Chapter 2. Building a culture of integrity in the public sector in Coahuila

This chapter discusses ways to strengthen public ethics and the identification and management of conflict-of-interest situations in Coahuila through improvements in the institutional design, guidance, and control. First, the chapter discusses the legal and policy framework for public ethics and conflict-of-interest management. Second, it analyses potential reforms that would harmonise policies and practices, streamline public ethics in the whole-of-government, and raise awareness among public servants. Third, it assesses the effectiveness of the asset disclosure system of Coahuila in its attempts to prevent corruption. Finally, it provides guidance on evaluation and monitoring mechanisms.

Introduction

Integrity in the public sector is an important condition for the effective functioning of the state, for ensuring public trust in government, and for creating conditions for sustainable social and economic development. Public integrity “refers to the consistent alignment of, and adherence to, shared values, principles, and norms for upholding and prioritising the public interest in the public sector” (OECD, 2017a).

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity (2017a) acknowledges the critical role of ethical principles and values within the integrity system and provides guidance to decision makers and public officials on embedding high standards of conduct for cleaner public administration.

Creating a culture of integrity in the public sector goes beyond laws and regulations. Public servants need to be guided towards integrity through other instruments and processes through which ethical norms and public service values are adopted. In this way, a common understanding is developed of what kind of behaviour public employees should observe in their daily tasks, especially when faced with ethical dilemmas or conflict-of-interest situations which every public official will encounter at some point in his career.

The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017a) breaks down the process of building a culture of integrity in the public sector to the following key elements: setting clear integrity standards and procedures, investing in integrity leadership, promoting a professional public sector that is dedicated to the public interest, communicating and raising awareness of the standards and values, and ensuring an open organisational culture and clear and transparent sanctions in cases of misconduct.

In addition, integrity measures are likely to be most effective when they are integrated, or mainstreamed, into general public management policies and practices, especially human resource management and internal control, and when they are supported by sufficient organisational, financial, and personal resources and capacities.

This chapter examines the framework for public ethics and management of conflict of interest in Coahuila. The assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the current framework comes at a crucial point, given the adoption of the Local Anti-Corruption System (Sistema Estatal Anticorrupción) and necessary harmonisation of the state legislation with federal laws. This is a unique opportunity to adopt good practices regarding public integrity.

Building a legal and policy framework for public ethics and conflict of interest to ensure coherence throughout the administration

Following the model of the federal government, Coahuila could establish an Ethics Unit within SEFIR to harmonise existing policies across the administration. The Ethics Unit should have a counselling and guidance role.

On the federal level, a Unit specialised in Ethics and Prevention of Conflict of Interest (Unidad Especializada en Ética y Prevención de Conflictos de Interés, UEEPCI) was established within the internal structure of the Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de la Función Pública, SFP) to lead the development of integrity policies, co-ordinate with the other entities to implement the policies effectively, and evaluate them. SEFIR could replicate this model and create such a unit (UEEPCI) within SEFIR with a similar mandate.

However, in contrast to the role of the Ethics Unit at the federal level, the role of the UEEPCI within SEFIR should be purely preventive and not process any integrity violations. This means that the UEEPCI would be tasked with ensuring the implementation of integrity policies and creating a culture of integrity where ethical dilemmas, public integrity concerns, and errors can be discussed freely, and where doubts can be raised concerning potential conflict-of-interest situations and how to deal with them. Their responsibilities should nevertheless be clearly separated from the enforcement function fulfilled by the internal control offices in order to encourage public officials to seek advice without fearing negative consequences and sanctions. The clear distinction between prevention and enforcement would allow the UEEPCI to acquire a separate identity and visibility, independent from the repressive paradigm which is common of legalistic systems like Mexico where the emphasis tends to be on enforcement of integrity and anti-corruption rules. The UEEPCI would also play a crucial role facilitating the process of determining and defining integrity within SEFIR, including the responsibility for developing, implementing, and updating codes of integrity, as recommended (OECD 2017b).

To be able to fulfil this key mandate of the public integrity system, Coahuila should guarantee that the UEEPCI has the organisational, financial, and human resources required for providing implementation support to the policies it provides. UEEPCI membership should be a full-time position. Currently, it seems that SEFIR cannot fulfil its mandate to ensure effective implementation and guidance to other agencies due to a lack of resources and lack of clear communication, which might be due to insufficient financial and human resources. An additional challenge may arise out of the different capacities of entities and at the municipal level. Some municipalities might lack the resources to adapt policies and will need to be guided to develop a long-term strategy on how to develop capacities, which in turn will require more resources. In addition, SEFIR should ensure that existing programmes and related resources dedicated to cultivating a culture of integrity in the public administration are closely co-ordinated with the Ministry of Finance (Secretaría de Finanzas de Coahuila), responsible for human resources, in order to mainstream integrity policies in each phase of the human resources process.

To ensure an effective implementation of integrity policies throughout the public administration, Coahuila could consider establishing Integrity Contact Points (or persons) within each public entity. The Integrity Contact Points should be responsible for public ethics and not be responsible for investigating breaches of integrity.

Implementing and mainstreaming the integrity policies throughout the administration is one of the challenges many central integrity bodies find themselves confronted with. Although integrity is ultimately the responsibility of all organisational members, the OECD recognises that dedicated “integrity actors” are particularly important to complement the essential role of managers in stimulating integrity and shaping ethical behaviour (OECD, 2009a). Harmonisation throughout the administration can be facilitated by creating a specialised contact point or person responsible for the implementation of integrity policies in the entity and promoting the policies. In addition, the Integrity Contact Points (or persons) can break the general policies and regulations down to the specific circumstances of each entity and provide tailored guidance on ethics and conflict of interest to the employees in case of doubts and dilemmas.

On the federal level, the Ethics Committees (Comités de Ética y de Prevención de Conflictos de Interés) in each federal entity are the official link and contact point between the Ethics Unit in the SFP and the federal entities. Each entity’s Ethics Committee is headed by the Chief Administration Officer (Oficial Mayor) as the only permanent member, with ten other members being elected for two-year terms by colleagues in the organisation. Currently, the responsibilities of the Ethics Committees revolve around three main issues:

-

Revision, implementation, and evaluation of the organisational codes of conduct

-

Promotion of guidance over integrity policies, including trainings

-

Reception and processing of integrity violations (Article 6, DOF 20/08/2015) (OECD, 2017b)

While stakeholders indicated that Coahuila plans to adopt a similar structure, there are currently no available details about the exact mandate, functions, and organisational integration of these committees or similar units in Coahuila.

Based on the positive experience of Germany (Box 2.1) and Canada (Box 2.2) and avoiding some of the weaknesses of the structure at the Mexican federal level, SEFIR could set up an institutional structure that clearly assigns integrity a place and gives the responsibility of promoting integrity policies to dedicated and specialised individuals or units within each entity. These individuals and units could fulfil the role of an Integrity Contact Point.

