Chapter 5. Enhance transparency and participation for effective accountability in Coahuila

The present chapter considers Coahuila’s transparency framework as well as mechanisms to engage stakeholders in developing and implementing public policies, and assesses the extent to which they promote integrity, accountability, and the public interest. On the one hand, this chapter acknowledges recent efforts which led to the establishment of a solid institutional and legal framework, but also underlines that the data and information created by public entities in Coahuila could lead to greater accountability through visualisation tools and the use of a single portal. On the other hand, this chapter analyses the extent to which existing mechanisms for stakeholder participation are used in practice, and proposes additional measures Coahuila could take to improve constructive dialogue and monitor public entities’ commitments to transparency.

Introduction

Open and transparent institutions are essential in ensuring accountability at all stages of public life. Disclosing information to the public and giving stakeholders the possibility to contribute to the decision-making processes does not only allow citizens to monitor the integrity of public institutions and deter corrupt behaviours by public officials, but also strengthens democratic processes and, eventually, improves trust in public institutions.

While a necessary condition, transparency is not enough to guarantee greater accountability, especially if it merely makes public a flow of complex information without a tool to understand it or a mechanism with which stakeholders could effectively engage with public institutions in shaping the public debate and the decision-making process. In this sense, a government may disclose significant volumes information and yet remain opaque, while other governments may publish a more limited set of information but be more accountable, because they provide tools to make the information accessible and encourage forms of stakeholder participation.

The idea that transparency and participation frameworks should be designed to promote accountability is also reflected in the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (OECD, 2017a), whereby states are recommended to encourage transparency and stakeholder engagement at all stages of the political process and policy cycle to promote accountability and the public interest. The present chapter assesses the framework and the activities undertaken in the latter context and, in particular, whether they effectively promote transparency and an open government, and whether they facilitate stakeholder access in the development and implementation of public policies.

Leveraging information and data for more accountable institutions

Over the last several years, Coahuila has built one of the most advanced transparency frameworks among Mexican states.

Through a series of reforms undertaken in recent years, Coahuila has developed one of the most advanced legal frameworks among Mexican states in transparency matters. In 2015, Coahuila was the first state to harmonise its legal framework with the General Transparency and Access to Information Law (Ley General de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información, or General Transparency Law), which, among other accomplishments, created the National Transparency System. Similarly to the National Anti-corruption System (see Chapter 1), the System aims to co-ordinate all institutions in Mexico to improve overall transparency in the country (Box 5.1).

The National Transparency System is the mechanism which will lead the co-ordination, collaboration, and promotion of the efforts among all the relevant institutions at the three levels of government and will eventually contribute to generating better quality, management, and processing of information. According to the General Transparency and Access to Information Law, this mechanism will facilitate the knowledge and assessment of public management, the access to public information, the dissemination of a culture of transparency and accessibility, and more effective audit and accountability.

According to this law, the National Transparency System consists of the following institutions:

-

National Institute for Transparency and Access to Information (Instituto Nacional de Transparencia, Acceso a la Información y Protección de Datos Personales, INAI), which leads and co-ordinates the system

-

the entities in charge of guaranteeing access to information and personal data protection at the state-level (including ICAI)

-

the Superior Audit Institution (Auditoría Superior de la Federación, ASF)

-

the General National Archive (Archivo General de la Nación)

-

the National Institute for Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI)

For the state of Coahuila, ICAI is the representative in the National Transparency System and takes also part in the North regional group of the system together with the states of Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, Durango, Nuevo León, Sinaloa, Sonora, and Tamaulipas.

Source: General Transparency and Access to Information Law (Ley General de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública), http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGTAIP.pdf.

The drive for transparency in Coahuila is led by the Institute for Access to Public Information of Coahuila (Instituto Coahuilense de Acceso a la Información Pública, or ICAI), which is the state entity empowered by the Constitution of Coahuila (the Constitution) to guarantee the fundamental right of all citizens to share, investigate, and request public information (Article 7). In particular, the Constitution gives ICAI the leadership in the following areas:

-

access to public information

-

culture of transparency

-

personal data

-

elaborating statistics, polls, surveys, and any other public opinion instrument

ICAI, which was created in 2004, is given political, legal, administrative, budgetary, and financial autonomy. Its members are appointed by Coahuila’s Congress through a majority vote (at least two-thirds of the assembly) pursuant to Coahuila’s Access to Information Law (Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública y Protección de Datos Personales para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, or Transparency Law - lastly reformed in March 2016), which also spells out its activities as well as the transparency obligations for all state entities. An Internal Regulation (Reglamento Interior) regulates ICAI’s internal organisation and functioning.

The current Transparency Law obliges public entities to make public more than 70 sets of information concerning the organisation, their relationship with other actors, and the legal framework (Articles 21-22; 25-28; 30-38; and 43-47). It also provides for a comprehensive mechanism to access information with the following features:

-

no subjective limitation on those who can request information

-

all state branches of government, entities, and municipalities are subject to the law

-

exceptions to the rights to access to information include:

-

personal data

-

public order, crimes prosecution

-

where there is a risk to the health or security of citizens

-

when tax collection is impeded.

