Chapter 1. Policy context for employment and skills in the Philippines

This chapter provides an overview of the key macro-level trends in the Philippines as well as an overview of the key departments and organisations managing employment and skills programmes. The Philippines recovered quickly following the global economic crisis. During the period between 2008-14, average GDP growth was 5.4%, outperforming both the OECD average and a number of ASEAN peers including Brunei Darussalam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. Responsibilities for labour market policies and vocational education and training are relatively decentralised in the Philippines. Local government units play an important role in linking people to jobs and developing training programmes with employers.

Economic and labour market trends in the Philippines

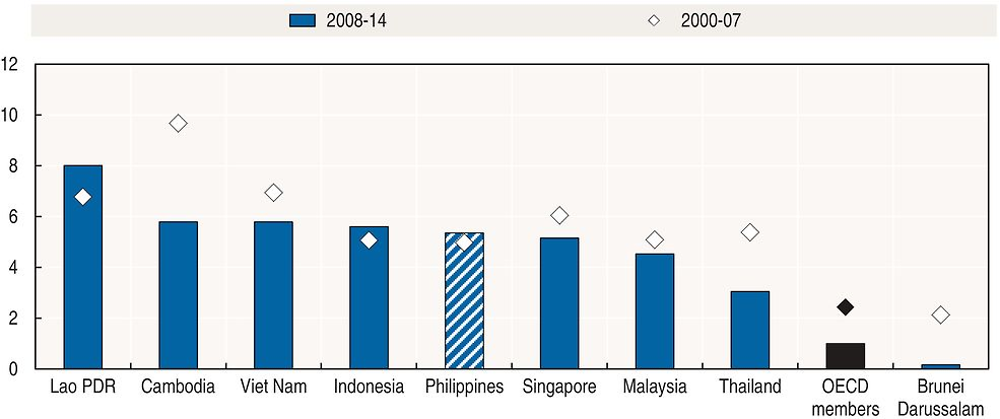

While the economy of the Philippines has been growing at a relatively fast pace over the last 15 years, it has suffered significant fluctuations. The Philippines grew by an average annual rate of 5% between 2000 and 2007, which was the second lowest rate amongst ASEAN countries, ranking above only Brunei-Darussalam. However, the economy recovered quickly following the global economic crisis. During the period between 2008 and 2014, the average annual GDP growth rate was 5.4%, outperforming both the OECD average and a number of local ASEAN peers including Brunei Darussalam, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore (see Figure 1.1).

Source: World Bank, International Comparison Program database.

As a result, GDP per capita in the Philippines also grew at a faster pace during the period between 2008 and 2014 (3.7% average annual growth rate) than between 2000 and 2007 (3.0%). Despite this recent acceleration, the level of GDP per capita in the Philippines in 2014 was lower than in most ASEAN countries, with the exception of Viet Nam, Lao PDR and Cambodia. There is a need to stimulate investment in job-creating sectors in order to provide employment opportunities for the growing working-age population. The growth model of the Philippines has been accompanied by insufficient development of domestic manufacturing and services (OECD, 2016). As a result, the economy is struggling to develop and adopt certain technologies that would enable the Philippines to become a high-income country.

Demographics

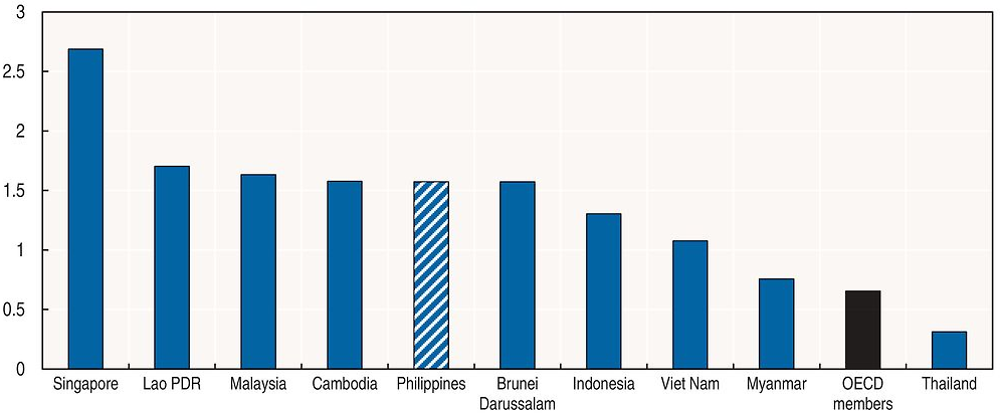

In 2015, the population of the Philippines was estimated to be 101.5 million (PSA, 2015). Between 2005 and 2015, the country’s average annual population growth rate was 1.6%, which was higher than in most ASEAN countries and in OECD countries as a whole, but lower than in Singapore, Lao PDR, Malaysia and Cambodia (see Figure 1.2).

Source: World Bank database.

The Philippines has a much younger population than the average population across OECD countries. In 2015, the share of the population aged 15 or less was 33.4% in the Philippines, compared to 18.0% on average in the OECD. Conversely, only 4.8% of the population in the Philippines was aged 65 or more in 2015, while this proportion was 16.3% in the OECD. This particular age distribution has several consequences on the Philippines’ economy and labour market. First, it should be noted that share of people of the working age (15-64) population relative to the total population is currently lower in the Philippines (63.4%) than in the OECD as a whole (65.6%), which means that the pool of potential workers on which the economy of the Philippines can count is somewhat smaller. Moreover, in the short term, the burden that falls on the working age population to educate the younger population is heavier in the Philippines than it is in most OECD countries.