At federal level, Germany has institutionalised units for corruption prevention as well as a designated person responsible for promoting corruption prevention measures within a public entity. The contact person and a deputy have to be formally nominated. The “Federal Government Directive concerning the Prevention of Corruption in the Federal Administration” defines these contact persons and their tasks as follows:

-

A contact person for corruption prevention shall be appointed based on the tasks and size of the agency. One contact person may be responsible for more than one agency. Contact persons may be charged with the following tasks:

-

serving as a contact person for agency staff and management, if necessary without having to go through official channels, along with private persons

-

advising agency management

-

keeping staff members informed (e.g. by means of regularly scheduled seminars and presentations)

-

assisting with training

-

monitoring and assessing any indications of corruption

-

helping keep the public informed about penalties under public service law and criminal law (preventive effect) while respecting the privacy rights of those concerned

-

-

If the contact person becomes aware of facts leading to reasonable suspicion that a corruption offence has been committed, he or she shall inform the agency management and make recommendations on conducting an internal investigation, on taking measures to prevent concealment, and on informing the law enforcement authorities. The agency management shall take the necessary steps to deal with the matter.

-

Contact persons shall not be delegated any authority to carry out disciplinary measures; they shall not lead investigations in disciplinary proceedings for corruption cases.

-

Agencies shall provide contact persons promptly and comprehensively with the information needed to perform their duties, particularly with regard to incidents of suspected corruption.

-

In carrying out their duties of corruption prevention, contact persons shall be independent of instructions. They shall have the right to report directly to the head of the agency and may not be subject to discrimination as a result of performing their duties.

-

Even after completing their terms of office, contact persons shall not disclose any information they have gained about staff members’ personal circumstances; they may, however, provide such information to agency management or personnel management if they have a reasonable suspicion that a corruption offence has been committed. Personal data shall be treated in accordance with the principles of personnel records management.

Source: German Federal Ministry of the Interior “Rules on Integrity”, www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Broschueren/2014/rules-on-integrity.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

In Canada, designated senior officials and departmental officers are responsible for mainstreaming integrity polices in the organisation and providing advice:

Senior officials for public service values and ethics

-

The senior official for values and ethics supports the deputy head in ensuring that the organisation exemplifies public service values at all levels of their organisations. The senior official promotes awareness, understanding, and the capacity to apply the code amongst employees, and ensures management practices are in place to support values-based leadership.

Departmental officers for conflict-of-interest and post-employment measures

-

Departmental officers for conflict of interest and post-employment are specialists within their respective organisations who have been identified to advise employees on the conflict-of-interest and post-employment measures (…) of the Values and Ethics Code.

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/ve/snrs1-eng.asp.

As recommended by the OECD (2017b) on the federal level, the role of the Integrity Contact Points should be purely preventive and they should not process any integrity violations. The Integrity Contact Points would ensure the implementation of integrity policies and would contribute to the creation of a culture of integrity in which public officials can seek advice on public ethics and the management of conflict-of-interest situations.

The Integrity Contact Point needs to be integrated in the structure of each entity and would be assigned its own budget to implement the activities related to the mandate. The budget should be determined independently of internal pressure. Taking the size of the ministry and agency and potential budgetary constraints into account, some Integrity Contact Points might only be one dedicated person. As long as this person can fulfil the role of the Integrity Contact Point, this is sufficient. The Integrity Contact Points (or persons) in Coahuila should report directly to the head of the public entity, and should receive targeted trainings and guidance to fulfil their professional mandate from the UEEPCI in SEFIR. The UEEPCI would fulfil the role of co-ordination and liaising with the Integrity Contact Points (or persons) across the administration, monitoring their work, providing tools and materials, and supporting them with ad-hoc guidance and providing trainings. Additionally, the UEEPCI could consider establishing a network between the Contact Points.

The co-ordination agreement on collaboration on transparency and the fight against corruption between Coahuila and the federal Ministry of Public Administration (Secretaría de la Función Pública, SFP) could benefit from expertise on the federal level and could harmonise policies.

An agreement between Coahuila and the SFP on co-ordination has been established with the objective of implementing a special co-ordination programme to strengthen the state system for the control and evaluation of public management and collaboration in the area of transparency and combating corruption (Acuerdo de Coordinación que celebran la Secretaría de la Función Pública y el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, cuyo objeto es la realización de un programa de coordinación especial denominado Fortalecimiento del Sistema Estatal de Control y Evaluación de la Gestión Pública, y Colaboración en Materia de Transparencia y Combate a la Corrupción). While this agreement could lead to federal support on public ethics, interviews with stakeholders confirmed that the non-binding nature of the agreement has so far not yielded concrete results. Given the need to comply at a minimum with the standards set at the federal level, the implementation of the local anti-corruption system could be an opportunity to seek the support of the SFP, which has already implemented the majority of the public ethics policies related to the implementation of the anti-corruption system. SEFIR, as the leading actor, could actively approach the SFP for guidance throughout this process. Once the UEEPCI is established within SEFIR, the ethics unit on the federal and state level should co-ordinate and exchange good practices. This guidance could be formalised once the system is implemented through annual meetings between the two Ethics Units.

Harmonising policies and practices

The public integrity management framework could benefit from a more streamlined, duplication-free Code of Ethics and Conduct. Under the guidance of the Ethics Unit, Coahuila could consider the elaboration of manuals or guidance on practical examples and procedures for conflict-of-interest situations and ethical dilemmas.

Principles, ethical duties, and prohibitions articulate the boundaries of behaviour as well as expectations of behaviour of public officials. Of particular importance in guiding public officials is the definition of what constitutes a conflict of interest, and the provision of guidance in such situations. Realistic knowledge on which circumstances and relationships can lead to a conflict-of-interest situation should provide the basis for the development of a regulatory framework to manage a conflict-of-interest situation in a coherent and consistent approach across the public sector. Of key importance is the understanding and recognition that everybody has interests; interests cannot be prohibited, but rather must be properly managed. These reflections should be kept in mind during the harmonisation process of key legislation related to the establishment of the local anti-corruption system.

Currently, standards of conduct for Coahuila’s public officials are articulated in primary and secondary legislation (Table 2.1). The Law of Responsibilities of Public Servants at state and municipal level of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley de Responsibilidades de los Servidores Públicos Estatales y Municipales del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza) and the Organic Law of the Public Administration of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza) build the cornerstones of the ethics structure in the public administration. The Law of Responsibilities of Public Servants clearly defines what constitutes a conflict of interest and requires that public servants inform their superior of conflict-of-interest situations. Furthermore, the law provides specific obligations for public officials to prevent conflicts of interest in the public service, as well as regulations on the pre- and post-public employment phase. According to the same Law, failure to comply with these rules is an administratively sanctionable offence. If the public servant acts upon the conflict of interest, according to the criminal code of Coahuila, criminal sanctions can be administered for undue influence and illicit enrichment. These sanctions vary between six months to eight years of imprisonment for undue influence and up to ten years of imprisonment in cases of illicit enrichment.

Codes of conduct or ethics are recognised as an essential tool in guiding the behaviour of public officials in line with the official legal framework. Public sector ethics codes articulate boundaries of behaviour as well as expectations of behaviour. They should clearly outline the core values associated with being a public official and provide clear criteria as to what behaviour is expected and prohibited. Such a code can provide guidance to public officials on what circumstances and situations can lead to a conflict-of-interest situation, while at the same time highlighting that having interests per se is not forbidden, but rather that private interests must be managed. In this way, a code of conduct or ethics can provide the basis for the development of a regulatory framework to manage conflict-of-interest situations in a coherent and consistent approach across the public sector (OECD, 2017b).

