Chapter 2. Governing school funding1

This chapter describes the different actors involved in raising, managing and allocating school funds across countries and analyses how the relationships between these actors are organised. It looks at both the sources of school funding (who raises funds for school education?) and the responsibilities for spending these funds (who manages and allocates funds for school education?). As OECD school systems have become more complex and characterised by multi-level governance, a growing set of actors including different levels of the school administration, schools themselves and private providers are increasingly involved in financial decision making. The chapter analyses the opportunities and challenges for effective school funding in such multi-level governance contexts and explores a range of policy options to reap the potential benefits of fiscal decentralisation, school autonomy over budgetary matters and involvement of private school providers in the use of public funds.

Public governance refers to the formal and informal arrangements that determine how public decisions are made and how public actions are carried out (OECD, 2011a). In the context of school funding, governance questions are ultimately concerned with who makes, implements and monitors the decisions about how funding is spent. Where the decision-making power on school funding is located is closely related to where such funding is raised, i.e. in school systems where a large part of school funding originates from the local government, the local level is likely to have a greater say in steering its schools and making funding allocation decisions. This chapter describes the different actors involved in raising, allocating and managing school funding and it analyses how the relationships between these actors are organised in different OECD and partner countries. Following this short introduction, it looks at i) the sources of school funding (who raises funds for school education?) and ii) the responsibilities for spending these funds (who manages and allocates funds for school education?).

Sources of school funding

This section provides an overview of the main actors involved in providing funds for school education. It finds that while the majority of school funding originates at the central government level, other actors also increasingly contribute to raising funds for school services. Sub-central governments typically complement central school funding from their own revenues while also acting as an intermediary distributing central government funding to schools. In addition, private spending on schools – which may originate from households, employers or communities – has increased considerably in recent years. Finally, international funding also provides an important complement to national sources of school funding in a range of countries.

The vast majority of school funding comes from public sources

In most OECD countries, governments provide by far the largest proportion of education investment. Governments subsidise education mostly through tax revenues (e.g. taxation upon earnings, property, retail sales, general consumption) collected at the different administration levels. On average across the OECD, almost 91% of the funds for schooling come from public sources (OECD, 2016a). Chile is the only OECD country where the share of public funds in overall expenditure on schooling was below 80% in 2013 (OECD, 2016a). In providing public funding for schooling, governments guarantee universal access to basic education by ensuring free provision or reducing the financial contributions of parents to a minimum.

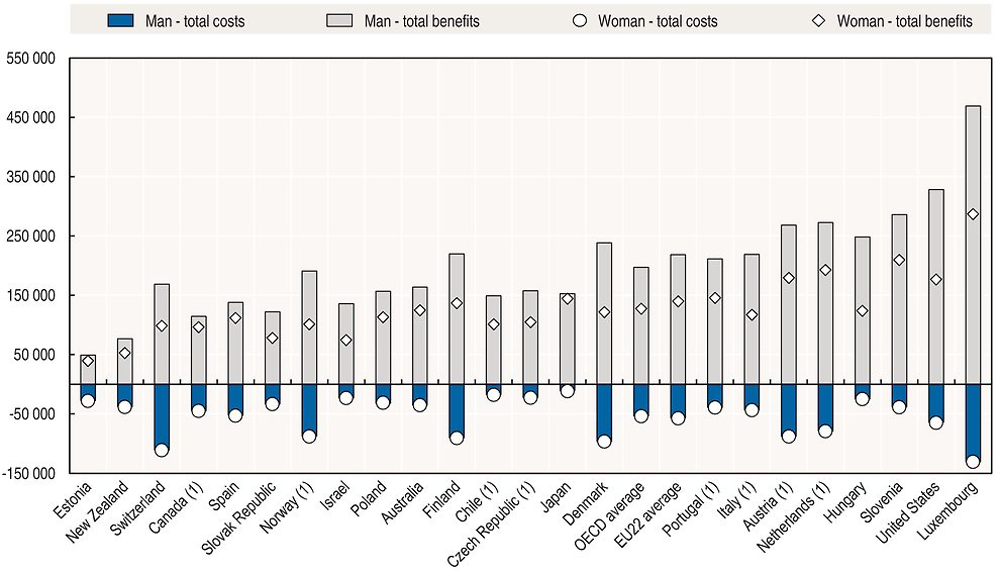

Investing in an accessible, high-quality education system is a crucial means to provide people with the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in the labour market and to foster individual wellbeing as well as social cohesion and mobility. There is also a clear economic rationale for the public funding of education. According to OECD analyses, the benefits of educational investments not only accrue to the individuals receiving it, but also to society at large, providing strong economic incentives for governments to engage in the public funding of education. More highly educated individuals require less public expenditure on social welfare programmes and generate higher public revenues through the taxes paid once they enter the labour market. Figure 2.1 shows the public costs and benefits associated with an average person attaining tertiary education across OECD countries (OECD, 2016a).

1. Year of reference differs from 2012, Please see OECD (2016a), Tables A7.4a and A7.4b for further details.

Countries are ranked in ascending order of net financial public returns for a man.

Source: OECD (2016a), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en, Tables A7.4a and A7.4b; see Annex 3 for notes (www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance-19991487.htm).

Most systems rely on a mix of central and sub-central funding for schools

The governance of school funding varies between countries, with a few countries such as New Zealand (100%), the Netherlands (89%), Hungary (88%) and Slovenia (88%) funding schools mostly from central budgets, while most expect sub-central governments to contribute significantly to raising funds for school education. On average across the OECD, 55% of initial public funds for schooling originate at the central government level, while regional and local governments contribute about 22% of initial funds each (OECD, 2016a). Across the OECD review countries, the responsibilities for raising funds for schooling are typically distributed between two or three levels of governance, with the exceptions of Belgium (where four levels of governance are involved) and Uruguay (where the central level is the only source of school funding) (Table 2.A1.1).

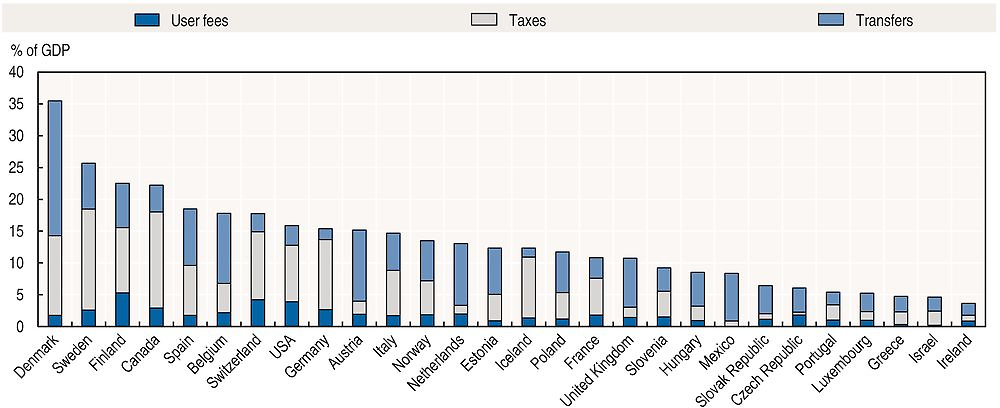

Regarding the composition of final funds allocated to schools, central government funding of public services depends mainly on taxes, while the sub-central revenue mix includes both taxes (whether own taxes or those shared with other tiers of government) and transfers from higher levels of government. Sub-central governments may also rely on user fees, although these typically represent a small proportion of their revenue. Figure 2.2 shows the composition of sub-central government revenues across OECD countries. On average across the OECD, almost equal parts of overall sub-central government revenue came from taxes (42%) and from transfers (44%) in 2013. Fourteen percent came from user fees (OECD/KIPF, 2016).

Source: OECD/KIPF (2016): Fiscal Federalism 2016: Making Decentralisation Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264254053-en.

