Chapter 11. Fisheries

This chapter presents the main characteristics and trends of the Peruvian fisheries sector, including fish farming and freshwater fishing in Amazonia, as well as the institutional framework for fisheries policies. Despite the progress made in the management of some fisheries resources, such as anchovy, the creation of marine protected areas, and the environmental regulation of the fish industries, environmental performance suffers from a lack of information on endangered aquatic species and the presence of an informal economy. The chapter calls for a strategy for integrated management of the marine-coastal ecosystem.

Key findings and recommendations

Fishing and aquaculture activities in Peru are characterised as much by their natural variability (from maritime to Amazonian fisheries) as by their economic diversity (from industrialised to subsistence fishing). The Pacific Ocean along the Peruvian coast is one of the world’s most productive seas. These conditions have favoured the establishment of an industrial-scale maritime fishery, focused primarily on pelagic species —anchovies account for 86% of the catch, although mackerel, horse mackerel and squid are also fished. Peru is the world’s leading producer of fishmeal and fish oil, although production is affected by the great environmental variability, as the anchovy biomass fluctuates sharply with water temperature, which varies dramatically at times of El Niño and La Niña. Output fell from 6 million tonnes in 2006 to 3.5 million tonnes in 2010, although this was offset by higher prices for fishmeal (USD 810 per tonne in 2007 versus USD 1 360 in 2013). Aquaculture is now developing as an economic activity, focused on scallops and prawns along the coast and on trout, tilapia, gamitana or black pacu, and paiche or arapaima in inland waters. A new Aquaculture Act was recently adopted to promote this sector, given its importance in terms of food security.

The artisanal maritime fishery involves multiple species and low-tech methods, and is destined primarily for direct human consumption. There are landing and storage facilities all along the coast, but control and monitoring is less extensive. The most important inland fishery is in Amazonia. It is typically artisanal, and mainly for subsistence consumption. Much of the human diet in Amazonia relies on fish, and although the catch amounts to more than 80 000 tonnes, supply falls short of demand, with aquaculture now seeking to fill that gap. There is a Regulation on Fisheries Management in Amazonia, which is now under review.

Despite better inter-agency co-ordination on marine issues, fisheries policy still has a sectoral rather than an ecosystemic approach. Responsibilities for the ocean are divided among many agencies (Ministry of Production, regional governments, Ministry of the Environment, OEFA, SERNANP, SENACE, DICAPI, National Water Authority, SANIPES), and they have little representation in the only existing co-ordinating body (COMUMA, the Multisectoral Commission for Coastal-Marine Environmental Management). There is no comprehensive plan for the anchovy fishery that would establish a single science-based quota, nor is there any arrangement for joint stock management with Chile, which shares the fishery. Most of the remaining fish species have no catch quotas or maximum limits. The protection of marine and inland aquatic species is clearly inadequate: there are no lists of threatened species, no conservation plans, no specific measures to minimise illegal fishing or by-catch, and no control over environmentally harmful fishing methods. Some enclosed bays are being polluted by industrial activity, domestic effluents, and so forth. Studies conducted in Amazonia show alarming concentrations of heavy metals in fishery products for human consumption. One problem with relation to inland fisheries has to do with ornamental species, for which there are no data on stocks nor any effective supervision of catches. Peru’s protected marine areas cover a total of 401 556 hectares, representing 2% of its total marine surface. These areas belong to the San Fernando, the Paracas and the Islands, Islets and Guano Capes National Reserves which, while very well managed, are insufficient to ensure protection of all of Peru’s marine ecosystems. Nevertheless, the main challenge in the fishing sector is its informal nature, especially in artisanal fishing and aquaculture. Despite the efforts made, a significant portion of the marine and inland fisheries and aquaculture activities are pursued without supervision, owing to the shortage of human resources, the size of the territory and the inaccessibility of some areas.

Responsibility for scientific research and studies on the fisheries and their relationship with aquatic ecosystems lies with the Peruvian Sea Institute (IMARPE) and the Peruvian Amazon Research Institute (IIAP), as well as with the fisheries and aquaculture faculties of various universities. The Peruvian Sea Institute is the agency charged with recommending catch quotas for fish species, monitoring landings, by-catch and fish age criteria, assessing sea species and conducting carrying capacity studies in watercourses used for aquaculture. It is also responsible for reviewing Environmental Quality Standards for sediments, for regulatory approval.

The body of legislation governing the maritime fishery may be considered obsolete: the General Fisheries Act, No. 25977, dates from 1992 and its regulations (Supreme Decree 012-2001-PE) date from 2001. However, systems have been established concerning minimum size, fishing season limits and quotas, among other details, and these have contributed to progress towards the sustainability of the industrial fishery. A good example is the amendment to the anchovy quota, which was changed from an aggregate quantity (which ship owners promptly used up in the course of what was known as the “Olympic race”) to a system based on catch quotas per vessel, established in light of the fleet’s historic catch (Legislative Decree No. 1084 of 2008, Maximum Catch Limits per Vessel Act). This has had a positive impact on efficiency in the sector, reducing the size of the fleet and the number of processing facilities while maintaining output capacity. The measure has also had positive repercussions for stocks. The main responsibility for co-ordination, regulation and supervision of the fisheries sector lies with the Ministry of Production (PRODUCE), although there has recently been some decentralisation in supervision of the artisanal fishery toward the regional governments. It is the Ministry of Production that formulates fisheries policy and approves standards for the sector. It also performs oversight of the commercial fishing fleet, directly with its own 260 inspectors and indirectly by co-ordinating the work of the 700 inspectors belonging to certification firms and paid by the industry itself.

