Chapter 7. Fostering effective risk management and internal controls in Nuevo León

This chapter assesses how Nuevo León fosters risk management and internal control in its procurement processes against international models and better practices. It provides an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the internal control environment and the framework for risk assessment, treatment and monitoring. It also looks at how these aspects could be strengthened to align with international standards and good OECD country practices in the areas reflected in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement.

A government’s procurement activities are particularly at risk of waste, mismanagement, fraud and corruption. This is due to a number of factors, including the large number and value of transactions a government undertakes and the close interactions between the public and private sectors. Risk management and internal control activities help an entity to address these risks and support an accountable and ethical public procurement system.

The federal government of Mexico has undertaken several initiatives to implement a consistent and effective internal control system across the country. The Secretariat of Public Function of the federal government of Mexico developed the General Standard for Internal Control (Norma General de Control Interno) in 2006. The Standard was revised for application at state levels. The revision resulted in the General Standards of Internal Control Model for States (Modelo de Normas Generales de Control Interno para los Estados), which was implemented by the State Government of Nuevo León (SGNL) in 2013.

The General Standards of Internal Control Model for States is based on five elements (or standards) set by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO)'s Internal Control Integrated Framework. These include:

-

the control environment;

-

risk evaluation and administration;

-

control activities;

-

information and communication; and

-

oversight and continuous improvement of internal control (COSO, 2013[1]).

To implement the general standards, the SGNL established the Single Internal Control System (Sistema Único de Control Interno), which aimed to implement internal control mechanisms in July 2013. The Office of the Comptroller and Government Transparency (Contraloría y Transparencia Gubernamental) (hereafter, the Comptroller’s Office) has been devoting efforts to strengthen the structure and the functioning of the internal control units. The Anticorruption Plan of the SGNL (Plan Anticorrpción del Poder Ejecutivo del Estado de Nuevo León), published in January 2017, reaffirmed the SGNL's commitment to having a sound implementation of the Single Internal Control System.

This chapter assesses the State Government of Nuevo León (SGNL)'s internal control and risk management frameworks in public procurement activities against the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement (hereafter referred to as the Recommendation) and international good practices. In particular, it will assess the SGNL's internal control and risk management frameworks against the principles of the Recommendation outlined in Box 7.1.

The Council:

XI. Recommends that Adherents integrate risk management strategies for mapping, detection and mitigation throughout the public procurement cycle. To this end, Adherents should:

i. Develop risk assessment tools to identify and address threats to the proper function of the public procurement system. Where possible, tools should be developed to identify risks of all sorts - including potential mistakes in the performance of administrative tasks and deliberate transgressions - and bring them to the attention of relevant personnel, providing an intervention point where prevention or mitigation is possible.

ii. Publicise risk management strategies, for instance, systems of red flags or whistle-blower programmes, and raise awareness and knowledge of the procurement workforce and other stakeholders about the risk management strategies, their implementation plans and measures set up to deal with the identified risks.

XII. Recommends that Adherents apply oversight and control mechanisms to support accountability throughout the public procurement cycle, including appropriate complaint and sanctions process. To this end, Adherents should:

(…)

iv. Ensure that internal controls (including financial controls, internal audit and management controls), and external controls and audits are coordinated, sufficiently resourced and integrated to ensure:

-

the monitoring of the performance of the public procurement system;

-

the reliable reporting and compliance with laws and regulations as well as clear channels for reporting credible suspicions of breaches of those laws and regulations to the competent authorities, without fear of reprisals;

-

the consistent application of procurement laws, regulations and policies;

-

a reduction of duplication and adequate oversight in accordance with national choices; and

-

independent ex-post assessment and, where appropriate, reporting to relevant oversight bodies.

Source: (OECD, 2015[2])

As outlined in the Recommendation, an internal control framework should include risk management strategies and internal controls. A solid internal control framework is the cornerstone of an organisation's defence against various integrity and efficiency risks that are present in public procurement processes. An effective internal control framework includes policies, structures, procedures, and processes that enable an organisation to identify and appropriately respond to risks. Internal controls constitute checks and balances that are the responsibility of management and are carried out by staff on a daily basis. Internal controls include a wide range of processes seeking to ensure that employees and managers exercise their duties within the parameters established by the entity.