But the age structure of the population in the Philippines could change rapidly, depending on how the fertility rate will evolve in the coming years. If the fertility rate (3.0 children per woman in 2014) decreases, the country could move towards an optimal demographic situation, also referred to as a “demographic sweet spot”, characterised by an increase in the proportion of individuals in working age and a decline in the ratio of dependents to the working age population. Whether this will translate into a “demographic dividend” in terms of accelerated economic growth and better job opportunities for the population will depend on a number of factors, including the improvement of health of population, level of skills of the population, the dynamism of the economy, and the quality of the match between the supply of skills and the demand for skills (Bloom, Canning, and Sevilla, 2003).

Alleviating poverty also remains a persistent challenge in the Philippines. In 2012, 13.1% of the population was living on less than $1.90 a day (at 2011 international prices), down from 18.4% in 2000 (World Bank, 2016a), and 38.3% of the urban population lived in slums in 2014, down from 47.2% in 2000 (UN, 2016). Inequalities also remain high, with 33.4% of total income being held by the richest 10% compared to only 2.45% by the poorest 10% in 2012 (World Bank, 2016b). A significant proportion of Filipino workers face working conditions that do not enable them to get out of poverty, due in particular to earnings that are not sufficient to meet their basic needs (ILO, 2012). Between 2001 and 2010, average real wages have tended to decline, indicating that earnings have not caught up with the increase in prices, and the share of low paid workers has remained unchanged.

Labour market outcomes

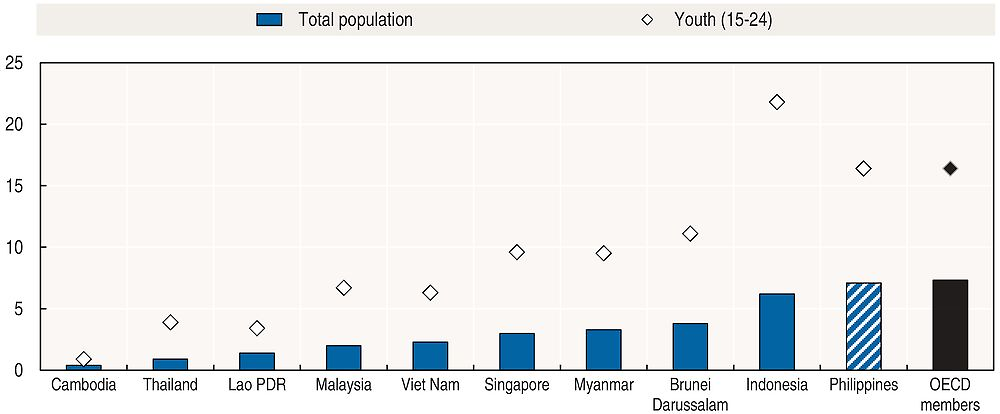

In 2015, the labour force was 42.1 million people, resulting in a labour force participation rate of 63.3%, which is lower than in many neighbouring countries. Approximately 39.8 million were employed, of which 54.5% were working in the services sector, 29.6% in the agriculture sector and 16.0% in the industry sector. When looking at sub-sectors, agriculture, hunting and forestry accounted for 26.2% of all employment, while 19.1% of workers were employed in wholesale and retail trade. In terms of major occupational groups, labourers and unskilled workers made up 31.5% of total employment, followed by officials of the government and managers (15.7%), agriculture workers (13.5%) and service workers (12.9%). In 2014, the Philippines registered the highest unemployment rate among ASEAN countries at 7.1%, and the second highest youth unemployment rate at 16.4% (Figure 1.3).

Source: World Bank database.

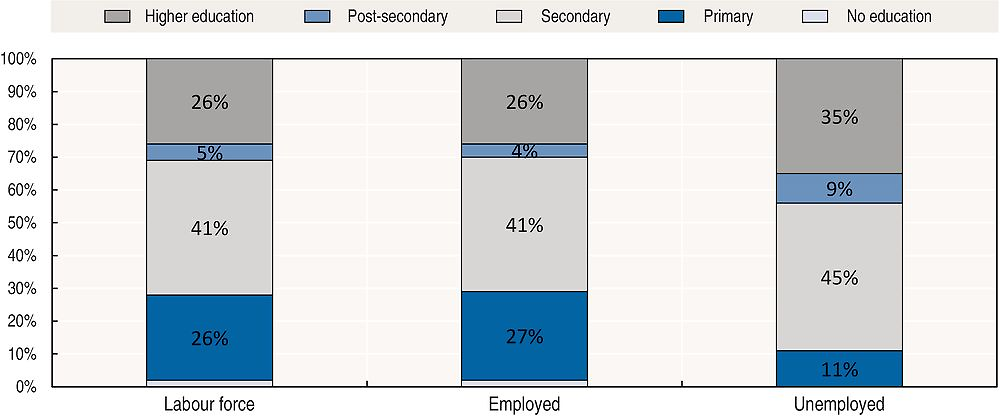

The reality of employment conditions in the Philippines is not easy to grasp. Significant variation can be observed in the labour market outcomes of various categories of the population, most notably according to gender and education levels. For example, unemployment tends to affect disproportionately youth and the well-educated. Figure 1.4 shows that individuals with a higher education qualification account for 35% of the unemployed population, but only 26% of the labour force. Conversely, only 11% of those that are unemployed have low level of education (primary education or no education), when this category of the population accounts for 29% of the labour force. The prevalence of “educated unemployed” has been well documented (ILO, 2012) and may indicate possible mismatch in the labour market in the Philippines. In particular, the availability of jobs requiring a high level of skills may be insufficient and the education system may not be providing young people with the skills demanded by employers.

