Chapter 6. Improving the internal control and risk management framework in Nuevo León

This chapter assesses Nuevo León’s internal control and risk management framework against international models and the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity. It provides an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the internal control and risk management framework in Nuevo León and presents proposals for action indicating how it could be reinforced to align with the Recommendation and good OECD country practices. The proposals include implementing a strategic risk management system, giving operational management ownership over the management of risk, establishing coherent internal control mechanisms and strengthening the effectiveness of the internal audit function.

6.1. Introduction

An effective internal control and risk management framework is essential in public sector administration to safeguard integrity, enable effective accountability and prevent corruption. Principle 10 of the OECD’s Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity encourages establishing an internal control and risk management framework that includes:

-

a control environment with clear objectives that demonstrate managers’ commitment to public integrity and public service values, and that provides a reasonable level of assurance of an organisation’s efficiency, performance and compliance with laws and practices;

-

a strategic approach to risk management that includes assessing risks to public integrity, addressing control weaknesses, as well as building an efficient monitoring and quality assurance mechanism for the risk management system;

-

control mechanisms that are coherent and include clear procedures for responding to credible suspicions of violations of laws and regulations and facilitating reporting to the competent authorities without fear of reprisal (OECD, 2017[1]).

In addition to an effective control environment, strategic risk management and coherent control mechanisms, a public administration system should have an effective and separate internal audit function.

6.2. A control environment with clear objectives

6.2.1. Nuevo León should ensure that its control environment and organisational structure support its internal control and risk management framework.

Before determining risks and internal controls, it is vital that a government entity establish clear objectives for the entity as a whole, for individual programmes and for specific activities. If there is no clear objective, internal controls and risk management cannot be implemented effectively. In Nuevo León, the objectives for the overall internal control and risk management framework should be linked to implementation of the State Anti-corruption System (Sistema Estatal Anticorrupción para el Estado de Nuevo León, or SEANL), which came into force on 7 July 2017, and will require a more efficient internal control structure. Under the system’s enacting law, the executive and judiciary branch and government entities had six months to issue regulations and make the legal modifications necessary for its implementation. Nuevo León should ensure that clear objectives for the internal control and risk management framework are established and communicated to staff.

Once Nuevo León has ensured that clear objectives are established and that these have been effectively communicated to staff, it should consider the elements of its control environment. The control environment is the foundation for all other components of internal control. According to the Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector established by the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI), elements of the control environment are:

-

the personal integrity and ethical values of management and staff, including a supportive attitude toward internal control throughout the organisation;

-

commitment to competence;

-

the “tone at the top” (i.e. management’s philosophy and operating style);

-

organisational structure;

-

human resource policies and practices (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 17[2]).

Cultivating a culture of personal integrity and an ethical “tone at the top” should be an ongoing part of an organisation’s operations. This requires the commitment of management and staff and positive reinforcement. Nuevo León has taken some action to promote a culture of integrity through training courses and the introduction of a code of ethics (see Chapter 3). Having an appropriate organisational structure, framework and policies will also help ensure that an entity functions efficiently, with integrity and in compliance with relevant laws.

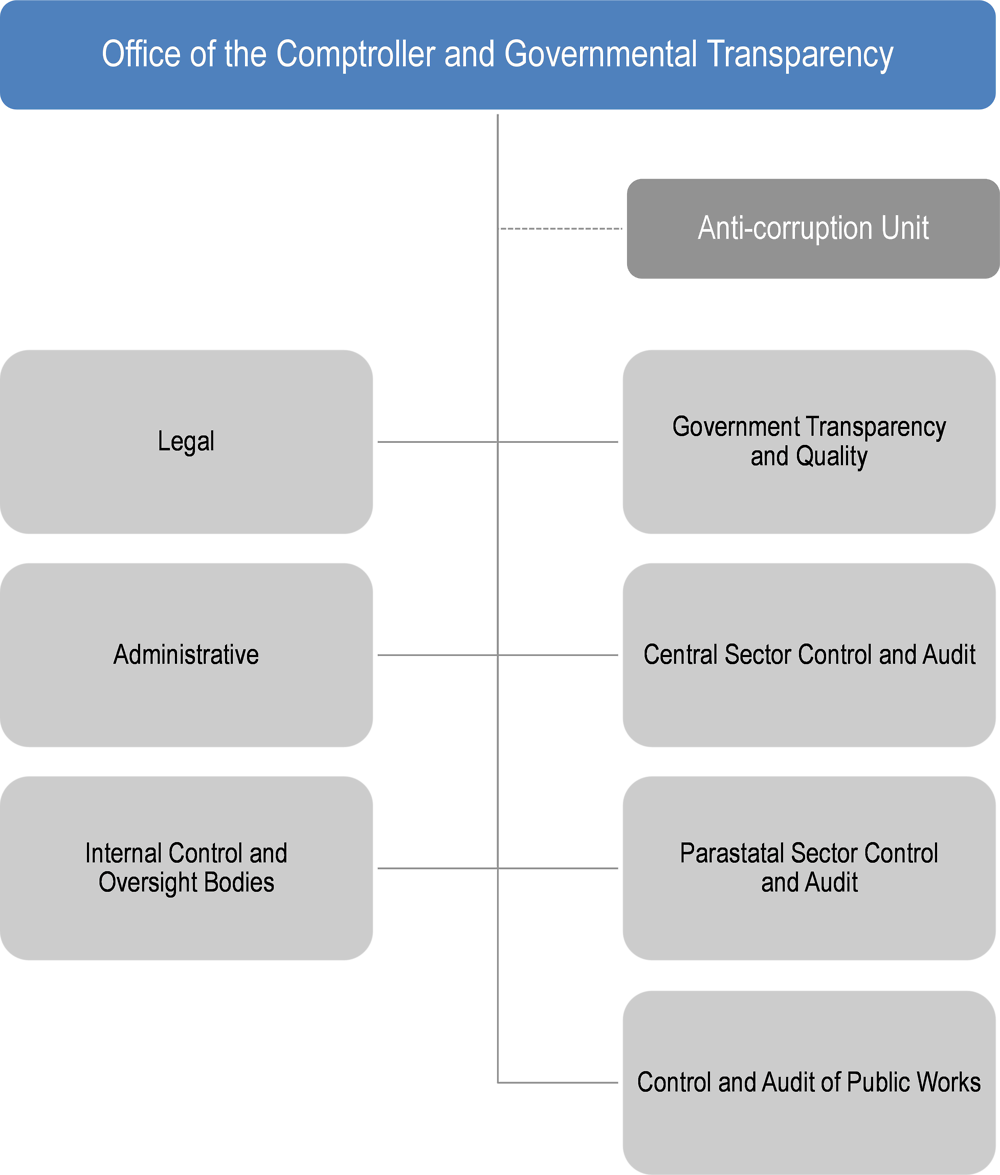

In Nuevo León, the Office of the Comptroller and Government Transparency (Contraloría y Transparencia Gubernamental, hereinafter Office of the Comptroller) is the main state-level entity responsible for strengthening the co-ordination with the internal control and oversight bodies of the agencies and entities of the state’s public administration. In particular, the Office of the Comptroller’s responsibilities include the authority to: co-ordinate the control systems of the state’s public administration; order reviews and audits; co-ordinate responses to complaints and nonconformities; impose penalties; ensure public services are provided in accordance with the principles of legality, efficiency, honesty, transparency and impartiality; and cultivate a culture of transparency and integrity.

