Chapter 6. Public procurement in Coahuila: ensuring integrity and value for money

In line with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, the present chapter assesses whether Coahuila has developed and implemented effective general standards for public procurement procedures and procurement-specific risk management tools in order to preserve integrity in this activity. Specifically, the chapter looks at newly-developed initiatives such as the Code of Conduct and the Conflict-of-Interest Manifest for suppliers. It then describes the actions undertaken so far to promote a culture of integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers, and civil society. It also evaluates how external stakeholders are involved in the public procurement system with a view to increase its transparency and integrity. Lastly, the chapter analyses levels of transparency of public procurement processes and the application of e-procurement solutions.

Introduction: Corruption risks in public procurement

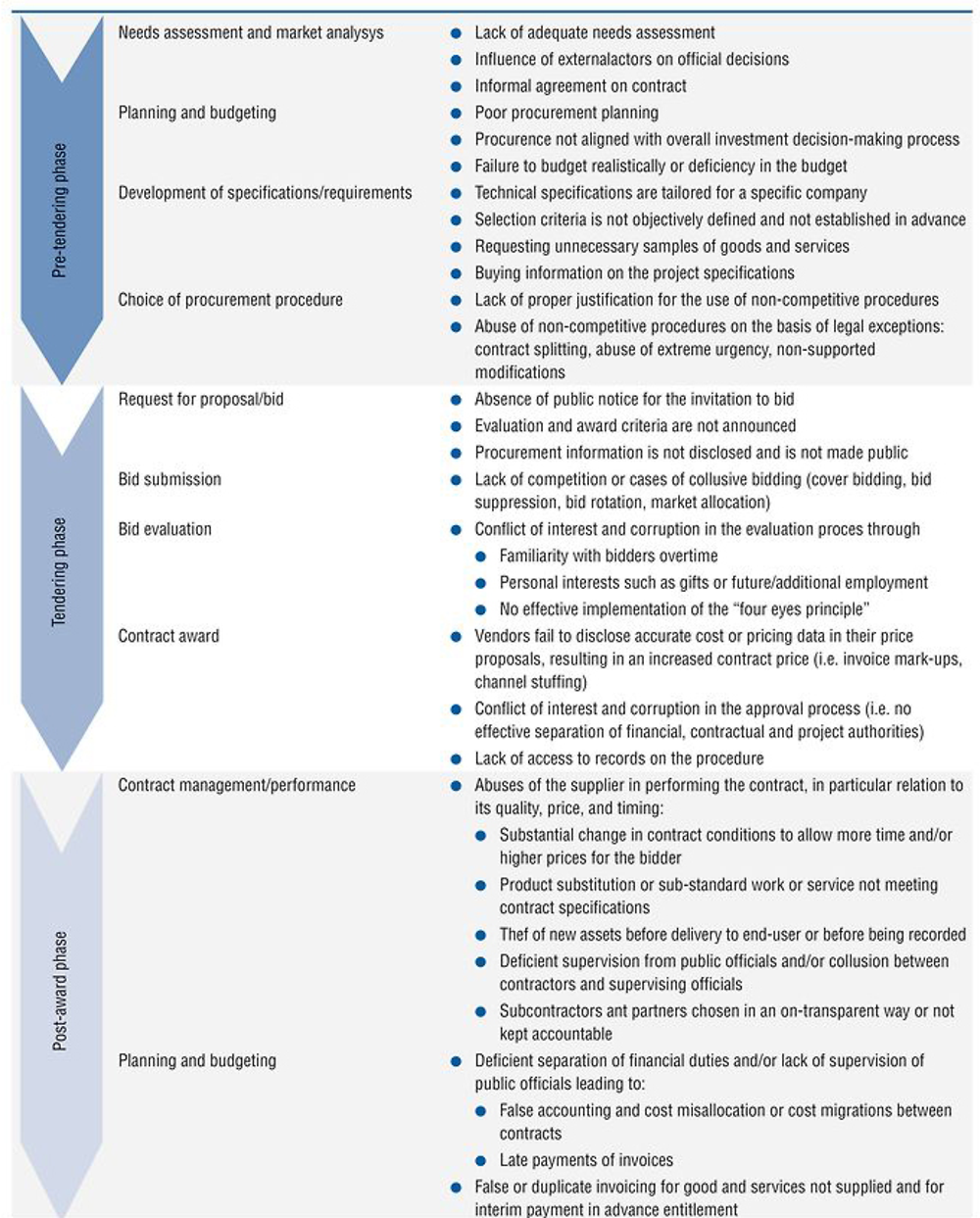

Not all positions and activities in the public sector are the same in terms of potential integrity risks. Some sectors or officials, such as those in justice, tax and customs administrations, audit, inspection, and public procurement, may operate with higher potential risk of conflict of interest and corruption. Public procurement is particularly vulnerable to integrity violations due to the high complexity of activities, the close interaction between the public and private sectors, and the large volume of transactions. Indeed, every year governments spend large sums of public money on procurement contracts. In 2013 alone, for instance, it is estimated that OECD countries spent about 12% of their GDP and 29% of government expenditures on public procurement, which is estimated to be around EUR 4.2 trillion (OECD, 2015d). Unethical practices can occur in all phases of the public procurement cycle however, each phase may be prone to specific finds of integrity risks (see Table 6.1).

The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement (2015) which comprises 12 integrated principles (see Figure 6.1 and Box 6.1) aims to address such risks and outlines some essential measures to be implemented in order to ensure integrity in the public procurement system and to fight corruption related to procurement processes. This chapter assesses the strengths and weaknesses of the public procurement framework of the state of Coahuila de Zaragoza against the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement, and the extent to which the framework identifies and mitigates inherent corruption risks. Consequently, this chapter is organised into three sections covering several principles of the OECD Recommendation, including integrity, transparency, and participation (for more information, please refer to Annex 1): (1) Preserving public integrity through general standards of conduct and procurement-specific risk management tools; (2) Promoting a culture of integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers and civil society; and (3) Enhancing transparency and the disclosure of information around public procurement processes.

Source: OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement. OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/, accessed 24 August 2017.

Source: OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement. OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/.

Preserving public integrity through general standards of conduct and procurement-specific risk management tools

Coahuila’s public procurement system is based primarily on the Law on Acquisitions, Leasing and Services for the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Contratación de Servicios para el Estado de Coahuila, LAACSEC) and the Law on Public Works and Related Services for the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley de Obra Pública y servicios relacionados con las mismas para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, LOPSEC). Both of these laws were revised in March 2016 and include new legal provisions aiming at strengthening transparency and integrity of public procurement processes: (1) a Conflict-of-Interest Declaration (Manifiesto de no conflicto de intereses) – Annex 11 of LAACSEC and Annex 32 of LOPSPEC - and (2) a Code of Conduct (Código de Conducta). Both initiatives target suppliers of the state of Coahuila.

The administrative sanctioning of public servants who take part in corrupt practices is mainly covered by the Law of Responsibilities of Public Servants at state and municipal level of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley de Responsabilidades de los Servidores Públicos Estatales y Municipales del Estado de Coahuila, LRSPEMEC), enacted in 1984. With the approval of the new General Law on Administrative Responsibilities (Ley General de Responsabilidades Administrativas, LGRA), which came into effect in July 2017, the LRSPEMEC was replaced. A key feature of the new LGRA is indeed that it holds the character of general law, and will therefore apply beyond the federal level to public procurement officials across the country.

