

-

monitoring compliance with the normative framework applicable to procurement of goods and services of the state government, and presiding over the Procurement Committee

-

assisting ministries and entities in the planning of the procurement of goods and services

-

programming and formalising the contracts by which goods, services and information systems are purchased for the APE to fulfil its objectives

-

managing the registry of suppliers of goods and services for the APE

-

representing the state in the legal procedures related to the procurement of goods and services

-

suing individuals involved in criminal activities affecting the procurement of goods and services of the state government.

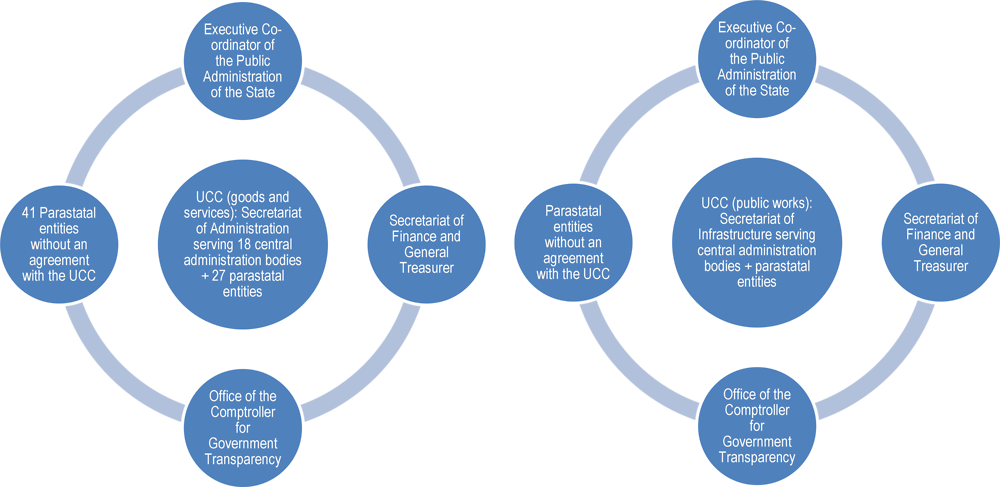

As of September 2017, the SA managed the procurement of goods and services for 18 central administration bodies. In addition, as of this date, 27 parastatal entities signed an agreement with the SA that guaranteed its support for their procurement activities, once these entities made a requisition and allocated the corresponding budgets.

A similar process of centralisation is taking place for public works, only it is being managed by the Secretariat of Infrastructure (INFRA). INFRA is in charge of planning and building the public works administered by the APE.

Other ministries with important roles related to the procurement of goods and services include the following:

-

Executive Co-ordinator of the APE: Suggests public policies and evaluates their results, proposes the organisation of the government, co-ordinates the fiscal programme, organises cabinet meetings, fosters citizen participation mechanisms and links state government institutions with civil society.

-

Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury: Establishes financial and income administration policies to make revenue collection more efficient and optimise expenditures, following equity and transparency principles. For procurement purposes, it allocates the procurement budget and processes and makes payments to suppliers.

-

Office of the Comptroller for Government Transparency (CTG): Plans, organises, and co-ordinates control systems, and fosters the modernisation of the APE. The CTG also supervises expenditures, and carries out inspections, reviews, audits, and surveillance actions. It co-ordinates attention to complaints, challenges, claims and suggestions, and applies sanctions. It provides the necessary support, so that any individual may have access to public information. The CTG supervises and ensures that the supply of public services follows principles of legality, efficiency, honesty, transparency and impartiality. Finally, the CTG fosters a culture of transparency and service quality, and upholds the ethical values that public servants should follow.

In addition to the set up described above, there are 51 municipalities in the state of Nuevo León, which make their own decisions concerning contracts for the purchase of goods and services. However, when such procurement activities involve federal or state transfers, the Superior Audit Office of the State of Nuevo León (Auditoría Superior del Estado de Nuevo León, ASENL) and other control entities from the federal level intervene to control and oversee the use of the resources.

1.2. The normative framework for procurement in Nuevo León

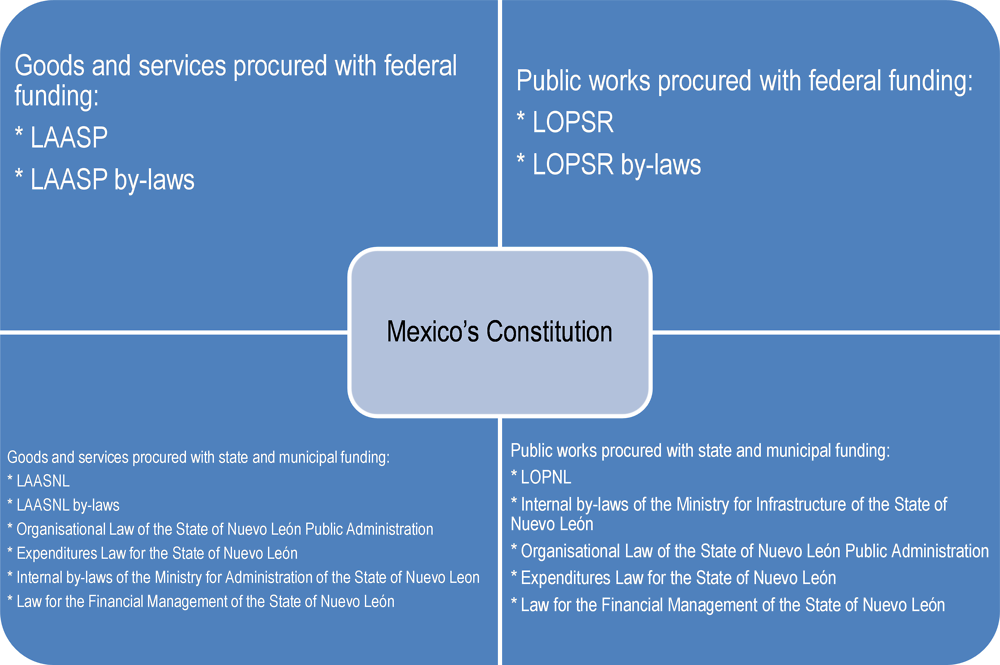

There are six basic procurement modalities in Nuevo León, each one subject to different rules and regulations. When federal resources are applied – no matter the amount of either goods and services or public works – the federal regulations prevail. When only state or municipal resources are applied, the state regulations are to be observed. Table 1.1 illustrates this classification.

Article 134 of Mexico’s Constitution (Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, CPEUM), establishes the principle that the procurement of goods and services should be carried out through public tenders in order to achieve the best terms with regards to price, quantity, financing arrangements and convenience. The principles set out in the CPEUM are then detailed in a set of normative instruments, applicable for procurement financed through federal or state funding.