The mission of the Office of the Comptroller is to “promote the best practices of government and internal control, promoting legality, honesty, responsibility, efficiency, transparency and quality in services and the best performance of public servants”. The Office of the Comptroller has seven directorates and an Anti-corruption Unit (see Figure 6.1).

An Agreement for the Functional Co-ordination of the Internal Control Bodies was issued in 2007 by the Executive Branch of the State of Nuevo León. This agreement provides that the Office of the Comptroller functionally co-ordinate the internal control and monitoring system between the entities and the Comptroller and carry out public inspection and evaluation; and that entities that have established their own internal control unit should co-ordinate and plan their activities with the Office of the Comptroller.

The co-ordination is carried out through the Annual Audit and Internal Control Programme (Programa Anual de Auditoría y Control Interno, or PAACI), prepared in accordance with the 2007 Agreement and the Guidelines for the Functional Co-ordination of the Internal Control Bodies. The guidelines, which were issued by the Comptroller-General and published in the Official Journal of the State (Periódico Oficial del Estado) in October 2007, outlined the functions of the Comptroller-General (see Table 6.1).

Within the Office of the Comptroller, the Office of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies (Dirección de Órganos de Control Interno y Vigilancia) co-ordinates with the Internal Control Units in the different entities and, for entities with no formal internal control unit, through internal control contacts. The Office of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies has the authority to:

-

strengthen co-ordination with the internal control and oversight bodies of the agencies and entities of the State’s Public Administration;

-

verify that the public commissioners comply with their obligations in parastatal entities;

-

review, validate and submit to the Comptroller-General for consideration the work programmes established by the internal control bodies and the results of the work programmes.

Internal controllers and internal control contacts are required to: report to the Office of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies bi-monthly on the progress of the PAACI; and follow up on the implementation of recommendations (both for internal and external audits).

The Internal Control Normative Provisions sent by the Office of the Comptroller to the State’s Public Administration units and entities came into effect under a letter dated 3 July 2013. These provisions are based on the Internal Control Framework issued at the federal level. According to the Normative Provisions, the single Internal Control System comprises the set of processes and mechanisms that are applied in an entity in the stages of planning, implementing, and monitoring their management processes, to give certainty to the decision-making process and to achieve their objectives in an environment of integrity, quality, continuous improvement, efficiency and compliance with the law. The purpose of the Single Internal Control System in achieving the goals of the units or entities is outlined in Table 6.2.

The intended purpose of Nuevo León’s internal control system include vital elements such as managing risk (Purpose 2), ensuring integrity and transparency (Purpose 7) and strengthening processes to achieve objectives and prevent corruption (Purpose 8). It is advisable that the internal audit function be kept separate from this outline of internal control system purposes. Nuevo León should ensure that its control environment and organisational structure provides a good basis for its internal control and risk management framework.

6.2.2. Nuevo León could arrange for all staff to receive training on the internal control and risk management framework, to ensure it is implemented consistently .

The Annual Audit and Internal Control Programme indicates that the Office of the Comptroller will promote and verify the training of public servants. The Comptroller’s Office is required to verify that each entity has a training programme set up and in operation and that each comply with the Programme of Legality Culture and Combatting Corruption, which is co-ordinated by the Anti-corruption Unit (see Chapter 3).

Internal auditors (the third line of defence) play a key role in defining the right culture of integrity and accountability within the organisation. They act as key “Agents of Change” by assessing the control environment as part of their assurance mandate, and motivate management to address any flaws and inefficiencies in the control environment. Nuevo León has trained a further 500 public servants to be “Agents of Change” and to pass on to their colleagues the information they have learned.

Nuevo León could benefit from making sure all staff receive information and training on the internal control and risk management framework, so that it can be consistently implemented. The way senior officials apply the framework and react to compliance and deviation is crucial for enhancing the credibility of the control environment. Enforcement and disciplinary procedures should be clear, transparent and applied equally to everyone. They should also be communicated to all public officials to guarantee a shared understanding of the rules. Communicating the examples of officials who demonstrate exemplary behaviour can help promote integrity.

6.2.3. Nuevo León could apply the principles of the “three lines of defence” model to give greater responsibility for internal control and risk management to operational management.

With its established Guidelines (2007) and Normative Provisions (2013), Nuevo León has in principle provided a strong basis for its internal control and risk management framework. Encouraging management and all staff members to participate can help develop better systems and procedures that improve the organisation’s integrity and its resistance to corruption. While senior managers should be primarily responsible for managing risk, implementing internal controls and demonstrating the entity’s commitment to ethical values, all officials in a public organisation, from the most senior to the most junior, should play a role in identifying risks and deficiencies and ensuring that internal controls address and mitigate these risks. One of the core missions of public officials responsible for internal control is to help ensure that the organisation’s ethical values, and the processes and procedures underpinning those values, are communicated, maintained and enforced throughout the organisation.