An effective internal control framework should ultimately help the organisation comply with its mandate and relevant legislation, safeguard an organisation's assets, and facilitate internal and external reporting. In public procurement, particularly, sound functioning of an internal control framework helps ensure that public resources are spent in an efficient and effective way.

This chapter provides an overview of the SGNL's internal control framework and structures as they relate to public procurement activities. Furthermore, the chapter identifies strengths and weaknesses of the SGNL's internal control framework, and provides proposals for action.

7.1. Nuevo León’s internal control framework, structures and environment

In Nuevo León, the Comptroller's Office (Contraloría y Transparencia Gubernamental) is the main state-level entity responsible for strengthening the coordination with the internal control and oversight bodies of the agencies and entities of the state public administration. In particular, the Directorate of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies (Dirección Órganos de Control Interno y Vigilancia) coordinates, reviews and evaluates internal control activities of the internal control units. In particular, the Comptroller’s Office is responsible for:

-

establishing and issuing rules that regulate instruments and procedures of internal control of the agencies and entities of the SGNL;

-

monitoring compliance of the agencies and entities of the SGNL to the legal provisions on financial and public resources management; and

-

establishing programmes aimed at fulfilling the commitments contained in the Code of Ethics of public servants of the SGNL, in order to promote ethical values.

The Central Procurement Body (Unidad Centralizada de Compras, UCC), under the Secretariat of Administration (Secretaría de Administración, SA) is in charge of procuring goods and services for the 21 central agencies and 24 (of 65) parastatal entities in Nuevo León. Previously, the Secretariat of Administration carried out purchasing activities only for the central agencies (gobierno central). With the new regulations, in force as of April 2016, it also does this for the parastatal entities that have signed a cooperation agreement with the UCC.

The UCC is involved in the entire procurement process, from defining needs and selecting suppliers to ensuring the delivery of goods and services. However, as described in Table 7.1, the unit that requires the procurement is responsible for defining its needs. Furthermore, once a contract is awarded, each unit is involved in managing the contracts. In this sense, internal control of not only the UCC, but also each unit is crucial to ensuring efficient and effective public procurement. Accordingly, the risks that each entity faces (according to its responsibilities) need to be adequately identified and properly managed.

The UCC is also responsible for preparing and submitting an annual report of results of corresponding progress of the annual programme of procurement to the Procurement Committee, the State Treasury or Municipal Treasury, as appropriate, and the Comptroller or internal control unit.

7.1.1. Nuevo León could ensure that its internal control environment is a supportive foundation for its internal control system

The Comptroller’s Office is responsible for the oversight of public works in Nuevo León, as well as the procurement of goods and services in the state. The Office of Control and Audit of Public Works carries out reviews, audits, verifications, monitoring actions and expert reports. It does this work in order to ensure that public works, procurements and related services are carried out according to the planning, programme, budget, and agreed-upon specifications mandated by the internal control bodies of the agencies and entities of the state public administration. In addition to checking for compliance with state laws and regulations, the office is also responsible for verifying the procurement process from the approval, award, contracting and payment of advances to termination and delivery. However, it remains the responsibility of the requesting entity to ensure the procurement is well executed. These directorates have some resource limitations, particularly relating to staff and the professionalisation of staff.

In 2007, the Executive Power of the State of Nuevo León issued an Agreement for the Functional Coordination of the Internal Control Bodies. This agreement outlines that: the Comptroller's Office shall functionally coordinate the internal control and monitoring system between the entities and the Comptroller’s Office, and shall carry out public inspection and evaluation; and that entities that have established their own internal control body should coordinate and plan their activities with the Comptroller’s Office, to avoid duplication.

The coordination is carried out through the Annual Audit and Internal Control Programme (Programa Anual de Auditoría y Control Interno, PAACI), which is prepared in accordance with the 2007 agreement and the associated guidelines. The audit programme includes audits titles, associated timelines and areas responsible.

The Internal Control Normative Provisions sent by the Comptroller’s Office to the state public administration units and entities are in effect through a letter dated 3 July 2013. These provisions are based on the Internal Control Framework issued at the federal level. According to the Normative Provisions, the Single Internal Control System comprises the set of processes and mechanisms that are applied in an entity in the stages of planning, organising, implementing, directing, and monitoring their management processes, to give certainty to the decision-making process and to achieve their objectives in an environment of integrity, quality, continuous improvement, efficiency and compliance with the law (Nuevo León, 2013[3]).

