Chapter 1. Overview and policy recommendations in Cambodia

Cambodia is missing opportunities to harness the development potential of its high rates of emigration. The Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development (IPPMD) project was conducted in Cambodia between 2013 and 2017 to explore through both quantitative and qualitative analysis the two-way relationship between migration and public policies in four key sectors – the labour market, agriculture, education, and investment and financial services. This chapter provides an overview of the project’s findings, highlighting the potential for migration in many of its dimensions (emigration, remittances and return migration) to boost development, and analysing the sectoral policies in Cambodia that will allow this to happen.

International migration has the potential to become an important determinant for development in Cambodia, given its increasing social and economic impact. Despite the county’s steady economic growth at around 7% since 2010, labour market demand has not been sufficient to meet the increase in the working population, in particular for young people. Furthermore, poverty remains at a significant level although there are signs that it is declining. Many households choose migration as a strategy for improving their livelihoods. The key question now is how to create a favourable policy environment to make the most of migration for development in Cambodia.

In this context, this report aims to provide policy makers with empirical evidence of the role played by migration in policy areas that matter for development. It also explores the influence on migration of public policies not specifically targeted at migration (Box 1.1). This chapter provides an overview of the findings and policy recommendations for taking the interrelations between migration and public policies into account in development strategies.

In January 2013, the OECD Development Centre launched a project, co-funded by the EU Thematic Programme on Migration and Asylum, on the Interrelations between public policies, migration and development: case studies and policy recommendations (IPPMD). This project – carried out in ten low and middle-income countries between 2013 and 2017 – sought to provide policy makers with evidence of the importance of integrating migration into development strategies and fostering coherence across sectoral policies. A balanced mix of developing countries was chosen to participate in the project: Armenia, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, the Dominican Republic, Georgia, Haiti, Morocco and the Philippines.

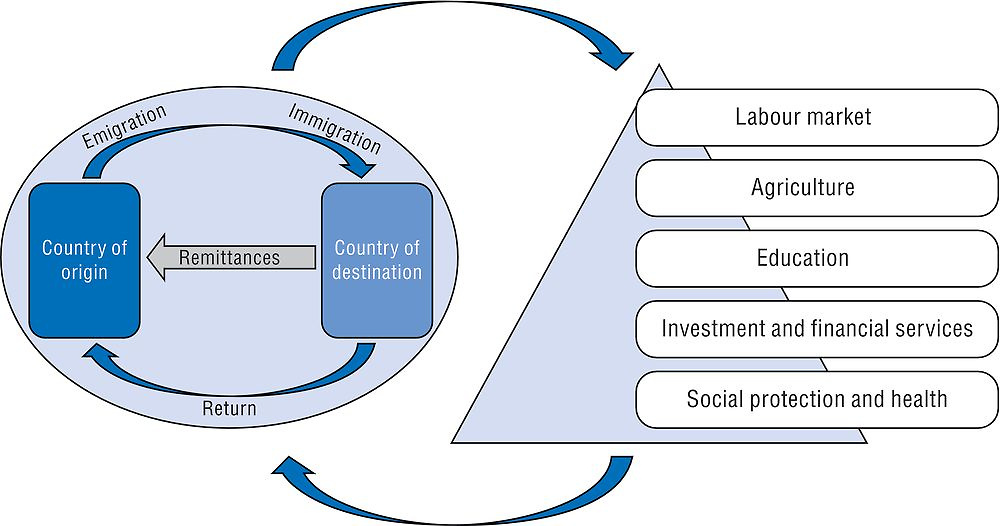

While evidence abounds of the impacts – both positive and negative – of migration on development, the reasons why policy makers should integrate migration into development planning still lack empirical foundations. The IPPMD project aimed to fill this knowledge gap by providing reliable evidence not only for the contribution of migration to development, but also for how this contribution can be reinforced through policies in a range of sectors. To do so, the OECD designed a conceptual framework that explores the links between four dimensions of migration (emigration, remittances, return migration and immigration) and five key policy sectors: the labour market, agriculture, education, investment and financial services, and social protection and health (Figure 1.1). The conceptual framework also linked these five sectoral policies to a variety of migration outcomes (Table 1.1).

