Chapter 2. Strengthening Nuevo León’s strategic approach to public integrity

A strategic approach to integrity, based on evidence and on addressing at-risk areas is an essential element to develop a comprehensive and effective integrity system. This chapter assesses the mechanisms for monitoring, evaluating and reviewing Nuevo León’s strategic efforts to prevent corruption, as laid down in its strategic and development plans. This chapter describes the comprehensive and participatory work of the Nuevo León Strategic Planning Council, which guides the state’s broad strategic development. It provides recommendations for improving the integrity and anti-corruption strategy, for example by clearly defining objectives and identifying additional indicators. Furthermore, it addresses the strategic role that the Nuevo León Anti-corruption System (Sistema Estatal Anticorrupción para el Estado de Nuevo León, or SEANL) can play in supporting the state integrity strategy as it develops and monitors its integrity policies.

2.1. Introduction

A key element for building a strategic approach to public integrity is measuring and evaluating integrity policies. Evidence is needed to understand what works and why, and to improve policies to achieve strategic goals. Collecting data on what has and what has not been achieved can help guide further action and increase accountability, providing stakeholders basic evidence of the progress made as a result of proposed action and high-level commitment (OECD, 2017[1]).

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity acknowledges the need to build an evidence-based, strategic approach to public integrity by:

-

a. setting strategic objectives and priorities for the public integrity system, based on a risk-based approach to violations of public integrity standards, and that takes into account factors that contribute to effective public integrity policies;

-

b. developing benchmarks and indicators and gathering credible and relevant data on the level of implementation, performance and overall effectiveness of the public integrity system (OECD, 2017[2]).

This chapter assesses Nuevo León’s Strategic Planning Council (Consejo Nuevo León para la Planeación Estratégica), whose task is to design, implement and evaluate a comprehensive strategy for the state, including on integrity-related issues. It also addresses the role of Nuevo León’s Anti-corruption System (Sistema Estatal Anticorrupción para el Estado de Nuevo León, or SEANL), which is not only in charge of co-ordinating institutions across every level of government, but has the primary responsibility for designing the state’s integrity policy.

2.2. Reinforcing the strategy to prevent corruption

2.2.1. The Nuevo León Strategic Planning Council’s task of drafting an integrity and anti-corruption strategy could be enhanced by setting clear objectives and formulating new indicators.

Since 2013, Nuevo León has built a comprehensive system for strategic planning and evaluation led by the Council for Strategic Planning of Nuevo León (Consejo Nuevo León para la Planeación Estratégica, or Nuevo León Council). In this public body, representatives of government, civil society and the university are working together on the sustainable development in the state, with the ultimate vision of making Nuevo León “the best place to live”. The Council defines itself as a non-partisan, advisory body of the executive branch in matters of strategic planning and its evaluation. It is intended to be guided by a long-term strategy that extends beyond the political cycle (transsexenal). It is composed of 16 voting members (representing citizens and the universities, as well as the state and federal governments), as well as a technical secretary and non-voting expert advisers. Created under the Strategic Planning Law for the State of Nuevo León (Ley de Planeación Estratégica del Estado de Nuevo León), the Nuevo León Council was asked to elaborate a long-term strategic plan for the governor of Nuevo León. This was intended to serve as a reference for drawing up the medium-term plan for the governor’s term of office. Both the Strategic Plan (Plan Estratégico para el Estado de Nuevo León 2015-2030) and the Development Plan (Plan Estatal de Desarrollo 2015-2021) were released in parallel in April 2016, after an extensive collaborative effort that involved multidisciplinary experts and wide social participation.