The establishment of the Local Anti-corruption System and subsequent adaptation of the aforementioned laws provides Coahuila with a unique opportunity to revise the Code of Ethics and Conduct for public servants in the executive branch of the state of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Código de Ética y Conducta para los Servidores Públicos del Poder Ejecutivo del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza), which provides more details on the principles and values that public officials should adhere to. As a first step, the code could apply to all public officials of all branches and as such would act as an anchor point of ethical behaviour throughout the administration.

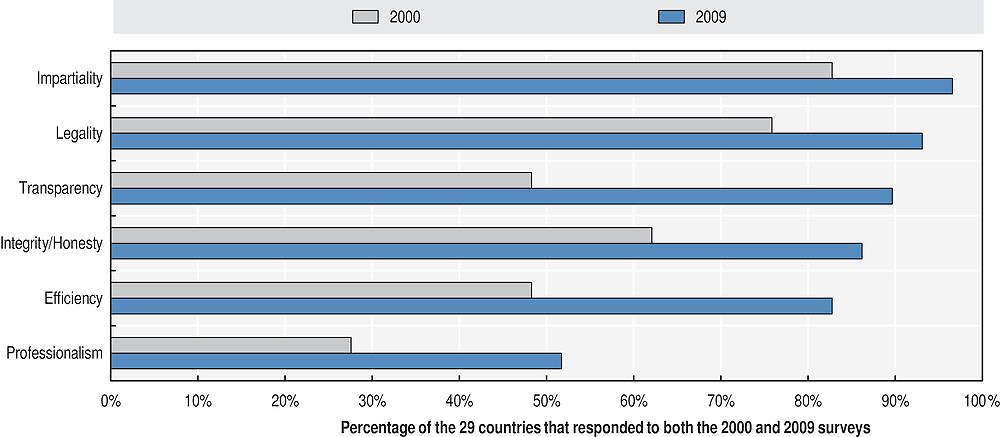

The general Code of Conduct encompasses institutional commitments, constitutional principles, and values of the public service (Constitution of the State of Coahuila, Article 160). The institutional commitments according to which public officials’ conduct shall be governed are public trust, public participation, combatting corruption and impunity, common good, and cultural and environmental concerns. The constitutional principles are efficiency, effectiveness, honesty, fairness, impartiality, integrity, loyalty, legality, leadership, accountability, respect, and transparency. These principles are similar to those of most OECD member countries and are widely considered as the pillars of integrity systems and the strengthening of trust in government (Figure 2.1). While explicitly stating institutional commitments in addition to constitutional principles and values can be useful, it may also prove repetitive and can lead to confusion among public officials (Box 2.3). The majority of institutional commitments can be derived from constitutional values, such as the commitment of public participation, already covered by transparency. Coahuila could consider limiting the commitments, as set out in Article 5, which would streamline the Code of Conduct and enhance clarity.

Note: Time series data are not available for the Slovak Republic.

Source: OECD (2009), Government at a Glance 2009, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264075061-en.

In the past, the Australian Public Service Commission used a statement of values expressed as a list of 15 rules. For example, they stated that the Australian Public Service (APS):

-

is apolitical and performs its functions in an impartial and professional manner

-

provides a workplace that is free from discrimination and recognises and utilises the diversity of the Australian community it serves

-

is responsive to the government in providing frank, honest, comprehensive, accurate, and timely advice and in implementing the government’s policies and programmes

-

delivers services fairly, effectively, impartially, and courteously to the Australian public and is sensitive to the diversity of the Australian public.

In 2010, the Advisory Group on Reform of the Australian Government Administration released its report, which recognised the importance of a robust values framework to a high-performing, adaptive public service, and the importance of strategic, values-based leadership in driving performance. The APS Reform Blueprint recommended that the APS values be revised, tightened, and made more memorable for the benefit of all employees and to encourage excellence in public service. It was recommended to revise the APS values to “a smaller set of core values that are meaningful, memorable, and effective in driving change”.

The model follows the acronym “I CARE”. The revised set of values runs as follows:

Impartial

The APS is apolitical and provides the government with advice that is frank, honest, timely, and based on the best available evidence.

Committed to service

The APS is professional, objective, innovative and efficient, and works collaboratively to achieve the best results for the Australian community and the government.

Accountable

The APS is open and accountable to the Australian community under the law and within the framework of ministerial responsibility.

Respectful

The APS respects all people, including their rights and heritage.

Ethical

The APS demonstrates leadership, is trustworthy, and acts with integrity, in all that it does.

Sources: Australian Public Service Commission (2011), “Values, performance and conduct”, www.apsc.gov.au/about-the-apsc/parliamentary/state-of-the-service/state-of-theservice-2010/chapter-3-values,-performance-and-conduct; Australian Public Service Commission (2012), “APS Values”, www.apsc.gov.au/aps-employment-policy-andadvice/aps-values-and-code-of-conduct/aps-values.

Unlike at the federal level, the Code of Ethics and Values in Coahuila does not have a specific provision on the management of conflict-of-interest situations. Coahuila could consider adapting the code to introduce a provision on conflict of interest.

The code is a helpful tool to define the core values public officials should observe in their work. However, additional guidance on what it means to adopt these values in their daily work could help public officials to internalise them. The established principles and values overlap with those established by the recently passed Code of Ethics and Rules of Integrity for Public Officials at the Federal Level (Código de Ética y Reglas de Integridad) (Box 2.4). However, in addition, the Federal Code comprises a set of specific desired and undesired conducts in 12 specific domains, as articulated in the Rules of Integrity, which complement the new Code of Ethics. SEFIR could develop a similar complementary manual. As recommended by the OECD (2017b), the Integrity Rules at the federal level appear too brief and may lack concrete examples or situations. Therefore, SEFIR could provide more practical guidance outlining concrete conflict-of-interest situations. For example, in the Netherlands, the government issued a brochure entitled “The Integrity Rules of the Game” which explains in clear, everyday terms the rules to which staff members must adhere. It considers real-life issues such as confidentiality, accepting gifts and invitations, investing in securities, holding additional positions or directorships, and dealing with operating assets (OECD, 2013). In Australia, concrete guidance is given to public officials on how to think through an ethical dilemma situation (Box 2.5).

The new Code of Ethics involves both general principles and values and a set of desired and undesired behaviours. The general Code of Ethics comprises a set of constitutional principles (legality, honesty, loyalty, impartiality, efficiency) as well as additional values (public interest, respect, respect for human rights, equality and non-discrimination, gender equality, culture and environment, integrity, co-operation, leadership, transparency, accountability) that every public servant should follow. These principles and values largely overlap with those established in the Code of Conduct of Coahuila. Coahuila’s Code, however, does not include the values of public interest, general respect, respect for human rights, equality and non-discrimination, gender equality, or co-operation.