The methodological framework developed by the OECD Development Centre and the data collected by its local research partners together offer an opportunity to fill significant knowledge gaps surrounding the migration and development nexus. Several aspects in particular make the IPPMD approach unique and important for shedding light on how the two-way relationship between migration and public policies affects development:

-

The same survey tools were used in all countries over the same time period (2014-15), allowing for comparisons across countries.

-

The surveys covered a variety of migration dimensions and outcomes (Table 1.1), thus providing a comprehensive overview of the migration cycle.

-

The project examined a wide set of policy programmes across countries covering the five key sectors.

-

Quantitative and qualitative tools were combined to collect a large new body of primary data on the ten partner countries:

-

A household survey covered on average around 2 000 households in each country, both migrant and non-migrant households. Overall, more than 20 500 households, representing about 100 000 individuals, were interviewed for the project.

-

A community survey reached a total of 590 local authorities and community leaders in the communities where the household questionnaire was administered.

-

Qualitative in-depth stakeholder interviews were held with key stakeholders representing national and local authorities, academia, international organisations, civil society and the private sector. In total, 376 interviews were carried out across the ten countries.

-

The data were analysed using both descriptive and regression techniques. The former identifies broad patterns and correlations between key variables concerning migration and public policies, while the latter deepens the empirical understanding of these interrelations by also controlling for other factors.

In October 2016, the OECD Development Centre and European Commission hosted a dialogue in Paris on tapping the benefits of migration for development through more coherent policies. The event served as a platform for policy dialogue between policy makers from partner countries, academic experts, civil society and multilateral organisations. It discussed the findings and concrete policies that can help enhance the contribution of migration to the development of both countries of origin and destination. A cross-country comparative report and the ten country reports will be published in 2017.

Why was Cambodia included in the IPPMD project?