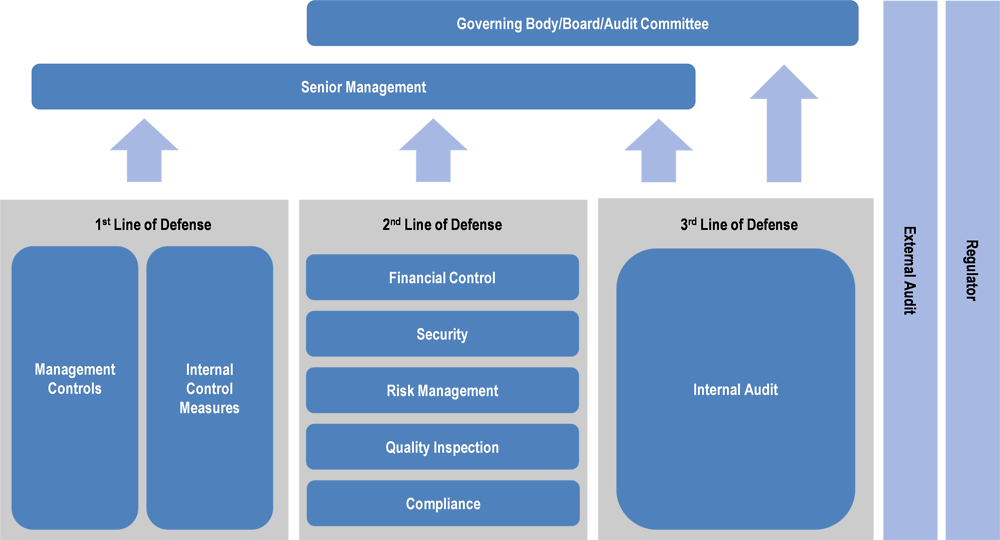

The leading fraud and corruption risk management models among OECD member and partner countries stress that the primary responsibility for preventing and detecting corruption rests with the staff and management of public entities. Such corruption risk management models often share similarities with the Institute of Internal Auditors’ “three lines of defence” model (see Figure 6.2).

Under the Institute of Internal Auditors’ model, the first line of defence comprises operational management and personnel. Those on the front line naturally serve as the first line of defence, because they are responsible for maintaining effective internal controls and for executing risk management and control procedures on a day-to-day basis. Operational management identifies, assesses, controls and mitigates risks, guiding the development and implementation of internal policies and procedures and ensuring that activities are consistent with goals and objectives (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2013[3]).

The second line of defence includes the next level of management: those with responsibility for oversight of delivery. This line is responsible for establishing a risk management framework, monitoring, identifying emerging risks, and regular reporting to senior executives. The third line of defence is the internal audit function. Its main role is to provide senior management with independent, objective assurance over the first and second lines of defence arrangements (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2013[3]).

In Nuevo León, greater responsibility for internal control and risk management could be given to operational management. The evolution of the French internal control system, which focuses on managerial responsibility, provides useful insight (see Box 6.1).

In 2006, the Organic Law Governing Budget Laws of 1 August 2001 (La loi organique relative aux lois de finances) took effect, providing an opportunity to reconsider the management of public expenditure. It was accompanied by a shift in the role of the main actors involved in the control and management of France’s public finances.

Key features of the reform introduced in France’s public administration include: objective-based public policy management; a results-oriented budget; a new system of responsibility; strengthened accountability; and a new accounting system.

The Decree of 28 June 2011 on internal audits is the culmination of a drive to control the risks in the management of public policies. This reform made it possible to extend the scope of internal control to all functions in ministerial departments and to establish an effective internal audit policy.

The French system focuses on managerial responsibility. The programme manager is the key link between the political responsibility (assumed by the minister) and managerial responsibility (assumed by the programme manager). Under the minister’s authority, the programme manager drafts the strategic objectives of the relevant programme and undertakes the operational implementation of the programme to fulfil its objectives. The minister and the programme manager become accountable for the objectives and indicators specified in Annual Performance Plans (APP). These national objectives are adapted, if necessary, for each government entity. The programme manager delegates the management of the programme by establishing operational budgets under the authority of appointed managers.

Source: (OECD Working Party of Senior Budget Officials, 2015[4]; European Commission, 2014[5]).

6.3. A strategic approach to risk management

6.3.1. Nuevo León could introduce a strategic risk management framework to strengthen the internal control framework and improve management of the risk of fraud and corruption.

An effective internal control and risk management framework includes policies, organisational structures, procedures and processes that allow an organisation to identify and respond to risks appropriately.

Nuevo León declared that its internal control system should offer “mechanisms to monitor the progress in the achievement of objectives and targets and to identify and manage risks that may block achievement of these objectives”. However, public officials indicated in interviews that no specific methodology for risk management has been formally established in the public sector for the state and that risk management is generally not carried out. Some initial groundwork has been conducted, and some training provided to internal control staff on risk management included theoretical concepts for implementing a risk matrix and risk mapping.

Good governance practices in OECD countries indicate that risk management must be considered an integral part of the institutional management framework rather than managed in isolation. Risk management should permeate the organisation’s culture and activities so that it becomes the business of everyone within the organisation. Informed employees who can recognise and deal with corruption are more likely to identify situations that can undermine institutional objectives.

In the public sector, the concept of operational risk management should include the systems, processes and culture that help identify, assess and treat risk to help public sector entities achieve their performance objectives (OECD, 2013[6]).

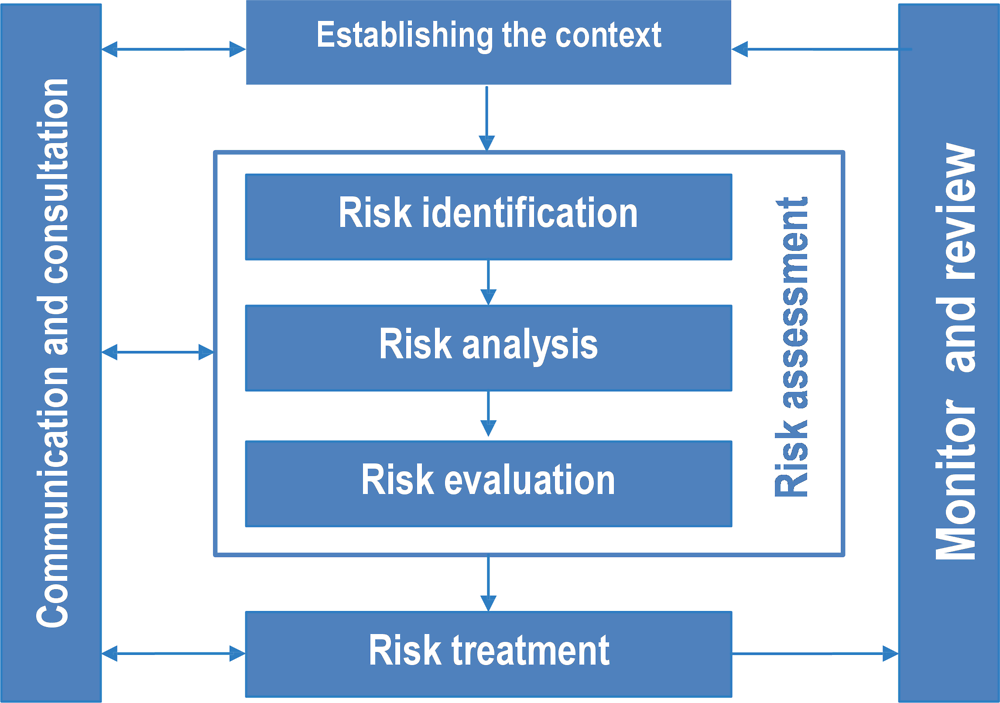

Operational risk management begins with establishing the context and setting an organisation’s objectives. It goes on to single out events that might have an impact on their achievement. Events that may have a negative impact are risks. Risk assessment is a three-step process that starts by identifying risk and is followed by risk analysis, which involves developing an understanding of each risk, its consequences, the likelihood of those consequences occurring, and the severity of the risk. The third step is risk evaluation, to determine the tolerability of each risk and whether the risk should be accepted or treated. Risk treatment means adjusting existing internal controls or developing new controls to bring the severity of a risk to a tolerable level (ISO, 2009[7]). For a depiction of the risk management cycle, see Figure 6.3.