On the other hand, a set of specific desired and undesired conducts is articulated in the Rules of Integrity, which complement the new Code of Ethics and which are divided in 12 specific domains:

-

Public behaviour

-

Public information

-

Public contracting, licensing, permits, authorisations, and concessions

-

Governmental programmes

-

Public procedures and services

-

Human resources

-

Administration of public properties

-

Evaluation processes

-

Internal control

-

Administrative procedures

-

Permanent performance with integrity

-

Co-operation with integrity

Source: OECD (2017b), OECD Integrity Review of Mexico: Taking a Stronger Stance Against Corruption, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273207-en.

The Australian Government developed and implemented strategies to enhance ethics and accountability in the Australian Public Service (APS), such as the Lobbyists Code of Conduct, the register of “third parties”, the Ministerial Advisers’ Code and work on whistleblowing and freedom of information.

To support the implementation of the ethics and integrity regime, the Australian Public Service Commission enhanced its guidance on APS Values and Code of Conduct issues. This includes integrating ethics training into learning and development activities at all levels.

To help public servants in their decision-making process when facing ethical dilemmas and choices, the Australian Public Service Commission developed a decision making model. The model follows the acronym REFLECT:

-

REcognise a potential issue or problem

Public officials should ask themselves:

-

Do I have a gut feeling that something is not right or that this is a risky situation?

-

Is this a right vs. right or a right vs. wrong issue?

-

Can I recognize the situation as one that involves tensions between APS Values or the APS and my personal values?

-

-

Find relevant information

-

What were the trigger and circumstances?

-

Identify the relevant legislation, guidance, policies (APS-wide and agency-specific).

-

Identify the rights and responsibilities of relevant stakeholders.

-

Identify any precedent decisions.

-

-

Linger at the “fork in the road”

-

Talk it through, use intuition (emotional intelligence and rational processes), analysis, listen, and reflect.

-

-

Evaluate the options

-

Discard unrealistic options.

-

Apply the accountability test: public scrutiny, independent review.

-

Be able to explain your reasons/decision.

-

-

Come to a decision

-

Come to a decision, act on it, and make a record if necessary.

-

-

Take time to reflect

-

How did it turn out for all concerned?

-

Learn from your decision.

-

If you had to do it all over again, would you do it differently?

-

Source: Office of the Merit Protection Commissioner, “Ethical Decision Making” (2009), www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/values-and-conduct.

The Ethics Unit within SEFIR needs to ensure that such manuals are revised and updated regularly in order to be a useful resource for public officials. Furthermore, in co-ordination with the Integrity Contact Points (or persons), the Ethics Unit would be responsible for the distribution of the manuals throughout the entire administration, including municipalities, regulatory bodies, and state-owned enterprises.

A common overarching integrity management framework provides the opportunity to elaborate codes of conduct on the organisational level in a participative way and to implement them more effectively.

As a consequence of the code’s concision, on several issues the adopted language omits important details (for example, regarding cases when an employee thinks that he or she has received an illegal instruction from a superior). The code needs to be relevant for different public officials who exercise different functions with varied levels of responsibility and vulnerability to corruption. It therefore needs to be concise and general. However, this concision is a common caveat of codes designed to address the whole of the public sector.

Just as different organisations face different contexts and kinds of work, they may also be faced with a variety of ethical dilemmas and specific conflict-of-interest situations. For instance, the challenges might differ significantly between the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Health, and the different supervisory and regulatory bodies. In particular, the OECD experience on conflict-of-interest management shows that public officials should be provided with real-world examples and discussions on how specific conflict situations have been handled. Organisational Codes of Conduct provide an opportunity to include relevant and concrete examples from the organisation’s day-to-day business to which the employees can easily relate.

The organisational codes should be created using consensus and ownership, and should provide relevant and clear guidance to all public servants. Consulting and involving employees in the elaboration of the code of conduct through focus group discussion, surveys, or interviews can help build consensus on the shared values and principles of behaviour and can increase staff members’ feelings of ownership and compliance with the code.

In addition, the experience of OECD countries demonstrates that consulting or actively involving external stakeholders – such as providers or users of the public services – in the process of drafting code may help to build a common understanding of public service values and expected standards of public employee conduct. External stakeholder involvement could thereby improve the quality of the code so that it meets both public employees’ and citizens’ expectations, and could thus communicate the values of the public organisation to its stakeholders.

Apart from SEFIR, no other entity has developed a separate, specific code of conduct. SEFIR’s code responds to its specificities and provides guidance with respect to expected behaviour. By adopting their own codes of conduct, government entities can respond to specificities of functions that are considered particularly at risk. However, it may be challenging to maintain consistency among a large number of codes within the public administration.

The process over the coming months of elaborating an overarching integrated public integrity management framework opens the opportunity for drafting specific codes of conduct and ethics within the entities in alignment with the principles set by the Code of Conduct and Ethics at the state level. Therefore, SEFIR could consider stipulating that entities have to develop their own codes of conduct based on the existing state Code of Conduct and Ethics. SEFIR should provide clear methodological guidance to assist the entities in developing their own codes, while ensuring that they align with the overarching principles. Such methodological guidance should reduce as much as possible the scope for developing the code as a “check-the-box” exercise, and should include details on how to manage the construction, communication, implementation, and periodic revision of the codes in a participative way.

Coahuila can benefit from the experience at the federal level, where SFP has written a guidance note on how to elaborate a code of conduct. Similarly, in Brazil, the consultation process undertaken for the Comptroller General of the Union’s code of conduct raised issues that served as input for the government-wide integrity framework (Box 2.6).

Another key aspect during the drafting process is to ensure that the codes of conduct are drafted in a way that clearly specifies their link to the Law on Responsibilities and possible sanctions for breaches of the provisions. Public officials must be aware of the responsibilities that come along with the Code of Conduct. Sanctions related to the codes should be reported to the Ethics Unit of SEFIR to be analysed, publicised, and to ensure that sanctions are adequate and consistent throughout ministries and entities. Effective control and visible sanctions are crucial in generating credibility. An overview of what characterises successful codes in the private sector, for instance, concludes that blatant impunity of violations of codes can generate cynicism and may lead to a culture of corruption in an organisation (Stevens, 2008).

The Professional Code of Conduct for Public Servants of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union was developed with input from public officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union during a consultation period of one calendar month, between 1 and 30 June 2009. Following inclusion of the recommendations, the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union Ethics Committee issued the code.

In developing the code, a number of recurring comments were submitted. They included:

-

the need to clarify the concepts of moral and ethical values: it was felt that the related concepts were too broad in definition and required greater clarification

-

the need for a sample list of conflict-of-interest situations to support public officials in their work

-

the need to clarify provisions barring officials from administering seminars, courses, and other activities, whether remunerated or not, without the authorisation of the competent official

A number of concerns were also raised concerning procedures for reporting suspected misconduct and the involvement of officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union in external activities. Some officials inquired whether reports of misconduct could be filed without identifying other officials and whether the reporting official’s identity would be protected. Concern was also raised over the provision requiring all officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union to be accompanied by another Office of the Comptroller General of the Union official when attending professional gatherings, meetings, or events held by individuals, organisations or associations with an interest in the progress and results of the work of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union. This concern derived from the difficulty in complying with the requirement given the time constraints on officials and the significant demands of their jobs.