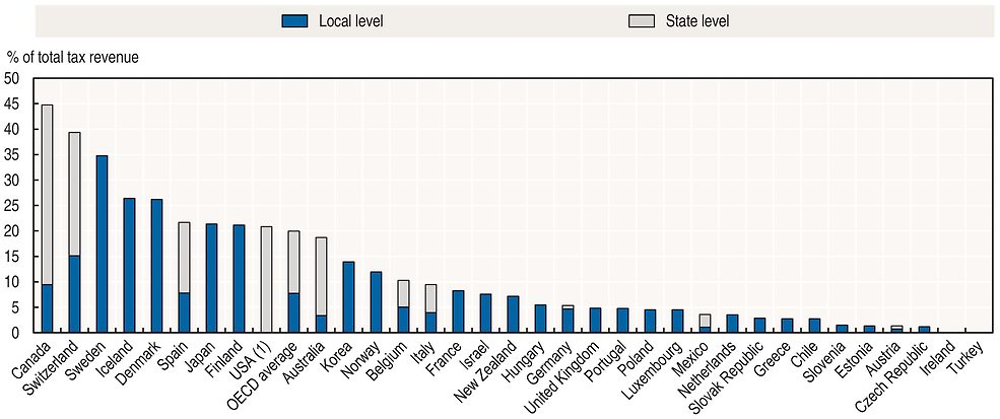

Across OECD countries, sub-central entities have varying degrees of autonomy over their own tax collection, such as the right to introduce or abolish taxes, set tax rates, define the tax base and grant allowances or relief to individuals and firms. Often the collection of particular taxes is not assigned to one specific level of the administration but it is shared between different levels of government. In such cases, sub-central authorities often collectively negotiate the tax sharing formulas with the central government (OECD/KIPF, 2016). As can be seen in Figure 2.3, in several countries sub-central authorities have considerable taxing powers.

1. Tax autonomy of local governments in the United States varies across the states and is not assessed.

Source: OECD/KIPF (2016): Fiscal Federalism 2016: Making Decentralisation Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264254053-en.

According to the OECD/KIPF (2016), a higher sub-central tax share is desirable for several reasons related to efficiency and accountability: reliance on own tax revenue brings jurisdictions autonomy in determining public service levels in line with local preferences; it makes sub-central governments accountable to their citizens who will be able to influence spending decisions through local elections; it may enhance overall resource mobilisation in a country as local/regional authorities may tap additional local resources; and it creates a hard budget constraint on sub-central entities which is likely to discourage overspending.

At the same time, strong reliance on sub-central tax shares may raise equity concerns. Where sub-central authorities generate their own revenue, wealthier jurisdictions will be in a better position to provide adequate funding per student in their local systems than others. In the United States, for example, prior to the 1970s the vast majority of resources spent on compulsory schooling was raised at the local level, primarily through local property taxes. Because the local property tax base is generally higher in areas with higher home values, the heavy reliance on local financing contributed to the ability of wealthier to spend more per student (Kirabo Jackson et al., 2014).

In countries where school funding is heavily dependent on local tax bases, this may have adverse effects on matching resources to student needs, as areas with more disadvantaged students are likely to have fewer resources available to meet student needs. In such contexts, fiscal transfers or grants have an important role to play in equalising revenue levels across sub-central jurisdictions (more on this below).

Private funding plays an increasingly important role in the school sector

While the vast majority of school funding is provided from public sources, private sources of school funding have grown more quickly in recent years than public sources. Between 2008 and 2013, private sources increased by 16% on average across the OECD, while public sources increased by only 6%. Private sources typically play a more important role in secondary than in primary education. At the upper secondary level, there is a slightly stronger presence of private sources of funding in the vocational education and training (VET) sector than in the general sector (OECD, 2016a).

Schools may raise their own revenues through sales of services, rental of facilities and parental fees

While public schools are financed mainly through funding allocations coming from the different levels of the educational administration, individual schools may also have the ability to raise their own revenues from private (and/or public) sources. This typically involves the sale of services (particularly in the vocational sector), the rental of facilities and funds raised from parents and/or the community through obligatory fees or voluntary donations.

Among the OECD review countries, parental contributions are not uncommon in public pre-primary education with 9 of 17 systems charging tuition fees for pre-primary education that tended to be determined by either local or central authorities. While mandatory tuition fees are typically prohibited in public primary and secondary schools (Table 2.A1.2), the majority of education systems with available data permit public schools to benefit from voluntary monetary and non-monetary parental contributions as well as donations (Table 2.A1.3).

Most countries also permit public schools to raise additional revenue by renting out their materials and facilities (e.g. sports facilities), by providing extracurricular activities for a fee or – particularly in the vocational sector – by selling non-teaching services (e.g. catering, hairdressing). In Estonia, for example, public vocational schools are largely funded by the state but permitted to supplement their resources through the sale of goods and services (Santiago et al., 2016b). The sale of teaching services, on the other hand, is significantly more restricted among the OECD review countries (Table 2.A1.3).

Employer contributions are significant in some countries’ vocational education and training (VET) sectors

Across the OECD, the average annual expenditure per upper secondary VET student in 2013 was 10% higher than that for students in general education (OECD, 2016a). There are often higher costs for the specialised equipment required to teach many technical and practical subjects. Unlike general education programmes, the funding of the VET sector in many countries involves contributions from employers. Given the larger set of actors engaged in the funding of VET, it is frequently based on agreements between public and private stakeholders determining their respective contributions to VET funding as well as their role in the provision of services like work-based learning and school-based learning. Employers tend to contribute to VET in the form of financial transfers (directly to VET providers or indirectly via training levies)2 as well as through the provision of equipment, staff and training places. Given the direct benefits that students’ acquisition of occupation-specific skills brings to the industry, employers sometimes bear the cost of work-based learning and contribute to covering costs for materials, trainers or the remuneration of trainees (for more information on the costs and benefits of apprenticeships see Kuczera, 2017). The school-based component of VET is more commonly publicly funded (Papalia, forthcoming).3

However, cost-sharing arrangements with significant private contributions are relatively rare in upper secondary VET programmes (see Figure 2.4). Private sector contributions tend to be significant in countries with a large apprenticeship system in which employers cover most of the costs of work placements (e.g. apprentice pay, instruction costs, tools and equipment). Among the 19 OECD and partner countries with available data for 2012, funding from private sources other than households typically accounted for less than 10% of total expenditure, with the notable exceptions of Germany and the Netherlands. The German VET system, as described in Box 2.1, provides an example of cost sharing arrangements involving contributions from all of the system’s major stakeholders. In several countries, however, students have very few opportunities to engage in work-based learning or apprenticeships and there is no legal requirement for firms or industries to make financial contributions to the state-run vocational system (Santiago et al., 2016b).

Note: Expenditure that is not directly related to education (e.g. for culture, sports, youth activities, etc.) is not included unless it is for the provision of ancillary services. Private expenditure includes contributions from households (students and their families) and other private entities such as firms.

Source: OECD (2016a), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en.

The German dual VET system is characterised by high levels of per student expenditure, a strong enrolment in apprenticeship schemes and a high level of involvement among employers, with more than 60% of firms taking part in the provision of initial vocational education and training. The funding of VET involves all stakeholders. Public resources are provided by federal ministries (Ministry of Education and Research, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy, and the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs), central agencies, such as the federal employment agency, as well as the federal states (Länder). Private sector resources are contributed by companies, unions, chambers as well as students and their families.

The school-based learning component is provided by vocational schools and funded primarily out of the federal states’ budgets. The states are responsible for funding teaching staff and cover, on average, 80% of the vocational schools’ expenses. Municipalities are the second main contributor, covering the largest share of material costs and investments out of their own revenue. The work-based learning provided through the apprenticeship system is largely self-financing and public authorities only indirectly contribute to its funding by providing students and employers with financial incentives to engage in training activities. German employers are required to contribute to the funding of work-based learning for their apprentices on the basis of collective agreements. The resources made available by employers include the apprentices’ wages as well as the material and human resources necessary to provide adequate training conditions. With the exception of the construction sector, employers do not contribute to training levies.