-

-

exceptions apply only to those parts of requested information/document related to the latter grounds of refusal

-

requests can be anonymous, oral, or written

-

costs may be incurred when the requested document exceeds 20 pages

-

the ICAI may be challenegd in cases of request denial or neglect

The advanced level of Coahuila’s legal framework is confirmed by several national rankings, which regularly assess different aspects of Mexican states’ attitude toward transparency and which place Coahuila among the best Mexican states based on several indicators (Table 5.1).

Given that Coahuila is currently developing policies on open government, it could better exploit the data and information currently produced by public entities by improving data socialisation and developing online visualisation tools.

A relatively recent trend undertaken by many countries to increase transparency and accountability of public institutions is to make their data available to the public and allow the use, reuse, and free distribution of datasets through the so-called open data format. The OECD has been analysing such an increasingly relevant phenomenon and has identified the potentials of the extraordinary quantity of data collected by governments, which can increase transparency and awareness but also improve performance, encourage public participation, and improve the decision making of governments and individuals (Ubaldi, 2013).

In 2013, G8 countries adopted an Open Data Charter, which represented the first international instrument designed to guide the implementation of open government data strategies. The Charter laid out five principles (G8, 2013):

-

Open data by default;

-

Optimised quality and quantity of data;

-

Data should be usable by all;

-

Releasing data for improved governance; and

-

Releasing data for innovation.

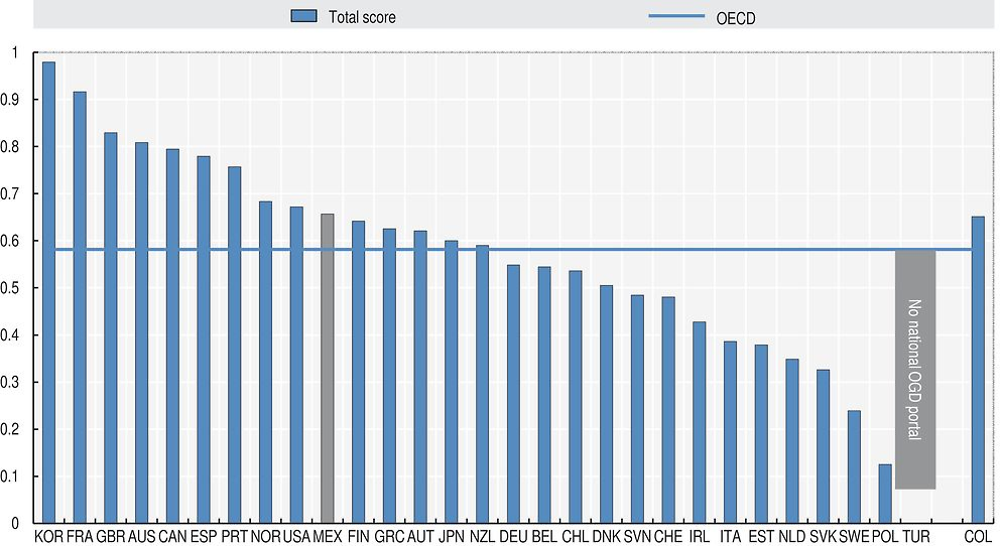

The OECD has elaborated a pilot Index on Open Government Data (OECD OURdata Index) which assesses governments’ efforts to implement open data in three dimensions based on its methodology and structured around the following principles of the G7 Open Data Charter: 1) Data availability on the national portal; 2) Data accessibility on the national portal; and 3) governments’ support to innovative re-use and stakeholder engagement. As shown in Figure 5.1, Mexico scores above the OECD average.

← 1. Data for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, and Luxembourg are not available.

Source: OECD (2015), Government at a Glance 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-en.

The OECD OURdata Index assesses governments’ efforts to implement open data in the three critical areas: openness, usefulness, and re-usability of government data. Data for the index is taken from member countries and focuses on government efforts to ensure public sector data availability and accessibility and to spur greater re-use. The Index is based on OECD methodology and the guidelines of the G8 Open Data Charter. Figure 5.1 illustrates a composite index where 0 is lowest and 1 highest.

Countries have become increasingly aware of the potential of open data to enhance integrity and tackle corruption. In particular, the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (OECD, 2017a) calls states to encourage transparency and stakeholders’ engagement “promoting transparency and an open government, including ensuring access to information and open data, along with timely responses to requests for information.” In 2015, the G20 adopted six Anti-corruption Open Data Principles that identify open data as a tool to prevent and tackle corruption insofar as they shed light on government activities, decisions, and expenditures. In addition, they increase accountability and allow citizens and government to better monitor the flow and use of public money within and across borders (Box 5.2).

