Chapter 2. Cultivating a culture of integrity in the Colombian public administration

This chapter reviews the Colombian policies and practices related to the promotion of a culture of integrity in the public service. In particular, it provides concrete recommendation on the normative framework, as well as the organisational underpinning to ensure its implementation. Furthermore, it provides guidance on how Colombia could strengthen its work towards a culture of integrity in the public sector by providing guidance, raising awareness and developing relevant capacities. Also, the chapter provides recommendations on how Colombia could mainstream integrity policies in human resource management, improve the financial and interest disclosure system, and ensure the enforcement of integrity standards. Finally, guidance on how to monitor and evaluate integrity policies is provided.

Embedding a culture of integrity in the public sector requires implementing complementary measures. Setting standards of conduct for public officials and the values for the public sector are amongst the first steps towards safeguarding integrity in the public sector. For instance, international conventions and instruments, such as the 2017 OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (OECD, 2017a) and the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), recognise the use of codes of conduct and ethics as tools for articulating the values of the public sector and the expected conduct of public employees in an easily understandable, flexible manner. Such instruments can support the creation of a common understanding within the public service and among citizens as to the behaviour public employees should observe in their daily work, especially when faced with ethical dilemmas or conflict-of-interest situations.

In addition, integrity measures are likely to be most effective when they are effectively integrated or mainstreamed into general public management policies and practices, especially human resource management and internal control (see Chapter 3), and when they are supported by sufficient organisational, financial and personal resources and capacities. In turn, high staff turnover, lack of guidance and a weak tone from the top are impediments to an open organisational culture where advice and counselling can be sought to resolve ethical problems such as conflict-of-interest situations.

Key elements to cultivating a culture of integrity comprise (OECD, 2017a), but are not restricted to:

-

Investing in integrity leadership to demonstrate a public sector organisation’s commitment to integrity.

-

Promoting a merit-based, professional, public sector dedicated to public-service values and good governance.

-

Providing sufficient information, training, guidance and timely advice for public officials to apply public integrity standards, including on conflict-of-interest situations and ethical dilemmas, in the workplace.

-

Supporting an open organisational culture within the public sector responsive to integrity concerns.

Overall, the set of measures defined by a coherent and comprehensive integrity policy framework should aim at creating cultures of organisational integrity in the public administration. Indeed, while laws and regulations define the basic standards of behaviour for public servants and make them enforceable through systems of investigation and prosecution, legal provisions remain strings of words on paper if they are not actually implemented and applied in all public entities. In order to effectively achieve such a cultural change, a balance is required between fostering extrinsic motivation of public officials through a rules-based approach, based on laws, controls and sanctions, and appealing to their intrinsic motivation through a values-based approach.

In Colombia, however, a recent survey on the working environment showed that 41.7% of public servants indicate that the absence of ethical values is the most influential factor on the occurrence of irregular practices (DANE, 2016). The following sections review the current normative and organisational framework, as well as existing policies and practices aimed at working towards a culture of integrity in the Colombian public administration. Concrete recommendations are derived to help Colombia in building a strong public integrity system where values-based and compliance-based approaches are balanced.

Building a normative and organisational integrity framework for the Colombian Administration

The Administrative Department of the Public Service (DAFP) should lead the promotion of a culture of integrity in the public administration, counting with the required organisational, financial and human resources and co-ordinating with other relevant actors through the National Moralisation Commission

A clear definition of mandates, objectives and functions is not only essential to designing sound integrity strategies and preventing overlaps between relevant actors, but also to creating an environment where awareness and understanding of values, principles and practices are uniform among public entities, and where clear and timely guidance is provided by responsible institutions. As analysed in Chapter 1, the Colombian public sector integrity system consists of several actors, some of them are members of the National Moralisation Commission (Comisión Nacional de Moralisación, or CNM), which is the mechanism to co-ordinate anti-corruption and integrity policies.

The mandate provided to the Administrative Department of Public Service (Departamento Administrativo de la Funcion publica, or DAFP) by Decree 2169 of 1992, clearly defines the DAFP as the lead entity for developing, promoting and implementing all regulations, policies and activities related to the promotion of ethics in the public administration and the management of conflict-of-interest situations. Also, the DAFP has to play a key role in strengthening the institutional capacities of the public administration in the context of the implementation of the Peace Agreement. As such, it was recommended in the previous chapter that the DAFP should become a full member of the National Moralisation Commission.

Indeed, for the executive branch, the DAFP is best positioned to provide: policy guidance and implementation support concerning integrity policies for the public administration; ensuring coherence between public ethics and conflict-of-interest management policies; and mainstreaming integrity measures into human resource management, internal control and risk management, regulatory simplification, and organisational development policies throughout the public administration at national and sub-national level. Furthermore, the DAFP can ensure consistency between policy and training needs by co-ordinating with the Higher School of Public Administration (Escuela Superior de Administración Pública, ESAP), responsible for formulating, updating and co-ordinating trainings and courses in matters of public management. A section below contains specific recommendations concerning the ESAP.

However, to be able to fulfil this key mandate of the public integrity system, Colombia should ensure that the DAFP has the organisational, financial and human resources required for providing implementation support to the policies it provides. Currently, it seems that the capacities of the DAFP are not sufficient to effectively fulfil its core functions and ensure an effective implementation and mainstreaming of its policies throughout the whole public administration. Beyond ensuring that the budget matches the tasks entrusted to the DAFP, efforts should also be made to focus on developing and delivering targeted services to its main clients, i.e. the ministries, and local and regional governments, while activities aimed at directly communicating to citizens could be reduced, leaving this to the respective public entities delivering the public services. Clearly identifying the addressees of the DAFP’s different regulations and policies, including public integrity policies, would enable to better target its efforts and resources on those areas where they are most expected and most needed, especially also related to the implementation of the Peace Agreement. While increasingly efforts are being made in this direction, the DAFP needs to carefully consider the different realities and levels of development in Colombia, such as those characterising rural and urban municipalities, and if necessary adapt its products and services accordingly. Ensuring realistic and thus effective policies becomes particularly relevant in the context of the implementation of the peace agreements in conflict-affected areas, where capacities are likely to be particularly low.

In addition, in the short term, Colombia should ensure, through the CNM, that existing programmes and related resources dedicated to cultivating a culture of integrity in the public administration are closely co-ordinated with the DAFP to ensure complementarity and avoid duplications and waste of resources. In the long term, it would be desirable if all programmes and resources aimed at promoting such a culture were unambiguously dedicated to the DAFP. Indeed, there are currently efforts by other entities aimed at promoting integrity in the public administration, for instance the “Culture of Legality” programme of the Inspector General (Procuraduría General de la Nación, or PGN) which aims at promoting integrity standards in the public administration, and activities undertaken by the Transparency Secretariat. However, beyond the potential duplication, such and similar programmes may create confusion amongst public servants about the relevant guidance concerning values and integrity standards. More specifically, the programme from the PGN may also blur the line between its disciplinary enforcement function, clearly a mandate of the PGN, and the prevention mandate of the DAFP related to developing and implementing public ethics policies for the public administration. In the future, other similar programmes therefore should either be leaded by the DAFP or at least be closely aligned with the policy guidance issued by the DAFP.