Source: OECD (2012), Integrity Review of Brazil: Managing Risks for a Cleaner Public Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119321-en.

SEFIR could develop specific guidelines for at-risk categories of public officials such as senior civil servants, auditors, tax officials, political advisors, and procurement officials.

The role of ensuring clear guidance also encompasses taking into consideration the specific risks associated with the administrative functions and sectors that are most exposed to corruption (see also Chapter 4 on internal control and risk management). While the individual public official is ultimately responsible for recognising the situations in which conflicts may arise, most OECD countries have tried to define those areas that are most at risk and have attempted to provide guidance to prevent and resolve conflict-of-interest situations. Indeed, some public officials operate in sensitive areas with a higher risk for conflict of interest, such as justice, and tax administrations and officials working at the political/administrative interface. Special standards are needed for these sectors. For example, although the areas of activity are not the same, procurement officers in education and health face similar challenges and specific conflict-of-interest rules for public procurement officials would be helpful. On the federal level, countries such as Canada, Switzerland, and the United States aim to identify the areas and positions which are most exposed to actual conflict of interest. For these, regulations and guidance are essential to prevent and resolve conflict-of-interest situations.

On the federal level in Mexico, one of the executive orders issued led to the creation of the code of conduct for all public servants and a protocol for interactions between procurement officials and suppliers (Presidencia de la República, 2015). The Law on Government Acquisitions, Leases and Services of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Contratación de Servicios para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza) and the Law of Public Works and Related Services of the State of Coahuila de Zaragoza (Ley de Obras Públicas y Servicios Relacionados con las Mismas para el Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza) identifies the procurement process as particularly at risk for conflict-of-interest situations and has introduced a mandatory declaration confirming the absence of any conflict of interest for government contractors and suppliers. In the short term, Coahuila could support public procurement officials further in applying these regulations by providing a manual on conflict-of-interest situations specific to public procurement and how public officials can identify them (for further information, see Chapter 6). As a long-term goal, Coahuila could establish specific conflict-of-interest policies and guidance for other remaining at-risk areas such as senior civil servants, auditors, tax officials, and political advisors. The specific risk-based guidance would complement the organisational codes mentioned before.

Raising awareness and providing training

A cross-departmental public ethics awareness campaign could be implemented as a shared and co-ordinated activity between the Ethics Unit, Integrity Contact Points (or persons), and human resources departments in public entities, including reaching out to the private sector, civil society, and citizens.

Although integrity codes are themselves tools adopted to raise awareness of common values and standards of behaviour in the civil service, the vast majority of OECD member countries employ additional measures to communicate core values for public servants. Professional socialisation enables public servants to apply the core values in concrete circumstances. This requires informing them of the expected standards of behaviour and developing skills to help them solve their ethical dilemmas. A clear communication strategy to raise awareness with respect to integrity policies and available tools and guidance should make use of existing and innovative channels of communication. Particularly with respect to awareness-raising measures for conflict-of-interest management, OECD countries generally use complementary awareness-raising measures in order to ensure a comprehensive effort in this regard. These measures can range from:

-

dissemination of rules or guidelines when the public official takes office

-

proactive updates regarding changes to the public integrity framework

-

publication of the public ethics policies online or on the organisation’s intranet

-

regular reminders about public integrity policies

-

training

-

regular guidance and assistance

-

an advice line or help desk where officials can receive guidance on filing requirements or conflict-of-interest identification or management (OECD, 2014)

Public officials in Coahuila receive the Code of Ethics and Conduct automatically when joining the public service and are asked to sign a statement of commitment (Figure 2.2). When changing to a post in a different ministry or government entity, the statement of commitment has to be signed again. The human resource manager and/or administrative co-ordinator in each ministry and government unit is responsible for overseeing the process. After introducing the Code of Ethics and Conduct in 2013, the code was sent to each head of unit for further dissemination and it was sent to each public official electronically. Every public official had to sign the statement of commitment.

Source: Information provided by Coahuila’s Ministry for Audit and Accountability.

While the responsibility to disseminate and promote the code of conduct and ethics lies with each ministry and government entity, the Deputy ministry of Government Auditing and Administrative Development (Subsecretaría de Auditoría Gubernamental y Desarrollo Administrativo) within SEFIR has developed the Programme of Ethics and Values. This Programme comprises several initiative aimed at raising awareness not just among the public administration, but also among citizens (Box 2.7):

-

Posters displaying values hung up in each ministry and government entity

-

Dissemination through the internal network: in SEFIR, for example, a “value of the month” is displayed on employee’s computer screens

The purpose of the State Public Values and Ethics program is to generate and promote a culture of principles and values that will strengthen the way public servants work in the public administration. The Code of Ethics and Conduct of the Public Servants was published in the Official Newspaper of the State in 2013. In addition, the strategy of “wanting, knowing, acting” (querer, saber y actuar) was established:

-

“wanting”: a continuous process of awareness-raising as well as dissemination through the promotion and distribution of banners, buttons, and triptychs

-

“knowing”: continuous training on values and ethics

-

“acting”: revision of the applicable regulations and the implementation of a letter of commitment

Source: Information provided by the government of Coahuila.

Awareness-raising aimed at citizens consists of:

-

Buttons with the slogan “With ethics and values, better public officials” (Con Ética y Valores, Funcionarios Mejores) for officials interacting directly with the public

-

Banners with the values and principles as established in the code of conduct and ethics: these are hung up in visible places in each ministry and government entity

-

Leaflets with specific information about the values and responsibilities of public officials

However, there is little evidence that generic communication campaigns promote a culture of integrity and raise awareness of the importance of abiding by public service values and ethics in managing conflict-of-interest situations. While the current initiatives are an important first step, Coahuila could strengthen these efforts by making them more targeted. For examples, both the posters and the “value of the month” campaign are limited to the values in the Code of Conduct and Ethics. These initiatives do not provide information on any practical situations. If concrete examples were provided about what a particular value might mean, public officials would be encouraged to think about the value and internalise it. For example, the poster of the Standards of Integrity and Conduct of New Zealand (Figure 2.3), which is displayed to public officials and citizens in public institutions, gives concrete examples about what each value means.

Source: State Service Commission (2007), Standards of Integrity and Conduct, available from www.ssc.govt.nz/sites/all/files/Code-of-conduct-StateServices.pdf, used under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/nz/

Well-formulated advice in the form of questions and answers is also useful and employed in, for example, Germany (Box 2.8).

An example of a technologically basic but useful tool is the publication “Answers to frequently asked questions about accepting gifts, hospitality or other benefits” published by the Federal Ministry of Interior of Germany. This catalogue of questions and answers was not drafted exclusively by a controlling agency, but by a group of chief compliance officers from large and medium enterprises, federal ministries, and associations. As a result, it reflects not only a top-down imposed interpretation of rules but also a shared understanding between public and private parties. The publication covers:

-

Basic information: Are federal administration employees allowed to accept gifts? What is meant by gifts, hospitality, and other benefits?

-

Dealing with gifts: Is approval always required for accepting a gift, even promotional items? What should I do if I am not sure whether it is legal to give or accept a gift?

-

Gifts in kind: Am I allowed to give a book or professional journal related to the employee’s field of expertise?

