Chapter 4. Low-skilled adults in post-secondary vocational education and training (VET) in Australia

Some post-secondary vocational education and training (VET) students lack uppersecondary qualifications. Such students are much more likely to perform poorly in basic skills than their peers with higher levels of education. Women are also over-represented among students with low basic numeracy and literacy skills. These findings show that initiatives targeting specific categories of post-secondary VET students, such as those with few qualifications and students in specific fields of study could be particularly effective. This chapter also discusses the importance of addressing underperformance in basic skills as a part of post-secondary VET studies.1

Characteristics of low-skilled post-secondary VET graduates

Some post-secondary VET graduates lack basic skills

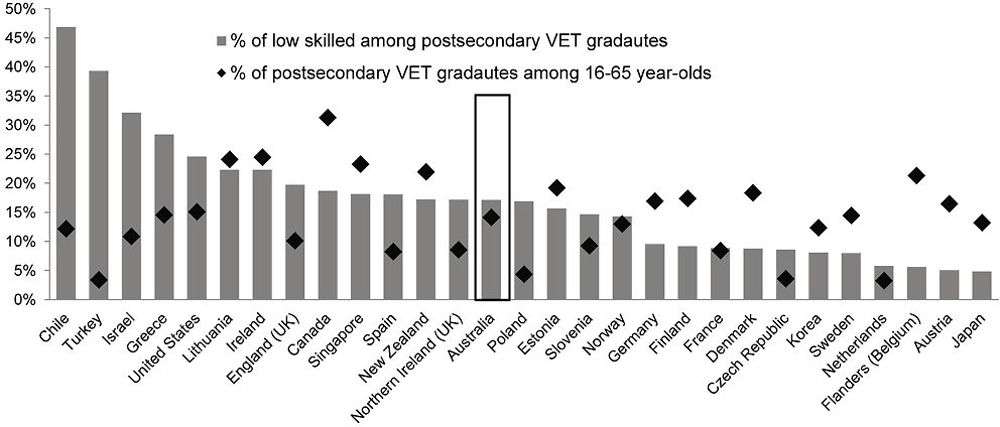

In Australia, around 16% of adults (16-65 year-olds) hold post-secondary qualifications, most of which are vocational (see Table 1.1 for classification of VET programmes). Some 15% of all post-secondary VET graduates lack basic numeracy or literacy skills (see Figure 4.1). While the percentage of post-secondary VET graduates with low skills in Australia is similar to the average of participating countries, it is above the share of low-skilled adults with equivalent qualifications in some other countries, such as Austria, Denmark, Germany and Sweden. Poor numeracy skills are more common among post-secondary VET graduates in Australia than poor literacy.

Note: Results for the Slovak Republic and Italy were not shown due to a small sample size. Foreign qualifications were excluded.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2016a), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

Some post-secondary VET students lack basic skills

Around 17% of current post-secondary VET students have low basic skills (literacy or numeracy) (see Figure A A.3 in Annex A), with low numeracy being more common than low literacy. There is no difference in the share of low basic skills among students in Certificate IV and those studying for a higher post-secondary level qualification. The poor performance of these students shows that some individuals lack basic skills when they start a post-secondary VET programme. Some of these students may drop out or fail to graduate, others may improve their skills during their post-secondary studies. A large share of poorly performing recent graduates shows that for many students, the problem of basic skills is not resolved at the point of graduation (see Figure A A.3 in Annex A). Institutions providing these qualifications therefore do not sufficiently, or effectively, focus on remediating basic skills shortages among their students.

Recently, the Australian Government has introduced two initiatives to address these challenges. Foundation Skills Assessment Tool (FSAT), interactive online tool, was developed to identify and measure an individual’s foundation skill levels. It can help training providers to address the individual needs of students. Recent changes to the Training and Education Training Package resulted in the inclusion of adult language, literacy and numeracy skills (the LLN unit) in the core units for the Certificate IV. The inclusion of the LLN unit in the Certificate IV was designed to provide VET practitioners with a greater understanding of the foundation skills required in their industry sectors.