Principle 1: Open Data by default

Access to information has been widely accepted as a tool to increase transparency and fight corruption. Open data by default goes a step beyond transparency, as it promotes the provision of reusable data from its source, without requiring requests for information and increasing access in equal terms for everyone; while at the same time, assuring the necessary protection to personal data in accordance to laws and regulations already established in G20 countries.

Principle 2: Timely and comprehensive

Releasing comprehensive data sets - which are accurate, timely and up to date, published at a disaggregated level, adequately documented, and following internationally agreed upon standards, metadata and classifiers - is crucial to increase data use for anti-corruption means. Such data openness will allow a better understanding of government processes and policy outcomes in as close to real-time as possible.

Principle 3: Accessible and usable

Lowering unnecessary entry barriers, and by publishing data on single window solutions such as central open data portals increases the value of data, as more citizens and organisations are able to find and use it to reduce opacity in government institutions.

Principle 4: Comparable and interoperable

Enabling the comparison and traceability of data from numerous anti-corruption-related sectors increases its potential to inform decisions and feedback between decision-makers and citizens.

Principle 5: For improved governance and citizen engagement

Open data empowers citizens and enables them to hold government institutions into account. Open data can also help them understand, influence and participate directly in the decision-making processes and in the development of public policies in support of public sector integrity. This is paramount to build trust and strengthen collaboration between governments and all sectors of society.

Principle 6: For inclusive development and innovation

Open data, through reinforced transparency and integrity, can promote greater social and economic benefits by providing actionable information to build effective, accountable, and responsive institutions; this alone can increase economic output and efficiency in government operations. Furthermore, while preventing corruption, open data facilitates the development of new insights, business models and digital innovation strategies at a global scale.

Source: G20 (2015), G20 Anti-Corruption Open Data Principles.

Open government is an emerging theme in Coahuila’s political agenda and its institutions are producing an increasing amount of open data. This is reflected in Coahuila’s Transparency Law, which requires public entities to publish the information available to the public as open data and provides for specific open government obligations to increase citizen participation, transparency, and improve accountability (Article 50). Furthermore, it envisages the creation of an Open Government Secretariat in charge of promoting best practices for citizen participation, co-operating in the implementation and the evaluation of Coahuila’s digital policy in the realm of open data, and elaborating specific indicators on relevant themes. The Secretariat (Secretariado Técnico Tripartita Local de Gobierno Abierto) was created in 2015 and comprises the President of ICAI, the Minister of SEFIR, and a co-ordinator representing the civil society contact points of the five regions of the state. In August 2016, after a broad public consultation process involving all of the state’s regions, the STGA presented an open government action plan (Plan de acción de Gobierno Abierto para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza 2016-2017) which set a number of commitments and a detailed timetable on the identified deliverables (STGA, 2016).

In spite of the remarkable efforts displayed so far by Coahuila in setting up the adequate legal framework and requiring public institutions to publish a significant amount of data and information, interviews during the fact-finding mission in July 2016 suggested that their actual use is limited. Despite the stated goal of the open data initiative, citizens are not the prime users of existing transparency mechanisms. This state of affairs raises doubts about the data’s effectiveness for accountability. In order to make the best out of data that are being created by public entities and elevate the experience of Coahuila as a best practice at the international level, Coahuila should not only create databases presenting data in disaggregated formats for technical analysis and evaluation as laid out in the principles of G8 Open Data Charter, but it could also make data more intelligible by presenting them in a plain, aggregated, and simplified format. Data visualisation does not only help to make public information more comprehensible, but it also stimulates the public interest in areas not commonly accessible to the public (HATVP, 2016).

In practice, in order to improve data socialisation and develop online visualisation tools, Coahuila could consider the open data projects and portals developed in other OECD countries, such the one set up by the city of Montreal in Canada (Box 5.3) to consult all of its contracts (Vue sur les contrats) as well as the ones created by the Italian government to access and monitor data on public spending data (SoldiPubblici), infrastructure projects (Opencantieri) and the 2015 Universal Exposition of Milan (Box 5.4). The latter examples could also be taken into consideration to improve existing efforts to make open data user and citizen-friendly, such as the SITODEM Portal (Sistema de Información y Transparencia de Obras para el Desarrollo Metropolitano; [http://sitodem.sefircoahuila.gob.mx/]), which presents a number of useful information items linked to the Integral System of Public Investment including the names of approved public works, their cost, the amount already spent, the responsible departments, beneficiaries and auditors. This portal, however, does not ensure that this information is made available in real time and does not provide an user-friendly visualisation of the evolution of projects and related contracts (see also Chapter 6).

Following a series of corruption scandals at the beginning of the 2010s, the city of Montreal identified transparency as crucial element in its efforts to improve integrity and become a “smart city”. In June 2015 it therefore launched the platform “View on the Contracts” (Vue sur les contrats), which makes available for public consultation contracts signed by the city. The contracts may be visualised in an intuitive way according to several criteria including dates, amount, typologies, authorising entity, area, and keyword. In this way, the platform does not only provide easily-understandable information for the average user, but it also represents a portal for more expert users to analyse and use the specific data in greater detail.