Procurement of goods and services with federal funding is subject to the Law for Acquisitions, Leasing and Services of the Public Sector (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público, LAASP), and its By-Laws (Reglamento de la Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público). Public works financed through federal funding are subject to the Law for Public Works and Related Services (Ley de Obras Públicas y Servicios Relacionados con las Mismas, LOPSR), and its By-Laws (Reglamento de la Ley de Obras Públicas y Servicios Relacionados con las Mismas).2

In contrast, procurement of goods and services with state and municipal funds is regulated by the Law for Acquisitions, Leasing and Procurement of Services for the State of Nuevo León (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Contratación de Servicios del Estado de Nuevo León, LAASNL), and its By-Laws (Reglamento de la Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Contratación de Servicios del Estado de Nuevo León). Some other laws that apply to this procurement regime include the following3:

-

Organisational Law of the Public Administration of the State of Nuevo León: Organises and regulates the functioning of the public administration of the state, including central and parastatal entities. Among other things, this law establishes the procurement-related powers of the SA.

-

Expenditures Law for the State of Nuevo León (Ley de Egresos del Estado de Nuevo León): Issued every year to regulate the allocation, execution, control and evaluation of public expenditures.

-

Internal By-Laws of the Secretariat of Administration of the State of Nuevo León (Reglamento Interior de la Secretaría de Administración para el Estado de Nuevo León): Establishes the organisational structure of the SA and the powers of its administrative units.

-

Internal By-Laws of the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury (Reglamento Interior de la Secretaría de Finanzas y Tesorería General del Estado): Establishes the organisational structure of the secretariat and the powers of its administrative units.

-

Law for the Financial Management of the State of Nuevo León (Ley de Administración Financiera para el Estado de Nuevo León): Regulates the management of the public finances of the state, establishing the basis for financial planning of the central and parastatal entities.

Finally, procurement of public works with state and municipal funds is subject to the Law of Public Works for the State and Municipalities of Nuevo León (Ley de Obras Públicas para el Estado y Municipios de Nuevo León, LOPNL).

1.3. Centralisation, co-ordination and communication

The European Parliament and Council (European Parliament and Council, 2014[3]) defines a central purchasing body as a contracting authority that:

-

acquires goods or services intended for one or more contracting authorities

-

awards public contracts for works, goods or services intended for one or more contracting authorities

-

arranges framework agreements for works, goods or services intended for one or more contracting authorities.