In the fisheries area, the Ministry of the Environment (MINAM) is responsible for establishing policy and specific regulations, for inspection and supervision, and for imposing penalties for breach of environmental rules. In 2012, OEFA (a specialised technical agency of the Ministry) took over environmental inspection of the fisheries sector. In the case of aquaculture and fishing in protected coastal and marine areas and inland waters, responsibility lies with SERNANP. In 2012, the Multisectoral Commission for Coastal-Marine Environmental Management (COMUMA) was established to co-ordinate the various administrative and technical agencies involved in protection of the sea. This Commission could become a very effective tool for designing a co-ordinated, coherent and integrated policy on the protection and sustainable management of the marine environment. The Strategic Plan for Management and Handling of the Coastal Marine Ecosystem and its Resources is currently in the public consultation process. It is an intersectoral policy guide and contains strategic objectives, targets and a short-, medium- and long-term implementation schedule.

Recent years have seen notable efforts in some areas to reduce the local environmental impact of processing plants by regulating emissions and discharges into the sea, for example in the bays of Chimbote, Samanco and Paracas. Generally speaking, the industrial fishery for indirect human consumption is quite well regulated and supervised. Since approval of Supreme Decree 026-2003-PRODUCE, Regulations of the Satellite Monitoring System (SISESAT), the industrial fishery has been subject to remote tracking. Monitoring of fish landings has also been stepped up.

Recommendations

-

Make progress towards an integrated policy for hydrobiological resources with comprehensive and coherent planning of the usage made of the ocean and inland water basins. This should take into account the conditions of ecosystems, combine the objectives of the different policies, establish clear guidelines based on the ecosystemic approach, provide for concrete actions and be equipped with mechanisms for monitoring compliance and the environmental, social and economic effects of the implementation of those actions. Raise the institutional and political level of the interadministrative co-ordination agencies, such as the Multisectoral Commission for Coastal-Marine Environmental Management (COMUMA), in order to make the planning process more effective. Where necessary, adopt specific instruments for places with identified problems, to facilitate the coherent management of marine areas and related inland water basins.

-

Capitalise on the available scientific knowledge and strengthen the institutions responsible for providing information, such as IMARPE and IIAP, so they can provide suitable, independent and impartial advice for decision-making and policy design. Ensure transparency in fishery figures, including catches and landings, by-catches, discards, inspections, and so on. Assess the harmful environmental effects of aquaculture, such as escaping exotic species and excessive use of nutrients and pesticides, and of industrial processes to prepare feedstocks; as well as the pressures on fish populations. Promote the education and training of managers, inspectors and the productive sector.

-

Encourage the work of the National Fish Health Service (SANIPES) in controlling pollutant levels in fishery and aquaculture products, as a preventive health measure and as a source of information for monitoring pollution in bodies of water. Make progress in the understanding and management of sources of pollution that affect aquatic ecosystems.

-

Redouble surveillance and inspection efforts to eradicate illegal fishing and to formalise informal fishery activities. Design specific measures to discourage informal fishery activities and to bring all fishery workers into regulated management schemes. Promote fishery agreements with local communities and with small-scale fishing concerns within the total allowable catch (TAC), as applicable. Strengthen local capacities for joint management, in order to facilitate the sustainable extraction and management of hydrobiological resources from both the sea and inland waters.

-

Further develop the catch quota system and analyse the effects of extraction on ecosystems, encompassing the entire sector (indirect human consumption, direct or small-scale human consumption) and allowing for the possibility of quota transfers between stakeholders and of extending the quota system to other at-risk commercial species, both maritime and inland, on the basis of the best knowledge available and keeping in mind climate change. Draw up lists of endangered and at-risk species and establish the closed seasons necessary for their survival, particularly in the Amazon. Develop specific extraction plans for ornamental species.

1. Sector description

1.1. General background

The Pacific Ocean, which washes the Peruvian coast, is one of the world’s most productive owing to its deep, cold waters with abundant nutrients from the effects of the Humboldt Current. This favourable ecology has led to the emergence of a dynamic marine fishery industry that is equipped with modern infrastructure and that focuses mainly on exports of fishmeal and fish oil obtained from anchovies and, to a lesser extent, on processing for direct human consumption.

The aquaculture industry is a recent development in the country that has enabled the use of a variety of resources —both maritime (scallops and prawns) and inland (paiche and trout)— for both the export and domestic markets (including subsistence consumption).

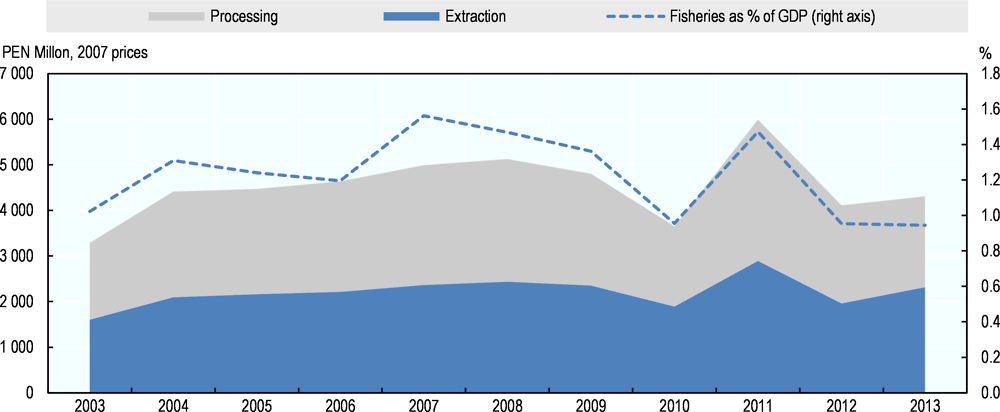

The fisheries sector, including both extraction and processing, accounted for around 0.9% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013 (Ministry of Production, 2015). Its real-term output remained relatively stable over the period under review, in spite of an initial increase and, subsequently, a degree of variability. Its share in total economic activity has followed a similar pattern, albeit with a recent downward trend. In 2007, fisheries accounted for a record level of 1.7% of GDP (Figure 11.1).

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of Ministry of Production (2015; 2013a).

