Chapter 6. Digital risk and trust1

Trust underpins most digital relationships and transactions and depends on the perception and the management of risk. This chapter examines trust concerns, in particular related to privacy and digital security risks, as barriers to the adoption of digital technologies, reviews trends in digital security and privacy incidents and online fraud, and discusses how to build trust in the digital economy, including through consumer protection. Policy and regulation aimed at enhancing trust in the digital economy are discussed in Chapter 2.

Introduction

Increasing connectivity and data-intensive economic activities – in particular those that rely on large streams of data (“big data”), the widespread use of mobile connectivity, and the emerging use of the Internet to connect computers and sensor-enabled devices (the Internet of Things [IoT]) – have the potential to foster innovation in products, processes, services and markets and to help address widespread economic and social challenges. These developments have been accompanied by a change in the scale and scope of a number of risks, relating in particular to digital security and privacy, with potential significant impacts on social and economic activities. Furthermore, as new business models emerge to take advantage of new opportunities, it may be more difficult for consumers to navigate through the resulting complexity of the evolving e-commerce marketplace. This combination underscores the need for an evolution in policies and practices to build and maintain trust.

Although challenging to measure, digital security incidents appear to be increasing in terms of sophistication, frequency and magnitude of influence. These incidents can affect an organisation’s reputation, finances and even its physical assets, undermining its competitiveness, ability to innovate and position in the marketplace. Individuals can suffer tangible economic and even physical harms as well as intangible harms such as damage to reputation or intrusion into their private life. In addition, digital security incidents can impose significant costs on the economy as a whole, including by eroding trust, not only in the affected organisations, but across sectors. In May 2017, computers in over 150 countries were infected by the WannaCry ransomware (i.e. malicious software that blocked access to the victim’s data until a ransom is paid). This significantly disrupted business operations in organisations worldwide such as the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), Spanish-based Telefónica, US-based FedEx and German-based Deutsche Bahn (BBC, 2017; Wong and Solon, 2017). Manufacturing firms such as Nissan Motor and Renault even stopped production at several production sites temporarily (Sharman, 2017).

The increasing connectivity of data-intensive activities adds layers of complexity, volatility and dependence on existing infrastructures and processes. In particular, the extension of the geographical reach of the digital services and their increasing interconnection beyond single jurisdictional and organisational control is challenging the existing governance frameworks of businesses and governments. Where these digital services are part of critical infrastructure networks, there is a growing risk for systemic failures to accumulate and affect society in multiple ways. The result is that risk in the digital economy is a cross-boundary, cross-sector and multi-stakeholder issue. What happens in a small business can affect a large business and all other actors within a value chain; what one actor (individual or group) does may affect many others. That said, organisations, whether functioning in the public or private sector, are undoubtedly benefiting from greater interconnectivity – driving innovation, efficiency and performance. The value chain ecosystem can also be used to address digital security risk, for example by requiring a certain level of security risk management along a supply chain.

Trust is essential in situations where uncertainty and interdependence exist (Mayer, Davis and Schoorman, 1995), and the digital environment certainly encapsulates those two factors. However, while digital technologies are evolving rapidly, policies and resultant practices related to trust too often assume a static world. The IoT, big data and artificial intelligence (AI) were perceived by policy makers in 2016 as the greatest challenges to ensuring beneficial policy settings (see Chapter 2). At current growth rates, it has been estimated that by 2020 there will be 50 billion “things” connected to the Internet (OECD, 2016a). For example, firms like Amazon, Apple and Google have already made big moves to enable AI-enabled services such as human-machine interaction via spoken word, while Facebook launched an AI effort, DeepText, to understand individual users’ conversational patterns and interests.

The potential advantages of these technological developments are significant but they also add new risks that could erode trust in the new technologies and the digital economy overall. The evidence reviewed in this chapter suggests that users (including individuals and businesses, and in particular small and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs]) are increasingly unsettled by the risks they may face within this new digital environment. A 2014 Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI)-Ipsos survey of Internet users in 24 countries on Internet security and trust suggests that 64% of respondents are more concerned about privacy than they were in the previous year. Perhaps most striking is the lack of confidence that they have control over their personal information.

This chapter reviews developments related to digital risks and trust with a focus on: 1) digital security; 2) privacy; and 3) consumer protection issues. Digital risks faced by businesses in respect to the protection of their intellectual property or other business risks such as the risk of lock-ins and other information and communication technology (ICT) investment-related business risks are beyond the scope of this chapter. The chapter is structured as follows:

-

The first section shows that trust concerns, and in particular privacy and digital security risks, are often a barrier to the adoption of digital technologies and applications including, but not limited to, cloud computing, e-commerce and e-government services for both individuals (including consumers) and businesses (in particular SMEs).

-

The second section then reviews trends in digital security and privacy incidents, as well as online fraud, and their social and economic effects. In doing so, this section discusses to what extent trust concerns highlighted in the previous section may be justified.

-

The third section discusses trends on how trust in the digital economy is built and reinforced from the perspective of individuals (including consumers) and businesses. These means range from transparent online reviews for consumers to risk management practices in businesses. This section does not discuss the role of public policies in enhancing trust in the digital economy, which is discussed in Chapter 2.

Key findings from this chapter include that with growing intensity of ICT use, businesses and individuals are facing more digital security and privacy risks. SMEs in particular need to introduce or improve digital security risk management practices. Meanwhile, consumers’ concerns about privacy add to their concerns about online fraud, redress mechanisms, and online product quality, which could limit trust and slow business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce growth. More generally, digital security and privacy concerns are inhibiting ICT adoption and business opportunities. Finally, emerging peer platform markets bring new trust issues, but also new opportunities to address them.

The role of digital risks and trust in the adoption of digital technologies and applications

Continued improvements in consumer and business access to broadband Internet, particularly through mobile devices and applications, have opened up new opportunities. For instance, there has been a significant rise in the use of cloud computing services among Internet users (Chapter 4). The share of individuals using e-government services (i.e. visiting or interacting with public authorities online) has also increased in recent years. And e-commerce has grown continuously with the uptake of the Internet (OECD, 2014) and at a faster rate than overall retail sales (Box 6.1).

From 2013 to 2018, the share of the Asia and Oceania region in global business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce is expected to increase from 28% to 37%, and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) has already emerged as the largest global B2C e-commerce market. Credit card penetration is an important factor facilitating e-commerce, notably in developing countries and among the younger generation (UNCTAD, 2015; 2016). More generally, innovation in the e-commerce marketplace now affords consumers better access to a wider variety of competitively priced goods and services, wider access to tangible and digital content products, easy to use and more secure payment mechanisms, and a growing number of platforms facilitating consumer to consumer transactions.

In OECD countries, B2C e-commerce has grown continuously and at a faster rate than overall retail sales. Recent figures in the United States show an annual increase of 15.8% for e-commerce as compared with growth in overall retail sales of 2.3%. E-commerce sales now account for 8.1% of total retail sales in the United States (US Department of Commerce, 2016); and roughly eight in ten individuals in the United States are online shoppers and 15% buy online on a weekly basis (Smith and Anderson, 2016). In the European Union (EU), the proportion of individuals that ordered goods or services online increased from 30% in 2007 to 53% in 2015, exceeding the European Union’s own targets (EC, 2015a). The most frequent reasons to shop online relate to convenience, price and choice according to the 2015 EU Scoreboard. Some 49% of surveyed consumers pointed to the advantage of being able to buy anytime, while 42% noted the time saved by buying online. In terms of price, 49% mentioned finding less expensive products online, while 37% cited the ease of comparing prices online. The advantages related to choice covered both the overall range of goods and services available as well as the fact that some products are only available online. Other reasons identified in the survey concerned information such as the ability to find consumer reviews (21%), the possibility of comparing products easily (20%), the ease of finding more information online (18%) and the possibility of delivery to a convenient place (24%). In terms of cross-border purchases, it appears that the main reasons driving online shopping relate to quality and choice (European Commission, 2015a).

Some data provided by the US International Trade Administration show regional differences in e-commerce trends. According to Morgan Stanley research, 41% of online shoppers in the United States buy online because of lower prices, while 49% globally do so for the same reason. Another example is the ease to compare prices: 25% cited this reason in the United States while 32% did so globally. While a similar number of people in emerging economies, Europe, and the Americas and Asia-Pacific bought products cross-border due to non-availability at domestic level (74%, 74% and 72%, respectively), there are large disparities when it comes to looking for higher quality products abroad (49% in emerging economies, 8% in Europe, and 15% in the Americas and Asia-Pacific) (US International Trade Administration, 2016).

The types of goods and services consumers acquire online are increasingly varied. In Australia, the most common industry sectors for online purchases were: electronics/electrical goods; clothing, footwear, cosmetics and other personal products; gift vouchers, travel services and entertainment (Australian Government, 2016). In the European Union, clothes and sport goods (60% total, and 67% for the 16-24 year-old age group) is the most popular type of goods and services purchased online, followed by travel and holiday accommodation (52%); household goods (41%); tickets for events (37%); and books, magazines and newspapers (33%). A good proportion of the 16-24 year-old age group also purchased games software, other software and upgrades (26%), and e-learning material (8%) (EC, 2015a), which suggests that e-commerce now encompasses digital content products.