Source: Papalia, A. (forthcoming), “The Funding of Vocational Education and Training: A Literature Review”, OECD Education Working Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Ensuring adequate involvement of companies in both the provision and funding of initial VET is a challenge shared by several OECD review countries. Evidence from across OECD countries indicates that labour market outcomes of vocational graduates improve if their programmes include substantial work-based learning, such as apprenticeships offered by companies (OECD, 2014a). In countries where practical training is primarily provided by schools, a number of efficiency challenges may arise. For schools, continuously updating their practical training offer to ensure its relevance to the requirements of the labour market involves significant investments into training, equipment and physical infrastructure, which may discourage innovation and experimentation. The failure to provide opportunities for work-based skills development can thereby reduce the efficiency of VET provision and diminish its labour market relevance (Shewbridge et al., 2016b).

Countries such as Switzerland, Germany and Denmark operate so called dual systems whose VET pathways combine periods of school-based learning with alternating periods of work-based training which companies support through the contribution of financial and human resources. Regardless of whether employers are directly involved in the provision of VET, training levies are the most common mechanism to collect earmarked VET resources from the private sector. While some levies primarily serve to raise revenue for the provision of VET, for example through a tax paid by every employer, other levy schemes provide employers with incentives to actively engage in work-based training. These types of training levies are typically linked to a disbursement or exemption mechanism that redistributes the funds raised by the levy to employers that engage in the training of apprentices (Dar et al., 2003).

International funding may complement national sources of school funding

Funding from international sources including the European Commission and international agencies like the World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank represents a significant share of investment to schooling in some countries. Several OECD review countries have significantly benefited from international funding to support educational initiatives and infrastructural investments (Box 2.2). The European Union’s two structural funds – the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the European Social Fund (ESF) – are designed to promote economic and social development and address specific needs of disadvantaged regions across the European Union. EU funds are allocated subject to the European Commission’s approval of the recipient states’ operational programme, in which they outline the funding’s strategic objectives and propose an auditing framework. The managing authorities at the national level are then responsible for administering the funds and allocating them to projects and sub-central beneficiaries. Member states are also required to co-finance their operational programmes to varying extent.

In several OECD review countries, European Structural Funds have played an important role in the implementation of reforms and developments of the educational infrastructure. These included significant capital investments to upgrade existing facilities, widen access to high-quality early education and care and support the rationalisation of the school network. The Lithuanian Ministry of Education, for example, allocated EU funding to expand school transportation services and assist the creation of multi-function centres that combine day care, pre-primary and primary education as well as a community facility under a single management structure in rural areas (Shewbridge et al., 2016a). EU structural funds were also used to improve the provision of vocational education and training and fund the creation of vocational training centres in countries like Lithuania and the Slovak Republic. In Estonia, funding from the ESF was used to support the developments of the VET curriculum, while the ERDF funded corresponding infrastructural improvements (Santiago et al., 2016a). Another area supported by EU investments is teacher professional development, for example through Estonia’s ESF-co-financed science teacher training programme and the initiative “Raising the qualification of teachers in general education from 2008 to 2014” (Santiago et al., 2016a). Other EU-funded projects have also focused on quality assurance and supporting schools’ use of self-assessment tools as well as promoting equity through the integration of Roma communities in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic.

Funding from international agencies such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) or the World Bank has also been used to finance educational projects, often focused on capital expenditure and the improvement of infrastructures to support the expansion of educational services. In Uruguay, for example, loans from the World Bank were used to finance the Support Programme for Public Primary Education (Programa de Apoyo a la Enseñanza Primaria Pública, PAEPU), which provides investments into the infrastructure and equipment of full-time schools. The project is implemented in co-ordination with the Pre‐school and Primary Education Council (Consejo de Educación Inicial Primaria, CEIP) and the Central Directive Council on Education (Consejo Directivo Central, CODICEN) of the National Administration for Public Education (Administración Nacional de Educación Pública, ANEP). Uruguay also co-operates with the IDB, whose loans have funded the country’s Support Programme for Secondary Education and Training in Education (Programa de Apoyo a la Educación Media y Formación en Educación, PAEMFE), which funds strategic investments into the infrastructure and equipment of secondary education and teacher training institutions (Santiago et al., 2016b; INEEd, 2015).

Source: Shewbridge, C. et al. (2016a), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Lithuania 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252547-en; Santiago, P. et al. (2016a), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Estonia 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264251731-en; Santiago, P. et al. (2016b), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Uruguay 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265530-en; INEEd (2015), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Uruguay, www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

Making the most effective use of international funding requires effective procedures to evaluate the investments’ impact, ensure their long-term sustainability and align them with strategic educational objectives (see also Chapters 4and 5). In addition, a common challenge for countries benefiting from international funding is the need to develop adequate capacity to absorb and successfully use such funding for the implementation of agreed programmes at the local level. Particularly where individual schools need to apply for receiving project resources from international donors or the EU, limited management and implementation capacity and/or lack of experience in writing grant applications may prevent them from seizing the opportunities that such international funds provide. In some OECD review countries, such as the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, this has resulted in low absorption rates and underutilisation of internationally funded operational programmes (Shewbridge, 2016b; Santiago, 2016c). Variation across different schools’ capability to attract funds can also exacerbate existing patterns of inequality, since large or urban schools may be better placed to make a successful bid for grants.

Responsibilities for school spending

This section looks at the different actors involved in making decisions on school spending. It discusses how common governance trends including fiscal decentralisation, school autonomy over budgetary matters and public funding of private schools have led to the emergence of a broad range of actors involved in the allocation, management and use of school funding in a number of countries. The section looks at each of these phenomena in turn. First, it analyses the degree of decentralised decision making on school funding across countries and explores opportunities and challenges related to the involvement of sub-central governments in making school funding decisions. Second, it describes the level of schools’ budgetary autonomy across countries and the necessary conditions for more autonomous schools to be able to contribute to effective and equitable use of school funding. Third, it takes stock of countries’ approaches to publicly funding private providers and reviews the potential benefits and risks of such approaches within overall school funding strategies.

Sub-central governments are the most important spenders in school education

Over the past two decades, sub-central jurisdictions have acquired increasing powers in the distribution of funding to education across OECD countries, with almost 60% of final funds allocated to schools by sub-central governments. This share is even higher in countries such as the United States (100%), Japan (98%), Canada (97%) and Germany (94%) where the funds are almost entirely coming from the sub-central levels (OECD, 2016a). However, while sub-central authorities are the most important spenders on schooling in many countries, there are wide variations across countries in the degree to which they actually have decision-making power over the distribution of funding between the individual schools in their jurisdiction (for a detailed analysis, see Chapter 3). In analysing the decision-making powers of sub-central authorities, it is important to note that the involvement of sub-central governments varies depending on the type of investment (e.g. capital versus current expenditure) and the levels and sectors of schooling (e.g. primary versus secondary schooling) that are being considered (for more detail see Chapter 3).

Sub-central spending responsibilities have grown faster than revenue raising capacities

As explained in the previous section, sub-central jurisdictions have acquired increasing powers for the collection of their own revenue. But at the same time, sub-central spending responsibilities have also grown, and they have done so much faster than tax collection responsibilities. Figure 2.5 illustrates the relative shares of sub-central revenue and spending in total government revenue and spending. The gaps between the revenue and the expenditure of sub-central jurisdictions are referred to as “vertical fiscal imbalances”. Such imbalances are typically addressed through vertical fiscal transfers – or grants – from the central level to sub-central levels. They may also be addressed through horizontal transfers between sub-central entities. Fiscal transfers aim to offset gaps between revenue and expenditure, equalise fiscal disparities across regions and ensure similar ability to provide public services across all sub-central governments. Fiscal transfers represent an important share of overall central government spending and they have grown in recent years, from 6% to 7% of GDP between 2000 and 2010 (OECD/KIPF, 2016).

Note: Sub-national expenditures include intergovernmental grants, while sub-national revenues do not. Latest available data for Korea are from 2012 and for Mexico from 2013.

Source: OECD/KIPF (2016): Fiscal Federalism 2016: Making Decentralisation Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264254053-en.