Source: HATVP (2016); Website of the city of Montreal, https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/vuesurlescontrats/,.

SoldiPubblici

The SoldiPubblici initiative provides open data and data visualisation tools on public spending at all levels of government in order to enhance transparency, improve participation, and provide comparable data to administrators. The corresponding website (http://soldipubblici.gov.it/it/home) includes an interactive visualisation tool allowing users to search and compare public spending data by geographical area and institution.

Opencantieri

Opencantieri is a project managed by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transportation (Ministero delle infrastrutture e dei trasporti, or MIT) to provide open, complete, and updated information on ongoing public infrastructure projects. The platform website contains the available data and provides syntheses as well as specific insights on issues such as financing, costs, timing, and delays. All the information is publicly accessible and can be downloaded through the MIT’s open data website.

OpenExpo

OpenExpo was the portal set up for the 2015 Universal Exposition of Milan. It deals with several data and transparency issues including the following sections:

-

Why OpenExpo

-

Expo Barometro

-

Open Data

-

Expo2015 Works

-

reporting

-

transparent administration

-

Visit Expo

-

use cases

The Open Data section, in particular, contains all data related to the exhibition. Datasets can be searched for using a search engine that filters data, or by browsing datasets per description tag. The licence used is Creative Commons - Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). The website provides exhaustive information on the format of the data and contains a section with examples of reuse of OpenExpo datasets (available in Italian only).

Source: Soldipubblici’s website: http://soldipubblici.gov.it/it/home; Opencantieri’s website, http://opencantieri.mit.gov.it/; OpenExpo’s website, http://dati.openexpo2015.it/en.

In developing data visualisation tools, Coahuila should take into consideration the different levels of digital literacy across the state. The latter emerged as a significant challenge during fact-finding interviews, especially in rural areas. In consequence, tools to make information and data more friendly and understandable could be coupled with awareness-raising and capacity-building initiatives to narrow the digital divide and achieve the effective use of open data in line with the G20 Anti-Corruption Open Data Principles (Box 5.2).

In order to avoid gaps or overlaps and allow citizens and civil society to have comprehensive access to all the information and data provided by public institutions, Coahuila may wish to identify a single portal to consult and request information.

The potential of transparency as a tool to increase accountability also depends on the accessibility of the information, i.e. on how easily citizens can obtain the desired information. If, for instance, an institution discloses a significant amount information but it is not clear where it is published or how to consult a certain database, the usefulness of transparency as an accountability tool is diminished. This issue is also stressed by the G20, which acknowledges the importance of making open data “easily discoverable and accessible” and invites states to publish open data on “central portals, or in ways that can increase its accessibility, so that it can be easily discoverable and accessible for users” (G20, 2015).

In Coahuila, the significant amount of information produced by public entities can be consulted or requested through several websites:

-

Coahuila Transparente (www.coahuilatransparente.gob.mx/), which centralises all the information to be published by public entities

-

ICAI’s website (www.icai.org.mx:8282/ipo/), which provides links to the websites of public with the information to be disclosed according to the law as well as the link to the portal to request information

-

Infomex Coahuila (www.infocoahuila.org.mx/), the website used to submit a request for information

-

Coahuila Todo Transparente (www.coahuilatodotransparente.gob.mx/), Coahuila’s open data portal

-

SEFIR’s website (www.sefircoahuila.gob.mx/), which also seems to function as a “database of databases” insofar as it displays the link to SITODEM, and to other databases such as the ones on public officials’ asset declarations and state budget reports.

The simultaneous existence of several platforms to access information in Coahuila does not allow potential users to unambiguously identify the main source of information in Coahuila, and this may deter them from looking into information. This is confirmed by the relatively low score of Coahuila in the Transparency Portal Indicator developed by CIDE (Table 5.1). In order to encourage people in accessing and using public information and data, Coahuila could consider using one single portal, as suggested in Chapter 6 in relation to public procurement. This would not only enable better understanding and communicability on the entry point to access all available information, but it could also allow institutions to focus their efforts on one single portal, thereby minimising the risks of gaps and overlaps, as well as saving resources needed to keep updated and relevant multiple databases and information at the same time. In designing a single and comprehensive database containing the latter features, Coahuila may consider the model adopted by Spain, which provides a comprehensive and user-friendly transparency portal with high level of usability and reusability of information in co-ordination with the Spanish central open data portal (www.datos.gob.es) (Box 5.5).