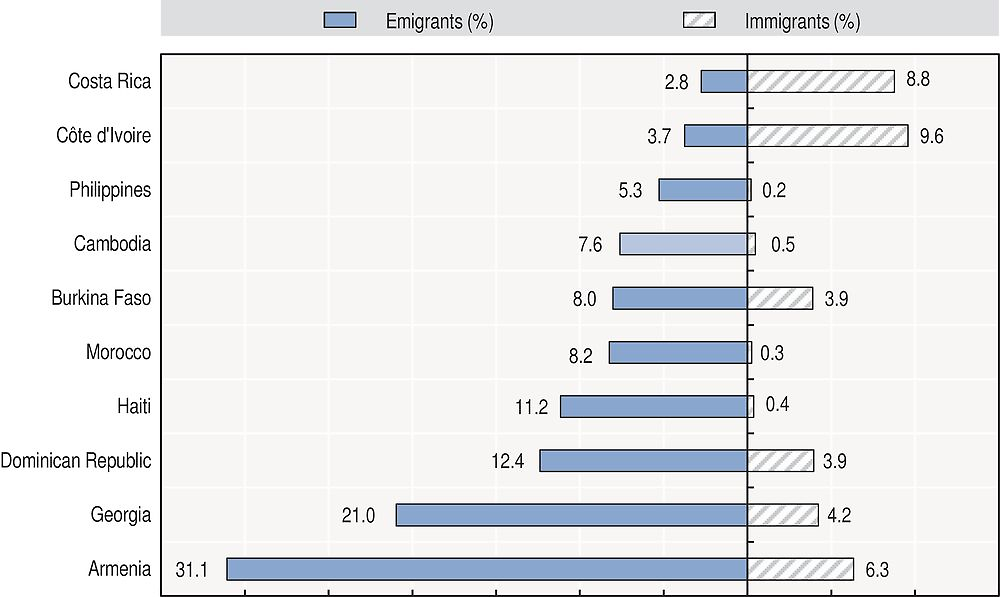

The weight of emigration is significant in Cambodia. Data from the United Nations indicate that there were an estimated 1.2 million Cambodian migrants in 2015, equivalent to around 7.6% of Cambodia’s total population (Figure 1.2). While this is a smaller share than in most of the IPPMD partner countries, what is notable is how quickly the stock of emigrants has grown. The statistics show that between 2000 and 2015, the stock of emigrants increased from around half a million to 1.2 million (an increase of about 160%) (Chapter 2). In addition, according to the IPPMD data, about 10% of Cambodians aged 15 and older plan to emigrate, which is near the average for the ten partner countries.

Note: Data come from national censuses, labour force surveys, and population registers.

Source: UN DESA (2015), International Migration Stock: The 2015 Revision (database), www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml.

Remittances sent home by emigrants constitute an important source of income for many households in Cambodia. They have the potential to improve the well-being of migrant households and spur economic and social development. In 2015, the inflow of remittances to Cambodia reached USD 542 million, constituting 3% of national income (World Bank, 2016). The volumes and modes of sending remittances depend on multiple factors, including the characteristics of the migrants and the sending and receiving costs. A comparison of the ten IPPMD partner countries shows that remittance flows to Cambodia are subject to transaction costs of 13% of the remittance value, the highest costs in the sample (Figure 1.3), and considerably higher than the 3% target of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (UN, 2015).

Note: Data are for the second quarter of 2016, weighted by the share of emigrants in the IPPMD data in each main remittance corridor. Data for Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire are not available. The line represents a cost of 3%, the broad target of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (UN, 2015). The costs calculations for Cambodia are based on transaction costs in the Thailand-Cambodia remittance corridor.

Source: Authors’ own work based on World Bank Remittance Prices Worldwide data, http://remittanceprices.worldbank.org.

How did the IPPMD project operate in Cambodia?

In Cambodia, the IPPMD project team worked with the Ministry of Interior (MOI) as the government focal point. The MOI provided information about country priorities, data and policies and assisted in the organisation of country workshops and bilateral meetings. The IPPMD team also worked with the Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI) to ensure the smooth running of the project. CDRI helped organise country-level events, contributed to the design of the research strategy in Cambodia, conducted the fieldwork and co-drafted the country report.

The IPPMD project team organised several local workshops and meetings with support from the Delegation of the European Union to Cambodia. The various stakeholders who participated in these workshops and meetings, and who were interviewed during the missions to Cambodia, also played a role in strengthening the network of the project partners and setting the research priorities in the country.

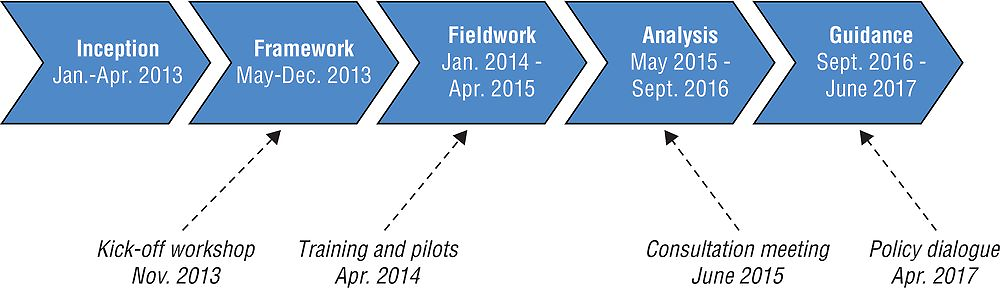

A kick-off workshop, held in November 2013 in Phnom Penh, launched the project in Cambodia (Figure 1.4). The workshop served as a platform to discuss the focus of the project in the country with national and local policy makers, and representatives of international organisations, employer and employee organisations, civil society organisations and academics. Participants agreed that the project should focus on emigration, not immigration, in Cambodia. Following lively and wide-ranging discussions, the IPPMD project team decided to focus the analysis on four sectors: 1) the labour market; 2) agriculture; 3) education; and 4) investment and financial services.