The sector’s exports totalled USD 2.8 billion in 2013. Products for indirect human consumption, primarily fishmeal and fish oil, accounted for 61%. Export earnings from both products grew between 2003 and 2012 owing to a rise in international prices. Similarly, exports of products for direct human consumption —canned, frozen and cured— expanded significantly, with a 5.5-fold increase in earnings.

Employment in the sector stood at around 160 000 workers in 2013, or about 1% of the country’s workforce. This figure is broken down as follows: extraction, 59%; processing, 16%; aquaculture, 9%; and other related activities, 17%. Employment grew by 29% between 2003 and 2013, in line with the evolution of the sector’s output.

1.2. The use made of hydrobiological resources

The extractive sector covers maritime fisheries, inland fisheries and aquaculture. Maritime fishing involves both industrial and artisanal activities. Inland fishing (which includes ornamental species) is mainly artisanal. Aquaculture involves industrial and artisanal operations, and is pursued in both maritime and inland waters.

Maritime fishery

Maritime fishing, predominantly of Peruvian anchovies (hereafter anchovies), takes place in two main fishery areas with distinct stocks: (i) the centre-north zone, and (ii) the southern zone. In the former, which extends down to latitude 16º south, industrial fishing takes place at a minimum of 10 miles from the coast, while smaller-scale operations are concentrated at a range of between 5 and 10 miles and artisanal fishing takes place within the first 5 miles. In the southern zone, the corresponding limits are 5 miles for large-scale fishing and 3.5 miles for medium-scale operations, with artisanal fishing taking place in the area closer to land. Here, artisanal fishing is authorised to operate in the other two areas, and medium-scale operations are allowed in the large-scale area (Heck, 2015).

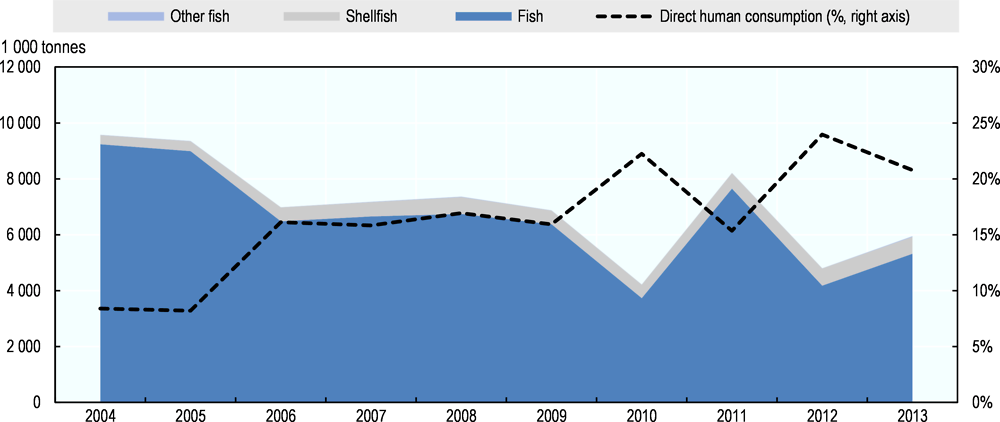

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of Ministry of Production (2015; 2013a).

Total fishery landings decreased over the period studied, chiefly on account of changes in fish catches. Extractions of shellfish and other species increased by factors of 2.7 and 2.4, respectively (Figure 11.2).

Most of the extracted resources are used to produce fishmeal and fish oil (indirect human consumption), a sector where Peru is the world’s leading producer. In 2005, 92% of the total catch was used for fishmeal and fish oil and, in 2014, the share was 63%. That change was largely due to falling anchovy catches (Ministry of Production, 2013a and 2015).

Anchovy landing numbers are influenced by the pronounced environmental variations. The anchovy biomass fluctuates sharply with water temperature, which varies dramatically at times of El Niño and La Niña. In recent years, the anchovy catch has fallen (from some 6 million tonnes in 2006 to 4.9 million in 2013), which has been offset by rising fishmeal prices.

Landings used for direct human consumption (canned, frozen, cured and fresh products) accounted for 37% of the total in 2014 (compared to 12% in 2003). The evolution of this subsector has been interesting, with average annual growth rates of 5.3% (for a total of 77% over the period under review) as a result of policies for its development (Ministry of Production, 2013a and 2015).

Artisanal maritime fishery

Artisanal maritime fishing is a low-tech activity that almost exclusively serves direct human consumption. Official checks and monitoring of this sector are less exhaustive. The first National Census of Artisanal Maritime Fisheries (CENPAR I) revealed the existence of 116 landing sites along the coast (INEI, 2012). At the same time, according to information from the National Fisheries Development Fund (FONDEPES), in 2011 there were 45 artisanal landing facilities, of which 89% were operational. Although 31 landing sites have ice plants, only 10 of them are operational.

Recent years have seen significant increases in the numbers of both fishers and vessels dedicated to this activity. This growth can be attributed to low-resource populations migrating to coastal areas. Significantly, the recent expansion of the productive fleet occurred at a time when regulations prohibiting the construction of new fishing vessels were in force (Supreme Decree No. 020-2006-PRODUCE and Supreme Decree No. 018-2010-PRODUCE) (Table 11.1).

Inland fishing

The most important inland fishery is in Amazonia. Typically artisanal, it is a major source of both revenue and foodstuffs. Subsistence consumption accounts for a significant proportion of its activities. Nevertheless, declining fish stocks have been observed in the region, the result of climate conditions and inadequate fishery management. In 2005, Amazonia produced 36 600 tonnes (FAO, 2010), which fell to 25 300 tonnes in 2013 (Ministry of Production, 2013c). Much of the food supply of the inhabitants of Amazonia comes from fishing, with 70 species that are commercially exploited for human consumption. Another 420 species are used for ornamental purposes. The Regulation on Fisheries Management in Amazonia (Supreme Decree No. 0015-009) is currently in force and undergoing review.