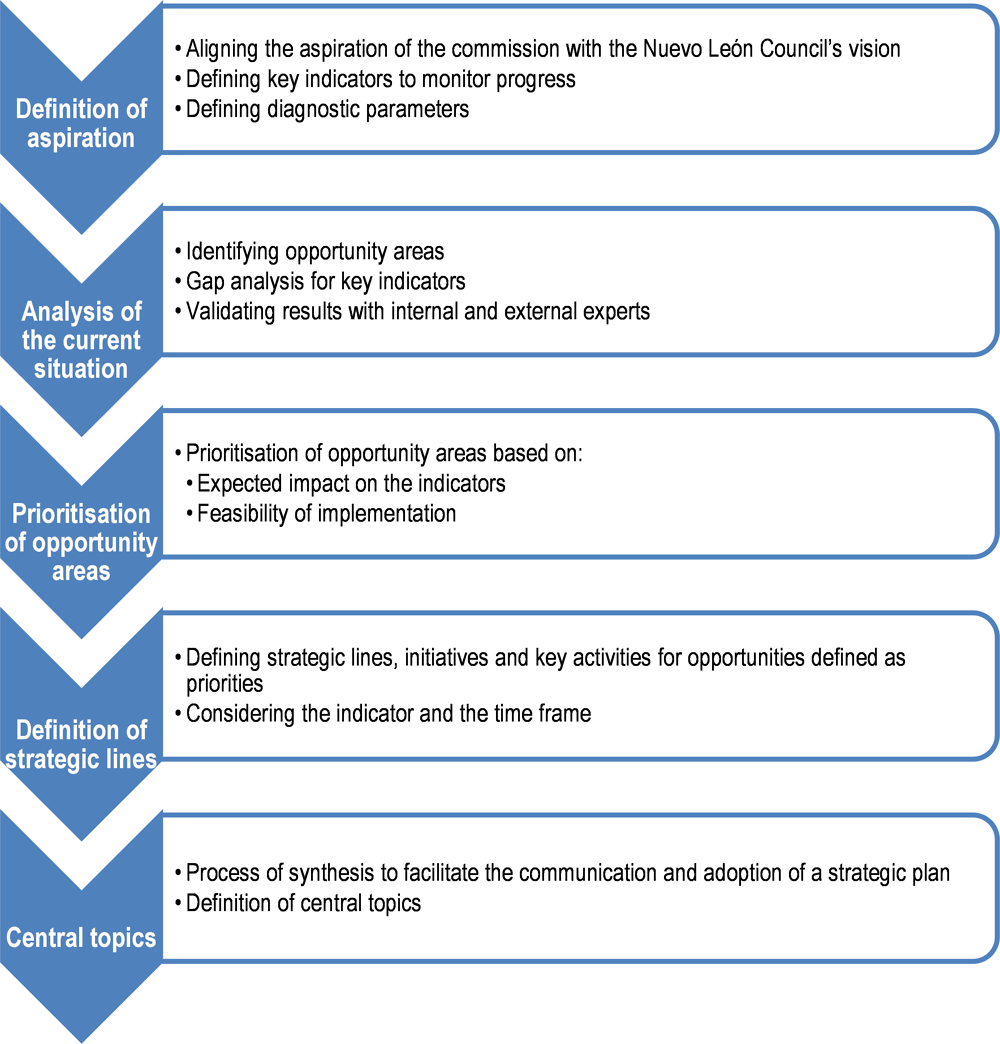

One of the pillars of the work of the Nuevo León Council is “Effective and Transparent Government” (Gobierno eficaz y transparente) which was identified as one of the main priorities of the state, together with Human Development, Sustainable Development, Economic Development, as well as Security and Justice. For each pillar, a commission was established, and each helped develop a strategic plan in a comprehensive, five-stage process resulting in a number of so-called “strategic lines” (líneas estratégicas) (Figure 2.1).

As a result of this work, the Effective and Transparent Government Commission (Comisión Gobierno Eficaz y Transparente) was given the task of working on transparency and the fight against corruption. This was identified as one of the central issues in the public consultation process, where it emerged as one of the top priorities. In addition, 47 high-priority opportunities were identified in the Strategic Plan (Table 2.1), three of which were associated with integrity and anti-corruption, namely:

-

Identify and eliminate causes, conditions and factors of corruption.

-

Establish processes for the detection and investigation of acts of corruption.

-

Impose penalties and apply consequences under strict adherence to the law.

Furthermore, the Strategic Plan identifies several strategic projects also related to integrity, including:

-

Create an independent anti-corruption commission with the authority to investigate, report misconducts and impose administrative sanctions.

-

Define the technical requirements for the Superior Auditor of the State of Nuevo León and modify the appointment process to ensure his/her independence and effectiveness. Involve citizens to propose candidates and establish a deadline for making the decision.

-

Support the appointment of an anti-corruption prosecutor and representatives of the Administrative Justice Tribunal.

Considering the idea to align Nuevo León’s long-term and medium-term plans, transparency and the fight against corruption were also identified as priorities in the State Development Plan, which contains one relevant objective (Table 2.1) composed of three strategies, together with a number of “lines of action” (líneas de acción) for each strategy (Box 2.1). The State Development Plan also identified priority programmes that it described as addressing the “most important needs of society”, including:

-

a culture of reporting and investigation;

-

transparency and accountability;

-

the state anti-corruption system;

-

a Specialised Anti-corruption Prosecutor’s Office.

Objective 3: Ensure transparency in public affairs, encourage accountability and combat corruption.

Strategy 3.1: Strengthen mechanisms for transparency and accountability.

Lines of action

3.1.1. Design and operate a comprehensive system that assures the citizen full exercise of the right of access to information and accountability.

3.1.2. Supervise the execution of public resources of the State Government.

3.1.3. Strengthen the structure and functioning of internal institutional control bodies.

3.1.4. Adapt the legal framework to increase transparency and effective accountability, and impose penalties where necessary.

Strategy 3.2: Monitor the fulfilment of the responsibilities and obligations of public service personnel.

Lines of action

3.2.1. Institutionalize mechanisms to encourage a culture of transparency and accountability in the state public service. Effective and transparent government.

3.2.2. Strengthen the instruments for presenting and analysing financial statements.

Strategy 3.3: Encourage institutional collaboration between the government and the oversight bodies of the three branches of government.

Lines of action

3.3.1. Strengthen the internal processes of communication and collaboration, to enhance transparency and accountability.

3.3.2. Promote the implementation of collaboration agreements between governmental institutions of the three branches of government and non-governmental organisations on transparency and accountability.

Strategy 3.4: Consolidate the State Anti-corruption System.

Lines of action

3.4.1. Prevent, identify and combat illicit conduct and administrative misconduct by public servants.

3.4.2. Ensure effective co-ordination with specialised courts and state and national anti-corruption systems.

3.4.3. Conduct targeted audits of the strategic areas of the state public administration, ensure their resolutions are binding, and set up an integrated internal control framework.