Fiscal transfers can also serve central governments in steering sub-central levels of the administration towards spending on certain purposes. Where central government grants are earmarked for a particular purpose, they allow the central level to exert considerable control over sub-central educational policy and spending (see Chapter 3 for more information on the design aspects of earmarked grants). OECD/KIPF (2016) report that across different public sectors, a slight trend from earmarked grants towards more non-earmarked grants could be observed in recent years. At the same time, they noted a parallel increase in regulatory frameworks and output control, which is another way for central governments to steer the use of resources at the sub-central level towards particular standards and expected performance levels (see Chapter 5 on the evaluation of school funding at sub-central levels).

Fiscal transfers can equalise sub-central revenue levels but have a number of drawbacks

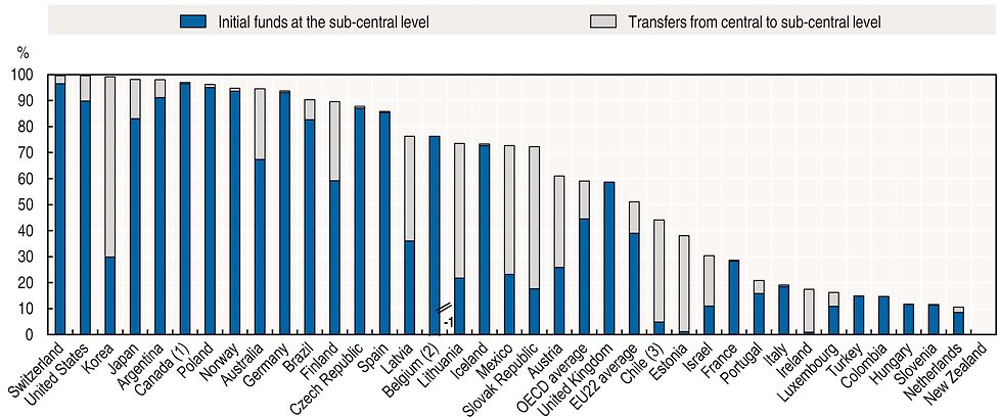

The extent of transfers of public funds from central to sub-central levels of government varies widely between countries. The length of the bars in Figure 2.6 indicates the share of sub-central (regional and local level) funding allocated to schools in each country. The different shadings indicate how this sub-central funding is composed of initial funds originating at the sub-central level (dark shading) and transfers from the central government (light shading). The difference of funding power before and after transfers from central to sub-central levels of government represents more than 30 percentage points in Austria, Chile, Estonia, Finland and Hungary, and more than 40 percentage points in Korea, Latvia, Mexico and the Slovak Republic (OECD, 2016a).

1. Year of reference: 2012

2. In Belgium, 76% of initial funds and 75% of final funds originate at the sub-central level

3. Year of reference: 2014

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of final funds allocated to schools by the sub-central level of government.

Source: OECD (2016a), Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2016-en, Table B4.3. See Annex 3 for notes (www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance-19991487.htm).

The operation of fiscal transfer systems can help provide sub-central governments with revenues to support similar levels of educational service provision at similar tax rates. Less advantaged sub-central authorities in terms of private income and with a challenging socio-economic composition of the population typically receive higher grants from the central government. Box 2.3 provides examples from different countries that introduced equalisation schemes alongside decentralisation reforms which shifted responsibilities for school funding to the local level.

When Brazil devolved authority from a highly centralised system to states and municipalities in the mid-1990s, it created a Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Schools and the Valorisation of the Teaching Profession (Fundo para Manutenção e Desenvolvimento do Ensino Fundamental e Valorização do Magistério, FUNDEF) to reduce the large national inequalities in per-student spending. State and municipal governments were required to transfer a proportion of their tax revenue to FUNDEF, which redistributed it to state and municipal governments that could not meet specified minimum levels of per-student expenditure. FUNDEF has not prevented wealthier regions from increasing their overall spending more rapidly than poorer regions, but it has played a highly redistributive role and increased both the absolute level of spending and the predictability of transfers. There is evidence that FUNDEF has been instrumental in reducing class size, improving the supply and quality of teachers, and expanding enrolment. At the municipal level, data show that the 20% of municipalities receiving the most funds from FUNDEF were able to double per-student expenditure between 1996 and 2002 in real terms.

When Iceland moved responsibility for compulsory education to the municipalities in 1995, the cost of compulsory schooling was determined to be 2.84% of the total income tax received by the state. That percentage was decided by using the capital city, Reykjavík, as a zero point – calculating by how many percentage points the local income tax would have to go up for the city to cover the cost of operating the compulsory schools, which came to 2.07% of the states total income tax. In 1995, 2.07% of the national annual income tax was therefore permanently transferred to the local income tax which is collected centrally and transferred to the municipalities in order to even out salary costs in the compulsory schools and to cover other costs related to the transfer of responsibilities for schooling from the central to the local level. Following the calculations for the City of Reykjavík, the total cost of operating all the compulsory schools in the country was then determined, which came to a total of 2.84% of the national income tax. The difference between the 2.84% and 2.07% – or 0.77% – was then allocated by the central government to The Local Governments’ Equalizations Fund. The role of the fund is to even out the difference in expenditure and income of those local communities with a specific or a greater need, through allocations from the fund, based on the relevant legislation, regulation and internal procedures established for the operation of the fund. A part of the 0.77% is earmarked to cover proportionally the operational cost of the fund itself but the main part is reallocated to the local communities. 71% of this amount goes towards general support but the rest is earmarked for specific purposes.

In Poland, education decentralisation was part of the overall decentralisation process of the country initiated in 1990. The main transfer from the central to local budgets is called “general subvention” and is composed of a few separately calculated components. Two main ones are the education component and the equalisation component. The education component is calculated on the basis of student numbers (with numerous coefficients reflecting different costs of providing education to different groups of students), and thus reflects different costs of service provision. The equalisation component is based on a formula and equalises poorer jurisdictions up to 90% of average per capita revenues of similar local governments. It thus reflects revenue equalisation.

Source: OECD/The World Bank (2015), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Kazakhstan 2015, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264245891-en; Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (2014), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Iceland, www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

While fiscal transfers play an important role in providing sub-central revenue for service provision and equalising sub-central revenue levels, OECD/KIPF (2016) outline a number of disadvantages of strong reliance on inter-jurisdictional grants and equalisation transfers. First, while one might expect that grants help to stabilise sub-central revenue, empirical evidence indicates that the opposite is often the case. Indeed, central government grants may exacerbate fluctuations in the revenue of sub-central government tiers because such transfers are often pro-cyclical, i.e. in times of strong growth, they are likely to increase whereas the amount of central transfers often decreases in times of crisis. This can reinforce pre-existing resource challenges at sub-central levels of administration and make it difficult for them to engage in medium-term planning (Chapter 4).

Second, grants may reduce the sub-central tax effort. For example, if grants are adjusted on the basis of local revenue, sub-central authorities might be discouraged from raising their own tax revenue because otherwise they might see their central grants reduced. In Estonia, for example, local governments have very limited revenue raising powers. The OECD review of Estonia found that this appears to encourage both local officials and their citizens to see any local financial difficulties as the result of insufficient national government support. The resulting “fiscal illusion” may reduce the willingness of both local officials and citizens to use local taxes to improve local services (Santiago et al., 2016a). Disagreement about the adequacy of central resources to fulfil decentralised responsibilities sometimes decreases the level of effective accountability of sub-central governments (Sevilla, 2006; see also Chapter 5). This is related to the difficulties that school systems face in objectively assessing the adequacy of funding (see Chapter 3).

Third, research and experience from different countries indicates that a high reliance on central grants may encourage overspending and thereby increase deficits and debt. There is evidence that a central government’s commitment to a certain grant level is not always credible and that sub-central authorities may overspend in the hope that this overspending will then be compensated via additional grants (OECD/KIPF, 2016). Busemeyer (2008) finds that giving sub-central levels of government the power to spend without forcing them to raise their own revenues (by granting them autonomy in setting tax rates) sets strong incentives for overspending. A large misalignment between financing and spending responsibilities may lead to mistrust, lack of transparency and inefficiencies, as one actor – the central government – is responsible for most of the financing, whereas other actors – sub-central governments – are in charge of expenditures. This often creates worries at the central level about the misuse and waste of resources while sub-central authorities may see overspending as evidence that the grant level is insufficient or the transfer system unfair.