In addition, Coahuila introduced, in 2012, a Law to Prevent and Punish Corrupt Practices in Public Procurement Processes in the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza and its Municipalities (Ley para Prevenir y Sancionar las Prácticas de Corrupción en los Procedimientos de Contratación Pública del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza y sus Municipios). The latter is similar to the Federal Anti-corruption Law on Public Procurement (Ley Federal Anticorrupción en Contrataciones Públicas, LFACP), which was adopted in June 2012 and directly addresses corruption and fraud in public procurement. The LFACP, however, is applicable only until 19 July 2017, after which it will also be supplanted by the LGRA. In 2014, Coahuila also adopted the Law on Access to Public Information and Protection of Personal Data (Ley de Accesso a la Información Pública y Protección de Datos Personales, LAIP), or Transparency Law. The second section of this Act governs the information that must be proactively made public and the government agencies need to provide upon request, including in the area of public procurement. It also introduces the supplier registry (padrón de proveedores y contratistas).

Using participative techniques, Coahuila should develop a specific Code of Ethics or Conduct and specific guidance for procurement officials, and ensure that specific provisions to public procurement are included in the codes developed by ministries and municipalities.

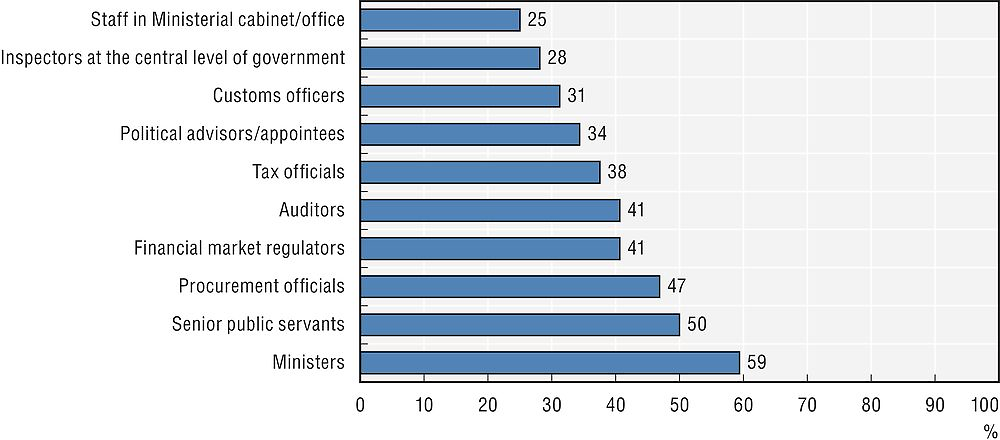

According to the Recommendation, adherents should preserve the integrity of the public procurement system through general standards and procurement specific safeguards and require high standards of integrity for all stakeholders in the procurement cycle. The Recommendation also recommends tailoring general integrity tools to the specific risks of the procurement cycle as necessary, e.g. the heightened risks involved in public-private interaction and fiduciary responsibility in public procurement (OECD, 2015a). According to the 2014 OECD Survey on Management of Conflict of Interest, specific conflict-of-interest policies and rules have for example been developed (see Figure 6.2) for procurement officials in 47% of OECD countries, right after senior public officials (50%) and ministers (59%).

Source: 2014 OECD Survey on Management of Conflict of Interest, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/governance/ethics/2014-survey-managing-conflict-of-interest.pdf.

As described in Chapter 2 on Public Ethics, the Constitution of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza lays out the institutional commitments (public trust, public participation, combatting corruption and impunity, etc.) as well as the constitutional principles and values (efficiency, effectiveness, honesty, fairness, impartiality, integrity, loyalty, legality, leadership, accountability, respect, and transparency) of the public service. Based on these commitments, principles, and values, the state of Coahuila has introduced a Code of Ethics and Conduct for Public Servants in the Executive Branch of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Código de Ética y Conducta para los Servidores Públicos del Poder Ejecutivo del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza). In 2015, it was complemented by a separate Code of Conduct for the Public Servants of the Ministry for Audit and Accountability (Secretaría de Fiscalización y Rendición de Cuentas, SEFIR). However, little attention has been paid in these codes to how they specifically target procurement personnel (or other high-risk positions in their organisations) and no specific Code of Ethics or Conduct has been developed for procurement officials – unlike at the federal level. At the federal level, Mexico recently passed an Ethics Code and Rules of Integrity (Código de Ética y Reglas de Integridad), which includes 17 specific provisions for officials working in the domain of public procurement (paragraph 3), out of 12 domains. These provisions include specific rules for public officials involved in public procurement processes, requiring that they must act in a transparent, impartial, and legal manner, making decisions based on the needs and interest of civil society and providing the best procurement conditions for the state (see Box 6.2).

Public Contracts, Licenses, Permits, Authorisations, and Concessions

The public servant who participates in public contracting or in the granting and providing extensions to licenses, permits, authorisations and concessions, on the grounds of their employment, position, commission or function or through subordinates, should behave with transparency, impartiality, and legality, should orient their decisions towards the needs and interests of society, and should guarantee the best conditions for the state.

The following non-exhaustive list of behaviours threaten these values. It is therefore problematic to:

-

Omit to declare, in accordance with the applicable provisions, possible conflicts-of-interest as well as particular business and commercial links with persons or organisations registered in the Single Registry of Contractors for the Federal Public Administration.

-

Fail to apply the principle of equal competition that should prevail among participants in public procurement processes.

-

Formulate requirements differently from those strictly necessary for the fulfilment of the public service, causing excessive and unnecessary expenses.

-

Establish conditions in the invitations or calls for tenders which confer advantages or provide a differential treatment to certain bidders.

-

Favour certain bidders by considering that they meet the requirements or rules foreseen in the invitations or calls for tender when they do not; simulating the fulfilment of them or contributing to their temporary fulfilment.

-

Help suppliers to fulfil the requirements foreseen in the requests for quotes.

-

Provide undue information about individuals involved in public procurement processes.

-

Be partial in the selection, designation, contracting, and, as the case may be, removal or termination of the contract, in the framework of public procurement processes.

-

Influence decisions of other public servants in order for one participant to benefit from the public procurement processes or from the granting of licenses, permits, authorisations, and concessions.

-

Avoid imposing sanctions on bidders, suppliers, and contractors who violate applicable legal provisions.

-

Sending e-mails to bidders, suppliers, contractors or concessionaires through personal e-mail accounts or accounts which are distinct from institutional e-mail accounts.

-

Meet with bidders, suppliers, contractors, and concessionaires outside the official buildings, except for the proceedings related to on-site visits.

-

Request unsubstantiated requirements for the granting and providing extensions to licenses, permits, authorisations, and concessions.

-

Give inequitable or preferential treatment to any person or organisation in the framework of granting and extending licenses, permits, authorisations, and concessions.

-

Receive or request any type of compensation, offering, treat or gift in the framework of granting and providing extensions to licenses, permits, authorisations, and concessions.

-

Fail to observe the protocol of action in matters of public contracting and providing extensions to licenses, permits, authorisations, concessions, and their extensions.

-

To be a direct beneficiary or through relatives up to the fourth degree of government contracts related to the agency or entity that directs or to which are directed the services.

Source: Ethics Codes and Rules of Integrity, DOF-20-08-2015, www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5404568&fecha=20/08/2015.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, Coahuila should develop specific Codes of Ethics or Conduct for high-risk activities, including public procurement. A specific Code of Conduct for procurement officials would have the advantage of being tailored to the specific risks of the procurement cycle. Coahuila should also ensure that specific provisions to public procurement are included in the codes developed by individual line ministries, such as SEFIR and the municipalities. This recommendation is particularly relevant in the context of the implementation of the new Integrity Rules set out in the LGRA, which invites individual line ministries to revamp their specific Codes of Conduct. In line with the recommendation of Chapter 2, new ministerial (or municipal) codes would need to involve public procurement officials in order to strengthen the sense of ownership and its values throughout the individual line ministries (and municipalities). Experience has shown that governments in Mexico have not consulted targeted audiences while developing such codes in the past, hindering ownership by public officials as well as implementation of those codes.