3.4.4. Promote citizen complaints through witness protection, anonymity, confidentiality and the integrity of evidence in anti-corruption investigations.

Source: (Nuevo León Council, 2016[4]).

Both the Strategic and Development Plans include a commendably extensive analysis and diagnosis of the current situation. These are informed by several surveys and statistics from domestic and international sources, such as Mexico’s National Institute for Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, or INEGI), the Federal Electoral Institute (Instituto Federal Electoral, or IFE), the World Bank, Transparency International, the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, or CIDE), and the World Economic Forum. Indicators to measure progress towards high-priority objectives of the Strategic Plan and objectives of the Development Plan have been selected (Table 2.1). These are measured and assessed by the Nuevo León Council, which drafts an annual report that includes a qualitative analysis of advancement of strategic projects and priority programmes, identified in the corresponding strategic documents. Further accountability for the achievement of the government’s strategy is ensured by the fact that a report on the implementation of the State Development Plan is included in the Executive’s Annual Report (Informe de Gobierno). This includes results on the progress of the strategic projects and the priority programmes, as well as an update on the economic and social development of the state.

The creation and the work of the Nuevo León Council, the development of Strategic and Development Plans, and a follow-up mechanism all represent solid progress toward constructing a strategic approach to public integrity, both in terms of process and content. First, it shows strong political will to define a long-term and comprehensive strategy for the state with substantial participation from external stakeholders. Furthermore, it is based on sound analysis and evidence, which reinforce the legitimacy of the state’s strategic action. Its working methodology is also laudable. The Nuevo León Council works towards the achievement of goals, programmes and cross-cutting priorities, monitored by a mix of both qualitative and quantitative indicators.

To enhance its strategy and evaluation of its progress, the Nuevo León Council and, in particular, its Effective and Transparent Government Commission could further support its overarching goals with a set of objectives which, in spite of the terminology used, seem to be missing and should define the implications of a goal in a specific context. While a goal reflects the change the strategy (or the policy) wants to induce, objectives define the implications of a goal in a specific context and should phrase one aspect of a goal positively and unambiguously in one sentence, providing the “who, when, what and where of a goal” (OECD, 2017[1]). Furthermore, the evaluation function of Nuevo León Council’s strategy would benefit from defining goals (but also objectives and indicators) not only at the outcome level, as they are defined currently, but also at the output and intermediate outcome levels. While outcomes are the indirect results of a strategy (or policy) in the final sphere of desired impact, outputs are the direct results in the sphere immediately affected by the strategy (or policy), and intermediate outcomes result from the policy at the first step of corollary inference (Box 2.2).

When a policy is instituted, it has immediate and more remote effects. For purposes of measurement, effects are generally differentiated at the level of output, intermediate outcomes and outcome.

Consider the example of a whistle-blowing mechanism. The existence of the mechanism is an obvious output of such a policy. This is no reason to quickly leave the output level behind, as there might be specific qualities of the output worth investigating. Is the mechanism implemented with complementary measures, such as awareness-raising campaigns? Is whistle-blower protection also provided?

To capture more than the on-paper (de jure) implementation of the whistle-blowing mechanism, monitoring could also look at the intermediate outcome level: Are staff using the whistle-blower mechanism? Are they familiar with the procedure?

To assess if the whistle-blowing policy has been effective, the outcome level should be considered. Has a culture of integrity and accountability been established, in which staff are comfortable reporting fraud, misconduct and corruption?

Source: (OECD, 2017[1]).

2.2.2. The SEANL should establish close collaboration with the National Anti-corruption System and the Nuevo León Council, to ensure coherence of the integrity policies with the other relevant strategies on integrity.

In Nuevo León, the creation of the Nuevo León Anti-corruption System (Sistema Estatal Anticorrupción para el Estado de Nuevo León, or SEANL) in June 2017 provided an unprecedented opportunity to develop comprehensive policies on integrity and anti-corruption issues. One of the key responsibilities of the Co-ordination Committee is to design, promote and approve the state’s anti-corruption policies, as well as to establish a methodology to assess, adjust and modify them. A central role is also played by the Executive Secretariat, which is charged with elaborating the technical proposals and the policies to the Co-ordination Committee but also the methodology to measure and to follow them up based on acknowledged and reliable indicators under the Local Anti-corruption System Law (Ley del Sistema Estatal Anticorrupción para el Estado de Nuevo León) (see Chapter 1).

To leverage the strategic role of the recently created anti-corruption system in drafting state integrity policies, all the constituent bodies of the SEANL should work in close collaboration with the National Anti-corruption System (SNAC). In June 2018, the SNAC presented the first draft of the National Anti-corruption Policy. Meanwhile, the Nuevo León Council should ensure coherence with the goals, objectives and indicators laid out in the state’s strategic and development documents. Furthermore, a continuous channel of communication and mutual learning with both the SNAC’s bodies and the Nuevo León Council should be in place to allow for exchange of the results of the data-collecting activity. In this way, full advantage can be taken of the institutionalised learning and creation of objective knowledge that emerges from monitoring and evaluation (OECD, 2017[1]).