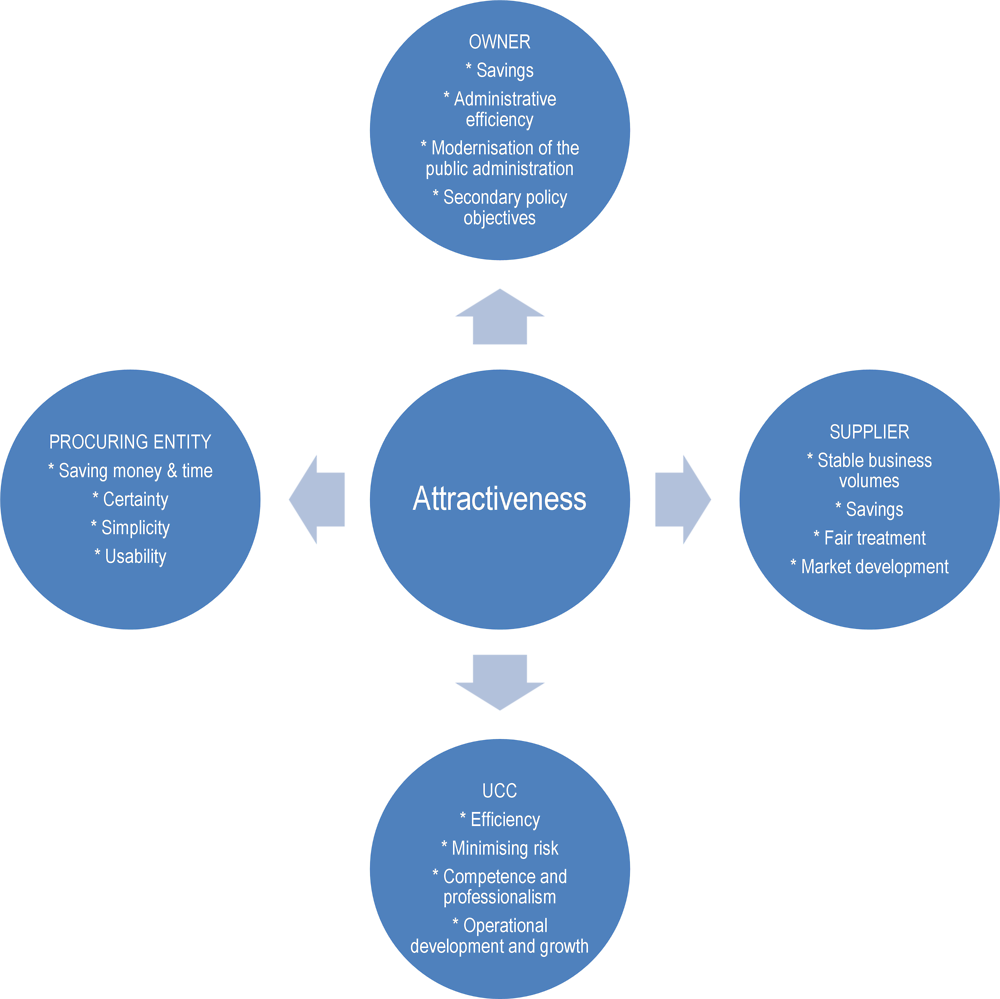

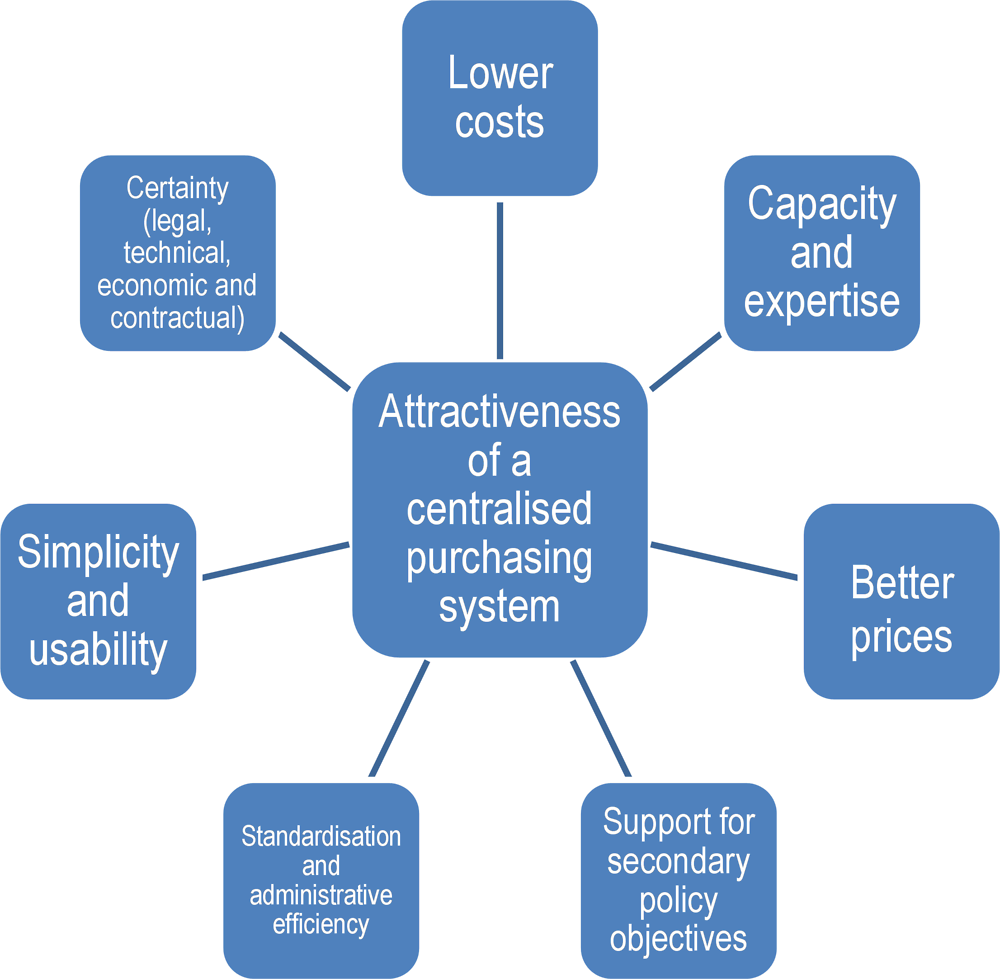

Centralised purchasing is not a new concept, and it is not a practice that is exclusive to the public sector (see Box 1.1). The rationale for a centralised purchasing system should be examined from the perspective of different stakeholders. These stakeholders include: the users of the UCC’s services, such as the procuring entities; the suppliers; and the owner of the UCC, which is usually a ministry or some other public body representing the interests of taxpayers (see Figure 1.4). The main arguments for establishing a UCC are typically the following (OECD, 2011[4]):

-

Efficiency and better prices: Centralised procurement, based on the aggregation of purchasing needs of the UCC’s customers, provides attractive business opportunities for the private sector. With larger procurement volumes, increasing competition usually follows, driving prices down and leading to more favourable terms for the purchaser. In other words, the potentially large sales volumes that can be expected under centralised procurement mean that economies of scale can be exploited by economic operators. It makes a huge difference for a supplier to produce and deliver large lots under large volume contracts to a small number of customers. This arrangement is preferable to a situation where the supplier has to serve a large number of customers with many small orders, even when the total contract volume is equal.

-

Reduced transaction costs in terms of time, expenditures and management of the procurement process, from the first stage of planning and defining needs up to the final stages of contract management, payment and closing files.

-

The need for standardisation or increased administrative efficiency within the government administration.

-

Procuring entities may lack sufficient capacity to prepare and carry out complex tenders for purchases requiring product or market expertise.

-

Professional, centralised purchasing provides certainty to procuring entities with regards to many aspects (e.g., legal, technical, economic and contractual issues). This reduces risks that otherwise would have to be borne by procuring entities. These risks include challenges and complaints, poor quality of products, failure of suppliers and inadequate contractual terms and management.

-

Simplicity in terms of the process to purchase goods and services, as well as the use of innovative tools, like framework agreements.

-

The use of UCCs facilitates the execution of secondary policy objectives, such as the participation of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in public procurement, and the promotion of innovation and productive chains. UCCs can also make it easier for the government to transition to green procurement.

Central purchasing is not exclusive to the public sector. It is widely used in the private sector, both in manufacturing and retailing, among other sectors. The main objective of central purchasing is to reduce purchase prices and purchasing costs in all phases of production and distribution. Most larger companies have central purchasing departments specialising in securing a reliable supply of inputs on favourable terms.

Centralised procurement in the public sector is not new either. Denmark created a UCC for the state in 1976. Since the 1970s, Sweden has relied on a system that co-ordinates central framework agreements with simple procedures, mainly designed for procuring entities within the central government. This system was originally built around 10-15 government agencies, each of which was given the responsibility for a particular product or service area. The system tried to match the product or service area with an agency that had its own large need for the same goods or services.

France also has a long history of centralised public procurement. In 1949, the Ministry of Education established a central purchasing unit for goods and school furniture. In 1968, this entity was named the Association of Public Purchasing Groups (Union des Groupements d’Achats Publics, UGAP).

Hungary, Italy and the United Kingdom (UK) have a more recent history of centralised procurement units. Consip, the central purchasing body in Italy, was established in 1997. It was given the responsibility of running the new Programme to Rationalise Public Spending on Goods and Services in 2000. In Hungary, KSzF was established in 1995. It was given the task of setting up a system for the centralisation of the procurement of certain goods and services. In the UK in the late 1990s, the government took a more co-ordinated approach to the area of public procurement, first with the creation of OGC and then with the creation of its operative branch, Buying Solutions.

Source: (OECD, 2011[4]).

Source: (OECD, 2011[4]).

Notwithstanding the potential advantages mentioned above, centralised procurement also entails risks, such as the following:

-

Market concentration and development of monopolistic structures: The large volumes implied by centralised procurement tend to favour large, established suppliers over small or new ones. This may hinder competition and market entry, deteriorating the terms of sourcing. Currently, many OECD countries have an explicit policy that mandates that procuring entities take measures to facilitate the participation of SMEs in public tenders. UCCs may implement specific strategies (i.e., dividing large contracts into smaller lots) to attract SMEs. Smaller companies may also be subcontracted or participate in consortia.

-

Commercial risks: A UCC can procure goods or services that do not meet the requirements of the procuring entities. In this case, the procuring entity may not want to go through with the purchase. This risk is bigger when products are not homogeneous and when substitutes exist. Highly standardised requirements by UCCs may not be suitable or acceptable for procuring entities. Therefore, robust co-ordination between UCCs and procuring entities is needed to satisfy all the potential users of UCC services.

-

Responsiveness: If not provided with the right level of expertise and resources, UCCs may be slow to respond to changes in markets, potentially neglecting important developments in prices and technologies. This situation is particularly problematic when the use of the UCC is mandatory. It is less troublesome, however, when using the UCC is voluntary.

In order to successfully implement a centralised purchasing system, it is critical to be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches. Some of the questions to answer when establishing centralised purchasing arrangements are the following (OECD, 2011[4]):

-

What kind of business and organisational model can be used for a UCC?

-

What goods and services are going to be purchased through the UCC?

-

How are the operations of the UCC going to be financed?

-

Will the use of the UCC services be voluntary or mandatory for procuring entities?

1.3.1. Business and organisational models for a UCC

There are different ways to design the business model for centralised procurement. Under the “monopoly” model, a central government establishes a central purchasing office to make bulk purchases directly from suppliers. Government ministries and agencies are required to buy goods and services through these central purchasing offices, which have a wholesaling and often also a warehousing function.

Some countries have opted for more decentralised and flexible approaches. In these cases, UCCs still exist, but their legal status changes. In many cases, this means that they are given more financial and managerial autonomy. On top of this, the buyers (ministries and government agencies) are given more freedom to buy goods and services from other sources when the alternative results in better value for money.

