Chapter 1. A regional agenda for economic diversification in Central Asia

This chapter analyses the major drivers of economic growth in Central Asia since 2000, notably commodities exports and migrant remittances, and their effects, such as the dependence on a few commodities and on labour migration. It also offers an overview of the challenges ahead to further diversify the Central Asian economies, in particular those related to public governance, connectivity and the business environment. It then highlights the major business environment issues that are the focus of the next chapters.

The need for diversification

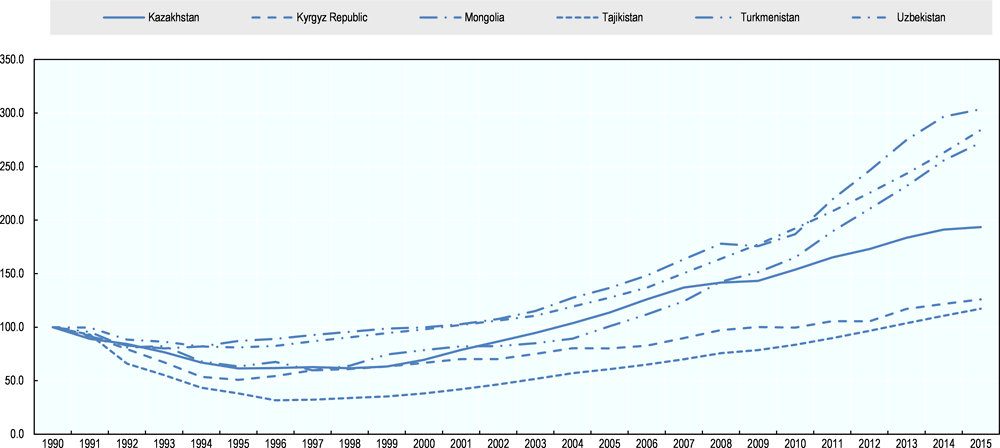

The economies of Central Asia (CA) – here defined as the five former Soviet republics of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) plus Mongolia – experienced an unprecedented period of growth from 2000 to 2016, as they bounced back from the transition recession of the 1990s and began to reap the benefits of market reforms. Real gross domestic product (GDP) grew at an average annual rate of 7%, despite a sharp slowdown following the drop in global commodity prices in 2014-15, and GDP per capita in purchasing-power parity (PPP) USD rose by a staggering 14% per year. Labour productivity growth averaged almost 5% and poverty rates halved (Figure 1.1) (World Bank, 2017[1]; IMF, 2017[2]). The CA economies were also able to attract international investors: between 1997 and 2015, net inflows of foreign direct investment increased more than six-fold (World Bank, 2017[1]).

Source: (World Bank, 2017[1])

These growth figures can partially be explained by a “catch-up effect”. The theory of convergence suggests that emerging economies’ GDP per capita grows faster than developed countries’ because diminishing returns, especially of capital, are less important than in capital-rich economies. Catching-up economies can also leverage the know-how in production processes, technology and institutions available to developed economies (Sachs, 1995[3]; Abramovitz, 1986[4]).

Since the turn of the century, most of the Central Asian economies have exhibited a fairly strong convergence dynamic, with hydrocarbon and metal exporters leading the way in closing the distance to OECD levels of income (Figure 1.2). However, with the exception of Kazakhstan (close to Chile’s GDP per capita), they remain below the 50% mark in purchasing-power parity (PPP) terms,1 and their distance from the OECD average is even greater when measured using actual exchange rates. Moreover, the convergence process has largely stalled since 2013. Getting the Central Asian economies back onto a convergence trajectory, in terms of both living standards and productivity, is thus a critical challenge.

Source: (World Bank, 2017[1])

Note: Statistics for Turkmenistan is available only since 2010.

Source: (UN, 2017[5])

Beyond the catch-up effect, other dynamics underlie the strong growth since 2000 in Central Asia: exports of raw materials during a period of exceptionally high commodity prices and significant remittances from labour migrants. Booming Chinese demand was key to this dynamic. China's need for commodities (such as coal, copper, oil and gas) boosted the exports of Central Asian countries and also those of the Russian Federation, which in turn absorbed growing numbers of Central Asian workers, who sent remittances to their home countries. In addition, the recovery from the severe recession of the early 1990s, which followed the collapse of communism and the start of the market transition, owed much to policy reforms that enabled deeper international integration, the growth of private-sector activities and more efficient allocation of resources (IMF, 2014[6]).

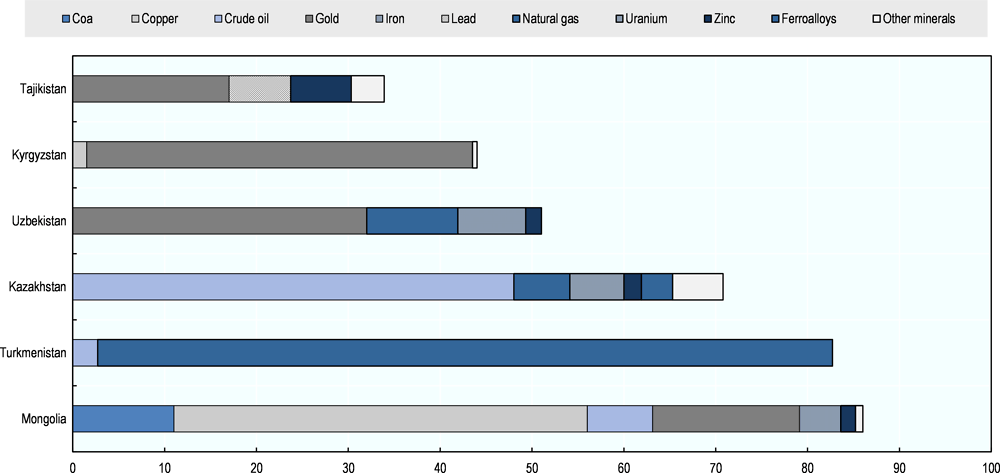

Hydrocarbon and mineral commodity exports and migrant remittances have been the main drivers of growth

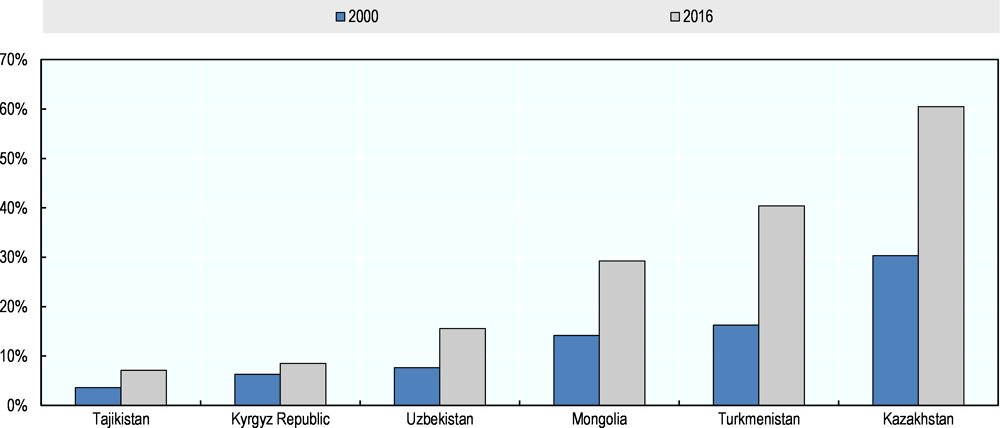

Hydrocarbons and hard minerals dominate Central Asia’s exports (Figure 1.4). Such commodities are especially important for Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Turkmenistan. Kazakhstan is one of the world’s top oil and mineral producers, and possesses world-class reserves in a wide variety of metals (ferrous, non-ferrous), precious minerals and hydrocarbons. Mongolia has one of the world’s most important copper mines and is rich in many other minerals including gold. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have large gas resources that are only partly exploited. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have important gold reserves, and the latter is an exporter of aluminium.2

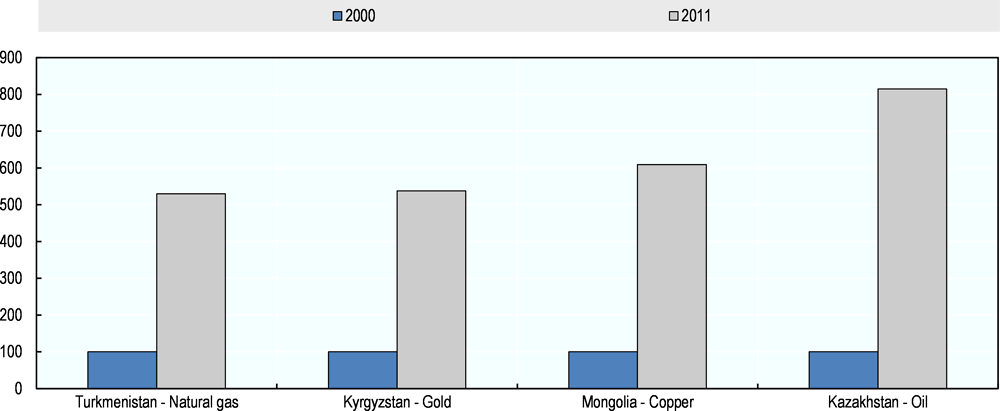

In the first decade of the century, commodity prices consistently rose in what most analysts call the “super-cycle”, largely driven by China’s rapid economic expansion. Even the global crisis of 2009 did not interrupt this trend for long. From 2000 to 2011 the price of gold (+463%), coal (+396%), copper (+386%), oil (+268%) and natural gas (+207%) (IMF, 2017[2]) all rose sharply. Central Asian countries’ exports of such goods rose extremely fast (Figure 1.5).