Following a training workshop and pilot tests conducted by the IPPMD project team, the CDRI collected quantitative data from 2 000 households and 100 communities and conducted 28 qualitative stakeholder interviews (Chapter 3). A consultation meeting to present the preliminary findings to relevant stakeholders, including policy makers, academic researchers and civil society organisations, was organised in June 2015. The meeting discussed the various views and interpretations of the preliminary results to feed into further analysis at the country level. The project will conclude with a policy dialogue to share the policy recommendations from the findings and discuss with relevant stakeholders concrete actions to make the most of migration in Cambodia.

What does the report tell us about the links between migration and development?

The findings of this report suggest that the development potential embodied in migration is not being fully exploited in Cambodia. Taking migration into account in a range of various policy areas can allow this potential to be tapped. The report demonstrates the two-way relationship between migration and public policies by analysing how migration affects key sectors – the labour market, agriculture, education, and investment and financial services (Chapter 4) – and how it is influenced by policies in these sectors (Chapter 5).

Labour market policies are doing little to stem emigration

Losing labour to emigration can have a significant impact on certain economic sectors, especially as migrants are often in the most productive years of their lives. More than 80% of the current emigrants in the data collected on Cambodia are between the ages of 15 and 34. Agriculture is clearly losing more labour to emigration than other sectors such as construction, education and health. This theme was highlighted in the stakeholder interviews, too. The reduced labour supply has led to a shortage of Cambodian agricultural workers, particularly on rice farms and during the harvest seasons.

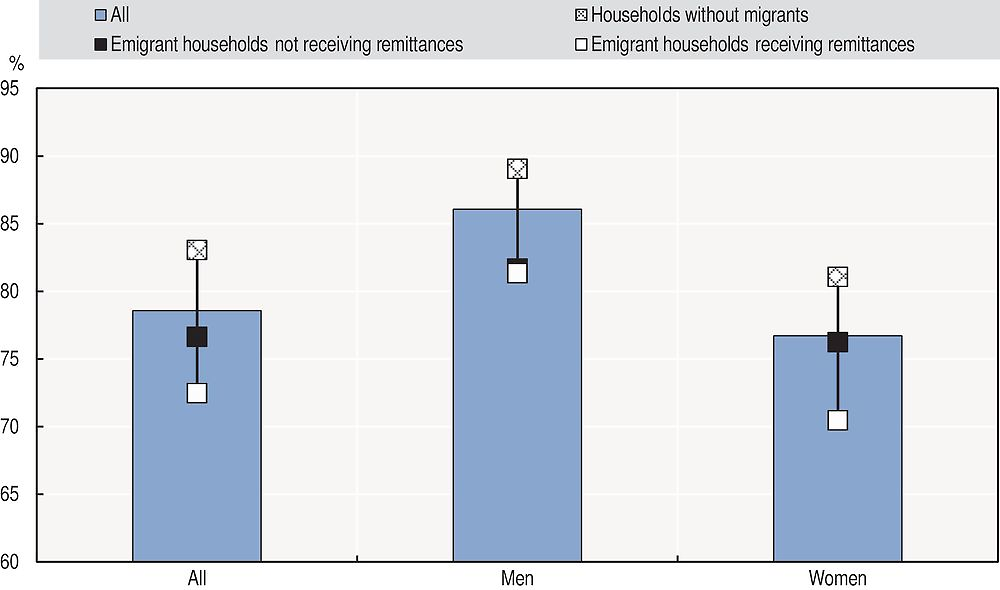

Migration changes the labour dynamics within households, too. Households with emigrants tend to have a lower share of working members than households without emigrants; this effect is strongest in agricultural households. This suggests that emigrants’ labour is not being replaced during their absence. Receiving remittances also negatively affects households’ labour force participation. Women, in particular, are less likely to work when their households receive remittances (Figure 1.5).