Aquaculture

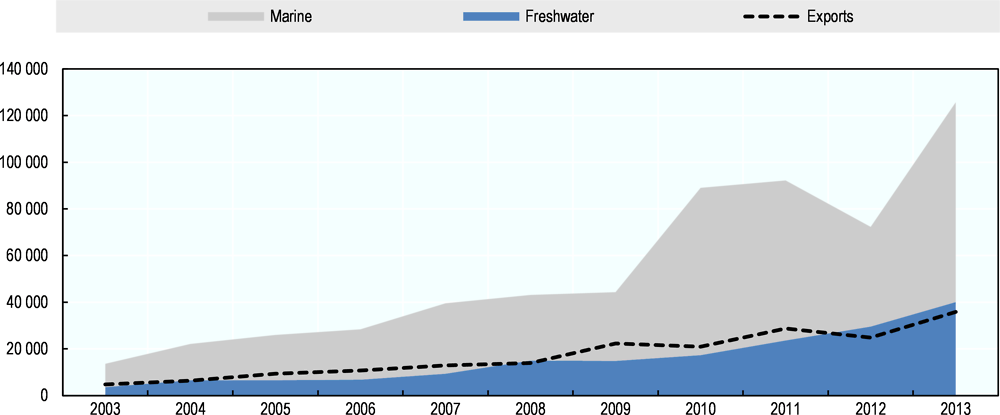

Aquaculture has expanded significantly in recent years (Figure 11.3). Aquaculture harvests represented 2.1% of total maritime and inland fishing in 2013, with average annual growth rates of 25%, yielding an accumulated growth of 820% over the period studied. Scallops and prawns account for almost 100% of the maritime aquaculture harvest. In contrast, inland aquaculture makes up a third of the total and is focused on trout and tilapia, which accounted for 97% of the 2013 harvest, alongside other species such as gamitana (Colossoma macropomum), paco (Piractus Brachypomus) and paiche (Arapaima gigas) (Ministry of Production, 2013a and 2015).

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of Ministry of Production, Anuario Estadístico Pesquero y Acuícola 2014, Lima, 2015; and Anuario Estadístico Pesquero y Acuícola 2012, Lima, 2013.

Aquaculture products are sold on both local and overseas markets. Exports grew significantly between 2003 and 2013, rising from 4 700 tonnes to almost 36 000 tonnes. At the same time, the sector’s earnings rose from USD 25 million to USD 300 million.

1.3. Processing industry

The processing sector covers the production of fishmeal and fish oil and the canning, freezing and curing industries. Of the total 2013 catch, 93% was processed and only 7% sold as fresh products (Ministry of Production, 2013c). The output of fishmeal and fish oil, which are used in animal feed and other foodstuffs, has evolved along similar lines as landings of anchovy (a species used almost exclusively for indirect human consumption). Most of these products are exported. International prices for fishmeal have evolved very favourably over the period, almost trebling between 2003 and 2014, when they approached USD 2 000 per tonne (Table 11.2).

Processing plants for fishmeal and fish oil are mainly found along bays. There are 74 facilities for fishmeal production, with an installed capacity of 6 635 tonnes per hour. Four regions account for 75% of the installed capacity: Ancash with 27%, Lima with 19%, Ica with 15% and La Libertad with 14% (Ministry of Production, 2013c).

The remainder of the processing sector produces canned, frozen or cured products. Of these, frozen goods account for the largest share: 77% of the total in 2013 (compared to 47% in 2003).

2. Pressures and main environmental problems of the sector

Fishery activities depend on the health of the habitats where they take place. They are vulnerable to impacts from other activities and, at the same time, can bring about various types of pressure on the environment.

In many cases, the environmental information available is incomplete and the effects can only be inferred. Most of the information available on stocks is limited to the main commercial marine species (e.g., anchovy, squid, horse mackerel, mackerel and hake). That is in line with the fact that the use of those species is more specifically regulated by Fishing Management Regulations (ROPs). There is no information on the state of stocks of non-commercial species and those found in inland waters. The protection of marine and inland aquatic species is clearly inadequate: there are no lists of threatened species, no conservation plans and no specific measures to minimise illegal fishing or by-catches. Given the absence of such information, actions and negative incentives that undermine the sector’s sustainable development cannot be identified.

Anchovy is Peru’s main hydrobiological resource and the one on which the largest amount of information is available. It is subject to a system of per-vessel catch quotas and closed seasons, which have helped the recovery of the species’ biomass. However, additional work is needed to develop a comprehensive plan that sets a single quota, based on scientific observations and supported by an analysis of the effects that extraction for direct or indirect human consumption and artisanal fishing have on ecosystems. Neither is there any joint stock management with Chile, even though the anchovy resource is shared with that country and the two nations conduct joint scientific studies.

Hake, another resource managed by means of individual per-vessel quotas, has reported an uptick in landing volumes in recent years. The authorised fleet was reduced early in the first decade of the century in order to assist the recovery of the resource following the closure of the fishery. It currently comprises 43 vessels.

Mackerel and horse mackerel are straddling and migratory species. They are caught in both territorial waters and on the high seas, thus Peru is not solely responsible for the health of their populations. An overall catch quota is in place, and productivity depends on the environmental variations caused by El Niño and La Niña. As is the case with other species in Peru, squid fishing is a recent development and landings have increased significantly. It is estimated that the squid biomass is abundant, for which reason the Peruvian Sea Institute (IMARPE) has classified it as underexploited at the national level.

Informal activities are a major problem in the fisheries sector, chiefly in the areas of artisanal fishing and aquaculture. A significant proportion of fishing is not subject to controls in spite of the efforts made to manage the activity and its landings. This is primarily due to the shortage of personnel to cover the country’s vast territory and the inaccessibility of certain regions.

