Chapter 3. Schools driving progress and well-being in local communities1

With schools no longer seen as secluded spaces for learning, this chapter asks what can be learned from schools that partner with businesses, other educational services and cultural organisations, and truly engage with and contribute to their local community for the benefit of all concerned. Using case studies from the Innovative Learning Environment (ILE) project, it shows how schools can serve their communities through extracurricular and service-learning, teaching their students lifelong civic engagement, and how schools benefit from partnerships with businesses and cultural organisations. Noting the multidimensional nature of learning ecosystems, with learning taking place in families, workplaces and communities as well as schools, it considers how the barriers between formal, non-formal and informal learning can be broken down as networked learning systems evolve. Ultimately, such networks could become more than the sum of their parts, and make schools more widely accountable to their students, parents, and the community as a whole.

Introduction

In many countries schools are now increasingly seen as important spaces and hubs in the local community and regional economy. The time has long passed when schools were merely seen as secluded spaces where children and youngsters were dropped off and locked away while parents went to work. More and more schools are becoming outward looking and opening up to local communities and to the learning opportunities that the local environment provides. At the same time they are also taking on activities and roles promoting the common good and well-being in the local community. For example, schools offer extracurricular activities that enrich the life of the local community in sports, social care, voluntary work or culture. Research and development projects offer innovative answers to the needs of local enterprises and social-purpose organisations, while enhancing entrepreneurialism among students and providing real-world experiences. The concept of “service-learning”, which expresses the learning value of students engaging in providing services to the local community, offers an appealing vision of the opportunities available to schools to drive progress and well-being in local communities.

In connecting to the local and regional environment, schools also engage many stakeholders to work together to improve the well-being of everyone involved. Schools not only engage parents and families in learning, but also draw on the various resources provided by local enterprises, community organisations, social services, and sports and cultural institutions such as museums, theatres or libraries. Yet, because local communities differ in wealth and cultural capital, schools do not find themselves on a level playing field. Geographical segregation can lead to unequal opportunities for schools to benefit from engaging with the local community.

Still, schools can also become critically important partners in serving the needs of local communities, especially in disadvantaged communities or through working with populations at risk of exclusion or distress. In recent refugee crises in various parts of the world, there have been inspiring examples of schools playing a socially and ethically responsible role in providing help, shelter and assistance to refugees.

Creating wider partnerships is also an outstanding feature of innovative schools. They have an urgent drive to avoid isolation and are aware that significant innovation cannot be achieved and sustained alone. They look to build and maintain the capital they need as organisations – social capital, intellectual capital and professional capital through forging alliances, partnerships and networks. They extend themselves beyond given institutional and organisational boundaries, and introduce their learners to a range of other possibilities and resources, with benefits for both the learners and the community.

When looking at innovative schools, the range of some of their partnerships is quite impressive, as shown by the following three cases (as in Chapter 2, these case studies and the ones that follow are taken from OECD, 2013):

Jenaplan-Schule (Thuringia, Germany) co-operates with diverse institutional partners in the city and region. Prominent among the partners are: Goepel Electronics, the Planwerkstatt, the Schiller House, the Romantic House, the One-World-House, the Public Radio Channel Jena, the public cinema in the Schillerhof, Kommunal Real Estate Office of the City of Jena, the Ernst-Abbe Public Library, the University of Applied Sciences Jena, the University of Jena, the EJBW, the Protestant Adult Education Thuringia, the Philosophia e.V., the Imaginata, the Heritage Office, the City Museum Göhre, the Diskurs e.V., Grund genug e.V., the Theater House Jena and the German National Theatre in Weimar.

The starting point of Liikkeelle! (On the Move!) (Finland) was an initiative of the Finnish National Board of Education, which attracted the attention of the town of Kalajoki and the Science Center Heureka. They applied for the funding together, building on existing social networks and good practices. An important further partner has been PaikkaOppi (Location Learning), which collaborated in developing the interactive virtual map (their primary aim is to produce an interactive map for supporting the teaching of geography, geographical information systems (GIS), and environmental studies in schools). The template for the map came from National Land Survey of Finland. Other partners are the universities of Helsinki and Oulu who have helped to create new teaching methods, such as time-space-paths, and a jointly organised course for student teachers of the arts and upper secondary school students. In addition, the universities have contributed by studying Liikkeelle! and producing scientific knowledge and a survey report about the project. Commercial actors are also involved to further develop the virtual environment to accommodate the needs of teachers and learners.

A range of institutions collaborate with CEIP Andalucía, Seville (Spain) in different ways: the Cajasol Foundation (which subsidises library activities), RENFE (the Spanish railways network, which finances the travel expenses of some students to Madrid), the Universidad de Sevilla (teachers and students of the Faculty of Psychology do some hours in the school, in exchange for credits, and participate in interactive groups), and the Universidad Pablo de Olavide (scholarship holders of the Flora Tristán student residence and some teachers take part in interactive groups and in workshops, mainly on the radio).

What can we learn from schools that partner with businesses, other educational services and cultural bodies in their community, and that excel at driving business and social innovation in their communities? How can schools truly engage the local community and contribute to corporate social responsibility?

Conceptualising school/community engagement

Horizontal connectedness

As demonstrated in the Innovative Learning Environments (ILE) project, innovative schools are characterised by a high level of horizontal connectedness to their environment. In many innovative learning environments, inquiry- or problem-based learning are defined by real-world problems and carried out with real-world partners: universities and vocational training centres, the local business world, libraries, museums, theatres and sports clubs.

The early childhood development centre CENDI (Nuevo León, Mexico) is not a secluded institution withdrawn from “real life” but, on the contrary, draws significant content from the daily life of the community, its families, its neighbourhood stories, social and demographic developments, and traditions to enrich its educational programme.

The Culture Path programme (Finland) is for all elementary schools of the city and involving the community in students’ learning process. Students follow one “path” for each grade level, such as the “library path” or the “music path”. In so doing, students visit at least one local cultural institution or other cultural destination outside the school environment during the school year. These field trips are accompanied by various pre- and post-learning activities at school and each path is planned according to the requirements and the curriculum for the grade level in question.

Another kind of boundary crossed was that between participating in school activities on the one hand, and contributing to adult activities outside of school on the other. The students engaged much more seriously in measurements that were similar to those reported in the national media. For example, the students asked more insightful questions, and realised that conducting the measurements and documenting the results was surprisingly hard and messy (Liikkeelle! (On the Move!), Finland).