The Transparency Portal (Portal de la Transparencia) set up by the government of Spain is organised around four main components, namely:

-

categories, where information is organised around four categories (Institutional data; Regulations; Budgeting, monitoring and reporting; Contracts, agreements and grants) and a number of sub-categories (e.g. remuneration of senior officials and authorisations provided to civil servants to exercise private activity after leaving senior public positions; planning and execution and audit reports; bills, laws, and regulations; data on public procurement; grants to political parties; subsidies and public properties)

-

ministries

-

right to access information, where users can submit a request, consult the status of requests, as well as receive information about statistics or how to use such tool

-

open government and citizen participation, which provides information and relevant link to access open government data and tools for participation

In addition, the portal includes sections providing a comprehensive picture of information and data in Spain, including one on Spanish regions (Comunidades Autónomas) with a list of links to relevant databases, laws, and institutions for each region, as well as one on public institutions (Instituciones públicas) where one may find links to the transparency pages of institutions that are not part of the executive, such as the parliament and national courts pages.

Source: Spain Transparency Portal, http://transparencia.gob.es/.

Improving stakeholders’ engagement to promote transparency and the public interest

Although the legal framework of Coahuila offers tools for stakeholder participation and oversight, they have not been regularly used in the past. In order to improve their effectiveness, mechanisms could be introduced to improve awareness and enable active engagement in innovative and interactive ways.

Transparency, while a necessary condition, does not in itself guarantee oversight and effective citizen engagement. Public officials and institutions are accountable to the public not only when their activities and information are made available for public scrutiny, but also when citizens and stakeholders are able to participate in public life and actively contribute to the decision-making process.

Building on country experiences and practices, the OECD found that civic engagement enhances a government’s policy performance by working with citizens, civil society organisations, businesses, and other stakeholders to deliver improvements in policy and the quality of public services (Box 5.6). More important for the present review, stakeholders’ engagement is a meaningful tool to enable public integrity and effective accountability as stressed by the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, which calls upon states to grant “all stakeholders – including the private sector, civil society and individuals – access in the development and implementation of public policies” (OECD, 2017a). As stressed in Chapter 1, stakeholder engagement is also crucial to embrace a whole-of-society approach to public integrity, and therefore specific forms of participation should be designed to engage them in the development, regular update, and implementation of the public integrity system.

The experience of OECD member countries indicates open and inclusive policy making can help governments better understand and respond to the changing needs of society, use ideas and resources from civil society and business to confront complex policy challenges, lower costs and improve policy outcomes, and reduce administrative burdens on policy implementation and service delivery.

As such, the OECD has created a set of guiding principles designed to help governments strengthen open and inclusive policy making as a means to improve their policy performance and service delivery. A summary of the principles is provided here:

-

Commitment: leadership and strong commitment to open and inclusive policy making is needed at all levels – politicians, senior managers, and public officials.

-

Rights: citizens’ rights to information, consultation and participation in policy must be grounded in law. Government obligations to respond to citizens must be clearly stated. Independent oversight arrangements are essential to enforcing these rights.

-

Clarity: objectives for and limits to information, consultation, and participation should be well clarified. The roles and responsibilities of all parties must be clear. Government information should be complete, objective, reliable, relevant, and easy to find and understand.

-

Time: public engagement should be undertaken as early in the policy process as possible and adequate time must be available for consultation and participation to be effective.

-

Inclusion: citizens should have equal opportunities and channels to access information, be consulted and participate. Every reasonable effort should be made to engage with as wide a variety of people as possible.

-

Resources: adequate financial, human and technical resources for effective public information, consultation and participation. Government officials must have access to appropriate skills, guidance and training, as well as an organisational culture that supports both traditional and online tools.

-

Co-ordination: initiatives to inform, consult and engage civil society should be co-ordinated within and across levels of government to ensure policy coherence, avoid duplication, and reduce the risk of “consultation fatigue.”

-

Accountability: governments have an obligation to inform participants how they use inputs received through public consultation and participation.

-

Evaluation: governments need to evaluate their own performance. To do so effectively will require efforts to build the demand, capacity, culture, and tools for evaluating public participation.

-

Active citizenship: societies benefit from dynamic civil society and governments can facilitate access to information, encourage participation, raise awareness, strengthen citizens’ civic education and skills, as well as support capacity-building among civil society organisations. Governments need to explore new roles to effectively support autonomous problem-solving by citizens, CSOs, and businesses.

In increasing citizen engagement in policy making, public officials must be careful to ensure that engagement processes are fit for purpose and protect against potential conflict of interests and policy capture (OECD 2014). The type and level of engagement used for a particular matter should reflect the intended purpose of that engagement. The nature of the legislative scheme and the regulatory style adopted will affect the nature of any engagement. For example, advisory bodies can be effective in providing insights from industry or the community as to how to most effectively change behaviour or anticipate developments which may warrant a change (OECD, 2009). Whatever style of engagement is chosen, opportunities to increase dialogue and exchange information in order to ensure informed decision making and confidence in the system should be maximised.