In the north of the country, in the Tumbes and Piura districts, artisanal and small-scale fishers practice purse-seine fishing and trawling within five miles of the coastline. Despite being banned since 2005, these techniques are still practised. In 2013, the Ministry of Production amended the Tumbes Regulation on Fisheries Management (Supreme Decree No. 006-2013-PRODUCE) to require small-scale vessels engaged in purse-seine fishing and trawling to obtain a permit from the IMARPE and install a satellite tracking system to operate beyond the five-mile limit.

This action is intended to place these fishery workers under a specific legal regime, as a way to reduce the informality with which they operate and, in many cases, seem unwilling to change (Ministry of Production, 2013b). Purse-seine fishing in shallow waters and trawling have a major impact on marine ecosystems. However, there are no records of specific studies into the matter in these regions. The artisanal fishing sector feels that the government’s actions have left it powerless, largely because informal or illegal activities remain unchecked.

Fishing in Amazonia has decreased notably in recent years because of drought. As a result, fishing activities concentrate in certain areas at times of scarcity, which causes levels of overexploitation from which some species do not recover. Poor management and interference with habitats also bear some responsibility in this. Fishery catches in Amazonia are only recorded at major landing sites, and so their true dimensions and impact are not fully understood.

Another key problem with the exploitation of inland fisheries has to do with ornamental species. Although the National Commission on Biological Diversity (CONADIB) has a technical group responsible for inland waters, led by PRODUCE, there is no information available about stock health and no effective control over catches.

Two species —silverside (Odontesthes bonariensis) and trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) — were introduced into the inland waters of the high Andes in 1955 and 1939, respectively. They have become commercially important, and have consequently an impact on some native aquatic species (invertebrates, frogs and amphibians). The affected areas are the Río Abiseo National Park in San Martín, Lake Titicaca and the Mala and Cañete Rivers in Lima. Those introduced species reportedly brought parasites with them, and it is unknown whether any control measures have been adopted.

Also in the inland region, where the production of freshwater prawn is concentrated, there have been alarming falls in stocks on account of various pressures, including water pollution, water extraction for agricultural purposes and overexploitation. As a result, closed seasons have been imposed on the resource.

In some closed bays, one of the severest problems is water pollution caused by industrial activities. In particular, fishery processing plants emit large volumes of liquid residue into the sea, which is also contaminated with domestic effluents and by dockside refuelling activities. The bays at Callao and El Ferrol report high levels of total and faecal coliforms that, in many cases, exceed the maximums permitted for recreational activities and commercial fishing. At the Bay of Paita, the main sources of pollutants are domestic effluents and the processing industry. El Ferrol Bay is considered a critical zone because of marine pollution from domestic and industrial effluents and discharge from a steelworks.

In recent years, major efforts have been made in some areas to reduce the local environmental impact of factories. In 2008, maximum permissible limits (MPLs) were set for the fishmeal and fish oil industries (Supreme Decree No. 010-2008-PRODUCE). These allowed for the regulation of releases into the sea and emissions, including the installation of underwater outlets. This has been in the bays of Chimbote, Samanco and Paracas. The processing industry, which produces foodstuffs intended for direct human consumption, is not subject to MPLs.

In inland waters, too, habitats have been damaged by pollution. In those cases, the main causes are mining, including extractive wastes, and wastewater. Gold mining —chiefly artisanal gold mining pursued illegally or informally— is responsible for major mercury contamination in the Madre de Dios district of Amazonia. Studies carried out by the Carnegie Amazon Mercury Ecosystem Project (CAMEP) revealed that at markets in the city of Puerto Maldonado, 9 of every 15 fish species intended for human consumption exceeded the established limits for mercury content. Those levels rose between 2009 and 2012 in 90% of the species examined, which reflects the bioaccumulative impact of the pollutant and the expansion of illegal extractive activities in the area. In this locality, 78% of the adult population was detected to have an average of 2.7 ppm of mercury, almost three times higher than the maximum recommended concentration (1.0 ppm). Women of childbearing age are the worst affected segment of the population, on account of the risk of intrauterine transmission of the contaminant (CAMEP, 2013).

Aquaculture offers a good alternative for maintaining a stable supply of protein and contributing to food security. The effects of the newly enacted Aquaculture Act will have to be assessed, but at present there are still shortcomings in how aquaculture activities are managed. For example, no studies have been conducted into the carrying capacity for aquaculture of bodies of water (Samanco, Sechura, Puno), which is necessary to ensure the protection of the ecosystems where the facilities are installed.

Protected maritime areas account for a minor fraction of Peru’s territorial waters (see the chapter on the context and trends). These areas include the National Reserves of San Fernando, Paracas and the System of Islands, Islets and Guano Capes which, while very well managed, are insufficient to ensure protection for all Peru’s marine ecosystems. There is a proposal for a Tropical Pacific Ocean Reserve, in the Máncora Bank and the Cabo Blanco submarine canyons, which make up the habitat of 35% of Peru’s maritime species. This proposal has been placed on hold because of the opposition of the hydrocarbons industry operating in the area, which underscores the need to balance the protection of ecosystems with productive endeavours, so that industry can continue to operate in a way that is compatible with the demarcation and management of protected areas.

The upwelling system of the Humboldt Current in Peru is a marine area of ecological and biological importance on account of its high levels of endemism and the rising of nutrient-rich waters, which make it one of the world’s most productive marine regions (CBD, 2015). In keeping with the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, Peru should move ahead with the conservation of its marine and coastal areas, particularly given the presence in its territory of a marine ecosystem of ecological and biological importance.

3. Institutional organisation

3.1. Institutional framework of the sector

Chief responsibility for the co-ordination, regulation and supervision of the fisheries sector lies with the Ministry of Production (PRODUCE), through the Vice-Ministry for Fisheries. PRODUCE is responsible for framing fisheries policy and adopting regulations for the sector, as well as for inspecting the industrial fleet, which involves assigning inspectors on board vessels. Recently, there has been a movement toward decentralising oversight authority for artisanal fishing to the regional governments.