This specific Code of Conduct for procurement officials should be complementary to the new Protocol of Conduct for Public Servants in Public Procurement, and on the granting and extension of licenses, permits, authorisations, and concessions (Acuerdo por el que se expide el protocolo de actuación en materia de contrataciones públicas, otorgamiento y prórroga de licencias, permisos, autorizaciones y concesiones), included in the LGRA, which seeks to specifically target conflict-of-interest situations for public procurement dealings.

The codes should be complemented with specific guidance on how public procurement officials can and are expected to react when faced with common ethical dilemmas and conflict-of-interest situations that could arise in public procurement processes. Such guidance could consider the current rules-based LAACSEC (Article 73.II for instance) and the Protocol and Codes of Conduct of Coahuila, which provide a foundation for guidance based on principles, values, and ethical reasoning. This guidance should, for instance, list situations which would constitute a material conflict-of-interest for a staff member working with a company submitting a tender. For the development of such guidance, Coahuila may want to consider the example of Australia (see Box 6.3) as well as the Guide developed at federal level to identify and prevent conducts that could constitute a conflict-of-interest for public officials (Guía para identificar y prevenir conductas que puedan constituir conflicto de interés de los servidores públicos). International good practice could also be a source of guidance on these matters. The guide developed at federal level provides a list of high-risk processes, including those related to public procurement and public works (out of nine processes), as well as a table to analyse the risks according to those areas. The codes and the guidance would add to the asset declaration and conflict-of-interest declaration system introduced by the new LGRA.

The government of South Australia’s Department of Planning, Transport, and Infrastructure (DPTI) applies ways to address potential and material conflict-of-interest situations during the procurement process through the Procurement Management Framework. It states that the DPTI staff member should notify the evaluation Panel Chairperson as soon as they notice signs of a conflict-of-interest situation. Even though a potential conflict of interest will not necessarily preclude a person from being involved in the evaluation process, it is declared and can be independently assessed.

It also lists situations which would be considered as a material conflict of interest of a staff in relation to a company submitting a tender including: 1) a significant shareholding in a small private company which is submitting a tender; 2) having an immediate relative (e.g. son, daughter, partner, sibling) employed by a company which is tendering, even though that person is not involved in the preparation of the tender and winning the tender would have a material impact on the company; 3) having a relative who is involved in the preparation of the tender to be submitted by a company; 4) exhibiting a bias or partiality for or against a tender (e.g. because of events that occurred during a previous contract); 5) a person, engaged under a contract to assist DPTI with the assessment, assessing a direct competitor who is submitting a tender; 6) regularly socialising with an employee of tenderer who is involved with the preparation of the tender; 7) having received gifts, hospitality or similar benefits from a tenderer in the period leading up to the call of tenders; 8) having recently left the employment of a tenderer; or 9) considering an offer of future employment or some other inducement from a tenderer.

Source: Procurement Management Framework. Confidentiality and Conflict of Interest, PR115, http://dpti.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/word_doc/0016/162322/PR115_Confidentiality_and_Conflict_of_Interest_-_Procurement_Procedure.docx, accessed 1 June 2016.

While the Code of Conduct and the Conflict-of-Interest Manifest are positive first steps in preventing corruption among suppliers, Coahuila should now leverage those tools in order to better identify integrity risks in public procurement processes.

In order to advance the integrity of the public procurement system, it is also critical to work with external actors, in particular the private sector. The public procurement cycle involves multiple actors and therefore integrity should not be a requirement for public officials alone. This is the reason why the Recommendation (OECD, 2015a) suggests that standards embodied in integrity frameworks or codes of conduct applicable to public-sector employees (such as managing conflict of interest, disclosure of information, or other standards of professional behaviour) be further expanded (e.g. through integrity pacts). For example, integrity standards applicable to public sector employees may be expanded to private sector stakeholders through integrity pacts (OECD, 2016). Integrity pacts are discussed in the second part of this chapter (Promoting a culture of integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers and civil society).

In Coahuila, both public procurement laws, the LAACSEC and the LOPSEC, were revised in March 2016 in order to include new legal provisions aiming at strengthening transparency and integrity of suppliers in the framework of public procurement processes.

-

Indeed, the laws introduced a Conflict-of-Interest Declaration (Manifiesto de no conflicto de intereses), in Annex 11 of LAACSEC and Annex 32 of LOPSEC, as well as (2) a Code of Conduct (Código de Conducta) for suppliers of the state of Coahuila. According to these laws, the suppliers who would like to participate in any public procurement process need to present and comply with the Code of Conduct (Article 42 of the LAACSEC). The law specifies which information should be provided in the framework of the conflict-of-interest declarations, included in the application for the supplier’s registry (padrón de proveedores), which needs to be completed each year (Article 42A of LAACSEC).

-

The LAACSEC also specifies information to include in the Code of Conduct for suppliers (Article 42B): the purpose and scope of the application, the basic requirements related to the responsibilities of suppliers, and sanctions in the case of non-compliance. A Code of Conduct for suppliers was issued following the revision of the laws in March 2016. According to this provision, SEFIR is supposed to issue such a Code of Conduct. It remains unclear if the latter has been developed in a participative manner. As highlighted above, the consultation of targeted audiences, in this case the suppliers, in the framework of the development of the code would have strengthened the sense of ownership and its values throughout the supplier community. A few municipalities, such as Acuña, developed a specific Code of Conduct in addition to the Code developed by SEFIR.

While the Code of Conduct and the Conflict-of-Interest Manifest are positive first steps toward preventing corruption among suppliers, there are several aspects that weaken their potential to achieve the desired impact. The new Code of Conduct could, for instance, benefit from a more balanced approach. Indeed, there is a limit to the benefits of prohibitions, control, and sanctions, and balancing rules-based and values-based approaches is considered to be crucial (OECD, 2009). For the time being, the Code is based almost exclusively on a rules-based approach, neglecting values-based behaviours. The Code of Conduct seems to the supplier community to suggest that they are inherently corrupt. This situation is very similar in the case of the LAACSEC and the Law to Prevent and Punish Corrupt Practices in Public Procurement Processes in the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza and its Municipalities (Ley para Prevenir y Sancionar las Prácticas de Corrupción en los Procedimientos de Contratación Pública del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza y sus Municipios), which are both strongly focused on prohibitions, control, and sanctions. The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement emphasises the importance of not creating undue fear of consequences or risk-aversion in the procurement workforce or supplier community (OECD, 2015a). Against that background, Coahuila may want to adopt a more values-based approach rather than emphasising prohibitions.

In addition, Coahuila should also better leverage the Conflict-of-Interest Declaration and the Code of Conduct to raise awareness on corruption risk in the framework of public procurement processes and to identify integrity risks in public procurement processes. SEFIR and the Ministry of Finance (Secretaría de Finanzas, SEFIN) should, for instance, make sure to inform the supplier’s community about the new Code of Conduct in an appropriate way. At the time of preparation of the review, the Code of Conduct is not visible on the SEFIR or SEFIN websites, and it is not included in the documents provided by SEFIR in the framework of application for registration in the supplier’s registry. This may be one reason why very few suppliers know about the new Code. Coahuila may also want to make sure that the objectives and content of both tools are included in integrity training for the supplier community. Once Coahuila has developed its Code of Ethics or Conduct for procurement officials (see recommendation above), SEFIR will need to make sure to explain the differences between both codes in order to avoid confusion among public officials and suppliers, as mentioned in Chapter 2 of this review.