In the Enrichment Programmes, Rodica Primary School (Slovenia), students participate in voluntary activities such as helping nursery school teachers or helping in schools for children with special needs.

One of the unique features of the Dobbantó (Springboard) programme in Hungary is that by design the place of study is not just the classroom: there are occasions for learning outside the school that are part of the curriculum.

The Väätsa primary school took a slightly different approach by venturing on a project with regard to modern class room space solutions. Pupils from different classes and ages, architecture students, teachers, parents and entrepreneurs were collaborating on the design of the future learning environment. Two classrooms were refurbished as a result of the four-months project. In addition to product development and design competencies, young students thus also acquire entrepreneurship skills.

At the Yuille Park P-8 Community College (Victoria, Australia), the school and the community are very closely linked as part of the “Community Learning Hub”, which includes education, health and facilities for all members of the community. The building is designed so that the community facilities can be accessed from within or outside the school. Having access to these is particularly important for the community, as it is one of the most disadvantaged in Victoria and many parents are unemployed.

The school library at CEIP Andalucía, Seville (Spain) supports the publication of the school newspaper, Nevipens Andalucía. “Nevipens” means “news” in Romany. The idea of the newspaper is to get students closer to the press and make them assume the role of journalists. They prepare the different sections of a newspaper: leading articles, news stories on the school and the neighbourhood, culture (with a section on children’s literature), reading and library, citizenship, puzzles, dedications, etc. The newspaper helps to open communication and participation of families and other educational agents in the neighbourhood and develops linguistic communication and social citizenship skills in learners.

Learning ecosystems are multidimensional

The diversity of social contexts in which learning takes place points to the value of formal, non-formal and informal learning. Formal learning involves institutionalised, curriculum-based learning and teaching, such as learning which occurs within the education system, or workplace learning. Informal learning can take place within work, family or community contexts. It is not structured, and is more unintentional from the learner’s perspective. This type of learning happens, for instance, when children play. Non-formal learning is situated between formal and informal learning. It is structured and intentional, but not regulated, nor is it accredited or formally supported.

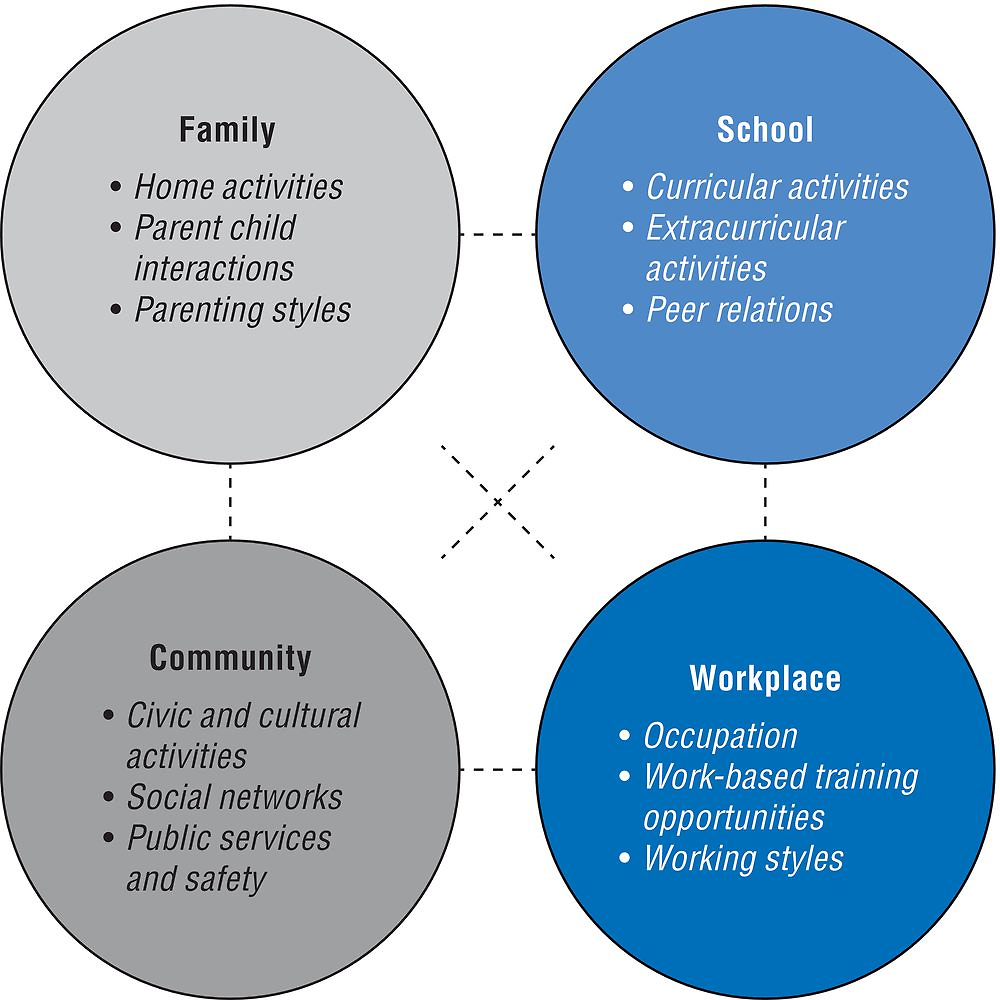

Hence, learning takes place in a variety of social settings, summarised in the current framework as the school, the family, the community and the workplace. Within each type of context we can distinguish a number of specific elements, with examples presented in Figure 3.1. Each context contributes to the development of cognitive, social and emotional skills, although their relative importance will change depending on an individual’s stage in life. For instance, parents are clearly crucial during infancy and early childhood, but school and the community become increasingly important as a child enters formal education and interacts with diverse social networks. The workplace, in turn, is a key learning context, particularly during late adolescence and (early) adulthood.

Source: OECD (2015a), Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

Dimensions of school/community engagement

Schools’ engagement with their external communities has conventionally been categorised into three domains (Watson, 2007):

-

First order engagement, reflecting schools’ standing as anchor institutions in their communities, with benefits arising from “just being there”.