← 1. Turkmenistan's natural gas export rose from USD 850 mn to USD 4.5 bn, Kyrgyzstan's export of gold from USD 186 mn to USD 1 bn, Kazakhstan's exports of crude oil from USD 5.5 bn to USD 44.8 bn and Mongolia's copper export (considering 2001, as 2000 was virtually 0) from USD 162 mn to USD 987 mn.

Starting in 2012-13, prices began to fall as China’s economy slowed and so did the value of Central Asian exports and real GDP growth rates (see Figure 1.7).

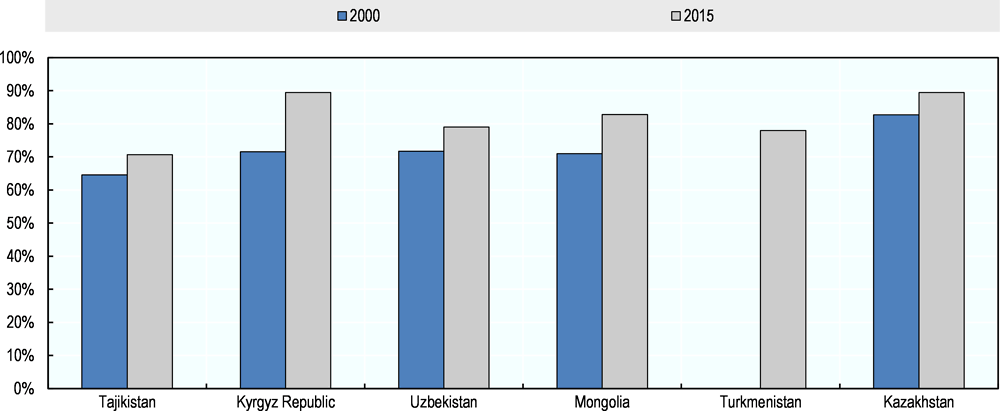

Economic growth was further affected by a fall in remittances. The remittances sent back to families by migrant workers constituted the other major source of growth during the period of high commodity prices. Low salaries and high unemployment prompted millions of workers to move, particularly to the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan: in 2015, the average monthly wage in Russia was roughly 4.5 times the average in Kyrgyzstan and 8.5 times the Tajikistan average; the corresponding figures for Kazakhstan were, respectively, 3.4 and 6.5 times (Ryazantsev, 2016[8]).

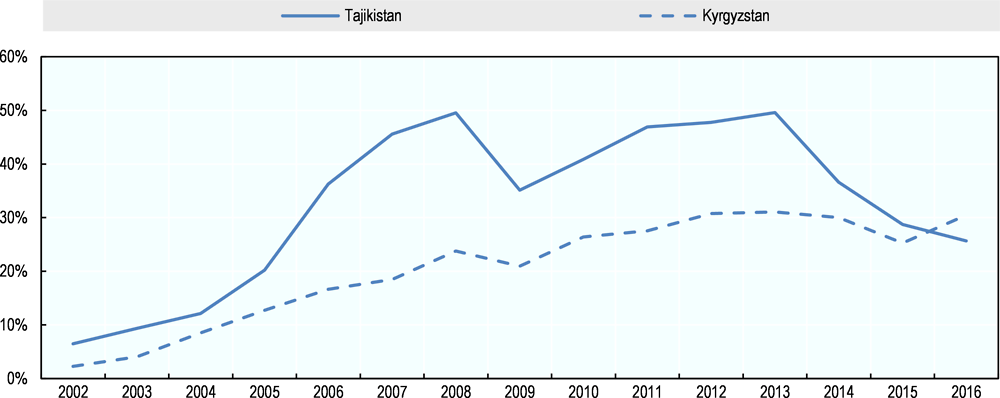

Indeed, the scale of remittances is such that for some Central Asian countries, the primary export commodity is really labour. The number of labour migrants from Central Asian countries has been estimated at 2.7-4.2 million, which is 10-16% of the economically active population of the region in 2010 (Ryazantsev, 2016[8]). Remittance flows are particularly important for the less resource-rich economies of the region – Uzbekistan (USD 2.3 billion in 2015), Kyrgyzstan (USD 2.0 billion) and Tajikistan (USD 1.8 billion). In relative terms, remittances were far less important in Uzbekistan (4.6% of GDP), than in Kyrgyzstan (25.7%) and Tajikistan3 (28.8%) (World Bank, 2017[1]).4

The value of remittances in USD increased from the early 2000s until 2013, when it fell sharply as a result of a 50% devaluation of the Russian rouble against the USD and the increasingly strict rules on migration introduced by the Russian Federation, especially for countries outside the Eurasian Economic Union (Figure 1.6).

Remittance flows have been economically beneficial but also involve costs

Labour migration has enabled countries with weak export capacities in goods and services to sustain domestic consumption and offset deficits elsewhere in the balance of payments. This is consistent with the Heckscher-Ohlin model of international trade, which holds that a country will export goods that are relatively intensive in the factors that it has in abundance and import goods that are intensive in its scarce factors (Ohlin, 1933[9]). There was, however, one important twist in the transition countries of Central Asia. Domestic conditions, infrastructure and institutions were such that even countries with an abundance of relatively low-cost labour could not move quickly to occupy niches as exporters of labour-intensive goods. Labour thus moved abroad to locations where production conditions were more favourable, both in tradable and non-tradable sectors.

Labour migration has helped to raise household incomes and reduce unemployment in the sending countries. If migrants return with professional skills acquired abroad, they could further benefit their home countries. This depends on the form of migration, however – for example, seasonal agricultural labourers are less likely to return with new skills than those who emigrate for a longer period and in more skill-intensive sectors. There are also opportunities for returning migrants to generate new activities: they often tend to be among their countries’ most entrepreneurial citizens. Unfortunately, in many countries, the framework conditions for entrepreneurship do not make it attractive for returnees to invest their remittances and build businesses – indeed, poor framework conditions at home are among the major causes of migration (Marat, 2009[10]; Malyuchenko, 2015[11]).5 The case study on Tajikistan that follows (Chapter 2) is concerned with policy changes and institutional reforms that can help improve these conditions and maximise the potential contribution of returning migrants to national economies.6

There are, however, important economic and social costs associated with such outflows of working-age people. The economies of the sending countries experience the so-called “missing-men” phenomenon, which means a lack of qualified male labour in rural areas, particularly during times of intensive field work. In addition, highly skilled workers also tend to leave. For example, from 1991 to 2005, the number of teachers with higher education in Tajikistan fell from 72 789 to 61 319, and the share of all teachers with higher education thus fell from 77% to 62% (IOM, 2006[12]).

Social costs for migrants and their sending communities may also be significant. First, migrants often live and work in very poor conditions, with little or no access to healthcare or other public services in host countries, where they often work in the informal sector. Second, there are the costs of family separation, which can be substantial (Malyuchenko, 2015[11]). For instance, IOM studies show that about one third of migrants’ wives were abandoned by their husbands due to the latter permanently settling in the host country (IOM, 2010[13]; IOM, 2009[14]).

For children, the impact of migration is mixed: remittances increase household income and may thus improve access to health services, education and nutrition, but absent fathers also place emotional and physical burdens on children, who often have to undertake more and heavier work. UNICEF (2012) highlights the negative impact on school performance associated with the reduction of parental control and care, as well as family break-up. These are all challenges sending countries struggle to address, since it is often the low levels of income and institutional development that prompt out-migration in the first place.

At a macro level, dependence on remittances implies a high degree of sensitivity to the performance of the receiving economies, particularly the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan in the case of Central Asia. Consequently, even the resource-poor countries of the region were hit hard by the sharp drop in commodities prices in 2014-15, a shift in the terms of trade that might otherwise have been expected to benefit them as importers of commodities. For example, in Tajikistan in 2013, 89% of remittances were denominated in roubles, amounting to 43% of GDP; weaker demand for Tajik labour in Russia and the depreciation of the rouble against the dollar meant that many businesses and citizens saw their purchasing power fall sharply. Moreover, citizens and businesses found themselves unable to service their debts, as Tajikistan has a strongly dollarised economy, with more than 80% of bank loans and deposits denominated in USD in 2014. The banking and financial crisis that followed in 2015 was in large part a result of this shock and is still hampering growth in the country (IMF, 2016[15]).