The purposes of the Single Internal Control System, with respect to the achievement of the objectives of the units or entities, are outlined in the Table 7.2.

The Normative Provisions outline specific standards on: the control environment; risk assessment and administration; control activities; information and communication; and continuous improvement of internal control.

7.1.2. Nuevo León could consider making better use of its Internal Control reporting function for identifying gaps, issues and risks and reporting on them to management

Each entity’s Internal Control Unit is responsible for reporting to the Directorate of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies (La Dirección de Órganos de Control Interno y Vigilancia) within the Comptroller’s Office every two months on whether the entity has complied with relevant laws, norms and requirements—including those related to procurement. As at May 2017, 11 entities had internal control units. For those entities without an Internal Control Unit, including the UCC, this responsibility is given to an Internal Control contact—a person who has another full-time job, but takes responsibility for completing the reporting template every two months. If an entity has not met requirements, they need to provide an explanation. This type of reporting can assist with the consistent application of procurement laws, regulations, and policies across the government. However, although the Office of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies indicated that they try to follow up on these cases, they have limited resources for doing so and there is no process for collating this information to identify trends or report on it to management.

A government should also have a system for reliable reporting on compliance with laws and regulations as well as clear channels for reporting credible suspicions of breaches of those laws and regulations to the competent authorities, without fear of reprisals (whistle-blowing and complaint mechanisms are discussed in Chapter 6).

7.1.3. Nuevo León could ensure that clear objectives are established at the outset of a procurement activity

Before determining risks and internal controls, it is vital that an entity establishes clear objectives for the entity as a whole, for individual programme and for specific activities. For a procurement activity, it should be clear why the purchase is being made, what objective it will support, how value for money will be ascertained and what the key requirements and merit criteria for the procurement will be. Where there is no clear objective, internal control activities and risk management cannot be effectively implemented. It is possible to have a controlled activity with a risk management process in place that does not achieve a valuable or desired outcome.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the SGNL’s yearly planning for public procurement is still quite fragmented and there is some flexibility within budgets to make purchases that were not initially planned, as long as the total spending does not exceed the budget. Clearer objectives and a more controlled and robust planning and monitoring system would assist with ensuring the integrity of procurement activities.

7.1.4. Nuevo León could ensure that its tone at the top, human resources policies, and defined roles and responsibilities for internal control support its internal control system

Once clear objectives are established and have been effectively communicated to relevant staff, management should consider the elements of its control environment. The control environment is the foundation for all other components of internal control. According to the INTOSAI’s Guidelines for Internal Control Standards, elements of the control environment are:

-

the personal integrity and ethical values of management and staff, including a supportive attitude towards internal control throughout the organisation;

-

commitment to competence;

-

the “tone at the top” (i.e., management’s philosophy and operating style);

-

organisational structure; and

-

human resource policies and practices (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 17[4])

Embedding a culture of personal integrity and an ethical “tone at the top” should be an ongoing part of an organisation’s operations. It requires the commitment of management and staff, the positive reinforcement of ethical actions and attitudes and also, the censure of unethical behaviours.

One of the priorities of the Nuevo León government, as outlined in the 2016–2021 State Plan, is “combatting corruption”. A culture of integrity and an ethical “tone at the top” is vital for combatting corruption. As discussed in Chapters 4 and 6, Nuevo León has taken some action to promote a culture of integrity through training courses, the implementation of a commencement “honesty test” and the introduction of a code of ethics.

The Executive Coordination of the State Public Administration (Coordinación Ejecutiva de la Administración Pública del Estado) requires that public servants sign the Code of Ethics, stating they understand it and commit to comply with it. Signing the Code of Ethics is part of the hiring process.

The Comptroller's Office has also carried out training sessions for internal comptrollers, with the first one conducted in March 2016 on performance of internal control units in the state public administration (attended by 135 officials). In April 2016, another training session was organised on enhancing transparency and prevention of corruption through internal control units (attended by 127 officials); and in May 2016, a session was presented on internal control and risk management. As discussed in Chapter 6, procurement officials have received only general training and would benefit from more specific training on public procurement integrity.