However, there are still huge variations in the use of digital technologies among individuals and businesses, and across countries, in particular when it comes to more advanced platforms (see Chapter 4; OECD, 2016b). The majority of individuals and businesses are still using digital technologies for rather basic applications, such as for e-mail and information retrieval through websites. E-commerce adoption, for instance, remains below its potential, although it is progressing at a significantly faster rate than overall retail sales. The share of e-commerce sales stands at only 18% of total turnover on average in reporting countries, and up to 90% of the value of e-commerce comes from business-to-business transactions over electronic data interchange applications (Chapter 4).2 Furthermore, only of 57% Internet users in OECD countries reported using the Internet to order products online and 22% to sell products online, compared to an average of 90% of Internet users reporting using e-mails and about 80% using the Internet to obtain information on goods and services.3 At the same time, while more than 90% of businesses are connected to the Internet and almost 80% have a website, only 40% use digital technologies to purchase products and even less (20%) sell products online.

E-commerce is not the exception. The adoption of other digital technologies and applications remains particularly low, in particular among individuals and SMEs. For example, the adoption of e-government services varies significantly across countries. More importantly, the share of people submitting electronic forms (instead of only downloading public sector information) remains particularly low (with only 35% of OECD Internet users undertaking this activity in 2016). At the same time, many businesses, and in particular SMEs, still lag behind in adopting more advanced digital technologies and applications such as cloud computing, supply-chain management, enterprise resource planning, and radio frequency identification. For example, only 20% of businesses had adopted cloud computing in 2016 and less than 10% big data analytics, despite their potential for boosting productivity (see Chapter 4).

There is strong evidence showing that Internet users (including individuals and businesses, and in particular SMEs) are increasingly concerned about digital risks and that these concerns may have become a serious barrier for the adoption of digital technologies and applications. A 2014 CIGI-Ipsos survey of Internet users in 24countries on Internet security and trust suggests that 64% of respondents are more concerned about privacy than they were one year ago. In a special 2014 Eurobarometer survey on digital security, online consumers in the European Union (EU) reported their top two concerns to be the misuse of personal data and the security of online payments (EC, 2015b). The level of concern in both areas is up from 2013, with fear of personal data misuse increasing from 37% to 43% and security concerns from 35% to 42%.

The low adoption of some digital technologies and applications cannot only be explained by a lack of trust. There are a number of other factors, among which the education gap has been identified as the most important one (OECD, 2014; 2016c). While users with a tertiary education perform on average more than seven different online activities, those with at most a lower secondary education perform less than five (OECD, 2014). In a similar manner, for businesses, the lack of skills in the labour market is one of the major barriers for the adoption of digital technologies (OECD, 2016c). However, it is noticeable that the applications for which adoption is slow are to a significant extent those that are associated with higher risks for either individuals or businesses, or for both. These applications typically involve the extensive collection and processing of personal data, including financial data (e.g. e-commerce), or are applications that can lead to a higher degree of dependencies (e.g. cloud computing).

The following sections present available evidence showing the extent to which lack of trust, and in particular privacy and security concerns, are a major source of concern and thus potential barriers to the adoption of digital technologies for both individuals and businesses.

Digital security and privacy concerns can prevent consumers from engaging in online transactions

Digital risks and lack of trust are often indicated as the most common reasons that individuals (consumers) with access to the Internet do not use some digital technologies and applications and for not engaging in online transactions. Concerns include the growing risk of online fraud and the misuse of personal data as well as the rising complexity of online transactions and related terms and conditions. This is compounded by uncertainties about the redress mechanisms available in case of a problem with an online purchase. The following sections discuss these issues in more detail.

Individuals are increasingly concerned about digital security and privacy, but there are significant variations across countries as well as across digital technologies and applications

Digital security and privacy are among the most challenging issues raised by digital services, including e-commerce. Individuals perceive digital security as a major issue, in particular where there are significant risks of personal data breaches and identity theft. Concerns thus relate to the wealth of personal data that online activities generate, which, while enabling organisations to sketch rich profiles about individuals, also bring risks to both the individuals and the organisation. According to Special Eurobarometer surveys (EC, 2015c; 2013), for example, when using the Internet for online banking or shopping, the most common concern is about “someone taking or misusing personal data” (mentioned by 43% of Internet users in the European Union compared to 37% a year ago), before the “security of online payments” (42% compared to 35% a year ago). This is in line with the observation that around 70% of Internet users in Europe are still concerned that their online personal information is not kept secure by websites. That said, security concerns by individuals are not limited to the confidentiality of their personal data. Many are also concerned about the availability of digital services. For example, in 2014, around half of European Internet users were concerned about not being able to access online services because of digital security incidents (compared to around 37% a year earlier).

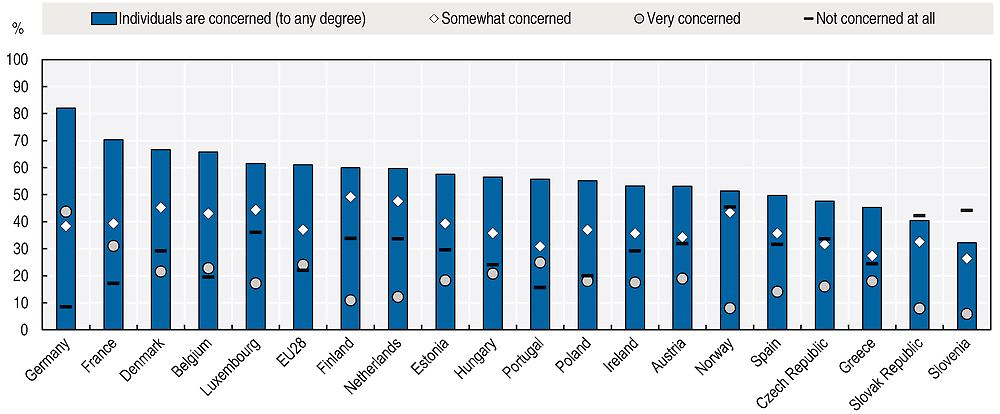

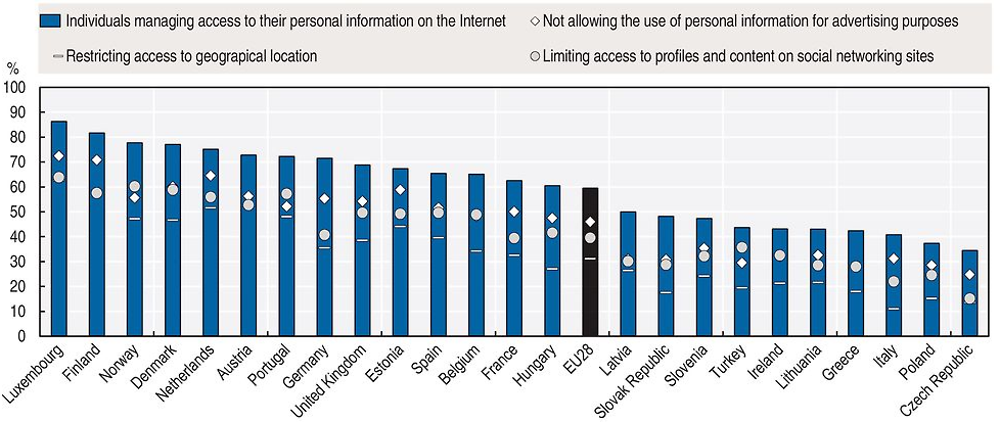

Concerns about the misuse of personal data go beyond security (e.g. personal data breaches), and include most notably concerns about the loss of control over personal data. According to a 2014 Pew Research Centre poll, for example, 91% of Americans surveyed agree that consumers have lost control of their personal information and data (Madden, 2014). The percentage of people who “agree” or “strongly agree” that it has become very difficult to remove inaccurate information about them online is as high as 88%. The share of social networking site users in the United States concerned with third-party access by businesses and governments is estimated to be 80% and 70% respectively. That said, 55% “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement: “I am willing to share some information about myself with companies in order to use online services for free” (Madden, 2014). Similarly in the European Union, “two-thirds of respondents (67%) are concerned about not having complete control over the information they provide online.” (EC, 2015b) More than half (56%) say it is very important that tools for monitoring their activities online only be used with their permission. Meanwhile, “roughly seven out of ten people are concerned about their information being used for a different purpose from the one it was collected for.” Across the European Union in 2016, more than 60% of all individuals were concerned about their online activities being recorded to provide them with tailored adverts (Figure 6.1). In Germany, France and Denmark the share was even much higher, at 82%, 70% and 68% respectively.

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

Trust concerns could incite consumers to change their online behaviour, with potential negative effects on digital service adoption

Privacy and security concerns have led Internet users to be more reluctant in providing personal data and in some cases even in using digital services at all. Today, for example, 34% Internet users in the European Union say that they are less likely to give personal information on websites. Six out of ten respondents have already changed the privacy settings on their Internet browser (compared to three in ten in 2013; see OECD, 2014). Over one-third (37%) use software that protects them from seeing online adverts and more than a quarter (27%) use software that prevents their online activities from being monitored. Overall 65% of respondents have taken at least one of these actions. Individuals are also more demanding in respect to the level of security of the digital services they use. A survey among EU individuals shows that “more than seven in ten (72%) say it is very important that the confidentiality of their e-mails and online instant messaging is guaranteed”, and “almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) totally agree they should be able to encrypt their messages and calls, so they are only read by the recipient” (EC, 2016b). The changing behaviour is confirmed by a recent survey of 24 000 users in 24 countries in 2014 commissioned by the CIGI, which reveals that only 17% of users said they had not changed their online behaviour in recent years. The rest expressed a variety of behavioural change from using the Internet less often (11%) to making fewer purchases and financial transactions online (both around 25%). While the increasing occurrence of data breaches in the media can be seen as a determinant factor, some note that “some users may be concerned by other factors, including pervasive surveillance or how their data is collected and used by businesses” (Internet Society, 2016).