In Austria, for example, the vast majority of tax revenue is generated at the federal level (87% in 2014) rather than by the provinces and municipalities who are responsible for funding provincial schools. Through the Fiscal Adjustment Act, central funds are then partially redistributed among the provinces and municipalities based on quotas which are renegotiated among the different tiers of government every four years. This system creates a split of financing and spending responsibilities, typical for Austrian federalism (which is sometimes described as “distributional federalism”). While the federal government and the provinces agree on annual staff plans, the provinces are free to hire more teachers than foreseen in these staff plans and the additional expenditures are partly covered by the federal level. This system tends to encourage overspending on teaching staff by the provinces compared to agreed staff plan. Between 2006 and 2010, the number of teaching positions at general compulsory schools that were not included in the initial budget almost doubled from 1 039 to 2 063, leading to considerable additional costs (Nusche et al., 2016a).

Finally, the determination of grant levels and calculation methods themselves may also be problematic. In Kazakhstan, for example, the OECD review team found that one of the main concerns related to school funding was the importance of negotiations for the calculation of central transfers and the definition of education budgets at the sub-central level. The budget negotiations were found to lead to suboptimal allocations as objective indicators on potential revenues and expenditure needs were given little importance (OECD/The World Bank, 2015). Given the potential disincentives and risks inherent in central grants, it is very important that such grants are skilfully designed so as to facilitate adequate spending across all jurisdictions while reducing the risk of fiscal slippage across levels of government.

Variations in sub-central funding approaches may mitigate equalisation effects

Even if well-designed fiscal equalisation mechanisms are in place, decentralised systems may still be characterised by considerable differences in educational spending across jurisdictions. This might indicate a potential for efficiency savings in some jurisdictions and/or potential inequities in the educational services provided to students in different jurisdictions. Little internationally comparable information is available on variations in school spending between sub-central entities. However, in an online supplement to the OECD Education at a Glance 2016 sub-central data on annual expenditure per student is presented for three countries: Belgium, Canada and Germany.4 This data shows that while spending per student does not differ much between jurisdictions in Belgium (between USD 11 221 and USD 11 856), it ranges between USD 7 900 and USD 11 400 across jurisdictions in Germany and between USD 8 732 and USD 19 730 across jurisdictions in Canada.

In several of the OECD review countries, there is evidence of discrepancies in the level of school funding across countries’ different jurisdictions. In Israel, according to national data, more affluent local governments can provide up to 20 times higher funding per student for schools than less affluent local governments (OECD, 2016b). In Denmark, expenditure per student also varies strongly across municipalities despite existing equalisation mechanisms (Nusche et al., 2016b). Such differences might result from different levels of priority attributed by local authorities to education or different approaches to design local funding strategies. Where jurisdictions are autonomous in designing their own funding approaches, there may be only weak mechanisms to share and spread the related expertise and experience systematically across sub-central authorities so as to optimise funding mechanisms (for more information on the development of funding formulas at different levels of school systems, see Chapter 3).

In Denmark, more than half of the variation among municipalities can be explained by socio-economic conditions, with municipalities having more students from disadvantaged backgrounds spending higher amounts per student than other municipalities (Houlberg et al., 2016). However, there is still a large part of spending differences between municipalities that cannot be explained by socio-economic factors. This could indicate a situation where some municipalities prioritise spending on education more than others, but also a potential for efficiency savings in some municipalities. The spending differences across municipalities are also likely to result from differences in the approaches to school funding across jurisdictions. Each of the 98 municipalities designs its own formula to fund local schools. These formulas typically include parental background characteristics in addition to the number of students and the number of classes at the different year levels. However, the ways in which socio-economic differences are taken into account in the funding formulas vary greatly across municipalities. This suggests that the models vary not only as a result of deliberate decisions or different priorities (Nusche et al., 2016b).

In Kazakhstan, there is also evidence that regional and local differences in spending per students are not just related to objective cost factors. Expenditure per student varies greatly across regions – from 39% below the national average in the capital city to 50% above the national average in North Kazakhstan and marked differences in per student spending are also observed across school districts. The Ministry of Education and Science commissioned a report to UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) on the financing of 175 schools across Kazakhstan. The final report revealed important differences in spending per student between districts of the same region and between schools of the same type and size within the same district (UNICEF, 2012). Some sub-central governments spend significantly more of their resources on education than others and the existing differences are not always associated with the variation in the costs of provision (OECD/The World Bank, 2015).

Fiscal decentralisation may raise capacity challenges, especially in small jurisdictions

While their knowledge of local conditions and needs may allow sub-central authorities to allocate resources more effectively in line with school contexts, smaller authorities are very likely to face capacity challenges. Decentralised governance arrangements place significant demands on local authorities for budget planning and financial management. For example, they may be required to develop a funding formula, administer financial transfers, make decisions about investments in school infrastructure and maintenance and/or apply for a pool of targeted funding. But not all local authorities have sufficient capacity to implement sound budget planning and to manage their resources well. Administering a funding scheme requires considerable technical skills and administrative capacity and many school systems find it challenging to ensure these are available at the level of each educational provider.

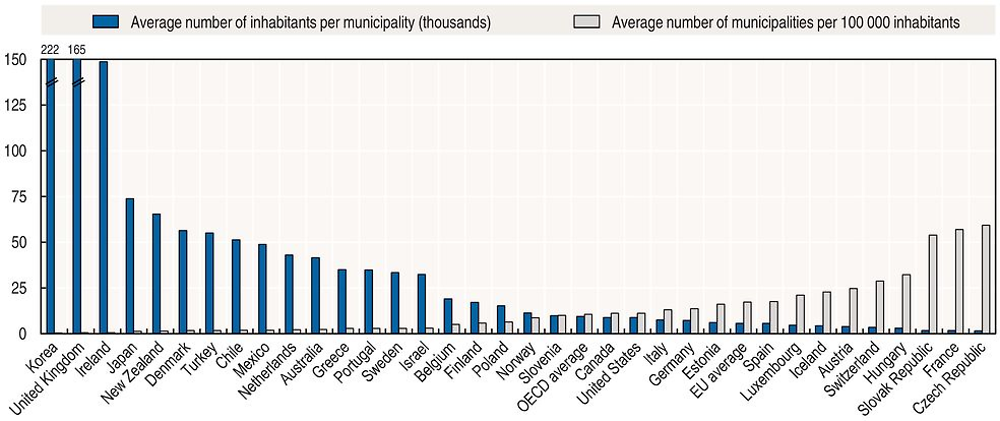

Capacity constraints at the local level can also exacerbate inequities between individual authorities, in particular in countries that have many municipalities with a small number of inhabitants, such as the Czech Republic, France, the Slovak Republic, Hungary, Switzerland and Austria (Figure 2.7). In some countries, school providers (sub-central authorities or other school owners) are very small and responsible for only one or a few schools, which does not allow them to achieve the same extent of economies of scale, management capacity and support that can be offered by larger providers. Small providers typically have a very limited number of staff managing school services, and these do not necessarily have expertise regarding the design of effective resource management strategies. Some of the OECD review countries, such as Austria, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, literally have thousands of municipalities involved in managing and funding their own schools, many of them with weak administrative capacity, which makes it difficult for them to maintain efficient school services.

Source: OECD (2015a), “Sub-National Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data” (brochure), OECD, Paris.

While school leaders are typically accountable to their providers, not all providers have the professional capacity to provide effective feedback and support to their leaders. It can, therefore, be difficult for local authorities to fulfil their responsibility for managing financial resources and to collaborate with their school leaders to make resource use decisions that improve learning. In contexts where responsibilities for resource management and the pedagogical organisation of schools are shared between local authorities and schools, education leaders and administrators must be able to establish good relationships and to align resource management decisions with pedagogical aspects and needs. One way for building the capacity of local authorities lies in the creation of networks and collaborative practices (Box 2.4 provides an example from Norway), but these are still underdeveloped in many contexts.