Exports are increasingly concentrated, both in terms of commodities and markets

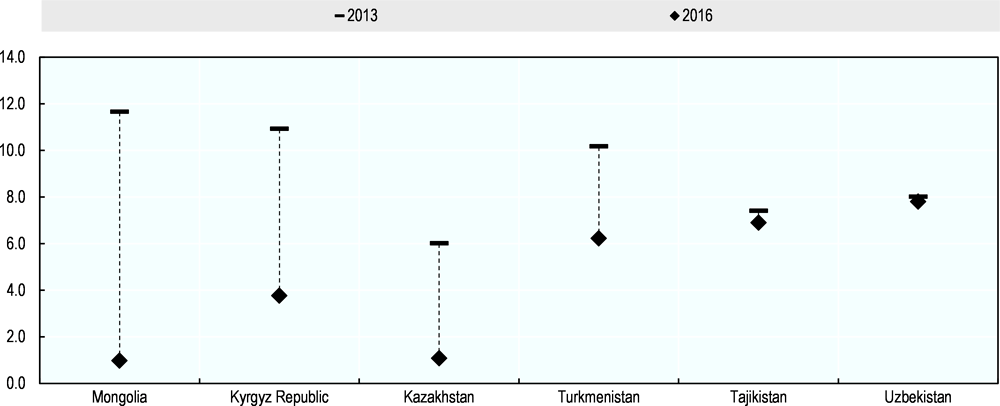

All the countries in the region, except Uzbekistan, have seen an increase in the concentration of their export baskets, as reflected in the Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index7 over the past 20 years, with fewer products accounting for a larger share of exports (UNCTAD, 2017[16]).8 Increasing concentration on a limited range of commodities which are often subject to large short-term price fluctuations (mainly hydrocarbons and minerals) entails important risks. For example, Mongolia experienced real GDP growth averaging 11% per year in 2010-14, but after the fall in commodity prices (particularly copper), growth dropped to 2.4% in 2015 and an estimated 1.6% in 2016, with public finances coming under strain as a result. The fall in commodity prices in 2014 slowed growth across the region, although official data for Tajikistan and Uzbekistan do not show much evidence of a slowdown (Figure 1.7). Other major global commodity exporters also experienced an economic slowdown; Chile and South Africa lost more than 2 percentage points of GDP growth between 2013 and 2016 (World Bank, 2017[1]).

Source: (IMF, 2017[2])

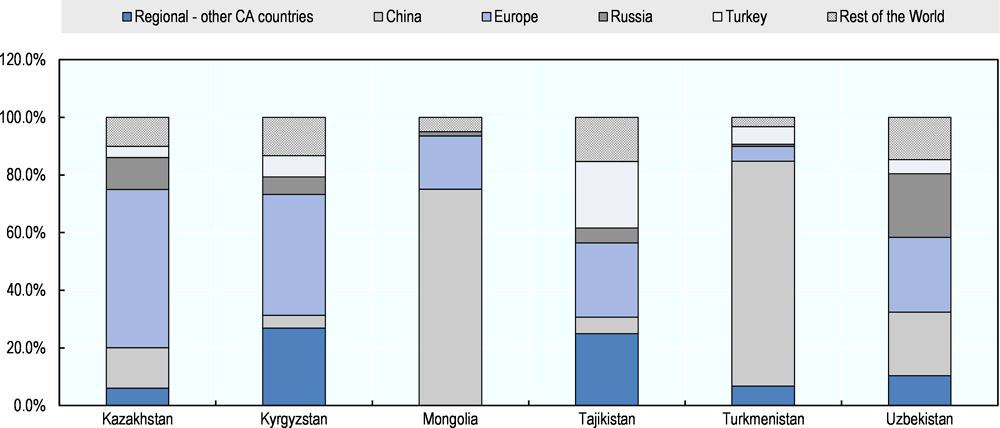

Moreover, the vulnerability of Central Asian countries extends to shocks affecting trade partners, as their exports are concentrated in a limited number of export markets. Landlocked geography and the “distance penalty” mean that a few neighbours almost exclusively make up the export markets for Central Asian economies (Figure 1.8).

Successful diversification should bring higher incomes and less volatile economic performance

Resource wealth has brought important benefits to Central Asia. The rapid growth of extraction sectors has led to higher incomes and, for most of the last two decades, better growth performance in those Central Asian countries endowed with rich hydrocarbon and hard mineral resources (World Bank, 2017[1]). Proper management of the flow of resources is crucial. A positive example is the National Fund of the Republic of Kazakhstan, with total assets amounting to USD 67 billion as of 2016 (Reuters, 2017[17]; Samruk Kazyna, 2016[18]). Created in 2000 as a stabilisation fund against the fluctuation of commodity prices, the fund manages the financial assets deriving from taxes on oil and gas companies as well as from its own investments. The assets are then accumulated in a government's account at the National Bank of Kazakhstan, with a guaranteed transfer to the national budget that is limited by a fiscal rule (OECD, 2016[19]).9 Among OECD economies, Chile (the Social and Economic Stabilisation Fund) and Norway (the Government Pension Fund Global) have successfully established such funds to manage natural-resource wealth (OECD, 2008[20]).

Nevertheless, such heavy reliance on exports of hydrocarbons and hard minerals entails significant costs and risks. A large body of empirical research suggests that countries endowed with great natural resource wealth tend to lag behind comparable countries in terms of real GDP growth in the long run. This has given rise to debate about a so-called “resource curse” or “paradox of plenty”.10 At macro level, resource dependence implies a high degree of vulnerability to external shocks, particularly where government revenues rely heavily on export income. More diversified economies also tend to be more resilient to shocks. Their output is less volatile, and lower output volatility is usually associated with higher economic growth in the long run (Ramey, 1995[21]). In the case of Kazakhstan, the OECD has recommended that the government should further diversify its economy to lower its vulnerability towards external shocks (OECD, 2012[22]; OECD, 2016[23]; OECD, 2017[24]). Other resource-rich Central Asian economies face similar challenges.

In addition, the pressures that resource wealth generates on non-resource tradables, particularly when resource booms drive up the exchange rate (the phenomenon known as the “Dutch disease”), can make it hard to generate high-productivity tradable activities outside the resource sector.11 This is a critical concern, because a large share of employment in Central Asian countries is concentrated in low-productivity sectors, while mining and hydrocarbons are capital intensive and employ relatively few workers. The extraction sector alone will never be able to generate high-productivity employment on a sufficient scale to assure broad-based prosperity – even with very aggressive assumptions about both future commodity prices and the potential to increase resource extraction. A dynamic, non-resource sector is therefore likely to be fundamental to inclusive growth: Central Asian countries need to generate high-productivity activities outside the resource sector.

Diversification is also relevant for the comparatively “resource-poor” countries of the region, since, as noted above, reliance on migrants’ remittances is also an unappealing long-term strategy. They can only escape their dependence on foreign labour markets by creating conditions to enable new tradable sectors and activities to emerge and existing ones to grow more quickly.

The importance of diversification is further confirmed if we look at personal income data. Studies leveraging large datasets covering 99 countries (ILO, UNIDO, and OECD) show that sectoral concentration follows a U-shaped pattern. Starting with a very concentrated economy, countries usually diversify to reach higher level of per capita income, only to concentrate again in the sectors with greater competitive advantage at a later stage of development (Imbs, 2003[25]). More recently, on the basis of data covering 178 countries from 1962 to 2010, Papageorgiou et al (2014) found that export diversification is associated with higher per capita incomes, lower output volatility, and higher economic stability (IMF, 2014[26]). This underscores the importance of further diversifying the export structures of Central Asian countries.

Diversification will require better governance, connectivity and framework conditions for business

Sound macroeconomic management – and, in particular, prudent management of resource revenues – will be critical to enabling Central Asian states to diversify their economies and the sources of growth. However, macroeconomic discipline alone will not be enough; policy intervention may also be needed to address co-ordination failures between economic actors, which are leading to underinvestment in infrastructure, modern technologies and human resources (Rodrik, 1996[27]; Rodriguez-Clare, 2005[28]).12 Reforms in at least three other areas will be essential:

-

Improving the quality of public governance is a priority. Resource-led development is extremely demanding on national institutions, because of the need to manage the volatile revenues associated with the exploitation of natural resources fairly and productively (IBRD / World Bank, 2014[29]). As a rule, weaknesses in the institutional environment, such as corruption, weak property rights or arbitrary taxation and regulation, have a disproportionate effect on younger firms and sectors, and on small firms. Established incumbents often have the political and financial resources to cope with – or even, in some cases, to profit from – such things, while those engaged in new activities usually lack such resources and, in any case, face higher levels of risk and uncertainty than incumbents. Higher-quality institutions, coupled with proper planning, can turn the “resource curse” into an opportunity (OECD, 2011[30]).

-

Boosting connectivity to support trade and export diversification. The high cost of access to large foreign markets is a significant impediment to the emergence of new activities in much of Central Asia. This reflects both infrastructure challenges and the often high cost of doing business across borders, which results from tariffs, border procedures and non-tariff barriers. Poor trade and connectivity within the region lead to fragmented markets, making it hard for producers of non-resource tradables to achieve critical mass and to realise economies of scale, while poor connections to the rest of the world undermine access to the largest markets and inhibit integration into global value chains.

-

Enhancing the business environment is an effective way to support the diversification of economic activity (Lederman, 2012[31]). In particular, the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in sectors such as manufacturing, trade and services can also help economies to diversify away from natural resource sectors in which large companies are over-represented (OECD, 2016[32]). In a stable and predictable environment, businesses can operate with longer time horizons, and face reduced risks in trying innovative activities. In the absence of such conditions, rational agents will focus on short-term gains, and there is likely to be little investment in any activity that does not generate very rapid returns (OECD, 2006[33]).

Improving the quality of public governance

Government effectiveness across much of Central Asia is relatively low

A substantial body of research suggests that resource dependence can have important implications for governance, which can, in turn, constrain prospects for diversification. Competition for natural resource rents across different levels of government can make the whole political system malfunction, as there is usually less public scrutiny and political accountability (Gelb, 2010[34]). Moreover, in a situation of limited institutional control, the struggle among elite groups to obtain the most from resource windfalls can cause an increase in fiscal redistribution strong enough to offset any increase in the raw rate of return from resource windfalls, ultimately hampering growth (Tornell, 1999[35]).