Source: Labour Force Survey, Philippine Statistics Authority.

Given that unemployment figures exclude individuals who left the labour force because they were unable to find work, it is useful to look at the rate of labour market participation. Table 1.1 shows that the labour participation rate is much higher for male (77%) than for female (50%). As the level of education increases, this gender gap tends to become smaller and labour force participation generally increases. Yet as for unemployment, it can be noted that the average participation rate for individuals with advanced education is significantly lower than for individuals with an intermediate education level.

Unemployment figures can also hide the fact that a relatively large share of those employed are in fact in a situation of underemployment, which means that they are working less than 40 hours per week but would prefer to work more (OECD, 2016). The self-employed and those that are employed by private households or work in family-owned farms or businesses tend to be disproportionately affected by underemployment, as are those with lower levels of educational attainment.

The Philippines also faces major challenges in terms of the high incidence of informal and low quality employment in the labour market. In 2008, it was estimated that 10.4 million people were working informally, and in 2014, 38.6% of workers were in a vulnerable form of employment (self-employed without any paid employee, unpaid family workers or employed in own family-operated farm or business) (ILO, 2015). These workers are less likely to benefit from social protection and formal work arrangements, and are therefore more vulnerable to economic shocks. The labour market inclusion of women is also a pressing issue in the Philippines: of the country’s 24.5 million people aged 15 or older that were not in the labour force in 2015, seven out of ten were women.

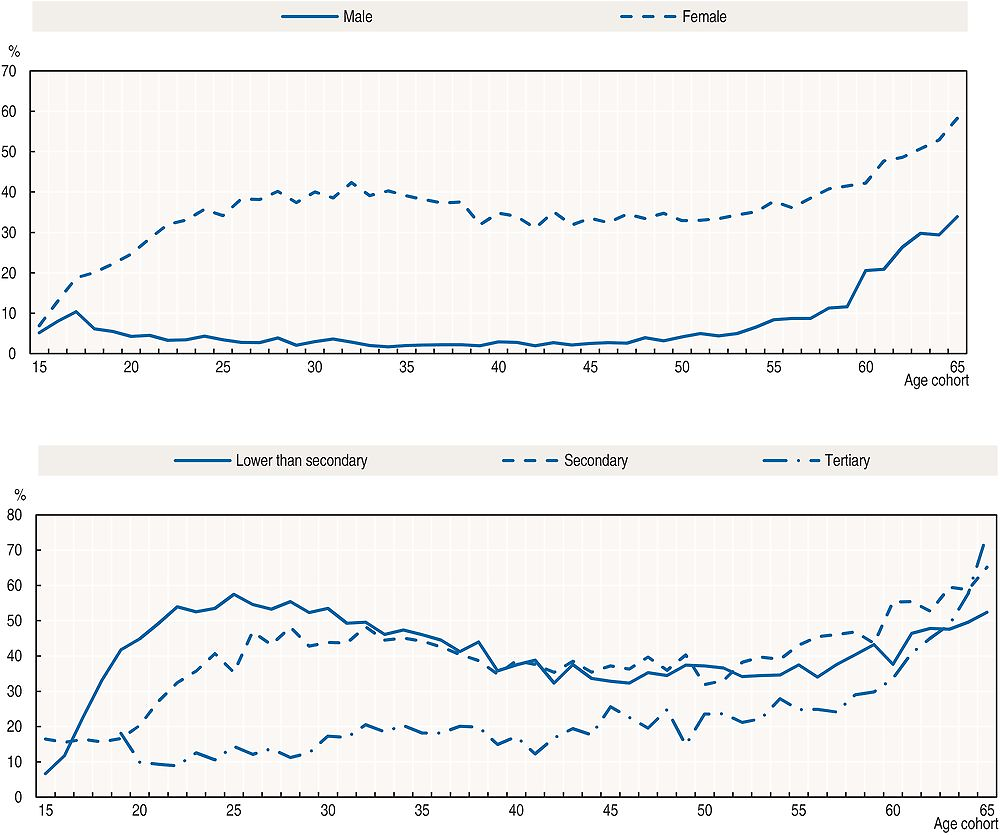

In the Philippines it takes youth longer than it should for them to find work after they leave school. Based on findings from an ADB survey of 500 households in Metro Manila and Cebu City in 2008, only 20% of high school graduates found a job within the first year of leaving school and only 60% of high school graduates were in employment eight years after leaving school. In contrast, 75% of college graduates found a job within the first year of leaving school. As a result of this slow school to work transition, one in four young persons was neither in employment, education, or training (NEET) in 2013, a rate second in Southeast Asia only to Indonesia’s. This rate is higher for young women than for young men – one in three – because young women are more likely to withdraw from the labour market entirely (Figure 1.5a). Young women with low education attainment are most at risk in part due to earlier child bearing and child rearing than women with college education (Figure 1.5b). The rate is also highest among youth from low income families, as they tend to be less educated, do not have quality social contacts, and do not have the life skills required to find decent long-term employment (ADB, 2016 forthcoming).

Source: Labour Force Survey, 2013, October round. ADB staff estimates.