Municipal networks for efficiency and improvement in Norway

In Norway, policy making is characterised by a high level of respect for local ownership. In such a decentralised system, it is essential that different actors co-operate to share and spread good practice and thereby facilitate system learning and improvement. Networking is a common form of organisation among municipalities in Norway and there are a range of good examples where networks and partnerships have been established between different actors as a means to take collective responsibility for quality evaluation and improvement. In Norway, there are many examples of localised collaboration initiatives launched and developed by small clusters of municipalities. As an example, in 2002, in Norway, the Association of Local and Regional Authorities (Kommunesektorens interesse- og arbeidsgiverorganisasjon, KS), the Ministry of Labour and Government Administration, and the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development set up “municipal networks for efficiency and improvement” that offer quality monitoring tools for municipal use and provide a platform for municipalities to share experience, compare data and evaluate different ways of service delivery in different sectors. For the education sector, an agreement was established between KS and the Directorate for Education and Training to allow the networks to use results from the user surveys that are part of the national quality assessment system.

Local government reform in Denmark

Denmark re-organised its public sector through a Local Government Reform in 2007. This reform reduced the number of municipalities from 271 to 98 and abolished the 14 counties replacing them with five regions. Except for some smaller islands, most of the 98 municipalities have a minimum size of 20 000 inhabitants. The reform also redistributed responsibilities from former counties to municipalities, leaving the municipalities responsible for most welfare tasks, and reduced the number of levels of taxation from three to two as regions were not granted the authority to levy taxes. Regional revenues consist of block grants and activity-based funding from the central government and the municipalities. In addition, to ensure that the local government reform would not result in a redistribution of the cost burden between municipalities, the grant and equalisation system was reformed to take into account the new distribution of tasks. The reform sought to primarily improve the quality of municipal services, but also to address efficiency concerns (e.g. by creating economies of scale). Many of the 271 municipalities that existed prior to 2007 were considered too small to provide effective local services, in particular in the health sector.

The creation of Local Education Services in Chile

In Chile, a 2015 reform proposal intends to remove management of public schools from the 347 municipalities and create a new system of public education. The draft law proposes the creation of a National Directorate for Public Education (within the Ministry) which will co‐ordinate 67 new Local Education Services, each of which will oversee a group of schools with powers transferred from the 345 municipalities). Prior to this reform, a number of different options for reforming the municipal school system were envisaged and a central concern was to ensure adequate accountability mechanisms to monitor the effective, efficient and equitable use of resources at sub-central levels (Santiago et al., forthcoming).

Source: Nusche, D. et al. (2011), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Norway 2011, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264117006-en; Nusche, D. et al. (2016b), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Denmark 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264262430-en; Santiago, P. et al. (forthcoming), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Chile, OECD Publishing, Paris.

One of the specific challenges of educational decentralisation is that while key decisions (e.g. distribution of financial resources, quality assurance) are typically transferred to regional or local authorities, most of the information and knowledge management capacities are retained by the institutions of the national administration. Therefore, many of them might require active support from the relevant national institutions to take and implement decisions. Some countries have responded to size and capacity challenges at sub-central government level by merging several small education providers and thereby consolidating capacity for effective resource management (Box 2.4 provides an example from Denmark). Others are considering to move responsibilities to higher levels of the administration or to create new bodies to administer a larger number of schools (Box 2.4 provides an example from Chile).

Complexities in the governance of school funding risk leading to inefficiencies

Co-ordination is a very important and challenging aspect of governance in every system where sub-sectors of schooling operate under different political and administrative jurisdictions. The decentralisation processes developed in some countries have led to the emergence of increasingly autonomous and powerful local actors (e.g. regions, municipalities, schools) and raise the question of how to assure co-ordination in this new context of multi-level and multi-actor governance. The complexity of education governance might create inefficiencies in the use of resources due to duplication of roles, overlapping responsibilities, competition between different tiers of government and a lack of transparency obfuscating the flow of resources in the system (Chapter 5).

Efficiency challenges in using school resources may be linked with the potential isolation of sub-systems managed by different levels of administration and the rather rigid boundaries between them. The relative isolation of sub-systems might also be accompanied by a low intensity of communication between the administrative authorities responsible for these sub-systems. In Estonia, for example, while different levels of the administration offer competing services at most levels of education, the municipalities are the main provider of general secondary education while the state is the main provider of vocational secondary education. As a result, the general and the vocational sub-systems are relatively isolated from each other. This makes it difficult for sub-systems to share resources (for example teachers, special educational services or facilities) and to allow students to move easily between school types in line with their interests, talents and needs (Box 2.5). Challenges of isolated or competing sub-sectors are also faced by the Austrian school system where there is a parallel offer of federal and provincial schools at the lower secondary level, and in the Flemish Community of Belgium, where the school offer is organised within three different educational “networks” which each have their own legal and administrative structures (Box 2.5).

In Estonia, the municipal and the state owned schools offer competing services in general education, in special needs education and – to a lesser extent – in vocational education and training. This results in reduced clarity of the responsibilities for setting the funding rules. At the time of the OECD review visit in 2015, the government was aiming to transfer responsibilities among tiers of government so as to provide greater clarity of funding and management responsibilities for each sector. The central government had a medium-term intention of establishing a more streamlined division of labour within public education, whereby municipalities should provide funding for pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education while the state should take responsibility for the entire upper secondary sector (both general and vocational schools) and special education schools. This was expected to reduce unnecessary duplication; provide the potential for better co‐ordination within education levels (or school types); establish closer linkages between funding, school management and accountability; facilitate the alignment between education strategic objectives and school level management; reduce ambiguities in defining who is responsible for what; and assist with school network planning. For example, having the state take responsibility for both vocational and general upper secondary education is likely to facilitate bridges between the two sectors and allow upper secondary education to be managed as a unified sub-system.

In Austria, at the time of the OECD review visit in 2016, lower secondary education was offered both by the federal level (academic secondary schools) and the provincial level (New Secondary Schools, which are jointly funded by the federal government [responsible for teacher salaries] and the municipalities [responsible for all other funding]). The two types of lower secondary education share a common curriculum and similar educational goals but the systematic management and coherent funding of lower secondary education remain challenging due to the fragmented distribution of responsibilities between the federal, provincial and municipal level. At the time of the OECD review visit in 2016, the government was seeking ways to streamline the governance and funding of its school system. Reform proposals included the creation of a more unitary governance structure, which should overcome the formal division between federal and provincial schools. Given the history of political struggles between the federal and the provincial governments, the whole-sale delegation of funding for teachers, operational costs and infrastructure to either the federal or the provincial government appeared politically difficult. The OECD review team recognised that any future arrangement would most likely have to be a political compromise in the sense that both levels would continue to be involved.

In the Flemish Community of Belgium, school education can be classified in three “networks” providing school education. Two of these networks can be classified as providers of public education (Flemish Community schools and municipal and provincial schools). Within each network, schools provide education at the different levels of schooling from pre-primary through to upper secondary, as well as adult education. The different educational networks have different central organisations (the Flemish Community Education – GO! and the so‐called “umbrella organisations” with a legal personality) employing administrative staff and operating their own pedagogical advisory services and student guidance centres funded by the Flemish government. Collaboration between schools pertaining to the different networks remains relatively rare. The division of public education in two educational networks involves considerable overhead and administration costs and leaves considerable potential for efficiency savings. At the time of the OECD review visit in 2014, several of the groups consulted argued that there would be benefits creating a single network that would cover all public schools, both the Flemish Community schools and the schools managed the municipalities and provinces. The review team considered that the potential merger of the two public networks deserved review and serious consideration as it would help reduce overhead and administration costs across the two smaller networks. In the context of reforms to optimise the structure of school administration, the review team also recommended reviewing the size of school boards within the different networks, with a special focus on determining the potential for merging school boards.