Another approach is the use of specialised procurement agencies. Such an agency may specialise in the provision of specific goods or services (e.g., IT products and medical supplies). It may also offer better contracts in terms of price, quality and delivery conditions than a small, non-specialised unit.

Centralised purchasing of certain goods and services is likely to benefit mostly small and medium-sized procuring entities. Large procuring entities, such as ministries or large government agencies, often have sufficient procurement competence and sufficiently large purchase volumes to reap most of the gains that a centralised purchasing system can produce. This is not the case of many small or medium-sized procuring entities. One implication of this is that a government consisting of many small procuring entities may have more to gain from establishing a centralised purchasing system than a government with mostly large procuring entities.

Concerning legal status, UCCs may take the form of publicly owned limited companies or public bodies with considerable autonomy. Unlike private limited companies, the objective of these public UCCs is not to maximise profits. Instead, they are non-profit companies. UCCs are better suited to this organisational form mainly because it provides them with flexibility and a certain degree of freedom. UCCs are less dynamic when they are part of a government administration, are operated within a ministry or as an independent agency. There is some debate on this matter. Some argue that it is also easier for non-profit corporations to attract competent and specialised staff. In addition, they argue that non-profit UCCs are able to focus solely on creating value for their customers, without taking unnecessary political considerations into account. Others argue that because the limited company form is ultimately an organisational model that is meant to be used for profit-seeking firms, it is not ideal for UCCs. Since UCCs do not have the objective of maximising profits, but instead endeavour to create savings for the public sector, limited companies are not the ideal organisational form. Instead, according to this argument, a UCC is best organised as a government agency or a division within a ministry.

The instruments for establishing and regulating the operations of UCCs also differ between countries. Not only are the instruments themselves different, but the mandates given to UCCs by owners vary in many key respects. The operations of UCCs are usually regulated by: a country’s budget law or its equivalent; a government decree; a public procurement act, or its equivalent; or a state procurement strategy. Denmark’s SKI, for example, is not regulated by a legal instrument. Its establishment, responsibilities and functions are governed by the owners’ agreement establishing the company. It is a publicly owned company that operates under private law.4

In summary, UCCs operate under very different mandates. It is likely that these differences originate in the variations between countries in terms of legal and administrative structures, traditions and cultures. The operations of Consip (Italy) and KSzF (Hungary), for example, are regulated in detail. In contrast, the UCCs in Nordic countries are given more freedom to plan and manage their operations.

A typical organisational chart of a UCC contains the following main functions (OECD, 2011[4]):

-

UCC management

-

product and category management

-

customer and client market management

-

procurement and contracting

-

information technology (IT) systems development

-

legal services

-

financing and accounting.

The department of procurement plays an important role. It is usually divided into several divisions specialising in procurement of information and communication technologies (ICTs) or administrative services, for example. Marketing, customer relations and service to public entities is particularly relevant for voluntary arrangements. Additionally, all UCCs have departments of human resources, finance and administrative support. The IT function is also particularly relevant where all transactions are to be carried out through an e-procurement portal.

National governments are not alone in using centralised purchasing; regional and local governments also practice it. In the latter case, a regional authority creates a central purchasing office to serve ministries and internal entities with procurement services and expertise. Collaborative purchasing arrangements between municipalities in a specific geographic area are not unusual in OECD countries. This is particularly true for goods and services that are in demand in virtually all municipalities, such as fuel and office supplies.

1.3.2. Goods and services to be purchased through the UCC

Goods and services commonly purchased through UCCs are to be of common interest to and should be purchased frequently throughout the public administration, according to the common-interest principle. These goods and services may include: ICT products and services (computers, photocopiers, printers, servers, software); telecommunications products (networks, mobile phones, landline phones); office furniture; travel services; office equipment and supplies; vehicle and transport services; fuel; food; and organisational and human resources development services (OECD, 2011[4]).

Many of the products and services frequently procured through UCCs are considered technically straightforward or standardised. That said, some products and services are highly technical and commercially complex, such as advanced ICT systems. Indeed, UCCs may cover both standardised products and services of non-strategic relevance, and products and services that have a strategic nature.

1.3.3. Financing arrangements for a UCC

A UCC can be financed in several ways. The first alternative is to finance the UCC directly from the government budget, as for ordinary government agencies, which usually receive a lump sum every year that is intended to cover their costs. Another funding possibility is to have service fees. These fees may be levied either on the various government entities that use the services provided by the UCC or on the suppliers to the UCC. The UCC may charge a percentage (usually in the range of 0.6-2.0%) of the suppliers’ invoiced turnover. In Hungary and in the case of UGAP (France), for example, the fee is paid by the buyers. In Sweden, Finland, Denmark and the UK, it is paid by the suppliers. The main advantage of user fees is that they provide an incentive for the UCC (i.e., no sales, no revenues). In the cases of Consip (Italy) and SAE (France), these UCCs are financed directly from the government budget.

Proponents of user charges argue that UCCs usually do not make large profits. In this case, user charges are set with the aim of breaking even. Fees are set so that revenues cover costs, including necessary investments. On the other hand, proponents of the public budget model argue that it eliminates the profit risk and provides better incentives for cost-efficiency. Those who do not like this model argue that it removes the incentive to find the most attractive product areas. Moreover, it runs the risk of under-investment in new technology due to the possibility of insufficient public funds.

1.3.4. Voluntary or mandatory scope of a UCC

The extent to which it is compulsory for procuring entities to use the services offered by the UCCs differs significantly among OECD countries. In Italy and Hungary, for example, it is mandatory for central government institutions to rely on the UCC, while for sub-national public-sector entities it is voluntary. Sweden has a semi-compulsory system in which it is possible for procuring entities to purchase from alternative sources if the products offered by the UCC do not meet their needs or if better terms can be obtained elsewhere.

There are advantages and disadvantages to compulsory and voluntary arrangements. In a compulsory system where procuring entities are obliged to rely on the UCC, responsibility for the overall quality of procurement rests with the UCC. This is true whether the quality of a good or service is considered positively or negatively by the procuring entities. Call-off contracts leading to poor supplier performance, inadequate product quality and incorrect prices emanating from poorly designed and awarded agreements by the UCC may lead to serious dissatisfaction among procuring entities. In a voluntary system, the procuring entities can always refrain from using the UCC if it is not considered to be sufficiently usable. Hence, the attractiveness of a UCC is dependent on the extent to which it will satisfy the individual needs of the procuring entities.

Proponents of a system where procuring entities are forced to use the UCC´s services argue that this ensures cost-efficient public sourcing and increases standardisation among authorities. Such a system may further improve tender prices and terms, and would make it easier for the UCC to estimate the expected demand. The terms of this type of system would also create a greater degree of certainty for potential suppliers regarding actual sales. Both of these factors are likely to strengthen competition and produce better prices and other terms. Others argue that such a requirement weakens the incentive of UCCs to be user-friendly and creates the risk of monopolistic behaviour. Indeed, one of the benefits of having a voluntary system is that it provides an incentive for UCCs to offer attractive services on competitive terms. If UCCs fail to do so, there will be no demand for their services; in this case their own existence will be at risk. This is especially true if the revenue of the UCC is tied to the extent to which its services are used by procuring entities. Finally, proponents of a voluntary system argue that it provides better opportunities to properly reflect customer satisfaction with UCC services.