Skills in the Philippines

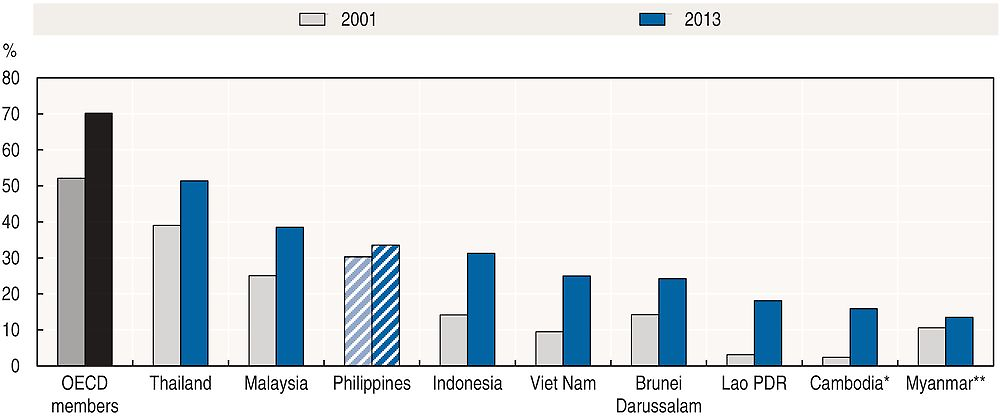

In terms of educational outcomes, the Philippines is regionally successful but has yet to reach the standards of more developed countries. Educational attainment of the Filipino population has steadily increased in recent decades (ILO, 2012). Figure 1.6 shows that the Filipino rate of enrolment in tertiary education was higher than in most ASEAN countries in 2013, with the exception of Thailand and Malaysia. Yet it was still only around half of the average rate in OECD countries. It should also be noted that the growth in tertiary education enrolment between 2001 and 2013 has been relatively weak in the Philippines compared to other ASEAN countries as well as OECD countries.

* Data for Cambodia is for 2001 and 2011.

** Data for Myanmar is for 2001 and 2012.

Source: World Bank database.

A survey undertaken by the Department of Labour and Employment (DOLE) has shown that in 2012, 36% of firms considered that the lack of pertinent skills was the main reason why they found it hard to fill vacancies (PSA, 2016). Similarly, according to data from the World Bank Enterprise Survey, 10.1% of private sector firms identified an inadequately educated workforce as a major constraint for growth in 2015, up from 7.8% in 2009 (World Bank, 2015). Results from this survey also show that socio-behavioural skills, such as managerial, leadership, interpersonal and communication skills, are those that firms consider to be more difficult to find in potential employees.

In February 2001, the Philippine Congressional Commission on Labor issued its Report and Recommendations titled Human Capital in the Emerging Economy. In the preamble to the Resolution creating the Commission, it was noted that “the workers are the lifeline of the economy” and “the largest component of income of most Filipino individuals and families is a return for their skills and knowledge.” The Report and Recommendations provides a rich context for the national policy settings discussed in the following section. In its Report and Recommendations, the Commission identified key challenges in the labour market, including:

-

The aggregate share of labour in gross domestic product remained stagnant at 25% over the last 20 years, indicating that labour had not benefited from past economic growth;

-

Protective legislation and collective action of workers were countervailing measures to protect them against abuse;

-

The inability of the industrial sector to absorb more workers was traced to a structure of production that had limited employment-creating potential;

-

The average productivity of labour stagnated during 1987-1999. Over 12 years, the increase was a mere 6 per cent;

-

The lack of employment opportunities in the country and the differential in pay between local and foreign employment induced Filipino workers to seek jobs overseas. (Congress of the Philippines, 2001).

To raise the quality of the workforce, the Report and Recommendations advocated several measures (Congress of the Philippines, 2001), including increasing investments in quality basic education; targeting public investments in higher education and advanced scientific and technical research; reducing public subsidies to state universities and colleges via phase down or devolution to local government units or the private sector; expanding opportunities for education through well-designed educational loan programmes for qualified students from low-income families; strengthening co-ordination between the public and private sectors in providing vocational and technical training to ensure better match of skills with industry demand and to remove costly duplication of government- and privately-provided training; and devolving vocational and technical training to local government units and the private sector to enable TESDA to concentrate on skills certification, standard setting and equivalency, timely development of training curricula, and the building of partnerships between training centres and industry.

Governance of employment, skills, and economic development policies in the Philippines

The Philippine Constitution mandates the State to promote full employment and equal employment opportunities, raise the standard of living, and improve quality of life for all. In the Philippines, the Department of Labour and Employment (DOLE) acts as a policy-advisory and co-ordinating body of the executive branch of the Philippine government, and is mandated to formulate and implement policies and programmes pertinent to the national labour and employment agenda. DOLE’s mission is to ensure that every Filipino worker attains full, decent and productive employment by promoting gainful employment opportunities, developing human resources, protecting workers and promoting their welfare, and maintaining industrial peace.

DOLE has 18 regional offices,1 83 field offices with four (4) satellite offices, 38 overseas posts, 5 bureau, 7 staff services, and 11 agencies attached to it for policy and programme supervision and/or co-ordination. To facilitate policy development and programme implementation, DOLE agencies are sub-divided into clusters including: Employability of Workers and Competitiveness of Enterprises Cluster, Worker’s Welfare and Social Protection Cluster, Labor Relations and Social Dialogue Cluster, and the Internal Affairs Cluster. The new DOLE clustering has the employment cluster further classified into local and overseas employment clusters.