These types of training sessions can help staff understand the roles and responsibilities for internal control. This should be communicated more broadly as well, as everyone in an entity bears some responsibility for internal control and risk management. Managers are directly responsible for all activities, including designing, implementing, and monitoring the internal control system. Internal auditors examine and contribute to the ongoing effectiveness of the internal control system through their audits and recommendations; however, auditors should not have the primary responsibility for the internal control system—this system needs be owned and implemented by management. Staff also share in the responsibility—implementing internal controls and reporting issues, emerging risks and irregularities as they occur.

7.2. Risk management

7.2.1. Nuevo León could integrate risk management strategies for the assessment, treatment and monitoring of risk throughout the public procurement cycle

As previously mentioned, public procurement is particularly susceptible to risks of waste, mismanagement, fraud, and corruption. Further, there is a risk that the failure to achieve procurement outcomes or the delayed delivery of goods and services could hinder the performance of an entity’s functions and could result in an entity not fulfilling its mandate.

After establishing clear objectives and setting a firm control environment foundation, the risks that may hinder the achievement of objectives and outcomes need to be identified. Nuevo León indicated that it considers this a vital element of planning process, which aligns with good governance practices among OECD member countries. Better practice also provides that risk management should be considered an integral part of the institutional management framework rather than managed in isolation. Risk management should permeate the organisation's culture and activities in such a way that it becomes the business of everyone within the organisation. Thus, all the officials that participate at any stage of public procurement—from the entity that requires the procurement to the UCC and Comptroller’s Office—should take responsibility for risk management.

While the SGNL’s Internal Control Normative Provisions (2013) state that the internal control system should “have mechanisms […] to identify and manage the risks that may block [objectives]” and the SGNL Anticorruption Plan reaffirms the importance of risk management, the SGNL has not established specific risk management activities in its public procurement processes (Nuevo León, 2013[3]).

7.2.2. Nuevo León could develop risk assessment tools and methodologies to identify, assess and treat risks to the proper function of the public procurement system

As part of a risk management strategy, risk assessments help entities to understand risk exposure and allow public organisations to make cost-effective, risk-based decisions about control activities. This includes identifying risk factors (e.g. why would corruption occur in these specific areas of the procurement activity?). The evaluation of the probability that the identified risks might occur and the potential impact of the materialisation of these risks is also essential to prioritise responses and allocate adequate resources.

The output of the risk assessment is the identification of inherent and residual risks, which form the basis of the risk treatment action plan. Finally, considering that the risk environment is constantly evolving the risk management strategy should be monitored and refined on an ongoing basis to ensure the risk treatments remain effective.

Risk management is key to understanding risk exposure and allowing public organisations to reach informed risk management decisions. COSO defines entity risk management as “a process effected by an entity's board of directors, management and other personnel, applied in strategy setting and across the entity, designed to identify potential events that may affect the entity and manage risk to be within its risk [tolerance], to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of entity objectives” (COSO, 2004[5]). This broad definition may also be applied in the public sector, where the concept of operational risk management would encompass the systems, processes, procedures, and culture that facilitate the identification, assessment, evaluation, and treatment of risk in order to help public sector organisations successfully pursue their strategies and performance objectives (OECD, 2013[6]).