The process of establishing context and assessing and treating risk is linear, while communication and consultation, monitoring and reviewing are continuous. Communication and consultation with internal and external stakeholders is, where practicable, a key step towards securing their input in the process and giving them ownership of the outputs of risk management. It is also important to understand stakeholders’ concerns about risk and risk management, so that their involvement can be planned and their views taken into account in determining risk criteria. Monitoring and reviewing helps single out new risks and the reassessment of existing ones when there are changes in the organisation’s objectives or in its internal and external environment. This involves scanning for possible new risks and learning lessons about risks and controls by analysing successes and failures (OECD, 2013[6]; ISO, 2009[7]).

Interviews with public officials suggested that the administration faces integrity risks, such as fraud, favouritism, bribery and abuse of power. Nuevo León also indicated that there was no executive officer specifically responsible for risk management, and that risk assessments related to corruption or fraud are not conducted. This can be confirmed by the fact that this feature was not considered in the State Development Plan 2016-2021 or in the Strategic Plan of Nuevo León 2015-2030, setting up an efficient and transparent government. The incorporation of risk management framework could be considered when Nuevo León revises its strategic plans, particularly the sections that relate to combating fraud and corruption.

Nuevo León indicated that its main challenges in integrating an internal control and risk management framework into day-to-day management were:

-

lack of practical guidelines for implementing an internal control system;

-

staff considering internal controls to be a mere formality and bureaucratic burden, rather than important tools for promoting integrity and improving performance;

-

insufficient communication on the importance of internal control processes for the achievement of organisational objectives;

-

staff considering internal controls and risk management to be objectives in themselves;

-

lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities for internal controls.

Having an effective risk management framework in place is essential to managing risks of fraud and corruption. Nuevo León could implement a strategic risk management framework to strengthen its internal control framework and improve the management of fraud and corruption risks. The United States’ Government Accountability Office (GAO) has established a risk management framework for managing fraud risks in federal programmes. This example, which includes practical processes and activities, is outlined in Box 6.2.

The United States’ Government Accountability Office (GAO) has a framework for managing fraud risks in federal programmes. This includes control activities, as well as structures and environmental factors that help managers mitigate fraud risks. The framework consists of four components for effectively managing fraud risks.

-

1. Commit to combating fraud by creating an organisational culture and structure conducive to fraud risk management.

-

Demonstrate senior-level commitment to combat fraud and involve all levels of the agency in setting an anti-fraud tone.

-

Ensure there are defined responsibilities for risk management.

-

-

2. Assess: Conduct regular fraud risk assessments to determine a fraud risk profile.

-

Tailor the fraud risk assessment to the programme, and involve relevant stakeholders.

-

Assess the likelihood and impact of fraud risks and determine risk tolerance.

-

Examine the suitability of existing controls, prioritise residual risks and document a fraud risk profile.

-

-

3. Design and implement a strategy with specific control activities to mitigate assessed fraud risks and collaborate to help ensure its implementation.

-

Develop, document and communicate an anti-fraud strategy, focusing on preventive control activities.

-

Consider the benefits and costs of controls to prevent and detect potential fraud, and develop a fraud response plan.

-

Establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and create incentives to assist in effective implementation of the anti-fraud strategy.

-

-

4. Evaluate and adapt: Evaluate outcomes using a risk-based approach and adapt activities to improve fraud risk management.

-

Conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluation of fraud risk management activities, with a focus on outcome measurement.

-

Collect and analyse data from reporting mechanisms and instances of detected fraud, for real-time monitoring of fraud trends.

-

Use the results of monitoring, evaluations and investigations to improve fraud prevention, detection and response.

-

As outlined under each of these components, ongoing practices and activities can help an organisation maintain its monitoring and feedback mechanisms and ensure that the framework remains dynamic and that staff remain engaged in the processes.

Source: (GAO, 2015[8]).

6.3.2. Nuevo León could operationalise the risk management framework by assigning clear responsibility for managing risk to senior managers, providing training for staff and updating risk management systems and tools.

After developing a risk management framework, it must be put into operation. Appropriate and accurate risk management information needs to be collected. Senior management will need to be assigned clear responsibility for the ongoing management and monitoring of risk, and all staff need to be aware of the risk management framework and how to incorporate risk management into their daily work and decision-making.

Appropriate and accurate risk information is essential for operationalising a risk management framework. Without it, effectively assessing, monitoring and mitigating risk would be difficult. Information to support risk management can derive from a number of internal and external sources, depending on the programme or area of work. A consistent approach to sourcing, recording, and storing risk information will improve the reliability and accuracy of the required information.

For a risk management framework to function effectively, responsibility for specific risks needs to be clearly assigned to the appropriate secretaries or directors. These secretaries or directors need to take ownership of the risks that could affect their institutional objectives, use risk information to inform decision-making and actively monitor and manage their assigned risks. They should also be held accountable to the executive through regular reporting on risk management, including on lessons learned, successes and areas that could be improved (Department of Finance, 2016[9]).

Staff should be made aware of the risk management framework and key requirements through training and awareness-raising activities. Further, job descriptions could include risk management requirements. Communication and consultation with staff is also a key step in securing input in the risk management process and giving them ownership of the output of risk management. Informed employees who can recognise and deal with corruption risks are more likely to identify situations that can undermine the achievement of institutional objectives.

Nuevo León could operationalise the risk management framework by assigning clear responsibility for the management of risk to secretaries or directors, providing training for staff and updating risk management systems and tools. OECD member country, Australia, has developed guidance on building risk management capability in entities, which provides useful insights (see Box 6.3).