-

Second order engagement based on entrepreneurial “third stream” trading relationships with different client groups: providing educational services to students and employers, and transferring knowledge-based expertise to industry, policy makers and public services.

-

Third order engagement involving schools in the life of the wider community through a variety of corporate social responsibility activities, ranging from outreach programmes with schools or community groups, to public lectures and cultural events, and opening campus facilities to public and outside users.

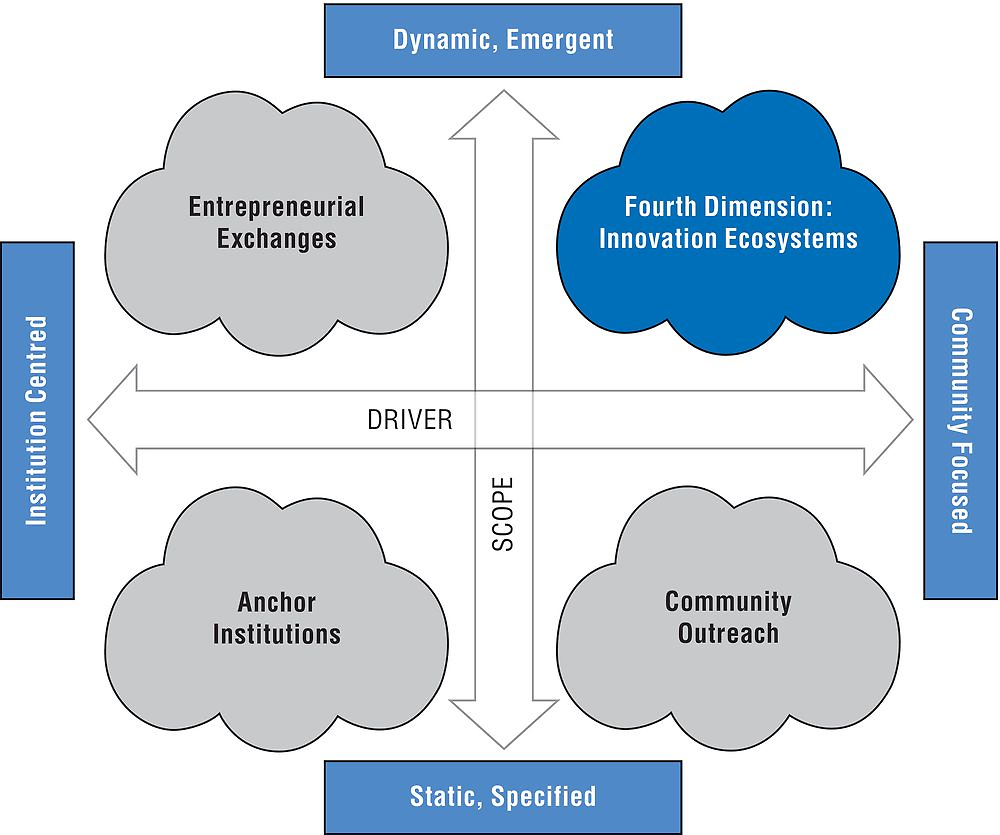

The diagram in Figure 3.2 illustrates schools’ engagement with their external communities along two axes – from provider-centred to community-focused, and from static and specific activities to dynamic and emergent solutions. This framework captures the three domains described here, while highlighting a fourth space, of open and collaborative partnerships through which schools and stakeholder communities work together to resolve shared needs and to create collective economic and social benefits. This mode of engagement goes well beyond institution-centred interactions, and has special resonance within the movement to develop local or regional responses to economic and social challenges (Stevenson, 2015).

Source: Stevenson and Boxall (2015), Communities of Talent: Universities in Local Learning and Innovation Ecosystems, www.paconsulting.com/insights/how-can-local-learning-partnerships-overcome-our-national-skills-deficit/.

Serving the community as learning

Extracurricular activities

In many school systems extracurricular activities provide opportunities to students to engage in the local community and to develop social and emotional skills, including civic engagement (OECD, 2015a). Extracurricular activities refer to those activities that complement core academic content, such as sports, clubs, student government associations, volunteer work and school chores. These activities provide students with real-life situations outside the classroom with the help of adult facilitators who can act as mentors.

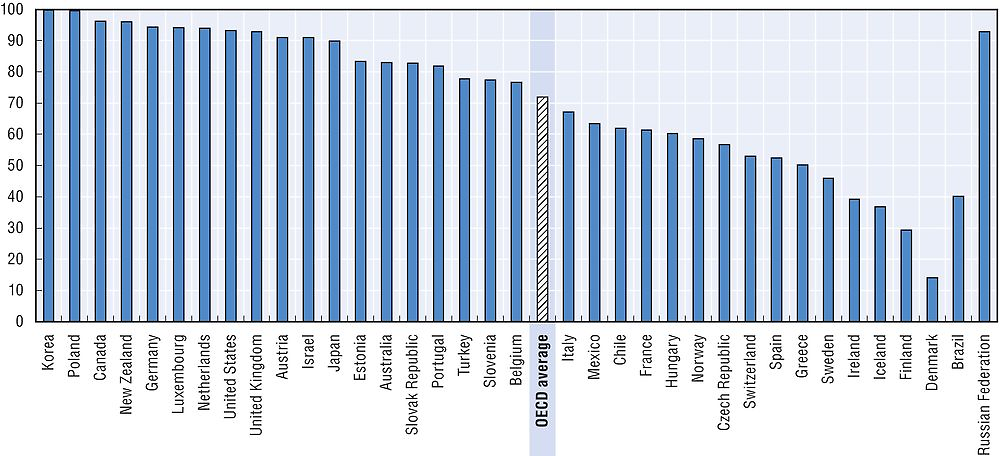

Extracurricular activities can be found in schools in all OECD countries and partner economies. According to the student background questionnaire of the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2012, 73% of 15-year-olds across OECD countries attended schools that organised volunteering or service activities (Figure 3.3). Similarly, 90% of them reported attending schools that supported extracurricular sports activities and more than 60% were in schools that supported mathematics competitions, art and theatre clubs. The availability of these activities, however, varies greatly across countries. This may reflect cross-country differences in the amount of resources that can be allocated to support extracurricular activities, including teachers’ time. It may also reflect differences in demand for such activities from parents. In some countries, certain extracurricular activities are organised by external associations.