Engagement must not be used as a tool to favour certain particular interests, as this would compromise the regulators’ ability to achieve broader outcomes (OECD, 2014). Instead, engagement must be inclusive (unless this would compromise the intended outcome) and transparent. Inclusive consultation allows any interested stakeholder to contribute or comment on proposals, rather than just representative groups, building confidence that all interests are heard. Similarly, transparent engagement involves publicly documenting who has been consulted and what their input has been and the release of the policy maker’s responses to the main issues. This can protect the regulator from suggestions of capture or failure to listen to the range of views, and also builds confidence in the regulatory process.

Sources: OECD (2017b), OECD Integrity Scan of Kazakhstan: Preventing Corruption for a Competitive Economy, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272880-en; OECD (2009), Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264048874-en; OECD (2014a), The Governance of Regulators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209015-en.

Coahuila adopted a specific Law on Civic Participation in 2001 (Ley de Participación Ciudadana para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza), which aims to support Coahuila’s citizens’ right to participate in public life and to promote policies for community development. In this sense, it provides for a number of different tools for civic participation and consultation (Articles 4-5), namely:

-

plebiscite (plebiscito)

-

referendum (referendo)

-

popular initiative (iniciativa popular)

-

popular consultation (consulta popular)

-

community collaboration (colaboración comunitaria)

-

public hearing (audiencia pública)

-

citizen Participation Councils (Consejos de Participación Ciudadana)

-

community Participation Councils (Consejos de Participación Comunitaria)

In practice, the latter tools are only used rarely, as evidenced by Montemayor (2016) who, after presenting requests to information to all relevant institutions in Coahuila, found that in the last years 149 public hearings have been organised (2004-2016), while 12 legislative proposals were presented in front of the Congress (2004-2015) and 7 to the Executive (2012-2016, out of 181). On the other hand, various initiatives have been taken by institutions in Coahuila to engage citizens, youth, universities and NGOs, mostly consisting of monitoring or social audit activities (Table 5.2).

Although the latter initiatives reveal significant efforts to stimulate stakeholder oversight in public life, the minimal use of institutional tools for civic participation clearly points to a low level of citizen participation in the public life of Coahuila, which in turn signals the scarce use of stakeholder engagement mechanisms to encourage accountability. Considering the increasing use of web portals to consult and access information (Figure 5.2), Coahuila could consider leveraging ICTs to promote the engagement of society as done by Colombia (Box 5.7), as well as improving the understanding of available tools by devoting a specific section of its future single portal to explain and describe them following the example provided by Spain (Box 5.8).

Source: Montemayor (2016) and SEFIR.

Crystal Urn (Urna de Cristal) is the Colombian government’s leading initiative of electronic citizen participation and government transparency strategy. Since its launch in October 2010, Urna de Cristal has consolidated a multi-channel platform, which integrated traditional communication channels such as radio and television with digital channels such as social media, SMS, and web sites. Through these channels, Colombians can learn about government results, progress and initiatives, address their concerns directly with the government bodies, and participate and interact on subjects of state administration and public services and policies, thus creating a binding relationship between citizens and a state truly committed to service. More than three million Colombians have visited the Urna de Cristal website to access government information and to get involved in one of the 28 participation exercises or the more than 300 awareness campaigns carried out in 2014. More than 50 000 questions were raised by Colombians in 2014. The Urna de Cristal team is in charge together with the Online Government strategy team and the ICT Ministry of the initiative rollout and operation.

Source: OECD (2013), Colombia: Implementing Good Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264202177-en, and www.oecd.org/gov/colombia-urna-cristal.pdf.

Most ministries in Spain provide for a channel for citizens to participate in their decision-making processes. The objective of these mechanisms is to gather the views of citizens and stakeholders before the elaboration of a legal instrument and to receive opinions on drafts under discussion from those who are directly involved. As a consequence, two procedures for stakeholders to participate are envisaged:

-

preliminary public consultation (consulta pública previa), which concerns opinions from citizens, organisations, and associations before the elaboration of a draft instrument

-

public hearing and information (audiencia e información pública), which allows those citizens (or representative organisations) having a legitimate interest or whose rights are affected by a draft instrument under discussion to provide views and improve the text

Although the list of instruments which are subject to the latter procedures are available on the ministry websites, Spain’s Transparency Portal provides for a clearly identifiable section on Civic Participation presenting the available tools and containing links to the relevant ministry pages.

Source: Spain Transparency Portal, Civic Participation Section: http://transparencia.gob.es/transparencia/transparencia_Home/index/GobiernoParticipacion/ParticipacionCiudadana/ParticipacionProyectosNormativos.html; Law 39/2015 and Law 50/1997.

Coahuila could make its transparency framework more responsive to society by introducing mechanisms to improve stakeholder engagement through a demand-drive approach based on dialogue, consultation, and on data collaboration and interoperability.

The institutional and legal framework of Coahuila on transparency has evolved significantly in the last years, creating the basis for a transparent public system. However, the typologies of relevant information and the usability and availability of data change over time according to the evolving socio-economic context and technological developments. Furthermore, public institutions are not always aware of which data interests the public, nor how such data could be used for the public interest. In consequence, the significance of transparency frameworks and platforms depends very much on their dynamism and capacity to evolve along technology developments and social needs.