In turn, it is key to ensure a close co-ordination between enforcement and prevention functions as stressed below in the recommendation on ensuring effective responses to integrity violations. Indeed, a culture of integrity cannot be achieved by appealing to public values alone. Timely, appropriate and proportionate disciplinary and, if required, criminal sanctions need also to be in place when integrity breeches occur to ensure accountability and the credibility of the system. This co-ordination between the Inspector Office (PGN), the Prosecutor General (Fiscalía General de la Nación, FGN), the Comptroller General (CGR), the DAFP, the Transparency Secretariat and other relevant institutions can be ensured, again, through the co-ordination platform offered by the CNM, as recommended in Chapter 1.

To ensure an effective implementation of integrity policies throughout the public administration, the DAFP could consider establishing integrity contact points (units or persons) within each public entity

Even with a clearly defined mandate, the DAFP faces the serious challenge of ensuring that the integrity policies are actually implemented and mainstreamed throughout the public administration. The institutional arrangements that underpin legal and policy frameworks are a major contributing factor towards ensuring successful implementation. Although integrity is ultimately the responsibility of all organisational members, the OECD recognises that dedicated “integrity actors” are particularly important to complement the essential role of mangers in stimulating integrity and shaping ethical behaviour, namely “integrity actors” (OECD, 2009a). Indeed, international experience suggests the value of having a dedicated and specialised unit or individual that is responsible and in the end also accountable for the internal implementation and promotion of integrity policies in an organisation. Guidance on ethics and conflict of interest in case of doubts and dilemmas needs also to be provided on a more personalised and interactive level than just through written materials; especially to respond on an ad hoc basis when public officials are confronted with a specific problem or doubts.

Although some public entities in Colombia have ethics commissions/committees which could fulfil this task, there is currently no uniform implementation or normative guidance concerning the exact mandate, functions and organisational integration of these committees or similar units. Also, as these ethics commissions/committees are not obligatory, the DAFP does not have an overview of how many of them exist and how they are exactly implemented.

Therefore, the DAFP could develop a policy that clearly assigns integrity a place in the organisational structure of public entities and give the responsibility of promoting integrity policies to dedicated and specialised units or individuals within each entity; these could play the role of an Integrity Contact Point. In particular, such a policy could consider the fruitful experience of OECD countries such as Germany (Box 2.1) and Canada (Box 2.2). The DAFP should first pilot the implementation of such Integrity Contact Points in a specific sector, taking also into account successful experiences of existing ethics commissions/committees, in order to learn from the experience before scaling-up the requirement to the whole public administration.

Germany, at federal level, has institutionalised units for corruption prevention as well as a responsible person that is dedicated to promoting corruption prevention measures within a public entity. The contact person and a deputy have to be formally nominated. The “Federal Government Directive concerning the Prevention of Corruption in the Federal Administration” defines these contact persons and their tasks as follows:

-

A contact person for corruption prevention shall be appointed based on the tasks and size of the agency. One contact person may be responsible for more than one agency. Contact persons may be charged with the following tasks:

-

serving as a contact person for agency staff and management, if necessary without having to go through official channels, along with private persons;

-

advising agency management;

-

keeping staff members informed (e.g. by means of regularly scheduled seminars and presentations);

-

assisting with training;

-

monitoring and assessing any indications of corruption;

-

helping keep the public informed about penalties under public service law and criminal law (preventive effect) while respecting the privacy rights of those concerned.

-

-

If the contact person becomes aware of facts leading to reasonable suspicion that a corruption offence has been committed, he or she shall inform the agency management and make recommendations on conducting an internal investigation, on taking measures to prevent concealment and on informing the law enforcement authorities. The agency management shall take the necessary steps to deal with the matter.

-

Contact persons shall not be delegated any authority to carry out disciplinary measures; they shall not lead investigations in disciplinary proceedings for corruption cases.

-

Agencies shall provide contact persons promptly and comprehensively with the information needed to perform their duties, particularly with regard to incidents of suspected corruption.

-

In carrying out their duties of corruption prevention, contact persons shall be independent of instructions. They shall have the right to report directly to the head of the agency and may not be subject to discrimination as a result of performing their duties.

-

Even after completing their term of office, contact persons shall not disclose any information they have gained about staff members’ personal circumstances; they may however provide such information to agency management or personnel management if they have a reasonable suspicion that a corruption offence has been committed. Personal data shall be treated in accordance with the principles of personnel records management.

Source: German Federal Ministry of the Interior “Rules on Integrity”, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/Broschueren/2014/rules-on-integrity.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

Senior officials for public service values and ethics

-

The senior official for values and ethics supports the deputy head in ensuring that the organisation exemplifies public service values at all levels of their organizations. The senior official promotes awareness, understanding and the capacity to apply the code amongst employees, and ensures management practices are in place to support values-based leadership.

Departmental officers for conflict of interest and post-employment measures

-

Departmental officers for conflict of interest and post-employment are specialists within their respective organisations who have been identified to advise employees on the conflict of interest and post-employment measures (…) of the Values and Ethics Code.

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/ve/snrs1-eng.asp

The main responsibility of these Integrity Contact Points would be to implement DAFP’s integrity policies and encourage an open organisational culture where ethical dilemmas, public integrity concerns, and errors can be discussed freely, and where doubts can be raised concerning potential conflict-of-interest situations and how to deal with them. As such, they should be clearly separated from the enforcement function represented in Colombia by the internal disciplinary control function (control interno disciplinario). Indeed, ethical guidance needs to be provided in an environment where public officials can seek advice without fear of reprisal. The separation with the enforcement function would allow the Integrity Contact Points to acquire a separate identity and visibility, independent from the repressive paradigm which is common of legalistic systems like Colombia where the emphasis tends to be on enforcement of integrity and anti-corruption rules. Despite this separation, the individuals in the Integrity Contact Point should receive training on disciplinary issues and regularly co-ordinate with the internal disciplinary control staff to ensure that the guidance provided by them is not in conflict with existing regulations. The Integrity Contact Point would also play a crucial role facilitating the process of determining and defining integrity in the organisation, including the responsibility for developing, implementing and updating codes of integrity, as recommended below.

In addition, the Integrity Contact Point could be given a mediator role within the existing procedure to disclose an actual a conflict-of-interest situation established in Article 12 of the Administrative Procedure Code (Código de Procedimiento Administrativo y de lo Contencioso Administrativo). This states that the public official has to disclose his or her conflict of interest within three days of getting to know it to his supervisor or to the head of department or the Attorney General Office (or the Superior Mayor of Bogota or the Regional Attorney General Office at lower levels of government), according to public official seniority. The competent authority has then ten days to decide the case and, if required, designate an ad hoc substitute. To ensure that the conflict-of-interest situation is managed adequately, the DAFP therefore could improve the procedure by offering the public official the possibility to disclose the conflict-of-interest situation to any of the authorities listed above. This situation could also be managed by giving the Integrity Contact Points the role of mediator in case the public official has doubts as to whom he or she should disclose the situation to or in the event that he or she feels uncomfortable in disclosing his to his or her line manager. Furthermore, conflict-of-interest disclosures should be archived by the Human Resource Management units (HRM) together with the already existing personal file so that the HRM units have a have track record of situations which were raised by the public official (and information on how they were addressed).

From an organisational standpoint, the Integrity Contact Point, whether an individual or a unit, should be clearly integrated into the organisational framework and count with accountability mechanisms as well as have its own budget to implement the activities related to their mandate. The role of the Integrity Contact Point could be assigned to already existing staff member(s) or units (e.g. within the human resources units), and the number of staff could be defined according to the size of the respective public agency. Furthermore, the units or individuals should report directly to the head of the public entity, and receive targeted trainings and guidance to professionally fulfil their mandate. In addition, Colombia could consider whether the Integrity Contact Points should also report to the DAFP as a second line of accountability outside of their public entity to reduce the risk of collusion within entities, and to ensure the centralisation of information for statistical purposes.