The Australian federal Department of Finance has developed guidance for government officials on how to build risk management capability in their entities. It suggests that entities consider each of the areas outlined below to determine where improvements may be made to their risk capability.

People capability – A consistent and effective approach to risk management is the result of well-skilled, well-trained and adequately resourced staff. All staff have a role to play in the management of risk. It is important that staff at all levels have clearly articulated and well-communicated roles and responsibilities, access to relevant and up-to-date risk information, and the opportunity to build competency through formal and informal learning and development programmes. Building the risk capability of staff is an ongoing process. With the right information and learning and development, a government entity can build a risk-aware culture among its staff and improve the understanding and management of risk. Considerations include:

-

Are risk roles and responsibilities explicitly detailed in job descriptions?

-

Have you determined the current risk management competency levels and completed a needs analysis to identify learning needs?

-

Do induction programmes incorporate an introduction to risk management for all levels of staff?

-

Is there a learning and development programme that incorporates ongoing risk management training tailored to different roles and levels of the entity?

Risk systems and tools – Varying in complexity, risk systems and tools are designed to provide storage and accessibility of risk information that will complement the risk management process. The complexity of risk systems and tools often range from simple spreadsheets to complex risk management software and are most effective when they are adaptable to the needs of the entity. The availability of data for monitoring, risk registers and reporting will help build risk capability, provided the systems and tools are well maintained, information is rich and up-to-date and training and support is provided. Considerations include:

-

Are your current set of risk management tools and systems effective in storing the required data to make informed business decisions?

-

How effective are your risk systems in providing timely and accurate information for communication to stakeholders?

Managing risk information – Successfully assessing, monitoring and treating risks across a government entity depends on the quality, accuracy and availability of risk information and the supporting documentation. A consistent approach to the sourcing, recording, and storage of information will improve the reliability and availability of required information to different audiences. Considerations include:

-

Have you identified the data sources that will provide you with the necessary information for a complete view of risk across the entity?

-

What is the frequency of collating risk information for delivery to different audiences across the entity?

-

Do you have readily available risk information accessible to all staff?

-

How would you rate the integrity and accuracy of the available data?

Risk management processes – The effective documentation and communication of the risk management processes that support the entity’s approach to managing risk will provide a consistent approach to risk management and allow for clear, concise and frequent presentation of risk information to support decision making. Considerations include:

-

When was the last time your risk processes were reviewed?

-

Are your risk management processes well documented and available to all staff?

-

Do risk management processes align with your risk management framework?

-

Is there training in the use of your risk processes available, tailored to different audiences?

Source: (Department of Finance, 2016[9]).

6.4. Coherent control mechanisms

6.4.1. Nuevo León could strengthen and integrate its internal control activities to ensure that reasonable assurance is provided.

One fundamental way risks are mitigated and treated is through the implementation of internal control mechanisms. Internal controls are implemented by an entity’s management and personnel and continuously adapted and refined to address changes to the entity’s environment and risks. Internal control activities are designed to address risks that could affect the achievement of the entity’s objectives and to provide reasonable assurance that the entity’s operations are ethical, economical, efficient and effective; that accountability and transparency obligations are met; that activities and actions comply with applicable laws and regulations; and that resources are safeguarded against loss, misuse, corruption and damage (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 6[2]).

Control mechanisms constitute checks and balances that are the responsibility of secretaries or directors and are carried out by staff on a daily basis. Internal controls include a wide range of processes designed to ensure that employees and managers exercise their duties within the parameters established by the entity. The overall goal of internal control should be that the rules and values of the organisation are implemented in accordance with senior management’s vision and with a view to meeting the organisation’s strategic objectives.

According to INTOSAI’s Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector, internal control activities should occur throughout an entity, at all levels and in all functions. They include a range of detective and preventive control activities, such as:

-

authorisation and approval procedures;

-

segregation of duties (authorising, processing, recording, reviewing);

-

controls over access to resources and records;

-

verification;

-

reconciliation;

-

reviews of operating performance;

-

reviews of operations, processes and activities;

-

supervision (assigning, reviewing and approving) (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 28[2]).

For example, authorising and executing procurement transactions should only be done by persons acting within the scope of their authority. Authorisation is the principal means of ensuring that only valid transactions and events are initiated as intended by management. Authorisation procedures, which should be documented and clearly communicated to managers and employees, should include the specific conditions and terms under which authorisations are to be made. Conforming to the terms of an authorisation means that employees act in accordance with directives and within the limitations established by management or legislation (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 29[2]). Nuevo León should ensure these types of financial controls are in place and that guidance and standard operating procedures for staff are up to date.

Internal controls should not attempt to provide absolute assurance, as this could potentially constrict activities to a point of severe inefficiency. “Reasonable assurance” is a term often used in audit and internal control environments. It means a satisfactory level of confidence given due consideration of costs, benefits and risks. Determining how much assurance is reasonable requires judgment. In exercising this judgment, managers should identify the risks inherent in their operations and the levels of risk they are willing to tolerate under various circumstances. Reasonable assurance accepts that there is some uncertainty and that full confidence is limited by the following realities: human judgment in decision making can be faulty; breakdowns can occur because of simple mistakes; controls can be circumvented by the collusion of two or more people; and management can choose to override the internal control system (INTOSAI, 2010, pp. 8-9[2]). Nuevo León could strengthen and integrate its internal control activities to ensure that reasonable assurance is provided.

6.4.2. Nuevo León could ensure that each internal control serves a purpose and that the overall system is monitored, ethical and efficient.

In setting internal controls, management should consider the costs of each control, that is, monetary costs, time costs and opportunity costs. Management needs to weigh the potential benefit of each control against the potential cost and ensure that its benefits will outweigh the costs. Should this not be the case, management should consider alternate methods of control that will achieve the desired outcome. Management should monitor internal control systems and adapt them where necessary to ensure that internal controls are pitched at the right level to be effective and provide reasonable assurance. At the same time, they should not overburden systems and staff with controls to the point where quality, timeliness and responsiveness are affected. A system out of balance can lead to staff circumventing burdensome control processes, which defeats the purpose and can expose an entity to additional risks.

Internal controls also provide reasonable assurance to the public and key stakeholders that government transactions are being undertaken in a transparent, ethical and fair manner. Procurement is a government activity particularly vulnerable to fraud and corruption. The government needs to put levels of control in place to ensure that public funds are being spent appropriately and receiving value for money, that regulations and laws are complied with and that suppliers and tenderers are treated fairly and without favouritism. This is a matter of reputation and credibility. A balance needs to be struck in this respect. On the one hand, internal controls increase confidence in government and promote fair and consistent treatment of key stakeholders. On the other hand, internal controls that are out of balance or have too many layers of bureaucracy can lead to lethargic administrative processes that reduce the credibility of government.