Note: The sample excludes households with return migrants only.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

What is the influence of labour market policies on migration? The IPPMD research finds that government employment agencies tend to curb emigration by providing people with better information on the Cambodian labour market. However, the share of people in the sample finding work through these agencies is low – at 4%.

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) are seen in Cambodia as key tools to improve skills, and are highlighted in the 2015-2025 National Employment Policy. The IPPMD survey finds, however, that only 5% of the surveyed labour force had participated in a vocational training programme – mainly on agricultural themes. While in some countries in the IPPMD study, vocational training programmes appear to be helping would-be migrants be more employable overseas, the Cambodia results show no evidence of links between vocational training programmes and plans to emigrate.

On the other hand, public employment programmes (PEPs) – e.g food-for-work and cash-for-work schemes – seem to have a link with higher emigration. The average share of households with emigrants is higher in communities which offered PEPs than in those that did not. The increased income received through PEPs may have financed emigration by household members.

Agricultural subsidies influence emigration

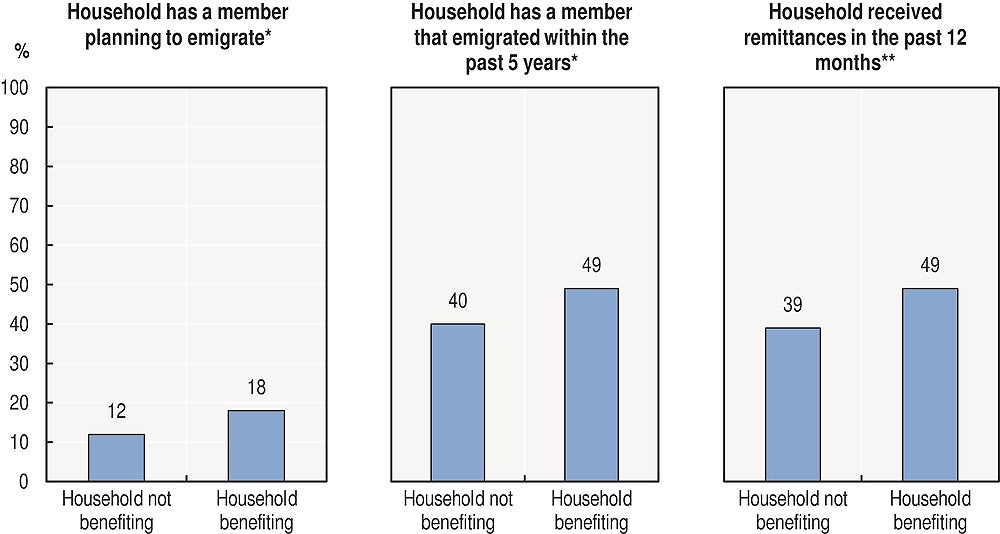

As seen above, emigration from rural areas can create labour shortages in Cambodia’s agricultural sector. The IPPMD analysis also finds that agricultural policies may in fact be encouraging emigration by members of farming households. Households in the IPPMD sample benefiting from agricultural subsidies are more likely to have a member plan to emigrate or have an emigrant member (Figure 1.6). This suggests that agricultural subsidies are enabling emigration by providing enough additional income to cover the costs of emigration. The results also show that households receiving agricultural subsidies were more likely to receive remittances than those not benefiting. By providing households with the means to produce and invest in their land through, for example, quality seeds, subsidies may be providing the incentive for emigrants to send remittances to capitalise on this investment. However, by analysing the data deeper, it is found that agricultural subsidies influence emigration, which in turn leads to remittances. As households receiving agricultural subsidies are more likely to have emigrants, they are also more likely to be receiving remittances from these emigrants.

Note: Results that are statistically significant are indicated as follows: ***: 99%, **: 95%, *: 90%. Only members planning to emigrate within the next 12 months are considered in the left-most panel.