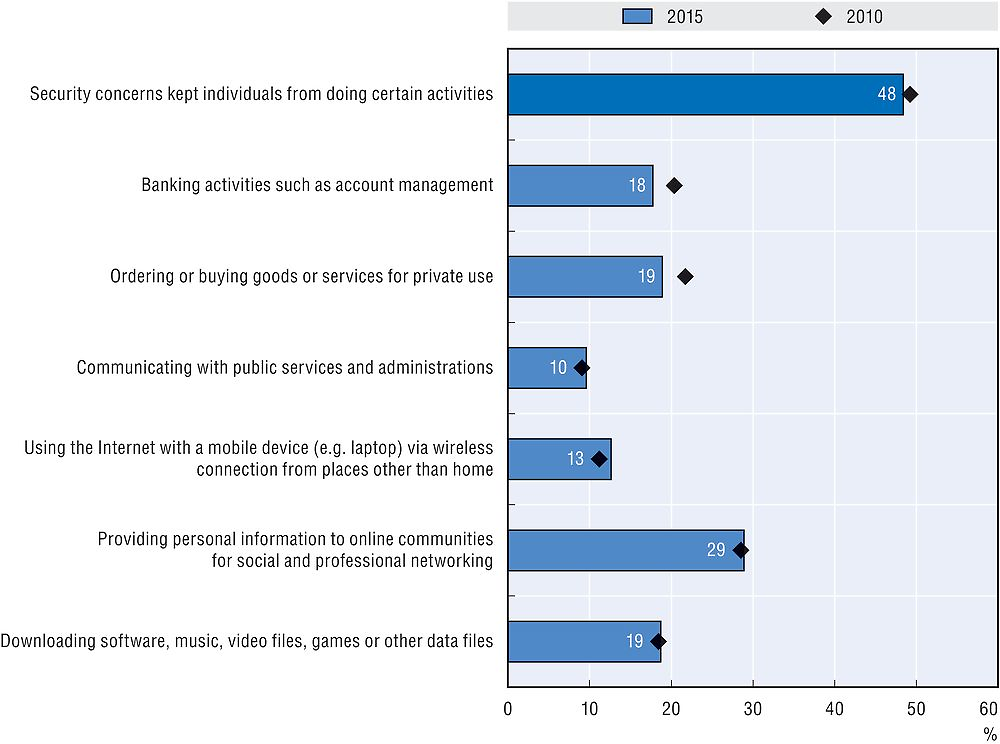

As individuals become more concerned about privacy and security, some have started to avoid using digital services. The behavioural change of consumers due to digital security and privacy concerns could negatively affect B2C e-commerce. Evidence confirms that many consumers remain reluctant to purchase online because of security and privacy concerns (OECD, 2014). There is considerable variation in the exact reasons though, even when only looking only at trust issues. Some cite fears around the misuse of personal data and security of online payments and in many cases identity theft is a major source of concern. Among European Internet users, for example, almost half abstained from certain online activities in 2015 because of security concerns (Figure 6.2). The most frequent activities were related to the risk of personal data misuse and of economic losses, for instance through identity theft. They included (in order of significance): providing personal information to online communities for social and professional networking (almost 30% of Internet users), e-banking and e-commerce (both around 20% of Internet users).4 When also taking privacy concerns into account the share is higher. In 2015, one-fourth of Internet users in the EU cited privacy and security concerns as the main reason for not buying online. Almost 15% all individuals in the European Union did not use cloud computing because of privacy or security concerns in 2014 (Figure 6.3). In Austria, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and Switzerland the share is as much as 20% or 25%. In the United States, the 2015 US Census Bureau survey of households online reported that 63% of the online households were concerned about identity theft and of these 35% refrained from conducting financial transactions online during the year prior to the survey. Similarly, of the 45% of online households concerned about credit card or banking fraud, 33% declined to buy goods or services using the Internet (NTIA, 2016); this is the equivalent of 15% of online households. The high variation in perceptions of security and privacy risks across countries with comparable degrees of law enforcement and technological know-how suggests that cultural attitudes towards online transactions play a significant role.

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

However, lack of trust towards Internet businesses and digital services must not always translate into a barrier for adopting digital services. Although a majority of people may be uncomfortable about Internet companies using information about their online activity to tailor adverts or are concerned about the recording of their activities via payment cards and over mobile telephones, a large majority of individuals may accept this. In the European Union, for example, more than half of all individuals are concerned about their privacy, yet “a large majority of people (71%) still say that providing personal information is an increasing part of modern life and accept that there is no alternative other than to provide it if they want to obtain products of services” (EC, 2015b). Meanwhile, the survey also reveals that “more than six out of ten respondents say that they do not trust landline or mobile phone companies and Internet service providers (ISPs) (62%) or online businesses (63%)”. However, the share of European households without access to the Internet that cite privacy or security concerns as the main reason for not having an Internet connection is low, although it increased from 5% in 2008 to 9% in 2016.5 At the same time, in the United States, where the share of households indicating privacy and security concerns as a main reason for not having an Internet connection at home also increased (by 1 percentage point compared to 2009), albeit from an even lower level (at 1.4% of all households) in 2015. An increasing share of people not using the Internet due to privacy and security concerns can also be observed in Brazil, where up to 12% of households without an Internet connection cited privacy and security concerns as a reason.6

Uncertainties about mechanisms for redress and the quality of products sold online could also slow the growth of business-to-consumers e-commerce

With the increasing complexity of the online environment and the emergence of new e-commerce business models, consumers are now faced with further challenges as well as opportunities. In its work leading to the 2016 revisions to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Consumer Protection in E-commerce (OECD, 2016d), the Committee on Consumer Policy identified a number of key developments in e-commerce that pose challenges for consumers. These developments included the growth of non-traditional payment mechanisms, such as mobile phone bills or prepaid cards; new types of digital content products, such as mobile applications (apps) or e-books; and new types of online business models, such as those involving consumer-to-consumer or peer transactions facilitated by online platforms and those involving “free” goods and services provided in exchange for consumers’ personal data.

Consumers’ propensity to engage in domestic or cross-border online transactions may be facilitated or inhibited not only by perceived benefits and risks of e-commerce but also by consumer awareness of key consumer rights online and capacity to seek redress if these rights are violated. When Australian consumers were asked if they believe they have the same rights when purchasing online as they do in a physical store, more than one-third of respondents reported that they did not believe they have the same rights online or were unsure about the situation. In terms of actual problems experienced by Australian consumers, 23% were related to online purchases (Australian Government, 2016). Some studies suggest knowledge of consumer rights increases with age: for instance, Italian consumers over 54 are more aware of their rights, as well as more engaged and skilled, than consumers in the 15-24 age bracket (EC, 2016a). EU consumers have raised concerns beyond data protection and security with about one-quarter reporting concerns about the infringement of consumer rights related to redressing problems with the goods. In addition, 19% of the surveyed EU consumers expressed concerns about the possibility of buying unsafe or counterfeit goods (EC, 2015a).

Consumer protection enforcement agencies are a key source of information about the problems facing consumers online. These agencies work together through the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network (ICPEN), which has members from over 60 countries. In 2015, ICPEN members recognised misleading and inadequate information disclosures related to pricing information as a key problem for online consumers. As part of an internationally co-ordinated “sweep” of online pricing practices in travel and tourism, ICPEN members identified misleading or deceptive conduct such as “drip pricing,” which resulted in the delayed disclosure of final prices, fees and terms and conditions to consumers, false reference prices and best price claims, non-existent discounts and time-sensitive representations, and a lack of cancellation and refund information.

Another element affecting consumer trust in a global context is the range of unsafe products which are available in e-commerce, as revealed by an OECD product online sweep co-ordinated by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in April 2015. During the sweep, product safety authorities in 25 countries inspected 3 categories of goods that had been identified in their country as: 1) banned and recalled products; 2) products with inadequate product labelling and safety warnings; and 3) products that did not meet voluntary or mandatory safety standards (OECD, 2016e).

Of the nearly 700 products inspected for the purpose of detecting banned or recalled products, 68% were available for sale online. Out of the 880 products which were inspected to detect inadequate labelling and safety warnings, 57% were not supported by adequate labelling information on relevant websites, and 22% showed incomplete labelling information. Moreover, a small majority of the 136 products inspected for the purpose of detecting products which did not comply with voluntary and mandatory safety standards did not comply with such standards. A key challenge suggested by the sweep is the share of unsafe products bought online from overseas, with goods banned in one country due to safety concerns being accessible to buyers from another country without knowledge of the ban. Another example is labels and warnings in a foreign language or products that do not meet voluntary and mandatory safety standards, and which are more prevalent in a cross-border context (OECD, 2016e).