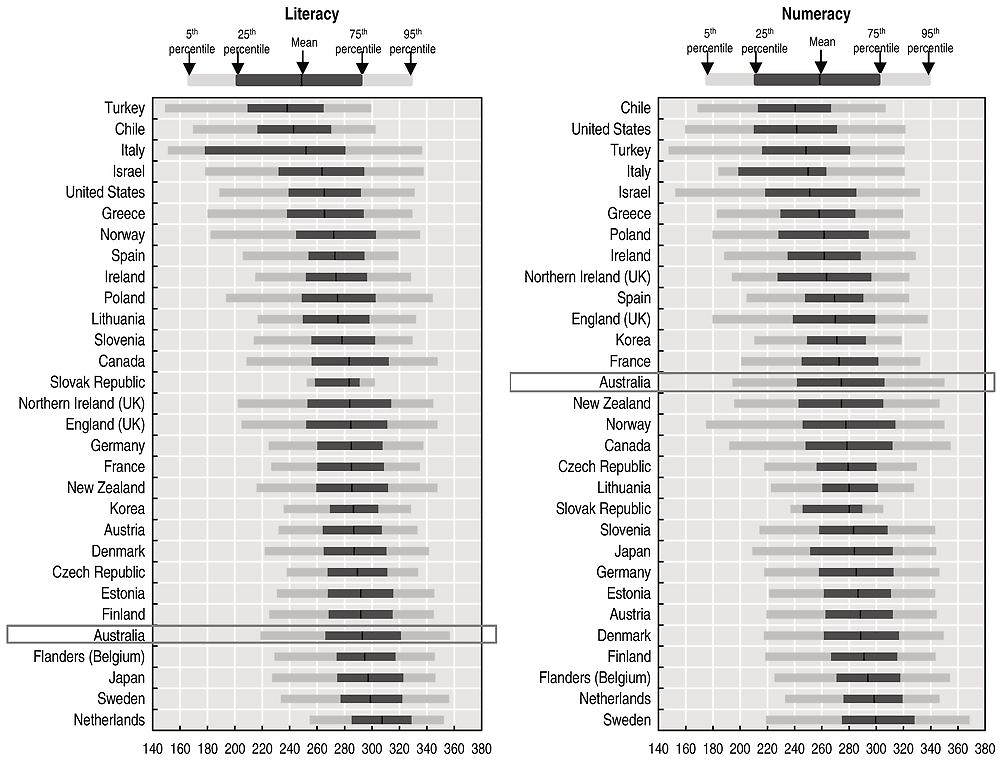

There are large variations in the distribution of basic skills among current students

A relatively large gap between the best and the worst performers both in literacy and numeracy may indicate large variations in basic skills distribution across regions, institutions or fields of study (as indicated by the length of the bar in Figure 4.2). This is consistent with findings of a recent OECD report (OECD, 2016) that points to the varying quality of education and training among VET providers.

The consequences of being a low-skilled post-secondary VET graduate

While the majority of low-skilled graduates work, their situation in the labour market is more precarious

Some 72% of low-skilled post-secondary VET graduates were employed in 2012 (see Figure 4.3). While the employment rate of low-skilled graduates is relatively high, it is still 12 percentage points below the employment rate of all graduates with similar qualifications. The relatively high employment rate in this population may be explained by job-specific skills acquired in these programmes that are not tested in the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) but rewarded in the labour market. It may also reflect a strong signalling value of post-secondary VET qualification, whereby employers use qualifications as signal of productivity and skills, independently of actual skills, or the fact that in 2012, demand for labour was high, with the overall unemployment rate around 5%. The situation of low-skilled adults in the labour market remains more precarious that that of highly skilled individuals, across all levels of educational attainment. For example, in Australia, low-skilled adults are more likely to work without a contract compared to adults with stronger skills. Post-secondary VET graduates with low skills could therefore be more vulnerable than their better skilled peers when economic and employment prospects worsen.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2016a), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2016a), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