The management and accountability structures between employment services offices at the national, regional and local level

Employment services in the Philippines are run by both private and public operators. Private entities are divided into fee-charging providers, namely Private Employment Agencies (PEAs), and non-fee charging providers, including non-governmental organisations (NGO) and school-based employment services. With some exceptions, PEAs are not allowed to charge any fees for recruitment. These agencies often provide only some of the core functions of an employment service and have, when profit-oriented, a distinct clientele that they recruit, service and place.

The bulk of the country’s employment services, however, consist of the publicly operated facilities called Public Employment Service Offices (PESOs). These can be found in strategic areas for employment in selected provinces, cities, and municipalities in the country. According to the PESO Act of 1999, PESOs have a mandate to serve as a non-fee charging multi-employment service facility with the aim of achieving full employment and equality of employment opportunities for all. For this purpose, it is responsible for strengthening and expanding the employment facilitation services of the government, particularly at the local level. PESOs are community-based and are usually maintained by local government units, NGOs or community-based organisations, and state universities and colleges.

The national employment service network is convened by the national PESO Managers Association of the Philippines (PESOMAP). As part of this network, the Bureau of Local Employment (BLE) links PESOs to the DOLE central office and the regional offices of the DOLE for co-ordination and technical supervision. A fully functioning PESO has the following four core functions, which may be complemented on a case-by-case basis by additional functions depending on local context and requirements: Job search assistance and placement services, registration, counselling, and linking with training providers; Labour market information services; administration of labour market programmes; and regulatory services as the authorised agency to ensure compliance with all legal obligations. The PESOs are initially classified into three categories:

-

Category 1: Established PESO – in existence by virtue of a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with the DOLE;

-

Category 2: Operational PESO – in existence and performing at least one core function on a daily basis;

-

Category 3: Institutionalised PESO – in existence by virtue of a Sanggunian Resolution or an Ordinance provided with regular plantilla positions and appropriate funds.

Currently, local government units (LGUs) are responsible for financing human resources, operations, and the maintenance of PESOs within their jurisdiction. The DOLE supports and facilitates PESO operations through its regional offices. It monitors and supervises the performance and programmes of PESOs, while providing technical assistance including personnel training, report generation, and inter-agency co-ordination. While the DOLE is the primary labour and employment agency under the executive branch of the Philippine government, other agencies collaborate to deliver its services. The DOLE consults and works with the agencies under the Human Development and Poverty Reduction Cluster of the Cabinet. The cluster focuses on improving the overall quality of life for Filipinos and translating the gains of good governance into direct, immediate, and substantial benefits to empower the poor and marginalised segments of society.

The latest records show that 1 925 PESOs are currently operating in the country, including 413 institutionalised PESOs. In 2015, the number of qualified jobseekers referred for placement reached 9.41 million, an increase of 30.6% compared to 2010. In 2015 alone, almost 1.7 million qualified jobseekers were referred for placement.

Recent reforms to public employment services in the Philippines

The functionalities, operations, and partnerships of PESOs with the DOLE and other institutions were strengthened in late 2015 through an amendatory act to the PESO Act of 1999. The new law mandates that PESOs shall be established in all provinces, cities, and municipalities and operated and maintained by LGUs. Regional offices of the DOLE will provide co-ordination and technical supervision to the PESOs, while the central office of the DOLE will organise and facilitate the national public employment service network. Under the new law, the PESO shall have the following functions (Republic Act No. 10691):

-

Encourage employers to submit a list of job vacancies in their respective establishments to the PESO on a regular basis in order to facilitate the exchange of labour market information between job seekers and employers by providing employment information services to job seekers, both for local and overseas employment, and recruitment assistance to employers;

-

Develop and administer testing and evaluation instruments for effective job selection, training and counselling;

-

Provide persons with entrepreneurship qualities with access to the various livelihood and self-employment programmes offered by both government and nongovernmental organisations at the provincial, city, municipal and barangay levels;

-

Undertake employability enhancement training or seminars for job seekers, as well as those who would like to change career or enhance their employability;

-

Provide employment or occupational counselling, career guidance, mass motivation and values development activities;

-

Conduct pre-employment counselling and orientation to prospective local and, most especially, overseas workers;

-

Provide reintegration assistance services to returning Filipino migrant workers;

-

Prepare and submit an annual employment plan and budget to the local sanggunian including other regular funding sources and budgetary support of the PESO; and

-

Perform such functions as to fully carry out the objectives of the new law.

In addition to these functions, every PESO must now undertake activities to transform the PESOs into a modern public employment service intermediary that provides multi-dimensional employment facilitation services. (Republic Act No. 10691). The LGUs must establish the PESO in co-ordination with the DOLE. It shall be the responsibility of the DOLE to (Republic Act No. 10691):

-

Provide technical supervision, co-ordination and capacity-building to the PESO;

-

Establish and maintain a computerised human resource and job registry to facilitate the provision and packaging of employment assistance to PESO clients and the establishment of intra- and inter¬regional job clearance systems as part of the overall employment network;

-

Provide technical assistance and allied support services to the PESO including, but not limited to, the training of PESO personnel to meet various employment facilitation functions;

-

Set standards for the establishment and operation of the PESO, and qualification standards for the PESO personnel;

-

Extend other packages of employment services to the LGU or NGO concerned, including the conduct of job fairs, career development seminars, and other activities; and

-

Monitor, assess, and evaluate the performance of the PESOs, including the job placement offices.