Missed business opportunities over digital security risk concerns are still significant

Current surveys on the diffusion of ICT tools and activities in enterprises indicate that companies, and in particular SMEs, are not making the most of the business opportunities the online environment has to offer. The reasons cited for not using digital technologies to their full potential include technical issues, such as reorganising business processes and systems; skills, including a lack of specialist knowledge or capability; and increasingly, trust issues. SMEs in particular, which account by far for the largest share of all businesses in OECD countries, do not yet have full confidence in the digital solutions on offer. The potential of loss of consumer trust, damage to reputation, negative impacts on revenue, etc., from a digital security incident are the main reasons for these concerns. The following sections discuss in more detail major trust issues related to digital security concerns due to the enhanced use of external digital services.

Digital security risk has become a concern for organisations of all types

Companies recognise that digital technologies are key to greater productivity, but most express significant concerns over digital security risk, which makes adoption challenging. Digital security concerns vary according to firm size and country, and will depend on the digital technologies and applications, with the more advanced ones creating greater concerns. E-commerce adoption, for example, and in particular mobile e-commerce, remains below its potential, with security concerns frequently cited as an impediment by a significant share of businesses. According to Eurostat data, for instance, more than a third of all firms stated that security-related risks prevented or limited the use of mobile Internet in 2013, and almost a third of these firms stated that a mobile connection to the Internet was needed for business operation. In Finland, France and Luxembourg, more than 50% of all businesses do not use mobile Internet to its full potential due to security concerns even though, as in the case of Finland, more than a third of all firms would need a mobile connection for their business operation.

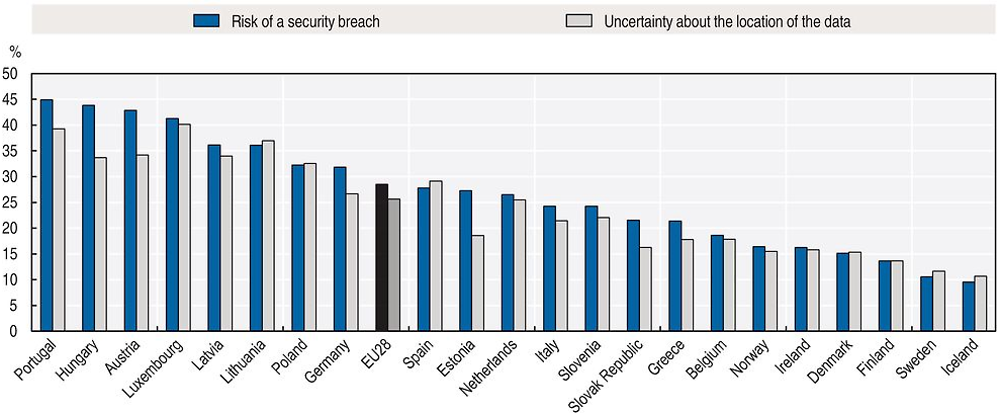

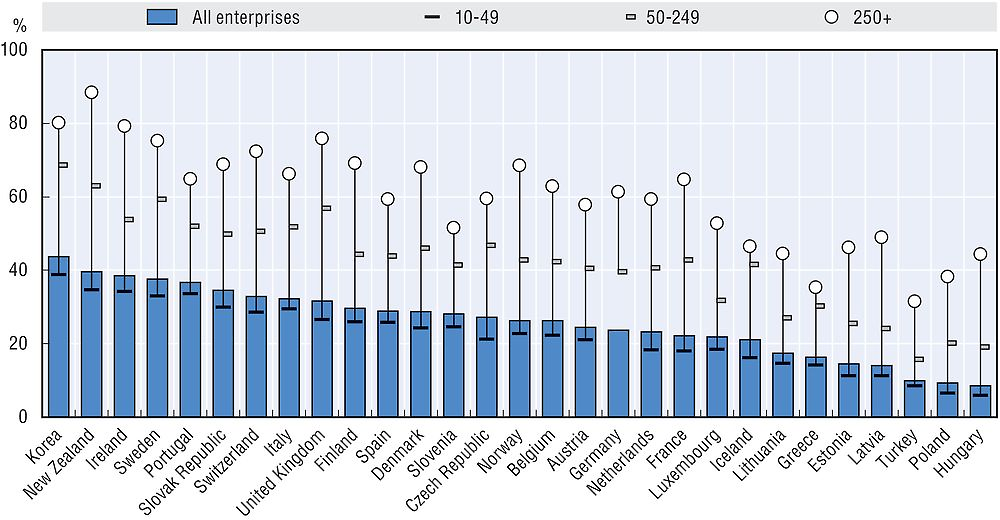

It is even more apparent in the case of cloud computing that trust issues have become a barrier to adoption. In the OECD area, only 20% of businesses had used cloud computing by 2014, with SMEs being more reluctant compared to large firms (40% of firms with 250 or more employees compared to 20% of firms with 10 to 49 employees). In some countries the gap between large and small firms is great. In the United Kingdom, for example, 21% of all smaller enterprises (10 to 49 employees) are using cloud computing services compared to 54% of all larger enterprises. A similar gap can be observed in other countries (see Chapter 4). Risk of security breach is perceived as a major barrier to cloud computing adoption by businesses. Almost 30% of all businesses in the European Union do not use the cloud because of security concerns. The share ranges from almost 45% in Austria, Hungary, Luxembourg and Portugal to 10% to 15% in the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Norway and Sweden), which are also those countries where the rates of cloud computing adoption by businesses are the highest among OECD countries (Figure 6.4).

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

Loss of control of data is perceived as a major digital risk for businesses considering using Internet-based services

In a survey of European SME perspectives on cloud computing, the security of corporate data and potential loss of control featured highly among the concerns for SME owners (ENISA, 2009). Loss of control in the case of cloud computing is partly related to uncertainties about the location of the data, which is perceived across countries as significant a barrier to cloud computing adoption as the risk of security incidents (Figure 6.4). In addition, there is another major challenge which is related to the lack of appropriate open standards and the potential for vendor lock-in due to the use of proprietary solutions: applications developed for one platform often cannot be easily migrated to another application provider (OECD, 2015b).

The lack of open standards is a key problem, especially when it comes to the model of “platform as a service” and to digital services based on this model. In this service model, application programming interfaces are generally proprietary. Applications developed for one platform typically cannot easily be migrated to another cloud host. While data or infrastructure components that enable cloud computing (e.g. virtual machines) can currently be ported from selected providers to other providers, the process requires an interim step of manually moving the data, software and components to a non-cloud platform and/or conversion from one proprietary format to another. Consequently, once an organisation has chosen a service provider, it is – at least at the current stage – locked in (OECD, 2015b). Some customers have raised the difficulty of switching between providers as a major reason for not adopting cloud-based services. Almost 30% of all businesses in the European Union, for example, had not used cloud computing to its full potential in 2014 because of perceived difficulties in unsubscribing or changing service providers (Figure 6.5). A major difficulty of switching providers is that users can become extremely vulnerable to providers’ price increases. This is all the more relevant as some IT infrastructure providers may be able to observe and profile their users to apply price discrimination to maximise profit (OECD, 2015b). See the section below on “empowering individuals and businesses” for trends on the use of mechanisms for consumers to control their personal data and see Chapter 2 for trends on policy initiatives to promote data portability.

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

Trends in incidents affecting trust in the digital economy

Concerns about potential losses and harms related to the use of digital technologies are in many cases a result of incidents experienced directly or indirectly by users of digital technologies. A large portion can be assigned to digital security incidents, i.e. the disruption of the confidentiality, integrity and availability7 of the digital environment underlying social and economic activities. Meanwhile, these incidents appear to be increasing in terms of sophistication, frequency and magnitude of impact. For example, personal data breaches8 – more precisely the breach of the confidentiality of personal data as a result of malicious activities or accidental losses – can cause significant economic losses to the business affected (including loss of competitiveness and reputation), but certainly will also cause harm as a result of the privacy violation of the individuals whose personal data have been breached. In addition, further consumer detriment may result from a data breach, such as harm caused by identity theft.

Losses and harm in the digital economy are not, however, always caused by digital security incidents. For instance, individuals, including consumers, may see their privacy violated as a result of the deceptive, misleading, fraudulent or unfair use of their personal data by organisations. This may be one reason for the increasing number of complaints received by national privacy protection authorities (excluding complaints related to personal data breaches). The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, for instance, accepted 309 complaints in 2015, an increase of 49% from five years earlier, when 207 complaints were accepted.9 Significant consumer detriment can also be caused by misleading or inadequate information about the business, products and transactions, as well as by low quality or unsafe products made available in online markets as highlighted above. Furthermore, businesses relying on the digital environment may suffer from losses and harms not caused by digital security incidents, but by the violation of their intellectual property rights, including in particular their copyrights, on products made available in digital formats.10 Related to these risks are interdependencies that are created as organisations and societies become more and more interconnected, leading to a higher systemic risk in particular, as critical infrastructures are involved.

Digital security incidents are increasing in terms of sophistication and magnitude of impact

In recent years large and small organisations as well as individuals appear to be subject to more frequent and severe digital security incidents (OECD, 2016f).11 These incidents can disrupt the availability, integrity or confidentiality of information and information systems on which economic and social activities rely, and they can be intentional (i.e. malicious) or unintentional (e.g. resulting from a natural disaster, human error or malfunction). From an economic and social perspective, security incidents can affect an organisation’s reputation, finances and even physical activities, damaging its competitiveness, undermining its efforts to innovate and its position in the marketplace.