In the Czech Republic, the regional level has two separate roles in the education financing system. The first is receiving an education grant from the central budget to finance the schools under its managerial control (secondary schools), and allocating these funds to individual schools. In this respect, the Czech regions are just like any local governments among the post-communist countries. The second role is receiving an education grant from the central budget for schools managed by the municipalities (basic schools), and then redistributing these funds among the municipalities according to an allocation formula set by each region. In this regard, the Czech regions act like extensions of the national government and have much power over the municipal budgeting process. This double role of regions in the financing of the Czech education system is quite unusual among the post-communist countries. It creates a dependency of municipalities on regions, thus making the first tier of local government (municipalities) partially subordinate to the second tier (regions). The OECD review team in the Czech Republic suggested that direct transfers between the ministry and the municipalities that manage the schools could help promote policy dialogue and enable the central level to improve the central understanding of the challenges of the Czech school system and to better plan its development. The main difficulty confronting this approach is the extremely small size of the Czech municipalities and the fact that most of them have one school, if any at all. The review team suggested that a solution could be to entrust funding only to municipalities with extended powers, as is already the case with a number of locally delivered public services in the Czech Republic. In this way not all municipalities would be recipients of the grant. The review team recognised that transfers to municipalitieswith extended powers, completely bypassing the regions, would have to use more complex and flexible formulas. Nevertheless, the team had no doubts that these formulas could be designed to be far more simple and comprehensible than the current formulas for basic education used by the regions.

Source: Nusche, D. et al. (2016a), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Austria 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264256729-en; Shewbridge, C. et al. (2016b), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Czech Republic 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264262379-en; Santiago, P. et al. (2016a), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Estonia 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264251731-en; Nusche, D. et al. (2015), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Flemish Community of Belgium 2015, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264247598-en.

Challenges may also arise when several sub-central tiers of government are involved in distributing central funding thus establishing a hierarchy between the different levels. In the Czech Republic, for example, regions act as intermediaries in the funding between the central level and municipalities, which complicates the flow of resources from the central level to the end users (schools) (Box 2.5). Intermediary actors and additional layers of decision making can cause frictions and complicate monitoring and evaluation of resource use to the detriment of equity and efficiency. Such complex arrangements can also make it difficult to manage information on the use of school funding and how it translates into outcomes (Chapter 5). In decentralised school systems, the development of effective school funding mechanisms requires governance models that establish a clear division of responsibilities across different levels of the administration, build capacity at each of these levels and develop clear lines of accountability, using data and evidence effectively for policy making and reform (Chapter 5).

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that complexities may also arise in centralised governance settings if multiple actors or agencies are involved in school funding. In Uruguay, while the governance of education is highly centralised, it is also highly fragmented. The system operates with four education councils for distinct sub-systems (pre-primary and primary education; general secondary education; technical-professional secondary programmes; teacher training) that operate in a rather independent manner. As a result, school education is not governed as a system, but as a number of rather isolated sub-systems. Each area of policy (e.g. human resources, curriculum, budget, infrastructure, planning) is independently addressed within each education council – each council has independent units covering these policy areas while a central governing council replicates the same units but with no oversight upon the corresponding units of the councils. This institutional design does not ensure enough co-ordination across educational levels and types.

Schools hold considerable responsibility for managing and allocating their funds

Over the past three decades, many education systems, including those in Australia, Canada, Finland, Hong Kong (China), Israel, Singapore, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom, have granted their schools greater autonomy in both curricula and resource allocation decisions (Cheng et al., 2016; Fuchs and Wöβmann, 2007; OECD, 2016b; Wang, 2013). A higher degree of school autonomy typically involves greater decision-making power and accountability for school principals, and in some cases also for groups of teachers or middle managers such as heads of departments in schools. However, the school systems in OECD and partner countries have different points of departure and differ in the degree of autonomy granted to schools and in the domains over which autonomy is awarded to schools.

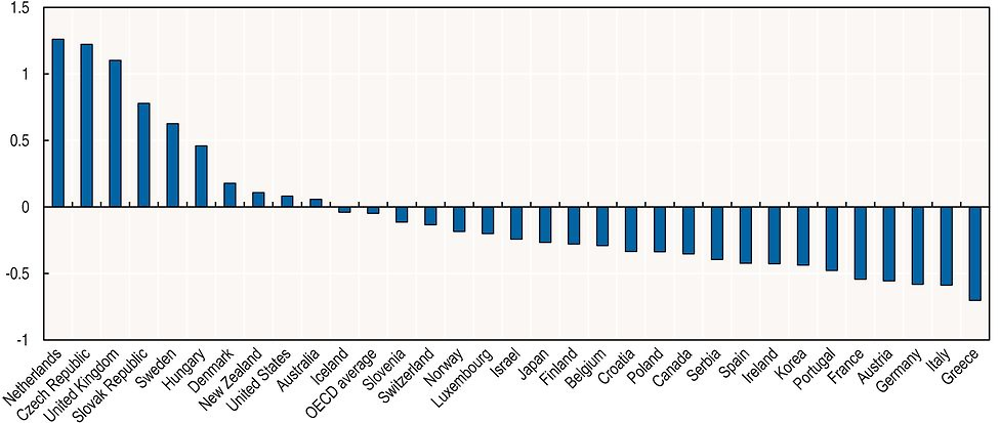

Figure 2.8 presents comparative data on the autonomy of schools from the OECD 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which also surveyed school principals about their degree of autonomy regarding decisions about the local school environment. The figure presents an index based on principals’ responses regarding their autonomy in selecting teachers for hire, dismissing teachers, establishing teachers’ starting salaries, determining the teachers’ salary increases, formulating the school budget and deciding on budget allocations within the school (OECD, 2013a). As the figure shows, school autonomy in resource allocation was lowest in countries such as Greece, Italy, Germany, Austria, France and Portugal. On the opposite end of the spectrum, schools in countries such as the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom, the Slovak Republic and Sweden had high degrees of autonomy in resource allocation.

Source: OECD (2013a), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful (Volume IV)? Resources, Policies and Practices, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en, p. 131.

In countries with a strong focus on school autonomy in resource allocation, most funding going to schools is typically not earmarked, which gives schools flexibility to use resources to fit their specific needs. As a result, these schools are responsible for resource policy issues such as setting up budgeting and accounting systems, communicating with relevant stakeholders about resource use, recruiting and dismissing school staff, making decisions about the use of teacher hours, maintaining the school infrastructure, buying materials and establishing relationships with contractors and vendors. Autonomy in resource management decisions provides the conditions for schools to use resources in line with local needs and priorities.

By contrast, in countries where funding arrangements are established in a context of little resource allocation autonomy, schools typically need to follow strict rules to execute their budgets or they manage a very limited budget. They might also not be allowed to select their own staff or organise teacher hours the way they see fit. In addition, they might not be able to save up and transfer funds from one year to the next, take out loans, or generate own revenues. Also, in contexts of limited school autonomy, schools tend not to have their own accounts and, therefore, may depend entirely on education authorities for support in maintenance and operating costs. In highly decentralised systems, such as Chile and Iceland, the level of autonomy of schools may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, with schools in some municipalities having greater autonomy than in others (Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2014; Santiago et al., forthcoming).

In Chile, for example, the operation of schools that receive public funding is the responsibility of school providers (municipalities or private providers) but school providers may delegate responsibilities to schools. The precise distribution of tasks and responsibilities between school providers and schools, and therefore the degree of school autonomy for the use and management of resources, depends on individual school providers. This arrangement allows school providers to take over administrative and managerial tasks and thus free school leaders to concentrate on their pedagogical role. But for schools that have fewer opportunities to influence their providers’ management decision, this makes it difficult to align resource management decisions with particular school needs (Santiago et al., forthcoming).

In many countries, schools have inequitable access to resources

While sub-central discretion over the distribution of funding allows sub-central actors to develop resource strategies in line with identified needs, in some countries it also raises concerns regarding the equity of resource distribution between their schools. In Chile, for example, it was noted that local autonomy regarding the allocation of basic grants to schools creates the opportunity for sharp differences in per student spending within municipalities, as well as a lack of transparency that may benefit schools with well-connected principals (Santiago et al., forthcoming). Also, in the Flemish Community of Belgium, where funding for operational costs is attributed to school boards and then further distributed among the schools, there is evidence that school boards responsible for several schools use their own weightings and strategies to allocate financial means to schools. As a result, there is no guarantee that central funding (which is weighted for socio-economic disadvantage of each school’s student body) will indeed benefit the schools with the most challenging socio-economic characteristics (Nusche et al., 2015).