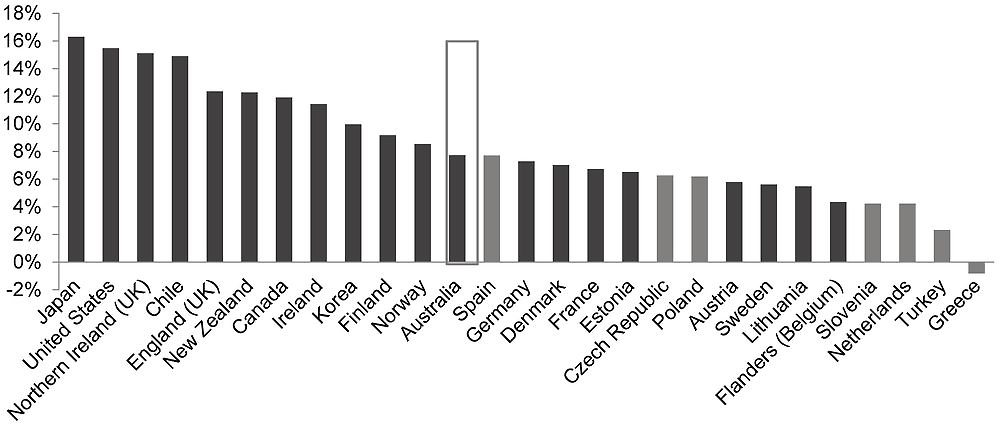

Earnings of post-secondary VET graduates are associated with basic skills

In Australia, as in other countries, skills have a positive impact on wages. These findings also hold if the analysis is restricted only to those who graduated from post-secondary VET programmes, independently of gender, migration status, parental education, native language and age. This means that two identical people in terms of gender, migration status, native language and parental education, but with different levels of skills, will have different earnings. In Australia, a 50-point increase in numeracy skills, the number of points separating two different levels on numeracy scale, is associated with a 7% change in earnings (see Figure 4.4). Improvement in basic skills among current students may therefore increase returns to post-secondary VET qualifications. Reinforcing basic skills among post-secondary VET students and graduates would also have other advantages, such as reducing dropout from programmes and increasing the capacity of graduates to enter more highly skilled jobs and pursue further training and career development.

The majority of low-skilled post-secondary VET graduates are in occupations requiring mid or high-level skills

In comparison to highly skilled post-secondary VET graduates, those with low skills are less likely to work in jobs demanding high-level skills, such as managers and technicians, and more likely to work in occupations relying on mid-level skills, such as clerks, service workers and shop and market sales workers (for distribution of post-secondary VET graduates by skills and sectors see Figure A A.4 in Annex A). Nonetheless, 35% of lowskilled post-secondary VET graduates work in jobs requiring high-level skills. This may be due to skills other than numeracy and literacy that make low skilled post-secondary VET graduates suitable for these jobs. However, the high proportion of low-skilled individuals in these occupations could also be a sign of mismatch.

Note: Statistically significant results are marked in a darker tone. Adjusted for gender, migration status, native language and parental education.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD (2016a), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (Database 2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/site/piaac/publicdataandanalysis.htm.

Recommendations: How to address the challenge of low basic skills in postsecondary VET

The remaining part of this section provides policy pointers on how to improve basic skills provision in post-secondary VET, while recognising that:

-

Low basic skills among current students result from a mix of factors, such as previous education and labour market experience, use of skills at home, and personal and cohort characteristics.

-

The skills of post-secondary VET graduates evolve after graduation, depending on the use of their skills in a work and out-of-work context.

Policy pointer 1: Identify students at risk of low basic skills and provide them with targeted initiatives

Australian post-secondary VET is inclusive and caters to a very diverse population: those preparing for a first career, those updating their skills while working and those who seek to validate skills acquired outside the education system. Post-secondary VET students also have very different educational experiences: 12 % have a qualification below upper-secondary level, 18% hold a university degree, nearly 40% have completed upper-secondary education, 24% already have a post-secondary qualification, and 6% studied abroad. While the inclusiveness of the post-secondary VET system is its strength, addressing the needs of a very diverse population can be challenging. An analysis of the association between age, gender, migration status, previous qualification and numeracy skills of post-secondary VET students shows that students whose highest qualification is below upper-secondary or upper-secondary VET are much more likely to perform poorly in numeracy than their peers with higher levels of education. Women are also over-represented among students with low basic numeracy skills. This could be due to the fact that women self-select themselves to the areas of study with lower requirements in numeracy. Being a migrant is not linked to numeracy performance. Age is positively associated with numeracy skills, but only among students with lower levels of education. This means that adults with low qualifications, and presumably low basic skills, might upgrade their skills after graduation through work. The findings of this analysis show that initiatives targeting specific categories of students, such as those with low and VET qualifications, and students in specific fields of study, could be particularly effective.