When a state’s production and export profile is highly concentrated, the characteristics of its leading sector can significantly influence its institutions, and this is especially evident in countries that specialise in extractive sectors (Chaudry, 1989[36]; Shafer, 1994[37]). Hydrocarbons and mining are typically dominated by a small number of players, with high barriers to entry and exit, and a high degree of asset specificity. Faced with the need to govern these sectors, the state develops special, highly centralised institutions and practices to capture resource rents and deal with the leading sector. The centralised, sector-specific character of the state to some degree mirrors that of the economy. Many oil-producing countries, for example, have created specialised tax agencies to tap (and spend) the oil rents and specialised agencies to monitor, regulate, and promote the activities of big oil companies.13 At the same time, they often fail to strengthen the institutions needed to promote other sector, or to create a business environment conducive to experimentation and entrepreneurship.

This point is extremely important in the larger resource curse debate, as some research suggests that state ownership rather than resource wealth lies at the root of resource exporters’ apparently chronic under-performance (Auty, 2004[38]; Ross, 1999[39]; Jones Luong, 2004[40]). State ownership of resource industries may soften states’ budget constraints and encourage fiscal indiscipline. In any case, state-owned minerals producers are likely to be less efficient and less transparent, and also to be subject to more political interference.14

In addition, the expropriability of resource rents creates a climate of uncertainty that discourages foreign investment. For instance in Kazakhstan, the new Mining Code includes one notable drawback. The state’s pre-emptive right to mineral resources (“strategic deposits”) was understood in the past to be of significant concern to potential and existing foreign investors in Kazakhstan, particularly in the field of solid minerals. The list of eligible minerals and their respective amounts is fairly exhaustive in terms of Kazakhstan’s resources. Even under the new mining code, some observers fear that any significant deposit would be potentially eligible for inclusion in the “strategic” category.

Institutional design and governance are also a product of domestic choices: they are not wholly determined by factors intrinsic to the sector (Jones Luong, 2004[40]). Nevertheless, the predominance of state ownership in major hydrocarbon and minerals sectors across the world over the last 40-50 years – despite wide variation in the political circumstances of mineral-exporting states – suggests that the characteristics of the sector itself are important in structuring the choices politicians make in response to domestic political opportunities and constraints. These choices, in turn, affect the prospects for developing governance models that are less centralised and more responsive to the needs of a wide range of interests and sectors. In the context of Central Asia, it is important to note that the impact of remittance flows on institutions is likely to be very different, since labour remittances, in contrast to oil rents, typically bypass both state institutions and formal banking systems. Remittances can engender an independent and affluent private sector but also provide opportunities for the government to tap remitted funds indirectly through import duties and other restrictive measures. In either case, the risk is that “extractive institutions and their ancillary legal, fiscal, and information-gathering bureaucracies” may atrophy (Chaudry, 1989[36]).

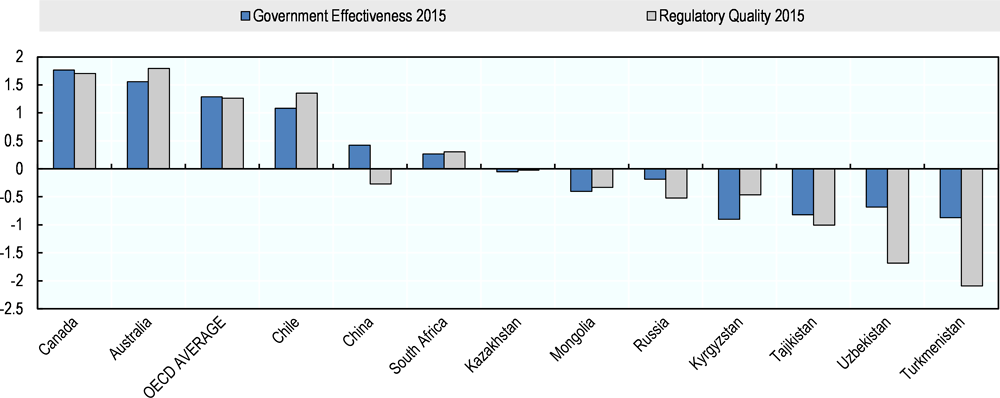

Whatever one makes of the resource curse arguments, Central Asian states do broadly conform to the general patterns found in the literature on resource- and remittance-dependent economies. Businesses and international indexes consistently report that Central Asian countries have weak institutions. For instance, they score well below the OECD average in the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Indicators of institutional quality, including resource-rich countries such as Canada, Chile and Norway (World Economic Forum, 2017[41]). Central Asian countries also lag behind in quality of governance, ranking in the bottom 35% in the World Bank Governance Indicators. Assessment of Central Asia’s governance points in particular towards:

-

low government effectiveness, which reflects the perceived quality of public services, civil service, policy formulation and implementation

-

low regulatory quality, which reflects the government’s ability to formulate and implement policies for private sector development (Figure 1.9).

Note: The Worldwide Governance Indicators, published by the World Bank on a yearly basis, estimate the quality of governance in over 200 countries. They cover six dimensions of governance, ranking their performance from -2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong). The 6 aggregate indicators are based on several hundred underlying variables obtained from 31 different data sources

Source: (World Bank, 2017[42])

Such evidence of institutional weakness implies not just a need for reforms to strengthen public-sector integrity or government effectiveness, which are major challenges in themselves, but also a need to create new capacities and institutions that are better suited to the needs of an emerging non-resource sector. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) refers to a “modern industrial and service economy” as the goal of diversification (ADB, 2013[43]). Such institutions, in fields as diverse as export-promotion and human-capital development, are the focus of discussion in the chapters that follow.

Countries in the region are strengthening their institutional capacities at different rates. Governments have had difficulty in implementing approved plans (Box 1.1). Ministries often have to operate with relatively limited resources and insufficient institutional capacity. They often lack reliable, accurate micro-level data which makes it difficult to structure precise Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for implementation. The result of this is that governments and other public agencies produce ambitious strategic plans, which usually fall short at implementation. The Regional Civil Service Hub in Astana, a co-operation platform aimed at proposing partnerships, capacity building and peer-to-peer learning among governments in the region, is one good initiative in this area (RHCS, 2017[44]). Participation by Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan – and more active participation by Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Mongolia – in this hub might help tackle this issue.

The review of the Central Administration of Kazakhstan, carried out by the OECD in 2014, focused on the capacity of central government and line ministries in Kazakhstan to implement national objectives and priorities. To this end, the review offered recommendations on how to re-assess the role and capacity of the ministries; review the function and roles of central agencies; promote transparency in policy making, monitoring and evaluation; improve horizontal co-ordination at central level; and improve human resource management and accountability for management results.

One of the main policy recommendations was to give ministries and agencies greater autonomy to reduce centralisation and the cost of bureaucracy. The OECD recommended enhancing the role and capacities of ministries to generate strategic policy documents, perform policy analysis, and deliver government priorities. As part of the Strategy Kazakhstan-2050, Kazakhstan aims to improve and streamline the system of state planning and forecasting, and further professionalise its civil service.

Kazakhstan already had a law on Local Government (2001) including the division of power and responsibilities between the central and local government but problems in implementing the law stopped the transition. Decentralisation is also at the core of the Strategy Kazakhstan-2050, and in particular how to divide decision-making powers between central government and regions. To overcome most of the issues, the OECD suggested a long-term development of human resources to prepare staff in all the junctions of this model. This would also enhance service delivery at a local level, with local authorities being closer to citizens.

Source: (OECD, 2014[45]; Government of Kazakhstan, 2017[46])

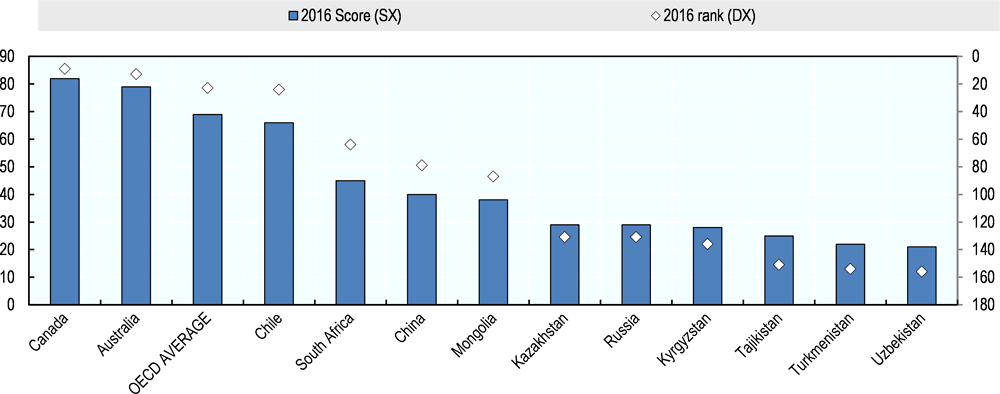

Corruption is perhaps the most important governance challenge today

Public sector corruption and business integrity are major issues for Central Asian countries, all of which except Mongolia are found in the bottom quarter of the Transparency International Corruption Index. Although the degree of corruption varies across the region, all countries are ranked below 40 (on a scale of 0-100) (Figure 1.10). This is far below the OECD average and in particular below several OECD countries that are successfully managing vast natural resources, including Australia, Canada and Chile (Transparency International, 2016[47]).