1.3.5. The centralisation process in Nuevo León

As mentioned before, the SGNL is in a process of centralising procurement activities for goods and services in the SA. The tasks in the different stages of the procurement cycle are distributed as shown in the following table.

Regarding the procurement process itself, robust co-ordination is required in the different stages of the procurement cycle. This co-ordination should occur between the different directorates of the General Directorate for Procurement and General Services of the SA, requesting units (from the central or parastatal administration) and the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury. Then, at the policy, planning, control and evaluation levels, the Executive Co-ordinator of the APE and the CTG play an important role. Furthermore, the ASENL plays the role of the external auditor, accountable to the state legislature.

One of the mechanisms to ensure co-ordination at the process level is the Procurement Committee of the APE, which is regulated in the LAASNL and its By-Laws. The members of this committee are listed below.

Participation and voting capacity:

-

Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury;

-

Secretariat for Economic Development;

-

Secretariat of Infrastructure;

-

Office of the State Attorney.

Participation capacity only:

-

CTG;

-

Requesting unit.

The LAASNL establishes that the member of the committee from the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury presides over the committee and breaks a tie. That said, it is the SA, through the Director for Open Tenders, that leads the committee. This was codified by an amendment to the LOAPENL that was passed in April 2016. The amendment transferred the procurement function from the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury to the SA. Even though the LAASNL establishes that the SA will play the role of the Technical Secretariat of the Committee, this regulation still needs to be updated to align with the latest reforms to the Organisational Law of the APE, which established the role of the SA as the UCC.

According to Article 16 of the LAASNL, the Procurement Committee of the APE performs the following functions, among others:

-

examining the annual procurement programme and the annual or multiyear budget for the procurement of goods, leasing and services, as well as any modification to it

-

participating in open tenders and restricted invitation processes, as well as in clarification meetings, events to present and open bids, and in the awarding of contracts

-

issuing an assessment of the bids in open tenders and restricted invitation procedures

-

assessing the cases of exceptions to open tenders

-

proposing rules, criteria and guidelines for the procurement of goods and services.

Besides the Procurement Committee of the APE, there are other committees for entities of the APE which have not signed a co-ordination agreement for the SA to take over their procurement activities. Such committees have the membership listed below.

Participation and voting capacity:

-

Procuring entity, which presides over the committee.

-

Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury. (Given the amendment to the LOAPENL in April 2016, the SA assumes this seat).

-

The lawyer of the procuring entity.

Participation capacity only:

-

CTG.

-

Requesting unit from the procuring entity.

On the side of public works, Article 99 of the LOPNL establishes the Committee for the Award of Public Works Tenders (Comité de Apoyo para la Adjudicación y Fallo de los Concursos de Obra Pública). This committee issues opinions about the awards of public works contracts from open tenders, restricted invitations and direct awards. It also serves as a control mechanism for issues of compliance with the public works legislation. Although the committee’s decisions are not mandatory, public officials tend to follow them to avoid potential sanctions for misinterpreting the law. Its members include the following:

-

Co-ordinator: The Secretary of Infrastructure, who breaks a tie, if necessary.

-

Secretariat: A public official from the Secretariat of Infrastructure, appointed by the Secretary. The Secretariat of this committee participates in proceedings, but has no voting rights.

-

Member: Secretariat of the Interior.

-

Member: Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury.

-

Member: Secretariat of Social Development.

-

Observer: CTG, with participation, but no voting rights.

-

A representative from the corresponding chamber, depending on the kind of works, associations, professional boards or citizens linked to public works. This representative participates in the proceedings, but has no voting rights.

1.4. Procurement planning

Planning for the procurement of goods and services should be a strategic endeavour. Procurement planning should align with the objectives set forth by the State Development Plan (Plan Estatal de Desarrollo), the Strategic Plan for the State of Nuevo León 2015-2030 and other sectoral, regional and special plans, as applicable to each ministry and agency of the APE. In addition, procurement planning should take into account the resources established in the state’s expenditures budget.

Each ministry and the parastatal entity that has an agreement with the SA should produce their Annual Programmes for Procurement, Leasing and Services (Programas Anuales de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios, PAA), bearing in mind the budget allocations indicated in the Electronic Integrated Government Resources System (Sistema Integrador de Recursos Electrónicos Gubernamentables, SIREGOB). PAAs are sent to the SA in January of every year. The SA then compiles a state government-wide programme, which is published by the Electronic System for Public Procurement (Sistema Electrónico de Compras Públicas, SECOP).

Even though the annual programmes of ministries and agencies are posted in the SECOP, the information provided is quite limited. The annual programme entries usually include a code for the good or service, a description, the measurement unit (e.g., piece, box, etc.) and the quantity. However, there is no indication of when the purchase will take place.

1.5. Public finance management and budgeting for procurement

Public procurement does not take place in a vacuum, but should be integrated with budgeting and programming systems for optimal results. Indeed, the 2015 Recommendation of the OECD Council on Public Procurement addresses the importance of this integration (see Box 1.2).

The OECD’s 2015 Recommendation on Public Procurement suggests that adherents support integration of public procurement into overall public finance management, budgeting and service delivery processes. To this end, adherents should:

-

Rationalise public procurement spending by combining procurement processes with public finance management to develop a better understanding of the spending dedicated to public procurement, including the administrative costs involved. This information can be used to improve procurement management, reduce duplication and deliver goods and services more efficiently. Budget commitments should be issued in a manner that discourages fragmentation and is conducive to the use of efficient procurement techniques.

-

Encourage multi-year budgeting and financing to optimise the design and planning of the public procurement cycle. Flexibility, through multi-year financing options – when justified and with proper oversight – should be provided to prevent purchasing decisions that do not properly allocate risks or achieve efficiency due to strict budget regulation and inefficient allocation.

-

Harmonise public procurement principles across the spectrum of public service delivery, as appropriate, including for public works, public-private partnerships and concessions. When delivering services under a wide array of arrangements with private-sector partners, adherents should ensure as much consistency as possible among the frameworks and institutions that govern public service delivery to foster efficiency for the government and predictability for private-sector partners.

Source: (OECD, 2015[5])

In September each year, every ministry and public agency in Nuevo León files budget proposals to the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury. The secretariat then reviews and adjusts the proposals according to the availability of resources and the budgets of previous years, before sending it to the state congress for approval. During fact-finding missions, the OECD team was told that such adjustments are often quite arbitrary. The secretariat does not normally consult with the institutions involved to consider their priorities when making adjustments. This is unfortunate, as such a lack of co-ordination not only affects budgets, but procurement. This can lead to pressing situations, such as the need to speed up procurement processes in the last months of the year to fully execute the budget. Nonetheless, in theory, given that the PAAs are developed in January of every year (after the budget has been approved), there should be enough time to adjust the PAA to the approved budgets. Currently, however, there is no systematic link between the budgeting and procurement processes.