JobStart Philippines Act

Another key piece of legislation is the JobStart Philippines Act which was signed into law on June 29, 2016 with the aim of promoting full employment, equal employment opportunities for all, and full protection to labour. In congruence with the International Labour Organization’s Decent Work Agenda and Convention 88, the new law seeks to promote the PESO as the primary institution at the local level for implementing active labour market programmes such as job search assistance, training and placement for the unemployed, particularly young jobseekers.

The Act aims to shorten the transition from school to work for young people and increase their chances of integrating into productive employment. The programme also seeks to further improve the delivery of employment facilitation services for PESOs. Among the key supply-side intermediation approaches set out in the new law are:

-

JobStart life skills training: 10-day training courses to holistically develop the behaviours, attitudes and values of trainees, enable them to plan career paths and cope with the challenges of everyday life and work;

-

JobStart technical training: technology-based, theoretical instruction for up to three months through lectures and hands-on exercises in laboratory or workshop of provider; and

-

JobStart internships: practical work-based learning for trainees in regular work environment with employers for periods of up to 3 months.

The JobStart Programme is open to participants aged 18 to 24 years old, high school graduates, unemployed, those neither studying nor undergoing training at the time of registration and those with less than one year or no work experience. The Programme shall include full employment facilitation services such as registration, client assessment, life skills training with one-on-one career coaching, technical training, job matching, and referrals to employers either for further technical training, internship, or for decent employment. An employer shall be allowed to employ JobStart trainees up to a maximum of 20% of its total workforce, for a period not longer than three months or 600 hours, with a commitment to pay at least 75% of the applicable daily minimum wage.

Participating employers shall receive an amount to be determined by the DOLE per month per trainee to cover administration costs for managing the trainee. The employer shall design and implement the training plan; submit monitoring and evaluation reports or other information on the trainee’s performance as may be required by the DOLE or the PESO; submit invoices to the PESO for reimbursement or liquidation of expenses of training costs, internship stipend, and other administrative costs; and notify the PESO and JobStart Unit of a trainee’s breach of contract or misconduct in the training premises (if any) prior to its decision to suspend or terminate the training.

The JobStart Philippines Act defines the duties and responsibilities of JobStart trainees and participating establishments, including the roles of LGUs, PESOs, the DOLE, the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA), the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). The LGUs, through the PESOs, shall serve as the conduit of the DOLE to implement the programme at the local level. As the implementing agency of the programme, the DOLE shall formulate the rules and regulations to implement the provisions of the Act in co-ordination with the appropriate agencies.

The availability of labour market information and data

The newly reorganised Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) is the prime government agency that is responsible for co-ordinating government-wide programmes and governing the production of official statistics, general-purpose statistics, and civil registration services. The PSA is primarily responsible for all national censuses and surveys, sectoral statistics, the consolidation of selected administrative recording systems and the compilation of national accounts. The PSA conducts the Labour Force Survey, which is conducted four times per year and serves as the main source of key employment indicators in the country.

The DOLE, through its Bureau of Local Employment, maintains a labour market information (LMI) system that primarily utilises administrative data. It has a large LMI system that consolidates information from a variety of databases generated by its organic units and attached agencies. The Bureau of Local Employment serves as the consolidating entity for LMI in the country. It also administers PhilJobNet (www.philjobnet.gov.ph), the central LMI and career and occupational information portal of the Philippine government.

PhilJobNet is a vehicle for jobseekers to find career opportunities posted by partner employers, free of charge. Employers, in turn, are provided access to the profiles of applicants and prospective employees. The site can be used as a source of information on in-demand occupations and emerging occupations in the market.

The Skills Registry System (SRS), a subsystem of the PhilJobNet, is another source of LMI that houses a “live” registry of skills. It serves as an IT-based database for PESOs to facilitate the referral and placement of jobseekers, given the job vacancies available at the community level. The SRS establishes a national registry of skills and provides information on the demand for labour as employers are requested to post their vacant positions on the registry. The SRS addresses administrative data coming from the public employment services in ’barangay’, the Philippines’ smallest geographical unit.

Job Search Kiosks were deployed in the PESOs, high schools, universities and colleges, and malls nationwide to bring timely and relevant LMI closer to jobseekers, particularly in areas with limited or no internet connection. The kiosks are stand-alone channels of the PhilJobNet that can be accessed even without internet connection. A final channel for LMI dissemination is the inter-agency Career Guidance Advocacy Program (CGAP) that features 108 networks of career guidance advocates, which provide services to almost 5 000 members. The programme is a response to the undersupply of registered guidance counsellors whose role is to provide guidance to youth in making career decisions. The programme trains career advocates on LMI and basic employment coaching techniques. The programme targets youth primarily by communicating in slang and using social media using the theme of “Follow the guide, tag a career, like the future!”

The management of training and skills development policies

The education system in the Philippines, which comprises formal and non-formal education, is closely related to the American mode of education. In 2013, the Enhanced Basic Education Curriculum reform (Republic Act No. 10533) standardised the number of years and standards of Kindergarten to Grade 12 (K to 12) basic education. Before then, basic education only consisted of six years of elementary education and four years of secondary education. The new curriculum includes mandatory kindergarten and two additional years of upper secondary school (senior high school). Tertiary education in colleges and universities complement the Philippines’ formal education system.