Source: OECD (2015a), Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, based on PISA 2012 data.

Countries approach the organisation of extracurricular activities in schools in different ways (OECD, 2015a). In the majority of OECD countries, the organisation of extracurricular activities is not formally regulated. The implementation of these activities is often left to the discretion of local authorities or individual schools. The scope and nature of these activities therefore vary across, and within, countries. For example, local school administrations in Luxembourg define their own objectives for extracurricular activities without being bounded by national guidelines. While all schools in Luxembourg offer extracurricular activities, the range and content of extracurricular activities are only subject to the goals defined by the local school administrations. In France, an initiative launched in 2013 called “projet éducatif territorial” (PEDT) requires municipalities to organise extracurricular (sport, cultural and artistic) activities with financial support from the state government. This initiative aims to promote existing and new extracurricular activities and allow all students equal access to culture and sport. The PEDT is driven by the local authority while involving other stakeholders in the field of education, including national government institutions, associations, and cultural and sporting institutions.

In some countries, there are formal national guidelines for extracurricular activities that specify the hours and types of activities. For example, extracurricular activities are organised as an integral part of school education in Japan. The Japanese curriculum standards (the “Courses of Study”) for primary school students specifies minimum hours that schools should secure for four types of special activities: homeroom activities, student government, club activities and school events. For school events, the curriculum suggests organising specific activities such as school trips through which students can experience intensive group interactions and learn to be respectful of others. Besides these activities specified in the curriculum, most schools organise the cleaning of school facilities by students. This provides an opportunity for students to learn ways to collaborate with others and discipline themselves, while helping to maintain a clean learning environment. Korea also has similar guidelines on extracurricular activities, specifying time allocation for “creative experiential activities”, including self-regulated activities, club activities, voluntary activities and career education.

Whether there are formal regulations or not, schools and local education authorities have greater autonomy to plan extracurricular activities than curricular ones. Since schools are less constrained by the physical boundaries of classrooms (and, in some cases, schools), facilitators or mentors of extracurricular activities can flexibly mobilise real-life activities and scenarios to teach life skills that typically require strong social and emotional capability. Extracurricular activities often stimulate students to actively contribute to designing their own learning experience. They can also provide opportunities for schools to strengthen linkages with the community.

School-community partnerships can also provide additional opportunities for social and emotional learning by improving children’s access to extracurricular activities, and enhance their engagement in the community. Recently there has been a movement encouraging schools to actively reach out to stakeholders outside schools, including higher education, businesses and community groups, to enhance their educational programmes (OECD, 2015a).

In Denmark, a public school reform will be implemented from 2014 to enhance a school-community link that may improve extracurricular activities. With this reform, schools will be required to collaborate with the surrounding community, by involving local sports clubs, cultural centres, art and musical schools and various associations. The municipalities will also be required to commit to ensuring school-community co-operation.

In the United Kingdom, the Outward-Facing Schools programme at the Sinnott Foundation promotes schools’ links with communities and parents by providing fellowships to education practitioners in secondary schools. Their initiatives include schools’ active collaboration with local groups and businesses to create community work opportunities for students, such as volunteering at care homes and teaching at local primary schools.

Service-learning

Learning based on engaging with the local community is often conceptualised as service-learning. At its most basic level, academic service-learning is an experiential learning pedagogy in which education is delivered by engaging students in community service that is integrated with the learning objectives of core academic curricula (Furco, 2010). Academic service-learning is premised on providing students with contextualised learning experiences that are based on authentic, real-time situations in their communities. Using the community as a resource for learning, the primary goal of academic service-learning is to enhance students’ understanding of the broader value and utility of academic lessons within the traditional disciplines (e.g. science, mathematics, social studies, language arts and fine arts), all while engaging young people in social activities through which they derive and implement solutions to important community issues. Ideally, the community service the students perform helps them learn better how the academic concepts taught in the classroom can be applied to situations in their everyday lives. In this regard, academic service-learning seeks simultaneously to enhance students’ academic achievement and their civic development.

The literature on service-learning reveals that the community service activities in which students are engaged tackle a broad range of societal issues, including those concerning the environment, health, public safety, human needs, literacy and multiculturalism. In implementing service-learning activities, students can address a societal issue either through direct service (e.g. serving food at a homeless shelter) or indirect service (e.g. producing a research report that provides recommendations to the homeless shelter for improving its food distribution). Regardless of the type or focus of the service activity, academic service-learning is designed to help students apply their academic content knowledge to act on authentic and often complex societal issues.

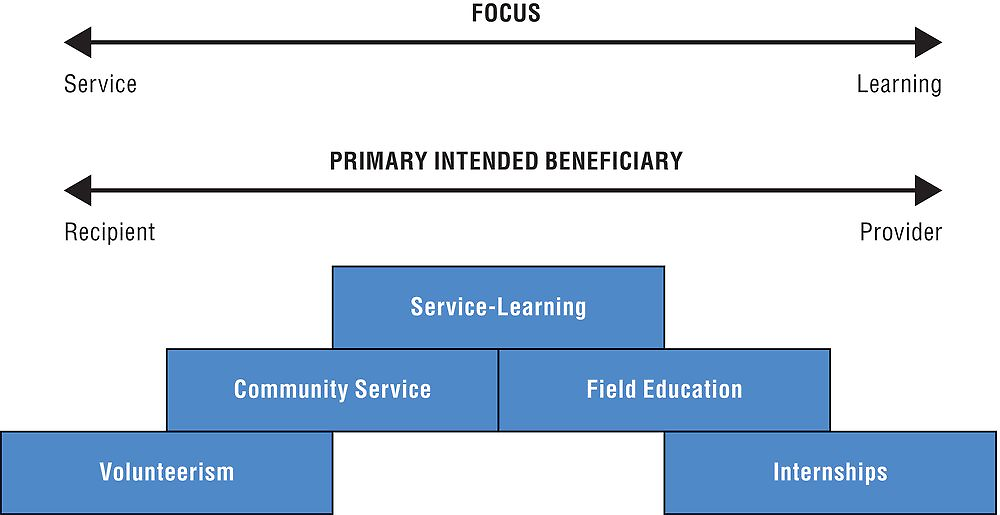

Although service-learning resembles other forms of community-based learning approaches, such as internships, field studies or volunteering, it is distinguished from these programmes by placing equal emphasis on both community service and academic learning, as well as its intention to benefit both the provider and recipient of the service (see Figure 3.4).