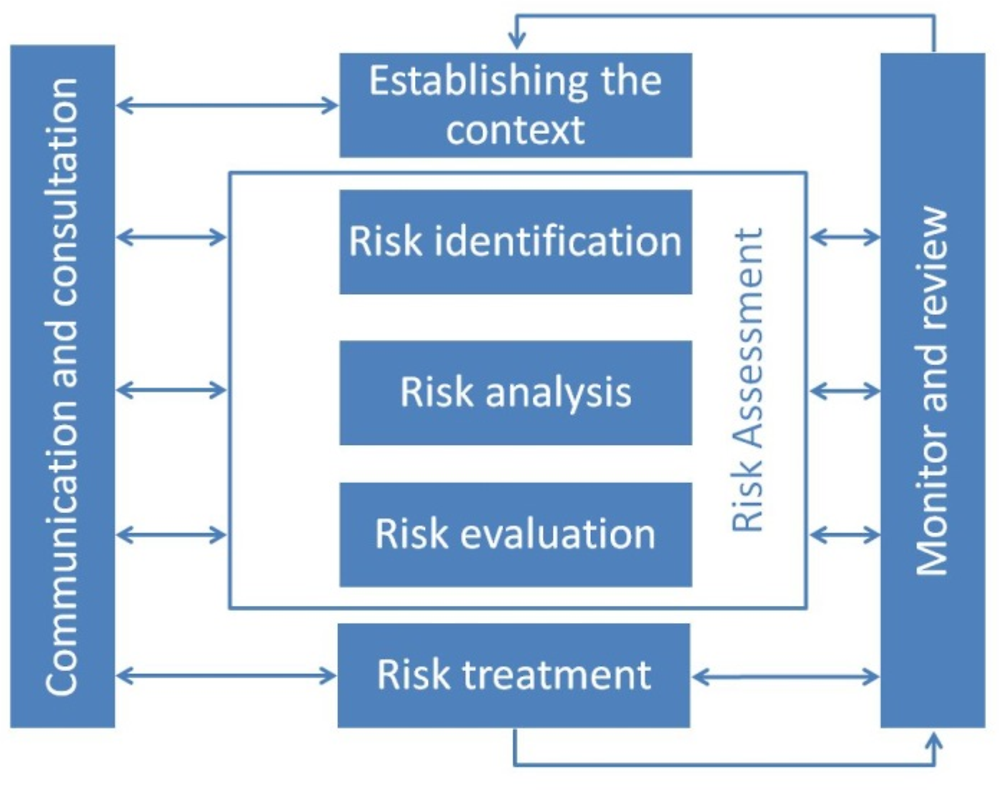

Risk assessment is a three-step process that starts with risk identification and is followed by risk analysis (or ‘mapping’), which involves developing an understanding of each risk, its consequences, the likelihood of those consequences occurring, and the risk’s severity. The third step is risk evaluation, which involves determining the tolerability of each risk and whether the risk should be accepted or treated. Risk treatment is the process of adjusting existing internal controls or developing and implementing new controls to bring a risk’s severity to a tolerable level (Figure 7.1).

(ISO 31000:2009)

Source: Adapted from (ISO, 2009[7]).

Nuevo León should develop risk assessment tools and methodologies to identify, assess and treat risks to the effective and ethical achievement of public procurement objectives. Identifying risks and bringing them to the attention of relevant personnel provides an opportunity for intervention, where prevention or treatment is possible.

The case study in Box 7.2 provides an example of how to integrate risk assessment into a tendering process. In this example, the entity is focusing on risks to health and safety, but a similar approach could be applied when looking at risks of waste, mismanagement, fraud and corruption.

An Australian Government federal entity used a wide range of contractors on a regular basis, for example, for IT support, corporate services, professional advice, publicity and promotion, and alterations. The role of the entity involved significant public access to their facilities. The agency needed to be able to effectively manage high levels of risk without assigning unnecessary resources.

The entity revised its business processes to require a risk assessment before entering into any contracts. The level of risk was determined by a standard risk survey template. For example, the template assessed whether the work of the contractor might pose a risk to the safety of members of the public, the degree of financial risk and so on. The level of risk then informed decisions on:

-

which contract form to use, from a set of standard contracts maintained by the entity;

-

how the contract would be managed and by whom;

-

the transition-in measures necessary, for example, determining the type of briefing the incoming contractors should receive on the task, the entity’s environment and on issues such as workplace health, safety and security;

-

the monitoring and management processes necessary; and

-

how the contract was to be evaluated and the process completed.

Determining these issues at the planning stage also allowed the entity to plan their resource requirements for managing the contract.

Source: Adapted from Developing and Managing Contracts: Getting the right outcome, achieving value for money (ANAO, 2012, p. 19[8]).

7.2.3. Nuevo León could raise awareness and knowledge among its workforce and other relevant stakeholders about its risk management strategies

Communication and consultation, monitoring, and reviewing should be continuous elements of the risk management cycle. Communication and consultation with internal and external stakeholders is a key step towards securing their input into the process and giving them ownership of the outputs of risk management.

It is also important to understand stakeholders’ concerns about risk and risk management, so that their involvement can be planned and their views taken into account in determining risk criteria (OECD, 2013[6]) . Clear communication of how risks should be identified, assessed and treated will assist staff in addressing risks through the procurement process.

7.2.4. Nuevo León could integrate the regular monitoring, reviewing and reporting of risks into its procurement processes

Monitoring and reviewing supports the identification of new risks and the reassessment of existing ones when there are changes in the organisation’s objectives or in its internal and external environment. This involves scanning for possible new risks and learning lessons about risks and controls from the analysis of successes and failures (OECD, 2013[6]). Timely reporting assists management to intervene, where necessary to prevent or address risks.