In order for the information to be helpful to fight against corruption and decrease conflict-of-interest cases, the information contained in the Conflict-of-Interest Manifests provided by suppliers needs to be cross-checked with the asset declarations (declaración de situación patrimonial) and interests declaration (declaración de íntereses) of public procurement officials (see Chapter 2 for more information). The verification of the information would be in line with Article 23 of the LAACSEC, which foresees the possibility of undertaking consultations in order to cross-check the information provided in the framework of application for registration in the supplier’s registry. Cross-checking such information would help ensure that the information provided by suppliers and public procurement officials are coherent. This could be one of the roles of the recommended Specialised Unit for Ethics and Prevention of Conflicts of Interest of SEFIR, in case it is introduced (see Chapter 2 for more information). It is unclear if public procurement officials and contracting authorities have access to the information provided in those Manifests. In case they do not have access to this information, it may be difficult for public procurement officials to verify any relevant information and to follow up on any apparent conflict of interest.

Also, while the initiative of creating such a Manifest is an important step towards identifying conflict-of-interest situations, it would be more efficient to request suppliers and bidders to fill in the Manifest only in the case of potential, real and apparent conflict. In order to do so, the Manifest should provide a clear definition of conflict of interest (potential, real and apparent conflict); in line with relevant laws (see Chapter 2). Coahuila should also provide the possibility of updating the Manifest throughout the year (and incite suppliers to do so) and not only while applying to the supplier’s registry once a year (according to Article 25 of the LAACSEC, the Certificate of Competence [Certificado de Aptitud] is only valid for one year). Also, the Manifest should be complemented by a specific guide for public procurement officials, internal control bodies, suppliers, and bidders on how to use those Manifests, by the creation of a FAQ section, as well as by the identification of a focal point in charge of advising public servants and external actors.

Coahuila would also need to evaluate the impact of the adoption of the new LGRA, which introduces the Procurement Protocol and a Manifest (Manifiesto que podrán formular los particulares en los procedimientos de contrataciones públicas, de otorgamiento y prórroga de licencias, permisos, autorizaciones y concesiones). The Manifest is for individual natural persons to declare or deny any businesses, work, personal, or family links or relationships of consanguinity or affinity to the fourth degree with public servants specified in the Protocol each time they are involved in public procurement processes, grants and extensions of licenses, permits, and authorisations. The Manifest can be filled in online (www.manifiesto.gob.mx) and can be updated anytime.

In order to preserve public integrity, Coahuila should develop risk assessment tools to identify and address the threats to the proper functioning of the public procurement system and make sure that contracting authorities are implementing them.

Risk management tools can map, detect, and mitigate corruption risks and preserve public integrity throughout the public procurement cycle. According to the OECD Recommendation, adherents should develop specific risk assessment tools to identify and address threats to the proper functioning of the public procurement system. Where possible, tools should be developed to identify risks of all sorts – including potential mistakes in the performance of administrative tasks and deliberate transgressions – and bring them to the attention of relevant personnel, providing an intervention point where prevention or mitigation is possible. Adherents should also publicise risk management strategies, for instance, systems of red flags or whistleblower programmes, and raise awareness and knowledge of the procurement workforce and other stakeholders about the risk management strategies, their implementation plans and measures set up to deal with the identified risks (OECD, 2015a). Public authorities, including contracting authorities, should minimise the opportunity for fraud and corruption as much as possible through developing a sound control environment and putting in place the proper control activities to mitigate the relevant risks.

Coahuila has progressively introduced an internal control system, since the 2013 adoption of the Internal Control General Standard (Norma General de Control Interno). In 2016, Coahuila also adopted Manuals on Internal Control (Manual administrativo de aplicación general en materia de control interno and the Manual operativo del Sistema de evaluación del control interno). The manuals are complemented with a matrix of risk management (Matriz de Administración de Riesgos). Interviews carried out during the fact-finding mission nevertheless showed that public entities have not yet implemented these recently-developed internal control and risk management tools. They also lack specific Working Programmes of Risk Management (Programa de Trabajo de Administración de Riesgos). Unlike at the federal level, public procurement is not recognised as a process particularly vulnerable to corruption, and on which public entities should focus in the framework of their risk management systems. Interviews also suggest that there are no awareness raising or capacity-building programmes around risk management, including corruption risks.

As such, Coahuila should make sure that contracting authorities are implementing the internal control and risk management system, strategy and tools that it has developed. Coahuila needs to publicise the manuals and tools on internal control and risk management and raise awareness and knowledge of the public officials, including the procurement workforce and other stakeholders, on those strategies, including through trainings. Coahuila also may want to consider the introduction of risk management tools that identify and address specific public procurement risks. Coahuila could, for instance, develop a specific checklist listing the risks linked to the public procurement activity, in particular the corruption risks. SEFIR could also develop specific guidance on how the five internal control components (control environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication and monitoring) can link with the public procurement process. It could also provide a checklist for contracting authorities to verify that the five components are being taken into account in their daily activities and that the risks are evaluated and mitigated (see Table 6.2).

Finally, SEFIR may want to consider the development of specific guidance for the establishment of a red flags system for corruption in procurement. Red flags are warning signals or hints of something that needs extra attention to exclude or confirm potential fraud and corruption. Red flags may be individual- or organisation-related (see Box 6.4). Those tools should be accompanied by specific templates to facilitate their implementation in the daily business of the public procurement entities and use digital solutions and technologies to the greatest extent possible.

World Bank red flags of fraud and corruption in procurement:

-

Complaint from bidders or other parties

-

Multiple contracts below procurement threshold

-

Unusual bid patterns

-

Seemingly inflated agent fees

-

Suspicious bidder

-

Lowest bidder not selected

-

Repeated awards to the same contractor

-

Changes in contract terms and value

-

Multiple contract change orders

-

Poor quality works and/or services

Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy red flags:

-

Physical losses

-

Unusual relationship with suppliers

-

Manipulation of data

-

Photocopied documents

-

Incomplete management/audit trail

-

IT-controls of audit logs disabled

-

Budget overspends

-

IT-login outside working hours

-

Unusual invoices (e.g. format, numbers, address, phone, VAT number)

-

Vague description of goods/services to be supplied

-

Duplicate/photocopy invoice

-

High number of failed IT logins

-

Round sum amounts invoiced

-

Favoured customer treatment

-

Sequential invoice numbers over an extended period of time

-

Interest/ownership in external organisation

-

Non-declaration of interest/gifts/hospitality

-

Lack of supporiting records

-

No process identifying risks (e.g. risk register)

-

Unusual increases/decreases

Source: OECD (2015), Effective Delivery of Large Infrastructure Projects: The Case of the New International Airport of Mexico City, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Promoting a culture of integrity among public procurement officials, potential suppliers, and civil society

Coahuila should support the implementation of new integrity standards by streamlining and updating the legislation and by developing and implementing adequate communications strategies.

A law, a protocol, or code alone cannot guarantee ethical behaviour. It can offer written guidance on expected behaviour by outlining the values and standards to which public procurement officials should aspire. But to be effectively implemented, adequate communication strategies, including awareness-raising activities, should be developed. A clear communication strategy to raise awareness with regard to integrity policies and available tools and guidance, ideally, makes use of different existing and innovative channels of communication. Also, it should target internal stakeholders (public procurement officials) as well as external stakeholders (the private sector, civil society organisations, and individuals), in particular when it comes to public procurement. External communication of the relevant laws and codes of conduct can support key stakeholders in their commitment to integrity. The role of external actors, in particular users of public services and the private sector, is indeed critical to maintaining the integrity of government operations.

The 2012 adoption of a Law to Prevent and Punish Corrupt Practices in Public Procurement Processes in the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza and its Municipalities (Ley para Prevenir y Sancionar las Prácticas de Corrupción en los Procedimientos de Contratación Pública del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza y sus Municipios) illustrates the commitment of Coahuila to fight corruption in the area of public procurement. This law is complemented with integrity and anti-corruption provisions included in the public procurement laws, as well as provisions included in Coahuila’s Transparency Law. For now, the legislation related to fighting corruption in public procurement is fragmented and does not facilitate implementation by public procurement officials, suppliers, and citizens. In addition, Coahuila will need to implement the new LGRA, which includes a new Protocol of Conduct for Public Servants in Public Procurement, including a Manifest for suppliers. Those two initiatives which Coahuila’s will have to implement as of July 2017 may duplicate some of the existing efforts developed by the state government. The legislative fragmentation and potential duplication of initiatives and tools creates confusion and does not facilitate their proper implementation. As such, Coahuila may want to consider streamlining the current legislation related to the fight of corruption in public procurement.