Another source of inequity may arise from differences in schools’ ability to generate and use their own revenues. While the generation of own income can help complement school-level resources, it raises a number of equity concerns. First, in some countries not all types of schools have the same revenue generating powers. In Austria, for example, schools that are run and funded directly by the federal level have a certain degree of budgetary autonomy as they are able to rent out their school facilities and have control over their own accounts, even if the extent of revenues generated through such activities appears to be minor. By contrast, schools that are run and funded by the provinces and municipalities do not have such autonomy in financial matters, thus presenting an inequity in the system. They cannot generate additional income and depend entirely on their municipality for support in maintenance and operating costs (Nusche et al., 2016a).

Second, the capacity of schools to generate additional revenue is generally influenced by the socio-economic composition of community that they serve. To highlight socio-economic gaps in the ability of schools to raise funds, it is helpful to look at patterns in school systems which routinely collect the relevant income data, as is done in some school systems. In Western Australia, for example, it was shown that among schools of similar size, parental contributions rise in line with socio-economic status (SES) and are 16 times higher among the largest and highest SES schools than they are among the smallest and lowest SES schools. It is often small schools and those located in socio-economically disadvantaged areas that experience the greatest pressure of need, due to the concentration of multiple disadvantages in them. But these schools typically also have the least opportunity to generate additional revenue and thus the least flexibility in budget terms (Teese, 2011).

Third, in many countries the relevant school income data is not collected, thus leading to a lack of transparency regarding the real resource levels of individual schools. In the Slovak Republic, for example, financial contributions from parents in state schools are not sufficiently transparent with respect to the items they fund and how they are recorded. According to a study published in 2007 and cited in Santiago et al. (2016c), between 70% and 90% of parents pay for various services, such as school events, extracurricular activities or teaching materials. There is also some anecdotal evidence that suggests that some schools place pressure on parents to pay such contributions, which is inequitable. Households in the Slovak Republic contribute 15% of pre-primary education expenditure and 10% of primary and secondary expenditure. While private contributions to public services can have benefits, they require increased attention to integrity and equity considerations (Santiago et al., 2016c).

Limited resource autonomy may constrain strategic development at the school level

The relationship between school autonomy in managing own resources and performance outcomes is not clear cut. Evidence from PISA indicates that while student performance is higher where school leaders hold more responsibility for managing resources, this is only significant in countries where the level of educational leadership is above the OECD average (OECD, 2016c). The effect of delegating more autonomy for resource management to schools depends on schools’ ability to make use of this autonomy in a constructive way and thus requires a strengthening of school leadership and management structures (more on this below). Furthermore, autonomous schools need to be embedded in a comprehensive regulatory and institutional framework in order to prevent adverse effects of autonomy on equity across schools. The results from PISA suggest that when autonomy and accountability are intelligently combined, they tend to be associated with better student performance (OECD, 2016c).

Findings from the OECD country reviews indicate that an absence of resource autonomy at the school level risks constraining schools’ room for manoeuvre in developing and shaping their own profiles and may create inefficiencies in resource management. In Uruguay, for example, schools have very limited autonomy over the management or allocation of their budget. Not only do central authorities manage school budgets, the recruitment of teachers and the allocation of infrastructure and equipment but they also retain decision-making power over less fundamental aspects of school operation such as the acquisition of instructional materials, ad hoc repairs at schools and the approval of schools’ special activities. Little local and school autonomy hinders effectiveness in the use of resources as local authorities and schools are unable to match resources to their specific needs, and in consideration of their conditions and context. Also, responses from central educational authorities to an emerging school need can prove very slow. In addition, limited autonomy disempowers school and local actors and makes it more difficult to hold local players accountable, in particular school leaders, as they do not have the responsibility to take most of the decisions (Santiago et al., 2016b).

Devolution of resource management to schools requires adequate leadership capacity

As part of a general move towards greater school autonomy, many countries have attributed greater resource responsibilities to their school leadership teams. While offering potential for effective strategic management at the school level, such budgetary devolution creates new challenges for resource management in schools. School leaders in such contexts are increasingly asked to fulfil responsibilities that call for expertise they may not have through formal training. Where resource management responsibilities are sharply increasing without additional support for leadership teams, it will be difficult for schools to establish robust management processes where resources are directed to improvement priorities and support learning-centred leadership (Plecki et al., 2006; Pont et al., 2008).

Where schools have autonomy over their own budgets, they must be able to link the school’s education priorities with its spending decisions, for example by making connections between school development planning and budget planning (Chapter 4). In particular where targeted funding is available to provide disadvantaged schools with additional funding (Chapter 3), this is often tied to the requirement to develop a school improvement plan deciding how funds are used for the benefit of disadvantaged students and with accountability requirements (Chapter 5). Administrating and allocating such additional funding effectively requires time, administrative capacity and strategic leadership within schools. Evaluations of targeted programmes show mixed results and indicate that the success of these programmes depends on whether conditions for effective allocation and use of funding are in place at the school level (Scheerens, 2000).

If targeted funding is distributed to schools without further guidance and support, school staff may not know how to fit these special initiatives into their school development plans or they may use the additional money for measures that have not demonstrated to be effective (Kirby et al., 2003; Karsten, 2006; Nusche, 2009). In Chile, for example, school leaders often make limited use of school improvement planning which is required in return for additional funding through the preferential school subsidy (Subvención Escolar Preferencial, SEP). Resources from this subsidy can be used to contract external pedagogical-technical support, but schools and school providers do not always have the capacity to make an informed choice to select a service of high quality that meets actual needs and to monitor the implementation and the effects of the intervention (Santiago et al., forthcoming).

A further challenge concerns the potential tension between pedagogical and administrative/managerial leadership. On the one hand, school autonomy in resource management can be part of strategic learning-centred leadership as it allows aligning spending choices with the pedagogical necessities of schools. But on the other hand, school autonomy places an administrative, managerial and accounting burden on school leaders which may reduce their time available for pedagogical leadership (e.g. coaching of their teaching staff). This tension is also relevant for the training and evaluation of school leaders, which need to prepare school leaders for their financial and administrative responsibilities, but within a framework of pedagogical leadership (Pont et al., 2008; OECD, 2013b).

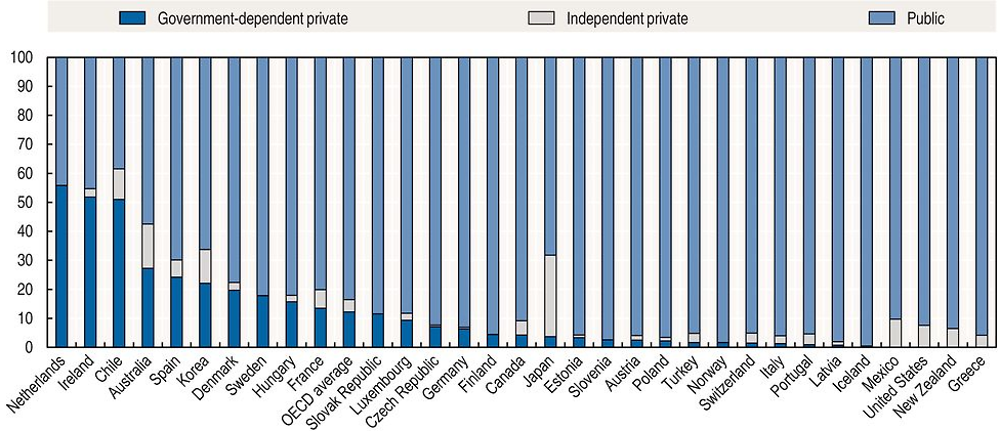

The public funding of private providers has strengthened private actors in schooling