The OECD has worked extensively with governments in the region to tackle corruption. In particular, in 2003 the OECD Anti-Corruption Network (ACN) for Eastern Europe and Central Asia launched the Istanbul Anti-Corruption Action Plan, a regional peer review programme focusing on Central Asia and Eastern Europe. The plan offers country reviews and monitors follow-up on recommendations concerning anti-corruption legislation. It targets nine countries, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. During 2003-05, all of the Central Asian countries underwent baseline reviews based on anti-corruption standards established by the United Nations, the OECD and the Council of Europe. Since this baseline review, they have undergone three further rounds of monitoring of the implementation of anti-corruption reforms and their impact on levels of corruption.

The 2013-15 monitoring round demonstrated that the region has made some progress in preventing and punishing corrupt practices. Yet considerable challenges remain with respect to anti-corruption policies and institutions, the criminalisation of corruption and law-enforcement, and measures to prevent corruption in public administration and the business sector. The lack of specific timelines and measurable indicators to assess the effectiveness and impact of the reforms and ineffective law enforcement are still holding the countries back (OECD, 2016[32]).

Competition in many markets is weak

To allow businesses to thrive, competition law and policy and should create a level playing field, especially between state-owned enterprises (SOEs), large private companies (foreign and domestically owned), and SMEs. The pressure of competitors is one of the strongest incentives for a company to try to allocate resources efficiently and to innovate. This is particularly important in a region where incumbents and SOEs often benefit from uncompetitive advantages (Box 1.2).

In 2016, Kazakhstan was the first country in the region to undergo its OECD competition law and policy peer review, which was attended by almost 90 delegations from around the world. In that context, the OECD provided key recommendations to the government of Kazakhstan on enforcement prioritisation, tools to detect collusive practices, analysis of mergers, procedural rules to increase overall transparency of proceedings and how to align to Eurasia Economic Union (EEU) standards.

The Government of Kazakhstan was advised to reduce the number of state monopolies, since many of the commercial activities considered to be state monopolies and conducted by state enterprises under tight regulation could be offered competitively by private companies. It was recommended, wherever possible, to subject these monopolies to a critical assessment and open them to private actors and competition.

The OECD also suggested reforms regarding control over dominant enterprises. In particular, the Kazakh government should shift from the current “State Register for Dominant Undertakings” (based exclusively on market share analysis and not constantly updated) to a case-by-case analysis of an undertaking’s market position only if there is a reason to suspect abusive behavior. Analyses have to include not only the market share criteria but barriers to entry, the nature of the products, competitors and competition on the market, technological developments, the market phase and history, and foreseeable developments in the market.

Recommendations on tackling the abuse of dominant positions concentrated on shifting focus from price control to abusive practices that foreclose markets and erect barriers to entry. The OECD recommended focusing action on the reasons for non-competitive market structures, which would have much more lasting effects than interventions directed at prices.

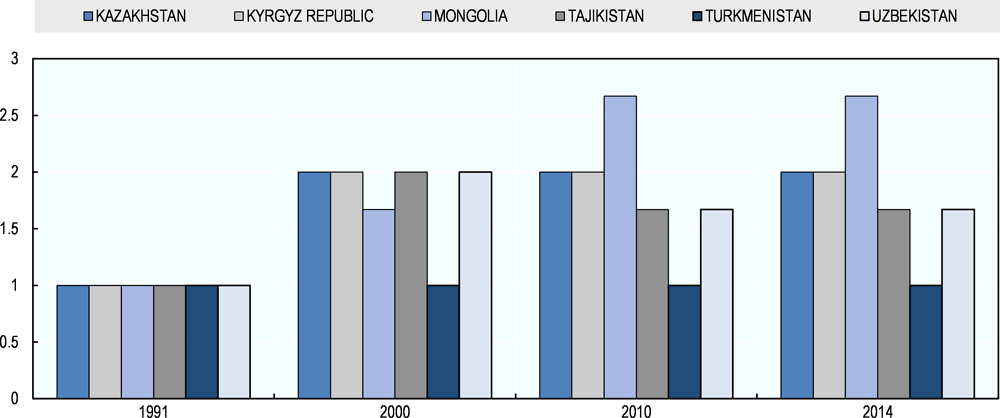

As seen in Figure 1.10, the other Central Asian countries share the need to increase competition. After a first wave of legislation in the 1990s the indicators show that only Mongolia has progressed in its competition law since 2000.

Source: (OECD, 2016[49]; EBRD, 2017[48])

The EBRD has developed an indicator that looks at the quality of competition policy and its enforcement, with scores ranging from 1 (no competition legalisation or institution) to 4+ (best standards and effective enforcement of competition policy are applied).15 Central Asian countries started to introduce competition legislation after independence, with different patterns (Figure 1.11): Mongolia currently leads the way, with a score of 2.7, followed by Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan at 2, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan at 1.7 and Turkmenistan still at 1 (EBRD, 2017[48]).

Source: (EBRD, 2017[48])

Boosting connectivity

With the development of global value chains (GVCs), countries in search of diversification today cannot hope to develop fully integrated industries from scratch (e.g. in the automotive or computer sector) that can compete with efficient GVCs. They need to find particular tasks within GVCs in which they enjoy a competitive advantage and work to create the conditions for the development of those activities (Baldwin and Taglioni, 2011[50]) (Baldwin, 2016[51]). Import substitution industrialisation policies, which tried to replace imports with domestic products by diversifying the domestic production structure and imposing high trade barriers, have proved to be an inefficient strategy (Sachs, 1995[52]). This is true even of some large emerging economies and even more so of smaller countries, like those in Central Asia, where limited market size means that any real move towards diversification needs to be outward oriented. Improving transport and information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure, while reducing the soft barriers to trade (e.g. inefficient customs) will reduce trade costs, make countries more attractive as regional and global value-chain participants, and ultimately support the diversification of Central Asian economies (Pomfret, 2014[53]).

Connectivity is one of the great challenges facing the countries of Central Asia. Despite the region’s historical role as a centre of global trade, it is largely peripheral to global trade flows today. The region’s integration is limited by low density of settlement and economic activity, infrastructure bottlenecks, and long distances to major markets, as well as numerous regulatory and policy barriers to cross-border flows of trade and investment. Flows of trade, investment and people – both within the region and with the rest of the world – are far smaller than one might expect. Moreover, the connectivity framework that does exist is largely a product of the region’s current reliance on exports of primary products, particularly agricultural commodities, hydrocarbons, metals and rare earth minerals. That is not surprising, but this may need to change if the Central Asian countries wish to diversify their economic structures so as to rely less on the primary sector.

Transport infrastructure in the region is far from adequate

Infrastructure investment needs in Central Asia16 are estimated at USD 492 billion over the period 2016-30, implying an increase in spending from the current 4% to 6.8% of the region’s GDP (ADB, 2017[54]). Central Asian countries have relatively poor roads, which undermine the connectivity potential of the region. Of the roads identified by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) for the realisation of the Asian Highway, 23% in Uzbekistan lack asphalt or cement concrete, and this figure rises to 48% in Tajikistan, 54% in Kazakhstan, 60% in Mongolia, 60% in Kyrgyzstan and 97% in Turkmenistan (UNESCAP, 2017[55]). This is also reflected in a high level of infrastructure risk (the probability of losing income because of deficiencies in transport, power and communication facilities). On a scale from 0 (low risk) to 100 (high risk), the average value of infrastructure risk in Central Asia has been estimated by the Economist Intelligence Unit at 67,17 compared with 19 for OECD member countries (EIU, 2016[56]).

Governments in Central Asia, with the support of neighbouring countries and multilateral financing organisations, have invested in the improvement of transport infrastructure such as railways and roads in recent years. Central Asia is a key area for China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI; Box 1.3). In 2008, the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) completed the upgrade of the road linking Bishkek and Almaty, thus making it easier and safer to transport goods between the two cities. The governments of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Iran, with the support of organisations such as the ADB and the Islamic Development Bank, have opened an economic corridor linking Uzen in Kazakhstan with Bereket and Etrek in Turkmenistan and eventually stretching up to Gorgan in Iran, thanks to the railway opened in 2014.

This ambitious project, announced in 2013 by China’s President Xi Jinping, aims to increase China’s weight in the global economy by facilitating the shipment of Chinese goods to destination markets, promoting China’s energy security and spreading Chinese investments in foreign countries.

Several billion dollars have already been invested in Central Asia within the OBOR initiative. In 2015, the Chongqing-Duisburg railway (inaugurated in 2011) offered a regular thrice-weekly service, enabling cargo to travel between China and Europe through Kazakhstan in only 16 days, instead of the 36 days required by maritime routes. China and Kazakhstan are also investing in a second rail link through Kazakhstan to Almaty, hence opening the prospect of another route to Europe south of the Caspian Sea. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is also important as it will make Kashgar into a hub for Central Asia once the Kashgar-Osh-Uzbekistan railway has been built.

In 2013, the construction of the Dushanbe-Chanak highway was completed, with 80% of the financing coming from the Chinese Development Bank (Cooley, 2016[57]). This last project not only boosts Chinese exports but also increases regional connectivity by linking major Tajik cities such as Dushanbe and Khujand with neighbouring Uzbekistan.

Source: (CGTN, 2017[58]; Cooley, 2016[57]; World Bank, 2016[59])

Applying the Global Freight Model of the OECD International Transport Forum (ITF) to Central Asian countries could offer policy-makers unique insights into the costs, benefits and trade-offs of various options when it comes to transport infrastructure, enabling them to make more informed choices.