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

Returns to education are lower than the benefits of emigrating

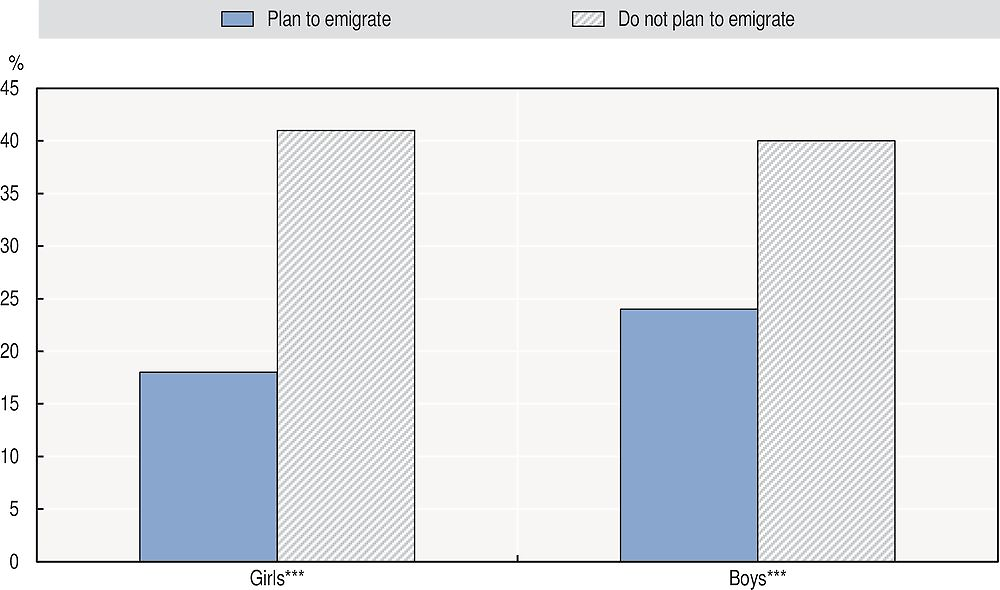

The IPPMD results for Cambodia suggest that remittances allow households to spend more on educating their children. But this is only the case for households without emigrants. Having an emigrant in the household is associated with lower educational expenditures, canceling out the positive effect of remittances. This may reflect that children in emigrant households have to take on more housework or seek work outside the household to replace the emigrant’s labour. The prospect of future emigration could also be influencing education attendance rates. As further evidence of this phenomenon, the stated intention to emigrate by young people, both boys and girls, is higher for those that are not attending school (Figure 1.7). This dynamic is likely driven by low returns to education obtained in Cambodia in the labour market both at home and in neighbouring countries.

Note: Results that are statistically significant are indicated as follows: ***: 99%, **: 95%, *: 90%

Source: Authors’ own work based on IPPMD data.

Education policies and programmes can decrease emigration that is motivated by a desire to pay for schooling. One of the strategic goals of Cambodia’s educational policy 2014-2018 is to ensure equity in access to education. Programmes such as scholarships, school meal programmes, and the distribution of textbooks and food aim to increase school enrolment rates, especially by poor and vulnerable children. As these programmes rarely involve financial support (e.g. scholarships) and are of fairly limited coverage, the analysis finds they have little influence on people’s decisions to emigrate, however.

Investment is not being boosted by migration

Despite the large amounts of remittances flowing into Cambodia, the research finds that these funds are not being invested productively (other than in education). This is a major missed opportunity for a country that is rebuilding much of its capital stock. Similarly, return migration does not seem to boost investments either: households with a return migrant spend less on agriculture assets and are less likely to run a business than households without a return migrant. Policies to support and enable households to channel remittances towards productive use, and measures that stimulate investments by return migrants, would not only benefit the household, but also the entire country’s development.

Do sectoral policies explain this low investment rate for remittances? Financial inclusion – e.g. having a bank account – is key for channelling remittances towards productive investment; it also affects the amount of remittances received and encourages them to be transferred through formal channels. Yet, bank use is very low in Cambodia, meaning that many current and future remittance receivers do not possess a bank account. Furthermore, participation in financial training programmes is very low among migrant and non-migrant households alike, despite non-government and government initiatives to implement them. There is scope to expand the access to bank accounts and financial training programmes among households in order to encourage more remittances to be sent through formal channels and to enable households to make productive investments.