For example, in Nuevo León, it appears that staff sometimes purchase items (such as ink for printers) with their personal funds, without prior authorisation, and then seek, and receive, reimbursement. Such practices appear to have developed as a result of an inefficient and cumbersome purchasing system.

Internal control should be a dynamic process that is refined and adapted as risks and environments change. Nuevo León should ensure that the internal control system is monitored and that there are clear means for adapting and refining procedures to respond to changes in objectives, risks and circumstances. Nuevo León could also ensure that each internal control serves a purpose, with its benefits outweighing its costs, and that the overall system is ethical and efficient.

6.4.3. Nuevo León could consider making better use of its internal control reporting function for identifying issues and risks and reporting on them to management.

Each entity’s Internal Control Unit (or equivalent) is responsible for reporting to the Office of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies within the Office of the Comptroller every two months on whether the entity has complied with relevant laws, norms and requirements, including those related to procurement. As of May 2018, 15 entities had Internal Control Units. For those entities without one, this responsibility is assigned to an “Internal Control Contact”, a person who has another full-time job, but is responsible for completing the reporting template every two months.

If an entity has not met requirements, it needs to provide an explanation why. This type of reporting can assist with the consistent application of laws, regulations and policies across the government. However, although the Office of Internal Control and Oversight Bodies indicated that it tries to follow up on these cases, it has limited resources for doing so and there is no process for capturing this information or reporting it to management.

Nuevo León could consider making better use of this established reporting mechanism. This information can be used to identify trends, issues and risks and assist management in risk management and decision making.

6.5. An effective and separate internal audit function

6.5.1. Nuevo León could consider investing in training, tools and methodologies for internal audit staff to improve the quality and efficiency of audits.

In Nuevo León, the Central Sector Control and Audit Office (Dirección de Control y Auditoría del Sector Central) and the Parastatal Sector Control and Audit Office (Dirección de Control y Auditoría del Sector Paraestatal) have, in their respective sectors, responsibility to: conduct and report on audits, reviews, monitoring actions, inspections; verify and monitor compliance with internal control processes; and verify that the operations of entities are consistent with planning, budgeting, monitoring, evaluation and accountability processes.

The Central Sector Control and Audit Office has 27 staff, including 24 who work on audits. They are responsible for auditing central government entities and the education sector and for conducting follow-up audits. Central government includes the entities that report directly to the governor, such as Infrastructure, Health and Finance and the General Treasury of the State.

The Parastatal Sector Control and Audit Office has 14 staff, including 5 audit directors and 7 audit staff members. They are responsible for auditing 65 parastatal entities (enterprises that are wholly or partially owned by the state), and they conduct approximately 30 audits, inspections and reviews each year. Interviews during the OECD fact-finding mission indicated that audit staff have received little to no professional audit training and have not been provided with basic auditing tools and methodologies. A modest investment in tools and training could increase the efficiency and quality of audits. Given the importance of internal audit in an integrity framework, Nuevo León could consider whether this office would benefit from increased resources and the professionalisation of its workforce and could consider investing in training, tools and methodologies for internal audit staff, to improve the quality and efficiency of audits.

6.5.2. Nuevo León could ensure that its central co-ordination of internal audit leverages available resources to enhance oversight and allow for a coherent response to integrity risks.

According to the OECD’s Government at a Glance 2017, a central internal audit function, particularly one with an emphasis on including integrity in its strategic objectives, can strengthen the coherence and harmonisation of the government’s response to integrity risks. Auditing multiple entities at a central level can leverage audit resources; enhance the government’s ability to identify systemic, cross-cutting issues; and put measures in place to respond from a whole-of-government perspective (OECD, 2017[10]).

Nuevo León could build on its centralised internal audit functions, undertaken by the Central Sector Control and Audit Office and the Parastatal Sector Control and Audit Office, to enhance oversight through the identification of trends and systemic issues and allow management to respond to emerging issues, including integrity risks, in a coherent, holistic way.

Fifteen OECD countries, including Mexico and Canada, report having a central internal audit function with responsibility for auditing more than one government ministry. The Comptroller-General in Canada offers one example of internal audit co-ordination that includes policy and liaison, developing the audit community and providing co-ordinated audit services (see Box 6.4).

The Internal Audit Sector of the Office of the Comptroller-General of Canada is responsible for the Policy on Internal Audit and the federal government internal audit community. Its mandate is to provide independent assurance on governance, risk management and control processes. In performing this role, the Sector supports the commitment of the Comptroller-General to strengthen public sector stewardship, accountability, risk management and internal control across government. The three main areas of responsibility of the Internal Audit Sector are as follows:

-

1. Policy and liaison – focuses on the timely provision of guidance and oversight to the audit community. This includes:

-

leading and championing the internal audit function;

-

monitoring and evaluating policy implementation and compliance;

-

providing oversight and challenge support to departmental internal audit groups;

-

Developing policy, professional advice, standards and technology enablers.

-

-

2. Internal audit community development – provides support to departmental audit committees and initiatives to support internal audit capacity development. This includes:

-

recruiting and supporting department audit committees;

-

reinforcing the human resources capacity of the internal audit community through capacity building and community development activities.

-

-

3. Audit operations – provides audit services to large and small departments and agencies. This includes:

-

developing government-wide risk profiles;

-

planning and co-ordinating horizontal assurance engagements across departments;

-

providing specific internal audit services; and

-

providing support to the Audit Committee for small departments and agencies.

-

Sources: (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2014[11]).

6.5.3. Nuevo León could build on its internal control training programme to provide further training on ethics and integrity for internal auditors.

A key element for maintaining an effective internal control environment is ensuring the merit, professionalism, stability and continuity of audit staff. Public entities should develop the right mechanisms to attract, develop and retain competent individuals with the right set of skills and the ethical commitment to work in control and audit. Training, certification and the improvement of auditing and investigative competencies reinforces the credibility of the auditor. Training modules should be a tool for practitioners to address the complexities they typically encounter. There is a large gap between professional certifications and the actual integration of internal control and audit functions into public entities’ daily management and operations.

The Office of the Comptroller and the General Treasury of the State have signed an agreement with the Institute of Public Accountants of Nuevo León and the School of Specialties for Professional Accountants. This allows for public servants to be trained in the School of Specialties for Professional Accountants. In addition to formal certifications, the School also offers diplomas and refresher courses.