In addition, Coahuila should develop and implement targeted communication strategies, in particular in regards to the recent tools (Coahuila’s Conflict-of-Interest Declaration and Code of Conduct for suppliers) as well as the new tools developed at federal level (the Procurement Protocol and the Manifest). The interviews carried out during the fact-finding mission showed that the recent tools were not very well-known among public officials and suppliers and that the latter were, in some cases, critical of them. The objectives, content, usage, and benefits of the Conflict-of-Interest Declaration and the Code of Conduct for suppliers should be communicated to the public procurement workforce, and manuals and guidelines could also be created to help public procurement officials and suppliers to understand and apply the new provisions. SEFIR should also start raising awareness among public procurement officials, suppliers, and other relevant external actors about the new tools developed at federal level. In the communication strategies, emphasis should be placed on both their rights and their duties to abide by the rules. The recent and new integrity standards and codes should be included in the trainings (see further for more details) and could be attached to requests for proposals and calls for applications or generally mailed to all vendors. The inclusion of the Conflict-of-Interest Declaration in the application for the supplier’s registry can be considered a good practice. Raising awareness externally about public officials’ integrity commitments is also crucial as a pre-requisite to encourage the participation of citizens in public procurement processes and in strengthening accountability and increasing institutional trust.

Coahuila should strengthen the culture of integrity among the procurement workforce by developing a clear integrity capacity strategy and implementing tailored training for procurement officials.

According to the Recommendation, integrity training programmes need to be developed for the procurement workforce, both public and private, to raise awareness about integrity risks, such as corruption, fraud, collusion and discrimination, develop knowledge on ways to counter these risks and favour a culture of integrity to prevent corruption (principle of integrity). The Recommendation also underlines the need to ensure that procurement officials meet high professional standards for knowledge, practical implementation and integrity by providing a dedicated and regularly updated set of tools, for example, sufficient staff in terms of numbers or skills, recognition of public procurement as a specific profession, certification and regular trainings, integrity standards for public procurement officials (OECD, 2015a). Human Resource Management (HRM) is indeed particularly relevant in promoting and ensuring integrity. Public ethics and the management of conflicts of interest are about directly or indirectly changing the behaviour of an organisation’s human resources. As a result, HRM policies are both part of the problem and part of the solution in promoting integrity in the public administration, including among public procurement officials.

As specified in Chapter 2 of the review, SEFIR is responsible for the overall framework of training on integrity issues and co-ordination among state ministries and agencies, including SEFIN. It co-ordinates a one-day training on management of conflicts-of-interest. According to the information provided by Coahuila, SEFIR has not developed capacity-building programmes specific to integrity issues or corruption prevention in public procurement. It remains unclear which trainings are being provided to procurement officials and if those trainings include specific modules on managing integrity and corruption risks. Specific training videos on integrity for public officials, including public procurement officials, do not exist either. There seems to be no comprehensive integrity capacity building strategy for public officials, including public procurement officials. The State Programme of administrative modernisation, audit, and accountability for the period 2011-2017 (Programa Estatal de Modernización Administrativa, Fiscalización y Rendición de Cuentas) mentions the development of the State Capacity Programme (Programa Estatal de Capacitación), but it has not been defined so far, according to the latest Government Report of Coahuila 2011-2017 (Cuarto Informe de Gobierno 2011-2017) published in November 2015. Only a survey aiming at detecting the needs in terms of capacity building (Encuesta de Detección de Necesidades de Capacitación, DNC) has been undertaken in 2014. The results of the survey are not available online.

As such, Coahuila could consider developing a clear integrity capacity-building strategy for the public administration, including public procurement officials, along with a certification system. This strategy could be part of the State Capacity Programme and should take into account the diagnostic resulting from the DNC. It should also take into account the specificities of high-risk areas such as public procurement. Coahuila could also envisage the development of a public procurement capacity strategy, which would include specific initiatives to strengthen the culture of integrity among the procurement workforce. In the framework of those capacity strategies, Coahuila could consider developing and implementing tailored training programmes for public procurement officials. Those specific trainings should be included in the framework of the induction trainings developed for new employees for instance and specific courses should be developed to present the recent and new provisions and tools (the latter could be implemented through e-learning solutions). The specific trainings should ideally lead to certification. Such strategy would not only strengthen the integrity of public officials, but would also contribute to professionalising the workforce and to improving its performance. In Germany, specific integrity training has been developed for public procurement officials (see Box 6.5).

The Federal Procurement Agency is a government agency which manages purchasing for 26 different federal authorities, foundations, and research institutions that fall under the responsibility of the Federal Ministry of the Interior. It is the second largest federal procurement agency after the Federal Office for Defence Technology and Procurement.

The Procurement Agency has taken several measures to promote integrity among its personnel, including support and advice by a corruption prevention officer (“Contact Person for the Prevention of Corruption”), the organisation of workshops and training on corruption, and the rotation of its employees.

Since 2001, it is mandatory for new staff members to participate in a corruption-prevention workshop. They learn about the risks of getting involved in bribery and the briber’s possible strategies. They also learn how to behave when these situations occur; for example, they are encouraged to report it (or to “blow the whistle”). Workshops highlight the central role of employees whose ethical behaviour is an essential part of corruption prevention. About ten workshops took place with 190 persons who provided positive feedback concerning the content and the usefulness of the training. The involvement of the Agency’s “Contact Person for the Prevention of Corruption” and the Head of the Department for Central Services in the workshops demonstrated to participants that corruption prevention is one of the priorities for the agency. In 2005 the target group of the workshops was enlarged to include not only induction training but also ongoing training for the entire personnel. Since then, six to seven workshops are being held per year at regular intervals, training approximately 70 new and existing employees per year.

Another key corruption prevention measure is the staff rotation after a period of five to eight years in order to avoid prolonged contact with suppliers, as well as improve motivation and make the job more attractive. However, the rotation of members of staff still meets with difficulty in the Agency. Due to a high level of specialisation, many officials cannot change their organisational unit, their knowledge being indispensable for the work of the unit. In these cases alternative measures such as intensified (supervisory) control are being taken.

Source: OECD (2016). Towards Efficient Public Procurement in Colombia: Making the Difference, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252103-en.

One pre-requisite for the implementation of such a public procurement capacity strategy is the identification of the public procurement workforce, in particular the number of officials working in the area of public procurement. It seems that Coahuila has not introduced a specific tool to identify those public procurement officials, unlike at the federal level. Following a series of Executive Orders by the President of Mexico, Mexico has indeed created a Registry of Public Servants of the Federal Public Administration who are involved in public procurement processes and other high-risk processes in terms of corruption (Registro de servidores públicos de la Administración Publica Federal que intervienen en procedimientos de contrataciones públicas). Public officials listed in the registry are obliged to obtain adequate certifications in order to ensure their integrity and performance. Coahuila may want to consider introducing such a tool in order to have a better overview of public procurement officials, to manage certifications, to target integrity and public procurement trainings and to cross-check information (included in conflict-of-interest declarations for instance).

As stressed in the OECD Recommendation, the preservation of integrity of the public procurement system also requires integrity training requirements for supplier personnel (OECD, 2015a). Therefore, Coahuila may also include the supplier’s needs in its future integrity capacity building strategy and public procurement capacity strategy, by developing and proposing specific trainings for suppliers on issues related to integrity and the fight against corruption in the framework of public procurement processes. Those trainings and information actions could be developed and undertaken jointly with the business chambers and suppliers associations.