More can be done to increase digital connectivity

Central Asia has experienced a sharp increase in the penetration of ICT in recent years. The average number of mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people was 124 in 2015, in line with levels in the United States (118), the European Union (123) and Japan (125) (World Bank, 2017[1]). These figures should be viewed with caution, however, as the very high number of mobile subscriptions is also caused by poor landline services and multiple contracts per person, as competing suppliers have different least-cost services. However, Central Asia is enhancing ICT connectivity and performance thanks to the construction of new infrastructure, such as the cable installed in 2009 between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, and the planned Trans-Eurasian Information Super Highway (TASIM) connecting Frankfurt to Hong Kong and passing through Central Asia.

However, Central Asian countries still have few trans-border fibre optic links. This limits their connection to global communication networks, reduces the availability of internet bandwidth for local users and increases the costs they face. The number of fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 people in Central Asia is comparatively low. While the European Union and the United States had 31.8 and 31.5 fixed broadband subscriptions respectively per 100 people in 2015, there were just 13.1 in Kazakhstan, 7.1 in Mongolia, 3.7 in Kyrgyzstan, 3.6 in Uzbekistan, and around 0.1 in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan (World Bank, 2017[1]).

Trade policies can strengthen both connectivity and competition

Membership of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) implies a harmonisation of customs regulation, standards, certification and tariffs that help countries’ trade policies to become more open and predictable. Most of the countries in the region have become members of the WTO in the past 20 years: Mongolia in 1997, Kyrgyzstan in 1998, Tajikistan in 2013 and Kazakhstan in 2015. Uzbekistan has an observer status with an accession working party that last met in 2005. Turkmenistan has also shown some interest in the possibility of joining, setting up a government commission in 2013 to analyse the possibility of accession. In addition, the accession of China in 2001 and of the Russian Federation in 2012 made membership more valuable for Central Asian countries.

Access to electricity is the 7th Sustainable Development Goal proposed by the UN, to which all Central Asian governments have committed, and a core pre-condition to unlock economic development and diversification of the economy. Central Asia’s energy infrastructure was well integrated under the Soviet Union, thanks to the Unified Energy System (UES). After the breakup of the USSR, the UES weakened and became fragmented.

However, in recent times there has been a growing consensus in Central Asia about the need to recreate such a unified power grid. After high-level meetings in May 2017, Uzbekistan decided to allow Turkmen electricity exports to flow again across its territory towards Kyrgyzstan and southern Kazakhstan (and, maybe, in winter months, also to Tajikistan). This is a breakthrough, since it partially re-establishes a Central Asian unified energy system. Moreover, the recently-inaugurated project CASA-1000, which is to export electricity produced by hydropower plants in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Pakistan and Afghanistan, is expected to be finalised soon thanks to the financial support of several international financial institutions. A high-level inter-governmental council has been established to make the 1 222 km CASA-1000 transmission project happen.

Source: (CASA-1000, 2017[60])

Regional integration has also increased forward through the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which includes two Central Asian states among its members, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Tajikistan and Mongolia are currently discussing the possibility of joining. The benefits of EEU accession are still being assessed for current members and potential new entrants (Box 1.5).

The establishment of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) in 2014 (following the formation of a customs union (CU) comprising Belarus, the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan in 2010) partly addresses the need to smooth customs procedures and facilitate the passage of cargo across borders. The EEU’s goal is to create a common space for the free movement of goods, services, capital and labour, while at the same time promoting co-ordination among member states in sectors such as agriculture, energy and fiscal policy. The EEU currently has five member states: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia

The EEU’s efforts to promote competitiveness through measures such as the unification of customs procedures, the reduction of customs duties and the removal of non-tariff barriers are intended to promote trade among member states. Before the introduction of the customs union, the average border crossing time between Kazakhstan and Russia was about 7 hours, but it has since fallen to only 2 hours.

Nevertheless, trade facilitation in the framework of the EEU is an ongoing process that still faces several challenges. Some of the measures introduced to foster trade among CU/EEU member states seemed to have a negative effect on trade dynamics between these states and non-member countries. For instance, average border crossing time for cargos from non-CU countries to Kazakhstan rose from 8 hours before the introduction of the CU to 21 hours afterwards. In addition, the common external tariff means some partners have had to adopt higher tariff levels. However, the impact of this will abate somewhat as WTO-mandated annual tariff reductions are implemented. There have also been conflicts among EEU members concerning the imposition of ad hoc restrictions and non-tariff barriers that disadvantage them.

Furthermore, the EEU should foster the creation of new export possibilities for local enterprises within its common space, since today’s export structure remains unidirectional. In 2015, exports to Russia represented 89.6% of Kazakhstan’s exports towards EEU member countries, and this figure rises to 94.6% for Armenia and 96.1% for Belarus. Mutual trade between EEU member states as a percentage of their total foreign trade has increased from 12.3% in 2014 to 13.5% in 2015.

Given the limited size of Central Asian domestic markets, regional trade integration may facilitate enterprise growth and promote the development of manufacturing sectors.

Experience suggests that increased market access and liberalisation should progress gradually, giving Central Asian governments some scope to help local companies to adjust during the first stages of integration. The protection should be limited in scope and with a specific timeframe for the subsidies to begin and end, to limit market distortion once private enterprises become big enough to compete in the enlarged common market. In designing such transitional assistance, policy-makers should aim to reduce the costs of structural change rather than – as is too often the case – to try to forestall it. Evidence shows that defensive policies are usually driven by short-term interest and are more likely to be successful if they have precise conditionality and a clear exit strategy (Warwick, 2013[63]).

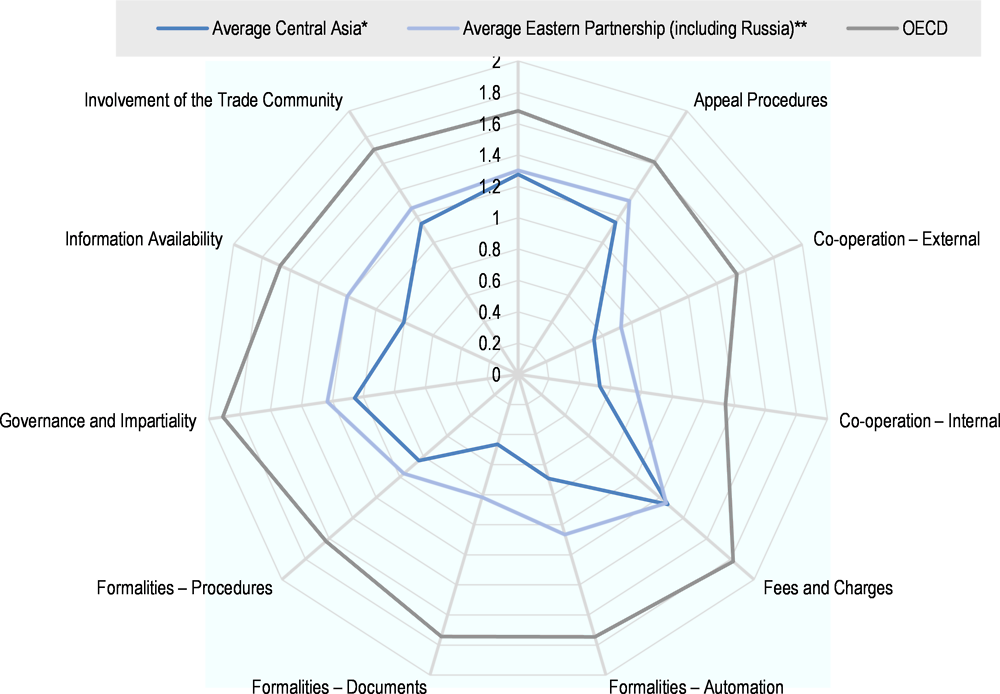

Central Asian countries still face difficulties when it comes to trading across borders. They record low scores on many dimensions of the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (TFIs). The TFIs offer a clear picture of the specific issues faced by Central Asian countries along 11 dimensions, offering a synthetic quantitative representation of inherently qualitative data (OECD, 2017[64]).

This assessment suggests that Central Asian countries need to prioritise:

-

simplification of trade documents; harmonisation in accordance with international standards; acceptance of copies (“Formalities – Documents”);

-

streamlining of border controls; single submission points for all required documentation - single windows; post-clearance audits; authorised economic operators (“Formalities – Procedures”);

-

governance and operations of customs: customs structures and functions; accountability; ethics policy (“Governance and Impartiality”).

1. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan.

2. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, the Russian Federation.

Source: (OECD, 2017[64])

Enhancing the business environment

A general measure of the quality of the business environment in Central Asia is provided by the World Bank’s Doing Business reports. Despite overall progress across the region in recent years, the most recent data reveal striking contrasts, with Kazakhstan ranking 35th (just below Japan), Mongolia 64th (close to Chile, 57th) and Kyrgyzstan 75th (just below South Africa); the latter two both fell back around 10 positions in 2017, while Uzbekistan is stable at 87th and Tajikistan rose 4 positions to 128th. There are also divergences across indicators. For example, procedures to start a business in the region are relatively easy and close to the best in the world, especially with the development of online procedures and one-stop shops in Central Asia, while performance on paying taxes varies widely, with Kazakhstan and Mongolia scoring far better in this respect (World Bank, 2016[59]).