When discussing strategy and policies, as well as their monitoring and evaluation, the Executive Secretariat of the Nuevo León Council, which is in charge of providing technical input to the SEANL’s Co-ordination Committee, should formally involve the members of its Effective and Transparent Government Commission. This co-ordination could be particularly fruitful when drafting the state integrity policies, so the Nuevo León Council can share its insights on the in-depth analytical and diagnostic work done for preparing the Strategic and Development documents. From an organisational perspective, the collaboration could take place within the consultative sub-commission dealing with prevention issues presented and proposed in Chapter 1. In these meetings it would also be highly relevant to involve the Executive Agency for the Co-ordination of the State’s Public Administration (Coordinación Ejecutiva de la Administración Pública del Estado), which has already played a key role in ensuring coherence and co-ordination between Nuevo León’s Strategic and Development Plans. Its working methodology could well serve as an example that the Executive Secretariat could follow (Box 2.3).

Nuevo León’s Strategic Plan sets out the state’s long-term (15-year) vision, as well as its objectives, economic and social development strategies and strategic projects. The State Development Plan identifies medium-term priorities for the development of the state, and the strategies and lines of action that the executive branch will put into effect to achieve them. It also defines its priority programmes, setting out indicators of economic and social development. According to Article 15 of the Law of Strategic Planning of the State of Nuevo León, the Strategic Plan shall serve as a basis for elaborating the State Development Plan. For this purpose, a process was carried out to ensure the consistency of the objectives, strategies, lines of action and key projects between the two documents. Members of the Nuevo León Council and high-level government officials met on 29 occasions between 4 October 2015 and 31 March 2016. A key role was played by the Executive Agency for the Co-ordination of the State’s Public Administration that, through the Directorate on Co-ordination of Public Policies, established a planning strategy through joint working groups involving high-level officials of the government entities, and inviting experts from civil society and the university to establish a dialogue and build a shared vision of future challenges, risks and strategies to achieve the objectives. Likewise, agreements were established to jointly carry out public consultations for both plans. Their meetings have continued after the release of the two strategic documents, to periodically follow up on the implementation of the strategies and projects.

Source: Law of Strategic Planning of the State of Nuevo León; (Nuevo León Council, 2017[5]).

2.2.3. The SEANL should define an action plan to implement its policies, assigning clear roles and responsibilities to public entities.

The success and effectiveness of the SEANL depends to a great extent on how active its members are in providing necessary information, and carrying out its policies. It is crucial that every entity in the public administration contributes, by embracing a strategic approach to public integrity. The state’s strategy and policies should thus translate into plans at the entity level, considering context-specific factors (e.g. sector, activities, risk, etc.), while adhering to the overall goals and objectives.

Given the pivotal role of the SEANL in co-ordinating Nuevo León’s institutions, its Co-ordination Committee could add another task as it defines the state’s integrity policies: drawing up an action plan that lays out which entity is responsible for different tasks and the timelines for implementing them. It could also follow up on the level of compliance and reporting on the level of implementation, based on the responsibilities provided for in the SEANL Law (Article 9 (VI) and (VIII)).

Each entity could be asked to identify the most suitable way for it to comply with the general action plan, depending on the specific organisation, and its priorities and risks. The Co-ordination Committee could also thus consider requiring that all ministries – starting with the ones that are considered most at risk for corruption – set up their own plans, in line with the practice of OECD member and partner countries (Box 2.4). It would then make sure that they are aligned with its general action plan, providing guidance as these plans are drafted.

Several OECD member and partner countries require that individual line ministries or departments prepare corruption prevention plans that are tailored to their organisation’s specific internal and external risks. Every organisation is different, and risks for fraud and corruption vary depending on its mandate, personnel, budget, infrastructure or IT use. For example, line ministries responsible for transferring social benefits face higher risks of fraud; likewise, departments with higher public procurement spending (e.g. health or defence) may face a risk of corruption associated with this activity. In addition to ensuring that prevention policies are developed on a risk-based approach, such plans also help ensure that, where relevant, organisations’ anti-corruption efforts are aligned with national and sectorial strategies.

Some countries thus complement their national anti-corruption plans with organisational-level strategies. In Latvia, for example, each ministry has a corruption prevention plan, with oversight from the national anti-corruption agency, or Corruption Prevention and Combating Bureau (the KNAB).

In Lithuania, the Special Investigation Service (SIS), an independent anti-corruption law enforcement body, is responsible for monitoring the National Anti-corruption Programme, along with the Interdepartmental Commission on Fighting Corruption, led by the Department of Justice. The SIS co-ordinates risk management activities throughout the public sector, by requiring each public institution to design its own risk map, which is submitted to the SIS for review. The SIS provides guidance and comments on improving these plans.

In Slovenia, the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption supports organisations in their development of unique integrity plans, which identify, analyse and evaluate risks and propose appropriate mitigation measures. The Commission urges departments to adopt an inclusive approach in developing their plans, since they were found to be an effective way of communicating shared values and enhancing an understanding of integrity. The Commission provides guidance, including sample integrity plans, on its website.