Source: Furco (2010), “The community as a resource for learning: An analysis of academic service-learning in primary and secondary education”, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-en.

In contrast to other forms of project-based learning, academic service-learning learning projects are purposefully community-focused and community-based, are usually conducted in partnership with members of the community, and, most importantly, are designed with a community need in mind. In essence, like a textbook or laboratory, the community becomes a resource for learning whereby the environs outside school offer students authentic learning opportunities to use their academic knowledge and skills to construct and implement solutions to real-life social problems in the local community or broader society.

The emphasis on community service and its use of the community as a resource for academic study intentionally shifts the role that students play in the learning process: they become producers rather than recipients of knowledge, active rather than passive learners, and providers rather than recipients of assistance. Unlike most other experiential learning approaches, academic service-learning places students in situations where they focus less on using resources for their own gain and more on acting as a resource for the benefit of others. Service-learning creates an educational atmosphere whereby learners confront real-life issues through community-engaged experiences that call on them to develop meaningful, academically-relevant actions that have real consequences for the community and themselves. Perhaps more than any other experiential or community-engaged learning pedagogy, academic service-learning has a strong civic dimension at its core. Its emphasis on community service establishes an inherent civic dimension that promotes social responsibility and citizenship among participants.

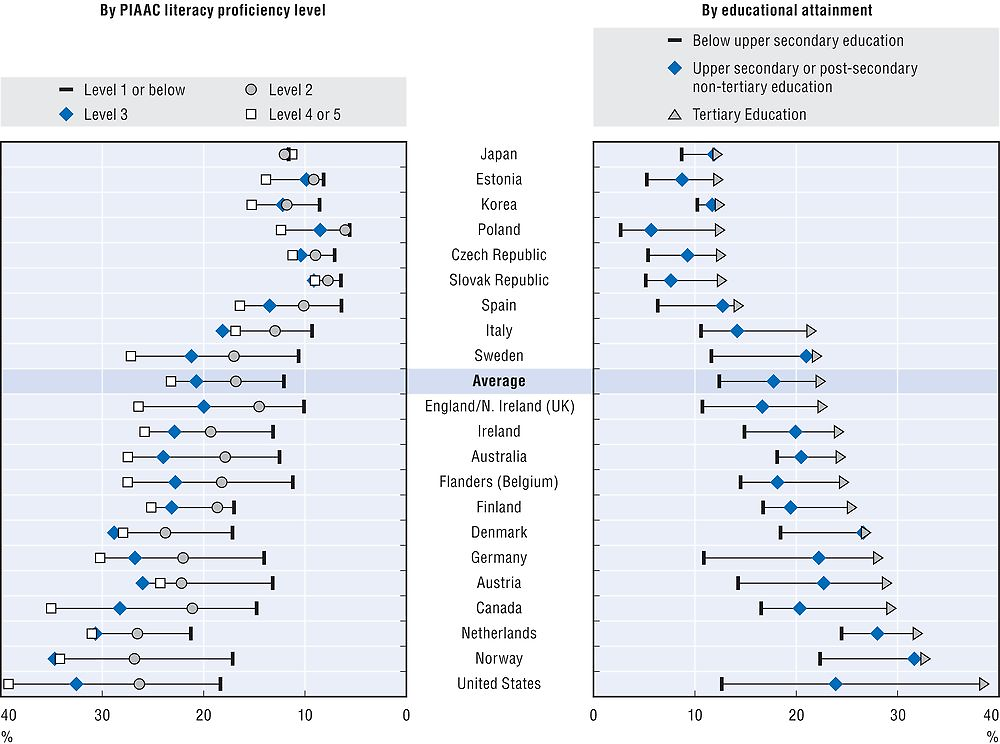

Learning to engage

Education, whether measured in terms of educational attainment or skills acquired, seem to have a strong impact on the civic and community engagement shown later in life. Figure 3.5, based on data of the OECD Survey of Adult Skills, shows the strength of the relationship, but also that the strength differs from country to country.

Source: OECD (2014), Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en.

Better-educated individuals on average are more likely to exhibit higher levels of civic and social engagement than the less educated. Also, better-educated parents are more likely to stimulate their children’s civic engagement, and an educated society tends to be more cohesive and have less crime. However, the precise mechanisms and pathways through which education promotes civic and social engagement remain unclear (Borgonovi and Miyamoto, 2010). Current OECD research is focusing on the role that specific personality traits and social and emotional skills play in the development of civic engagement and on how such skills can be developed and nurtured.

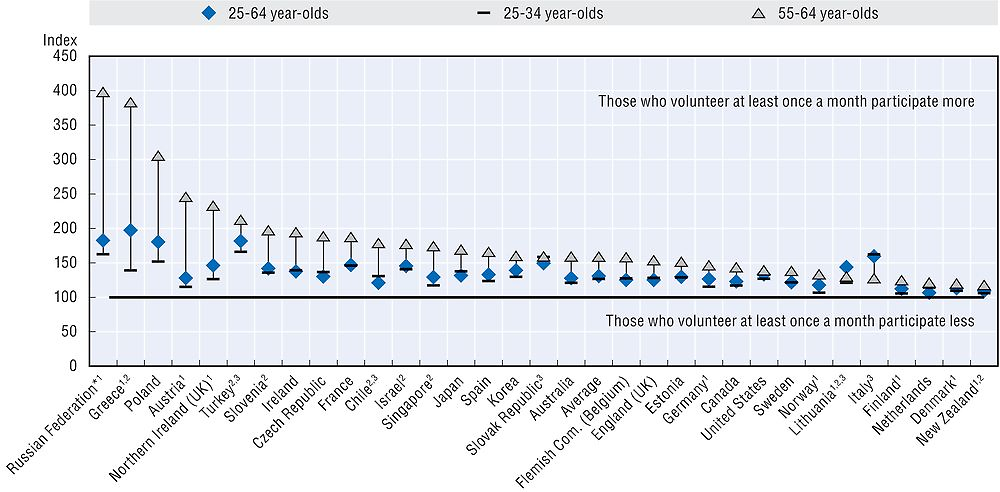

It is also very interesting to see, as shown in Figure 3.6, that volunteering and adult learning are closely related: people who volunteer, especially those in older age groups, are also relatively more likely to participate in various forms of formal and non-formal education. This adds further weight to the suggestion that learning adds to social capital and engagement in the local community.