Nuevo León’s regulatory framework anticipates multi-year budgeting. The framework requires that the corresponding ministry or entity informs the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury of its multi-year budgeting needs when filing its budget proposal. In turn, Article 14 of the LAASNL establishes that, exceptionally, and upon authorisation by the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury, the Procurement Committee may call for, award and formalise contracts whose payments go beyond the fiscal year or start after the fiscal year in which the contract is formalised. As of May 2017, only one multi-year contract was established (for copy machines). Others, for services like catering in state prisons, are under consideration at present.

1.6. Comprehensive organisational procurement strategy

One of the main weaknesses of Nuevo León’s centralisation process is that the state has not developed a clear strategy for the procurement function. Indeed, procurement is still seen as a purely administrative activity, rather than a strategic activity and policy tool that can help the government accomplish secondary objectives. When undertaking procurement, public officials in Nuevo León privilege a compliance approach, rather than a value-for-money approach. There are several reasons for this. First, procurement operations in Nuevo León are overregulated because of an incorrect assumption that more regulation leads to fewer opportunities for corruption. Second, recent scandals have sparked high levels of public mistrust of government officials. This has in turn driven these officials to protect themselves by strictly observing the letter of the law – even if it hinders the potential for reaping value for money for the public sphere.

Over the last decade, OECD countries have increasing used procurement as a policy tool to support socio-economic objectives like innovation. The economic crisis that started in 2007-08 forced countries to consider using procurement to drive innovation in order to spur a recovery from the global downturn. This was accomplished, for instance, by countries that encouraged innovative companies to bid for government contracts. Some countries also used procurement to ease the socio-economic impact of the crisis on societies. They did this by providing procurement as a substitute for direct social policies to support employment for disadvantaged groups and communities. These examples are notable because they indicate that a shift has occurred among OECD countries. At present, among OECD countries, the main objective of public procurement is not only to achieve value for money (that is, the value of the items and services procured) but to promote broader government objectives.

Because of its economic significance, public procurement has the potential to influence the market in terms of production and consumption trends. It can do so in a way that is favourable to environmentally friendly and socially responsible products and services. In OECD countries, public procurement accounts for about 12% of GDP and 28% of total government expenditure, on average (OECD, 2012[6]). In Mexico, public procurement accounts for about 5% of GDP and over 20% of total government expenditure.

The centralisation process represents an important opportunity to change the mindset of government officials towards procurement. Unfortunately, in Nuevo León, this process was undertaken without a proper consultation to build buy-in among public officials. Nonetheless, the development of the sectoral plan of the SA (its six-year working plan) opens a window of opportunity not only to develop a new vision for Nuevo León’s procurement function, but also to build it through a participative process.

A good strategy clearly defines the functions to be undertaken by the UCC, besides the obvious one of managing procurement operations. The managers of some UCCs believe that providing guidance and advice on how to plan and carry out procurement activities is a necessary organisational function; some may even provide consultancy services. However, where such services exist, the activity is relatively small relative to the UCC’s main function. This may have to do with a worry that UCCs will crowd out the private sector or be perceived as a competitor in the consultancy business. As part of its core business, the operational functions of a UCC often include: 1) procurement management and support; 2) market analysis and relationships; 3) development and operation of the business architecture (e.g., an electronic platform); and 4) administration and reporting (OECD, 2011[4]).

1.7. Proposals for action

1.7.1. The SGNL should set a strategy for the centralisation process and communicate it effectively to the whole-of-government

Governments often introduce a centralised purchasing arrangement because they want to modernise and upgrade their procurement systems in terms of efficiency and functionality. However, as is the case in Mexico, governments often lack the experience and knowledge necessary for the operation of a UCC.

The key question is to what extent the centralisation process, and the role of the SA as the UCC, can generate added-value to the public procurement function in Nuevo León in terms of savings, simplification, modernisation and other critical principles. In a study conducted by the OECD in seven European Union countries (Denmark, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Sweden and the United Kingdom), the OECD found that, under the right conditions, UCCs do generate added value, but not by default (OECD, 2011[4]). Because certain conditions must be present for UCCs to add value, the question becomes whether these conditions are present in Nuevo León.

The truth is that the SA has to earn its place as a reliable and efficient UCC. This requires an effort by the whole-of-government, not only the SA. Interviews conducted during OECD fact-finding missions revealed that current centralised procurement arrangements are not perceived as efficient or simple. Furthermore, those interviewed stated that ministries and agencies are not aware of what their roles should be in making such arrangements successful. In order for the SA to be successful, it must address these issues. Officials could benefit from studying the economic and non-economic factors that make centralised purchasing systems attractive to shareholders (see Figure 1.5).

Source: (OECD, 2011[4]).

In this context, it is important that the SA, as any other UCC, develops a strategy with long-term goals and a clearly defined scope for its operations. This strategy should include the services the SA will provide, the products and services for which it will co-ordinate procurement and the entities of the public sector it will target. Requesting units themselves may want to participate in the development of such a strategy, because of their responsibilities with regards to procurement planning.

One of the main arguments behind centralising procurement is achieving cost-efficiency – in other words, obtaining the best possible value for the taxpayer through effective, sustainable procurement. If this can be achieved, governments can use the savings they take in for investment and public services. Some UCCs elaborate efficiency-related goals into sub-goals, such as streamlining procurement processes, the aggregation of demand through framework agreements and the identification of opportunities for savings. Nuevo León’s SA has communicated to the OECD that its sectoral plan (under development as of June 2017) will include three objectives:

-

cost-efficiency through the standardisation of products and services to be purchased;

-

transparency, by applying the four-eyes principle and focusing control activities on one single procurement unit;

-

leveraging the purchasing power of the state government to support SMEs and local businesses.

Given the general perception in Nuevo León that the centralised arrangement is not delivering, the SA must take certain steps quickly. It is important that the SA make the model attractive by implementing basic elements and bringing more institutions under the centralised umbrella. To begin with, the SA needs to develop – with the participation of shareholders – a strategy with clear goals. Second, the SA needs to create a workforce of procurement professionals who are also qualified to provide advice to the procuring entities. Finally, this advice should be oriented towards customer satisfaction.

Upgrading the e-procurement system SECOP to make procedures easier is a must. UCCs usually introduce electronic aids into their operations, but the extent to which they use electronic tools differs considerably. Generally, electronic and Internet-based platforms are used to publish procurement notices, tender documentation and award results. However, there are differences in the extent to which different UCCs develop electronic systems for the call-off process and the subsequent contract management phase. The publication of electronic catalogues of the goods and services that UCCs provide seems to be common. Electronic purchasing management systems have also been developed by some UCCs to facilitate the procurement process and make it more efficient.