-

Invitations, hospitality: Is it possible to invite employees to a buffet meal or snack during or after a specialist event? Is it possible to invite spouses or life partners to events?

-

Paying for travel expenses: Is it possible for a third party to pay an employee’s travel expenses? What should a federal employee do if offered a ride in a taxi or rental car by a business partner?

-

Delegation travel: What should one be aware of regarding delegation or factory visits? What should be noted when requesting reimbursement for travel expenses for a delegation or factory visit?

-

Private use of discounts: When can the private use of discounts be approved? When is the private use of discounts prohibited?

Altogether, 52 questions are answered in a concise, easily accessible manner. An index of key terms with up-to-date hyperlinks facilitates the search.

Source: Federal Ministry of the Interior, “Private Sector/Federal Administration Anti-Corruption Initiative – Answers to frequently asked questions about accepting gifts, hospitality, or other benefits”, www.jaunde.diplo.de/contentblob/3809240/Daten/2296502/FragenkatalogKorruption.pdf., OECD (2016).

Furthermore, it seems that the current efforts are concentrated within SEFIR and rarely reach the other entities or municipalities. The creation of the Integrity Contact Points (or persons) in the entities and co-ordination with the UEEPCI in SEFIR will help to reach a wider audience. The UEEPCI could encourage the Integrity Contact Points (or persons) to develop specific awareness campaigns for their entities. Coahuila may also wish to issue a cross-departmental awareness campaign akin to that of the UK, where the Civil Service Commission, working in conjunction with the Cabinet Office and a group of Permanent Secretaries, produced a best practice checklist of actions for departments to uphold and promote the Code.

Under the lead of the Ethics Unit in SEFIR, a public integrity training programme could be developed based on the results of the survey on training needs (Encuesta de Detección de Necesidades de Capacitación) applied in 2014. A public ethics and conflict-of-interest training when joining the public service could be made mandatory for all public officials, and specific tailored trainings could be provided on an annual basis.

Training on ethics and conflict-of-interest management for public officials is one of the necessary instruments for building integrity in the public sector and ensuring high-quality public governance. Since staff may change over time, institutions must be committed to providing continuous training on applying public ethics and identifying and reacting to conflict-of-interest situations. The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) requires that the state parties “promote education and training programmes to enable [public officials] to meet the requirements for the correct, honourable and proper performance of public functions and that provide them with specialised and appropriate training to enhance their awareness of the risks of corruption inherent in the performance of their functions” (UNCAC, Article 7 [d]). Similarly, the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017a) recommends offering induction and on-the-job integrity training to raise awareness and equip public officials with the necessary skills to apply public integrity values and standards.

As such, at least one public agency must be responsible for the overall framework for training on conflict-of-interest management and ethics, for central planning, co-ordination, and evaluation of results. In fact, most OECD countries’ training modules are developed by a single central entity that also offers guidance on how public employees should apply their codes of conduct, particularly in sensitive situations. For example, in Turkey, the Council of Ethics for Public Officials is the leading institution in the provision of ethics training.

In Coahuila, SEFIR is responsible for the overall framework of training on conflict-of-interest management and co-ordination among the public entities. The state programme of administrative modernisation, audit, and accountability 2011-17 (Programa Estatal de Modernización Administrativa, Fiscalización y Rendición de Cuentas) foresees the development of a training programme to promote the professional development of public servants based on a 2014 survey aiming at detecting needs (Encuesta de Detección de Necesidades de Capacitación). SEFIR has established a state training programme including a mandatory course on values and ethics of public officials. In 2016, a total of 141 public officials received training on ethics and values, and 68 public officials received a training course on the reform of the conflict of interest policies. To systematise these efforts, the Anti-corruption System, the UEEPCI in co-ordination with central Human Resources Office in the Ministry of Finance, and the Institute for Training could develop a detailed training programme aimed at building the capacities of all public officials in the area of public integrity similar to the training programme on ethics in Brazil (Box 2.9). This could be part of the State Capacity Programme and should take into account the diagnostic resulting from the needs detection survey.

In 2010, the Public Ethics Commission and the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union developed a management training and development course to support public officials on standards of conduct. The 40-hour course is organised in five modules, and its contents are based on Public Ethics Commission resolutions and other guidance materials. Satisfactory completion of this course has been proposed as a criterion for career progression. The modules offered in the course cover the following topics:

-

Principles of ethics: key concepts, prevailing values and standards, their inter-relation and functions

-

Principles of policy and public service: key concepts of public life and fundamental values of the Brazilian federal public administration

-

Ethics management in the federal public administration: norms applicable to the federal public administration and governmental actors with responsibility for encouraging public ethics

-

Ethics management in the federal public administration: exploring the code of professional ethics for the federal public administration

-

Addressing ethical dilemmas: identifying dilemmas, ethical guidance and filing complaints, attributes and routines to reinforce ethics in the federal public administration

Sources: OECD (2012), OECD Integrity Review of Brazil: Managing Risks for a Cleaner Public Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, p. 251, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119321-en; OECD (2014), “Renforcer l’Intégrité en Tunisie: L’Élaboration de Normes pour les Agents Publics et le Renforcement du Système de Déclaration de Patrimoine”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/mena/governance/Renforcer-Intégrité-Tunisie-Élaboration-Normes-Agents-Publics.pdf.

An induction training on public ethics and conflict of interest should be made mandatory. Such induction trainings are a valuable opportunity to set the tone with respect to integrity from the beginning of the working relationship. They provide an opportunity to explain principles, values, and the rules related to public ethics and conflict of interest. The most basic and generic parts of such a training could be implemented through e-learning modules, while a more targeted training aimed at recognising and managing conflicts of interest and resolving ethical dilemmas specific to situations commonly encountered in their area of work could be in-person training (Box 2.10).

In the Dilemma training offered by the Agency for Government Employees, public officials are given practical situations in which they face a difficult ethical choice. The facilitator encourages discussion among the participants about how the situation could be resolved to explore the different choices. As such, it is the debate, and not the solution, which is most important. Over the course of the debate, participants will learn to identify different, potentially conflicting values.

In most trainings, the facilitator uses a card system. He explains the rules and participants receive four “option cards” printed with the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4. A stack of “dilemma cards” is placed on the table. The “dilemma cards” describe situations and propose four options for resolving them. In each round, one of the participants reads out the dilemma and options. Each participant indicates their choice by holding up the “option card” with the corresponding number and explains the choice. Following this, participants discuss the choices. The facilitator remains neutral, encourages the debate, and suggests alternative options on how to look at the dilemma (e.g. sequence of events, boundaries for unacceptable behaviour).

One example of a dilemma situation is as follows:

I am a policy officer. The minister needs a briefing within the next hour. I have been working on this matter for the last two weeks and should already be finished. However, the information is not complete. I am still waiting for a contribution from another department to verify the data. My boss asks me to submit the briefing urgently because the chief of cabinet has called. What should I do?

-

I send the briefing and do not mention the missing information.

-

I send the briefing, but mention that no decisions should be made based on it.

-

I do not send the briefing. If anyone asks about it, I will blame the other department.