In addition, Colombia could consider establishing a network between the Integrity Contact Points where they can exchange good practices, discuss problems and develop capacities (Box 2.3). Such a network should already be established during the pilot implementation to enable joint learning.

The Canadian Conflict of Interest Network (CCOIN) was established in 1992 to formalise and strengthen the contact across the different Canadian conflict of interest commissioners. The commissioners from each of the ten provinces, the three territories and two from the federal government representing the members of the Parliament and the Senate meet annually to disseminate policies and related materials, exchange best practices, discuss the viability of policies and ideas on ethics issues.

Source: New Brunswick Conflict of Interest Commissioner (2014), Annual Report Members’ Conflict of interest Act 2014, https://www.gnb.ca/legis/business/currentsession/58/58-1/LegDoc/Eng/July58-1/AnnualReportCOI-e.pdf.

The public integrity management framework currently developed by the DAFP should be based on risks, apply to all public employees independent of their contractual status, define public values, and provide guidance and procedures for conflict-of-interest situations and ethical dilemmas

Promoting public ethics and providing guidance for identifying and managing conflict-of-interest situations for resolving ethical dilemmas are at the core of developing a culture of integrity in the public sector. Such efforts should be integrated into public management and not perceived as an add-on, stand-alone exercise. Codes of conduct and ethics are generally the tools adopted to build and raise awareness of common values and standards of behaviour in the civil service. They can be understood as an entry point that can bring together different elements of integrity management within the public sector. Indeed, research has revealed that “codes influence ethical decision making and assist in raising the general level of awareness of ethical issues” (Loe et al., 2000). As such, codes should provide in particular relevant guidance to public officials when faced with conflict-of-interest situations and ethical dilemmas.

In Colombia, Decree 2539 of 2005 sets forth the general competencies required for public service at different levels in the entities ruled by Laws 770 and 785 of 2005. The Unique Disciplinary Code (Código Único Disciplinario) from 2002 establishes duties and behavioural guidelines for public servants, as well as the infringements and the sanctions that can be applied. The code is quite broad and vague, and is currently in the process of being reformed. Also the perspective of the Disciplinary Code is naturally one of enforcement, and not one of managing public ethics to promote a culture of integrity in the public sector. Furthermore, contrary to some OECD countries that have developed supplementary codes for specific at-risk positions, including for instance audit, tax and customs, financial authorities or public procurement, Colombia does not have yet such specific norms of conduct for sensitive areas and positions.

However, the current effort undertaken by the DAFP to develop an integrated integrity management framework and a General Integrity Code (Codigo General de Integridad) is commendable (Box 2.4). It sets out the premises to unify and strengthen the framework by clearly defining a set of public ethic values, the procedures for conflict-of-interest management, and guidance for resolving ethical dilemmas. Furthermore, additional codes will be elaborated to address high-risk areas such as contracting, procedures and services, human resources, internal control, finance, public managers.

In 2016, DAFP initiated the process to define a General Integrity Code which would form the basis for Colombia’s integrated integrity management framework. As showed in the figure below, the process leading to such Code started with the analysis of existing codes, was followed by the mapping of good practices (including OECD’s), and ended up in a participatory exercise involving public officials and leading to the selection of five values which would form the basis of the General Integrity Code.

Once the General Code of Integrity will be adopted, a number of additional steps are foreseen for the creation of an integrated management framework (so-called “phase-2”), namely:

-

The possibility to integrate the General Code with two additional values and principles to create codes in each entity;

-

The adoption of sector-specific codes in the following areas: contracting, procedures and services, human resources, internal control, financial areas, senior managers;

-

A nation-wide campaign to improve awareness, ownership and capacity building.

While the General Code of Integrity is expected to be adopted in the second semester of 2017, phase-2 of the creation of an integrated management framework is planned to be completed by 2018, at least for those aspects that do not require legislative changes.

Source: Based on a DAFP presentation at Peru’s Contraloria General de la Republica in Lima, 2 March 2017, and information provided by the DAFP.

Before the development of the General Integrity Code, most public entities had developed their own independent codes, setting internal guiding principles to promote, for example, openness, accountability, effective public management, public service vocation or citizen participation and the fight against corruption. This practice resulted in a highly fragmented landscape with more than 3 600 codes adopted by single public entities with limited impact on public officials’ conduct and awareness of ethical values. The main rationale for developing these codes has been the requirement by the standard internal control model (Modelo Estándar de Control Interno, or MECI), which stipulates that each entity has to develop a code of ethics to strengthen the control environment. According to the MECI, this code should be based on a previous survey, the ethics diagnostic (diagnóstico ético). Beyond this requirement, the codes that are currently still in force are not guided by any overarching framework that would ensure coherence by setting general principles, ethical duties and definitions. Consequently, the existing codes are very different in content, scope and quality. Although individual codes contribute to addressing organisational specificities and particular risks or sectors (see below), defining the overarching features of the integrity framework as it is currently being carried out through the development of the General Integrity Code will enable a uniform operating culture and the coherent implementation of integrity objectives. Furthermore, a fragmentation and lack of general principles and values, as has been the case in Colombia, has proved to make it difficult to ensure clarity and compliance amongst public officials.

Similarly, there is currently no single framework for the management of conflict-of-interest situations whose regulation is fragmented in various provisions and focuses on prohibitions and the punishment of conflict-of-interest situations (Table 2.1). There is currently a special conflict-of-interest regime for members of Congress (Article 182 of the Constitution and Law 5 of 1992), for city councillors (Law 136 of 1994), and for those responsible to evaluate the performance of public officials and members of the staff commission (Law-Decree 760 of 2005). Currently, the legal departments in the public entities – namely, the DAFP, the Ministry of the Interior, and the Office of the Inspector General of Colombia (PGN) – can provide a legal clarification to petitions (Derecho de petición) and consultations of civil servants and individuals related to specific situations that may generate incapacity, incompatibility or conflict-of-interest. The DAFP also produces briefs that explain to public officials and citizens in a didactic way the behaviour that can produce legal inabilities (inhabilidades), incompatibilities (incompatibilidades) or conflict of interest. However, there are no standardised administrative guidelines to guide public officials of different levels of government in the process of reporting and managing conflict of interest (Transparencia por Colombia, 2014a), and such guidance is until now not included in the General Integrity Code.

Therefore, in order to ensure consistency and coherence, the DAFP could take the opportunity related to the current development of a General Integrity Code to ensure that its integrated integrity management framework includes the following:

-

A number of common values and principles, as provided by the General Integrity Code;

-

A unique definition of a conflict-of-interest and guidance on how to identify and resolve them;

-

Guidance on ethical reasoning when faced with ethical dilemmas.

First of all, the commendable participative process of developing the General Integrity Code has led to the definition of a set of five values (honesty, respect, service attitude, commitment, justice) that are in line with those chosen as pillars of integrity systems in OECD countries. These are: rule of law, impartiality, transparency, faithfulness, honesty, service in the public interest, and efficiency (OECD, 2009b). In further pursuing the process of instilling a values-based culture of integrity, the DAFP could consider the work of the Council on Basic Values in Sweden, whose mission is to strengthen and improve the central government employees’ knowledge and respect for the six common basic values applying to all state entities (Box 2.5). In addition, it could take into account the OECD experience which suggests that the framework should be clear, concise, and simple in order to support public employees in understanding the key principles and values by which they should abide (OECD, 2009a).