A more coherent policy agenda can unlock the development potential of migration

The report argues that migration, through the dimensions analysed in the IPPMD study – emigration, remittances and return migration – can contribute to Cambodia’s economic and social development. However, this development potential does not seem to be being fully realised.

To harness the development impact of migration, the country requires a more coherent policy framework. Cambodia has recently begun to formulate policies on migration – for example, policies on labour migration aim to improve the management of overseas employment services and protect Cambodian workers abroad (MOLVT, 2014). Yet, many other line ministries often overlook the effects migration can have on their areas of responsibility – be it the labour market, agriculture, education, or investment and financial services – as well as the effects of their policies on migration. This report calls for taking into account migration when designing policies for different sectors and national development plans for Cambodia.

The following sections provide policy recommendations for each sector studied in the IPPMD project in Cambodia. Policy recommendations across different sectors and different dimensions of migration stemming from the ten-country study are specified in the IPPMD comparative report (OECD, 2017).

Integrate migration and development into labour market policies

The Cambodian labour market is losing its low-skilled workers to emigration, especially from the agricultural sector, which is facing labour shortages. Better employment opportunities and higher wages in other countries are attracting many people from Cambodia. The IPPMD survey found government employment agencies and vocational training programmes were having limited impact on migration decisions, most probably because of their low take-up ratio and patchy coverage. This suggests the need to:

-

Widen the activities of employment agencies to reach out to both current emigrants abroad and migrants who have returned to ensure they have information on and access to formal wage jobs. Building closer connections between the employment agencies and the private sector will be important for achieving this.

-

Refine vocational training programmes to better target and match demand with supply. Mapping labour shortages and strengthening co-ordination mechanisms with the private sector are important steps. Training programmes can also be targeted at return migrants, to help them reintegrate into the labour market.

Leverage migration for agricultural development

The Cambodian Government has placed agriculture front and centre in its 2014-2018 National Strategic Development Plan (MOP, 2014). With agriculture continuing to play a substantial role in Cambodia, it is paramount that the country ensures that migration helps, rather than harms, the sector. Yet the IPPMD data show that migration has little positive effect on the sector in Cambodia. Emigration has not changed the use of household agricultural labour in emigrant households. Unlike in other IPPMD partner countries, where emigration from agricultural households is revitalising the rural labour market through the move to hire in farm workers, in Cambodia emigrant households are even less likely than those without emigrants to hire in external farm labour. This highlights a missed opportunity to revitalise the sector’s labour market. Migration has also not led to investment in the sector. Remittances and resources brought home by return migrants do not seem to be invested in agricultural assets or in diversifying farming activities. In fact, government policies, particularly those related to agricultural subsidies, seem to be encouraging migration. Recommendations for policy include the following:

-

Ensure that agricultural households can replace labour lost to emigration by ensuring better coverage by labour market institutions in rural areas. Without such institutions, the agricultural sector, food security and poverty could all deteriorate further in areas where emigration rates are high.

-

Make it easier for remittances to be channelled towards productive investment, by ensuring money transfer operators are present and affordable in rural areas, providing households with sufficient training in investment and financial skills and putting in place adequate infrastructure that make it attractive to invest in rural areas. Bottlenecks that limit investments in the agricultural sector result in a lost opportunity to harness the potential of remittances and return migration for development in the sector.

-

Make agricultural subsidies conditional on subsequent yields rather than providing them in advance. This should avoid stimulating more emigration while also maintaining the link with increased remittances. The analysis of Cambodia’s agricultural subsidy programmes suggests that if they are not contingent on some level of output or outcome, or do not provide a non-transferable asset, such as land, they may help spur more emigration. This may run counter to the objectives of the programme if its aims are to keep farmers in the country and in the sector.