Improving the results obtained so far in Nuevo León’s centralisation process will entail strong political leadership. Indeed, if procurement is to be treated as a strategic activity, government entities will need to operate under a clear mandate, and will need to align political will. For instance, the government will need to advance reforms to the LAASNL and other regulations to remove obstacles for modernisation (e.g., the need to document procurement operations in paper). The government will also need to privilege a value-for -money approach over the current compliance one. It will also need to invest to upgrade the procurement workforce and e-procurement systems. But more importantly, government officials will have to realise that these reforms are worth the effort and, if implemented correctly, will deliver savings that will outweigh the costs.

The OECD has identified certain factors possessed by successful centralised purchasing organisations that obtain savings. The SGNL can learn from this analysis. First, it is important for UCCs to have the support from the owners. The UCC must have a clear mandate to operate. The mandate may be broad or narrow, but it must be clear. Second, good relations with both customers (users) and suppliers are important for building confidence in the operations of UCCs, which in turn are important to motivate tender participation. Third, and related to the second factor, it is important to actually obtain favourable purchasing terms and products, thereby creating legitimacy and loyalty towards the centralised purchasing systems that have been established. Specifically, the more inclined procuring entities are to use the UCC’s services, the more attractive it is for potential suppliers to compete for contracts. UCC competence and behaviour are important drivers of success.

Central purchasing also entails certain risks. The most obvious risk is that the UCC will fail to deliver on its promises by not being responsive to the various stakeholders involved (customers, suppliers, and owners), and by failing to deliver attractive terms. Another important risk is a scenario in which the procedural rules in the public procurement legislation become more important than the economic aspect of procurement, thereby making the UCC difficult and expensive for its customers to use. This often results in a rigid compliance approach (OECD, 2011[4]).

1.7.2. The SA should develop an organisational model and a business model which determines the main features of the procurement function of the SGNL

The reorganisation of the APE does not provide a clear organisational and business model for the procurement function. The first issue to determine is what functions will be performed by the SA. For example, the Organisational Law of the APE establishes that the SA has the power to assist ministries and entities in their procurement planning. However, the scope of such assistance is not clear, and any support in other stages of the procurement cycle (e.g., development of technical specifications and contract management) is not explicit. A UCC is not only a procurement manager but, with its extensive experience and knowledge of public procurement, a knowledge centre. In other words, UCCs can be centres of expertise within the government administration. This expertise should be exploited. The owners of a UCC can use it as a tool for the modernisation of the public administration and the implementation of important policy goals. The SA should take this all into account. It should then assess to what extent the UCC is adequately fulfilling other functions, such as market analysis and development of the IT solution for e-procurement. The SA can then consider reforms to upgrade performance.

Second, the SA should determine which goods and services will be covered under the centralised purchasing arrangements. As discussed during this chapter, some goods and services may be better suited for centralised procurement than others. Applying the common-interest principle would help achieve cost efficiency, while also allowing flexibility for items needed by one or only a few entities. Along with this discussion, the SGNL should define which parastatal entities will participate in the centralised arrangement. The current policy is that all parastatal entities should be covered gradually for goods commonly used, but there has been resistance by some to sign the co-ordination agreement.

While the government of Nuevo León has already decided to centralise procurement in the SA, the OECD recommends that the SA develops a specific approach for implementation. Specifically, the OECD recommends that the SA adopt a step-by-step approach in terms of the goods, services and entities centralised procurement will cover. This will provide the SA with realistic possibilities for successfully building the organisation’s capacity, infrastructure, and performance – without risking its credibility. The most sensitive stage of an UCC’s operations is the start-up phase, since procuring entities may regard the UCC only as a competitor and not as a partner. Building confidence, which is essential for the success of a UCC, takes time. That said, the initial period is often decisive in ensuring a strong outcome. It is important to agree not only on the right first steps the SA will take, but also on the right order of these steps. The main risks are over-ambitious or unrealistic goals set by the owners. Overly aggressive goals jeopardise the possibility of the new UCC becoming a success. Management needs sufficient time, discretion and financial means in order to build the organisation, the infrastructure, the operational models, the systems and the partnerships with the customers (OECD, 2011[4]).

Another determination to make is to what extent centralised procurement will be voluntary or compulsory. Currently, in order for goods and services to be tendered centrally by the SA, participation is mandatory. Since resistance is strong, a voluntary approach would collapse the centralised procurement system. However, as the SA builds up its infrastructure and fixes the reputation of the centralised arrangements, it may apply a differentiated approach. Under this approach, the SA would carefully review goods and services to be centrally purchased from the point of view of the procuring entity’s interests in order to determine whether the use of a centralised scheme should be compulsory or voluntary. Some products may be well suited to compulsory use, while others would be much better suited to voluntary use. By transitioning to a differentiated approach, the SA may also improve the attractiveness of its services.

Finally, the SA may want to review the financing of its role as a UCC. This is a difficult issue, as there is no practice in Mexico for a UCC to charge user fees. In addition, given that the centralised system is still in its early stages and trying to gather support, it would not be convenient to introduce user fees in the short term. Furthermore, user fees could spark legal objections. However, again, as the UCC is strengthened, its nature could become more commercially oriented. It could then start to charge some fees – at least to cover basic costs relative to the organisation of tenders. Currently, the SA charges some fees to potential bidders to register to participate in the tender and to obtain the call for tender (even though call for tender information is published in SECOP and newspapers). The rationale behind these fees is to cover publication costs. These fees may hinder the participation of bidders. To offset this burden, the SA could transfer fees to the procuring entities making use of the UCC services, but only if it makes sure the UCC is delivering in terms of savings, cost-efficiency, competence and simplicity.

1.7.3. Obstacles are often found in procurement regulations. Therefore, the SGNL should undertake a careful review of the normative framework applicable to procurement operations

The OECD has identified several obstacles to upgrading procurement practices in Nuevo León’s normative framework. For example, during OECD fact-finding missions, public officials argued that they had perceived resistance to the process of migrating electronic procedures. The reason for this resistance was that regulations do not explicitly state that electronic documents are as valid as paper ones, and auditors usually request paper files. This is a clarification that could be incorporated into the LAASNL and its By-Laws. In other cases, the use of specific tools is constrained and subject to complicated procedures. For instance, the use of the points and percentages criterion is established in Article 39 of the LAASNL, but its use by a state entity requires an explicit authorisation by the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury. This presents a problem, as this secretariat is not where procurement expertise lies. Furthermore, documentation shows that this issue has caused co-ordination issues. Finally, as described previously, the LAASNL still needs to be updated to align with the latest reforms to the Organisational Law of the APE, which established the role of the SA as the UCC. This need to update the LAASNL is reflected in the unclear roles of the SA and the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury in the Procurement Committee of the APE.

Another concern has to do with overregulating. There is a difficult balance to strike between flexibility and control. Recent scandals at the national and state level in Mexico have led to the faulty assumption that more regulation will lead to less corruption. In fact, the strong compliance approach has limited the ability of procurement officials to seek value-for-money. When reviewing the regulatory framework, the SGNL should bear in mind regulatory burdens imposed on procurement officials. It should then seek controls with clear indicators that allow for the evaluation of the effectiveness of these regulations. Depending on the results, the SGNL could then make these regulations more strict or flexible.