Institutions in Coahuila are well aware of the need to keep the legal framework up-to-date: indeed, the Transparency Law, first enacted in 2003, has been amended several times since (in 2008, 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2016). Over these years, for instance, the categories of general information to be disclosed by all public entities increased from 19 to 101 (Montemayor, 2016). Similarly, some websites and portals have created sections to receive comments or make proposals, as it is the case for ICAI’s website forum (Foro) and the section “Citizen Observer” in the “Coahuilatodotrasparente” portal. However, the former contains only a few outdated comments and the latter only presents pictures and videos uploaded by users with comments describing misconduct by public authorities or problems in public buildings.

Considering the importance in involving stakeholders in determining the most relevant and priority data for the promotion of public integrity (HATVP, 2016), Coahuila could introduce further mechanisms to allow stakeholders to contribute effectively in building a dynamic transparency framework and environment. On the one hand, relevant institutions and social actors could gather periodically to identify typologies of information which could potentially enhance the transparency and accountability of public institutions. Considering the inclusiveness and diversity of actors represented in the Open Government Secretariat, this could take place in such context. After that, ICAI – which has the legal mandate to submit legislative proposals in the realm of transparency pursuant to Article 59(7) of the Constitution of Coahuila – could submit a draft to the Congress of Coahuila to amend or introduce obligations set by the existing legal framework. On the other hand, Coahuila could consider creating a simple and user-friendly platform to submit ideas on transparency as done in Colombia, and could take better advantage of its open data platform, allowing users to enrich it with new datasets following the examples of France and Finland (Box 5.9). In order to encourage data co-creation and collaboration as well as to enable data re-use that produces value (Ubaldi, 2013), Coahuila should also ensure the availability, quality, and interoperability of public datasets, the latter being essential prerequisites for open data to “play a key role to dismantle corruption networks” (Open Data Charter, 2016).

Colombia

The Transparency Council of Colombia developed a platform called “Ideas.Info: Tus ideas en Transparencia” to improve citizen participation in public affairs through visions and ideas, as well as to facilitate each person’s right to present a request to public authorities. For this purpose, citizens are invited to propose ideas – in the form of good practices or legislative improvements – concerning the scope of action of the Transparency Council and issues of general public interest. If accepted, petitions become public, where they can be openly discussed and supported by other users. Once the petition obtains 1 000 supporters, the Transparency Council’s Director General will issue an official opinion on the corresponding subject matter.

France

The French national open data portal enables data prosumers to add new datasets to the portal directly. In order to publish open data (datasets, APIs, etc.), data contributors are requested to fill out an online form which collects information related to data licensing, granularity, and a description of the overall data content, among others. The French open data portal also enables data prosumers to publish and showcase examples of open data reuse (OGD or not) and to monitor the use of the datasets they publish. In addition, the French government used the portal to launch the Base Adresse Nationale project, which is a multi-stakeholder collaboration initiative aiming to crowdsource a unique national address database fed by the data contributions from private, public, and non-profit organisations.

Finland

In Finland, the national open data portal has been enabled as a platform where citizens can publish open data and interoperability tools (i.e. guidelines to ease the interaction between user datasets and other data formats or platforms). Users are required to register on the portal in order to publish datasets. As in France, uploading open data on the Finnish portal requires filling in an online form where users can provide a detailed description of the data. This description includes, for instance, information on the data’s licensing model (i.e. Creative Commons) and the data validity timeframe. Users can also browse the profiles of other users using the portal and can explore their activity and the datasets they have published. The portal also provides users with the possibility of subscribing to specific organisations in order to receive updates on new datasets, comments, etc.

Sources: “Ideas.Info” Portal, www.ideasinfo.cl/Peticion/Inicio.aspx; OECD (2016), Open Government Data Review of Mexico: Data Reuse for Public Sector Impact and Innovation, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264259270-en; www.data.gouv.fr/fr; www.avoindata.fi.

Coahuila could improve oversight over the transparency commitments of its institutions by developing an easily accessible index measuring compliance and implementation of state- and municipal-level institutions.

Stakeholders’ engagement to improve transparency and the public interest does not only take place through direct consultative processes and mechanisms, but can also be exercised by means of public mechanisms that help to oversee and monitor public institutions’ commitment to openness and transparency. The value of developing benchmarks and indicators on the level of implementation, as stressed by the OECD Recommendation (OECD, 2017a) in relation to public integrity systems, can be transferred to the realm of transparency, where the frequent updates and developments highlighted in the previous section require a responsive approach from public entities.

A useful tool which could be deployed by Coahuila to favour stakeholder monitoring is to introduce a transparency index providing easily accessible evidence and visualisation of improvements made in implementing the relevant framework and, at the same time, point out good practices as well as weak areas and institutions where further efforts are most needed. This could be particularly effective in the Mexican context, where rankings receive high visibility and therefore provide incentives to administrators to improve over the years. On the other hand, considering the legalist approach which often emerged during the fact-finding mission’s interviews, such an index should be carefully designed in order not to lead to a formal “check-the-box” activity disregarding the level of actual implementation and creating a mere compliance exercise.