In the anchovy sector, the Vice-Ministry for Fisheries is responsible for: (i) devising management rules, policies and regulations, (ii) implementing oversight and control programmes and imposing sanctions for failures to abide by the management rules, and (iii) establishing and granting fishing rights. Different legal regimes apply to anchovy vessels depending on their storage capacity and the use made of their catches. The current legal framework provides that anchovies caught by artisanal and smaller-scale vessels can only be used for direct human consumption, while industrial fleet catches must be used exclusively for indirect human consumption (fishmeal and fish oil). However, failures to abide by those rules are frequent.

The Ministry of Production is supported by a number of institutions: (i) the National Fisheries Development Fund (FONDEPES), which is charged with promoting the development of fisheries and artisanal aquaculture through such methods as providing basic infrastructure, access to credit and training, (ii) the Technological Institute of Production (ITP), which promotes research, adaptation strategies and technological transfers for the use of fishery resources, together with sanitary and quality controls, and (iii) the Peruvian Sea Institute (IMARPE), which studies the marine environment and its biodiversity, including anchovy population levels, to inform decision-making on fishery matters. In addition, IMARPE conducts scientific and technical monitoring of fishery activities, landings, by-catches and age criteria, and it works on the study and evaluation of marine species (hammerhead shark, octopus, Chilean abalone, silverside, mullet, lorna, cabinza grunt, among others) and on studies into the carrying capacity of bodies of water for aquaculture (e.g. Sechura).

Scientific monitoring and studies of fisheries and their relationship with aquatic ecosystems are conducted by both the Peruvian Sea Institute (IMARPE) and the Peruvian Amazon Research Institute (IIAP), as well as by the fisheries and aquaculture schools of various universities.

IMARPE conducts studies into habitats, modelling and trophic ecology, and the potential use of macroalgae and new species. It is also revising the Environmental Quality Standards for sediments, with the aim of obtaining regulatory approval. It has a programmeof on-vessel observers to control minimum sizes, take trophic samples and collect information on mammals, birds and discards, which enables it to draw up recommendations for the Ministry of Production.

IMARPE also trains fishery inspectors and provides environmental training for fishers and ship owners. It has also developed a project that deploys observers on the artisanal fleet, expanding the information available on catches and fishing activities in around 50 landing sites along the Peruvian coast, as part of the “Strengthening artisanal fishing” budgetary programme.

Through the Marine-Coastal Functional Research Area (AFIMC), IMARPE carries out impact assessments for different activities in the coastal region and some inland water bodies. It analyses water and sediment quality in coastal land that is used for economic activities, such as artisanal fishing and aquaculture, as well as for use in urban and rural areas, industrial zones and other activities.

For inland fishing, the work of IMARPE involves such tasks as demarcating freshwater prawn river beds, estimating landings and conducting water quality studies. IIAP has taken charge of research efforts in inland waters, and has taken on the tasks of conducting genetic studies of flagship species, monitoring landings, undertaking repopulation work and drafting regulatory proposals for off seasons and minimum extraction sizes. In the field of aquaculture, IIAP has begun the cultivation and distribution of larvae.

3.2. Legal framework and instruments

Although the General Fisheries Act, No. 25977, dates from 1992 and its regulations (Supreme Decree 012-2001-PE) from 2001, amendments have been made over the years that have advanced the sector’s sustainability. The main changes include the adoption of Supreme Decree No. 026-2003-PRODUCE, Regulation of the Satellite Monitoring System (SISESAT), which implemented the remote tracking of industrial fisheries.

Another significant improvement was a change in the anchovy quota system. Traditionally, the general catch quota for anchovy intended for indirect human consumption was a single amount. According to that plan, there were no individual allocations and ship owners competed in what was called the “Olympic race”, and, as a result, the entire season’s quota was reached in just a few days. In 2008, the Maximum Catch Limits per Vessel Act (Legislative Decree No. 1084) divided the catch quota by vessels, in line with historical rights. Under this scheme, fishing can take place at staggered times over each season, with proper human and material resource planning. This has had a positive impact on the sector’s efficiency, in that it has led to reductions in the fleet and in the number of processing plants while maintaining the same levels of output. The measure has also had positive repercussions for anchovy stocks.

Supreme Decree No. 008-2012-PRODUCE imposed conservation measures on anchovy fishing. Under this decree, the Ministry of Production was given powers to limit access to resources and activities, procedures were established for ordering closed seasons and rationalising fishery activities and measures were established for the conservation of juvenile specimens and preventing discards. It also ordered the deployment of onboard inspectors and mechanisms to visually record vessels’ activities to ensure compliance with those measures. Supreme Decree No. 005-2012-PRODUCE clearly demarcates the anchovy fishing grounds for the different fleets (artisanal, medium-scale and large-scale) and it increased the restrictions and requirements for the artisanal fleet which, in some cases, are now the same as those that apply to the industrial fleet.

In addition to the current legislation, Fishing Management Regulations (ROPs) are in force in certain specific areas with resource exploitation problems or under greater pressure, as well as with respect to fishery resources of particular interest. Thus, there are ROPs for anchovy, hake, mackerel and horse mackerel, tuna, eel, squid, macroalgae and the fishery products of Amazonia, Tumbes and Lake Titicaca.

The species-specific Regulations establish the requirements that must be met in order to exploit those resources (including fees), as well as put in place protective measures such as global quotas, fishing seasons and areas, closed seasons, the protection of juveniles, fishing tackle, vessel characteristics and the requirements for surveillance mechanisms. Per-vessel quotas are enforced for species such as anchovy and hake.

The Regulations for specific areas are intended to enhance capacities to manage the resources they contain. They aim to improve scientific knowledge and research, to strengthen the institutions involved, to help formalise fishing activities and the use of sustainable practices and, specifically, to impose restrictions to address specific problems in each area. While compliance with these rules has not been assessed, the available information suggests that, based on the capacity for management and oversight, there is a high rate of non-compliance.