-

I do not send the briefing. I provide an excuse for its tardiness and promise that I will send it tomorrow.

Other dilemma situations could cover the themes such as conflicts of interest, ethics, loyalty, and leadership. The trainings and situations used can be targeted to specific groups or entities. For example:

You are working in Internal Control and are asked to be a guest lecturer in a training programme organised by the employers of a sector that is within your realm of responsibility. You will be well paid, make some meaningful contacts, and learn from the experience.

Source: Website of the Flemish Government, Omgaan met integriteitsdilemma’s, available from https://overheid.vlaanderen.be/omgaan-met-integriteitsdilemmas (in Dutch).

Beyond the induction training, efforts should be undertaken to provide continuous training for high-level public officials. For example, in Catalonia, training participants have to develop their own integrity action plan. In this plan, each participant identifies integrity risks and challenges in their individual workplaces. During the follow-up trainings, participants discuss the implementation of their personal plan. They also discuss barriers that have been identified in implementing the actions proposed in their individual action plan, and provide support and share ideas about solutions.

Another tool would be to offer annual courses for public officials in which they can gain new integrity skills. Senior public officials in management positions or HR officers in each public entity could attend these courses. They could also be trained in disseminating conflict-of-interest policies in the organisation. Indeed, given the importance of high positions with leadership functions in promoting and ensuring a high level of integrity, many OECD countries rely on senior civil servants both in terms of individual development and in terms of special management rules, processes, and systems to provide guidance. Such guidances comes in the form of advice and counsel to lower-ranking public servants about how to resolve dilemmas at work and potential conflicts of interest. Senior civil servants embody and transmit core public service values, set the example in terms of performance and probity, and communicate the importance of these elements as a means of safeguarding public sector integrity.

Training and education may range from value-oriented to rules-based and dilemma type programmes in order to help public officials fully grasp the entire code of ethics. Senior management could attend each training programme in order to better lead by example and to offer constant guidance to staff on how to apply the code on a day-to-day basis. The training programme should also take into account the specificities of high-risk areas such as those encountered by auditors or public procurement officials (for further information see Chapter 6).

In addition, anticipating the new integrity framework that will be implemented through the local anti- corruption system, specific courses could be developed to present the recent and new provisions and tools. This could be done via an e-learning course that would be more accessible to public officials, given that physical attendance would not be required.

The impact of the existing Network of Trainers (Red Estatal de Instructores) could be amplified by formalising the network and building a pool of trainers in each ministry. As a form of recognition for their efforts, trainers could receive a formal qualification and/or remuneration.

With guidance from the UEEPCI, Coahuila could promote organisation-specific induction trainings related to the codes of conduct of the different entities. Such organisation-specific trainings could build upon more generic guidance and tools while making these more context-specific by introducing examples and cases related to the sector and the specific public services provided by the entity.

A Network of Trainers (Red Estatal de Instructores) has been created in which instructors are selected from each ministry to deliver specific trainings. This is a very positive step which could be strengthened. The network could be leveraged to implement tailored training programmes for entities and public officials in positions that represent a high risk of corruption. These specific trainings should be part of the induction trainings for new employees and the specific training throughout public servants’ career. In this way, the network could be similar to an initiative in Estonia where the Ministry of Finance co-ordinates a horizontal “Central Training Programme” and is responsible for commissioning various training programmes such as the induction programme and the general programmes on civil service and public ethics.

In interviews with stakeholders, it was confirmed that due to the existing state of the network, the Network of Trainers would not be able to fulfil this function. The training activities provided are not formally recognised, and trainers need to give the courses in their spare time. As such, Coahuila could consider providing formal public integrity trainer certification courses to interested public servants. These certification courses could be held by the UEEPCI in collaboration with human resources departments. If each trainer were certified, the quality of the courses could therefore be improved. Furthermore, the additional certification could be an incentive for potential candidates. Once certified, trainers could be granted an allocated time per year during which they could hold training courses in their entities. Coahuila could consider giving the trainers a small remuneration or recognition for their efforts. Managers could encourage certain public servants to participate in the certification course if they perceive them to be good potential trainers.

The future Ethics Unit in SEFIR and Integrity Contact Points (or persons) in the entities could also consider raising awareness of the conceptual overlap of managing a conflict-of-interest situation on an ad-hoc basis and the annual asset declaration.

Interviews revealed some confusion amongst public officials concerning asset declarations and conflict-of-interest management. Clarifying the conceptual overlap between the procedures for ad hoc disclosure of actual conflict-of-interest situations under the policy guidance of the Ethics Unit in SEFIR and the annual declaration of assets is important. It needs to be clearly communicated that submitting the declaration does not relieve the public official from proactively declaring any potential or actual conflict-of-interest on an ad-hoc basis to their superiors or the Integrity Contact Points (or persons). These efforts could be embedded in the existing awareness internal and external campaign on the disclosure system (web portal, social media, emails, newsletter, video tutorials, and thematic chats).

Strengthening the asset disclosure system

Adapting state regulations to the General Law on Administrative Responsibilities will entail modifications of the current asset disclosure system and will require all public officials to submit an asset declaration. Narrowing down the circle of public officials required to submit an asset declaration to those in senior positions and those representing a high corruption risk would ensure that no culture of distrust is created and improve the system’s cost-effectiveness.

The General Law on Administrative Responsibilities (LGRA) contains provisions related to the disclosure of both financial and non-financial interests. It requires that all public officials submit three types of disclosure forms: tax, assets, and interests (OECD, 2017b). Assuming that the asset disclosure system will adopt the same level of details as the federal level, the type of information requested from public officials in Coahuila, along with the subsequent levels of transparency, is generally in line with the information request in other OECD countries. For comparison purposes, Box 2.11 provides a summary of common information requirements in OECD member and partner countries.

Generally, the following types of information are required to be disclosed in OECD member and partner countries. These can include financial and non-financial interests:

Financial interests

Reporting of financial interests facilitates the monitoring of wealth accumulation over time and the detection of illicit enrichment. Financial information can also help to identify conflict of interest situations.

-

Income: Officials in OECD countries are commonly asked to report income amounts as well as the source and type (i.e. salaries, fees, interest, dividends, revenue from sale or lease of property, inheritance, hospitalities, travel paid, etc.). The exact requirements of income reporting may vary and moreover public officials may only be required to report income above a certain threshold. The rationale for disclosing income is to indicate potential sources of undue influence (i.e. such as from outside employment) as well as to monitor over time increases in income that could stem from illicit enrichment. In countries where public officials’ salaries are low, this is of particular concern.

-

Gifts: Gifts can be considered a type of income or asset, however, since they are generally minor in value, countries generally only require reporting gifts above a certain threshold, although there are exceptions.

-

Assets: A wide variety of assets are subject to declaration across OECD countries including savings, shareholdings and other securities, property, real estate, savings, vehicles/vessels, valuable antiques and art. Reporting of assets permits for comparison with income data in order to assess whether changes in wealth are due to declared legitimate income. However, accurately reporting on the value of assets can be a challenge in some circumstances and difficult to validate. Furthermore, some countries make the distinction between owned assets and those in use (i.e. such as a house or lodging that has been loaned but is not owned).