Note: Values are missing for some countries and economies because there are too few observations to provide a reliable estimate.

1. The difference in participation in formal and/or non-formal education between unemployed 25-64 year-olds who volunteer and do not volunteer is not statistically significant at 5%.

2. Reference year is 2015; for all other countries and economies the reference year is 2012.

3. The difference in participation in formal and/or non-formal education between employed 25-64 year-olds who volunteer and do not volunteer is not statistically significant at 5%.

4. The difference in participation in formal and/or non-formal education between inactive 25-64 year-olds who volunteer and do not volunteer is not statistically significant at 5%.

Source: OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

Partnering with business and cultural bodies in the local community

The contemporary learning environment needs to develop strong connections with partners so as to extend its boundaries, resources and learning spaces. Partnerships should include local community bodies, businesses and cultural institutions, including museums and libraries. Creating wider partnerships should be a constant endeavour of the 21st century learning environment, overcoming the limitations of isolation in order to acquire the expertise, knowledge partners and synergies that come from working in partnership with others. Partners extend the educational experience, resources and sites for learning. Working with partners is a form of capital investment – in the social, intellectual and professional capital on which a thriving learning organisation depends. It generates benefits, both for the learning environments and learners themselves, and for the partners involved.

Corporate partners

A very important channel through which schools partner with and contribute to the local economy and community is their engagement with local business and industry. Some corporate partnerships may be the conventional community links of businesses helping through taking a funding or sponsorship role, but they may be much more about the learning that takes place as well.

The Lobdeburgschule (Thuringia, Germany) co-operates with many regional partners. This includes membership of “Berufsstart plus” (a project for the transition into vocational training) of the Eastern Thuringian Apprenticeship Network. Further co-operation partners are: Eine-Welt-Haus e.V., the car dealer Reichstein and Opitz GmbH, the Bildungswerk BAU Hessen-Thüringen (an educational institution), the JBZ (an education centre in Jena), DKJS Regionalstelle Thüringen (the regional office of the German Children and Youth Foundation), the University of Applied Science of Jena, the “Lobdeburgschule” e.V (registered association), the International AKademie INA gGmbH, the University of Berlin, the University of Jena, the Jenaer Antriebstechnik GmbH, the Kaufland Jena-Lobeda, Kindertagesstätte “Anne Frank” (day care centre), the KOMME e.V. of MEWA Textil-Service AG und Co. Jena OHG, the MoMoLo e.V., the vocational training centre for health and social issues, the Theaterhaus Jena gGmbH (theatre), the adult education centre Jena, and the vocational training centre in Jena-Göschwitz.

The connection between schools and the economic activity of the surrounding community is exemplified in the Instituto Agrícola Pascual Baburizza (Chile). The education of these students is guided by a group of farmers from the community, who are part of the school board and make sure that what is taught at the school is linked to real needs: “learning by doing and producing”. Internships must be done in real situations to train people and professionals – the students learn about employers’ demands and it is expected they will continue to develop throughout their professional lives. Everything that students learn in internships must have a practical application. All of this is done in the countryside, the “big classroom”.

Cultural partners

Cultural partnerships can be very useful in extending the boundaries of the learning environment beyond formal school provision, and in offering access to arts materials and experiences directly. As in the case of Fiskars, artists and craftspeople become part of the educational workforce, too.

The Fiskars Elementary School (Finland) may be defined as an enlarged learning environment. The basis for the model and its central working method are the workshops that are developed, and organised in co-operation with such actors as the Artisans, Designers and Artists Co-operative of the village of Fiskars.

Thanks to the cultural offer of Sant Sadurní D’Anoia and other nearby towns, all students at Instituto Escuela Jacint Verdaguer (Spain) annually attend a performance of each artistic discipline – music, dance and theatre – visit exhibitions and have similar cultural experiences.

The Culture Path programme (Finland) has been implemented in close collaboration with the city’s cultural institutions, schools and teachers, as well as other relevant interest groups such as the Eastern Regional Center for Dance, Children’s Cultural Center Lastu, many cultural associations and private culture activists. The project aims to produce a service that is easily accessible, and which would enable both students and teachers to experience culture and art as a source of learning and enjoyment. It has nine paths – library, art, museum, media, environment, dance, music, theatre and the K-9 card – one for each grade level. With the K-9 card, a 9th grader can use the city’s cultural services for free, or at minimal cost, after “trekking” for eight years on the Culture Path.

These, and many other examples of partnerships with museums, galleries and theatres, but also with radio and media companies, extend the materials and the means of learning as well as the range of professionals involved.

Innovating the space of learning

Networking

So far, we have discussed the relationships between schools and their surrounding communities in terms of “serving the community”, “outreach” and “partnerships”. From this perspective the distinction between the formal education environment of the school and the surrounding informal and non-formal opportunities for learning is still very powerful and limits the degree of integration of the school with its environment. In more innovative arrangements, the mixing of formal with informal and non-formal learning becomes more pronounced. Broadening the institutional base beyond schools through service-learning, diverse non-formal and informal learning opportunities on line and in communities, and establishing “hybrid” formal/non-formal programmes are all part of creating dynamic learning systems.

A distinguishing feature of the New Zealand LCN strategy is the deliberate positioning of students at the forefront of the network activity with teachers and families closely involved. This in particular brings in students who are M¯aori, Pasifiika or have special educational needs and whose achievements have not reached national standards. It also involves the students’ families/wh¯anau and teaching professionals who discuss how to move learners along the continuum from passive to active, which often calls for reconsideration of the nature of professional authority in the facilitation of students’ learning. Some networks are engaging students and families as co-investigators in the readjustment process while others are more cautious, with teachers and leaders still firmly at the forefront. Priority students and their families/wh¯anau are inherently capable and, as agents of their own cultures, are articulate in sharing with teachers and leaders their knowledge about the way they learn and what they may need to change.

In Thuringia (Germany), the start-up project Development of Innovative Learning Environments recognises that since education is not only accomplished in formal contexts, the understanding of innovative learning environments goes well beyond educational institutions. It also opens up to family (parents and legal guardians), the wider natural environment, and the larger community and regional environment. There is a close co-operation with the Thuringian initiative “nelecom“ (new learning culture in communes).