In Coahuila, ICAI is in charge of measuring compliance of public entities with transparency obligations and making public the corresponding results pursuant to Articles 18 and 34(7) of the Transparency Law. Although ICAI carries out such task on a trimestral basis, accessing the corresponding results is not straightforward as one may find them only after searching the subfolders of ICAI’s transparency obligations page (información pública de oficio) [www.icai.org.mx/]. Furthermore, such information is provided through power point presentations without any possibility to use data or to do customised comparison between institutions and across time. Coahuila could therefore leverage the data which are already being collected and improve their socialization by creating a transparency index, which should be made widely public and easily accessible to the public. Furthermore, it should provide visualisation tools and customisation options as well as include indicators not only related to compliance with the Transparency Law but also its implementation and effectiveness. In this context, Coahuila could consider the example provided by Transparency International Slovakia, which regularly develops Open Local Government indexes (Otvorená samospráva) assessing the level of transparency in Slovakian regions and municipalities. Although the latter consider transparency in a broad sense, they represent a valuable reference for Coahuila in so far as they deal with subnational entities (including municipalities), they consider several indicators and provide graphs and visualisation tools to understand, assess, and compare scores in a clear, customisable and interactive way (Box 5.10).

The Open Local Government Indexes are developed by the Transparency International Slovakia (TIS) to assess the level of transparency in the 8 regions and 100 largest municipalities of Slovakia by giving a grade (from A+ to F) and creating rankings, which can also be customized by users. In particular, the two most recent rankings assess the several policy areas using a number of different sources.

Proposals for Action

The advanced transparency framework built over the last years has created the premises for an open public sector in Coahuila. In order to leverage such efforts towards effective accountability, the OECD recommends that Coahuila considers taking the following actions in the realm of transparency and stakeholder participation:

Leveraging information and data for more accountable institutions

-

Given that Coahuila is currently developing policies on open government, it could better exploit the data and information currently produced by public entities by improving data socialisation and developing online visualisation tools.

-

In order to avoid gaps or overlaps and allow citizens and civil society to have comprehensive access to all the information and data provided by public institutions, Coahuila may wish to identify a single portal to consult and request information.

Improving stakeholders’ engagement to promote transparency and the public interest

-

Although the legal framework of Coahuila offers tools for stakeholder participation and oversight, they have not been regularly used in the past. In order to improve their effectiveness, mechanisms could be introduced to improve awareness and enable active engagement in innovative and interactive ways.

-

Coahuila could make its transparency framework more responsive to society by introducing mechanisms to improve stakeholder engagement through a demand-drive approach based on dialogue, consultation, and on data collaboration and interoperability.

-

Coahuila could improve oversight over the transparency commitments of its institutions by developing an easily accessible index measuring compliance and implementation of state- and municipal-level institutions.

References

G20 (2015), G20 Anti-Corruption Open Data Principles, www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/G20/G20-Anti-Corruption%20Open%20Data%20Principles.pdf;jsessionid=6AF3453E46D22ADABE482CC578BAB798.1_cid334?__blob=publicationFile&v=1.

G8 (2013), G8 Open Data Charter and Technical Annex, www.gov.uk/government/publications/open-data-charter/g8-open-data-charter-and-technical-annex.

HATVP (2016), “Open Data & Intégrité Publique. Les Technologies Numériques au Service d’une Démocratie Exemplaire”, www.hatvp.fr/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Open-data-integrite-publique.pdf.

Montemayor (2016), La Política de Transparencia y Gobierno Abierto para impulsar la Participación Ciudadana y desarrollar la Gobernanza en el estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, Master Thesis, University of Vigo.

OECD (2009), Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264048874-en.

OECD (2013), Colombia: Implementing Good Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264202177-en. www.oecd.org/gov/colombia-urna-cristal.pdf.

OECD (2015), Government at a Glance 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-en.

OECD (2016), Open Government Data Review of Mexico: Data Reuse for Public Sector Impact and Innovation, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264259270-en.

OECD (2017a), Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf

OECD (2017b), OECD Integrity Scan of Kazakhstan: Preventing Corruption for a Competitive Economy, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272880-en.

OECD (2014), The Governance of Regulators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209015-en.

Open Data Charter (2016), Anticorruption Open Data Package (Public Draft Open for Comments Version), http://opendatacharter.net/resource/anticorruption-open-data-package/.

STGA (2016), Plan de acción de Gobierno Abierto para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza 2016-2017, www.resi.org.mx/icainew_f/images/MICROSITIO%20GA/2016/docs/PAL.pdf.

Ubaldi (2013), “Open Government Data: Towards Empirical Analysis of Open Government Data Initiatives”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en.