-

Other financial interests: In addition to income, gifts and assets, other financial interests to declare often include debts, loans, guarantees, insurances, agreements which may result in future income, and pension schemes. When such interests amount to significant values, they can potentially lead to conflict-of-interest situations.

Non-financial interests

While monitoring non-financial interests may not contribute to monitoring for illicit enrichment, they can nonetheless also lead to conflict-of-interest situations. As such, many countries request disclosure of:

-

Previous employment: Relationships or information acquired from past employment could unduly influence public officials’ duties in their current post. For instance, if the officials’ past firm applied to a public procurement tender where the public official had a say in the process, his or her past position could be considered a conflict of interest.

-

Current non-remunerated positions: Board or foundation membership or active membership in political party activities could similarly affect public officials’ duties. Even voluntary work could be considered to influence duties in certain situations.

Source: OECD (2011), Asset Declarations for Public Officials: A Tool to Prevent Corruption, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264095281-en.

The current scope of coverage and transparency is considerably lower. The scope of coverage will increase to all levels of government and to public officials in all three branches of government. The coverage will also increase by requiring information of officials’ immediate family members. In addition, the extent of transparency will increase. Publication is currently voluntary and remains at the discretion of the public official (OECD, 2017b).

These changes can strengthen public trust in government by clearly showing its commitment to transparency and by offering a tool with which to enable social accountability, given that citizens could analyse public officials’ decisions in the light of the declared assets and relations (OECD, 2017b). Indeed there has been some recent empirical cross-country evidence showing that the expansion of financial disclosure systems positively and significantly affect a country’s capacity to control for corruption in the years following the expansion (Vargas et al., 2016).

However, it could be argued that the reporting requirements should take into account varying levels of public officials and should adopt a risk-based approach. The first argument in favour of these two evolutions is that elected officials are expected to be more transparent so that citizens may make informed choices when voting in elections. Furthermore, once elected, such information may be necessary to assess any interests which may influence parliamentarians’ arguments or voting decisions in Congress. It could also be argued that, given their decision-making powers, elected officials and senior civil servants are more influential and are at greater risk for capture or corruption. In addition, a blanket requirement for all public officials can have potentially detrimental effects on the morale of some public servants. For instance, some officials could interpret this requirement as creating an organisational culture whereby public servants are presumed to be corrupt. As such, the law may inadvertently increase the incentive for omissions and false information, and may reduce the attractiveness of working in the public sector, making it more difficult for government to recruit or retain top talent (OECD, 2017b).

Furthermore, despite the use of an electronic platform, the universal requirement to file an asset and interest declaration may overburden the bodies responsible for receiving and screening the disclosures, detecting irregularities, and fulfilling other activities related to their mandate if such tasks are not accompanied by appropriate human and financial resources.

To ensure an effective process, Coahuila could consider narrowing down the size of the disclosure population by applying common criteria used in other countries to determine who should declare (see Box 2.12 on the mandatory asset declaration for selected officials in Argentina), such as:

-

branch of government

-

hierarchy (for example, all officials at the director level and above)

-

position (minister, deputy minister, director, etc.)

-

function (administrative decision making, granting contracts, public procurement, tax inspection, etc.)

-

risk of corruption: identifying filers based upon their role and the risk they could become involved in corrupt activity (building licenses, infrastructure contracts, customs, etc.) (World Bank, 2017)

-

categorisation as a Politically Exposed Person (PEP) according to the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering

The government agency in charge of managing the Argentinian Assets Declaration System is the Anti-corruption Office under the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, in co-ordination with the Federal Administration of Public Revenues Agency. The asset disclosure system in Argentina does not require all public officials to declare their assets. Individuals who are obligated to present their asset declarations are:

-

hierarchical level: from the President to the officials with a position of National Director or equivalent

-

nature of their function: those who, beyond the rank, are public officials or employees members of procurement commissions or are responsible for granting administrative authorisations for the exercise of any activity or controlling their operation. Also, those who control public revenues should present their asset declaration.

-

candidates to national elective positions

These public officials have to present their declarations in three situations: 1) within 30 days of having started their public functions, 2) annually, and 3) after leaving the position. By June 2016, there were 48 494 obligations to present Asset Declarations.

Source: Government of Argentina, Presentar Declaración Jurada para funcionarios públicos, www.argentina.gob.ar/presentardeclaracionjurada (in Spanish).

The disclosure could be mandatory for those officials in high positions, those in functions with high risks of corruption, for instance based on the risk assessments carried out by public entities (Chapter 4), and those classified as PEP.

To effectively detect illicit enrichment, a systematic verification and audit process should be established. The electronic submission system could be leveraged by integrating the automatic verification of submission and automatic detection of “red flags”.

It is essential to establish a system of oversight to provide monitoring and enforcement. Indeed, the effectiveness of the disclosure regime depends on the system’s ability to detect violations and administer sanctions. Regular audits accompanied by a credible threat of sanctions are an effective deterrent against illicit enrichment and maintenance of conflict-of-interest situations (OECD, 2015). If public officials perceive that data stated in the declarations will most likely never be checked or used, there is a risk that the system will deteriorate into simply a “check-the-box” activity undermining confidence in the government’s commitment to the integrity system.

Currently, the asset disclosures are not verified or audited in a systematic manner. As it was recommended by the OECD (2017b) on the federal level, leveraging the electronic platform can facilitate compliance and permit automatic validation of receipt, triangulation with other databases (if linked), and the automatic notification of “red flags” (for mistakes, missing information, major changes in assets or income, etc.) (Table 2.2).

At the federal level, a combined approach, which is both decentralised and centralised, has been adopted. It is decentralised in the sense that individual internal control bodies in line ministries can collect and hold data, and centralised in the sense that relevant state entities can access and consolidate data for purposes of the electronic platform, which may be smaller in scope due to national privacy laws (OECD, 2017b).

Similar to the recommendation given by the OECD (2017b) at the federal level, internal control bodies should adopt a risk-based approach to verification and leverage digital tools to the fullest extent possible to detect illicit enrichment or conflict of interest effectively. Ideally, SEFIR would establish a set of guidelines for all internal control bodies to ensure a high-quality verification process.

Since 1988, French public officials have been obliged to declare their assets to prevent illegal enrichment. Until the end of 2013, the Commission for Financial Transparency in politics was responsible for controlling the declarations. As a consequence of various scandals, the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life (Haute Autorité pour la Transparence de la Vie Publique, HATVP) was created with a broader legal authority to ensure effective auditing of asset and interest declarations.

The HATVP receives and audits the asset and interest declarations of 14 000 high-ranking politicians and senior public officials:

-

members of government, parliament, and the European Parliament

-

important local elected officials and their main advisors

-

advisors to the President, members of government, and presidents of the National Assembly and Senate

-

members of independent administrative authorities

-

high-ranking public servants appointed by the Council of Ministers

-

CEOs of publicly owned or partially publicly owned companies

Some of the asset and private interest declarations are published online and will soon be reusable as open data. One of the exceptions is the asset declarations of parliamentarians, which are not published online, but are made available in certain local government buildings. Asset declarations of local elected officials and asset and interest declarations of non-elected public officials are not published, following a Constitutional council ruling in 2013.