Such examples and others evolve into networked arrangements as emerging learning ecosystems around four different models (OECD, 2015b):

-

school chains, which are groups of schools sharing a mission and acting as a micro system

-

locally embedded hubs, responding through innovation to particular needs in a community or locality

-

innovation zones, centrally facilitated innovation strategies in, for example, a city creating a network of schools, system leaders and broader education partners

-

looser networks and coalitions, socialising new ways of working among professionals and school leaders.

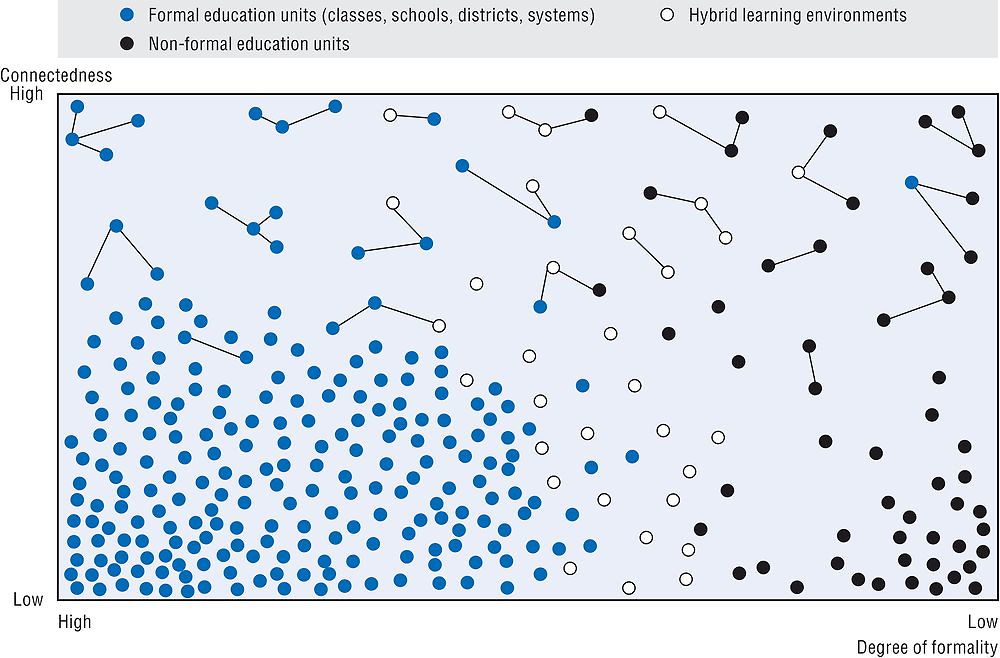

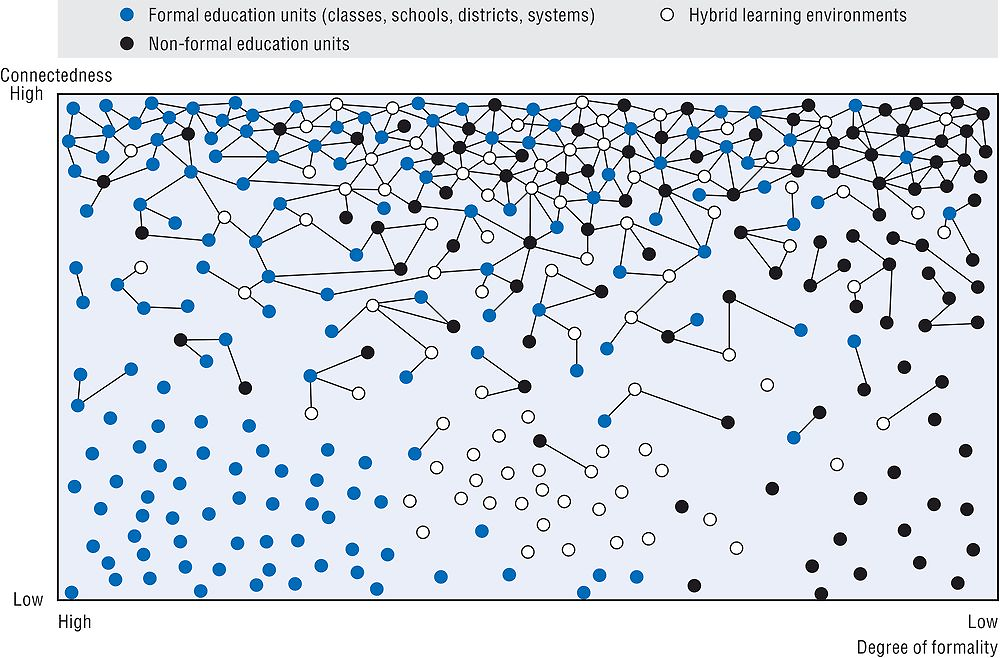

Figure 3.7 and Figure 3.8 represent two different systems, including formal, non-formal and hybrid forms, and units of education (OECD, 2015b). Moving from top to bottom, there are more connections among formal units, which can be clusters and chains of schools. Moving from left to right, from the formal to the non-formal education providers, there are more connections among themselves or with hybrid partners or partners from the non-formal sector. The hybrids might combine work and learning, sports and learning, or community service and formal learning.

Source: OECD (2015b), Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264245914-en.

Source: OECD (2015b), Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264245914-en.

Figure 3.7 represents a hypothetical weakly networked meta learning system. There are few networks and cross-school communities, and very little evidence of hybrids. While there are some non-formal programmes and providers, as these are responding to demand for alternatives to schools there is little connection between them and the formal system.

The networked learning system (Figure 3.8) implies a significant increase in the number of groups, organisations and organisms devoted to learning as units, not only working by themselves as before but connecting up in a flourishing range of collaborative groupings. The networked system shows the learning space is fuller horizontally. There are also more non-formal providers and programmes, encouraged by the dynamism of learning and the opportunities opened up by technology and by demand. Some of these form networks totally outside the formal system but often the formal and the non-formal come together and fill the “hybrid” space in the middle. There are also more networks and communities of practice created in the formal system as it encourages clusters, networks and collaboration among districts, schools, classes and teachers as well.