Digital security incidents have taken a variety of forms. Criminal organisations are increasingly active in the digital environment. As innovation is becoming more and more digital, industrial digital espionage is likely to further rise. Some governments are also carrying out online intelligence and offensive operations. In some cases, the motive may be political or the attacks may be designed to damage an organisation or an economy. It was, for example, the case with the attack that targeted Sony Pictures Entertainment at the end of 2014, exposing unreleased movies, employee data, e-mails between employees, and sensitive business information like sales and marketing plans (BBC, 2015).

The risk of digital security incidents is growing with the intensity of ICT use

Across surveys undertaken over the past decade, it has consistently been found that over half of businesses and individuals report that they did not experience a digital security incident of any kind. There are, however, considerable cross-country variations. The share of businesses experiencing digital security incidents, for instance, ranges from around a third in Japan and Portugal to below 10% in Hungary, Korea and the United Kingdom12 in 2010 or later (Figure 6.6).13 A similar variation can be observed in the case of individuals: in the European Union, 20% to 30% of all individuals stated that they experienced a digital security incidence in 2015, compared to below 5% in Mexico and New Zealand (Figure 6.7).14

Notes: For European countries, data are only available for 2010. For New Zealand, data refer to 2016. For Japan and Switzerland, data refer to 2015. For Korea, they refer to 2014. For Canada, data refer to 2013. Canada, Japan, Korea and Switzerland follow a different methodology.

Source: OECD, ICT Access and Usage by Businesses (database), http://oe.cd/bus (accessed June 2017).

Notes: Data for Korea refer to 2016 for all individuals but the breakdown by level of educational attainment refers to 2014. Data for New Zealand and Switzerland refer to 2014. Data for Iceland refer to 2010. Data for Korea, Mexico, New Zealand and Switzerland follow a different methodology.

Source: OECD, ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals (database), http://oe.cd/hhind (accessed June 2017).

Evidence suggests that the actual proportion varies more significantly depending on the target population. For businesses that do experience an incident, for example, the number of incidents detected increases with firm size. In the case of individuals, the rate of incidents detected tends to increase with the level of education. One explanation could be that larger businesses and more educated individuals may have better detection capacities. The higher rate of experiencing an incident could, however, simply be because larger businesses have larger information technology (IT) infrastructures, which in turn are more likely to incur at least one incident. Similarly, evidence shows that individuals are more likely to use digital technologies and applications more intensively the more educated they are (see Chapter 4). The greater the intensity of usage, the greater the likelihood of experiencing a digital security incident.

Recent surveys confirm that large businesses are more likely to experience digital security incidents than small businesses. The 2016 Cyber Security Breaches Survey focusing on the United Kingdom showed that the proportion of businesses that had experienced an incident in the previous 12 months increased with business size. While overall 24% of all businesses surveyed had had an incident in the last 12 months, only 17% were micro businesses, 33% were small businesses, 51% were medium-sized business and 33% were large businesses. That said, many SMEs are not sufficiently aware of the actual digital security risks and the incidents they may have been victim of. The 2016 Ponemon State of Cybersecurity in Small and Medium-Sized Businesses, for example, found that 55% of respondents had experienced a cyber-attack in the past 12 months but that 16% were unsure. This calls for a careful interpretation of existing statistics and the need for further efforts to strengthen the evidence base in digital security and privacy.

The frequency and magnitude of security incidents differ substantially depending on the type of incident

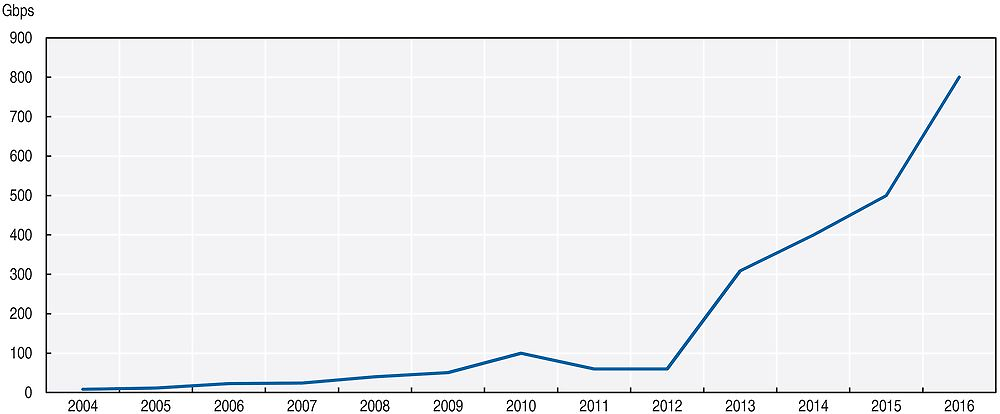

Available evidence suggests that viruses/malware remain the most common type of digital security incident experienced.15 Some surveys also highlight the increase in incidents related to phishing and social engineering. Other surveys show that denial of service (DoS)16 attacks tend to affect fewer businesses, although the share of affected businesses remains significant. More importantly, the sophistication and magnitude of DoS attacks are growing rapidly, with an increasing number of incidents based on the exploitation of IoT devices to generate large packet floods (Box 6.2). In 2015, several attacks used over 300 Gigabits per second (Gbps) and one peaked at 500 Gbps, which represents a tenfold increase compared to 2009 (Arbor Networks, 2016). In 2016, the largest attack reported was 800 Gbps, with several surveyed organisations reporting attacks of between 500 Gbps and 600 Gbps (Figure 6.8) (Arbor Networks, 2017). Fraud was also reported as an issue, but more for larger businesses than for smaller ones. That said, it should be noted that all these incidents may be inter-related. For instance, web-based attacks, phishing, or social engineering and malware more generally may be used to gain access to servers or IoT devices which may then be used to take part of a distributed DoS attack.

With the Internet of Things (IoT) the risk of security incidents will most likely increase. Not only can the components of the IoT become the target of digital security incidents, with the consequence of disrupting physical systems, but in addition, IoT components can also be used as means for targeting digital systems, including through distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. In 2016, for instance, major Internet sites such as Netflix, Google, Spotify and Twitter were not accessible due to thousands of IoT devices – like digital video recorders and web-connected cameras – that were hacked and used for distributed DDoSs (see Hautala, 2016; Smith, 2016).

Like industrial control systems, the IoT bridges the digital and the physical world: through various types of sensors, connected objects can collect data from the physical world to feed digital applications and software, and they can also receive data to act on the environment through actuators such as motors, valves, pumps, lights and so forth. Thus, digital security incidents involving the IoT can have physical consequences: following a breach of integrity or availability, a vehicle might stop responding to the driver’s actions, a valve could liberate too much fluid and increase pressure in a heating system, and a medical device could report inaccurate patient monitoring data or inject the wrong amount of medicine. As with the industrial control systems that have long operated in some sectors, the potential exists that such physical consequences as human injury and supply-chain disruption could result from digital security incidents affecting IoT devices. In 2015, for example, researchers took control of a Jeep Cherokee remotely, without prior access to the car. They wirelessly interfered with the accelerator, brakes and engine. Following this experiment, Fiat Chrysler recalled 1.4 million vehicles (Greenberg, 2015a; 2015b).

The IoT is rarely a stand-alone building block isolated from other digital components. Instead, all digital components in an organisation or on a personal network will often need to be considered as interconnected and interdependent. Vulnerabilities or incidents affecting parts of an organisation’s information system that may seem unrelated to the IoT can affect it, as much as the exploitation of IoT components can have consequences in other parts of a system. For example, in 2015, a security firm investigated a hospital information system where attackers exploited a vulnerability in a networked blood gas analyser to ultimately infect the entire hospital IT department’s workstations (Storm, 2015). In October 2016, as another example, major websites including Twitter, Netflix, Spotify, Airbnb, Reddit, Etsy, SoundCloud and The New York Times were inaccessible to people after a company that manages critical parts of the Internet’s infrastructure was under attack. This attack was based on hundreds of thousands of IoT devices like cameras, baby monitors and home routers that had been infected with software that allows hackers to command them to flood a target with overwhelming traffic (Perlroth, 2012).

Source: Based on OECD (2016a), “The Internet of Things: Seizing the benefits and addressing the challenges”, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlwvzz8td0n-en.

Note: Gbps = Gigabits per second.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Arbor Networks (2016), Worldwide Infrastructure Security Report Volume XI, www.arbornetworks.com/images/documents/WISR2016_EN_Web.pdf; Arbor Networks (2017), Worldwide Infrastructure Security Report Volume XII, www.arbornetworks.com/insight-into-the-global-threat-landscape.

In the 2012 ICSPA survey in Canada, for example, the category with the highest average number of incidents per business was “phishing, spear phishing, social engineering”. The 2016 Ponemon State of Cybersecurity in Small and Medium-Sized Businesses, as another example, found that the most commonly experienced attacks (for SMEs) were web-based attacks, phishing/social engineering and general malware. In the National Small Business Association’s Year End Economic Reports for 2014 and 2015 (NSBA 2015, 2016), it was found that the highest proportion of businesses experienced a service interruption due to digital security incidents. The most common impact of an incident, according to the survey, was “service interruption” in both 2014 and 2015. A relatively small proportion of respondents reported impacts suggestive of a data breach (“sensitive information and data was stolen” or “information about and/or from my clients was stolen”) or fraud (“the attack enabled hackers to access my business bank accounts/credit card[s]”).