Non-formal education includes educational opportunities, even outside school premises, that facilitate the achievement of specific learning objectives for particular clientele, especially young people who are no longer in school or illiterate adults who cannot benefit from formal education. For example, functional literacy programmes for non-literate and semi-literate adults aim to integrate basic literacy with livelihood skills training. In the Philippines, the Department of Education (DepEd) is responsible for basic education, while the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) is in charge of Higher Education, including tertiary education in community colleges, universities and specialised colleges.

The management and accountability structures of Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Technical vocational education and training (TVET) is managed by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA). This government agency, which was formed through the 1994 TESDA Act, integrates the functions of the former National Manpower and Youth Council (NMYC), the Bureau of Technical-Vocational Education of the Department of Education, Culture and Sports (BTVE-DECS) and the Office of Apprenticeship of the DOLE.

Under the jurisdiction of the DOLE, the TESDA is mandated to provide relevant, accessible, high quality and efficient technical education and skills development programmes in accordance with the Philippine development goals and priorities. Given its mandate, TESDA provides direction, policies, programmes and standards towards quality technical education and skills development. Specifically, TESDA is responsible for:

-

Integrating, co-ordinating and monitoring skills development programmes;

-

Developing an accreditation system for institutions involved in middle-level manpower development;

-

Funding programmes and projects for technical education and skills development; and

The DOLE provides TESDA with policy and programme co-ordination and general supervision (Office of the President of the Philippines, 1987). At present, TVET aims to provide education and training opportunities to prepare students and other clients for employment. It also aims to address the skills training requirements of those who are already in the labour market and need to upgrade or develop new competences to enhance their employability skills and improve productivity. The potential clientele of TVET includes high school graduates, secondary school leavers, college undergraduates and graduates who want to acquire competences in different occupational fields. Other potential clientele of TVET include unemployed persons who are actively looking for work, including displaced workers who lost their jobs because of the closure of businesses. Returning overseas Filipino workers are also potential clients of TVET.

There are four basic modes of training delivery:

-

School-based: Formal delivery of TVET programmes of at least a year but not exceeding three years;

-

Centre-based: Provision of short non-formal training undertaken in the TESDA Regional and Provincial Training Centres;

-

Community-based: Training programmes specifically designed to meet the need for skills training in local communities to facilitate self-employment; and

-

Enterprise-based: Training programmes like apprenticeships, traineeships and dual training that are carried out within firms/industries.

Training and skills development of the Filipino workforce is mostly provided by private TVET institutions. Based on 2010 data, there are currently around 4 500 TVET providers in the country, 62% of which are private and 38% public. The public TVET providers include 121 TESDA Technology Institutes, which includes 57 schools, 15 Regional Training Centres, 45 Provincial Training Centres and 4 Specialised Training Centres. Other public TVET providers include State Universities and Colleges and local colleges, who offer non-degree programmes, The Department of Education supervises schools, LGUs, and other government agencies.

The Ladderized Education Act (Republic Act No. 10647) was passed in 2014, which aims to institutionalise the “ladderized” interface between TVET and higher education to open the pathways of opportunities for the career and educational progression of students and workers. “Ladderized” education refers to the harmonisation of all education and training mechanisms that allow students and workers to progress between TVET and higher education programmes, or vice-versa. It aims to open opportunities for career and educational advancement for students and workers, to create a seamless and borderless system of education, and to empower students and workers to exercise options or to choose when to enter and exit in the educational ladder. These reforms also aimed to uphold the academic standards, equity principles, promptness and consistency of the applications/admissions and equivalency policies of higher education institutions.

Apprenticeship programmes

Apprenticeship programmes are regulated by TESDA. Under the Labor Code of the Philippines, “apprenticeship” means practical on-the-job training supplemented by related theoretical instruction. An “apprenticeable occupation” refers to any trade, form of employment or occupation which requires more than three (3) months of practical on-the-job training supplemented by related theoretical instruction. The “apprenticeship agreement” is an employment contract wherein the employer is obliged to train the apprentice and the apprentice in turn accepts the terms of training. To qualify as an apprentice, a person shall:

-

Be at least fourteen (14) years of age;

-

Possess vocational aptitude and capacity for appropriate tests; and

-

Possess the ability to comprehend and follow oral and written instructions.

Trade and industry associations may recommend to the Secretary of Labor appropriate educational requirements for different occupations. Apprenticeship agreements, including the wage rates of apprentices, shall conform to the rules issued by the TESDA. The period of apprenticeship shall not exceed six months. Apprenticeship agreements outline that wage rates must be at least 75% of the minimum wage. These agreements must be entered in accordance with standard models of apprenticeship programmes developed or approved by the TESDA.

An additional deduction from taxable income of one-half (1/2) of the value of labour training expenses incurred for developing the productivity and efficiency of apprentices shall be granted to the person or enterprise organising an apprenticeship programme. However, this is dependent on the recognition of the programme by TESDA and the deduction must not exceed 10% of the direct labour wage. Similarly, the person or enterprise who wishes to take advantage of this incentive must pay the apprentices the minimum wage.

Traineeships

Traineeships programmes are also regulated by the TESDA. Under the Labor Code, learners are persons hired as trainees in semi-skilled and other industrial occupations which are non-apprenticeable and include practical training on the job in a relatively short period of time (not exceed three months).