Most of the remaining species of fish are not subject to quotas or maximum catch limits, and so further progress is still needed on the regulation of the fisheries sector. Knowledge about commercial species and their relationship with marine and inland ecosystems and about the impacts of fishery activities is still limited. This hinders the adequate planning of hydrobiological resource extraction.

The first sectoral law for aquaculture —the Aquaculture Promotion and Development Act (Law No. 27460-2001) and its Regulations (Supreme Decree No. 30-2001-PE)— was enacted in 2001 and defines the priority nature of the activity. This law instructs the Ministry of Production’s General Aquaculture Directorate to draw up a national aquaculture development plan. Recently, by means of Legislative Decree No. 1195, the General Aquaculture Act was enacted. Its goals include promoting the development of aquaculture as a nationally important economic activity and furthering productive diversification, competitiveness and food security, in harmony with environmental protection, together with the conservation of biodiversity and the health and safety of hydrobiological resources and products. The Act plays an important role in generating quality products for consumption and industry, in addition to the creation of social goods such as jobs, revenues and productive chains.

Recently, efforts to promote aquaculture have been under way in order to increase the amounts of fishery products used for direct human consumption. One example of this is Supreme Decree No. 010-2010-PRODUCE, Regulations on Fisheries Management for Resources of Peruvian anchovy (Engraulis ringens) and Longnose Anchovy (Anchoa nasus) for Direct Human Consumption, which declares it to be an activity of national interest. In addition, a regulation was recently adopted whereby direct human consumption will be allocated a share of the general anchovy catch quota.

At the same time, and as described in the chapter on co-operation and international commitments, Peru has a series of agreements and plans that it has implemented —or is implementing— to protect, conserve and manage its resources. Most notable are following: (i) the FAO Port State Measures Agreement, (ii) the enforcement in Peru of the Permanent Commission of the South Pacific’s Regional Plan of Action for the Conservation of Sharks, and (iii) participation as an acceding State in the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

3.3. Co-ordination

The Multisectoral Commission for Coastal-Marine Environmental Management (COMUMA) was established in 2012 to co-ordinate the various administrative and technical agencies involved in protecting the sea. The aim was to establish an effective tool for designing an integrated, coherent and co-ordinated policy for the protection and sustainable use of the marine environment. The Commission could involve more agencies with competences in this area and increase the production of sectoral planning instruments.

COMUMA currently has seven specialised technical working groups (GTTEs) on: artificial reefs, integrated management of the maritime coastal zone, implementation of the beaching network, management of benthic resources, strategic plan, ocean health and breakwaters. The creation of a technical group for legally protected species has also been proposed.

There has generally been some distance between the sectoral authorities’ vision and that of the actors who are concerned with the environmental impact. Although progress with institutional co-ordination on maritime matters has been made in recent years, fisheries policy is still defined with a sectoral approach and not with an ecosystemic perspective. This is further heightened by the proliferation of agencies with maritime responsibilities —the Ministry of Production (PRODUCE), the regional governments, the Ministry of the Environment (MINAM), the Environmental Assessment and Enforcement Agency (OEFA), the National Service for Government-Protected Natural Areas (SERNANP), the National Service of Environmental Certification for Sustainable Investments (SENACE), the General Directorate of Harbour Masters and Coastguards (DICAPI), the National Water Authority (ANA) and the National Fish Health Service (SANIPES)— and the low level of representation those agencies have in the only co-ordinating body that exists, the Multisectoral Commission for Coastal-Marine Environmental Management (COMUMA).

Each of these institutions draws up its own policies in accordance with its multi-year strategic plans. There is no general planning that takes into account the full range of objectives (economic, social and environmental) related to the use of the sea. In addition, policymaking does not appear to take into account the potential cumulative effect of individual and collective environmental impacts. In inland waters, the problem is the same: there are no strategic plans or co-ordination agencies with the institutional legitimacy to set forth an integrated policy for hydrobiological resources that takes account of both their exploitation and environmental and social values.

The relevant COMUNA working group is preparing a Strategic Plan for Management and Handling of the Coastal Marine Ecosystem and its Resources, which is currently at the public consultation phase. It represents an intersectoral policy guide, and it contains strategic objectives, targets and a short-, medium- and long-term implementation schedule. It is connected with the Guidelines for the Integrated Management of Marine and Coastal Areas and with the classification study of marine and coastal bodies of water carried out by ANA. The document includes principles for ecosystemic management, participatory governance and other mechanisms, and it could offer a basis for progress towards the effective co-ordination of marine protection in Peru.

3.4. Oversight

Oversight of the different aspects of the fishery sector’s activities is carried out by a number of institutions. The Ministry of Production’s General Directorate of Follow-up, Control and Oversight (DIGSECOVI) and the regional governments’ Regional Production Directorates (DIREPROs) are responsible for control and oversight of compliance with the provisions of the current legal regime for fisheries, as applicable. The Ministry of the Environment is charged with overseeing environmental conservation in such a way as to encourage and ensure the sustainable, responsible, rational and ethical use of natural resources and of their supporting environments. In the fisheries area, its activities include setting policy and establishing specific regulations, oversight and control, and the power to impose sanctions for failures to abide by environmental rules.

In 2012, the Ministry of the Environment’s Environmental Assessment and Enforcement Agency (OEFA) was made responsible for the environmental oversight of the fisheries subsector. The competences transferred to OEFA, exclusively for industrial processing plants and large-scale aquaculture facilities, were environmental supervision, oversight, control and sanction.

According to information from the Ministry of Production, the number of sanctions imposed was on the rise until 2010, after which it started to decrease. The sanctions that attract the steepest fines involve the extraction of resources from reserved areas or in amounts greater than the storage capacity, or fishing without the necessary permits. There is no information on how oversight activities have changed, on the new control and supervision powers or on the transfer of powers to OEFA. This last issue could be responsible for the falling number of sanctions in the latter part of the period in question. It is also unknown how many sanctions were actually enforced (Table 11.3).