Enhance the links between migration and investment in education

The IPPMD findings point to several important linkages between migration and education in Cambodia. Remittance-receiving households spend more on education than households not receiving remittances, which indicates that remittances spur investments in human capital. At the same time, the results also show that secondary education drop-out rates are highest among boys in rural emigrant households. This may partly be driven by aspirations to emigrate to take-up low skilled jobs abroad, which in turn lowers the incentives to enrol in higher education. The positive effect of remittances on educational investments should be met with investments in education infrastructure to ensure access and quality. It is also important to ensure that young people, particularly in rural areas with high emigration rates, have the means and incentives to complete the full mandatory cycle of national education.

The type of education programmes analysed in this study does not seem to have much effect on household migration decisions. The results showed a positive association between having benefited from an education policy and receiving remittances, but such policies do not seem to affect emigration decisions. One potential explanation behind the weak link is that the programmes are highly based on in-kind support and of fairly limited coverage. Recommendations for policy include the following:

-

Increase investments in education infrastructure to ensure quality and access to meet the increasing demand for education driven by remittances.

-

Expand cash and in-kind distribution programmes in areas with high emigration rates to make sure that young people have the means to complete secondary education.

Strengthen the links between migration, investment, financial services and development

The IPPMD findings show an insignificant or sometimes even negative relationship between remittances, return migration and investments. Remittances are not associated – either positively or negatively – with business or real estate ownership. In a context in which migration is largely a livelihood coping strategy, remittances are predominantly used for buying food, health care and repaying debts; they may not be large enough to be used for productive investment. Receiving remittances is also not associated with investment in other productive assets, such as non-agricultural land or real estate. Return migration is found to be negatively associated with business ownership.

On the other hand, it does seem as if owning a bank account has positive effects on remittance patterns. As well as being linked to greater amounts of remittances, having a bank account reduces the transfer of remittances through informal channels. Yet, bank use is very low in Cambodia, and many current and future remittance receivers lack access to formal bank accounts. Policies to increase access to bank accounts could hence stimulate the sending of remittances and channel remittances into formal financial institutions. This suggests the need to:

-

Promote entrepreneurship through the different phases of developing, starting and managing a business to help return migrants and remittance-receiving households to overcome investment barriers and stimulate more productive remittance investments.

-

Implement a national financial education programme to enhance the financial literacy of Cambodians in general and migrants and their families in particular to encourage more remittances to be channelled towards productive investments.

-

Reduce the number of Cambodians who are unbanked by expanding the presence of financial institutions and deliver financial services beyond more developed and urbanised areas to stimulate more formally sent remittances.

Roadmap of the report

The next chapter discusses how migration has evolved in Cambodia and reviews the existing research on the links between migration and development. It also briefly draws current policy context and institutional frameworks related to migration. Chapter 3 explains the implementation of fieldwork and the analytical approaches used for the empirical research. It also illustrates broad findings of the IPPMD survey on emigration, remittances and return migration patterns. Chapter 4 discusses how the three dimensions of migration affect four key sectors in Cambodia: the labour market, agriculture, education, and investment and financial services. How the policies in these sectors can influence migration outcomes are explored in Chapter 5.

References

MOP (2014), “2014-2018 National Strategic Development Plan,” Cambodian Ministry of Planning, Phnom Penh, http://www.mop.gov.kh/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=XOvSGmpI4tE%3d&tabid=216&mid=705.

MOLVT (2014), Policy on Labour Migration for Cambodia, Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training, Phnom Penh.

OECD (2017), Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265615-en.

UN (2015), Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, United Nations, New York, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2051AAAA_Outcome.pdf.

UN DESA (2015), International Migration Stock: The 2015 Revision, (database), United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml.

World Bank (2016), “Annual Remittances Data (inflows)”, World Bank Migration and Remittance data, database, The World Bank, Washington DC, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/migrationremittancesdiasporaissues/brief/migration-remittances-data, accessed January 12, 2017.