The Office of the Comptroller has established a training programme in an effort to strengthen the capacity of staff in internal control units. The first training course, held in March 2016, was entitled “Internal Control Bodies in the State Public Administration” and was attended by 135 public servants involved in internal control activities. This half-day course included the following topics:

-

The Functional Co-ordination of Internal Control Bodies;

-

The Vigilance Function through the Public Commissioner;

-

The Annual Audit and Internal Control Programme;

-

The Integrated Internal Control Framework.

In April 2016, a half-day course, “Strengthening Transparency and Prevention of Corruption through Internal Control Bodies” was attended by 127 public servants and included the following topics:

-

Transparency in Internal Control Bodies;

-

Protection of Personal Data;

-

The Basic Legal Framework;

-

Open Government;

-

Anti-corruption Preventive Strategies; and

-

Anti-corruption Complaints.

In May 2016, a course on Internal Control and Risk Management was attended by 150 public servants. A course titled “Internal Control, Transparency and Prevention of Corruption through the Municipal Comptroller”, was held in July 2016 and attended by 99 public servants from 38 municipalities in the state. The objective of the course was to encourage institutional collaboration between the state comptroller and those of the municipalities of Nuevo León, through sharing knowledge and experience related to internal control, transparency, personal data protection and strategies for the prevention and reporting of corruption. Nuevo León could build on this training programme for internal controllers to provide further training on ethics and integrity for internal auditors.

6.5.4. Nuevo León could strengthen mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations.

Nuevo León’s Normative Provisions require that audit recommendations be followed up. In OECD interviews, Nuevo León auditors indicated that generally, implementation of recommendations was low and that recommendations were difficult to monitor and follow up. This was partly due to limited resources for follow-up and partly due to the lack of engagement by the audited areas. Internal auditors report the number of recommendations that have been implemented, based on available information, to the Office of the Comptroller on a regular basis. However, auditors have little to no capacity to follow up these recommendations or address the low implementation rate.

Nuevo León could strengthen mechanisms for monitoring implementation of audit recommendations. Audit offices from OECD member countries have a variety of mechanisms for following up audit recommendations and tracking implementation rates. Some offices, such as the Australian National Audit Office, conduct follow-up audits each year, and others use self-reporting to give an indication of the level of implementation. The sub-national audit office for the province of British Columbia in Canada offers one example of a self-reporting approach to the follow-up of audit recommendations (see Box 6.5).

In June 2014, British Columbia’s Office of the Auditor-General (OAG) published a report entitled Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation Of Recommendations from Recent Reports. According to the Auditor-General of British Columbia at the time, it was critical that the OAG follow up on the recommendations to ensure that citizens receive full value for money from the OAG’s work, since the recommendations identify areas where government entities can become more effective and efficient.

The OAG followed up by publishing a report including self-assessment forms completed by audited entities. These forms were published unedited and were not audited. The report contained 18 self-assessments, 2 of which reported that the entity had fully or substantially addressed all the recommendations in their reports.

The OAG also followed up on its recommendations by auditing four self-assessments to verify their accuracy. It found that in almost all cases, entities had accurately portrayed the progress they had made in implementing the recommendations. While recommendations were sometimes found to be partially rather than fully or substantially implemented, as self-reported, the discrepancy usually resulted from a difference in understanding of what fully or substantially implemented meant. In those cases, the OAG worked with the ministries and agencies to clarify expectations and reach agreement on the status of the implementation.

Source: (Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, 2014[12]).

To follow up sanctions, Nuevo León has established direct co-ordination between the Comptroller and the Superior Audit Office of the State of Nuevo León (Auditoría Superior del Estado de Nuevo León, or ASENL). This co-ordination could be further increased. Where the ASENL finds irregularities, it sends a report to the units and requests that they undertake corresponding administrative liability procedures. Once this process is completed, penalties imposed by the entities are reported back to the ASENL.

6.5.5. Nuevo León could strengthen the independence of its internal audit function by ensuring that it is separate from entity management functions—including the implementation of internal controls and risk management.

Internal auditors do not need the same level of independence as external auditors, but it is important that they maintain their independence from the management of the entities they audit. This allows auditors to present unbiased opinions on their assessments of internal control and objectively present recommendations for improvement.

Nuevo León’s internal auditors are generally separate from the management of entities they audit, and have independence to choose what they audit, while taking into consideration the advice and priorities of the Comptroller-General. In preparing their audit work plan, internal auditors consider a number of factors, including which entities have a high number of “observations” in recent government reviews (e.g. those conducted by the state prosecutor’s office). Their yearly audit work plan is submitted to the Comptroller-General every February. Interviews during the OECD fact-finding mission indicated that audits were generally undertaken by the internal auditors from the Office of the Comptroller. However, some of the audits for two large government entities are conducted by the entity’s own internal control unit, which has internal control and audit responsibilities. Nuevo León could reconsider the responsibilities of these internal control units and whether their functions should include both control and audit, since this could compromise their independence.

Nuevo León produces an Annual Audit and Internal Control Programme, which combines internal control and audit activities. Although it is beneficial to have an annual audit work plan, it is better practice to keep audit activities separate from internal control activities.

Internal audit (the third line of defence) helps detect corruption, but its main purpose is to provide objective assurance that risk management and internal controls (the first and second lines of defence) are functioning properly. An effective internal audit function also ensures that internal control deficiencies are identified and communicated in a timely manner to those responsible. Internal audit is also a necessary ingredient for effective accountability and better management. It helps hold officials accountable for their actions and for reporting on performance and management gaps. Institutional responses to negative audit findings and integrity breaches may strongly influence the institutional culture, the tone at the top and the overall effectiveness of the internal control framework.

Typically, there is a clear separation between the internal audit function (the third line of defence) and the second line of defence, which consists of management oversight functions to ensure that first-line controls are properly designed, in place and operating as intended. When senior management considers that it is more efficient for internal audit to perform risk management, compliance or other second line of defence functions as well, it becomes difficult to clearly separate second and third lines of defence.

To avoid institutional conflicts of interest in such cases, public organisations must introduce appropriate safeguards to make sure that the internal audit function is not compromised. For instance, if the internal audit is involved in second line of defence activities, the task of providing assurance on these specific activities must be outsourced either externally or internally, to other departments. The internal audit function should not assume any managerial responsibilities for the matter subject to the audit. In such cases, the internal audit can facilitate and support the actors responsible, but should not take ownership.

Likewise, should internal auditors uncover irregularities that suggest corrupt or fraudulent activity, the case should be forwarded to qualified investigators, whose duties would be to assess whether such fraudulent or corrupt acts have taken place. Once again, to avoid any institutional conflicts of interest and reinforce the internal control framework, auditors should not be responsible for leading internal investigations. Nuevo León could strengthen the independence of its internal audit function by ensuring that it is separate from entity management functions, including implementing internal controls and risk management.