The regulation of public agencies’ activities in Sweden is based on the legal foundations that apply to all central government agencies. These are summarised in six principles, which together make up the common basic values of central government activities:

-

Democracy – all public power proceeds from the people.

-

Legality – public power is exercised in accordance with the law.

-

Objectivity – everyone is equal before the law; objectivity and impartiality must be observed.

-

Free formation of opinion – Swedish democracy is founded on the free formation of opinion.

-

Respect for all people’s equal value, freedom and dignity – public power is to be exercised with respect for the equal worth of all and for the freedom and dignity of the individual.

-

Efficiency and service – efficiency and resource management must be combined with service and accessibility.

These principles, which are set out in the Swedish Constitution and acts of law, form a professional platform for central government employees. They are to guide employees in the performance of all your duties. A guide is also made available for those who are in charge of work with issues relating to basic values and the common basic values for central government employees in order to support the use of methods and to facilitate development processes and operational-level discussions in each authority.

Source: http://www.government.se/49b756/contentassets/7800b1f18910475d9d58dba870294a63/common-basic-values-for-central-government-employees--a-summary-s2014.021; http://www.vardegrundsdelegationen.se/media/A-guide-to-working-with-the-central-government%E2%80%99s-basic-values.pdf.

Second, the General Integrity Code, or a complementary guide, should also provide unambiguous guidance with respect to identifying and managing conflict-of-interest situations, which are perhaps the single most important integrity risk situation. In particular, it should be communicated clearly that conflict-of-interest situations can arise at any point and that they are not equivalent to corruption per se. It needs to be highlighted that having a conflict-of-interest cannot always be avoided, but that the critical issue is what actions the public official takes to resolve the conflict. Interviews revealed that public servants in Colombia tend to have a quite narrow and legalistic understanding of conflict of interest and to confound a conflict of interest with the figure of trading in influence or, more generally, with corruption.

Therefore, Colombia could consider unifying the different laws, regulations, decrees and resolutions touching upon conflict of interest into one single coherent regulation or policy document which should include a brief and clear definition of conflict of interest (Box 2.6), and provide the bedrock to identify disclose, manage, and promote the appropriate resolution of conflict-of-interest situations. The legal foundation should be reflected in the General Integrity Code in simple non-legalistic language.

In its 2003 Guidelines for Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service, the OECD proposes the following definition: A ‘conflict of interest’ involves a conflict between the public duty and private interests of a public official, in which the public official has private-capacity interests which could improperly influence the performance of their official duties and responsibilities.

Portugal has established a brief and explanatory definition of conflict of interest in the law: conflict of interest is an opposition stemming from the discharge of duties where public and personal interests converge, involving financial or patrimonial interests of a direct or indirect nature.

Similarly, central European countries in transition have put an emphasis on providing public officials with a general legal definition applicable across the whole public service that addresses actual and perceived conflict of interest. For instance, the Code of Administration Procedure in Poland covers both forms of conflicts: a situation of actual conflict of interest arises when an administrative employee has a family or personal relationship with an applicant. A perceived conflict exists where doubts concerning the objectivity of the employee exist.

Source: OECD (2004), Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Service: OECD Guidelines and Country Experiences, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264104938-en.

A useful starting point is Transparency International Colombia’s Guide on conflict of interest (Guía práctica para el trámite de conflictos de intereses en la gestión administrativa) which contains explanations, questions and examples which could be taken in consideration (Transparencia por Colombia, 2014b). Similarly, the DAFP could take into account the exercise carried out by Mexico’s Specialized Unit for Ethics and Prevention of Conflicts of Interest (UEEPCI), of the Ministry of Public Administration (SFP), which in March 2016 issued a document to guide public officials in identifying and preventing conducts that could constitute a conflict of interest for public officials (UEEPCI, 2016). The latter guide is based on international standards and good practices, is written in plain language and provides a list of high-risk processes.

Third, the General Integrity Code, or a complementary guide, should also address the problem of ethical dilemmas in a generic way. Indeed, public officials may face ethical dilemmas due to the application of competing values and standards when carrying out their duties. While the ethical reasoning skills to solve such dilemmas cannot be provided by a code alone and requires the development of ethical capacities through training and practice, the acknowledgment that such ethical dilemma situations exist and some guidance on how to resolve them, as for example the REFLECT model used in Australia (Box 2.7), would be desirable.

The Australian Government developed and implemented strategies to enhance ethics and accountability in the Australian Public Service (APS). To support the implementation of ethics and integrity regime, the Australian Public Service Commission has enhanced its guidance on APS Values and Code of Conduct issues. This includes integrating ethics training into learning and development activities at all levels.

To help public servants in their decision-making process when facing ethical dilemmas, the Australian Public Service Commission developed a decision-making model. The model follows the acronym REFLECT:

-

Recognise a potential issue or problem

-

Public officials should ask themselves:

-

Do I have a gut feeling that something is not right or that this is a risky situation?

-

Is this a right vs right or a right vs wrong issue?

-

Recognise the situation as one that involves tensions between APS Values or the APS and their personal values.

-

-

-

Find relevant information

-

What was the trigger and circumstances?

-

Identify the relevant legislation, guidance, policies (APS-wide and agency-specific).

-

Identify the rights and responsibilities of relevant stakeholders.

-

Identify any precedent decisions.

-

-

Linger at the ‘fork in the road’

-

Talk it through, use intuition (emotional intelligence and rational processes), analysis, listen and reflect.

-

-

Evaluate the options

-

Discard unrealistic options.

-

Apply the accountability test – public scrutiny, independent review.

-

Be able to explain your reasons/decision.

-

-

Come to a decision

-

Come to a decision, act on it and make a record if necessary

-

-

Take time to reflect

-

How did it turn out for all concerned?

-

Learn from your decision.

-

If you had to do it all over again, would you do it differently?

Source: Office of the Merit Protection Commissioner (2009), “Ethical Decision Making”, http://www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/ethical-decision-making

In addition, ensuring clear guidance may also encompass taking into consideration the specific risks associated with the administrative functions and sectors that are most exposed to integrity violations. Most OECD countries have defined those areas that are most at risk and provide specific guidance to prevent and resolve conflict-of-interest situations. Indeed, some public officials operate in sensitive areas with a higher potential risk of conflict of interest, such as justice, tax and customs administrations and officials working at the political/administrative interface (Figure 2.1). In addition, there are further areas identified as being at risk of conflict of interest that could be considered: additional employment or contracts; “inside” information; gifts and other forms of benefits; family and community expectations; “outside” appointments; and activities after leaving public the organisation (OECD 2004). Also, bearing in mind the implementation of the Peace Agreement and the need to strengthen legitimacy of the State in Colombia (see Chapter 1), the new integrity framework could define specific rules for public officials working in institutions at all levels which will be most involved during the process. For these at-risk positions and areas to be defined by Colombia, specific regulations and guidance could be helpful to prevent and resolve conflict-of-interest situations that complement the General Integrity Code.

Source: OECD Survey on Management of Conflict of Interest (2014).

Finally, it is important that the integrity rules in Colombia apply to all public officials and employees, independent of their contractual status or whether national or sub-national level. All should receive the same level of basic guidance and training, while senior management and at-risk position may receive additional, tailored guidance (see sections below). Indeed, due to capacity issues at the National Civil Service Commission (Comisión Nacional del Servicio Civil, or CNSC) and the high costs for running a meritocratic competition for civil service position, there is currently in effect a two-tier employment system in Colombia’s civil service, with significant numbers of casual staff. They can be hired on a discretionary basis by managers outside of CNSC merit-based process, work alongside career civil servants, often carrying out the same public functions as civil servants and are often employed for considerable periods, but without the terms and conditions of employment of civil servants.