Another measure of the quality of the business environment in Central Asian economies is offered by the position of SMEs. SMEs tend to suffer more from business climate issues than larger firms. They can less afford to bear the costs arising from poor enforcements of contracts, burdensome regulations, non-competitive procurement practices, and frequent inspections, which often serve as opportunities for corruption (OECD, 2014[65]; 2015[66]; 2015[67]). This may also limit economic diversification and the attraction of foreign capital. For example, Kazakhstan is moving forward on addressing some of these issues (Box 1.6).

In 2012 the OECD published its first Investment Policy Review of Kazakhstan, based on the OECD Policy Framework for Investment and focusing on the critical policy objective of diversifying the economy.

In the review, the OECD recommended increasing support to SMEs; in particular regarding access to finance and human capital development, as well as investment and export promotion. Moreover, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises were leveraged to address major issues regarding effective corporate governance and business ethics, including disclosure requirements of environmental and other non-financial performances. An important point raised in the review was that in all these policy areas the way in which the decisions are implemented is crucial in shaping their outcome.

In 2017 Kazakhstan was invited by the OECD to become adherent to the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises and its investment policy was reviewed again. It emerged how Kazakhstan's strong performance in terms of economic growth has been supported by its continuous efforts to liberalise and simplify investment regulation which helped spur capital inflows. Again, the main recommendation was to continue on the path to diversification, away from the over-reliance on natural resources (oil and gas sector generates as much as 30% of GDP currently).

Source: (OECD, 2012[22]; OECD, 2017[24])

In Central Asia, the contribution of SMEs to the economy is comparatively low, albeit with a good deal of variation between countries. They represent more than 90% of total businesses but their contribution to GDP is only between 25% and 41%, except in Uzbekistan, which is closer to OECD average of around 55%. They employ 78% of the workforce in Uzbekistan but only 38% in Kazakhstan. SMEs are mostly concentrated in low-value added sectors, especially agriculture and trade. Because of this concentration, they make a limited contribution to exports, while natural resources exported by large companies represent the bulk of exports in the region. In addition, as will be seen in Chapter 3, they often face particular barriers when it comes to accessing foreign markets.

Strategic approaches to industrial policy can be used to support SME development. These can be categorised as either comparative advantage-following or comparative advantage-developing, and according to whether the country or industry is in catch-up mode or at the frontier. Subsequently, tailored instruments of industrial policy could be selected to perform “softer” interventions, bringing industry and government together in setting strategic priorities, improve business networking opportunities and improve productivity. A crucial condition of the success of such an approach would be the planning for clear monitoring and evaluation from the very first conception of the industrial policies (Warwick, 2013[63]).

SMEs represent important untapped potential for economic diversification. They are a key engine of economic growth, generating output, trade, employment and productivity gains (OECD, 2000[68]). In OECD economies, they represent 99% of companies and from 50% to 60% of value added, and they provide more than 70% of jobs (OECD, 2016[69]). In resource-rich countries such as Australia, Canada, Chile and Norway, they also represent more than 99.75% of companies, around 60% of value added and close to 80% of jobs (OECD, 2016[69]). In the private sector they are important contributors to trade, as they generate more than half of the valued added in international trade in OECD countries, either as direct exporters or as suppliers to multinational companies (MNCs).

Recent OECD work suggests that as SMEs start up and grow, skills, access to financial resources and internationalisation are among the most critical challenges they face (OECD, 2017[70]). Governments have a key role to play in helping SMEs overcome such barriers. OECD governments are active in supporting SME development through dedicated institutions, such as SME agencies, a wide range of programmes targeted to SMEs and public-private dialogue mechanisms (OECD, 2017[71]).

The OECD has worked extensively in Central Asia to advise governments on policies to support SMEs and address co-ordination failures, focusing on access to finance, human internationalisation, and skills and human capital. The next chapters provide eight country-specific case studies that build on three years of OECD work with the governments of the region.

Access to finance: SMEs in most Central Asian countries report difficulties in accessing finance as a major obstacle for doing business. Bank credit is the main source of external funding for SMEs in Central Asia and the focus of most of the difficulties faced by SMEs. Other sources of financing are still underdeveloped, including microcredit, credit co-operatives, venture capital and asset-based financing instruments. Both supply and demand issues hamper access to finance for SMEs. On the demand side, SMEs are exposed to high interest rates, stringent and systematic collateral requirements, and cumbersome procedures to obtain a loan. On the supply side, banks regularly mention the poor financial literacy of SMEs as an important obstacle (OECD, 2013[72]; 2016[73]). The case studies in Chapter 2 will look at:

-

Mongolia: enhancing SMEs’ access to finance

-

Tajikistan: facilitating the productive use of remittances and supporting return migrant entrepreneurship

-

Kyrgyzstan: improving supply-chain financing in agriculture.

Business internationalisation in Central Asia is hindered by connectivity issues inherent to the region. Inadequate hard and soft infrastructure hamper access to foreign markets and SMEs bear relatively higher transport costs as they lack economies of scale, cannot develop their own infrastructure network, and are more affected by complex trade and customs procedures (OECD, 2009[74]). Exporting SMEs also report insufficient knowledge of foreign markets, a lack of advisory services, especially on certification and standards, and insufficient financial support to export. In an increasingly connected world, SMEs could also further participate in GVCs by building linkages with MNCs. The case studies in Chapter 3 will cover:

-

Uzbekistan: improving SMEs export promotion

-

Kyrgyzstan: revamping the investment promotion system

-

Tajikistan: enhancing export policies in agriculture.

Skills: SMEs in Central Asia frequently cite an inadequately educated workforce as an obstacle to development. They have difficulty identifying, recruiting and training workers, in part because of limited connections between the private sector and education institutions. The available workforce does not meet their skill needs, both in terms of general business skills and specific occupational competencies. The relevance and quality of education and training opportunities to develop skills appear to be limited, leading SMEs to focus mostly on-the-job-training (EBRD, 2017[75]; OECD, 2016[76]). The case studies in Chapter 4 focus on:

-

Kazakhstan: public-private co-operation in defining occupational standards

-

Kyrgyzstan: implementing reforms of workplace training.

References

[4] Abramovitz, M. (1986), “Catching up, forging ahead, and failing behind”, The Journal of Economic History, pp. 385-406.

[43] ADB (2013), Asia's economic transformation: Where to, How, and How Fast?, Asian Develpment Bank.

[54] ADB (2017), Meeting Asia's infrastructure needs, ADB Publishing.

[38] Auty, R. (2004), Patterns of Rent-Extraction and Deployment in Developing Countries: Implications for Governance, Economic Policy and Performance.

[50] Baldwin, R. and D. Taglioni (2011), “Gravity chains: estimating bilateral trade flows when parts and components trade is important”, NBER Working Paper No. 16672.

[51] Baldwin, R. (2016), The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization, Harvard University Press.

[61] CAREC (2012), Corridor performance measurement and monitoring annual report 2012, Asian Development Bank.

[60] CASA-1000 (2017), CASA-1000.org, http://www.casa-1000.org/MainPages/CASAAbout.php#objective.

[58] CGTN (2017), CGTN news, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d63544d3363544d/share_p.html.

[36] Chaudry, K. (1989), The Price of Wealth: Business and State in Labour Remittance and Oil Economies, International Organisation.

[57] Cooley, A. (2016), The Emerging Political Economy of OBOR, Center for Strategic & International Studies.

[48] EBRD (2017), Forecasts, macro data, transition indicators, http://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/economic-research-and-data/data/forecasts-macro-data-transition-indicators.html.

[75] EBRD (2017), EBRD Transition Report 2016-2017, EBRD.

[56] EIU (2016), One Belt, One Road: an economic roadmap, EIU.

[34] Gelb, A. (2010), Economic Diversification in Resource Rich Countries, IMF.

[46] Government of Kazakhstan (2017), Strategy Kazakhstan 2050, https://strategy2050.kz/en/multilanguage/.

[29] IBRD / World Bank (2014), Diversified development - making the most of natural resources in Eurasia, The World Bank.

[25] Imbs, J. (2003), “Stages of diversification”, American Economic Review, pp. 63-86.

[6] IMF (2014), 25 Years of Transition, IMF.

[26] IMF (2014), Sustaining long-run Growth and Macro-Economic Stability in Low-Income Countries, IMF Policy Paper.

[15] IMF (2016), Republic of Tajikistan - Financial System stability assessment.

[2] IMF (2017), IMF World Economic Outlook - April 2017, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2017/01/weodata/index.aspx.

[12] IOM (2006), External labour migration in Tajikistan: root causes, consequences and regulation, International Organisation for Migration.

[14] IOM (2009), Abandoned wives of Tajik labour migrants, International Organisation for Migration.

[13] IOM (2010), Tajik labout migration during the global economic crisis: causes and consequences, International Organisation for Migration.

[40] Jones Luong, P. (2004), Rethinking the Resource Curse: Ownership Structure and Institutional Capacity.

[31] Lederman, D. (2012), Does what you export matter?, IBRD / World Bank.

[11] Malyuchenko, I. (2015), Labour migration from Central Asia to Russia: Economic and social impact of the societies of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, Central Asia Security Policy Briefs.

[10] Marat, E. (2009), Labor Migration in Central Asia: Implications of the Global Economic Crisis.

[7] Observatory for Economic Complexity (2017), http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en.

[68] OECD (2000), OECD Small and Medium Enterprise Outlook, OECD Publishing.