Policy pointer 2: Ensure post-secondary VET is good quality, with basic skills a quality criteria

Recent reforms have established a market in the provision of post-secondary VET, with public and private providers competing for public money. These reforms aimed to increase the number of VET participants, improve access to post-secondary education, and boost student choice. However, the reform also created a system that is complex and difficult to understand for students, and where quality varies greatly across providers. In the reporting year 2015-16, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) found that in initial audit 82% of registered training providers did not fully comply with their standard of quality in training and assessment. After the rectification period which follows the initial audit report, 29% of training providers still did not fully comply. (Australian Skills Quality Authority, 2016). There is anecdotal evidence that private providers receiving public funding collude with students by offering them gifts and shopping vouchers for signing up for courses (e.g. Mitchell, 2016). A recent report by the Senate recognises the problems of abuse and low quality (Australian Senate, 2015) and recommends giving a larger role to ASQA to control and take action against training providers offering inadequate training to their students. Students with poor basic skills might be particularly concerned by the varying quality of provision across providers. Some institutions receiving per student funding may accept students with poor basic skills, with no intention or capacity to address this challenge.

Basic skills should be a quality criteria

While not all post-secondary VET jobs rely to the same extent on strong literacy or numeracy skills, it can be assumed that all require at least basic literacy and numeracy. Basic numeracy and literacy should therefore underpin all post-secondary VET qualifications. To address the quality challenge in VET, the Australian Government has recently revised standards for training providers (Registered Training Organisations). According to the new standards, the provider defines the amount of training regarding the existing skills, knowledge and experience of the learner. The provider should also have the capacity to provide educational and support services to the student to meet his or her needs (Australian Government, 2015). These standards could be interpreted in a way that strengthens the focus of VET providers on basic skills.

Example of successful initiatives

Box 4.1 describes the initiatives introduced in the United States to respond to the quality problem in post-secondary VET.

The United States was facing, to some extent, similar challenges to Australia in post-secondary VET: quality in post-secondary VET was varied, private providers competed with public institutions for students and for federal money distributed through federal student loans, and students did not have access to full and accurate information on post-secondary VET choices and their outcomes. As a result, many students, typically from disadvantaged backgrounds, ended up with huge debts and education and training that was irrelevant to labour market needs. In response, the United States Department of Education established more stringent rules on VET post-secondary providers accessing federal dollars, making providers accountable for their labour market outcomes. For example the typical graduate’s estimated annual loan must not exceed 20% of their discretionary income (what is left after basic necessities such as food and housing have been paid for) or 8% of total earnings. “Based on available data, the Department estimates that about 1 400 programmes serving 840 000 students – of whom 99% are at for-profit institutions – would not pass the accountability standards.” (United States Department of Education, 2016).

An OECD report (Kuczera and Field, 2013) focusing on post-secondary VET in the United States lists a number of characteristics of good quality VET programmes that should be assured during the quality check. Similar criteria could be applied in Australia.

Regarding basic skills, a good quality post-secondary VET programme should have:

-

Curricula reflecting the immediate requirements of employers, but also involving sufficient general and transferable skills to support career development; credentials with clear labour market recognition in the relevant industry sector.

-

Arrangements designed to provide targeted help to students who can benefit from the programme but have particular needs, such as numeracy and literacy weaknesses. (Kuczera and Field, 2013: 59).