The United States’ Office of Government Ethics (OGE) conducts reviews on government agencies’ ethics programmes about once every four years. These Ethics Programme Reviews are OGE’s primary means of conducting systemic oversight of the ethics programme established by the executive branch. The Compliance Division’s Programme Review Branch conducts ethics programme reviews at each of the more than 130 executive branch agencies. This helps ensure consistent, sustainable ethics programmes and compliance with established executive branch ethics laws, regulations and policies. The division also provides recommendations for meaningful programme improvement. Individual reviews identify and report on the strengths and weaknesses of an agency’s ethics programme, by evaluating 1) agency compliance with ethics requirements as set forth in relevant laws, regulations, and policies; and 2) ethics-related systems, processes and procedures for administering the programme.

In Colombia, individual organisations are required to establish their own risk maps and anti-corruption plans. The Anti-Corruption Statute directs public entities of all orders to produce a strategy at least annually to combat corruption and improve citizen service. These plans are based on the criteria defined by the Ministry of Transparency of the Presidency of the Republic.

Sources: OECD Integrity Review of Mexico City (forthcoming), (OECD, 2017[6]), (OECD, 2017[7]), OECD accession report of Lithuania (not published), OECD accession report of Latvia (not published) and (U.S. Office of Government Ethics, n.d.[8]).

Plans at the entity level could be integrated into the entity’s Annual Operational Programmes or Budgetary Programmes (Programas Operativos Anuales or Programas Presupuestarios). Their consistency with the overall strategy is ensured by the fact that they should align with the objectives of the Development Plan and of the Regional and Special Sectoral Programmes (Programas sectoriales regionales y especiales), under the Nuevo León Strategic Planning Law (Ley de Planeación Estratégica del Estado de Nuevo León). At the same time, including the integrity plans in the Annual Operational Programmes would ensure they are part of a monitoring and evaluation system that includes information on progress and achievements, and oversees the goals and objectives of the programmes deriving from the State Development Plan (the Planning, Programming and Budgeting System, Sistema Integral de Planeación, Programación y Presupuestación) (Nuevo León Council, 2016[4]). A key player in this process is the Executive Agency for the Co-ordination of the State’s Public Administration (Coordinación Ejecutiva de la Administración Pública del Estado), which co-ordinates the monitoring and evaluation activity associated with the Development Plan and should therefore be fully part of the discussion over the ministerial plans within the technical discussion in the Executive Secretariat, as also suggested in previous section.

2.3. Operationalising monitoring and evaluation

2.3.1. The SEANL’s methodology for monitoring Nuevo León’s integrity policies should clearly define goals, objectives and indicators. It could be tested in the policy to set high standards of conduct for public officials.

A key element in setting up strategic monitoring of integrity policies is designing a good operationalisation of what is to be achieved into relevant objectives and of what is being measured into valid indicators. Each policy typically has one or many goals that reflect the desired change. These should be translated into objectives, defining the implications of a goal in a specific context. Indicators, in turn, measure whether an objective is fulfilled, and provide measures that the objectives concrete (OECD, 2017[1]). Furthermore, goals, objectives and indicators can be defined on output as well as outcome levels, operating on multiple levels (Figure 2.2).

The SEANL is responsible for developing a methodology to measure and follow up the development of the state’s integrity policies. It is crucial that the responsible bodies, that is, the Co-ordination Committee upon proposal of the Executive Secretariat, carefully design how the different steps will proceed, and base this process on reliable and valid data. Indicators should be a valid measurement of objectives, for example, and objectives should be valid measurements of goals.

An example of strategic operationalisation is provided in Table 2.2, in association with Principle 4 of the 2017 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity on setting high standards of conduct for public officials. One measure commonly used for this purpose is an Integrity Code for public officials.

To monitor progress in the implementation of its integrity framework, the Ministry of Administration (Secretaría de Administración) is creating a programme, within the performance assessment system, to determine the level of ethical understanding among public officials, and to define any gap between their expected and their actual conduct. Based on the results of this programme, the Ministry of Administration will build an appropriate training programme to promote common understanding of the current integrity rules. Training sessions are also organised by the Anti-corruption Unit, in a three-part training programme (covering awareness, consolidation and implementation) carried out by a network of 500 “Agents of Change”. The goal is to have reached 40 000 public officials in the state by June 2019 (see Chapter 3).

While these initiatives are commendable, and help to assess how well integrity instruments have been assimilated, no operationalised methodology has apparently been proposed for monitoring relevant developments. The SEANL could thus test its monitoring methodology on this key policy by defining goals, objectives and indicators at the output, intermediate outcome and outcome level, as shown in the example above. In drafting the methodology, the SEANL bodies could consider conducting co-ordinating studies or surveys to measure the level of awareness of integrity among its public officials, measuring changes over time and identifying any challenges. International experience provides examples on how to measure the implementation of an ethics code using employee surveys, for example in Poland (Box 2.5) or in Canada in the context of the Public Service Employee Survey. In some cases, surveys are distributed after training sessions to measure their impact and eventually, to improve them. The preparation and evaluation of surveys and, more generally, the monitoring of integrity instruments could be carried out by a proposed central Ethics Unit in the Office of the Comptroller and Governmental Transparency. This would be the entity in charge of developing, promoting and implementing the integrity rules (see Chapter 3).