Coahuila should further engage with the private sector, developing co-operation agreements and integrity pacts in an effort to minimise corruption risks.

In order to preserve the integrity of the public procurement system, it is critical to work with external actors, in particular the private sector. The public procurement cycle involves multiple actors and therefore integrity is not a requirement for public officials alone. Just as the public sector has the responsibility to take measures on its end, so does the private sector. Private companies often have their own integrity system in place, and many countries engage with private sector actors to instil integrity in public procurement. For example, integrity standards applicable to public sector employees may be expanded to private sector stakeholders through integrity pacts (OECD, 2016). The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement underlines the need to develop requirements for internal controls, compliance measures, and anti-corruption programmes for suppliers, including appropriate monitoring. It stresses the need for procurement contracts to contain “no corruption” warranties and measures to verify the truthfulness of supplier’s warranties that they have not and will not engage in corruption in connection with the contract. According to the OECD Recommendation, such programmes should also require appropriate supply-chain transparency to fight corruption in subcontracts and integrity training for supplier personnel (OECD, 2015a).

Coahuila’s Law to Prevent and Punish Corrupt Practices in Public Procurement Processes in the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza and its Municipalities (Ley para Prevenir y Sancionar las Prácticas de Corrupción en los Procedimientos de Contratación Pública del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza y sus Municipios) takes into account the role of the private sector in the fight against corruption. For example, it foresees the development of co-operation agreements with chambers of commerce or other industrial organisations in order to guide them in the development of internal control tools and integrity programmes to ensure the development of an ethical culture (Article 12). The law even invites contracting authorities to consider international best practices related to anti-corruption in business transactions (Article 12). These provisions are in line with the President’s 2015 Executive Orders which mandated the Federal Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de Función Pública, SFP) to increase collaboration with the private sector in relation with transparency and the fight against corruption as well as the active participation of citizens in the identification of vulnerable processes and procedures through the development of co-operation agreements with chambers of commerce and civil society organisations. However, there is no evidence on the number of co-operation agreements that have been signed in Coahuila. Coahuila should therefore support the development of such agreements and ensure the implementation of joint actions. At the federal level these joint actions include sharing diagnostics, statistics, and other relevant information, identifying and communicating on good practices in terms of transparency and the fight against corruption, promoting sector-specific initiatives such as the initiative to strengthen the monitoring of public works, and facilitating dialogue fora on issues related to integrity and public ethics, as well as the prevention of conflicts of interest.

In Coahuila, public procurement contracts do not contain “no corruption” warranties and measures to verify the truthfulness of suppliers’ warranties that they have not engaged and will not engage in corruption in connection with the contract either (also known as “integrity pacts”). Integrity Pacts are agreements between the government agency offering a contract and the companies bidding for it that they will abstain from bribery, collusion, and other corrupt practices for the extent of the contract. Coahuila’s Public Procurement Law, unlike the Federal Public Procurement Law, does not foresee such integrity pacts (pactos de integridad). This instrument is considered a good practice and it is recommended by the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement and the OECD Guidelines on Fighting Bid Rigging because it makes the legal representatives of firms aware of and directly accountable for the unlawful behaviour (OECD, 2015b). In case Coahuila envisages the introduction of such integrity pacts, the signed declarations of bidders could be published on the federal e-procurement system CompraNet, for tenders involving federal funds, or any other website aiming at strengthening transparency and fighting against corruption. Coahuila could consider developing requirements for internal controls, compliance measures, and anti-corruption programmes for suppliers.

Coahuila should create opportunities for direct involvement of civil society in the public procurement processes by implementing the social witness programme and other monitoring tools.

Creating a culture of integrity and openness in the public sector is also achieved through the involvement of citizens, experts, and civil society in the policy making process through forms of “direct social control”. The OECD Recommendation echoes this statement and recommends the provision of direct opportunities for involvement of relevant external stakeholders in the procurement system with a view to increase transparency and integrity while assuring adequate scrutiny, provided that confidentiality, equal treatment, and other legal obligations in the procurement process are maintained (OECD, 2015a). Those opportunities can be, for instance, provided through social witnesses, usually members of a non-governmental organisation (NGO), who are invited to observe one or several parts of the procurement process. Social witnesses have the opportunity to raise concerns about corrupt behaviour and to provide recommendations for increasing the integrity of the process. Social witnesses are third parties deemed to have no conflict-of-interest in procurement procedures, and whose task is to observe the tender process in order to enhance its accountability, legality, and transparency (OECD, 2015b).

As presented in Chapter 5 of this review, Coahuila adopted a specific Law on Civic Participation in 2001 (Ley de Participación Ciudadana para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza), which aims to support Coahuila citizens’ right to participate in public life as well as to promote policies for community development. Coahuila’s Law to Prevent and Punish Corrupt Practices in Public Procurement Processes in the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza and its Municipalities (Ley para Prevenir y Sancionar las Prácticas de Corrupción en los Procedimientos de Contratación Pública del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza y sus Municipios) takes into account the role of civil society in the monitoring of public procurement processes. It requires contracting authorities to inform citizens on the use of goods and the expenses and investments of the resources of each administration (Article 14). The Transparency and Access to Information Law (Ley de Acceso a Información Pública y Protección de Datos Personales para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza), referred to in Chapter 5 of this review, specifies that the public administration needs to create and use systematic and advanced technology systems and adopt new tools in order for citizens to consult information in a direct, simple and quick manner (Article 8). The Transparency Law also invites public authorities to establish communication channels with citizens through social networks and digital platforms that would allow them to participate in the decision-making process (Article 53). In line with these provisions, Coahuila developed the SITODEM website (more information in the next section) in order to strengthen the transparency and the oversight related to public works.

Even if the legal framework acknowledges the role of civil society in the monitoring of public procurement processes, there currently exist only a few opportunities for direct involvement of relevant external stakeholders in the procurement system with a view to increase transparency and integrity.

As introduced in Chapter 5, a few initiatives have been developed in the framework of SEFIR’s Institutional Programme on Social Monitoring/Control. One initiative, developed by SEFIR in co-operation with the Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, UAdeC, focuses on the supervision of public works, in particular by students. In October 2016, over a two-week period, students were tasked with measuring the quality of 83 public works projects and writing audit reports. The information included in the latter served to update the SITODEM website. This initiative contributed to strengthening the transparency, integrity, and accountability of public procurement processes, but is still implemented on an ad hoc basis. Coahuila should create and institutionalise more opportunities, by accelerating the introduction of social witnesses (testigos sociales) for public procurement processes and using the experience of Mexico at federal level as a model (see Box 6.6). Indeed, the LAACSEC and the LOPSEC were amended on April 2017 to introduce the figure of the social witness.

At federal level, social witnesses are required to participate in all stages of public tendering procedures above certain thresholds, since 2009. These thresholds are MXN 350 million (approximately USD 17 million) for goods and services and MXN 710 million (approximately USD 34 million) for public works in 2015. Social witnesses may also participate in public tendering procedures below the legal threshold, direct award procedures and restricted tendering if it is considered appropriate by SFP. Social witnesses are selected by the Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de la Función Pública, SFP) through public tendering (Convocatoria pública para la selección de personas físicas y morales a registrar en el padrón público de testigos sociales) and selected witnesses enter a pool (Padrón Público de Testigos Sociales) for a period of three years. Their names are being published online: As of October 2016, SFP had registered 25 social witnesses for public procurement projects, six Civil Society Organisations and 19 individuals. The social witnesses are certified and their performance is evaluated by the ministry (unsatisfactory performance potentially results in their removal from the registry). They also get certified and compensated for their services. When a federal entity requires the involvement of a social witness, SFP designates one from the preselected pool. Following their participation in procurement procedures, social witnesses issue a final report providing comments and recommendations on the process. These reports are made available to the public through the Mexican federal e-procurement platform, CompraNet.