Source: Kuczera, M. and S. Field (2013), A Skills beyond School Review of the United States, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264202153-en; US Department of Education (2015), Fact Sheet: Obama Administration Increases Accountability for LowPerforming ForProfit Institutions, www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/fact-sheet-obama-administration-increases-accountability-low-performing-profit-institutions

Pointer 3: Encourage providers of post-secondary VET to address underperformance in basic skills

Remediating basic skills is difficult, but not impossible, as shown by the US example. In the United States, community colleges (public providers of post-secondary VET programmes) play an important role in providing qualifications for young adults, and in most states, access to the system is relatively easy and affordable, similar to Australia. Basic skills weaknesses among entrants are very common. To address this challenge, most public institutions provide remedial courses, although relatively few students referred for remediation end up completing the course. Faced with the failure of mainstream remedial education, US colleges and states have experimented with alternative, more targeted, but often also more expensive interventions, some of which have been successful. Providers of post-secondary VET qualifications in Australia, therefore, should be encouraged to address underperformance in basic skills more vigorously and effectively. For example, progress in basic skills made by students in post-secondary VET programmes could be one of the criteria of government funding for institutions offering the corresponding qualifications.

Examples of successful initiatives

Box 4.2 highlights an example of a funding incentive introduced in the state of Washington (United States) to improve college completion. While this initiative focuses primarily on student progression through the programme, similar incentives could be introduced to tackle low basic skills. It also describes the I-BEST model that provides basic skills in the context of learning vocational subjects.

The Student Achievement Initiative (SAI) is a performance funding system for all community and technical colleges. It includes certificate and associate degrees (one and two-year programmes), apprenticeship retraining for workers, and a programme for adults without a high school diploma. Institutions are rewarded with additional funds if they record a positive change in the number of students that move from remedial to credit courses, complete specific credits, and successfully complete the degree. Colleges are evaluated based on the progress made relative to their own prior performance. As one official document states: “there are no targets, colleges compete with themselves rather than each other” (SBCTC, 2013). SAI does not affect the regular formula by which the state distributes funds among institutions.

The model tracks student progress over time, from basic skills courses to the completion of a degree. It encourages institutions to measure the impact of tools designed to improve student progression. On this basis, institutions can identify and adjust their practices genuinely contributing to student progression. This focus on student progression and completion has increased attention on basic skills and remedial education, and had also led to stronger investment in student services (Jenkins et al., 2009).

The evidence collected through systematic evaluation of SAI shows that the number of students in technical and community colleges reaching crucial progression points (momentum points) has been growing since its introduction. In particular, more students perform better in basic skills and are college ready. Over the same period, more students are enrolled in community and technical colleges, which contributes to the higher number of students progressing through the system. However, the achievement gains grew at a much faster rate than the number of students enrolled, which implies that better student achievement explains an important part of this improvement (SBCTC, 2013). There is also little evidence that colleges serving more at-risk, low-income students are penalised by the SAI funding (Belfield, 2012). The growth in student performance halted in 2011, which could be related to funding cuts in post-secondary education.

I-BEST (the Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training) is an innovative blend of basic skills with vocational education and training. Often too few students in adult basic skills programmes upgrade their skills by transferring to post-secondary education. I-BEST was developed to improve entry rates to post-secondary career and technical education (CTE) in response to this challenge. Around 2% of basic skills students participated in I-BEST between 2006 and 2008 (Wachen et al., 2010). An I-BEST programme combines basic skills teaching and professional training. Occupational training yields college credits that contribute to a certificate degree. These CTE courses can only be provided in occupations in demand in the labour market and leading to well-paid jobs (Wachen et al., 2010). Combining basic skills with CTE content is facilitated by the availability of both types of programme at community and technical colleges (I-BEST programmes are available in every community and technical college in Washington State) (WTECB, 2013a). Individuals must score below a certain threshold on an adult skill test and qualify for adult basic education to participate in an I-BEST programme. I-BEST students tend to perform better than non-participants and are more likely to have a high school or equivalent qualification.

In the I-BEST programme, a teacher of basic skills and a teacher of professional-technical subject jointly instruct in the same classroom with at least a 50% overlap of instructional time (SBCTC, 2012). This increases the cost of provision, and the state therefore funds I-BEST students at 1.75 times the normal per capita funding rate. From an individual point of view, I-BEST programmes are more expensive than adult basic education as students pay for the college-level portion of the I BEST programme. This may prevent some adults from participating, as many I-BEST students are from low-income families and cannot afford tuition in college-level classes (Wachen et al., 2010). Students can receive financial support from federal (Pell grant) and state sources (state need grant and opportunity grant), but as reported by Wachen et al., (2010), many students interested in I-BEST do not qualify for this aid. Proving eligibility for the financial aid can sometimes be complicated and deter students from applying.