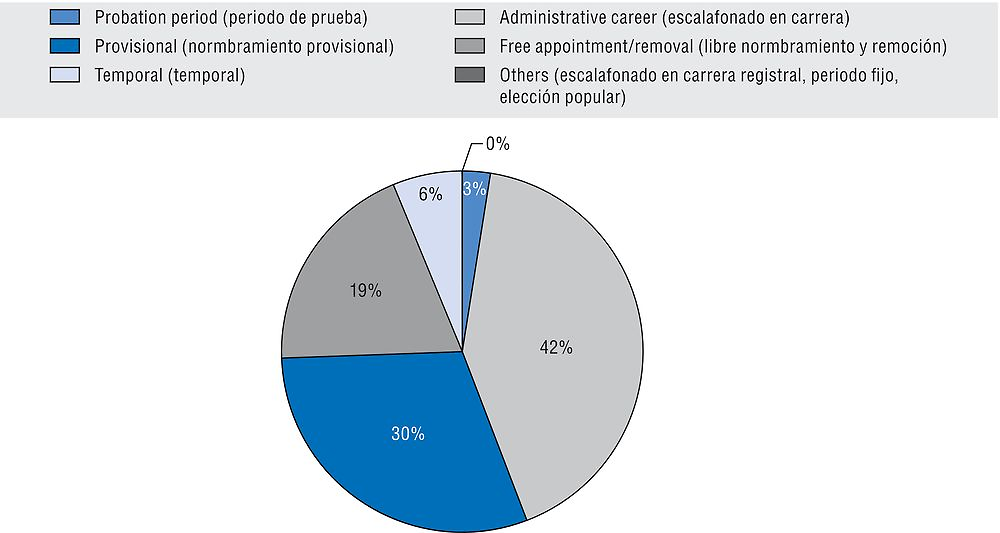

At present, the total number of staff not part of the administrative career is estimated to be around 60% of the total staff. Such category includes provisional staff (nombramiento provisional), free appointment/removal staff (libre nombramiento y remoción), temporal staff (temporal), and staff in probation period (periodo de prueba) (Figure 2.2). Currently, these provisional employees are not eligible for training since they are meant to be hired for specific roles for which they already hold expertise. Given their insights and knowledge they are exposed to conflict-of-interest situations that could either arise during their contract with the ministry or after taking a post in the private sector (OECD, 2013a).

Source: System of Information and Management of Public Employment (Sistema de Información y Gestión del Empleo Público, or SIGEP) as of 31 December 2016.

Colombia should therefore ensure that staff on temporary contract is made aware of the public ethics and conflict-of-interest regulations. They should receive the same public ethics and conflict-of-interest induction training, be obliged to declare any conflict-of-interest situation. In addition, it could be considered to make it obligatory to inform HR of future employment plans in the view to avoid conflict of interest.

The current development of an integrity management framework has opened the opportunity to revise existing codes at organisational level in a participative way, and to ensure a more effective implementation of these Organisational Integrity Codes aimed at changing behaviours

The ongoing elaboration of an overarching integrated public integrity management framework, and the implementation of the Integrity Contact Points recommended above, open the opportunity for revising the already existing organisational codes. This will not only ensure their alignment with the guiding principles set by the future General Integrity Code and complementary codes for at risk-areas, but also apply a sound methodology for reviewing them with a view to trigger a cultural change in the public entities. The process envisaged for the revision of the existing entities’ codes, which includes the integration of the General Integrity Code with specific values and principles, would allow strengthening codes that are currently not up to the standards or that have been elaborated in the past more to comply with the internal control provisions than with the view to promote a culture of integrity. At the same time, codes that are already considered as good practices in the Colombian administration can be used as examples and can see the review process as an opportunity for further improvement and effective implementation.

As a result, the Colombian Integrity code infrastructure could be structured around three levels of codes which should be coherent with each other (Figure 2.3): The General Integrity Code complemented by codes or guides for at-risk positions that apply to all entities of the public administration on the one hand; and on the other hand, Organisational Codes of Integrity that should be based on the General Integrity Code, while allowing to tailor them to the specific needs and challenges of the organisation. This tailoring should go beyond the additional two values that are currently planned, and allow for more flexibility in building on the five basic values provided in the General Integrity Code.

Indeed, just as different organisations are facing different contexts and nature of work, they may also be faced with distinctive ethical dilemmas and specific conflict-of-interest situations. For instance, the challenges might differ significantly between the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Defence, and the different supervisory and regulatory bodies. In particular, the OECD experience on conflict-of-interest management shows that public officials should be provided with real-world examples and discussions on how specific conflict situations have been handled. Organisational Integrity Codes provide an excellent opportunity to include relevant and concrete examples from the organisation’s day-to-day business, to which the employees can easily relate.

Beyond the content of the Organisational Integrity Codes, the process matters as well. Similar to the participatory process followed to define the shared values at the basis of the General Integrity Code, the review of the organisational codes should build consensus and ownership, and provide relevant and clear guidance to all public servants. Indeed, stimulating a participative, bottom-up process of elaborating organisational codes according to clear methodological guidance can mitigate the risk of codes becoming a “check-the-box” exercise aimed at complying with the task, as has been observed in many public entities in the past, and not only in Colombia. Rather, a consultative approach complemented by a prior analysis of organisations’ particular integrity risks and potential ethical dilemmas aims at promoting discussions amongst the employees and building consensus about the shared values and principles of behaviour. Involving staff members from all levels in the process of developing the code, e.g. through focus group discussions, surveys or interviews, would not only ensure its relevance and effectiveness, but it would also increase staff-members’ feelings of ownership and increase the probability of compliance with the code.

In addition, the experience of OECD countries demonstrates that consulting or actively involving external stakeholders, such as providers or users of the public services delivered by the entity, in drafting a code helps build a common understanding of public service values and expected standards of public employee conduct. External stakeholder involvement could thereby improve the quality of the code so that it meets both public employees’ and citizens’ expectations, and communicate the values of the public organisation to its stakeholders. By including the clients, the public entity would also be able to demonstrate its commitment to greater transparency and accountability, thereby contributing to building public trust.

Therefore, the DAFP could consider updating the requirements linked to the development of codes of ethics in the internal control framework, MECI, and stipulate in its integrity management framework that organisations have to develop their own Organisational Integrity Codes based on the General Integrity Code and complementary at-risk codes, and that these should be developed according to a specific methodology. DAFP should also provide clear methodological guidance to assist the Integrity Contact Points in steering the participative development of their codes while ensuring that they align with the overarching principles. Such methodological guidance should reduce as much as possible the scope for developing the code as a “check-the-box” exercise, and include details on how to manage the construction, communication, implementation, and periodic revision of the codes in a participative way. Ideally, a written guide on the process should be complemented with trainings and ad hoc advice to public entities provided by staff from the DAFP during the process. Colombia needs to ensure that the DAFP counts with the required resources to fulfil this task.

Again, in the short term, the revision of the organisational codes should be piloted in a given sector first, ideally in the same sector where the dedicated Integrity Contact Points recommended above are piloted, so that these units can lead the process, supported by the DAFP.