Source: OECD (2013), Public Procurement Review of the Mexican Institute of Social Security: Enhancing Efficiency and Integrity for Better Health Care, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264197480-en.

As mentioned in the OECD Public Procurement Review of the Mexican Institute of Social Security: Enhancing Efficiency and Integrity for Better Health Care, SFP notes that “the monitoring of the most relevant procurement processes of the federal government through social witnesses has had an impact in improving procurement procedures by virtue of their contributions and experience, to the point that they have become a strategic element for ensuring the transparency and credibility of the procurement system”. An OECD-World Bank Institute study (2006) indicates that the participation of social witnesses in procurement processes of the Federal Electricity Commission (Comisión Federal de Electricidad, CFE) created savings of approximately USD 26 million in 2006 and increased the number of bidders by over 50% (OECD, 2013). Coahuila should nevertheless take into account the risk of corruption within this programme. The bribing of social witnesses is also a risk to be considered. In order for social witness programmes to be effective, social witnesses need to have access to specific training courses, because they must have the necessary background and experience to enable them to provide expert procurement advice to public procurement officials (OECD, 2015b). Trainings could be complemented by specific guides such as at the federal level (Guía anual de acciones de participación ciudadana) and good practices.

Enhancing transparency and the disclosure of information around public procurement processes

Coahuila should consolidate the information related to public procurement through a unique online portal and ensure the visibility of the flow of public funds, from the beginning of the budgeting process through the public procurement cycle, in order to facilitate an adequate level scrutiny of public procurement processes.

Integrity and transparency of public procurement systems are closely linked. Transparency and the disclosure of information around public procurement processes contribute to identifying and decreasing cases of mismanagement, fraud and corruption and is therefore a key accountability mechanism for integrity. The OECD Recommendation therefore encourages adherents to ensure an adequate degree of transparency of the public procurement system in all stages of the procurement cycle and 1) promote fair and equitable treatment for potential suppliers by providing an adequate and timely degree of transparency at each phase of the public procurement cycle; 2) allow free access, through an online portal, for all stakeholders, including potential domestic and foreign suppliers, civil society and the general public, to public procurement information; and 3) ensure visibility of the flow of public funds, from the beginning of the budgeting process throughout the public procurement cycle (OECD, 2015a). It also should be noted that excessive transparency may facilitate anticompetitive agreements (OECD, 2015b).

As explained in Chapter 5 of this review, issues related to transparency and access to information are covered by Coahuila’s Transparency and Access to Information Law (Ley de Acceso a Información Pública y Protección de Datos Personales para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza), which was most recently reformed in March 2016. It provides an extensive list of information which each administration, including contracting authorities, must provide proactively. In terms of public procurement, the Law foresees the publication of the supplier’s registry (padrón de proveedores y contratistas), the results of direct awards, restricted tenders and any other procurement processes (Article 21). In terms of public works, the Law foresees the publication of the construction companies having won a public works contract, the name of the person monitoring the public works, and the dates and the resources related to each public work (Article 41). The documents related to public procurement that need to be accessible to the public are also listed in Article 42 of the LAACSEC. The latter underlines the need to publish, through e-procurement tools, the following information: tender notifications, the terms of the tenders, the Conflict-of-Interest Declaration, documents related to clarification meetings and field visits, and other relevant information.

In line with the Transparency Law, Coahuila has introduced the SITODEM portal (Sistema de Información y Transparencia de Obras para el Desarrollo Metropolitano) to geo-reference expenditures (http://sitodem.sefircoahuila.gob.mx/). It presents information linked to the Integral System of Public Investment, including the names of approved public works, their cost, the responsible departments, beneficiaries, auditors, the pictures of the finished work, and the report of social comptrollership (contraloría social). However, it does not include information about the contractor or the suppliers. As mentioned in Chapter 5, SITODEM does not provide information on the progress of the public work(s), in real time. SITODEM is listed as one of Coahuila’s transparency initiatives on the Transparencia Focalizada website, along with the live transmission of tenders (see further) as well as the supplier’s registry (www.transparenciafocalizada.cdmx.gob.mx/). SITODEM is similar to the federal Transparencia Presupuestaria website (www.transparenciapresupuestaria.gob.mx/), which includes a module on public works (Obra Pública Abierta). The latter also does not provide information on the suppliers and contractors. The SITODEM portal is managed by four auditors of SEFIR’s Verification Directorate (Dirección de Verificación), who undertake field visits in order to monitor the implementation of public works.

In order to strengthen the transparency and the oversight of public procurement processes, Coahuila has also introduced the live transmission of tenders as of 2011. According to representatives of Coahuila, the live transmission of tenders has reduced the number of disagreements and complaints. The live transmission goes beyond the Public Procurement Protocol included in the new LGRA, which foresees the taping of phone calls and the videotaping of meetings. It remains unclear if the live transmission of tenders is compulsory for all public procurement processes, given that it is included neither in the LAACSEC nor in the Transparency Law of Coahuila. Introducing live transmission indeed only makes sense if all processes are being transmitted in order to ensure full transparency.

The third initiative related to public procurement listed on the Transparencia Focalizada website is the supplier’s registry (Padrón de Proveedores y Contratistas de la Administratación Pública Estatal), introduced by the Transparency Law (Article 21) as well as in the LAACSEC (Article 22) in 2012. The supplier’s registry, managed by SEFIR, includes 936 suppliers and 322 contractors (as of January 2017) as well as the following information: the name and address of the supplier/contractor, the expertise, the registry number, the date of entry, and the validity of the registration. It does not provide information on the number of contracts that have been awarded to each of the suppliers registered. In order to be included in the registry, suppliers have to fill in a registration form, which includes a Conflict-of-Interest Declaration (Manifiesto de no conflicto de intereses) and other information (listed in Article 23 of the LAACSEC). On the basis of the information provided, SEFIR issues a Certificate of Competence (Certificado de Aptitud), valid for one year. For the time being, the registration cannot be completed online, though online registry is currently foreseen by Article 23 of the LAACSEC. The purpose of the supplier registry is for the state government to make sure that the potential suppliers are formal and legal companies with the capacity to deliver what they offer. This is a legitimate interest of the state of Coahuila, and would be undermined if unregistered companies were given contracts. Therefore, Coahuila should ensure unlisted companies are not contracted and, when they are, that the public officials responsible are sanctioned.

Coahuila has strengthened the transparency of its procurement system by introducing the initiatives mentioned above, but information is sometimes incomplete (see above) and scattered. In order to strengthen the clarity of information, Coahuila should consolidate the information related to public procurement through a unique online portal or by introducing a specific public procurement page on the Transparency website of Coahuila (Coahuila Transparente: www.coahuilatransparente.gob.mx/). This recommendation is in line with the analysis made in Chapter 5 of this review. The consolidated page could contain the information on the public procurement system (e.g. institutional frameworks, laws and regulations), which is currently on SEFIR’s page; the specific procurement (e.g. procurement forecasts, calls for tender, award announcements), which are currently unavailable either on the websites of SEFIR or SEFIN (according to Article 51 of LAAACSEC, calls for tender need to be published only once in a major newspaper); and the performance of the public procurement system (e.g. benchmarks, monitoring results), which are currently available on SEFIN’s page. Coahuila should in particular ensure that tender notifications are published in a transparent way and are accessible to all potential competitors. It remains indeed unclear where the tender notifications not involving federal funds are being published. According to SEFIR, the tender notification involving federal funds are indeed published on the federal e-procurement system CompraNet. In addition, Coahuila needs to make sure that tender documents can be accessed for free. According to the public procurement law (Article 51 of the LAACSEC) tender documents are not always free of charge. This hinders the access to procurement opportunities for potential competitors of all sizes and weakens the transparency and integrity of public procurement processes.