In Poland in 2014, a survey, known as the monitoring of “Ordinance No. 70 of the Prime Minister dated 6 October 2011, on the guidelines for compliance with the rules of the civil service and on the principles of the civil service code of ethics, was commissioned by the head of the Civil Service (HCS). The HCS is the central government administration body in charge of civil service issues, under the Chancellery of the Prime Minister. The survey was given to three groups of respondents:

1) members of the civil service corps

This survey examined, on the one hand, how far the ordinance had been implemented in their respective offices and, on the other hand, the civil servants’ subjective assessment of the functioning of the ordinance. The members of the civil service corps completed a survey of 16 questions (most framed as closed questions, with a few allowing for comments). The questions concerned issues including:

-

knowledge of the principles laid out in the Ordinance;

-

the effect of the Ordinance on changes in the civil service;

-

the need/advisability of expanding the list by adding new rules;

-

the comprehensibility/clarity of the guidelines and principles on which the Ordinance is based; and how useful the Ordinance is for resolving professional dilemmas.

The survey also assessed the civil servants’ comprehension of the principles of “selflessness” and “dignified conduct” and the need for training in compliance. Surveys were available on the Civil Service Department website. Respondents were asked to submit the survey electronically to a dedicated e-mail address.

2) directors-General, directors of treasury offices, and directors of tax audit offices

This survey was intended to verify the scope and manner of implementation of tasks for which the officials were responsible under the provisions of the ordinance, including, for example:

-

the way in which compliance with the rules in the given office is ensured;

-

information on whether the applicable principles were complied with in decisions authorising members of the civil service corps to undertake additional employment, or authorising high-ranking civil service employees to undertake income-generating activities;

-

the way in which the given principles are embodied in the human resources management programmes being developed;

-

the way the relevant principles were taken into account in determining the scope of the preparatory service stage.

3) independent experts (public administration theorists and practitioners)

This survey was intended to obtain an additional, independent specialist assessment of the functioning of ethical regulations in the civil service, to obtain suggestions on the ethical principles applicable to civil service and to identify the aspects of the management process that might need to be further supplemented or updated, clarified or emphasised or even corrected or elaborated.

The response rate differed across the three groups. The HCS received 1 291 surveys completed by members of the civil service corps (the number of completed surveys represented approximately 1% of all civil service corps members), 107 surveys dedicated to the directors (that is, 100% of all directors-general, directors of treasury offices and directors of tax audit offices (98 in total). Other surveys submitted on a voluntary basis by the head of the tax offices, and seven replies from independent experts, or approximately 13% of all experts invited to the study, were also received. These surveys were the first to be conducted on such a large scale, and the data gathered could be used to enhance the integrity policy in Poland’s civil service system.

Source: Adapted from the presentation by the Polish Chancellery of the Prime Minister at the OECD workshop in Bratislava in 2015.

2.3.2. The SEANL should align the design of the integrity policies with the strategic outline of their measurement.

Monitoring not only makes it possible to measure the effectiveness of a given policy, but creates a base of institutionalised organisational learning and knowledge that can be used for policies and for government entities (OECD, 2017[1]). Internal stakeholders should also be invited to set up a monitoring system at an early stage in the planning process, since they are best placed to identify the evidence needed and to discuss the purpose of the measurement. Those who are to implement and design a policy should in particular be consulted in this process since the former can offer information on which measurement is feasible, while the latter are close to the intentions and expectations associated with the policy.

The architecture of the SEANL facilitates a horizontal discussion with a range of institutions responsible for corruption prevention and enforcement. Formal mechanisms should be established for receiving input from those in charge of designing and implementing integrity policies, in particular the various Directorates in the Office of the Comptroller and Governmental Transparency (Contraloría y Transparencia Gubernamental) (Table 2.3). The most appropriate venue for such a discussion might be the consultative sub-commission on prevention in the Executive Secretariat, proposed in Chapter 1. This could enhance technical discussion of SEANL’s decisions and initiatives.

Technical consultation with those who design and implement policy should address the data, scope and time frame of the measurement, to make sure it is consistent with its defined purpose and the designated users. Just as with evaluation, effective monitoring depends on its being “designed, conducted, and reported with a sense of purpose and meets the needs of the intended users” (Johnsøn; Hechler; De Sousa; Mathisen, 2011[9]). The discussion could address methodology, including the potential alignment of the measurement with existing or future data collection. The strategic outline of the monitoring system should consider the existing data collection of the Anti-corruption Unit. The unit regularly publishes a report compiling statistics related to the progress of the actions and strategies (acciones y estratégias) of the Anti-corruption Plan (Plan Anticorrupción) (Table 2.4). Although the data collection activity of the Anti-corruption Unit is commendable and provides a useful overview of the results on some of the state’s preventive and remedial actions, the data provide only a static picture of the efforts so far. They do not at present serve as useful indicators, because the Anti-corruption plan does not clearly link them to its goals. They are also not operationalised into output, intermediate outcome and outcome levels. The SEANL, which has competence to define both the policies and methodology for the corresponding indicators, could nevertheless take them into consideration. If they are deemed relevant for the measurement’s overall purpose, this data could be used to help design the monitoring system, for instance by using them as indicators for the goals and objectives of certain policies. The data on trained staff, for example, could serve as an output indicator for a policy to establish integrity as an organisational value (see Box 2.3).