[33] OECD (2006), OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Russian Federation 2006, OECD Publishing.

[20] OECD (2008), To benefit from plenty: lessons from Chile and Norway, OECD Development Centre.

[74] OECD (2009), Top Barriers and Drivers to SME Internationalisation, OECD Publishing.

[30] OECD (2011), The Economic Significance of Natural Resources: key points for reformers in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and CEntral Asia, OECD Publishing.

[22] OECD (2012), Kazakhstan - Investment Policy Review, OECD publishing.

[72] OECD (2013), Fostering SMes' participation in Global Markets, OECD Publishing.

[45] OECD (2014), Review of the Central Administration of Kazakhstan, OECD Publishing.

[65] OECD (2014), Regulatory Policy in Kazakhstan: Towards Improved Implementation, OECD Publishing.

[66] OECD (2015), SME Policy Index - Eastern Europe and South Caucasus, OECD Publishing.

[67] OECD (2015), Enhancing Access to Finance for SME Development in Tajikistan, OECD Publishing.

[19] OECD (2016), Sixth meeting of the policy dialogue on natural resource-based development.

[23] OECD (2016), Multi-dimensional Review of Kazakhstan: Volume 1. Initial Assessment, OECD publishing.

[32] OECD (2016), Anti-corruption reforms in Eastern Europea and Central Asia - Progress and Challenges 2013-2015, OECD Publishing.

[49] OECD (2016), Competition Law and Policy in Kazakhstan, OECD Publishing.

[69] OECD (2016), Entrepreneurship at a glance 2016, OECD Publishing.

[73] OECD (2016), Enhancing Access to Finance for MSMEs in Mongolia, http://www.oecd.org/globalrelations/eurasia-week-roundtable.htm#prs_2016.

[76] OECD (2016), Monitoring competitiveness reform in Kyrgyzstan.

[24] OECD (2017), OECD Investment Policy Review: Kazakhstan 2017, OECD publishing.

[64] OECD (2017), OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, http://www.oecd.org/trade/facilitation/indicators.htm.

[70] OECD (2017), Small, Medium, Strong. Trends in SME Performance and Business Conditions, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/book/9789264275683-en.

[71] OECD (2017), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2016: an OECD scoreboard, OECD Publishing.

[9] Ohlin, B. (1933), Interregional and international trade, Harvard University Press.

[53] Pomfret, R. (2014), Global Value-Chain and connectivity in developing Asia - with application to the central and west asian region, ADB Publishing.

[21] Ramey, G. (1995), “Cross-country evidence on the link between volatility and growth”, American Economic Review, pp. 1138-1151.

[17] Reuters (2017), Kazakh wealth fund says over 120 firms sold in privatization drive, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-kazakhstan-swf-privatisation-idUSKBN1772OK.

[44] RHCS (2017), , http://www.regionalhub.org/.

[28] Rodriguez-Clare (2005), Coordination Failures, Clusters and Microeconomic interventions, Inter-American Development Bank.

[27] University, C. (ed.) (1996), Coordination failures and government policy: A model with applications to East Asia and Eastern Europe, Journal of International Economics.

[39] Ross, M. (1999), “The Political Economy of the Resource Curse”, World Politics, pp. 297-322.

[8] Ryazantsev, S. (2016), Russia Global Affairs, http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/valday/Labour-Migration-from-Central-Asia-to-Russia-in-the-Context-of-the-Economic-Crisis-18334.

[3] Sachs, J. (1995), Economic convergence and economic policy.

[52] Sachs, J. (1995), “Natural Resource abundance and economic growth”, National Bureau of Economic Working Paper 5398.

[18] Samruk Kazyna (2016), Annual Report.

[37] Shafer, D. (1994), Winners and Losers: How Sectors Shape the Development Prospects of States, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

[35] Tornell, A. (1999), “The Voracity Effect”, American Economic Review, pp. 22-46.

[47] Transparency International (2016), Corruption Perception Index, http://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016.

[5] UN (2017), Human Development Data, http://hdr.undp.org/en/data.

[16] UNCTAD (2017), , http://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/.

[55] UNESCAP (2017), UNESCAP.ORG, http://www.unescap.org/our-work/transport/asian-highway/about.

[62] Vinokurov, E. (2017), “Eurasian Economic Union: Current state and preliminary results”, Russian Journal of Economics, pp. 54 - 70.

[63] Warwick, K. (2013), “Beyond Industrial Policy: Emerging Issues and New Trends”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, p. No. 2.

[59] World Bank (2016), Doing Business 2017 - Equal opportunity for all, World Bank.

[1] World Bank (2017), World Development Indicators, http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators.

[42] World Bank (2017), Enterprise Surveys, The World Bank, http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/.

[41] World Economic Forum (2017), The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017.

Notes

← 1. Purchasing power parities (PPPs) are the rates of currency conversion that equalise the purchasing power of different currencies by eliminating the differences in price levels between countries” (OECD, 2017). Real exchange rates exhibit both short- and long-run deviations from PPP values, largely illustrated in the Balassa–Samuelson theorem.

← 2. However, Tajikistan has to import alumina and other materials, so the net earnings from export of this commodity are significantly lower than those from the other raw commodities (and it is not included in Figure 1.4). Besides, Tajikistan’s aluminium exports can be considered de facto water-based exports as hydroelectricity is the main input from imported aluminia to Tajikistan’s aluminium exports.

← 3. The relative weight of remittances went sharply down in Tajikistan in 2015, owing to the recession in Russia and, in particular, the contraction in its construction sector: during 2010-14, remittance flows averaged 46% in Tajikistan.

← 4. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are the 3rd and 4th highest receivers of remittances in the world as a share of GDP.

← 5. That said, it is important to note that even if they do not become entrepreneurs, migrants may return with new technologies, goods and ways of doing business (Kireyev, 2006[331])

← 6. It should be noted that migration has likewise brought significant economic benefits to receiving countries, though these are not the focus of the present study. A great deal of economic activity in receiving countries now depends on foreign labour. This is particularly true of Russia, where it helps offset very low fertility, an ageing population and the consequent reduction in local labour forces.

← 7. The Herfindahl-Hirschmann Index (Product HHI), calculated by UNCTAD, ranges from 0 (more diversified) to 1 (more concentrated).

← 8. It is worth noting that there are some data issues in this context. For example (as in Figure 1.8), most of the gold sold by Kyrgyzstan went to intermediaries in Switzerland, without a clear indication of the final destination. The same was the case for the cotton sold in international exchanges by producing countries such as Tajikistan.

← 9. An important issue, beyond the scope of this paper, is how to adjust those guaranteed transfers in the face of macro-economic disturbances as a result of low commodity prices. The Kazakh authorities have wrestled with this recently and have, indeed, revised the regime governing the fund in an effort to put the country onto a more sustainable fiscal path (IMF, 2017[356]).

← 10. See the classic statement of the resource curse hypothesis by Sachs and Warner (Sachs, 2001[332]); many recent studies have also focused on the resource curse (Frankel, 2010[333]; van der Ploeg, 2011[334]; Venables, 2016[335]); on the “paradox of plenty”, see Karl (Karl, 1997[336]). Numerous hypotheses have been advanced to explain this phenomenon, with most falling into one of two categories: those that focus on the impact of resource wealth on the competitiveness of other tradables and those concerned with the effect of resource wealth on the quality of institutions, political processes and governance. Other analyses focus on the consequences of commodity-price volatility, particularly for fiscal revenues, and on the interaction of commodity-price volatility with financial market imperfections, which can lead to inefficient specialisation. For an overview of explanations of the resource curse, with particular emphasis on the issue of weak financial markets, see Hausman and Rigobon (Hausmann, 2003[337]).

← 11. The Kazakhstan Sovereign Wealth Fund described on page 19 was instrumental in forestalling any serious “Dutch disease” for the country's economy after the fall in commodity prices.

← 12. Co-ordination failures stem from discrepancies between production and investment decisions in the upstream and downstream part of an industry. Suppliers and customers of intermediary goods may not produce and invest in higher tech goods, leading to a lower-tech equilibrium. Government interventions can co-ordinate, subsidize and encourage upstream and downstream companies to invest in value added technology, skills and capabilities, thus reaching a higher-tech equilibrium.

← 13. If a government can easily control resource rents, then it does not need public approval (e.g. through a parliament) for public finance decisions. This happened in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in the 1990s: the governments could control the cotton gins, and hence pay farmers less than the global price and keep the difference as state revenue. It was harder for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia because they had to negotiate agreements with foreign companies with good know-how.

← 14. This proposition has not undergone much empirical analysis, for the simple reason that most of the literature focuses on minerals sectors in the period from the 1960s through the 2000s – a period during which the vast majority of mineral-rich countries opted for state ownership and control of mineral reserves. In other words, there is too little variation in the variable of primary interest to allow a deeper analysis.

← 15. The scoring system ranges goes as follows: 1 - No competition legislation and institution; 2 - Competition policy legislation and institutions set up; some reduction of entry restrictions or enforcement action on dominant firms; 3 - Some enforcement actions to reduce abuse of market power and to promote a competitive environment, including break-ups of dominant conglomerates; substantial reduction of entry restrictions; 4 - Significant enforcement actions to reduce abuse of market power and to promote a competitive environment; 4+ - Standards and performance typical of advanced industrial economies: effective enforcement of competition policy; unrestricted entry to most markets

← 16. The ADB’s definition of Central Asia includes Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia and excludes Mongolia.

← 17.