The cost of digital security incidents is significant but still difficult to assess

As noted above, digital security incidents can have various types of consequences for organisations: undermined reputation when the brand is exposed, loss of competitiveness when trade secrets are stolen, financial loss resulting from the attack itself (e.g. in sophisticated scam schemes17 ), from lost business, disruption of operations (e.g. sabotage), recovery costs or legal proceedings and fines.18 It is difficult to estimate the actual cost of incidents: organisations are often reluctant to share potentially damaging information, intellectual assets are difficult to value and, in many instances, organisations do not even report incidents, such as when there is no legal obligation to do so, for example in cases of theft of trade secrets and sabotage. It is also difficult to assess the cost of digital security incidents outside the organisation, for example to individuals and society. Also, different incidents will have different costs. Rarely are the estimates disaggregated by incident type.

As a result, there are no official statistics, data sources or widely recognised methodologies to measure the aggregate cost of incidents. Thus, much of the evidence is anecdotal. Some studies provide interesting aggregated estimates, which should nevertheless be treated cautiously. Examples include the joint study by the US Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS, 2014) and Intel McAfee, which estimated that the likely annual cost to the global economy from cybercrime is between USD 375 billion and USD 575 billion. According to this source, the costs of cybercrime would range from 0.02% of gross domestic product in Japan to 1.6% in Germany, 0.64% in the United States and 0.63% in China. Other studies provide firm-level estimates based on surveys. That being said, these also should be treated cautiously, given that they suffer from survey-specific issues, and in particular selection bias. Furthermore, costs estimated based on some of these surveys can fluctuate significantly over years, as a result of the “fat tailed” distribution. As a result, mean or median costs are hard to interpret, in particular when statistics are broken down by business size or sectors are missing. In NSBA (2015, 2016), for instance, the estimated cost of digital security incidents for the average firm fluctuates substantially from year-to-year: from USD 8 700 in 2013 to USD 20 750 in 2014 and USD 7 115 in 2015.

The 2016 Cyber Security Breaches Survey undertaken in the United Kingdom found that the average cost of all breaches, in absolute terms, was higher for micro- and small enterprises than for medium-sized enterprises. The mean remained quite stable, which indicates that a small proportion of incidents in a small proportion of businesses are likely responsible for a large proportion of total costs (Table 6.1). The 2016 Ponemon State of Cybersecurity in Small and Medium-Sized Businesses confirms that small businesses tend to lose less than large businesses. In particular, it shows that the mean cost/loss associated with incidents increased with firm size. That said, the consequences of some incidents may be harder to weather for SMEs even if costs/losses are smaller compared to those experienced by large organisations.19 According to a 2011 study cited by the US House Small Business Subcommittee on Health and Technology, for example, roughly 60% of small businesses close within six months of a digital security attack (Kaiser, 2011).

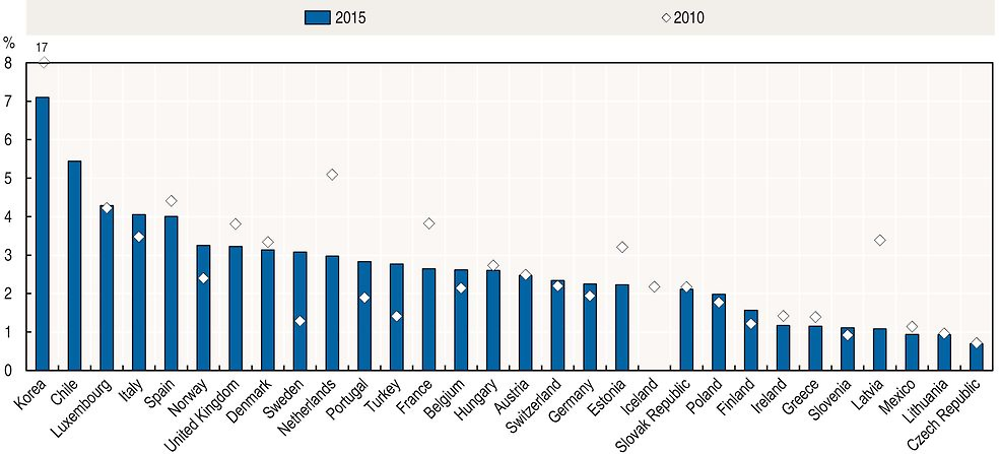

Privacy risks are amplifying with the collection and use of big data analytics

A growing number of entities, such as online retailers, ISPs, financial service providers (i.e. banks, credit card companies and so forth), and governments are increasingly collecting vast amounts of personal data.20 With that comes an increasing risk of privacy violations. In 2015, around 3% of all individuals across OECD countries for which data are available reported having experienced a privacy violation within the last 3 months (Figure 6.9). In some countries the share can be much higher, such as in Korea (above 7%), Chile (almost 6%) and Luxembourg (almost 5%). In many countries, such as Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Turkey, this share had increased significantly compared to 2010. Personal data breaches – more precisely the breach of the confidentiality of personal data as a result of malicious activities or accidental losses – are a major cause of privacy violations. In addition, individuals’ privacy can be affected by the extraction of complementary information that can be derived, by “mining” available data for patterns and correlations, many of which do not need to be personal data. Both risks, personal data breaches and privacy violation resulting from the misuse of big data analytics, are discussed further below.

Notes: Data for Chile, Mexico and Switzerland refer to 2014. Data for Iceland refer to 2010. Chile, Korea, Mexico and Switzerland follow a different methodology.

Source: OECD, ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals (database), http://oe.cd/hhind (accessed June 2017).

Personal data breaches have increased in terms of scale and profile

Digital security incidents affecting the confidentiality of personal data, commonly referred to as “data breaches”,21 have increased as organisations collect and process large volumes of personal data. In 2005 ChoicePoint – a consumer data aggregation company – was the target of one of the first high-profile data breach involving over 150 000 personal records.22 The company ended up paying more than USD 26 million in fees and fines. In 2007, retail giant TJX announced that it was the victim of an unauthorised computer system intrusion that affected over 45.7 million customers and cost the company more than USD 250 million. Since then, data breaches have become almost commonplace. According to a study commissioned by the UK government, 81% of large organisations suffered a security breach in 2014 (UK Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2014).23 Data breaches are not limited to the private sector, as evidenced by the theft in 2015 of over 21 million records stored by the US Office of Personnel Management, including 5.6 million fingerprints, and by the Japanese Pension Service breach that affected 1.25 million people (Otake, 2015).

An accurate estimate of the total cost of personal data breaches is hard to calculate. As argued above, available estimates have to be treated with caution, given that not all breaches are discovered, and when they are discovered, not all breaches are fully disclosed. Available estimates indicate a range of magnitude that strongly suggests that personal data breaches have a significant economic cost to society. One firm-level study by the Ponemon Institute suggests that the average total cost of a data breach was USD 4 million in 2016 (an increase of 29% compared to 2013). According to the study, this would correspond to an average cost per lost record of USD 158. There are significant cross-country and sectoral variations though. The average cost per lost record was estimated to be as high as USD 221 in the United States and as low as USD 61 in India. Furthermore, the average cost per lost record tends to be the highest in specific sectors, such as healthcare and transportation.

The greatest cost component for organisations tends to be loss of business, or: “This confirms the impact of a data breach on consumer loyalty” (Internet Society, 2016). The second highest cost component is remediation. Based on anecdotal evidence, it appears that litigation is increasingly common in the case of data breaches, with card issuers seeking to recover the costs of reissuing payment cards from the hacked companies and affected individuals launching class-action lawsuits. Breached organisations can end up paying fines, legal fees and redress costs. ChoicePoint, for example, paid more than USD26 million in fees and fines as a result of the action by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC, 2006). In 2008, a data breach at one of the largest US credit card processing companies in the United States, Heartland Payment Systems, affected more than 600 financial institutions for a total cost of more than USD 12 million in fines and fees (McGlasson, 2009). In 2015, AT&T agreed to pay USD 25 million to settle an FTC investigation relating to data breaches involving almost 280 000 US customers (FTC, 2016).

Big data analytics presents new privacy risks to individuals’ privacy

Advances in data analytics now make it possible to infer sensitive information from data which may appear trivial at first, such as past individual purchasing behaviour or electricity consumption. This increased capacity of data analytics is illustrated by Duhigg (2012) and Hill (2012), who describe how the US-based retailing company Target “figured out a teen girl was pregnant before her father did” based on specific signals in historical buying data.24 The misuse of these insights can implicate the core values and principles which privacy protection seeks to promote, such as individual autonomy, equality and free speech, and this may have a broader impact on society as a whole.