The SEANL’s Executive Secretariat could also consider other elements to define the scope of the strategic outline of the measurement. These would include the most relevant policies and functions of the integrity system, whose monitoring is key to ensure its implementation and assessment. The Executive Secretariat could consider the most typical subjects of scrutiny by central governments in OECD countries, which include the existence and quality of codes of conduct, fraud risk-mapping exercises, as well as the existence of conflict of interest and asset declaration policies, and how well they are complied with (Table 2.5).

2.3.3. The Nuevo León Council could be charged with evaluating the SEANL’s integrity policies and proposing recommendations for consideration by the SEANL’s Co-ordination Committee.

To fully assess the social, economic and societal impacts of a policy, monitoring is not enough. It should be complemented by a system that can evaluate it by investigating the effects that it has, with a causal attribution. Monitoring focuses on the policy’s direct and intermediate outcomes, while evaluation determines the relevance, efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability of a planned, ongoing, or completed intervention, to incorporate lessons learned into the decision-making process (Zall Kusek and Rist, 2004[14]; OECD, 2010[15]; OECD/DAC, 1991[16]). More specifically, data gleaned in an evaluation can be used to inform broader political strategy and design issues (“Are we doing the right things?”), operational and implementation issues (“Are we doing things right?”), and whether better ways of approaching the problem might be found (“What are we learning?”) (Box 2.6). Notwithstanding its purpose, creating a system of evaluation also requires its operationalisation into goals, objectives, and indicators at the outcome level (Figure 2.2).

Evaluation provides information on:

-

Strategy: Are the right things being done?

-

rationale or justification

-

clear theory of change

-

-

Operations: Are things being done correctly?

-

effectiveness in achieving expected outcomes

-

efficiency in optimising resources

-

client satisfaction

-

-

Learning: Are there better ways?

-

alternatives

-

best practices

-

lessons learned

-

Source: (Zall Kusek and Rist, 2004[14]).

While the SEANL Law formally gives the Co-ordination Committee authority to define the “evaluation” (evaluación) of the state integrity policies, this task should be primarily seen as monitoring. Its results are to be included in the Co-ordination Committee’s annual report, whose time frame is incompatible with the evaluation of a policy’s long-term objective. A long-term objective calls for a long-term, extended time frame and targeted evaluation (OECD, 2017[1]). The policy-making task of the Co-ordination Committee, moreover, prevents it from undertaking the “accountability” function of the evaluation phase, which should be based on information of the following characteristics:

-

Impartiality: The information should be complete, comprehensive and free of political or other bias and deliberate distortion.

-

Stakeholder involvement: Relevant stakeholders should be genuinely consulted and involved throughout the evaluation process, so that they trust the information, take ownership of the findings, and translate them into ongoing and new policies, programmes and projects.

-

Usefulness: Information should be useful, meeting the purpose of the evaluation, as well as being relevant, timely and conveyed in an easily comprehensible fashion.

-

Technical adequacy: The information should comply with relevant technical standards, such as appropriate design and sampling procedures, accurate wording of questionnaires and interview guides, appropriate statistical or content analysis, and adequate support for conclusions and recommendations.

-

Value for money: The cost of the evaluation efforts should be proportionate to the overall cost of the initiative.

-

Feedback and dissemination: The evaluation information should be shared and communicated in an appropriate, targeted and timely fashion (Zall Kusek and Rist, 2004[14]).

The role, composition and experience of the Nuevo León Council can help it ensure that the collection of information for evaluation best responds to these characteristics. It could thus be assigned the responsibility to evaluate the SEANL integrity policies. First, the participation of representatives from government, civil society and academia ensures that the views, expertise and perspectives of a wide range of stakeholders are taken into account, helping to ensure an objective approach to the gathering and assessment of information. The collection of additional data from ministries or entities could be facilitated by the SEANL’s Co-ordination Committee. This has the broad authority to request integrity-related information from public entities (Article 9 (XI) of the SEANL Law). In addition, the data collection can be supported by the Executive Agency for Co-ordination of the State’s Public Administration, which already co-ordinates monitoring and evaluation linked to the Development Plan.

Second, the Nuevo León Council has taken a leading role in shaping Nuevo León’s strategic vision, which leaves it in an ideal position to gather relevant information to understand and evaluate where, when and how change can be expected.

Third, Nuevo León Council already has the responsibility for evaluating the achievement of the goals and objectives set out in the Strategic and Development Plans (Article 9 of the Strategic Planning Law), including those related to transparency and the fight against corruption (Box 2.1). In evaluating the state integrity policies, the Nuevo León Council could leverage technical experience of many years, and easily integrate it into its ongoing working methodology. The Council’s annual report already addresses the SEANL together with the other priority programmes identified in the Development Plan (No. 21) under assessment. However, the assessment of this kind of programmes consists only of an analysis of developments, while the evaluation activity over the SEANL’s integrity policies should be based on a set of indicators.

Lastly, the Nuevo León Council publishes its reports and offers recommendations, which allows for accountability and legitimacy of the state’s efforts. If the Nuevo León Council is granted responsibility for the SEANL, additional mechanisms could be set up to increase the impact of its recommendations, for instance by ensuring that the SEANL discusses them and votes on whether to make them binding, as provided for under Article 51 of the SEANL Law.