When identifying and monitoring risks, it is useful to be aware of particular red flags that may indicate corruption or fraud in a procurement process. The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy has come up with a list of red flags that should be considered, as outlined in Box 7.3.

-

Physical losses of goods

-

Unusual relationship with suppliers

-

Manipulation of data

-

Photocopied documents

-

Incomplete management/audit trail

-

IT controls of audit logs disabled

-

Budget overspends

-

IT login outside working hours

-

Unusual invoices (e.g. format, numbers, address, phone)

-

Vague description of goods/services to be supplied

-

Duplicate/photocopy invoice

-

High number of failed IT logins

-

Round sum amounts invoiced

-

Favoured customer treatment

-

Sequential invoice numbers over an extended period of time

-

Interest/ownership in external organisation

-

Non-declaration of interest/gifts/hospitality

-

Lack of supporting records

-

No process identifying risks (e.g. a risk register)

-

Unusual increases/decreases in amounts

Source: (OECD, 2015, p. 152[9])

In order to support and facilitate the implementation of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, the OECD has developed an online Public Procurement toolbox, which includes a section on how to identify risks or ‘red flags’ in a procurement process, as outlined in Box 7.4.

In order to support and facilitate the implementation of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, the OECD has developed the Public Procurement Toolbox. While referring to 12 integrated principles of the Recommendation, it provides public officials with tools for successfully implementing procurement activities, as well as country-specific examples that showcase how to tackle procurement challenges in complex environments.

A designated tool, “Indicators of procurement risk”, is provided by the Toolbox with regard to the risk management principle. It is designed specifically for procuring entities and can be implemented at all stages of the procurement process. It serves as a guide to identify potential corruption risks, and to flag what type of risks procurement practitioners might face.

Depending on the procurement stage and the complexity of the procurement, it is ultimately each procuring authority’s responsibility to identify potential risks and ‘red flags’ and to manage these risks through treatments or internal controls. The following are a number of “red flags” that could help identify corruption and fraud risks in a tendering process:

-

Pre-tendering phase

-

Planning and budgeting: Lack of an annual procurement plan aligned with strategic objectives; cost estimates inconsistent with market rates; or government unable to oversee units in charge of purchase.

-

Definition of requirements: No clear conditions regarding technical requirements; limitations imposed on foreign participants; unclear selection and award criteria; tender requirements drafted by a biased service provider; inappropriate care taken on the anonymity of suppliers or bidders; or selection of unqualified providers due to fraudulent quality assurance certificates.

-

Choice of procedure: Lack of strategy for non-competitive tenders; misuse of exception procedures; or inconsistent timeframes.

-

-

Tendering phase

-

Invitation to tender: Lack of public notice; invitation advertised on a limited basis; non-public information disclosed; insufficient information included in public notice; or unsealed or opened bid envelopes.

-

Evaluation and analysis of bids: Limited number of bids; similarities between bids; delayed bid evaluation; or vested interests among the evaluation committee members.

-

Award: Lack of lists of firms excluded from procurement; rigged selection criteria; lack of submitted certificates; or lack of access to records on procedure.

-

-

Post-award phase

-

Contract management: Modifications in contract conditions; product or service not meeting contract requirements; lack of penalty clauses; or lack of due reporting of contract changes.

-

Order payment: Lack of internal or external audit activities; financial inconsistencies between contracts; late payments and invoices; or invoicing for unsupplied goods or services.

-

Source: (OECD, 2017[10]).

7.3. Internal control activities

One fundamental way risks are mitigated and treated is through the implementation of internal controls. Internal controls are implemented by an entity’s management and personnel and continuously adapted and refined to address changes to the entity’s environment and risks. Internal control activities are designed to address risks that may affect the achievement of the entity’s objectives and to provide reasonable assurance that the entity’s: operations are ethical, economical, efficient and effective; accountability and transparency obligations are met; activities and actions are compliant with applicable laws and regulations; and resources are safeguarded against loss, misuse, corruption and damage (INTOSAI, 2010[4]).