In this context, Colombia can benefit from the experience of countries which have already elaborated codes in a similar way. In Brazil, for instance, the consultation process undertaken for the Comptroller General of the Union’s code of conduct raised interesting issues that also served as input for the government-wide integrity framework (Box 2.8).

The Professional Code of Conduct for Public Servants of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union was developed with input from public officials from Office of the Comptroller General of the Union during a consultation period of one calendar month, between 1st and 30 June 2009. Following inclusion of the recommendations, the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union Ethics Committee issued the code.

In developing the code, a number of recurring comments were submitted. They included:

-

the need to clarify the concepts of moral and ethical values, as it was felt that the related concepts were too broad in definition and required greater clarification;

-

the need for a sample list of conflict-of-interest situations to support public officials in their work; and

-

the need to clarify provisions barring officials from administering seminars, courses, and other activities, whether remunerated or not, without the authorisation of the competent official.

A number of concerns were also raised concerning procedures for reporting suspected misconduct and the involvement of officials from Office of the Comptroller General of the Union in external activities. Some Office officials inquired whether reports of misconduct could be filed without identifying other officials and whether the reporting official’s identity would be protected. Concern was also raised over the provision requiring all officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union to be accompanied by another Office of the Comptroller General of the Union official when attending professional gatherings, meetings or events held by individuals, organisations or associations with an interest in the progress and results of the work of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union. This concern derived from the difficulty in complying with the requirement, given the time constraints on officials from the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union and the significant demands of their jobs.

Source: OECD (2012), Integrity Review of Brazil: Managing Risks for a Cleaner Public Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119321-en.

The revision of existing codes could be also complemented by additional measures to implement them in a more effective way based on insights from research in behavioural sciences. For this purpose, “moral reminders” could be built into key decision-making processes, ideally identified during risk assessments (see Chapter 3). Research shows that such small reminders concerning the correct behaviour do have a measurable impact on the probability to cheat (Ariely, 2012, Box 2.9 and 2.10). A concrete policy measure that could be derived from this experimental evidence could be to include, for example, a line to be signed by a procurement official or human resource manager just before taking a crucial decision with managing a procurement contract or a hiring process. The line could read “I will take the following decision according to the highest professional and ethical standards”. By signing, the official implicitly links his name to an ethical conduct.

Behavioural research shows that more ethical choices can be triggered by reminding people of moral norms. This can be an inconspicuous message, such as “thank you for your honesty”. Contextual clues in the immediate situation function as reference to an underlying norm (cf. Mazar & Ariely, 2006). Such moral appeal has in some cases shown to be even more effective than a reminder of the threat imposed by a punishment. In field experiments subjects paid a higher price for a newspaper (Pruckner & Sausgruber, 20213) and were more likely to pay back a debt (Bursztyn et al., 2016) when exposed to a moral reminder.

These findings are in line with the understanding, that most people view themselves as moral individuals (Aquino & Reed, 2002). When reminded of moral standards, actions are adjusted accordingly to reduce the dissonance between self-concept and behaviour. Many small acts of cheating are in fact also acts of self-cheating. The cost of this can be increased not through an increase in external punishment, but by increasing the salience of intrinsic morality.

Source: Aquino and Reed (2002); Bursztyn et al (2016); Mazar, Amir, and Ariely (2008); Pruckner and Sausgruber (2013).

There are possibilities to measure cheating through experimental designs (e.g. Ariely, 2012, or Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi, 2012). Before implementing or reforming innovative integrity policies aimed at reducing dishonest behaviour, a country could apply such experimental designs to measure the “cheating baseline” in an organisation or group.

On the one hand, the experiments could inform the country if there are areas where cheating is more common than in others, and consequently focus policies on these areas. On the other hand, the baseline would allow the country to have a concrete indicator to measure whether the piloted policies had the desired impact before considering an up-scaling.

Source: Ariely (2012); Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi (2012).

Developing capacities and raising awareness for integrity

To enhance the academic independence of the National School of the Public Administration (ESAP), the appointment procedure of its Director could be reviewed and associated with a system of checks and balances

The Higher School of Public Administration (Escuela Superior de Administración Pública, or ESAP) is an academic institution attached to the DAFP in charge of fulfilling the education and training requirements of public servants as well as advising the administration on public affairs and management issues. Pursuant to Decree 2083 of 1994, it is given judicial, administrative, and financial independence in line with the State’s regulation on higher education. As for its administration, the ESAP is managed by the National Directive Council (Consejo Directivo Nacional), the National Academic Council (Consejo Académico Nacional), and the National Director (Director Nacional), who is in charge of the most strategic issues such as the presentation and implementation of the ESAP’s Development Plan, presenting the school budget as well as nominating staff and chairing the National Academic Council.

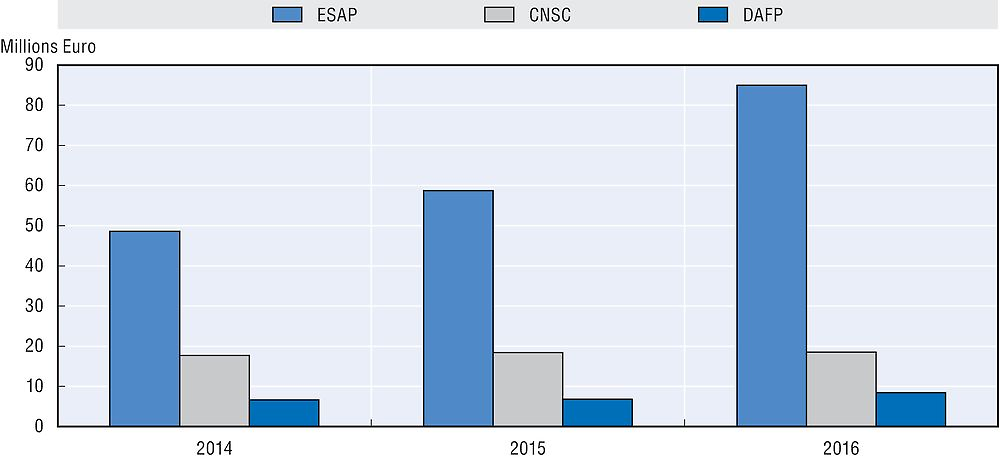

Although the composition of the National Directive Council reflects a certain degree of diversity, including representatives from regions, municipalities, teachers and students, the law does not establish any specific qualification for the National Director, who is discretionally appointed (and can be equally removed) by the President of the Republic. Even though there should be some degree of responsive to governmental priorities (OECD, 2017b) as well as alignment between the development of policies from the executive and the work of ESAP on ethics and integrity (see recommendation below), the mission of the National Director should be primarily to ensure that the considerable amount of resources managed (Figure 2.4) is used to reach the highest academic standard of the ESAP’s research and training activities beyond political contingencies.

Source: OECD elaboration with data provided by DAFP.

In order to mitigate the risks involved in such a dependency from political power, the rules of the ESAP’s governance could be reviewed to ensure appropriate checks and balances as well as the independence and professional qualification of its director. For this purpose, Colombia could consider the arrangements of the French National School for Public Administration (École National d’Administration, or ENA), and the Italian National School of Public Administration (Scuola Nazionale dell’Amministrazione, or SNA), whose heads have to fulfil certain professional criteria and who are also subject to oversight mechanisms by other independent organs (Box 2.11). This way, Colombia would also align closer to OECD practice in this context. An OECD Survey suggests that a governance model based on institutional autonomy may be ideal for schools of government modelled on higher education institutions, as it is the case for the ESAP (OECD, 2017b).