Coahuila should also ensure the visibility of the flow of public funds, from the beginning of the budgeting process to the end of the public procurement cycle in order to allow stakeholders to understand government priorities and spending, and to allow policy makers to organise procurement strategically. Even though SITODEM is linked to the Integral System of Public Investment of Coahuila, it does not allow stakeholders to visualise the implementation of the budget through public procurement processes and the progress of public works. Coahuila could therefore upgrade the SITODEM tool in order to strengthen this link. Representatives of SEFIR and SEFIN also mentioned the development of a tool that allows linking the implementation of the budget with public procurement processes. By doing so, both SEFIR and SEFIN should make sure to link it to relevant SEFIN and SEFIR websites in order to avoid duplication and to help users to find the relevant information. In case SEFIR would like to make information available in real time on its SITODEM portal and provide more information on the evolution of the project and related contracts, it would need to allocate more staff to the SITODEM project.

The publication of information related to the number of contracts per supplier or the amount of the awarded contracts per supplier could also help to identify potential corruption issues. A complaint box (buzón de quejas) could also be foreseen in order to facilitate complaint processes with regard to public procurement processes. These are aspects that Coahuila should take into account while developing the new supplier registry (Registro Estatal de Proveedores y Contratistas, REPROCO), which aims at not only serving as a registration platform for suppliers, but will also be used to archive all digital records.

Coahuila should continue maximising transparency in competitive tendering and take precautionary measures to enhance integrity, in particular for exceptions to competitive tendering.

By providing an adequate and timely degree of transparency in each phase of the public procurement cycle, in particular during the tendering processes, contracting authorities can reduce the corruption risks. As specified in Table 6.1 on corruption risks associated with the different phases of the public procurement cycle, the choice of the procurement procedure is an important corruption risk. Competitive procedures should be the standard method for conducting procurement as a means of driving efficiencies, fighting corruption, obtaining fair and reasonable pricing, and ensuring competitive outcomes. If exceptional circumstances justify limitations to competitive tendering and the use of single-source procurement, such exceptions should be limited, pre-defined, and should require appropriate justification when employed, subject to adequate oversight taking into account the increased risk of corruption, including by foreign suppliers (OECD, 2015a). Unfortunately, corruption often arises in relation with the choice of the procurement procedure. Examples include a lack of proper justification of the use of non-competitive procedures or an abuse of non-competitive procedures on the basis of legal exceptions, through contract splitting, abuse of extreme urgency, or non-supported modifications.

The LAACSEC distinguishes three processes by which contracting authorities may acquire goods: public tenders, restricted invitation to at least three providers, and direct awards (with or without three quotes). The public procurement law specifies the maximum amounts permitted for direct awards and restricted invitations (Article 65). In 2012, the maximum amounts permitted for direct awards were reduced, which led to a significant increase of public tenders (from 3 tenders in 2010 to 309 tenders in 2016). In order to avoid a high number of exceptions (through contract splitting for instance), and potential corruption cases, the public procurement law also specifies that the amount of exemptions cannot exceed 30% of the authorised budget. In 2016, the amount of exemptions (direct awards and restricted invitations) to tenders has gone below the 30% limit, given that the value of exemptions as a percentage of non-tender proceedings represented 28% (45% in 2014). As specified above, Coahuila’s Transparency Law foresees the publication of the results of direct awards, restricted tenders, and any other procurement processes (Article 21), which are carried out by SEFIN. The law also lists the information that needs to be published in the case of public tenders and restricted tenders (the same information) and direct awards.

The reduction of the amounts allowed for a direct award in the framework of the 2012 law represents an important step forward for the fight against corruption in Coahuila. The state government should nevertheless continue maximising transparency in competitive tendering and should take precautionary measures to enhance integrity, in particular for exceptions to competitive tendering. SEFIR should make sure that all the contracting authorities publish the information requested by the Transparency Law (Article 21) and SEFIN should make sure that the list of exceptions it publishes on its website contains all the direct awards and restricted invitations. Coahuila should also continuously monitor the use of exceptions by verifying that the exceptions do not exceed 30% of the authorised budget of the contracting authorities and that contracting authorities prepare proper justifications for direct awards at state and municipal levels. The Superior Audit Office of Coahuila (Auditoría Superior del Estado de Coahuila, ASEC) has indeed indicated that decisions to use direct award processes are sometimes questionable at municipal level. SEFIR and SEFIN should also assess relevant data to identify possible corruption cases. The introduction of an e-procurement system and the collection of digital records through the new supplier’s registry REPROCO will certainly contribute to monitor the use of exceptions and to maximise transparency in competitive tendering.

Coahuila should consider the development of e-procurement solutions that cover the entire public procurement cycle in order to cut direct contact between public officials and suppliers and, therefore, decrease the risks of corrupt behaviour.

Transparency and integrity of public procurement systems can also be strengthened through e-procurement systems. The adoption of digital processes serves to enhance integrity of the public procurement system as face-to-face interactions between officials and potential suppliers and other opportunities for corruption are reduced through the centralised and automatic transfer of data between systems. E-procurement systems and tools can also strengthen transparency by making information available on public procurement processes. The OECD Recommendation also recommends that adherents improve public procurement systems by harnessing the use of digital technologies to support appropriate e-procurement innovation throughout the procurement cycle. Those technologies are powerful tools to ensure transparency and integrity, but also access to public tenders. According to the Recommendation, adherents should pursue state-of-the-art e-procurement tools that are modular, flexible, scalable, and secure in order to assure business continuity, privacy and integrity, provide fair treatment and protect sensitive data, while supplying the core capabilities and functions that allow business innovation. E-procurement tools should be simple to use, appropriate to their purpose, and consistent across procurement agencies, to the extent possible; excessively complicated systems could create implementation risks and challenges for new entrants or small and medium enterprises (OECD, 2015a).

Coahuila does not yet have an e-procurement system in place, but contracting authorities use the federal e-procurement system, CompraNet, in existence since 1997 (see Box 6.7). Even though all the public procurement processes involving federal budget must indeed use CompraNet, the physical presence of suppliers during purchasing processes is still required. According to the public procurement law (Article 43 of the LAACSEC), proposals can be delivered physically in a sealed envelope or, if permitted by the contracting authority (la convocante), proposals can be sent by mail, e-mail, or through e-procurement tools (provision introduced in the framework of the reform of 2012). According to the same law, the tender documents can be accessed online (Article 51). In practice, however, e-procurement systems (or electronic publication and submission) do not happen. Interviews during the fact-finding mission made clear that most of the public procurement processes are conducted face-to-face. In addition, bidders may be present when bids are opened (Article 57 of the LAACSEC). The way public procurement processes are conducted in Coahuila provides many opportunities for direct contact between public officials and suppliers and, as such, increases risks of corruption.

At the federal level, Mexico has implemented several good practices suggested by the 2015 OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement. Since 1997, Mexico (SFP) has been developing its e-procurement information system, CompraNet. Since June 2011, the registration of procedures and procurement documents on CompraNet has been mandatory for every governmental agency, at federal or state level, that uses the federal budget for its procurement procedures and that exceeds a value threshold of 300 days of minimum wage. CompraNet contains information from June 2010 about procurement procedures and leases and services. According to Article 2 of the Law on Acquisitions, Leasing and Services of the Public Sector (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Servicios del Sector Público, LAASSP), CompraNet provides the following information: the annual procurement programme, a supplier registry, a social witness registry, a list of sanctioned suppliers, the calls for tenders (and restricted invitations) and their modifications, records of clarification meetings, records of submissions and proposal openings, the social witness testimonials, data related to the contracts and addenda, direct awards, and resolutions and challenge instances. Its access is free. CompraNet also includes an online form that allows the general public to inform SFP of irregularities (Portal de quejas y denuncias).

Source: OECD (2013), Public Procurement Review of the Mexican Institute of Social Security: Enhancing Efficiency and Integrity for Better Health Care, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264197480-en.