Learners may be employed when no experienced workers are available, the employment of learners is necessary to prevent curtailment of employment opportunities, and the employment does not create unfair competition in terms of labour costs or impair or lower working standards. Any employer that wishes to employ learners shall enter into a trainee agreement with them, which must include:

-

The names and addresses of the trainees;

-

The duration of the traineeship period, which shall not exceed three (3) months;

-

The wages or salary rates of the trainees which shall begin at not less than seventy-five per cent (75%) of the applicable minimum wage; and a commitment to employ the trainees as regular employees upon completion of the traineeship, if they wish. All learners who worked for the first two (2) months shall be deemed regular employees if the trainee is terminated by the employer before the end of the stipulated period through no fault of the learners.

The management of economic development policies

The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) is an independent cabinet-level agency of the Philippine government responsible for socio-economic development and planning. The mission of the NEDA is to formulate development plans, and ensure that implementation achieves the national development goals. It is also the authority in macroeconomic forecasting and policy analysis and research. It provides high-level advice to policy makers in Congress and the Executive Branch. NEDA fulfils its mandate with the help of its attached agencies: The Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA), the Philippine Statistical Research and Training Institute (PSRTI), the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), the Philippine National Volunteer Service Co-ordinating Agency (PNVSCA), the Public-Private Partnership Centre (PPP) and the Tariff Commission.

NEDA’s Philippine Development Plan 2011-2016 pursues a framework of inclusive growth, defined as a sustained high level of economic growth that generates mass employment and reduces poverty. In order to promote good governance and anticorruption, the Plan translates into specific goals, objectives, strategies, programmes and projects. In partnership with the key national government agencies, NEDA intends to pursue rapid economic growth and development, improve the quality of life for Filipinos, empower the poor and marginalised and enhance national social cohesion. NEDA’s strategic development policy framework, as indicated in the plan, focuses on improving transparency and accountability in governance, strengthening the macro-economy, boosting the competitiveness of industries, facilitating infrastructure development, strengthening the financial sector and capital mobilisation, improving access to quality social services, enhancing peace and security for development, and ensuring ecological integrity. In addition, the plan serves as a guide for policy formulation and the implementation of development programmes for the duration of the six year programme.

In 2015, the Philippine Competition Act (Republic Act No. 10667) was passed and established the primary law for the promotion and protection of the competitive market in the Philippines. It led to the creation of the Philippine Competition Commission (PCC), an independent quasi-judicial body mandated to implement the national competition policy. The main objectives of the PCC are to protect consumers, promote competitive businesses, and prevent anti-competitive behaviour.

Under the Philippine Constitution, the President supports regional development councils (RDCs) composed of local government officials, regional heads of departments and other government offices, and representatives from non-governmental organisations. This is in order to further administrative decentralisation, strengthen the autonomy of the regional units and accelerate the economic and social growth and development of the units in the region.

In April 1996, Executive Order No. 325 was issued in which outlines the following regular RDC members: a) provincial governors; b) city mayors; c) mayors of municipalities designated as provincial capitals; d) presidents of the provincial league of mayors; e) the mayors of the municipality designated as the regional centre; f) the regional directors of agencies represented in the National Economic and Development Authority Board and the regional directors of the Department of Education, the Department of Social Welfare and Development, and the Department of Trade; and g) private sector representatives who shall comprise one-fourth of the members of the fully-constituted council.

References

ADB (2016 forthcoming). “Strategy to Tackling the Slow School-to-Work Transition in the Philippines”, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

Bloom, D., D. Canning and J. Sevilla (2003), “The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change”, Santa Monica, Calif: Rand, http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=202774.

ILO (2015), “Philippine Employment Trends 2015, Accelerating inclusive growth through decent jobs”, International Labour Office, Geneva, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-manila/documents/publication/wcms_362751.pdf.

ILO (2012), “Decent work country profile: Philippines”, International Labour Office, Geneva, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---integration/documents/publication/wcms_167677.pdf.

Congress of the Philippines (2001), “Human Capital in the Emerging Economy, Report and Recommendations of the Congressional Commission on Labour”, February 2001, Philippines.

Office of the President of the Philippines (1996), [Executive Order Nos. : 301-440]. Manila : Presidential Management Staff.

Office of the President of the Philippines (1987), Supplement to the Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Manila : Government Printing Office, 83 (31), 3528-138 – 3528-139.

OECD (2016), Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2016: Enhancing Regional Ties, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/saeo-2016-en.

PSA (2016), Integrated Survey on Labor and Employment 2013/2014, Philippine Statistics Authority, PHL-PSA-ISLE-2013-v01.

PSA (2015), 2015 Philippine Statistical Yearbook, Philippine Statistics Authority, ISSN-0118-1564, https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2015%20PSY%20PDF_0.pdf.

UN (2016), Millennium Development Goals Indicators, United Nations, retrieved from http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspx.

World Bank (2015), Philippines 2015 Country Profile, Enterprise Surveys, www.enterprisesurveys.org, The World Bank.

World Bank (2016a). World databank, retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/topic/poverty?locations=PH &view=chart.

World Bank (2016b), World databank, retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/topic/poverty?end=2012& locations=PH&start=1985&view=chart.

Note

← 1. The 18th and newest DOLE regional office, the DOLE-Negros Island Region (NIR), has in its jurisdiction the provinces of Negros Oriental and Negros Occidental which were once part of Regions 6 and 7, respectively. The creation of NIR is by virtue of Executive Order No. 183 that was signed in May 2015. The Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), the 198th administrative region of the Philippines, has its own independent DOLE office.