7.3.1. Nuevo León could strengthen, standardise and integrate its Internal Control activities to ensure that reasonable assurance is provided over the integrity of the procurement process

According to INTOSAI’s Guidelines for Internal Control Standards, internal control activities should occur throughout at entity, at all levels and in all functions. They include a range of detective and preventive control activities as diverse as:

-

authorisation and approval procedures;

-

segregation of duties (authorising, processing, recording, and reviewing);

-

verifications;

-

reconciliations;

-

reviews of operating performance;

-

reviews of operations, processes, and activities; and

-

supervision (assigning, reviewing, and approving) (INTOSAI, 2004).

For example, authorising and executing procurement transactions should only be done by persons acting within the scope of their authority. Authorisation is the principal means of ensuring that only valid transactions and events are initiated as intended by management. Authorisation procedures, which should be documented and clearly communicated to managers and employees, should include the specific conditions and terms under which authorisations are to be made. Conforming to the terms of an authorisation means that employees act in accordance with directives and within the limitations established by management or legislation (INTOSAI, 2010[4]).

7.3.2. Nuevo León could review its procurement system to ensure that each internal control serves a purpose—with its benefits outweighing its costs—and that the overall system is controlled, ethical and efficient

Internal control activities for procurement should be designed to provide reasonable assurance to management that risks are being addressed and that the goal of the activity (for which the procurement is required) is being achieved. Internal controls should not attempt to provide absolute assurance—as this would constrict activities to a point of severe inefficiency.

‘Reasonable assurance’ is a term often used in audit and internal control environments. It means a satisfactory level of confidence, given due consideration of costs, benefits and risks. Determining how much assurance is reasonable requires judgment. In exercising this judgment, managers should identify the risks inherent in their operations and the levels of risk they are willing to tolerate under various circumstances. Reasonable assurance accepts that there is some uncertainty and that full confidence is limited by the following realities: human judgment in decision-making can be faulty; breakdowns can occur because of simple mistakes; controls can be circumvented by collusion of two or more people; and management can choose to override the internal control system (INTOSAI, 2010[4]).

In setting internal controls, management should consider the costs of each control—e.g., monetary costs, time costs, and opportunity costs. Management needs to weigh the potential benefit of each control against the potential cost and ensure that benefits will outweigh costs. If this is not the case, management should consider alternate methods of control that will achieve the same desired outcome. Management should monitor internal control systems and adapt them, where necessary, to ensure that internal controls are pitched at the right level to be effective and provide reasonable assurance while not overburdening systems and staff with controls to such a point that quality, timeliness and responsiveness are affected. A system out of balance can lead to staff circumventing burdensome control processes, which defeats the purpose and can expose an entity to additional risks.

Internal controls also provide reasonable assurance to the public and key stakeholders that government transactions are being undertaken in a transparent, ethical and fair manner. As mentioned, procurement is a government activity that is particularly vulnerable to fraud and corruption. The government needs to put levels of control in place to ensure that public funds are being spent appropriately, that value for money is being achieved, that regulations and laws are complied with and that suppliers and tenderers are treated fairly and without favouritism. This is a matter of reputation and credibility. There are two sides to this. On the one hand, internal controls increase confidence in government and promote fair and consistent treatment of key stakeholders. On the other hand, internal controls that are out of balance or have too many layers of bureaucracy can lead to lethargic administrative processes that reduce the credibility of government.

During OECD fact-finding missions, staff indicated that a culture has developed in the SGNL where staff purchase items (such as ink for the printers) with their own personal funds, without prior authorisation, and then seek, and receive, reimbursement. This culture appears to have developed as a result of an inefficient and cumbersome purchasing system. For example if staff purchase their own airline tickets for work travel and then receive reimbursement, with little to no control over the cost of the ticket, there is no assurance that value for money was achieved or that the expense was made in alignment with public procurement law.

Another fundamental internal control is segregation of duties. It is a basic principle that no single individual or team should control all key stages of a procurement activity. Duties should be assigned to a number of individuals to ensure that effective checks and balances exist and to reduce the risk of fraud and corruption. At some stages of the procurement cycle, the SGNL has quite a few players involved. On the one hand, segregation of duties is a beneficial control. However, taken out of balance—where too many players are involved—this control can create new problems and introduce new risks.