The National School for Public Administration (Ecole National d’Administration, or ENA) is an administrative body attached to the Department of the Prime Minister through the General Directorate of the Public Service. Its governance includes a governing body (Conseil d’ Administration) which is chaired by the Vice President of the Council of State and is supported by an orientation committee (Conseil d’orientation) for curricular affairs. The director of ENA is nominated with a Decree for a 5-year period renewable for one time and can be removed under the conditions established by Law 84-16 of 1984. As for his or her functions, the director is in charge of executing the decisions taken by the governing body, is assisted by an administrative staff and supervised by a secretary general.

The Italian National School of Public Administration (Scuola Nazionale dell’Amministrazione, or SNA) is a high-level training and research institution belonging and under the oversight of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, which has the main objective of carrying out post-graduate training for public officials supported by analysis and research activities. SNA’s President is appointed with decree by the President of the Council of Ministers upon proposal of the Ministry of Public Function among judges, professors and senior managers with proved experience and qualification. He/she is supported by a consultative scientific committee (Comitato scientifico consultivo) and reports to a management committee (Comitato di gestione), which is composed by representatives from various ministries and approves the School’s programme and budget.

Source: George Vernardakis (2013), “The National School of Administration in France and Its Impact on Public Policy Making”, Croatian & Comparative Public Administration 13(1); Decree 49 of 2002 (France) (https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/decret/2002/1/10/2002-49/jo/texte); Legislative Decree 178 of 2009 (Italy).

In order to reach national and international standards of academic excellence, the ESAP should introduce mechanisms to establish a transparent and competitive hiring process for its staff

The excellence of an academic institution does not only depend on its governance, but also on the capacity to attract the most talented teachers and researchers through open competitions and a meritocratic hiring and professional development process. Within the ESAP there seems to be room for improvement in this context. Journalistic investigations report that an audit from the Comptroller General (Contraloría General de la República, or CGR) found “lack of controls in contracted teaching hours, unexplained links among teachers and excessive payments” (http://www.lanacion.com.co/index.php/noticias-regional/neiva/item/220918-la-esap-desorganizacion-y-derroche-de-dinero). Also, publicly-available data on the hiring process of ESAP’s professors seems not be fully up-to date and does not allow to clearly identify on-going competitions for positions (http://www.esap.edu.co/portal/index.php/convocatorias/).

The opacity of the hiring mechanisms does not benefit from the centralisation of the hiring decision within the director of ESAP, who is highly dependent of politics and therefore could be subject to contingent clientelistic dynamics. The latter challenge seems to be reflected in the high rate of contractors (Table 2.2), which also represents an obstacle to build continuity in the work of the institution and eventually may affect the quality of its research and activities.

To reach the highest standards of academic excellence and minimise the aforementioned risks, the ESAP should therefore introduce mechanisms to promote a merit-based, transparent professional hiring process in line with the principles of the 2017 OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity. This recommendation stresses the importance of supporting “the professionalism of the public service, prevents favouritism and nepotism, protects against undue political interference and mitigates risks for abuse of position and misconduct” (OECD, 2017a).

DAFP and ESAP need to improve co-ordination to ensure consistency between policy and training and to develop general induction trainings on integrity for all public officials, as well as specialised modules for senior managers and public officials working in specific at-risk positions

A code cannot alone guarantee ethical behaviour. Designing a code in a participative way, as recommended above, is only one part of the overall organisational strategy for determining the behaviour expected of public officials and employees in the workplace. To be effectively implemented, the code must be part of a wider organisational strategy, and, since the staff may change over time, the institution in question must be committed to continuously train and educate employees on applying public ethics and identifying and reacting to conflict-of-interest situations. Training, raising awareness, and disseminating the core values and standards are key elements of sound integrity management.

In Colombia, according to Decree Law 1567 of 1998, Law 909 of 2004 and Decree 1083 of 2015, the DAFP is responsible for formulating, updating and co-ordinating the National Training Plan, and the ESAP is responsible for implementing the policy and developing tools and courses. However, training activities and objectives currently seem to be almost exclusively related to the development of skills needed for the job (desarrollo de competencias) without any reference to principles and integrity standards. For instance, one can consider the 2016 Institutional Training Plan, whose objective is to contribute to the institutional improvement by strengthening the labour competencies, knowledge, and training abilities and by promoting the comprehensive development of officials.

Therefore, the DAFP, in close co-ordination with the ESAP, should develop a specific capacity-building strategy for public officials aimed at building capacities on integrity. This should include a general introduction within the induction training followed up by regular update-training as well as more specific trainings tailored to staff of the Integrity Contact Points recommended above, and to needs and risk-areas.

First, all new employees, independent of their contractual status, should receive an induction training which represents a perfect opportunity to set the tone with respect to integrity from the beginning of the working relationship, explaining the principles and values, and the rules related to public ethics and conflicts of interest. The most basic and generic parts of such a training could be implemented through e-learning modules, but it could be considered to prepare organisation-specific induction courses, for instance in relationship with the organisational codes that have to be developed based on the common framework as recommended above (Box 2.12). Regular update training should also be provided to increase the effectiveness of integrity training and present the new elements of the normative framework. Integrity discussions could also be institutionalised in daily communication, e.g. by regularly discussing an ethical dilemma in staff meetings while using the techniques learned in previous trainings. Considering that, according to Article 8 of Decree 1567 of 1998, the basic curriculum for induction training is designed by the ESAP, in line with the policy elaborated by the DAFP; close co-ordination should be ensured between the policy elaboration by the latter and the training functions of the former.

In the Government of Canada, integrity training for public sector employees is conducted at the Canada School of Public Service. The Treasury Board Secretariat works closely with the School to develop training for employees on the subject of values and ethics. The School recently updated the orientation course for public servants on values and ethics, which is part of a mandatory curriculum for new employees. In addition, federal departments use the course as a refresher for existing employees to ensure they understand their responsibilities under the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector. In order to ensure accessibility for all public servants, the course is available online.

The course focuses on familiarising public servants with the relevant acts and policies, such as the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector, the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act and the Policy on Conflict of Interest and Post-Employment. Additionally, modules on ethical dilemmas, workplace wellbeing and harassment prevention are included in the training. Through the five different modules, public servants not only increase their awareness of the relevant policy and legislative frameworks, but also develop the skills to apply this knowledge as a foundation to their everyday duties and activities.

The training course includes a dedicated module on the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector. The module highlights the importance of understanding the core values of the federal public sector as a framework for effective decision making, legitimate governance as well as for preserving public confidence in the integrity of the public sector. The module contains a section on duties and obligations, where the responsibilities for employees, managers/supervisors, and deputy heads/chief executives are provided in detail. This section also discusses the Duty of Loyalty to the Government of Canada, stating that there should be a balance between freedom of expression and objectiveness in fulfilling responsibilities, illustrated with an example from social media. At the end of the module there are two questions posed to ensure participants have understood the purpose of the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector and the foundation for fulfilling one’s responsibilities in the public sector.

An innovative component of the integrity-training course is the module on ethical dilemmas. The purpose of the module is to ensure familiarity with the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector, and it includes a range of tools to cultivate ethical decision making amongst public servants. The module also informs public servants of the five core values for the Canadian public service––respect for democracy, respect for people, integrity, stewardship and excellence––prompting them to think about how to apply these values in their everyday role. Key risk areas for unethical conduct, such as bribery, improper use of government property, conflict of interest and mismanagement of public funds are identified, with descriptions that put the risks into practical, easy to understand language. By posing three different scenario questions and asking participants to select competing public sector values, the module also encourages public servants to think about how conflicts between these values may be resolved.