A few studies measuring the impact of I-BEST found that I-BEST students earn more credits and are more likely to complete a degree than a comparable group of basic skill students not participating in the programme. Evidence on the link between participation in I-BEST and earnings is less conclusive, although this might be due to changing economic conditions and the United States and Washington State economy entering recession (Jenkins et al., 2010).

Source: SBCTC (2012), Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training (I-BEST), www.sbctc.edu/colleges-staff/programs-services/i-best/; Belfield C. (2012), “Washington State Student Achievement Initiative: Achievement Points Analysis for Academic Years 2007-2011”, CCRC-HELP Student Achievement Initiative Policy Study; Jenkins D., T. Ellwein and K. Boswell (2009), Formative Evaluation of the Student Achievement Initiative Learning Year, Report to the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges and College Spark Washington, CCRC; Wachen J., D. Jenkins and M. Van Noy (2010), How I-BEST Works: Findings from a Field Study of Washington State’s Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training Program, CCRC, New York; Jenkins D., M. Zeidenberg and G. Kienzl (2010), “Educational outcomes of I-BEST, Washington State community and technical college system's integrated basic education and skills training program: Findings from a multivariate analysis”, Working Paper No. 16, CCRC in Kuczera M. and S. Field (2013), Skills beyond School Review of the United States, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264202153-en.

References

Australian Government (2015), Standards for Registered Training Organisations (RTOs) 2015, Federal Register of Legislation, www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2014L01377.

Australian Government, Department of Education and Training (2017), Foundation Skills Assessment Tool, www.education.gov.au/foundation-skills-assessment-tool (accessed 1 April 2017).

Australian Senate (2015), Getting Our Money’s Worth: The Operation, Regulation and Funding of Private Vocational Education and Training (VET) Providers in Australia, Parliament House, Canberra. www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A70322.

Australian Skills Quality Authority (2016), Australian Skills Quality Authority. Annual Report 2015–16, Commonwealth of Australia, www.asqa.gov.au/sites/g/files/net2166/f/ASQA_Annual_Report_2015-16.pdf.

Belfield C. (2012), “Washington State Student Achievement Initiative: Achievement Points Analysis for Academic Years 2007-2011”, CCRC-HELP Student Achievement Initiative Policy Study

Jenkins D., T. Ellwein and K. Boswell (2009), Formative Evaluation of the Student Achievement Initiative Learning Year, Report to the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges and College Spark Washington, CCRC.

Jenkins D., M. Zeidenberg and G. Kienzl (2010), “Educational outcomes of I-BEST, Washington State community and technical college system's integrated basic education and skills training program: Findings from a multivariate analysis”, Working Paper, No. 16, CCRC in Kuczera M. and S. Field (2013), Skills beyond School Review of the United States, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264202153-en.

Kuczera, M. and S. Field (2013), A Skills beyond School Review of the United States, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264202153-en.

Mitchell (2012), From Unease to Alarm: Escalating Concerns about the Model of ‘VET Reform’ and Cutbacks to TAFE, John Mitchell and Associates. www.jma.com.au/upload/pages/home/_jma_vet-reform-document.pdf.

OECD (2016), Investing in Youth: Australia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257498-en.

SBCTC (2012), Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training (I-BEST), www.sbctc.edu/colleges-staff/programs-services/i-best/, (accessed February 2013).

US Department of Education (2016), Fact Sheet: Obama Administration Increases Accountability for Low-Performing For-Profit Institutions, www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/fact-sheet-obama-administration-increases-accountability-low-performing-profit-institutions. (accessed 7 June 2017).

Wachen J., D. Jenkins and M. Van Noy (2010), How I-BEST Works: Findings from a Field Study of Washington State’s Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training Program, CCRC, New York.

← 1. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and are under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.