It was raised during fact-finding missions that the SGNL’s complex multi-faceted procurement system sometimes results in suppliers not being paid for up to six months. This is an example of internal controls having unintended negative consequences. Having suppliers left unpaid for 6 months is an untenable situation. A government with a bad reputation in the marketplace—whether from corrupt practices or from being an inefficient organisation that does not pay its bills on time—is not a government that can achieve the best results for taxpayers. Suppliers who are not paid on time will be hesitant to engage with the government again, and where there is reduced supply, costs can increase.

7.3.3. Nuevo León could ensure the internal control system is monitored and that there are clear means for adapting and refining procedures to respond to changes in objectives, risks and circumstances

Internal control activities are a vital element of a functioning and ethical public service, but internal controls out of balance can lead to additional risks, costs and inefficiencies. A balanced internal control system, coupled with a culture of integrity promotes good governance and is essential to securing public trust.

Further, internal control should be a dynamic process that is refined and adapted as risks and environments change. An internal control system is more effective when it is monitored and has clear means for responding to changes in objectives, risks and circumstances.

7.4. Proposals for action

In order to develop effective internal control mechanisms and risk management in public procurement and to help combat corruption, the following actions could be undertaken by the State Government of Nuevo León.

-

Nuevo León’s internal control framework, structures and environment

-

Nuevo León could ensure that its Internal Control environment is a supportive foundation for its internal control system

-

Nuevo León could consider making better use of its Internal Control reporting function for identifying gaps, issues and risks and reporting on them to management.

-

Nuevo León could ensure that clear objectives are established at the outset of a procurement activity.

-

Nuevo León could ensure that its tone at the top, human resources policies, and defined roles and responsibilities for internal control support its internal control system.

-

-

Risk Management

-

Nuevo León could integrate risk management strategies for the assessment, treatment and monitoring of risk throughout the public procurement cycle

-

Nuevo León could develop risk assessment tools and methodologies to identify, assess and treat risks to the proper function of the public procurement system.

-

Nuevo León could raise awareness and knowledge among its workforce and other relevant stakeholders about its risk management strategies.

-

Nuevo León could integrate the regular monitoring, reviewing and reporting of risks into its procurement processes.

-

-

Internal control activities

-

Nuevo León could strengthen, standardise and integrate its Internal Control activities to ensure that reasonable assurance is provided over the integrity of the procurement process

-

Nuevo León could review its procurement system to ensure that each internal control serves a purpose—with its benefits outweighing its costs—and that the overall system is controlled, ethical and efficient

-

Nuevo León could ensure the internal control system is monitored and that there are clear means for adapting and refining procedures to respond to changes in objectives, risks and circumstances.

-

References

ANAO (2012), “Developing and Managing Contracts: Getting the right outcome, achieving value for money”.

COSO (2004), COSO Enterprise Risk Management -- Integrated Framework, http://www.aicpastore.com/AST/Main/CPA2BIZ_Primary/InternalControls/COSO/PRDOVR~PC-990015/PC-990015.jsp (accessed on 01 August 2017).

COSO (2013), “Internal Control - Integrated Framework”, https://www.coso.org/Pages/ic.aspx (accessed on 11 September 2017).

Gobierno del Estado de Nuevo León (2013), “Nuevo León’s Internal Control Normative Provisions”, http://oecdshare.oecd.org/gov/sites/govshare/psi/integrity/Shared%20Documents/Nuevo%20Leon%20Integrity%20Review/Questionnaire%20integrity%20Review/13.%20Anexo%2013.%20Disposiciones%20Normativas%20Control%20Interno%20en%20APENL.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2017).

INTOSAI (2010), “Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector”, INTOSAI Guidance for Good Governance, No. GOV 9100, http://www.issai.org/en_us/site-issai/issai-framework/intosai-gov.htm (accessed on 01 August 2017).

ISO (2009), ISO 31000-2009 Risk Management, https://www.iso.org/iso-31000-risk-management.html.

OECD (2013), “Strengthening integrity in the Italian public sector”, in OECD Integrity Review of Italy: Reinforcing Public Sector Integrity, Restoring Trust for Sustainable Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264193819-4-en.

OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/ (accessed on 11 September 2017).

OECD (2015), Effective Delivery of Large Infrastructure Projects: The Case of the New International Airport of Mexico City, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264248335-en.

OECD (2017), Public Procurement Toolbox, http://www.oecd.org/governance/procurement/toolbox/ (accessed on 11 September 2017).