Proposals for action

In recent years, Nuevo León has taken significant steps toward developing a strategic approach to integrity, particularly by setting up the Nuevo León Council for Strategic Planning. To strengthen the existing mechanisms and leverage the SEANL’s role in policy design and monitoring, Nuevo León could consider taking the following steps:

Reinforcing the strategy to prevent corruption

-

Substantiate the goals of the State Development Plan related to “Effective and Transparent Government” with a set of objectives that define the implications of a goal in a specific context. These objectives should express one aspect of a goal positively and unambiguously in a single sentence, providing the “who, when, what and where” of a goal.

-

Define the goals, and also the objectives and indicators, of the State Development Plan, not only at the outcome level (indirect results of a strategy or policy) but also at the output level (direct results in the sphere immediately affected by the strategy or policy) and intermediate outcome levels (result from the policy at the first step of corollary inference).

-

Involve members of the Nuevo León Council’s Effective and Transparent Government Commission in the work of the SEANL Executive Secretariat in discussing issues related to strategy and policies, as well as their monitoring and evaluation. This exchange could take place in the consultative sub-commission dealing with prevention issues proposed in Chapter 1 and, when relevant, should also count on the participation of the Executive Agency for the Co-ordination of the State’s Public Administration.

-

Adopt an integrity action plan in the SEANL, identifying the government entities responsible and the timelines for its implementation, and following up on the level of compliance and reporting on the level of implementation, in line with the responsibilities stipulated under the SEANL Law (Article 9 (VI) and (VIII)).

-

Adopt integrity action plans at ministry level, starting with those considered most at risk of corruption, and ensure that they are aligned with the SEANL general action plan. The SEANL governing bodies should provide guidance in drafting the ministry-level action plans. These plans could also be integrated into the entity’s Annual Operational Programmes or Budgetary Programmes.

Operationalising monitoring and evaluation

-

Design a careful operationalisation of all steps of the SEANL’s methodology for monitoring integrity policies, including the definition of goals, objectives and indicators. Base the methodology on reliable and valid data.

-

Test the monitoring methodology on the ongoing training and awareness-raising programme on integrity. This could include co-ordinating studies or surveys to measure the level of awareness of integrity of public officials, to measure any changes over time and to identify challenges.

-

In designing the methodology to monitor integrity policies in the SEANL, establish communication and receive input from those in charge of designing and implementing integrity policies, in particular the various Directorates in the Office of the Comptroller. This exchange could take place in the consultative sub-commission dealing with prevention issues proposed in Chapter 1.

-

Leverage the data collection of the Anti-corruption Unit related to the progress of the Anti-corruption Plan’s (Plan Anticorrupción) in the design of the monitoring system by the SEANL.

-

Consider assigning the Nuevo León Council the role of evaluating the SEANL’s integrity policies, and evaluate SEANL’s integrity policies based on a set of indicators.

-

Evaluate SEANL’s integrity policies based on a set of indicators and elaborate recommendation to the SEANL.

-

Consider and discuss the recommendations of the Nuevo León Council in the SEANL, after evaluation of the integrity policies.

References

[12] Government of Nuevo León (2017), Anti-corruption Plan: Actions and Results (October 2015 - September 2017), http://www.nl.gob.mx/publicaciones/plan-anticorrupcion-acciones-y-resultados-octubre-2015-septiembre-2017.

[10] Government of Nuevo León (2011), Decree establishing Nuevo León anti-corruption plan.

[11] Government of Nuevo León (2011), Guidelines establishing the operational basis of Nuevo León Anti-corruption Plan.

[9] Johnsøn; Hechler; De Sousa; Mathisen (2011), How to monitor and evaluate anti-corruption agencies: Guidelines for agencies, donors, and evaluators, U4, http://www.u4.no/publications/how-to-monitor-and-evaluate-anti-corruption-agencies-guidelines-for-agencies-donors-and-evaluators-2/.

[5] Nuevo León Council (2017), Annual evaluation 2016-2017, http://conl.ukko.mx/documents/document_files/000/000/034/original/Evaluacio%CC%81nAnual2016-2017CONL_con_portada.pdf?1504737664.

[4] Nuevo León Council (2016), State Development Plan 2016-2021, http://www.nl.gob.mx/publicaciones/plan-estatal-de-desarrollo-2016-2021.

[3] Nuevo León Council (2016), Strategic Plan of Nuevo León 2015-2030, http://www.nl.gob.mx/publicaciones/plan-estrategico-para-el-estado-de-nuevo-leon-2015-2030.

[13] OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

[1] OECD (2017), Monitoring and Evaluating Integrity Policies.

[7] OECD (2017), OECD Integrity Review of Colombia: Investing in Integrity for Peace and Prosperity, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278325-en.

[6] OECD (2017), OECD Integrity Review of Mexico: Taking a Stronger Stance Against Corruption, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273207-en.

[2] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf.

[15] OECD (2010), Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results Based Management, http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/2754804.pdf.

[16] OECD/DAC (1991), Principles for the Evaluation of Development Assistance, http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/2755284.pdf.

[8] U.S. Office of Government Ethics (n.d.), Ethics Program Reviews, https://www.oge.gov/web/oge.nsf/Program%20Review (accessed on 20 October 2017).

[14] Zall Kusek, J. and R. Rist (2004), Ten Steps to a Results-Based Monitoring and Evaluation System, The World Bank, https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-5823-5.