Evaluations of regulations after a period of implementation should be primarily focused on whether the intended outcomes by the regulatory intervention have been achieved. This is the main purpose of retrospective analysis, and it is the systemic application that is recommended in the 2012 Recommendation of the OECD Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance. At present, there is not an internationally recognised or agreed-upon guidance for regulatory evaluation. However, the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015 proposes a set of evaluation criteria that could form the basis for an evaluation framework (Box 1.3) (OECD, 2015[7]).

General criteria

-

Relevance: Do the policy goals cover the key issues at hand?

-

Effectiveness: Was the policy appropriate and instrumental to successfully address the needs perceived, as well as the specific problems the intervention was meant to solve?

-

Efficiency: Do the results justify the resources used? Or could the results be achieved with fewer resources? How coherent and complementary have the individual parts of the intervention been? Is there scope for streamlining?

-

Utility: To what degree do the achieved outcomes correspond to the intended goals?

Additional criteria

-

Transparency: Was there adequate publicity? Was the information available in an appropriate format and at an appropriate level of detail?

-

Legitimacy: Has there been a buy-in effect?

-

Equity and inclusiveness: Were the effects fairly distributed across the stakeholders? Was enough effort made to provide appropriate and equitable access to information?

-

Persistence and sustainability: What are the structural effects of the policy intervention? Is there a direct cause-effect link between them and the policy intervention? What progress has been made in reaching the policy objectives?

Source: (OECD, 2015[7])

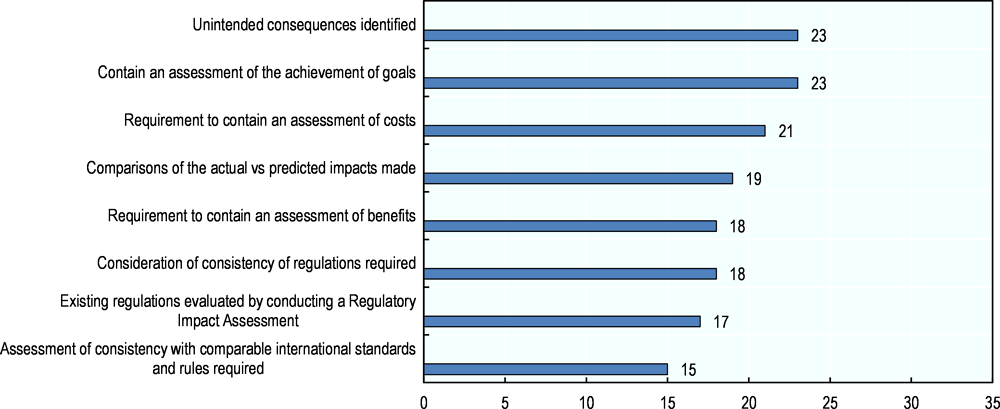

Most methodologies used in OECD countries for ex post regulatory evaluation concentrate on the unintended consequences of a regulation and on the achievement of policy goals (see Figure 1.6).

Source: (OECD, 2015[7])

It is extremely important that the government of Nuevo León consult with the populations that will be affected by regulations (both public and private entities) during the review of the normative framework. A common mistake when designing regulatory interventions is to skip the opinions of the target audiences. Consulting with them will not only allow the SGNL to identify the main regulatory bottlenecks in the procurement process, but also design the required reforms. Such consultation will also facilitate the implementation of reforms through the buy-in built during the consultation process.

1.7.4. Improving the co-ordination between the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury and the SA (and budget and procurement planning) has the potential to streamline procurement operations

During the OECD fact-finding missions, it was evident that procurement is regarded as just another administrative activity in Nuevo León, and co-ordination is weak. In addition, public officials do not see or feel connected to the overall process. Rather, these officials are aware only of their individual experiences in their particular institutions. Blame of others is common, instead of co-operation and looking for co-ordinated solutions. The Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury blames the SA for not putting together the required documents to process payments. The SA blames the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury for not processing payments in a timely manner and for discretionally changing its procurement and budget planning. The SA blames the requesting units for not making their requests in a timely fashion. Finally, the requesting units blame the SA for complex procedures and delays. Such lack of co-ordination also becomes evident when purchase orders and procurement procedures accumulate at the end of the year. This leads to requesting units spending their procurement budgets to avoid them being slashed for the next fiscal year. This situation is unsustainable. Its solution requires efforts by the entire government. If this can be mustered, the new centralised procurement arrangement can be successful.

Centralised procurement will only deliver if: 1) all institutions in Nuevo León recognise their role in the system; and 2) procedures are made clear and simple. Simplicity will also deter corrupt behaviour. In this case, again, political leadership is critical to getting all the stakeholders to sit at the table to define co-ordination mechanisms, leverage current ones (e.g., the Procurement Committee of the APE) and to accomplish this fast before the centralised arrangements lose all credibility. The Executive Co-ordinator of the APE, along with the SA and the Secretariat of Finance and General Treasury, could create a government-wide task force to address the issues that require robust co-ordination. In some discussions, such as those regarding the delay of payments to suppliers, the participation of private stakeholders could also be beneficial.

While the task force may have a temporary mandate, the co-ordination mechanisms defined in it should be permanent. These efforts must deliver solutions in the short term in order to regain the credibility the centralised procurement plan has lost. A lack of effective and quick action could have a devastating effect, so it is essential that the government acts fast. If it does not, resistance to the new system and pressure to leave it could build, voiding the potential benefits of a UCC.

References

European Parliament and Council (2014), Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement and repealing Directive 2004/18/EC, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0024&from=EN.

OECD (2011), “Centralised Purchasing Systems in the European Union”, SIGMA Papers, No. 47, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kgkgqv703xw-en.

OECD (2012), “Progress made in implementing the OECD Recommendation on Enhancing Integrity in Public Procurement”, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/combined%20files.pdf.

OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, https://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2017).

OECD (2015), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

Secretariat of Administration (2016), “Reglamento Interior de la Secretaría de Administración para el Estado de Nuevo León”, http://sgi.nl.gob.mx/Transparencia_2015/Archivos/AC_0001_0004_0155657-0000001.pdf.

State Government of Nuevo León (2017), “Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública para el Estado de Nuevo León”, http://sgi.nl.gob.mx/Transparencia_2015/Archivos/AC_0001_0002_0164702-0000001.pdf (accessed on 08 November 2017).

Notes

← 1. However, some tender processes of the PGJE, the SSPE, and the CTG are carried out by the SA. Regarding the PGJE and the SSPE there is an inconsistency between the LOAPENL and the LAASNL. While the former establishes that the UCC is the entity in charge of their procurement operations, the latter gives powers to the PGJE and the SSPE to manage procurement related with security issues.

← 2. The Fiscal Co-ordination Law (Ley de Coordinación Fiscal) also applies to the use of some federal resources.

← 3. This list is not exhaustive and describes only the main laws and regulations applicable.

← 4. In Mexico, public procurement is regulated by the laws mentioned previously, leaving no room for the application of private law.