Innovative learning ecosystems constantly change, with groupings forming and disbanding all the time; as they are organic, they are less predictable. In being less defined by acquired position and regulated status, they rely critically on relationships and connectivity whose importance grows. Especially important are knowledge and ideas as connectors. Increasingly, but not exclusively, they depend on communication technologies.

Networks can be singled out, not because they are by themselves always effective or innovative but because they offer the connections through which knowledge passes and ultimately collaborative action takes place. They are particularly valued for their capacity to bring diverse perspectives to the table, whether from inside or outside government, clarify problems, facilitate co-ordination and actually implement change. Effective networks can cut through complex hierarchies and generate new solutions to intractable and often challenging local problems whether in preventative health, welfare issues such as social housing and support for vulnerable youth, energy solutions, the environment, or in restructuring regional economies. Complex issues put a premium on the capacity of leaders and organisations to take account of a multitude of interdependencies and work across traditional boundaries. Well-functioning collaborative networks add high value and can enable the whole to become more than the sum of its parts.

Horizontal accountability

A networking ecosystem fundamentally changes the relationships between schools (and other learning organisations) and their main stakeholders and also alters the steering and accountability mechanisms around them.

In a context of increasing school autonomy and decentralisation, many education systems have reinforced instruments of school accountability. This is based on the assumption that holding schools accountable for attaining high standards will, in fact, motivate schools to improve their quality. Thus, the following purposes for school accountability can be distinguished:

-

legitimation through compliance with laws and regulations

-

accounting for the quality of services provided, in terms of quality of education (effectiveness), value for money (efficiency), equity or access

-

improving the quality of services provided, in terms of quality of education (effectiveness), value for money (efficiency), equity or access.

Hooge, Burns and Wilkoszewski (2012) distinguish between two main types of accountability mechanisms: vertical and horizontal. Vertical accountability is top-down and hierarchical. It enforces compliance with laws and regulation and/or holds schools accountable for the quality of education they provide. Horizontal accountability presupposes non-hierarchical relationships. It is directed at how schools and teachers conduct their profession and/or how schools and teachers provide multiple stakeholders with insight into their educational processes, decision making, implementation and results. Each of the two types of accountability is further divided into two subsections, as shown in Figure 3.9.

According to Hooge, Burns and Wilkoszewski (2012) there is a gradual shift taking place in the governance of education from the vertical to the horizontal forms of accountability. Horizontal elements in education governance have had a relatively long tradition in a range of OECD countries. School boards or councils comprised of elected, voluntary members have sought to integrate the voices of parents into the governing process. However, many of these bodies do not include wider groups of stakeholders. In some countries, however, notably Denmark, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, there has recently been a trend to move towards more profound multiple school accountability designs. Defined as a process involving students, parents, communities and other stakeholders in formulating strategies, decision making and evaluation for education, multiple school accountability aims to provide:

-

legitimation of the strategy and decision making of the school (is the school doing the right things?)

-

legitimation of the quality of services provided (is the school doing things well?)

-

improvement of the quality of services provided.

A form of horizontal accountability, multiple accountability means that schools are accountable to students and their parents, to members of the community, and to the community as a whole for multiple aspects of schooling, based on various information sources. Multiple accountability aims to increase legitimacy and trust from the local community through the processes of learning and feedback that it entails. It requires that schools work closely with different stakeholders, supporters and constituents in their environment in order to:

-

help them learn about their rights and duties, requirements, desires and expectations concerning education

-

establish a relationship (by negotiating, collaborating and/or involving them)

-

obtain support for school policies, strategy, decisions and practices

-

be held accountable by them.

The practice of multiple accountability has yet to come to fruition in education, and the amount of available research on this topic is modest. Based on theory and experience from other sectors however, some lessons can be learned to make multiple school accountability work:

-

It is important to identify the right stakeholders. The process of stakeholder identification can be heavily influenced by “stakeholder salience”, that is, the ability of stakeholders to attract schools’ attention, depending on their power, legitimacy and urgency with regards to the school. In order to ensure that the identification of stakeholders is not limited to those most salient, schools must make efforts to involve less powerful or inactive stakeholders. Being less powerful or inactive does not mean that these stakeholders are not relevant to the school. On the contrary, these are often the very stakeholders for whom the school aims to add value; therefore, schools need them.

-

Build stakeholder capacity. This is particularly important while establishing accountability relationships with weaker stakeholders who might not have the requisite knowledge and language to play the role holding schools to account and, therefore, may inadvertently be excluded from accountability processes. Avoiding apathy and “consultation fatigue” is key because they weaken the effectiveness of the process, and ultimately the strength of this approach is determined by its weakest accountees. Schools can involve and activate their stakeholders by being inviting, by structuring participation and accountability processes, and by motivating and empowering them.

-

Self evaluation that provides real insight into schools’ quality and processes is needed to make multiple accountability work. Proper school self evaluation requires “assessment literacy” from school leaders as well as from teachers and other professional staff. The work of school leaders is crucial here: they must empower staff to be involved and open to parents and members of the local community and to be held accountable by them, and they must create the effective environments by building bridges between teachers and educational staff and external accountability demands. Autonomy and a (governance) environment that provides support foster this work of school leaders.

References

Borgonovi, F. and K. Miyamoto (2010), “Education and civic and social engagement”, in OECD, Improving Health and Social Cohesion through Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086319-5-en.

Furco, A. (2010), “The community as a resource for learning: An analysis of academic service-learning in primary and secondary education”, in H. Dumont, D. Istance and F. Benavides (eds.), The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-en.

Hooge, E., T. Burns and H. Wilkoszewski (2012), “Looking beyond the numbers: Stakeholders and multiple school accountability”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 85, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5k91dl7ct6q6-en.

OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en

OECD (2015a), Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

OECD (2015b), Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264245914-en.

OECD (2014), Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en.

OECD (2013), Innovative Learning Environments, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264203488-en.

OECD (2010), Learning for Jobs. Synthesis Report of the OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264087460-en.

Stevenson, M. and M. Boxall (2015), Communities of Talent: Universities in Local Learning and Innovation Ecosystems, PA Consulting, www.paconsulting.com/insights/how-can-local-learning-partnerships-overcome-our-national-skills-deficit/, accessed 31 July 2017.

Watson, D. (2007), Managing Civic and Community Engagement, McGraw Hill/Open University Press.

Note

← 1. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.