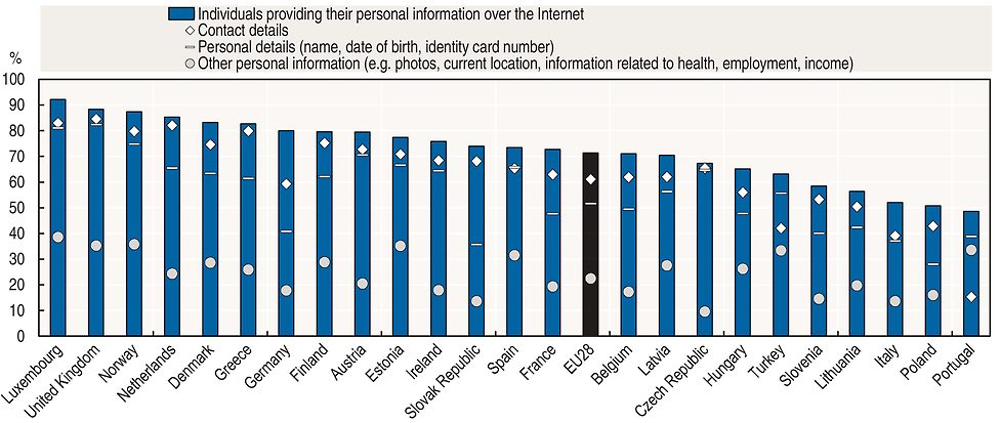

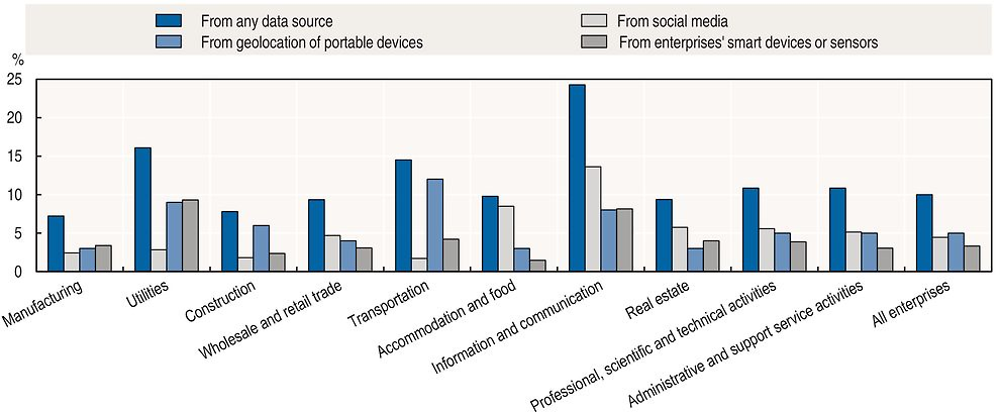

In some cases, personal data are provided or revealed: 1) by choice, for example, through social media and e-mail; in other situations, through compulsory disclosure, for example as a pre-condition to receiving services; or 2) without awareness or consent, for example through tracking an individual’s browsing. In the European Union, more than 60% of all individuals have provided their personal data over the Internet (Figure 6.10). Most of them provide personal details (name, date of birth, identity card number) as well as contact details. But around a third of these individuals have provided other personal information such as photos, location data, and information about their health and income over the Internet. Other personal data are collected by sensors in smartphones, tablets, laptops, wearable technologies and even sensor-enabled clothing, automobiles, homes and offices. Moreover, increasingly, new data are derived or inferred based on correlations gleaned from existing data (Abrams, 2014). The type of personal data that is collected and the means used to collect such data may vary by sector (Figure 6.11). Utilities, for example, are more likely to collect big data from sensors and to use geolocation data from mobile devices. Mobile devices are also used in the transportation sector. Social media data, in contrast, are used to a large extent in accommodation and food, mainly for marketing purposes.

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

By collecting and analysing large amounts of consumer data, firms are able to predict aggregate trends, such as variations in consumer demand as well as individual preferences, thus minimising inventory risks and maximising returns on marketing investment. Furthermore, by observing individual behaviour, firms can learn how to improve their products and services, or redesign them in order to take advantage of the observed behaviour. These uses may also benefit the consumer: targeted advertising may give consumers useful information, since the adverts are tailored to consumers’ interests (Acquisti, 2010). However, this ability to profile and send targeted messages and marketing offers to individuals may also have adverse consequences: some consumers may object to having their online activities observed; they may end up paying higher prices as a result of price discrimination; or they could be manipulated towards products or services they may not even need (OECD, 2015b).

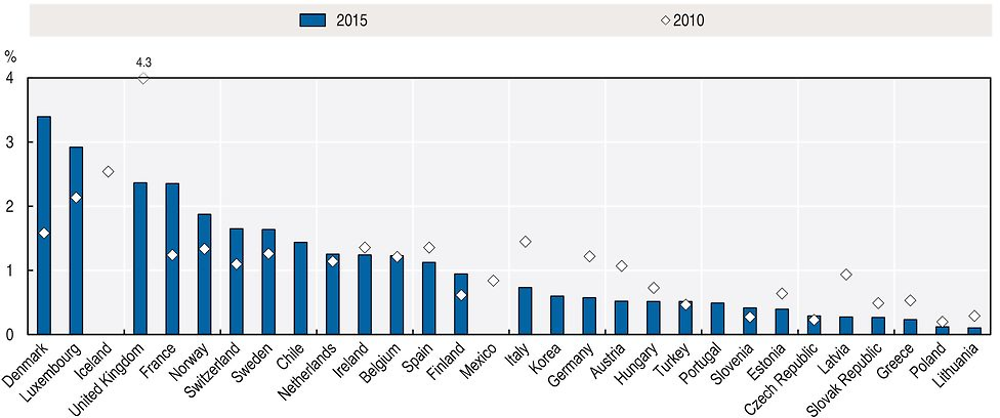

The risk of online fraud is growing with the importance of e-commerce

The numbers and types of reported online fraud have increased in many countries. In countries such as Denmark, France, Luxembourg, Norway and Sweden, for example, around 2% of all individuals experienced a financial loss from fraudulent payment online in the final three months of 2015, and this share had increased compared to 2010 in many countries (Figure 6.12). In the United States alone, over 3 million complaints (excluding do-not-call) were registered in the Consumer Sentinel Network (CSN) database in 2016. “Impostor scams” (13%), “identity theft” (13%), and “telephone and mobile services” (10%) were among the most frequent complaint subcategories related to Internet usage and are growing in significance.25 That said, the rise of reported complaints is only partly attributable to Internet-based transactions, it could also be the result of (non-Voice over Internet Protocol [VoIP]) telephone-based incidents. It therefore needs to be assessed further through additional data. Notably, complaints in the CSN are self-reported and unverified, and do not necessarily represent a random sample of consumer injury for any particular market. The following sections present current trends related to identity theft and fraudulent and deceptive commercial practices.

Notes: Data for Chile and Switzerland refer to 2014 instead of 2015. Data for Mexico refer to 2009 instead of 2010.

Source: OECD, ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals (database), http://oe.cd/hhind (accessed June 2017).

As highlighted above, personal data breaches not only cause significant economic losses to the business affected, but can also cause harm as a result of the privacy violation of the individuals whose personal data have been breached. In addition, further consumer detriment may result from a data breach such as harm caused by identity theft. Available evidence suggests that identity theft incidents, in particular through phishing or pharming, have increased in recent years. Of the over 3 million complaints received by the CSN in the United States in 2016, for example, more than 13% were related to identity theft. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of complaints related to identity theft increased on average by more than 30% annually, with the number of complaints reaching its peak in 2015 (with more than 490 000 complaints).26 Not all complaints were related to online activities though: “Employment – or tax-related fraud (34%) was the most common form of reported identity theft, followed by credit card fraud (33%), phone or utilities fraud (13%), and bank fraud (12%)” (FTC, 2017). In 2015 there was also a huge increase in the share of individuals experiencing a financial loss from phishing or pharming in many OECD countries, most notably in Belgium, Luxembourg, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and France (Figure 6.13). The share of individuals experiencing a financial loss from phishing or pharming only diminished significantly in a few countries, such as in Austria, Italy, Ireland and Latvia. The extent to which public policies could have been determinant for the decrease in incidents deserves further examination.

Note: Data for Switzerland refer to 2014 instead of 2015.

Source: OECD, ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals (database), http://oe.cd/hhind (accessed June 2017).

Fraudulent and deceptive commercial practices can also cause actual harm to consumers and reduce trust in e-commerce.27 According to data from econsumer.gov, an ICPEN initiative of 36 countries that allows consumers to file cross-border complaints, the top three complaint categories for 2016 were: 1) “shop at home/catalogue sales”; 2) “impostor: government”; and 3) “travel/vacations”. Similarly, available evidence for the European Union shows that consumers are increasingly facing issues related to such fraudulent and deceptive practices. The main problems encountered when buying online in the EU27 besides technical issues, were related to speed of delivery being longer than indicated. This was experienced by around 20% of all EU consumers buying online in 2016 (compared to 5% in 2009). Delivery of the wrong or damaged product, experienced by around 10% of all EU consumers in 2016 (compared to around 4% in 2009), is another major issue. The other issues, each affecting between 3% and 6% of all EU consumers, include problems with fraud, difficulties finding information concerning guarantees and other legal rights, final prices being higher from the ones initially indicated, unsatisfactory handling of complaints and redress. All of these issues have significantly increased compared to 2009.

Building and reinforcing trust in the digital economy

While trust can erode over time if overexploited, it can also be built and reinforced. And individuals (including consumers) and businesses have different means at their disposal to enhance trust. For example, consumers can benefit from truthful and transparent online reviews, endorsements and product comparison tools to overcome the information asymmetry between consumers and businesses (OECD, 2016e). Furthermore, risk management practices, and in particular the risk assessment process, provide organisations with the information needed to determine whether the level of risk in their environment is acceptable for undertaking investments in, and using, a digital technology. Finally, there are trust-enhancing technologies, including, but not limited to, privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) and digital security tools. More recently block chains have been discussed as an emerging technology for users to enhance trust in transactions without the need for a trusted third party (Chapter 7). These trust-enhancing means are discussed further below. This section does not discuss the role of public policies in enhancing trust, which is discussed in Chapter 2.