In general, oversight of industrial fisheries for indirect human consumption has been adequate since the introduction of the satellite monitoring system. The monitoring of landings has also increased. The Ministry of Production has 260 inspectors of its own and co-ordinates 700 indirect inspectors from certification companies that are paid for by the industry itself.

As a result of the decentralisation process, regional governments have been given responsibility for managing artisanal fishing and for overseeing compliance with national rules within the first five nautical miles of the coast. However, they need to develop their technical and organisational capacity for discharging these functions. The artisanal sector is key for effective resource management and the protection of marine ecosystems. Without its direct involvement, commitment, acceptance of the rules and participation in overseeing compliance, properly managing hydrobiological resources will be impossible.

The level of informality and the rate of non-compliance with the current legal provisions (on such matters as closed seasons and minimum sizes) have not been measured. The sanctions system appears of be of limited effectiveness. Offenders continue their activities in the informal or illegal sector, which suggests that the sanctions imposed do not serve as a deterrent.

According to a metric prepared by OEFA to assess different aspects of oversight of artisanal fishing, the best performing regional governments, out of the 24 to which the metric was applied, obtained a score of 50 out of 100, while the worst received only 8 points (OEFA, 2015).

The Ministry of Defence, through the General Directorate of Harbour Masters and Coastguards (DICAPI), is responsible for registering, inspecting and monitoring fishers and the fishing fleet, for authorising fishing vessel departures, for authorising the use of coastal waters (for the installation of underwater outlets, for example) and for control and oversight to prevent and combat the pollution of the sea, rivers and navigable lakes.

SERNANP also has responsibilities over aquaculture and fishing in coastal, maritime and inland protected natural areas. The San Fernando, Paracas and Islands, Islets and Guano Capes National Reserves are combined areas of maritime and land territory, and the species protected in their coastal zones are chiefly those associated with the Humboldt Current (for example, birds, sea lions). The integrated management of these protected areas of maritime and land territory in a way that remains close to the traditional sectors and is co-ordinated with all the interested parties offers an example that could be exported to other locations.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation participates in the fisheries sector through the National Water Authority (ANA) which, pursuant to Article 79 of the Water Resources Act (Law No. 29338-2001), is the agency responsible for issuing the permits needed to discharge effluents into the sea, subject to a favourable ruling from the environment and health ministries regarding compliance with the Environmental Quality Standards for Water (ECA-Agua) and the maximum permissible limits (MPLs).

Finally, responsibility for monitoring environmental accidents and contamination of fishery and aquaculture products for human consumption lies with the National Fish Health Service (SANIPES).

Bibliography

Amazon Conservation Association (n/d), “Fact Sheet: Illegal Gold Mining in Madre de Dios, Peru” [online] http://www.amazonconservation.org/pdf/gold_mining_fact_sheet.pdf.

CAMEP (Carnegie Amazon Mercury Ecosystem Project) (2013), Research Brief, No. 1 [online] https://dge.stanford.edu/research/CAMEP/CAMEP%20Research%20Brief%20-%20Puerto%20Maldonado%20English%20-%20FINAL.pdf.

CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) (2015), Sistema de surgencia de la corriente Humboldt en el Perú, October [online] https://chm.cbd.int/database/record?documentID=204050.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organizations of the United Nations) (2010), “Visión general del sector pesquero nacional” [online] ftp://ftp.fao.org/Fi/DOCUMENT/fcp/es/FI_CP_PE.pdf.

Heck, C. (2015), Hacia un manejo ecosistémico de la pesquería peruana de anchoveta, Lima, Environmental Law Society of Peru /Earthjustice/Asociación Interamericana para la Defensa del Ambiente [online] http://www.aida-americas.org/sites/default/files/informe_anchoveta.pdf.

IMARPE (Peruvian Sea Institute) (2010), Informe general de la Segunda Encuesta Estructural de la Pesquería Artesanal Peruana 2003-2005, Callao [online] http://www.imarpe.pe/imarpe/archivos/informes/imarpe_informe_37_num1_2.pdf.

_____ (1997), Encuesta Estructural de la Pesquería Artesanal del litoral peruano, Callao [online] http://biblioimarpe.imarpe.gob.pe:8080/handle/123456789/957.

INEI (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics) (2012), I Censo Nacional de la Pesca Artesanal del ámbito marítimo 2012 [online] http://webinei.inei.gob.pe/anda_inei/index.php/catalog/223.

Ministry of Production (2015), Anuario estadístico pesquero y acuícola 2014, Lima [online] http://www.produce.gob.pe/images/stories/Repositorio/estadistica/anuario/anuario-estadistico-pesca-2014.pdf.

_____ (2013a), Anuario estadístico pesquero y acuícola 2012, Lima [online] http://www.produce.gob.pe/images/stories/Repositorio/estadistica/anuario/anuario-estadistico-pesca-2012.pdf.

_____ (2013b), “PRODUCE: pesca de cerco y arrastre dentro de las cinco millas marinas en el litoral de Tumbes es perjudicial para la sostenibilidad de los recursos marinos” [online] http://www.produce.gob.pe/index.php/prensa/noticias-del-sector/2056-produce-pesca-de-cerco-y-arrastre-dentro-de-las-cinco-millas-marinas-en-el-litoral-de-tumbes-es-perjudicial-para-la-sostenibilidad-de-los-recursos-marinos.

_____ (2013c), “Cifras estimadas en función a las DIREPROS, empresas pesqueras, censo artesanal y otros”, Lima.

OEFA (Agency for Environmental Assessment and Enforcement) (2015), Fiscalización ambiental del sector pesquería a nivel de gobiernos regionales. Informe 2014, Lima.