Source: Treasury Board Secretariat, Canada

Second, Colombia could consider developing specialised training modules on integrity for the staff of the Integrity Contact Points and for senior managers. Both can be considered as internal vectors in the organisations that should lead by example and develop in-depth capacities on how to provide guidance on integrity issues. The High Government School (Escuela de Alto Gobierno), which is part of ESAP and organises training for senior officials (alta gerencia), including elected mayors and governors, pursuant to Article 30 of Law 489 of 1998, does not currently offer any training on integrity or ethical topics, and could therefore develop such a module or course. This in-depth capacity building should be mandatory for the Integrity Contact Points, and voluntary for senior managers, although Colombia could think of linking the participation to positive incentives in line with relevant regulation.

At the same time, efforts could be taken to organise ad hoc training to public officials working in at-risk positions, such as public procurement officials, auditors, customs officials, as well as specific modules aimed at recognising and managing conflict of interest and resolving ethical dilemma (see Box 2.13). Lastly, Colombia could organise context-specific training by introducing examples and cases related to the sector and the specific challenges and risk faced by the entity.

In the Dilemma training, offered by the Agency for Government Employees, public officials are given practical situations in which they face an ethical choice and it is not clear how to best resolve the situation with integrity. The facilitator encourages discussion between the participants about how the situation could be resolved to explore the different choices. As such, it is the debate and not the solution which is most important, as this will help the participants to identify different values might oppose each other.

In the majority of trainings, the facilitator uses a card system. He explains the rules and participants receive four ‘option cards’ with the number 1, 2, 3 or 4. The ‘dilemma cards’ are placed on the table The ‘dilemma cards’ describe the situation and give four options on how to resolve the dilemma, are placed on the table. In each round, one of the participants reads out the dilemma and options. Each participant indicates their choices with the ‘option cards’ and explains their motivation behind the choice. Following this, participants discuss the different choices. The facilitator remains neutral, encourages the debate and suggests alternative options how to look at the dilemma (e.g. sequence of events, boundaries for unacceptable behaviour).

One example of a dilemma situation that could arise would be: I am a policy officer. The minister needs a briefing within the next hour. I have been working on this matter for the last two weeks and should have already been finished. However, the information is not complete. I am still waiting for a contribution from another department to verify the data. My boss asks me to submit the briefing urgently as the chief of cabinet has already called. What am I doing?

-

I send the briefing and do not mention the missing information.

-

I send the briefing, but mention that no decisions should be made based on it.

-

I do not send the briefing. If anyone asks about it, I will blame the other department.

-

I do not send the information and come up with a pretext and the promise that I will send the briefing tomorrow.

Other dilemma situations could cover the themes of conflicts of interest, ethics, loyalty, leadership etc. The trainings and situations used can be targeted to specific groups or entities. For example: You are working in Internal Control and are asked to be a guest lecturer in a training programme organised by the employers of a sector that is within your realm of responsibility. You will be well paid, make some meaningful contacts and learn from the experience.

Source: https://overheid.vlaanderen.be/omgaan-met-integriteitsdilemmas (in Dutch)

Regular awareness raising activities should be organised to communicate ethical duties and values internally within the organisation as well as externally to the whole of society

Although Integrity Codes are themselves tools adopted to raise awareness of common values and standards of behaviour in the civil service, the vast majority of OECD member countries employ additional measures to communicate core values for public servants. Especially with respect to awareness-raising measures for conflict-of-interest management, OECD countries generally use complementary awareness-raising measures in order to ensure a comprehensive effort in this regard (Table 2.3).

However, there is little evidence that Colombia currently conducts regular communication activities to promote a culture of integrity and raise awareness for the importance of abiding by public service values and ethics, and managing conflict-of-interest situations. For instance, according to the 2013–2014 Transparency Index of Transparency International’s Colombian Chapter (Transparencia por Colombia), only 50% of departmental entities publicise their code of conduct or ethics on their website.

As a consequence, Colombia should take initiatives to promote ethical duties and values internally within the organisation as well as externally to society, e.g. the private sector, civil society and citizens as users of public services. This would not only allow communicating these actors the benefits of public integrity, but it would also contribute to reduce tolerance of violations of public integrity standards and to improve the effective delivery of public services through the territory.

The Transparency Secretary has taken important initiatives to create awareness within society, including the Transparency Pacts with private sector organisations, the project Firms Active in Anti-corruption Compliance (Empresas Activas en Cumplimiento Anticorrupción), and the Methodological Paths of a Culture of Transparency, Integrity, and the Public Good (Rutas Metodológicas de Cultura de la Transparencia, Integridad y Sentido de lo Público). However, these efforts could be organised in a consistent and coherent manner. Furthermore, they may target specific categories of external stakeholders, especially in the field of public procurement.

Although institutional competences are not clear cut in this context, the Transparency Secretary could take the lead and co-ordinate actions considering its experience and mandate which is, pursuant to Decrees no. 4637 of 2011 no. 1649 of 2014, to define and promote strategic actions between the public and private sector to fight corruption, as well as to elaborate strategies to promote the culture of legality.

At the same time, communication and awareness raising to public servants should be led by the Integrity Contact Points, and the DAFP. For instance, the DAFP could explore whether a section dedicated to integrity could be opened in the Virtual Advice Space (Espacio Virtual de Asesoría, or EVA), which is a good practice of the DAFP to facilitate on-line guidance to public servants (Box 2.14). Also, the DAFP should ensure that the Organisational Integrity Codes are included in the minimum information which each entity has to publish pursuant to Article 9 of Law 1712 of 2014.

EVA (Virtual Advice Space, Espacio Virtual de Asesoría) is an online platform operating since December 2015 through which Colombian citizens as well as public servants and entities can access complete and up-to-date information on public administration (e.g. regulation, jurisprudence and publications), receive comprehensive advice from experts through a virtual chat, and take part in online training courses.

The objectives of EVA are:

-

Promoting access to information.

-

Promoting the use of virtual interaction tools that facilitates communication between the institutions, public servants and citizens.

-

Providing guidance and advice in real time.

-

Promoting compliance with normativity about transparency and access to public information.

-

Providing opportunities for participation and interaction among public servants, institutions and citizens.

Since August 2016, EVA’s website also created a networking section where public officials can publish articles, create events, exchange messages and opinions, download newsletters and communicate with their colleagues from other entities (Red de los servidores públicos). Next to the latter section, EVA’s website includes the following sections:

-

Regulatory Manager: to date, it includes around 20 000 documents related to Public Service, including standards, jurisprudence of the Council of State, Constitutional Court and Supreme Court, concepts issued by Civil Service, Codes and Statutes.

-

Public Service indicators at national and regional level on issues of: Public Employment, Public Management, Transparency, Institutional Strengthening and Democratisation.

-

General Chat to provide specialised real-time advice by the organisation’s lawyers on public administration issues.

-

Virtual Training tutorials, presentations, video conferences and national and international training opportunities.

-

Virtual Library with over 100 publications related to participation, transparency and Citizen Service, Institutional Performance, Peace, Cultural Change, Labor Regime, Talent, Accountability, Public Employment Anti-Corruption Plan, Statement of Assets and Income, among others issues.

Source: Based on information provided by DAFP and EVA’s website: www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva.

Anchoring integrity in Human Resource Management