Empowering individuals and businesses remains necessary to better address trust issues

Being well informed and aware about digital security and privacy risks is a basic condition for being able to address major trust issues in the digital economy. According to the Special Eurobarometer survey (EC, 2015c), “respondents who feel well informed about the risks of cybercrime are more likely to use the Internet for all of the various activities, compared with those who do not feel well informed”. These individuals are also more likely to take measures to address these risks. For example, 32% of well-informed respondents regularly change their passwords, compared with 19% of respondents who do not feel well informed. Individuals in Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden are more likely to be well informed about the risks of “cybercrime” and they are also less likely to be concerned about being the victim of such crime. In countries such as Greece, Hungary, Italy and Portugal the opposite is true; individuals in these countries are less likely to feel well informed about the risks of cybercrime and are less likely to use digital services such as online banking and e-commerce. This suggests that there may be a negative correlation between being informed about digital security and privacy risk, and being concerned about being a victim of digital security and privacy incidents. It also underlines the importance of awareness, skills and empowerment as reflected, for instance, in the OECD Council Recommendation Digital Security Risk Management for Economic and Social Prosperity (OECD, 2015a).28

In the area of privacy, the importance of awareness, skills and empowerment has also long been recognised (OECD, 2015b). In particular, means to provide individuals with better mechanisms to control their personal data have been discussed, such as data portability (see Chapter 2). As shown in Figure 6.14, for instance, 60% of individuals in the European Union are already managing access to their personal data. They do so either by: 1) limiting the use of their personal data for advertising purposes (40% of all individuals); 2) limiting access to their social networking profiles (35%); 3) restricting access to their geographic location (30%); and 4) asking websites to update or delete information held about them. It is interesting to note that individuals in countries such as Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, where being well informed about the risks of “cybercrime” is more likely, also tend to be more likely to manage their personal information over the Internet. In contrast, individuals in countries where individuals feel less well informed about the risks of “cybercrime” also rank below average in terms of the share of individuals managing the use of their personal information over the Internet. The following sections discuss trends on the means to empower individuals and businesses, including through the use of trust-enhancing technologies, the reduction of information asymmetries, and developing skills and competencies related to digital security and privacy (risk management).

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed March 2017).

Trust-enhancing technologies are needed but not sufficient for empowering individuals and businesses

There is strong evidence for the increasing use of trust-enhancing technologies. There are, however, also significant variations by country, firm size and industry. According to the 2016 Ponemon State of Cybersecurity in Small and Medium-Sized Businesses anti-malware, client firewalls and password protection/management rank among the highest security tools used. In Korea, the 2015 Survey on Information Security in Business revealed that by far the largest proportion of respondents invested in or planned on investing in wireless local area network (LAN) security.

As products (goods and services) and business processes become more data-intensive, and data proliferates to more and more locations, such as mobile devices and the cloud, encryption is increasingly seen as a needed supplement to existing infrastructure-centric protection measures. According to a 2016 Encryption Application Trends Study sponsored by Thales e-Security and covering over 5000 respondents in 14 major industry sectors and 11 countries, encryption has never been as profoundly used in the 11-year history of the survey after accelerating in 2014. More companies are also embracing an enterprise-wide encryption strategy. In 2015, 41% of surveyed businesses indicated having extensively deployed encryption compared to 34% in 2014 and 16% in 2005 (Figure 6.15). Germany, the United States, Japan and the United Kingdom rank above average in terms of the share of businesses having deployed or deploying an enterprise-wide encryption strategy (with 61%, 45%, 40% and 38% respectively). Surveyed businesses indicate privacy compliance regulation,29 digital security threats targeting in particular intellectual property, as well as employee and customer data as the main reason for this fast increase in encryption adoption in recent years. In particular, firms in heavily regulated industries dealing extensively with (big) data rank high among the list of extensive encryption users. These include most notably: financial services, healthcare and pharmaceuticals, and technology and software firms.

Note: Based on over 5 000 respondents from 14 industry sectors and 11 countries across the globe.

Source: Thales e-Security (2016), 2016 Encryption Application Trends Study.

Internet communications (e.g. Transport Layer Security [TLS] or its predecessor Secure Socket Layer [SSL]) still rank the highest among the application for encryption use across industries, before databases and mobile devices. SSL is a security protocol used by Internet browsers and web servers to exchange sensitive information such as passwords and credit card numbers. It relies on a certificate authority, such as those provided by companies like Symantec and GoDaddy, that issues a digital certificate containing a public key and information about its owner, and confirms that a given public key belongs to a specific site. In doing so, certificate authorities act as trusted third parties. In the past, there has, however, been a series of security incidents targeting certificate authorities (see for example the 2001 security incident affecting DigiNotar, a company based in the Netherlands).

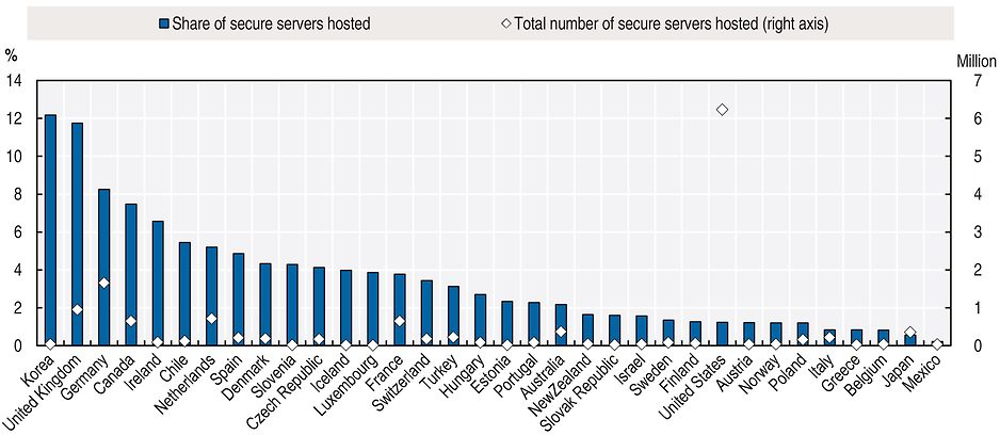

Netcraft carries out monthly secure server surveys on public secure websites (excluding secure mail servers, intranet and non-public extranet sites). According to the March 2017 survey, more than 27 million secure servers were deployed worldwide. This corresponds to a compound average growth rate of 65% annually (compared to 2.2 million in 2012). Growth rates accelerated in 2014. Prior to that the number of servers grew by around 20% year-on-year.30 The number of secure servers hosted in the OECD area was slightly above 14 million in March 2017, accounting for 83% of the total number of secure servers hosted worldwide.31 The United States accounted for the largest share of secure servers (6.2 million), at 38% of the world total. It was followed by Germany (1.7 million) and the United Kingdom (953 000) (Figure 6.16). Relative to the total number of sites hosted, however, most countries still perform poorly in terms of the share of secure servers over their total number of servers hosted. In the United States, for example, less than 1% of all servers hosted use SSL/TLS.32

Source: Netcraft, www.netcraft.com, (accessed April 2017).

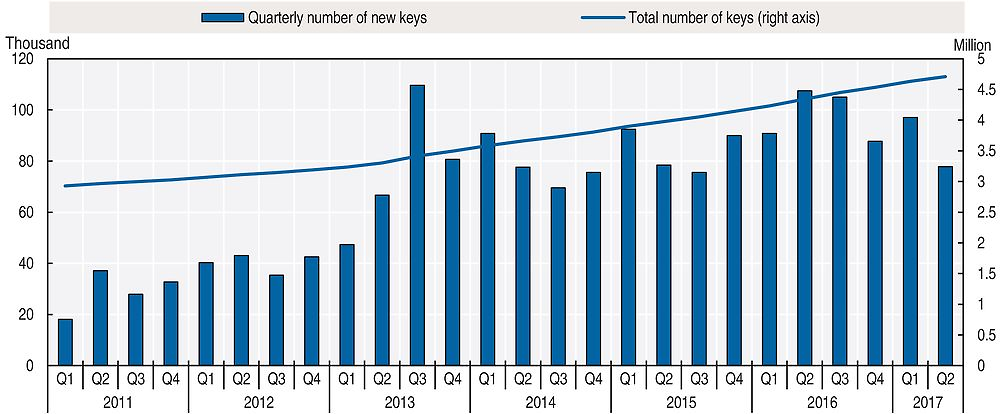

The use of encryption has also intensified in the market for consumer goods and services, where companies such as Apple and Google continue to increase their default use of encryption (OECD, 2015b). These firms’ latest mobile operating systems encrypt nearly all data at rest (in addition to data in transit) by default. Additionally, demand for end-to-end encryption has increased considerably in recent years with apps such as Signal Private Messenger and Threema being increasingly adopted and massively popular apps like WhatsApp also rolling out end-to-end encryption.33 Users’ increasing interest for encryption is also reflected in the adoption of PETs such as OpenPGP (Pretty Good Privacy), a data-encryption software used most commonly to secure e-mails. According to data collected by Fiskerstrand (2017), more than 1 100 new PGP keys are being added every day. The data show in particular that in the months following the Snowden disclosures (Q3 2013), PGP key creation reached the highest levels in the history of the software with almost 101 000 new PGP keys are being added in Q3 2017 (Figure 6.17). This correlation does not imply causation and would call for further analysis.

Source: Author’s calculations based on data collected by Kristian Fiskerstrand (sks-keyservers.net) (accessed June 2017).