INTOSAI has published a number of documents, including INTOSAI GOV 9100: Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector, citing the importance of independence for internal and external auditors (see Box 6.6).

Ensuring audit institutions are free from undue influence is essential to ensure the objectiveness and legitimacy of their work, and principles of independence are therefore embodied in the most fundamental standards concerning public sector audit. The International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI), for example, has two fundamental declarations citing the importance of independence. Specifically, the Lima Declaration of Guidelines on Auditing Precepts and the Mexico Declaration on Supreme Audit Institution (SAI) Independence draw attention to the importance of organisational, functional and administrative dimensions of independence.

-

Organisational independence is closely related with the SAI leadership, i.e. the SAI head or members of collegial institutions, including security of tenure and legal immunity in the normal discharge of their duties.

-

Functional independence requires that SAIs have a sufficiently broad mandate and full discretion in the discharge of their assignments, including sufficient access to information and powers of investigation. Functional independence also requires that SAIs have the freedom to plan audit work, to decide on the content and timing of audit reports and to publish and disseminate them.

-

Administrative independence requires that SAIs be provided appropriate human, material and financial resources as well as the autonomy to use these resources as they see fit.

Independence is equally important for internal audit institutions. INTOSAI GOV 9100 – Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector and INTOSAI GOV 9120 – Internal Control: Providing a Foundation for Accountability in Government both cite the importance of the independence of internal auditors from an organisation’s management: “For an internal audit function to be effective, it is essential that the internal audit staff be independent from management, work in an unbiased, correct and honest way and that they report directly to the highest level of authority within the organisation. This allows the internal auditors to present unbiased opinions on their assessments of internal control and objectively present proposals aimed at correcting the revealed shortcomings.”

More specific guidelines on independence are provided in INTOSAI GOV 9140 – Internal Audit Independence in the Public Sector, which adopts principles from International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI) 1610 (Using the Work of Internal Auditors) in defining independence. Criteria in both documents include whether the internal audit institution is established by legislation; reports directly to top management; has segregated responsibilities from management; has clear and formally defined responsibilities; has adequate freedom in developing audit plans; and is involved in the recruitment of its own audit staff.

Sources: (INTOSAI, 1977[13]; 2001[14]; 2007[15]; 2010[2]; 2010[16]).

Proposals for action

Nuevo León has launched its own anti-corruption system and has a number of elements of an internal control and risk management in place. However, more could be done to build capacity in the internal control and risk management environment. Specific proposals for action that Nuevo León could consider are outlined below.

A control environment with clear objectives

-

Nuevo León should ensure that its control environment and organisational structure support its internal control and risk management framework.

-

Nuevo León could ensure that all staff receive training on the internal control and risk management framework, to promote consistent implementation.

-

Nuevo León could apply the principles of the “three lines of defence” model to give greater responsibility for internal control and risk management to operational management.

A strategic approach to risk management

-

Nuevo León could implement a strategic risk management framework to strengthen the internal control framework and improve management of the risk of fraud and corruption.

-

Nuevo León could operationalise the risk management framework by assigning clear responsibility for the management of risk to senior managers, providing training for staff and updating risk management systems and tools.

Coherent control mechanisms

-

Nuevo León could strengthen and integrate its internal control activities to ensure that reasonable assurance is provided.

-

Nuevo León could ensure that each internal control serves a purpose and that the overall system is monitored, ethical and efficient.

-

Nuevo León could consider making better use of its internal control reporting function for identifying issues and risks and reporting on them to management.

An effective and separate internal audit function

-

Nuevo León could consider investing in training, tools and methodologies for internal audit staff to improve the quality and efficiency of audits.

-

Nuevo León could ensure that its central co-ordination of internal audit leverages available resources to enhance oversight and enable a cohesive response to integrity risks.

-

Nuevo León could build on its internal control training programme to provide further training on ethics and integrity for internal auditors.

-

Nuevo León could strengthen mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations.

-

Nuevo León could strengthen the independence of its internal audit function by ensuring it is separate from entity management functions, including the implementation of internal controls and risk management.

References

[9] Department of Finance (2016), “Building risk management capability”, https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/comcover-information-sheet-building-risk-management-capability.pdf.

[5] European Commission (2014), Compendium of the Public Internal Control Systems in the EU Member States (second edition), http://ec.europa.eu/budget/pic/lib/book/compendium/HTML/index.html.

[8] GAO (2015), “A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs”, No. GAO-15-593SP, http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/671664.pdf.

[3] Institute of Internal Auditors (2013), IIA Position Paper: The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control, https://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/Public%20Documents/PP%20The%20Three%20Lines%20of%20Defense%20in%20Effective%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Control.pdf.

[2] INTOSAI (2010), “Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector”, INTOSAI Guidance for Good Governance, No. GOV 9100, http://www.issai.org/en_us/site-issai/issai-framework/intosai-gov.htm.

[16] INTOSAI (2010), “Internal Audit Independence in the Public Sector”, No. 9140, http://www.issai.org.

[15] INTOSAI (2007), “Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence”, International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), No. 10, INTOSAI Professional Standard Committee Secretariat, Copenhagen, http://www.issai.org.

[14] INTOSAI (2001), “Internal Control: Providing a Foundation for Accountability in Government”, No. GOV 9120, http://www.issai.org/en_us/site-issai/issai-framework/intosai-gov.htm.

[13] INTOSAI (1977), “Lima Declaration of Guidelines on Auditing Precepts”, International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI) , No. 1, INTOSAI Professional Standard Committee Secretariat, Copenhagen, http://www.issai.org.

[7] ISO (2009), ISO 31000-2009 Risk Management, https://www.iso.org/iso-31000-risk-management.html.

[10] OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

[1] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf.

[6] OECD (2013), “OECD Integrity Review of Italy: Strengthening integrity in the Italian public sector”, in OECD Public Governance Reviews, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264193819-4-en.

[4] OECD Working Party of Senior Budget Officials (2015), “Budget reform before and after the global financial crisis, 36th Annual OECD Senior Budget Officials Meeting”, http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=GOV/PGC/SBO(2015)7&docLanguage=En.

[12] Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia (2014), Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation of Recommendations from Recent Reports, http://www.bcauditor.com/sites/default/files/publications/2014/report_19/report/OAGBC%20Follow-up%20Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 01 August 2017).

[11] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2014), Internal Audit, https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/corporate/organization/internal-audit.html.